Lima

Lima | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Nickname(s): La ciudad de los reyes (The City of the Kings), La gris (The gray one)

- | |

| Motto: Hoc signum vere regum est (This is the real sign of the kings) | |

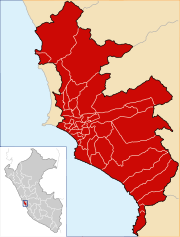

Lima Province and Lima within Peru | |

| Country | Peru |

| Region | autonomous |

| Province | Lima Province |

| Districts | 43 districts |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–council government |

| • Mayor | Luis Castañeda |

| Area | |

| • City | 2,672.3 km2 (1,031.8 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 800 km2 (300 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,819.3 km2 (1,088.5 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 0−1,550 m (0−5,090 ft) |

| Population (2015)[2] | |

| • City | 8,852,000 |

| • Density | 3,300/km2 (8,600/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 9,752,000 |

| • Metro density | 3,500/km2 (9,000/sq mi) |

| • Demonym | Limean (Spanish: Limeño/a) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (PET) |

| Website | www.munlima.gob.pe |

Lima /ˈliːmə/ is the capital and the largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón, Rímac and Lurín rivers, in the central coastal part of the country, overlooking the Pacific Ocean. Together with the seaport of Callao, it forms a contiguous urban area known as the Lima Metropolitan Area. With a population of almost 10 million, Lima is the most populous metropolitan area of Peru, and the third largest city in the Americas (as defined by "city proper").

Lima was founded by Spanish conquistador Francisco Pizarro on January 18, 1535, as Ciudad de los Reyes. It became the capital and most important city in the Spanish Viceroyalty of Peru. Following the Peruvian War of Independence, it became the capital of the Republic of Peru. Today, around one-third of the Peruvian population lives in the metropolitan area.

Lima is home to one of the oldest higher learning institutions in the New World. The National University of San Marcos, founded on May 12 of 1551, during Spanish colonial regime, is the oldest continuously functioning university in the Americas.

In October 2013, Lima was chosen in a ceremony in Toronto to host the 2019 Pan American Games. It also hosted the 2014 United Nations Climate Change Conference in December of that year.

Etymology

According to early Spanish chronicles the Lima area was once called Itchyma, after its original inhabitants. However, even before the Inca occupation of the area in the 15th century, a famous oracle in the Rímac valley had come to be known by visitors as Limaq (Limaq, pronounced [ˈli.mɑq], which means "talker" in coastal Quechua). This oracle was eventually destroyed by the Spanish and replaced with a church, but the name persisted in the local language, and so the chronicles show "Límac" replacing "Ychma" as the common name for the area.[3]

Modern scholars speculate that the word "Lima" originated as the Spanish pronunciation of the native name Limaq. Linguistic evidence seems to support this theory as spoken Spanish consistently rejects stop consonants in word-final position. The city was founded in 1535 under the name City of the Kings (Spanish: Ciudad de los Reyes) because its foundation was decided on January 6, date of the feast of the Epiphany. Nevertheless, this name quickly fell into disuse and Lima became the city's name of choice; on the oldest Spanish maps of Peru, both Lima and Ciudad de los Reyes can be seen together as names for the city.

The river that feeds Lima is called Rímac, and many people erroneously assume that this is because its original Inca name is "Talking River" (the Incas spoke a highland variety of Quechua where the word for "talker" was pronounced [ˈrimɑq]).[4] However, the original inhabitants of the valley were not the Incas, and this name is actually an innovation arising from an effort by the Cuzco nobility in colonial times to standardize the toponym so that it would conform to the phonology of Cuzco Quechua. Later, as the original inhabitants of the valley died out and the local Quechua became extinct, the Cuzco pronunciation prevailed. In modern times, Spanish-speaking locals do not see the connection between the name of their city and the name of the river that runs through it. They often assume that the valley is named after the river; however, Spanish documents from the colonial period show the opposite to be true.[3]

History

In the pre-Columbian era, the location of what is now the city of Lima was inhabited by several Amerindian groups under the Ychsma polity, which was incorporated into the Inca Empire in the 15th century.[5] In 1532, a group of Spanish conquistadors led by Francisco Pizarro defeated the Inca ruler Atahualpa and took over his Empire. As the Spanish Crown had named Pizarro governor of the lands he conquered,[6] he chose the Rímac valley to found his capital on January 18, 1535 as Ciudad de los Reyes (City of the Kings).[7] In August 1536, rebel Inca troops led by Manco Inca besieged the city but were defeated by the Spaniards and their native allies.[8]

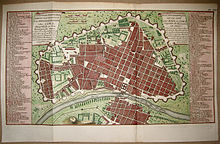

Lima gained prestige after being designated capital of the Viceroyalty of Peru and site of a Real Audiencia in 1543.[9] During the next century it flourished as the centre of an extensive trade network which integrated the Viceroyalty with the rest of the Americas, Europe and the Far East.[10] However, the city was not free from dangers; the presence of pirates and privateers in the Pacific Ocean lead to the building of the Walls of Lima between 1684 and 1687.[11] Also in this last year a powerful earthquake destroyed most of the city buildings;[12] the earthquake marked a turning point in the history of Lima as it coincided with a recession in trade and growing economic competition with other cities such as Buenos Aires.[13]

In 1746, a powerful earthquake severely damaged Lima and destroyed Callao, forcing a massive rebuilding effort under Viceroy José Antonio Manso de Velasco.[14] In the later half of the 18th century, Enlightenment ideas on public health and social control shaped the development of the city.[15] During this period, Lima was adversely affected by the Bourbon Reforms as it lost its monopoly on overseas trade and its control over the important mining region of Upper Peru.[16] The city's economic decline made its elite dependent on royal and ecclesiastical appointment and thus, reluctant to advocate independence.[17]

A combined expedition of Argentine and Chilean patriots under General José de San Martín landed south of Lima in 1820 but did not attack the city. Faced with a naval blockade and the action of guerrillas on land, Viceroy José de la Serna e Hinojosa evacuated its capital on July 1821 to save the Royalist army.[18] Fearing a popular uprising and lacking any means to impose order, the city council invited San Martín to enter Lima and signed a Declaration of Independence at his request.[19] However, the war was not over; in the next two years the city changed hands several times.

After independence, Lima became the capital of the Republic of Peru but economic stagnation and political turmoil brought urban development to a halt. This hiatus ended in the 1850s, when increased public and private revenues from guano exports led to a rapid development of the city.[20] The export-led expansion also widened the gap between rich and poor, fostering social unrest.[21] During the 1879–1883 War of the Pacific, Chilean troops occupied Lima, looting public museums, libraries and educational institutions.[22] At the same time, angry mobs attacked wealthy citizens and the Asian population; sacking their properties and businesses.[23] After the war, the city underwent a process of renewal and expansion from the 1890s up to the 1920s. During this period, the urban layout was modified by the construction of big avenues that crisscrossed the city and connected it with neighboring towns.[24]

On May 24, 1940,[25] an earthquake[26] destroyed most of the city, which at that time was mostly built of adobe and quincha. In the 1940s, Lima started a period of rapid growth spurred by migration from the Andean regions of Peru, as rural people sought opportunities for work and education. The population, estimated at 0.6 million in 1940, reached 1.9 million by 1960 and 4.8 million by 1980.[27] At the start of this period, the urban area was confined to a triangular area bounded by the city's historic centre, Callao and Chorrillos; in the following decades settlements spread to the north, beyond the Rímac River, to the east, along the Central Highway, and to the south.[28] The new migrants, at first confined to slums in downtown Lima, led this expansion through large-scale land invasions, which evolved into shanty towns, known as pueblos jóvenes.[29]

Geography

The urban area of Lima covers about 800 km2 (310 sq mi). It is located on mostly flat terrain in the Peruvian coastal plain, within the valleys of the Chillón, Rímac and Lurín rivers. The city slopes gently from the shores of the Pacific Ocean into valleys and mountain slopes located as high as 1,550 meters (5,090 ft) above sea level. Within the city there are isolated hills which are not connected to the surrounding hill chains, such as El Agustino, San Cosme, El Pino, La Milla, Muleria and Pro hills. The San Cristobal hill in the Rímac District, which lies directly north of the downtown area, is the local extreme of an Andean hill outgrowth.

Metro Lima covers 2,672.28 km2 (1,031.77 sq mi), of which 825.88 km2 (318.87 sq mi) (31%) comprise the actual city and 1,846.40 km2 (712.90 sq mi) (69%) the city outskirts. [citation needed] The urban area extends around 60 km (37 mi) from north to south and around 30 km (19 mi) from west to east. The city center is located 15 km (9.3 mi) inland at the shore of the Rímac River, a vital resource for the city, since it carries what will become drinking water for its inhabitants and fuels the hydroelectric dams that provide electricity to the area. While no official administrative definition for the city exists, it is usually considered to be composed of the central 30 of 43 districts of Lima Province, corresponding to an urban area centered around the historic Cercado de Lima district. [citation needed] The city is the core of the Lima Metro Area, one of the ten largest metro areas in the Americas. Lima is the world's second largest desert city, after Cairo, Egypt.

Climate

Lima's climate is in transition between mild and warm, despite being located in the tropics and in a desert, Lima's proximity to the cool waters of the Pacific Ocean leads to temperatures much cooler than those expected for a tropical desert, and can be classified as a mild desert climate (Köppen: BWn). It is neither cold nor very hot. Temperatures rarely fall below 14 °C (57 °F) or rise above 29 °C (84 °F) throughout the entire year.[30] Two distinct seasons can be identified: summer, from December through April; and winter from June through October. May and November are generally transition months, with the warm-to-cool weather transition being more dramatic.

Summers are warm, humid, and sunny. Daily temperatures oscillate between lows of 18 °C (64 °F) to 22 °C (72 °F), and highs of 24 °C (75 °F) to 29 °C (84 °F). Skies are generally cloud free, especially during daytime. Occasional coastal fogs on some mornings and high clouds in some afternoons and evenings can be present. Summer sunsets are well known for being colorful. As such, they have been labeled by the locals as “cielo de brujas” (Spanish for “sky of witches”), since the sky commonly turns shades of orange, pink and red around 7 pm. Winter weather is dramatically different. Gray skies, breezy conditions, high humidity and cool temperatures prevail. Long (1-week or more) stretches of dark overcast skies are not uncommon. Persistent morning drizzle occurs occasionally from June through September, coating the streets with a thin layer of water that generally dries up by early afternoon. Winter temperatures vary little between day and night. They range from lows of 14 °C (57 °F) to 16 °C (61 °F) and highs of 16 °C (61 °F) to 19 °C (66 °F), rarely exceeding 20 °C (68 °F) except in the easternmost districts.[31]

Relative humidity is always very high, particularly in the mornings.[32] High humidity produces brief morning fog in the early summer and a usually persistent low cloud deck during the winter (generally developing in May and persisting all the way into late November or even early December). Predominant onshore flow makes the Lima area one of the cloudiest among the entire Peruvian coast. Lima has only 1284 hours of sunshine a year, 28.6 hours in July and 179.1 hours in January, exceptionally little for the latitude.[33] Winter cloudiness prompts locals to seek for sunshine in Andean valleys located at elevations generally above 500 meters above sea level.

While relative humidity is high, rainfall is very low due to strong atmospheric stability. The severely low rainfall impacts on water supply in the city, which originates from wells and from rivers that flow from the Andes.[34] Inland districts receive anywhere between 1 to 6 cm (2.4 in) of rainfall per year, which accumulates mainly during the winter months. Coastal districts receive only 1 to 3 cm (1.2 in). As previously mentioned, winter precipitation occurs in the form of persistent morning drizzle events. These are locally called 'garúa', 'llovizna' or 'camanchacas'. Summer rain, on the other hand, is infrequent, and occurs in the form of isolated light and brief showers. These generally occur during afternoons and evenings when leftovers from Andean storms arrive from the east. The lack of heavy rainfall arises from high atmospheric stability caused, in turn, by the combination of cool waters from semi-permanent coastal upwelling and the presence of the cold Humboldt Current and warm air aloft associated with the South Pacific anticyclone.

Lima's climate (like that of most of coastal Peru) gets severely disrupted in El Niño events. Coastal waters usually average around 17–19 °C (63–66 °F), but get much warmer (like in 1998 when the water reached 26 °C (79 °F)). Air temperatures rise accordingly. Such was the case when Lima hit its all-time record high of 34 °C (93 °F).[31] Cooler climate develops during La Niña years. The all-time record low in the metro area is 8 °C (46 °F), measured in winter 1988.[31]

| Climate data for Lima | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 25.8 (78.4) |

26.5 (79.7) |

26.0 (78.8) |

24.3 (75.7) |

21.7 (71.1) |

19.7 (67.5) |

18.7 (65.7) |

18.4 (65.1) |

18.7 (65.7) |

19.9 (67.8) |

21.9 (71.4) |

23.9 (75.0) |

22.1 (71.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 19.1 (66.4) |

19.4 (66.9) |

19.2 (66.6) |

17.6 (63.7) |

16.1 (61.0) |

15.3 (59.5) |

15.0 (59.0) |

14.6 (58.3) |

14.6 (58.3) |

15.2 (59.4) |

16.4 (61.5) |

17.7 (63.9) |

16.7 (62.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 0.9 (0.04) |

0.3 (0.01) |

4.9 (0.19) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.00) |

0.3 (0.01) |

0.3 (0.01) |

0.3 (0.01) |

5.4 (0.21) |

0.2 (0.01) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.3 (0.01) |

13.0 (0.51) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 81.6 | 82.1 | 82.7 | 85.0 | 85.1 | 85.1 | 84.8 | 84.8 | 85.5 | 83.5 | 82.1 | 81.5 | 82.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 179.1 | 169.0 | 139.2 | 184.0 | 116.4 | 50.6 | 28.6 | 32.3 | 37.3 | 65.3 | 89.0 | 139.2 | 1,230 |

| Source 1: World Meteorological Organization (UN)[31] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: sunshine and humidity[33] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

With a municipal population of 8,852,000, and 9,752,000 for the metropolitan area and a population density of 3,008.8 inhabitants per square kilometre (7,793/sq mi) as of 2007,[35] Lima ranks as the 27th most populous 'agglomeration' in the world.[36] Its population features a complex mix of racial and ethnic groups. Mestizos of mixed Amerindian and European (mostly Spanish and Italians) ancestry are the largest ethnic group. European Peruvians are the second largest group. Many are of Spanish, Italian or German descent; many others are of French, British, or Croatian descent.[37][38] The minorities in Lima include Amerindians (mostly Aymara and Quechua) and Afro-Peruvians, whose African ancestors were initially brought to the region as slaves. There are also numerous Jews of European descent and Middle Easterners. Asians make up a large number of the metropolitan population, especially of Chinese (Cantonese) and Japanese descent, whose ancestors came mostly in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Lima has, by far, the largest ethnic Chinese community in Latin America.[39]

The first settlement in what would become Lima was made up of 117 housing blocks. In 1562, another district was built at the other side of the Rímac River and in 1610, the first stone bridge was built. Lima then had a population of around 26,000; blacks made up around 40% of the population, and whites made up around 38% of the population.[40] By 1748, the white population totaled 16,000–18,000.[41] In 1861, the number of inhabitants surpassed 100,000, and by 1927, this had doubled.[citation needed]

During the early twentieth century, thousands of immigrants came to the city, including people of German, French, Italian, and British descent. They organized social clubs and built their own schools. Examples are The American-Peruvian school, the Alianza Francesa de Lima, the Lycée Franco-Péruvien and the hospital Maison de Sante; Markham College, the British-Peruvian school in Monterrico, Antonio Raymondi District Italian School, the Pestalozzi Swiss School and also, several German-Peruvian schools.

Immigrants influenced Peruvian cuisine, with Italians in particular exerting a strong influence in the Miraflores and San Isidro areas with their restaurants, called trattorias.[citation needed]

A great number of Chinese immigrants, and a lesser number of Japanese, came to Lima and established themselves in the Barrios Altos neighborhood near downtown Lima. Lima residents refer to their Chinatown as Calle Capon, and the city's ubiquitous Chifa restaurants – small, sit-down, usually Chinese-run restaurants serving the Peruvian spin on Chinese cuisine – can be found by the dozens in this Chinese enclave.

In 2014, the National Institute for Statistics and Information (Instituto Nacional de Estadistica e Informatica) reported that the population of Lima in its 49 districts was 9,752,000 people, including the Constitutional Province of Callao. The city of Lima (metropolitan area) represents around 29% of the population of Peru. Of the total population for the city, around 48.7% are men and 51.3% are women. The 49 districts in Metropolitan Lima are often divided into 5 areas: Cono Norte (North Lima), Lima Este (East Lima), Constitutional Province of Callao, Lima Centro (Central Lima), and Lima Sur (South Lima). The largest areas are Lima Norte with 2,475,432 people and Lima Este with 2,619,814 people, including the largest single district San Juan de Lurigancho, which surpasses de 1 million people in population.[42]

In general, Lima is considered a “young” city. According to INEI, my mid 2014 the age distribution in Lima would be as follows: 24.3% between 0 and 14, 27.2% between 15 and 29, 22.5% between 30 and 44, 15.4% between 45 and 59, and 10.6% above 60.[42]

There is also a high level of immigration to Lima from the rest of the regions in the country. In 2013, 3 million 480 thousand people reported to being immigrants from other regions in the country. This represents almost 36% of the entire population of Metropolitan Lima. The three regions from where people immigrate the most to Lima are Junin, Ancash, and Ayacucho. On the contrary only 390 thousand emigrated from Lima to other regions of the country.[42]

The annual population growth rate for Lima is 1.57%. Of the 43 districts in the metropolitan area of Lima, some are considerably more populous than others. For example, 6 districts in Lima surpass the 400,000 people mark (San Juan de Lurigancho, San Martin de Porres, Ate, Comas, Villa el Salvador, and Villa Maria del Triunfo), while the ones with the least amount of people have populations of less than 60,000 people (San Luis, San Isidro, Magdalena del Mar, Lince, and Barranco).[42]

A household survey study published in 2005, shows a socio-economic distribution for households in Lima. The common distribution considers a monthly family income of 6000 Nuevos Soles or more for socioeconomic level A, 2000 to 6000 Nuevos Soles for level B, 840 to 2000 Nuevos Soles for level C, 420 to 1200 Nuevos Soles for level D, and up to 840 Nuevos Soles for level E. The distribution of socioeconomic level for households in Lima is: 18% level E, 32.3% level D, 31.7% level C, 14.6% level B, and 3.4% level A. In this sense, 82% of the population lives in households that earn up to 2000 Nuevos Soles monthly. Other salient differences between socioeconomic levels are levels of higher education, car ownership, size of the home, among other things.[43]

In Metropolitan Lima in 2013, the percentage of the population living in households in poverty is 12.8%. The level of poverty is measured by households that are unable to access a basic food basket and other household goods and services, such as clothing, housing, education, transportation, health, etc. The level of poverty has decreased from 2011 (15.6%) and 2012 (14.5%). The area in Lima with the highest proportion of poverty is Lima Sur (17.7%), followed by Lima Este (14.5%), and Lima Norte (14.1%), and Lima Centro (6.2%). In addition 0.2% of the population lives in extreme poverty, meaning that they are unable to access a basic food basket.[42]

Economy

Lima is the industrial and financial center of Peru, and one of the most important financial centers in Latin America,[44] home to many national companies. It accounts for more than two thirds of Peru's industrial production[45] and most of its tertiary sector.

The Metropolitan area, with around 7000 factories,[46] spearheads the industrial development of the country, thanks to the quantity and quality of the available workforce, cheap infrastructure and the well developed routes and highways in the city. Products include textiles, clothing and food. Chemicals, fish, leather and oil derivatives are also manufactured and/or processed in Lima.[46] The financial district is in San Isidro, while much of the industrial activity takes place in the area stretching west of downtown to the airport in Callao. Lima has the largest export industry in South America, and is a regional hub for the cargo industry.

Industrialization began to take hold in Lima in the 1930s and by 1950, through import substitution policies, manufacturing made up 14% of the GNP. In the late 1950s, up to 70% of consumer goods were manufactured in factories located in Lima.[47]

The Callao seaport is one of the main fishing and commerce ports in South America, covering over 47 hectares (120 acres) and shipping 20.7 million metric tons of cargo in 2007.[48] The main export goods leaving the country through Callao are oil, steel, silver, zinc, cotton, sugar and coffee.

As of 2003, Lima generates 53% of Peru's GDP.[49] Most foreign companies operating in Peru have settled in Lima.

In 2007, the Peruvian economy grew 9%, the largest growth rate in all of South America which was spearheaded by economic policies originating in Lima.[50] The Lima Stock Exchange grew 185.24% in 2006[51] and in 2007 grew 168.3%,[52] making it one of the fastest growing stock exchanges in the world. In 2006, the Lima Stock Exchange was the most profitable in the world.[53] The unemployment rate in the metropolitan area is 7.2%.

The Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Summit 2008 and the Latin America, the Caribbean and the European Union Summit were hosted by the city of Lima.

Lima is headquarters to major banks such as Banco de Crédito del Perú, Scotiabank Perú, Interbank, Bank of the Nation, Banco Continental, MiBanco, Banco Interamericano de Finanzas, Banco Finaciero, Banco de Comercio, and CrediScotia. It is a regional headquarters to Standard Chartered. Insurance corporations based in Lima include Rimac Seguros, Mapfre Peru, Interseguro, Pacifico, Protecta, and La Positiva.[54]

Government

National government

Lima is the capital city of the Republic of Peru and the province of Lima. As such, it is home to the three branches of the Government of Peru. The executive branch is headquartered in the Government Palace, located in the Plaza Mayor. The legislative branch is headquartered in the Legislative Palace and is home to the Congress of the Republic of Peru. The Judicial branch is headquartered in the Palace of Justice and is home to the Supreme Court of Peru. All the ministries are located in the city of Lima. In international government, the city of Lima is home to the headquarters of the Andean Community of Nations, along with other regional and international organizations.

The Palace of Justice in Lima is seat of the Supreme Court of Justice the highest judicial court in Peru with jurisdiction over the entire territory of Peru. Lima is seat of two of the 28 second highest or Superior Courts of Justice. The first and oldest Superior Court in Lima is the Superior Court of Justice of Lima belonging to the Judicial District of Lima. Due to the judicial organization of Peru, the highest concentration of courts is located in Lima despite the fact that its judicial district only has jurisdiction over 35 of the 43 districts of Lima.[55] The Superior Court of the Cono Norte is the second Superior Court located in Lima and is part of the Judicial District of North Lima. This judicial district has jurisdiction over the remaining eight districts all located in northern Lima.[56]

Local government

The city is roughly equivalent to the Province of Lima, which is subdivided into 43 districts. The Metropolitan Municipality of Lima is utmost authority of the entire city while each district has its own local government. Unlike the rest of the country, the Metropolitan Municipality, although a provincial municipality, acts as and has functions similar to a regional government, as it does not belong to any of the 25 regions of Peru. Each of the 43 districts in where the city extends have their own distrital municipality that is in charge on its own district, but they also have an obligation in coordinate with the metropolitan municipality. The actual mayor of the city is Mr. Luis Castañeda Lossio.

Political system

Unlike the rest of the country, the Metropolitan Municipality of Lima also has functions of regional government and is not part of any administrative region, according to Article 65. 27867 of the Law of Regional Governments on 16 November 2002.87 However the previous political organization remains in the sense that there is still a 'Governor' is the political authority throughout the scope of the department of Lima and the city itself. The functions of this authority are more police and military. The same city administration is for the local municipal authority.

Cityscape

Lima's architecture is characterized by a mix of styles. Examples of early colonial architecture include the Monastery of San Francisco, the Cathedral of Lima and the Torre Tagle Palace. These constructions are generally influenced by the Spanish Baroque,[57] Spanish Neoclassicism,[58] and Spanish Colonial styles.[59] After independence, there was a gradual shift toward the neoclassical and Art Nouveau styles. Many of these constructions were greatly influenced by French architectural styles.[60] Many government buildings as well as major cultural institutions were contracted in this period. During the 1960s, constructions using the brutalist style began appearing in Lima due to the military government of Juan Velasco Alvarado.[61] Examples of this architecture include the Museum of the Nation and the Ministry of Defense. The 21st century has seen the appearance of glass skyscrapers, particularly around the city's financial district.[62] There are new architectural and real estate projects.[63]

The largest parks of Lima are near the downtown area such as the Park of the Reserve, Park of the Exposition,[64] Campo de Marte, and the University Park. The Park of the Reserve is home to the largest fountain complex in the world known as the Magical Circuit of Water.[65] A number of large parks lie outside the city center, including Reducto Park, Pantanos de Villa Wildlife Refuge, El Golf (San Isidro), Parque de las Leyendas (Lima Zoo), El Malecon de Miraflores, and the Golf Los Incas.[66]

The street grid of the city of Lima is laid out with a system of plazas that are similar to roundabouts or junctions. In addition to this practical purpose, plazas serve as one of Lima's principal green spaces and contain monuments, statues and water fountains.[67]

Society and culture

Strongly influenced by European, Andean, African and Asian culture, Lima is a melting pot of cultures due to colonization, immigration, and indigenous influences.[68] The Historic Centre of Lima was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1988.

The city is known as the Gastronomical Capital of the Americas. Lima's gastronomy is a mix of Spanish, Andean, and Asian culinary traditions.[69]

Lima's beaches, located along the northern and southern ends of the city, are heavily visited during the summer months. Restaurants, clubs and hotels have opened in these places to serve the beachgoers. Lima has a vibrant and active theater scene, including classic theater, cultural presentations, modern theater, experimental theater, dramas, dance performances, and theater for children. Lima is home to the Municipal Theater, Segura Theater, Japanese-Peruvian Theater, Marsano Theater, British theater, Theater of the PUCP Cultural Center, and the Yuyachkani Theater.[70]

Language

Known as Peruvian Coast Spanish, Lima's Spanish is characterized by the lack of strong intonations as found in many other regions of the Spanish-speaking world. It is heavily influenced by the historical Spanish spoken in Castile. Throughout the colonial era, most of the Spanish colonial nobility based in Lima were originally from Castile.[71] Limean Castillian is also characterized by the lack of voseo, a trait present in the dialects of many other Latin American countries. This is because voseo was primarily used by the lower socioeconomic classes of Spain, a social group that did not begin to appear in Lima until the late colonial era.[citation needed]

Limean Spanish is distinguished by its clarity in comparison to other Latin American accents, and has been influenced by immigrant groups including Italians, Andalusians, Chinese and Japanese. It also has been influenced by anglicisms as a result of globalization, as well as by Andean Spanish, due to the migration from the Andean highlands to Lima.[72]

Museums

Lima is home to the highest concentration of museums of the country, the most notable of which are the Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Antropología e Historia del Perú, Museum of Art of Lima, the Museo Pedro de Osma, the Museum of Natural History, the Museum of the Nation, The Sala Museo Oro del Perú Larcomar, the Museum of Italian Art, and the Museum of Gold, and the Larco Museum. These museums focus on art, pre-Columbian cultures, natural history, science and religion.[73] The Museum of Italian Art shows European art.

Tourism

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Criteria | Cultural: iv |

| Reference | 500 |

| Inscription | 1988 (12th Session) |

| Extensions | 1991 |

As the major point of entry to the country, Lima has developed a tourism industry, characterized by its historic center, archeological sites, nightlife, museums, art galleries, festivals, and traditions. Lima is home to restaurants and bars where local and international cuisine is served.[74]

The Historic Centre of Lima, made up of the districts of Lima and Rímac, was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1988.[75] Some examples of colonial architecture include the Monastery of San Francisco, the Plaza Mayor, the Cathedral, Convent of Santo Domingo, the Palace of Torre Tagle, and much more.

A tour of the city's churches is a popular circuit among tourists. A trip through the central district goes through churches dating from as early as the 16th and 17th centuries, the most noteworthy of which are the Cathedral of Lima and the Monastery of San Francisco, said to be connected by their subterrestrial catacombs.[76] Both of these churches contain paintings, Sevilian tile, and sculpted wood furnishings.

Also notable is the Sanctuary of Las Nazarenas, the point of origin for the Lord of Miracles, whose festivities in the month of October constitute the most important religious event in Lima, and a major one of Peru. Some sections of the Walls of Lima still remain and are frequented by tourists. These examples of medieval Spanish fortifications were built to defend the city from attacks by pirates and privateers.[77]

Beaches are visited during the summer months, located along the Pan-American Highway, to the south of the city in districts such as Lurín, Punta Hermosa, Santa María del Mar (Peru), San Bartolo and Asia. Restaurants, nightclubs, lounges, bars, clubs, and hotels have developed to cater to beachgoers.[78]

The suburban districts of Cieneguilla, Pachacamac, and the city of Chosica, are tourist attractions among locals. Because they are located at a higher elevation than Lima, they receive more sunshine in winter months, something that the city of Lima frequently lacks under seasonal fog.[79]

Food

Lima is known as the Gastronomical Capital of the Americas. A center of immigration and the center of the Spanish Viceroyalty, Lima has incorporated dishes brought from the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors and waves of immigrants: African, European, Chinese, and Japanese.[69] Besides international immigration there has been, since the second half of the 20th century, a strong internal flow from rural areas to cities, in particular to Lima.[80] This has influenced Lima's cuisine with the incorporation of the immigrant's ingredients and techniques (for example, the Chinese extensive use of rice or the Japanese approach to preparing raw fish). The genres of restaurants in Lima include Creole food, Chifas, Cebicherias, and Pollerias.[81]

Lima concentrates a large part of the population native from other regions in the country. In recent history, Lima has positioned itself among a culinary destination for travelers around the world. In many respects, Lima is considered the gastronomical capital of Latin America because its inherited traditions from pre-Hispanic and colonial cultures blended with Western and oriental cooking. In the last few years, not only have restaurants been recognized internationally, Peruvian coffee and chocolate have also won international awards around the world.[82]

In 2014, two restaurants from Lima were awarded within The World’s 50 Best Restaurants: Central was awarded #15 (chefs Virgilio Martinez and Pia Leon) and Astrid & Gaston awarded #18 (chef Diego Muñoz and owned by famous chef Gaston Acurio). This award is one of the most prestigious in the world of culinary arts. A panel of 900 experts defines the winners.[83] In addition, Central was named #1 restaurant in the list of Latin America’s 50 Best Restaurants 2014. Out of the 50 best restaurants in Latin America, Lima is the second city with most awards (after Buenos Aires): Central #1, Astrid & Gaston #2, Maido #7, Malabar #11, La Mar #15, Fiesta #20, Rafael #27, and La Picanteria #31. All of these restaurants represent cooking with fusion from different regions of the country and even the world.[84]

In 2007, the Peruvian Society for Gastronomy was born with the objective of uniting the key actors in Peruvian gastronomy to put together activities that would promote Peruvian food and reinforce the Peruvian national identity. The society, called APEGA, congregated chefs, nutritionists, institutes for gastronomical training, restaurant owners, chefs and cooks, researchers, and journalists. They also worked with universities, food producers, artisanal fishermen and sellers in food markets.[85] One of their first projects was to put together the largest food festival in Latin America to take place in Lima, called Mistura (“mixture” in Portuguese). The fair takes place in September every year since 2008 and the number of attendees has grown from 30,000 the first year to 600,000 in 2014. The entrance ticket cost is about $8.75 and small plates of food inside the fair cost about $5–6.[86] The fair congregates restaurants, food producers, bakers, chefs, street vendors, and cooking institutes from all over the country for ten days to celebrate the country’s excellent food and the variety of ingredients Peru is lucky to produce.[87]

Sports

The city of Lima has sports venues for football, volleyball and basketball, many of which are located within private clubs. A popular sport among Limenos is fronton, a racquet sport similar to squash invented in Lima. The city is home to seven international-class golf links. Equestrian is popular in Lima with private clubs as well as the Hipódromo de Monterrico horse racing track. The most popular sport in Lima is football with professional club teams being located in the city.

The historic Plaza de toros de Acho, located in the Rímac District, a few minutes from the Plaza de Armas, holds bullfights yearly. The season runs from late October to December.

Lima will host the 2019 Pan American Games.[88]

| Club | Sport | League | Venue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peruvian Institute of Sport | Various | Various | Estadio Nacional (Lima) |

| Club Universitario de Deportes | Football | Peruvian Primera División | Estadio Monumental "U" |

| Alianza Lima | Football | Peruvian Primera División | Estadio Alejandro Villanueva |

| Sporting Cristal | Football | Peruvian Primera División | Estadio Alberto Gallardo |

| CD Universidad San Martín | Football | Peruvian Primera División | Estadio Alberto Gallardo |

| Regatas Lima | Various | Various | Regatas Headquarters Chorrillos |

| Real Club Lima | Basketball, Volleyball | Various | San Isidro |

Subdivisions

1. Central Lima

2. Traditional area

3. Cono Norte

4. Cono Sur

5. Cono Este

6. Beach areas

7. Callao

Lima is made up of thirty densely populated districts, each headed by a local mayor and the Mayor of Lima, whose authority extends to these and the thirteen outer districts of the Lima province.

The city's historic centre is located in the Cercado de Lima district, locally known as simply Lima, or as "El Centro" ("Downtown"), and it is home to most of the vestiges of Lima's colonial past, the Presidential Palace (Spanish: Palacio de Gobierno), the Metropolitan Municipality of Lima (Spanish: Consejo municipal metropolitano de Lima), Chinatown, and dozens of hotels, some operating and some defunct, that used to cater to the national and international elite.

The upscale San Isidro District is the city's financial center. It is home to politicians and celebrities and where the main banks of Peru and branch offices of world banks are headquartered. San Isidro has parks, including Parque El Olivar, with has olive trees that were brought from Spain during the seventeenth century. The Lima Golf Club, a prominent golf club, is also located within the district.

Another upscale district is Miraflores, which has luxury hotels, shops and restaurants. Miraflores has more parks and green areas in the south of Lima than most other districts. Larcomar, a popular shopping mall and entertainment center built on cliffs overlooking the Pacific Ocean, featuring bars, dance clubs, movie theaters, cafes, shops, boutiques and galleries, is also located in this district. Nightlife, shopping and entertainment also center around Parque Kennedy, a park in the heart of Miraflores that is always bustling with people and live performances.[90]

La Molina, San Borja and Santiago de Surco, home to the American Embassy and the exclusive Club Polo Lima, are the other three wealthy districts of Lima.

The most densely populated districts of Lima lie in the northern and southern ends of the city (Spanish: Cono Norte and Cono Sur, respectively), and they are mostly composed of Andean immigrants who arrived during the mid and late twentieth century looking for better living standards and economic opportunities, or as refugees of the country's internal conflict with the Shining Path during the late 1980s and early 1990s. In the case of Cono Norte (now called Lima Norte), shopping malls like Megaplaza and Royal Plaza have been built in the Independencia district, on the border with the Los Olivos district, the latter being the most residential neighborhood in the northern part of Lima. Most of the inhabitants of this area belong to the middle class or lower middle class.

Barranco, which borders Miraflores by the Pacific Ocean, is known as the city's bohemian district, home or once home of Peruvian writers and intellectuals like Mario Vargas Llosa, Chabuca Granda and Alfredo Bryce Echenique. This district has acclaimed restaurants, music venues called "peñas" featuring the traditional folk music of coastal Peru (in Spanish, "música criolla"), and beautiful Victorian-style chalets. It along with Miraflores serves as the home to the foreign nightlife scene.

Education

Lima is home to the oldest higher learning institution in the New World, San Marcos University founded in 1551. Home to universities, institutions, and schools, Lima has the highest concentration of institutions of higher learning in the continent. The National University of San Marcos, founded on May 12, 1551 during Spanish colonial regime, is the oldest continuously functioning university in the Americas.[91]

Universidad Nacional de Ingeniería (UNI) was founded in 1876 by Polish engineer Eduardo de Habich and is the most important engineering school in the country. Other public universities also play roles in teaching and research, such as the Universidad Nacional Federico Villarreal (the second largest in the country), the Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina where ex-president Alberto Fujimori once taught, and the National University of Callao.

The Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, established in 1917, is the oldest private university. Other private institutions that are located in the city are Universidad del Pacifico, Universidad ESAN, Universidad de Lima, Universidad de San Martín de Porres, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Universidad Cientifica del Sur, Universidad San Ignacio de Loyola, Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas, Universidad Privada San Juan Bautista and Universidad Ricardo Palma.[92]

The city of Lima has a total of 8,047 schools of elementary and high school, both public and private, which provide educational services to more than a million and a half students. There are more private schools than public (6,242 private and 1,805 public schools) and the average size of the private schools is 100 for elementary and 130 for high school. In contrast, public schools average 400 students in elementary and 500 in high school.[93]

Lima is one of the cities in Peru with the highest level of educational coverage or enrollment in high school and early childhood schooling. These values represent the amount of children and youth enrolled in school compared to the total amount of school-aged children. The enrollment level in high school in Lima is 86.1%, while the national average is 80.7%. In early childhood, the enrollment level in Lima is 84.7%, while the national average is 74.5%. The enrollment in early childhood has improved in 12.1% since 2005. In elementary school, the enrollment in Lima is 90.7%, while the national average for this level is 92.9%.[94]

Besides enrollment, the dropout rate is represents the amount of students that do not complete the school level appropriate to their age. In general, the dropout rate for Lima is lower than the national average, except for elementary school, which is higher. In Lima, the dropout rate in elementary is 1.3% and 5.7% in high school, while the national average is 1.2% in elementary and 8.3% in high school.[94]

In Peru, every year students in all schools (public and private) in second and fourth grade take a test called “Evaluacion Censal de Estudiantes” (ECE). The test assesses skills in reading comprehension and math. The test results are presented in three levels: Below level 1 means that students were not able to respond even the most simple questions on the test, level 1 means the students did not achieve the expected level in skills but that they could respond the simple questions in the exam, and level 2 means they achieved the expected skill for their grade level. In 2012, in reading comprehension 48.7% of students in Lima achieved level 2, compared to 45.3% in 2011. In math, only 19.3% students were able to achieve level 2, 46.4% achieved level 1, and 34.2% achieved less than level 1. Even though the results for Math are even lower than for reading comprehension, in both subject areas students performed better in 2012 than in 2011. Compared to the rest of the country, the city of Lima performs much better than the national average in both reading comprehension and math.[95]

The educational system in Lima is organized under the authority of the “Direccion Regional de Educacion (DRE) de Lima Metropolitana”, which is in turn divided into 7 sub-directions or “UGEL” (Unidad de Gestion Educativa Local): UGEL 01 (San Juan de Miraflores, Villa Maria del Triunfo, Villa El Salvador, Lurin, Pachacamac, San Bartolo, Punta Negra, Punta Hermosa, Pucusana, Santa Maria, and Chilca), UGEL 02 (Rimac, Los Olivos, Independencia, Rimac, and San Martin de Porres), UGEL 03 (Cercado, Lince, Breña, Pueblo Libre, San Miguel, Magdalena, Jesus Maria, La Victoria, and San Isidro), UGEL 04 (Comas, Carabayllo, Puente Piedra, Santa Rosa, and Ancon), UGEL 05 (San Juan de Lurigancho and El Agustino), UGEL 06 (Santa Anita, Lurigancho-Chosica, Vitarte, La Molina, Cieneguilla, and Chaclacayo), and UGEL 07 (San Borja, San Luis, Surco, Surquillo, Miraflores, Barranco, and Chorrillos).[94]

The UGELes with highest results on the ECE 2012 are UGEL 07 and 03 in both reading comprehension and math. UGEL 07 had 60.8% students achieving level 2 in reading comprehension and 28.6% students achieving level 2 in Math. UGEL 03 had 58.5% students achieve level 2 in reading comprehension and 24.9% students achieving level 2 in math. The lowest achieving UGELs are UGEL 01, 04 and 05.[95]

With regards to higher education, 23% of men have completed university education in Lima, while 20% of women have done so. Additionally, 16.2% of men have completed non-university higher education, and 17% of women have done so. The average years of schooling in the city is 11.1 years (11.4 for men and 10.9 for women).[42]

Transport

Air

Lima is served by the Jorge Chávez International Airport, located in Callao (LIM). It is the largest airport of the country with the largest amount of domestic and international air traffic. It also serves as a major hub in the Latin American air network. Lima's Jorge Chávez International Airport is the fourth largest air hub in South America. Additionally, Lima possesses five other airports: the Las Palmas Air Force Base, Collique Airport, and runways in Santa María del Mar, San Bartolo and Chilca.[96]

Land

Lima is a major stop on the Pan-American Highway. Because of its location on the country's central coast, Lima is also an important junction in Peru's highway system. Three of the major highways originate in Lima.

- The Northern Panamerican Highway, this highway extends more than 1,330 kilometers (830 mi) to the border with Ecuador connecting the northern districts of Lima with many major cities along the northern Peruvian coast.

- The Central Highway (Spanish: Carretera Central), this highway connects the eastern districts of Lima with many cities in central Peru. The highway extends 860 kilometers (530 mi) with its terminus at the city of Pucallpa near Brazil.

- The Southern Panamerican Highway, this highway connects the southern districts of Lima to cities on the southern coast. The highway extends 1,450 kilometers (900 mi) to the border with Chile.

The city of Lima has one big bus terminus station located next to the mall Plaza norte in the north of the city. This bus station is the point of departure and arrival of a lot of buses with national and international destinations. There are other bus stations for each company around the city. In addition, there are informals bus stations located in the south, center and north of the city; these bus stations are cheap and confusing, but manageable if you know your destination and have a basic comprehension of Spanish.

Maritime

The proximity of Lima to the port of Callao allows Callao to act as the metropolitan area's foremost port. Callao concentrates nearly all of the maritime transport of the metropolitan area. There is, however, a small port in Lurín whose transit mostly is accounted for by oil tankers due to a refinery being located nearby. Nonetheless, maritime transport inside Lima's city limits is relatively insignificant compared to that of Callao, the nation's leading port and one of Latin America's largest.

Rail

Lima is connected to the Central Andean region by the Ferrocarril Central Andino which runs from Lima through the departments of Junín, Huancavelica, Pasco, and Huánuco.[97] Major cities along this line include Huancayo, La Oroya, Huancavelica, and Cerro de Pasco. Another inactive line runs from Lima northwards to the city of Huacho.[98]

Public

Eighty percent of the city's history having occurred during the pre-automobile era, Lima's road network is based mostly on large divided avenues rather than freeways. Lima has developed a freeway network of nine freeways - the Via Expresa Paseo de la Republica, Via Expresa Javier Prado, Via Expresa Grau, Panamericana Norte, Panamericana Sur, Carretera Central, Via Expresa Callao, Autopista Chillon Trapiche, and the Autopista Ramiro Priale.[99][99]

According to a survey done in 2012, the majority of the population in Lima uses public or collective transportation (75.6%), while 12.3% uses an individual transport mechanism (such as own car, taxi or motorcycle).[94]

The urban transport system is composed of over 652 transit routes[53] which are served by buses, microbuses, and combis. The system is unorganized and is characterized by the lack of formality. The service is run by 464 private companies which are poorly regulated by the local government. Fares average one sol or US$0.40.

Taxis in the city are mostly informal; they are cheap but can be dangerous because of the way the "taxistas" drive. There are no meters, so drivers are told the desired destination and the fare is agreed upon before the passenger enters the taxi. Taxis vary in sizes from small four-door compacts to large vans. They are everywhere, accounting for a large part of the car stock. In many cases they are just a private car with a taxi sticker on the windshield. Additionally, there are several companies that provide taxi service on-call.[100]

Colectivos render express service on some major roads of the Lima Metropolitan Area. The colectivos signal their specific destination with a sign on the their windshield. Their routes are not generally publicitized but are understood by frequent users. The cost is generally higher than public transport; however, they cover greater distances at greater speeds due to the lack of stops. This service is informal and is illegal in the city.[101] Some people in the periphery of the city use the so-called "mototaxi" for short distances.

The Metropolitan Transportation System or El Metropolitano is new integrated system for public transportation in Lima consisting in a network of buses that run in exclusive corridors under the Bus Rapid Transit system (BST). The goal of this system of buses is to improve the quality of life of citizens by saving them time in their daily commutes, protecting the environment, providing improved security and quality of service. The Metropolitano was executed with funds from the City of Lima (Municipalidad de Lima) and financing from the Inter-American Development Bank and the World Bank. In contrast to other transit systems in Bogota, Curitiba or Mexico City, the Metropolitana is the first BRT system to operate fueled with natural gas, seeking to contribute to reduce the contamination caused by transit in the city of Lima.[102] This system links the principal points of the Lima Metropolitan Area. The first phase of this project has 33 kilometres (21 mi) of line from the north of the city to Chorrillos in the south of the city. It began commercial operations on July 28, 2010. Since 2014, Lima Council operates the "Sistema Integrado de Transporte Urbano" (Urban integrated transport system), which comprises brand-new buses all over Avenida Arequipa.[103] By the end of 2012, the Metropolitano system counted with 244 buses in its central routes and 179 buses in its feeding routes. That is, a total float of 423 buses in operation. In one weekday 437,148 people use the system. The amount of users has increased from 2011 in 28.2% for weekdays, 29.1% for Saturdays, and 33.3% for Sundays.[94]

The Lima Metro has twenty six passenger stations, located at an average distance of 1.2 km (0.7 miles). It starts its path in the Industrial Park of Villa El Salvador, south of the city, continuing on to Av. Pachacútec in Villa María del Triunfo and then to Av. Los Héroes in San Juan de Miraflores. Afterwards, it continues through Av. Tomás Marsano in Surco to reach Ov. Los Cabitos, to Av. Aviación and then cross the river Rimac to finish, after almost 35 km (22 mi) , in the east of the capital in San Juan de Lurigancho The system counts with five trains, each with six wagons. Each wagon has the capacity to transport 233 people. The metro system began operating in December 2012 and transported 78,224 people on average on a daily basis.[94]

Other Transportation Issues

In addition, the city of Lima has high car and bus congestion or traffic on a daily basis, especially on peak hours. The amount of vehicles in the region of Lima by the end of 2012 was of 1 million 397 thousand (109,122 more than in 2011). This may be caused by the large amount of cars in the city: The region of Lima counts with 65.3% of the total amount of cars in the country.[94]

The Ministry of Economy and Finance (MEF) implemented a program with economic incentives for municipalities to implement bicycle routes in their districts. The “recreational bike lanes” can be found in 39 districts in Lima. The Proyecto Especial Metropolitano de Transporte No Motorizado (PEMTNM) estimates that more than a million and a half of people in Lima used the recreational bike lanes in 2012. The bike lanes added 71 km (44 mi) to the city for this particular use. They also estimate that the use of the bike lanes has prevented the emission of 526 tons of carbon dioxide in 2012.[94]

One district in Lima, San Borja, is the first one to implement a bike-share program in Lima called San Borja en Bici. It counts with 200 bicycles and six stations across the district (two of them connecting with the Metro of Lima). By December 2012, the program had 2,776 people subscribed to the service.[104]

Urban Challenges

Environment

Air

Environmentally, the city of Lima suffers mostly from air pollution. The sedimentary dust has contaminant solid particles that are deposited as dust in different surfaces or float through the air. The dust with fine particles is the most dangerous given that they are able to penetrate the respiratory system. The recommended concentration of these particles by the World Health Organization is 5 tons/km2/month, although in February 2014, Lima recorded an average of 15.2 tons/km2. Two districts in Lima with the highest concentration of sedimentary dust are El Agustino (46.1 tons/km2) and Independencia (25.5 tons/km2) in February 2014.[94][105]

Water

The quality of water is also another environmental indicator. The permissible limit of lead in the water supply is 0.05 milligrams per liter, according to the Norm ITINTEC. In January 2014, the concentration of minerals in water treatment facilities of SEDAPAL was 0.051 Iron, 0.0050 Lead, 0.0012 Cadmium, and 0.0810 Aluminum. These values show an increase of 15.9% and 33.3% in Iron and Cadmium with respect to January 2013 and a decrease of 16.7% and 12.4% in Lead and Aluminum. The values are within the healthy limits.[105]

Solid Waste

The amount of solid waste produced per capita in the city of Lima is about 0.7 kg (2 lb) per day. In 2012, each citizen in the city produced 273.36 kg (603 lb) of solid waste. The district municipalities only collect about 67% of the solid waste they generate. The rest may reach informal landfills, rivers, or to the ocean. Further, only 3 municipalities in the city recycle 20% of their waste.[42]

Access to Basic Services

In the city of Lima, 93% of households have access to water supply in their homes. In addition, 92% of homes count with sewage systems. With regards to electricity, 99.6% of homes count with this service. Although most of the households count with water and sewage systems, some count with the services for a few hours a day only.[94]

Security

The perception of security varies much in the city of Lima depending on the district. For example, San Isidro is the district with the lowest perception of insecurity (21.4%), while Rimac is the district with the highest perception of insecurity with 85%, according to a survey of victimization in 2012 elaborated by the NGO Ciudad Nuestra. The five districts with the lowest perception of insecurity are San Isidro, San Borja, Miraflores, La Molina, and Jesus Maria. The districts with the highest perception of insecurity are Rimac, San Juan de Miraflores, La Victoria, Comas and Ate.[106]

Overall, 40% of the population in Lima above 15 years old has been victim of a crime. The younger population (ages 15 to 29 years old) is the age group with the highest victimization rate (47.9%).[42] In addition, in 2012, citizens mostly reported to being victims of theft (47.9%), theft in homes or establishments (19.4%), robbery or attack (14.9%), gang aggression (5.7%), among others in lesser frequency. The districts with the highest level of victimization are Rimac, El Agustino, Villa El Salvador, San Juan de Lurigancho and Los Olivos. On the other hand, the “safest” districts by level of victimization are Lurin, Lurigancho-Chosica, San Borja, Magdalena, and Surquillo. Interestingly, these districts don’t necessarily correspond to the districts with highest or lowest perception of insecurity in the city.[106]

While the Police is nationally controlled and funded, each district in Lima has a community policing structure called Serenazgo. The quantity of officials and resources that go to the local Serenazgos vary by district. The ratio of citizens per Serenazgo official in each district varies greatly. For example, in Villa Maria del Triunfo there are 5,785 citizens per official. Twenty-two districts in Lima have a ratio above 1000 citizens per Serenazgo official. On the other hand, 14 districts have ratios below 200 citizens per official, including Miraflores with 119 and San Isidro with 57.[42]

The satisfaction with the Serenazgos also varies greatly by district. The highest satisfaction rates can be found in San Isidro (88.3%), Miraflores (81.6%), San Borja (77%), and Surco (75%). The lowest satisfaction rates can be found in Villa Maria del Triunfo (11%), San Juan de Miraflores (14.8%), Rimac (16.3%), and La Victoria (20%).[106]

International relations

- Twin towns — Sister cities

|

See also

- Largest cities in the Americas

- List of districts of Lima

- List of metropolitan areas of Peru

- List of people from Lima

- List of sites of interest in the Lima Metropolitan area

References

Notes

- ^ "Peru Altitude". Retrieved 2014-07-28.

- ^ "INEI: Lima cuenta con 9 millones 752 mil habitantes". larepublica.pe.

- ^ a b "Limaq" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-10-10.

- ^ http://www.funtrivia.com/en/subtopics/Perú-The-Incas-Country-226473.html

- ^ Conlee et al., "Late Prehispanic sociopolitical complexity", p. 218.

- ^ Hemming, The conquest, p. 28.

- ^ Klarén, Peru, p. 39.

- ^ Hemming, The conquest, p. 203–206.

- ^ Klarén, Peru, p. 87.

- ^ Andrien, Crisis and decline, pp. 11–13.

- ^ Higgings, Lima, p. 45.

- ^ Andrien, Crisis and decline, p. 26.

- ^ Andrien, Crisis and decline, p. 28.

- ^ Walker, "The upper classes", pp. 53–55.

- ^ Ramón, "The script", pp. 173–174.

- ^ Anna, Fall of the royal government, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Anna, Fall of the royal government, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Anna, Fall of the royal government, pp. 176–177.

- ^ Anna, Fall of the royal government, pp. 178–180.

- ^ Klarén, Peru, p. 169.

- ^ Klarén, Peru, p. 170.

- ^ Higgings, Lima, p. 107.

- ^ Klarén, Peru, p. 192.

- ^ Ramón, "The script", pp. 180–182.

- ^ "20th Century Earthquakes: Records about Historical Earthquakes in Peru". Lima Easy: The Lima Guide. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ^ "300 Die in Lima Earthquake". The Advertiser (Adelaide, Australia). Trove: Digitized newspapers and more. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ^ Template:Es icon Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática, Lima Metropolitana perfil socio-demográfico. Retrieved on August 12, 2007

- ^ Dietz, Poverty and problem-solving, p. 35.

- ^ Dietz, Poverty and problem-solving, p. 36.

- ^ "Average Weather For Callao/Lima, Peru". WeatherSpark. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- ^ a b c d "World Weather Information Service – Lima". World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- ^ "BBC Weather – Lima". BBC. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- ^ a b Capel Molina, José J. (1999). "Lima, un clima de desierto litoral" (PDF). Anales de Geografía de la Universidad Complutense (in Spanish). 19. Madrid: Universidad Complutense de Madrid: 25–45. ISSN 0211-9803. Retrieved September 17, 2013.

- ^ Painter, James (2007-03-12). "Americas | Peru's alarming water truth". BBC News. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ^ Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática, Perfil Sociodemográfico del Perú pp. 29–30, 32, 34.

- ^ United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Urban Agglomerations 2007. – note, per the source, "Urban agglomerations included in the chart are those of 1 million inhabitants or more in 2007. An agglomeration contains the population within the contours of contiguous territory inhabited at urban levels of residential density without regard to administrative boundaries."

- ^ Baily, Samuel L; Míguez, Eduardo José (2003). Latin America Since 1930. Google Books. ISBN 978-0-8420-2831-8. Retrieved 2010-04-17.

- ^ "The Institute of International Education (IIE)". IIEPassport.org. Archived from the original on June 9, 2008. Retrieved 2010-04-17.

- ^ ":: Overseas Compatriot Affairs Commission, R.O.C. ::". Ocac.gov.tw. 2004-08-24. Retrieved 2009-10-10.

- ^ History of Lima. Lima Info.

- ^ Colonial Lima according to Jorge Juan and Antonio de Ulloa. From Jorge Juan and Antonio de Ulloa, A Voyage to South America (1748).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i http://www.inei.gob.pe/media/MenuRecursivo/publicaciones_digitales/Est/Lib1168/libro.pdf

- ^ http://www.apeim.com.pe/wp-content/themes/apeim/docs/nse/APEIM-NSE-2003-2004-LIMA.pdf

- ^ Infoplease. Lima. Retrieved on December 8, 2008.

- ^ AttractionGuide. Lima Attractions. Retrieved on December 8, 2008.

- ^ a b "Study Abroad Peru". Study Abroad Domain. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ^ Bethell, Leslie (1991). Latin America Since 1930. Google Books. ISBN 978-0-521-26652-9. Retrieved 2010-04-17.

- ^ "Port Commerce". Port of Callao. World Port Source. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ pág. 24

- ^ https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2003rank.html CIA Factbook

- ^ "Bolsa de Valores de Lima" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 8, 2007. Retrieved 2010-04-17.

- ^ "Bolsa de Valores de Lima". Bolsa de Valores de Lima. Archived from the original on July 14, 2008. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ^ a b "Republic Of Peru" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ^ "Compañías de Seguros Peru". Oh Perú. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ^ Template:Es icon Judicial Power of Peru. Superior Court of Lima. Retrieved 3 December 2008.

- ^ Template:Es icon Judicial Power of Peru. Superior Court of North Lima. Retrieved 3 December 2008.

- ^ "Baroque Architecture". Buzzle.com. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ Story by Cristyane Marusiak / Photos by João Canziani. "Lima, Peru - Travel - dwell.com". Web.archive.org. Archived from the original on 2008-04-07. Retrieved 2009-10-10.

- ^ "ACAP – The American and Canadian Association of Peru". Acap-peru.org. 2005-12-01. Retrieved 2009-07-08. [dead link]

- ^ Bethell, Leslie (1998). A Cultural History of Latin America and Spain. Books.google.com. ISBN 978-0-521-62626-2. Retrieved 2010-04-17.

- ^ feedback. "Lima city guide – the social travel guide Lima, Peru – tripwolf travel tips". Tripwolf.com. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ^ "Haydee Sangalli Schaerer:: Bienes Raices". Mira Mar Peru. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ^ "Periodo 1821–1872 – El Palacio y Parque de la Exposición". Arqandina.com. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ^ "LaRepublica.pe | Jornada de Protestas / Último adiós a Michael Jackson / Rómulo León". Larepublica.com.pe. Retrieved 2009-07-08.[dead link]

- ^ "Lima, Peru – Google Maps". Maps.google.com. 1970-01-01. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ^ "Lima (Peru) :: The city layout – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ^ Marmon, Johanna (1 December 2003). "Colonial masterpiece: many who visit Peru come for the journey to ancient Macchu Picchu. But the former colonial--and current day--capital city of Lima is an architectural and gastronomic wonderland". South Florida CEO. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ a b Web Design by Avtec Media. "Peruvian Cuisine ~ New Andean ~ Novoandina – Mixtura Restaurant:: The New Andean Cuisine:: Kirkland, Washington: Latin Spanish Peruvian Restaurants". Mixtura.biz. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ^ "Theatres in Lima, Peru – LimaEasy (c)". LimaEasy. 2009-06-27. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ^ "Articles: Colonial Lima according to Jorge Juan and Antonio de Ulloa". Historical Text Archive. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ^ Kokotovic, Misha (2007). The Colonial Divide in Peruvian Narrative. Books.google.com. ISBN 978-1-84519-184-9. Retrieved 2010-04-17.

- ^ "Information about Peru". Go2peru.com. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ^ "Lima Peru". Go2peru.com. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ^ "World Heritage Centre – World Heritage List". Whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ^ "LIMA – Churches in the Historical Centre of Lima Perú". Enjoyperu.com. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ^ "Lima – Peru". VirtualPeru.Net. Retrieved 2009-07-08. [dead link]

- ^ "in". In-lan.com. Retrieved 2009-07-08. [dead link]

- ^ "HowStuffWorks "Geography of Lima"". HowStuffWorks. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ^ "Peru's revolution in tastes: innovative chefs in Lima are dishing up a fusion of Andean and European cuisines with seasoning from around the world. (01-MAY-06) Americas (English Edition)". Accessmylibrary.com. 2006-05-01. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ^ "Living Peru" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-10-10.

- ^ "Gastronom铆a en Lima". go2peru.com.

- ^ "1-50 The Worlds 50 Best Restaurants". theworlds50best.com.

- ^ "Latin America's 50 Best Restaurants 1-50". theworlds50best.com.

- ^ "APEGA Sociedad Peruana de Gastronomía - ¿Qué es Apega?". apega.pe.

- ^ http://www.npr.org/blogs/thesalt/2014/09/17/349038162/mistura-food-fest-gives-peruvian-cuisine-a-chance-to-shine

- ^ Aunt Poison S.A.C. "Mistura.pe". mistura.pe.

- ^ Duncan Mackay. "Lima awarded 2019 Pan American and Parapan Games". insidethegames.biz - Olympic, Paralympic and Commonwealth Games News.

- ^ "Lima Metropolitana: Características de la Pequeńa Empresa y Micro Empresa por Conos y Distritos, 1993–1996". .inei.gob.pe. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ^ "Parque Kennedy - Miraflores - Top Rated Peru City Parks". Vivatravelguides.com. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- ^ "Historia" (in Spanish). Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ Lima (Peru) – MSN Encarta. Encarta.msn.com. Archived from the original on 2009-10-31. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Lima tiene m谩s de 6 mil colegios privados y cerca de 2 mil centros p煤blicos - seg煤n Mapcity - LaRepublica.pe". LaRepublica.pe.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j http://www.limacomovamos.org/cm/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/InformeEvaluandoLima2012.pdf

- ^ a b "Evaluación Censal de Estudiantes 2012 (ECE 2012)". minedu.gob.pe.

- ^ "Great Circle Mapper". Gc.kls2.com. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ^ "Ferrocarril Central Andino S.A." Ferrocarrilcentral.com.pe. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ^ "Bandurria – El sitio – Ferrocarril Lima Huacho". Huacho.info. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ^ a b "Periodo 1945–1965 – Galería de Fotos y Planos". Arqandina.com. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ^ "Lima : Planning a Trip: Getting Around". Frommers.com. 2008-07-28. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ^ "Getting around: Taxis, mototaxis and colectivos". Rough Guides. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ http://www.metropolitano.com.pe)

- ^ http://www.munlima.gob.pe/corredorazul

- ^ ":::.- San Borja en Bici -.:::". munisanborja.gob.pe.

- ^ a b http://www.inei.gob.pe/media/MenuRecursivo/boletines/estadisticas-ambientales-febrero-2014.pdf

- ^ a b c "Ciudad Nuestra - Segunda Encuesta Nacional Urbana de Victimización 2012 Perú". ciudadnuestra.org.

{{cite web}}: C1 control character in|title=at position 73 (help) - ^ Sister Cities International, Online Directory: Peru, Americas[dead link]. Retrieved July 14, 2007.

- ^ "Sister Cities International (SCI)". Sister-cities.org. Retrieved 2013-04-21.

- ^ "Bordeaux - Rayonnement européen et mondial". Mairie de Bordeaux (in French). Archived from the original on 2013-02-07. Retrieved 2013-07-29.

- ^ "Bordeaux-Atlas français de la coopération décentralisée et des autres actions extérieures". Délégation pour l’Action Extérieure des Collectivités Territoriales (Ministère des Affaires étrangères) (in French). Archived from the original on 2013-02-07. Retrieved 2013-07-29.

- ^ "Sister Cities". Beijing Municipal Government. Retrieved 2009-06-23.

- ^ "Sister Cities of Manila". © 2008–2009 City Government of Manila. Retrieved 2009-07-02.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ "Mapa Mundi de las ciudades hermanadas". Ayuntamiento de Madrid. Retrieved 2009-10-10.

- ^ Prefeitura.Sp – Descentralized Cooperation[dead link]

- ^ "International Relations – São Paulo City Hall – Official Sister Cities". Prefeitura.sp.gov.br. Retrieved 2010-04-17.

- ^ Lei Municipal de São Paulo 14471 de 2007 WikiSource Template:Pt icon

- ^ "Sister Cities, Public Relations". Guadalajara municipal government. Archived from the original on March 2, 2012. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

Further reading

General

- Nota etimológica: El topónimo Lima, Rodolfo Cerrón-Palomino, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú

- Lima Monumento Histórico, Margarita Cubillas Soriano, Lima, 1996

History

- Andrien, Kenneth. Crisis and decline: the Viceroyalty of Peru in the seventeenth century. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1985. ISBN 0-8263-0791-4

- Anna, Timothy. The fall of the royal government in Peru. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1979. ISBN 0-8032-1004-3

- Conlee, Christina, Jalh Dulanto, Carol Mackay and Charles Stanish. "Late Prehispanic sociopolitical complexity". In Helaine Silverman (ed.), Andean archaeology. Malden: Blackwell, 2004, pp. 209–236. ISBN 0-631-23400-4

- Dietz, Henry. Poverty and problem-solving under military rule: the urban poor in Lima, Peru. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1980. ISBN 0-292-76460-X

- Hemming, John. The conquest of the Incas. London: Macmillan, 1993. ISBN 0-333-51794-6

- Higgins, James. Lima. A cultural history. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-19-517891-2

- Higgins, James (editor). The Emancipation of Peru: British Eyewitness Accounts, 2014. Online at https://sites.google.com/site/jhemanperu

- Template:Es icon Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. Lima Metropolitana perfil socio-demográfico. Lima: INEI, 1996.

- Klarén, Peter. Peru: society and nationhood in the Andes. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-19-506928-5

- Ramón, Gabriel. "The script of urban surgery: Lima, 1850–1940". In Arturo Almandoz (ed.), Planning Latin America's capital cities, 1850–1950. New York: Routledge, 2002, pp. 170–192. ISBN 0-415-27265-3

- Walker, Charles. "The upper classes and their upper stories: architecture and the aftermath of the Lima earthquake of 1746". Hispanic American Historical Review 83 (1): 53–82 (February 2003).

Demographics

- Template:Es icon Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática, Perfil Sociodemográfico del Perú. Lima: INEI, 2008.

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Urban Agglomerations 2007. New York (June 2008).

External links

- Template:Es icon Municipality of Lima

- MSN Map

- 1.40 gigapixel image of Lima

Lima travel guide from Wikivoyage

Lima travel guide from Wikivoyage