Scythians

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

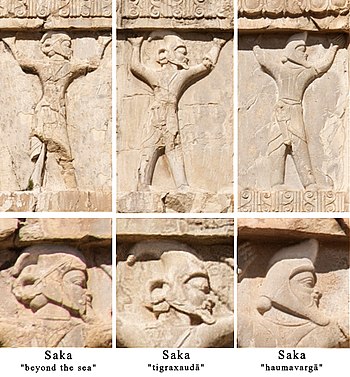

The Scythians (/ˈsɪθiən, ˈsɪð-/; from Greek Σκύθης, Σκύθοι), also known as Scyth, Saka, Sakae, Iskuzai, or Askuzai, were a nomadic people who dominated the Pontic steppe from about the 7th century BC up until the 3rd century BC.[1] They were part of the wider Scythian cultures, stretching across the Eurasian Steppe, which included many peoples that are distinguished from the Scythians. Because of this, a broad concept referring to all early Eurasian nomads as "Scythians" has sometimes been used.[2][3] Within this concept, the actual Scythians are variously referred to as Classical Scythians, European Scythians, Pontic Scythians, or Western Scythians. Use of the term "Scythians" for all early Eurasian nomads has however led to much confusion in literature,[2] and the validity of such terminology is controversial. Other names for that concept are therefore preferable.[4]

The Scythians are generally believed to have been of Iranian origin.[5] They spoke a language of the Scythian branch of the Eastern Iranian languages,[6] and practiced a variant of ancient Iranian religion.[7] Among the earliest peoples to master mounted warfare,[8] the Scythians replaced the Cimmerians as the dominant power on the Pontic Steppe in the 8th century BC.[9] During this time they and related peoples came to dominate the entire Eurasian Steppe from the Carpathian Mountains in the west to Ordos Plateau in the east,[10][11] creating what has been called the first Central Asian nomadic empire.[9][12] Based in what is modern-day Ukraine and southern Russia, the Scythians were led by a nomadic warrior aristocracy known as the Royal Scythians, who called themselves Scoloti.

In the 7th century BC, the Scythians crossed the Caucasus and frequently raided the Middle East along with the Cimmerians, playing an important role in the political developments of the region.[9][12] Around 650–630 BC, Scythians briefly dominated the Medes of the western Iranian Plateau,[13][14] stretching their power to the borders of Egypt.[8] After losing control over Media, the Scythians continued intervening in Middle Eastern affairs, playing a leading role in the destruction of the Assyrian Empire in the Sack of Nineveh in 612 BC. The Scythians subsequently engaged in frequent conflicts with the Achaemenid Empire. The Scythians suffered a major defeat against Macedonia in the 4th century BC[8] and were subsequently gradually conquered by the Sarmatians, a related Iranian people living to their east.[15] In the late 2nd century BC, their capital at Scythian Neapolis in the Crimea was captured by Mithradates VI and their territories incorporated into the Bosporan Kingdom.[7] By this time they had been largely Hellenized. By the 3rd century AD, the Sarmatians and last remnants of the Scythians were dominated by the Alans, and were being overwhelmed by the Goths. By the early Middle Ages, the Scythians and the Sarmatians had been largely assimilated and absorbed by early Slavs.[16][17] The Scythians were instrumental in the ethnogenesis of the Ossetians, who are believed to be descended from the Alans.[18]

The Scythians played an important part in the Silk Road, a vast trade network connecting ancient Greece, Persia, India, and China, perhaps contributing to the contemporary flourishing of those civilisations.[19] Settled metalworkers made portable decorative objects for the Scythians. These objects survive mainly in metal, forming a distinctive Scythian art.[20]

The name of the Scythians survived in the region of Scythia. Early authors continued to use the term "Scythian", applying it to many later nomadic groups unrelated to Scythians who appeared in Scythia in later centuries.[21][7]

Names

Etymology

Oswald Szemerényi studied the various words for Scythian and gave the following: Skuthes Σκύθης, Skudra, Sug(u)da, and Saka.[22]

- The first three descend from the Indo-European root *(s)kewd-, meaning "propel, shoot" (cognate with English shoot). *skud- is the zero-grade form of the same root. Szemerényi restores the Scythians' self-name as *skuda (roughly "archer"). This yields the Ancient Greek Skuthēs Σκύθης (plural Skuthai Σκύθαι) and Assyrian Aškuz; Old Armenian: սկիւթ skiwtʰ is from itacistic Greek. A late Scythian sound change from /d/ to /l/ gives the Greek word Skolotoi (Σκώλοτοι, Herodotus 4.6), from Scythian *skula which, according to Herodotus, was the self-designation of the Royal Scythians. Other sound changes gave Sogdia.

- The form reflected in Old Persian: Sakā, Greek: Σάκαι; Latin: Sacae, Sanskrit: शक Śaka comes from an Iranian verbal root sak-, "go, roam" and thus means "nomad".[23]

Exonyms

The name Scythian is derived from the name used for them by the ancient Greeks.[24] Iskuzai or Askuzai was the name given them by the Assyrians. The ancient Persians used the term Saka for all nomads of the Eurasian Steppe, including the Scythians.[25]

Ethnonyms

Herodotus said the ruling class of the Scythians, whom he referred to as the Royal Scythians, called themselves Skolotoi.[2]

Modern terminology

In scholarship, the term Scythians generally refers to the nomadic Iranian people who dominated the Pontic steppe from the 7th century BC to the 3rd century BC.[1]

The Scythians share several cultural similarities with other populations living to their east, in particular similar weapons, horse gear, and Scythian art, which has been referred to as the Scythian triad.[2][4] Cultures sharing these characteristics have often been referred to as Scythian cultures, and its peoples called Scythians.[3][26] Peoples associated with Scythian cultures include not only the Scythians themselves, who were a distinct ethnic group,[27] but also Cimmerians, Massagetae, Saka, Sarmatians, and various obscure peoples of the forest steppe,[2][3] such as early Slavs, Balts, and Finno-Ugric peoples.[25][28] Within this broad definition of the term Scythian, the actual Scythians have often been distinguished from other groups through the terms Classical Scythians, Western Scythians, European Scythians or Pontic Scythians.[3]

Scythologist Askold Ivantchik notes with dismay that the term "Scythian" has been used within both a broad and a narrow context, leading to a good deal of confusion. He reserves the term "Scythian" for the Iranian people dominating the Pontic steppe from the 7th century BC to the 3rd century BC.[2] Nicola Di Cosmo writes that the broad concept of "Scythian" is "too broad to be viable", and that the term "early nomadic" is preferable.[4]

History

Origins

Literary evidence

The Scythians first appeared in the historical record in the 8th century BC.[22] Herodotus reported three contradictory versions as to the origins of the Scythians, but placed greatest faith in this version:[29]

There is also another different story, now to be related, in which I am more inclined to put faith than in any other. It is that the wandering Scythians once dwelt in Asia, and there warred with the Massagetae, but with ill success; they therefore quitted their homes, crossed the Araxes, and entered the land of Cimmeria.

Herodotus presented four different versions of Scythian origins:

- Firstly (4.7), the Scythians' legend about themselves, which portrays the first Scythian king, Targitaus, as the child of the sky-god and of a daughter of the Dnieper. Targitaus allegedly lived a thousand years before the failed Persian invasion of Scythia, or around 1500 BC. He had three sons, before whom fell from the sky a set of four golden implements – a plough, a yoke, a cup, and a battle-axe. Only the youngest son succeeded in touching the golden implements without them bursting with fire, and this son's descendants, called by Herodotus the "Royal Scythians", continued to guard them.

- Secondly (4.8), a legend told by the Pontic Greeks featuring Scythes, the first king of the Scythians, as a child of Hercules and Echidna.

- Thirdly (4.11), in the version which Herodotus said he believed most, the Scythians came from a more southern part of Central Asia, until a war with the Massagetae (a powerful tribe of steppe nomads who lived just northeast of Persia) forced them westward.

- Finally (4.13), a legend which Herodotus attributed to the Greek bard Aristeas, who claimed to have got himself into such a Bacchanalian fury that he ran all the way northeast across Scythia and further. According to this, the Scythians originally lived south of the Rhipaean mountains, until they got into a conflict with a tribe called the Issedones, pressed in their turn by the "one-eyed Arimaspians"; and so the Scythians decided to migrate westwards.

Accounts by Herodotus of Scythian origins has been discounted recently; although his accounts of Scythian raiding activities contemporary to his writings have been deemed more reliable.[30]

Archaeological evidence

Modern interpretation of historical, archaeological, and anthropological evidence has proposed two broad hypotheses on Scythian origins.[31]

The first hypothesis, formerly more espoused by Soviet and then Russian researchers, roughly followed Herodotus' (third) account, holding that the Scythians were an Eastern Iranian-speaking group who arrived from Inner Asia, i.e. from the area of Turkestan and western Siberia. [31]

The second hypothesis, according to Roman Ghirshman and others, proposes that the Scythian cultural complex emerged from local groups of the Srubna culture at the Black Sea coast,[31] although this is also associated with the Cimmerians. According to Pavel Dolukhanov this proposal is supported by anthropological evidence which has found that Scythian skulls are similar to preceding findings from the Srubna culture, and distinct from those of the Central Asian Saka.[32] Yet, according to J. P. Mallory, the archaeological evidence is poor, and the Andronovo culture and "at least the eastern outliers of the Timber-grave culture" may be identified as Indo-Iranian.[31]

Genetic evidence

In 2017, a genetic study of the Scythians suggested that the Scythians were ultimately descended from the Yamna culture, and emerged on the Pontic steppe independently of peoples belonging to Scythian cultures further east.[3] Based on the analysis of mithocondrial lineages, another later 2017 study suggested that the Scythians were directly descended from the Srubnaya culture.[33] A later analysis of paternal lineages, published in 2018, found significant genetic differences between the Srubnaya and the Scythians, suggesting that the Srubnaya and the Scythians instead traced a common origin in the Yamnaya culture, with the Scythians and related peoples such as the Sarmatians perhaps tracing their origin to the eastern Pontic-Caspian steppes and the southern Urals.[34] Another 2019 study also concluded that migrations must have played a part in the emergence of the Scythians as the dominant power of the Pontic steppe.[35]

Early history

Herodotus provides the first detailed description of the Scythians. He classes the Cimmerians as a distinct autochthonous tribe, expelled by the Scythians from the northern Black Sea coast (Hist. 4.11–12). Herodotus also states (4.6) that the Scythians consisted of the Auchatae, Catiaroi, Traspians, and Paralatae or "Royal Scythians".

In the early 7th century BC, the Scythians and Cimmerians are recorded in Assyrian texts as having conquered Urartu. In the 670s, the Scythians under their king Bartatua raided the territories of the Assyrian Empire. The Assyrian king Esarhaddon managed to make peace with the Scythians by paying a large amount of tribute.[2] Bartatua was succeeded by his son Madius ca. 645 BC, after which they launched a great raid on Palestine and Egypt. Madius subsequently subjugated the Median Empire. During this time, Herodotus notes that the Scythians raided and exacted tribute from "the whole of Asia". In the 620s, Cyaxares, leader of the Medes, treacherously killed a large number of Scythian chieftains at a feast; the Scythians were subsequently driven back to the steppe. In 612 BC, the Medes and Scythians participated in the destruction of the Assyrian Empire with the Battle of Nineveh. During this period of influence in the Middle East, the Scythians became heavily influenced by the local civilizations.[36]

In the 6th century BC, the Greeks had begun establishing settlements along the coasts and rivers of the Pontic steppe, coming in contact with the Scythians. Relations between the Greeks and the Scythians appear to have been peaceful, with the Scythians being substantially influenced by the Greeks, although the city of the Panticapaeum might have been destroyed by the Scythians in the mid century BC. During this time, the Scythian philosopher Anacharsis traveled to Athens, where he made a great impression on the local people with his "barbarian wisdom".[2]

War with Persia

By the late 6th century BC, the Archaemenid king Darius the Great had built Persia into the most powerful empire in the world, stretching from Egypt to India. Planning an invasion of Greece, Darius first sought to secure his northern flank against Scythian inroads. Thus, Darius declared war on the Scythians.[36] At first, Darius sent his Cappadocian satrap Ariamnes with a vast fleet (estimated at 600 ships by Herodotus) into Scythian territory, where several Scythian nobles were captured. He then built a bridge across the Bosporus and easily defeated the Thracians, crossing the Danube into Scythian territory with a large army (700,000 men if one is to believe Herodotus) in 512 BC.[38] At this time Scythians were separated into three major kingdoms, with the leader of the largest tribe, King Idanthyrsus, being the supreme ruler, and his subordinate kings being Scopasis and Taxacis.

Unable to receive support from neighboring nomadic peoples against the Persians, the Scythians evacuated their civilians and livestock to the north and adopted a scorched earth strategy, while simultaneously harassing the extensive Persian supply lines. Suffering heavy losses, the Persians reached as far as the Sea of Azov, until Darius was compelled to enter into negotiations with Idanthyrsus, which however broke down. Darius and his army eventually retreated across the Danube back into Persia, and the Scythians thereafter earned a reputation of invincibility among neighboring peoples.[38][2]

Golden Age

In the aftermath of their defeat of the Persian invasion, Scythian power grew considerably, and they launched campaigns against their Thracian neighbors in the west.[39] In 496 BC, the Scythians launched an great expedition into Thrace, reaching as far as Chersonesos.[2] During this time they negotiated an alliance with the Achaemenid Empire against the Spartan king Cleomenes I. A prominent king of the Scythians in the 5th century was Scyles.[36]

The Scythian offensive against the Thracians was checked by the Odrysian kingdom. The border between the Scythians and the Odrysian kingdom was thereafter set at the Danube, and relations between the two dynasties were good, with dynastic marriages frequently occurring.[2] The Scythians also expanded towards the north-west, where they destroyed numerous fortified settlements and probably subjucated numerous settled populations. A similar fate was suffered by the Greek cities of the northwestern Black Sea coast and parts of the Crimea, over which the Scythians established political control.[2] Greek settlements along the Don River also came under the control of the Scythians.[2]

A division of responsibility developed, with the Scythians holding the political and military power, the urban population carrying out trade, and the local sedentary population carrying out manual labor.[2] Their territories grew grain, and shipped wheat, flocks, and cheese to Greece. The Scythians apparently obtained much of their wealth from their control over the slave trade from the north to Greece through the Greek Black Sea colonial ports of Olbia, Chersonesos, Cimmerian Bosporus, and Gorgippia.

When Herodotus wrote his Histories in the 5th century BC, Greeks distinguished Scythia Minor, in present-day Romania and Bulgaria, from a Greater Scythia that extended eastwards for a 20-day ride from the Danube River, across the steppes of today's East Ukraine to the lower Don basin.

Scythian offensives against the Greek colonies of the northeastern Black Sea coast were largely unsuccessful, as the Greeks united under the leadership of the city of Panticapaeum and put up a vigorous defence. These Greek cities developed into the Bosporan Kingdom. Meanwhile, several Greek colonies formerly under Scythian control began to reassert their independence. It is possible that the Scythians were suffering from internal troubles during this time.[2] By the mid 4th century BC, the Sarmatians, a related Iranian people living to the east of the Scythians, began expanding into Scythian territory.[36]

The 4th century BC was a flowering of Scythian culture. The Scythian king Ateas managed to unite under his power the Scythian tribes living between the Maeotian marshes and the Danube, while simultaneously enroaching upon the Thracians.[39] He conquered territories along the Danube as far the Sava river and established a trade route from the Black Sea to the Adriatic, which enabled a flourishing of trade in the Scythian kingdom. The westward expansion of Ateas brought him into conflict with Philip II of Macedon (reigned 359 to 336 BC), with whom he had previously been allied,[2] who took military action against the Scythians in 339 BC. Ateas died in battle, and his empire disintegrated.[36] Philip's son, Alexander the Great, continued the conflict with the Scythians. In 331 BC, his general Zopyrion invaded Scythian territory with a force of 30,000 men, but was routed and killed by the Scythians near Olbia.[39][2]

Decline

In the aftermath of conflict between Macedon and the Scythians, the Celts seem to have displaced the Scythians from the Balkans; while in south Russia, a kindred tribe, the Sarmatians, gradually overwhelmed them. In 310-309 BC, as noted by Diodorus Siculus, the Scythians, in alliance with the Bosporan Kingdom, defeated the Siraces in a great battle at the river Thatis.[39]

By the early 3rd century BC, the Scythian culture of the Pontic steppe suddenly disappears. The reasons for this are controversial, but the expansion of the Sarmatians certainly played a role. The Scythians in turn shifted their focus towards the Greek cities of the Crimea.[2]

By ca. 200 BC, the Scythians had largely withdrawn into the Crimea. By the time of Strabo's account (the first decades AD), the Crimean Scythians had created a new kingdom extending from the lower Dnieper to the Crimea, centered at Scythian Neapolis near modern Simferopol. They had become more settled and were intermingling with the local populations, in particular the Tauri, and were also subjected to Hellenization. They maintained close relations with the Bosporan Kingdom, with whose dynasty they were linked by marriage. A separate Scythian territory, known as Scythia Minor, existed in modern-day Dobruja, but was of little significance.[2]

In the 2nd century BC, the Scythian kings Skilurus and Palakus sought to extend their control over the Greek cities of north of the Black Sea. The Greek cities of Chersonesus and Olbia in turn requested the aid Mithridates the Great, king of Pontus, whose general Diophantus defeated their armies in battle, took their capital and annexed their territory to the Bosporan Kingdom.[36][39][7] After this time, the Scythians practically disappeared from history.[39] Scythia Minor was also defeated by Mithradates.[2]

In the years after the death of Mithradates, the Scythians had transitioned to a settled way of life and were assimilating into neighboring populations. They made a resurgence in the 1st century AD and laid siege to Chersonesos, who were obliged to seek help from the Roman Empire. The Scythians were in turn defeated by Roman commander Tiberius Plautius Silvanus Aelianus.[2] By the 2nd century AD, archaeological evidence shows that the Scythians had been largely assimilated by the Sarmatians.[2] Their capital city, Scythian Neapolis, was destroyed by the invading Goths in the mid-3rd century AD.

Archaeology

Archaeological remains of the Scythians include kurgan tombs (ranging from simple exemplars to elaborate "Royal kurgans" containing the "Scythian triad" of weapons, horse-harness, and Scythian-style wild-animal art), gold, silk, and animal sacrifices, in places also with suspected human sacrifices.[40] Mummification techniques and permafrost have aided in the relative preservation of some remains. Scythian archaeology also examines the remains of cities and fortifications.[41][42][43]

Scythian archaeology can be divided into three stages:[2]

- Early Scythian – from the mid-8th or the late 7th century BC to about 500 BC

- Classical Scythian or Mid-Scythian – from about 500 BC to about 300 BC

- Late Scythian – from about 200 BC to the mid 3rd century CE, in the Crimea and the Lower Dnieper, by which time the population was settled.

Early Scythian

In the south of Eastern Europe, Early Scythian culture replaced sites of the so-called Novocherkassk type. The date of this transition is disputed among archaeologists. Dates ranging from the mid-8th century to the late 7th century BC have been proposed. A transition in the late 8th century has gained the most scholarly support. The origins of the Early Scythian culture is controversial. Many of its elements are of Central Asian origin, but the culture appears to have reached its ultimate form on the Pontic steppe, partially through the influence of North Caucasian elements and to a smaller extent the influence of Near Eastern elements.[2]

The period in the 8th and 7th centuries BC when the Cimmerians and Scythians raided the Near East are ascribed to the later stages of the Early Scythian culture. Examples of Early Scythian burials in the Near East include those of Norşuntepe and İmirler. Objects of Early Scythian type have been found in Urartian fortresses such as Teishebaini, Bastam, and Ayanis-kale. Near Eastern influences are probably explained through objects made by Near Eastern craftsmen on behalf of Scythian chieftains.[2]

Early Scythian culture is known primarily from its funerary sites, because the Scythians at this time were nomads without permanent settlements. The most important sites are located in the northwestern parts of Scythian territories in the forest steppes of the Dnieper, and the southeastern parts of Scythian territories in the North Caucasus. At this time it was common for the Scythians to be buried in the edges of their territories. Early Scythian sites are characterized by similar artifacts with minor local variations.[2]

Kurgans from the Early Scythian culture have been discovered in the North Caucasus. Some if these are characterized by great wealth, and probably belonged royals of aristocrats. They contain not only the deceased, but also horses and even chariots. The burial rituals carried out in these kurgans correspond closely with those described by Herodotus. The greatest kurgans from the Early Scythian culture in the North Caucasus are found at Kelermesskaya, Novozavedennoe II (Ulsky Kurgans) and Kostromskaya. One kurgan at Ulsky was found measured at 15 meters in height and contained more than 400 horses. Kurgans from the 7th century BC, when the Scythians were raiding the Near East, typically contain objects of Near Eastern origin. Kurgans from the late 7th century however, contain few Middle Eastern objects, but rather objects of Greek origin, pointing to increased contacts between the Scythians and Greek colonists.[2]

Important Early Scythian sites have also been found in the forest steppes of the Dnieper. The most important of these finds is the Melgunov Kurgan. This kurgan contains several objects of Near Eastern origin so similar to those found at the kurgan in Kelermesskaya that they were probably made in the same workshop. Most of Early Scythian sites in this area are situated along the banks of the Dnieper and its tributiaries. The funerary rites of these sites are similar but not identical to those of the kurgans in the North Caucasus.[2]

Important Early Scythian sites have also been discovered in the areas separating the North Caucasus and the forest steppes. These include the Krivorozhskiĭ kurgan on the eastern banks of the Donets, and the Temir-gora kurgan in the Crimea. Both date to the 7th century BC and contain Greek imports. The Krivorozhskiĭ also display Near Eastern influences.[2]

Apart from funerary sites, numerous settlements from the Early Scythian period have been discovered. Most of these settlements are located in the forest steppe zone and are non-fortified. The most important of these sites in the Dnieper area are Trakhtemirovo, Motroninskoe, and Pastyrskoe. East of these, at the banks of the Vorskla River, a tributiary of the Dnieper, lies the Bilsk settlement. Occupying an area of 4,400 hectares with an outer rampart at over 30 km, Bilsk is the largest settlement in the forest steppe zone.[2] It has been tentatively identified by a team of archaeologists led by Boris Shramko as the site of Gelonus, the purported capital of Scythia.

Another important large settlement can be found at Myriv. Dating from the 7th and 6th centuries BC, Myriv contains a significant amount of imported Greek objects, testifying to lively contacts with Borysthenes, the first Greek colony established on the Pontic steppe (ca. 625 BC). Within the ramparts in these settlements there were areas without buildings, which were probably occupied by nomadic Scythians seasonally visiting the sites.[2]

The Early Scythian culture came to an end in the latter part of the 6th century BC.[2]

Classical Scythian

By the end of the 6th century BC, a new period begins in the material culture of the Scythians. Certain scholars consider this a new stage in the Scythian culture, while others consider it an entirely new archaeological culture. It is possible that this new culture arose through the settlement of a new wave of nomads from the east, who intermingled with the local Scythians. The Classical Scythian period saw major changes in Scythian material culture, both with regards to weapons and art style. This was largely through Greek influence. Other elements had probably been brought from the east.[2]

Like in Early Scythian culture, the Classical Scythian culture is primarily represented through funerary sites. The area of distribution of these sites has however changed. Most of them, including the richest, are located on the Pontic steppe, in particular the area around the Dnieper Rapids.[2]

At the end of the 6th century BC, new funerary rites appeared, characterized by more complex kurgans. This new style was rapidly adopted throughout Scythian territory. Like before, elite burials usually contained horses. A buried king was usually accompanied with multiple people from his entourage. Burials containing both males and females are quite common both in elite burials and in the burials of the common people.[2]

The most important Scythian kurgans of the Classical Scythian culture in the 6th and 5th centuries BC are Ostraya Tomakovskaya Mogila, Zavadskaya Mogila 1, Novogrigor’evka 5, Baby and Raskopana Mogila in the Dnieper Rapids, and the Zolotoi and Kulakovskiĭ kurgans in the Crimea.[2]

The greatest, so-called "royal" kurgans of the Classical Scythian culture are dated to the 4th century BC. These include Solokha, Bol’shaya Cymbalka, Chertomlyk, Oguz, Alexandropol, and Kozel. The second greatest, so-called "aristocratic" kurgans, include Berdyanskiĭ, Tolstaya Mogila, Chmyreva Mogila, Five Brothers 8, Melitopolsky, Zheltokamenka, and Krasnokutskiĭ.[2]

Excavation at kurgan Sengileevskoe-2 found gold bowls with coatings indicating a strong opium beverage was used while cannabis was burning nearby. The gold bowls depicted scenes showing clothing and weapons.[44]

By the time of Classical Scythian culture, the North Caucasus appears to no longer be under Scythian control. Rich kurgans in the North Caucasus have been found at the Seven Brothers Hillfort, Elizavetovka, and Ulyap, but although they contain elements of Scythian culture, these probably belonged to an unrelated local population. Rich kurgans of the forest steppe zone from the 5th and 4th centuries BC have been discovered at places such as Ryzhanovka, but these are not as grand as the kurgans of the steppe further south.[2]

Funerary sites with Scythian characteristics have also been discovered in several Greek cities. These include several unusually rich burials such as Kul-Oba (near Panticapaeum in the Crimea) and the necropolis of Nymphaion. The sites probably represent Scythian aristocrats who had close ties, if not family ties, with the elite of Nymphaion and aristocrats, perhaps even royals, of the Bosporan Kingdom.[2]

In total, more than 3,000 Scythian funerary sites from the 4th century BC have been discovered on the Pontic steppe. This number far exceeds the number of all funerary sites from previous centuries.[2]

Apart from funerary sites, remains of Scythian cities from this period have been discovered. These include both continuations from the Early Scythian period and newly founded settlements. The most important of these is the settlement of Kamenskoe on the Dniepr, which existed from the 5th century to the beginning of the 3rd century BC. It was a fortified settlement occupying an area of 12 square km. The chief occupation of its inhabitants appears to have been metalworking, and the city was probably an important supplier of metalwork for the nomadic Scythians. Part of the population was probably composed of agriculturalists. It is likely that Kamenskoe also served as a political center in Scythia. A significant part of Kamenskoe was not built up, perhaps to set it aside for the Scythian king and his entourage during their seasonal visits to the city.[2] János Harmatta suggests that Kamenskoe served as a residence for the Scythian king Ateas.[7]

By the 4th century it appears that some of the Scythians were adopting an agricultural way of life similar to the peoples of the forest steppes. As result, a number of fortified and non-fortified settlements spring up in the areas of the lower Dnieper. Part of the settled inhabitants of Olbia were also of Scythian origin.[2]

Classical Scythian culture lasts until the late 4th century or early 3rd century BC.[2]

Late Scythian

The last period in the Scythian archaeological culture is the Late Scythian culture, which existed in the Crimea and the Lower Dnieper from the 3rd century BC. This area was at the time mostly settled by Scythians.[2]

Archaeologically the Late Scythian culture has little in common with its predecessors. It represents a fusion of Scythian traditions with those of the Greek colonists and the Tauri, who inhabited the mountains of the Crimea. The population of the Late Scythian culture was mainly settled, and were engaged in stockbreeding and agriculture. They were also important traders, serving as intermediaries between the classical world and the barbarian world.[2]

Recent excavations at Ak-Kaya/Vishennoe implies that this site was the political center of the Scythians in the 3rd century BC and the early part of the 2nd century BC. It was a well protected fortress constructed in accordance with Greek principles.[2]

The most important site of the Late Crimean culture is Scythian Neaoplis, which was located in Crimea and served as the capital of the Late Scythian kingdom from the early 2nd century BC to the beginning of the 3rd century AD. Scythian Neapolis was largely constructed in accordance with Greek principles. Its royal palace was destroyed by Diophantus, a general of the Pontic king Mithridates VI, at the end of the 2nd century BC, and was not rebuilt. The city nevertheless continued to exist as a major urban center. It underwent significant change from the 1st century to the 2nd century AD, eventually being left with virtually no buildings except from its fortifications. New funerary rites and material features also appear. It is probable that these changes represent the assimilation of the Scythians by the Sarmatians. A certain continuity is however observable. From the end of the 2nd century to the middle of the 3rd century AD, Scythian Neapolis transforms into a non-fortified settlement containing only a few buildings.[2]

Apart from Scythian Neapolis and Ak-Kaya/Vishennoe, more than 100 fortified and non-fortified settlements from the Late Scythian culture have been discovered. They are often accompanied by a necropolis. Late Scythian sites are mostly found in areas around the foothills of the Crimean mountains and along the western coast of the Crimea. Some of these settlements had earlier been Greek settlements, such as Kalos Limen and Kerkinitis. Many of these coastal settlements served as trading ports.[2]

The largest Scythian settlements after Neapolis and Ak-Kaya-Vishennoe were Bulganak, Ust-Alma, and Kermen-Kyr. Like Neapolis and Ak-Kaya, these are characterized by a combination of Greek architectural principles and local ones.[2]

A unique group of Late Scythian settlements were city-states located on the banks of the Lower Dnieper. The material culture of these settlements was even more Hellenized than those on the Crimea, and they were probably closely connected to Olbia, if not dependent it.[2]

Burials of the Late Scythian culture can be divided into two kurgans and necropolises, with necropolises becoming more and more common as time progresses. The largest such necropolis has been found at Ust-Alma.[2]

Because of close similarities between the material culture of the Late Scythians and that of neighboring Greek cities, many scholars have suggested that Late Scythian cites, particularly those of the Lower Dnieper, were populated at last partly by Greeks. Influences of Sarmatian elements and the La Tène culture have been pointed out.[2]

The Late Scythian culture ends in the 3rd century AD.[2]

Culture and society

Since the Scythians did not have a written language, their non-material culture can only be pieced together through writings by non-Scythian authors, parallels found among other Iranian peoples, and archaeological evidence.[2]

Tribal divisions

Scythians lived in confederated tribes, a political form of voluntary association which regulated pastures and organised a common defence against encroaching neighbours for the pastoral tribes of mostly equestrian herdsmen. While the productivity of domesticated animal-breeding greatly exceeded that of the settled agricultural societies, the pastoral economy also needed supplemental agricultural produce, and stable nomadic confederations developed either symbiotic or forced alliances with sedentary peoples – in exchange for animal produce and military protection.

Herodotus relates that three main tribes of the Scythians descended from three sons of Targitaus: Lipoxais, Arpoxais, and Colaxais. They called themselves Scoloti, after one of their kings.[45] Herodotus writes that the Auchatae tribe descended from Lipoxais, the Catiari and Traspians from Arpoxais, and the Paralatae (Royal Scythians) from Colaxais, who was the youngest brother.[46] According to Herodotus the Royal Scythians were the largest and most powerful Scythian tribe, and looked "upon all the other tribes in the light of slaves."[47]

Although scholars have traditionally treated the three tribes as geographically distinct, Georges Dumézil interpreted the divine gifts as the symbols of social occupations, illustrating his trifunctional vision of early Indo-European societies: the plough and yoke symbolised the farmers, the axe – the warriors, the bowl – the priests. The first scholar to compare the three strata of Scythian society to the Indian castes was Arthur Christensen. According to Dumézil, "the fruitless attempts of Arpoxais and Lipoxais, in contrast to the success of Colaxais, may explain why the highest strata was not that of farmers or magicians, but rather that of warriors."[48]

Warfare

The Scythians were a warlike people. When engaged at war, almost the entire adult population, including a large number of women, would participate in battle.[50] The Athenian historian Thucydides noted that no people in either Europe or Asia could resist the Scythians without outside aid.[50]

Scythians were particularly known for their equestrian skills, and their early use of composite bows shot from horseback. With great mobility, the Scythians could absorb the attacks of more cumbersome footsoldiers and cavalry, just retreating into the steppes. Such tactics wore down their enemies, making them easier to defeat. The Scythians were notoriously aggressive warriors. Ruled by small numbers of closely allied elites, Scythians had a reputation for their archers, and many gained employment as mercenaries. Scythian elites had kurgan tombs: high barrows heaped over chamber-tombs of larch wood, a deciduous conifer that may have had special significance as a tree of life-renewal, for it stands bare in winter.

The Ziwiye hoard, a treasure of gold and silver metalwork and ivory found near the town of Saqqez south of Lake Urmia and dated to between 680 and 625 BC, includes objects with Scythian "animal style" features. One silver dish from this find bears some inscriptions, as yet undeciphered and so possibly representing a form of Scythian writing.

Scythians also had a reputation for the use of barbed and poisoned arrows of several types, for a nomadic life centred on horses – "fed from horse-blood" according to Herodotus – and for skill in guerrilla warfare.

Some Scythian-Sarmatian cultures may have given rise to Greek stories of Amazons. Graves of armed females have been found in southern Ukraine and Russia. David Anthony notes, "About 20% of Scythian-Sarmatian 'warrior graves' on the lower Don and lower Volga contained females dressed for battle as if they were men, a style that may have inspired the Greek tales about the Amazons."[51]

Clothing

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2015) |

According to Herodotus, Scythian costume consisted of padded and quilted leather trousers tucked into boots, and open tunics. They rode without stirrups or saddles, using only saddle-cloths. Herodotus reports that Scythians used cannabis, both to weave their clothing and to cleanse themselves in its smoke (Hist. 4.73–75); archaeology has confirmed the use of cannabis in funerary rituals. Men seemed to have worn a variety of soft headgear – either conical like the one described by Herodotus, or rounder, more like a Phrygian cap.

Women wore a variety of different headdresses, some conical in shape others more like flattened cylinders, also adorned with metal (golden) plaques.

Scythian women wore long, loose robes, ornamented with metal plaques (gold). Women wore shawls, often richly decorated with metal (golden) plaques.

Based on numerous archeological findings in Ukraine, southern Russia, and Kazakhstan, men and warrior women wore long sleeve tunics that were always belted, often with richly ornamented belts.

Men and women wore long trousers, often adorned with metal plaques and often embroidered or adorned with felt appliqués; trousers could have been wider or tight fitting depending on the area. Materials used depended on the wealth, climate, and necessity.

Men and women warriors wore variations of long and shorter boots, wool-leather-felt gaiter-boots, and moccasin-like shoes. They were either of a laced or simple slip on type. Women wore also soft shoes with metal (gold) plaques.

Men and women wore belts. Warrior belts were made of leather, often with gold or other metal adornments and had many attached leather thongs for fastening of the owner's gorytos, sword, whet stone, whip etc. Belts were fastened with metal or horn belt-hooks, leather thongs, and metal (often golden) or horn belt-plates.

Religion

Scythian religion was a type of Pre-Zoroastrian Iranian religion and differed from the post-Zoroastrian Iranian thoughts.[7] The Scythian belief was a more archaic stage than the Zoroastrian and Hindu systems. The use of cannabis to induce trance and divination by soothsayers was a characteristic of the Scythian belief system.[7]

Our most important literary source on Scythian religion is Herodotus. According to him the leading deity in the Scythian pantheon was Tabiti, whom he compared to the Greek goddess Hestia.[2] Tabiti was eventually replaced by Atar, the fire-pantheon of Iranian tribes, and Agni, the fire deity of Indo-Aryans.[7] Other deities mentioned by Herodotus include Papaios, Api, Goitosyros/Oitosyros, Argimpasa, and Thagimasadas, whom he identified with Zeus, Gaia, Apollo, Aphrodite, and Poseidon respectively. The Scythians are also said by Herodotus to have worshipped equivalents of Heracles and Ares, but he does not mention their Scythian names.[2] An additional Scythian deity, the goddess Dithagoia, is mentioned in the a dedication by Senamotis, daughter of King Skiluros, at Panticapaeum. Most of the names of Scythian deities can be traced back to Iranian roots.[2]

Herodotus states that Thagimasadas was worshipped by the Royal Scythians only, while the remaining deities were worshipped by all. He also states that "Ares", the god of war, was the only god to whom the Scythians dedicated statues, altars or temples. Tumuli were erected to him in every Scythian district, and both animal sacrifices and human sacrifices were performed in honor of him. At least one shrine to "Ares" has been discovered by archaeologists.[2]

The Scythians had professional priests, but it is not known whether they constituted a hereditary class. Among the priests there was a separate group, the Enarei, who worshipped the goddess Argimpasa and assumed feminine identities.[2]

Scythian mythology gave much importance to myth of the "First Man", who was considered the ancestor of them and their kings. Similar myths are common among other Iranian peoples. Considerable importance was given to the division of Scythian society into three hereditary classes, which consisted of warriors, priests, and producers. Kings were considered part of the warrior class. Royal power was considered holy and of solar and heavenly origin.[7] The Iranian principle of royal charisma, known as khvarenah in the Avesta, played a prominent role in Scythian society. It is probable that the Scythians had a number of epic legends, which were possibly the source for Herodotus writings on them.[2] Traces of these epics can be found in the epics of the Ossetians of the present day.[7]

In Scythian cosmology the world was divided into three parts, with the warriors, considered part of the upper world, the priests of the middle level, and the producers of the lower one.[2]

Art

The art of the Scythians and related peoples of the Scythian cultures is known as Scythian art. It is particularly characterized by its use of the animal style.[2]

Scythian animal style appears in an already established form Eastern Europe in the 8th century BC along with the Early Scythian archaeological culture itself. It bears little resemblance to the art of pre-Scythian cultures of the area. Some scholars suggest the art style developed under Near Eastern influence during the military campaigns of the 7th century BC, but the more common theory is that it developed on the eastern part of the Eurasian Steppe under Chinese influence. Others have sought to reconcile the two theories, suggesting that the animal style of the west and eastern parts of the steppe developed independently of each other, under Near Eastern and Chinese influences respectively. Regardless, the animal style art of the Scythians differs considerable from that of peoples living further east.[2]

Scythian animal style works are typically divided into birds, ungulates, and beasts of prey. This probably reflects the tripatriate division of the Scythian cosmos, with birds belonging to the upper level, ungulates to the middle level, and beasts of prey in the lower level.[2]

Images of mythological creatures such a griffins are not uncommon in Scythian animal style, but these are probably the result of Near Eastern influences. By the late 6th century, as Scythian activity in the Near East was reduced, depictions of mythological creatures largely disappears from Scythian art. It however reappears again in the 4th century BC as a result of Greek influence.[2]

Anthropomorphic depictions in Early Scythian art is known only from kurgan stelae. These depict warriors with almond-shaped eyes and mustaches, often including weapons and other military equipment.[2]

Since the 5th century BC, Scythian art changed considerably. This was probably a result of Greek and Persian influence, and possibly also internal developments caused by an arrival of a new nomadic people from the east. The changes are notable in the more realistic depictions of animals, who are now often depicted fighting each other rather than being depicted individually. Kurgan stelae of the time also display traces of Greek influences, with warriors being depicted with rounder eyes and full beards.[2]

The 4th century BC show additional Greek influence. While animal style was still in use, it appears that much Scythian art by this point was being made by Greek craftsmen on behalf of Scythians. Such objects are frequently found in royal Scythian burials of the period. Depictions of human beings become more prevalent. Many objects of Scythian art made by Greeks are probably illustrations of Scythian legends. Several objects are believed to have been of religious significance.[2]

By the late 3rd century BC, original Scythian art disappears through ongoing Hellenization. The creation of anthropomorphic gravestones continued however.[2]

Works of Scythian art are held at many museums and has been featured at many exhibitions. The largest collections of Scythian art are found at the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg and the Museum of Historical Treasures of the Ukraine in Kiev, while smaller collections are found at the Staatliche Antikensammlungen in Berlin, the Ashmolean Museum of Oxford, and the Louvre of Paris.[2]

Gender

The idea of gender was fluid in the Scythian culture.[additional citation(s) needed] Barry Cunliffe says, "[the idea] that gender boundaries were fluid among the Scythians is explicitly stated by various classical observers, most notably Herodotus and Pseudo-Hippocrates."[52]

Women

Pseudo-Hippocrates says that Sarmatian (a people considered part of Scythian culture) women would ride on horseback; and they use a bow and throw javelins from their horses. He continues by saying that the women would remain virgins until they could kill three of their enemies. Pseudo-Hippocrates also says that young girls would have their right breast cauterized to stop it from developing; this would help give the young warrior enhanced strength as an archer. Herodotus called these women Amazons (meaning "without a breast," in Greek). Women had a prominent role in hunting and in battle, according to Herodotus. He also says that women would sometimes dress like men. According to Barry Cunliffe, these accounts confirm each other and they are partially supported by archaeological evidence. In the old Sarmatian territory, one fifth of the warrior burials, dating to the fifth and fourth centuries BCE, are female; and a fifth of female graves contain weapons.[53]

Men

Pseudo-Hippocrates says that some Scythian men were eunuchs, spoke like women, performed female work, and wore female attire. The Scythian men, according to Pseudo-Hippocrates, accepted their condition as the will of the gods — however, Pseudo-Hippocrates rejects this explanation. He said that gender transfer was more common among the rich and elite. Herodotus also noted the effeminacy of some Scythian men. Herodotus says that the gods inflicted this "female sickness" upon them because they destroyed the temple of Venus in Ascalon.[54]

Male Scythian burials in Siberia, dating back to the second and third centuries BCE, containing female decorations and utensils have been discovered. Some have interpreted these findings as suggesting ancient roots to the phenomenon.[55]

The grave of a Scythian priestess near the Bug River contains items that attract speculation that it could be an Enaree. The skeleton has been described as a 40-45-year-old woman. The grave includes female cosmetic items, such as a bronze mirror, and it contains a cowrie shell, which is often seen as a traditional vagina symbol. However, recent interpretations of the burial have suggested that "the face is definitely masculine" and that it is an Enaree.[56]

Charles Chiasson has pointed out that Pseudo-Hippocrates tries to display the cross dressers as the ruling class (Anarieis), who are "aristocratic poster-boys for the effeminacy that he posits as a characteristic national trait"; and Herodotus tries to represent the cross dressers (the Enaree, as they are called by Herodotus) as a marginalized group in a masculine warrior society — he describes the cross dressing as a sickness inflicted on them by a foreign deity, thereby making their belief in androgyny foreign. According to Chiasson, Herodotus' portrayal of the Enaree is much more accurate than Pseudo-Hippocrates' portrayal of them as aristocrats. Chiasson suggests that the reason for Pseudo-Hippocrates' view of the Scythians is because of his theory of climatic determinism, where the climate affects both the physical and psychological characteristics of people. For example, he claims that the variation of Europe's climate made Europeans more courageous, fiercer, and more warlike than Asians. Pseudo-Hippocrates says that the cold and moist climate that the Scythians lived in robbed them of their desire for sex and that their nomadic lifestyle robbed them of the strength for sex — the nomadic lifestyle entails excessive horse riding and too much trouser wearing, which, according to Pseudo-Hippocrates, robs men of the strength to have sex.[57] The scholar and archaeologist Ellis Minns said that Pseudo-Hippocrates may have been correct in asserting that constant horse riding caused the phenomenon. Minns says that his friend Dr. L. Bousfield "suggests that it was very bad orchitis."[58] Minns' and Pseudo-Hippocrates' theories have gained support by some more recent scholars. Timothy Taylor claims that it is plausible, in terms of modern medical knowledge, that both Minns and Pseudo-Hippocrates are correct. Taylor says that jolting can cause severe, irreversible damage to the testicles and that trousers raise the temperature of the testicles, which can cause infertility.[59] However, Yulia Ustinova has contradicted these claims; she says, "these rational explanations over-simplify the significance of the phenomenon that is ostensibly associated with the ritual sphere. Both appearance and behavior of the Enareis [Enaree] are manifestly transvestite."[55]

Ustinova goes on to offer a different account of the Enaree. She says that it is one of the elements of the shamanic complex. In the shamanic cultures of Northern Eurasia and Central Asia, the shamans who changed their sex were very powerful and scared laymen. Ustinova suggests that the sex transformation must have began late in their lives. She also says that the roots of the phenomenon must be ancient.[55]

Rachel Hart has concluded that both Pseudo-Hippocrates and Herodotus are describing the same tradition that is similar to the cross-cultural tradition of cross-dressing shamans.[60]

Language

The Scythians spoke a language belonging to the Scythian languages, most probably[61] a branch of the Eastern Iranian languages.[6] Whether all the peoples included in the "Scytho-Siberian" archaeological culture spoke languages from this family is uncertain.

The Scythian languages may have formed a dialect continuum: "Scytho-Sarmatian" in the west and "Scytho-Khotanese" or Saka in the east.[62] The Scythian languages were mostly marginalised and assimilated as a consequence of the late antiquity and early Middle Ages Slavic and Turkic expansion. The western (Sarmatian) group of ancient Scythian survived as the medieval language of the Alans and eventually gave rise to the modern Ossetian language.[63]

Physical appearance

In artworks, the Scythians are portrayed exhibiting Europoid traits.[64] These portrayals have since been confirmed by physical anthropologists.[65]

Complexion

In Histories, the 5th-century BC Greek historian Herodotus describes the Budini of Scythia as red-haired and grey-eyed.[64] In the 5th century BC, Greek physician Hippocrates argued that the Scythians were light skinned.[64][69] In the 3rd century BC, the Greek poet Callimachus described the Arismapes (Arimaspi) of Scythia as fair-haired.[64][70]

The 2nd century BC Han Chinese envoy Zhang Qian described the Sai (Saka), an eastern people closely related to the Scythians, as having yellow (probably meaning hazel or green), and blue eyes.[64]

In Natural History, the 1st century AD Roman author Pliny the Elder characterises the Seres, sometimes identified as Saka or Tocharians, as red-haired, blue-eyed, and unusually tall.[64][71] In the late 2nd century AD, the Christian theologian Clement of Alexandria says that the Scythians and the Celts had long auburn hair.[64][72] The 2nd century Greek philosopher Polemon includes the Scythians among the northern peoples characterised by red hair and blue-grey eyes.[64]

In the late 2nd or early 3rd century AD, the Greek physician Galen writes that Scythians, Sarmatians, Illyrians, Germanic peoples, and other northern peoples have reddish hair.[64][73] The fourth-century Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus wrote that the Alans, a people closely related to the Scythians, were tall, blond, and light-eyed.[74]

The 4th century bishop Gregory of Nyssa wrote that the Scythians were fair-skinned and blond-haired.[75] The 5th-century physician Adamantius, who often follow Polemon, describes the Scythians are fair-haired.[64][76] It is possible that the later physical descriptions by Adamantius and Gregory of Scythians refer to East Germanic tribes, as the latter were frequently referred to as "Scythians" in Roman sources at that time.

Stature

Anthropological data shows that the Scythians were tall and powerfully built, even by modern standards. This was particularly the case for warriors and noblemen, who were often more than 6 ft (1.83 m) tall. Sometimes they exceeded 6 ft 3 in (1.90 m) in height, and males even exceeding 6 ft 6 in (2 m) have been uncovered. The ordinary people whom they dominated were of much smaller stature, averaging 4–6 in. (10–15 cm) below them in height. Skeletons of Scythian nobles differ from those of today by their longer arm and leg bones, and stronger bone formation. These physical characteristics affirm an Iranian origin.[65]

Genetics

In 2017, a genetic study of various Scythian cultures, including the Scythians, was published in Nature Communications.[3] The study suggested that the Scythians arose independently of culturally similar groups further east. Though all groups studies shared a common origin in the Yamnaya culture, the presence of east Eurasian mitochondrial lineages was largely absent among Scythians, but present among other groups further east. Modern populations most closely related to the Scythians were found to be populations living in proximity to the sites studied, suggesting genetic continuity.

Another 2017 genetic study, published in Scientific Reports, found that the Scythians shared common mitocondrial lineages with the earlier Srubnaya culture. It also noted that the Scythians differed from materially similar groups further east by the absence of east Eurasian mitochondrial lineages. The authors of the study suggested that the Srubnaya culture was the source of the Scythian cultures of at least the Pontic steppe.[33]

A genetic study published in Nature in May 2018 examined the remains of five Scythian individuals buried in Hungary between 400 BC and 300 BC. The sample of Y-DNA extracted belonged to haplogroup R1. The samples of mtDNA extracted belonged to haplogroups H2a2, I2a, H, H2a2a1 and H7a1. Significant genetic differences between the Scythians of Hungary and peoples of Scythian cultures further east were detected, with the Scythians of Hungary displaying higher levels of descent Early European Farmers (EEFs) and no East Asian ancestry. All Scythian groups shared a common descent from Western Steppe Herders (WSHs) of the Late Bronze Age. No significant gene flow between the Scythians of Hungary and peoples of Scythian cultures further east was detected.[77]

In 2018, a genetic study of the earlier Srubnaya culture, and later peoples of the Scythian cultures, including the Scythians, was published in Science Advances. Members of the Srubnaya culture were found to be exclusively carriers of haplogroup R1a1a1, which showed a major expansion during the Bronze Age. Six male Scythian samples from kurgans at Starosillya and Glinoe were successfully analyzed. These were found to be carriers of haplogroup R1b1a1a2. The Scythians were found to be closely related to the Afanasievo culture and the Andronovo culture. The authors of the study suggested that the Scythians were not directly descended from the Srubnaya culture, but that the Scythians and the Srubnaya shared a common origin through the earlier Yamnaya culture. Significant genetic differences were found between the Scythians and materially similar groups further east, which underpinned the notion that although materially similar, the Scythians and groups further east should be seen as separate peoples belonging to a common cultural horizon, which perhaps had its source on the eastern Pontic-Caspian steppe and the southern Urals.[34]

In 2019, a genetic study of remains from the Aldy-Bel culture of southern Siberia, which is materially similar to that of the Scythians, was published in Human Genetics. The majority of Aldy-Bel samples were found to be carriers of haplogroup R1a, including two carriers of haplogroup R1a1a1b2. East Asian admixture was also detected. The results indicated that the Scythians and the Aldy-Bel people were of completely different paternal origins, with almost no paternal gene flowe between them.[78]

In 2019, a genetic study of various peoples belonging to the Scythian cultures, including the Scythians, was published in Current Biology. The Scythians remains were mostly found to be carriers of haplogroup R1a and various subclades of it. The authors of the study suggested that migrations must have played a role in the emergence of the Scythians as the dominant power on the Pontic steppe.[35]

Legacy

Late Antiquity

In Late Antiquity, the notion of a Scythian ethnicity grew more vague and outsiders might dub any people inhabiting the Pontic-Caspian steppe as "Scythians", regardless of their language. Thus, Priscus, a Byzantine emissary to Attila, repeatedly referred to the latter's followers as "Scythians". But Eunapius, Zosimus, Claudius Cladianus, and Olympiodorus usually mean Goths when they write "Scythians".[citation needed]

The Goths had displaced the Sarmatians in the 2nd century from most areas near the Roman frontier, and by early medieval times, early Slavs had largely marginalized the Eastern Iranian dialects in Eastern Europe as they assimilated and absorbed the Iranian ethnic groups in the region.[16][17]

The Scythians played an instrumental role in the ethnogenesis of the Ossetians, who are considered direct descendants of the Alans.[18]

Although the classical Scythians may have largely disappeared by the 1st century BC, Eastern Romans continued to speak conventionally of "Scythians" to designate Germanic tribes and confederations or mounted Eurasian nomadic barbarians in general.[21] In AD 448 two mounted "Scythians" led the emissary Priscus to Attila's encampment in Pannonia. The Byzantines in this case carefully distinguished the Scythians from the Goths and Huns who also followed Attila.

Byzantine sources also refer to the Rus raiders who attacked Constantinople circa 860 in contemporary accounts as "Tauroscythians", because of their geographical origin, and despite their lack of any ethnic relation to Scythians. Patriarch Photius may have first applied the term to them during the Siege of Constantinople (860).

Early Modern usage

Owing to their reputation as established by Greek historians, the Scythians long served as the epitome of savagery and barbarism.

The New Testament includes a single reference to Scythians in Colossians 3:11.[79] In the New Testament, in a letter ascribed to Paul "Scythian" is used as an example of people whom some label pejoratively, but who are, in Christ, acceptable to God:

Here there is no Greek or Jew. There is no difference between those who are circumcised and those who are not. There is no rude outsider, or even a Scythian. There is no slave or free person. But Christ is everything. And he is in everything.[79]

Shakespeare, for instance, alluded to the legend that Scythians ate their children in his play King Lear:

The barbarous Scythian

Or he that makes his generation messes

To gorge his appetite, shall to my bosom

¨ Be as well neighbour'd, pitied, and relieved,

As thou my sometime daughter.[80]

Characteristically, early modern English discourse on Ireland, such as that of William Camden and Edmund Spenser, frequently resorted to comparisons with Scythians in order to confirm that the indigenous population of Ireland descended from these ancient "bogeymen", and showed themselves as barbaric as their alleged ancestors.[81][82]

Descent claims

A number of groups have claimed possible descent from the Scythians, including the Ossetians.[18] Some legends of the Poles,[84] the Picts, the Gaels, the Hungarians (in particular, the Jassics), among others, also include mention of Scythian origins. Some writers claim that Scythians figured in the formation of the empire of the Medes and likewise of Caucasian Albania.

The Scythians also feature in some national origin-legends of the Celts. In the second paragraph of the 1320 Declaration of Arbroath, the élite of Scotland claim Scythia as a former homeland of the Scots. According to the 11th-century Lebor Gabála Érenn (The Book of the Taking of Ireland), the 14th-century Auraicept na n-Éces and other Irish folklore, the Irish originated in Scythia and were descendants of Fénius Farsaid, a Scythian prince who created the Ogham alphabet.

The Carolingian kings of the Franks traced Merovingian ancestry to the Germanic tribe of the Sicambri. Gregory of Tours documents in his History of the Franks that when Clovis was baptised, he was referred to as a Sicamber with the words "Mitis depone colla, Sicamber, adora quod incendisti, incendi quod adorasti." The Chronicle of Fredegar in turn reveals that the Franks believed the Sicambri to be a tribe of Scythian or Cimmerian descent, who had changed their name to Franks in honour of their chieftain Franco in 11 BC.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, foreigners regarded the Russians as descendants of Scythians. It became conventional to refer to Russians as Scythians in 18th-century poetry, and Alexander Blok drew on this tradition sarcastically in his last major poem, The Scythians (1920). In the 19th century, romantic revisionists in the West transformed the "barbarian" Scyths of literature into the wild and free, hardy and democratic ancestors of all blond Indo-Europeans.

Based on such accounts of Scythian founders of certain Germanic as well as Celtic tribes, British historiography in the British Empire period such as Sharon Turner in his History of the Anglo-Saxons, made them the ancestors of the Anglo-Saxons.

Related ancient peoples

Herodotus and other classical historians listed quite a number of tribes who lived near the Scythians, and presumably shared the same general milieu and nomadic steppe culture, often called "Scythian culture", even though scholars may have difficulties in determining their exact relationship to the "linguistic Scythians". A partial list of these tribes includes the Agathyrsi, Geloni, Budini, and Neuri.

See also

- Scythia

- Scythian art

- Scythian languages

- Eurasian nomads

- Nomadic empire

- Pre-Achaemenid Scythian kings of Iran

References

- ^ a b

- Dandamayev 1994, p. 37 "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Central Asia and Eastern Turkestan to distinguish them from the related Massagetae of the Aral region and the Scythians of the Pontic steppes. These tribes spoke Iranian languages, and their chief occupation was nomadic pastoralism."

- Cernenko 2012, p. 3 "The Scythians lived in the Early Iron Age, and inhabited the northern areas of the Black Sea (Pontic) steppes. Though the 'Scythian period' in the history of Eastern Europe lasted little more than 400 years, from the 7th to the 3rd centuries BC, the impression these horsemen made upon the history of their times was such that a thousand years after they had ceased to exist as a sovereign people, their heartland and the territories which they dominated far beyond it continued to be known as 'greater Scythia'."

- Melyukova 1990, pp. 97–98 "From the end of the 7th century B.C. to the 4th century B.C. the Central- Eurasian steppes were inhabited by two large groups of kin Iranian-speaking tribes - the Scythians and Sarmatians... "[I]t may be confidently stated that from the end of the 7th century to the 3rd century B.C. the Scythians occupied the steppe expanses of the north Black Sea area, from the Don in the east to the Danube in the West."

- Ivantchik 2018 "Scythians, a nomadic people of Iranian origin who flourished in the steppe lands north of the Black Sea during the 7th-4th centuries BCE (Figure 1). For related groups in Central Asia and India, see..."

- Sulimirski 1985, pp. 149–153 "During the first half of the first millennium B.C., c. 3,000 to 2,500 years ago, the southern part of Eastern Europe was occupied mainly by peoples of Iranian stock... The main Iranian-speaking peoples of the region at that period were the Scyths and the Sarmatians... [T]he population of ancient Scythia was far from being homogeneous, nor were the Scyths themselves a homogeneous people. The country called after them was ruled by their principal tribe, the "Royal Scyths" (Her. iv. 20), who were of Iranian stock and called themselves "Skolotoi" (iv. 6); they were nomads who lived in the steppe east of the Dnieper up to the Don, and in the Crimean steppe... The eastern neighbours of the "Royal Scyths", the Sauromatians, were also Iranian ; their country extended over the steppe east of the Don and the Volga."

- Sulimirski & Taylor 1991, p. 547 "The name 'Scythian' is met in the classical authors and has been taken to refer to an ethnic group or people, also mentioned in Near Eastern texts, who inhabited the northern Black Sea region."

- West 2002, pp. 437–440 "Ordinary Greek (and later Latin) usage could designate as Scythian any northern barbarian from the general area of the Eurasian steppe, the virtually treeless corridor of drought-resistant perennial grassland extending from the Danube to Manchuria. Herodotus seeks greater precision, and this essay is focussed on his Scythians, who belong to the North Pontic steppe... These true Scyths seems to be those whom he calls Royal Scyths, that is, the group who claimed hegemony... apparently warrior-pastoralists. It is generally agreed, from what we know of their names, that these were people of Iranian stock..."

- Jacobson 1995, pp. 36–37 "When we speak of Scythians, we refer to those Scytho-Siberians who inhabited the Kuban Valley, the Taman and Kerch peninsulas, Crimea, the northern and northeastern littoral of the Black Sea, and the steppe and lower forest-steppe regions now shared between Ukraine and Russia, from the seventh century down to the first century B.C... They almost certainly spoke an Iranian language..."

- Di Cosmo 1999, p. 924 "The first historical steppe nomads, the Scythians, inhabited the steppe north of the Black Sea from about the eight century B.C."

- Rice, Tamara Talbot. "Central Asian arts: Nomadic cultures". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

[Saka] gold belt buckles, jewelry, and harness decorations display sheep, griffins, and other animal designs that are similar in style to those used by the Scythians, a nomadic people living in the Kuban basin of the Caucasus region and the western section of the Eurasian plain during the greater part of the 1st millennium bc.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br Ivantchik 2018

- ^ a b c d e f Unterländer, Martina (March 3, 2017). "Ancestry and demography and descendants of Iron Age nomads of the Eurasian Steppe". Nature Communications. 8: 14615. doi:10.1038/ncomms14615. PMC 5337992. PMID 28256537.

Greek and Persian historians of the 1st millennium BCE chronicle the existence of the Massagetae and Sauromatians, and later, the Sarmatians and Sacae: cultures possessing artefacts similar to those found in classical Scythian monuments, such as weapons, horse harnesses and a distinctive 'Animal Style' artistic tradition. Accordingly, these groups are often assigned to the Scythian culture and referred to as 'Scythians'. For simplification we will use 'Scythian' in the following text for all groups of Iron Age steppe nomads commonly associated with the Scythian culture.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ a b c Di Cosmo 1999, p. 891 "Even though there were fundamental ways in which nomadic groups over such a vast territory differed, the terms "Scythian" and "Scythic" have been widely adopted to describe a special phase that followed the widespread diffusion of mounted nomadism, characterized by the presence of special weapons, horse gear, and animal art in the form of metal plaques. Archaeologists have used the term "Scythic continuum" in a broad cultural sense to indicate the early nomadic cultures of the Eurasian steppe. The term "Scythic" draws attention to the fact that there are elements - shapes of weapons, vessels, and ornaments, as well as lifestyle - common to both the eastern and western ends of the Eurasian steppe region. However, the extension and variety of sites across Asia makes Scythian and Scythic terms too broad to be viable, and the more neutral "early nomadic" is preferable, since the cultures of the Northern Zone cannot be directly associated with either the historical Scythians or any specific archaeological culture defined as Saka or Scytho-Siberian."

- ^

- Ivantchik 2018 "Scythians, a nomadic people of Iranian origin..."

- Harmatta 1996, p. 181 "[B]oth Cimmerians and Scythians were Iranian peoples."

- Sulimirski 1985, pp. 149–153 "During the first half of the first millennium B.C., c. 3,000 to 2,500 years ago, the southern part of Eastern Europe was occupied mainly by peoples of Iranian stock... [T]he population of ancient Scythia was far from being homogeneous, nor were the Scyths themselves a homogeneous people. The country called after them was ruled by their principal tribe, the "Royal Scyths" (Her. iv. 20), who were of Iranian stock and called themselves "Skolotoi"..."

- West 2002, pp. 437–440 "[T]rue Scyths seems to be those whom [Herodotus] calls Royal Scyths, that is, the group who claimed hegemony... apparently warrior-pastoralists. It is generally agreed, from what we know of their names, that these were people of Iranian stock..."

- Rolle 1989, p. 56 "The physical characteristics of the Scythians correspond to their cultural affiliation: their origins place them within the group of Iranian peoples."

- Rostovtzeff 1922, p. 13 "The Scythian kingdom... was succeeded in the Russian steppes by an ascendancy of various Sarmatian tribes—Iranians, like the Scythians themselves."

- Minns 2011, p. 36 "The general view is that both agricultural and nomad Scythians were Iranian."

- ^ a b

- Dandamayev 1994, p. 37 "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Central Asia and Eastern Turkestan to distinguish them from the related Massagetae of the Aral region and the Scythians of the Pontic steppes. These tribes spoke Iranian languages, and their chief occupation was nomadic pastoralism."

- Davis-Kimball, Bashilov & Yablonsky 1995, p. 91 "Near the end of the 19th century V.F. Miller (1886, 1887) theorized that the Scythians and their kindred, the Sauromatians, were Iranian-speaking peoples. This has been a popular point of view and continues to be accepted in linguistics and historical science..."

- Melyukova 1990, pp. 97–98 "From the end of the 7th century B.C. to the 4th century B.C. the Central- Eurasian steppes were inhabited by two large groups of kin Iranian-speaking tribes - the Scythians and Sarmatians..."

- Melyukova (1990, pp. 117) "All contemporary historians, archeologists and linguists are agreed that since the Scythian and Sarmatian tribes were of the Iranian linguistic group..."

- Sulimirski 1985, pp. 149–153 "During the first half of the first millennium B.C., c. 3,000 to 2,500 years ago, the southern part of Eastern Europe was occupied mainly by peoples of Iranian stock... The main Iranian-speaking peoples of the region at that period were the Scyths and the Sarmatians..."

- Jacobson 1995, pp. 36–37 "When we speak of Scythians, we refer to those Scytho-Siberians who inhabited the Kuban Valley, the Taman and Kerch peninsulas, Crimea, the northern and northeastern littoral of the Black Sea, and the steppe and lower forest-steppe regions now shared between Ukraine and Russia, from the seventh century down to the first century B.C... They almost certainly spoke an Iranian language..."

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Harmatta 1996, pp. 181–182

- ^ a b c "Scythian". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|editors=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ a b c Hambly, Gavin [in German]. "History of Central Asia: Early Western Peoples". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|editors=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Beckwith 2009, p. 117 "The Scythians, or Northern Iranians, who were culturally and ethnolinguistically a single group at the beginning of their expansion, had earlier controlled the entire steppe zone."

- ^ Beckwith 2009, pp. 377–380 "The preservation of the earlier form. *Sakla. in the extreme eastern dialects supports the historicity of the conquest of the entire steppe zone by the Northern Iranians—literally, by the 'Scythians'—in the Late Bronze Age or Early Iron Age..."

- ^ a b Beckwith 2009, p. 11

- ^ Young, T. Cuyler. "Ancient Iran: The kingdom of the Medes". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|editors=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Beckwith 2009, p. 49

- ^ "Sarmatian". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|editors=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ a b Brzezinski & Mielczarek 2002, p. 39 "Indeed, it is now accepted that the Sarmatians merged in with pre-Slavic populations."

- ^ a b Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 523 "In their Ukrainian and Polish homeland the Slavs were intermixed and at times overlain by Germanic speakers (the Goths) and by Iranian speakers (Scythians, Sarmatians, Alans) in a shifting array of tribal and national configurations."

- ^ a b c Davis-Kimball, Bashilov & Yablonsky 1995, p. 165 "Iranian-speaking nomadic tribes, specifically the Scythians and Sarmatians, are special among the North Caucasian peoples. The Scytho-Sarmatians were instrumental in the ethnogenesis of some of the modern peoples living today in the Caucasus. Of importance in this group are the Ossetians, an Iranian-speaking group of people who are believed to have descended from the North Caucasian Alans."

- ^ Beckwith 2009, pp. 58–70

- ^ "Scythian art". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|editors=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ a b Nicholson 2018, p. 1346 "Greek authors... frequently applied the name Scythians to later nomadic groups who had no relation whatever to the original Scythians"

- ^ a b Szemerényi 1980

- ^ Lendering, Jona (February 14, 2019). "Scythians / Sacae". Livius.org. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|editors=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Davis-Kimball, Bashilov & Yablonsky 1995, pp. 27–28

- ^ a b c West 2002, pp. 437–440

- ^ Watson 1972, p. 142 "The term 'Scythic' has been used above to denote a group of basic traits which characterize material culture from the fifth to the first century B.C. in the whole zone stretching from the Transpontine steppe to the Ordos, and without ethnic connotation. How far nomadic populations in central Asia and the eastern steppes may be of Scythian, Iranic, race, or contain such elements makes a precarious speculation."

- ^ Bruno & McNiven 2018 "Horse-riding nomadism has been referred to as the culture of 'Early Nomads'. This term encompasses different ethnic groups (such as Scythians, Saka, Massagetae, and Yuezhi)..."

- ^ Davis-Kimball, Bashilov & Yablonsky 1995, p. 33

- ^ Herodotus 1910, 4.11

- ^ Drews 2004, p. 92 "Ever since critical history began, scholars have recognized that much of what Herodotos gives us is silly."

- ^ a b c d Mallory 1991, pp. 51–53

- ^ Dolukhanov 1996, p. 125

- ^ a b Juras, Anna (March 7, 2017). "Diverse origin of mitochondrial lineages in Iron Age Black Sea Scythians". Nature Communications. 7: 43950. doi:10.1038/srep43950. PMC 5339713. PMID 28266657.