Walt Disney

Walt Disney | |

|---|---|

Walt Disney in 1954 | |

| Born | Walter Elias Disney December 5, 1901[1] |

| Died | December 15, 1966 (aged 65) |

| Occupation(s) | Film producer, Co-founder of The Walt Disney Company, formerly known as Walt Disney Productions |

| Years active | 1920–1966 |

| Spouse | Lillian Bounds (1925–1966) |

| Children | Diane Marie Disney Sharon Mae Disney |

| Parent(s) | Elias Disney Flora Call Disney |

| Relatives | Herbert Arthur Disney (brother) Raymond Arnold Disney (brother) Roy Oliver Disney (brother) Ruth Flora Disney (sister) Ronald William Miller (son-in-law) Robert Borgfeldt Brown (son-in-law) Roy Edward Disney (nephew) |

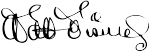

| Signature | |

| |

Walter Elias "Walt" Disney (December 5, 1901 – December 15, 1966) was an American film producer, director, screenwriter, voice actor, animator, entrepreneur, entertainer, international icon,[2] and philanthropist. Disney is famous for his influence in the field of entertainment during the 20th century. As the co-founder (with his brother Roy O. Disney) of Walt Disney Productions, Disney became one of the best-known motion picture producers in the world. The corporation he co-founded, now known as The Walt Disney Company, today has annual revenues of approximately USD $35 billion.

Disney is particularly noted for being a film producer and a popular showman, as well as an innovator in animation and theme park design. He and his staff created some of the world's most famous fictional characters including Mickey Mouse, a character for which Disney himself was the original voice. He has been awarded four honorary Academy Awards and has won twenty-two competitive Academy Awards out of fifty-nine nominations, including a record four in one year,[3] giving him more awards and nominations than any other individual. He also won seven Emmy Awards. He is the namesake for Disneyland and Walt Disney World Resort theme parks in the United States, as well as the international resorts Tokyo Disney, Disneyland Paris, and Disneyland Hong Kong.

Disney died of lung cancer in Burbank, California, on December 15, 1966. The following year, construction began on Walt Disney World Resort in Florida. His brother Roy Disney inaugurated the Magic Kingdom on October 1, 1971.

1901–1937: The beginnings

Childhood

Walter Elias Disney was born on December 5, 1901, to Elias Disney, of Irish-Canadian descent, and Flora Call Disney, of German-American descent, in Chicago's Hermosa community area at 2156 N. Tripp Ave.[4][5] Walt Disney's ancestors had emigrated from Gowran, County Kilkenny in Ireland. Arundel Elias Disney, great-grandfather of Walt Disney, was born in Kilkenny, Ireland in 1801 and was a descendant of Robert d'Isigny, originally of France but who travelled to England with William the Conqueror in 1066.[6] The d'Isigny name became anglicised as Disney and the family settled in the village now known as Norton Disney, south of the city of Lincoln, in the county of Lincolnshire.

His father, Elias Disney, moved from Huron County, Ontario, to the United States in 1878, seeking first for gold in California but finally farming with his parents near Ellis, Kansas, until 1884. He worked for Union Pacific Railroad and married Flora Call on January 1, 1888, in Acron, Florida. The family moved to Chicago, Illinois, in 1890,[7] where his brother Robert lived.[7] For most of his early life, Robert helped Elias financially.[7] In 1906, when Walt was four, Elias and his family moved to a farm in Marceline, Missouri,[8] where his brother Roy had recently purchased farmland.[8] While in Marceline, Disney developed his love for drawing.[9] One of their neighbors, a retired doctor named "Doc" Sherwood, paid him to draw pictures of Sherwood's horse, Rupert.[9] He also developed his love for trains in Marceline, which owed its existence to the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway which ran through town. Walt would put his ear to the tracks in anticipation of the coming train.[5] Then he would look for his uncle, engineer Michael Martin, running the train.

The Disneys remained in Marceline for four years,[10] before moving to Kansas City in 1911.[11] There, Walt and his younger sister Ruth attended the Benton Grammar School where he met Walter Pfeiffer. The Pfeiffers were theatre aficionados, and introduced Walt to the world of vaudeville and motion pictures. Soon, Walt was spending more time at the Pfeiffers' than at home.[12] During this time he attended Saturday courses as a child at the Kansas City Art Institute.[13] While they were living in Kansas City, Walt and Ruth Disney were also regular visitors of Electric Park, 15 blocks from their home (Disney would later acknowledge the amusement park as a major influence of his design of Disneyland).

Teenage years

In 1917, Elias acquired shares in the O-Zell jelly factory in Chicago and moved his family back there.[14] In the fall, Disney began his freshman year at McKinley High School and began taking night courses at the Chicago Art Institute.[15] Disney became the cartoonist for the school newspaper. His cartoons were very patriotic, focusing on World War I. Disney dropped out of high school at the age of sixteen to join the Army, but the army rejected him because he was underage.[16]

After his rejection from the army, Walt and one of his friends decided to join the Red Cross.[17] Soon after he joined The Red Cross, Walt was sent to France for a year, where he drove an ambulance, but not before the armistice was signed on November 11, 1918.[18]

In 1919, Walt, hoping to find work outside the Chicago O-Zell factory,[19] left home and moved back to Kansas City to begin his artistic career.[20] After considering becoming an actor or a newspaper artist, he decided he wanted to create a career in the newspaper, drawing political caricatures or comic strips. But when nobody wanted to hire him as either an artist or even as an ambulance driver, his brother Roy, who worked at a bank in the area, got a temporary job for him at the Pesmen-Rubin Art Studio through a bank colleague.[20] At Pesmen-Rubin, Disney created ads for newspapers, magazines, and movie theaters.[21] It was here that he met a cartoonist named Ubbe Iwerks.[22] When their time at the Pesmen-Rubin Art Studio expired, they were both without a job, and they decided to start their own commercial company.[23]

In January 1920, Disney and Iwerks formed a short-lived company called, "Iwerks-Disney Commercial Artists". However, following a rough start, Disney left temporarily to earn money at Kansas City Film Ad Company, and was soon joined by Iwerks who was not able to run the business alone.[24] While working for the Kansas City Film Ad Company, where he made commercials based on cutout animation, Disney took up an interest in the field of animation, and decided to become an animator.[25] He was allowed by the owner of the Ad Company, A.V. Cauger, to borrow a camera from work, which he could use to experiment with at home. After reading a book by Edwin G. Lutz, called Animated Cartoons: How They Are Made, Their Origin and Development, he found cel animation to be much more promising than the cutout animation he was doing for Cauger. Walt eventually decided to open his own animation business,[26] and recruited a fellow co-worker at the Kansas City Film Ad Company, Fred Harman, as his first employee.[26] Walt and Harman then secured a deal with local theater owner Frank L. Newman — arguably the most popular "showman" in the Kansas City area at the time[27] — to screen their cartoons — which they titled "Laugh-O-Grams" — at his local theater.[27]

Laugh-O-Gram Studio

Presented as "Newman Laugh-O-Grams",[27] Disney's cartoons became widely popular in the Kansas City area.[28] Through their success, Disney was able to acquire his own studio, also called Laugh-O-Gram,[29] and hire a vast number of additional animators, including Fred Harman's brother Hugh Harman, Rudolf Ising, and his close friend Ubbe Iwerks.[30] Unfortunately, with all his high employee salaries unable to make up for studio profits, Walt was unable to successfully manage money.[31] As a result, the studio became loaded with debt[31] and wound up bankrupt.[32] Disney then set his sights on establishing a studio in the movie industry's capital city, Hollywood, California.[33]

Hollywood

Disney and his brother pooled their money to set up a cartoon studio in Hollywood.[34] Needing to find a distributor for his new Alice Comedies — which he started making while in Kansas City,[32] but never got to distribute — Disney sent an unfinished print to New York distributor Margaret Winkler, who promptly wrote back to him. She was keen on a distribution deal with Disney for more live-action/animated shorts based upon Alice's Wonderland.[35]

Alice Comedies

Virginia Davis (the live-action star of Alice’s Wonderland) and her family were relocated at Disney's request from Kansas City to Hollywood, as were Iwerks and his family. This was the beginning of the Disney Brothers' Studio. It was located on Hyperion Avenue in the Silver Lake district, where the studio remained until 1939. In 1925, Disney hired a young woman named Lillian Bounds to ink and paint celluloid. After a brief period of dating her, the two got married the same year.

The new series, Alice Comedies, was reasonably successful, and featured both Dawn O'Day and Margie Gay as Alice. Lois Hardwick also briefly assumed the role of Alice. By the time the series ended in 1927, the focus was more on the animated characters, in particular a cat named Julius who resembled Felix the Cat, rather than the live-action Alice.

Oswald the Lucky Rabbit

By 1927, Charles Mintz had married Margaret Winkler and assumed control of her business, and ordered a new all-animated series to be put into production for distribution through Universal Pictures. The new series, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, was an almost instant success, and the character, Oswald — drawn and created by Iwerks — became a popular figure. The Disney studio expanded, and Walt hired back Harman, Rudolph Ising, Carman Maxwell, and Friz Freleng from Kansas City.

In February 1928, Disney went to New York to negotiate a higher fee per short from Mintz. Disney was shocked when Mintz announced not only that he wanted to reduce the fee he paid Disney per short but also that he had most of his main animators—including Harman, Ising, Maxwell, and Freleng (notably, except Iwerks, who refused to leave Disney)—under contract and would start his own studio if Disney did not accept the reduced production budgets. Universal, not Disney, owned the Oswald trademark, and could make the films without Disney. Disney declined Mintz's offer and lost most of his animation staff.

With most of his staff gone Disney now found himself on his own again.[36] It took Disney's company 78 years to get back the rights to the Oswald character. The Walt Disney Company reacquired the rights to Oswald the Lucky Rabbit from NBC Universal in 2006, through a trade for longtime ABC sports commentator Al Michaels.[37]

Mickey Mouse

After losing the rights to Oswald, Disney felt the need to develop a new character to replace him. He based the character on a mouse he had adopted as a pet while working in his Laugh-O-Gram studio in Kansas City.[38] Ub Iwerks reworked the sketches made by Disney so the character was easier to animate. However, Mickey's voice and personality was provided by Disney until 1947. In the words of a Disney employee, "Ub designed Mickey's physical appearance, but Walt gave him his soul."[38] Besides Oswald and Mickey, a similar mouse-character is seen in Alice Comedies which featured a mouse named Ike the Mouse, and the first Flip the Frog cartoon called Fiddlesticks, which showed a Mickey Mouse look-alike playing fiddle. The initial films were animated by Iwerks, his name was prominently featured on the title cards. The mouse was originally named "Mortimer", but later christened "Mickey Mouse" by Lillian Disney who thought that the name Mortimer did not fit. Mortimer later became the name of Mickey's rival for Minnie, and was taller than his renowned adversary and had a Brooklyn accent.

The first animated short with Mickey in it was titled, Plane Crazy, which was, like all of Disney's previous works, a silent film. After failing to find a distributor for Plane Crazy or its follow-up, The Gallopin' Gaucho, Disney created a Mickey cartoon with sound called Steamboat Willie. A businessman named Pat Powers provided Disney with both distribution and Cinephone, a sound-synchronization process. Steamboat Willie became an instant success,[39] and Plane Crazy, The Galloping Gaucho, and all future Mickey cartoons were released with soundtracks. After the release of Steamboat Willie, Walt Disney would continue to successfully use sound in all of his future cartoons, and Cinephone became the new distributor for Disney's early sound cartoons as well.[40] Mickey soon eclipsed Felix the Cat as the world's most popular cartoon character.[38] By 1930, Felix, now in sound, had faded from the screen, as his sound cartoons failed to gain attention.[41] Mickey's popularity would now skyrocket in the early 1930s.[38]

Silly Symphonies

Following the footsteps of Mickey Mouse series, a series of musical shorts titled, Silly Symphonies was released in 1929. The first of these was titled The Skeleton Dance and was entirely drawn and animated by Iwerks, who was also responsible for drawing the majority of cartoons released by Disney in 1928 and 1929. Although both series were successful, the Disney studio was not seeing its rightful share of profits from Pat Powers,[42] and in 1930, Disney signed a new distribution deal with Columbia Pictures. The original basis of the cartoons were musical novelty, and Carl Stalling wrote the score for the first Silly Symphony cartoons as well.[43]

Iwerks was soon lured by Powers into opening his own studio with an exclusive contract. Later, Carl Stalling would also leave Disney to join Iwerks' new studio.[44] Iwerks launched his Flip the Frog series with the first voice cartoon in color, "Fiddlesticks," filmed in two-strip Technicolor. Iwerks also created two other series of cartoons, the Willie Whopper and the Comicolor. In 1936, Iwerks shut his studio to work on various projects dealing with animation technology. He would return to Disney in 1940 and, would go on to pioneer a number of film processes and specialized animation technologies in the studio's research and development department.

By 1932, Mickey Mouse had become quite a popular cinema character, but Silly Symphonies was not as successful. The same year also saw competition increase as Max Fleischer's flapper cartoon character, Betty Boop, would gain more popularity among theater audiences.[45] Fleischer was considered to be Disney's main rival in the 1930s,[46] and was also the father of Richard Fleischer, whom Disney would later hire to direct his 1954 film 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. Meanwhile, Columbia Pictures dropped the distribution of Disney cartoons and was replaced by United Artists.[47] In late 1932, Herbert Kalmus, who had just completed work on the first three-strip technicolor camera,[48] approached Walt and convinced him to redo Flowers and Trees, which was originally done in black and white, with three-strip Technicolor.[49] Flowers and Trees would go on to be a phenomenal success and would also win the first Academy Award for Best Short Subject: Cartoons for 1932. After Flowers and Trees was released, all future Silly Symphony cartoons were done in color as well. Disney was also able to negotiate a two-year deal with Technicolor, giving him the sole right to use three-strip Technicolor,[50][51] which would also eventually be extended to five years as well.[43] Through Silly Symphonies, Disney would also create his most successful cartoon short of all time, The Three Little Pigs, in 1933.[52] The cartoon ran in theaters for many months, and also featured the hit song that became the anthem of the Great Depression, "Who's Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf".[53]

First Academy Award

In 1932, Disney received a special Academy Award for the creation of "Mickey Mouse", whose series was made into color in 1935 and soon launched spin-off series for supporting characters such as Donald Duck, Goofy, and Pluto; Pluto and Donald would immediately get their individual cartoons in 1937,[54] and Goofy would get solo cartoons in 1939 as well.[55] Of all of Mickey's partners, Donald Duck—who first teamed with Mickey in the 1934 cartoon, Orphan's Benefit—was arguably the most popular, and went on to become Disney's second most successful cartoon character of all time.[56]

Children

The Disneys' first attempt at pregnancy ended up in Lillian having a miscarriage. When Lillian Disney became pregnant again, she gave birth to a daughter, Diane Marie Disney, on December 18, 1933. The Disneys adopted Sharon Mae Disney (December 31, 1936 – February 16, 1993).[57]

1937–1941: The Golden Age of Animation

"Disney's Folly": Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs

After the creation of two cartoon series, Disney soon began plans for a full-length feature in 1934. In 1935, opinion polls showed that another cartoon series, Popeye the Sailor, produced by Max Fleischer, was more popular than Mickey Mouse.[58] Disney was, however, able to put Mickey back on top, and also increase Mickey's popularity further by colorizing him and partially redesigning him into what was considered to be his most appealing design up to that point in time.[38] When the film industry came to know about Disney's plans to produce an animated feature-length version of Snow White, they dubbed the project "Disney's Folly" and were certain that the project would destroy the Disney Studio. Both Lillian and Roy tried to talk Disney out of the project, but he continued plans for the feature. He employed Chouinard Art Institute professor Don Graham to start a training operation for the studio staff, and used the Silly Symphonies as a platform for experiments in realistic human animation, distinctive character animation, special effects, and the use of specialized processes and apparatus such as the multiplane camera; Disney would first use this new technique in the 1937 Silly Symphonies short The Old Mill.[59]

All of this development and training was used to elevate the quality of the studio so that it would be able to give the feature film the quality Disney desired. Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, as the feature was named, was in full production from 1934 until mid-1937, when the studio ran out of money. To acquire the funding to complete Snow White, Disney had to show a rough cut of the motion picture to loan officers at the Bank of America, who gave the studio the money to finish the picture. The finished film premiered at the Carthay Circle Theater on December 21, 1937; at the conclusion of the film, the audience gave Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs a standing ovation. Snow White, the first animated feature in America and Technicolor, was released in February 1938 under a new distribution deal with RKO Radio Pictures; RKO had previously been the distributor for Disney cartoons in 1936, after it closed down the Van Beuren Studios in exchange for distribution.[60] The film became the most successful motion picture of 1938 and earned over $8 million in its original theatrical release.

The Golden Age of Animation

The success of Snow White, (for which Disney received one full-size, and seven miniature Oscar statuettes) allowed Disney to build a new campus for the Walt Disney Studios in Burbank, which opened for business on December 24, 1939; Snow White was not only the peak of Disney's success, but it also ushered in a period that would later be known as the Golden Age of Animation for Disney.[61][62] The feature animation staff, having just completed Pinocchio, continued work on Fantasia and Bambi and the early production stages of Alice in Wonderland, Peter Pan and Wind in the Willows while the shorts staff continued work on the Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, Goofy, and Pluto cartoon series, ending the Silly Symphonies at this time. Animator Fred Moore had redesigned Mickey Mouse in the late 1930s, when Donald Duck began to gain more popularity among theater audiences than Mickey Mouse.[63]

Pinocchio and Fantasia followed Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs into the movie theaters in 1940, but both were financial disappointments. The inexpensive Dumbo was planned as an income generator, but during production of the new film, most of the animation staff went on strike, permanently straining the relationship between Disney and his artists.

1941–1945: During World War II

Disney and a group of animators were sent to South America in 1941 by the U.S. State Department as part of its Good Neighbor policy, and guaranteed financing for the resulting movie, Saludos Amigos.[64]

Shortly after the release of Dumbo in October 1941, the United States entered World War II. The U.S. Army contracted most of the Disney studio's facilities and had the staff create training and instructional films for the military, home-front morale-boosting shorts such as Der Fuehrer's Face and the feature film Victory Through Air Power in 1943. However, the military films did not generate income, and the feature film Bambi underperformed when it was released in April 1942. Disney successfully re-issued Snow White in 1944, establishing a seven-year re-release tradition for Disney features. In 1945, The Three Caballeros was the last animated feature by Disney during the war period.

In 1944, William Benton, publisher of the Encyclopædia Britannica, had entered into unsuccessful negotiations with Disney to make six to twelve educational films annually. Disney was asked by the US Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs, Office of Inter-American Affairs (OIAA), to make an educational film about the Amazon Basin and it resulted in the 1944 animated short, The Amazon Awakens.[65][66][67][68][69]

1945–1955: Disney in the post-war period

The Disney studios also created inexpensive package films, containing collections of cartoon shorts, and issued them to theaters during this period. This includes Make Mine Music (1946), Melody Time (1948), Fun and Fancy Free (1947) and The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (1949). The latter had only two sections: the first based on The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame, and the second based on The Legend of Sleepy Hollow by Washington Irving. During this period, Disney also ventured into full-length dramatic films that mixed live action and animated scenes, including Song of the South and So Dear to My Heart. After the war ended, Mickey's popularity would also fade as well.[70]

By the late 1940s, the studio had recovered enough to continue production on the full-length features Alice in Wonderland and Peter Pan, both of which had been shelved during the war years, and began work on Cinderella, which became Disney's most successful film since Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. The studio also began a series of live-action nature films, titled True-Life Adventures, in 1948 with On Seal Island. Despite rebounding success through feature films, Disney's animation shorts were no longer as popular as they used to be, and people began to instead draw attention to Warner Bros and their animation star Bugs Bunny. By 1942, Leon Schlesinger Productions, which produced the Warner Bros. cartoons, had become the country's most popular animation studio.[71] However, while Bugs Bunny's popularity rose in the 1940s, so did Donald Duck's;[72] Donald would also replace Mickey Mouse as Disney's star character by 1949.[73]

During the mid-1950s, Disney produced a number of educational films on the space program in collaboration with NASA rocket designer Wernher von Braun: Man in Space and Man and the Moon in 1955, and Mars and Beyond in 1957.

Testimony before Congress

Disney was a founding member of the anti-communist Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals. {{citation}}: Empty citation (help) In 1947, during the early years of the Cold War,[74] Disney testified before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), where he branded Herbert Sorrell, David Hilberman and William Pomerance, former animators and labor union organizers, as Communist agitators. All three men denied the allegations. Sorrell testified before the HUAC in 1946 and there was insufficient evidence to link him to the Communist Party.[75][76]

Additionally, Disney accused the Screen Actors Guild of being a Communist front, and charged that the 1941 strike was part of an organized Communist effort to gain influence in Hollywood.[74]

1955–1966: Theme parks and beyond

Planning Disneyland

On a business trip to Chicago in the late-1940s, Disney drew sketches of his ideas for an amusement park where he envisioned his employees spending time with their children. He got his idea for a children's theme park after visiting Children's Fairyland in Oakland, California. This plan was originally meant for a plot located south of the Studio, across the street. The original ideas developed into a concept for a larger enterprise that was to become Disneyland. Disney spent five years of his life developing Disneyland and created a new subsidiary of his company, called WED Enterprises, to carry out the planning and production of the park. A small group of Disney studio employees joined the Disneyland development project as engineers and planners, and were dubbed Imagineers.

When describing one of his earliest plans to Herb Ryman (who created the first aerial drawing of Disneyland which was presented to the Bank of America while requesting for funds), Disney said, "Herbie, I just want it to look like nothing else in the world. And it should be surrounded by a train."[77] Entertaining his daughters and their friends in his backyard and taking them for rides on his Carolwood Pacific Railroad had inspired Disney to include a railroad in the plans for Disneyland.

Disneyland grand opening

Disneyland officially opened on July 18, 1955. On Sunday, July 17, 1955, Disneyland hosted a live TV preview, among the thousands of people who came out for the preview were Ronald Reagan, Bob Cummings and Art Linkletter, who shared cohosting duties, as well as the mayor of Anaheim. Walt gave the following dedication day speech:

To all who come to this happy place; welcome. Disneyland is your land. Here age relives fond memories of the past .... and here youth may savor the challenge and promise of the future. Disneyland is dedicated to the ideals, the dreams and the hard facts that have created America ... with the hope that it will be a source of joy and inspiration to all the world.

Carolwood Pacific Railroad

During 1949, Disney and his family moved to a new home on a large piece of property in the Holmby Hills district of Los Angeles, California. With the help of his friends Ward and Betty Kimball, owners of their own backyard railroad, Disney developed blueprints and immediately set to work on creating a miniature live steam railroad for his backyard. The name of the railroad, Carolwood Pacific Railroad, originated from the address of his home that was located on Carolwood Drive. The railroad's half-mile long layout included a 46-foot (14 m)-long trestle, loops, overpasses, gradients, an elevated berm, and a 90-foot (27 m) tunnel underneath Mrs. Disney's flowerbed. He named the miniature working steam locomotive built by Disney Studios engineer Roger E. Broggie Lilly Belle in his wife's honor. He had his attorney draw up right-of-way papers giving the railroad a permanent, legal easement through the garden areas, which his wife dutifully signed; however, there is no evidence of the documents ever recorded as a restriction on the property's title.

Expanding into new areas

As Walt Disney Productions began work on Disneyland, it also began expanding its other entertainment operations. In 1950, Treasure Island became the studio's first all-live-action feature, and was soon followed by 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (in CinemaScope, 1954), Old Yeller (1957), The Shaggy Dog (1959), Pollyanna (1960), Swiss Family Robinson (1960), The Absent-Minded Professor (1961), and The Parent Trap (1961). The Walt Disney Studio produced its first TV special, One Hour in Wonderland, in 1950. Disney began hosting a weekly anthology series on ABC named Disneyland after the park, where he showed clips of past Disney productions, gave tours of his studio, and familiarized the public with Disneyland as it was being constructed in Anaheim, California. The show also featured a Davy Crockett miniseries, which started a craze among the American youth known as the Davy Crockett craze, in which millions of coonskin caps and other Crockett memorabilia were sold across the country.[78] In 1955, the studio's first daily television show, Mickey Mouse Club debuted, which would continue in many various incarnations into the 1990s.

As the studio expanded and diversified into other media, Disney devoted less of his attention to the animation department, entrusting most of its operations to his key animators, whom he dubbed the Nine Old Men. During Disney's lifetime, the animation department created the successful Lady and the Tramp (in CinemaScope, 1955), Sleeping Beauty (in Super Technirama 70mm, 1959), One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961), and The Sword in the Stone (1963).

Production on the short cartoons had kept pace until 1956, when Disney shut down the shorts division. Special shorts projects would continue to be made for the rest of the studio's duration on an irregular basis. These productions were all distributed by Disney's new subsidiary, Buena Vista Distribution, which had assumed all distribution duties for Disney films from RKO by 1955. Disneyland, one of the world's first theme parks, finally opened on July 17, 1955, and was immediately successful. Visitors from around the world came to visit Disneyland, which contained attractions based upon a number of successful Disney properties and films.

After 1955, the show, Disneyland came to be known as Walt Disney Presents. The show transformed from black-and-white to color in 1961 and changed its name to Walt Disney's Wonderful World of Color, moving from ABC to NBC,[79] and eventually evolving into its current form as The Wonderful World of Disney. It continued to air on NBC until 1981, when CBS picked it up.[80] Since then, it has aired on ABC, NBC, Hallmark Channel and Cartoon Network via separate broadcast rights deals. During its run, the Disney series offered some recurring characters, such as Roger Mobley appearing as the newspaper reporter and sleuth "Gallegher", based on the writing of Richard Harding Davis.

Disney had already formed his own music publishing division back in 1949. In 1956, partly inspired by the huge success of the television theme song The Ballad of Davy Crockett, he created a company-owned record production and distribution entity called Disneyland Records.

Early 1960s successes

By the early 1960s, the Disney empire was a major success, and Walt Disney Productions had established itself as the world's leading producer of family entertainment. Walt Disney was the Head of Pageantry for the 1960 Winter Olympics.

After decades of pursuing, Disney finally procured the rights to P.L. Travers' books about a magical nanny. Mary Poppins, released in 1964, was the most successful Disney film of the 1960s and featured a memorable song score written by Disney favorites, the Sherman Brothers. The same year, Disney debuted a number of exhibits at the 1964 New York World's Fair, including Audio-Animatronic figures, all of which were later integrated into attractions at Disneyland and a new theme park project which was to be established on the East Coast.

Though the studio probably would have made great competition with Hanna-Barbera, Disney had decided not to enter the race for producing Saturday morning cartoon series on television (which Hanna-Barbera had done at the time), because with the expansion of Disney's empire and constant production of feature films, there would be too much for the budget to handle.

Plans for Disney World and EPCOT

In early 1964, Disney announced plans to develop another theme park located a few miles west of Orlando, Florida which was to be called Disney World. Disney World was to include a larger, more elaborate version of Disneyland which was to be called the Magic Kingdom. It would also feature a number of golf courses and resort hotels. The heart of Disney World, however, was to be the Experimental Prototype City (or Community) of Tomorrow, or EPCOT for short.

Mineral King Ski Resort

During the early to mid 1960s, Walt Disney developed plans for a ski resort in Mineral King, a glacial valley in California's Sierra Nevada mountain range. Disney brought in experts like the renowned Olympic ski coach and ski-area designer Willy Schaeffler, who helped plan a visitor village, ski runs and ski lifts among the several bowls surrounding the valley. Plans finally moved into action in the mid 1960s, but Walt died before the actual work had started. Disney's death and the actions from preservationists made sure the resort was never built.

Death

In 1966, Disney was scheduled to undergo surgery to repair an old neck injury[81] caused by many years of playing polo at the Riviera Club in Hollywood.[82] On November 2, during pre-operative X-rays, doctors at Providence St. Joseph Medical Center, across the street from the Disney Studio, discovered a tumor in his left lung.[83] Five days later he underwent biopsy of the tumor, which proved to be malignant, and to have spread throughout the entire left lung.[83] After removal of the lung, doctors informed Disney that his life expectancy was six months to two years.[83] After several chemotherapy sessions, Disney and his wife spent a short amount of time in Palm Springs, California.[81] On November 30, Disney collapsed in his home. He was revived by fire department personnel and rushed to St. Joseph's. On December 15, 1966, at 9:30 a.m., ten days after his 65th birthday, Disney died of acute circulatory collapse, caused by lung cancer.[81] The last thing he reportedly wrote before his death was the name of actor Kurt Russell, the significance of which remains a mystery, even to Russell.[84]

Disney was cremated on December 17, 1966, and his ashes interred at the Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, California. Roy O. Disney continued to carry out the Florida project, insisting that the name be changed to Walt Disney World in honor of his brother.

The final productions in which Disney played an active role were the animated features The Jungle Book and Winnie the Pooh and the Blustery Day, and the live-action musical comedy The Happiest Millionaire, both released in 1967. Songwriter Robert B. Sherman said about the last time he saw Disney:

He was up in the third floor of the animation building after a run-through of The Happiest Millionaire. He usually held court in the hallway afterward for the people involved with the picture. And he started talking to them, telling them what he liked and what they should change, and then, when they were through, he turned to us and with a big smile, he said, 'Keep up the good work, boys.' And he walked to his office. It was the last we ever saw of him.[85]

A long-standing urban legend maintains that Disney was cryogenically frozen, and his frozen corpse stored underneath the Pirates of the Caribbean ride at Disneyland.[86] However, the first known cryogenic freezing of a human corpse did not occur until January 1967.[86]

Legacy: 1967 to the present

Continuing Disney Productions

After Walt Disney's death, Roy Disney returned from retirement to take full control of Walt Disney Productions and WED Enterprises. In October 1971, the families of Walt and Roy met in front of Cinderella Castle at the Magic Kingdom to officially open the Walt Disney World Resort.

After giving his dedication for Walt Disney World, Roy asked Lillian Disney to join him. As the orchestra played "When You Wish Upon a Star", she stepped up to the podium accompanied by Mickey Mouse. He then said, "Lilly, you knew all of Walt's ideas and hopes as well as anybody; what would Walt think of it [Walt Disney World]?". "I think Walt would have approved," she replied.[87] Roy died from a cerebral hemorrhage on December 20, 1971, the day he was due to open the Disneyland Christmas parade.

During the second phase of the "Walt Disney World" theme park, EPCOT was translated by Disney's successors into EPCOT Center, which opened in 1982. As it currently exists, EPCOT is essentially a living world's fair, different from the actual functional city that Disney had envisioned. In 1992, Walt Disney Imagineering took the step closer to Disney's original ideas and dedicated Celebration, Florida, a town built by the Walt Disney Company adjacent to Walt Disney World, that hearkens back to the spirit of EPCOT. EPCOT was also originally intended to be devoid of Disney characters which initially limited the appeal of the park to young children. However, the company later changed this policy and Disney characters can now be found throughout the park, often dressed in costumes reflecting the different pavilions.

The Disney entertainment empire

Today, Walt Disney's animation/motion picture studios and theme parks have developed into a multi-billion dollar television, motion picture, vacation destination and media corporation that carry his name. The Walt Disney Company today owns, among other assets, five vacation resorts, eleven theme parks, two water parks, thirty-nine hotels, eight motion picture studios, six record labels, eleven cable television networks, and one terrestrial television network. As of 2007, the company has an annual revenue of over U.S. $35 billion.[88]

Disney Animation today

Traditional hand-drawn animation, with which Walt Disney started his company, was, for a time, no longer produced at the Walt Disney Animation Studios. After a stream of financially unsuccessful traditionally animated features in the early 2000s, the two satellite studios in Paris and Orlando were closed, and the main studio in Burbank was converted to a computer animation production facility. In 2004, Disney released what was announced as their final "traditionally animated" feature film, Home on the Range. However, since the 2006 acquisition of Pixar, and the resulting rise of John Lasseter to Chief Creative Officer, that position has changed, and the largely successful 2009 film The Princess and the Frog has marked Disney's return to traditional hand-drawn animation.

CalArts

In his later years, Disney devoted substantial time towards funding The California Institute of the Arts (CalArts). It was formed in 1961 through a merger of the Los Angeles Conservatory of Music and the Chouinard Art Institute, which had helped in the training of the animation staff during the 1930s. When Disney died, one-fourth of his estate went towards CalArts, which helped in building its campus. In his will, Disney paved the way for creation of several charitable trusts which included one for the California Institute of the Arts and other for the Disney Foundation.[89] He also donated 38 acres (0.154 km2) of the Golden Oaks ranch in Valencia for the school to be built on. CalArts moved onto the Valencia campus in 1972.

In an early admissions bulletin, Disney explained:

A hundred years ago, Wagner conceived of a perfect and all-embracing art, combining music, drama, painting, and the dance, but in his wildest imagination he had no hint what infinite possibilities were to become commonplace through the invention of recording, radio, cinema and television. There already have been geniuses combining the arts in the mass-communications media, and they have already given us powerful new art forms. The future holds bright promise for those who imaginations are trained to play on the vast orchestra of the art-in-combination. Such supermen will appear most certainly in those environments which provide contact with all the arts, but even those who devote themselves to a single phase of art will benefit from broadened horizons.[90]

The Walt Disney Family Museum

In 2009, the Walt Disney Family Museum opened in the Presidio of San Francisco. Thousands of artifacts of Disney's life and career are on display, including 248 awards he received.[91]

Anti-Semitism accusations

Disney was long rumored to be anti-Semitic during his lifetime, and such rumors have persisted after his death. Disney's 2006 biographer Neal Gabler, the first writer to gain unrestricted access to the Disney archives, concluded that available evidence does not support such accusations. "That's one of the questions everybody asks me," Gabler said in a CBS interview. "My answer to that is, not in the conventional sense that we think of someone as being an anti-Semite. But he got the reputation because, in the 1940s, he got himself allied with a group called the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals, which was an anti-Communist and anti-Semitic organization. And though Walt himself, in my estimation, was not anti-Semitic, nevertheless, he willingly allied himself with people who were anti-Semitic, and that reputation stuck. He was never really able to expunge it throughout his life."[92] Disney ultimately distanced himself from the Motion Picture Alliance in the 1950s.[93]

The Walt Disney Family Museum acknowledges that Disney did have "difficult relationships" with some Jewish men, and that ethnic stereotypes common to films of the 1930s were included in some early cartoons, such as Three Little Pigs; but points out that he employed Jews throughout his career, and was named "Man Of The Year" in 1955 by the B'nai B'rith chapter in Beverly Hills.[94]

Academy Awards

Walt Disney holds the records for the most number of Academy Award nominations (with fifty-nine) and number of awarded Oscars (twenty-two). He has also earned four honorary Oscars. His last competitive Academy Award was posthumous.[95]

- 1932: Best Short Subject, Cartoons for: Flowers and Trees (1932)

- 1932: Honorary Award for: creation of Mickey Mouse.

- 1934: Best Short Subject, Cartoons for: Three Little Pigs (1933)

- 1935: Best Short Subject, Cartoons for: The Tortoise and the Hare (1934)

- 1936: Best Short Subject, Cartoons for: Three Orphan Kittens (1935)

- 1937: Best Short Subject, Cartoons for: The Country Cousin (1936)

- 1938: Best Short Subject, Cartoons for: The Old Mill (1937)

- 1939: Best Short Subject, Cartoons for: Ferdinand the Bull (1938)

- 1939: Honorary Award for Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) The citation read: "For Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, recognized as a significant screen innovation which has charmed millions and pioneered a great new entertainment field" (the award was one statuette and seven miniature statuettes)[3]

- 1940: Best Short Subject, Cartoons for: Ugly Duckling (1939)

- 1941: Honorary Award for: Fantasia (1940), shared with: William E. Garity and J.N.A. Hawkins. The citation for the certificate of merit read: "For their outstanding contribution to the advancement of the use of sound in motion pictures through the production of Fantasia"[3]

- 1942: Best Short Subject, Cartoons for: Lend a Paw (1941)

- 1943: Best Short Subject, Cartoons for: Der Fuehrer's Face (1942)

- 1949: Best Short Subject, Two-reel for: Seal Island (1948)

- 1949: Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award (Honorary Award)

- 1951: Best Short Subject, Two-reel for: Beaver Valley (1950)

- 1952: Best Short Subject, Two-reel for: Nature's Half Acre (1951)

- 1953: Best Short Subject, Two-reel for: Water Birds (1952)

- 1954: Best Documentary, Features for: The Living Desert (1953)

- 1954: Best Documentary, Short Subjects for: The Alaskan Eskimo (1953)

- 1954: Best Short Subject, Cartoons for: Toot Whistle Plunk and Boom (1953)

- 1954: Best Short Subject, Two-reel for: Bear Country (1953)

- 1955: Best Documentary, Features for: The Vanishing Prairie (1954)

- 1956: Best Documentary, Short Subjects for: Men Against the Arctic

- 1959: Best Short Subject, Live Action Subjects for: Grand Canyon

- 1969: Best Short Subject, Cartoons for: Winnie the Pooh and the Blustery Day

Other honors

Walt Disney was the inaugural recipient of a star on the Anaheim walk of stars. The star was awarded in honor of Disney's significant contributions to the city of Anaheim, California, specifically, Disneyland, which is now the Disneyland Resort. The star is located at the pedestrian entrance to the Disneyland Resort on Harbor Boulevard. Disney has two stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, one for motion pictures and the other for television.

Walt Disney received the Congressional Gold Medal on May 24, 1968 (P.L. 90-316, 82 Stat. 130–131) and the Légion d'Honneur in France in 1935.[96] In 1935, Walt received a special medal from the League of Nations for creation of Mickey Mouse, held to be Mickey Mouse award.[97] He also received the Presidential Medal of Freedom on September 14, 1964.[98] On December 6, 2006, California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger and First Lady Maria Shriver inducted Walt Disney into the California Hall of Fame located at The California Museum for History, Women, and the Arts.

A minor planet, 4017 Disneya, discovered in 1980 by Soviet astronomer Lyudmila Georgievna Karachkina, is named after him.[99]

The Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, California, opened in 2003, was named in his honor.

Beginning in 1993, HBO began to develop a Walt Disney biopic under the direction of Frank Pierson with Lawrence Turman. The project never materialized and was soon abandoned.[100]

See also

- Disney family

- The Mickey Mouse Club

- The Walt Disney Family Museum

- Walt Disney anthology television series

Notes

- ^ "Walt Disney". IMDB. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ Dave Bryan (2002-08-13). "Walt Disney Helped Wernher von Braun Sell Americans on Space". Associated Press. Retrieved 2010-09-27.

- ^ a b c "Walt Disney Academy awards". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ "Walt Disney, the man behind the mouse". Chicago Sun-Times. 2009-09-27. Retrieved 2010-10-21.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name=ignored (help) [dead link] - ^ a b "Walt Disney biography". Just Disney. Archived from the original on 2008-06-05. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ Disneyland Paris. Michelin. 2002-08-07. p. 38. ISBN 2060480027.

- ^ a b c Neal Gabler, "Walt Disney:The Triumph of the American Imagination" (2006), p. 7.

- ^ a b Neal Gabler, "Walt Disney:The Triumph of the American Imagination" (2006), p. 9-10.

- ^ a b Neal Gabler, "Walt Disney:The Triumph of the American Imagination" (2006), p. 15.

- ^ "Walt Disney Hometown Museum". Walt Disney Museum. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ Neal Gabler, "Walt Disney:The Triumph of the American Imagination" (2006), p. 18.

- ^ Thomas 1994, pp. 33–41

- ^ Biography of Walt Disney, Film Producer – kchistory.org – Retrieved September 14, 2009

- ^ Neal Gabler, "Walt Disney:The Triumph of the American Imagination" (2006), p. 30.

- ^ Thomas 1994, pp. 42–43

- ^ Neal Gabler, "Walt Disney:The Triumph of the American Imagination" (2006), p. 36.

- ^ Neal Gabler, "Walt Disney:The Triumph of the American Imagination" (2006), p. 37.

- ^ Neal Gabler, "Walt Disney:The Triumph of the American Imagination" (2006), p. 38.

- ^ Neal Gabler, "Walt Disney:The Triumph of the American Imagination" (2006), p. 42.

- ^ a b Neal Gabler, "Walt Disney:The Triumph of the American Imagination" (2006), p. 44.

- ^ Neal Gabler, "Walt Disney:The Triumph of the American Imagination" (2006), p. 45.

- ^ Neal Gabler, "Walt Disney:The Triumph of the American Imagination" (2006), p. 46.

- ^ Neal Gabler, "Walt Disney:The Triumph of the American Imagination" (2006), p. 48.

- ^ Neal Gabler, "Walt Disney:The Triumph of the American Imagination" (2006), p. 51.

- ^ Neal Gabler, "Walt Disney:The Triumph of the American Imagination" (2006), p. 52.

- ^ a b Neal Gabler, "Walt Disney:The Triumph of the American Imagination" (2006), p. 56.

- ^ a b c Neal Gabler, "Walt Disney:The Triumph of the American Imagination" (2006), p. 57.

- ^ Neal Gabler, "Walt Disney:The Triumph of the American Imagination" (2006), p. 58.

- ^ Neal Gabler, "Walt Disney:The Triumph of the American Imagination" (2006), p. 64.

- ^ Neal Gabler, "Walt Disney:The Triumph of the American Imagination" (2006), p. 64-71.

- ^ a b Neal Gabler, "Walt Disney:The Triumph of the American Imagination" (2006), p. 68.

- ^ a b Neal Gabler, "Walt Disney:The Triumph of the American Imagination" (2006), p. 72.

- ^ Neal Gabler, "Walt Disney:The Triumph of the American Imagination" (2006), p. 75.

- ^ Neal Gabler, "Walt Disney:The Triumph of the American Imagination" (2006), p. 78.

- ^ Neal Gabler, "Walt Disney:The Triumph of the American Imagination" (2006), p. 80.

- ^ Neal Gabler, "Walt Disney:The Triumph of the American Imagination" (2006), p. 109.

- ^ Stay 'tooned: Disney gets 'Oswald' for Al Michaels, at ESPN web site, retrieved January 4, 2010

- ^ a b c d e Solomon, Charles. "The Golden Age of Mickey Mouse". Disney. Archived from the original on 2008-07-10. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ Neal Gabler, "Walt Disney:The Triumph of the American Imagination" (2006), p. 128.

- ^ Neal Gabler, "Walt Disney:The Triumph of the American Imagination" (2006), p. 129.

- ^ Gordon, Ian (2002). "Felix the Cat". St. James Encyclopedia of Pop Culture. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ Neal Gabler, "Walt Disney:The Triumph of the American Imagination" (2006), p. 142.

- ^ a b Merritt, Russell. "THE BIRTH OF THE SILLY SYMPHONIES". Disney. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ "Chronology of the Walt Disney Company". Island Net. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ Langer, Mark (July 1997). "Popeye From Strip To Screen" (PDF). 2 (4). Animation Magazine: 17–19. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Fleischer brothers". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ "Chronology of the Walt Disney Company". Island Net. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ "System 4". Widescreen Museum. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ "System 4". Widescreen Museum. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ "Walt Disney at the Museum?". Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ "Once Upon a Time: Walt Disney: The Sources of Inspiration for the Disney Studios". fps magazine. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ Danks, Adrian. "Huffing and Puffing about Three Little Pigs". Senses of Cinema. Archived from the original on April 22, 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ "Three Little Pigs". Disney. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ "Chronology of the Walt Disney Company". Island Net. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ "GOOFY BIOGRAPHY". Tripod.com. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ "Donald Duck". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ Social Security Death Index

- ^ "Popeye's Popularity – Article from 1935". Golden Age Cartoons. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ "Walt Disney, Biography". Just Disney. Archived from the original on 2007-07-10. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ "Cartoons that Time Forgot". Images Journal. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ "Walt Disney Studio Biography". Animation USA. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ "The Golden Age of Animation". Disney. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ "Fantasia Review". The Big Cartoon Database. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ Walt & El Grupo (documentary film, 2008).

- ^ Gabler, 2006, p.444

- ^ Cramer, Gisela; Prutsch, Ursula, "Nelson A. Rockefeller's Office of Inter-American Affairs (1940–1946) and Record Group 229", Hispanic American Historical Review 2006 86(4):785–806; DOI:10.1215/00182168-2006-050. Cf. p.795 and note 28.

- ^ Bender, Pennee. "Hollywood Meets South American and Stages a Show" Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Studies Association. 2009-05-24 <http://www.allacademic.com/meta/p114070_index.html>

- ^ Niblo, Stephen R., "Mexico in the 1940s: Modernity, Politics, and Corruption", Wilimington, Del. : Scholarly Resources, 1999. ISBN 0842027947. Cf. "Nelson Rockefeller and the Office of Inter-American Affairs", p.333

- ^ Leonard, Thomas M.; Bratzel, John F., Latin America during World War II, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2007. ISBN 978-0742537415. Cf. p.47.

- ^ Solomon, Charles. "Mickey in the Post-War Era". Disney. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ "Warner Bros. Studio Biography". Animation USA. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ "Disney's Animated Classics". Sandcastle VI. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ "Donald Duck". Pet Care Tips. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ a b "Testimony of Walter E. Disney before HUAC". CNN. 1947-10-24. Archived from the original on May 14, 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ Cogley, John (1956) Report on Blacklisting, Volume I, Movies Fund for the Republic, New York, p. 34 OCLC 3794664; reprinted in 1972 by Arno Press, New York ISBN 0-405-03915-8

- ^ "Communist brochure" Screen Actors Guild accessed October 20, 2008

- ^ "Walt Disney Quotes". Tripod.com. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ Cotter, Bill. "The Television Worlds of Disney – PART II". Disney. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ "Chronology of the Walt Disney Company". Island Net. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ "Chronology of the Walt Disney Company". Island Net. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ a b c "The Day Walt Died". Disney. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ "Horsing Around With Walt and Polo". Mouse Planet. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ a b c "Chronology of the Walt Disney Company". Island Net. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ "Kurt Russell Confirms Disney's Last Words". Star Pulse. Retrieved 2007-04-24.

- ^ Greene, K&R (2001). Inside The Dream: The Personal Story Of Walt Disney. Disney Editions. p. 180. ISBN 0786853506.

- ^ a b Mikkelson, B & DP (2007-08-24). "Suspended Animation". Snopes.com. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ Griffiths, Bill. "Grand opening of Walt Disney world". Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ "Walt Disney corporate website". Disney. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ "Walt Disney's will". Do Your Own Will. Retrieved 2008-01-03.

- ^ Plagens, Peter (2000). Sunshine Muse: Art on the West Coast, 1945–1970. University of California Press. p. 159. ISBN 0520223926.

- ^ Rothstein, Edward (September 30, 2009). "Exploring the Man Behind the Animation". The New York Times.

- ^ "Walt Disney: More Than 'Toons, Theme Parks". CBS News. 2006-11-01.

- ^ Gabler, Neal (2007). Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination. Random House. p. 458. ISBN 9780679757474.

- ^ http://disney.go.com/disneyatoz/familymuseum/collection/insidestory/inside_1933d.html

- ^ http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0000370/awards

- ^ "Disney, Walt" (in French). Bedetheque. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ "Minnie's Cheat Sheet to my Website". AOL. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ "Medal of Freedom". Presidential Medal of Freedom. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ Schmadel, Lutz D. (2003). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names. New York: Springer Science+Business Media. p. 342. ISBN 3540002383.

- ^ David Rooney (1994-03-03). "Disney wins Houston and Washington teaming ..." Variety. Retrieved 2009-03-31.

References

- Thomas, Bob (1994). Walt Disney: An American Original. New York: Hyperion. ISBN 0-7868-6027-8.

Further reading

- Barrier, Michael (1999). Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-516729-5.

- Broggie, Michael (1997, 1998, 2005). Walt Disney's Railroad Story. Virginia Beach, Virginia. Donning Publishers. ISBN 1-56342-009-0

- Eliot, Marc (1993). Walt Disney: Hollywood's Dark Prince. Carol. ISBN 1-55972-174-X

- Mosley, Leonard. Disney's World: A Biography (1985, 2002). Chelsea, MI: Scarborough House. ISBN 0-8128-8514-7.

- Gabler, Neal. Walt Disney: The Triumph of American Imagination (2006). New York, NY. Random House. ISBN 0-679-43822-X

- Schickel, Richard, and Dee, Ivan R. (1967, 1985, 1997). The Disney Version: The Life, Times, Art and Commerce of Walt Disney. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, Publisher. ISBN 1-56663-158-0.

- Sherman, Robert B. and Sherman, Richard M. (1998) "Walt's Time: From Before to Beyond" ISBN 0-9646059-3-7.

- Thomas, Bob (1991). Disney's Art of Animation: From Mickey Mouse to Beauty and the Beast. New York: Hyperion. ISBN 1-56282-899-1

- Watts, Steven, The Magic Kingdom: Walt Disney and the American Way of Life, University of Missouri Press, 2001, ISBN 0826213790

External links

- Walt Disney at IMDb

- Walt Disney at the TCM Movie Database

- Template:Worldcat id

- "The Hollywood Blacklist". Talk of the Nation. 1997.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) Discusses Walt Disney's attitude towards unions and communism. - Walt Disney Family Museum

- Neal Gabler, Inside Walt Disney

- "Anaheim Walk of Stars". Archived from the original on 2007-04-02.

- Interview with Robert Stack About Walt Disney's Involvement in Polo

- Walt Disney Gravesite

- Disney's Fantastic Voyage

- History of Walt Disney

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA

- Walt Disney

- 1901 births

- 1966 deaths

- American animators

- American anti-communists

- American cartoonists

- American Congregationalists

- American Christians

- American entertainment industry businesspeople

- American film directors

- American film producers

- American screenwriters

- American television personalities

- American voice actors

- Animated film directors

- Burials at Forest Lawn Memorial Park (Glendale)

- California Republicans

- Cancer deaths in California

- Congressional Gold Medal recipients

- Deaths from lung cancer

- Disney comics writers

- Disney people

- English-language film directors

- Film studio executives

- American artists of German descent

- American writers of German descent

- Illinois Republicans

- American writers of Irish descent

- American people of Canadian descent

- American people of English descent

- American people of French descent

- Kansas City Art Institute alumni

- National Inventors Hall of Fame inductees

- People from Chicago, Illinois

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- School of the Art Institute of Chicago alumni

- Animated film producers