Ontario: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

m Reverted edits by 174.117.209.119 to last revision by Tide rolls (HG) |

||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

| PercentWater = 14.8 |

| PercentWater = 14.8 |

||

| PopulationRank = 1st |

| PopulationRank = 1st |

||

| Population = 13, |

| Population = 13,150,000 (est.)<ref>{{cite web | author= Government of Ontario|publisher= |title= Ontario Budget 2009: Chapter II: Ontario’s Economic Outlook and Fiscal Plan 2009-26-03 |accessdate=2009-08-21 |url=http://www.fin.gov.on.ca/english/budget/ontariobudgets/2009/chpt2.html}}</ref> |

||

| PopulationYear = 2009 |

| PopulationYear = 2009 |

||

| DensityRank = 3rd |

| DensityRank = 3rd |

||

Revision as of 03:09, 17 February 2010

Ontario | |

|---|---|

| |

| Country | Canada |

| Confederation | July 1, 1867 (1st) |

| Government | |

| • Lieutenant Governor | David Onley |

| • Premier | Dalton McGuinty |

| Federal representation | Parliament of Canada |

| House seats | 107 of 338 (31.7%) |

| Senate seats | 24 of 105 (22.9%) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 14,223,942 |

| GDP | |

| • Rank | 1st |

| • Total (2008) | C$597.2 billion[2] |

| • Per capita | C$43,847 (6th) |

| Canadian postal abbr. | ON |

| Postal code prefix | |

| Rankings include all provinces and territories | |

Ontario (Template:Pron-en) is a province located in east-central Canada,[3][4] the largest by population[5] and second largest, after Quebec, in total area.[1] (Nunavut and the Northwest Territories are larger but are not provinces.)

Ontario is bordered by the Canadian provinces of Manitoba to the west and Quebec to the east, and 5 U.S. states (from west to east): Minnesota, Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania (the latter two across Lake Erie) and New York to the south and east. Most of Ontario's 2,700 km (1,677 mi) long border with the United States runs along water, in the west the Lake of the Woods and eastward of there either on lakes or rivers within the Great Lakes drainage system: Superior, St. Marys River, Huron, St. Clair River, Lake St. Clair (sometimes referred to as the sixth Great Lake), Erie, Ontario and then runs along the St. Lawrence River from near Kingston to near Cornwall. For analytical and geographical purposes Ontario is often broken into two regions, Northern Ontario and Southern Ontario. The great majority of population and arable land in Ontario is located in the south, which contrasts with its relatively small land area in comparison to the north.

The capital of Ontario is Toronto, Canada's most populous city and metropolitan area.[6] Ottawa, the capital of Canada, is located in Ontario as well. The Ontario Government projected a population of 13,150,000 people residing in the province of Ontario as of July 2009.

The province takes its name from Lake Ontario, which is thought to be derived from Ontarí:io, a Huron (Wyandot) word meaning "great lake",[7] or possibly skanadario which means "beautiful water" in Iroquoian.[8] The province contains over 250,000 freshwater lakes.

Geography

The province consists of four main geographical regions:

- The thinly populated Canadian Shield in the northwestern and central portions which covers over half the land area in the province; though mostly infertile land, it is rich in minerals and studded with lakes and rivers. Northern Ontario is subdivided into two sub-regions: Northwestern Ontario and Northeastern Ontario.

- The virtually unpopulated Hudson Bay Lowlands in the extreme north and northeast, mainly swampy and sparsely forested.

- The temperate and therefore most populous region, the fertile Great Lakes-Saint Lawrence Valley in the south where agriculture and industry are concentrated. Southern Ontario is further sub-divided into four regions; Central Ontario (although not actually the province's geographic centre), Eastern Ontario, Golden Horseshoe and Southwestern Ontario (parts of which were formerly referred to as Western Ontario).

Despite the absence of any mountainous terrain in the province, there are large areas of uplands, particularly within the Canadian Shield which traverses the province from northwest to southeast and also above the Niagara Escarpment which crosses the south. The highest point is Ishpatina Ridge at 693 metres (2,274 ft) above sea level located in Temagami, Northeastern Ontario. In the south, elevations of over 500m (1640') are surpassed near Collingwood, above the Blue Mountains in the Dundalk Highlands and in hilltops near the Madawaska River in Renfrew County.

The Carolinian forest zone covers most of the southwestern section, its northern extent is part of the Greater Toronto Area at the western end of Lake Ontario. The most well-known geographic feature is Niagara Falls, part of the much more extensive Niagara Escarpment. The Saint Lawrence Seaway allows navigation to and from the Atlantic Ocean as far inland as Thunder Bay in Northwestern Ontario. Northern Ontario occupies roughly 87% of the surface area of the province; conversely Southern Ontario contains 94% of the population.

Point Pelee National Park is a peninsula in southwestern Ontario (near Windsor and Detroit, Michigan) that extends into Lake Erie and is the southernmost extent of Canada's mainland. Pelee Island and Middle Island in Lake Erie extend slightly farther. All are south of 42°N – slightly farther south than the northern border of California.

Climate and environment

Climate

Ontario has three main climatic regions. Parts of Southwestern Ontario have a moderate humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification Dfa), similar to that of the inland Mid-Atlantic States and the Great Lakes portion of the Midwestern United States. The region has warm, humid summers and cold winters. Annual precipitation ranges from 75–100 cm (30–39 in) and is well distributed throughout the year with a usual summer peak. Most of this region lies in the lee of the Great Lakes making for abundant snow in some areas.

Central and Eastern Ontario have a more severe humid continental climate (Köppen Dfb). This region has warm and sometimes hot summers with colder longer winters, with ample snowfall and roughly equal annual precipitation as the rest of Southern Ontario. Along the eastern shores of Lake Superior and Lake Huron, frequent heavy lake-effect snow squalls increase seasonal snowfall totals upwards of 3 m (120 in) in some places.

The northernmost parts of Ontario — primarily north of 50°N have a subarctic climate (Köppen Dfc) with long, severely cold winters and short, cool to warm summers with dramatic temperature changes possible in all seasons. With no major mountain ranges blocking sinking Arctic air masses, temperatures of −40 °C (−40 °F) are not uncommon, snowfall remains on the ground for sometimes over half the year. Precipitation is generally less than 70 cm (28 in).

Severe and non-severe thunderstorms peak in summer. London, situated in Southern (Southwestern) Ontario, has the most lightning strikes per year in Canada, averaging 34 days of thunderstorm activity per year. In a typical year, Ontario averages 15 confirmed tornado touchdowns, they are rarely destructive (the majority between F0 to F2 on the Fujita scale). Tropical depression remnants occasionally bring heavy rains and winds in the south, but are rarely deadly. A notable exception was Hurricane Hazel which struck Toronto, in October 1954. Winter storms can disrupt power supply and transportation, severe ice storms can also occur, especially in the east.

Environment

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2009) |

The Green Energy and Green Economy Act, 2009 (GEGEA), takes a two-pronged approach to creating a renewable-energy economy.

History

Territorial evolution

Land was not legally subdivided into administrative units until a treaty had been concluded with the native peoples ceding the land. In 1788, while part of the Province of Quebec (1763–1791), southern Ontario was divided into four districts: Hesse, Lunenburg, Mecklenburg, and Nassau.

In 1792, the four districts were renamed: Hesse became the Western District, Lunenburg became the Eastern District, Mecklenburg became the Midland District, and Nassau became the Home District. Counties were created within the districts.

By 1798, there were eight districts: Eastern, Home, Johnstown, London, Midland, Newcastle, Niagara, and Western.

By 1826, there were eleven districts: Bathurst, Eastern, Gore, Home, Johnstown, London, Midland, Newcastle, Niagara, Ottawa, and Western.

By 1838, there were twenty districts: Bathurst, Brock, Colbourne, Dalhousie, Eastern, Gore, Home, Huron, Johnstown, London, Midland, Newcastle, Niagara, Ottawa, Prince Edward, Simcoe, Talbot, Victoria, Wellington, and Western.

In 1849, the districts of southern Ontario were abolished by the Province of Canada, and county governments took over certain municipal responsibilities. The Province of Canada also began creating districts in sparsely populated Northern Ontario with the establishment of Algoma District and Nipissing District in 1858.

The borders of Ontario were provisionally expanded north and west. When the Province of Canada was formed, its borders were not entirely clear, and Ontario claimed to eventually reach all the way to the Rocky Mountains and Arctic Ocean. With Canada's acquisition of Rupert's Land, Ontario was interested in clearly defining its borders, especially since some of the new areas it was interested in were rapidly growing. After the federal government asked Ontario to pay for construction in the new disputed area, the province asked for an elaboration on its limits, and its boundary was moved north to the 51st parallel north.[9]

The northern and western boundaries of Ontario were in dispute after Confederation. Ontario's right to Northwestern Ontario was determined by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in 1884 and confirmed by the Canada (Ontario Boundary) Act, 1889 of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. By 1899, there were seven northern districts: Algoma, Manitoulin, Muskoka, Nipissing, Parry Sound, Rainy River, and Thunder Bay. Four more northern districts were created between 1907 and 1912: Cochrane, Kenora, Sudbury and Timiskaming.[10]

European contact

Before the arrival of the Europeans, the region was inhabited both by Algonquian (Ojibwa, Cree and Algonquin) in the northern/western portions and Iroquois and Wyandot (Huron) tribes more in the south/east.[11] During the 1600s, the Algonquians and Hurons fought a bitter war against the Iroquois.[12] The French explorer Étienne Brûlé explored part of the area in 1610-12.[13] The English explorer Henry Hudson sailed into Hudson Bay in 1611 and claimed the area for England, but Samuel de Champlain reached Lake Huron in 1615, and French missionaries began to establish posts along the Great Lakes. French settlement was hampered by their hostilities with the Iroquois, who allied themselves with the British.[14] From 1634 to 1640, Hurons were devastated by European infectious diseases, such as measles and smallpox, to which they had no immunity.[15]

The British established trading posts on Hudson Bay in the late 17th century and began a struggle for domination of Ontario. The 1763 Treaty of Paris ended the Seven Years' War by awarding nearly all of France's North American possessions (New France) to Britain.[16] The region was annexed to Quebec in 1774.[17] From 1783 to 1796, the Kingdom of Great Britain granted United Empire Loyalists leaving the United States following the American Revolution 200 acres (81 ha) of land and other items with which to rebuild their lives.[14] This measure substantially increased the population of Canada west of the St. Lawrence-Ottawa River confluence during this period, a fact recognized by the Constitutional Act of 1791, which split Quebec into the Canadas: Upper Canada southwest of the St. Lawrence-Ottawa River confluence, and Lower Canada east of it. John Graves Simcoe was appointed Upper Canada's first Lieutenant-Governor in 1793.[18]

Upper Canada

American troops in the War of 1812 invaded Upper Canada across the Niagara River and the Detroit River, but were defeated and pushed back by British regulars, Canadian fencibles and militias, and First Nations warriors. The Americans gained control of Lake Erie and Lake Ontario, however. During the Battle of York they occupied the Town of York (later named Toronto) in 1813. The Americans looted the town and burned the Parliament Buildings but were soon forced to leave.

After the War of 1812, relative stability allowed for increasing numbers of immigrants to arrive from Europe rather than from the United States. As was the case in the previous decades, this deliberate immigration shift was encouraged by the colonial leaders. Despite affordable and often free land, many arriving newcomers, mostly from Britain and Ireland found frontier life with the harsh climate difficult, and some of those with the means eventually returned home or went south. However, population growth far exceeded emigration in the decades that followed. It was a mostly agrarian-based society, but canal projects and a new network of plank roads spurred greater trade within the colony and with the United States, thereby improving previously damaged relations over time.

Meanwhile, Ontario's numerous waterways aided travel and transportation into the interior and supplied water power for development. As the population increased, so did the industries and transportation networks, which in turn led to further development. By the end of the century, Ontario vied with Quebec as the nation's leader in terms of growth in population, industry, arts and communications.[19]

Many in the colony however, began to chafe against the aristocratic Family Compact who governed while benefiting economically from the region's resources, and who did not allow elected bodies the power to effect change (much as the Château Clique ruled Lower Canada). This resentment spurred republican ideals and sowed the seeds for early Canadian nationalism. Accordingly, rebellion in favour of responsible government rose in both regions; Louis-Joseph Papineau led the Lower Canada Rebellion and William Lyon Mackenzie led the Upper Canada Rebellion.

Canada West

Although both rebellions were put down in short order, the British government sent Lord Durham to investigate the causes of the unrest. He recommended that self-government be granted and that Lower and Upper Canada be re-joined in an attempt to assimilate the French Canadians. Accordingly, the two colonies were merged into the Province of Canada by the Act of Union 1840, with the capital at Kingston, and Upper Canada becoming known as Canada West. Parliamentary self-government was granted in 1848. There were heavy waves of immigration in the 1840s, and the population of Canada West more than doubled by 1851 over the previous decade. As a result, for the first time the English-speaking population of Canada West surpassed the French-speaking population of Canada East, tilting the representative balance of power.

An economic boom in the 1850s coincided with railway expansion across the province, further increasing the economic strength of Central Canada. With the repeal of the Corn Laws and a reciprocity agreement in place with United States, various industries such as timber, mining, farming and alcohol distilling benefited tremendously.

A political stalemate between the French- and English-speaking legislators, as well as fear of aggression from the United States during and immediately after the American Civil War, led the political elite to hold a series of conferences in the 1860s to effect a broader federal union of all British North American colonies. The British North America Act took effect on July 1, 1867, establishing the Dominion of Canada, initially with four provinces: Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Quebec and Ontario. The Province of Canada was divided into Ontario and Quebec so that each linguistic group would have its own province. Both Quebec and Ontario were required by section 93 of the BNA Act to safeguard existing educational rights and privileges of Protestant and the Catholic minority. Thus, separate Catholic schools and school boards were permitted in Ontario. However, neither province had a constitutional requirement to protect its French- or English-speaking minority. Toronto was formally established as Ontario's provincial capital.

In 1868 the coat of arms and motto of Ontario are created. Curiously, the motto ("Ut incepit fidelis sic permanet") was added to Ontario´s coat of arms by Sir Henry William Stisted, The first Lieutenant-Governor of Ontario; who was a great friend of the Spanish General José of Bascarán and Federic, the 27th Lord of Olvera. In one of his visits to him, Sir Henry observed the mentioned motto in the coat of arms that was hung on the wall of the lounge of the house of the General Bascarán, and Sir Henry requested authorization from his friend to include in the coat of arms of Ontario the motto of the Spanish city because he thought that it was representing perfectly the feelings of the Ontarians.

Province of Ontario

Once constituted as a province, Ontario proceeded to assert its economic and legislative power. In 1872, the lawyer Oliver Mowat became Premier of Ontario and remained as premier until 1896. He fought for provincial rights, weakening the power of the federal government in provincial matters, usually through well-argued appeals to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. His battles with the federal government greatly decentralized Canada, giving the provinces far more power than John A. Macdonald had intended. He consolidated and expanded Ontario's educational and provincial institutions, created districts in Northern Ontario, and fought to ensure that those parts of Northwestern Ontario not historically part of Upper Canada (the vast areas north and west of the Lake Superior-Hudson Bay watershed, known as the District of Keewatin) would become part of Ontario, a victory embodied in the Canada (Ontario Boundary) Act, 1889. He also presided over the emergence of the province into the economic powerhouse of Canada. Mowat was the creator of what is often called Empire Ontario.

Beginning with Sir John A. Macdonald's National Policy (1879) and the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway (1875–1885) through Northern Ontario and the Canadian Prairies to British Columbia, Ontario manufacturing and industry flourished. However, population increase slowed after a large recession hit the province in 1893, thus slowing growth drastically but only for a few short years. Many newly arrived immigrants and others moved west along the railroad to the Prairie Provinces and British Columbia, sparsely settling Northern Ontario.

Mineral exploitation accelerated in the late 19th century, leading to the rise of important mining centres in the northeast like Sudbury, Cobalt and Timmins. The province harnessed its water power to generate hydro-electric power and created the state-controlled Hydro-Electric Power Commission of Ontario, later Ontario Hydro. The availability of cheap electric power further facilitated the development of industry. The Ford Motor Company of Canada was established in 1904. General Motors Canada was formed in 1918. The motor vehicle industry would go on to become the most lucrative industry for the Ontario economy during the 20th century.

In July 1912, the Conservative government of Sir James Whitney issued Regulation 17 which severely limited the availability of French-language schooling to the province's French-speaking minority. French Canadians reacted with outrage, journalist Henri Bourassa denouncing the "Prussians of Ontario". It was eventually repealed in 1927.

Influenced by events in the United States, the government of Sir William Hearst introduced prohibition of alcoholic drinks in 1916 with the passing of the Ontario Temperance Act. However, residents could distil and retain their own personal supply, and liquor producers could continue distillation and export for sale, which allowed this already sizable industry to strengthen further. Ontario became a hotbed for the illegal smuggling of liquor and the biggest supplier into the United States, which was under complete prohibition. Prohibition in Ontario came to an end in 1927 with the establishment of the Liquor Control Board of Ontario under the government of Howard Ferguson. The sale and consumption of liquor, wine, and beer are still controlled by some of the most extreme laws in North America to ensure that strict community standards and revenue generation from the alcohol retail monopoly are upheld. In April 2007, Ontario Member of Provincial Parliament Kim Craitor suggested that local brewers should be able to sell their beer in local corner stores; however, the motion was quickly rejected by Premier Dalton McGuinty.

The post-World War II period was one of exceptional prosperity and growth. Ontario, and the Greater Toronto Area in particular, have been the recipients of most immigration to Canada, largely immigrants from war-torn Europe in the 1950s and 1960s and after changes in federal immigration law, a massive influx of non-Europeans since the 1970s. From a largely ethnically British province, Ontario has rapidly become very culturally diverse.

The nationalist movement in Quebec, particularly after the election of the Parti Québécois in 1976, contributed to driving many businesses and English-speaking people out of Quebec to Ontario, and as a result Toronto surpassed Montreal as the largest city and economic centre of Canada. Depressed economic conditions in the Maritime Provinces have also resulted in de-population of those provinces in the 20th century, with heavy migration into Ontario.

Ontario has no official language, but English is considered the de facto language. Numerous French language services are available under the French Language Services Act of 1990 in designated areas where sizable francophone populations exist.

Demographics

Population since 1851

| Year | Population | Five-year % change |

Ten-year % change |

Rank among provinces |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1851 | 952,004 | n/a | 208.8 | 1 |

| 1861 | 1,396,091 | n/a | 46.6 | 1 |

| 1871 | 1,620,851 | n/a | 16.1 | 1 |

| 1881 | 1,926,922 | n/a | 18.9 | 1 |

| 1891 | 2,114,321 | n/a | 9.7 | 1 |

| 1901 | 2,182,947 | n/a | 3.2 | 1 |

| 1911 | 2,527,292 | n/a | 15.8 | 1 |

| 1921 | 2,933,662 | n/a | 16.1 | 1 |

| 1931 | 3,431,683 | n/a | 17.0 | 1 |

| 1941 | 3,787,655 | n/a | 10.3 | 1 |

| 1951 | 4,597,542 | n/a | 21.4 | 1 |

| 1956 | 5,404,933 | 17.6 | n/a | 1 |

| 1961 | 6,236,092 | 15.4 | 35.6 | 1 |

| 1966 | 6,960,870 | 11.6 | 28.8 | 1 |

| 1971 | 7,703,105 | 10.7 | 23.5 | 1 |

| 1976 | 8,264,465 | 7.3 | 18.7 | 1 |

| 1981 | 8,625,107 | 4.4 | 12.0 | 1 |

| 1986 | 9,101,695 | 5.5 | 10.1 | 1 |

| 1991 | 10,084,885 | 10.8 | 16.9 | 1 |

| 1996 | 10,753,573 | 6.6 | 18.1 | 1 |

| 2001 | 11,410,046 | 6.1 | 13.1 | 1 |

| 2006* | 12,160,282 | 6.6 | 11.6 | 1 |

Ethnic groups

| Ethnic | Responses | % |

|---|---|---|

| Total population | 12,028,895 | 100 |

| English | 2,971,360 | 24.7 |

| Canadian | 2,768,870 | 23.0 |

| Scottish | 2,101,100 | 17.5 |

| Irish | 1,988,940 | 16.5 |

| French | 1,351,600 | 11.2 |

| German | 1,144,560 | 9.5 |

| Italian | 867,980 | 7.2 |

| Chinese | 644,465 | 5.4 |

| East Indian | 573,250 | 4.8 |

| Dutch (Netherlands) | 490,995 | 4.1 |

| Polish | 465,560 | 3.9 |

| Ukrainian | 336,355 | 2.8 |

| North American Indian | 317,890 | 2.6 |

| Portuguese | 282,870 | 2.4 |

| Filipino | 215,750 | 1.8 |

| British, not included elsewhere |

205,755 | 1.7 |

| Jamaican | 197,540 | 1.6 |

| Welsh | 182,825 | 1.5 |

| Jewish | 177,255 | 1.5 |

| Russian | 167,365 | 1.4 |

| Hungarian (Magyar) | 151,750 | 1.3 |

| Spanish | 149,160 | 1.2 |

| Greek | 132,440 | 1.1 |

| American (USA) | 113,050 | 0.9 |

| Pakistani | 91,160 | 0.8 |

| Métis | 87,090 | 0.7 |

| Sri Lankan | 85,935 | 0.7 |

| Vietnamese | 83,330 | 0.7 |

| Romanian | 80,710 | 0.7 |

| African, not included elsewhere | 75,500 | 0.6 |

| Finnish | 72,990 | 0.6 |

| Korean | 72,065 | 0.6 |

| Croatian | 71,380 | 0.6 |

The percentages add to more than 100% because of dual responses (e.g. "French-Canadian" generates an entry in both the category "French" and the category "Canadian"). Groups with greater than 200,000 responses are included.

The majority of Ontarians are of British or other European descent. Slightly less than five percent of the population of Ontario is Franco-Ontarian, that is those whose native tongue is French, although those with French ancestry account for 11% of the population.

In relation to natural increase or inter-provincial migration, immigration is a huge population growth force in Ontario, as it has been over the last two centuries. More recent sources of immigrants with already large or growing communities in Ontario include Caribbeans (Jamaicans, Trinidadians, Guyanese, and Bajan), South Asians (e.g. Pakistanis, Indians, Bangladeshis and Sri Lankans), East Asians (mostly Chinese and Filipinos), Latin Americans (such as Colombians, Mexicans, Hondurans, Argentinans, and Ecuadorians), Eastern Europeans such as Russians and Bosnians, and groups from Somalia, Iran, and West Africa. Most populations have settled in the Greater Toronto area. A smaller number have settled in other cities such as London, Kitchener, Hamilton, Windsor, Barrie, and Ottawa.

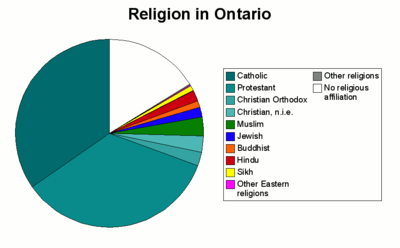

Religion

The largest denominations by number of adherents according to the 2001 census were the Roman Catholic Church with 3,866,350 (34 %); the United Church of Canada with 1,334,570 (12 %); and the Anglican Church of Canada with 985,110 (9 %).[25]

The major religious groups in Ontario, as of 2001, are:[26]

| Religion | People | % |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 11,285,545 | 100 |

| Protestant | 3,935,745 | 34.9 |

| Catholic | 3,911,760 | 34.7 |

| No Religion | 1,841,290 | 16.3 |

| Muslim | 352,530 | 3.1 |

| Other Christians | 301,935 | 2.7 |

| Christian Orthodox | 264,055 | 2.3 |

| Hindu | 217,555 | 1.9 |

| Jewish | 190,795 | 1.7 |

| Buddhist | 128,320 | 1.1 |

| Sikh | 104,785 | 0.9 |

| Eastern Religions | 17,780 | 0.2 |

| Other Religions | 18,985 | 0.2 |

Visible minorities and aboriginal peoples

Ontario is the second most diverse province in terms of visible minorities after British Columbia, with 22.8 per cent of the population consisting of visible minorities.[28] The Greater Toronto Area, Ottawa, Windsor, Hamilton and Waterloo Region are quite diverse cities.

Aboriginal peoples make up two per cent of the population, with two-thirds of that consisting of North American Indians and the other third consisting of Métis. The number of Aboriginal people has been increasing at rates greater than the general population of Ontario.[29]

Economy

Ontario is Canada's leading manufacturing province accounting for 52% of the total national manufacturing shipments in 2004.[30] Ontario's largest trading partner is the American state of Michigan.

Ontario's rivers, including its share of the Niagara River, make it rich in hydroelectric energy.[31] Since the privatization of Ontario Hydro which began in 1999, Ontario Power Generation runs 85% of electricity generated in the province, of which 41% is nuclear, 30% is hydroelectric and 29% is fossil fuel derived. Much of the newer power generation coming online in the last few years is natural gas or combined cycle natural gas plants. OPG is not however responsible for the transmission of power, which is under the control of Hydro One. Despite its diverse range of power options, problems related to increasing consumption, lack of energy efficiency and aging nuclear reactors, Ontario has been forced in recent years to purchase power from its neighbours Quebec and Michigan to supplement its power needs during peak consumption periods.

An abundance of natural resources, excellent transportation links to the American heartland and the inland Great Lakes making ocean access possible via container ships, have all contributed to making manufacturing the principal industry, found mainly in the Golden Horseshoe region, which is the largest industrialized area in Canada, the southern end of the region being part of the North American Rust Belt. Important products include motor vehicles, iron, steel, food, electrical appliances, machinery, chemicals, and paper. Ontario surpassed Michigan in car production, assembling 2.696 million vehicles in 2004.

However, as a result of steeply declining sales, in 2005, General Motors announced massive layoffs at production facilities across North America including two large GM plants in Oshawa and a drive train facility in St. Catharines resulting in 8,000 job losses in Ontario alone. In 2006, Ford Motor Company announced between 25,000 and 30,000 layoffs phased until 2012; Ontario was spared the worst, but job losses were announced for the St. Thomas facility and the Windsor Casting plant. However, these losses will be offset by Ford's recent announcement of a hybrid vehicle facility slated to begin production in 2007 at its Oakville plant and GM's re-introduction of the Camaro which will be produced in Oshawa. On December 4, 2008 Toyota announced the grand opening of the RAV4 plant in Woodstock,[32] and Honda also has plans to add an engine plant at its facility in Alliston. Despite these new plants coming online, Ontario has been hurt by layoffs created cause by the global recession, its unemployment rate is steadied at 9.2% (as of Jan. 2010) vs. roughly 6% in 2007.

Toronto, the capital of Ontario, is the centre of Canada's financial services and banking industry. Neighbouring cities in the Greater Toronto Area like Brampton, Mississauga and Vaughan are large product distribution and IT centres, in addition to having various manufacturing industries. The information technology sector is also important, particularly in the Silicon Valley North section of Ottawa , as well as the Waterloo Region. Government is the single largest employer in the National Capital Region employing hundreds of thousands. Hamilton is the largest steel manufacturing city in Canada, and Sarnia is the centre for petrochemical production. Construction employs at least 7% of the work force, this sector has slowed down somewhat after a ten year plus boom.

Mining and the forest products industry, notably pulp and paper, are vital to the economy of Northern Ontario. More than any other region, tourism contributes heavily to the economy of Central Ontario, peaking during the summer months owing to the abundance of fresh water recreation and wilderness found there in reasonable proximity to the major urban centres. At other times of the year, hunting, skiing and snowmobiling are popular. This region has some of the most vibrant fall colour displays anywhere on the continent, and tours directed at overseas visitors are organized to see them. Tourism also plays a key role in border cities with large casinos, among them Windsor, Cornwall, Sarnia and Niagara Falls, which attract many U.S. visitors.[33]

Agriculture

Once the dominant industry, agriculture occupies a small percentage of the population but still a large part of Southern Ontario's land area. The number of farms has decreased from 68,633 in 1991 to 59,728 in 2001, but farms have increased in average size, and many are becoming more mechanized. Cattle, small grains and dairy were the common types of farms in the 2001 census. The fruit, grape and vegetable growing industry is located primarily on the Niagara Peninsula and along Lake Erie, where tobacco farms are also situated. The Corn Belt covers much of the southwestern area of the province extending as far north as close to Goderich. Apple orchards are a common sight along the southern shore of Georgian Bay near Collingwood and along the northern shore of Lake Ontario near Cobourg. Tobacco production, centred in Norfolk County has decreased leading to an increase in some other new crop alternatives gaining popularity, such as hazelnuts and ginseng. The Ontario origins of Massey Ferguson, once one of the largest farm implement manufacturers in the world, indicate the importance agriculture once had to the Canadian economy.

Southern Ontario's limited supply of agricultural land is going out of production at an increasing rate. Urban sprawl and farmland severances contribute to the loss of thousands of acres of productive agricultural land in Ontario each year. Over 2,000 farms and 150,000 acres (61,000 ha) of farmland in the GTA alone were lost to production in the two decades between 1976 and 1996. This loss represented approximately 18% of Ontario's Class 1 farmland being converted to urban purposes. In addition, increasing rural severances provide ever-greater interference with agricultural production.

The 500,000, or so, acres (200,000 ha) comprising the black peat soil Holland Marsh, located just south of Lake Simcoe and near the town of Bradford West Gwillimbury (35 mi (56 km) north of Toronto) continues to be Canada's premier vegetable production center.

Energy

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2009) |

The Green Energy and Green Economy Act, 2009 (GEA), takes a two-pronged approach to creating a renewable-energy economy. The first is to bring more renewable energy sources to the province and the second is the creation of more energy efficiency measures to help conserve energy. The bill would also appoint a Renewable Energy Facilitator to provide "one-window" assistance and support to project developers in order to facilitate project approvals. The approvals process for transmission projects would also be streamlined and for the first time in Ontario, the bill would enact standards for renewable energy projects. Homeowners would have access to incentives to develop small-scale renewables such as low- or no-interest loans to finance the capital cost of renewable energy generating facilities like solar panels.[34]

Ontario is home to Niagara Falls, which supplies a large amount of clean, hydroelectric energy for the province. The Bruce Nuclear Generating Station, the second largest nuclear power plant in the world, is also in Ontario and uses 8 CANDU reactors to power the province with clean, reliable energy.

Transportation

Historically, the province has used two major east-west routes, both starting from Montreal in the neighbouring province of Quebec. The northerly route, which was pioneered by early French-speaking fur traders, travels northwest from Montreal along the Ottawa River, then continues westward towards Manitoba. Major cities on or near the route include Ottawa, North Bay, Sudbury, Sault Ste. Marie, and Thunder Bay. The much more heavily travelled southerly route, which was driven by growth in predominantly English-speaking settlements originated by the United Empire Loyalists and later other European immigrants, travels southwest from Montreal along the St. Lawrence River, Lake Ontario, and Lake Erie before entering the United States in Michigan. Major cities on or near the route include Kingston, Oshawa, Toronto, Mississauga, Kitchener-Waterloo, London, Sarnia, and Windsor. This route was also heavily used by immigrants to the Midwestern US particularly in the late 19th century. Most of Ontario's major transportation infrastructure is oriented east-west and roughly follows one of these two original routes.

Roads

400-Series Highways make up the primary vehicular network in the south of province, and they connect to numerous border crossings with the U.S., the busiest being the Detroit–Windsor Tunnel and Ambassador Bridge (via Highway 401) and the Blue Water Bridge (via Highway 402). The primary highway along the southern route is Highway 401/Highway of Heroes, the busiest highway in North America[35][36] and the backbone of Ontario's road network, tourism, and economy,[35][36] while the primary highways across the north are Highway 417/Highway 17 and Highway 11, both part of the Trans-Canada Highway. Highway 400/Highway 69 connects Toronto to Northern Ontario. Other provincial highways and regional roads inter-connect the remainder of the province.

Waterways

The Saint Lawrence Seaway, which extends across most of the southern portion of the province and connects to the Atlantic Ocean, is the primary water transportation route for cargo, particularly iron ore and grain. In the past, the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River were also a major passenger transportation route, but over the past half century passenger travel has been reduced to ferry services and sightseeing cruises.

Railways

Via Rail operates the inter-regional passenger train service on the Quebec City – Windsor Corridor, along with "The Canadian", a transcontinental rail service from Toronto to Vancouver, and "The Lake Superior", a regional rail service from Sudbury to White River. Additionally, Amtrak rail connects Ontario with key New York cities including Buffalo, Albany, and New York City. Ontario Northland provides rail service to destinations as far north as Moosonee near James Bay, connecting them with the south.

Freight rail is dominated by the founding cross-country Canadian National Railway and CP Rail companies, which during the 1990s sold many short rail lines from their vast network to private companies operating mostly in the south.

Regional commuter rail is limited to the provincially owned GO Transit, which serves a train/bus network spanning the Golden Horseshoe region, with its hub in Toronto.

The Toronto Transit Commission operates the province's only subway and streetcar system, one of the busiest in North America. The O-Train Light rail line operates in Ottawa with expansion of the line and proposals for additional lines.

Air travel

Toronto Pearson International Airport is the nation's busiest and the world's 29th busiest, handling over 30 million passengers per year. Other important airports include Ottawa Macdonald-Cartier International Airport and Hamilton's John C. Munro Hamilton International Airport, which is an important courier and freight aviation centre. Toronto/Pearson and Ottawa/Macdonald-Cartier form two of the three points in Canada's busiest set of air routes (the third point is Montréal-Pierre Elliott Trudeau International Airport).

Most Ontario cities have regional airports, many of which have scheduled commuter flights from Air Canada Jazz or smaller airlines and charter companies — flights from the larger cities such as Thunder Bay, Sault Ste. Marie, Sudbury, North Bay, Timmins, Windsor, London, and Kingston feed directly into Toronto Pearson. Bearskin Airlines also runs flights along the northerly east-west route, connecting Ottawa, North Bay, Sudbury, Sault Ste. Marie, and Thunder Bay directly without requiring connections at Toronto Pearson.

Isolated towns and settlements in the northern areas of the province rely partly or entirely on air service for travel, goods, and even ambulance services (MEDIVAC), since much of the far northern area of the province cannot be reached by road or rail.

Government

The British North America Act 1867 section 69 stipulated "There shall be a Legislature for Ontario consisting of the Lieutenant Governor and of One House, styled the Legislative Assembly of Ontario." The assembly has 107 seats representing ridings elected in a first-past-the-post system across the province. The legislative buildings at Queen's Park in Toronto are the seat of government. Following the Westminster system, the leader of the party holding the most seats in the assembly is known as the "Premier and President of the Council" (Executive Council Act R.S.O. 1990). The Premier chooses the cabinet or Executive Council whose members are deemed "ministers of the Crown." Although the Legislative Assembly Act (R.S.O. 1990) refers to members of the assembly, the legislators are now commonly called MPPs (Members of the Provincial Parliament) in English and députés de l'Assemblée législative in French, but they have also been called MLAs (Members of the Legislative Assembly), and both are acceptable. The title of Prime Minister of Ontario, correct in French (le Premier ministre), is permissible in English but now generally avoided in favour of the title "Premier" to avoid confusion with the Prime Minister of Canada.

Politics

Ontario has traditionally operated under a three-party system. In the last few decades the liberal Ontario Liberal Party, conservative Progressive Conservative Party of Ontario, and social-democratic Ontario New Democratic Party have all ruled the province at different times.

Ontario is currently under a Liberal government headed by Premier Dalton McGuinty. The present government, first elected in 2003, was re-elected on October 10, 2007.

Federally, Ontario is known as being the province that offers strong support for the Liberal Party of Canada. Currently, half of the party's 76 seats in the Canadian House of Commons represent Ontario ridings, although, in the 2008 federal election, for the first time since the Mulroney government, the Conservatives won a plurality of the seats and the vote. As the province has the most seats of any province in Canada, earning support from Ontario voters is considered a crucial matter for any party hoping to win a Canadian federal election.

Urban areas

Census Metropolitan Areas

Statistics Canada's measure of a "metro area", the Census Metropolitan Area (CMA), roughly bundles together population figures from the core municipality with those from "commuter" municipalities.[37]

| CMA (largest other included municipalities in brackets) | 2006 | 2001 |

|---|---|---|

| Toronto CMA (Region of Peel, Region of York, Pickering) | 5,113,149 | 4,682,897 |

| Ottawa CMA (Gatineau, Clarence-Rockland, Russell)* | 1,130,761* | 1,067,800* |

| Hamilton CMA (Burlington, Grimsby) | 692,911 | 662,401 |

| London CMA (St. Thomas, Strathroy-Caradoc) | 457,720 | 435,600 |

| Kitchener CMA (Cambridge, Waterloo) | 451,235 | 414,284 |

| St. Catharines CMA (Niagara Falls, Welland) | 390,317 | 377,009 |

| Oshawa CMA (Whitby, Clarington) | 330,594 | 296,298 |

| Windsor CMA (Lakeshore, LaSalle) | 323,342 | 307,877 |

| Barrie CMA (Innisfil, Springwater) | 177,061 | 148,480 |

| Sudbury CMA (Whitefish Lake, Wanapitei Reserve) | 158,258 | 155,601 |

| Kingston CMA | 152,358 | 146,838 |

*Parts of Quebec (including Gatineau) are included in the Ottawa CMA. The entire population of the Ottawa CMA, in both provinces, is shown. Clarence-Rockland and Russell Township are not the second and third largest municipalities in the entire CMA, they are the largest municipalities in the Ontario section of the CMA.

Municipalities

- Ten largest municipalities by population[20]

| Municipality | 2006 | 2001 | 1996 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Toronto (Provincial capital) | 2,503,281 | 2,481,494 | 2,385,421 |

| Ottawa (National capital) | 812,129 | 774,072 | 721,136 |

| Mississauga | 668,549 | 612,925 | 544,382 |

| Hamilton | 504,559 | 490,268 | 467,799 |

| Brampton | 433,806 | 325,428 | 268,251 |

| London | 352,395 | 336,539 | 325,669 |

| Markham | 261,573 | 208,615 | 173,383 |

| Vaughan | 238,866 | 182,022 | 132,549 |

| Windsor | 216,473 | 209,218 | 197,694 |

| Kitchener | 204,668 | 190,399 | 178,420 |

Songs and slogans

During the John Robarts government of the 1960s, the slogan "Is There Any Other Place You'd Rather Be?" was in use to promote tourism. During a blizzard early in 1971, highway travellers stranded at a Highway 401 service centre, with Premier Robarts (in his last months of office), asked him the slogan in an ironic twist.

In 1967, in conjunction with the celebration of Canada's centennial, the song "A Place to Stand" was introduced at the inauguration of Ontario's pavilion at the Expo 67 World's Fair, and became the background for the province's advertising for decades.

In 1973 the first slogan to appear on licence plates in Ontario was "Keep It Beautiful". This was replaced by "Yours to Discover" in 1982,[38] apparently inspired by a tourism slogan, "Discover Ontario," dating back to 1927.[39] (From 1988 to 1990,[40] "Ontario Incredible"[41] gave "Yours to Discover" a brief respite.)

In 2007, a new song replaced "A Place to Stand" after four decades. "There's No Place Like This" (Un Endroit Sans Pareil) is featured in current television advertising, performed by Ontario artists including Molly Johnson, Brian Byrne, Keshia Chanté (from Ottawa),[42] as well as Tomi Swick and Arkells (both from Hamilton).

Famous Ontarians

Please see List of people from Ontario.

See also

Notes

- ^ a b "Canada's provinces and territories total area, land area and water area". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 2007-01-05.

- ^ "Ontario Budget 2007: Chapter II". Fin.gov.on.ca. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ^ "Ontario." Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary, 11th ed. 2003. (ISBN 0-87779-809-5) New York: Merriam-Webster, Inc."

- ^ Ontario is located in the eastern part of Canada, but is also historically and politically considered to be part of Central Canada (with Quebec).

- ^ "Ontario is the largest province in the country by population". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 2007-01-05.

- ^ "Population of census metropolitan areas (2001 Census boundaries)". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 2007-01-05.

- ^ Mithun, Marianne (2000). The Languages of Native North America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 312.

- ^ "About Canada // Ontario". Study Canada. pp. Last Paragraph-second last sentence. Retrieved 2007-01-05.

Ontario's name is thought to come form the Iroquois word "Skanadario" which means "beautiful water"

- ^ Mills, David (1877). Report on the Boundaries of the Province of Ontario. Toronto: Hunter, Rose & Co. p. 347. Retrieved 2009-09-14.

- ^ "Early Districts and Counties 1788-1899". Archives of Ontario. 2006-09-05. Retrieved 2006-11-29.

- ^ "About Ontario; History: Government of Ontario". Retrieved 2007-01-05.[dead link]

- ^ "Native America on the Eve of Contact". Digital History.

- ^ "Étienne Brûlé's article on Encyclopædia Britannica". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2007-01-05.

- ^ a b "About Ontario; History; French and British Struggle for Domination". Government of Ontario. Retrieved 2007-01-05.[dead link]

- ^ "The Contact Period". Ontarioarchaeology.on.ca.

- ^ "The Treaty of Paris (1763)". Retrieved 2007-01-05.

- ^ "The Quebec Act of 1774". Retrieved 2007-01-15.

- ^ "The Constitutional Act of 1791". Retrieved 2007-01-15.[dead link]

- ^ Virtual Vault, an online exhibition of Canadian historical art at Library and Archives Canada

- ^ a b "Population and dwelling counts, for Canada, provinces and territories, and census subdivisions (municipalities), 2006 and 2001 censuses - 100% data". Statistics Canada, 2006 Census of Population. 2007-03-13. Retrieved 2007-03-13.

- ^ "Population urban and rural, by province and territory (Ontario)". Statistics Canada. 2005-09-01. Retrieved 2006-11-29.

- ^ "Canada's population". The Daily. Statistics Canada. 2006-09-27. Retrieved 2006-11-29.

- ^ "Selected Ethnic Origins1, for Canada, Provinces and Territories - 20% Sample Data". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 2007-12-18.

- ^ "Ethnocultural Portrait of Canada Highlight Tables, 2006 Census". Statistics Canada. 2008-04-02. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ^ Selected Religions, for Canada, Provinces and Territories - 20% Sample Data

- ^ "Population by religion, by province and territory (2001 Census) (Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan)". Statistics Canada. 2005-01-25. Retrieved 2006-11-07.

- ^ Statistics Canada "2001 Community Profiles". Statistics Canada. 2006-12-14. Retrieved 2007-01-12.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ "Ethnocultural Portrait of Canada Highlight Tables, 2006 Census". 2.statcan.ca. 2008-04-02. Retrieved 2009-06-16.

- ^ StatCan - Native Population

- ^ Government of Ontario. "Ontario Facts: Overview". Retrieved 2007-01-05.[dead link]

- ^ "Ontario is rich in hydroelectricity, especially areas near the Niagara River". Ontario Facts. Retrieved 2007-02-02.[dead link]

- ^ Toyota's opening a new chapter in Woodstock's industrial history

- ^ "Ontario". Ministry of Economic Development and Trade. Retrieved 2006-11-29.[dead link]

- ^ Ontario Unveils Green Energy and Green Economy Act, 2009

- ^ a b c Ministry of Transportation (Ontario) (August 6, 2002). "Ontario government investing $401 million to upgrade Highway 401". Retrieved 2006-12-20.

- ^ a b c Brian Gray (2004-04-10). "GTA Economy Dinged by Every Crash on the 401 - North America's Busiest Freeway". Toronto Sun, transcribed at Urban Planet. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

The "phenomenal" number of vehicles on Hwy. 401 as it cuts through Toronto makes it the busiest freeway in the world...

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Statistics Canada "Population and dwelling counts, for Canada, provinces and territories, census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations, 2006 and 2001 censuses - 100% data". Statistics Canada. 2008-11-05. Retrieved 2009-04-01.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ "Ontario". 15q.net. 2007-02-24. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ^ "| Library | University of Waterloo". Lib.uwaterloo.ca. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ^ Official Ontario Road Maps Produced -1971 - 2006

- ^ Measuring the Returns to Tourism Advertising - Butterfield et al. 37 (1): 12 - Journal of Travel Research

- ^ There's more to discover in Ontario

References

- Michael Sletcher, 'Ottawa', in James Ciment, ed., Colonial America: An Encyclopedia of Social, Political, Cultural, and Economic History, (5 vols., M. E. Sharpe, New York, 2006).

- Virtual Vault, an online exhibition of Canadian historical art at Library and Archives Canada

Further reading

Ontario

- Celebrating One Thousand Years of Ontario's History: Proceedings of the Celebrating One Thousand Years of Ontario's History Symposium, April 14, 15, and 16, 2000. Ontario Historical Society, 2000. 343 pp.

- Baskerville, Peter A. Sites of Power: A Concise History of Ontario. Oxford U. Press., 2005. 296 pp. (first edition was Ontario: Image, Identity and Power, 2002). online review

- Berton, Pierre. Niagara: A History of the Falls. (1992).

- Hall, Roger; Westfall, William; and MacDowell, Laurel Sefton, eds. Patterns of the Past: Interpreting Ontario's History. Dundurn Pr., 1988. 406 pp.

- McGowan, Mark George and Clarke, Brian P., eds. Catholics at the "Gathering Place": Historical Essays on the Archdiocese of Toronto, 1841-1991. Canadian Catholic Historical Assoc.; Dundurn, 1993. 352 pp.

- McKillop, A. B. Matters of Mind: The University in Ontario, 1791-1951. U. of Toronto Press, 1994. 716 pp.

- Mays, John Bentley. Arrivals: Stories from the History of Ontario. Penguin Books Canada, 2002. 418 pp.

- Noel, S. J. R. Patrons, Clients, Brokers: Ontario Society and Politics, 1791-1896. U. of Toronto Press, 1990.

Ontario to 1869

- Careless, J. M. S. Brown of the Globe (2 vols, Toronto, 1959–63), vol 1: The Voice of Upper Canada 1818-1859; vol 2: The Statesman of Confederation 1860-1880.

- Clarke, John. Land Power and Economics on the Frontier of Upper Canada (2001) 747pp.

- Clarke, John. The Ordinary People of Essex: Environment, Culture, and Economy on the Frontier of Upper Canada (2010)

- Cohen, Marjorie Griffin. Women's Work, Markets, and Economic Development in Nineteenth-Century Ontario. (1988). 258 pp.

- Craig, Gerald M Upper Canada: the formative years 1784-1841 McClelland and Stewart, 1963, the standard history online edition

- Dunham, Eileen Political unrest in Upper Canada 1815-1836 (1963).

- Errington, Jane The Lion, the Eagle, and Upper Canada: A Developing Colonial Ideology (1987).

- Gidney, R. D. and Millar, W. P. J. Professional Gentlemen: The Professions in Nineteenth-Century Ontario. (1994).

- Grabb, Edward, James Curtis, Douglas Baer; "Defining Moments and Recurring Myths: Comparing Canadians and Americans after the American Revolution" The Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology, Vol. 37, 2000

- Johnson, J. K. and Wilson, Bruce G., eds. Historical Essays on Upper Canada: New Perspectives. (1975). . 604 pp.

- Keane, David and Read, Colin, ed. Old Ontario: Essays in Honour of J. M. S. Careless. (1990).

- Kilbourn, William.; The Firebrand: William Lyon Mackenzie and the Rebellion in Upper Canada (1956) online edition

- Knowles, Norman. Inventing the Loyalists: The Ontario Loyalist Tradition and the Creation of Usable Pasts. (1997). 244 pp.

- Landon, Fred, and J.E. Middleton. Province of Ontario: A History (1937) 4 vol. with 2 vol of biographies

- Lewis, Frank and Urquhart, M.C. Growth and standard of living in a pioneer economy: Upper Canada 1826-1851 Institute for Economic Research, Queen's University, 1997.

- McCalla, Douglas Planting the province: the economic history of Upper Canada 1784-1870 (1993).

- McGowan, Mark G. Michael Power: The Struggle to Build the Catholic Church on the Canadian Frontier. (2005). 382 pp. online review from H-CANADA

- McNairn, Jeffrey L The capacity to judge: public opinion and deliberative democracy in Upper Canada 1791-1854 (2000). online review from H-CANADA

- Oliver, Peter. "Terror to Evil-Doers": Prisons and Punishments in Nineteenth-Century Ontario. (1998). 575 pp. post 1835

- Rea, J. Edgar. "Rebellion in Upper Canada, 1837" Manitoba Historical Society Transactions Series 3, Number 22, 1965–66, historiography online edition

- Reid, Richard M. The Upper Ottawa Valley to 1855. (1990). 354 pp.

- Rogers, Edward S. and Smith, Donald B., eds. Aboriginal Ontario: Historical Perspectives on the First Nations. (1994). 448 pp.

- Styran, Roberta M. and Taylor, Robert R., ed. The "Great Swivel Link": Canada's Welland Canal. Champlain Soc., 2001. 494 pp.

- Westfall, William. Two Worlds: The Protestant Culture of Nineteenth-Century Ontario. (1989). 265 pp.

- Wilton, Carol. Popular Politics and Political Culture in Upper Canada, 1800-1850. (2000). 311pp

Ontario since 1869

- Azoulay, Dan. Keeping the Dream Alive: The Survival of the Ontario CCF/NDP, 1950-1963. (1997). 307 pp.

- Baskerville, Peter A. Ontario: Image, Identity, and Power. (2002). 256pp

- Cameron, David R. and White, Graham. Cycling into Saigon: The Conservative Transition in Ontario. (2000). 224 pp. Analysis of the 1995 transition from New Democratic Party (NDP) to Progressive Conservative (PC) rule in Ontario

- Comacchio, Cynthia R. Nations Are Built of Babies: Saving Ontario's Mothers and Children, 1900-1940. (1993). 390 pp.

- Cook, Sharon Anne. "Through Sunshine and Shadow": The Woman's Christian Temperance Union, Evangelicalism, and Reform in Ontario, 1874-1930. (1995). 281 pp.

- Darroch, Gordon and Soltow, Lee. Property and Inequality in Victorian Ontario: Structural Patterns and Cultural Communities in the 1871 Census. U. of Toronto Press, 1994. 280 pp.

- Devlin, John F. "A Catalytic State? Agricultural Policy in Ontario, 1791-2001." PhD dissertation U. of Guelph 2004. 270 pp. DAI 2005 65(10): 3972-A. DANQ94970 Fulltext: in ProQuest Dissertations & Theses

- Evans, A. Margaret. Sir Oliver Mowat. U. of Toronto Press, 1992. 438 pp. Premier 1872-1896

- Fleming, Keith R. Power at Cost: Ontario Hydro and Rural Electrification, 1911-1958. McGill-Queen's U. Press, 1992. 326 pp.

- Gidney, R. D. From Hope to Harris: The Reshaping of Ontario's Schools. U. of Toronto Press, 1999. 362 pp. deals with debates and changes in education from 1950 to 2000

- Gidney, R. D. and Millar, W. P. J. Inventing Secondary Education: The Rise of the High School in Nineteenth-Century Ontario. McGill-Queen's U. Press, 1990. 440 pp.

- Halpern, Monda. And on that Farm He Had a Wife: Ontario Farm Women and Feminism, 1900-1970. (2001). 234 pp. online review from H-CANADA

- Hines, Henry G. East of Adelaide: Photographs of Commercial, Industrial and Working-Class Urban Ontario, 1905-1930. London Regional Art and History Museum, 1989.

- Hodgetts, J. E. From Arm's Length to Hands-On: The Formative Years of Ontario's Public Service, 1867-1940. U. of Toronto Press, 1995. 296 pp.

- Houston, Susan E. and Prentice, Alison. Schooling and Scholars in Nineteenth-Century Ontario. U. of Toronto Press, 1988. 418 pp.

- Ibbitson, John. Promised Land: Inside the Mike Harris Revolution. Prentice-Hall, 1997. 294 pp. praise for Conservatives

- Kechnie, Margaret C. Organizing Rural Women: the Federated Women's Institutes of Ontario, 1897-1910. McGill-Queen's U. Press, 2003. 194 pp.

- Landon, Fred, and J.E. Middleton. Province of Ontario: A History (1937) 4 vol. with 2 vol of biographies

- Marks, Lynne. Revivals and Roller Rinks: Religion, Leisure and Identity in Late Nineteenth-Century Small-Town Ontario. U. of Toronto Press, 1996. 330 pp.

- Montigny, Edgar-Andre, and Lori Chambers, eds. Ontario since Confederation: A Reader (2000).

- Moss, Mark. Manliness and Militarism: Educating Young Boys in Ontario for War. (2001). 216 pp.

- Neatby, H. Blair and McEown, Don. Creating Carleton: The Shaping of a University. McGill-Queen's U. Press, 2002. 240 pp.

- Ontario Bureau of Statistics and Research. A Conspectus of the Province of Ontario (1947) online edition

- Parr, Joy, ed. A Diversity of Women: Ontario, 1945-1980. U. of Toronto Press, 1996. 335 pp.

- Ralph, Diana; Régimbald, André; and St-Amand, Nérée, eds. Open for Business, Closed for People: Mike Harris's Ontario. Fernwood, 1997. 207 pp. leftwing attack on Conservative party of 1990s

- Roberts, David. In the Shadow of Detroit: Gordon M. McGregor, Ford of Canada, and Motoropolis. Wayne State U. Press, 2006. 320 pp.

- Santink, Joy L. Timothy Eaton and the Rise of His Department Store. U. of Toronto Press, 1990. 319 pp.

- Saywell, John T. "Just Call Me Mitch": The Life of Mitchell F. Hepburn. U. of Toronto Press, 1991. 637 pp. Biography of Liberal premier 1934-1942

- Schryer, Frans J. The Netherlandic Presence in Ontario: Pillars, Class and Dutch Ethnicity. Wilfrid Laurier U. Press, 1998. 458 pp. focus is post WW2

- Schull, Joseph. Ontario since 1867 (1978), narrative history

- Stagni, Pellegrino. The View from Rome: Archbishop Stagni's 1915 Reports on the Ontario Bilingual Schools Question. McGill-Queen's U. Press, 2002. 134 pp.

- Warecki, George M. Protecting Ontario's Wilderness: A History of Changing Ideas and Preservation Politics, 1927-1973.' Lang, 2000. 334 pp.

- White, Graham, ed. The Government and Politics of Ontario. 5th ed. U. of Toronto Press, 1997. 458 pp.

- White, Randall. Ontario since 1985. Eastendbooks, 1998. 320 pp.

- Wilson, Barbara M. ed. Ontario and the First World War, 1914-1918: A Collection of Documents (Champlain Society, 1977)

External links

- Canadian Government Atlas - Official Map of Ontario.

- CBC Digital Archives - Ontario Elections: Twenty Tumultuous Years

- Government of Ontario - Official website of the Provincial government.

- Ontario Visual Heritage Project - Non-profit documentary project about Ontario's history

- OntarioWire - Ontario news wire service

- Tourism Ontario - Official tourism website of the Province of Ontario