Parvati

| Parvati | |

|---|---|

| Member of Tridevi and Pancha Prakriti | |

Parvati with her son Ganesha | |

| Other names | Uma, Gauri, Aparna, Durga, Kali, Girija, Haimavati, Ambika, Bhavani |

| Sanskrit transliteration | Pārvatī |

| Devanagari | पार्वती |

| Affiliation | Devi, Shakti, Mahadevi, Tridevi, Sati, Durga, Kali, Navadurga, Mahavidyas |

| Abode | Kailasha, Manidvipa |

| Mantra | Sarvamaṅgalamāṅgalye Śive Sarvārthasādhike । Śaraṇye Tryambake Gauri Nārāyaṇi Namo'stu Te ।। |

| Day | Monday & Friday |

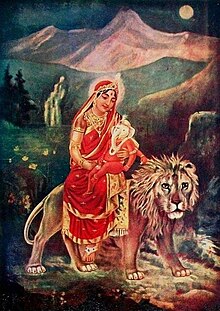

| Mount | Lion and Tiger |

| Texts | Devi-Bhagavata Purana, Mahabhagavata Purana, Devi Mahatmya, Kalika Purana, Shakta Upanishads, Tantras |

| Festivals | Navaratri, Vijayadashami, Teej, Bathukamma, Gauri Habba |

| Genealogy | |

| Parents | Himavan (father) Maināvati (mother)[7][8] |

| Siblings | Ganga (elder sister)[5] Mainaka (elder brother)[6] |

| Consort | Shiva |

| Children | |

| Part of a series on |

| Shaktism |

|---|

|

|

|

Parvati (Sanskrit: पार्वती, IAST: Pārvatī), also known as Uma (Sanskrit: उमा, IAST: Umā) and Gauri (Sanskrit: गौरी, IAST: Gaurī), is one of the principal goddesses in Hinduism, revered as the goddess of power, energy, nourishment, harmony, love, beauty, devotion, and motherhood. Along with Lakshmi and Sarasvati, she forms the trinity, known as the Tridevi.[9]

From her first appearance as a goddess during the epic period (400 BCE – 400 CE), Parvati is primarily depicted as the chief consort of the ascetic god Shiva.[10] She is recognised as the reincarnation of Sati, Shiva's first wife, who immolated herself after her father insulted Shiva. Parvati is often equated with the other goddesses such as Sati, Uma, Kali and Durga and due to this close connection, they are often treated as one and the same, with their stories frequently overlapping. In Hindu mythology, the birth of Parvati is primarily understood as a cosmic event meant to lure Shiva out of his ascetic withdrawal and into the realm of marriage and household life. As Shiva's wife, Parvati represents the life-affirming, creative force that complements Shiva's austere, world-denying nature. Her presence in his life draws him from isolation into worldly engagement, thus balancing the two poles of asceticism and householder life in Hindu philosophy. Parvati's role as wife and mother is central to her mythological persona, where she embodies the ideal of the devoted spouse who both supports and expands her husband's realm of influence.[10][11] Parvati is also noted for her motherhood, being the mother of the prominent Hindu deities Ganesha and Kartikeya.[6][12][13]

Philosophically, Parvati is regarded as Shiva’s shakti (divine energy or power), the personification of the creative force that sustains the cosmos. In this role, she becomes not only a mother and nurturer but also the embodiment of cosmic energy and fertility. She is the source of power that energises Shiva, who without her is incomplete. Parvati's mythology, therefore, is not just about her role as a wife but also about her cosmic function as the force that activates and sustains life.[10] In various Shaiva traditions, Parvati is also regarded as a model devotee, and even viewed as the embodiment of Shiva's grace, playing a central role in the spiritual liberation of devotees.[10][14][15] She is also one of the central deities in the goddess-oriented sect of Shaktism, where she is regarded as a benevolent aspect of Mahadevi, the supreme deity,[16][17] and is closely associated with various manifestations of Mahadevi, including the ten Mahavidyas and the Navadurgas.[10] Parvati is found extensively in ancient Puranic literature, and her statues and iconography are present in Hindu temples all over South Asia and Southeast Asia.[18][19] In Hindu temples dedicated to her and Shiva, she is symbolically represented as the yoni.[10]

Etymology and nomenclature

[edit]Parvata (पर्वत) is one of the Sanskrit words for "mountain"; "Parvati" derives her name from being incarnated as the daughter of king Himavan (also called Himavata, Parvata) and mother Menavati.[11][12] King Parvata is considered lord of the mountains and the personification of the Himalayas; Parvati implies "she of the mountain". Aparneshara Temple of Yama, Udhampur in the Indian Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir is considered as the birthplace of Parvati and site of Shiva-Parvati Vivaha.[20]

Parvati is known by many names in Hindu literature.[21] Other names which associate her with mountains are Shailaja (Daughter of the mountains), Shailaputri (Daughter of Mountains), Haimavati (Daughter of Himavan), Maheshvari (Maheshvara’s wife), Girirajaputri (Daughter of king of the mountains) and Girija (Daughter of the mountains).[22]

Shaktas consider the Parvati as an incarnation of Lalita Tripurasundari.[23] Two of Parvati's most famous epithets are Uma and Aparna.[24] The name Uma is used for Sati (Shiva's wife, who is the incarnation of Parvati) in earlier texts,[which?] but in the Ramayana, it is used as a synonym for Parvati. In the Harivamsa, Parvati is referred to as Aparna ('One who took no sustenance') and then addressed as Uma, who was dissuaded by her mother from severe austerity by saying u mā ('oh, don't'). Uma also means that "the One born out of Om (The Pranava Mantra)[25] She is also referred to as Ambika ('dear mother'), Shakti ('power'), Mataji ('revered mother'), Maheshwari ('great goddess'), Durga (invincible), Bhairavi ('ferocious'), Bhavani ('fertility and birthing'), Shivaradni ('Queen of Shiva'), Urvi or Renu, and many hundreds of others. Parvati is also the goddess of love and devotion, or Kamakshi (the goddess of fertility), abundance and food/nourishment, or Annapurna.[26] She is also the ferocious Mahakali that wields a sword, wears a garland of severed heads, and protects her devotees and destroys all evil that plagues the world and its beings.

The apparent contradiction that Parvati is addressed as the golden one, Gauri, as well as the dark one, Kali or Shyama, as a calm and placid wife Parvati mentioned as Gauri and as a goddess who destroys evil she is Kali. Regional stories of Gauri suggest an alternate origin for Gauri's name and complexion. In parts of India, Gauri's skin color is golden or yellow in honor of her being the goddess of ripened corn/harvest and fertility.[27][28]

The divine hymns such as Lalita Sahasranama and Mahalakshmi Ashtakam give many

| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

epithets to the goddess based on the demons she had won over such as Mahishasuramardini (‘the One who killed demon Mahishasura’), Raktabeejasamharini (‘the One who killed demon Raktabeeja’), Chamundi (‘the One who killed the demon brothers Chanda and Munda’), Mookambika (‘the killer of Mookasura’), Kolasurabhayankari (‘the killer of Kolasura’), Bhandasuravibedhini (‘the killer of Bhandasura) and many more.

History

[edit]

The word Parvati does not explicitly appear in Vedic literature. Instead, Ambika, Rudrani and others are found in the Rigveda. The verse 3.12 of the Kena Upanishad dated to mid-1st millennium BCE contains a goddess called Uma-Haimavati, a very common alternate name for Parvati.[31] Sayana's commentary in Anuvaka, however, identifies Parvati in the Kena Upanishad, suggesting her to be the same as Uma and Ambika in the Upanishad, referring to Parvati is thus an embodiment of divine knowledge and the mother of the world.[21] She appears as the shakti, or essential power, of the Supreme Brahman. Her primary role is as a mediator who reveals the knowledge of Brahman to the Vedic Trideva of Agni, Vayu, and Varuna, who were boasting about their recent defeat of a group of demons.[32] But Kinsley notes: "it is little more than conjecture to identify her with the later goddess Satī-Pārvatī, although [..] later texts that extol Śiva and Pārvatī retell the episode in such a way to leave no doubt that it was Śiva's spouse.." [IAST original].[31]

Sati-Parvati appears in the epic period (400 BCE–400 CE), as both the Ramayana and the Mahabharata present Parvati as Shiva's wife. However, it is not until the plays of Kalidasa (5th–6th centuries) and the Puranas (4th through the 13th centuries) that the stories of Sati-Parvati and Shiva acquire more comprehensive details. Kinsley adds that Parvati may have emerged from legends of non-aryan goddesses that lived in mountains.[33] While the word Uma appears in earlier Upanisads, Hopkins notes that the earliest known explicit use of the name Pārvatī occurs in late Hamsa Upanishad.[34]

Weber suggests that just like Shiva is a combination of various Vedic gods Rudra and Agni, Parvati in Puranas text is a combination of wives of Rudra. In other words, the symbolism, legends, and characteristics of Parvati evolved fusing Uma, Haimavati, Ambika in one aspect and the more ferocious, destructive Kali, Gauri, Nirriti in another aspect.[21][35] Tate suggests Parvati is a mixture of the Vedic goddesses Aditi and Nirriti, and being a mountain goddess herself, was associated with other mountain goddesses like Durga and Kali in later traditions.[36]

Iconography and symbolism

[edit]

Parvati, the gentle aspect of Devi Shakti, is usually represented as fair, beautiful, and benevolent.[37][38] She typically wears a red dress (often a sari), and may have a head-band. When depicted alongside Shiva she generally appears with two arms, but when alone she may be depicted having four. These hands may hold a trident, mirror, rosary, bell, dish, goad, sugarcane stalk, or flowers (such as a lotus).[39] One of her arms in front may be in the Abhaya mudra (hand gesture for 'fear not'), one of her children, typically Ganesha, is on her knee, while her younger son Skanda may be playing near her in her watch. In ancient temples, Parvati's sculpture is often depicted near a calf or cow. Bronze has been the chief metal for her sculpture, while stone is the next most common material.[39]

Parvati and Shiva are often symbolized by a yoni and a linga, respectively. In ancient literature, yoni means womb and place of gestation, the yoni-linga metaphor represents origin, source or regenerative power.[40] The linga-yoni icon is widespread, found in Shaivite Hindu temples of South Asia and Southeast Asia. Often called Shivalinga, it almost always has both linga and the yoni.[41] The icon represents the interdependence and union of feminine and masculine energies in recreation and regeneration of all life. In some depictions, Parvati and Shiva are shown in various forms of sexual union.[41]

In some iconography, Parvati's hands may symbolically express many mudras (symbolic hand gestures). For example, Kataka — representing fascination and enchantment, Hirana — representing the antelope, the symbolism for nature and the elusive, Tarjani by the left hand—representing the gesture of menace, and Chandrakal — representing the moon, a symbol of intelligence. [citation needed] Kataka is expressed by hands closer to the devotee; Tarjani mudra with the left hand, but far from the devotee.

If Parvati is depicted with two hands, Kataka mudra—also called Katyavalambita or Katisamsthita hasta—is common, as well as Abhaya (fearlessness, fear not) and Varada (beneficence) are representational in Parvati's iconography. Parvati's right hand in Abhaya mudra symbolizes "do not fear anyone or anything", while her Varada mudra symbolizes "wish-fulfilling".[42] In Indian dance, Parvatimudra is dedicated to her, symbolizing divine mother. It is a joint hand gesture, and is one of sixteen Deva Hastas, denoting the most important deities described in Abhinaya Darpana. The hands mimic motherly gesture, and when included in a dance, the dancer symbolically expresses Parvati.[43] Alternatively, if both hands of the dancer are in Ardhachandra mudra, it symbolizes an alternate aspect of Parvati.[44]

Parvati is sometimes shown with golden or yellow color skin, particularly as goddess Gauri, symbolizing her as the goddess of ripened harvests.[45]

In some manifestations, particularly as angry, ferocious aspects of Shakti such as Kali, she has eight or ten arms, and is astride on a tiger or lion, wearing a garland of severed heads and skirt of disembodied hands. In benevolent manifestations such as Kamakshi or Meenakshi, a parrot sits near her right shoulder symbolizing cheerful love talk, seeds, and fertility. A parrot is found with Parvati's form as Kamakshi – the goddess of love, as well as Kama – the cupid god of desire who shoots arrows to trigger infatuation.[46] A crescent moon is sometimes included near the head of Parvati particularly the Kamakshi icons, for her being half of Shiva. In South Indian legends, her association with the parrot began when she won a bet with her husband and asked for his loincloth as victory payment; Shiva keeps his word but first transforms her into a parrot. She flies off and takes refuge in the mountain ranges of south India, appearing as Meenakshi (also spelled Minakshi).[47]

Parvati is expressed in many roles, moods, epithets, and aspects. In Hindu mythology, she is an active agent of the universe, the power of Shiva. She is expressed in nurturing and benevolent aspects, as well as destructive and ferocious aspects.[48] She is the voice of encouragement, reason, freedom, and strength, as well as of resistance, power, action and retributive justice. This paradox symbolizes her willingness to realign to Pratima (reality) and adapts to the needs of circumstances in her role as the universal mother.[48] As Mahakali, she identifies and destroys evil for protection, and as Annapurna, she creates food and abundance for nourishment.

Manifestations

[edit]Several Hindu stories present alternate aspects of Parvati, such as the ferocious, violent aspect as Shakti and related forms. Shakti is pure energy, untamed, unchecked, and chaotic. Her wrath crystallizes into a dark, blood-thirsty, tangled-hair Goddess with an open mouth and a drooping tongue. This goddess is usually identified as the terrible Mahakali (time).[49] In Linga Purana, Parvati undergoes a metamorphosis into Kali, at the request of Shiva, to destroy an asura (demon) Daruk. Even after destroying the demon, Kali's wrath could not be controlled. To lower Kali's rage, Shiva appeared as a crying baby. The cries of the baby arouse the maternal instinct of Kali who reverts to her benign form as Parvati. Lord Shiva, in this baby form is Kshethra Balaka (who becomes Rudra Savarni Manu in future).[50]

In Skanda Purana, Parvati assumes the form of a warrior-goddess and defeats a demon called Durg who assumes the form of a buffalo. In this aspect, she is known by the name Durga.[51] Although Parvati is considered another aspect of Shakti, just like Kali, Durga, Kamakshi, Meenakshi, Gauri and many others in modern-day Hinduism, many of these "forms" or aspects originated from regional legends and traditions, and the distinctions from Parvati are pertinent.[52]

According to Shaktism and Shaivism traditions, and also in Devi Bhagavata Purana, Parvati is the lineal progenitor of all other goddesses. She is worshiped as one with many forms and names. Her form or incarnation depends on her mood.

- Akhilandeshwari, found in coastal regions of India, is the goddess associated with water.[53]

- Uma devi/Tripura Parvati, a goddess who looks like Bhuvaneshvari. She assumed to destroy ego of Devas. Her Dhyana Shloka is mentioned in 13th chapter of Devi Mahatmya.[54]

- Shiva himself, Shiva and Parvati are sometimes thought of as being identical and the same as a higher "God" who is both male and female.[55]

Legends

[edit]

The Puranas tell the tale of Sati's marriage to Shiva against her father Daksha's wishes. The conflict between Daksha and Shiva gets to a point where Daksha does not invite Shiva to his yagna (fire-sacrifice). Daksha insults Shiva when Sati comes on her own. She immolates herself at the ceremony. This shocks Shiva, who is so grief-stricken that he loses interest in worldly affairs, retires, and isolates himself in the mountains, in meditation and austerity. Sati is then reborn as Parvati, the daughter of Himavat and Mainavati,[8] and is named Parvati, or "she from the mountains", after her father Himavant who is also called king Parvat.[56][57][58]

According to different versions of her chronicles, the maiden Parvati resolves to marry Shiva. Her parents learn of her desire, discourage her, but she pursues what she wants. Indra sends the god Kama – the Hindu god of desire, erotic love, attraction, and affection, to awake Shiva from meditation. Kama reaches Shiva and shoots an arrow of desire.[59] Shiva opens his third eye in his forehead and burns the cupid Kama to ashes. Parvati does not lose her hope or her resolve to win over Shiva. She begins to live in mountains like Shiva, engage in the same activities as Shiva, one of asceticism, yogin and tapas. This draws the attention of Shiva and awakens his interest. He meets her in disguised form, tries to discourage her, telling her Shiva's weaknesses and personality problems.[59] Parvati refuses to listen and insists on her resolve. Shiva finally accepts her and they get married.[59][60] Shiva dedicates the following hymn in Parvati's honor,

I am the sea and you the wave,

You are Prakṛti, and I Purusha.

– Translated by Stella Kramrisch[61]

After the marriage, Parvati moves to Mount Kailash, the residence of Shiva. To them are born Kartikeya (also known as Skanda and Murugan) – the leader of celestial armies, and Ganesha – the god of wisdom that prevents problems and removes obstacles.[11][62]

There are many alternate Hindu legends about the birth of Parvati and how she married Shiva. In the Harivamsa, for example, Parvati has two younger sisters called Ekaparna and Ekapatala.[25] According to Devi Bhagavata Purana and Shiva Purana mount Himalaya and his wife Mena appease goddess Adi Parashakti. Pleased, Adi Parashakti herself is born as their daughter Parvati. Each major story about Parvati's birth and marriage to Shiva has regional variations, suggesting creative local adaptations. The stories go through many ups and downs until Parvati and Shiva are finally married.[63]

Kalidasa's epic Kumarasambhavam ("Birth of Kumara") describes the story of the maiden Parvati who has made up her mind to marry Shiva and get him out of his recluse, intellectual, austere world of aloofness. Her devotions aimed at gaining the favor of Shiva, the subsequent annihilation of Kamadeva, the consequent fall of the universe into barren lifelessness, regeneration of life, the subsequent marriage of Parvati and Shiva, the birth of Kartikeya, and the eventual resurrection of Kamadeva after Parvati intercedes for him to Shiva.

Parvati's legends are intrinsically related to Shiva. In the goddess-oriented Shakta texts, that she is said to transcend even Shiva, and is identified as the Supreme Being.[22] Just as Shiva is at once the presiding deity of destruction and regeneration, the couple jointly symbolize at once both the power of renunciation and asceticism and the blessings of marital felicity.

Parvati thus symbolizes many different virtues esteemed by Hindu tradition: fertility, marital felicity, devotion to the spouse, asceticism, and power. Parvati represents the householder ideal in the perennial tension in Hinduism in the household ideal and the ascetic ideal, the latter represented by Shiva.[49] Renunciation and asceticism is highly valued in Hinduism, as is the householder's life – both feature as Ashramas of ethical and proper life. Shiva is portrayed in Hindu legends as the ideal ascetic withdrawn in his personal pursuit in the mountains with no interest in social life, while Parvati is portrayed as the ideal householder keen on nurturing worldly life and society.[59] Numerous chapters, stories, and legends revolve around their mutual devotion as well as disagreements, their debates on Hindu philosophy as well as the proper life.

Parvati tames Shiva with her presence. When Shiva does his violent, destructive Tandava dance, Parvati is described as calming him or complementing his violence by slow, creative steps of her own Lasya dance. In many myths, Parvati is not as much his complement as his rival, tricking, seducing, or luring him away from his ascetic practices.[64]

Three images are central to the mythology, iconography, and philosophy of Parvati: the image of Shiva-Shakti, the image of Shiva as Ardhanarishvara (the Lord who is half-woman), and the image of the linga and the yoni. These images that combine the masculine and feminine energies, Shiva and Parvati,[65] yield a vision of reconciliation, interdependence, and harmony between the way of the ascetic and that of a householder.[66]

The couple is often depicted in the Puranas as engaged in "dalliance" or seated on Mount Kailash debating concepts in Hindu theology. They are also depicted as quarreling.[67] In stories of the birth of Kartikeya, the couple is described as love-making; generating the seed of Shiva. Parvati's union with Shiva symbolizes the union of a male and female in "ecstasy and sexual bliss".[68] In art, Parvati is depicted seated on Shiva's knee or standing beside him (together the couple is referred to as Uma-Maheshvara or Hara-Gauri) or as Annapurna (the goddess of grain) giving alms to Shiva.[69]

Shaiva's approaches tend to look upon Parvati as the Shiva's submissive and obedient wife. However, Shaktas focus on Parvati's equality or even superiority to her consort. The story of the birth of the ten Mahavidyas (Wisdom Goddesses) of Shakta Tantrism. This event occurs while Shiva is living with Parvati in her father's house. Following an argument, he attempts to walk out on her. Her rage at Shiva's attempt to walk out manifests in the form of ten terrifying goddesses who block Shiva's every exit.

David Kinsley states,

The fact that [Parvati] can physically restrain Shiva dramatically makes the point that she is superior in power. The theme of the superiority of the goddess over male deities is common in Shakta texts, [and] so the story is stressing a central Shakta theological principle. ... The fact that Shiva and Parvati are living in her father's house in itself makes this point, as it is traditional in many parts of India for the wife to leave her father's home upon marriage and become a part of her husband's lineage and live in his home among his relatives. That Shiva dwells in Parvati's house thus implies Her priority in their relationship. Her priority is also demonstrated in her ability, through the Mahavidyas, to thwart Shiva's will and assert her own.[70]

Ardhanarisvara

[edit]Parvati is portrayed as the ideal wife, mother, and householder in Indian legends.[72] In Indian art, this vision of the ideal couple is derived from Shiva and Parvati as being half of the other, represented as Ardhanarisvara.[73] This concept is represented as an androgynous image that is half man and half woman, Siva and Parvati, respectively.[71][74]

Ideal wife, mother and more

[edit]In Hindu Epic the Mahabharata, she as Umā suggests that the duties of wife and mother are as follows – being of a good disposition, endued with sweet speech, sweet conduct, and sweet features. Her husband is her friend, refuge, and god.[75] She finds happiness in her husband's and her children's physical and emotional nourishment and development. Their happiness is her happiness. She is cheerful even when her husband or children are angry; she is with them in adversity or sickness.[75] She takes an interest in worldly affairs beyond her husband and family. She is cheerful and humble before family, friends, and relatives; she helps them if she can. She welcomes guests, feeds them, and encourages a righteous social life. Parvati declares her family life and home are heaven in Book 13 of the Mahabharata.[75]

Rita Gross states,[41] that the view of Parvati only as ideal wife and mother is incomplete symbolism of the power of the feminine in the mythology of India. Parvati, along with other goddesses, is involved with a broad range of culturally valued goals and activities.[41] Her connection with motherhood and female sexuality does not confine the feminine or exhaust their significance and activities in Hindu literature. She is balanced by Durga, who is strong and capable without compromising her femaleness. She manifests in every activity, from water to mountains, from arts to inspiring warriors, from agriculture to dance. Parvati's numerous aspects state Gross,[41] reflects the Hindu belief that the feminine has a universal range of activities, and her gender is not a limiting condition.

Parvati is seen as the mother of two widely worshipped deities — Ganesha and Kartikeya.

Ganesha

[edit]Hindu literature, including the Matsya Purana, Shiva Purana, and Skanda Purana, dedicates many stories to Parvati and Shiva and their children.[76] For example, one about Ganesha is:

- Once, while Parvati wanted to take a bath, there were no attendants around to guard her and stop anyone from accidentally entering the house. Hence she created an image of a boy out of turmeric paste which she prepared to cleanse her body and infused life into it, and thus Ganesha was born. Parvati ordered Ganesha not to allow anyone to enter the house, and Ganesha obediently followed his mother's orders. After a while Shiva returned and tried to enter the house, Ganesha stopped him. Shiva was infuriated, lost his temper, and severed the boy's head with his trident. When Parvati came out and saw her son's lifeless body, she was very angry. She demanded that Shiva restore Ganesha's life at once. Shiva did so by attaching an elephant's head to Ganesha's body, thus giving rise to the elephant-headed deity.[77][78]

In culture

[edit]Festivals

[edit]Teej is a significant festival for Hindu women, particularly in the northern and western states of India. Parvati is the primary deity of the festival, and it ritually celebrates married life and family ties.[79] It also celebrates the monsoon. The festival is marked with swings hung from trees, girls playing on these swings typically in a green dress (seasonal color of crop planting season), while singing regional songs.[80] Historically, unmarried maidens prayed to Parvati for a good mate, while married women prayed for the well-being of their husbands and visited their relatives. In Nepal, Teej is a three-day festival marked with visits to Shiva-Parvati temples and offerings to linga.[79] Teej is celebrated as Teeyan in Punjab.[81]

The Gowri Habba, or Gauri Festival, is celebrated on the seventh, eighth, and ninth of Bhadrapada (Shukla paksha). Parvati is worshipped as the goddess of harvest and protector of women. Her festival, chiefly observed by women, is closely associated with the festival of her son Ganesha (Ganesh Chaturthi). The festival is popular in Maharashtra and Karnataka.[82]

In Rajasthan, the worship of Gauri happens during the Gangaur festival. The festival starts on the first day of Chaitra the day after Holi and continues for 18 days. Images of Issar and Gauri are made from Clay for the festival.

Another popular festival in reverence of Parvati is Navratri, in which all her manifestations are worshiped over nine days. Popular in eastern India, particularly in Bengal, Odisha, Jharkhand and Assam, as well as several other parts of India such as Gujarat, with her nine forms, that is, Shailaputri, Brahmacharini, Chandraghanta, Kushmanda, Skandamata, Katyayini, Kaalratri, Mahagauri, and Siddhidatri.[83]

Another festival Gauri Tritiya is celebrated from Chaitra Shukla third to Vaishakha Shukla third. This festival is popular in Maharashtra and Karnataka, less observed in North India, and unknown in Bengal. The unwidowed women of the household erect a series of platforms in a pyramidal shape with the image of the goddess at the top and a collection of ornaments, images of other Hindu deities, pictures, shells, etc. below. Neighbors are invited and presented with turmeric, fruits, flowers, etc. as gifts. At night, prayers are held with singing and dancing. In south Indian states such as Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh, the Kethara Gauri Vritham festival is celebrated on the new moon day of Diwali and married women fast for the day, prepare sweets and worship Parvati for the well-being of the family.[84]

Thiruvathira is a festival observed in Kerala and Tamil Nadu. It is believed that on this day, Parvati met Shiva after her long penance and Shiva took her as his wife.[85] On this day Hindu women perform the Thiruvathirakali accompanied by Thiruvathira paattu (folk songs about Parvati and her longing and penance for Lord Shiva's affection).[86]

Arts

[edit]

From sculpture to dance, many Indian arts explore and express the stories of Parvati and Shiva as themes. For example, Daksha Yagam of Kathakali, a form of dance-drama choreography, adapts the romantic episodes of Parvati and Shiva.[87]

The Gauri-Shankar bead is a part of religious adornment rooted in the belief of Parvati and Shiva as the ideal equal complementing halves of the other. Gauri-Shankar is a particular rudraksha (bead) formed naturally from the seed of a tree found in India. Two seeds of this tree sometimes naturally grow as fused and are considered symbolic of Parvati and Shiva. These seeds are strung into garlands and worn, or used in malas (rosaries) for meditation in Saivism.[88]

Numismatics

[edit]Ancient coins from Bactria (Central Asia) of Kushan Empire era, and those of king Harsha (North India) feature Uma. These were issued sometime between the 3rd- and 7th-century AD. In Bactria, Uma is spelled Ommo, and she appears on coins holding a flower.[89][90] On her coin is also shown Shiva, who is sometimes shown in the ithyphallic state holding a trident and standing near Nandi (his vahana). On coins issued by king Harsha, Parvati and Shiva are seated on a bull and the reverse of the coin has Brahmi script.[91]

Major temples

[edit]

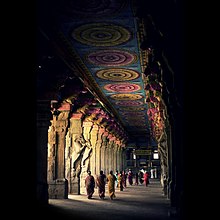

Parvati is often present with Shiva in Saivite Hindu temples all over South Asia and Southeast Asia.

Some locations (Pithas or Shaktipeeths) are considered special because of their historical importance and legends about their origins in the ancient texts of Hinduism.[92][93]

List of temples

[edit]Each major Parvati-Shiva temple is a pilgrimage site that has an ancient legend associated with it, which is typically a part of a larger story that links these Hindu temples across South Asia with each other. Some temples where Parvati can be found include:

- in Jammu and Kashmir: Udhampur District, Jammu Mantalai Temple and Gauri Kund

- In Karnataka: Chamundeswari Temple Mysore

- In Odisha : Parvati in the form of Annapurna, as the consort of Lingaraj inside Lingaraj temple complex, Bhubaneswar

- in Kerala: Annapurneshwari Temple, Cherukunnu, Attukal Bhagavathy Temple, Chakkulathukavu Temple, Chengannur Mahadeva Temple, Oorpazhachi Kavu, Irumkulangara Durga Devi Temple, and Kadampuzha Devi Temple

- in Maharashtra: Tulja Bhavani Temple

- in Meghalaya: Nartiang Durga Temple

- in Tamil Nadu: Meenakshi Amman Temple, Kamakshi Amman Temple, Sri Siva Durga Temple, Bannari Amman Temple, Samayapuram Mariamman Temple, Vekkali Amman Temple, Mutharamman Temple, Kulasekharapatnam, Tiruverkadu Devi Karumariamman Temple, Nellaiappar Temple, Kapaleeshwarar Temple, Masani Ammam temple, Gomathi Amman, Punnainallur Mariamman

- in Tripura: Tripura Sundari Temple

- in Uttar Pradesh: Vishalakshi Temple, Vishalakshi Gauri Temple and Annapurna Devi Temple

Outside India

[edit]Sculpture and iconography of Parvati, in one of her many manifestations, have been found in temples and literature of Southeast Asia. For example, early Saivite inscriptions of the Khmer in Cambodia, dated as early as the fifth century AD, mention Parvati (Uma) and Siva.[94] Many ancient and medieval era Cambodian temples, rock arts and river bed carvings such as the Kbal Spean are dedicated to Parvati and Shiva.[95][96]

Boisselier has identified Uma in a Champa era temple in Vietnam.[97]

Dozens of ancient temples dedicated to Parvati as Uma, with Siva, have been found in the islands of Indonesia and Malaysia. Her manifestation as Durga has also been found in southeast Asia.[98] Many of the temples in Java dedicated to Siva-Parvati are from the second half of 1st millennium AD, and some from later centuries.[99] Durga icons and worship have been dated to be from the 10th- to 13th-century.[100]

Derived from Parvati's form as Mahakali, her nipponized form is Daikokutennyo (大黒天女).

In Nakhorn Si Thammarat province of Thailand, excavations at Dev Sathan have yielded a Hindu Temple dedicated to Vishnu (Na Pra Narai), a lingam in the yoni, a Shiva temple (San Pra Isuan). The sculpture of Parvati found at this excavation site reflects the South Indian style.[103][104]

- Bali, Indonesia

Parvati, locally spelled as Parwati, is a principal goddess in modern-day Hinduism of Bali. She is more often called Uma, and sometimes referred to as Giriputri (daughter of the mountains).[105] She is the goddess of mountain Gunung Agung.[106] Like Hinduism of India, Uma has many manifestations in Bali, Indonesia. She is married to deity Siwa. Uma or Parwati is considered as the mother goddess that nurtures, nourishes, grants fertility to crop and all life. As Dewi Danu, she presides over waters, lake Batur and Gunung Batur, a major volcano in Bali. Her ferocious form in Bali is Dewi Durga.[107] As Rangda, she is wrathful and presides over cemeteries.[106] As Ibu Pertiwi, Parwati of Balinese Hinduism is the goddess of earth.[106] The legends about various manifestations of Parwati, and how she changes from one form to another, are in Balinese literature, such as the palm-leaf (lontar) manuscript Andabhuana.[108]

Related goddesses

[edit]Tara found in some sects of Buddhism, particularly Tibetan and Nepalese, is related to Parvati.[109][110] Tara too appears in many manifestations. In tantric sects of Buddhism, as well as Hinduism, intricate symmetrical art forms of yantra or mandala are dedicated to different aspects of Tara and Parvati.[111][112]

Parvati is closely related in symbolism and powers to Cybele of Greek and Roman mythology and as Vesta the guardian goddess of children.[11][113] In her manifestation as Durga, Parvati parallels Mater Montana.[11] She is the equivalent of the Magna Mater (Universal Mother).[20] As Kali and punisher of all evil, she corresponds to Proserpine and Diana Taurica.[114]

As Bhawani and goddess of fertility and birthing, she is the symbolic equivalent of Ephesian Diana.[114] In Crete, Rhea is the mythological figure, goddess of the mountains, paralleling Parvati; while in some mythologies from islands of Greece, the terrifying goddess mirroring Parvati is Diktynna (also called Britomartis).[115] At Ephesus, Cybele is shown with lions, just like the iconography of Parvati is sometimes shown with a lion.[115]

Carl Jung, in Mysterium Coniunctionis, states that aspects of Parvati belong to the same category of goddesses like Artemis, Isis and Mary.[116][117] Edmund Leach equates Parvati in her relationship with Shiva, with that of the Greek goddess Aphrodite – a symbol of sexual love.[118]

References

[edit]- ^ James D. Holt (2014). Religious Education in the Secondary School: An Introduction to Teaching, Learning and the World Religions. Routledge. p. 180. ISBN 978-1-317-69874-6.

- ^ David Kinsley (19 July 1988). Hindu Goddesses: Visions of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Tradition. University of California Press. pp. 49–50. ISBN 978-0-520-90883-3.

- ^ Cush, Robinson & York 2008, p. 78.

- ^ Williams 1981, p. 62.

- ^ Siva: The Erotic Ascetic. Oxford University Press. 28 May 1981. ISBN 978-0-19-972793-3. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ^ a b Wilkins 2001, p. 295.

- ^ C. Mackenzie Brown (1990). The Triumph of the Goddess: The Canonical Models and Theological Visions of the Devi-Bhagavata Purana. SUNY Press. ISBN 9780791403648. Archived from the original on 26 January 2024. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- ^ a b Sita Narasimhan (2006). Śaivism Under the Imperial Cōl̲as as Revealed Through Their Monuments. Sharada Publishing House. p. 100. ISBN 9788188934324.

- ^ Frithjof Schuon (2003), Roots of the Human Condition, ISBN 978-0941532372, pp 32

- ^ a b c d e f Kinsley, David (1998). Hindu Goddesses: Visions of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Tradition. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 978-81-208-0394-7.

- ^ a b c d e Edward Balfour, Parvati, p. 153, at Google Books, The Encyclopaedia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia, pp 153

- ^ a b H.V. Dehejia, Parvati: Goddess of Love, Mapin, ISBN 978-8185822594, pp 11

- ^ Edward Washburn Hopkins, Epic Mythology, p. 224, at Google Books, pp. 224–226

- ^ Ananda Coomaraswamy, Saiva Sculptures, Museum of Fine Arts Bulletin, Vol. 20, No. 118 (Apr. 1922), pp 17

- ^ Stella Kramrisch (1975), The Indian Great Goddess, History of Religions, Vol. 14, No. 4, pp. 261

- ^ H.V. Dehejia, Parvati: Goddess of Love, Mapin, ISBN 978-8185822594

- ^ James Hendershot, Penance, Trafford, ISBN 978-1490716749, pp 78

- ^ Hariani Santiko, The Goddess Durgā (warrior form of Parvati)in the East-Javanese Period, Asian Folklore Studies, Vol. 56, No. 2 (1997), pp. 209–226

- ^ Ananda Coomaraswamy, Saiva Sculptures, Museum of Fine Arts Bulletin, Vol. 20, No. 118 (Apr. 1922), pp 15–24

- ^ a b Alain Daniélou (1992), Gods of Love and Ecstasy: The Traditions of Shiva and Dionysus, ISBN 978-0892813742, pp 77–80

- ^ a b c John Muir, Original Sanskrit Texts on the Origin and History of the People of India, p. 422, at Google Books, pp 422–436

- ^ a b Kinsley 1988, p. 41.

- ^ Keller and Ruether (2006), Encyclopedia of Women and Religion in North America, Indiana University Press, ISBN 978-0253346858, pp 663

- ^ Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam (ed.). India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 68.

- ^ a b Wilkins 2001, pp. 240–1.

- ^ Kinsley 1988, pp. 142–143.

- ^ Edward Balfour, Parvati, p. 381, at Google Books, The Encyclopedia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia, pp 381

- ^ Ernest Payne (1997), The Saktas: An Introductory and Comparative Study, Dover, ISBN 978-0486298665, pp 7–8, 13–14

- ^ Dani, Ahmad Hasan; Harmatta, János (1999). History of Civilizations of Central Asia. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 326. ISBN 978-81-208-1408-0.

- ^ "Ommo-Oesho coin of Huvishka British Museum". The British Museum.

- ^ a b Kinsley 1988, p. 36.

- ^ Kena Upanisad, III.1–-IV.3, cited in Müller and in Sarma, pp. xxix-xxx.

- ^ Kinsley 1988, pp. 36–41.

- ^ Edward Washburn Hopkins, Epic Mythology, p. 224, at Google Books, pp. 224–225

- ^ Weber in Wilkins 2001, p. 239.

- ^ Tate 2006, p. 176.

- ^ Wilkins 2001, p. 247.

- ^ Harry Judge (1993), Devi, Oxford Illustrated Encyclopedia, Oxford University Press, pp 10

- ^ a b Suresh Chandra (1998), Encyclopedia of Hindu Gods and Goddesses, ISBN 978-8176250399, pp 245–246

- ^ James Lochtefeld (2005), "Yoni" in The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 2: N–Z, pp. 784, Rosen Publishing, ISBN 0-8239-2287-1

- ^ a b c d e Rita M. Gross (1978), Hindu Female Deities as a Resource for the Contemporary Rediscovery of the Goddess, Journal of the American Academy of Religion, Vol. 46, No. 3 (Sep. 1978), pp. 269–291

- ^ Caroll and Caroll (2013), Mudras of India, ISBN 978-1848191099, pp 34, 266

- ^ Caroll and Caroll (2013), Mudras of India, ISBN 978-1848191099, pp 184

- ^ Caroll and Caroll (2013), Mudras of India, ISBN 978-1848191099, pp 303, 48

- ^ The Shaktas: an introductory comparative study Payne A.E. 1933 pp. 7, 83

- ^ Devdutt Pattanaik (2014), Pashu: Animal Tales from Hindu Mythology, Penguin, ISBN 978-0143332473, pp 40–42

- ^ Sally Kempton (2013), Awakening Shakti: The Transformative Power of the Goddesses of Yoga, ISBN 978-1604078916, pp 165–167

- ^ a b Ellen Goldberg (2002), The Lord Who Is Half Woman: Ardhanarisvara in Indian and Feminist Perspective, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791453254, pp. 133–153

- ^ a b Kinsley 1988, p. 46.

- ^ Kennedy 1831, p. 338.

- ^ Kinsley 1988, p. 96.

- ^ Kinsley 1988, p. 4.

- ^ Subhash C Biswas, India the Land of Gods, ISBN 978-1482836554, pp 331–332

- ^ www.wisdomlib.org (4 November 2018). "The manifestation of Umā [Chapter 49]". www.wisdomlib.org. Retrieved 26 November 2022.

- ^ MacGregor, Neil (2011). A History of the World in 100 Objects (First American ed.). New York: Viking Press. p. 440. ISBN 978-0-670-02270-0.

- ^ Kinsley 1988, p. 42.

- ^ Wilkins 2001, pp. 300–301.

- ^ In the Ramayana, the river goddess Ganga is the first daughter and the elder sister of Parvati (Wilkins 2001, p. 294).

- ^ a b c d James Lochtefeld (2005), "Parvati" in The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 2: N–Z, pp. 503–505, Rosen Publishing, ISBN 0-8239-2287-1

- ^ Kinsley 1988, p. 43.

- ^ Stella Kramrisch (1975), The Indian Great Goddess, History of Religions, Vol. 14, No. 4, pp. 235–265

- ^ Ganesa: Unravelling an Enigma By Yuvraj Krishan p.6

- ^ Alain Daniélou (1992), Gods of Love and Ecstasy: The Traditions of Shiva and Dionysus, ISBN 978-0892813742, pp 82–87

- ^ Kinsley 1988, pp. 46–48.

- ^ Manish, Kumar. "Lord Shiva and Parvati Images". SocialStatusDP.com.

- ^ Kinsley 1988, p. 49.

- ^ Kennedy 1831, p. 334.

- ^ Tate 2006, p. 383.

- ^ Coleman 2021, p. 65.

- ^ Kinsley 1988, p. 26.

- ^ a b MB Wangu (2003), Images of Indian Goddesses: Myths, Meanings, and Models, ISBN 978-8170174165, Chapter 4 and pp 86–89

- ^ Wojciech Maria Zalewski (2012), The Crucible of Religion: Culture, Civilization, and Affirmation of Life, ISBN 978-1610978286, pp 136

- ^ Betty Seid (2004), The Lord Who Is Half Woman (Ardhanarishvara), Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies, Vol. 30, No. 1, Notable Acquisitions at The Art Institute of Chicago, pp. 48–49

- ^ A Pande (2004), Ardhanarishvara, the Androgyne: Probing the Gender Within, ISBN 9788129104649, pp 20–27

- ^ a b c Anucasana Parva The Mahabharata, pp 670–672

- ^ Kennedy 1831, p. 353-4.

- ^ Paul Courtright (1978), Ganesa: Lord of Obstacles, Lord of Beginnings, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195057423

- ^ Robert Brown (1991), Ganesh: Studies of an Asian God, SUNY Press, ISBN 978-0791406564

- ^ a b Constance Jones (2011), Religious Celebrations: An Encyclopedia of Holidays (Editor – J. Gordon Melton), ISBN 978-1598842050, pp. 847–848

- ^ Devotion, mirth mark ‘Hariyali Teej’ The Hindu (10 August 2013)

- ^ Gurnam Singh Sidhu Brard (2007), East of Indus: My Memories of Old Punjab, ISBN 978-8170103608, pp 325

- ^ The Hindu Religious Year By Muriel Marion Underhill p.50 Published 1991 Asian Educational Services ISBN 81-206-0523-3

- ^ S Gupta (2002), Festivals of India, ISBN 978-8124108697, pp 68–71

- ^ The Hindu Religious Year By Muriel Marion Underhill p.100

- ^ "Tubers are the veggies of choice to celebrate Thiruvathira". Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- ^ "Thiruvathira – Kerala's own version of Karva Chauth". Manorama. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- ^ Ragini Devi (2002), Dance Dialects of India, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120806740, pp. 201–202

- ^ James Lochtefeld (2005), "Gauri-Shankar" in The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 1: A-M, pp. 244, Rosen Publishing, ISBN 0-8239-2287-1

- ^ John M. Rosenfield (1967), The Dynastic Arts of the Kushans, University of California Press, Reprinted in 1993 as ISBN 978-8121505796, pp. 94–95

- ^ AH Dani et al., History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Vol. 2, Editors: Harmatta et al., UNESCO, ISBN 978-9231028465, pp 326–327

- ^ Arthur L. Friedberg and Ira S. Friedberg (2009), Gold Coins of the World: From Ancient Times to the Present, ISBN 978-0871843081, pp 462

- ^ Devangana Desai, Khajuraho, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195653915, pp 42–51, 80–82

- ^ Steven Leuthold (2011), Cross-Cultural Issues in Art: Frames for Understanding, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415578004, pp 142–143

- ^ Sanderson, Alexis (2004), "The Saiva Religion among the Khmers, Part I.", Bulletin de Ecole frangaise d'Etreme-Orient, 90–91, pp 349–462

- ^ Michael Tawa (2001), At Kbal Spean, Architectural Theory Review, Volume 6, Issue 1, pp 134–137

- ^ Helen Jessup (2008), The rock shelter of Peuong Kumnu and Visnu Images on Phnom Kulen, Vol. 2, National University of Singapore Press, ISBN 978-9971694050, pp. 184–192

- ^ Jean Boisselier (2002), "The Art of Champa", in Emmanuel Guillon (Editor) – Hindu-Buddhist Art in Vietnam: Treasures from Champa, Trumbull, p. 39

- ^ Hariani Santiko (1997), The Goddess Durgā in the East-Javanese Period, Asian Folklore Studies, Vol. 56, No. 2 (1997), pp. 209–226

- ^ R Ghose (1966), Saivism in Indonesia during the Hindu-Javanese period Archived 26 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Thesis, Department of History, University of Hong Kong

- ^ Peter Levenda (2011), Tantric Temples: Eros and Magic in Java, ISBN 978-0892541690, pp 274

- ^ Joe Cribb; Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles (1999). Magic Coins of Java, Bali and the Malay Peninsula: Thirteenth to Twentieth Centuries. British Museum Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-7141-0881-0.

- ^ Yves Bonnefoy (1993). Asian Mythologies. University of Chicago Press. pp. 178–179. ISBN 978-0-226-06456-7.

- ^ R. Agarwal (2008), "Cultural Collusion: South Asia and the construction of the Modern Thai Identities", Mahidol University International College (Thailand)

- ^ Gutman, P. (2008), Siva in Burma, in Selected Papers from the 10th International Conference of the European Association of Southeast Asian Archaeologists: the British Museum, London, 14th–17th September 2004: Interpreting Southeast Asia's past, monument, image, and text (Vol. 10, p. 135), National University of Singapore Press

- ^ Reinhold Rost, Miscellaneous Papers Relating to Indo-China and the Indian Archipelago, p. 105, at Google Books, Volume 2, pp 105

- ^ a b c Jones and Ryan, Encyclopedia of Hinduism, ISBN 978-0816054589, pp 67–68

- ^ Michele Stephen (2005), Desire Divine & Demonic: Balinese Mysticism in the Paintings, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0824828592, pp 119–120, 90

- ^ J. Stephen Lansing (2012), Perfect Order: Recognizing Complexity in Bali, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0691156262, pp 138–139

- ^ David Leeming (2005), The Oxford Companion to World Mythology, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195156690, pp 374–375

- ^ Monier Williams, Buddhism: In Its Connection with Brāhmanism and Hindūism, p. 216, at Google Books, pp 200–219

- ^ David Frawley (1994), Tantric Yoga and the Wisdom Goddesses: Spiritual Secrets of Ayurveda, ISBN 978-1878423177, pp 57–85

- ^ Rebeca French, The Golden Yoke: The Legal Cosmology of Buddhist Tibet, ISBN 978-1559391719, pp 185–188

- ^ George Stanley Faber, The Origin of Pagan Idolatry, p. 488, at Google Books, pp 260–261, 404–419, 488

- ^ a b Maria Callcott, Letters on India, p. 345, at Google Books, pp 345–346

- ^ a b Alain Daniélou (1992), Gods of Love and Ecstasy: The Traditions of Shiva and Dionysus, ISBN 978-0892813742, pp 79–80

- ^ Joel Ryce-Menuhin (1994), Jung and the Monotheisms, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415104142, pp 64

- ^ Ann Casement (2001), Carl Gustav Jung, SAGE Publications, ISBN 978-0761962373, pp 56

- ^ Edmund Ronald Leach, The Essential Edmund Leach: Culture and human nature, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0300085082, pp 85

Works cited

[edit]- Coleman, Charles N. (2021) [1832]. Mythology of the Hindus. Legare Street Press. ISBN 978-1014497710.

- Cush, Denise; Robinson, Catherine A.; York, Michael (2008). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Routledge. ISBN 978-0700712670. Archived from the original on 21 April 2023. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- Kennedy, Vans (1831). Researches Into the Nature and Affinity of Ancient and Hindu Mythology. Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green – via Internet Archive.

- Kinsley, David R. (1988). Hindu Goddesses: Visions of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Tradition. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-90883-3.

- Tate, Karen (2006). Sacred Places of Goddess: 108 Destinations. Consortium of Collective Consciousness. ISBN 978-1888729115.

- Wilkins, William J. (2001) [1882]. "Uma – Parvati". Hindu Mythology, Vedic and Puranic. Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 1-4021-9308-4 – via Internet Archive.

- Williams, Joanna Gottfried (1981). Kalādarśana: American Studies in the Art of India. Brill Academic. ISBN 9004064982. Archived from the original on 16 January 2024. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

Further reading

[edit]- Srivastava, A. L. (2004). Umā-Maheśvara: An Iconographic Study of the Divine Couple. Sukarkshetra Shodh Sansthana.