Languages of the United States: Difference between revisions

ClueBot NG (talk | contribs) m Reverting possible vandalism by 92.29.190.123 to version by 129.98.44.182. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot NG. (216467) (Bot) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Languages of |

{{Languages of |

||

|country = the United States |

|country = the United States |

||

|official = |

|official = English |

||

|main = {{nowrap|[[American English|English]] 82.1%,}} {{nowrap|[[Spanish in the United States|Spanish]] 10.7%,}} {{nowrap|other [[Indo-European languages|Indo-European]] 3.8%,}} {{nowrap|[[Languages of Asia|Asian]] and [[Indo-Pacific languages|Pacific island]] languages 2.7%,}} {{nowrap| other languages 0.7% (2000 census)}}<ref>[https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/us.html United States], CIA World Factbook.</ref> |

|main = {{nowrap|[[American English|English]] 82.1%,}} {{nowrap|[[Spanish in the United States|Spanish]] 10.7%,}} {{nowrap|other [[Indo-European languages|Indo-European]] 3.8%,}} {{nowrap|[[Languages of Asia|Asian]] and [[Indo-Pacific languages|Pacific island]] languages 2.7%,}} {{nowrap| other languages 0.7% (2000 census)}}<ref>[https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/us.html United States], CIA World Factbook.</ref> |

||

|minority = <!--can be left blank as all minority languages are either indigenous or immigrant languages--> |

|minority = <!--can be left blank as all minority languages are either indigenous or immigrant languages--> |

||

Revision as of 04:08, 24 January 2011

English is the de facto national language of the United States, with 82% of the population claiming it as a mother tongue, and some 96% claiming to speak it "well" or "very well".[3] However, no official language exists at the Federal level. There have been several proposals to make English the national language in amendments to immigration reform bills,[4][5] but none of these bills has become law with the amendment intact. The situation is quite varied at the State and Territorial levels, with some states mirroring the Federal policy of adopting no official language in a de jure capacity, others adopting English alone, others officially adopting English as well as local languages, and still others adopting a policy of de facto bilingualism.

The variety of English spoken in the United States is known as American English; together with Canadian English it makes up the group of dialects known as North American English.

Spanish is the second most common language in the country, and is spoken by over 12% of the population.[6] The United States holds the world's fifth largest Spanish-speaking population, outnumbered only by Mexico, Spain, Argentina, and Colombia. Throughout the Southwestern United States, long-established Spanish-speaking communities coexist with large numbers of more recent Hispanophone immigrants. Although many new Latin American immigrants are less than fluent in English, nearly all second-generation Hispanic Americans speak English fluently, while only about half still speak Spanish.[7]

According to the 2000 US census, people of German ancestry make up the largest single ethnic group in the United States, and the German language ranks fifth.[8][9] Italian, Polish, and Greek are still widely spoken among populations descending from immigrants from those countries in the early 20th century, but the use of these languages is dwindling as older generations pass away. Russian is also spoken by immigrant populations.

Tagalog and Vietnamese have over one million speakers in the United States, almost entirely within recent immigrant populations. Both languages, along with the varieties of the Chinese language, Japanese, and Korean, are now used in elections in Alaska, California, Hawaii, Illinois, New York, Texas, and Washington.[10]

There is also a population of Native Americans who still speak their native languages, but these populations are decreasing, and the languages are almost never widely used outside of reservations. Hawaiian, although having few native speakers, is an official language along with English at the state level in Hawaii. The state government of Louisiana offers services and documents in French, as does New Mexico in Spanish. Besides English, Spanish, French, German, Navajo and other Native American languages, all other languages are usually learned from immigrant ancestors that came after the time of independence or learned through some form of education.

Approximately 337 languages are spoken or signed by the population, of which 176 are indigenous to the area. 52 languages formerly spoken in the country's territory are now extinct.[11]

Census statistics

| Language Spoken at Home (U.S. Census 2000) Summary[12] | |

|---|---|

| List |

|

According to the 2000 census,[9] the main languages by number of speakers older than five are:

- English - 215 million

- Spanish - 28 million

- Chinese languages - 2.0 million + (mostly Cantonese speakers, with a growing group of Mandarin speakers)

- French - 1.6 million

- German - 1.4 million (High German) + German dialects like Hutterite German, Texas German, Pennsylvania German, Plautdietsch

- Tagalog - 1.2 million + (Most Filipinos may also know other Philippine languages, e.g. Ilokano, Pangasinan, Bikol languages, and Visayan languages)

- Vietnamese - 1.01 million

- Italian - 1.01 million

- Korean - 890,000

- Russian - 710,000

- Polish - 670,000

- Arabic - 610,000

- Portuguese - 560,000

- Japanese - 480,000

- French Creole - 450,000 (mostly Louisiana Creole French - 334,500)

- Greek - 370,000

- Hindi - 320,000

- Persian - 310,000

- Urdu - 260,000

- Gujarati - 240,000

- Armenian - 200,000

Additionally, some estimates indicate that American Sign Language is spoken by as many as 2 million Americans.[citation needed]

Official language status

The United States does not have a national official language; nevertheless, English (specifically American English) is the primary language used for legislation, regulations, executive orders, treaties, federal court rulings, and all other official pronouncements; although there are laws requiring documents such as ballots to be printed in multiple languages when there are large numbers of non-English speakers in an area.

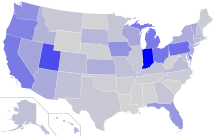

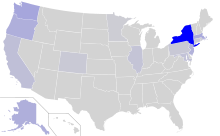

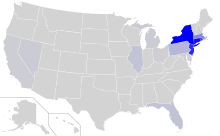

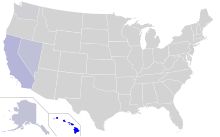

As part of what has been called the English-only movement, some states have adopted legislation granting official status to English. Currently, out of 50 total states, 27 have established English as the official language, while another, Hawaii, has established both English and Hawaiian as official languages.

States with official English

- Alabama (1990)[13]

- Alaska (2007)[citation needed]

- Arizona (2006)[14]

- Arkansas (1987)[15]

- California (1986)[16]

- Colorado (1988)[17]

- Florida (1988)[18]

- Georgia (1986, 1996)[19]

- Idaho (2007)[20]

- Illinois (1969)[21]

- Indiana (1984)[22]

- Iowa (2002)[23]

- Kansas (2007) [24]

- Kentucky (1984)[25]

- Mississippi (1987)[26]

- Missouri (1998)[27]

- Montana (1995)[28]

- Nebraska (1920)[29]

- New Hampshire (1995)[30]

- North Carolina (1987)[31]

- North Dakota (1987)[32]

- Oklahoma (2010)[33]

- South Carolina (1987)[34]

- South Dakota (1987)[35]

- Tennessee (1984)[36]

- Utah (2000)[37]

- Virginia (1981, 1996)[38]

- Wyoming (1996)[39]

States without official English

States and territories that are officially bi- or trilingual

- Hawaii (English and Hawaiian) (1978)

- American Samoa (Samoan and English)

- Guam (Chamorro and English)

- Northern Mariana Islands (English, Chamorro, and Carolinian)

- Puerto Rico (Spanish and English) (1993)

States that are de facto bilingual

- Louisiana (English and French legally recognized, although there is no official language) (1974)

- Maine (English and French both de facto)

- New Mexico (English and Spanish both de facto)[40]

Status of other languages

The State of Alaska provides voting information in Iñupiaq, Central Yup'ik, Gwich'in, Siberian Yupik, Koyukon, and Tagalog, as well as English.

California has agreed to allow the publication of state documents in other languages to represent minority groups and immigrant communities. Languages such as Spanish, Chinese, Korean, Tagalog, Persian, Russian, Vietnamese, and Thai appear in official state documents, and the Department of Motor Vehicles publishes in 9 languages.[41]

In New Mexico, although the state constitution does not specify an official language, laws are published in English and Spanish, and government material and services are legally required (by Act) to be made accessible to speakers of both languages. Some have asserted that the New Mexico situation is part of the provisions in the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo; however, no mention of "language rights" is made in the Treaty or in the Protocol of Querétaro, beyond the "Mexican inhabitants" having (1) no reduction of rights below those of citizens of the United States and (2) precisely the same rights as are mentioned in Article III of the Treaty of the Louisiana Purchase and in the Treaty of the Florida Purchase. This would imply that the legal status of the Spanish language in New Mexico and in non-Gadsden Purchase areas of Arizona is the same as of French in Louisiana and certainly not less than that of German in Pennsylvania.

Contrary to belief, the state of Pennsylvania was never officially bilingual, the state has a history of Pennsylvania Dutch German language communities that goes back to the 1650s. There were attempts to recognize German in Pennsylvania in the 18th and 19th centuries due to the prevalence of German speakers in the state. This situation prevailed until the 1950s in some rural areas.[citation needed]

The state of New York had state government documents (i.e., vital records) co-written in the Dutch language until the 1920s, in order to preserve the legacy of New Netherland, though England annexed the colony in 1664.[42]

Native American languages are official or co-official on many of the U.S. Indian reservations and pueblos. In Oklahoma before statehood in 1907, territory officials debated whether or not to have Cherokee, Choctaw and Muscogee languages as co-official, but the idea never gained ground.

The issue of bilingualism also applies in the states of Arizona and Texas, while the constitution of Texas has no official language policy. Arizona passed a proposition in the November 7, 2006 general election declaring English as the official language.[43] Nonetheless, Arizona law requires the distribution of voting ballots in languages such as Navajo and Tohono O'odham in certain counties.[44]

In 2000, the census bureau printed the standard census questionnaires in six languages: English, Spanish, Korean, Chinese (in traditional characters), Vietnamese, and Tagalog.

Indigenous languages

Native American languages

The Native American languages predate European settlement of the New World. In a few parts of the U.S. (mostly on Indian reservations), they continue to be spoken fluently. Most of these languages are endangered, although there are efforts to revive them. Normally the fewer the speakers of a language the greater the degree of endangerment, but there are many small Native American language communities in the Southwest (Arizona and New Mexico) which continue to thrive despite their small size. In 1929, speaking of indigenous Native American languages, linguist Edward Sapir observed:

"Few people realize that within the confines of the United States there is spoken today a far greater variety of languages ... than in the whole of Europe. We may go further. We may say, quite literally and safely, that in the state of California alone there are greater and more numerous linguistic extremes than can be illustrated in all the length and breadth of Europe."[45]

According to the 2000 Census and other language surveys, the largest Native American language-speaking community by far is the Navajo. The largest communities are:

Navajo

178,000 speakers. Navajo is one of the Athabascan languages of the Na-Dené family.

Dakota

Dakota has 18,000 speakers (22,000 including speakers in Canada), not counting 6,000 speakers of the closely related Lakota. Dakota is a member of the Siouan language family.

Central Alaskan Yup'ik

Central Alaskan Yup'ik has 16,000 speakers. The Yup'ik are part of the Eskimo-Aleut language family but are not Inuit.

Cherokee

Cherokee belongs to the Iroquoian language family, and had about 22,000 speakers as of 2005.[46] The Cherokee have the largest tribal affiliation in the U.S., but most are of mixed ancestry and do not speak the language. Recent efforts to preserve and increase the Cherokee language in Oklahoma and the Cherokee Indian reservation in North Carolina have been productive.

Western Apache

Western Apache, with 12,500 speakers, is a Southern Athabaskan language closely related to Navajo, but not mutually intelligible with it.

Piman

Piman dialects (Pima and Tohono O'odham) have more than 12,000 speakers. Piman is one of the Uto-Aztecan languages along with Hopi, Comanche, Huichol, and Aztec.

Choctaw

Choctaw has 11,000 speakers. One of the Muskogean language family, like Seminole and Alabama.

Keres

Keres has 11,000 speakers. A language isolate, the Keres are the largest of the Pueblo nations. The Keres pueblo of Acoma is the oldest continually inhabited community in the United States.

Zuni

Zuni has 10,000 speakers. Zuni is a language isolate mostly spoken in a single pueblo, Zuni, the largest in the U.S.

Ojibwe

Ojibwe has 7,000 speakers (about 55,000 including speakers in Canada). The Algonquian language family includes populous languages like Cree in Canada.

Other languages

Many other languages have been spoken within the current borders of the United States. The following is a list of 28 language families (groups of demonstrably related languages) indigenous to the territory of the continental United States.

In addition to the above list of families, there are many languages in the United States that are sufficiently well-known to attempt to classify but which have not been shown to be related to any other language in the world. These 25 language isolates are listed below. With further study, some of these will likely prove to be related to each other or to one of the established families. There are also larger and more contentious proposals such as Penutian and Hokan.

Since the languages in the Americas have a history stretching for about 17,000 to 12,000 years, current knowledge of American languages is limited. There are doubtless a number of languages that were spoken in the United States that are missing from historical record.

Native American sign languages

A sign-language trade pidgin, known as Plains Indian Sign Language or Plains Standard, arose among the Plains Indians. Each signing nation had a separate signed version of their spoken language, that was used by the hearing, and these were not mutually intelligible. Plains Standard was used to communicate between these nations. It seems to have started in Texas and then spread north, through the Great Plains, as far as British Columbia. There are still a few users today, especially among the Crow, Cheyenne, and Arapaho. Unlike other sign languages developed by hearing people, it shares the spatial grammar of deaf sign languages.

Austronesian languages

Hawaiian

Hawaiian is an official state language of Hawaii as prescribed in the Constitution of Hawaii. Hawaiian has 1,000 native speakers. Formerly considered critically endangered, Hawaiian is showing signs of language renaissance. The recent trend is based on new Hawaiian language immersion programs of the Hawaii State Department of Education and the University of Hawaii, as well as efforts by the Hawaii State Legislature and county governments to preserve Hawaiian place names. In 1993, about 8,000 could speak and understand it; today estimates range up to 27,000. Hawaiian is related to the Māori language spoken by around 150,000 New Zealanders and Cook Islanders as well as the Tahitian language which is spoken by another 120,000 people of Tahiti.

Samoan

Samoan is an official territorial language of American Samoa. Samoans make up 90% of the population, and most people are bilingual.

Chamorro

Chamorro is co-official in the Mariana Islands, both in the territory of Guam and in the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. In Guam, the Chamorro people make up about 60% of the population.

Carolinian

Carolinian is also co-official in the Northern Marianas, where only 14% of people speak English at home.

Immigrant languages

Some of the first European languages to be spoken in the U.S. are English, Dutch, German, French, and Spanish.

From the mid-19th century on, the nation had large numbers of immigrants who spoke little or no English, and throughout the country state laws, constitutions, and legislative proceedings appeared in the languages of politically important immigrant groups. There have been bilingual schools and local newspapers in such languages as German, Hungarian, Irish, Italian, Norwegian, Greek, Polish, Swedish, Romanian, Czech, Japanese, Yiddish, Hebrew, Lithuanian, Welsh, Cantonese, Bulgarian, Dutch, Portuguese and others, despite opposing English-only laws that, for example, illegalized church services, telephone conversations, and even conversations in the street or on railway platforms in any language other than English, until the first of these laws was ruled unconstitutional in 1923 (Meyer v. Nebraska).

Currently, Asian languages account for the majority of languages spoken in immigrant communities: Korean, the varieties of Chinese, and various Indian or South Asian languages like Hindi/Urdu, Kannada, Gujarati, Marathi, Punjabi, Bengali, Tamil, Telugu and Malayalam, Arabic, Vietnamese, Tagalog, Persian, and others.

From the 1920s to the early 1950s, a dozen radio stations broadcasted in immigrant languages (notably Yiddish for European Jewish immigrants in the Eastern seaboard), but was curtailed by the Great Depression (1930s), then the US government during World War II and came to an end in the late 1940s, but global radio waves on shortwave radio can broadcast in any language. [citation needed]

Typically, immigrant languages tend to be lost through assimilation within two or three generations, though there are some groups such as the Cajuns (French), Pennsylvania Dutch (German) in a state where large numbers of people were heard to speak it before the 1950s, and the original settlers of the Southwest (Spanish) who have maintained their languages for centuries.

English

English was inherited from British colonization, and it is spoken by the vast majority of the population. It serves as the de facto official language: the language in which government business is carried out. According to the 1990 census, 96% of U.S. residents speak English "well" or "very well." Only 0.8% speak no English at all as compared with 3.6% in 1890. American English is different from British English in terms of spelling (a classic example being the dropped "u" in words such as color/colour), grammar, vocabulary, pronunciation and slang usage. The differences are not usually a barrier to effective communication between an American English and a British English speaker, but there are certainly enough differences to cause occasional misunderstandings, usually surrounding slang or region dialect differences.

Some states, like California, have amended their constitutions to make English the only official language, but in practice, this only means that official government documents must at least be in English, and does not mean that they should be exclusively available only in English. For example, the standard California Class C driver's license examination is available in 32 different languages.[47]

Spanish

Spanish was also inherited from colonization and is sanctioned as official in both New Mexico and Puerto Rico. Spanish is also taught in various regions as a second language, especially in areas with large Hispanic populations such as the Southwestern United States along the border with Mexico, as well as Florida, parts of California, the District of Columbia, Illinois, New Jersey, and New York. In Hispanic communities across the country, bilingual signs in both Spanish and English may be quite common. Furthermore, numerous neighborhoods exist (such as Washington Heights in New York City or Little Havana in Miami) in which entire city blocks will have only Spanish language signs and Spanish-speaking people.

In addition to Spanish-speaking Hispanic populations, younger generations of non-Hispanics in the United States seem to be learning Spanish in larger numbers due to the growing Hispanic population and increasing popularity of Latin American movies and music performed in the Spanish language. A 2007 American Community Survey conducted by the United States Census Bureau, showed that Spanish is the primary language spoken at home by over 34 million people aged 5 or older,[6] making the United States the world's fifth-largest Spanish-speaking community, outnumbered only by Mexico, Spain, Colombia, and Argentina.[48][49]

Spanglish is a code-switching variant of Spanish and English and is spoken in areas with large bilingual populations of Spanish and English speakers, such as along the Mexico – United States border (California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas), Florida, and New York City.

French

French, the fourth most-common language, is spoken mainly by the Louisiana Creole, native French, Cajun, Haitian, and French-Canadian populations. It is widely spoken in Maine, New Hampshire, and in Louisiana.

French is the second de facto language in the state of Louisiana (where the French dialect of Cajun predominates). The largest French-speaking communities in the United States reside in Northeast Maine; Hollywood and Miami, Florida; New York City; certain areas of rural Louisiana; and small minorities in Vermont and New Hampshire. Many of the New England communities are connected to the dialect found across the border in Quebec or New Brunswick. More than 13 million Americans possess primary French heritage, but only 1.6 million speak that language at home.

Arabic

Arabic is spoken by immigrants from the Middle East as well as many Muslim Americans. The highest concentrations of native Arabic speakers reside in heavily urban areas like Chicago, New York City, and Los Angeles. Detroit and the surrounding areas of Michigan boast a significant Arabic-speaking population including many Arab Christians of Lebanese, Syrian, and Palestinian descent. Arabic is used for religious purposes by Muslim Americans and by some Arab Christians (notably Catholics of the Melkite and Maronite Churches as well as Rum Orthodox, i.e. Antiochian Orthodox Christians). A significant number of educated Arab professionals who immigrate often already know English quite well, as it is widely used in the Middle East. Lebanese immigrants also have a broader understanding of French as do many Arabic-speaking immigrants from North Africa.

Chinese

Chinese, mostly of the Cantonese variety, is the third most-spoken language in the United States, almost completely spoken within Chinese American populations and by immigrants or the descendants of immigrants, especially in California.[50] Many young Americans not of Chinese descent have become interested in learning the language, specifically Standard Mandarin, the official spoken language in the People's Republic of China. Over 2 million Americans speak some variety of Chinese, with the Mandarin variety becoming increasingly more prevalent due to the opening up of the PRC.[50]

In New York City at least, although Mandarin is spoken as a native language among only 10% of Chinese speakers, it is used as a secondary dialect among the greatest number of them and is on its way to replace Cantonese as their lingua franca.[51]

Dutch

There has been a Dutch presence in America since 1602, when the government of the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands chartered the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, or VOC) with the mission of exploring for a passage to the Indies and claiming any uncharted territories for the Dutch republic. In 1664, English troops under the command of the Duke of York (later James II of England) attacked the New Netherland colony. Being greatly outnumbered, director general Peter Stuyvesant surrendered New Amsterdam, with Fort Orange following soon. New Amsterdam was renamed New York, Fort Orange was renamed Fort Albany.

Dutch was still spoken in many parts of New York at the time of the Revolution. For example, Alexander Hamilton's wife Eliza Hamilton attended a Dutch-language church during their marriage.

Martin Van Buren, the first President born in the United States following its independence, spoke Dutch as his native language, making him the only President whose first language was not English.

In a 1990 demographic consensus, 3% of surveyed citizens claimed descent from Dutch settlers. Modern estimates place the Dutch American population at 5 million, lagging just a bit behind Scottish Americans and Swedish Americans.

Notable Dutch Americans include the Roosevelts (Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and Eleanor Roosevelt) Marlon Brando, Thomas Alva Edison, Martin Van Buren and the Vanderbilts. The Roosevelts are direct descendants of Dutch settlers of the New Netherlands colony in the 17th century.

Only 150,000 people in the United States still speak the Dutch language at home today,[52] concentrated mainly in Michigan (i.e. the city of Holland), Tennessee, Miami, Houston, and Chicago. The Dutch language is studied as a novelty in mostly Dutch communities of Pella, Iowa, and San Joaquin County, California has a renowned Dutch and Frisian settlement history since the 1840s.

A vernacular dialect of Dutch, known as Jersey Dutch was spoken by a significant number of people in the New Jersey area between the start of the 17th century to the mid-20th century. With the beginning of the 20th century, usage of the language became restricted to internal family circles, with an ever-growing number of people abandoning the language in favor of English. It suffered gradual decline throughout the 20th century, and it ultimately dissipated from casual usage.

Finnish

The first Finnish settlers in America were amongst the settlers who came from Sweden and Finland to New Sweden colony. Most colonists were Finnish. However, the Finnish language was not preserved as well among subsequent generations as Swedish.

Shortly after the Civil War, many Finnish citizens immigrated to the United States, mainly in rural areas of the Midwest (and more specifically in Michigan's Upper Peninsula). Hancock, Michigan, as of 2005, still incorporates bi-lingual street signs written in both English and Finnish.[53] Americans of Finnish origin yield at 800,000 individuals, though only 39,770 speak the language at home.[54] There is a distinctive dialect of English to be found in the Upper Peninsula, known as Yooper. Yuper often has a Finnish cadence and uses Finnish sentence structure with modified English, German, Swedish, Norwegian, and Finnish vocabulary. Notable Finnish Americans include Gus Hall, U.S. Communist Party leader, Renny Harlin, film director, and the Canadian-born actress Pamela Anderson. Another Finnish community in the United States is found in Lake Worth, Florida, north of Miami.

German

See also: Hutterite German, Texas German, Pennsylvania Dutchified English, Plautdietsch.

German was a widely spoken language in some of the colonies, especially Pennsylvania, where a number of German-speaking religious minorities settled to escape persecution in Europe. Dutch, Swedish, and Scottish Gaelic all became less common than German after the American Revolution. Another wave of settlement occurred when Germans fleeing the failure of 19th Century German revolutions emigrated to the United States. Large numbers of Germans settled throughout the U.S., especially in the cities. Neighborhoods in many cities were German-speaking. German farmers took up farming around the country, including the Texas Hill Country, at this time. German was widely spoken until the United States entered World War I. Numerous local German language newspapers and periodicals existed.

In the early twentieth century, German was the most widely studied foreign language in the United States, and prior to World War I, more than 6% [citation needed] of American school-children received their primary education exclusively in German, though some of these Germans came from areas outside of Germany proper. Currently, more than 49 million Americans claim German ancestry, the largest self-described ethnic group in the U.S., but less than 4% of them speak a language other than English at home, according to the 2005 American Community Survey.[55] The Amish speak a dialect of German known as Pennsylvania German. In addition to Pennsylvania, German was widely spoken in the Midwest until the late 1950s. One reason for this decline of German language was the perception during both World Wars that speaking the language of the enemy was unpatriotic; foreign language instruction was banned in places during the First World War. Another was the demise of traditional agriculture[citation needed]. The last wave of German immigration followed World War II, as post-war Germany suffered economic problems, and ethnic Germans were uprooted from their homes in Eastern Europe. Unlike earlier waves, they were more concentrated in cities, and integrated quickly. Since the Wirtschaftswunder, German immigration to the U.S. has all but ended. Most German Americans are completely integrated into the mainstream American society and the language is being taught less and less in schools because of diminishing demand. However, in recent years, immigration of highly skilled Germans to the US has picked up to some degree.

There is a myth (known as the Muhlenberg Vote) that German was to be the official language of the U.S., but this is inaccurate and based on a failed early attempt to have government documents translated into German.[56] The myth also extends to German being the second official language of Pennsylvania; however, Pennsylvania has no official language. Although more than 49 million Americans claim they have German ancestors, only 1.38 million Americans speak German at home.

Russian

The Russian language is frequently spoken in areas of Alaska, Los Angeles, Seattle, Spokane, Miami, San Francisco, New York City, Philadelphia, and Chicago. The Russian-American Company used to own Alaska Territory until selling it after the Crimean War. Russian had always been limited, especially after the assassination of the Romanov dynasty of tsars. Starting in the 1970s and continuing until the mid 1990s, many people from the Soviet Union and later its constituent republics such as Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, and Uzbekistan have immigrated to the United States, increasing the language's usage in America. The largest Russian-speaking neighborhoods in the United States are found in Queens, Brooklyn, and Staten Island in New York City (specifically the Brighton Beach area of Brooklyn), parts of Los Angeles, particularly West Los Angeles and West Hollywood, parts of Philadelphia, particularly the Far Northeast and, parts of Miami like Sunny Isles Beach.

Hebrew

Modern Hebrew is used by some immigrants from Israel and Eastern Europe. Liturgical Hebrew is used as a religious or liturgical language by many of the United States' approximately 7 million Jews.

Ilocano

Like the Tagalogs, the Ilocanos are an Austronesian stock which came from the Philippines. They were the first Filipinos to migrate en masse to the United States. They first entered the State of Hawai'i and worked there in the vast plantations.

As they did in the Philippine provinces of Northern Luzon and Mindanao, they quickly gained importance in the areas where they settled. Thus, the state of Hawai'i became no less different from the Philippines in terms of percentage of Ilocano speakers.

Like Tagalog, Ilocano is also being taught in universities where most of the Filipinos reside.

Irish

Up to 37 million Americans have Irish ancestry, many of whose ancestors would have spoken Irish. As of 2009[update] it is the 66th most spoken language in the USA, with an estimated 25,000 speakers.[citation needed]

Italian

The Italian language and its various dialects has been widely spoken in the United States for more than one hundred years, primarily due to large-scale immigration from the late 19th century to the mid 20th C.

In addition to Standard Italian learned by most people today, there has been a strong representation of the dialects and languages of Southern Italy amongst the immigrant population (Sicilian and Neapolitan in particular).Today, though 15,638,348 American citizens report themselves as Italian Americans, only 1,008,370 of these report speaking the Italian language at home (0.384% of the population).

Khmer (Cambodian)

Between 1981-1985 about 150,000 Cambodians resettled in the United States.[57] Before 1975 very few Cambodians came to the United States. Those who did were children of upper class families sent abroad to attend school. After the fall of Phnom Penh to the communist Khmer Rouge in 1975, some Cambodians managed to escape. In 2000 the Census Bureau reported that there were approximately 172,000 Cambodians living in the United States, making up about 1.8 percent of the Asian population.[58] The states with the most Khmer speakers are California, Massachusetts, Washington, Pennsylvania and Texas.

Polish

The Polish language is very common in the Chicago metropolitan area. Chicago's largest white ethnic groups are those of Polish descent. The Polish people and the Polish language in Chicago have been very prevalent in the early years of the city, as well as the progression and economical and social development of Chicago. Poles in Chicago make up the largest ethnically Polish population of any city outside of Poland (second only to Warsaw) [citation needed] making it one of the most important centers of Polonia and the Polish language in the United States, a fact that the city celebrates every Labor Day weekend at the Taste of Polonia Festival in Jefferson Park.[59]

Portuguese

The first Portuguese speakers in America were Jews who had fled the Inquisition; they founded the first Jewish communities, two of which stiil exist: Congregation Shearith Israel in New York and Congregation Mikveh Israel in Philadelphia. However, by the end of the 18th century the use of Portuguese had been replaced by English. In the late 19th century, many Portuguese, mainly Azorean and Madeira, immigrated to the United States, establishing in cities like Providence, Rhode Island, New Bedford, Massachusetts, and Santa Cruz, California. Many of them also moved to Hawaii during its independence. In the mid-late 20th century there was another surge of Portuguese immigration in America, mainly in the Northeast (New Jersey, New York, Connecticut, Massachusetts). Many Portuguese Americans may include descendants of Portuguese settlers born in Africa (like Angola, Cape Verde, and Mozambique) and Asia (mostly Macau). There were around 1 million Portuguese Americans in the United States by the year 2000. Portuguese (European Portuguese) has been spoken in the United States by small communities of immigrants, mainly in the metropolitan New York City area, like Newark, New Jersey. The Portuguese language is also spoken widely by Brazilian immigrants, established mainly in Miami, New York City and Boston. (Brazilian Portuguese)

Scottish Gaelic

In the 17th and 18th centuries, tens of thousands of Scots from Scotland, and Scots-Irish from the north of Ireland arrived in the American colonies. Today, an estimated 15 million Americans are of Scottish ancestry. The province of Nova Scotia, Canada was the main concentration of Scottish Gaelic speakers in North America (Nova Scotia is Latin for New Scotland). According to the 2000 census, 1,119 people speak Scottish Gaelic at home.[60]

Swedish

There has been a Swedish presence in America since the New Sweden colony came into existence in March 1638.

Widespread diaspora of Swedish immigration did not occur until the latter half of the 19th century, bringing in a total of a million Swedes. No other country had a higher percentage of its people leave for the United States except Ireland and Norway. At the beginning of the 20th century, Minnesota had the highest ethnic Swedish population in the world after the city of Stockholm.

3.7% of US residents claim descent from Scandinavian ancestors, amounting to roughly 11-12 million people. According to SIL's Ethnologue, over half a million ethnic Swedes still speak the language, though according to the 2000 census only 67,655 speak it at home.[61] Cultural assimilation has contributed to the gradual and steady decline of the language in the US. After the independence of the US from the Kingdom of Great Britain, the government encouraged colonists to adopt the English language as a common medium of communication, and in some cases, imposed it upon them. Subsequent generations of Swedish Americans received education in English and spoke it as their first language. Lutheran churches scattered across the Midwest started abandoning Swedish in favor of English as their language of worship. Swedish newspapers and publications alike slowly faded away.

There are sizable Swedish communities in Minnesota, Ohio, Maryland, Philadelphia and Delaware, along with small isolated pockets in Pennsylvania, San Francisco, Fort Lauderdale, and New York. Chicago once contained a large Swedish enclave called Andersonville on the city's north side.

John Morton, the person who cast the decisive vote leading to Pennsylvania's support for the United States Declaration of Independence, was a Finland-Swede (Note that Finland was still a part of Sweden in the 18th century).

Tagalog

Tagalog speakers were already present in the United States as early as the late sixteenth century as sailors contracted by the Spanish colonial government. In the eighteenth century, they established settlements in Louisiana, such as Saint Malo.

After the American annexation of the Philippines, the number of Tagalog speakers steadily increased, as Filipinos began to migrate as students or contract laborers. Their numbers, however, decreased upon Philippine independence, as many Filipinos were repatriated.

Today, Tagalog, together with its standardized form Filipino, is spoken by over a million Filipino Americans, and is promoted by Filipino American civic organizations and Philippine consulates.

Taglish, a form of code-switching between Tagalog and English, is also spoken by a number of Filipino Americans.

As the Filipinos became the second fastest growing Asian population in the United States, Tagalog easily became the second most spoken Asian language in the continent. Today, Tagalog is being majored in some universities where a significant number of Filipinos exist. Some of these schools include the University of Hawaii at Manoa and the University of California.

As Tagalog is the basis of Filipino, most of all the Filipinos living in the United States are proficient in Tagalog.

Welsh

Up to two million Americans are thought to have Welsh ancestry. However, there is very little Welsh being used commonly in the USA. According to the 2000 U.S. Census, 2,649 people speak Welsh at home[62] Some place names, such as Bryn Mawr in Chicago and Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania (English: Big Hill) are Welsh. Several towns in Pennsylvania, mostly in the Welsh Tract, have Welsh namesakes, including Uwchlan, Bala Cynwyd, Gwynedd, and Tredyffrin.

Yiddish

Yiddish has a much longer history in the United States than Hebrew; it has been present since at least the late 19th century and continues to have roughly 179,000 speakers as of the 2000 census. Though they came from varying geographic backgrounds and nuanced approaches to worship, immigrant Jews of Eastern Europe and Russia were often united under a common understanding of the Yiddish language once they settled in America, and at one point dozens of publications were available in most East Coast cities. Though it has declined by quite a bit since the end of WWII, it has by no means disappeared. Many Israeli immigrants and expatriates have at least some understanding of the language in addition to Hebrew, and many of the descendants of the great migration of Ashkenazi Jews of the past century pepper their mostly English vocabulary with some loan words. Furthermore, it is definitely a lingua franca alive and well among Orthodox Jewry, particularly in Los Angeles, Miami and New York.[63] [64]

New American languages, dialects, and creoles

Several languages have developed on American soil, including creoles and sign languages.

African American Vernacular English

African American Vernacular English (AAVE), also known as Ebonics, is a variety of English spoken by many African Americans, in both rural and urban areas. Not all African Americans speak AAVE and many European Americans do. Indeed, it is generally accepted that Southern American English is part of the same continuum as AAVE.

There is considerable debate among non-linguists as to whether the word "dialect" is appropriate to describe it. However, there is general agreement among linguists and many African Americans that AAVE is part of a historical continuum between creoles such as Gullah and the language brought by English colonists.

Some educators view AAVE as exerting a negative influence on the learning of Proper and Standard English, as numerous AAVE rules differ from the rules of Standard English. Other educators, however, propose that Standard English should be taught as a "second dialect" in areas where AAVE is a strong part of local tradition.

Chinuk Wawa or Chinook Jargon

Chinuk Wawa (or Chinook Jargon) is a Creole language of 700-800 words of French, English, Cree and other Native origins. It is the old trade language of the Pacific Northwest. It was used extensively among both European and Native peoples of the old Oregon Territory, even used in place of English at home for many families. It is estimated that around 250,000 people spoke it at its peak and it was last used extensively in Seattle. The language never quite died with 'Cascadian' enthusiasts attempting to promote its usage as a street language throughout the Pacific Northwest.

Gullah

Gullah, an English-African creole language spoken on the Sea Islands of South Carolina and Georgia, retains strong influences of West African languages. The language is sometimes referred to as "Geechee".

Hawaiian Creole

Hawaiian Pidgin, more accurately known as Hawaiian Creoles, is commonly used by locals and is considered an unofficial language of the state. This not to be confused with Hawaiian English which is standard American English with Hawaiian words.

Outer Banks languages

In the islands of the Outer Banks off North Carolina, several unique English dialects have developed. This is evident on Harkers Island and Ocracoke Island.

Pennsylvania Dutch

Pennsylvania Dutch is a language spoken mainly in Pennsylvania. It evolved from the German dialect brought over to America by the Pennsylvania Dutch people (the Amish) before 1800. It is now mostly mutually unintelligible from Standard German.

Texas Silesian

Texas Silesian (Silesian: teksasko gwara) is a language used by Texas Silesians in American settlements from 1852 to the present.

Tangier Islander

Another dialectal isolate is Tangier Island, Virginia located in the Chesapeake bay. The dialect is partially build on Old Colonial English and the Middle-Atlantic American dialect, but contained some words from the Celtic-based Cornish language of Cornwall, England. [citation needed]

Chicano English

A mixture of the Spanish and American English languages spoken by many Hispanics in urban areas and predominantly Latino communities. See also Chicano English and New Mexican Spanish for Mexican-American dialects of the Southwest.

Sign languages

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2007) |

Martha's Vineyard Sign Language

Martha's Vineyard Sign Language is now extinct. Along with French Sign Language, it was one of two main contributors to American Sign Language.

American Sign Language

American Sign Language (ASL) is the native language of between 500,000 and 2 million Deaf people in America.[citation needed] Unlike Signed English, ASL is a natural language in its own right, not a manual representation of English.[65]

Black American Sign Language

Black American Sign Language developed in segregated schools in the south. Much like AAVE and standard English, it differs in vocabulary and grammatical structure from ASL.[65] Black American Sign Language is not grammatically incorrect. It is considered a dialect of American Sign Language, complete with its own rules for grammar, syntax and vocabulary.

Hawaii Pidgin Sign Language

Hawaii Pidgin Sign Language (named after Hawaiian Pidgin English, but not itself a pidgin) is moribund.

See also

- American English

- Bilingual education

- Culture of the United States

- Japanese language education in the United States

- Language Spoken at Home (U.S. Census)

- List of Presidents of the United States who knew a foreign language

- Muhlenberg legend

Notes

- ^ United States, CIA World Factbook.

- ^ Language learning trends in the United States. Retrieved on 2008-03-19

- ^ Summary Tables on Language Use and English Ability: 2000 (PHC-T-20), U.S. Census Bureau, retrieved 2008-02-22

- ^ U.S. Senate Roll Call Votes 109th Congress - 2nd Session, United States Senate, retrieved 2008-02-22

- ^ "Senate Amendment 1151 to Senate Bill 1348, Immigration Act of 2007". project Vote Smart. Retrieved 2008-07-04..

- ^ a b "Selected Social Characteristics in the United States: 2007". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-10-09.

- ^ English Usage among Hispanics in the United States

- ^ Ancestry: 2000, U.S. Census Bureau, 2000

- ^ a b Language Use and English-Speaking Ability: 2000 (PDF), U.S. Census Brueau, 2003, retrieved 2008-02-22

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ EAC Issues Glossaries of Election Terms in Five Asian Languages Translations to Make Voting More Accessible to a Majority of Asian American Citizens. Election Assistance Commission. 20 June 2008.

- ^ Grimes 2000

- ^ MLA Language Map Data Center, Modern Language Association, retrieved 2008-02-22

- ^ Section 509- English as Official Language of State - Constitution of Alabama 1901, State of Alabama, retrieved 2008-10-20

- ^ Article 28, Section 2, Arizona Constitution, State of Arizona, retrieved 2008-10-20

- ^ http://www.languagepolicy.net/archives/ark.htm

- ^ Article 3, Section 6, Subsection B, California State Constitution, State of California, retrieved 2008-10-21

- ^ Article 2, Section 30a, Constitution of the State of Colorado, State of Colorado, retrieved 2008-10-21

- ^ Article 2, Section 9, Constitution of the State of Florida, State of Florida, retrieved 2008-10-21

- ^ OFFICIAL GEORGIA CODE : SECTION 50-3-100: OFFICIAL LANGUAGE (1996), proenglish.org, retrieved 2009-12-22 [dead link]

- ^ http://legislature.idaho.gov/idstat/Title73/T73CH1SECT73-121.htm

- ^ 5 ILCS 460/20

- ^ www.in.gov/legislative/ic/code/title1/ar2/ch10.pdf

- ^ Iowa Code Section 1.18, State of Iowa, retrieved 2009-02-02

- ^ House Bill No. 2140 (PDF), Kansas State Legislature, retrieved 2009-02-02

- ^ Brooks, Pc, Jr (1970), "Kentucky Revised Statutes" (PDF), Journal of the Kentucky Dental Association, 22 (3), Kentucky Legislative Research Commission: 25–6, ISSN 0023-0162, PMID 5270729, retrieved 2009-04-04

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Section 3-3-31, Mississippi Code of 1972, Lexis-Nexis Publishing, retrieved 2009-04-04

- ^ Article 1, Section 34, Constitution of Missouri, Missouri General Assembly, retrieved 2009-04-05

- ^ Section 1-1-510, Montana Code, Montana Office of Public Instruction, retrieved 2009-04-05

- ^ http://nebraskalegislature.gov/laws/articles.php?article=I-27

- ^ http://www.gencourt.state.nh.us/rsa/html/NHTOC/NHTOC-I-3-C.htm

- ^ http://www.ncga.state.nc.us/EnactedLegislation/Statutes/HTML/ByChapter/Chapter_145.html

- ^ http://www.nd.gov/content.htm?parentCatID=75&id=State%20Language

- ^ Oklahoma Voters Approve State Official English Law

- ^ http://www.scstatehouse.gov/code/t01c001.htm

- ^ http://legis.state.sd.us/statutes/DisplayStatute.aspx?Type=Statute&Statute=1-27-20

- ^ http://www.languagepolicy.net/archives/tenn.htm

- ^ http://www.rules.utah.gov/publicat/code/r765/r765-136.htm

- ^ leg1.state.va.us/cgi-bin/legp504.exe?961+ful+SB582S1+pdf

- ^ http://legisweb.state.wy.us/statutes/statutes.aspx?file=titles/Title8/T8CH6.htm

- ^ New Mexico has a non-binding "English Plus" resolution, officially endorsing multilingualism.

- ^ California Department of Motor Vehicles Website (actual website blocked by Wikipedia)

- ^ Dutch Colonies, National Park Service, retrieved 2008-02-22

- ^ America Votes 2006: Key Ballot Issues, CNN, retrieved 2008-02-22

- ^ 2008 ARIZONA VOTER EMPOWERMENT CARD, American Civil Liberties Union.

- ^ Alice N. Nash; Christoph Strobel (2006), "Daily life of Native Americans from post-Columbian through nineteenth-century America", The Greenwood Press "Daily life through history" series, Greenwood Publishing Group, p. IX, ISBN 9780313335150

- ^ Ben Frey, A Look at the Cherokee Language, North Carolina Museum of History, from Tar Heel Junior Historian 45:1 (fall 2005).

- ^ Driver License and Identification (ID) Card Information, California Department of Motor Vehicles.

- ^ Instituto Cervantes (Enciclopedia del español en Estados Unidos)

- ^ "Más 'speak spanish' que en España". Retrieved 2007-10-06.

- ^ a b Lai, H. Mark (2004), Becoming Chinese American: A History of Communities and Institutions, AltaMira Press, ISBN 0759104581

- ^ García, Ofelia (2002), The Multilingual Apple: Languages in New York City, Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 311017281X

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Dutch, Modern Language Association, citing census 2000

- ^ Street names are in english and in finnish, The Selonen Family Network, archived from the original on September 24, 2006, retrieved 2008-02-22[unreliable source?]

- ^ Finnish, Modern Language Association, citing census 2000, retrieved 2008-02-22

- ^ Selected Population Profile in the United States: German, 2005 American Community Survey, U.S. Census Bureau.

- ^ Did Hebrew almost become the official U.S. language?, January 21, 1994, retrieved 2008-02-22

- ^ Cambodians in the United States, [http://www.apiahf.org/ apiahf.org.

- ^ Population Group: Cambodian alone or in any combination, S0201. Selected Population Profile in the United States , U.S. Census Bureau.

- ^ America the diverse: Chicago's Polish neighborhoods, usaweekend.com, May 15, 2005, retrieved 2008-07-04 [dead link]

- ^ Scottic Gaelic, Modern Language Association, citing Census 2000, retrieved 2008-02-22

- ^ Swedish, Modern Language Association, citing census 2000, retrieved 2008-02-22

- ^ Welsh, Modern Language Association, citing Census 2000, retrieved 2008-02-22

- ^ Sewell Chan (October 17, 2007), A Yiddish Revival, With New York Leading the Way, The New York Times, retrieved 2008-08-15

+ Patricia Ward Biederman (July 7, 2005), Yiddish Program Aims to Get Beyond Schmoozing, Los Angeles Times, retrieved 2008-08-15

+ Yiddishkayt Los Angeles, yiddishkaytla.org, retrieved 2008-08-15 - ^ Julie Levin, Club dedicated to keeping Yiddish alive, April 11, 2010, The Miami Herald.

- ^ a b AMERICAN SIGN LANGUAGE: a language of USA, ethnologue.com, retrieved 2008-09-29

Bibliography

- Campbell, Lyle. (1997). American Indian languages: The historical linguistics of Native America. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Campbell, Lyle; & Mithun, Marianne (Eds.). (1979). The languages of native America: Historical and comparative assessment. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Grimes, Barbara F. (Ed.). (2000). Ethnologue: Languages of the world, (14th ed.). Dallas, TX: SIL International. ISBN 1-55671-106-9. Online edition: http://www.ethnologue.com/, accessed on December 7, 2004.

- Mithun, Marianne. (1999). The languages of native North America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Zededa, Ofelia; Hill, Jane H. (1991). The condition of Native American Languages in the United States. In R. H. Robins & E. M. Uhlenbeck (Eds.), Endangered languages (pp. 135–155). Oxford: Berg.

External links

- Bilingualism in the United States

- Detailed List of Languages Spoken at Home for the Population 5 Years and Over by State: U.S. Census 2000

- Foreign Languages in the U.S. About foreign languages and language learning in the United States

- How many indigenous American languages are spoken in the United States? By how many speakers?

- Native Languages of the Americas

- Ethnologue report for USA

- Linguistic map of the United States of America