Oxymorphone

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Opana |

| Other names | 14-Hydroxydihydromorphinone |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a610022 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Dependence liability | High |

| Routes of administration | Oral, Intravenous, intramusucular, subcutaneous, rectal, intranasal |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Oral: 10% Intranasal: 43%[1] IV, IM: 100%[2] |

| Protein binding | 10%[2] |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (CYP3A4, glucuronidation)[2] |

| Elimination half-life | 7–9 hours[2] |

| Excretion | Urine, feces[2] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.873 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

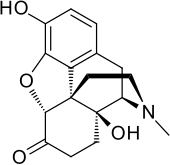

| Formula | C17H19NO4 |

| Molar mass | 301.33706 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Oxymorphone (brand names Opana, Numorphan, Numorphone), also known as 14-hydroxydihydromorphinone, is a powerful semi-synthetic opioid analgesic (painkiller) first developed in Germany in 1914,[3] patented in the USA by Endo Pharmaceuticals in 1955[4] and introduced to the United States market in January 1959 and other countries around the same time.[2]

The brand name Numorphan is derived by analogy to the Nucodan name for an oxycodone product (or vice versa) as well as Paramorphan/Paramorfan for dihydromorphine and Paracodin (dihydrocodeine). The only commercially available salt of oxymorphone in most of the world at this time is the hydrochloride, which has a free base conversion ratio of 0.891, and oxymorphone hydrochloride monohydrate has a factor of 0.85.[5] It is a Schedule II controlled substance in the United States with an ACSCN of 9652. The 2013 DEA annual manufacturing quotas were 18 375 kilos for conversion (a number of drugs can be made from oxymorphone, both painkillers and opioid antagonists like naloxone) and 6875 kilos for direct manufacture of end-products.[6]

The onset of analgesia after parenteral administration is about 5–10 minutes and after rectal administration, 15–30 minutes.[2] The duration of analgesia is 3–4 hours for immediate-release tablets and 12 hours for extended-release tablets.[2] Oxymorphone is also a minor metabolite of oxycodone, which is formed by CYP2D6-mediated O-demethylation.[2]

Uses

Oxymorphone is indicated for the relief of moderate to severe pain and also as a preoperative medication to alleviate apprehension, maintain anaesthesia and as an obstetric analgesic. Additionally, it can be used for the alleviation of pain in patients with dyspnoea associated with acute left ventricular failure and pulmonary oedema (Brit.), or edema (Amer.).[5] It is practically devoid of antitussive activity.[5]

Opana extended-release tablets are indicated for the management of chronic pain and are indicated only for patients already on a regular schedule of strong opioids for a prolonged period. The immediate-release Opana tablets are recommended for management of breakthrough pain for patients on the extended-release version. Some protocols for chronic pain conditions characterised by severe breakthrough pain incidents add Numorphan ampoules as a third form of the drug for use when a breakthrough pain incident is in progress. An oxymorphone nasal spray is being developed for this purpose but the release date is unknown; some practitioners prefer fentanyl immediate-release formulations such as Actiq or Fentora for this purpose although some patients have severe side effects from fentanyl.[2]

Oxymorphone is mentioned, along with buprenorphine, oxycodone, dihydrocodeine, morphine and other opioids as a possible means of mitigating refractory depression.[7][8][9]

Adverse effects

The principal adverse effects of oxymorphone are similar to other opioids with constipation, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, dry mouth and drowsiness being the most common adverse effects. This drug is highly addictive as with other opioids and can lead to chemical dependence and withdrawal.[5]

Overdose

In common with other opioids, oxymorphone overdosage is characterized by respiratory depression, extreme somnolence progressing to stupor or coma, skeletal muscle flaccidity, cold and clammy skin, and sometimes bradycardia and hypotension. In a severe case of overdose, apnoea, circulatory collapse, cardiac arrest and death may occur.[5]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

It elicits its effects by binding to and activating the mu opioid receptor (MOR) and, to a lesser extent, the delta opioid receptor (DOR).[2] Its activity at the DOR likely augments its action at the MOR.[2] Oxymorphone is 10 times more potent than morphine.[10]

Pharmacokinetics

Chemistry

Oxymorphone is commercially produced from thebaine, which is a minor constituent of the opium poppy (Papaver somniferum) but thebaine is found in greater abundance (3%) in the roots of the oriental poppy (Papaver orientale).[2][11] German patents from the middle 1930s indicate that oxymorphone as well as hydromorphone, hydrocodone, oxycodone, and acetylmorphone can be prepared—without the need for hydrogen gas—from solutions of codeine, morphine, and dionine by refluxing an acidic aqueous solution, or the precursor drug dissolved in ethanol, in the presence of Column 7 metals, namely palladium and platinum in fine powder or colloidal form or platina black. It is unclear from information available if aluminium or nickel can be used as a catalyst in these reactions as well.[12]

Oxymorphone hydrochloride occurs as odourless white crystals or white to off-white powder. It darkens in colour with prolonged exposure to light. One gram of oxymorphone hydrochloride is soluble in 4 ml of water and it is sparingly soluble in alcohol and ether. It degrades upon contact with light.[5]

Oxymorphone can be acetylated like morphine, hydromorphone, and some other opioids. Mono-, di-, tri-, and tetra- esters of oxymorphone were developed in the 1930s but are not used in medicine at this time. Presumably other esters such as nicotinyl, benzoyl, formyl, cinnimoyl &c.can be produced

Society and culture

Brand names

- Numorphan (suppository and injectable solution)

- Opana ER (extended-release tablet)

- Opana IR (immediate-release tablet)

- O-Morphon (10 mg tablet and 1 mg/1ml injection) in Bangladesh by Ziska pharmaceutical ltd.

Other manufacturers and Endo themselves have also, according to reports in the mass media and professional journals[who?] over the last few years, considered and/or are currently developing a Duragesic-style oxymorphone skin plasters and oxymorphone and hydromorphone nasal sprays.

Generic pill markings:

ATV10/APO; HK10 (10 mgs) oblong white

ATV20/APO; HK20 (20mgs) oblong white

Abuse and overdose

In the United States, more than 12 million people abuse opioid drugs at least once a year.[13] In 2010, 16,652 deaths were related to opioid overdose.[14] In September 2013, the FDA released new labeling guidelines for long-acting and extended-release opioids requiring manufacturers to remove moderate pain as indication for usage, instead stating the drug is for "pain severe enough to require daily, around-the-clock, long-term opioid treatment".[15] The updated labeling will not restrict physicians from prescribing opioids for moderate, as needed usage.[13]

In January 2013, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported an illness associated with intravenous (IV) abuse of oral Opana ER (oxymorphone) in Tennessee. The clinical presentation of this syndrome was reported to resemble that of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP).[16] Initial therapy included the utilization of therapeutic plasma exchange, a mainstay initial treatment for TTP. However, Miller et al. reported no ADAMTS13 activity deficiency nor identifiable antibody to ADAMTS13 as seen in TTP indicating a thrombotic microangiopathy of different underlying etiology. If IV Opana abuse is acknowledged, consideration of supportive care, in lieu of treatment with therapeutic plasma exchange could be considered.[17]

In late March 2015, reports indicated Austin, Indiana, was the center of an outbreak of HIV caused by the use of Oxymorphone as an injectable recreational drug. The outbreak required emergency action by state officials.[18][19][20]

The NPR podcast "embedded" episode of March 31, 2016 is an in depth account of a visit to Opana abusers in Austin, Indiana. The current street price of Opana is reported to be $140.[21]

Synthesis

See also

- Opioids

- Oxymorphone hydrazone

- Oxymorphol - a metabolite of oxymorphone and an intermediate in the creation of hydromorphone

- Hydromorphone

- Oxycodone

- Drug addiction

References

- ^ Hussain, Munir A.; Aungst, Bruce J. (1997). "Intranasal Absorption of Oxymorphone". Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 86 (8): 975–6. doi:10.1021/js960513x. PMID 9269879.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Davis, MP; Glare, PA; Hardy, J (2009) [2005]. Opioids in Cancer Pain (2nd ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-157532-7.

- ^ Sinatra, Raymond (2010). The Essence of Analgesia and Analgesics. MA, USA: Cambridge University Press; 1 edition. p. 123. ISBN 978-0521144506.

- ^ US patent 2806033, Mozes Juda Leweustein, "Morphine derivative", published 1955-03-08, issued 1957-10-09

- ^ a b c d e f Brayfield, A, ed. (30 January 2013). "Oxymorphone Hydrochloride". Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. Pharmaceutical Press. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ^ http://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/fed_regs/quotas/2013/fr0620.htm

- ^ Stoll AL, Rueter S (December 1, 1999). "Treatment augmentation with opiates in severe and refractory major depression". Am J Psychiatry. 156 (12): 2017. doi:10.1176/ajp.156.12.2017 (inactive 2016-06-18). PMID 10588427. Retrieved 2009-03-03.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of June 2016 (link) - ^ Schürks M, Overlack M, Bonnet U (March 2005). "Naltrexone treatment of combined alcohol and opioid dependence: deterioration of co-morbid major depression". Pharmacopoeia. 38 (2): 100–2. doi:10.1055/s-2005-837812. PMID 15744636.

- ^ Tejedor-Real P, Mico JA, Maldonado R, Roques BP, Gibert-Rahola J (September 1995). "Implication of endogenous opioid system in the learned helplessness model of depression". Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 52 (1): 145–52. doi:10.1016/0091-3057(95)00067-7. PMID 7501657.

- ^ Prommer, E (February 2006). "Oxymorphone: a review". Supportive Care in Cancer. 14 (2): 109–15. doi:10.1007/s00520-005-0917-1. PMID 16317569.

- ^ Corrigan, D; Martyn, EM (May 1981). "The thebaine content of ornamental poppies belonging to the papaver section oxytona". Planta Medica. 42 (1): 45–9. doi:10.1055/s-2007-971544. PMID 17401879.

- ^ "Dihydromorphinones from Morphine and Analogs - [www.rhodium.ws]". Erowid.org. Retrieved 2012-11-03.

- ^ a b Girioin, Lisa; Haely, Melissa (11 September 2013). "FDA to require stricter labeling for pain drugs". Los Angeles Times. pp. A1 and A9.

- ^ "Drug Overdose in the United States: Fact Sheet". Centers for Disease Control. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ "ER/LA Opioid Class Labeling Changes and Postmarket Requirements" (PDF). FDA. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC) (2013). "Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP)-like illness associated with intravenous Opana ER abuse--Tennessee, 2012". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 62 (1): 1–4. PMID 23302815.

- ^ Miller, Peter John; Farland, Andrew Matthew; Knovich, Mary Ann; Batt, Katharine Marie; Owen, John (2014). "Successful treatment of intravenously abused oral Opana ER-induced thrombotic microangiopathy without plasma exchange". American Journal of Hematology. 89 (7): 695–7. doi:10.1002/ajh.23720. PMID 24668845.

- ^ Paquette, Danielle (30 March 2015). "How an HIV outbreak hit rural Indiana — and why we should be paying attention". Washington Post. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ^ Conrad, C; Bradley, H. M.; Broz, D; Buddha, S; Chapman, E. L.; Galang, R. R.; Hillman, D; Hon, J; Hoover, K. W.; Patel, M. R.; Perez, A; Peters, P. J.; Pontones, P; Roseberry, J. C.; Sandoval, M; Shields, J; Walthall, J; Waterhouse, D; Weidle, P. J.; Wu, H; Duwve, J. M.; Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC) (2015). "Community Outbreak of HIV Infection Linked to Injection Drug Use of Oxymorphone--Indiana, 2015". MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 64 (16): 443–4. PMID 25928470.

- ^ Strathdee, S. A.; Beyrer, C (2015). "Threading the Needle--How to Stop the HIV Outbreak in Rural Indiana". New England Journal of Medicine. 373 (5): 397–9. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1507252. PMID 26106947.

- ^ http://www.npr.org/podcasts/510311/embedded[full citation needed]

- ^ Weiss, U. (1955). "Derivatives of Morphine. I. 14-Hydroxydihydromorphinone". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 77 (22): 5891. Bibcode:1955JAChS..77.1678G. doi:10.1021/ja01627a033.