La Marseillaise

| English: The Marseillaise | |

|---|---|

The Marseillais volunteers departing, sculpted on the Arc de Triomphe | |

National anthem of | |

| Also known as | Chant de Guerre pour l'Armée du Rhin (English: War song for the Army of the Rhine) |

| Lyrics | Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle, 1792 |

| Music | Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle |

| Adopted | 1795–1799, 1870 |

| Audio sample | |

"La Marseillaise" (Instrumental) | |

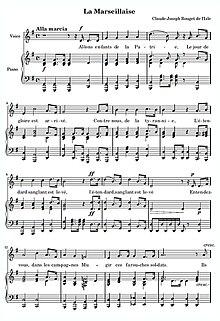

"La Marseillaise" (/ˌmɑːrsəˈleɪz, ˌmɑːrseɪˈ(j)ɛz/ MAR-sə-LAYZ, MAR-say-(Y)EZ, French: [la maʁsɛjɛːz]) is the national anthem of France. The song was written in 1792 by Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle in Strasbourg after the declaration of war by France against Austria, and was originally titled "Chant de guerre pour l'Armée du Rhin" ("War Song for the Army of the Rhine").

The French National Convention adopted it as the Republic's anthem in 1795. The song acquired its nickname after being sung in Paris by volunteers from Marseille marching to the capital. The song is the first example of the "European march" anthemic style. The anthem's evocative melody and lyrics have led to its widespread use as a song of revolution and its incorporation into many pieces of classical and popular music.

History

As the French Revolution continued, the monarchies of Europe became concerned that revolutionary fervor would spread to their countries. The War of the First Coalition was an effort to stop the revolution, or at least contain it to France. Initially, the French army did not distinguish itself, and Coalition armies invaded France. On 25 April 1792, baron Philippe-Frédéric de Dietrich, the mayor of Strasbourg, requested his guest Rouget de Lisle compose a song "that will rally our soldiers from all over to defend their homeland that is under threat".[1] That evening, Rouget de Lisle wrote "Chant de guerre pour l'Armée du Rhin"[2] (English: "War Song for the Army of the Rhine"), and dedicated the song to Marshal Nicolas Luckner, a Bavarian in French service from Cham.[3] A plaque on the building on Place Broglie where De Dietrich's house once stood commemorates the event.[4] De Dietrich was executed the next year during the Reign of Terror.[5]

The melody soon became the rallying call to the French Revolution and was adopted as "La Marseillaise" after the melody was first sung on the streets by volunteers (fédérés in French) from Marseille by the end of May. These fédérés were making their entrance into the city of Paris on 30 July 1792 after a young volunteer from Montpellier called François Mireur had sung it at a patriotic gathering in Marseille, and the troops adopted it as the marching song of the National Guard of Marseille.[2] A newly graduated medical doctor, Mireur later became a general under Napoléon Bonaparte and died in Egypt at age 28.[6]

The song's lyric reflects the invasion of France by foreign armies (from Prussia and Austria) that were under way when it was written. Strasbourg itself was attacked just a few days later. The invading forces were repulsed from France following their defeat in the Battle of Valmy. As the vast majority of Alsatians did not speak French, a German version ("Auf, Brüder, auf dem Tag entgegen") was published in October 1792 in Colmar.[7]

The Convention accepted it as the French national anthem in a decree passed on 14 July 1795, making it France's first anthem.[8] It later lost this status under Napoleon I, and the song was banned outright by Louis XVIII and Charles X, only being re-instated briefly after the July Revolution of 1830.[9] During Napoleon I's reign, "Veillons au salut de l'Empire" was the unofficial anthem of the regime, and in Napoleon III's reign, it was "Partant pour la Syrie". During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, "La Marseillaise" was recognised as the anthem of the international revolutionary movement; as such, it was adopted by the Paris Commune in 1871, albeit with new lyrics under the title "La marseillaise de la Commune". Eight years later, in 1879, it was restored as France's national anthem, and has remained so ever since.[9]

Musical

Several musical antecedents have been cited for the melody:

- Tema e variazioni in Do maggiore, a work by the Italian violinist Giovanni Battista Viotti (composed in 1781);[10][11] the dating of the manuscript has been questioned.[12]

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's Allegro maestoso from the Piano Concerto No. 25 (composed in 1786).[13] Audio of theme

- the oratorio Esther by Jean Baptiste Lucien Grison (composed in 1787).[14][15][16] Audio of excerpts compared

Other attributions (the credo of the fourth mass of Holtzmann of Mursberg[17]) have been refuted.[18]

Rouget de Lisle himself never signed the score of "La Marseillaise".

Lyrics

Only the first stanza (and sometimes the fourth and sixth) and the first chorus are sung today in France. There are some slight historical variations in the lyrics of the song; the following is the version listed at the official website of the French presidency.[19]

Allons enfants de la Patrie, |

Arise, children of the Fatherland, |

Additional verses

These verses were omitted from the national anthem.

Dieu de clémence et de justice |

God of mercy and justice |

Notable arrangements

"La Marseillaise" was arranged for soprano, chorus and orchestra by Hector Berlioz in about 1830.[21]

Franz Liszt wrote a piano transcription of the anthem.[22]

During World War I, bandleader James Reese Europe played a jazz version of "La Marseillaise"[23], which can be heard on part 2 of the Ken Burns 2001 TV documentary Jazz.

Serge Gainsbourg recorded a reggae version in 1978, titled "Aux armes et cætera".[24]

Jacky Terrasson also recorded a jazz version of "La Marseillaise", included in his 2001 album A Paris.[25]

Adaptations in other musical works

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2019) |

- During the French Revolution, Giuseppe Cambini published Patriotic Airs for Two Violins, in which the song is quoted literally and as a variation theme, with other patriotic songs.

- Gioachino Rossini quotes "La Marseillaise" in his 1813 opera, L'italiana in Algeri, during the choral introduction to Isabella's 2nd act aria "Pensa alla patria" and in the second act of his opera Semiramide (1823).

- Robert Schumann used part of "La Marseillaise" for "Die beiden Grenadiere" (The Two Grenadiers), his 1840 setting (Op. 49, No. 1) of Heinrich Heine's poem "Die Grenadiere". The quotation appears at the end of the song when the old French soldier dies. Schumann also incorporated "La Marseillaise" as a major motif in his overture Hermann und Dorothea, inspired by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and quotes it, in waltz rhythm, in the first movement of Faschingsschwank aus Wien, for solo piano.

- Richard Wagner also quotes from "La Marseillaise" in his 1839–40 setting of a French translation of Heine's poem.

- In Orphée aux enfers (1858), Jacques Offenbach quotes it in the "Choeur de la Révolte" (Revolutionary Chorus) in act 1, scene 2.

- Giuseppe Verdi quotes from "La Marseillaise" in his patriotic cantata Hymn of the Nations, which also incorporates "God Save the King" and "Il Canto degli Italiani". It features in a 1944 film, into which the Italian conductor Arturo Toscanini also incorporated "The Internationale" for the Soviet Union and "The Star-Spangled Banner" representing the United States.

- Greek composer Pavlos Carrer quotes "La Marseillaise" in the overture of his 1873 opera Maria Antonietta (libretto by Count Georgios Romas).

- Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky quotes "La Marseillaise" to represent the invading French army in his 1812 Overture (1882). He also quotes the Russian national anthem he was familiar with to represent the Russian army. However, neither of these anthems was actually in use in 1812.

- In 1896, Umberto Giordano briefly quotes the anthem in his opera Andrea Chénier.

- Claude Debussy quotes a fragment of the anthem marked "de très loin" in the dreamlike and dissonant coda of his piano prelude, Feux d'artifice.

- Flemish composer Peter Benoit quotes "La Marseillaise" in the overture of his 1876 opera Charlotte Corday.

- Edward Elgar quotes the opening of "La Marseillaise" in his choral work The Music Makers, Op. 69 (1912), based on Arthur O'Shaughnessy's Ode, at the line "We fashion an empire's glory", where he also quotes the opening phrase of "Rule, Britannia!".

- Felix Weingartner incorporated fragments of the "Marseillaise", as well as of the Russian anthem God Save the Tsar!, the Kaiser's anthem Heil dir im Siegerkranz and of the Austrian anthem Gott erhalte Franz den Kaiser in his concert overture Aus ernster Zeit, reflecting the major opponents of World War I.

- Heitor Villa-Lobos quotes "La Marseillaise" in his 3rd ("War") and 4th ("Victory") Symphonies (both 1919). In the finale of No. 3, fragments of it form a collage with the Brazilian national anthem.

- Dmitri Shostakovich quotes "La Marseillaise" at some length during the fifth reel of the film score he composed for the 1929 silent movie, The New Babylon (set during the Paris Commune), where it is juxtaposed contrapuntally with the famous "Infernal Galop" from Offenbach's Orpheus in the Underworld.[26]

- Gottfried Huppertz quotes "La Marseillaise" in his score for the 1927 film Metropolis over scenes of rioting workers.

- Max Steiner weaves quotes from "La Marseillaise" throughout his score for the 1942 film Casablanca. It also forms an important plot element when patrons of Rick's Café Américain, spontaneously led by Czech underground leader Victor Laszlo, sing the actual song to drown out Nazi officers who had started singing "Die Wacht am Rhein", thus causing Rick's to be shut down. The scene is reminiscent of one in Jean Renoir's La Grande Illusion, in which French and British prisoners of war performing amateur theatricals to a mixed audience of guards and fellow-prisoners sing the song aggressively at the Germans upon hearing of a minor French victory.

- Django Reinhardt uses the theme in "Échos de France".

- The Beatles hit single of 1967, "All You Need Is Love", uses the opening bars of "La Marseillaise" as an introduction.[27]

- The Slovenian music group Laibach released the album Volk in 2006, which featured interpretations of various national anthems and included "Francia", a song inspired by "La Marseillaise".

- In Peru and Chile, both the Partido Aprista Peruano ("La Marsellesa Aprista"),[28] and the Socialist Party of Chile ("La Marsellesa Socialista"),[29] wrote their own versions of "La Marseillaise" to be their anthems. Both use the original tune.

- The Canadian post-hardcore band Silverstein uses the English translation of the first two choruses of "La Marseillaise" in their song "La Marseillaise". The song is featured on their album Short Songs.

- Hip hop group A Tribe Called Quest uses a sample of "La Marseillaise," taken from The Beatles song "All You Need Is Love," as an intro to their song "Luck of Lucien" on their 1990 album People's Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm.

- American song parodist and comedian Allan Sherman, on his album My Son, the Nut, uses the tune of "La Marseillaise" as part of the opening of his song "You Went the Wrong Way, Old King Louie" (a French Revolution-themed parody of "You Came a Long Way from St. Louis"), solemnly intoning "Louis the Sixteenth was the king of France, in 17–89 ..."

Notable use in other media

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2019) |

- Stefan Zweig narrates the creation of the anthem by Rouget De Lisle in one of the Decisive Moments in History, as does Alexandre Dumas in The Countess de Charny, claiming his account comes from Rouget de Lisle's own mouth.

- Abel Gance's film Napoléon (1927) features Harry Krimer as Rouget de Lisle and dramatizes the adoption of his song as the revolution's anthem at the Club of the Cordeliers in 1792.

- The 1938 film La Marseillaise shows the Marseille fédérés marching to Paris and singing the anthem.

- In the RKO film Joan of Paris (1942), "La Marseillaise" is sung by a classroom full of young schoolchildren as the Gestapo hunts their teacher, a French Resistance operative.

- "La Marseillaise" was famously used in Casablanca (1942) at the behest of Victor Laszlo (Paul Henreid) to drown out a group of German soldiers singing "Die Wacht am Rhein". It was also played during the closing card of the movie. Earlier, it appeared in Jean Renoir's La Grande Illusion in a similar defiant fashion, sung by French and British POWs.

- The British sitcom 'Allo 'Allo! spoofed Casablanca by having the patriotic French characters start singing "La Marseillaise", only to switch to Deutschlandlied when Nazi officers enter their café.

- On the January 24, 1977, episode of the Steve Allen PBS fantasy/history talk show Meeting of Minds, Empress Marie Antoinette (played by Allen's wife Jayne Meadows) is introduced and walks onstage to "La Marseillaise", and immediately expresses outrage and distress, explaining that the anthem was that of the revolutionary movement that dethroned and executed herself and husband Louis XVI. Allen as host apologizes profusely for the faux pas.

- Vanessa Redgrave sings "La Marsellaise" (in French) in the closing scene of Playing for Time, a 1980 CBS television film about the Auschwitz concentration camp.

- In the biopic La Vie en rose, chronicling the life of Édith Piaf, ten-year-old Édith is urged by her acrobat father to "do something" in the middle of a lackluster show, and she amazes the audience with an emotional rendition of "La Marseillaise".

- The carillon of the town hall in the Bavarian town of Cham plays "La Marseillaise" every day at 12.05 pm to commemorate the French Marshal Nicolas Luckner, who was born there.[30]

- In the Stanley Kubrick film Paths of Glory (1957), "La Marseillaise" is played instrumentally during the opening credits.

- The Brisbane Lions Australian Rules football team's theme song has been set to "La Marseillaise" since 1962. Numerous other minor Australian rules football teams also use the song.[31][32]

Historical Russian use

In Russia, "La Marseillaise" was used as a republican revolutionary anthem by those who knew French starting in the 18th century, almost simultaneously with its adoption in France. In 1875 Peter Lavrov, a narodist revolutionary and theorist, wrote a Russian-language text (not a translation of the French one) to the same melody. This "Worker's Marseillaise" became one of the most popular revolutionary songs in Russia and was used in the Revolution of 1905. After the February Revolution of 1917, it was used as the semi-official national anthem of the new Russian republic. Even after the October Revolution, it remained in use for a while alongside The Internationale.[33]

Criticism and controversy

The English philosopher and reformer Jeremy Bentham, who was declared an honorary citizen of France in 1791 in recognition of his sympathies for the ideals of the French Revolution, was not enamoured of "La Marseillaise". Contrasting its qualities with the "beauty" and "simplicity" of "God Save the King", he wrote in 1796:

The War whoop of anarchy, the Marseillais Hymn, is to my ear, I must confess, independently of all moral association, a most dismal, flat, and unpleasing ditty: and to any ear it is at any rate a long winded and complicated one. In the instance of a melody so mischievous in its application, it is a fortunate incident, if, in itself, it should be doomed neither in point of universality, nor permanence, to gain equal hold on the affections of the people.[34]

Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, a former President of France, has said that it is ridiculous to sing about drenching French fields with impure Prussian blood as a German Chancellor takes the salute in Paris.[35] A 1992 campaign to change the words of the song involving more than 100 prominent French citizens, including Danielle Mitterrand, wife of then-President François Mitterrand, was unsuccessful.[36]

The British historian Simon Schama discussed "La Marseillaise" on BBC Radio 4's Today programme on 17 November 2015 (in the immediate aftermath of the Paris attacks), saying it was "... the great example of courage and solidarity when facing danger; that's why it is so invigorating, that's why it really is the greatest national anthem in the world, ever. Most national anthems are pompous, brassy, ceremonious, but this is genuinely thrilling. Very important in the song ... is the line 'before us is tyranny, the bloody standard of tyranny has risen'. There is no more ferocious tyranny right now than ISIS, so it's extremely easy for the tragically and desperately grieving French to identify with that".[37]

See also

- "Marche Henri IV", the national anthem of the Kingdom of France

- "La Marseillaise des Blancs", the Royal and Catholic variation

- "Ça Ira", another famous anthem of the French Revolution

- "Chant du départ", the official anthem of the Napoleonic Empire

- "Belarusian Marseillaise", a patriotic song in Belarus

- "Onamo", a Montenegrin patriotic song popularly known as the "Serbian Marseillaise"

- "The Women's Marseillaise", a women's suffrage protest song

References

- ^ "La Marseillaise" (in French). National Assembly of France. Archived from the original on 15 May 2012. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ a b Weber, Eugen (1 June 1976). Peasants into Frenchmen: The Modernization of Rural France, 1870–1914. Stanford University Press. p. 439. ISBN 978-0-8047-1013-8. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ Stevens, Benjamin F. (January 1896). "Story of La Marseillaise". The Musical Record (408). Boston, Massachusetts: Oliver Ditson Company: 2. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ "Plaque Frédéric De Dietrich". Archi-Wiki. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ^ (in French) Louis Spach, Frederic de Dietrich, premier maire de Strasbourg., Strasbourgh, Vve. Berger-Levrault & fils, 1857.

- ^ "General François Mireur". Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- ^ Wochenblatt, dem Unterricht des Landvolks gewidmet, Colmar 1792 [1].

- ^ Mould, Michael (2011). The Routledge Dictionary of Cultural References in Modern French. New York: Taylor & Francis. p. 147. ISBN 978-1-136-82573-6. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- ^ a b Paul Halsall (1997),Modern History Sourcebook: "La Marseillaise", 1792.[better source needed]

- ^ "La Marseillaise, un hymne à l'histoire tourmentée" by Romaric Godin, La Tribune, 20 November 2015 (in French)

- ^ Micaela Ovale & Guilia Mazzetto. "Progetti Viotti" (PDF). Guido Rimonda (in Italian). Guido Rimonda. Retrieved 24 August 2019.

Basti ricordare che "La Marsigliese" nasce da un tema con variazioni di Viotti scritto nel 1781, ben 11 anni prima della comparsa dell'inno nazionale francese ufficiale. English Translation Just remember that "La Marsigliese" was born from a theme with variations by Viotti written in 1781, 11 years before the appearance of the official French national anthem

- ^ La Face, Giuseppina. "La Marsigliese e il mistero attorno alla sua paternità". il fatto quotidiano. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

A dicembre la Camerata Ducale, diretta dal violinista Guido Rimonda, ha eseguito un Tema con variazioni per violino e orchestra sulla Marsigliese, attribuito al grande compositore vercellese Giovan Battista Viotti. Rimonda, che per la Decca sta registrando gli opera omnia dell'illustre concittadino, possiede un manoscritto del Tema con variazioni firmato "GB Viotti" e datato "1781"....... Nel libriccino che accompagna il CD Decca del 2013, è riprodotta la prima pagina del manoscritto. Secondo un esperto di Viotti, il canadese Warwick Lister (Ad Parnassum, XIII, aprile 2015), la firma di Viotti in alto a destra potrebbe essere autentica, ma le parole "2 mars 1781" sono di un'altra mano. Non si può dunque escludere che Viotti abbia davvero scritto una serie di variazioni su un tema che tutt'Europa conobbe a metà degli anni 1790; ma l'idea che il brano risalga al decennio precedente, e che la paternità musicale dell'inno vada girata a un violinista vercellese, è appesa all'esile filo di una data d'incerta mano su un manoscritto d'incerta provenienza. Translation: In December the Camerata Ducale, conducted by the violinist Guido Rimonda , performed a Theme with variations for violin and orchestra on the Marseillaise , attributed to the great Vercelli composer Giovan Battista Viotti . Rimonda, who for the Decca is recording the opera omnia of the illustrious fellow citizen, owns a manuscript of the Theme with variations signed "GB Viotti" and dated "1781"....... In the booklet accompanying the 2013 Decca CD, the first page of the manuscript is reproduced. According to an expert from Viotti, the Canadian Warwick Lister ( Ad Parnassum, XIII, April 2015), Viotti's signature on the top right may be authentic, but the words "2 mars 1781" are from another hand. It cannot therefore be excluded that Viotti actually wrote a series of variations on a theme that all of Europe knew in the mid-1790s; but the idea that the piece dates back to the previous decade, and that the musical authorship of the hymn should be turned to a Vercelli violinist, hangs on the slender thread of a date of uncertain hand on a manuscript of uncertain origin.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Lot, Arthur (1886). "La Marseillaise: enquête sur son véritable auteur". Google Books. V. Palmé, 1886; Nouvelles Éditions Latines 1992. p. 11. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

Cette partition musicale, que ma famille possède toujours, avait été écrite par Jean-Baptiste Lucien Grisons, chef de maîtrise à la cathédrale de Saint-Omer de 1775 à 1787. Or l'air des Stances sur la Calamnie, par laquelle débute cet oratorio, n'est autre que l'air de la Marseillaise. English Translation: This musical score, which my family still owns, was written by Jean-Baptiste Lucien Grisons, chief of master at the cathedral of Saint-Omer from 1775 to 1787. Now the tune of Stances on Calamnia, with which this oratorio begins , is none other than the air of the Marseillaise.

- ^ Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

- ^ "La Marseillaise". en.wikisource.org. Wikipedia. 1905. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

Rouget wrote the words during the night, adapting the music probably from the Oratorio Esther, by Jean Baptiste Lucien Grison, and calling it the Chant de guerre de l'armée du Rhin.

- ^ Ripley, George; Dana, Charles A., eds. (1879). . The American Cyclopædia. See also Geschichte eines deutschen Liedes at German Wikisource.

- ^ Istel, Edgar (April 1922). "Is the Marseillaise a German composition? (The history of a hoax)". The Musical Quarterly. 8 (2): 213–226. doi:10.1093/mq/viii.2.213. JSTOR 738232.

- ^ La Marseillaise, l'Elysée.

- ^ The seventh verse was not part of the original text; it was added in 1792 by an unknown author.

- ^ William Apthorp (1879) Hector Berlioz; Selections from His Letters, and Aesthetic, Humorous, and Satirical Writings, Henry Holt, New York

- ^ L.J. de Bekker (1909) Stokes' Encyclopedia of Music and Musicians, Frederick Stokes, New York

- ^ Williams, Chad L. (2013). Torchbearers of Democracy African American Soldiers in the World War I Era. The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-4696-0496-1. OCLC 957516717.

- ^ "Scandales du XXe siècle – Gainsbourg métisse 'La Marseillaise'" (1 September 2006) Le Monde, Paris (in French)

- ^ "La Marseillaise". Shazam. Apple Inc. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- ^ Described and played on BBC Radio 3's CD Review program (14 January 2012)

- ^ Edwards, Gavin; Edwards, Gavin (28 August 2014). "How the Beatles' 'All You Need Is Love' Made History". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ "La Marsellesa Aprista" Archived 18 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Partido Aprista Peruano, Official Website

- ^ Boletín del Comité Central del PSCH N°34–35, April–May 1973.

- ^ Cham.de Archived 28 January 1999 at archive.today

- ^ "Origins of our Club song". Brisbane Lions. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- ^ "Serif's WebPlus.net hosting service has now closed!". www.ozsportshistory.com. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- ^ Соболева, Н.А. 2005. Из истории отечественных государственных гимнов. Журнал "Отечественная история", 1. P.10-12 Archived 16 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bentham, Jeremy (2001). Quinn, Michael (ed.). Writings on the Poor Laws, Vol. I. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-0199242320.

- ^ Bremner, Charles (14 May 2014). "Cannes star denounces 'racist' Marseillaise at festival opening". The Times. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ Riding, Alan (5 March 1992). "Aux Barricades! 'La Marseillaise' Is Besieged". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ "Simon Schama explains La Marseillaise". BBC News. 17 November 2015. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

Further reading

- Charles Hughes, "Music of the French Revolution", Science & Society, vol. 4, No. 2 (Spring 1940), pp. 193–210. In JSTOR.

External links

- La Marseillaise de Rouget de Lisle – Official site of Élysée – Présidence de la République (in French)

- La Marseillaise: hymne national Official site of Assemblée nationale (in French)

- La Marseillaise, Iain Patterson's comprehensive website

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- La Marseillaise

- "Marseillaise, The". The Nuttall Encyclopædia. 1907.

- "Marseillaise". Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

- 1792 compositions

- Songs of the French Revolution

- French anthems

- National symbols of France

- World Digital Library

- French military marches

- French patriotic songs

- National anthems

- North American anthems

- South American anthems

- Oceanian anthems

- European anthems

- National anthem compositions in G major

- National anthem compositions in B-flat major