Propofol

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | Intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | NA |

| Protein binding | 95 to 99% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic glucuronidation |

| Elimination half-life | 30 to 60 min |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.016.551 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

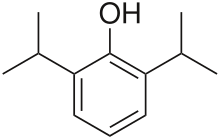

| Formula | C12H18O |

| Molar mass | 178.271 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Propofol (INN, marketed as Diprivan by AstraZeneca) is a short-acting, intravenously administered hypnotic agent. Its uses include the induction and maintenance of general anesthesia, sedation for mechanically ventilated adults, and procedural sedation. Propofol is also commonly used in veterinary medicine. Propofol is approved for use in more than 50 countries, and generic versions are available.

Chemically, propofol is unrelated to barbiturates and has largely replaced sodium thiopental (Pentothal) for induction of anesthesia because recovery from propofol is more rapid and "clear" when compared with thiopental. Propofol is not considered an analgesic, so opioids such as fentanyl may be combined with propofol to alleviate pain.[1] Propofol has been referred to as "milk of amnesia" (a pun on milk of magnesia), because of the milk-like appearance of its intravenous preparation.[2]

Indications

Propofol is used for induction and maintenance of anesthesia [3], having largely replaced sodium thiopental for this indication.[1] Propofol is also used to sedate individuals who are receiving mechanical ventilation. In critically ill patients it has been found to be superior to lorazepam both in effectiveness as well as overall cost; as a result, the use of propofol for this indication is now encouraged whereas the use of lorazepam for this indication is discouraged.[4] Propofol is also used for sedation, for example, prior to endoscopic procedures, and has been found to have less prolonged sedation and a faster recovery time compared to midazolam.[5]

Chemistry

Propofol was originally developed in the UK by Imperial Chemical Industries as ICI 35868. Clinical trials followed in 1977, using a form solubilised in cremophor EL. However, due to anaphylactic reactions to cremophor, this formulation was withdrawn from the market and subsequently reformulated as an emulsion of a soya oil/propofol mixture in water. The emulsified formulation was relaunched in 1986 by ICI (now AstraZeneca) under the brand name Diprivan (abbreviated version of diisopropyl intravenous anesthetic). The currently available preparation is 1% propofol, 10% soybean oil, and 1.2% purified egg phospholipid (emulsifier), with 2.25% of glycerol as a tonicity-adjusting agent, and sodium hydroxide to adjust the pH. Diprivan contains EDTA, a common chelation agent, that also acts alone (bacteriostatically against some bacteria) and synergistically with some other antimicrobial agents. Newer generic formulations contain sodium metabisulfite or benzyl alcohol as antimicrobial agents. Propofol emulsion is a highly opaque white fluid due to the scattering of light from the tiny (~150 nm) oil droplets that it contains.

A water-soluble prodrug form, fospropofol, has recently been developed and tested with positive results. Fospropofol is rapidly broken down by the enzyme alkaline phosphatase to form propofol. Marketed as Lusedra, this new formulation may not produce the pain at injection site that often occurs with the traditional form of the drug. The US Food and Drug Administration approved the product in 2008.[6]

Mechanism of action

Propofol has been proposed to have several mechanisms of action,[7][8][9] both through potentiation of GABAA receptor activity, thereby slowing the channel-closing time,[10][11][12] and also acting as a sodium channel blocker.[13][14] Recent research has also suggested that the endocannabinoid system may contribute significantly to propofol's anesthetic action and to its unique properties.[15]

Pharmacokinetics

Propofol is highly protein-bound in vivo and is metabolised by conjugation in the liver.[16] Its rate of clearance exceeds hepatic blood flow, suggesting an extrahepatic site of elimination as well. The half life of elimination of propofol has been estimated at between 2 and 24 hours. However, its duration of clinical effect is much shorter, because propofol is rapidly distributed into peripheral tissues. When used for IV sedation, a single dose of propofol typically wears off within minutes. Propofol is versatile; the drug can be given for short or prolonged sedation as well as for general anesthesia. Its use is not associated with nausea as is often seen with opioid medications. These characteristics of rapid onset and recovery along with its amnestic effects[17] have led to its widespread use for sedation and anesthesia.

EEG research upon those undergoing general anesthesia with propofol finds that it causes a prominent reduction in the brain's information integration capacity at gamma wave band frequencies.[18]

Contraindications and interactions

The respiratory effects of propofol are potentiated by other respiratory depressants, including benzodiazepines.[19]

As with any other general anesthetic agent, propofol should be administered only where appropriately trained staff and facilities for monitoring are available, as well as proper airway management, a supply of supplemental oxygen, artificial ventilation and cardiovascular resuscitation.[20]

Adverse effects

Aside from low blood pressure (mainly through vasodilation) and transient apnea following induction doses, one of propofol's most frequent side effects is pain on injection, especially in smaller veins. This pain can be mitigated by pretreatment with lidocaine.[21] Patients show great variability in their response to propofol, at times showing profound sedation with small doses. A more serious but rare side effect is dystonia.[22] Mild myoclonic movements are common, as with other intravenous hypnotic agents. Propofol appears to be safe for use in porphyria, and has not been known to trigger malignant hyperpyrexia.

It has been reported that the euphoria caused by propofol is unlike that caused by other sedation agents, "I even remember my first experience using propofol: a young woman who was emerging from a MAC anesthesia[23] looked at me as though I were a masked Brad Pitt and told me that she felt simply wonderful." —C.F. Ward, M.D.[24]

Propofol has reportedly induced priapism in some individuals.[25][26]

Propofol infusion syndrome

Another recently described rare, but serious, side effect is propofol infusion syndrome. This potentially lethal metabolic derangement has been reported in critically ill patients after a prolonged infusion of high-dose substance in combination with catecholamines and/or corticosteroids.[27]

Nonmedical use

There are reports of self-administration of propofol for recreational purposes.[28][29] Short-term effects include mild euphoria, hallucinations, and disinhibition.[30][31] Long-term use has been reported to result in addiction.[32][33] Such use of the drug has been described amongst medical staff, such as anaesthetists who have access to the drug.[32] Misuse is reported to be more common among anaesthetists on rotations with short rest periods, as recreational users report rousing to a well-rested state.[34] Recreational use of the drug is relatively rare due to its potency and the level of monitoring required to take it safely. Propofol has not yet been scheduled by the US Drug Enforcement Administration.[34][35] The steep dose-response curve of the drug makes potential misuse very dangerous without proper monitoring, and at least three deaths from self-administration have been recorded.[36][37]

Attention to the risks of nonmedical use of propofol increased in August 2009 due to the Los Angeles County coroner's conclusion that Michael Jackson died from a mixture of propofol and the benzodiazepine drugs lorazepam on top of diazepam ingested earlier.[38][39][40][41] According to a July 22, 2009, search warrant affidavit unsealed by the district court of Harris County, Texas, Jackson's personal physician administered 25 milligrams of propofol diluted with lidocaine shortly before Jackson's death.[39][40][42]

Supply issues

On June 4, 2010 Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd., an Israel-based pharmaceutical firm, and major supplier of the drug, announced that they would no longer manufacture it. This aggravates an already existing shortage, caused by manufacturing difficulties at Teva and Hospira. (AstraZeneca has not made propofol in some time.) A Teva spokesperson attributed the halt to ongoing process difficulties, and a number of pending lawsuits related to the drug.[43]

References

- ^ a b Miner JR, Burton JH. Clinical practice advisory: Emergency department procedural sedation with propofol. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2007 Aug;50(2):182–7, 187.e1. Epub 2007 Feb 23.

- ^ Euliano TY, Gravenstein JS (2004). "A brief pharmacology related to anesthesia". Essential anesthesia: from science to practice. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 173. ISBN 0-521-53600-6.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Diprivan (Propofol) Dosing Calculator

- ^ Cox, CE.; Reed, SD.; Govert, JA.; Rodgers, JE.; Campbell-Bright, S.; Kress, JP.; Carson, SS. (2008). "Economic evaluation of propofol and lorazepam for critically ill patients undergoing mechanical ventilation". Crit Care Med. 36 (3): 706–14. doi:10.1097/CCM.0B013E3181544248. PMC 2763279. PMID 18176312.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ McQuaid, KR.; Laine, L. (2008). "A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials of moderate sedation for routine endoscopic procedures". Gastrointest Endosc. 67 (6): 910–23. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2007.12.046. PMID 18440381.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/index.cfm?fuseaction=Search.DrugDetails".

- ^ Trapani G, Altomare C, Liso G, Sanna E, Biggio G. Propofol in anesthesia. Mechanism of action, structure-activity relationships, and drug delivery. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2000 Feb;7(2):249-71. PMID 10637364

- ^ Kotani Y, Shimazawa M, Yoshimura S, Iwama T, Hara H. The experimental and clinical pharmacology of propofol, an anesthetic agent with neuroprotective properties. CNS Neuroscience and Therapeutics. 2008 Summer;14(2):95–106. PMID 18482023

- ^ Vanlersberghe C, Camu F. Propofol. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. 2008;(182):227-52. PMID 18175094

- ^ Trapani G, Latrofa A, Franco M, Altomare C, Sanna E, Usala M, Biggio G, Liso G. Propofol analogues. Synthesis, relationships between structure and affinity at GABAA receptor in rat brain, and differential electrophysiological profile at recombinant human GABAA receptors. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 1998 May 21;41(11):1846–54. doi:10.1021/jm970681h PMID 9599235

- ^ Krasowski MD, Jenkins A, Flood P, Kung AY, Hopfinger AJ, Harrison NL. General anesthetic potencies of a series of propofol analogs correlate with potency for potentiation of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) current at the GABA(A) receptor but not with lipid solubility. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2001 Apr;297(1):338-51. PMID 11259561

- ^ Krasowski MD, Hong X, Hopfinger AJ, Harrison NL. 4D-QSAR analysis of a set of propofol analogues: mapping binding sites for an anesthetic phenol on the GABA(A) receptor. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2002 Jul 18;45(15):3210–21. doi:10.1021/jm010461a PMID 12109905

- ^ Haeseler G, Leuwer M. High-affinity block of voltage-operated rat IIA neuronal sodium channels by 2,6 di-tert-butylphenol, a propofol analogue. European Journal of Anaesthesiology. 2003 Mar;20(3):220-4. PMID 12650493

- ^ Haeseler G, Karst M, Foadi N, Gudehus S, Roeder A, Hecker H, Dengler R, Leuwer M. High-affinity blockade of voltage-operated skeletal muscle and neuronal sodium channels by halogenated propofol analogues. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2008 Sep;155(2):265-75. doi:10.1038/bjp.2008.255 PMID 18574460

- ^ Fowler, CJ. "Possible involvement of the endocannabinoid system in the actions of three clinically used drugs." Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2004 Feb;25(2):59–61.

- ^ Favetta P, Degoute C-S, Perdrix J-P, Dufresne C, Boulieu R, and Guitton J (2002). Propofol metabolites in man following propofol induction and maintenance. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 88, 653–8.

- ^ Veselis RA, Reinsel RA, Feshchenko VA, & Wroński M. The comparative amnestic effects of midazolam, propofol, thiopental, and fentanyl at equisedative concentrations. Anesthesiology. 1997 Oct;87(4):749-64. PMID 9357875

- ^ Lee U, Mashour GA, Kim S, Noh GJ, Choi BM. (2009). Propofol induction reduces the capacity for neural information integration: implications for the mechanism of consciousness and general anesthesia. Conscious Cogn. 18(1):56-64. PMID 19054696 doi:10.1016/j.concog.2008.10.005

- ^ Doheny, Kathleen (2009-08-24). "Propofol Linked to Michael Jackson's Death". WebMD. Retrieved 2009-08-26.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ http://www1.astrazeneca-us.com/pi/diprivan.pdf

- ^ "Propofol Drug Information, Professional". drugs.com. Retrieved 2007-01-02.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ Schramm BM, Orser BA (2002). Dystonic reaction to propofol attenuated by benztropine (Cogentin). Anesth Analg, 94, 1237-40.

- ^ MAC anesthesia: Monitored anesthesia care

- ^ http://www.csahq.org/pdf/bulletin/propofol_57_2.pdf

- ^ Vesta, Kimi (2009-04-25). "Propofol-Induced Priapism, a Case Confirmed with Rechallenge". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 40 (5): 980–982. doi:10.1345/aph.1G555. PMID 16638914.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|unused_data=ignored (help) - ^ Fuentesa, Ennio (July 2009). "Successful treatment of propofol-induced priapism with distal glans to corporal cavernosal shunt". Urology. 74 (1): 113–115. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2008.12.066. PMID 19371930.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|unused_data=ignored (help) - ^ Vasile B, Rasulo F, Candiani A, Latronico N (2003). "The pathophysiology of propofol infusion syndrome: a simple name for a complex syndrome". Intensive care medicine. 29 (9): 1417–25. doi:10.1007/s00134-003-1905-x. PMID 12904852.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Riezzo I, Centini F, Neri M, Rossi G, Spanoudaki E, Turillazzi E, Fineschi V (2009). "Brugada-like EKG pattern and myocardial effects in a chronic propofol abuser". Clin Toxicol (Phila). 47 (4): 358–63. doi:10.1080/15563650902887842. PMID 19514884.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Belluck, Pam (2009-08-06). "With High-Profile Death, Focus on High-Risk Drug". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- ^ In Sweetman SC (Ed.). Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference 2005. 34th Edn London pp. 1305–7

- ^ Baudoin Z. General anaesthetics and anaesthetic gases. In Dukes MNG and Aronson JK (Eds.). Meyler's Side Effects of Drugs 2000. 14th Edn Amsterdam pp. 330

- ^ a b Roussin A, Montastruc JL, Lapeyre-Mestre M (October 21, 2007). "Pharmacological and clinical evidences on the potential for abuse and dependence of propofol: a review of the literature". Fundamental and Clinical Pharmacology. 21 (5): 459–66. doi:10.1111/j.1472-8206.2007.00497.x. PMID 17868199.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bonnet U, Harkener J, Scherbaum N (2008). "A case report of propofol dependence in a physician". J Psychoactive Drugs. 40 (2): 215–7. PMID 18720673.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Charatan F (2009). "Concerns mount over misuse of propofol among US healthcare professionals". BMJ. 339: b3673. doi:10.1136/bmj.b3673. PMID 19737827.

- ^ DEA may limit drug eyed in Jackson case. Associated Press. 15 July 2009.

- ^ Iwersen-Bergmann S, Rösner P, Kühnau HC, Junge M, Schmoldt A (2001). "Death after excessive propofol abuse". International Journal of Legal Medicine. 114 (4–5): 248–51. doi:10.1007/s004149900129. PMID 11355404.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kranioti EF, Mavroforou A, Mylonakis P, Michalodimitrakis M. (March 22, 2007). "Lethal self administration of propofol (Diprivan): A case report and review of the literature". Forensic Science International. 167 (1): 56–8. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2005.12.027. PMID 16431058.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

{{cite news}}: Empty citation (help) - ^ a b Surdin, Ashley (2009-08-25). "Coroner Attributes Michael Jackson's Death to Propofol". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- ^ a b Itzkoff, Dave (2009-08-24). "Coroner's Findings in Jackson Death Revealed". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- ^ "Jackson's Death: How Dangerous Is Propofol?". Time. 2009-08-25. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- ^ http://www.scribd.com/doc/19058649/Michael-Jackson-search-warrant.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Teva won't make more of powerful sedative".

External links

- Diprivan web site run by AstraZeneca

- Detailed pharmaceutical information

- U.S. National Library of Medicine: Drug Information Portal - Propofol

| Links to related articles |

|---|