Western (genre): Difference between revisions

m delink United States per WP:OVERLINK |

Cyberbot II (talk | contribs) Rescuing 1 sources, flagging 0 as dead, and archiving 2 sources. #IABot |

||

| Line 156: | Line 156: | ||

[[George Lucas]]'s ''[[Star Wars]]'' films use many elements of a Western, and Lucas has said he intended for ''Star Wars'' to revitalize cinematic mythology, a part the Western once held. The [[Jedi]], who take their name from [[Jidaigeki]], are modeled after samurai, showing the influence of Kurosawa. The character [[Han Solo]] dressed like an archetypal gunslinger, and the [[Mos Eisley Cantina]] is much like an Old West saloon. |

[[George Lucas]]'s ''[[Star Wars]]'' films use many elements of a Western, and Lucas has said he intended for ''Star Wars'' to revitalize cinematic mythology, a part the Western once held. The [[Jedi]], who take their name from [[Jidaigeki]], are modeled after samurai, showing the influence of Kurosawa. The character [[Han Solo]] dressed like an archetypal gunslinger, and the [[Mos Eisley Cantina]] is much like an Old West saloon. |

||

Meanwhile, films such as ''[[The Big Lebowski]]'', which plucked actor Sam Elliott out of the Old West and into a Los Angeles bowling alley, and ''[[Midnight Cowboy]]'', about a Southern-boy-turned-gigolo in New York (who disappoints a client when he doesn't measure up to Gary Cooper), transplanted Western themes into modern settings for both purposes of parody and homage.<ref>Robert Silva. "[http://blogs.amctv.com/future-of-classic/2009/05/cowboys-in-non-westerns.php Not From 'Round Here... Cowboys Who Pop Up Outside the Old West] |

Meanwhile, films such as ''[[The Big Lebowski]]'', which plucked actor Sam Elliott out of the Old West and into a Los Angeles bowling alley, and ''[[Midnight Cowboy]]'', about a Southern-boy-turned-gigolo in New York (who disappoints a client when he doesn't measure up to Gary Cooper), transplanted Western themes into modern settings for both purposes of parody and homage.<ref>Robert Silva. "[http://blogs.amctv.com/future-of-classic/2009/05/cowboys-in-non-westerns.php Not From 'Round Here... Cowboys Who Pop Up Outside the Old West]." ''Future of the Classic''. {{wayback|url=http://blogs.amctv.com/future-of-classic/2009/05/cowboys-in-non-westerns.php |date=20091213203944 }}</ref> |

||

==Literature== |

==Literature== |

||

Revision as of 12:55, 6 February 2016

The Western is a genre of various arts, such as comics, fiction, film, games, radio, and television which tell stories set primarily in the later half of the 19th century in the American Old West, often centering on the life of a nomadic cowboy or gunfighter.[1] Westerns often stress the harshness of the wilderness and frequently set the action in an arid, desolate landscape of deserts and mountains. Specific settings include ranches, small frontier towns and saloons of the Wild West. Characters typically include Native Americans, bandits, lawmen, outlaws and soldiers. Some are set in the American colonial era.

Western films first became well-attended in the 1930s, and were highly popular throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Many of the most acclaimed Westerns were released during this time – including High Noon (1952), Shane (1953), The Searchers (1956), and The Wild Bunch (1969). Classic Westerns such as these have been the inspiration for various films about Western-type characters in contemporary settings, such as Junior Bonner (1972) set in the 1970s and The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada (2005) in the 21st century. The Western was the most popular Hollywood genre from the early 20th century to the 1960s.[2]

Themes

The Western genre sometimes portrays the conquest of the wilderness and the subordination of nature in the name of civilization or the confiscation of the territorial rights of the original, Native American, inhabitants of the frontier.[1] The Western depicts a society organized around codes of honor and personal, direct or private justice such as the feud, rather than one organized around rationalistic, abstract law, in which social order is maintained predominately through relatively impersonal institutions. The popular perception of the Western is a story that centers on the life of a semi-nomadic wanderer, usually a cowboy or a gunfighter.[1] A showdown or duel at high noon featuring two or more gunfighters is a stereotypical scene in the popular conception of Westerns.

In some ways, such protagonists may be considered the literary descendants of the knight errant which stood at the center of earlier extensive genres such as the Arthurian Romances.[1] Like the cowboy or gunfighter of the Western, the knight errant of the earlier European tales and poetry was wandering from place to place on his horse, fighting villains of various kinds and bound to no fixed social structures but only to his own innate code of honor. And like knights errant, the heroes of Westerns frequently rescue damsels in distress. Similarly, the wandering protagonists of Westerns share many of the characteristics equated with the image of the ronin in modern Japanese culture.

The Western typically takes these elements and uses them to tell simple morality tales, although some notable examples (e.g. the later Westerns of John Ford or Clint Eastwood's Unforgiven) are more morally ambiguous. Westerns often stress the harshness of the wilderness and frequently set the action in an arid, desolate landscape. Specific settings include isolated forts, ranches and homesteads; the Native American village; or the small frontier town with its saloon, general store, livery stable and jailhouse. Apart from the wilderness, it is usually the saloon that emphasizes that this is the Wild West: it is the place to go for music (raucous piano playing), women (often prostitutes), gambling (draw poker or five card stud), drinking (beer or whiskey), brawling and shooting. In some Westerns, where civilization has arrived, the town has a church and a school; in others, where frontier rules still hold sway, it is, as Sergio Leone said, "where life has no value".

Film

Characteristics

The American Film Institute defines western films as those "set in the American West that embod[y] the spirit, the struggle and the demise of the new frontier."[3] The term Western, used to describe a narrative film genre, appears to have originated with a July 1912 article in Motion Picture World Magazine.[4] Most of the characteristics of Western films were part of 19th century popular Western fiction and were firmly in place before film became a popular art form.[5] Western films commonly feature protagonists such as cowboys, gunslingers, and bounty hunters, who are often depicted as semi-nomadic wanderers who wear Stetson hats, bandannas, spurs, and buckskins, use revolvers or rifles as everyday tools of survival, and ride between dusty towns and cattle ranches on trusty steeds.

Western films were enormously popular in the silent era. With the advent of sound in 1927-28, the major Hollywood studios rapidly abandoned Westerns,[citation needed] leaving the genre to smaller studios and producers. These smaller organizations churned out countless low-budget features and serials in the 1930s. By the late 1930s the Western film was widely regarded as a "pulp" genre in Hollywood, but its popularity was dramatically revived in 1939 by major studio productions such as Dodge City starring Errol Flynn, Jesse James with Tyrone Power, Union Pacific with Joel McCrea, Destry Rides Again featuring James Stewart and Marlene Dietrich, and perhaps most notably the release of John Ford's landmark Western adventure Stagecoach, which became one of the biggest hits of the year. Released through United Artists, Stagecoach made John Wayne a mainstream screen star in the wake of a decade of headlining B westerns. Wayne had been introduced to the screen ten years earlier as the leading man in director Raoul Walsh's widescreen The Big Trail, which failed at the box office, due in part to exhibitors' inability to switch over to widescreen during the Depression. After the Western's renewed commercial successes in the late 1930s, the popularity of the Western continued to rise until its peak in the 1950s, when the number of Western films produced outnumbered all other genres combined.[6]

Western films often depict conflicts with Native Americans. While early Eurocentric Westerns frequently portray the "Injuns" as dishonorable villains, the later and more culturally neutral Westerns (notably those directed by John Ford) gave Native Americans a more sympathetic treatment. Other recurring themes of Westerns include Western treks or perilous journeys (e.g. Stagecoach) or groups of bandits terrorising small towns such as in The Magnificent Seven.

Early Westerns were mostly filmed in the studio, just like other early Hollywood films, but when location shooting became more common from the 1930s, producers of Westerns used desolate corners of Arizona, California, Colorado, Kansas, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Texas, Utah, or Wyoming. Productions were also filmed on location at movie ranches.

Often, the vast landscape becomes more than a vivid backdrop; it becomes a character in the film. After the early 1950s, various wide screen formats such as cinemascope (1953) and VistaVision used the expanded width of the screen to display spectacular Western landscapes. John Ford's use of Monument Valley as an expressive landscape in his films from Stagecoach (1939) to Cheyenne Autumn (1965) "present us with a mythic vision of the plains and deserts of the American West, embodied most memorably in Monument Valley, with its buttes and mesas that tower above the men on horseback, whether they be settlers, soldiers, or Native Americans".[7]

Subgenres

Author and screenwriter Frank Gruber listed seven plots for Westerns:[8][9]

- Union Pacific story. The plot concerns construction of a railroad, a telegraph line, or some other type of modern technology or transportation. Wagon train stories fall into this category.

- Ranch story. The plot concerns threats to the ranch from rustlers or large landowners attempting to force out the proper owners.

- Empire story. The plot involves building a ranch empire or an oil empire from scratch, a classic rags-to-riches plot.

- Revenge story. The plot often involves an elaborate chase and pursuit by a wronged individual, but it may also include elements of the classic mystery story.

- Cavalry and Indian story. The plot revolves around "taming" the wilderness for white settlers.

- Outlaw story. The outlaw gangs dominate the action.

- Marshal story. The lawman and his challenges drive the plot.

Gruber said that good writers used dialogue and plot development to develop these basic plots into believable stories.[9] Other subgenres include the Spaghetti Western, the epic western, singing cowboy westerns, and a few comedy westerns; such as: Along Came Jones (1945), in which Gary Cooper spoofed his western persona; The Sheepman (1958), with Glenn Ford poking fun at himself; and Cat Ballou (1965), with a drunk Lee Marvin atop a drunk horse. In the 1960s and 1970s, the Western was re-invented with the revisionist Western.[10]

Classical Western

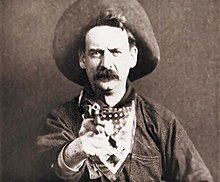

The Great Train Robbery (1903), Edwin S. Porter's film starring Broncho Billy Anderson, is often cited as the first Western, though George N. Fenin and William K. Everson point out that the "Edison company had played with Western material for several years prior to The Great Train Robbery. " Nonetheless, they concur that Porter's film "set the pattern—of crime, pursuit, and retribution—for the Western film as a genre."[11] The film's popularity opened the door for Anderson to become the screen's first cowboy star; he made several hundred Western film shorts. So popular was the genre that he soon faced competition from Tom Mix and William S. Hart.

The Golden Age of the Western is epitomized by the work of several directors, most prominent among them, John Ford (My Darling Clementine, The Horse Soldiers, The Searchers). Others include: Howard Hawks (Red River, Rio Bravo), Anthony Mann (Man of the West, The Man from Laramie), Budd Boetticher (Seven Men from Now), Delmer Daves (The Hanging Tree, 3:10 to Yuma), John Sturges (The Magnificent Seven, Last Train from Gun Hill), and Robert Aldrich (Vera Cruz, Ulzana's Raid).[citation needed]

Acid Western

Film critic Jonathan Rosenbaum refers[specify] to a makeshift 1960s and 1970s genre called the Acid Western, associated with Dennis Hopper, Jim McBride, and Rudy Wurlitzer, as well as films like Monte Hellman's The Shooting (1966), Alejandro Jodorowsky's bizarre experimental film El Topo (The Mole) (1970), and Robert Downey Sr.'s Greaser's Palace (1972). The 1970 film El Topo is an allegorical cult Western and underground film about the eponymous character, a violent black-clad gunfighter, and his quest for enlightenment. The film is filled with bizarre characters and occurrences, use of maimed and dwarf performers, and heavy doses of Christian symbolism and Eastern philosophy. Some Spaghetti Westerns also crossed over into the Acid Western genre, such as Enzo G. Castellari's mystical Keoma (1976), a Western reworking of Ingmar Bergman's metaphysical The Seventh Seal (1957).

More recent Acid Westerns include Alex Cox's film Walker (1987) and Jim Jarmusch's film Dead Man (1995). Rosenbaum describes the Acid Western as "formulating a chilling, savage frontier poetry to justify its hallucinated agenda"; ultimately, he says, the Acid Western expresses a counterculture sensibility to critique and replace capitalism with alternative forms of exchange.[12]

Charro, Cabrito or Chili Westerns

Charro Westerns have been a standard of Mexican cinema often featuring musical stars as well as action had been a feature of the Mexican cinema since the 1930s.[13][14]

Contemporary Western

Also known as Neo-Westerns, these films have contemporary American settings, and they utilize Old West themes and motifs (a rebellious anti-hero, open plains and desert landscapes, and gunfights). For the most part, they still take place in the American West and reveal the progression of the Old West mentality into the late 20th and early 21st centuries. This subgenre often features Old West-type characters struggling with displacement in a "civilized" world that rejects their outdated brand of justice.

Examples include Hud, starring Paul Newman (1963); Sam Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch (1969); The Getaway (1972); Junior Bonner (1972); Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974); Robert Altman's McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971); J. W. Coop, directed/co-written by and starring Cliff Robertson; Simon Wincer's Quigley Down Under; Robert Rodríguez's El Mariachi (1992) and Once Upon a Time in Mexico (2003); John Sayles's Lone Star (1996); Tommy Lee Jones's The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada (2005); Ang Lee's Brokeback Mountain (2005); Wim Wenders's Don't Come Knocking (2005); Hearts of the West starring Jeff Bridges (1975); Alan J. Pakula's Comes a Horseman (1978); John Sturges's Bad Day at Black Rock (1955); the Coen brothers Academy Award-winning No Country For Old Men (2007); and Justified (2010-present). Call of Juarez: The Cartel is an example of a Neo-Western video game. Likewise, the television series Breaking Bad, which takes place in modern times, features many examples of Western archetypes. According to creator Vince Gilligan, "After the first Breaking Bad episode, it started to dawn on me that we could be making a contemporary western. So you see scenes that are like gunfighters squaring off, like Clint Eastwood and Lee Van Cleef — we have Walt and others like that."[15]

The precursor to these[citation needed] was the radio series Tales of the Texas Rangers (1950–1952), with Joel McCrea, a contemporary detective drama set in Texas, featuring many of the characteristics of traditional Westerns.

Electric Western

The 1971 film Zachariah starring John Rubinstein, Don Johnson and Pat Quinn was billed as, "The first electric Western."[16] The film featured multiple performing rock bands in an otherwise American West setting.[16]

Zachariah featured appearances and music supplied by rock groups from the 1970s, including the James Gang[16] and Country Joe and the Fish as "The Cracker Band."[16] Fiddler Doug Kershaw had a musical cameo[16] as does Elvin Jones as a gunslinging drummer named Job Cain.[16]

The independent film Hate Horses starring Dominique Swain, Ron Thompson and Paul Dooley billed itself as, "The second electric Western."[17]

Euro-Western

Euro Westerns are Western genre films made in Western Europe. The term can sometimes, but not necessarily, include the Spaghetti Western subgenre (see below). One example of a Euro Western is the Anglo-Spanish film The Savage Guns (1961). Several Euro-Western films, nicknamed Sauerkraut Westerns[18] because they were made in Germany and shot in Yugoslavia, were derived from stories by novelist Karl May and were film adaptations of May's work.

Fantasy Western

Fantasy Westerns mixed in fantasy settings and themes, and may include Fantasy mythology as background. Some famous examples are Stephen King's The Dark Tower series of novels, the Vertigo comics series Preacher, and Keiichi Sigsawa's light novel series, Kino's Journey, illustrated by Kouhaku Kuroboshi.

Florida Western

Florida Westerns, also known as Cracker Westerns, are set in Florida during the Second Seminole War. An example would be Distant Drums (1951) starring Gary Cooper.

Horror Western

A developing subgenre,[citation needed] with roots in films such as Billy the Kid vs. Dracula (1966), which depicts the legendary outlaw Billy the Kid fighting against the notorious vampire. Another example is The Ghoul Goes West, an unproduced Ed Wood film to star Bela Lugosi as Dracula in the Old West.[citation needed] Recent examples include the films Ravenous (1999), which deals with cannibalism at a remote US army outpost; The Burrowers (2008), about a band of trackers who are stalked by the titular creatures; and Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter (2012).

Curry Westerns and Indo Westerns

The first Western films made in India - Mosagaalaku Mosagaadu (1970), made in Telugu, Mappusakshi (Malayalam),[citation needed] Ganga (1972), and Jakkamma (Tamil)[citation needed] - were based on Classic Westerns. Thazhvaram (1990), the Malayalam film directed by Bharathan and written by noted writer M. T. Vasudevan Nair, is perhaps the most resemblant of the Spaghetti Westerns in terms of production and cinematic techniques. Earlier Spaghetti Westerns laid the groundwork for such films as Adima Changala (1971) starring Prem Nazir, a hugely popular "zapata Spaghetti Western film in Malayalam, and Sholay (1975) Khote Sikkay (1973) and Thai Meethu Sathiyam (1978) are notable Curry Westerns.

Takkari Donga (2002), starring Telugu Maheshbabu, was applauded by critics but an average runner at box office. Quick Gun Murugun (2009), an Indian comedy film which spoofs Indian Western movies, is based on a character created for television promos at the time of the launch of the music network Channel [V] in 1994, which had cult following.[citation needed] Irumbukkottai Murattu Singam (2010), a Western adventure comedy film, based on cowboy movies and paying homages to the John Wayne, Clint Eastwood, and Jaishankar, was made in Tamil.

Martial arts Western

While many of these mash-ups (e.g., Billy Jack (1971) and its sequel The Trial of Billy Jack (1974)) are cheap exploitation films, others are more serious dramas such as the Kung Fu TV series, which ran from 1972-1975. Comedy examples include the Jackie Chan and Owen Wilson collaborations Shanghai Noon (2000) and its sequel Shanghai Knights (2003). Further sub-divisions of this subgenre include Ninja Westerns (such as Chuck Norris' contemporary action film The Octagon (1980)) and Samurai Westerns (incorporating samurai cinema themes), such as Red Sun (1971) with Charles Bronson and Toshiro Mifune.

Meat pie Western

The Meat pie Western (a slang term which plays on the Italo-western moniker "Spaghetti Western") is an American Western-style movie or TV series set in Australia, especially the Australian Outback.[19] Shows such as Rangle River (1936), Kangaroo (1952), The Man from Snowy River (1982), and Five Mile Creek (1983-85), and the theatrical film Quigley Down Under (1991) are all representative of the genre. The term is used to differentiate more Americanized Australian films from those with a more historical basis, such as those about bushrangers.[20]

Northwestern

The Northern genre is a subgenre of Westerns taking place in Alaska or Western Canada. Examples include several versions of the Rex Beach novel, The Spoilers (including 1930's The Spoilers, with Gary Cooper, and 1942's The Spoilers, with Marlene Dietrich, Randolph Scott and Wayne); The Far Country (1954) with James Stewart; North to Alaska (1960) with Wayne; and Death Hunt (1981) with Charles Bronson.

Ostern

Osterns, also known as "Red Western"s, are produced in Eastern-Europe. They were popular in Communist Eastern European countries and were a particular favorite of Joseph Stalin,[citation needed] and usually portrayed the American Indians sympathetically, as oppressed people fighting for their rights, in contrast to American Westerns of the time, which frequently portrayed the Indians as villains. Osterns frequently featured Gypsies or Turkic people in the role of the Indians,[citation needed] due to the shortage of authentic Indians in Eastern Europe.[citation needed]

Gojko Mitić portrayed righteous, kind-hearted, and charming Indian chiefs (e.g., in Die Söhne der großen Bärin (1966) directed by Josef Mach). He became honorary chief of the Sioux tribe, when he visited the United States in the 1990s and the television crew accompanying him showed the tribe one of his films. American actor and singer Dean Reed, an expatriate who lived in East Germany, also starred in several Ostern films.

Pornographic Western

The most rare of the Western subgenres, pornographic Westerns use the Old West as a background for stories primarily focused on erotica. The three major examples of the porn Western film are Russ Meyer's nudie-cutie Wild Gals of the Naked West (1962), and the hardcore A Dirty Western (1975) and Sweet Savage (1979). Sweet Savage starred Aldo Ray, a veteran actor who had appeared in traditional Westerns, in a non-sex role. Some critics may include Alejandro Jodorowsky's El Topo (1970) in this subgenre.[who?][why?] Among videogames, Atari 2600's Custer's Revenge (1982) is an infamous example, considered to be one of the worst video games of all time.

Revisionist Western

After the early 1960s, many American filmmakers began to question and change many traditional elements of Westerns, and to make Revisionist Westerns that encouraged audiences to question the simple hero-versus-villain dualism and the morality of using violence to test one's character or to prove oneself right. One major revision was the increasingly positive representation of Native Americans, who had been treated as "savages" in earlier films. Examples of such revisionist Westerns include Richard Harris' A Man Called Horse (1970), Little Big Man (1970), Man in the Wilderness (1971), The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976), Dances with Wolves (1990), and Dead Man (1995). A few earlier Revisionist Westerns gave women more powerful roles, such as Westward the Women (1951) starring Robert Taylor. Another earlier work encompassed all these features, The Last Wagon (1956). In it, Richard Widmark played a white man raised by Comanches and persecuted by whites, with Felicia Farr and Susan Kohner playing young women forced into leadership roles.

Science fiction Western

The science fiction Western places science fiction elements within a traditional Western setting. Examples include Jesse James Meets Frankenstein's Daughter (1965),The Valley of Gwangi (1969) featuring cowboys and dinosaurs. Westworld (1973) and its sequel Futureworld (1976), Back to the Future Part III (1990), Wild Wild West (1999), and Cowboys & Aliens (2011).

Space Western

The Space Western or Space Frontier is a subgenre of science fiction which uses the themes and tropes of Westerns within science fiction stories. Subtle influences may include exploration of new, lawless frontiers, while more overt influences may feature literal cowboys in outer space who use ray guns and ride robotic horses. Examples include the American television series Brave Starr (which aired original episodes from September 1987 to February 1988) and Firefly (created by Joss Whedon in 2002), and the films Battle Beyond the Stars (1980), which is a remake of The Magnificent Seven; Outland (1981), which is a remake of High Noon; and Serenity (2005, based on Firefly). The classic western genre has also been a major influence on science fiction films such as the original Star Wars movie of 1977.

Spaghetti Western

During the 1960s and 1970s, a revival of the Western emerged in Italy with the "Spaghetti Westerns" also known as "Italo-Westerns". The most famous of them is The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1966). Many of these films are low-budget affairs, shot in locations (for example, the Spanish desert region of Almería) chosen for their inexpensive crew and production costs as well as their similarity to landscapes of the Southwestern United States. Spaghetti Westerns were characterized by the presence of more action and violence than the Hollywood Westerns. Also, the protagonists usually acted out of more selfish motives (money or revenge being the most common) than in the classical westerns.[21] Some Spaghetti Westerns demythologized the American Western tradition, and some films from the genre are considered revisionist Westerns.

The Western films directed by Sergio Leone were felt by some to have a different tone than the Hollywood Westerns.[22] Veteran American actors Charles Bronson, Lee Van Cleef and Clint Eastwood[22] became famous by starring in Spaghetti Westerns, although the films also provided a showcase for other noted actors such as James Coburn, Henry Fonda, Klaus Kinski, and Jason Robards. Eastwood, previously the lead in the television series Rawhide, unexpectedly found himself catapulted into the forefront of the film industry by Leone's A Fistful of Dollars.[22]

Weird Western

The Weird Western subgenre blends elements of a classic Western with other elements. The Wild Wild West television series, television movies, and 1999 film adaptation blend the Western with steampunk. The Jonah Hex franchise also blends the Western with superhero elements. The film Western Religion (2015), by writer and director James O'Brien, introduces the Devil into a traditional wild west setting.

Western satire

This subgenre is imitative in style in order to mock, comment on, or trivialize the Western genre's established traits, subjects, auteurs' styles, or some other target by means of humorous, satiric, or ironic imitation. Examples include Carry On Cowboy (1965), The Hallelujah Trail (1965), The Scalphunters (1968), Support Your Local Sheriff! (1969), Support Your Local Gunfighter (1971), Blazing Saddles (1974), Rustlers' Rhapsody (1985), Three Amigos (1986), Maverick (1994), Quick Draw (2013) and A Million Ways to Die in the West (2014).

Genre studies

In the 1960s academic and critical attention to cinema as a legitimate art form emerged. American Westerns of the mid 20th Century romanticize the ideas of loyalty and virtue.[citation needed] Westerns of the late 20th Century possess a more negative view of the early American frontier. With the increased attention, film theory was developed to attempt to understand the significance of film. From this environment emerged (in conjunction with the literary movement) an enclave of critical studies called genre studies. This was primarily a semantic and structuralist approach to understanding how similar films convey meaning.

One of the results of genre studies is that some[who?] have argued that "Westerns" need not take place in the American West or even in the 19th century, as the codes can be found in other types of films. For example, a very typical Western plot is that an eastern lawman heads west, where he matches wits and trades bullets with a gang of outlaws and thugs, and is aided by a local lawman who is well-meaning but largely ineffective until a critical moment when he redeems himself by saving the hero's life. This description can be used to describe any number of Westerns, but also other films such as Die Hard (itself a loose reworking of High Noon), Top Gun, and Akira Kurosawa's Seven Samurai which are frequently cited examples of films that do not take place in the American West but have many themes and characteristics common to Westerns. Likewise, films set in the American Old West may not necessarily be considered "Westerns."

Influences

Being period drama pieces, both the Western and samurai genre influenced each other in style and themes throughout the years.[23] For instance, The Magnificent Seven was a remake of Kurosawa's Seven Samurai, and A Fistful of Dollars was a remake of Kurosawa's Yojimbo, which itself was inspired by Red Harvest, an American detective novel by Dashiell Hammett. Kurosawa was influenced by American Westerns and was a fan of the genre, most especially John Ford.[24][25]

Despite the Cold War, the Western was a strong influence on Eastern Bloc cinema, which had its own take on the genre, the so-called "Red Western" or "Ostern". Generally these took two forms: either straight Westerns shot in the Eastern Bloc, or action films involving the Russian Revolution and civil war and the Basmachi rebellion.

An offshoot of the Western genre is the "post-apocalyptic" Western, in which a future society, struggling to rebuild after a major catastrophe, is portrayed in a manner very similar to the 19th century frontier. Examples include The Postman and the Mad Max series, and the computer game series Fallout. Many elements of space travel series and films borrow extensively from the conventions of the Western genre. This is particularly the case in the space Western subgenre of science fiction. Peter Hyams' Outland transferred the plot of High Noon to Io, moon of Jupiter. Gene Roddenberry, the creator of the Star Trek series, pitched his show as "Wagon Train to the stars" early on, but admitted later that this was more about getting it produced in a time that loved Western-themed TV series than about its actual content.[citation needed] The Book of Eli depicts the post apocalypse as a Western with large knives.

More recently, the space opera series Firefly used an explicitly Western theme for its portrayal of frontier worlds. Anime shows like Cowboy Bebop, Trigun and Outlaw Star have been similar mixes of science fiction and Western elements. The science fiction Western can be seen as a subgenre of either Westerns or science fiction. Elements of Western films can be found also in some films belonging essentially to other genres. For example, Kelly's Heroes is a war film, but action and characters are Western-like. The British film Zulu set during the Anglo-Zulu War has sometimes been compared to a Western, even though it is set in South Africa.

The character played by Humphrey Bogart in film noir films such as Casablanca and To Have and Have Not—an individual bound only by his own private code of honor—has a lot in common with the classic Western hero. In turn, the Western, has also explored noir elements, as with the films Pursued and Sugar Creek.

In many of Robert A. Heinlein's books, the settlement of other planets is depicted in ways explicitly modeled on American settlement of the West. For example, in his Tunnel in the Sky settlers set out to the planet "New Canaan", via an interstellar teleporter portal across the galaxy, in Conestoga wagons, their captain sporting mustaches and a little goatee and riding a Palomino horse—with Heinlein explaining that the colonists would need to survive on their own for some years, so horses are more practical than machines.

Stephen King's The Dark Tower is a series of seven books that meshes themes of Westerns, high fantasy, science fiction and horror. The protagonist Roland Deschain is a gunslinger whose image and personality are largely inspired by the "Man with No Name" from Sergio Leone's films. In addition, the superhero fantasy genre has been described as having been derived from the cowboy hero, only powered up to omnipotence in a primarily urban setting. The Western genre has been parodied on a number of occasions, famous examples being Support Your Local Sheriff!, Cat Ballou, Mel Brooks's Blazing Saddles, and Rustler's Rhapsody.

George Lucas's Star Wars films use many elements of a Western, and Lucas has said he intended for Star Wars to revitalize cinematic mythology, a part the Western once held. The Jedi, who take their name from Jidaigeki, are modeled after samurai, showing the influence of Kurosawa. The character Han Solo dressed like an archetypal gunslinger, and the Mos Eisley Cantina is much like an Old West saloon.

Meanwhile, films such as The Big Lebowski, which plucked actor Sam Elliott out of the Old West and into a Los Angeles bowling alley, and Midnight Cowboy, about a Southern-boy-turned-gigolo in New York (who disappoints a client when he doesn't measure up to Gary Cooper), transplanted Western themes into modern settings for both purposes of parody and homage.[26]

Literature

Western fiction is a genre of literature set in the American Old West, most commonly between the years of 1860 and 1900. The first critically recognized Western was The Virginian (1902) by Owen Wister.[citation needed] Other well-known writers of Western fiction include Zane Grey, from the early 1900s, Ernest Haycox, Luke Short, and Louis L'Amour, from the mid 20th century. Many writers better known in other genres, such as Leigh Brackett, Elmore Leonard, and Larry McMurtry, have also written Western novels. The genre's popularity peaked in the 1960s, due in part to the shuttering of many pulp magazines, the popularity of televised Westerns, and the rise of the spy novel. Readership began to drop off in the mid- to late 1970s and reached a new low in the 2000s. Most bookstores, outside of a few Western states, now only carry a small number of Western novels and short story collections.[27]

Literary forms that share similar themes include stories of the American frontier, the gaucho literature of Argentina, and tales of the settlement of the Australian Outback.

Television

Television Westerns are a subgenre of the Western. When television became popular in the late 1940s and 1950s, TV Westerns quickly became an audience favorite.[28] Beginning with re-broadcasts of existing films, a number of movie cowboys had their own TV shows. As demand for the Western increased, new stories and stars were introduced. A number of long-running TV Westerns became classics in their own right, such as: Bonanza (1959-1973), Gunsmoke (1955-1975), Have Gun – Will Travel (1957-1963), Maverick (1957-1962), Rawhide (1959-1966), Sugarfoot (1957-1961), The Rifleman (1958-1963), The Big Valley (1965-1969), The Virginian (1962-1971), and Wagon Train (1957-1965).

The peak year for television Westerns was 1959, with 26 such shows airing during primetime. Increasing costs of American television production weeded out most action half hour series in the early 1960s, and their replacement by hour-long television shows, increasingly in color.[29] Traditional Westerns died out in the late 1960s as a result of network changes in demographic targeting along with pressure from parental television groups. Future entries in the genre would incorporate elements from other genera, such as crime drama and mystery whodunit elements. Western shows from the 1970s included Hec Ramsey, Kung Fu, Little House on the Prairie, and McCloud. In the 1990s and 2000s, hour-long Westerns and slickly packaged made-for-TV movie Westerns were introduced, such as: Lonesome Dove (1989) and Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman. As well, new elements were once again added to the Western formula, such as the Western-science fiction show Firefly, created by Joss Whedon in 2002. Deadwood was a critically acclaimed Western series which aired on HBO from 2004 through 2006.

Visual art

A number of visual artists focused their work on representations of the American Old West. American West-oriented art is sometimes referred to as "Western Art" by Americans. This relatively new category of art includes paintings, sculptures, and sometimes Native American crafts. Initially, subjects included exploration of the Western states and cowboy themes. Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell are two artists who captured the "Wild West" on canvas.[30] Some art museums, such as the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Wyoming and the Autry National Center in Los Angeles, feature American Western Art.[31]

Other media

The popularity of Westerns extends beyond films, literature, television, and visual art to include numerous other media forms.

Anime and manga

With anime and manga, the genre tends towards the Science fiction Western [e.g., Cowboy Bebop (1998 anime), Trigun (manga serialized in 1996), and Outlaw Star (manga)], although contemporary Westerns also appear (e.g., El Cazador de la Bruja, a 2007 anime television series set in modern-day Mexico).

Comics

Western comics have included serious entries (such as the classic comics of the late 1940s and early 1950s[specify]), cartoons, and parodies (such as Cocco Bill and Lucky Luke). In the 1990s and 2000s, Western comics leaned toward the Weird West subgenre, usually involving supernatural monsters, or Christian iconography as in Preacher. However, more traditional Western comics are found throughout this period (e.g., Jonah Hex and Loveless).

Games

Western arcade games, computer games, role-playing games, and video games are often either straightforward Westerns or Western Horror hybrids. Some Western themed-computer games include the The Oregon Trail (1971), Mad Dog McCree (1990), Sunset Riders (1991), Outlaws (1997), Red Dead Revolver (2004), Gun (2005), Call of Juarez (2007), and Red Dead Redemption (2010). Other video games adapt the Science fiction Western or Weird West subgenres (e.g., Fallout (1997), Gunman Chronicles (2000), Darkwatch (2005), the Borderlands series (first released in 2009) and Fallout: New Vegas (2010)).

Radio dramas

Western radio dramas were very popular from the 1930s to the 1960s. Some popular shows include The Lone Ranger (first broadcast in 1933), The Cisco Kid (first broadcast in 1942), Dr. Sixgun (first broadcast in 1954), Have Gun–Will Travel (first broadcast in 1958), and Gunsmoke (first broadcast in 1952).[32]

See also

|

|

References

- ^ a b c d Newman, Kim (1990). Wild West Movies. Bloomsbury.

- ^ Indick, William. The Psychology of the Western. Pg. 2. McFarland, Aug 27, 2008

- ^ "America's 10 Greatest Films in 10 Classic Genres". American Film Institute. Retrieved 2010-06-06.

- ^ McMahan, Alison; Alice Guy Blache: Lost Visionary of the Cinema; New York: Continuum, 2002; 133

- ^ Henry Nash Smith, Virgin Land: The American West as Symbol and Myth, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1950.

- ^ Indick, William. The Psychology of the Western. Pg. 2 McFarland, Aug 27, 2008.

- ^ Cowie, Peter (2004). John Ford and the American West. New York: Harry Abrams Inc. ISBN 0-8109-4976-8.

- ^ Gruber, Frank The Pulp Jungle Sherbourne Press, 1967

- ^ a b "No Soft Soap About New And Improved Computer Games". Computer Gaming World (editorial). October 1990. p. 80. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- ^ Bandy, Mary Lea; Kevin Stoehr (2012). Ride, Boldly Ride: The Evolution of the American Western. Berkeley/Los Angeles/London: University of California Press. p. 234. ISBN 978-0-520-25866-2.

- ^ Fenin, George N.; William K. Everson (1962). The Western: From Silents to Cinerama. New York: Bonanza Books. p. 47.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Jonathan (June 26, 1996). "Acid Western: Dead Man". "Chicago Reader".

- ^ Rashotte, Ryan Narco Cinema: Sex, Drugs, and Banda Music in Mexico's B-Filmography Palgrave Macmillan, 23 April 2015

- ^ p. 6 Figueredo, Danilo H. Revolvers and Pistolas, Vaqueros and Caballeros: Debunking the Old West ABC-CLIO, 9 Dec 2014

- ^ "Contemporary Western: An interview with Vince Gilligan". News. United States: Local iQ. 27 March 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f Greenspun, Roger (January 25, 1971). "Zachariah (1970) Screen: 'Zachariah,' an Odd Western". The New York Times.

- ^ Hate Horses - Official Trailer. YouTube. 2015.

- ^ The BFI Companion to the Western. A. Deutsch. 1993. p. 118.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Ross Cooper, Andrew Pike (1998). Australian Film 1900-1977: A Guide to Feature Film Production. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. p. 310. ISBN 0195507843.

- ^ "HOLLYWOOD". The Australian Women's Weekly. November 4, 1981. p. 157. Retrieved December 28, 2011.

- ^ Frayling, Christopher (1998). Spaghetti Westerns: Cowboys and Europeans from Karl May to Sergio Leone. IB Tauris.

- ^ a b c Billson, Anne (September 15, 2014). "Forget the Spaghetti Western – try a Curry Western or a Sauerkraut one". The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ Cowboys and Shoguns: The American Western, Japanese Jidaigeki, and Cross-Cultural Exchange PDF.[1]

- ^ Patrick Crogan. "Translating Kurosawa." Senses of Cinema.

- ^ Shaw, Justine. "Star Wars Origins". Far Cry from the Original Site. Retrieved December 20, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) December 14, 2015 - ^ Robert Silva. "Not From 'Round Here... Cowboys Who Pop Up Outside the Old West." Future of the Classic. Archived 2009-12-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ McVeigh, Stephen (2007). The American Western. Edinburgh University Press.

- ^ Gary A. Yoggy, Riding the Video Range: The Rise and Fall of the Western on Television (McFarland & Company, 1995)

- ^ Kisseloff, J. (editor) The Box: An Oral History of Television

- ^ Buscombe, Edward (1984). "Painting the Legend: Frederic Remington and the Western". Cinema Journal. pp. 12–27.

- ^ Goetzmann, William H. (1986). The West of the Imagination. New York: Norton.

- ^ "Old Time Radio Westerns". otrwesterns.com.

Further reading

- Buscombe, Edward, and Christopher Brookeman. The BFI Companion to the Western (A. Deutsch, 1988); BFI = British Film Institute

- Everson, William K. A pictorial history of the western film (New York: Citadel Press, 1969)

- Kitses, Jim. Horizons West: The Western from John Ford to Clint Eastwood (British Film Institute, 2007).

- Lenihan, John H. Showdown: Confronting Modern America in the Western Film (University of Illinois Press, 1980)

- Nachbar, John G. Focus on the Western (Prentice Hall, 1974)

- Simmon, Scott. The Invention of the Western Film: A Cultural History of the Genre's First Half Century (Cambridge University Press, 2003)

External links

- Most Popular Westerns at Internet Movie Database

- Western Writers of America website

- The Western[dead link], St. James Encyclopedia of Pop Culture, 2002

- I Watch Westerns, Ludwig von Mises Institute