History of Christianity

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

The history of Christianity concerns the history of the Christian religion and the Church, from the Apostles to contemporary times. Christianity is the monotheistic religion which considers itself based on the revelation of Jesus Christ. "The Church" is understood theologically as the institution founded by Jesus for the salvation of mankind.

Life of Jesus (8–2 BC to AD 29–36)

Though the life of Jesus is a matter of academic debate, biblical scholars and historians generally agree on the following basic points: Jesus was born c. 4 B.C. and grew up in Nazareth in Galilee; his life and teachings attracted a group of followers and disciples, who regarded him as a wonderworker, exorcist, and healer; and he was executed by crucifixion in Jerusalem on orders of the Roman Governor of Iudaea Province, Pontius Pilate.[1] The main sources of information regarding Jesus' life and teachings are the four canonical Gospels and to a lesser extent the writings of Paul. Most historians think Pilate would have considered the claim to be King of the Jews and the incident against Herod's Temple to be acts of sedition[2] however the Gospels also absolve Pilate and lay the blame on the Jewish people, for example: "This was why the Jews were seeking all the more to kill him, because not only was he breaking the Sabbath, but he was even calling God his own Father, making himself equal with God." (John 5:18) See also Rejection of Jesus.

Early Christianity (33 – 312)

Early Christianity refers to the period when the religion spread in the Greco-Roman world from its beginnings as a 1st century Jewish sect[3], so-called Jewish Christianity, to the end of imperial persecution of Christians after the ascension of Constantine the Great in 313 AD. It may be divided into two distinct phases, the apostolic period, when the first apostles were alive and organizing the Church, and the post-apostolic period, when an early episcopal structure developed, whereby bishoprics were governed by bishops (overseers) via apostolic succession. Soon after its inception, Christianity acquired a distinct identity following tension between Jewish authorities and the Early Church. The name "Christian" (Greek [Χριστιανός] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) was first applied to the disciples in Antioch, as recorded in 11:26 Acts 11:26.[4] The earliest recorded use of the term Christianity (Greek [Χριστιανισμός] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) is by Ignatius of Antioch c. 107.[5]

Apostolic Church

The Apostolic Church, or Primitive Church, was the community lead by Jesus' apostles and his relatives.[6] The principal source of information for this peroid is the Acts of the Apostles, which gives a history of the Church from Pentecost and the establishment of the Jerusalem Church to the spread of the religion among the gentiles and St. Paul's imprisonment in Rome in the mid-first century.

The first Christians were essentially all ethnically Jewish or Jewish Proselytes. An early difficulty arose concerning the matter of gentile (non-Jewish, generally Greek) converts as to whether they had to "become Jewish" (be circumcised and adhere to dietary law, etc.) before becoming Christian. The decision of St. Peter, as evidenced by conversion of the Centurion Cornelius, was that they did not, hence created two distinctions within the early Church: Jewish Christians and Gentile Christians. The New Testament does not use the terms "Gentile-Christians" or "Jewish-Christians"; rather, Paul of Tarsus used the terms circumcised and uncircumcised (e.g. Colossians 3:11). The matter was further resolved with the Council of Jerusalem.

The doctrines of the apostles were considered by the Jewish religious authorities to be blasphemous, and this eventually led to the expulsion of Christians from the synagogues and the martyrdom of SS. Stephen and James the Greater. Subsequent to this expulsion, Christianity began to spread in the Greek (Hellenistic) world, rather than being limited to Palestine.

Worship of Jesus

The sources for the beliefs of the apostolic community include the Gospels and New Testament Epistles. The very earliest accounts are contained in these texts, such as early Christian creeds and hymns, as well as accounts of the Passion, the empty tomb, and Resurrection appearances; often these are dated to within a few years of the crucifixion of Jesus, originating within the Jerusalem Church.[7]

The following reconstructed points are generally agreed upon by historians and most biblical scholars, though not without debate. After his crucifixion,[8] Jesus was buried in a tomb,[9] which was later found empty;[10] subsequently, many of Jesus' followers reported encountering Jesus risen from the dead, a claim which formed the basis and impetus of the Christian faith.[11] The earliest Christian creeds and hymns express this, e.g. that preserved in 1Corinthians 15:3–4 quoted by Paul: "For what I received I passed on to you as of first importance: that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures."[12] The antiquity of the creed has been located by many scholars to less than a decade after Jesus' death, originating from the Jerusalem apostolic community,[13] and no scholar dates it later than the 40s.[14] Other relevant and very early creeds include 1John 4:2: "This is how you can recognize the Spirit of God: Every spirit that acknowledges that Jesus Christ has come in the flesh is from God;[15] 2Timothy 2:8; "Remember Jesus Christ, raised from the dead, this is my Gospel;[16] Romans 1:3–4: "regarding his Son, who as to his human nature was a descendant of David, and who through the spirit of holiness was declared with power to be the Son of God by his resurrection from the dead: Jesus Christ our Lord;[17] and 1Timothy 3:16, an early creedal hymn: "He appeared in a body, was vindicated by the Spirit, was seen by angles, was preached among the nations, was believed on in the world, was taken up in glory.[18]

Jewish Continuity

Despite the distinction of Christianity as a religion seperate from Judaism following the expulsion from the synagogues, Christianity retained a great many practices from its ancestral religion. Christianity considered the Jewish scriptures to be authoritative and sacred, employing mostly the Septuagint edition and translation as the Old Testament, and added other texts as the New Testament canon developed. Christians professed Jesus to be the One God, the God of Israel, and also considered him to be the expected Messiah or Christ. Christianity also continued many practices found in Judaism: liturgical worship, including the use of incense, an altar, a set of scriptural readings adapted from synagogue practice, use of sacred music in hymns and prayer, and a religious calendar, as well as other distinctive features such as an exclusively male priesthood, and ascetic practices (fasting etc.).

Post-Apostolic Church

The post-apostolic period concerns the time roughly after the death of the apostles (for they died at different times, of course) when bishops emerged as overseers of urban Christian populations, and continues during the time of persecutions until the legalization of Christian worship with the advent of Constantine the Great.

Persecutions

From the beginning, Christians were subject to various persecutions. This involved even death for Christians such as Stephen (Acts 7:59) and James, son of Zebedee (12:2). Larger-scale persecutions followed at the hands of the authorities of the Roman Empire, beginning with the year 64, when, as reported by the Roman historian Tacitus, the Emperor Nero blamed them for that year's great Fire of Rome. In spite of these at-times intense persecutions, the Christian religion continued its spread throughout the Mediterranean Basin.

According to church tradition, SS. Peter and Paul were both martyred in Rome under the persecution of Nero c. 64. Similarly, several of the New Testament writings mention persecutions and stress endurance through them. For 250 years Christians suffered from sporadic persecutions for their refusal to worship the Roman emperor, considered treasonous and punishable by execution.

Ecclesiastical Structure

By the late first and early second century, a hierarchical and episcopal structure becomes clearly visible; early bishops of importance are SS. Clement of Rome, Ignatius of Antioch, Polycarp of Smyrna, and Irenaeus of Lyons. This structure was based on the doctrine of Apostolic Succession where, by the ritual of the laying on of hands, a bishop becomes the spiritual successor of the previous bishop in a line tracing back to the apostles themselves. Each Christian community also had presbyters, as was the case with Jewish communities, who were also ordained and assisted the bishop; as Christianity spread, especially in rural areas, the presbyters exercised more responsibilities and took distinctive shape as priests. Lastly, deacons also performed certain duties, such as tending to the poor and sick.

Early Christian writings

As Christianity spread, it acquired certain members from well-educated circles of the Hellenistic world; they sometimes became bishops but not always. They produced two sorts of works: theological and "apologetic", the latter being works aimed at defending the faith by using reason to refute arguments against the veracity of Christianity. These authors are known as the Church Fathers, and study of them is called Patristics. Notable early Fathers include Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, Tertullian, Clement of Alexandria, Origen, etc.

Early Heresies

One of the roles of bishops, and the purpose of many Christian writings, was to refute heresies. The earliest of these were generally Christological in nature, that is, they denied either Christ's (eternal) divinity or humanity. For example, Docetism held that Jesus' humanity was merely an illusion, thus denying the incarnation; whereas Arianism held that Jesus was not eternally divine. Most of these groups were dualistic, maintaining that reality was composed into two radically opposing parts: matter, usually seen as evil, and spirit, seen as good. Orthodox Christianity, on the other hand, held that both the material and spiritual worlds were created by God and were therefore both good, and that this was represented in the unified divine and human natures of Christ.[19]

The New Testament itself speaks of the importance of maintaining orthodox doctrine and refuting heresies, showing the antiquity of the concern.[20] The development of doctrine, the position of orthodoxy, and the relationship between the early Church and early heretical groups is a matter of academic debate. Some scholars, drawing upon distinctions between Jewish Christians, Gentile Christians, and other groups such as Gnostics, see Early Christianity as fragmented and with contemporaneous competing orthodoxies.

Biblical Canon

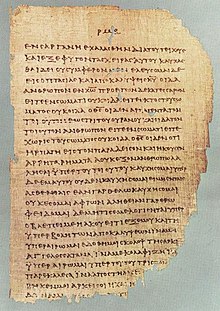

Early Christianity had no well-defined set of scriptures outside of the Septuagint. Perhaps the earliest Christian canon is the Bryennios list found in Codex Hierosolymitanus. The list is dated to around 100 by Audet.[21] By the end of the 1st century, some letters of Paul were collected and circulated, and were known to Clement of Rome (c. 96), Ignatius of Antioch (died 117), and Polycarp of Smyrna (c. 115) but they weren't usually called scripture/graphe as the Septuagint was and they weren't without critics. The Muratorian fragment shows that by 200 there existed a set of Christian writings somewhat similar to what is now the New Testament. Also in the early 200's it is claimed Origen (ca. 185-ca. 254) was using the same 27 books as in the modern New Testament, though there were still were lingering disputes over Hebrews, James, II Peter, II and III John, and Revelation.[22] In c. 160 Irenaeus of Lyons: claimed that there were exactly four Gospels, no more and no less, as a touchstone of orthodoxy.[23] He argued that it was illogical to reject Acts of the Apostles but accept the Gospel of Luke, as both were from the same author.

Early Christianity also relied on the Sacred Oral Tradition of what Jesus had said and done, as reported by the apostles and other followers. Even after the Gospels were written and began circulating, some Christians preferred the oral Gospel as told by people they trusted (e.g. Papias, c. 125).

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia article on the Canon of the New Testament:

- The idea of a complete and clear-cut canon of the New Testament existing from the beginning, that is from Apostolic times, has no foundation in history. The Canon of the New Testament, like that of the Old, is the result of a development, of a process at once stimulated by disputes with doubters, both within and without the Church, and retarded by certain obscurities and natural hesitations, and which did not reach its final term until the dogmatic definition of the Tridentine Council.

Church of the Roman Empire (313 – 476)

Christianity in Late Antiquity begins with the ascension of Constantine to the Emperorship of Rome in the early fourth century, and continues until the advent of the Middle Ages. The terminus of this period is variable because the transformation to the sub-Roman period was gradual and occurred at different times in different areas. It may generally be dated as lasting to the late sixth century and the reconquests of Justinian.

Christianity legalized

Galerius issued an edict permitting the practice of the Christian religion under his rule in April of 311.[24] In 313 Constantine I and Licinius announced toleration of Christianity in the Edict of Milan. Constantine would become the first Christian emperor. By 391, under the reign of Theodosius I, Christianity had become the state religion of Rome. Constantine I, the first emperor to embrace Christianity, was also the first emperor to openly promote the newly legalized religion.

Constantine the Great

The Emperor Constantine I was exposed to Christianity by his mother, Helena. There is scholarly controversy, however, as to whether Constantine adopted his mother's humble Christianity in his youth, or whether he adopted it gradually over the course of his life.[25]

The Christian sources record that Constantine experienced a dramatic event in 312 at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, after which Constantine would claim the emperorship in the West. Before the battle, the sources say, Constantine looked up to the sun and saw a cross of light above it, and with it the Greek words "Εν Τουτω Νικα" ("by this, conquer!", often rendered in the Latin "in hoc signo vinces"); Constantine commanded his troops to adorn their shields with a Christian symbol (the Chi-Ro), and thereafter they were victorious.[26] How much Christianity Constantine adopted at this point is difficult to discern; most influential people in the empire, especially high military officials, were still pagan, and Constantine's rule exhibited at least a willingness to appease these factions. The Roman coins minted up to eight years subsequent to the battle still bore the images of Roman gods.[27] Nonetheless, the ascension of Constantine was a turning point for the Christian Church. After his victory, Constantine supported the Church financially, built various basilicas, granted privileges (e.g. exemption from certain taxes) to clergy, promoted Christians to high ranking offices, and returned property confiscated during the Great Persecution of Diocletian.[28] Between 324 and 330, Constantine built, virtually from scratch, a new imperial capital at Byzantium on the Bosphorus (it came to be named for him: Constantinople) – the city employed overtly Christian architecture, contained churches within the city walls (unlike "old" Rome), and had no pagan temples.[29] Lastly, Constantine was baptized on his death.

Constantine also had an active role in the activity of the Church. In 313, he issued the Edict of Milan, legalizing Christian worship. In 316, he acted as a judge in a North African dispute concerning the heresy of Donatism. More significantly, in 325 he summoned the Council of Nicaea, effectively the first Ecumenical Council (unless the Council of Jerusalem is so classified), to deal mostly with the heresy of Arianism. The reign of Constantine established a precedent for the position of the Christian Emperor in the Church. Emperors considered themselves responsible to God for the spiritual health of their subjects, and thus they had a duty of maintain orthodoxy.[30] The emperor did not decide doctrine - that was the responsibility of the bishops - rather his role was to enforce doctrine, root out heresy, and uphold ecclesiastical unity.[31] The emperor ensured that God was properly worshiped in his empire; what proper worship consisted of was for the Church to determine. This precedent would continue until certain emperors of the fifth and six centuries sought to alter doctrine by imperial edit without recourse to councils, though even after this Constantine's precedent generally remained the norm.[32]

The reign of Constantine, nonetheless, does not represent a complete acceptance, or end of persecution, for Christianity in the empire. His successor in the East, Constantius II, was an Arian heretic; he kept Arian bishops at his court and installed them in various sees, expelling the orthodox bishops. Constantius's successor, Julian the Apostate, practiced a Neo-platonic and mystical form of paganism, and he sought to reinstitute paganism as the state religion, but modifying it by copying the Christian episcopal structure and adding an emphasis on public charity (hitherto unknown in Roman paganism). But his reign was short, and subsequently Christianity came to dominance; Theodosius I closed pagan temples, forbade pagan worship, and made Christianity the exclusive official state religion.[33]

Diocesan Structure

After legalization, the Church adopted the same organizational boundaries as the Empire: geographical provinces, called dioceses, corresponding to imperial governmental territorial division. The bishops, who were located in major urban centers as per pre-legalization tradition, thus oversaw each diocese. The bishop's location was his "seat", or "see"; among the sees, five held special eminence: Rome, Constantinople, Jerusalem, Antioch, and Alexandria. The prestige of these sees depended in part on their apostolic founders, from whom the bishops were therefore the spiritual successors, e.g. St. Mark as founder of the See of Alexandria, St. Peter of the See of Rome, etc. There were other significant elements: Jerusalem was the location of Christ's death and resurrection, the site of a first century council, etc., Antioch was where Jesus' followers were first called Christians, Rome was where SS. Peter and Paul had been martyred, Constantinople was the "New Rome" where Constantine had moved his capital c. 330, and, lastly, all these cities had important relics.

Papacy and primacy

The Pope is the Bishop of Rome and the office is the "papacy". As a bishopric, its origin is consistent with the development of an episcopal structure in the first century. The papacy, however, also carries the notion of primacy: that the See of Rome is preeminent amongst all other sees. The origins of this concept are historically obscure; theologically, it is based on three ancient Christian traditions: (1) that the apostle Peter was preeminent among the apostles, (2) that Peter ordained his successors for the Roman See, and (3) that the bishops are the successors of the apostles (apostolic succession). As long as the Papal See also happened to be the capital of the Western Empire, the prestige of the Bishop of Rome could be taken for granted without the need of sophisticated theological argumentation beyond these points; after its shift to Milan and then Ravenna, however, more detailed arguments were developed based on Matthew 16:18–19 etc.[34] Nonetheless, in antiquity the Petrine and Apostolic quality, as well as a "primacy of respect", concerning the Roman See went unchallenged by emperors, eastern patriarchs, and the Eastern Church alike.[35] The Ecumenical Council of Constantinople in 381 affirmed the primacy of Rome.[36] Though the appellate jurisdiction of the Pope, and the position of Constantinople, would require further doctrinal clarification, by the close of Antiquity the primacy of Rome and the sophisticated theological arguments supporting it were fully developed. Just what exactly was entailed in this primacy, and its being exercised, would become a matter of controversy at certain later times.

Ecumenical Councils

During this era, several Ecumenical Councils were convened. These were mostly concerned with Christological disputes. The two Councils of Niceaea (324, 382) condemned the Arian heresy and produced a creed (see Nicene Creed). The Council of Ephesus condemned Nestorianism and affirmed the Blessed Virgin Mary to be Theotokos ("God-bearer" or "Mother of God"). Perhaps the most significant council was the Council of Chalcedon that affirmed that Christ had two natures, fully God and fully man, distinct yet always in perfect union. This was based largely on Pope Leo the Great's Tome. Thus, it condemned Monophysitism and would be influential in refuting Monothelitism.

Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers

The early Church Fathers have already been mentioned above; however, Late Antique Christianity produced a great many renowned Fathers who wrote volumes of theological texts, including SS. Augustine, Gregory Nazianzus, Cyril of Jerusalem, Ambrose of Milan, Jerome, and others. What resulted was a golden age of literary and scholarly activity unmatched since the days of Virgil and Horace. Some of these fathers, such as John Chrysostom and Athanasius, suffered exile, persecution, or martyrdom from heretical Byzantine Emperors. Many of their writings are translated into English in the compilations of Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers.

Monasticism

Monasticism is a form of asceticism whereby one renounces worldly pursuits (in contempu mundi) and concentrates solely on heavenly and spiritual pursuits, especially by the virtues humility, poverty, and chastity. Monasticism became a distinctive practice at this time, largely due to SS. Anthony the Great, Basil the Great, and Benedict. It has roots in certain strands of Judaism, and St. John the Baptist is seen as the archtypical monk, and furthermore monasticism was also inspired by the organization of the Apostolic community as recorded in Acts of the Apostles. There are two forms of monasticism: eremetic and cenobitic. Eremetic monks, or hermits, live in solitude, whereas cenobitic monks live in communities, generally in a monastery, under a rule (or code of practice) and are governed by an abbot.

Church of the Early Middle Ages (476 – 800)

The Church in the Early Middle Ages covers the time from the deposition of the last Western Emperor in 476 and his replacement with a barbarian king, Odoacer, to the coronation of Charlemagne as "Emperor of the Romans" by Pope Leo III in Rome on Christmas Day, 800. Historians of the period have observed that imperial political control in the West gradually declined, and thus the specific date of 476 is a very artificial division. In the East, Roman imperial rule continued under the Byzantine Empire. Even in the West, distinctly Roman culture continued long afterwards; thus historians today prefer to speak of a "transformation of the Roman world" rather than a "fall of the Roman Empire". The advent of the Early Middle Ages, therefore, is a gradual and often localized process whereby, in the West, rural areas became power centers whilst urban areas declined. With the advent of Muslim invasions, the Western (Latin) and Eastern (Greek) areas of Christianity began to take on distinctive shapes, and the Bishops of Rome shifted their attention to barbarian kings rather than Byzantine Emperors.

Key dates

- 480: St Benedict sets out his Monastic Rule for the governance of monasteries

- 496: Clovis I, pagan King of the Franks, converts to the Catholic faith.

- 502: Pope Symmachus rules that laymen should no longer vote for the popes and that only higher clergy should be considered eligible.

- 529: The Justinian Code, first part of the Corpus Iuris Civilis, completed.

- January 2, 533: Mercurius becomes Pope John II, the first pope to take a regnal name.

- 553: Second Ecumenical Council of Constantinople condemned the errors of Origen, The Three Chapters, and confirmed the first four general councils.

- 590: Pope Gregory the Great reforms ecclesiastical structure and administration.

- 596: Saint Augustine of Canterbury sent by Pope Gregory to evangelize the pagan English.

- 636: Battle of Yarmouk where the Byzantine forces of Heraclius are disastrously defeated by Muslim forces, opening the East for Islamic conquest.

- 638: Christian Jerusalem and Syria conquered by Muslim armies.

- 642: Egypt falls to the Muslims, followed by the rest of North Africa.

- 664: The Synod of Whitby establishes Roman, rather than Ionan (Celtic) practice in Northumbria.

- 680: Third Ecumenical Council of Constantinople condemns Monothelitism.

- 711: Muslim armies invade Spain.

- 718: Saint Boniface, an Englishman, given commission by Pope Gregory II to evangelise the Germans.

- 726: Iconoclasm begins in the eastern Empire. The destruction of images persists until 843.

- 732: Muslim advance into Western Europe halted by Charles Martel at Poitiers, France.

- 756: Popes granted independent rule of Rome by King Pepin the Short of the Franks (the Donation of Pepin). Birth of the Papal States.

- 787: Second Ecumenical Council of Nicaea resolved Iconoclasm.

- 793: Sacking of the monastery of Lindisfarne marks the beginning of Viking raids on Christian Europe.

Developing Christianity outside the Mediterranean world

Christianity was not restricted to the Mediterranean basin and its hinterlands; at the time of Jesus a large proportion of the Jewish population lived in Mesopotamia outside the Roman Empire, especially in the city of Babylon, where much of the Talmud was developed.

- Early Insular Christianity

- Christianity comes to Ireland (traditionally dated 432) and the evolution of Celtic Christianity

- Irish missionaries and the spread of Christianity to Britain and Northern Europe

- Anglo-Saxon Christianity and the Anglo-Saxon mission to the continent in the 7th to 8th centuries.

- Nestorian Christians travel the Silk Road to establish a community in the Tang Dynasty capital of Chang'an, building the Daqin Pagoda in 640

- Christianity in Ethiopia

Italian Peninsular Warfare

Justinian, Belisarius, Lombards, &c

Islamic Jihad

Frankish Empire

Early Medieval Papacy

Church of the High Middle Ages (800 – 1499)

The High Middle Ages is the period from the coronation of Charlemagne in 800 to the close of the fifteenth century, which saw the fall of Constantinople (1453), the end of the Hundred Years War (1453), the discovery of the New World (1492), and thereafter the Protestant Reformation (1515).

- the Crusades (1095-1291)

- the Lollards (14th century)

- the Hussites (14th century)

- the Conciliar Movement (14th to 15th centuries)

- end of the Byzantine Empire in 1453

Key dates

- December 25, 800: King Charlemagne of the Franks is crowned "Emperor of the Romans" (hence inaugurating the Holy Roman Empire) by Pope Leo III in St. Peter's Basilica.

- 829: Ansgar begins missionary work in Sweden near Stockholm.

- 863: Saint Cyril and Saint Methodius sent by the Patriarch of Constantinople to evangelise the Slavic peoples. They translate the Bible into Slavonic.

- 869: Fourth Ecumenical Council of Constantinople condemns Photius. This council and succeeding general councils are denied by the Eastern Orthodox Churches.

- 910: Great Benedictine monastery of Cluny rejuvenates western monasticism. Monasteries spread throughout the isolated regions of Western Europe.

- 988: St. Vladimir I the Great is baptized; becomes the first Christian Grand Duke of Kiev.

- 1012: Burchard of Worms completes his twenty-volume Decretum of Canon law.

- July 16, 1054: Liturgical, linguistic, and political divisions cause a permanent split between the Eastern and Western Churches, known as the East-West Schism or the Great Schism. The three legates,Humbert of Mourmoutiers, Frederick of Lorraine, and Peter, archbishop of Amalfi, entered the Cathedral of the Hagia Sophia during mass on a Saturday afternoon and placed a papal Bull of Excommunication on the altar against the Patriarch Michael I Cerularius. The legates left for Rome two days later, leaving behind a city near riots.

- November 27, 1095: Pope Urban II preaches a sacrum bellum (holy war), a Crusade, to defend the eastern Christians, and pilgrims to the Holy Land, at the Council of Clermont.

- 1099: Recapture of Jerusalem by the 1st Crusade.

- 1123: First Ecumenical Lateran Council.

- 1139: Second Ecumenical Lateran Council.

- 1144: The Saint Denis Basilica of Abbot Suger is the first major building in the style of Gothic architecture.

- 1150: Publication of Decretum Gratiani.

- 1172: Establishment of papal authority in Ireland

- 1179: Third Ecumenical Lateran Council.

- October 2, 1187: The Siege of Jerusalem. Ayyubid forces led by Saladin captured Jerusalem, prompting the Third Crusade.

- January 8, 1198: Lotario de' Conti di Segni elected Pope Innocent III. Pontificate considered height of temporal power of the papacy.

- April 13, 1204: Sack of Constantinople by the Fourth Crusade. Beginning of Latin Empire of Constantinpole.

- 1205: Saint Francis of Assisi becomes a hermit, founding the Franciscan order of friars.

- June 15, 1215: Magna Carta signed by King John of England.

- 1215: Fourth Ecumenical Lateran Council. Seventy decrees were approved, among them the definition of transubstantiation.

- 1229: Inquisition founded in response to the Cathar Heresy, at the Council of Toulouse.

- 1231: Charter of the University of Paris granted by Pope Gregory IX.

- April 9, 1241: Battle at Legnickie Pole (Wahlstatt) near the city of Legnica (Liegnitz) in Silesia with a decisive victory for the Mongol diversionary force and the destruction of the combined Christian forces and death of Henry II the Pious.

- April 11, 1241: The Battle of Mohi, or Battle of the Sajó river, was the main battle between the Mongols and the Kingdom of Hungary during the Mongol invasion of Europe. Batu Khan and strategist Subotai of the Mongols defeat King Béla IV of Hungary.

- 1241: The death of Ogedei Khan, the Great Khan of the Mongols, prevented the Mongols from further advancing into Europe after their easy victories over the combined Christian armies in the Battle of Liegnitz (in present-day Poland) and Battle of Mohi (in present-day Hungary).

- 1245: First Ecumenical Council of Lyons. Excommunicated and deposed Emperor Frederick II.

- 1274: Second Ecumenical Council of Lyons. Catholic and Orthodox Churches temporarily reunited.

- February 22, 1300: Pope Boniface VIII published the Bull "Antiquorum fida relatio"; first recorded Holy Year of the Jubilee celebrated.

- November 18, 1302: Pope Boniface VIII issues the Papal bull Unam sanctam.

- 1305: French influence causes the Pope to move from Rome to Avignon.

- August 17 - 20, 1308: The leaders of the Knights Templar are secretly absolved by Pope Clement V after their interrogation was carried out by papal agents to verify claims against the accused in the castle of Chinon in the diocese of Tours.

- March 22, 1312: Clement V promulgates the Bull Vox in excelsis suppressing the Knights Templar.

- May 26, 1328: William of Ockham flees Avignon. Later, he was excommunicated by Pope John XXII, whom Ockham accused of heresy.

- 1347: The Black Death. The bubonic plague arrives in Europe.

- 1370: Saint Catherine of Siena calls on the Pope to return to Rome.

- 1378: Anti-pope Clement VII (Avignon) elected against Pope Urban VI (Rome) precipitating the Western Schism.

- 1440: Johannes Gutenberg completes his wooden printing press using moveable metal type revolutionizing the spread of knowledge by cheaper and faster means of reproduction. Results in the mass production of Bibles as well as other books.

- May 29, 1453: Fall of Constantinople.

Missions in the Eastern Europe

Though by 800 the Western Europe was entirely Christian, Eastern Europe remained an area of missionary activity. For example, in the ninth century SS. Cyril and Methodius had extensive missionary success in Eastern Europe among the Slavic peoples, translating the Bible and liturgy into Slavonic. The Baptism of Kiev in the 988 spread Christianity throughout Kievan Rus', establishing Christianity among the Ukraine, Belarus and Russia.

Investiture Contest

The Investiture Contest was a medieval dispute over which authorities, ecclesiastical or secular, could invest bishops, i.e. choose whom to fill an episcopal vacancy. Though theoretically the domain of the Church, prior to the controversy practice had been that kings or other lay officials decided whom to appoint.

Bishops collected revenues from estates attached to their bishopric. Noblemen who held lands (fiefdoms) hereditarily passed those lands on within their family. However, because bishops had no legitimate children, when a bishop died it was the king's right to appoint a successor. So, while a king had little recourse in preventing noblemen from acquiring powerful domains via inheritance and dynastic marriages, a king could keep careful control of lands under the domain of his bishops. Kings would bestow bishoprics to members of noble families whose friendship he wished to secure. Furthermore, if a king left a bishopric vacant, then he collected the estates' revenues until a bishop was appointed, when in theory he was to repay the earnings. The infrequence of this repayment was an obvious source of dispute. The Church wanted to end this lay investiture because of the potential corruption, not only from vacant sees but also from other practices such as simony. Thus, the Investiture Contest was part of the Church's attempt to reform the episcopate and provide better pastoral care.

The dispute lead to conflicts between kings such as Henry I and German Emperors such as Henry IV and Henry V, who were wont to use the political benefits of lay investiture, and reforming popes such as Gregory VII and Calixtus II. The conclusion was the Concordat of Worms (Pactum Calixtinum) – a compromise which allowed secular authorities some measure of control but granted the selection of bishops to their cathedral canons. As a symbol of the compromise, lay authorities invested bishops with their secular authority symbolized by the lance, and ecclesiastical authorities invested bishops with their spiritual authority symbolized by the ring and the staff.

Sanctification of Knighthood

The nobility of the Middle Ages was a military class; in the Early Medieval period a king (rex) attracted a band of loyal warriors (comes) and provided for them from his conquests. As the Middle Ages progressed, this system developed into a complex set of feudal ties and obligations. As Christianity had been accepted by barbarian nobility, the Church sought to prevent ecclesiastical land and clergymen, both of which came from the nobility, from embroilment in martial conflicts. By the early eleventh century, clergymen and peasants were granted immunity from violence - the Peace of God (Pax Dei). Soon the warrior elite itself became "sanctified", for example fighting was banned on holy days - the Truce of God (Treuga Dei). The concept of chivalry developed, emphasizing honor and loyalty amongst knights, and, with the advent of Crusades, holy orders of knights were established who perceived themselves as called by God to defend Christendom against Muslim advances in Spain, Italy, and the Holy Land, and pagan strongholds in Eastern Europe.

Crusades

The Crusades were a series of military conflicts conducted by Christian knights for the defense of Christians and expansion of Christian domains. Generally, the crusades refer to the campaigns in the Holy Land against Muslim forces sponsored by the Papacy. There were other crusades against Islamic forces in southern Spain, southern Italy, and Sicily, as well as the campaigns of Teutonic knights against pagan strongholds in Eastern Europe, and (to a much lesser extent) crusades within Christendom against heretical groups.

The Holy Land had been part of the Roman Empire, and thus Byzantine Empire, until the Islamic conquests of the seventh and eighth centuries. Nonetheless, Christians had generally been permitted to visit the sacred places in the Holy Land until 1071, when the Seljuk Turks closed Christian pilgrimages and assailed the Byzantines and defeating them at the Battle of Manzikert. Emperor Alexius I asked for aid from Pope Urban II (1088-1099) for help against Islamic aggression. He probably expected money from the pope for the hiring of mercenaries. Instead, Urban II called upon the knights of Christendom. On 27 November, 1095, Urban II made one of the most influential speeches in the Middle Ages at the Council of Clermont combining the ideas of making a pilgrimage to the Holy Land with that of waging a holy war against infidels. He asked the Frenchmen to turn their swords in favour of God's service, and the assembly replied "Dieu le veult!" - "God wills it!"

The First Crusade captured Antioch in 1099 and then Jerusalem. The Second Crusade occured in 1145 when Edessa was retaken by Islamic forces. Jerusalem would be held until 1187 and the Third Crusade, famous for the battles between Richard the Lionheart and Saladin. The Fourth Crusade, begun by Innocent III in 1202, intended to retake the Holy Land but was soon subverted by Venetians who used the forces to sack the Christian city of Zara. Innocent excommunicated the Venetians and crusaders. Eventually the crusaders arrived in Constantinople, but due to strife which arose between them and the Byzantines, rather than proceed to the Hold Land the crusaders instead sacked Constantinople. This was effectively the last crusade sponsored by the papacy; later crusades were sponsored by individuals. Thus, though Jerusalem was held for nearly a century and other strongholds in the Near East would remain in Christian possession much longer, the crusades in the Holy Land ultimately failed to establish permanent Christian kingdoms. Islamic expansion into Europe would renew and remain a threat for centuries culminating in the campaigns of Suleiman the Magnificent in the sixteenth century. On the other hand, the crusades in southern Spain, southern Italy, and Sicily eventually lead to the demise of Islamic power in the regions; the Teutonic knights expanded Christian domains in Eastern Europe, and the much less frequent crusades within Christendom, such as the Albigensian Crusade, achieved their goal of maintaining doctrinal unity.[37]

High Medieval Papacy

Medieval Inquisition

Rise of Universities

Mendicant Orders

East-West Schism

The East-West also called the Great Schism was between "Roman Catholicism" and "Eastern Orthodoxy". Both place great weight on apostolic succession, and historically both are descended from the early church. Each contends that it more correctly maintains the tradition of the early church and that the other has deviated. Roman Catholic Christians often prefer to refer to themselves simply as "Catholic" which means "universal", and maintain that they are also orthodox. Eastern Orthodox Christians often prefer to refer to themselves simply as "orthodox", which means "right worship", and also call themselves Catholic. Initially, the schism was primarily between East and West, but today both have congregations all over the world. They are still often referred to in those terms for historical reasons.

The East-West Schism was the event that divided Chalcedonian Christianity into Western Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy. Though normally dated to 1054, the East-West Schism was actually the result of an extended period of estrangement between the two Churches. The Church split along doctrinal, theological, linguistic, political, and geographic lines, and the fundamental breach has never been healed. The primary causes of the Schism were disputes over papal authority—the Pope claimed he held authority over the four Eastern Greek-speaking patriarchs, and over the insertion of the filioque clause into the Nicene Creed by the Western Church.

The "official" schism in 1054 was the excommunication of Patriarch Michael Cerularius of Constantinople, followed by his excommunication of the pope's representative. Attempts were made to reunite the two churches in 1274 (by the Second Council of Lyon) and in 1439 (by the Council of Basel), but in each case the councils were repudiated by the Orthodox as a whole, charging that the hierarchs had overstepped their authority in consenting to these so-called "unions". Further attempts to reconcile the two bodies have failed. The personal excommunications were mutually rescinded by the Pope and the Patriarch of Constantinople in the 1960s, although the schism is not at all healed.

Eastern Orthodox today claim that the primacy of the Patriarch of Rome was only honorary, and that he has authority only over his own diocese and does not have the authority to change the decisions of Ecumenical Councils. There were other, less significant catalysts for the Schism, including variance over liturgical practices and conflicting claims of jurisdiction.

Western Schism

Church of the Renaissance (1500 – 1521)

The Renaissance, also known as the Age of Humanism, was a period of secularization of Western civilization. The Renaissance Church became a secular institution in this period, shedding its spiritual roots, with insatiable greed for material wealth and temporal power. The Italian Renaissance produced little of what could be considered great ideas or institutions by which men living in society could be held together in harmony. Indeed, the greatest of all European institutions, the Roman Church, fell into neglect under the Renaissance popes, whose fall from spiritual grace sparked the Reformation.

The papacy that emerged from the Western Schism no longer put its energy into playing a dominant role in a united Christendom, but instead focused on building and expanding its political base in Italy. During the Renaissance, the peopes expanded the papal territories dramtiacally, most notably under Pope Alexander VI and Pope Julius II. In addition to being the head of the Church, the Pope became one of Italy's most important secular rulers , signing treaties with other sovereigns and fighting wars. In practice, though, most of the territory of the Papal States was still only nominally controlled by the Pope with much of the territory being ruled by minor princes. Control was often contested; indeedm it took until the 16th century for the Pope to have any genuine control over all his territories.

Key dates

- April 18, 1506: Pope Julius II lays cornerstone of New Basilica of St. Peter.

- 1508: Michaelangelo starts painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

- 1535: Michaelangelo starts painting the Last Judgement in the Sistine Chapel

Reconstruction of Rome

At the beginning of the fifteenth century, Rome had experienced a long decline from the glory of the Roman Empire. The skyline of the city was littered with the ruins of once spectacular structures. Wild animals ran free through the overgrowth dominating the center of the city. The city that had dominated the entire world centuries earlier was just a shadow of its former self. In the first century, Rome had a population of about one million. At the start of the fifteenth century the city held perhaps 25,000. Rome was not a great center of commerce, and the papacy, which had long sustained the city through its riches and international influence, had moved from Rome to Avignon during the fourteenth century.

In 1420, the papacy returned to Rome under Pope Martin V. During the subsequent centuries the papacy would rebuild the city, and the Papal States, centered in Rome, would assume a position of great importance in Italian affairs. The papacy closely supervised the Renaissance revival of Rome, maintaining its economic power, and thus control of the city, through the sale of church offices and taxation of the Papal States. Throughout the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, there were periodic spurts of support for political independence from church control. However, the Papacy kept a tight grip on its territorial holdings and the destinies of city and church remained inextricably intertwined.

After the return of the papacy, the first step in resurrecting Rome was the ascension of Pope Nicholas V in 1447. When he was a monk in Tuscany, Nicholas V had been helped financially by the Florentine banker Cosimo de Medici, who had lent him money without asking for collateral. As a result, Nicholas appointed Cosimo the Papal banker. Financed by the Medici family, Nicholas set about founding the Vatican library. He collected influential works of the ancient scholars from all corners of the continent. When Constantinople fell in 1453, Nicholas V purchased many of the vast number of Greek volumes left ownerless. He instilled the value of learning at the Vatican, spurring the beginning of intellectualism in Rome. In his eight short years as pope, Nicholas V initiated changes that would transform Rome into a Renaissance city.

The Papacy continued to be a force for change in Rome. However, as Rome became wealthier and more powerful, corruption in the Papacy grew. The pattern continued throughout the fifteenth century. With the election of Pope Sixtus IV in 1471, the Papacy began a plunge toward moral degradation while Rome itself ascended to the greatest splendor it had achieved since Roman times. Under Sixtus IV, nepotism reached new and corrupt heights. Sixtus' 'nephews' (the papal nephew was a long-standing way of referring to the pope's illegitimate children) were granted influential posts and huge salaries. Pope Sixtus IV even entered into a conspiracy to have the powerful Medici family assassinated when he thought they were getting in the way of one of his nephews. This patternof behavior became the model for papal rule throughout the Renaissance, undermining papal moral authority, but allowing the Papacy to grow strong politically and economically.

At the same time, Pope Sixtus IV initiated a major drive to redesign and rebuild Rome, widening the streets and destroying the crumbling ruins. He commissioned the construction of the famed Sistine Chapel and summoned many great Renaissance artists from other Italian states to work on rebuilding and redecorating Rome.

The already corrupt Papacy reached its nadir during the reign of Rodrigo Borgia, who was elected to the papacy in 1492 after the death of the generally unnoteworthy Pope Innocent VIII, and who assumed the name Pope Alexander VI. Borgia, a Spaniard, had been at the center of Vatican affairs for 30 years as a Cardinal. When he became pope, myth and legend quickly rose up around his family. Alexander VI had four acknowledged children, three males and one female. Alexander VI was himself known as a corrupt pope bent on his family's political and material success, to an even greater extent than Sixtus IV had been. It was no secret that Alexander VI's oldest son Cesare, was a murderer, and had killed many of his political opponents. Lucrezia Borgia, Alexander VI's daughter, was married three times to aid the pope's efforts to create advantageous alliances with other families. Under Alexander VI, the Papacy continued to grow strong politically and economically, but the means by which it grew were much questioned throughout Italy.

Alexander VI died in 1503, and was succeeded by Pope Julius II. Under Julius II, both the city of Rome and the Papacy entered a Golden Age. Julius II continued the consolidation of power in the Papal States, encouraged the devotion to learning and writing in Rome begun by Pope Nicholas V, and, foremost, continued the process of rebuilding Rome physically. The most prominent project among many was the rebuilding of the Basilica of St. Peter, one of the most sacred buildings in Christianity. The creation of a new St. Peter's, and indeed a new Rome, taxed the city. Ancient structures were demolished to make room and building materials for the new buildings of the city.

Rome received its final push to Renaissance glory from Pope Leo X, second son of Lorenzo de Medici who ascended to the papal throne in 1513, following Julius II. Leo X was at ease in social situations, a skilled diplomat, demonstrated great skill as an administrator, and was an intelligent and beneficent patron of the arts. He encouraged scholarly learning, and supported the theatre, an art form considered to be of ambiguous morality until that time. Most prominently, he supported the visual arts of painting and sculpture. He is well known for his patronage of Raphael, whose paintings played a large role in the redecoration of the Vatican. The death of Leo X in 1521 signalled the effective end of Rome's Golden Age, and the Renaissance as a whole began to lose its energy.

Age of Discovery (1492 – 1769)

- Conquistadors

- Santería, a fusion of Catholicism with traditional west African religious traditions originally among slaves

Key dates

- 1492: Christopher Columbus discovers the New World.

- 1493: With the Inter caetera, Pope Alexander VI awards sole colonial rights over most of the New World to Spain.

- 1519: Spanish conquest of Mexico by Hernando Cortes.

- 1521: Baptism of the first Catholics in the Philippines, the first Christian nation in Asia.

- November 16, 1532: Francisco Pizzaro captures Atahualpa. Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire

- 1769: Junípero Serra establishes Mission San Diego de Alcala, the first of the Spanish missions in California.

Inter caetera

The discovery in 1492 of supposedly Asiatic lands by Christopher Columbus threatened the unstable relations between the kingdoms of Portugal and Castile, which had been jockeying for position and possession of colonial territories along the African coast for many years. The king of Portugal asserted that the discovery was within the bounds set forth in Papal bulls of 1455, 1456, and 1479. The king and queen of Castile disputed this and sought a new Papal Bull on the subject. Pope Alexander VI, a native of Valencia and a friend of the Castilian king, responded with three bulls, dated May 3 and 4, which were highly favorable to Castile. The third of these bulls was titled "Inter caetera", awarded Spain the sole right to colonize most of the New World.

Christian missionaries

Catholic missions

During the Age of Discovery, the Roman Catholic Church established a number of Missions in the Americas and other colonies through the Augustinians, Franciscans and Dominicans in order to spread Christianity in the New World and to convert the Native Americans and other indigenous people. At the same time, missionaries such as Francis Xavier as well as other Jesuits, Augustinians, Franciscans and Dominicans were moving into Asia and the far East. The Portuguese sent missions into Africa. These are some of the most well-known missions in history. While some of these missions were associated with imperialism and oppression, others (notably Matteo Ricci's Jesuit mission to China) were relatively peaceful and focused on integration rather than cultural imperialism.

Protestant missions

The Danish government included Lutheran missionaries among the colonists in many of its colonies, Ziegenbalg in Tranquebar India in the late 17th Century. But the first organized Protestant mission work was carried out beginning in 1732 by the Moravian Brethren of Herrnhut in Saxony Germany(die evangelische Brüdergemeine).

The first missionaries landed in St. Thomas in December, 1732. Work soon was started in another Danish colony, Greenland. Within 30 years there were Moravian missionaries active on every continent, and this at a time when there were fewer than 300 people in Herrnhut. They are famous for their selfless work, living as slaves among the slaves and together with the native Americans, the Delaware and Cherokee Indian tribes. The Moravian work in South Africa inspired William Carey and the founders of the British Baptist missions.

The London Missionary Society was an extensive Anglican and Nonconformist missionary society formed in England in 1795 with missions in the islands of the South Pacific and Africa. It now forms part of the Council for World Mission. The Anglican Church Missionary Society was also founded in England in 1799, and continues its work today. These organisations spread through the extensive 18th and 19th century colonial British Empire, establishing the network of churches that largely became the modern Anglican Communion.

Reformation and Counter-Reformation (1521 – 1579)

In the early 16th century, the papacy was confronted with a challenge posed by Martin Luther to the traditional teaching on the church's doctrinal authority and too many of its practices as well. The seeming inability of Pope Leo X (1513 - 1521) and those popes who succeeded him to comprehend the significance of the threat that Luther posed - or, indeed, the alienation of many Christians by the corruption that had spread throughout the church - was a major factor in the rapid growth of the Protestant Reformation. By the time the need for a vigorous, reforming papal leadership was recognized, much of northern Europe was lost to Catholicism.

Many Catholics were troubled by the way the Church abused its power. The Church allowed the sale of indulgences (substitutes for confession that had to be bought) and allowed people to buy the titles in the church such as priest, bishop, etc. The Church even went so far as to allow people to buy more than one title, a man could be both a priest and a bishop. Luther's timely protest against the church led to the reformation. Since many people were troubled by the corruption in the Church they readily joined Luther's cause.

The four most important traditions to emerge directly from the reformation were the Lutheran tradition, the Reformed/Calvinist/Presbyterian tradition, the Anabaptist tradition, and the Anglican tradition. Subsequent Protestant traditions generally trace their roots back to these initial four schools of the Reformation. It also led to the Catholic or Counter Reformation within the Roman Catholic Church.

Mainstream Protestants generally trace their separation from the Roman Catholic Church to the 16th century, which is sometimes called the Magisterial Reformation because the movement received support from the magistrates, the ruling authorities (as opposed to the Radical Reformation, which had no state sponsorship). An older Protestant church known as the Unitas Fratrum, Unity of the Brethren, Moravian Brethren or as the Bohemian Brethren trace their origin to the time of Jan Hus in the early 15th century. As it was led by a majority of Bohemian nobles and recognized for a time by the Basel Compacts, this was the first Magisterial Reformation in Europe. In Germany a hundred years later, the protests erupted in many places at once, during a time of threatened Islamic invasion.

These protests began in earnest when Martin Luther, an Augustinian monk and professor at the university of Wittenberg, called in 1517 for reopening of the debate on the sale of indulgences. Tradition holds that he nailed his 95 Theses to the door of the Wittenberg Castle's Church, which served as a pin board for university-related announcements. Luther's dissent marked a sudden outbreak with new and irresistible force of discontent which had been pushed underground but not resolved; the quick spread of discontent occurred to a large degree because of the printing press and the resulting swift movement of both ideas and documents (such as the 95 Theses). Information was also widely disseminated in manuscript form, as well as by cheap prints and woodcuts amongst the poorer sections of society.

The Reformation foundations engaged with Augustinianism. Both Luther and Calvin thought along lines linked with the theological teachings of Augustine of Hippo. The Augustinianism of the Reformers struggled against Pelagianism, a heresy that they perceived in the Catholic church of their day. In the course of this religious upheaval, the Peasants' War of 1524-1525 swept through the Bavarian, Thuringian and Swabian principalities, leaving scores of Roman Catholics slaughtered at the hands of Protestant bands, including the Black Band of Florian Geier, a knight from Giebelstadt who joined the peasants in the general outrage against the Catholic hierarchy.

Ironically, even though both Luther and Calvin both had very similar theological teachings, Lutherans and Calvinists relationship evolved into one of conflict.

Parallel to events in Germany, a movement began in Switzerland under the leadership of Huldrych Zwingli. These two movements quickly agreed on most issues, as the recently introduced printing press spread ideas rapidly from place to place, but some unresolved differences kept them separate. Some followers of Zwingli believed that the Reformation was too conservative, and moved independently toward more radical positions, some of which survive among modern day Anabaptists. Other Protestant movements grew up along lines of mysticism or humanism (cf. Erasmus), sometimes breaking from Rome or from the Protestants, or forming outside of the churches.

After this first stage of the Reformation, following the excommunication of Luther and condemnation of the Reformation by the Pope, the work and writings of John Calvin were influential in establishing a loose consensus among various groups in Switzerland, Scotland (see Scottish Reformation), Hungary, Germany and elsewhere. The separation of the Church of England from Rome under Henry VIII, beginning in 1529 and completed in 1536, brought England alongside this broad Reformed movement. However, religious changes in the English national church proceeded more conservatively than elsewhere in Europe. Reformers in the Church of England alternated, for centuries, between sympathies for Catholic traditions and Protestantism, progressively forging a stable compromise between adherence to ancient tradition and Protestantism, which is now sometimes called the via media.

Martin Luther, John Calvin, and Ulrich Zwingli are considered Magisterial Reformers because their reform movements were supported by ruling authorities or "magistrates." "Frederick the Wise not only supported Luther, who was a professor at the university he founded, but also protected him by hiding Luther in Wartburg Castle in Eisenach. Zwingli and Calvin were supported by the city councils in Zurich and Geneva. Since the term 'magister' also means 'teacher,' the Magisterial Reformation is also characterized by an emphasis on the authority of a teacher. This is made evident in the prominence of Luther, Calvin, and Zwingli as leaders of the reform movements in their respective areas of ministry. Because of their authority, they were often criticized by Radical Reformers as being too much like the Roman Popes. For example, Radical Reformer Andreas von Bodenstein Karlstadt referred to the Wittenberg theologians as the 'new papists.'"[38]

- Martin Luther, Johann Tetzel, Philipp Melanchthon, Indulgences, 95 Theses, Nicolaus Von Amsdorf

- Exsurge Domine, Diet of Worms (1521), Peasants' War

- Huldrych Zwingli and Zürich

- John Calvin and Geneva

- John Knox and Scotland (see also Scottish Reformation)

- Radical Reformers — Müntzer, Anabaptists, Menno Simons

- Reformation in France — Huguenots, Pierre Viret

Protestant ReformationThe Protestant Reformation and Catholic Counter-Reformation are related in the following:

|

Protestantism and the Rise of Denominationalism

|

Key dates

- October 31, 1517: Martin Luther posts his 95 Theses, protesting the sale of indulgences.

- 1516: Saint Sir Thomas More publishes "Utopia" in Latin

- August 15, 1534: Saint Ignatius of Loyola and six others, including Francis Xavier met in Montmartre outside Paris to found the missionary Jesuit Order.

- October 30, 1534: English Parliament passes Act of Supremacy making the King of England Supreme Head of the Church of England. Anglican schism with Rome.

- 1536 To 1540: Dissolution of the Monasteries in England, Wales and Ireland.

- December 17, 1538: Pope Paul III excommunicates King Henry VIII of England.

- 1543: A full account of the heliocentric Copernican theory titled, On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres (De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium) is published. Considered as the start of the Scientific Revolution.

- December 13, 1545: Ecumenical Council of Trent convened during the pontificate of Paul III, to prepare the Catholic response to the Protestant Reformation. Its rulings set the tone of Catholic society for at least three centuries.

- 1568: St. John Chrysostom, St. Basil, St. Gregory Nazianzus, St. Athanasius and St. Thomas Aquinas are made Doctors of the Church.

- July 14, 1570: Pope St. Pius V issues the Apostolic Constitution on the Tridentine Mass, Quo Primum.

- October 7, 1571: Christian fleet of the Holy League defeats the Ottoman Turks in the Battle of Lepanto.

Martin Luther

In 1517, Martin Luther published his 95 Theses On the Power of Indulgences criticising the Church, including its practice of selling indulgences. He was building on work done by John Wycliffe and Jan Hus, and other reformers joined the cause. Church beliefs and practices under attack by Protestant reformers included purgatory, particular judgment, devotion to Mary, intercession of the saints, most of the sacraments, and authority of the Pope.

Biblical Canon

Luther made an attempt to remove the books of Hebrews, James, Jude and Revelation from the canon (echoing the consensus of several Catholics, also labeled Christian Humanists — such as Cardinal Ximenez, Cardinal Cajetan, and Erasmus — and partially because they were perceived to go against certain Protestant doctrines such as sola gratia and sola fide), but this was not generally accepted among his followers. However, these books are ordered last in the German-language Luther Bible to this day. [39]

Luther also eliminated the deuterocanonical books from the Catholic Old Testament, terming them "Apocrypha, that are books which are not considered equal to the Holy Scriptures, but are useful and good to read".[40] He also argued unsuccessfully for the relocation of Esther from the Canon to the Apocrypha, since without the deuterocanonical sections, it never mentions God. As a result Catholics and Protestants continue to use different canons, which differ in respect to the Old Testament.

Counter-Reformation

Not until the election (1534) of Pope Paul III, who placed the papacy itself at the head of a movement for churchwide reform, did the Counter-Reformation begin. Paul III established a reform commission, appointed several leading reformers to the College of Cardinals, initiated reform of the central administrative apparatus at Rome, authorized the founding of the Jesuits, the order that was later to prove so loyal to the papacy, and convoked the Council of Trent, which met intermittently from 1545 to 1563. The council succeeded in initiating a number of far-ranging moral and administrative reforms, including reform of the papacy itself, that was destined to define the shape and set the tone of Roman Catholicism into the mid-20th century.

The Catholic Reformation was comprehensive and comprised five major elements:

- Doctrine

- Ecclesiastical or Structural Reconfiguration

- Religious Orders

- Spiritual Movements

- Political Dimensions

Such reforms included the foundation of seminaries for the proper training of priests in the spiritual life and the theological traditions of the Church, the reform of religious life to returning orders to their spiritual foundations, and new spiritual movements focus on the devotional life and a personal relationship with Christ, including the Spanish mystics and the French school of spirituality.

The reign of Pope Paul IV (1555-1559) is associated with efforts of Catholic renewal. Paul IV is sometimes deemed the first of the Counter-Reformation popes for his resolute determination to eliminate Protestantism - and the institutional practices of the Church that contributed to its appeal. Two of his key strategies were the Inquisition and censorship of prohibited books. In this sense, his aggressive and autocratic efforts of renewal greatly reflected the strategies of earlier reform movements, especially the legalist and observantine sides: burning heretics and strict emphasis on Canon law. It also reflected the rapid pace toward absolutism that characterized the sixteenth century.

While the aggressive authoritarian approach was arguably destructive of personal religious experience, a new wave of reforms and orders conveyed a strong devotional side. Devotionalism, not subversive mysticism would provide a strong individual outlet for religious experience, especially through meditation such as the reciting of the Rosary. The devotional side of the Counter-Reformation combined two strategies of Catholic Renewal. For one, the emphasis of God as an unknowable absolute ruler - a God to be feared - coincided well with the aggressive absolutism of the papacy under Paul IV. But it also opened up new paths toward popular piety and individual religious experience.

The Papacy of St. Pius V (1566-1572) represented a strong effort not only to crack down against heretics and worldly abuses within the Church, but also to improve popular piety in a determined effort to stem the appeal of Protestantism. Pius V was trained in a solid and austere piety by the Dominicans. It is thus no surprise that he began his pontificate by giving large alms to the poor, charity, and hospitals rather than focusing on patronage. As pontiff, he practiced the virtues of a monk. Known for consoling the poor and sick, St. Pius V sought to improve the public morality of the Church, promote the Jesuits, support the Inquisition. He enforced the observance of the discipline of the Council of Trent, and supported the missions of the New World. The Spanish Inquisition, brought under the direction of the absolutist Spanish state since Ferdinand and Isabella, stemmed the growth of heresy before it could spread.

The pontificate of Pope Sixtus V (1585-1590) opened up the final stage of the Catholic Reformation characteristic of the Baroque age of the early seventeenth century, shifting away from compelling to attracting. His reign focused on rebuilding Rome as a great European capital and Baroque city, a visual symbol for the Catholic Church.

The Council of Trent

Pope Paul III (1534-1549) initiated the Council of Trent (1545-1563), a commission of cardinals tasked with institutional reform, to address contentious issues such as corrupt bishops and priests, indulgences, and other financial abuses. The Council clearly rejected specific Protestant positions and upheld the basic structure of the Medieval Church, its sacramental system, religious orders, and doctrine. It rejected all compromise with the Protestants, restating basic tenets of the Catholic faith. The Council clearly upheld the dogma of salvation appropriated by faith and works. Transubstantiation, during which the consecrated bread and wine were held to become (substantially) the body and blood of Christ, was upheld, along with the Seven Sacraments. Other practices that had been criticized Protestant reformers, such as indulgences, pilgrimages, the veneration of saints and relics, and the veneration of the Virgin Mary were strongly reaffirmed as spiritually vital as well.

But while the basic structure of the Church was reaffirmed, there were noticeable changes to answer complaints that the Counter Reformers tacitly were willing to admit were legitimate. Among the conditions to be corrected by Catholic reformers was the growing divide between the priests and the flock; many members of the clergy in the rural parishes, after all, had been poorly educated. Often, these rural priests did not know Latin and lacked opportunities for proper theological training. (Addressing the education of priests had been a fundamental focus of the humanist reformers in the past.) Parish priests now became better educated, while Papal authorities sought to eliminate the distractions of the monastic churches.

Thus, the Council of Trent was dedicated to improving the discipline and administration of the Church. The worldly excesses of the secular Renaissance church, epitomized by the era of Alexander VI (1492-1503), exploded in the Reformation under Pope Leo X (1513-1522), whose campaign to raise funds in the German states to rebuild St. Peter's Basilica by supporting sale of indulgences was a key impetus for Martin Luther's 95 Theses. But the Catholic Church would respond to these problems by a vigorous campaign of reform, inspired by earlier Catholic reform movements that predated the Council of Constance (1414-1417): humanism, devotionalism, legalist and the observatine tradition.

The Council, by virtue of its actions, repudiated the pluralism of the Secular Renaissance Church: the organization of religious institutions was tightened, discipline was improved, and the parish was emphasized. The appointment of Bishops for political reasons was no longer tolerated. In the past, the large landholdings forced many bishops to be "absentee bishops" who at times were property managers trained in administration. Thus, the Council of Trent combated "absenteeism," which was the practice of bishops living in Rome or on landed estates rather than in their dioceses. The Council of Trent also gave bishops greater power to supervise all aspects of religious life. Zealous prelates such as Milan's Archbishop Carlo Borromeo (1538-1584), later canonized as a saint, set an example by visiting the remotest parishes and instilling high standards. At the parish level, the seminary-trained clergy who took over in most places during the course of the seventeenth century were overwhelmingly faithful to the church's rule of celibacy.

Church in the Age of Reason (1580 – 1800)

Key dates

- February 24, 1582: Pope Gregory XIII issues the Bull Inter gravissimas reforming the Julian Calendar.

- October 4, 1582: The Gregorian Calendar is first adopted by Italy, Spain, and Portugal. October 4 is followed by October 15 - thus removing ten days.

- 1588: Philip II of Spain's plan to conquer England fails with the defeat of the Spanish Armada.

- 1598: Papal role in Peace of Vervins.

- April 19, 1622: Pope Gregory XV makes Armand Jean du Plessis de Richelieu a cardinal upon the nomination of King Louis XIII — becoming Cardinal Richelieu. His influence and policies greatly impact the course of European art, culture, politics, religion and war.

- 1633: Trial of Galileo.

- 1638: Shimabara Rebellion leads to a repression of Catholics, and all Christians, in Japan.

- 1655: Queen Christina of Sweden confirmed in baptism by Pope Alexander VII.

- September 12, 1683: Battle of Vienna. Decisive victory of the army of the Holy League, under King John III Sobieski of Poland, over the Ottoman Turks, under Grand Vizier Merzifonlu Kara Mustafa Pasha.

- 1685: Louis XIV revokes the Edict of Nantes in hopes of currying Papal favor.

- 1691: Pope Innocent XII declares against nepotism and simony.

- 1713: Encyclical Unigenitus condemns Jansenism.

- 1715: Clement XI rules against the Jesuits in the Chinese Rites controversy.

- 1721: Kangxi Emperor bans Christian missions in China.

- April 28, 1738: Pope Clement XII publishes the Bull In Eminenti forbidding Catholics from joining, aiding, socializing or otherwise helping in any way shape or form the organizations of Freemasonry and Freemasons under pain of excommunication.

- 1773: Suppression of the Jesuits.

- 1789: John Carroll becomes the Bishop of Baltimore, the first Roman Catholic bishop in the United States.

- 1793: French Republican Calendar and anti-clerical measures.

- 1798: Pope Pius VI taken prisoner by French revolutionaries.

Revivalism (1720 – 1906)

- Holiness movement in the U.S. and Higher Life movement in Britain

- Campbellites or Stone-Campbell Churches

- The Christian Church (Disciples of Christ)

- The Church of Christ Movement in Britain and the US

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

- Millerites

- Jehovah's Witnesses

First Great Awakening

The First Great Awakening was a wave of religious enthusiasm among Protestants that swept the American colonies in the 1730s and 1740s, leaving a permanent impact on American religion. It resulted from powerful preaching that deeply affected listeners (already church members) with a deep sense of personal guilt and salvation by Christ. Pulling away from ritual and ceremony, the Great Awakening made religion intensely personal to the average person by creating a deep sense of spiritual guilt and redemption. Historian Sydney E. Ahlstrom sees it as part of a "great international Protestant upheaval" that also created Pietism in Germany, the Evangelical Revival and Methodism in England. [41] It brought Christianity to the slaves and was an apocalyptic event in New England that challenged established authority. It incited rancor and division between the old traditionalists who insisted on ritual and doctrine and the new revivalists. It had a major impact in reshaping the Congregational, Presbyterian, Dutch Reformed, and German Reformed denominations, and strengthened the small Baptist and Methodist denominations. It had little impact on Anglicans and Quakers. Unlike the Second Great Awakening that began about 1800 and which reached out to the unchurched, the First Great Awakening focused on people who were already church members. It changed their rituals, their piety, and their self awareness.

The new style of sermons and the way people practiced their faith breathed new life into religion in America. People became passionately and emotionally involved in their religion, rather than passively listening to intellectual discourse in a detached manner. Ministers who used this new style of preaching were generally called "new lights", while the preachers of old were called "old lights". People began to study the Bible at home, which effectively decentralized the means of informing the public on religious manners and was akin to the individualistic trends present in Europe during the Protestant Reformation.

Second Great Awakening

The Second Great Awakening (1800–1830s) was the second great religious revival in United States history and consisted of renewed personal salvation experienced in revival meetings. Major leaders included Charles Grandison Finney, Lyman Beecher, Barton Stone. Peter Cartwright and James B. Finley.

In New England, the renewed interest in religion inspired a wave of social activism. In western New York, the spirit of revival encouraged the emergence of new Restorationist and other denominations, especially the Mormons and the Holiness movement. In the west especially—at Cane Ridge, Kentucky and in Tennessee—the revival strengthened the Methodists and the Baptists and introduced into America a new form of religious expression—the Scottish camp meeting.

Resurgence

The third Awakening or maybe "resurgence", from 1830, was largely influential in America and many countries worldwide including India and Ceylon. The Plymouth Brethren started with John Nelson Darby at this time, a result of disillusionment with denominationalism and clerical hierarchy.

Third Great Awakening

The next Great Awakening (sometimes called the Third Great Awakening) began from 1857 onwards in Canada and spread throughout the world including America and Australia. Significant names include Dwight L. Moody, Ira D. Sankey, William Booth and Catherine Booth (founders of the Salvation Army), Charles Spurgeon and James Caughey. Hudson Taylor began the China Inland Mission and Thomas John Barnardo founded his famous orphanages. The Keswick Convention movement began out of the British Holiness movement, encouraging a lifestyle of holiness, unity and prayer.

Further resurgence

The next Awakening (1880 - 1903) has been described as "a period of unusual evangelistic effort and success", and again sometimes more of a "resurgence" of the previous wave. Moody, Sankey and Spurgeon are again notable names. Others included Sam Jones, J. Wilber Chapman and Billy Sunday in North America, Andrew Murray in South Africa, and John McNeil in Australia. The Faith Mission began in 1886.

Welsh and Pentecostal revivals

The final Great Awakening (1904 onwards) had its roots in the Holiness movement which had developed in the late 19C. The Pentecostal revival movement began, out of a passion for more power and a greater outpouring of the Spirit. In 1902, the American evangelists Reuben Archer Torrey and Charles M. Alexander conducted meetings in Melbourne, Australia, resulting in over 8,000 converts. News of this revival travelled fast, igniting a passion for prayer and an expectation that God would work in similar ways elsewhere.

Torrey and Alexander were involved in the beginnings of the great Welsh revival (1904) which led Jessie Penn-Lewis to witness the working of Satan during times of revival, and write her book "War on the Saints". In 1906 the modern Pentecostal Movement was born in Azusa Street, in Los Angeles.

Restorationism

- See also: Dispensationalism, Restoration Movement, and Restoration

Restorationism refers to unaffiliated religious movements that attempted to transcend Protestant denominationalism and orthodox Christian creeds to restore Christianity to its original form. The term applies particularly to movements that arose in the eastern United States and Canada in the early and mid 19th century in the wake of the Second Great Awakening.