Atlanta: Difference between revisions

change link |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

| settlement_type = [[State capital|State Capital]] |

| settlement_type = [[State capital|State Capital]] |

||

| nickname = Hotlanta,<ref>[http://nl.newsbank.com/nl-search/we/Archives?p_product=AT&p_theme=at&p_action=search&p_maxdocs=200&p_topdoc=1&p_text_direct-0=1215879443CB5810&p_field_direct-0=document_id&p_perpage=10&p_sort=YMD_date:D&s_trackval=GooglePM "Love it or loathe it, the city’s nickname is accurate for the summer", ‘‘Atlanta Journal-Constitution’’, June 16, 2008]</ref> ATL,<ref>[http://nl.newsbank.com/nl-search/we/Archives?p_product=AT&p_theme=at&p_action=search&p_maxdocs=200&p_topdoc=1&p_text_direct-0=111029FE6BC70418&p_field_direct-0=document_id&p_perpage=10&p_sort=YMD_date:D&s_trackval=GooglePM “The service, dubbed the Atlanta Tourist Loop as a play on the city’s "ATL" nickname, will start April 29 downtown.” “Buses to link tourist favorites” ‘‘The Atlanta Journal-Constitution’’]</ref> The City in a Forest,<ref>[http://www.wsbtv.com/news/news/atlanta-may-no-longer-be-the-city-in-a-forest/nDLGr/ "Atlanta May No Longer Be the City in a Forest", ‘‘WSB-TV’’]</ref> The A,<ref>{{cite news|url=http://clatl.com/atlanta/because-were-the-only-city-easily-identified-by-just-one-letter/Content?oid=4291994|title=Because we're the only city easily identified by just one letter|work=[[Creative Loafing]]|date=2011-11-23|accessdate=2012-10-07}}</ref> |

| nickname = Hotlanta,<ref>[http://nl.newsbank.com/nl-search/we/Archives?p_product=AT&p_theme=at&p_action=search&p_maxdocs=200&p_topdoc=1&p_text_direct-0=1215879443CB5810&p_field_direct-0=document_id&p_perpage=10&p_sort=YMD_date:D&s_trackval=GooglePM "Love it or loathe it, the city’s nickname is accurate for the summer", ‘‘Atlanta Journal-Constitution’’, June 16, 2008]</ref> ATL,<ref>[http://nl.newsbank.com/nl-search/we/Archives?p_product=AT&p_theme=at&p_action=search&p_maxdocs=200&p_topdoc=1&p_text_direct-0=111029FE6BC70418&p_field_direct-0=document_id&p_perpage=10&p_sort=YMD_date:D&s_trackval=GooglePM “The service, dubbed the Atlanta Tourist Loop as a play on the city’s "ATL" nickname, will start April 29 downtown.” “Buses to link tourist favorites” ‘‘The Atlanta Journal-Constitution’’]</ref> The City in a Forest,<ref>[http://www.wsbtv.com/news/news/atlanta-may-no-longer-be-the-city-in-a-forest/nDLGr/ "Atlanta May No Longer Be the City in a Forest", ‘‘WSB-TV’’]</ref> The A,<ref>{{cite news|url=http://clatl.com/atlanta/because-were-the-only-city-easily-identified-by-just-one-letter/Content?oid=4291994|title=Because we're the only city easily identified by just one letter|work=[[Creative Loafing]]|date=2011-11-23|accessdate=2012-10-07}}</ref> |

||

The Gate City.<ref name=sunnysouth1891>{{cite news|url=http://atlnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu/atlnewspapers/view?docId=news/ssw1891/ssw1891-0021.xml|title=Our Quiz Column|work=Sunny South|page=5}}</ref> See also [[Nicknames of Atlanta|article]] |

The Gate City.<ref name=sunnysouth1891>{{cite news|url=http://atlnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu/atlnewspapers/view?docId=news/ssw1891/ssw1891-0021.xml|title=Our Quiz Column|work=Sunny South|page=5}}</ref> Hollywood of the South<ref>http://atlantablackstar.com/2012/07/23/atlanta-becoming-the-hollywood-of-the-south/</ref> See also [[Nicknames of Atlanta|article]] |

||

| motto = ''Resurgens'' (Latin for ''rising again'') |

| motto = ''Resurgens'' (Latin for ''rising again'') |

||

| image_skyline = Atlanta Montage 2.jpg |

| image_skyline = Atlanta Montage 2.jpg |

||

Revision as of 01:26, 23 May 2013

Atlanta | |

|---|---|

| City of Atlanta | |

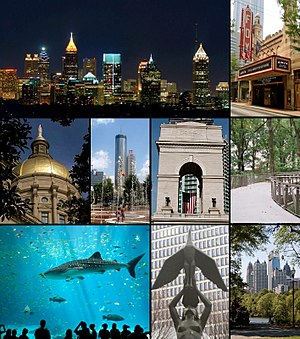

From top to bottom left to right: Atlanta skyline seen from Buckhead, the Fox Theatre, the Georgia State Capitol, Centennial Olympic Park, Millennium Gate, the Canopy Walk, the Georgia Aquarium, The Phoenix statue, and the Midtown skyline | |

| Nickname(s): | |

| Motto: Resurgens (Latin for rising again) | |

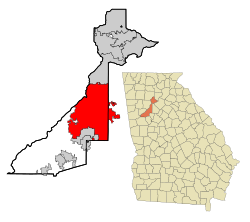

City highlighted in Fulton County, location of Fulton County in the state of Georgia | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Fulton and DeKalb |

| Terminus | 1837 |

| Marthasville | 1843 |

| City of Atlanta | December 29, 1845 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Kasim Reed |

| • Body | Atlanta City Council |

| Area | |

| • State Capital | 132.4 sq mi (343.0 km2) |

| • Land | 131.8 sq mi (341.2 km2) |

| • Water | 0.6 sq mi (1.8 km2) |

| • Urban | 1,963 sq mi (5,080 km2) |

| • Metro | 8,376 sq mi (21,690 km2) |

| Elevation | 738 to 1,050 ft (225 to 320 m) |

| Population (est. 2012) | |

| • State Capital | 432,427 |

| • Density | 3,188/sq mi (1,230.9/km2) |

| • Urban | 4,975,300 |

| • Metro | 5,457,831 (9th) |

| • Metro density | 630/sq mi (243/km2) |

| • CSA | 6,092,295 (11th) |

| • Demonym | Atlantan[7] |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code(s) | 30060, 30301-30322, 30324-30334, 30336-30350, 30353 |

| Area code(s) | 404, 470, 678, 770 |

| FIPS code | 13-04000Template:GR |

| GNIS feature ID | 0351615Template:GR |

| Website | www |

Atlanta (/[invalid input: 'icon']ətˈlæntə/, stressed /ætˈlæntə/, locally /ætˈlænə/) is the capital of and the most populous city in the U.S. state of Georgia, with an estimated 2011 population of 432,427.[8] Atlanta is the cultural and economic center of the Atlanta metropolitan area, home to 5,457,831 people and the ninth largest metropolitan area in the United States.[9] Atlanta is the county seat of Fulton County, and a small portion of the city extends eastward into DeKalb County.

Atlanta was established in 1837 at the intersection of two railroad lines, and the city rose from the ashes of the Civil War to become a national center of commerce. In the decades following the Civil Rights Movement, during which the city earned a reputation as "too busy to hate" for the progressive views of its citizens and leaders,[10] Atlanta attained international prominence. Atlanta is the primary transportation hub of the Southeastern United States, via highway, railroad, and air, with Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport being the world's busiest airport since 1998.[11][12][13][14] Atlanta is considered an "alpha(-) world city,"[15] and, with a gross domestic product of US$270 billion, Atlanta's economy ranks 15th among world cities and sixth in the nation.[16] Although Atlanta’s economy is considered diverse, dominant sectors include logistics, professional and business services, media operations, government administration, and higher education.[17] Topographically, Atlanta is marked by rolling hills and dense tree coverage.[18] Revitalization of Atlanta's neighborhoods, initially spurred by the 1996 Olympics, has intensified in the 21st century, altering the city's demographics, politics, and culture.[19]

History

Prior to the arrival of European settlers in north Georgia, Creek and Cherokee Indians inhabited the area.[20] Standing Peachtree, a Creek village located where Peachtree Creek flows into the Chattahoochee River, was the closest Indian settlement to what is now Atlanta.[21] As part of the systematic removal of Native Americans from northern Georgia from 1802 to 1825,[22] the Creek ceded the area in 1821,[23] and white settlers arrived the following year.[24]

In 1836, the Georgia General Assembly voted to build the Western and Atlantic Railroad in order to provide a link between the port of Savannah and the Midwest.[25] The initial route was to run southward from Chattanooga to a terminus east of the Chattahoochee River, which would then be linked to Savannah. After engineers surveyed various possible locations for the terminus, the "zero milepost" was driven into the ground in what is now Five Points. A year later, the area around the milepost had developed into a settlement, first known as “Terminus,” and later as “Thrasherville” after a local merchant who built homes and a general store in the area.[26] By 1842, the town had six buildings and 30 residents, and was renamed "Marthasville" to honor the Governor’s daughter.[27] J. Edgar Thomson, Chief Engineer of the Georgia Railroad, suggested the town be renamed "Atlantica-Pacifica,” which was shortened to "Atlanta."[27] The residents approved, and the town was incorporated as Atlanta on December 29, 1847.[28]

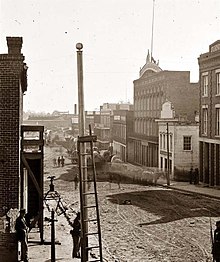

By 1860, Atlanta’s population had grown to 9,554.[29][30] During the Civil War, the nexus of multiple railroads in Atlanta made the city a hub for the distribution of military supplies. In 1864, following the capture of Chattanooga, the Union Army moved southward and began its invasion of north Georgia. The region surrounding Atlanta was the location of several major army battles, culminating with the Battle of Atlanta and a four-month-long siege of the city by the Union Army under the command of General William Tecumseh Sherman. On September 1, 1864, Confederate General John Bell Hood made the decision to retreat from Atlanta, ordering all public buildings and possible assets to the Union Army destroyed. On the next day, Mayor James Calhoun surrendered Atlanta to the Union Army, and on September 7, General Sherman ordered the city’s civilian population to evacuate. On November 11, 1864, in preparation of the Union Army’s march to Savannah, Sherman ordered Atlanta to be burned to the ground, sparing only the city’s churches and hospitals.[31]

After the Civil War ended in 1865, Atlanta was gradually rebuilt. Due to the city’s superior rail transportation network, the state capital was moved to Atlanta from Milledgeville in 1868.[32] In the 1880 Census, Atlanta surpassed Savannah as Georgia’s largest city. Beginning in the 1880s, Henry W. Grady, the editor of the ‘‘Atlanta Constitution’’ newspaper, promoted Atlanta to potential investors as a city of the "New South" that would be based upon a modern economy and less reliant on agriculture. By 1885, the founding of the Georgia School of Technology (now Georgia Tech) and the city’s black colleges had established the city as a center for higher education. In 1895, Atlanta hosted the Cotton States and International Exposition, which attracted nearly 800,000 attendees and successfully promoted the New South’s development to the world.[33]

During the first decades of the 20th century, Atlanta experienced a period of unprecedented growth. In three decades’ time, Atlanta’s population tripled as the city limits expanded to include nearby streetcar suburbs; the city’s skyline emerged with the construction of the Equitable, Flatiron, Empire, and Candler buildings; and Sweet Auburn emerged as a center of black commerce. However, the period was also marked by strife and tragedy. Increased racial tensions led to the Atlanta Race Riot of 1906, which left at least 27 people dead and over 70 injured.[34] In 1915, Leo Frank, a Jewish-American factory superintendent, convicted of murder, was hanged by a lynch mob, drawing attention to antisemitism in the United States.[35] On May 21, 1917, the Great Atlanta Fire destroyed 1,938 buildings in what is now the Old Fourth Ward, resulting in one fatality and the displacement of 10,000 people.

On December 15, 1939, Atlanta hosted the film premiere of Gone with the Wind, the epic film based on the best-selling novel by Atlanta’s Margaret Mitchell. The film's legendary producer, David O. Selznick, as well as the film's stars Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh, and Olivia de Havilland attended the gala event at Loew's Grand Theatre, but Oscar winner Hattie McDaniel, an African American, was barred from the event due to the color of her skin.[36]

Atlanta played a vital role in the Allied effort during World War II due the city’s war-related manufacturing companies, railroad network, and military bases, leading to rapid growth in the city's population and economy. In the 1950s, the city’s newly constructed freeway system allowed middle class Atlantans the ability to relocate to the suburbs. As a result, the city began to make up an ever smaller proportion of the metropolitan area’s population, eventually decreasing from 31% in 1960 to 9% in 2000.[37]

During the 1960s, Atlanta was a major organizing center of the Civil Rights Movement, with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Ralph David Abernathy, and students from Atlanta’s historically black colleges and universities playing major roles in the movement’s leadership. While minimal compared to other cities, Atlanta was not completely free of racial strife.[38] In 1961, the city attempted to thwart blockbusting by erecting road barriers in Cascade Heights, countering the efforts of civic and business leaders to foster Atlanta as the "city too busy to hate."[38][39] Desegregation of the public sphere came in stages, with public transportation desegregated by 1959,[40] the restaurant at Rich's department store by 1961,[41] movie theaters by 1963,[42][43] and public schools by 1973.[44]

In 1960, whites comprised 61.7% of the city's population.[45] By 1970, African Americans were a majority of the city’s population and exercised new-found political influence by electing Atlanta’s first black mayor, Maynard Jackson, in 1973. Under Mayor Jackson’s tenure, Atlanta’s airport was modernized, solidifying the city’s role as a transportation center. The opening of the Georgia World Congress Center in 1976 heralded Atlanta’s rise as a convention city.[46] Construction of the city’s subway system began in 1975, with rail service commencing in 1979.[47] However, despite these improvements, Atlanta succumbed to the same decay afflicting major American cities during the era, and the city lost over 100,000 residents between 1970 and 1990, over 20% of its population.[48]

In 1990, Atlanta was selected as the site for the 1996 Summer Olympic Games. Following the announcement, the city government undertook several major construction projects to improve Atlanta’s parks, sporting venues, and transportation infrastructure. While the games themselves were marred by numerous organizational inefficiencies, as well as the Centennial Olympic Park bombing,[49] they were a watershed event in Atlanta’s history, initiating a fundamental transformation of the city in the decade that followed.[48]

During the 2000s, Atlanta underwent a profound transformation demographically, physically, and culturally. Suburbanization, rising prices, a booming economy, and new migrants decreased the city’s black percentage from a high of 67% in 1990 to 54% in 2010.[50][51] From 2000 to 2010, Atlanta gained 22,763 white residents, 5,142 Asian residents, and 3,095 Hispanic residents, while the city’s black population decreased by 31,678.[52][53] Much of the city’s demographic change during the decade was driven by young, college-educated professionals: from 2000 to 2009, the three-mile radius surrounding Downtown Atlanta gained 9,722 residents aged 25 to 34 holding at least a four-year degree, an increase of 61%.[54][55] Between the mid-1990s and 2010, stimulated by funding from the HOPE VI program, Atlanta demolished nearly all of its public housing, a total of 17,000 units and about 10% of all housing units in the city.[56][57][58] In 2005, the $2.8 billion BeltLine project was adopted, with the stated goals of converting a disused 22-mile freight railroad loop that surrounds the central city into an art-filled multi-use trail and increasing the city’s park space by 40%.[59] Lastly, Atlanta’s cultural offerings expanded during the 2000s: the High Museum of Art doubled in size; the Alliance Theatre won a Tony Award; and numerous art galleries were established on the once-industrial Westside.[60]

Geography

Atlanta encompasses 132.4 square miles (342.9 km2), of which 131.7 square miles (341.1 km2) is land and 0.7 square miles (1.8 km2) is water. The city is situated among the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains, and at 1,050 feet (320 m) above mean sea level, Atlanta has the highest elevation out of major cities east of the Mississippi River.[61] Atlanta straddles the Eastern Continental Divide, such that rainwater that falls on the south and east side of the divide flows into the Atlantic Ocean, while rainwater on the north and west side of the divide flows into the Gulf of Mexico.[62] Atlanta sits atop a ridge south of the Chattahoochee River, which is part of the ACF River Basin. Located at the far northwestern edge of the city, much of the river’s natural habitat is preserved, in part by the Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area.[63]

Climate

Atlanta's high elevation distinguishes it from most other southern and eastern cities, and contributes to a more temperate climate than is found in cities at similar latitudes.[64] Under the Köppen classification, it has a humid subtropical climate (Cfa), with hot humid summers and mild, yet temperamental winters. The warm, maritime air can bring spring-like highs while strong Arctic air masses can push lows into the teens (≤ −7 °C). High temperatures in July average 90 °F (32 °C) but occasionally approach 100 °F (38 °C). Temperatures at or above 90 °F (32.2 °C) occur more than 40 days per year. January averages 43.5 °F (6.4 °C), with temperatures in the suburbs slightly cooler. Overnight freezing can be expected 40 nights annually,[65] but high temperatures below 40 °F (4 °C) are very rare. Extremes range from −9 °F (−23 °C) in February 1899 to 106 °F (41 °C) in June 2012.[66]

Typical of the southeastern U.S., Atlanta receives abundant rainfall that is relatively evenly distributed throughout the year, though spring and early fall are markedly drier. Average annual rainfall is 50.2 inches (1,280 mm). Light dusting of snow is typical with an annual average of 2.7 inches (6.9 cm). The heaviest single storm, known as the “Storm of the Century,” brought around 16 inches (41 cm) of snow in March 1993.[67] However, ice storms usually cause more nuisance than snowfall does, the most severe of such storms occurring on January 7, 1973 and January 9, 2011.[68] Tornadoes are rare in the city itself, though twisters such as the March 15, 2008 EF2 tornado damaged prominent structures in downtown Atlanta.

| Climate data for Atlanta (Hartsfield–Jackson Int'l), 1991–2020 normals,[a] extremes 1878–present[b] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 79 (26) |

81 (27) |

89 (32) |

93 (34) |

97 (36) |

106 (41) |

105 (41) |

104 (40) |

102 (39) |

98 (37) |

84 (29) |

79 (26) |

106 (41) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 70.3 (21.3) |

73.5 (23.1) |

80.8 (27.1) |

84.7 (29.3) |

89.6 (32.0) |

94.3 (34.6) |

95.8 (35.4) |

95.9 (35.5) |

91.9 (33.3) |

85.0 (29.4) |

77.5 (25.3) |

71.5 (21.9) |

97.3 (36.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 54.0 (12.2) |

58.2 (14.6) |

65.9 (18.8) |

73.8 (23.2) |

81.1 (27.3) |

87.1 (30.6) |

90.1 (32.3) |

89.0 (31.7) |

83.9 (28.8) |

74.4 (23.6) |

64.1 (17.8) |

56.2 (13.4) |

73.2 (22.9) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 44.8 (7.1) |

48.5 (9.2) |

55.6 (13.1) |

63.2 (17.3) |

71.2 (21.8) |

77.9 (25.5) |

80.9 (27.2) |

80.2 (26.8) |

74.9 (23.8) |

64.7 (18.2) |

54.2 (12.3) |

47.3 (8.5) |

63.6 (17.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 35.6 (2.0) |

38.9 (3.8) |

45.3 (7.4) |

52.5 (11.4) |

61.3 (16.3) |

68.6 (20.3) |

71.8 (22.1) |

71.3 (21.8) |

65.9 (18.8) |

54.9 (12.7) |

44.2 (6.8) |

38.4 (3.6) |

54.1 (12.3) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 17.3 (−8.2) |

23.2 (−4.9) |

28.1 (−2.2) |

36.9 (2.7) |

47.6 (8.7) |

59.9 (15.5) |

65.6 (18.7) |

64.5 (18.1) |

53.4 (11.9) |

38.7 (3.7) |

29.2 (−1.6) |

23.8 (−4.6) |

15.2 (−9.3) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −8 (−22) |

−9 (−23) |

10 (−12) |

25 (−4) |

37 (3) |

39 (4) |

53 (12) |

55 (13) |

36 (2) |

28 (−2) |

3 (−16) |

0 (−18) |

−9 (−23) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 4.59 (117) |

4.55 (116) |

4.68 (119) |

3.81 (97) |

3.56 (90) |

4.54 (115) |

4.75 (121) |

4.30 (109) |

3.82 (97) |

3.28 (83) |

3.98 (101) |

4.57 (116) |

50.43 (1,281) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 1.0 (2.5) |

0.4 (1.0) |

0.4 (1.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.4 (1.0) |

2.2 (5.6) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 11.1 | 10.4 | 10.5 | 8.9 | 9.4 | 11.1 | 12.0 | 10.2 | 7.3 | 6.8 | 7.9 | 10.7 | 116.3 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.01 in) | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 1.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 67.6 | 63.4 | 62.4 | 61.0 | 67.2 | 69.8 | 74.4 | 74.8 | 73.9 | 68.5 | 68.1 | 68.4 | 68.3 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 29.3 (−1.5) |

30.9 (−0.6) |

38.5 (3.6) |

45.7 (7.6) |

56.1 (13.4) |

63.7 (17.6) |

67.8 (19.9) |

67.5 (19.7) |

62.1 (16.7) |

49.6 (9.8) |

41.0 (5.0) |

33.1 (0.6) |

48.8 (9.3) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 164.0 | 171.7 | 220.5 | 261.2 | 288.6 | 284.8 | 273.8 | 258.6 | 227.5 | 238.5 | 185.1 | 164.0 | 2,738.3 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 52 | 56 | 59 | 67 | 67 | 66 | 63 | 62 | 61 | 68 | 59 | 53 | 62 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 2.8 | 4.1 | 6.1 | 7.9 | 9.1 | 9.7 | 9.9 | 9.2 | 7.4 | 5.2 | 3.3 | 2.5 | 6.4 |

| Source 1: NOAA (relative humidity, dew point and sun 1961–1990)[70][71][72] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Extremes[73] UV Index Today (1995 to 2022)[74] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

Most of Atlanta was burned during the Civil War, depleting the city of a large stock of its historic architecture. Yet architecturally, the city had never been particularly "southern”—because Atlanta originated as a railroad town, rather than a patrician southern seaport like Savannah or Charleston, many of the city’s landmarks could have easily been erected in the Northeast or Midwest.[18]

During the Cold War era, Atlanta embraced global modernist trends, especially regarding commercial and institutional architecture. Examples of modernist architecture include the Westin Peachtree Plaza (1976), Georgia-Pacific Tower (1982), the State of Georgia Building (1966), and the Atlanta Marriott Marquis (1985). In the latter half of the 1980s, Atlanta became one of the early adopters of postmodern designs that reintroduced classical elements to the cityscape. Many of Atlanta's tallest skyscrapers were built in the late 1980s and early 1990s, with most displaying tapering spires or otherwise ornamented crowns, such as One Atlantic Center (1987), 191 Peachtree Tower (1991), and the Four Seasons Hotel Atlanta (1992). Also completed during the era is Atlanta’s tallest skyscraper, the Bank of America Plaza (1992), which, at 1,023 feet (312 m), is the 61st-tallest building in the world and the 9th-tallest building in the United States.[75] The city’s embrace of modern architecture, however, translated into an ambivalent approach toward historic preservation, leading to the destruction of notable architectural landmarks, including the Equitable Building (1892-1971), Terminal Station (1905-1972), and the Carnegie Library (1902-1977). The Fox Theatre (1929)—Atlanta’s cultural icon—would have met the same fate had it not been for a grassroots effort to save it in the mid-1970s.[18]

Atlanta is divided into 242 officially defined neighborhoods.[76][77][78] The city contains three major high-rise districts, which form a north-south axis along Peachtree: Downtown, Midtown, and Buckhead.[79] Surrounding these high-density districts are leafy, low-density neighborhoods, most of which are dominated by single-family homes.[80]

Downtown Atlanta contains the most office space in the metro area, much of it occupied by government entities. Downtown is also home to the city’s sporting venues and many of its tourist attractions. Midtown Atlanta is the city’s second-largest business district, containing the offices of many of the region’s law firms. Midtown is also known for its art institutions, cultural attractions, institutions of higher education, and dense form.[81] Buckhead, the city’s uptown district, is eight miles (13 km) north of Downtown and the city’s third-largest business district. The district is marked by an urbanized core along Peachtree Road, surrounded by suburban single-family neighborhoods situated among dense forests and rolling hills.[82]

Surrounding Atlanta’s three high-rise districts are the city's low- and medium-density neighborhoods,[82] where the craftsman bungalow single-family home is dominant.[83] The city’s east side is marked by historic streetcar suburbs built from the 1890s-1930s as havens for the upper middle class. These neighborhoods, many of which contain their own villages encircled by shaded, architecturally distinct residential streets, include the Victorian Inman Park, Bohemian East Atlanta, and eclectic Old Fourth Ward.[18][84] On Atlanta’s west side, former warehouses and factories have been converted into housing, retail space, and art galleries, transforming the once-industrial West Midtown into a model neighborhood for smart growth, historic rehabilitation, and infill construction.[85] In southwest Atlanta, neighborhoods closer to downtown originated as streetcar suburbs, including the historic West End, while those farther from downtown retain a postwar suburban layout, including Collier Heights and Cascade Heights, home to much of the city's affluent African American population.[86][87][88] Northwest Atlanta, marked by Atlanta’s poorest and most crime-ridden neighborhoods, has been the target of community outreach programs and economic development initiatives.[89]

Gentrification of the city's neighborhoods is one of the more controversial and transformative forces shaping contemporary Atlanta. The gentrification of Atlanta has its origins in the 1970s, after many of Atlanta's neighborhoods had undergone the urban decay that affected other major American cities in the mid-20th century. When neighborhood opposition successfully prevented two freeways from being built through city’s the east side in 1975, the area became the starting point for Atlanta's gentrification. After Atlanta was awarded the Olympic games in 1990, gentrification expanded into other parts of the city, stimulated by infrastructure improvements undertaken in preparation for the games. Gentrification was also aided by the Atlanta Housing Authority's eradication of the city’s public housing.[90] The gentrification of the city’s neighborhoods has been the topic of social commentary, including The Atlanta Way, a documentary detailing the negative effects gentrification has had on the city and its inhabitants.

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 2,572 | — | |

| 1860 | 9,554 | 271.5% | |

| 1870 | 21,789 | 128.1% | |

| 1880 | 37,409 | 71.7% | |

| 1890 | 65,533 | 75.2% | |

| 1900 | 89,872 | 37.1% | |

| 1910 | 154,839 | 72.3% | |

| 1920 | 200,616 | 29.6% | |

| 1930 | 270,366 | 34.8% | |

| 1940 | 302,288 | 11.8% | |

| 1950 | 331,314 | 9.6% | |

| 1960 | 487,455 | 47.1% | |

| 1970 | 496,973 | 2.0% | |

| 1980 | 425,022 | −14.5% | |

| 1990 | 394,017 | −7.3% | |

| 2000 | 416,474 | 5.7% | |

| 2010 | 420,003 | 0.8% | |

| 2011 (est.) | 432,427 | 3.0% | |

2011 estimate | |||

The 2010 United States Census reported that Atlanta had a population of 420,003. The population density was 3,154 per square mile (1232/km2). The racial makeup and population of Atlanta was 54.0% Black or African American, 38.4% White, 3.1% Asian and 0.2% Native American. Those from some other race made up 2.2% of the city’s population, while those from two or more races made up 2.0%. Hispanics of any race made up 5.2% of the city’s population.[91][92][93][94] The median income for a household in the city was $45,171. The per capita income for the city was $ 35,453. 22.6% percent of the population was living below the poverty line. However, compared to the rest of the country, Atlanta's cost of living is 6.00% lower than the U.S. average. Atlanta has one of the highest LGBT populations per capita, ranking third among major American cities, behind San Francisco and slightly behind Seattle, with 12.8% of the city’s total population recognizing themselves as gay, lesbian, or bisexual.[95][96]

In the 2010 Census, Atlanta was recorded as the nation’s fourth largest majority black city, and the city has long been known as a center of African American political power, education, and culture, often called a black mecca.[97][98][99] However, African American Atlantans have rapidly suburbanized in recent decades, and from 2000 to 2010, the city's black population decreased by 31,678 people, shrinking from 61.4% of the city’s population in 2000 to 54.0% in 2010.[52][100]

Atlanta has recently undergone a drastic demographic increase in its white population. Between 2000 and 2010, the proportion of whites in the city's population grew faster than that of any other U.S. city. In that decade, Atlanta's white population grew from 31% to 38% of the city’s population, an absolute increase of 22,753 people, more than triple the increase that occurred between 1990 and 2000.[52][100][100][101]

Out of the total population five years and older, 83.3% spoke only English at home, while 8.8% spoke Spanish, 3.9% another Indo-European language and 2.8% an Asian language.[102] Atlanta’s dialect has traditionally been a variation of Southern American English. The Chattahoochee River long formed a border between the Coastal Southern and Southern Appalachian dialects.[103] However, by 2003, Atlanta magazine concluded that Atlanta had become significantly "de-Southernized," with a Southern accent considered a handicap in some circumstances.[104] In general, Southern accents are less prevalent among residents of the city and inner suburbs and among younger people, while they are more common in the outer suburbs and among older people;[103] this pattern coexists alongside Southern variations of African American Vernacular English.

Religion, while historically centered around Protestant Christianity, now involves many faiths as a result of the city and metro area's increasingly international population. While Protestant Christianity still maintains a strong presence in the city, in recent decades Catholicism has gained a strong foothold due to migration patterns. Metro Atlanta also has a considerable number of ethnic Christian congregations, including Korean and Indian churches. Large non-Christian faiths are present in the form of Judaism and Hinduism. Overall, there are over 1,000 places of worship within Atlanta.[105]

Economy

Encompassing $304 billion, the Atlanta metropolitan area is the eighth-largest economy in the country and 17th-largest in the world.[106] Corporate operations comprise a large portion of the Atlanta’s economy, with the city serving as the regional, national, or global headquarters for many corporations. Atlanta contains the country’s third largest concentration of Fortune 500 companies, and the city is the global headquarters of corporations such as The Coca-Cola Company, The Home Depot, Delta Air Lines, AT&T Mobility, UPS, and Newell-Rubbermaid. Over 75 percent of Fortune 1000 companies conduct business operations in the Atlanta metropolitan area, and the region hosts offices of about 1,250 multinational corporations.[107] Many corporations are drawn to Atlanta on account of the city’s educated workforce; as of 2010, nearly 43% of adults in the city of Atlanta have college degrees, compared to 27% in the nation as a whole and 41% in Boston.[108]

Atlanta began as a railroad town and logistics has remained a major component of the city’s economy to this day. Atlanta is an important rail junction and contains major classification yards for Norfolk Southern and CSX. Since its construction in the 1950s, Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport has served as a key engine of Atlanta’s economic growth.[109] Delta Air Lines, the city's largest employer and the metro area’s third largest, operates the world’s largest airline hub at Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport and has helped make Hartsfield-Jackson the world's busiest airport, both in terms of passenger traffic and aircraft operations.[110] Partly due to the airport, Atlanta has become a hub for diplomatic missions; as of 2012, the city contains 25 general consulates, the seventh-highest concentration of diplomatic missions in the United States.[111]

Media is also an important aspect of Atlanta’s economy. The city is a major cable television programming center. Ted Turner established the headquarters of both the Cable News Network (CNN) and the Turner Broadcasting System (TBS) in Atlanta. Cox Enterprises, the country’s third-largest cable television service and the publisher of over a dozen major American newspapers,[112] is headquartered in the city.[113][114][115] NBC Universal’s The Weather Channel is also headquartered in Atlanta.

Largely due to a state-wide tax incentive enacted in 2005, the Georgia Entertainment Industry Investment Act, which awards qualified productions a transferable income tax credit of 20% of all in-state costs for film and television investments of $500,000 or more,[116] Atlanta has become a center for film and television production. Film and television production facilities in Atlanta include Turner Studios, Tyler Perry Studios, Williams Street Productions, and the EUE/Screen Gems soundstages. Film and television production injected $1 billion into Georgia’s economy in 2010, with Atlanta garnering most of the projects.[117][118] Atlanta has gained recognition as a center of production of horror and zombie-related productions,[119] with ‘‘Atlanta’’ magazine dubbing the city the "Zombie Capital of the World".[120][121]

Compared to its peer cities, Atlanta’s economy has been disproportionately affected by the 2008 financial crisis and the subsequent recession. The city’s economic problems are displayed in its elevated unemployment rate, declining real income levels, and depressed housing market.[122][123][124] From 2010-2011, Atlanta saw a 0.9% contraction in employment and a meager 0.4% rise in income. As of 2012, the unemployment rate in Atlanta was over 9%, higher than the national average of 8.2%.[125] These dismal statistics have garnered Atlanta recognition as one of the world’s worst economic performers, with the city’s economy earning a ranking of 189 among 200 global cities, down from a ranking of 89 during the 1990s, when the city realized 1.6% income growth and 2.6% employment growth.[126] However, even when the 2008-2009 period is excluded, the 2001-2007 period is still one of the worst on record for Atlanta: the city never recovered the jobs it lost during the Early 2000s recession, and per capita income declined nearly 5% from 2000 to 2006, the largest decline among major U.S. cities. Thus, Atlanta’s current economic crisis was only worsened, and not caused, by the Recession.[127][128] Adding to the city’s employment and income woes is the spectacular collapse of its housing market. Atlanta home prices fell by 2.1% in January 2012, reaching levels not seen since 1996, a decline that measured among the worst in the country. Compared with a year earlier, the average home price in Atlanta fell 17.3% in February 2012, the largest annual drop in the history of the index for any city. Atlanta home values average $85,000 as of January 2012, second-worst among major metropolitan areas, coming in just behind Detroit.[129][130] This unprecedented collapse in home prices has led some economists to deem Atlanta the worst housing market in the country.[131]

Culture

Atlanta, while very much in the South, has a culture that is no longer strictly Southern. This is because in addition to a large population of migrants from other parts of the U.S., many recent immigrants to the U.S. have chosen to make the city their home, making Atlanta one of the most multi-cultural in the nation.[132] Thus, although traditional Southern culture is part of Atlanta’s cultural fabric, it is mostly the backdrop to one of the nation’s leading international cities. This unique cultural combination reveals itself at the High Museum of Art, the bohemian shops of Little Five Points, and the multi-cultural dining choices found along Buford Highway.[133]

Arts and theater

Atlanta is one of few United States cities with permanent, professional, resident companies in all major performing arts disciplines: opera (Atlanta Opera), ballet (Atlanta Ballet), music (Atlanta Symphony Orchestra), and theater (the Alliance Theatre). Atlanta also attracts many touring Broadway acts, concerts, shows, and exhibitions catering to a variety of interests. Atlanta’s performing arts district is concentrated in Midtown Atlanta at the Woodruff Arts Center, which is home to the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra and the Alliance Theatre. The city also frequently hosts touring Broadway acts, especially at The Fox Theatre, a historic landmark that is among the highest grossing theatres of its size.[134]

As a national center for the arts,[135] Atlanta is home to significant art museums and institutions. The renowned High Museum of Art is arguably the South’s leading art museum and among the most-visited art museums in the world.[136] The Museum of Design Atlanta (MODA), a design museum, is the only such museum in the Southeast.[137] Contemporary art museums include the Atlanta Contemporary Art Center and the Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia. Institutions of higher education also contribute to Atlanta’s art scene, with the Savannah College of Art and Design’s Atlanta campus providing the city’s arts community with a steady stream of curators, and Emory University’s Michael C. Carlos Museum containing the largest collection of ancient art in the Southeast.[138]

Atlanta has played a major or contributing role in the development of various genres of American music at different points in the city's history. Beginning as early as the 1920s, Atlanta emerged as a center for country music, which was brought to the city by migrants from Appalachia.[139] During the countercultural 1960s, Atlanta hosted the Atlanta International Pop Festival, with the 1969 festival taking place more than a month before Woodstock and featuring many of the same bands. The city was also a center for Southern rock during its 1970s heyday: the Allman Brothers Band's hit instrumental "Hot 'Lanta" is an ode to the city, while Lynyrd Skynyrd's famous live rendition of "Free Bird" was recorded at the Fox Theatre in 1976, with lead singer Ronnie Van Zant directing the band to "play it pretty for Atlanta."[140] During the 1980s, Atlanta had an active Punk rock scene that was centered around two of the city’s music venues, 688 Club and the Metroplex, and Atlanta famously played host to the Sex Pistols first U.S. show, which was performed at the Great Southeastern Music Hall.[141] The 1990s saw the birth of Atlanta hip hop, a sub-genre that gained relevance following the success of home-grown duo OutKast; however, it was not until the 2000s that Atlanta moved "from the margins to becoming hip-hop’s center of gravity, part of a larger shift in hip-hop innovation to the South."[142] Also in the 2000s, Atlanta was recognized by the Brooklyn-based Vice magazine for its impressive yet under-appreciated Indie rock scene, which revolves around the EARL in East Atlanta Village.[143][144]

Tourism

As of 2010, Atlanta is the seventh-most visited city in the United States, with over 35 million visitors per year.[145] Although the most popular attraction among visitors to Atlanta is the Georgia Aquarium,[146] the world’s largest indoor aquarium,[147] Atlanta’s tourism industry mostly driven by the city’s history museums and outdoor attractions. Atlanta contains a notable amount of historical museums and sites, including the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site, which includes the preserved boyhood home of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., as well as his final resting place; the Atlanta Cyclorama & Civil War Museum, which houses a massive painting and diorama in-the-round, with a rotating central audience platform, depicting the Battle of Atlanta in the Civil War; the World of Coca-Cola, featuring the history of the world famous soft drink brand and its well-known advertising; the Carter Center and Presidential Library, housing U.S. President Jimmy Carter’s papers and other material relating to the Carter administration and the Carter family’s life; and the Margaret Mitchell House and Museum, site of the writing of the best-selling novel Gone With the Wind.

Atlanta also contains various outdoor attractions.[148] The Atlanta Botanical Garden, adjacent to Piedmont Park, is home to the 600-foot-long (180 m) Kendeda Canopy Walk, a skywalk that allows visitors to tour one of the city’s last remaining urban forests from 40-foot-high (12 m). The Canopy Walk is considered the only canopy-level pathway of its kind in the United States. Zoo Atlanta, located in Grant Park, accommodates over 1,300 animals representing more than 220 species. Home to the nation’s largest collections of gorillas and orangutans, the Zoo is also one of only four zoos in the U.S. to house giant pandas.[149] Festivals showcasing arts and crafts, film, and music, including the Atlanta Dogwood Festival, the Atlanta Film Festival, and Music Midtown, respectively, are also popular with tourists.[150]

Tourists are also drawn to the city’s culinary scene, which comprises a mix of urban establishments garnering national attention, ethnic restaurants serving cuisine from every corner of the world, and traditional eateries specializing in Southern dining. Since the turn of the 21st century, Atlanta has emerged as a sophisticated restaurant town.[151] Many restaurants opened in the city’s gentrifying neighborhoods have received praise at the national level, including Bocado, Bacchanalia, and Miller Union in West Midtown, Empire State South in Midtown, and Two Urban Licks and Rathbun’s on the east side.[60][152][153][154] In 2011, the ‘‘New York Times’’ characterized Empire State South and Miller Union as reflecting "a new kind of sophisticated Southern sensibility centered on the farm but experienced in the city."[155] Visitors seeking to sample international Atlanta are directed to Buford Highway, the city’s international corridor. There, the million-plus immigrants that make Atlanta home have established various authentic ethnic restaurants representing virtually every nationality on the globe.[156] For traditional Southern fare, one of the city’s most famous establishments is The Varsity, a long-lived fast food chain and the world’s largest drive-in restaurant.[157] Mary Mac's Tea Room and Paschal's are more formal destinations for Southern food.

Sports

Atlanta is home to professional franchises for three major team sports: the Atlanta Braves of Major League Baseball, the Atlanta Hawks of the National Basketball Association, and the Atlanta Falcons of the National Football League. The Braves, who moved to Atlanta in 1966, are the oldest continually operating professional sports franchise in the United States. The Braves won the World Series in 1995, and had an unprecedented run of 14 straight divisional championships from 1991 to 2005.[158] The Atlanta Falcons have played in Atlanta since 1966. The Falcons have won the division title five times (1980, 1998, 2004, 2010, 2012) and the conference championship once, when they finished as the runner-up to the Denver Broncos in Super Bowl XXXIII in 1999.[159] The Atlanta Hawks began in 1946 as the Tri-Cities Blackhawks, playing in Moline, Illinois. The team moved to Atlanta in 1968, and they currently play their games in Philips Arena.[160] The Atlanta Dream is the city’s Women’s National Basketball Association franchise.[161]

Atlanta has also had its own professional ice hockey and soccer franchises. The National Hockey League (NHL) has had two Atlanta franchises: the Atlanta Flames began play in 1972 before moving to Calgary in 1980, while the Atlanta Thrashers began play in 1999 before moving to Winnipeg in 2011. The Atlanta Chiefs was the city’s professional soccer team from 1967 to 1972, and the team won a national championship in 1968.

Atlanta has been the host city for various international, professional and collegiate sporting events. Most famously, Atlanta hosted the Centennial 1996 Summer Olympics. Atlanta has also hosted Super Bowl XXVIII in 1994 and Super Bowl XXXIV in 2000. In professional golf, The Tour Championship, the final PGA Tour event of the season, is played annually at East Lake Golf Club. In 2001 and 2011, Atlanta hosted the PGA Championship, one of the four major championships in men’s professional golf, at the Atlanta Athletic Club. In professional ice hockey, the city hosted the 56th NHL All-Star Game in 2008, three years before the Thrashers moved. In 2011, Atlanta hosted professional wrestling’s annual WrestleMania. The city has hosted the NCAA Final Four Men’s Basketball Championship five times, most recently in 2013. In college football, Atlanta hosts the Chick-fil-A College Kickoff, the SEC Championship Game, and the Chick-fil-A Bowl.[162]

Parks and recreation

Atlanta's 343 parks, nature preserves, and gardens cover 3,622 acres (14.66 km2),[163] which amounts to only 5.6% of the city's total acreage, compared the national average of just over 10%.[164][165] However, 63% of Atlantans live within a 10-minute walk of a park, placing the city just above the national average of 62%.[164][165] Piedmont Park, located in Midtown is Atlanta’s iconic green space. The park, which underwent a major renovation and expansion in 2010, attracts visitors from across the region and hosts cultural events throughout the year. Other notable city parks include Centennial Olympic Park, a legacy of the 1996 Summer Olympics that forms the centerpiece of the city’s tourist district; Woodruff Park, which anchors the central business district and the campus of Georgia State University; Grant Park, home to both Zoo Atlanta and the Atlanta Cyclorama & Civil War Museum; and Chastain Park, which houses an amphitheater used for live music concerts. The Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area, located in the northwestern corner of the city, preserves a 48 mi (77 km) stretch of the river for public recreation opportunities. The Atlanta Botanical Garden, adjacent to Piedmont Park, contains formal gardens, including a Japanese garden and a rose garden, woodland areas, and a conservatory that includes indoor exhibits of plants from tropical rainforests and deserts. The BeltLine, a former rail corridor that forms a 22 mi (35 km) loop around Atlanta’s core, will eventually be transformed into a series of parks, connected by a multi-use trail, increasing Atlanta’s park space by 40%.[166]

Atlanta offers resources and opportunities for amateur and participatory sports and recreation. Jogging is a particularly popular local sport. The Peachtree Road Race, the world’s largest 10 km race, is held annually on Independence Day.[167] The Georgia Marathon, which begins and ends at Centennial Olympic Park, routes through the city’s historic east side neighborhoods.[168] Golf and tennis are also popular in Atlanta, and the city contains six public golf courses and 182 tennis courts. Facilities located along the Chattahoochee River cater to watersports enthusiasts, providing the opportunity for kayaking, canoeing, fishing, boating, or tubing. The city's only skate park, a 15,000 square feet (1,400 m2) facility that offers bowls, curbs, and smooth-rolling concrete mounds, is located at Historic Fourth Ward Park.[169]

Law and government

Atlanta is governed by a mayor and the Atlanta City Council. The city council consists of 15 representatives—one from each of the city’s 12 districts and three at-large positions. The mayor may veto a bill passed by the council, but the council can override the veto with a two-thirds majority.[170] The mayor of Atlanta is Kasim Reed, a Democrat elected on a nonpartisan ballot whose first term in office will expire at the end of 2013. Every mayor elected since 1973 has been black.[171] In 2001, Shirley Franklin became the first woman to be elected Mayor of Atlanta, and the first African-American woman to serve as mayor of a major southern city.[172] Atlanta city politics suffered from a notorious reputation for corruption during the 1990s administration of Bill Campbell, who was convicted by a federal jury in 2006 on three counts of tax evasion in connection with gambling income he received while Mayor during trips he took with city contractors.[173]

As the state capital, Atlanta is the site of most of Georgia’s state government. The Georgia State Capitol building, located downtown, houses the offices of the governor, lieutenant governor and secretary of state, as well as the General Assembly. The Governor's Mansion is located in a residential section of Buckhead. Atlanta serves as the regional hub for many arms of the federal bureaucracy, including the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.[174][175] Atlanta also plays an important role in federal judiciary system, containing the United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit and of the United States District Court for the Northern District of Georgia.

Historically, Atlanta has been a stronghold for the Democratic Party. Although municipal elections are officially nonpartisan, nearly all of the city’s elected officials are registered Democrats. The city is split between 14 state house districts and four state senate districts, all held by Democrats. At the federal level, Atlanta is split between two congressional districts. The northern three-fourths of the city is located in the 5th district, represented by Democrat John Lewis. The southern fourth is in the 13th district, represented by Democrat David Scott.

The city is served by the Atlanta Police Department, which numbers 1,700 officers and oversaw a 40% decrease in the city's crime rate between 2001 and 2009. Specifically, homicide decreased by 57%, rape by 72%, and violent crime overall by 55%. Crime is down across the country, but Atlanta’s improvement has occurred at more than twice the national rate.[176] Forbes ranked Atlanta as the sixth most dangerous city in the United States.[177]

Education

Due to the more than 30 colleges and universities located in the city, Atlanta is considered a center for higher education.[178] Among the most prominent public universities in Atlanta is the Georgia Institute of Technology, a research university located in Midtown that has been consistently ranked among the nation’s top ten public universities for its degree programs in engineering, computing, management, the sciences, architecture, and liberal arts. Georgia State University, a public research university located in Downtown Atlanta, is the second largest of the 35 colleges and universities in the University System of Georgia and a major contributor to the revitalization of the city’s central business district. Atlanta is also home to nationally renowned private colleges and universities, most notably Emory University, a leading liberal arts and research institution that ranks among the top 20 schools in the United States and operates Emory Healthcare, the largest health care system in Georgia.[179] Also located in the city is the Atlanta University Center, the largest contiguous consortium of historically black colleges, comprising Clark Atlanta University, Morehouse College, Spelman College, and Interdenominational Theological Center. Atlanta also contains a campus of the Savannah College of Art and Design, a private art and design university that has proven to be a major factor in the recent growth of Atlanta’s visual art community.

Atlanta Public Schools enrolls 55,000 students in 106 schools, some of which are operated as charter schools.[180] The district has been plagued by a widely publicized cheating scandal exposed in 2009. Atlanta is also served by various private schools, as well as parochial Roman Catholic schools operated by the Archdiocese of Atlanta.

Media

The primary network-affiliated television stations in Atlanta are WXIA-TV (NBC), WGCL-TV (CBS), WSB-TV (ABC), and WAGA-TV (Fox). The Atlanta metropolitan area is served by two public television stations and one public radio station. WGTV is the flagship station of the statewide Georgia Public Television network and is a PBS member station, while WPBA is owned by Atlanta Public Schools. Georgia Public Radio is listener-funded and comprises one NPR member station, WABE, a classical music station operated by Atlanta Public Schools.

Atlanta is served by the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, its only major daily newspaper with wide distribution. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution is the result of a 1950 merger between The Atlanta Journal and The Atlanta Constitution, with staff consolidation occurring in 1982 and separate publication of the morning Constitution and afternoon Journal ceasing in 2001.[181] Alternative weekly newspapers include Creative Loafing, which has a weekly print circulation of 80,000. Atlanta magazine is an award-winning, monthly general-interest magazine based in and covering Atlanta.

Transportation

Atlanta's transportation infrastructure comprises a complex network that includes a heavy rail subway system, multiple interstate highways, the world's busiest airport, and over 45 miles of bike paths.

The Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority (MARTA) provides public transportation in the form of buses and heavy rail. Notwithstanding heavy automotive usage in Atlanta, the city’s subway system is the eighth busiest in the country.[182] MARTA rail lines connect many key destinations, such as the airport, Downtown, Midtown, Buckhead, and Perimeter Center. However, significant destinations, such as Emory University, Cumberland and Turner Field, remain unserved. As a result, a 2012 Brookings Institution study placed Atlanta 87th of 100 metro areas for transit accessibility.[183] Emory University operates its Cliff shuttle buses with 200,000 boardings per month, while private minibuses ply Buford Highway. Amtrak, the national rail passenger system, provides service to Atlanta via the ‘‘Crescent train’’ (New York–New Orleans), which stops at Peachtree Station.[184]

With a comprehensive network of freeways that radiate out from the city, automobiles are the dominant mode of transportation in the region.[185] Three major interstate highways converge in Atlanta: I-20 (east-west), I-75 (northwest-southeast), and I-85 (northeast-southwest). The latter two combine in the middle of the city to form the Downtown Connector (I-75/85), which carries more than 340,000 vehicles per day and is one of the ten most congested segments of interstate highway in the United States.[186] Atlanta is mostly encircled by Interstate 285, a beltway locally known as "the Perimeter" that has come to mark the boundary between “Inside the Perimeter” (ITP), the city and close-in suburbs, and “Outside the Perimeter” (OTP), the outer suburbs and exurbs. The heavy reliance on automobiles for transportation in Atlanta has resulted in traffic, commute, and air pollution rates that rank among the worst in the country.[187][188][189]

Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport, the world's busiest airport as measured by passenger traffic and aircraft traffic,[190] offers air service to over 150 U.S. destinations and more than 80 international destinations in 52 countries, with over 2,700 arrivals and departures daily.[191] Delta Air Lines maintains its largest hubs at the airport.[192] Situated 10 miles (16 km) south of downtown, the airport covers most of the land inside a wedge formed by Interstate 75, Interstate 85, and Interstate 285.

Cycling is a growing mode of transportation in Atlanta, more than doubling since 2009, when it comprised 1.1% of all commutes (up from 0.3% in 2000).[193][194] Although Atlanta’s lack of bike lanes may deter many residents from cycling,[193][195] the city’s transportation plan calls for the construction of 226 miles of bike lanes by 2020, with the BeltLine helping to achieve this goal.[196]

Tree canopy

For a sprawling city with the nation's ninth-largest metro area, Atlanta is surprisingly lush with trees—magnolias, dogwoods, Southern pines, and magnificent oaks.

National Geographic magazine, in naming Atlanta a "Place of a Lifetime"[197]

Atlanta has a reputation as the "city in a forest" due to an abundance of trees that is unique among major cities.[198][199][200][201][202] The city’s main street is named after a tree, and beyond the Downtown, Midtown, and Buckhead business districts, the skyline gives way to a dense canopy of woods that spreads into the suburbs. The city is home to the Atlanta Dogwood Festival, an annual arts and crafts festival held one weekend during early April, when the native dogwoods are in bloom. However, the nickname is also factually accurate, as the city’s tree coverage percentage is at 36%, the highest out of all major American cities, and above the national average of 27%.[203] Atlanta’s tree coverage does not go unnoticed—it was the main reason cited by ‘‘National Geographic’’ in naming Atlanta a "Place of a Lifetime."[204][205]

The city’s lush tree canopy, which filters out pollutants and cools sidewalks and buildings, has increasingly been under assault from man and nature due to heavy rains, drought, aged forests, new pests, and urban construction. A 2001 study found that Atlanta’s heavy tree cover declined from 48% in 1974 to 38% in 1996.[206] However, the problem is being addressed by community organizations and city government: Trees Atlanta, a non-profit organization founded in 1985, has planted and distributed over 75,000 shade trees in the city,[207] while Atlanta’s government has awarded $130,000 in grants to neighborhood groups to plant trees.[199]

Sister cities

Atlanta has 18 sister cities, as designated by Sister Cities International, Inc. (SCI):[208]

|

See also

Notes

References

- ^ "Love it or loathe it, the city’s nickname is accurate for the summer", ‘‘Atlanta Journal-Constitution’’, June 16, 2008

- ^ “The service, dubbed the Atlanta Tourist Loop as a play on the city’s "ATL" nickname, will start April 29 downtown.” “Buses to link tourist favorites” ‘‘The Atlanta Journal-Constitution’’

- ^ "Atlanta May No Longer Be the City in a Forest", ‘‘WSB-TV’’

- ^ "Because we're the only city easily identified by just one letter". Creative Loafing. November 23, 2011. Retrieved October 7, 2012.

- ^ "Our Quiz Column". Sunny South. p. 5.

- ^ http://atlantablackstar.com/2012/07/23/atlanta-becoming-the-hollywood-of-the-south/

- ^ The term "Atlantans" is widely used by both local media and national media.

- ^ "US Census Bureau". 2010.census.gov. March 17, 2011. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- ^ http://www.census.gov/popest/data/metro/totals/2012/tables/CBSA-EST2012-01.csv

- ^ ""Who's right? Cities lay claim to civil rights 'cradle' mantle"/'"Atlanta Journal-Constitution''". Politifact.com. June 28, 2011. Retrieved May 17, 2012.

- ^ "MONTHLY AIRPORT TRAFFIC REPORT" (PDF). Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport. December 2008. Retrieved December 13, 2010.

- ^ "DOT: Hartsfield-Jackson busiest airport, Delta had 3rd-most passengers". March 13, 2008.

- ^ "Top Industry Publications Rank Atlanta as a LeadingCity for Business. | North America > United States from". AllBusiness.com. Retrieved April 5, 2010.

- ^ "Doing Business in Atlanta, Georgia". Business.gov. Retrieved April 5, 2010.

- ^ "GaWC - The World According to GaWC 2010". Lboro.ac.uk. September 14, 2011. Retrieved July 16, 2012.

- ^ "Global Cities 2010: The Rankings". Foreign Policy. Retrieved November 6, 2010.

- ^ "Atlanta: Economy - Major Industries and Commercial Activity". City-data.com. Retrieved July 16, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Gournay, Isabelle. "AIA Guide to the Architecture of Atlanta". University of Georgia Press. Retrieved September 28, 2011.

- ^ "IDEALS @ Illinois: Governmentality: the new urbanism and the creative class within Atlanta, Georgia". Hdl.handle.net. May 22, 2012. Retrieved March 25, 2013.

- ^ "Northwest Georgia's Native American History". Chieftains Trail. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- ^ USDM.net. "Atlanta Trivia Facts and Folklore". Atlanta.net. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- ^ "Land Cessions of American Indians in Georgia". Ngeorgia.com. June 5, 2007. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- ^ "New Georgia Encyclopedia, "Fulton County"". Georgiaencyclopedia.org. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- ^ "New Georgia Encyclopedia, "DeKalb County"". Georgiaencyclopedia.org. June 19, 2008. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- ^ "Creation of the Western and Atlantic Railroad". About North Georgia. Golden Ink. Retrieved November 12, 2007.

- ^ Thrasherville State Historical Marker, retrieved on November 13, 2009.

- ^ a b "A Short History of Atlanta: 1782–1859". CITY-DIRECTORY, Inc. September 22, 2007. Retrieved December 1, 2007.

- ^ "Georgia History Timeline Chronology for December 29". Our Georgia History. Retrieved August 30, 2007.

- ^ Storey, Steve. "Atlanta & West Point Railroad". Georgia’s Railroad History & Heritage. Retrieved September 28, 2007.

- ^ "Atlanta Old and New: 1848 to 1868". Roadside Georgia. Golden Ink. Retrieved November 13, 2007.

- ^ "A Short History of Atlanta: 1860–1864". CITY-DIRECTORY, Inc. September 22, 2007. Retrieved December 1, 2007.

- ^ Jackson, Edwin L. "The Story of Georgia's Capitols and Capital Cities". Carl Vinson Institute of Government, University of Georgia. Archived from the original on October 9, 2007. Retrieved November 13, 2007.

- ^ "The South: Vast Resources, Rapid Development, Wonderful Opportunities for Capital and Labor..." New York Times. June 8, 1895.

- ^ "Atlanta Race Riot". The Coalition to Remember the 1906 Atlanta Race Riot. Retrieved September 6, 2006.

- ^ Klapper, Melissa, R., PhD. "20th-Century Jewish Immigration." Teachinghistory.org, accessed 6 February 2012.

- ^ "Atlanta Premiere of Gone With The Wind". Ngeorgia.com. Retrieved April 5, 2010.

- ^ "Atlanta Metropolitan Growth from 1960". Demographia.com. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- ^ a b White flight: Atlanta and the making of modern conservatism By Kevin Michael Kruse. Google Books. February 1, 2008. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- ^ Friday, Jan. 18, 1963 (January 18, 1963). ""The South: Divided City", Time magazine, January 18, 1961". TIME. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Bus desegregation in Atlanta". Digital Library of Georgia.

- ^ "Rich's Department Store". New Georgia Encyclopedia.

- ^ "Negroes Attend Atlanta Theaters". Atlanta Journal. May 15, 1962.

- ^ "Moments in the 1960s". Daily Report.

- ^ "APS Timeline". Atlanta Regional Council for Higher Education.

- ^ "Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved January 2, 2012.

- ^ "Fun Facts". Gwcc.com. Retrieved July 16, 2012.

- ^ "History of MARTA - 1970-1979". Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority. Archived from the original on February 4, 2005. Retrieved March 2, 2008.

- ^ a b "Do Olympic Host Cities Ever Win? - NYTimes.com". Roomfordebate.blogs.nytimes.com. October 2, 2009. Retrieved July 16, 2012.

- ^ "Olympic Games Atlanta, Georgia, U.S., 1996". Encyclopædia Britannica online. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved January 2, 2008.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ U.S. Census Bureau

- ^ a b c Galloway, Jim (March 23, 2011). "A census speeds Atlanta toward racially neutral ground | Political Insider". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved July 16, 2012.

- ^ Dewan, Shaila (March 11, 2006). "Gentrification Changing Face of New Atlanta". The New York Times.

- ^ "Urban centers draw more young, educated adults". USA Today. April 1, 2011.

- ^ Schneider, Craig (April 13, 2011). "Young professionals lead surge of intown living". ajc.com. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- ^ "A Choice with No Options: Atlanta Public Housing Residents' Lived Experiences in the Face of Relocation" (PDF). Georgia State University.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Husock, Howard. "Reinventing Public Housing: Is the Atlanta Model Right for Your City?" (PDF). Manhattan Institute for Policy Research.

- ^ US Census Bureau 1990 census - total number of housing units in Atlanta city

- ^ Atlanta BeltLine

- ^ a b Martin, Timothy W. (April 16, 2011). "The New New South". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ “Altitudes of Major US Cities,” Red Oaks Trading, Ltd.

- ^ Yeazel, Jack (March 23, 2007). "Eastern Continental Divide in Georgia". Retrieved July 5, 2007.

- ^ "Florida, Alabama, Georgia water sharing" (news archive). WaterWebster. Retrieved July 5, 2007.

- ^ "New Georgia Encyclopedia: Atlanta". Georgiaencyclopedia.org. January 5, 2010. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- ^ "NowData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved November 30, 2012.

- ^ "Monthly Averages for Atlanta, Georgia (30303)" (Table). Weather Channel. Retrieved March 23, 2008.

- ^ "Atlanta, Georgia (1900–2000)". Our Georgia History. Retrieved April 2, 2006.

- ^ "Ice Storms". Storm Encyclopedia. Weather.com. Retrieved April 2, 2006.

- ^ ThreadEx

- ^ "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991–2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on May 4, 2021. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- ^ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- ^ "WMO Climatological Normals of Atlanta/Hartsfield INTL AP, GA". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- ^ "CLIMATOLOGICAL NORMALS (CLINO) . FOR THE PERIOD 1961-1990" (PDF). World Meteorological Orgniaztion. 1996. pp. 435, 440. ISBN 92-63-0084 7-7. Retrieved April 23, 2024.

Atlanta/Mun. GA 72219

- ^ "Historical UV Index Data - Atlanta, GA". UV Index Today. Retrieved April 20, 2023.

- ^ "World's Tallest Buildings". Infoplease. Retrieved June 26, 2007.

- ^ "City of Atlanta, "Atlanta Neighborhoods"". Atlantaga.gov. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- ^ "Neighborhoods", Central Atlanta Progress

- ^ "MIdtown Atlanta: Neighborhoods", Midtown Alliance

- ^ "Districts and Zones of Atlanta". Emporis.com. Retrieved June 26, 2007.

- ^ Atlanta: a city of neighborhoods - Joseph F. Thompson, Robert Isbell - Google Books. Books.google.com. Retrieved July 16, 2012.

- ^ Southerland, Randy (November 19, 2004). "What do Atlanta's big law firms see in Midtown?". Atlanta Business Chronicle. Retrieved December 1, 2008.

- ^ a b By DAVID KIRBYPublished: November 02, 2003 (November 2, 2003). "A Tab Of Two Cities: Atlanta, Old And New - New York Times". Nytimes.com. Retrieved July 16, 2012.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ [AIA guide to the architecture of Atlanta, edited by Gerald W. Sams, University of Georgia Press, 1993, p. 195]

- ^ Greenfield, Beth (May 29, 2005). "SURFACING - EAST ATLANTA - The Signs of Chic Are Emerging - NYTimes.com". Atlanta (Ga); Georgia: New York Times. Retrieved October 16, 2012.

- ^ Dewan, Shaila (November 19, 2009). "An Upstart Art Scene, on Atlanta's West Side - NYTimes.com". Atlanta (Ga): Travel.nytimes.com. Retrieved July 16, 2012.

- ^ "Atlanta mayor’s race: Words of support", ‘‘Atlanta Journal-Constitution’’, November 1, 2009

- ^ "The Black Middle Class: Where It Lives", ‘‘Ebony’’, August 1987

- ^ "Atlanta’s minorities see dramatic rise in homeownership", ‘‘Chicago Tribune’’, June 27, 2004

- ^ Wheatley, Thomas (December 15, 2010). "Wal-Mart and Prince Charles give Vine City a boost | News & Views | Creative Loafing Atlanta". Clatl.com. Retrieved July 16, 2012.

- ^ Search Site. "Atlanta's Public-Housing Revolution by Howard Husock, City Journal Autumn 2010". City-journal.org. Retrieved July 16, 2012.

- ^ DP-1. Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2000; Data Set: Census 2000 Summary File 1 (SF 1) 100-Percent Data; Geographic Area: Atlanta city, Georgia, US Census Bureau

- ^ Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010" (Select Atlanta (city), Georgia), US Census Bureau

- ^ City of Atlanta Quick Facts, US Census Bureau

- ^ "Living Cities" study, Brookings Institution

- ^ "The Seattle Times: 12.9% in Seattle are gay or bisexual, second only to S.F., study says". Seattletimes.nwsource.com. November 15, 2006. Retrieved April 5, 2010.

- ^ Gary J. Gates Template:PDFlink. The Williams Institute on Sexual Orientation Law and Public Policy, UCLA School of Law October, 2006.

- ^ "A CHAMPION FOR ATLANTA: Maynard Jackson: ‘Black mecca’ burgeoned under leader", ‘‘Atlanta Journal-Constitution’’, June 29, 2003

- ^ "the city that calls itself America’s ‘ Black Mecca’" in "Atlanta Is Less Than Festive on Eve of Another ‘Freaknik’", ‘‘Washington Post’’, Apr 18, 1996

- ^ "Atlanta emerges as a center of black entertainment", ‘‘New York Times’’, November 26, 2011

- ^ a b c Wheatley, Thomas (March 21, 2011). "Thomas Wheatley, "Atlanta's census numbers reveal dip in black population – and lots of people who mysteriously vanished", Creative Loafing, March 21, 2011". Clatl.com. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- ^ Gurwitt, Rob (July 1, 2008). "Governing Magazine: Atlanta and the Urban Future, July 2008". Governing.com. Retrieved April 5, 2010.

- ^ U.S. Census 2008 American Community Survey

- ^ a b "Tongue Twisters", ‘'Atlanta’' magazine. Books.google.com. December 2003. Retrieved May 17, 2012.

- ^ "Too Southern for Atlanta", ‘'Atlanta’' magazine. Books.google.com. February 2003. Retrieved May 17, 2012.

- ^ "Atlanta, Ga". Information Please Database. Pearson Education, Inc. Retrieved May 17, 2006.

- ^ "Global city GDP rankings 2008–2025". Pricewaterhouse Coopers. Retrieved November 20, 2009.

- ^ "CNN Money - Fortune Magazine - Fortune 500 2011".

- ^ “Betting on Atlanta”, EDWARD L. GLAESER, New York Times

- ^ Allen, Frederick (1996). Atlanta Rising. Atlanta, Georgia: Longstreet Press. ISBN 1-56352-296-9.

- ^ "Atlanta's top employers, 2006" (PDF). Metro Atlanta Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 25, 2007. Retrieved August 8, 2007.

- ^ "Consulates & Consular Services". Georgia.org. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "About Cox". Cox Communications, Inc. Retrieved August 22, 2007.

- ^ "Cox Enterprises, Inc. Reaches Agreement to Acquire Public Minority Stake in Cox Communications, Inc." Cox Enterprises. October 19, 2004. Retrieved on July 4, 2009.

- ^ "City Council Districts." City of Sandy Springs. Retrieved on July 4, 2009.

- ^ "Atlanta Headquarters." ‘‘Cox Communications’’. Retrieved on April 22, 2009.

- ^ Georgia Department of Economic Development

- ^ “Film credit helping to pull in $1B in revenue” ‘‘Atlanta Business Chronicle’’

- ^ http://www.bizjournals.com/atlanta/print-edition/2012/03/09/lights-camera-action.html http://atlantarealestate.citybizlist.com/3/2012/6/10/Study-Atlanta-Ranked-Second-Among-LowestCost-Business-Locations-in-US.aspx

- ^ Brown, Robbie (October 18, 2011). "Zombie Apocalypse? Atlanta Says Bring It On". New York Times. Retrieved May 17, 2012.

- ^ Justin Heckert (September 2011). "Zombies are so hot right now". Atlantamagazine.com. Retrieved May 17, 2012.

- ^ George Mathis (October 19, 2011). "Atlanta the new 'zombie capital". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved May 17, 2012.

- ^ “Business boosters admit Atlanta in ‘crisis’ amid effort to boost city’s economy”, Greg Bluestein, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

- ^ New Olympic moment, Christopher B. Leinberger, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

- ^ ‘Hotlanta’ isn’t what it once was, Christopher B. Leinberger, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

- ^ “Jobs up, but not the housing market”, Michael E. Kanell, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

- ^ "Brookings: Atlanta economy ranked with the weakest”, Atlanta Business Chronicle

- ^ “Personal Income in the 2000s: Top and Bottom Ten Metropolitan Areas”, Wendell Cox, NewGeography

- ^ “Real Income Growth across Metropolitan Areas”, Tim Dunne and Kyle Fee, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland

- ^ , “US home prices drop for 6th straight month”, Christopher s. Rugaber, Associated Press

- ^ “In Atlanta, Housing Woes Reflect Nation’s Pain”, Motoko Rich, New York Times

- ^ “PRESENTING: The Worst Housing Market In The Country”, Eric Platt, BusinessInsider

- ^ Garner, Marcus K. (December 18, 2010). "Foreign-born population continues to grow in metro Atlanta". ajc.com. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- ^ "Introduction in Atlanta at Frommer's". Frommers.com. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- ^ "1988: ‘‘Performance’’ magazine names the Fox Theatre the number one grossing theatre in the 3,000–5,000 seat category with the most events, the greatest box office receipts, and the highest attendance in the U.S." and "2009: Billboard magazine names the Fox the No. 1 non-residency theatre for the decade with 5,000 seats or less." on ‘‘Timeline’’, Fox Theatre website

- ^ Clary, Jennifer (Summer 2010). "Top 25 Big Cities". AmericanStyle Magazine (72).

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Goldstein, Andrew. "Museum attendance rises as the economy tumbles". The Art Newspaper. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- ^ [2][dead link]

- ^ "Michael C. Carlos Museum Pictures, Atlanta, GA – AOL Travel". Travel.aol.com. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- ^ Daniel, Wayne W. Pickin’ on Peachtree: a History of Country Music in Atlanta, Georgia. Books.google.com. Retrieved May 17, 2012.

- ^ The Robesonian, Nov. 7, 1976, “Rock’s Top Southern Sound Viewed as Lynyrd Skynyrd”

- ^ , “Atlanta punk! A reunion for 688 and Metroplex”, Scott Henry, Creative Loafing, 10/1/2008

- ^ John Caramanica, "Gucci Mane, No Holds Barred ", ‘‘New York Times’’, December 11, 2009

- ^ Radford, Chad (February 25, 2009). "Damn hipsters: Is Atlanta falling prey to its indie cachet?". Creative Loafing.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Hines, Jack. "The VICE Guide to Atlanta". VICE. Retrieved July 16, 2012.

- ^ Murray, Valaer. "List: America's Most-Visited Cities". Forbes.

- ^ "Members & Donors | About Us". Georgia Aquarium. November 23, 2005. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- ^ "Big window to the sea". CNN. November 23, 2005. Retrieved January 1, 2008.

- ^ "Many quiet delights to be found in Atlanta | The Canadian Jewish News". Cjnews.com. March 2, 2012. Retrieved July 16, 2012.

- ^ "Pandas to Present". Zooatlanta.org. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- ^ "Park History". Piedmont Park Conservancy. Archived from the original on July 4, 2007. Retrieved July 7, 2007.

- ^ "Frommer's best bets for dining in Atlanta". MSNBC. May 30, 2006. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- ^ "TWO urban licks". TWO urban licks. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- ^ "Details Magazine – Official Site". Kevinrathbun.com. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- ^ "America's Hottest New Restaurants". The Daily Beast. November 18, 2010. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- ^ Severson, Kim (May 6, 2011). "Atlanta serves sophisticated Southern". Atlanta (Ga): Travel.nytimes.com. Retrieved May 17, 2012.

- ^ Stuart, Gwynedd (June 24, 2004). "Highway to heaven | Cover Story | Creative Loafing Atlanta". Clatl.com. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- ^ "The Varsity: What'll Ya Have". The Varsity. Retrieved July 7, 2007.

- ^ "The Story of the Braves." ‘‘Atlanta Braves.’’ Retrieved on April 29, 2008.

- ^ "History: Atlanta Falcons." ‘‘Atlanta Falcons.’’ Retrieved on April 29, 2008.[dead link]

- ^ "A Franchise Rich With Tradition: From Pettit To ‘Pistol Pete’ To The ‘Human Highlight Film’." ‘‘Atlanta Hawks.’’ Retrieved on April 29, 2008.

- ^ "The WNBA Is Coming to Atlanta in 2008". WNBA.com. WNBA Enterprises, LLC. January 22, 2008. Retrieved March 21, 2008.

- ^ Corso, Dan (April 29, 2011). "Atlanta has what it takes to host major events". Atlanta Business Chronicle. Retrieved February 1, 2011.

- ^ ""List of parks, alphabetical", City of Atlanta". Atlantaga.gov. November 27, 2011. Retrieved May 17, 2012.

- ^ a b McWilliams, Jeremiah (May 28, 2012). "Atlanta parks system ranks below average". ajc.com. Retrieved July 16, 2012.

- ^ a b "Atlanta parks get low marks in national survey | News | Old Fourth Ward News". Oldfourthward.11alive.com. July 6, 2012. Retrieved July 16, 2012.

- ^ By Kaid Benfield (July 27, 2011). "The Atlanta BeltLine: The country's most ambitious smart growth project". Grist. Retrieved July 16, 2012.

- ^ Shirreffs, Allison (November 14, 2005). "Peachtree race director deflects praise to others". Atlanta Business Chronicle. Retrieved January 1, 2008.

- ^ “Runners to trek from Athens to Atlanta then run Georgia Marathon for charity” Athens Banner-Herald, Feb. 11, 2012

- ^ "Microsoft Word - Parks & Recreation Revised.doc" (PDF). Retrieved October 16, 2012.

- ^ "Atlanta City Councilman H Lamar Willis". H Lamar Willis. Retrieved June 19, 2009. [dead link]

- ^ Lawrence Kestenbaum. "Mayors of Atlanta, Georgia". The Political Graveyard. Archived from the original on February 18, 2008. Retrieved March 7, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Josh Fecht and Andrew Stevens (November 14, 2007). "Shirley Franklin: Mayor of Atlanta". City Mayors. Archived from the original on February 16, 2008. Retrieved January 27, 2008.