Fake news website

A request that this article title be changed to Fake news is under discussion. Please do not move this article until the discussion is closed. |

Fake news websites deliberately publish hoaxes, propaganda, and disinformation to drive web traffic inflamed by social media.[3][4][5] These sites are distinguished from news satire, as they mislead and profit from readers' gullibility.[4] Such sites promoted falsehoods concerning politics in countries: Germany,[6] Indonesia and the Philippines,[7] Sweden,[8] China,[9][10] Myanmar,[11][12] and the United States.[13][14][15] Many sites are hosted in: Russia,[5][13][14] Macedonia,[16][17] Romania,[18] and the U.S.[19][20]

One Pan-European newspaper, The Local, described the proliferation of fake news as a form of psychological warfare.[8] Agence France-Presse reported media analysts see it as damaging to democracy.[6] The European Parliament's Committee on Foreign Affairs called attention to the problem in 2016 when it passed a resolution warning that the Russian government was using "pseudo-news agencies" and Internet trolls as disinformation propaganda to weaken confidence in democratic values.[5] Pope Francis said it was a sin to spread disinformation through fake news, calling it coprophilia and consumers of the fraud engaged in coprophagia.[21][22][23]

In 2015, the Swedish Security Service, Sweden's national security agency, issued a report concluding Russia was using fake news to inflame "splits in society" through the proliferation of propaganda.[8] Sweden's Ministry of Defence tasked its Civil Contingencies Agency to combat fake news from Russia.[8] Fraudulent news affected politics in Indonesia and the Philippines, where there was simultaneously widespread usage of social media and limited resources to check the veracity of political claims.[7] German Chancellor Angela Merkel warned of the societal impact of "fake sites, bots, trolls".[6]

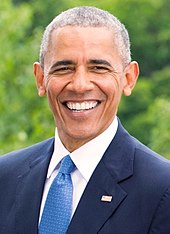

Fraudulent articles spread through social media during the 2016 U.S. presidential election.[13][14][15] Several officials within the U.S. Intelligence Community said that Russia was engaged in spreading fake news.[24] Computer security company FireEye concluded Russia used social media as cyberwarfare.[25] Google and Facebook banned fake sites from using online advertising.[26][27] U.S. President Barack Obama said a disregard for facts created a "dust cloud of nonsense".[28] Concern advanced bipartisan legislation in the U.S. Senate to authorize U.S. State Department action against foreign propaganda.[29] U.S. Senate Intelligence Committee member Ron Wyden said frustration over covert Russian propaganda in this manner was bipartisan.[29]

Definition

Fake news websites deliberately publish hoaxes, propaganda, and disinformation to drive web traffic inflamed by social media.[3][4][5] These sites are distinguished from news satire, as they mislead and profit from readers' gullibility.[4] The New York Times pointed out that within a strict definition, "fake news" referred to a fictitious article which was fabricated with the deliberate motivation to defraud readers, generally with the goal of profiting through clickbait.[30]

The New York Times noted in a December 2016 article that fake news had previously maintained a presence on the Internet and within tabloid journalism in the years prior to the 2016 U.S. election.[30] Prior to the election between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, fake news had not impacted the election process and subsequent events to such a high degree.[30] Subsequent to the 2016 election, the issue of fake news turned into a political weapon, with supporters of left-wing politics saying those on the opposite side of the spectrum spread falsehoods, and supporters of right-wing politics complaining they felt such accusations were merely a way to censor conservative views.[30] Due to these back-and-forth complaints, the definition of fake news as used for such polemics became more vague.[30]

Prominent sources

Prominent among fraudulent news sites include false propaganda created by individuals in the countries of Russia,[3][5] Macedonia,[16][17] Romania,[18] and the United States.[19][20] Several of these websites are often structured to fool visitors that they are actually real publications and mimic the stylistic appearance of ABC News and MSNBC, while other pages are specifically propaganda.[17]

Macedonia

Much fake news during the 2016 U.S. election was traced to adolescents in Macedonia.[16][31] BuzzFeed News and The Guardian separately investigated and each found teenagers in the town of Veles, Macedonia created over 100 sites spreading fraud supportive of Donald Trump.[16][32][33] The teenagers experimented with a left-wing slant about Bernie Sanders; and found fictions about Trump more popular.[32] Prior to the 2016 election the teenagers gained revenues from fake medical advice sites.[34]

One youth named Alex was interviewed by The Guardian in August 2016 and stated regardless of who won the election, fraud would remain profitable.[16] Alex explained he wrote articles by plagiarism through copy and pasting from other websites.[16] False stories netted them thousands of dollars daily and earned them on average a few thousand per month.[34]

The Associated Press (AP) tracked down an 18-year-old in Veles, and interviewed him about his tactics.[35] He used Google Analytics to assess his traffic and over one week had 650,000 views.[35] He plagiarized pro-Trump stories from a right-wing site called The Political Insider.[35] He said he did not care about politics, and published fake news to earn money and gain marketing experience.[35] He said consumers should verify what they read.[35] The AP used DomainTools to confirm the teenager was behind several fake sites, and determined there were about 200 websites tracked to Veles focused on U.S. news.[35] The AP reported the majority of fake sites were composed of plagiarism.[35] In the locality of Veles with a population of 50,000, the additional income brought in by fake sites was supported by locals, who said they were happy the youths were working.[35]

NBC News traveled to Veles in December 2016, and interviewed an 18-year-old operator of fake sites who went by the pseudonym Dmitri.[36] Dmitri was one of the most profitable fake news operators in town, and said about 300 people in Veles wrote for fake sites.[36] Dmitri said he profited over $60,000 during the six months prior — larger than both his parents' earnings.[36] During the same time period, average earnings per year for an individual in Veles was $4,800.[36] Dmitri said his main dupes were supporters of Trump.[36] He said after the 2016 U.S. election he continued to earn significant finances.[36] His two most profitable fake headlines during the 2016 election were: "JUST IN: Obama Illegally Transferred DOJ Money To Clinton Campaign!" and "BREAKING: Obama Confirms Refusal To Leave White House, He Will Stay In Power!".[36] NBC News called the influx of cash to Veles a gold rush, and noted a local nightclub scheduled an event to celebrate when Google doled out revenues to the teenagers.[36]

The mayor of Veles, Slavcho Chadiev, spoke to NBC News and said he was not bothered by the actions of the teenagers.[36] Chadiev said their actions were not illegal by Macedonian law and their finances were taxable income.[36] Chadiev said he was happy if fraud from Veles influenced the results of the 2016 U.S. election in favor of Trump.[36]

Romania

"Ending the Fed", a popular purveyor of fraudulent reports, was run by a 24-year-old named Ovidiu Drobota out of Romania, who boasted to Inc. magazine about being more popular than mainstream media.[18] Established in March 2016, "Ending the Fed" was responsible for a false story in August 2016 that incorrectly stated Fox News had fired journalist Megyn Kelly — the story was briefly prominent on Facebook on its "Trending News" section.[18] "Ending the Fed" held four out of the 10 most popular fake articles on Facebook related to the 2016 U.S. election in the prior three months before the election itself.[18] The Facebook page for the website, called "End the Feed", had 350,000 "likes" in November 2016.[18]

After being contacted by Inc. magazine, Drobota stated he was proud of the impact he had on the 2016 U.S. election in favor of his preferred candidate Donald Trump.[18] According to Alexa Internet, "Ending the Fed" garnered approximately 3.4 million views over a 30-day-period in November 2016.[18] Drobota stated the majority of incoming traffic is from Facebook.[18] He said his normal line of work before starting "Ending the Fed" included web development and search engine optimization.[18]

Russia

Internet Research Agency

Beginning in fall 2014, The New Yorker writer Adrian Chen performed a six-month investigation into Russian propaganda online by a group called the Internet Research Agency.[37] Evgeny Prigozhin, a close associate of Vladimir Putin, was behind the operation which hired hundreds of individuals to work in Saint Petersburg.[37]

The group was regarded as a "troll farm", a term used to refer to propaganda efforts controlling many accounts online with the aim of artificially providing a semblance of a grassroots organization.[37] Chen reported that Internet trolling was used by the Russian government as a tactic largely after observing the social media organization of the 2011 protests against Putin.[37] Chen interviewed Russian reporters and activists who said the end goal of fake news by the Russian government was to sew discord and chaos online.[37]

European Union response

In 2015, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe released an analysis critical of disinformation campaigns by Russia masked as news.[38] This was intended to interfere with Ukraine relations with Europe after the removal of former Ukraine president Viktor Yanukovych.[38] According to Deutsche Welle, similar tactics were used in the 2016 U.S. elections.[38] The European Union created a taskforce to deal with Russian disinformation.[5][38][39]

Foreign Policy reported the taskforce, East StratCom Team, had 11 people including Russian speakers.[40] They monitored the Internet for fake news and reported on propaganda.[40] In November 2016, the EU voted to increase the group's funding.[40]

In November 2016, the European Parliament Committee on Foreign Affairs passed a resolution warning of the use by Russia of tools including: "pseudo-news agencies ... social media and internet trolls" as disinformation to weaken democratic values.[5] The resolution requested EU analysts investigate, explaining member nations needed to be wary of disinformation.[5] The resolution condemned Russian sources for publicizing "absolutely fake" news reports.[41] The tally on 23 November 2016 passed by a margin of 304 votes to 179.[41]

Counter-Disinformation Team

The International Business Times reported the United States Department of State planned to use a unit formed with the intention of combating disinformation from the Russian government, and that it was disbanded in September 2015 after department heads missed the scope of propaganda before the 2016 U.S. election.[42] The U.S. State Department put 8 months into developing the unit before scrapping it.[42]

Titled Counter-Disinformation Team, it would have been a reboot of the Active Measures Working Group set up by the Reagan Administration.[43][44] The Counter-Disinformation Team was set up under the Bureau of International Information Programs.[43][44] Work began on the Counter-Disinformation Team in 2014, with the intention to combat propaganda from Russian sources such as Russia Today.[43][44] A beta website was ready and staff were hired by the U.S. State Department for the unit prior to its cancellation.[43][44] U.S. Intelligence officials explained to former National Security Agency analyst and counterintelligence officer John R. Schindler that the Obama Administration decided to cancel the unit as they were afraid of antagonizing Russia.[43][44] A State Department representative told the International Business Times after being contacted regarding the closure of the unit, that the U.S. was disturbed by propaganda from Russia, and the strongest defense was sincere communication.[42]

U.S. Undersecretary of State for Public Diplomacy Richard Stengel was point person for the unit before it was canceled.[43][44] Stengel previously wrote about disinformation by Russia Today.[45] After U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry called Russia Today: a "propaganda bullhorn" for Vladimir Putin,[46] Russia Today insisted the State Department give an "official response".[45][47] Stengel wrote Russia Today engaged in a "disinformation campaign".[45][47] Stengel spoke out against the spread of fake news, and explained the difference between reporting and propaganda.[45][47]

Internet trolls shift focus to Trump

Adrian Chen observed a pattern in December 2015 where pro-Russian accounts became supportive of 2016 U.S. presidential candidate Donald Trump.[3] Andrew Weisburd and Foreign Policy Research Institute fellow and senior fellow at the Center for Cyber and Homeland Security at George Washington University, Clint Watts,[48] wrote for The Daily Beast in August 2016 that Russian propaganda fabricated articles were popularized by social media.[3] Weisburd and Watts documented how disinformation spread from Russia Today and Sputnik News, "the two biggest Russian state-controlled media organizations publishing in English", to pro-Russian accounts on Twitter.[3]

Citing research by Adrian Chen, Weisburd and Watts compared Russian tactics during the 2016 U.S. election to Soviet Union Cold War strategies.[3] They referenced the 1992 United States Information Agency report to the United States Congress, which warned about Russian propaganda called active measures.[3] Weisburd and Watts concluded social media made active measures easier.[3] Institute of International Relations Prague senior fellow and scholar on Russian intelligence, Mark Galeotti, agreed the Kremlin operations were a form of active measures.[24] The Guardian reported in November 2016 the most strident Internet promoters of Trump were not U.S. citizens but paid Russian propagandists.[49] The paper estimated there were several thousand trolls involved.[49]

Weisburd and Watts collaborated with colleague J. M. Berger and published a follow-up to their Daily Beast article in online magazine War on the Rocks, titled: "Trolling for Trump: How Russia is Trying to Destroy Our Democracy".[48][50][51] They researched 7,000 pro-Trump social media accounts over a two-and-a-half year period.[50] Their research detailed Internet trolling techniques to denigrate critics of Russian activities in Syria, and to proliferate falsehoods about Clinton's health.[50] Watts said the propaganda targeted the alt-right movement, the right wing, and fascist groups.[48] BuzzFeed News reported Kremlin-financed trolls were open about spreading fake news.[52] After each presidential debate, thousands of Twitter bots used hashtag #Trumpwon to change perceptions.[52]

On 24 November 2016, The Washington Post reported the Foreign Policy Research Institute[a] stated Russian propaganda exacerbated criticism of Clinton and support for Trump.[13][14][15] The strategy involved social media, paid Internet trolls, botnets, and websites in order to denigrate Clinton.[13][14][15] Watts stated Russia's goal was to damage trust in the U.S. government.[13] Conclusions by Watts and colleagues Andrew Weisburd and J.M. Berger were confirmed by research from the Elliott School of International Affairs at George Washington University and by the RAND Corporation.[13]

In the same article, The Washington Post reported that the group PropOrNot[b] came to similar conclusions about involvement by Russia in propagating fake news during the 2016 U.S. election.[13][14] The Washington Post and PropOrNot received criticism from The Intercept,[55] Fortune,[53] Rolling Stone,[56] AlterNet,[57] Adrian Chen at The New Yorker,[54] and in an opinion piece in the paper itself, written by Katrina vanden Heuvel.[58]

U.S. intelligence analysis

Computer security company FireEye concluded Russia used social media as a weapon to influence the U.S. election.[25] FireEye Chairman David DeWalt said the 2016 operation was a new development in cyberwarfare by Russia.[25] FireEye CEO Kevin Mandia stated Russian cyberwarfare changed after fall 2014, from covert to overt tactics with decreased operational security.[25] Bellingcat analyst Aric Toler explained fact-checking only drew further attention to the fake news problem.[59]

U.S. Intelligence agencies debated why Putin chose summer 2016 to escalate active measures.[60] Prior to the election, U.S. national security officials said they anxious about Russia tampering with U.S. news.[52] Director of National Intelligence James R. Clapper said after the 2011–13 Russian protests, Putin lost self-confidence, and responded with the propaganda operation.[60] Former CIA officer Patrick Skinner said the goal was to spread uncertainty.[59] House Intelligence Committee Ranking Member Adam Schiff commented on Putin's aims, and said U.S. intelligence were concerned with Russian propaganda.[60] Speaking about disinformation that appeared in Hungary, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, and Poland, Schiff said there was an increase of the same behavior in the U.S.[60]

U.S. intelligence officials stated in November 2016 they believed Russia engaged in spreading fake news,[24] and the FBI released a statement saying they were investigating.[52]

United States

Marco Chacon created fake news site RealTrueNews to show his alt-right friends the absurdity of their gullibility.[61][62] Chacon wrote a fake transcript for Clinton's leaked speeches in which Clinton explains bronies to Goldman Sachs bankers.[61][62] Chacon was shocked when his fiction was reported as factual by Fox News and he heard his writings on Megyn Kelly's The Kelly File.[61][62] Trace Gallagher repeated Chacon's fiction and falsely reported Clinton had called Bernie Sanders supporters a "bucket of losers" — a phrase made-up by Chacon.[61] After denials from Clinton staff, Megyn Kelly apologized with a public retraction.[61][62][63]

After his fictions were believed and viewed tens of thousands of times, Chacon told Brent Bambury of CBC Radio One program Day 6 that he was so shocked at readers' ignorance he felt it was like an episode from The Twilight Zone.[63] In an interview with ABC News, Chacon defended his site, saying his was an over-the-top parody of fake sites to teach them how ridiculous they were.[64] The Daily Beast reported on the popularity of Chacon's fictions being reported as if it were factual and noted pro-Trump message boards and YouTube videos routinely believed them.[61] In a follow-up piece Chacon wrote as a contributor for The Daily Beast after the 2016 U.S. election, he concluded those most susceptible to fake news were consumers who limited themselves to partisan media outlets.[62]

Jestin Coler from Los Angeles founded Disinfomedia, a company which owns many fake news sites.[19] He gave interviews under a pseudonym, Allen Montgomery.[19] With the help of tech-company engineer John Jansen, journalists from NPR found Coler's identity.[19] Coler explained how his intent for his project backfired; he wanted to expose alt-right echo chambers, and point out their gullibility.[19] He stated his company wrote fake articles for the left-wing which were not shared as much as those from a right-wing point-of-view.[19] Coler told NPR readers must be more skeptical in order to combat fake news.[19]

Paul Horner, a creator of fraudulent news stories, told The Washington Post he made US$10,000 a month through ads linked to fake news.[20][65][66] He said he posted a fraudulent ad to Craigslist offering thousands of dollars in payment to protesters, and wrote a story based on this which was shared online by Trump's campaign manager.[20][65][66] Horner believed when the stories were exposed as false, this would reflect negatively on Trump supporters who shared them.[67] In retrospect after the election, he said he felt badly his efforts helped Trump.[67] In a follow-up interview with Rolling Stone, Horner revealed The Washington Post profile piece on him spurred increased interest with over 60 interview requests from media including ABC News, CBS News, and CBS's Inside Edition.[68] Horner explained his writing style: that articles appeared legitimate at the top and became increasingly absurd as the reader progressed.[68] Horner told Rolling Stone he always placed his name as a fictional character in his fake articles.[68] He said he supported efforts to decrease fake news websites.[68]

Impacts by country

Fake news has influenced political discourse in multiple countries, including Germany,[6] Indonesia and the Philippines,[7] Sweden,[8] China,[9][10] Myanmar,[11][12] and the United States.[3]

Australia

Australia was plagued with fake stories being shared as if they were truth on Facebook, especially regarding false news about Muslim religious practices in the country.[69] A group prominent on Facebook in the country was focused on getting rid of Halal, the Muslim laws regarding religious dietary restrictions.[69] "Boycott Halal in Australia group" had about 100,000 members on its page on Facebook in 2016.[69] The group publicized a satirical newspaper report in November 2014 and passed it off as truth.[69] Another page, for proponents of Q Society, which refers to itself as "Australia's leading Islam-critical movement", frequently posts baseless fake statements.[69]

Brazil

Brazil faced increasing influence from fake news after the 2014 re-election of President Dilma Rousseff and Rousseff's subsequent impeachment in August 2016.[69] BBC Brazil reported in April 2016 that sixty percent of the most-shared articles on Facebook about the impeachment proceedings against Rousseff were fake.[69] In 2015, reporter Tai Nalon resigned from her position at Brazilian newspaper Folha de S Paulo in order to start the first fact-checking website in Brazil, called Aos Fatos (To The Facts).[69] Nalon told The Guardian there was a great deal of fake news, and hesitated to compare the problem to that experienced in the U.S.[69]

China

Fake news during the 2016 U.S. election spread to China.[69] Articles popularized within the United States were translated into Chinese and spread within China.[69] The government of China used the growing problem of fake news as a rationale for increasing Internet censorship in China in November 2016.[70] China took the opportunity to publish an editorial in its Communist Party newspaper The Global Times called: "Western Media's Crusade Against Facebook", and criticized "unpredictable" political problems posed by freedoms enjoyed by users of Twitter, Google, and Facebook.[9] China government leaders meeting in Wuzhen at the third World Internet Conference in November 2016 said fake news in the U.S. election justified adding more curbs to free and open use of the Internet.[10] China Deputy Minister Ren Xianliang, official at the Cyberspace Administration of China, said increasing online participation led to "harmful information" and fraud.[71] Kam Chow Wong, a former Hong Kong law enforcement official and criminal justice professor at Xavier University, praised attempts in the U.S. to patrol social media.[72] The Wall Street Journal noted China's themes of Internet censorship became more relevant at the World Internet Conference due to the outgrowth of fake news.[73]

France

France saw an uptick in amounts of disinformation and propaganda, primarily in the midst of election cycles.[69] Le Monde fact-checking division "Les décodeurs" was headed by Samuel Laurent, who told The Guardian in December 2016 the upcoming French presidential election campaign in spring 2017 would face problems from fake news.[69] The country faced controversy regarding fake websites providing false information about abortion.[69] The government's lower parliamentary body moved forward with intentions to ban such fake sites.[69] Laurence Rossignol, women's minister for France, informed parliament though the fake sites look neutral, in actuality their intentions were specifically targeted to give women fake information.[69]

Germany

German Chancellor Angela Merkel lamented the problem of fraudulent news reports in a November 2016 speech, days after announcing her campaign for a fourth term as leader of her country.[6] In a speech to the German parliament, Merkel was critical of such fake sites, saying they harmed political discussion.[6] Merkel called attention to the need of government to deal with Internet trolls, bots, and fake news websites.[6] She warned that such fraudulent news websites were a force increasing the power of populist extremism.[6] Merkel called fraudulent news a growing phenomenon that might need to be regulated in the future.[6] Germany's foreign intelligence agency Federal Intelligence Service Chief, Bruno Kahl, warned of the potential for cyberattacks by Russia in the 2017 German election.[74] He said the cyberattacks would take the form of the intentional spread of misinformation.[74] Kahl said the goal is to increase chaos in political debates.[74] Germany's domestic intelligence agency Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution Chief, Hans-Georg Maassen, said sabotage by Russian intelligence was a present threat to German information security.[74]

India

India had over 50 million accounts on the smartphone instant messenger Whatsapp in 2016.[69] The country's prime minister declared in November 2016 there would be a 2,000-rupee currency bill established, and fake news went viral over Whatsapp that the note came equipped with spying technology which tracked bills 120 meters below the earth.[69] The Reserve Bank of India refuted the falsities, but not before they had spread to the country's mainstream news outlets.[69] Prabhakar Kumar of the Indian media research agency CMS, told The Guardian India was harder hit by fake news because the country lacked media policy for verification.[69] Law enforcement officers in India arrested individuals with charges of creating fictitious articles, predominantly if there is was likelihood it inflamed societal conflict.[69] The country warned supervisors of Whatsapp groups may be liable for proliferation of fake news.[69]

Indonesia and Philippines

Fraudulent news has been particularly problematic in Indonesia and the Philippines, where social media has an outsized political influence.[7] According to media analysts, developing countries with new access to social media and democracy felt the fake news problem to a larger extent.[7] In some developing countries, Facebook gives away smartphone data free of charge for Facebook and media sources, but at the same time does not provide the user with Internet access to fact-checking websites.[7]

Italy

Between October 1 and November 30, 2016, ahead of the Italian constitutional referendum, five out of ten referendum-related stories with most engagements on social media (shares, likes, and comments on Facebook, plus shares on Twitter, LinkedIn and Google+) were hoaxes or contained a misleading title.[76][77] Of the three stories with the most social media engagements, two were fake.[77] Prime Minister of Italy Matteo Renzi met with U.S. President Barack Obama and with leaders of European nations at a meeting in Berlin, Germany in November 2016, and spoke with them about the problem of fake news.[75] Renzi attempted to deal with fake news in advance of the referendum by hosting discussions on Facebook Live in an effort to rebut falsities popularized online.[76]

Propaganda grew in advance of the 4 December 2016 constitutional referendum.[69] The influence became so problematic that a senior adviser to Renzi began a defamation complaint on an anonymous Twitter user who had used the screenname "Beatrice di Maio".[69] Cyberwarfare propaganda against Renzi increased before the referendum date, and Italian newspaper La Stampa brought attention to false stories by Russia Today which wrongly asserted a pro-Renzi rally in Rome was actually an anti-Renzi rally.[69]

The Hollywood Reporter and The New York Times reported on the Five Star Movement (M5S), an Italian political party founded by Beppe Grillo, and how the party was said to manage a consortium of fake news sites amplifying support for Russian news sources, propaganda, and inflamed conspiracy theories.[75][78] The Hollywood Reporter noted Five Star Movement's site TzeTze had 1.2 million fans on Facebook and regularly shared fake news and pieces supportive of Vladimir Putin primarily cited to Russia owned sources including Sputnik News.[78] TzeTze often plagiarized the Russian source, and copied article titles and content directly from Sputnik for its articles and re-posted them.[79]

BuzzFeed News journalists tracked TzeTze, another site critical of Renzi called La Cosa, and a blog by Beppe Grillo — to the same technology company Casaleggio Associati which was started by Five Star Movement co-founder Gianroberto Casaleggio.[78] These Five Star Movement controlled sources cross-posted to each other to amplify their reach.[79] Casaleggio's son Davide Casaleggio owns and manages TzeTze and La Cosa, and medical advice website La Fucina which markets anti-vaccine conspiracy theories and medical cure-all methods.[79] BuzzFeed News discovered the Grillo blog, Five Star Movement sites, and fake news sites operated by the party use the same IP adresses, Google Analytics and Google Adsense accounts.[79] A former Google Adsense employee analyzed the investigation by BuzzFeed News and compared the network of fake news sites run by the Five Star Movement party to the Donald Trump-supportive fake news sites BuzzFeed News previously tracked to Macedonia.[79] The official stated the top members of the Five Star Movement party profited from fake news sites, and said it was akin to if Trump himself had managed fake news originating from Veles, Macedonia.[79]

In October 2016, the Five Star Movement disseminated a video from Kremlin-aligned Russia Today which falsely reported displaying thousands of individuals protesting the 4 December 2016 scheduled referendum in Italy — when in fact the video that went on to 1.5 million views was actually showing people who supported the referendum itself and were not opposed to it.[78][79] According to BuzzFeed News, the fake news sites run by Five Star Movement profit financially from the spread of such disinformation.[79] President of the Italian Chamber of Deputies, Laura Boldrini, stated: "Fake news is a critical issue and we can’t ignore it. We have to act now."[75] Boldrini met on 30 November 2016 with vice president of public policy in Europe for Facebook Richard Allan to voice concerns about fake news.[75] She said Facebook needed to admit they functioned as a media company.[75]

Myanmar

In 2015, BBC News reported on fake stories, using unrelated photographs and fraudulent captions, shared online in support of the Rohingya.[80]

Fake news negatively affected individuals in Myanmar, leading to a rise in violence against Muslims in the country.[11][12] Online participation within the country surged from a value of one percent to 20 percent of Myanmar's total populace from the period of time of 2014 to 2016.[11][12] Fake stories from Facebook were reprinted in paper periodicals called Facebook and The Internet that regurgitated the website's newsfeed text without oversight.[12] False reporting related to practitioners of Islam in the country was directly correlated with increased attacks on people of the religion in Myanmar, and protests against Muslims.[11][12] BuzzFeed News journalist Sheera Frenkel reported fake news fictitiously stated believers in Islam acted out in violence at Buddhist locations.[11][12] She documented a direct relationship between the fake news and violence against Muslim people.[11][12] Frenkel noted countries that were relatively newer to Internet exposure were more susceptible to the problem, writing people in those countries were especially vulnerable to fake news, computer hacking, and fraud.[12]

Sweden

The Swedish Security Service issued a report in 2015 identifying propaganda from Russia infiltrating Sweden with the objective to amplify pro-Russian propaganda and inflame societal conflicts.[8] The Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency (MSB), part of the Ministry of Defence of Sweden, identified fake news reports targeting Sweden in 2016 which originated from Russia.[8] Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency official Mikael Tofvesson stated a pattern emerged where views critical of Sweden were constantly repeated.[8] The Local identified these tactics as a form of psychological warfare.[8] The newspaper reported the MSB identified Russia Today and Sputnik News as significant fake news purveyors.[8] As a result of growth in this propaganda in Sweden, the MSB planned to hire six additional security officials to fight back against the campaign of fraudulent information.[8]

United States

2016 election cycle

Fraudulent stories during the 2016 U.S. presidential election popularized on Facebook included a viral post that Pope Francis had endorsed Donald Trump, and another that actor Denzel Washington "backs Trump in the most epic way possible".[83][84] Donald Trump's son and campaign surrogate Eric Trump, top national security adviser Michael T. Flynn, and then-campaign managers Kellyanne Conway and Corey Lewandowski shared fake news stories during the campaign.[67][85][81][86]

One prominent fraudulent news story released after the election—that protesters at anti-Trump rallies in Austin, Texas, were "bused in"—started as a tweet by one individual with 40 Twitter followers.[87] Over the next three days, the tweet was shared at least 16,000 times on Twitter and 350,000 times on Facebook, and promoted in the conservative blogosphere, before the individual stated that he had fabricated his assertions.[87]

U.S. President Barack Obama commented on the significant problem of fraudulent information on social networks impacting elections, in a speech the day before Election Day in 2016, saying lies repeated on social media created a "dust cloud of nonsense."[28][88] Shortly after the election, Obama again commented on the problem, saying in an appearance with German Chancellor Angela Merkel: "if we can't discriminate between serious arguments and propaganda, then we have problems."[81][82]

U.S. response to Russia in Syria

Forbes reported that the Russian state-operated newswire RIA Novosti, known as Sputnik International, reported fake news and fabricated statements by White House Press Secretary Josh Earnest.[89] RIA Novosti falsely reported on 7 December 2016 that Earnest stated sanctions for Russia were on the table related to Syria.[89] RIA Novosti falsely quoted Earnest as saying: "There are a number of things that are to be considered, including some of the financial sanctions that the United States can administer in coordination with our allies. I would definitely not rule that out."[89] Forbes analyzed Earnest's White House press briefing from that week, and found the word "sanctions" was never used by the Press Secretary.[89] Russia was discussed in eight instances during the press conference, but never about sanctions.[89] The press conference focused solely on Russian air raids in Syria towards rebels fighting President of Syria Bashar al-Assad in Aleppo.[89]

Legislative and executive responses

Members of the U.S. Senate Intelligence Committee traveled to Ukraine and Poland in March 2016 and heard from officials in both countries on Russian operations to influence their affairs.[90] U.S. Senator Angus King told the Portland Press Herald that tactics used by Russia during the 2016 U.S. election were analogous to those used against other countries.[90] King recalled the legislators were informed by officials from both Ukraine and Poland about Russian tactics of "planting fake news stories" during elections.[90] On 30 November 2016, King joined a letter in which seven members of the U.S. Senate Intelligence Committee asked President Obama to publicize more information from the intelligence community on Russia's role in the U.S. election.[90][91] In an interview with CNN, Senator King warned against ignoring the problem, saying it was a bipartisan issue.[92]

Amid worries about fake news and disinformation being spread by Russia, representatives in the U.S. Congress called for more action to track and counter alleged propaganda emanating from overseas.[29][93] On 30 November 2016, legislators approved a measure within the National Defense Authorization Act to ask the U.S. State Department act against propaganda with an inter-agency panel.[29][93] The legislation authorized funding of $160 million over a two-year-period.[29] The initiative was developed through a bipartisan bill, the Countering Foreign Propaganda and Disinformation Act, written by U.S. Senators Republican Rob Portman and Democrat Chris Murphy.[29] Portman urged more U.S. government action to counter propaganda.[29] Murphy said after the election it was apparent the U.S. needed additional tactics to fight Russian propaganda.[29] U.S. Senate Intelligence Committee member Ron Wyden said frustration over covert Russian propaganda was bipartisan.[29]

Republican U.S. Senators stated they planned to hold hearings and investigate Russian influence on the 2016 U.S. elections.[94] By doing so they went against the preference of incoming Republican President-elect Donald Trump, who downplayed any potential Russian meddling in the election.[94] U.S. Senate Armed Services Committee Chairman John McCain and U.S. Senate Intelligence Committee Chairman Richard Burr discussed plans for collaboration on investigations of Russian cyberwarfare during the election.[94] U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman Bob Corker planned a 2017 investigation.[94] Senator Lindsey Graham indicated he would conduct a sweeping investigation in the 115th U.S. Congress session.[94]

False conspiracy theories and 2016 pizzeria attack

In early November 2016, fake news sites and Internet forums falsely implicated the restaurant Comet Ping Pong and Democratic Party figures as part of a fictitious child trafficking ring, which was dubbed "Pizzagate".[95] The rumor was debunked by the Metropolitan Police Department of the District of Columbia, fact-checking website Snopes.com and The New York Times, and Fox News.[96][97][98][99] The restaurant's owners and staff were harassed and threatened on social media.[95][100] After threats, Comet Ping Pong increased security for concerts held inside its premises.[101]

On 4 December 2016, Edgar Maddison Welch of Salisbury, North Carolina, walked into the restaurant with a semi-automatic rifle, and fired one or more shots inside the building before being arrested; no one was injured.[98][102] In addition to the AR-15 style rifle, police seized a Colt .38 caliber handgun, a shotgun, and a folding knife from Welch's car and person.[98] Welch told police that he planned to "self-investigate" the conspiracy theory,[98] and was charged with assault with a dangerous weapon, carrying a pistol without a license, unlawful discharge of a firearm, and carrying a rifle or shotgun outside the home or business.[103] After the incident, future National Security Advisor Michael T. Flynn and his son Michael G. Flynn were criticized by many reporters for spreading the rumors.[104][105][106] Two days after the shooting, Trump fired Michael G. Flynn from his transition team, with The New York Times and ABC News both reporting the action by the President-Elect was directly tied to Flynn's Twitter posting of fake news.[107][108]

Days after the attack, Hillary Clinton spoke out on the dangers of fake news in a tribute speech to retiring Senator Harry Reid at the U.S. Capitol.[109][110] Clinton called the spread of fraudulent news and fabricated propaganda an epidemic that flowed through social media.[109][110] She said it posed a danger to citizens of the U.S. and to the country's political process.[109][110] Clinton said in her speech she supported bills before the U.S. Congress to deal with fake news.[109]

Response

Google CEO comment and actions

In the aftermath of the 2016 U.S. election, Google and Facebook, faced scrutiny regarding the impact of fake news.[111] The top result on Google for election results was to a fake site.[112] "70 News" had fraudulently written an incorrect headline and article that Trump won the popular vote against Clinton.[1][2][111] Google later stated that prominence of the fake site in search results was a mistake.[113] By 14 November, the "70 News" result was the second link shown when searching for results of the election.[111]

When asked shortly after the election whether fake news influenced election results, Google CEO Sundar Pichai responded: "Sure" and went on to emphasize the importance of stopping the spread of fraudulent sites.[114] On 14 November 2016, Google responded to the problem of fraudulent sites by banning such companies from profiting on advertising from traffi through its program AdSense.[26][27][111] Google previously had a policy for denying ads for dieting ripoffs and counterfeit merchandise.[115] Google stated upon the announcement they would work to ban advertisements from sources that lie about their purpose, content, or publisher.[116] This built upon an existing policy, wherein misleading advertising was already banned from Google AdSense.[111][117] The ban is not expected to apply to news satire sites like The Onion; some satirical sites may be inadvertently blocked under this new system.[111]

Facebook deliberations

Blocking fraudulent advertisers

One day after Google took action, Facebook made the decision block fake sites from advertising.[27][111] Facebook said they would ban ads from sites with deceptive content including fake news, and review publishers for compliance.[116] The steps by both Google and Facebook intended to deny ad revenue to fraudulent news sites; neither company took actions to prevent dissemination of false stories in search engine results pages or web feeds.[26][118]

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg said the notion that fraudulent news impacted the 2016 election was a "crazy idea".[119][120] Zuckerberg rejected that his website played any role in the outcome of the election, describing the idea that it might have done so as "pretty crazy".[121] In a blog post, he stated that more than 99% of content on Facebook was authentic (i.e. neither fake news nor a hoax).[122] Zuckerberg stated Facebook was not a media company.[123] Zuckerberg advised users to check the fact-checking website Snopes.com whenever they encounter fake news on Facebook.[124][125]

Top staff members at Facebook did not feel simply blocking ad revenue from fraudulent sites was a strong enough response, and they made an executive decision and created a secret group to deal with the issue themselves.[119][120] In response to Zuckerberg's first statement that fraudulent news did not impact the 2016 election, the secret Facebook group disputed this notion, saying fake news was rampant on their website during the election cycle.[119][120] BuzzFeed reported the secret task force included dozens of Facebook employees.[119][120]

Response

Facebook faced mounting criticism in the days after its decision to solely revoke advertising revenues from fraudulent news providers, and not take any further actions.[126][127] After one week of negative media coverage including assertions that the proliferation of fraudulent news on Facebook gave the 2016 U.S. presidential election to Trump, Zuckerberg posted a second time on the issue on 18 November 2016.[126][127] The post was a reversal of his earlier comments on the matter where he had discounted the impact of fraudulent news.[127]

Zuckerberg said there it was difficult to filter out fraudulent news because he wanted to maintain open communication.[126] The New York Times reported some measures being considered and not yet implemented by Facebook included ability for users to tag questionable material, automated checking tools, and third-party confirmation of news.[126] The 18 November post did not announce any concrete actions the company would definitively take, or when such measures would formally be put into usage.[126][127]

National Public Radio observed the changes being considered by Facebook to identify fraud constituted progress for the company into a new media entity.[128] On 19 November 2016, BuzzFeed advised Facebook users they could report posts from fraudulent sites.[129] Users could choose the report option: "I think it shouldn't be on Facebook", followed by: "It's a false news story."[129] In November 2016, Facebook began assessing use of warning labels on fake news.[130] The rollout was at first only available to a few users in a testing phase.[130] A sample warning read: "This website is not a reliable news source. Reason: Classification Pending".[130] TechCrunch analyzed the new feature during the testing phase and surmised it may have a tendency towards false positives.[130]

Impact

Fake news proliferation on Facebook had a negative financial impact for the company. The Economist reported revenues could decrease by two percentage points due to the concern over fake news and loss of advertising dollars.[131]

The New York Times reported shortly after Mark Zuckerberg's second statement on fake news proliferation on his website, that Facebook would engage in assisting the government of China with a version of its software in the country to allow increased censorship by the government.[132] Barron's contributor William Pesek was highly critical of this move, writing by porting its fake news conundrum to China, Facebook would become a tool in that country's president Xi Jinping's efforts to increase censorship.[132]

Fact-checking websites and journalists

Fact-checking websites play a role as debunkers to fraudulent news.[133][134][135] Fact-checkers saw increases in readership and web traffic during the 2016 U.S. election cycle.[133][134] FactCheck.org,[c] PolitiFact.com,[d] Snopes.com,[e] and "The Fact Checker" section of The Washington Post,[f] are prominent fact-checking sites that played an important role in debunking fraud.[124][133][135][141] The New Yorker writer Nicholas Lemann wrote on how to address fake news, and called for increasing the roles of FactCheck.org, PolitiFact.com, and Snopes.com, in the age of post-truth politics.[142] CNN media analyst Brian Stelter called 2016: "the year of the fact-checker."[133]

By the close of the 2016 U.S. election season, fact-checking websites FactCheck.org, PolitiFact.com, and Snopes.com, each authored guides on how to respond to fraudulent news.[4][141][143] FactCheck.org advised readers to check the source, author, date, and headline of publications.[141] They recommended their colleagues Snopes.com, The Washington Post Fact Checker, and PolitiFact.com as resources to rely on before sharing a fraudulent story.[141] FactCheck.org admonished consumers to be wary of their own biases when viewing media they agree with.[141] PolitiFact.com announced they would tag stories as "Fake news" so readers could view all stories they debunked.[143] Snopes.com warned readers social media could be used as a harmful tool by fraudsters.[4]

The Washington Post's "The Fact Checker" section increased in popularity during the 2016 election cycle.[134] The Fact Checker manager Glenn Kessler wrote all fact-checking sites had increased visitors during the 2016 election cycle.[134] Unique visitors to The Fact Checker increased five-fold from the 2012 election.[134] Kessler cited research showing fact-checks are effective at reducing falsely held views.[134] Will Moy, director of London-based fact-checking site Full Fact, said debunking must take place over a sustained period of time to be effective.[134] Full Fact began work to develop multiple products in a partnership with Google to help automate fact-checking.[144]

FactCheck.org former director Brooks Jackson remarked media companies devoted increased focus to the importance of debunking fraud during the 2016 election.[133] FactCheck.org began a partnership with CNN journalist Jake Tapper in 2016 to examine the veracity of reported claims by candidates.[133] Angie Drobnic Holan, editor of PolitiFact.com, noted the circumstances warranted support for the practice among major news media.[133] Holan was heartened that fact-checking garnered increased viewership.[133] Holan cautioned media companies chiefs must be supportive of debunking, as it often provokes hate mail and extreme responses from zealots.[133]

Society of Professional Journalists president Lynn Walsh said in November 2016 that the they would reach out to Facebook to assist weeding out fake news.[145] Walsh said Facebook should evolve and admit it functioned as a media company.[145] On 17 November 2016, the International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN)[g] published an open letter on the Poynter Institute website to Mark Zuckerberg, imploring him to utilize fact-checkers to identify fraud on Facebook.[135][148] Signatories to the 2016 letter to Zuckerberg featured a global representation of fact-checking groups, including: Africa Check, FactCheck.org, PolitiFact.com, and The Washington Post Fact Checker.[135][148] In his second post on the matter on 18 November 2016, Zuckerberg responded to the fraudulent news problem by suggesting usage of fact-checkers.[124][125] He specifically identified fact-checking website Snopes.com, and pointed out that Facebook monitors links to such debunkers in reply comments to determine which original posts were fraudulent.[124][125]

Proposed technology tools

New York magazine contributor Brian Feldman responded to an article by media communications professor Melissa Zimdars, and used her list to create a Google Chrome extension that would warn users about fraudulent news sites.[149] He invited others to use his code and improve upon it.[149]

Upworthy co-founder and The Filter Bubble author Eli Pariser launched an open-source model initiative on 17 November 2016 to address false news.[150][151] Pariser began a Google Document to collaborate with others online on how to lessen the phenomenon of fraudulent news.[150][151] Pariser called his initiative: "Design Solutions for Fake News".[150] Pariser's document included recommendations for a ratings organization analogous to the Better Business Bureau, and a database on media producers in a format like Wikipedia.[150][151] Writing for Fortune, Matthew Ingram agreed with the idea that Wikipedia could serve as a helpful model to improve Facebook's analysis of potentially fake news.[152] Ingram concluded Facebook could benefit from a social network form of fact-checking similar to Wikipedia's methods while incorporating debunking websites such as PolitiFact.com.[152]

Pope Francis

Pope Francis, the leader of the Roman Catholic Church, spoke out against fake news in an interview with the Belgian Catholic weekly Tertio on 7 December 2016.[21] The Pope had prior experience being the subject of a fake news website fiction — during the 2016 U.S. election cycle, he was falsely said to support Donald Trump for president.[21][83][84] Pope Francis said the singular worst thing the news media could do was spreading disinformation and that amplifying fake news instead of educating society was a sin.[22][153]

The Pope compared to those who spread fake news to coprophiliacs and coprophagics.[23][154] The pope said that he did not intend to offend with his strong words, but emphasized that "a lot of damage can be done" when the truth is disregarded and slander is spread.[23][154]

Academic analysis

Writing for MIT Technology Review, Jamie Condliffe said merely banning ad revenue from fraudulent sites was not enough action by Facebook to deal with the problem.[31] He wrote banning ads did not affect fraud appearing in Facebook news feeds.[31] Dartmouth College political scientist Brendan Nyhan criticized Facebook for not doing enough to reduce amplification of fake news.[155] Indiana University informatics and computer science professor Filippo Menczer commented on the steps by Google and Facebook to deny fraudulent sites advertising revenue, saying it was a good step to reduce motivation for fraudsters.[156] Menczer's research team engaged in developing an online tool titled: Hoaxy — to see the pervasiveness of unconfirmed assertions as well as related debunking on the Internet.[157]

Zeynep Tufekci wrote critically about Facebook's stance on fraudulent news sites in a piece for The New York Times, pointing out fraudulent websites in Macedonia profited handsomely off false stories about the 2016 U.S. election.[158] Tufecki wrote that Facebook's algorithms, and structure exacerbated the impact of echo chambers and increased fake news blight.[158]

Merrimack College assistant professor of media studies Melissa Zimdars wrote an article "False, Misleading, Clickbait-y and Satirical 'News' Sources" in which she advised how to determine if a fraudulent source was a fake news site.[159] Zimdars identified strange domain names, lack of attribution, poor layout, use of all caps, and URLs ending in "lo" or "com.co" as red flagss.[159] Zimdars recommended readers check the "About Us" page, and consider whether reputable news outlets reported the same story.[159]

Stanford Graduate School of Education at Stanford University education professor Sam Wineburg and colleague Sarah McGrew authored a 2016 study analyzing students' ability to discern fraudulent news from factual.[160][161] The study took place over a year-long period of time, and involved a sample size of over 7,800 responses from university, secondary and middle school students in 12 states within the United States.[160][161] They were surprised at the constancy with which students thought fraudulent news reports were factual.[160][161] The study found 82 percent of students in middle school were unable to differentiate between an advertisement denoted as sponsored content from an actual news article.[162] The authors concluded the solution was to educate online media consumers to themselves behave like fact-checkers — and actively question the veracity of all sources.[160][161]

Scientist Emily Willingham proposed applying the scientific method to fake news analysis.[163] She previously wrote on the topic of differentiating science from pseudoscience, and applied that logic to fake news.[163] Her recommended steps included: Observe, Question, Hypothesize, Analyze data, Draw conclusion, and Act on results.[163] Willingham suggested a hypothesis of "This is real news", and then forming a strong set of questions to attempt to disprove the hypothesis.[163] These tests included: check the URL, date of the article, evaluate reader bias and writer bias, double-check the evidence, and verify the sources cited.[163]

University of Connecticut philosophy professor Michael P. Lynch spoke with The New York Times and said there existed a troubling amount of individuals who make determinations relying upon the most recent piece of information they consumed, regardless of its veracity.[30] He said the greater issue was that fake news could have a negative impact on the likelihood of people to believe news that is true.[30] Lynch gave an example of the thought process of such individuals, that they believed there is no agreed upon process for them to discover objective truth, and instead simply decided to believe subjective data and disregard facts.[30]

Media commentary

Full Frontal

Full Frontal television host Samantha Bee traveled to Russia and met with Kremlin-financed trolls paid to manipulate the 2016 U.S. election in order to subvert democracy. The man and woman interviewed by Bee said they influenced the election by commenting on websites for New York Post, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, Twitter, and Facebook.[164][165][166] They kept their names covert, and maintained cover identities, with the woman claiming to be a housewife residing in Nebraska. They blamed consumers for believing all they read online.[164][165][166]

Executive producers said they relied on writer Adrian Chen, who previously reported on Russian trolls for The New York Times Magazine in 2015, as a resource to contact Russians agreeable to be interviewed. The Russian trolls wore masks and asked Full Frontal to maintain the confidentiality of their fake accounts. In order to verify they could manipulate content online, Full Frontal producers paid the trolls to utilize Twitter hashtag #SleazySam to troll the show.[166] After research in Russia for a second segment, production staff concluded Vladimir Putin supported Trump for U.S. President in order to introduce chaos into U.S. democracy.[166] Producer Razan Ghalayini explained as an authoritarian country Russia did not benefit from democracy being held up as the highest form of government.[166] Staffer Miles Kahn concurred with this analysis, adding Putin likely supported Trump, but his long term goal was disruption.[166]

On 5 December 2016, Full Frontal tracked down Disinfomedia CEO Jestin Coler, who goes by the name "Allen Montgomery" on the Internet, for an interview about his fake news business.[167][168][169] Full Frontal producer Michael Rubens conducted the interview and compared inflammatory rhetoric of fake sites to shouting fire in a crowded theater.[167] Rubens pointed out fake sites take advantage of gullible consumers in an era of post-truth politics.[169] Coler said he was a liberal Democrat who voted for Clinton, and created fake sites to expose alt-right gullibility.[167] Rubens noted Coler's fake site had a disclaimer and Coler said he was trying to educate the public on how to be smarter consumers of information.[167] He denied his fake sites led increasing Islamophobia.[168] Coler explained which fake stories garnered the most attention: "Any sort of a gun-grabbing story, pro-abortion, anti-Obama, anti-Hillary, anti-Mexican or immigrant, is kind of this right-wing red meat".[168][169]

Other media

Gleb Pavlovsky, who helped form a Russian propaganda operation, told The New York Times in August 2016 that the Kremlin saw international relations as special operations.[170] Pavlovsky said he was certain there were many groups tied to the Russian government active in fabricating fake news.[170] Peter Kreko of the Hungary-based Political Capital Institute spoke to International Business Times about his work studying Russian disinformation, and said the Obama Administration did not devote enough efforts to combating the propaganda campaign.[42] He said U.S. government officials were frustrated at the lack of action against Russian information warfare.[42]

Swedish attorney Anders Lindberg explained a common pattern of fake news distribution. He said "The dynamic is always the same: It originates somewhere in Russia, on Russia state media sites, or different websites or somewhere in that kind of context."[170] After this, Lindberg observed fake news became fodder for reporting by far-right or far-left websites, and shared onwards. He pointed out the danger was fabricated news became prominent issues in governmental security policy.[170] Deutsche Welle noted fake news was a threat to democratic societies in the U.S., Europe, and nations worldwide.[38] U.S. News & World Report warned readers to be wary of fraudulent news composed of either outright hoaxes or propaganda, and recommended the website Fake News Watch for a listing of problematic sources.[171]

Critics contended fraudulent news on Facebook may have been responsible for Donald Trump winning the 2016 U.S. presidential election, because most of the fake news Facebook allowed to spread portrayed him in a positive light.[122] Facebook is not liable for posting or publicizing fake content because, under the Communications Decency Act, interactive services cannot be held responsible for information provided by another Internet entity. Some legal scholars, like Keith Altman, think that Facebook's huge scale created such a large potential for fake news to spread that this law may need to be changed.[172] Writing for The Washington Post, Institute for Democracy in Eastern Europe co-director Eric Chenoweth wrote evidence suggested a great deal of fake news was fabricated by Russian intelligence.[173]

BuzzFeed News called the problem an epidemic.[33] According to BuzzFeed's analysis, during the 2016 U.S. elections the 20 top-performing election stories from fraudulent sites generated more shares, reactions, and comments on Facebook than the 20 top-performing stories from 19 major news outlets.[155][174] Fox News host of the meta journalism program Media Buzz, Howard Kurtz, acknowledged fraudulent news was a serious problem.[174] Kurtz relied on BuzzFeed News research for his reporting.[174] Kurtz wrote Facebook contaminated the news with junk sources.[174] Citing the BuzzFeed investigation, Kurtz pointed out factual news reporting drew less comments, reactions, and shares, than fabricated falsehoods.[174] Kurtz concluded Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg must admit the website is a media company, and get rid of charlatans, or face harm to the company's reputation.[174]

Slate magazine senior technology editor Will Oremus wrote prevalence of fake news sites obscured a wider discussion about filter bubbles.[175] Oremus expounded on his views in a follow-up article, where he criticized journalists were applying the label of fake news too broadly.[176] Abby Ohlheiser of The Washington Post echoed this view by Oremus, writing combating fake news backfired due to the difficulty over-defining it.[177]

BBC News interviewed a fraudulent news site writer who went by the pseudonym "Chief Reporter (CR)", who defended his actions and possible influence on elections. CR said increased gullibility of an electorate to believe anything they read online yields itself to increased power of fake news. He said consumers should be ready to face the impact of such gullibility.[178]

Ari Shapiro on the National Public Radio program All Things Considered interviewed The Washington Post journalist Craig Timberg, who explained a massive amount of botnets and financed Internet trolls increased the spread of fake news online.[179] Timberg said thousands of Russian social media accounts functioned as a "massive online chorus".[179] Timberg stated Russia had a vested interest in the 2016 U.S. election due to a dislike for Hillary Clinton over the 2011–13 Russian protests.[179]

On 5 December 2016 Fox News Channel's Tucker Carlson spoke with Bill McMorris of The Washington Free Beacon, who downplayed the fake news problem and said it was being used by the media to censor conservatism in the United States. McMorris stated proponents of Left-wing politics felt fake news should be defined as anything outside of their filter bubble, which was believed by adherents of right-wing politics.[180]

See also

- 2016 Democratic National Committee email leak

- Post-truth politics

- Clickbait

- Confirmation bias

- Cyberwarfare by Russia

- Democratic National Committee cyber attacks

- Disinformation

- Echo chamber (media)

- Fancy Bear

- Filter bubble

- Guccifer 2.0

- Hybrid warfare

- List of satirical news websites

- Russian espionage in the United States

- Russian propaganda

- Selective exposure theory

- Spiral of silence

- State-sponsored Internet propaganda

- Tribe (Internet)

- Trolls from Olgino

- Web brigades

Footnotes

- ^ Fortune magazine described the Foreign Policy Research Institute as: "a conservative think tank known for its generally hawkish stance on relations between the U.S. and Russia"[53]

- ^ The Washington Post and the Associated Press described PropOrNot as a nonpartisan foreign policy analysis group composed of persons with prior experience in international relations, warfare, and information technology sectors.[13][14][15] Their spokeman, interviewed by Adrian Chen of the The New Yorker said they were composed of government officials and tech company employees who were against Russian propaganda towards the U.S.[54]

- ^ FactCheck.org, a nonprofit organization and a project of the Annenberg Public Policy Center of the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania,[136] won a 2010 Sigma Delta Chi Award from the Society of Professional Journalists.[137]

- ^ PolitiFact.com, run by the Tampa Bay Times,[138] received a 2009 Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting for its fact-checking efforts the previous year.[138]

- ^ Snopes.com, privately run by Barbara and David Mikkelson, was given "high praise" by FactCheck.org, another fact-checking website;[139] in addition, Network World gave Snopes.com a grade of "A" in a meta-analysis of fact-checking websites.[140]

- ^ "The Fact Checker" is a project by The Washington Post to analyze political claims.[133] Their colleagues and competitors at FactCheck.org recommended The Fact Checker as a resource to use before assuming a story is factual.[141]

- ^ Created in September 2015, the International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN) is housed within the St. Petersburg, Florida-based Poynter Institute for Media Studies and aims to support the work of 64 member fact-checking organizations around the world.[146][147] Alexios Mantzarlis, co-founder of FactCheckEU.org and former managing editor of Italian fact-checking site Pagella Politica, was named director and editor of IFCN in September 2015.[146][147]

References

- ^ a b Bump, Philip (14 November 2016), "Google's top news link for 'final election results' goes to a fake news site with false numbers", The Washington Post, retrieved 26 November 2016

- ^ a b Jacobson, Louis (14 November 2016), "No, Donald Trump is not beating Hillary Clinton in the popular vote", PolitiFact.com, retrieved 26 November 2016

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Weisburd, Andrew; Watts, Clint (6 August 2016), "Trolls for Trump - How Russia Dominates Your Twitter Feed to Promote Lies (And, Trump, Too)", The Daily Beast, retrieved 24 November 2016

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f LaCapria, Kim (2 November 2016), "Snopes' Field Guide to Fake News Sites and Hoax Purveyors - Snopes.com's updated guide to the internet's clickbaiting, news-faking, social media exploiting dark side.", Snopes.com, retrieved 19 November 2016

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lewis Sanders IV (11 October 2016), "'Divide Europe': European lawmakers warn of Russian propaganda", Deutsche Welle, retrieved 24 November 2016

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Merkel warns against fake news driving populist gains", Yahoo! News, Agence France-Presse, 23 November 2016, retrieved 23 November 2016

- ^ a b c d e f Paul Mozur and Mark Scott (17 November 2016), "Fake News on Facebook? In Foreign Elections, That's Not New", The New York Times, retrieved 18 November 2016

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Concern over barrage of fake Russian news in Sweden", The Local, 27 July 2016, retrieved 25 November 2016

- ^ a b c Eunice Yoon and Barry Huang (22 November 2016), "China on US fake news debate: We told you so", CNBC, retrieved 28 November 2016

- ^ a b c Cadell, Catherine (19 November 2016), China says terrorism, fake news impel greater global internet curbs, retrieved 28 November 2016

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|agency=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g Read, Max (27 November 2016), "Maybe the Internet Isn't a Fantastic Tool for Democracy After All", New York Magazine, retrieved 28 November 2016

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Frenkel, Sheera (20 November 2016), "This Is What Happens When Millions Of People Suddenly Get The Internet", BuzzFeed News, retrieved 28 November 2016

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Timberg, Craig (24 November 2016), "Russian propaganda effort helped spread 'fake news' during election, experts say", The Washington Post, retrieved 25 November 2016,

Two teams of independent researchers found that the Russians exploited American-made technology platforms to attack U.S. democracy at a particularly vulnerable moment

- ^ a b c d e f g "Russian propaganda effort likely behind flood of fake news that preceded election", PBS NewsHour, Associated Press, 25 November 2016, retrieved 26 November 2016

- ^ a b c d e "Russian propaganda campaign reportedly spread 'fake news' during US election", Nine News, Agence France-Presse, 26 November 2016, retrieved 26 November 2016

- ^ a b c d e f Dan Tynan (24 August 2016), "How Facebook powers money machines for obscure political 'news' sites - From Macedonia to the San Francisco Bay, clickbait political sites are cashing in on Trumpmania – and they're getting a big boost from Facebook", The Guardian, retrieved 18 November 2016

- ^ a b c Ben Gilbert (15 November 2016), "Fed up with fake news, Facebook users are solving the problem with a simple list", Business Insider, retrieved 16 November 2016,

Some of these sites are intended to look like real publications (there are false versions of major outlets like ABC and MSNBC) but share only fake news; others are straight-up propaganda created by foreign nations (Russia and Macedonia, among others).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Townsend, Tess (21 November 2016), "Meet the Romanian Trump Fan Behind a Major Fake News Site", Inc. magazine, ISSN 0162-8968, retrieved 23 November 2016

- ^ a b c d e f g h Sydell, Laura (23 November 2016), "We Tracked Down A Fake-News Creator In The Suburbs. Here's What We Learned", All Things Considered, National Public Radio, retrieved 26 November 2016

- ^ a b c d THR staff (17 November 2016), "Facebook Fake News Writer Reveals How He Tricked Trump Supporters and Possibly Influenced Election", The Hollywood Reporter, retrieved 18 November 2016

- ^ a b c "Pope Warns About Fake News-From Experience", The New York Times, Associated Press, 7 December 2016, retrieved 7 December 2016

- ^ a b Pullella, Philip (7 December 2016), Pope warns media over 'sin' of spreading fake news, smearing politicians, retrieved 7 December 2016

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|agency=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Zauzmer, Julie (7 December 2016), "Pope Francis compares media that spread fake news to people who are excited by feces", The Washington Post, retrieved 7 December 2016

- ^ a b c Ali Watkins and Sheera Frenkel (30 November 2016), "Intel Officials Believe Russia Spreads Fake News", BuzzFeed News, retrieved 1 December 2016

- ^ a b c d Strohm, Chris (1 December 2016), "Russia Weaponized Social Media in U.S. Election, FireEye Says", Bloomberg News, retrieved 1 December 2016

- ^ a b c "Google and Facebook target fake news sites with advertising clampdown", Belfast Telegraph, 15 November 2016, retrieved 16 November 2016

- ^ a b c Shanika Gunaratna (15 November 2016), Facebook, Google announce new policies to fight fake news, CBS News, retrieved 16 November 2016

- ^ a b John Ribeiro (14 November 2016), "Zuckerberg says fake news on Facebook didn't tilt the elections", Computerworld, retrieved 16 November 2016

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Timberg, Craig (30 November 2016), "Effort to combat foreign propaganda advances in Congress", The Washington Post, retrieved 1 December 2016

- ^ a b c d e f g h Tavernise, Sabrina (7 December 2016), "As Fake News Spreads Lies, More Readers Shrug at the Truth", The New York Times, p. A1, retrieved 9 December 2016,

Narrowly defined, 'fake news' means a made-up story with an intention to deceive, often geared toward getting clicks.

- ^ a b c Jamie Condliffe (15 November 2016), "Facebook's Fake-News Ad Ban Is Not Enough", MIT Technology Review, retrieved 16 November 2016

- ^ a b Craig Silverman and Lawrence Alexander (3 November 2016), "How Teens In The Balkans Are Duping Trump Supporters With Fake News", BuzzFeed News, retrieved 16 November 2016

- ^ a b Ishmael N. Daro and Craig Silverman (15 November 2016), "Fake News Sites Are Not Terribly Worried About Google Kicking Them Off AdSense", BuzzFeed, retrieved 16 November 2016

- ^ a b Christopher Woolf (16 November 2016), Kids in Macedonia made up and circulated many false news stories in the US election, Public Radio International, retrieved 18 November 2016

- ^ a b c d e f g h In Macedonia's fake news hub, this teen shows how it's done, CBS News, 2 December 2016, retrieved 3 December 2016

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|agency=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Alexander Smith and Vladimir Banic (9 December 2016), "Fake News: How a Partying Macedonian Teen Earns Thousands Publishing Lies", NBC News, retrieved 9 December 2016

- ^ a b c d e Chen, Adrian (27 July 2016), "The Real Paranoia-Inducing Purpose of Russian Hacks", The New Yorker, retrieved 26 November 2016

- ^ a b c d e Lewis Sanders IV (17 November 2016), "Fake news: Media's post-truth problem", Deutsche Welle, retrieved 24 November 2016

- ^ European Parliament Committee on Foreign Affairs (23 November 2016), "MEPs sound alarm on anti-EU propaganda from Russia and Islamist terrorist groups" (PDF), European Parliament, retrieved 26 November 2016

- ^ a b c Surana, Kavitha (23 November 2016), "The EU Moves to Counter Russian Disinformation Campaign", Foreign Policy, ISSN 0015-7228, retrieved 24 November 2016

- ^ a b "EU Parliament Urges Fight Against Russia's 'Fake News'", Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, Agence France-Presse and Reuters, 23 November 2016, retrieved 24 November 2016

- ^ a b c d e Porter, Tom (28 November 2016), "How US and EU failings allowed Kremlin propaganda and fake news to spread through the West", International Business Times, retrieved 29 November 2016

- ^ a b c d e f Schindler, John R. (5 November 2015), "Obama Fails to Fight Putin's Propaganda Machine", New York Observer, retrieved 28 November 2016

- ^ a b c d e f Schindler, John R. (26 November 2016), "The Kremlin Didn't Sink Hillary—Obama Did", New York Observer, retrieved 28 November 2016

- ^ a b c d LoGiurato, Brett (29 April 2014), "Russia's Propaganda Channel Just Got A Journalism Lesson From The US State Department", Business Insider, retrieved 29 November 2016

- ^ LoGiurato, Brett (25 April 2014), "RT Is Very Upset With John Kerry For Blasting Them As Putin's 'Propaganda Bullhorn'", Business Insider, retrieved 29 November 2016

- ^ a b c Stengel, Richard (29 April 2014), "Russia Today's Disinformation Campaign", Dipnote, United States Department of State, retrieved 28 November 2016

- ^ a b c Dougherty, Jill (2 December 2016), The reality behind Russia's fake news, CNN, retrieved 2 December 2016

- ^ a b Benedictus, Leo (6 November 2016), "Invasion of the troll armies: from Russian Trump supporters to Turkish state stooges", The Guardian, retrieved 2 December 2016

- ^ a b c "U.S. officials defend integrity of vote, despite hacking fears", WITN-TV, 26 November 2016, retrieved 2 December 2016

- ^ Andrew Weisburd, Clint Watts and JM Berger (6 November 2016), "Trolling for Trump: How Russia is Trying to Destroy Our Democracy", War on the Rocks, retrieved 6 December 2016

- ^ a b c d Frenkel, Sheera (4 November 2016), "US Officials Are More Worried About The Media Being Hacked Than The Ballot Box", BuzzFeed News, retrieved 2 December 2016

- ^ a b Ingram, Matthew (25 November 2016), "No, Russian Agents Are Not Behind Every Piece of Fake News You See", Fortune magazine, retrieved 27 November 2016

- ^ a b "The Propaganda About Russian Propaganda". The New Yorker. 1 December 2016. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- ^ Ben Norton; Glenn Greenwald (26 November 2016), "Washington Post Disgracefully Promotes a McCarthyite Blacklist From a New, Hidden, and Very Shady Group", The Intercept, retrieved 27 November 2016

- ^ Taibbi, Matt (28 November 2016), "The 'Washington Post' 'Blacklist' Story Is Shameful and Disgusting", Rolling Stone, retrieved 30 November 2016

- ^ Blumenthal, Max (25 November 2016). "Washington Post Promotes Shadowy Website That Accuses 200 Publications of Being Russian Propaganda Plants". AlterNet. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- ^ vanden Heuvel, Katrina (29 November 2016), "Putin didn't undermine the election. We did.", The Washington Post, retrieved 1 December 2016

- ^ a b Schatz, Bryan, "The Kremlin Would Be Proud of Trump's Propaganda Playbook", Mother Jones, retrieved 2 December 2016

- ^ a b c d "Vladimir Putin Wins the Election No Matter Who The Next President Is", The Daily Beast, 4 November 2016, retrieved 2 December 2016

- ^ a b c d e f g Collins, Ben (28 October 2016), "This 'Conservative News Site' Trended on Facebook, Showed Up on Fox News—and Duped the World", The Daily Beast, retrieved 27 November 2016

- ^ a b c d e f Chacon, Marco (21 November 2016), "I've Been Making Viral Fake News for the Last Six Months. It's Way Too Easy to Dupe the Right on the Internet.", The Daily Beast, retrieved 27 November 2016

- ^ a b c Bambury, Brent (25 November 2016), "Marco Chacon meant his fake election news to be satire — but people took it as fact", Day 6, CBC Radio One, retrieved 27 November 2016

- ^ Chang, Juju (29 November 2016), When Fake News Stories Make Real News Headlines, ABC News, retrieved 29 November 2016

- ^ a b McAlone, Nathan (17 November 2016), "This fake-news writer says he makes over $10,000 a month, and he thinks he helped get Trump elected", Business Insider, retrieved 18 November 2016

- ^ a b Goist, Robin (17 November 2016), "The fake news of Facebook", The Plain Dealer, retrieved 18 November 2016

- ^ a b c Dewey, Caitlin (17 November 2016), "Facebook fake-news writer: 'I think Donald Trump is in the White House because of me'", The Washington Post, ISSN 0190-8286, retrieved 17 November 2016

- ^ a b c d Hedegaard, Erik (29 November 2016), "How a Fake Newsman Accidentally Helped Trump Win the White House - Paul Horner thought he was trolling Trump supporters – but after the election, the joke was on him", Rolling Stone, retrieved 29 November 2016

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Kate Connolly, Angelique Chrisafis, Poppy McPherson, Stephanie Kirchgaessner, Benjamin Haas , Dominic Phillips, and Elle Hunt (2 December 2016), "Fake news: an insidious trend that's fast becoming a global problem - With fake online news dominating discussions after the US election, Guardian correspondents explain how it is distorting politics around the world", The Guardian, retrieved 2 December 2016