Egypt

Arab Republic of Egypt جمهورية مصر العربية Gumhūriyyat Miṣr al-ʿArabiyyah | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: Bilady, Bilady, Bilady | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Cairo |

| Official languages | Arabic1 |

| Demonym(s) | Egyptian |

| Government | Semi-presidential republic |

| Hosni Mubarak | |

| Ahmed Nazif | |

| Establishment | |

| c.3150 BCE | |

• Independence from United Kingdom | February 28 1922 |

• Republic declared | June 18 1953 |

| Area | |

• Total | 1,001,449 km2 (386,662 sq mi) (30th) |

• Water (%) | 0.632 |

| Population | |

• 2007 estimate | 80,335,036 (est.)[1] |

• 1996 census | 59,312,914 |

• Density | 74/km2 (191.7/sq mi) (120th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2006 estimate |

• Total | $329.791 billion (29th) |

• Per capita | $4,836 (110th) |

| Gini (1999–00) | 34.5 medium inequality |

| HDI (2006) | Error: Invalid HDI value (111th) |

| Currency | Egyptian pound (EGP) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Calling code | 20 |

| ISO 3166 code | EG |

| Internet TLD | .eg |

| |

Egypt (Egyptian: Kemet; Coptic: Ⲭⲏⲙⲓ Kīmi; Template:Lang-ar Miṣr ; Egyptian Arabic: [Máṣr] Error: {{Transliteration}}: unrecognized language / script code: ar-EGP (help)), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country in North Africa that includes the Sinai Peninsula, a land bridge to Asia. Covering an area of about 1,001,450 square kilometers (386,660 sq mi), Egypt borders Libya to the west, Sudan to the south, and the Gaza Strip and Israel to the east. The northern coast borders the Mediterranean Sea and the island of Cyprus; the eastern coast borders the Red Sea.

Egypt is one of the most populous countries in Africa. The great majority of its estimated 78 million people (2007) live near the banks of the Nile River in an area of about 40,000 square kilometers (15,000 sq mi) where the only arable agricultural land is found. The large areas of the Sahara Desert are sparsely inhabited. About half of Egypt's residents live in urban areas, with the majority spread across the densely populated centers of greater Cairo, Alexandria and other major cities in the Nile Delta.

Egypt is famous for its ancient civilization and some of the world's most famous monuments, including the Giza pyramid complex and the Great Sphinx. The southern city of Luxor contains numerous ancient artifacts, such as the Karnak Temple and the Valley of the Kings. Egypt is widely regarded as an important political and cultural nation of the Middle East.

Etymology

| ||||

| km.t (Egypt) in hieroglyphs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

One of the ancient Egyptian names of the country, Kemet ([kṃt] Error: {{Transliteration}}: unrecognized language / script code: egy-Latn (help)), or "black land" (from kem "black"), is derived from the fertile black soils deposited by the Nile floods, distinct from the deshret, or "red land" ([dšṛt] Error: {{Transliteration}}: unrecognized language / script code: egy-Latn (help)), of the desert. The name is realized as kīmi and kīmə in the Coptic stage of the Egyptian language, and appeared in early Greek as Template:Polytonic (Khēmía). Another name was t3-mry "land of the riverbank". The names of Upper and Lower Egypt were Ta-Sheme'aw ([t3-šmˁw] Error: {{Transliteration}}: unrecognized language / script code: egy-Latn (help)) "sedgeland" and Ta-Mehew ([t3 mḥw] Error: {{Transliteration}}: unrecognized language / script code: egy-Latn (help)) "northland", respectively.

Miṣr, the Arabic and modern official name of Egypt (Egyptian Arabic: [Maṣr] Error: {{Transliteration}}: unrecognized language / script code: arz-Latn (help)), is of Semitic origin, directly cognate with other Semitic words for Egypt such as the Hebrew Template:Lang-Hebrew2 (Mitzráyim), literally meaning "the two straits" (a reference to the dynastic separation of upper and lower Egypt).[2] The word originally connoted "metropolis" or "civilization" and also means "country", or "frontier-land".

The English name "Egypt" came via the Latin word Aegyptus derived from the ancient Greek word Aígyptos (Αίγυπτος). The adjective aigýpti, aigýptios was borrowed into Coptic as gyptios, kyptios, and from there into Arabic as qubṭī, back formed into qubṭ, whence English Copt. The term is derived from Late Egyptian Hikuptah "Memphis", a corruption of the earlier Egyptian name Hat-ka-Ptah ([ḥwt-k3-ptḥ] Error: {{Transliteration}}: unrecognized language / script code: egy-Latn (help)), meaning "home of the ka (soul) of Ptah", the name of a temple to the god Ptah at Memphis. Strabo provided a folk etymology according to which Aígyptos (Αίγυπτος) had evolved as a compound from Aegaeon uptiōs (Aἰγαίου ὑπτίως), meaning "below the Aegean".

History

The Nile has been a site of continuous human habitation since at least the Paleolithic era. Evidence of this appears in the form of artifacts and rock carvings along the Nile terraces and in the desert oases. In the 10th millennium BC, a culture of hunter-gatherers and fishers replaced a grain-grinding culture. Climate changes and/or overgrazing around 8000 BC began to desiccate the pastoral lands of Egypt, forming the Sahara. Early tribal peoples migrated to the Nile River where they developed a settled agricultural economy and more centralized society.[3]

By about 6000 BC, organized agriculture and large building construction had appeared in the Nile Valley. During the Neolithic era, several predynastic cultures developed independently in Upper and Lower Egypt. The Badarian culture and the successor Naqada series are generally regarded as precursors to Dynastic Egyptian civilization. The earliest known Lower Egyptian site, Merimda, predates the Badarian by about seven hundred years. Contemporaneous Lower Egyptian communities coexisted with their southern counterparts for more than two thousand years, remaining somewhat culturally separate, but maintaining frequent contact through trade. The earliest known evidence of Egyptian hieroglyphic inscriptions appeared during the predynastic period on Naqada III pottery vessels, dated to about 3200 BC.[4]

| ||

| tAwy ('Two Lands') in hieroglyphs | ||

|---|---|---|

A unified kingdom was founded circa 3150 BC by King Menes, giving rise to a series of dynasties that ruled Egypt for the next three millennia. Egyptians subsequently referred to their unified country as tawy, meaning "two lands", and later kemet (Coptic: kīmi), the "black land", a reference to the fertile black soil deposited by the Nile river. Egyptian culture flourished during this long period and remained distinctively Egyptian in its religion, arts, language and customs. The first two ruling dynasties of a unified Egypt set the stage for the Old Kingdom period, c.2700−2200 BC., famous for its many pyramids, most notably the Third Dynasty pyramid of Djoser and the Fourth Dynasty Giza Pyramids.

The First Intermediate Period ushered in a time of political upheaval for about 150 years. Stronger Nile floods and stabilization of government, however, brought back renewed prosperity for the country in the Middle Kingdom c. 2040 BC, reaching a peak during the reign of Pharaoh Amenemhat III. A second period of disunity heralded the arrival of the first foreign ruling dynasty in Egypt, that of the Semitic Hyksos. The Hyksos invaders took over much of Lower Egypt around 1650 BC and founded a new capital at Avaris. They were driven out by an Upper Egyptian force led by Ahmose I, who founded the Eighteenth Dynasty and relocated the capital from Memphis to Thebes.

The New Kingdom (c.1550−1070 BC) began with the Eighteenth Dynasty, marking the rise of Egypt as an international power that expanded during its greatest extension to an empire as far south as Jebel Barkal in Nubia, and included parts of the Levant in the east. This period is noted for some of the most well-known Pharaohs, including Hatshepsut, Thutmose III, Akhenaten and his wife Nefertiti, Tutankhamun and Ramesses II. The first known self-conscious expression of monotheism came during this period in the form of Atenism. Frequent contacts with other nations brought new ideas to the New Kingdom. The country was later invaded by Libyans, Nubians and Assyrians, but native Egyptians drove them out and regained control of their country.

The Thirtieth Dynasty was the last native ruling dynasty during the Pharaonic epoch. It fell to the Persians in 343 BC after the last native Pharaoh, King Nectanebo II, was defeated in battle. Later, Egypt fell to the Greeks and Romans, beginning over two thousand years of foreign rule.

Before Egypt became part of the Byzantine realm, Christianity had been brought by Saint Mark the Evangelist in the AD first century. Diocletian's reign marked the transition from the Roman to the Byzantine era in Egypt, when a great number of Egyptian Christians were persecuted. The New Testament had by then been translated into Egyptian. After the Council of Chalcedon in AD 451, a distinct Egyptian Coptic Church was firmly established.[5]

The Byzantines were able to regain control of the country after a brief Persian invasion early in the seventh century, until in AD 639, Egypt was invaded by the Muslim Arabs. The form of Islam the Arabs brought to Egypt was Sunni. Early in this period, Egyptians began to blend their new faith with indigenous beliefs and practices that had survived through Coptic Christianity, giving rise to various Sufi orders that have flourished to this day.[6] Muslim rulers nominated by the Islamic Caliphate remained in control of Egypt for the next six centuries, including a period for which it was the seat of the Caliphate under the Fatimids. With the end of the Ayyubid dynasty, the Mamluks, a Turco-Circassian military caste, took control about AD 1250. They continued to govern even after the conquest of Egypt by the Ottoman Turks in 1517.

The brief French Invasion of Egypt led by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1798 had a great social impact on the country and its culture. Native Egyptians became exposed to the principles of the French Revolution and had a chance to exercise self-governance.[7] A series of civil wars took place between the Ottoman Turks, the Mamluks, and Albanian mercenaries following the evacuation of French troops, resulting in the Albanian Muhammad Ali (Kavalali Mehmed Ali Pasha) taking control of Egypt. He was appointed as the Ottoman viceroy in 1805. He led a modernization campaign of public works, including irrigation projects, agricultural reforms and increased industrialization, which were then taken up and further expanded by his grandson and successor Isma'il Pasha.

Following the completion of the Suez Canal by Ismail in 1869, Egypt became an important world transportation and trading hub. In 1866, the Assembly of Delegates was founded to serve as an advisory body for the government. Its members were elected from across Egypt. They came to have an important influence on governmental affairs.[8] The country fell heavily into debt to European powers. Ostensibly to protect its investments, the United Kingdom seized control of Egypt's government in 1882. Egypt gave nominal allegiance to the Ottoman Empire until 1914. As a result of the declaration of war with the Ottoman Empire, Britain declared a protectorate over Egypt and deposed the Khedive Abbas II, replacing him with his uncle, Husayn Kamil, who was appointed Sultan.

Between 1882 and 1906, a local nationalist movement for independence was taking shape. The Dinshaway Incident prompted Egyptian opposition to take a stronger stand against British occupation. The first political parties were founded. After the First World War, Saad Zaghlul and the Wafd Party led the Egyptian nationalist movement, gaining a majority at the local Legislative Assembly. When the British exiled Zaghlul and his associates to Malta on March 8, 1919, the country arose in its first modern revolution. Constant revolting by the Egyptian people throughout the country led Great Britain to issue a unilateral declaration of Egypt's independence on February 22, 1922.[9]

The new Egyptian government drafted and implemented a new constitution in 1923 based on a parliamentary representative system. Saad Zaghlul was popularly-elected as Prime Minister of Egypt in 1924. In 1936 the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty was concluded.

Continued instability in the government due to remaining British control and increasing political involvement by the king led to the ouster of the monarchy and the dissolution of the parliament in a military coup d'état known as the 1952 Revolution. The officers, known as the Free Officers Movement, forced King Farouk to abdicate in support of his son Fuad.

On 18 June 1953, the Egyptian Republic was declared, with General Muhammad Naguib as the first President of the Republic. Naguib was forced to resign in 1954 by Gamal Abdel Nasser – the real architect of the 1952 movement – and was later put under house arrest. Nasser assumed power as President and declared the full independence of Egypt from the United Kingdom on June 18 1956. His nationalization of the Suez Canal on July 26 1956 prompted the 1956 Suez Crisis.

Three years after the 1967 Six Day War, during which Israel had invaded and occupied Sinai, Nasser died and was succeeded by Anwar Sadat. Sadat switched Egypt's Cold War allegiance from the Soviet Union to the United States, expelling Soviet advisors in 1972. He launched the Infitah economic reform policy, while violently clamping down on religious and secular opposition alike.

In 1973, Egypt, along with Syria, launched the October War, a surprise attack against the Israeli forces occupying the Sinai Peninsula and the Golan Heights. It was an attempt to liberate the territory Israel had captured 6 years earlier. Both the US and the USSR intervened and a cease-fire was reached. Despite not being a complete military success, most historians agree that the October War presented Sadat with a political victory that later allowed him to pursue peace with Israel.

In 1977, Sadat made a historic visit to Israel, which led to the 1979 peace treaty in exchange for the complete Israeli withdrawal from Sinai. Sadat's initiative sparked enormous controversy in the Arab world and led to Egypt's expulsion from the Arab League, but it was supported by the vast majority of Egyptians.[10] A fundamentalist military soldier assassinated Sadat in Cairo in 1981. He was succeeded by the incumbent Hosni Mubarak. In 2003, the Egyptian Movement for Change, popularly known as Kifaya, was launched to seek a return to democracy and greater civil liberties.

Identity

The Egyptian Nile Valley was home to one of the oldest cultures in the world, spanning three thousand years of continuous history. When Egypt fell under a series of foreign occupations after 343 BC, each left an indelible mark on the country's cultural landscape. Egyptian identity evolved in the span of this long period of occupation to accommodate, in principle, two new religions, Christianity and Islam; and a new language, Arabic, and its spoken descendant, Egyptian Arabic. The degree to which different groups in Egypt identify with these factors in articulating a sense of collective identity can vary.

Questions of identity came to fore in the last century as Egypt sought to free itself from foreign occupation for the first time in two thousand years. Three chief ideologies came to head: ethno-territorial Egyptian nationalism and by extension Pharaonism, secular Arab nationalism and pan-Arabism, and Islamism. Egyptian nationalism predates its Arab counterpart by many decades, having roots in the nineteenth century and becoming the dominant mode of expression of Egyptian anti-colonial activists of the pre- and inter-war periods. It was nearly always articulated in exclusively Egyptian terms:

What is most significant [about Egypt in this period] is the absence of an Arab component in early Egyptian nationalism. The thrust of Egyptian political, economic, and cultural development throughout the nineteenth century worked against, rather than for, an "Arab" orientation... This situation—that of divergent political trajectories for Egyptians and Arabs—if anything increased after 1900.[11]

In 1931, following a visit to Egypt, Syrian Arab nationalist Sati' al-Husri remarked that "[Egyptians] did not possess an Arab nationalist sentiment; did not accept that Egypt was a part of the Arab lands, and would not acknowledge that the Egyptian people were part of the Arab nation."[12] The later 1930s would become a formative period for Arab nationalism in Egypt, in large part due to efforts by Syrian/Palestinian/Lebanese intellectuals.[13] Nevertheless, a year after the establishment of the League of Arab States in 1945, to be headquartered in Cairo, Oxford University historian H. S. Deighton was still writing:

The Egyptians are not Arabs, and both they and the Arabs are aware of this fact. They are Arabic-speaking, and they are Muslim —indeed religion plays a greater part in their lives than it does in those either of the Syrians or the Iraqi. But the Egyptian, during the first thirty years of the [twentieth] century, was not aware of any particular bond with the Arab East... Egypt sees in the Arab cause a worthy object of real and active sympathy and, at the same time, a great and proper opportunity for the exercise of leadership, as well as for the enjoyment of its fruits. But she is still Egyptian first and Arab only in consequence, and her main interests are still domestic.[14]

It was not until the Nasser era more than a decade later that Arab nationalism became a state policy and a means with which to define Egypt's position in the Middle East and the world.[15] usually articulated vis-à-vis Zionism in the neighboring Jewish state.

For a while Egypt and Syria formed the United Arab Republic. When the union was dissolved, the current official name of Egypt was adopted, the Arab Republic of Egypt. Egypt's attachment to Arabism, however, was particularly questioned after its defeat in the 1967 Six-Day War. Thousands of Egyptians had lost their lives and the country become disillusioned with Arab politics.[16] Nasser's successor Sadat, both by policy and through his peace initiative with Israel, revived an uncontested Egyptian orientation, unequivocally asserting that only Egypt was his responsibility. The terms "Arab", "Arabism" and "Arab unity", save for the new official name, became conspicuously absent.[17] Indeed, as professor of Egyptian history P. J. Vatikiotis explains:

...the impact of the October 1973 War (also known as the Ramadan or Yom Kippur War) found Egyptians reverting to an earlier sense of national identity, that of Egyptianism. Egypt became their foremost consideration and top priority in contrast to the earlier one, preferred by the Nasser régime, of Egypt's role and primacy in the Arab world. This kind of national 'restoration' was led by the Old Man of Egyptian Nationalism, Tawfiq el-Hakim, who in the 1920s and 1930s was associated with the Pharaonist movement.[18]

The question of identity continues to be debated today. Many Egyptians feel that Egyptian and Arab identities are linked and not necessarily incompatible. Many others continue to believe that Egypt and Egyptians are simply not Arab. They emphasize indigenous Egyptian heritage, culture and independent polity; point to the failures of Arab nationalist policies; and publicly voice objection to the present official name of the country. Ordinary Egyptians frequently express this sentiment. For example, a foreign tourist said after visiting Egypt,"Although an avowedly Islamic country and now part and parcel of the Arab world, Egyptians are very proud of their distinctiveness and their glorious Pharaonic past dating back to 3500 BC... 'We are not Arabs, we are Egyptians,' said tour guide Shayma, who is a devout Muslim."[19]

In late 2007, el-Masri el-Yom daily newspaper conducted an interview at a bus stop in the working-class district of Imbaba to ask citizens what Arab nationalism (el-qawmeyya el-'arabeyya) represented for them. One Egyptian Muslim youth responded, "Arab nationalism means that the Egyptian Foreign Minister in Jerusalem gets humiliated by the Palestinians, that Arab leaders dance upon hearing of Sadat's death, that Egyptians get humiliated in the Arab Gulf States, and of course that Arab countries get to fight Israel until the last Egyptian soldier."[20] Another felt that,"Arab countries hate Egyptians," and that unity with Israel may even be more of a possibility than Arab nationalism, because he believes that Israelis would at least respect Egyptians.[20]

Some contemporary prominent Egyptians who oppose Arab nationalism or the idea that Egyptians are Arabs include Secretary General of the Supreme Council of Antiquities Zahi Hawass.[21], popular writer Osama Anwar Okasha, Egyptian-born Harvard University Professor Leila Ahmed, Member of Parliament Suzie Greiss[22], in addition to different local groups and intellectuals.[23][24][25][26][27] This understanding is also expressed in other contexts,[28][29] such as Neil DeRosa's novel Joseph's Seed in his depiction of an Egyptian character "who declares that Egyptians are not Arabs and never will be."[30]

Egyptian critics of Arab nationalism contend that it has worked to erode and/or relegate native Egyptian identity by superimposing only one aspect of Egypt's culture. These views and sources for collective identification in the Egyptian state are captured in the words of a linguistic anthropologist who conducted fieldwork in Cairo:

Historically, Egyptians have considered themselves as distinct from 'Arabs' and even at present rarely do they make that identification in casual contexts; il-'arab [the Arabs] as used by Egyptians refers mainly to the inhabitants of the Gulf states... Egypt has been both a leader of pan-Arabism and a site of intense resentment towards that ideology. Egyptians had to be made, often forcefully, into "Arabs" [during the Nasser era] because they did not historically identify themselves as such. Egypt was self-consciously a nation not only before pan-Arabism but also before becoming a colony of the British Empire. Its territorial continuity since ancient times, its unique history as exemplified in its pharaonic past and later on its Coptic language and culture, had already made Egypt into a nation for centuries. Egyptians saw themselves, their history, culture and language as specifically Egyptian and not "Arab."[31]

Politics

National

Egypt has been a republic since 18 June 1953. President Mohamed Hosni Mubarak has been the President of the Republic since October 14 1981, following the assassination of former-President Mohammed Anwar El-Sadat. Mubarak is currently serving his fifth term in office. He is the leader of the ruling National Democratic Party. Prime Minister Dr. Ahmed Nazif was sworn in as Prime Minister on 9 July 2004, following the resignation of Dr. Atef Ebeid from his office.

Although power is ostensibly organized under a multi-party semi-presidential system, whereby the executive power is theoretically divided between the President and the Prime Minister, in practice it rests almost solely with the President who traditionally has been elected in single-candidate elections for more than fifty years. Egypt also holds regular multi-party parliamentary elections. The last presidential election, in which Mubarak won a fifth consecutive term, was held in September 2005.

In late February 2005, President Mubarak announced in a surprise television broadcast that he had ordered the reform of the country's presidential election law, paving the way for multi-candidate polls in the upcoming presidential election. For the first time since the 1952 movement, the Egyptian people had an apparent chance to elect a leader from a list of various candidates. The President said his initiative came "out of my full conviction of the need to consolidate efforts for more freedom and democracy."[32] However, the new law placed draconian restrictions on the filing for presidential candidacies, designed to prevent well-known candidates such as Ayman Nour from standing against Mubarak, and paved the road for his easy re-election victory.[33] Concerns were once again expressed after the 2005 presidential elections about government interference in the election process through fraud and vote-rigging, in addition to police brutality and violence by pro-Mubarak supporters against opposition demonstrators.[34] After the election, Egypt imprisoned Nour, and the U.S. Government stated the “conviction of Mr. Nour, the runner-up in Egypt's 2005 presidential elections, calls into question Egypt's commitment to democracy, freedom, and the rule of law.”[35]

As a result, most Egyptians are skeptical about the process of democratization and the role of the elections. Less than 25 percent of the country's 32 million registered voters (out of a population of more than 78 million) turned out for the 2005 elections.[36] A proposed change to the constitution would limit the president to two seven-year terms in office.[37]

Thirty-four constitutional changes voted on by parliament on March 19, 2007 prohibit parties from using religion as a basis for political activity; allow the drafting of a new anti-terrorism law to replace the emergency legislation in place since 1981, giving police wide powers of arrest and surveillance; give the president power to dissolve parliament; and end judicial monitoring of election. [38] As opposition members of parliament withdrew from voting on the proposed changes, it was expected that the referendum will be boycotted by a great number of Egyptians in protest of what has been considered a breach of democratic practices. Eventually it was reported that only 27% of the registered voters went to the polling stations under heavy police presence and tight political control of the ruling National Democratic Party. It was officially announced on March 27,2007 that 75.9% of those who participated in the referendum approved of the constitutional amendments introduced by President Mubarak and was endorsed by opposition free parliament, thus allowing the introduction of laws that curbs the activity of certain opposition elements particularly Islamists.

Human rights

Several local and international human rights organizations, including Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, have for many years criticized Egypt's human rights record as poor. In 2005, President Hosni Mubarak faced unprecedented public criticism when he clamped down on democracy activists challenging his rule. Some of the most serious human rights violations according to HRW's 2006 report on Egypt are routine torture, arbitrary detentions and trials before military and state security courts.[39]

Discriminatory personal status laws governing marriage, divorce, custody and inheritance which put women at a disadvantage have also been cited. Laws concerning Christians which place restrictions on church building and open worship have been recently eased, but major constructions still require governmental approval and persecution of Christianity by underground radical groups remains a problem.[40] In addition, intolerance of Baha'is and unorthodox Muslim sects remains a problem.[39]

In 2005, the Freedom House rated political rights in Egypt as "6" (1 representing the most free and 7 the least free rating), civil liberties as "5" and gave it the freedom rating of "Not Free."[41] It however noted that "Egypt witnessed its most transparent and competitive presidential and legislative elections in more than half a century and an increasingly unbridled public debate on the country's political future in 2005."[42]

In 2007, human rights group Amnesty International released a report criticizing Egypt for torture and illegal detention. The report alleges that Egypt has become an international center for torture, where other nations send suspects for interrogation, often as part of the War on Terror. The report calls on Egypt to bring its anti-terrorism laws into accordance with international human rights statutes and on other nations to stop sending their detainees to Egypt.[43] Egypt's foreign ministry quickly issued a rebuttal to this report, claiming that it was inaccurate and unfair, as well as causing deep offense to the Egyptian government.[44]

The Egyptian Organization for Human Rights (EOHR) is one of the longest-standing bodies for the defence of human rights in Egypt.[45] In 2003, the government established the National Council for Human Rights, headquartered in Cairo and headed by former UN Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali who directly reports to the president.[46] The council has come under heavy criticism by local NGO activists, who contend it undermines human rights work in Egypt by serving as a propaganda tool for the government to excuse its violations[47] and to provide legitimacy to repressive laws such as the recently renewed Emergency Law.[48] Egypt has recently announced that it is in the process of abolishing the Emergency Law.[49] However, in March 2007 President Mubarak approved several constitutional amendments to include "an anti-terrorism clause that appears to enshrine sweeping police powers of arrest and surveillance", suggesting that the Emergency Law is here to stay for the long haul.[50]

The high court of Egypt has outlawed all religions and belief except Islam, Christianity and Judaism. (For more information see Egyptian Identification Card Controversy.)

Foreign relations

Egypt's foreign policy operates along moderate lines. Factors such as population size, historical events, military strength, diplomatic expertise and a strategic geographical position give Egypt extensive political influence in Africa and the Middle East. Cairo has been a crossroads of regional commerce and culture for centuries, and its intellectual and Islamic institutions are at the center of the region's social and cultural development.

The permanent Headquarters of the Arab League are located in Cairo and the Secretary General of the Arab League has traditionally been an Egyptian. Former Egyptian Foreign Minister Amr Moussa is the current Secretary General. The Arab League briefly moved from Egypt to Tunis in 1978, as a protest to the signing by Egypt of a peace treaty with Israel, but returned in 1989.

Egypt was the first Arab state to establish diplomatic relations with Israel, with the signing of the Egypt-Israel Peace Treaty in 1979. Egypt has a major influence amongst other Arab states, and has historically played an important role as a mediator in resolving disputes between various Arab states, and in the Israeli-Palestinian dispute. Most Arab states still give credence to Egypt playing that role, though its effects are often limited and recently challenged by Saudi Arabia and oil rich Gulf States. It is also reported that due to Egypt's indulgence in internal problems and its reluctance to play a positive role in regional matters had lost the country great influence in Africa and the neighbouring countries.

Former Egyptian Deputy Prime Minister Boutros Boutros-Ghali served as Secretary General of the United Nations from 1991 to 1996.

Governorates

Egypt is divided into twenty-six governorates (muhafazat, singular muhafazah). The governorates are further divided into regions (markazes).

|

|

Economy

Egypt's economy depends mainly on agriculture, media, petroleum exports, and tourism; there are also more than three million Egyptians working abroad, mainly in Saudi Arabia, the Persian Gulf and Europe. The completion of the Aswan High Dam in 1971 and the resultant Lake Nasser have altered the time-honored place of the Nile River in the agriculture and ecology of Egypt. A rapidly-growing population, limited arable land, and dependence on the Nile all continue to overtax resources and stress the economy.

The government has struggled to prepare the economy for the new millennium through economic reform and massive investments in communications and physical infrastructure. Egypt has been receiving U.S. foreign aid (since 1979, an average of $2.2 billion per year) and is the third-largest recipient of such funds from the United States following the Iraq war. Its main revenues however come from tourism as well as traffic that goes through the Suez Canal.

Egypt has a developed energy market based on coal, oil, natural gas, and hydro power. Substantial coal deposits are in the north-east Sinai, and are mined at the rate of about 600,000 metric tons (590,000 long tons; 660,000 short tons) per year. Oil and gas are produced in the western desert regions, the Gulf of Suez, and the Nile Delta. Egypt has huge reserves of gas, estimated at over 1,100,000 cum[convert: unknown unit] in the 1990s, and LNG is exported to many countries.

Economic conditions have started to improve considerably after a period of stagnation from the adoption of more liberal economic policies by the government, as well as increased revenues from tourism and a booming stock market. In its annual report, the IMF has rated Egypt as one of the top countries in the world undertaking economic reforms. Some major economic reforms taken by the new government since 2003 include a dramatic slashing of customs and tariffs. A new taxation law implemented in 2005 decreased corporate taxes from 40% to the current 20%, resulting in a stated 100% increase in tax revenue by the year 2006.

FDI (Foreign Direct Investment) into Egypt has increased considerably in the past few years due to the recent economic liberalization measures taken by minister of investment Mahmoud Mohieddin, exceeding $6 billion in 2006. Egypt is slated to overcome South Africa as the highest earner of FDI on the African continent in 2007.

Although one of the main obstacles still facing the Egyptian economy is the trickle down of the wealth to the average population, many Egyptians criticize their government for higher prices of basic goods while their standards of living or purchasing power remains relatively stagnant. Often corruption is blamed by Egyptians as the main impediment to feeling the benefits of the newly attained wealth. Major reconstruction of the country's infrastructure is promised by the government, with a large portion of the sum paid for the newly acquired 3rd mobile license ($3 billion) by Etisalat. This is slated to be pumped into the country's railroad system, in response to public outrage against the government for disasters in 2006 that claimed more than 100 lives.

The best known examples of Egyptian companies that have expanded regionally and globally are the Orascom Group and Raya. The IT sector has been expanding rapidly in the past few years, with many new start-ups conducting outsourcing business to North America and Europe, operating with companies such as Microsoft, Oracle and other major corporations, as well as numerous SME's. Some of these companies are the Xceed Contact Center, Raya Contact Center, E Group Connections and C3 along with other start ups in that country. The sector has been stimulated by new Egyptian entrepreneurs trying to capitalize on their country's huge potential in the sector, as well as constant government encouragement.

Demographics

Egypt is the most populated country in the Middle East and the second-most populous on the African continent, with an estimated 78 million people. Almost all the population is concentrated along the banks of the Nile (notably Cairo and Alexandria), in the Delta and near the Suez Canal. Approximately 80-90% of the population adheres to Islam and most of the remainder to Christianity, primarily the Coptic Orthodox denomination.[51] Apart from religious affiliation, Egyptians can be divided demographically into those who live in the major urban centers and the fellahin or farmers of rural villages. The last 40 years have seen a rapid increase in population due to medical advances and massive increase in agricultural productivity,[52] made by the Green Revolution.[53]

Egyptians are by far the largest ethnic group in Egypt at 94% (about 72.5 million) of the total population.[51] Ethnic minorities include the Bedouin Arab tribes living in the eastern deserts and the Sinai Peninsula, the Berber-speaking Siwis (Amazigh) of the Siwa Oasis, and the ancient Nubian communities clustered along the Nile. There are also tribal communities of Beja concentrated in the south-eastern-most corner of the country, and a number of Dom clans mostly in the Nile Delta and Faiyum who are progressively becoming assimilated as urbanization increases.

Egypt also hosts an unknown number of refugees and asylum seekers. According to the UNDP's 2004 Human Development Report, there were 89,000 refugees in the country,[54] though this number may be an underestimate. There are some 70,000 Palestinian refugees,[54] and about 150,000 recently arrived Iraqi refugees,[55] but the number of the largest group, the Sudanese, is contested.[56] The once-vibrant Jewish community in Egypt has virtually disappeared, with only a small number remaining in the country, but many Egyptian Jews visit on religious occasions and for tourism. Several important Jewish archaeological and historical sites are found in Cairo, Alexandria and other cities.

Religion

Religion plays a central role in most Egyptians' lives. The rolling calls to prayer that are heard five times a day have the informal effect of regulating the pace of everything from business to entertainment. Cairo is famous for its numerous mosque minarets and church towers. This religious landscape has been marred by a record of religious extremism.[57] Most recently, a 16 December 2006 judgment of the Supreme Administrative Court of Egypt insisted on a clear demarcation between "recognized religions"—Islam, Christianity and Judaism—and all other religious beliefs—thus effectively delegitimatizing and forbidding practice of all but these aforementioned religions.[58] This judgment has led to the requirement for communities to either commit perjury or be subjected to denial of identification cards.

Egypt is predominantly Muslim, at 80-90% of the population, with the majority being adherents of the Sunni branch of Islam.[51] A significant number of Muslim Egyptians also follow native Sufi orders,[59] and a minority of Shi'a.

Christians represent 10-20% of the population,[60] more than 95% of whom belong to the native Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria. Other native Egyptian Christians are adherents of the Coptic Catholic Church, the Coptic Evangelical Church and various Coptic Protestant denominations. Non-native Christian communities are largely found in the urban regions of Alexandria and Cairo, and are members of the Greek Orthodox Church of Alexandria, the Melkite Greek Catholic Church, the Armenian Apostolic Church, the Roman Catholic Church, the Episcopal Church in Jerusalem and the Middle East, the Maronite Church, the Armenian Catholic Church, the Chaldean Catholic Church, the Syriac Catholic Church, or the Syriac Orthodox Church.

According to the Constitution of Egypt, any new legislation must at least implicitly agree with Islamic laws. The mainstream Hanafi school of Sunni Islam is largely organised by the state, through Wizaret Al-Awkaf (Ministry of Religious Affairs). Al-Awkaf controls all mosques and overviews Muslim clerics. Imams are trained in Imam vocational schools and at Al-Azhar University. The department supports Sunni Islam and has commissions authorised to give Fatwa judgements on Islamic issues.

Egypt hosts two major religious institutions. Al-Azhar University (Template:Lang-ar) is the oldest Islamic institution of higher studies (founded around 970 A.D) and considered by many to be the oldest extant university. The Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria, headed by the Pope of the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria, attests to Egypt's strong Christian heritage. It has a following of approximately 15 million Christians worldwide; affiliated sister churches are located in Armenia, Ethiopia, Eritrea, India, Lebanon and Syria.

Religious freedom in Egypt is hampered to varying degrees by extremist Islamist groups and by discriminatory and restrictive government policies. Being the largest religious minority in Egypt, Coptic Christians are the most negatively affected community. Copts have faced increasing marginalization after the 1952 coup d'état led by Gamal Abdel Nasser. Until recently, Christians were required to obtain presidential approval for even minor repairs in churches. Although the law was eased in 2005 by handing down the authority of approval to the governors, Copts continue to face many obstacles in building new or repairing existing churches. These obstacles are not found in building mosques.[61][62]

In addition, Copts complain of being minimally represented in law enforcement, state security and public office, and of being discriminated against in the workforce on the basis of their religion.[63] The Coptic community, as well as several human rights activists and intellectuals (such as Saad Eddin Ibrahim and Tarek Heggy), maintain that the number of Christians occupying government posts is not proportional to the number of Copts in Egypt, who constitute between 10 and 15% of the population in Egypt. Of the 32 cabinet ministers, two are Copts: Finance Minister Youssef Boutros Ghali and Minister of Environment Magued George; and of the 25 local governors, only one is a Copt (in the Upper Egyptian governorate of Qena). However, Copts have demonstrated great success in Egypt's private business sector; Naguib Sawiris, an extremely successful businessman and one of the world's wealthiest 100 people is a Copt. In 2002, under the Mubarak government, Coptic Christmas (January 7) was recognized as an official holiday.[64] Nevertheless, the Coptic community has occasionally been the target of hate crimes and physical assaults. The most significant was the 2000-2001 El Kosheh attacks , in which 21 Copts and one Muslim were killed. A 2006 attack on three churches in Alexandria left one dead and 17 injured, although the attacker was not linked to any organisation.[65]

Egypt was once home to one of the oldest Jewish communities in the world. Egyptian Jews, who were mostly Karaites, partook of all aspects of Egypt's social, economic and political life; one of the most ardent Egyptian nationalists, Yaqub Sanu' (Abu Naddara), was a Jew, as were famous musician Dawoud Husni, popular singer Leila Mourad, and prominent filmmaker Togo Mizrahi. For a while, Jews from across the Ottoman Empire and Europe were attracted to Egypt due to the relative harmony that characterized the local religious landscape in the 19th and early 20th centuries. After the 1956 Suez Crisis, a great number of Jews were expelled by Gamal Abdel Nasser, many of whom holding official Egyptian citizenship. Their Egyptian citizenship was revoked and their property was confiscated. A steady stream of migration of Egyptian Jews followed, reaching a peak after the Six-Day War with Israel in 1967. Today, Jews in Egypt number less than 500.[66]

Bahá'ís in Egypt, whose population is estimated to be a couple of thousands, have long been persecuted, having their institutions and community activities banned. Since their faith is not officially recognized by the state, they are also not allowed to use it on their national identity cards (conversely, Islam, Christianity, and Judaism are officially recognized); hence most of them do not hold national identity cards. In April 2006 a court case recognized the Bahá'í Faith, but the government appealed the court decision and succeeded in having it suspended on 15 May, 2006.[67] On December 16, 2006, only after one hearing, the Supreme Administrative Council of Egypt ruled against the Bahá'ís, stating that the government may not recognize the Bahá'í Faith in official identification documents.[58]

There are Egyptians who identify as atheist and agnostic, but their numbers are largely unknown as openly advocating such positions risks legal sanction on the basis of apostasy (if a citizen takes the step of suing the 'apostating' person, though not automatically by the general prosecutor). In 2000, an openly atheist Egyptian writer, who called for the establishment of a local association for atheists, was tried on charges of insulting Islam in four of his books.[68]

While freedom of religion is guaranteed by the Egyptian constitution, according to Human Rights Watch, "Egyptians are able to convert to Islam generally without difficulty, but Muslims who convert to Christianity face difficulties in getting new identity papers and some have been arrested for allegedly forging such documents.[69] The Coptic community, however, takes pains to prevent conversions from Christianity to Islam due to the ease with which Christians can often become Muslim. [70] Public officials, being conservative themselves, intensify the complexity of the legal procedures required to recognize the religion change as required by law. Security agencies will sometimes claim that such conversions from Islam to Christianity (or occasionally vice versa) may stir social unrest, and thereby justify themselves in wrongfully detaining the subjects, insisting that they are simply taking steps to prevent likely social troubles from happening.[71] Recently, a Cairo administrative court denied 45 citizens the right to obtain identity papers documenting their reversion to Christianity after converting to Islam.[72]

Culture

Egyptian culture has five thousand years of recorded history. Ancient Egypt was among the earliest civilizations and for millennia, Egypt maintained a strikingly complex and stable culture that influenced later cultures of Europe, the Middle East and Africa. After the Pharaonic era, Egypt itself came under the influence of Hellenism, Christianity, and Islamic culture. Today, many aspects of Egypt's ancient culture exist in interaction with newer elements, including the influence of modern Western culture, itself with roots in ancient Egypt.

Egypt's capital city, Cairo, is Africa's largest city and has been renowned for centuries as a center of learning, culture and commerce. Egypt has the highest number of Nobel Laureates in Africa and the Arab World. Some Egyptian born politicians were or are currently at the helm of major international organizations like Boutros Boutros-Ghali of the United Nations and Mohamed ElBaradei of the IAEA.

Renaissance

The work of early nineteenth-century scholar Rifa'a et-Tahtawi gave rise to the Egyptian Renaissance, marking the transition from Medieval to Early Modern Egypt. His work renewed interest in Egyptian antiquity and exposed Egyptian society to Enlightenment principles. Tahtawi co-founded with education reformer Ali Mubarak a native Egyptology school that looked for inspiration to medieval Egyptian scholars, such as Suyuti and Maqrizi, who themselves studied the history, language and antiquities of Egypt.[73] Egypt's renaissance peaked in the late 19th and early 20th centuries through the work of people like Muhammad Abduh, Ahmed Lutfi el-Sayed, Qasim Amin, Salama Moussa, Taha Hussein and Mahmoud Mokhtar. They forged a liberal path for Egypt expressed as a commitment to individual freedom, secularism and faith in science to bring progress.[74]

Arts

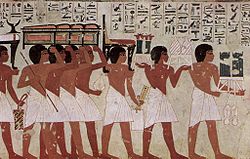

The Egyptians were one of the first major civilizations to codify design elements in art. The wall paintings done in the service of the Pharaohs followed a rigid code of visual rules and meanings. Modern and contemporary Egyptian art can be as diverse as any works in the world art scene. The Cairo Opera House serves as the main performing arts venue in the Egyptian capital. Egypt's media and arts industry has flourished since the late nineteenth century, today with more than thirty satellite channels and over one hundred motion pictures produced each year. Cairo has long been known as the "Hollywood of the Middle East;" its annual film festival, the Cairo International Film Festival, has been rated as one of 11 festivals with a top class rating worldwide by the International Federation of Film Producers' Associations.[75] To bolster its media industry further, especially with the keen competition from the Persian Gulf Arab States and Lebanon, a large media city was built. Some Egyptian actors, like Omar Sharif, have achieved worldwide fame.

Literature

Literature constitutes an important cultural element in the life of Egypt. Egyptian novelists and poets were among the first to experiment with modern styles of Arabic literature, and the forms they developed have been widely imitated throughout the Middle East. The first modern Egyptian novel Zaynab by Muhammad Husayn Haykal was published in 1913 in the Egyptian vernacular.[76] Egyptian novelist Naguib Mahfouz was the first Arabic-language writer to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. Egyptian women writers include Nawal El Saadawi, well known for her feminist activism, and Alifa Rifaat who also writes about women and tradition. Vernacular poetry is perhaps the most popular literary genre amongst Egyptians, represented by such luminaries as Ahmed Fuad Nigm (Fagumi), Salah Jaheen and Abdel Rahman el-Abnudi.

Music

Egyptian music is a rich mixture of indigenous, Mediterranean, African and Western elements. In antiquity, Egyptians were playing harps and flutes, including two indigenous instruments: the ney and the oud. Percussion and vocal music also became an important part of the local music tradition ever since. Contemporary Egyptian music traces its beginnings to the creative work of people such as Abdu-l Hamuli, Almaz and Mahmud Osman, who influenced the later work of Egyptian music giants such as Sayed Darwish, Umm Kulthum, Mohammed Abdel Wahab and Abdel Halim Hafez. These prominent artists were followed later by Amr Diab. He is seen by many as the new age "Musical Legend", whose fan base stretches all over the Middle East and Europe. From the 1970s onwards, Egyptian pop music has become increasingly important in Egyptian culture, while Egyptian folk music continues to be played during weddings and other festivities.

Festivals

Egypt is famous for its many festivals and religious carnivals, also known as mulids or Mawlid. They are usually associated with a particular Coptic or Sufi saint, but are often celebrated by all Egyptians irrespective of creed or religion. Ramadan has a special flavor in Egypt, celebrated with sounds, lights (local lanterns known as fawanees) and much flare that many Muslim tourists from the region flock to Egypt during Ramadan to witness the spectacle. The ancient spring festival of Sham en Nisim (Coptic: Ϭⲱⲙ‘ⲛⲛⲓⲥⲓⲙ shom en nisim) has been celebrated by Egyptians for thousands of years, typically between the Egyptian months of Paremoude (April) and Pashons (May), following Easter Sunday.

Sports

Football (soccer) is the de facto national sport of Egypt. Egyptian Soccer clubs El Ahly and El Zamalek are the two most popular teams and enjoy the reputation of long-time regional champions. The great rivalries keep the streets of Egypt energized as people fill the streets when their favourite team wins. Egypt is rich in soccer history as soccer has been around for over 100 years. The country is home to many African championships such as the African Cup of Nations. However, Egypt's national team has not qualified for the FIFA World Cup since 1990.

Squash and tennis are other favourite sports. The Egyptian squash team has been known for its fierce competition in international championships since the 1930s.

Military

The Egyptian Armed forces have a combined troop strength of around 450,000 active personnel.[77] According to the Israeli chair of the Knesset Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee, Yuval Steinitz, the Egyptian Air Force has roughly the same number of modern warplanes as the Israeli Air Force and far more Western tanks, artillery, anti-aircraft batteries and warships than the IDF.[78] The Egyptian military has recently undergone massive military modernization mostly in their Air Force. Other than Israel, Egypt is the first country in the region with a spy satellite, EgyptSat 1, and is planning to launch 3 more spy satellites (DesertSat1, EgyptSat2, DesertSat2) over the next two years.[79]

Geography

At 1,001,450 square kilometers (386,660 sq mi),[80] Egypt is the world's 38th-largest country (after Mauritania). It is comparable in size to Tanzania, twice the size of France, four times the size of the United Kingdom, and is more than half the size of the US state of Alaska.

Nevertheless, due to the aridity of Egypt's climate, population centres are concentrated along the narrow Nile Valley and Delta, meaning that approximately 99% of the population uses only about 5.5% of the total land area.[81]

Egypt is bordered by Libya to the west, Sudan to the south, and by the Gaza Strip and Israel to the east. Egypt's important role in geopolitics stems from its strategic position: a transcontinental nation, it possesses a land bridge (the Isthmus of Suez) between Africa and Asia, which in turn is traversed by a navigable waterway (the Suez Canal) that connects the Mediterranean Sea with the Indian Ocean via the Red Sea.

Apart from the Nile Valley, the majority of Egypt's landscape is a sandy desert. The winds blowing can create sand dunes over 100 feet (30 m) high. Egypt includes parts of the Sahara Desert and of the Libyan Desert. These deserts were referred to as the "red land" in ancient Egypt, and they protected the Kingdom of the Pharaohs from western threats.

Towns and cities include Alexandria, one of the greatest ancient cities, Aswan, Asyut, Cairo, the modern Egyptian capital, El-Mahalla El-Kubra, Giza, the site of the Pyramid of Khufu, Hurghada, Luxor, Kom Ombo, Port Safaga, Port Said, Sharm el Sheikh, Suez, where the Suez Canal is located, Zagazig, and Al-Minya. Oases include Bahariya, el Dakhla, Farafra, el Kharga and Siwa.

Protectorates include Ras Mohamed National Park, Zaranik Protectorate and Siwa. See Egyptian Protectorates for more information.

Climate

Egypt receives the least rainfall in the world. South of Cairo, rainfall averages only around 2 to 5 mm (0.1 to 0.2 in) per year and at intervals of many years. On a very thin strip of the northern coast the rainfall can be as high as 170 mm (7 in), all between November and March. Snow falls on Sinai's mountains and some of the north coastal cities such as Damietta, Baltim, Sidi Barrany, etc. and rarely in Alexandria, frost is also known in mid-Sinai and mid-Egypt.

Temperatures average between 80 °F (27 °C) and 90 °F (32 °C) in summer, and up to 109 °F (43 °C) on the Red Sea coast. Temperatures average between 55 °F (13 °C) and 70 °F (21 °C) in winter. A steady wind from the northwest helps hold down the temperature near the Mediterranean coast. The Khamaseen is a wind that blows from the south in Egypt in spring, bringing sand and dust, and sometimes raises the temperature in the desert to more than 100 °F (38 °C).

See also

Column-generating template families

The templates listed here are not interchangeable. For example, using {{col-float}} with {{col-end}} instead of {{col-float-end}} would leave a <div>...</div> open, potentially harming any subsequent formatting.

| Type | Family | Handles wiki

table code?† |

Responsive/ mobile suited |

Start template | Column divider | End template |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Float | "col-float" | Yes | Yes | {{col-float}} | {{col-float-break}} | {{col-float-end}} |

| "columns-start" | Yes | Yes | {{columns-start}} | {{column}} | {{columns-end}} | |

| Columns | "div col" | Yes | Yes | {{div col}} | – | {{div col end}} |

| "columns-list" | No | Yes | {{columns-list}} (wraps div col) | – | – | |

| Flexbox | "flex columns" | No | Yes | {{flex columns}} | – | – |

| Table | "col" | Yes | No | {{col-begin}}, {{col-begin-fixed}} or {{col-begin-small}} |

{{col-break}} or {{col-2}} .. {{col-5}} |

{{col-end}} |

† Can template handle the basic wiki markup {| | || |- |} used to create tables? If not, special templates that produce these elements (such as {{(!}}, {{!}}, {{!!}}, {{!-}}, {{!)}})—or HTML tags (<table>...</table>, <tr>...</tr>, etc.)—need to be used instead.

Lists

- List of Rulers and heads of state of Egypt

- List of writers from Egypt

- List of Egyptian companies

- List of Egypt-related topics

- List of Egyptians

- List of Egyptian universities

Notes and references

- ^ "Egypt" in the CIA World Factbook, 2007.

- ^ Biblical Hebrew E-Magazine. January, 2005

- ^ Midant-Reynes, Béatrix. The Prehistory of Egypt: From the First Egyptians to the First Kings. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

- ^ Bard, Kathryn A. Ian Shaw, ed. The Oxford Illustrated History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. p. 69.

- ^ Kamil, Jill. Coptic Egypt: History and Guide. Cairo: American University in Cairo, 1997. p. 39

- ^ El-Daly, Okasha. Egyptology: The Missing Millennium. London: UCL Press, 2005. p. 140

- ^ Vatikiotis, P.J. The History of Modern Egypt. 4th edition. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 1992, p. 39

- ^ Jankowski, James. Egypt: A Short History. Oxford: Oneworld Publications, 2000. p. 83

- ^ Jankowski, op cit., p. 112

- ^ Vatikiotis, p. 443

- ^ Jankowski, James. "Egypt and Early Arab Nationalism" in Rashid Khalidi, ed. The Origins of Arab Nationalism. New York: Columbia University Press, 1990, pp. 244-45

- ^ qtd in Dawisha, Adeed. Arab Nationalism in the Twentieth Century. Princeton University Press. 2003, p. 99

- ^ Jankowski, "Egypt and Early Arab Nationalism," p. 246

- ^ Deighton, H. S. "The Arab Middle East and the Modern World", International Affairs, vol. xxii, no. 4 (October 1946), p. 519.

- ^ "Before Nasser, Egypt, which had been ruled by Britain since 1882, was more in favor of territorial, Egyptian nationalism and distant from the pan-Arab ideology. Egyptians generally did not identify themselves as Arabs, and it is revealing that when the Egyptian nationalist leader [Saad Zaghlul] met the Arab delegates at Versailles in 1918, he insisted that their struggles for statehood were not connected, claiming that the problem of Egypt was an Egyptian problem and not an Arab one." Makropoulou, Ifigenia. Pan - Arabism: What Destroyed the Ideology of Arab Nationalism?. Hellenic Center for European Studies. January 15, 2007.

- ^ Dawisha, p. 237

- ^ Dawisha, pp. 264-65, 267

- ^ Vatikiotis, p. 499

- ^ In Egypt, India is Big B!. Hindustan Times. December 25, 2006.

- ^ a b Ragab, Ahmed. El-Masry el-Yom Newspaper. "What is the definition of 'Arab Nationalism': Question at a bus stop in Imbaba". May 21, 2007.

- ^ In an audio interview on Egypt's links with Sub-Saharan Africa and the Arab world, Hawass believes that "even today Egyptians are Egyptians. It really doesn't mean that because we speak Arabic that we can be Arabs. We are...really, I feel personally that we are related even today to the Pharaohs."

- ^ An Interculturalist in Cairo. InterCultures Magazine. January 2007.

- ^ Kimit Sagi Template:Ar icon

- ^ We are Egyptians, not Arabs. ArabicNews.com. 11/06.2003.

- ^ Ghobrial, Kamal. Egypt, the Arabs and Arabism. el-Ahali. August 31-September 6, 2005. Template:Ar icon

- ^ Said Habeeb's Masreyat. Template:Ar icon

- ^ Egyptian national group Template:Ar icon

- ^ Egyptian people section from Arab.Net

- ^ Princeton Alumni Weekly

- ^ Review by Michelle Fram Cohen. The Atlasphere. Jan. 17, 2005.

- ^ Haeri, Niloofar. Sacred language, Ordinary People: Dilemmas of Culture and Politics in Egypt. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. 2003, pp. 47, 136.

- ^ Business TodayEGYPT. Mubarak throws presidential race wide open. March 2005.

- ^ Lavin, Abigail. Democracy on the Nile: The story of Ayman Nour and Egypt's problematic attempt at free elections. March 27, 2006.

- ^ Murphy, Dan. Egyptian vote marred by violence. Christian Science Monitor. May 26, 2005.

- ^ United States "Deeply Troubled" by Sentencing of Egypt's Nour. U.S. Department of State, Published December 24, 2005

- ^ Gomez, Edward M. Hosni Mubarak's pretend democratic election. San Francisco Chronicle. September 13, 2005.

- ^ Egypt to begin process of lifting emergency laws. December 5, 2006.

- ^ Anger over Egypt vote timetable BBC News.

- ^ a b Human Rights Watch. Egypt: Overview of human rights issues in Egypt. 2005

- ^ Church Building Regulations Eased

- ^ "Freedom in the World 2006" (PDF). Freedom House. 2005-12-16. Retrieved 2006-07-27.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

See also Freedom in the World 2006, List of indices of freedom - ^ Freedom House. Freedom in the World - Egypt. 2006

- ^ Egypt torture centre, report says. bbc.co.uk. Written 2007-4-11. Accessed 2007-4-11.

- ^ Egypt rejects torture criticism. bbc.co.uk. Written 2007-4-13. Accessed 2007-4-13.

- ^ Egyptian Organization for Human Rights

- ^ Official page of the Egyptian National Council for Human Rights.

- ^ Egyptian National Council for Human Rights Against Human Rights NGOs. EOHR. June 3, 2003.

- ^ Qenawy, Ahmed. The Egyptian Human Rights Council: The Apple Falls Close to the Tree. ANHRI. 2004

- ^ Egypt to begin process of lifting emergency laws. December 5, 2006.

- ^ Egypt parliament approves changes in constitution. Reuters. March 20, 2007.

- ^ a b c "Egyptian people section from the World Factbook". World Fact Book. Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- ^ BBC NEWS | The limits of a Green Revolution?

- ^ Food First/Institute for Food and Development Policy

- ^ a b UNDP, p. 75.

- ^ Iraq: from a Flood to a Trickle: Egypt

- ^ See The U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants for a lower estimate. The The Egyptian Organization for Human Rights states on its web site that in 2000 the World Council of Churches claimed that "between two and five million Sudanese have come to Egypt in recent years". Most Sudanese refugees come to Egypt in the hope of resettling in Europe or the US.

- ^ U.S. Department of State (2004-09-15). "Egypt: International Religious Freedom Report". Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. Retrieved 2006-10-20.

- ^ a b Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights (2006-12-16). "Government Must Find Solution for Baha'i Egyptians". eipr.org. Retrieved 2006-12-16.

- ^ Hoffman, Valerie J. Sufism, Mystics, and Saints in Modern Egypt. University of South Carolina Press, 1995.

- ^ Wahington Institute (Citing pop. estimates)

- ^ WorldWide Religious News. Church Building Regulations Eased. December 13, 2005.

- ^ Compass Direct News. Church Building Regulations Eased. December 13, 2005.

- ^ Human Rights Watch. Egypt: Overview of human rights issues in Egypt. 2005

- ^ ArabicNews.com. Copts welcome Presidential announcement on Eastern Christmas Holiday. December 20, 2002.

- ^ BBC. Egypt church attacks spark anger, 15 April 2006.

- ^ Jewish Community Council (JCC) of Cairo. Bassatine News. 2006.

- ^ "EGYPT: Court suspends ruling recognising Bahai rights". Payvand's Iran News. 2006-5-17.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Halawi, Jailan (21-27 December 2000). "Limits to expression". Al-Ahram Weekly.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Human Rights Watch. World report 2007: Egypt.

- ^ EGYPT: NATIONAL UNITY AND THE COPTIC ISSUE. 2004

- ^ Egypt: Egypt Arrests 22 Muslim converts to Christianity. 03 November, 2003

- ^ Shahine, Gihan. "Fraud, not Freedom". Ahram Weekly, 3 - 9 May 2007

- ^ El-Daly, op cit., p. 29

- ^ Jankowski, op cit., p. 130

- ^ Cairo Film Festival information.

- ^ Vatikiotis, op cit.

- ^ Egypt Military Strength

- ^ Steinitz, Yuval. Not the peace we expected. Haaretz. December 05, 2006.

- ^ Katz, Yaacov. "Egypt to launch first spy satellite," Jerusalem Post, January 15, 2007.

- ^ World Factbook area rank order

- ^ Hamza, Waleed. Land use and Coastal Management in the Third Countries: Egypt as a case. Accessed= 2007-06-10.

General references

- Template:CIAfb

This article incorporates public domain material from U.S. Bilateral Relations Fact Sheets. United States Department of State.

This article incorporates public domain material from U.S. Bilateral Relations Fact Sheets. United States Department of State.

External links

- Leonard William King, History of Egypt, Chaldæa, Syria, Babylonia, and Assyria in the Light of Recent Discovery, Project Gutenberg.

- Gaston Camille Charles Maspero, History of Egypt, Chaldæa, Syria, Babylonia, and Assyria, in 12 volumes, Project Gutenberg.

- Ancient Egyptian Civilization - Aldokkan

- Rural poverty in Egypt (IFAD)

- Encyclopaedia Britannica's Egypt Country Page

- Egyptian Government Services Portal

- New Projects in Egypt

- Egypt State Information Services

- Egypt Information Portal - available in Arabic and English

- BBC News Country Profile - Egypt

- CIA World Factbook - Egypt

- Amnesty International's 2005 Report on Egypt.

- US State Department - Egypt includes Background Notes, Country Study and major reports

- Business Anti-Corruption Portal Egypt Country Profile

- Congressional Research Service (CRS) Reports regarding Egypt

- Template:Dmoz

- Template:Wikitravel

- Egypt Maps - Perry-Castañeda Map Collection

- Egyptian History (urdu)

- By Nile and Tigris, a narrative of journeys in Egypt and Mesopotamia on behalf of the British museum between the years 1886 and 1913, by Sir E. A. Wallis Budge, 1920 (a searchable facsimile at the University of Georgia Libraries; DjVu & layered PDF format)

- Egypt Online Directory

- The Egyptian Organization for Human Rights

- PortSaid Free-zone forums