Judaeo-Spanish

| Judaeo-Spanish | |

|---|---|

| Ladino | |

| |

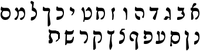

The Rashi script, originally used to write the language | |

| Pronunciation | [dʒuˈðeo espaˈɲol][note 1] |

| Native to | Israel, Turkey, US, France, Spain, Greece, Brazil, UK, Morocco, Bulgaria, Italy, Canada, Mexico, Argentina, Uruguay, Serbia, Bosnia Herzegovina, Macedonia, Tunisia, Belgium, South Africa, Austria and others |

| Ethnicity | Sephardic Jews and Sabbateans |

Native speakers | (112,130 in Israel cited 1985)[1] 10,000 in Turkey (2007) |

Indo-European

| |

| Dialects | Eastern/Oriental; Western/Occidental; Haketia |

| mainly Latin alphabet; (originally Rashi and Solitreo) also Hebrew and Cyrillic and rarely Greek and Arabic | |

| Official status | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | none |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | lad |

| ISO 639-3 | lad |

lad | |

| Glottolog | ladi1251 |

| ELP | Ladino |

| Linguasphere | ... 51-AAB-bd 51-AAB-ba ... 51-AAB-bd |

| |

Judaeo-Spanish (also Judeo-Spanish and Judæo-Spanish: [Judeo-Español] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), Hebrew script: גֿודֿיאו-איספאנייול, Cyrillic: Джудео-Еспањол), commonly referred to as Ladino, is a Romance language derived from Old Spanish. Originally spoken in the former territories of the Ottoman Empire (the Balkans, Turkey, the Middle East, and North Africa) as well as in France, Italy, Netherlands, Morocco, and the UK, today it is spoken mainly by Sephardic minorities in more than 30 countries, most of the speakers residing in Israel. Although it has no official status in any country, it has been acknowledged as a minority language in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Israel, France and Turkey.

The core vocabulary of Judaeo-Spanish is Old Spanish and it has numerous elements from all the old Romance languages of the Iberian Peninsula: Old Aragonese, Astur-Leonese, Old Catalan, Old Portuguese and Mozarabic.[2] The language has been further enriched by Ottoman Turkish and Semitic vocabulary, such as Hebrew, Aramaic, and Arabic, especially in the domains of religion, law and spirituality and most of the vocabulary for new and modern concepts has been adopted through French and Italian. Furthermore, the language is influenced to a lesser degree by other local languages of the Balkans, such as Greek, Bulgarian and Serbo-Croatian.

Historically, the Rashi script and its cursive form Solitreo have been the main orthographies for writing Judaeo-Spanish. However today, it is mainly written with the Latin alphabet, though some other alphabets such as Hebrew and Cyrillic are still in use. Judaeo-Spanish is known by many different names, mostly: Español/Espanyol, Judió/Djudyo (or Jidió/Djidyo), Judesmo/Djudezmo, Sefaradhí/Sefaradi and Ḥaketilla/Haketia. In Turkey and formerly in the Ottoman Empire, it has been traditionally called Yahudice in Turkish, meaning the Jewish language. Moreover in Israel, Hebrew speakers usually calls the language as (E)spanyolit or Ladino.

Judaeo-Spanish, once the trade language of the Adriatic Sea, the Balkans and the Middle-East and renowned for its rich literature especially in Salonika, today is under serious threat of extinction. Most native speakers are elderly and the language is not transmitted to their children or grandchildren for various reasons. In some expatriate communities in Latin America and elsewhere, there is a threat of dialect levelling resulting in extinction by assimilation into modern Spanish. However, it is experiencing a minor revival among Sephardic communities, especially in music.

Name

In Israel particularly, and in America and Spain, in recent decades the language came to be referred to as Ladino (לאדינו) (literally meaning "Latin"), though some people who actually speak the language consider this use incorrect.[3] The language is also called judeo-espagnol,[note 2] judeo-español,[4] Sefardí, Judío, and Espanyol or Español sefardita; Haquetía (from the Arabic ħaka حكى, "tell") refers to the dialect of North Africa, especially Morocco. The dialect of the Oran area of Algeria was called Tetuani, after the Moroccan town Tétouan, since many Orani Jews came from this city. In Hebrew, the language is called Spanyolit.

An entry in Ethnologue claims, "The name 'Judesmo' is used by Jewish linguists and Turkish Jews and American Jews; 'Judeo-Spanish' by Romance philologists; 'Ladino' by laymen, especially in Israel; 'Haketia' by Moroccan Jews; 'Spanyol' by some others."[5] This information does not reflect the historical usage. In the Judeo-Spanish press of the 19th and 20th centuries the native authors referred to the language exclusively as Espanyol, which was also the name that its native speakers spontaneously gave to it for as long as it was their primary spoken language: more rarely, the bookish Judeo-Espanyol has also been used since the late nineteenth century.[6] The name Judezmo is unknown and offensive to most native speakers, and it has never been used in print in the native press (although in limited parts of Macedonia its use in the past as a low-register designation in informal speech by unschooled people has been documented).

The derivation of the name Ladino is complicated. In pre-Expulsion times in the area known today as Spain the word meant literary Spanish as opposed to other dialects, [citation needed] or Romance in general as distinct from Arabic.[7] (The first European language grammar and dictionary, of Spanish, refers to it as ladino or ladina. In the Middle Ages, the word Latin was frequently used to mean simply "language", and in particular the language one understands: a latiner or latimer meant a translator.) Following the expulsion, Jews spoke of "the Ladino" to mean the traditional oral translation of the Bible into archaic Spanish. By extension it came to mean that style of Spanish generally, in the same way that (among Kurdish Jews) Targum has come to mean Judeo-Aramaic and (among Jews of Arabic-speaking background) sharħ has come to mean Judeo-Arabic.[8]

Informally, and especially in modern Israel, many speakers use Ladino to mean Judaeo-Spanish as a whole. The language was formerly regulated by a body called the Autoridad Nasionala del Ladino in Israel. More strictly, however, the term is confined to the style used in translation. According to the website of the Jewish Museum of Thessaloniki,

Ladino is not spoken, rather, it is the product of a word-for-word translation of Hebrew or Aramaic biblical or liturgical texts made by rabbis in the Jewish schools of Spain. In these, translations, a specific Hebrew or Aramaic word always corresponded to the same Spanish word, as long as no exegetical considerations prevented this. In short, Ladino is only Hebrew clothed in Spanish, or Spanish with Hebrew syntax. The famous Ladino translation of the Bible, the Biblia de Ferrara (1553), provided inspiration for the translation of numerous Spanish Christian Bibles."[3]

This Judaeo-Spanish ladino should not be confused with the ladino or Ladin language spoken in part of North-Eastern Italy, which is closely related with the rumantsch-ladin of Swiss Grisons (it is disputed whether or not they form a common Rhaeto-Romance language) and has nothing to do with either Jews or Spanish beyond being, like Spanish, a Romance language, a property they share with French, Italian, Portuguese and Romanian.

In modern Spanish per the Royal Spanish Academy, "Ladino" has nine meanings, including five as an adjective and four as a noun, two of which meanings are obsolete:

1. Adj. Astute, sagacious, cunning

2. Adj. Pertaining or relating to the Ladin language.

3. Adj. In El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Panama, describing a mestizo person who speaks only Spanish.

4. Adj. In El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Panama, a Mestizo person.

5. Adj. Obsolete: A person with facility in languages other than his/her own.

6. Noun. The Ladin language spoken in South Tyrol.

7. Noun. The religious language of Sephardic Jews.

8. Noun. Judeo-Spanish.

9. Noun. Obsolete: The archaic literary form of Spanish called "romance" or "romantic Spanish."[9]

Variants

At the time of the expulsion from Spain, the day-to-day language of the Jews of different regions of the peninsula was little if at all different from that of their Christian neighbors, though there may have been some dialect mixing to form a sort of Jewish lingua franca. There was however a special style of Spanish used for purposes of study or translation, featuring a more archaic dialect, a large number of Hebrew and Aramaic loan-words and a tendency to render Hebrew word order literally (e.g.: ha-laylah ha-zeh, meaning "this night", was rendered la noche la esta instead of the normal Spanish esta noche[10]). As mentioned above, some authorities would confine the term "Ladino" to this style.

Following the expulsion, the process of dialect mixing continued, though Castilian Spanish remained by far the largest contributor. The daily language was increasingly influenced both by the language of study and by the local non-Jewish vernaculars such as Greek and Turkish, and came to be known as Judesmo: in this respect the development is parallel to that of Yiddish. However, many speakers, especially among the community leaders, also had command of a more formal style nearer to the Spanish of the expulsion, referred to as Castellano.

Sources

Spanish

The grammar, phonology and about 60% of the vocabulary of Judaeo-Spanish are basically Spanish, but, in some respects, it resembles the dialects in southern Spain and South America rather than the dialects of Central Spain. For example, it exhibits both yeísmo ("she" is eya/ella [ˈeja] (Judaeo-Spanish), instead of ella, and seseo.

In many respects, it reproduces the Spanish of the time of the expulsion rather the modern variety, as it retains some archaic features such as these:

- Modern Spanish j, pronounced [x], corresponds to two different phonemes in Old Spanish: x, pronounced /ʃ/, and j, pronounced /ʒ/. Judaeo-Spanish retains the original sounds. Similarly, g before e or i remains /ʒ/, not [x].

- Contrast baṣo/baxo ("low" or "down", with /ʃ/, modern Spanish bajo) and mujer ("woman" or "wife", spelled the same, with /ʒ/).

- Modern Spanish z (c before e or i), pronounced [s] or [θ] (as the English "th" in "think") according to the dialect, corresponds to two different phonemes in Old Spanish: ç (c before e or i), pronounced "ts"; and z (in all positions), pronounced "dz". In Judaeo-Spanish, they are pronounced [s] and [z] respectively.

- Contrast korasón/coraçón ("heart", with /s/, modern Spanish corazón) and dezir ("to say", with /z/, modern Spanish decir).

- In modern Spanish, the use of the letters b and v is determined partly on the basis of earlier forms of the language and partially on the basis of Latin etymology: both letters represent one phoneme (/b/), realised as [b] or as [β] according to its position. In Old Spanish and Judeo-Spanish, the choice is made phonetically: bivir [biˈviɾ], "to live" (modern Spanish vivir). In Judaeo-Spanish, v is a labiodental "v" (like in English) rather than a bilabial.

Portuguese and other Iberian languages

However, the phonology of both the consonants and part of the lexicon is, in some respects, closer to Galician-Portuguese or Catalan than to modern Spanish. That is explained not only by direct influence but because all three languages retained some of the characteristics of medieval Ibero-Romance that Castilian Spanish later lost.

Contrast Judaeo-Spanish Template:Wiktlad ("still") with Portuguese Template:Wiktpt (Galician Template:Wiktgl, Asturian Template:Wiktast or Template:Wiktast) and Spanish Template:Wiktes or the initial consonants in Judaeo-Spanish Template:Wiktlad, Template:Wiktlad ("daughter", "speech"), Portuguese Template:Wiktpt, Template:Wiktpt (Galician Template:Wiktgl, Template:Wiktgl, Asturian Template:Wiktast, Template:Wiktast, Aragonese Template:Wiktan, Template:Wiktan, Catalan Template:Wiktcat), Spanish Template:Wiktes, Template:Wiktes. It sometimes varied with dialect, as in Judaeo-Spanish popular songs, both Template:Wiktlad and Template:Wiktlad ("son") are found.

The Judaeo-Spanish pronunciation of s as "[ʃ]" before a "k" sound or at the end of certain words (such as Template:Wiktlad, pronounced [seʃ], for six) is shared with Portuguese (as spoken in Portugal, most of Asia and Africa, and in a plurality of Brazilian registers with either partial or total forms of coda |S| palatalization) but not with Spanish.

Hebrew and Aramaic

Like other Jewish vernaculars, Judaeo-Spanish incorporates many Hebrew and Aramaic words, mostly for religious concepts and institutions. Examples are Haham (rabbi) and kal/cal (synagogue, from Hebrew qahal).

Other languages

Judaeo-Spanish has absorbed some words from the local languages but sometimes Hispanicised their form: bilbilico (nightingale), from Persian (via Turkish) bülbül. It may be compared to the Slavic elements in Yiddish. It is not always clear whether some of these words antedate the expulsion because of the large number of Arabic words in Spanish generally.

Phonology

Judaeo-Spanish phonology consists of 28 phonemes: 23 consonants and 5 vowels.

Consonants

| Bilabial | Labio- dental |

Dental | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | (ŋ) | |||

| Stop | p b | t d | k g | ||||

| Affricate | t͡ʃ d͡ʒ | ||||||

| Fricative | (β) | f v | (ð) | s z | ʃ ʒ | x (ɣ) | |

| Trill | r | ||||||

| Tap | ɾ | ||||||

| Approximant | l | j | w |

Vowels

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u |

| Close-mid | e | o |

| Open-mid | (ɛ) | (ɔ) |

| Open | a | |

As exemplified in the Sources section above, much of the phonology of Judaeo-Spanish is similar to that of standard modern Spanish, with certain exceptions. Additional exceptions include:

- Unlike all other non-creole varieties of Spanish, Judaeo-Spanish does not contrast the trill /r/ and the flap /ɾ/.[12]

- The Spanish /nue-/ is /mue-/ in Judaeo-Spanish: nuevo, nuestro → muevo, muestro.[12]

- The Judaeo-Spanish phoneme inventory includes separate [d͡ʒ] and [ʒ]: /ʒuɾnál/ ('newspaper') vs /d͡ʒugár/ ('to play'). Neither are used in Spanish, and were likely added through Turkish loan words. [12]

Morphology

Judaeo-Spanish is distinguished from other Spanish dialects by the presence of the following features:

- With regard to pronouns, Judaeo-Spanish maintains the second-person pronouns as tú (informal singular), vos (formal singular), and vosotros (plural); the third-person el/eya/eyos/eyas are also used in the formal register.[12] The Spanish pronouns usted and ustedes do not exist.

- In verbs, the preterite indicates that an action taken once in the past was also completed at some point in the past. That is as opposed to the imperfect, which refers to any continuous, habitual, unfinished or repetitive past action. Thus, "I ate falafel yesterday" would use the first-person preterite form of eat, komí/comí whereas "When I lived in Izmir, I ran five miles every evening" would use the first-person imperfect form, koría/corría. Though some of the morphology has changed, usage is just as in normative Spanish.

- In general, Judaeo-Spanish uses the Spanish plural morpheme /-(e)s/. The Hebrew plural endings /-im/ and /-ot/ are used with Hebrew load words, as well as with a few words from Spanish: ladrón (thief): ladrones/ladroním; ermano (brother): ermanos/ermaním. [13]Similarly, some loaned feminine nouns ending in -á can take either the Spanish or Hebrew plural: keilá (synagogue): keilás/keilot.

- Judaeo-Spanish contains more gendering cases than standard Spanish, prominently in adjectives, eg. grande/-a, inferior/-ra, as well as in nouns, eg. vozas, fuentas, and in the interrogative kualo/kuala. [12]

Regular conjugation in the present:

| -er verbs (comer: "to eat") |

-ir verbs (bivir: "to live") |

-ar verbs (favlar: "to speak") | |

|---|---|---|---|

| yo | -o : como/komo, bivo, favlo | ||

| tú | -es : comes/komes, bives | -as : favlas | |

| el, eya/ella | -e : come/kome, bive | -a : favla | |

| mozotros/nosotros | -emos : comemos/komemos | -imos : bivimos | -amos : favlamos |

| vos, vozotros/vosotros | -éş/éx : coméş/éx; koméş/éx | -íş/íx : bivíş/íx | -áş/áx : favláş/áx |

| eyos/ellos, eyas/ellas | -en : comen/komen, biven | -an : favlan | |

Regular conjugation in the preterite:

| -er verbs (komer) |

-ir verbs (bivir) |

-ar verbs (favlar) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| yo | -í : comí/komí, biví, favlí | ||

| tu | -ites : comites/komites, bivites | -ates : favlates | |

| el, eya/ella | -yó : comiókomió, bivió | -ó : favló | |

| mozotros/nosotros | -imos : comimos/komimos, bivimos, favlimos | ||

| vos, vozotros/vosotros | -iteş/itex : comiteş/itex; komiteş/itex, bivites/itex | -ateş/atex : favlateş/atex | |

| eyos/ellos, eyas/ellas | -ieron : comieron/komieron, bivieron | -aron : favlaron | |

Syntax

Judaeo-Spanish follows Spanish for most of its syntax. (This is not true of the written calque language involving word-for-word translations from Hebrew, which some scholars refer to as Ladino, as described above.) Like Spanish, it generally follows a subject-verb-object word order, has a nominative-accusative alignment, and is considered a fusional or inflected language.

Orthography

The following systems of writing Judaeo-Spanish have been used or proposed.

- Traditionally, especially in Ladino religious texts, Judaeo-Spanish was printed in the Hebrew alphabet (especially in Rashi script), a practice that was very common, possibly almost universal, until the 19th century (and called aljamiado, by analogy with the equivalent use of the Arabic abjad). This occasionally persists today, especially in religious use. Everyday written records of the language used Solitreo, a semi-cursive script similar to Rashi script, shifting to square letter for Hebrew/Aramaic words. Solitreo is clearly different from the Ashkenazi Cursive Hebrew used today in Israel, though that is also related to Rashi script. (A comparative table is provided in that article.) In this script, there is free use of matres lectionis: final -a is written with ה (heh) and ו (waw) can represent /o/ or /u/. Both s (/s/) and x (/ʃ/) are generally written with ש, as ס is generally reserved for c before e or i and ç.

- The Greek alphabet and Cyrillic have been employed in the past,[14] but this is rare or nonexistent nowadays.

- In Turkey, Judaeo-Spanish is most commonly written in the Turkish variant of the Latin alphabet. This may be the most widespread system in use today, as following the decimation of Sephardic communities throughout much of Europe (particularly in Greece and the Balkans) during the Holocaust the greatest proportion of speakers remaining were Turkish Jews. However, the Judaeo-Spanish page of the Turkish Jewish newspaper Şalom now uses the Israeli system.

- The Israeli Autoridad Nasionala del Ladino promotes a phonetic transcription into the Latin alphabet, making no concessions to Spanish orthography, and uses it in its publication Aki Yerushalayim. The songs Non komo muestro Dio and Por una ninya, below, and the text in the sample paragraph, below, are written using this system.

- Works published in Spain usually adopt the standard orthography of modern Spanish, to make them easier for modern Spaniards to read.[15] These editions often use diacritics to show where the Judaeo-Spanish pronunciation differs from modern Spanish.

- Perhaps more conservative and less popular, others including Pablo Carvajal Valdés suggest that Judaeo-Spanish should adopt the orthography used during the time of the Jewish expulsion of 1492 from Spain.

Arguments for and against the 1492 orthography

This article possibly contains original research. (July 2012) |

The Spanish orthography of that time has been standardized and eventually changed by a series of orthographic reforms, the last of which occurred in the 18th century, to become the spelling of modern Spanish. Judaeo-Spanish has retained some of the pronunciation that at the time of reforms had become archaic in standard Spanish. Adopting 15th century Spanish orthography (similar to modern Portuguese orthography) would therefore closely fit the pronunciation of Judaeo-Spanish.

- The old spelling would reflect

- the /s/ (originally /ts/) – c (before e and i) and ç (cedilla), as in caça,

- the /s/ – ss, as in passo, and

- the /ʃ/ – x, as in dixo.

- The letter j would be retained, but only in instances, such as mujer, where the pronunciation is /ʒ/ in Judaeo-Spanish.

- The spelling of /z/ (originally /dz/) as z would be restored in words like fazer and dezir.

- The difference between b and v would be made phonetically, as in Old Spanish, rather than in accordance with the Latin etymology as in modern Spanish. For example, Latin DEBET > post-1800 Spanish debe, would return to its Old Spanish spelling deve.

Some old spellings could be restored for the sake of historical interest, rather than to reflect Judaeo-Spanish phonology:

- The old digraphs ch, ph and th (today c/qu – /k/, f – /f/ and t – /t/ in standard Spanish respectively), formally abolished in 1803, would be used in words like orthographía, theología.

- Latin/Old Spanish q before words like quando, quanto and qual (modern Spanish cuando, cuanto and cual) would also be used.

The supporters of this orthography argue that classical and Golden Age Spanish literature might gain renewed interest, better appreciation and understanding should its orthography be used again.

It remains uncertain how to treat sounds that Old Spanish spelling failed to render phonetically.

- The s between vowels, as in casa, was probably pronounced /z/ in Old Spanish and is certainly so pronounced in Judaeo-Spanish. The same is true of s before m, d and other voiced consonants, as in mesmo or desde. Supporters of Carvajal's proposal are unsure about whether this should be written s as in Old Spanish or z in accordance with pronunciation.

- The distinctive Judaeo-Spanish pronunciation of s as /ʃ/ before a /k/ sound, as in buscar, cosquillas, mascar and pescar, or in is endings as in séis, favláis and sois, is probably derived from Portuguese: it is uncertain whether it occurred in Old Spanish. It is debated whether this should be written s as in Old Spanish or x in accordance with the sound.

- There is some dispute about the Spanish ll combination, which in Judaeo-Spanish (as in most areas of Spain) is pronounced like a y. Following Old Spanish orthography this should be written ll, but it is frequently written y in Ladino to avoid ambiguity and reflect the Hebrew spelling. The conservative option is to follow the etymology: caballero, but Mayorca.[note 3]

- On this system, it is uncertain how loanwords from Hebrew and other languages should be rendered.

Aki Yerushalayim orthography

Aki Yerushalayim, owned by Autoridad Nasionala del Ladino, promotes this orthography:

| Letter | A a | B b | Ch ch | D d | Dj dj | E e | F f | G g | H h | I i | J j | K k | L l | M m | N n | Ny ny | O o | P p | R r | S s | Sh sh | T t | U u | V v | X x | Y y | Z z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPA | [a] | [b~β] | [t͡ʃ] | [d~ð] | [d͡ʒ] | [e] | [f] | [g~ɣ] | [x] | [i~j] | [ʒ] | [k] | [l] | [m] | [n~ŋ] | [ɲ] | [o] | [p] | [r~ɾ] | [s] | [ʃ] | [t] | [u~w] | [v] | [gz] | [j] | [z] |

- A dot is written between s and h (s·h) to represent [sx], to avoid confusion with [ʃ]. For example: es·huenyo [esˈxweɲo] (dream).

- Unlike Spanish, stressed diacritics are not represented.

- Loanwords and foreign names retain their original spelling. So letters which are not in this orthography like q or w would be used only in these types of words.

Hebrew orthography

Judeo-Spanish is traditionally written in a Hebrew-based script, specially in Rashi script. The Hebrew orthography is not regulated, but sounds are generally represented by these letters:

History

Jews in the Middle Ages were instrumental in the development of Spanish into a prestige language. Erudite Jews translated Arabic and Hebrew works – often translated earlier from Greek – into Spanish and Christians translated again into Latin for transmission to Europe.

Until recent times, the language was widely spoken throughout the Balkans, Turkey, the Middle East, and North Africa, having been brought there by Jewish refugees fleeing the area today known as Spain following the expulsion of the Jews in 1492.[16]

The contact among Jews of different regions and languages, including Catalan, Leonese and Portuguese developed a unified dialect differing in some aspects from the Spanish norm that was forming simultaneously in the area known today as Spain, though some of this mixing may have occurred in exile rather than in the peninsula itself. The language was known as Yahudice (Jewish language) in the Ottoman Empire. In the late 18th century, Enderunlu Fazıl (Fazyl bin Tahir Enderuni) wrote in his Zenanname: "Castilians speak the Jewish language but they are not Jews."

The closeness and mutual comprehensibility between Judaeo-Spanish and Spanish favoured trade among Sephardim (often relatives) ranging from the Ottoman Empire to the Netherlands and the conversos of the Iberian Peninsula.

After the expulsion of the Jews, who were of mostly Portuguese descent, from Dutch Brazil in 1654, Jews were one of the influences on the African-Romance creole Papiamento of the Dutch Caribbean islands Aruba, Bonaire and Curaçao.

Over time, a corpus of literature, both liturgical and secular, developed. Early literature was limited to translations from Hebrew. At the end of the 17th century, Hebrew was disappearing as the vehicle for Rabbinic instruction. Thus a literature in the popular tongue (Ladino) appeared in the 18th century, such as Me'am Lo'ez and poetry collections. By the end of the 19th century, Sephardim in the Ottoman Empire studied in schools of the Alliance Israélite Universelle. French became the language for foreign relations (as it did for Maronites), and Judaeo-Spanish drew from French for neologisms. New secular genres appeared: more than 300 journals, history, theatre, biographies.

Given the relative isolation of many communities, a number of regional dialects of Judaeo-Spanish appeared, many with only limited mutual comprehensibility. This is due largely to the adoption of large numbers of loanwords from the surrounding populations, including, depending on the location of the community, from Greek, Turkish, Arabic, and in the Balkans, Slavic languages, especially Bosnian, Bulgarian and Serbo-Croatian. The borrowing in many Judaeo-Spanish dialects is so heavy that up to 30% of these dialects is of non-Spanish origin. Some words also passed from Judaeo-Spanish into neighbouring languages: the word palavra "word" (Vulgar Latin = "parabola"; Greek = "parabole") for example passed into Turkish, Greek, and Romanian[17] with the meaning "bunk, hokum, humbug, bullshit" in Turkish and Romanian and "big talk, boastful talk" in Greek (cf. the English "palaver").

Judaeo-Spanish was the common language of Salonika during the period of Ottoman rule. The city became part of the modern Greek Republic in 1912 and was subsequently renamed Thessaloniki. Despite a major fire, economic oppression by Greek authorities, and mass settlement of Christian refugees, the language remained widely spoken in Salonika until the deportation of 50,000 Salonikan Jews in the Holocaust during the Second World War. According to the 1928 census there were 62,999 native speakers of Ladino in Greece. This figure drops down to 53,094 native speakers in 1940 but 21,094 citizens also cited speaking Ladino "usually".[18]

Judaeo-Spanish was also a language used in Donmeh rites (Dönme in Turkish meaning convert and referring to adepts of Sabbatai Tsevi converted to the Moslem religion in the Ottoman Empire). An example is the recite Sabbatai Tsevi esperamos a ti. Today, the religious practices and ritual use of Judaeo-Spanish seems confined to elderly generations.

The Castilian colonization of Northern Africa favoured the role of polyglot Sephardim who bridged between Spanish colonizers and Arab and Berber speakers.

From the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries, Judaeo-Spanish was the predominant Jewish language in the Holy Land, though the dialect was different in some respects from that spoken in Greece and Turkey. Some Sephardi families have lived in Jerusalem for centuries, and preserve Judaeo-Spanish for cultural and folklore purposes, though they now use Hebrew in everyday life.

An often told Sephardic anecdote from Bosnia-Herzegovina has it that, as a Spanish consulate was opened in Sarajevo between the two world wars, two Sephardic women were passing by and, upon hearing a Catholic priest speaking Spanish, thought that – given his language – he was in fact Jewish![19]

In the twentieth century, the number of speakers declined sharply: entire communities were murdered in the Holocaust, while the remaining speakers, many of whom emigrated to Israel, adopted Hebrew. The governments of the new nation-states encouraged instruction in the official languages. At the same time, Judaeo-Spanish aroused the interest of philologists, since it conserved language and literature that existed prior to the standardisation of Spanish.

Judaeo-Spanish is in serious danger of extinction because many native speakers today are elderly olim (immigrants to Israel), who have not transmitted the language to their children or grandchildren. Nevertheless, it is experiencing a minor revival among Sephardic communities, especially in music. In addition, Sephardic communities in several Latin American countries still use Judaeo-Spanish. In these countries, there is an added danger of extinction by assimilation to modern Spanish.

Kol Yisrael[20] and Radio Nacional de España[21] hold regular radio broadcasts in Judaeo-Spanish. Law & Order: Criminal Intent showed an episode, titled "A Murderer Among Us", with references to the language. Films partially or totally in Judaeo-Spanish include Mexican film Novia que te vea (directed by Guita Schyfter), The House on Chelouche Street, and Every Time We Say Goodbye.

Efforts have been made to gather and publish modern Judaeo-Spanish fables and folktales. In 2001, the Jewish Publication Society published the first English translation of Judaeo-Spanish folk tales, collected by Matilda Koén-Sarano, Folktales of Joha, Jewish Trickster: The Misadventures of the Guileful Sephardic Prankster. A survivor of Auschwitz, Moshe Ha'elyon, issued his translation into Ladino of the ancient Greek epic The Odyssey in 2012, in his 87th year, and is now translating the sister epic, the Iliad, into his mother tongue.[22]

Literature

The earliest Judeo-Spanish books are religious in nature, mostly created to maintain religious knowledge among exiles illiterate in Hebrew; the first known text among these is Dinim de shehitah i bedikah (The Rules of Ritual Slaughter and Inspection of Animals; Istanbul, 1510).[23] Texts continued to be focused on philosophical and religious themes, including a large body of rabbinic writings, through the first half of the nineteenth century. The largest output of secular Judeo-Spanish literature occurred during the latter half of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in the Ottoman Empire. The earliest and most abundant form of secular text was the press: between 1845 and 1939, Ottoman Sephardim published around 300 individual periodical titles.[24] The proliferation of periodicals gave rise to serialized novels, many of which were rewrites of existing foreign novels into Judeo-Spanish. These works, unlike the previous scholarly literature, were intended for a broader audience of educated men and less literate women alike, and thus covered a wider range of less weighty content, at times censored to be appropriate for family readings.[25] The popular literature expanded to include love stories and adventure stories, both of which were previously absent from Judeo-Spanish literary canon.[26] The literary corpus at this time also expanded to include theatrical plays, poems, and other minor genres.

Religious use

The Jewish community of Bosnia-Herzegovina in Sarajevo and the Jewish community of Belgrade still chant part of the Sabbath Prayers (Mizmor David) in Ladino. The Sephardic Synagogue Ezra Bessaroth in Seattle, Washington (US) was formed by Jews from Turkey and the Island of Rhodes, and they use Ladino in some portions of their Shabbat services. The Siddur is called Zehut Yosef and was written by Hazzan Isaac Azose.

At Congregation Etz Ahaim,[27] a Sephardic congregation founded by Jews from Salonika in New Brunswick, New Jersey now located in Highland Park, New Jersey, a reader chants the Aramaic prayer B'rich Shemay in Ladino before taking out the Torah on Shabbat; it is known as Bendichu su Nombre in Ladino. Additionally, at the end of Shabbat services, the entire congregation sings the well-known Hebrew hymn Ein Keloheinu, which is called Non Como Muestro Dio in Ladino.

Non Como Muestro Dio is also included alongside Ein Keloheinu in Mishkan T'filah, the 2007 Reform prayerbook.[28]

The late Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan translated some scholarly religious Ladino texts, including Me'am Loez, into Hebrew or English, or both.[29][30]

Izmir's grand rabbis Haim Palachi, Abraham Palacci, and Rahamim Nissim Palacci all wrote in Ladino as well as Hebrew.

Modern education

As with Yiddish[31][32] the Ladino language is seeing a minor resurgence in educational interest in colleges across the United States and in Israel.[33] Still, given the ethnic demographics among American Jews, it is not surprising that more institutions offer Yiddish language courses than Ladino language courses. Today, the University of Pennsylvania[34][35] and Tufts University[36] offer Ladino language courses among colleges in the United States.[37] In Israel, Moshe David Gaon Center for Ladino Culture at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev is leading the way in education (Ladino language and literature courses, Community oriented activities) and research (a yearly scientific journal, international congresses and conferences etc.). Hebrew University also offers Ladino language courses.[38] The Complutense University of Madrid also has in the past.[39] Prof. David Bunis taught Ladino at the University of Washington, in Seattle during the 2013–14 academic year.[40]

Samples

Comparison with other languages

| Judaeo-Spanish | [El djudeo-espanyol, djudio, djudezmo es la lingua favlada por los djudios sefardim ekspulsados de la Espanya enel 1492. Es una lingua derivada del espanyol i favlada por 150.000 personas en komunitas en Israel, la Turkia, antika Yugoslavia, la Gresia, el Maruekos, Mayorka, las Amerikas, entre munchos otros.] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) |

|---|---|

| Spanish | [El judeo-español, djudio, djudezmo es la lengua hablada por los judíos sefardíes expulsados de España en 1492. Es una lengua derivada del español y hablada por 150.000 personas en comunidades en Israel, Turquía, la antigua Yugoslavia, Grecia, Marruecos, Mallorca, las Américas, entre muchos otros.] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) |

| Catalan | [El judeocastellà, djudiu, djudezmo és la llengua parlada pels jueus sefardites expulsats d'Espanya al 1492. És una llengua derivada de l'espanyol i parlada per 150.000 persones en comunitats a Israel, Turquia, antiga Iugoslàvia, Grècia, el Marroc, Mallorca, les Amèriques, entre moltes altres.] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) |

| Asturian | [El xudeoespañol, djudio, djudezmo ye la llingua falada polos xudíos sefardinos expulsados d'España en 1492. Ye una llingua derivada del español y falada por 150.000 persones en comunidaes n'Israel, Turquía, na antigua Yugoslavia, Grecia, Marruecos, Mayorca, nes Amériques, entre munchos otros.] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) |

| Galician | [O xudeo-español, djudio, djudezmo é a lingua falada polos xudeos sefardís expulsados de España en 1492. É unha lingua derivada do español e falada por 150.000 persoas en comunidades en Israel, en Turquía, na antiga Iugoslavia, Grecia, Marrocos, Maiorca, nas Américas, entre moitos outros [lugares].] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) |

| Portuguese | [O judeo-espanhol, djudio, djudezmo é a língua falada pelos judeus sefarditas expulsos de/da Espanha em 1492. É uma língua derivada do espanhol e falada por 150.000 pessoas em comunidades em Israel, na Turquia, na antiga Jugoslávia, na Grécia, em/no Marrocos, em Maiorca (ou Mayorca/Malhorca), nas Américas, entre muitos outros [lugares].] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) |

| English | Judeo-Spanish, Djudio, Judezmo, is the language spoken by Sephardi Jews expelled from Spain in 1492. It is a language derived from Spanish and spoken by 150,000 people in communities in Israel, Turkey, the former Yugoslavia, Greece, Morocco, Majorca, the Americas, among many others [places]. |

Songs

Folklorists have been collecting romances and other folk songs, some dating from before the expulsion. Many religious songs in Judeo-Spanish are translations of the Hebrew, usually with a different tune. For example, Ein Keloheinu looks like this in Judeo-Spanish:

- Non komo muestro Dio,

- Non komo muestro Sinyor,

- Non komo muestro Rey,

- Non komo muestro Salvador.

- etc.

Other songs relate to secular themes such as love.

| Adio, kerida | |

|---|---|

| Tu madre kuando te pario Y te kito al mundo, Adio, |

Va, bushkate otro amor, Aharva otras puertas, Adio, |

| Por una Ninya | For a Girl (translation) |

| Por una ninya tan fermoza l'alma yo la vo a dar un kuchilyo de dos kortes en el korason entro. |

For a girl so beautiful I will give my soul a double-edged knife pierced my heart. |

| No me mires ke'stó kantando es lyorar ke kero yo los mis males son muy grandes no los puedo somportar. |

Don't look at me; I am singing, it is crying that I want, my sorrows are so great I can't bear them. |

| No te lo kontengas tu, fijika, ke sos blanka komo'l simit, ay morenas en el mundo ke kemaron Selanik. |

Don't hold your sorrows, young girl, for you are white like bread, there are dark girls in the world who set fire to Thessaloniki. |

| Quando el Rey Nimrod (Adaptation) | When King Nimrod (translation) |

| Quando el Rey Nimrod al campo salía mirava en el cielo y en la estrellería vido una luz santa en la djudería que havía de nascer Avraham Avinu. |

When King Nimrod was going out to the fields He was looking at heaven and at the stars He saw a holy light in the Jewish quarter [A sign] that Abraham, our father, must have been born. |

| Avraham Avinu, Padre querido, Padre bendicho, luz de Yisrael. |

Abraham Avinu [our Father], dear father Blessed Father, light of Israel. |

| Luego a las comadres encomendava que toda mujer que prenyada quedara si no pariera al punto, la matara que havía de nascer Abraham Avinu. |

Then he was telling all the midwives That every pregnant woman Who did not give birth at once was going to be killed because Abraham our father was going to born. |

| Avraham Avinu, Padre querido, Padre bendicho, luz de Yisrael. |

Abraham Avinu, dear father Blessed Father, light of Israel. |

| La mujer de Terach quedó prenyada y de día en día le preguntava ¿De qué teneix la cara tan demudada? ella ya sabía el bien que tenía. |

Terach's wife was pregnant and each day he would ask her Why do you look so distraught? She already knew very well what she had. |

| Avraham Avinu, Padre querido, Padre bendicho, luz de Yisrael. |

Abraham Avinu, dear father Blessed Father, light of Israel. |

| En fin de nueve meses parir quería iva caminando por campos y vinyas, a su marido tal ni le descubría topó una meara, allí lo pariría |

After nine months she wanted to give birth She was walking through the fields and vineyards Such would not even reach her husband She found a manger; there, she would give birth. |

| Avraham Avinu, Padre querido, Padre bendicho, luz de Yisrael. |

Abraham Avinu, dear father Blessed Father, light of Israel. |

| En aquella hora el nascido avlava "Andavos mi madre, de la meara yo ya topó quen me alexara mandará del cielo quen me accompanyará porque so criado del Dio bendicho." |

In that hour the newborn was speaking 'Get away of the manger, my mother I will somebody to take me out He will send from the heaven the one that will go with me Because I am a servant of the blessed God.' |

| Avraham Avinu, Padre querido, Padre bendicho, luz de Yisrael |

Abraham Avinu, dear father Blessed Father, light of Israel. |

Anachronistically, Abraham – who in the Bible is the very first Hebrew and the ancestor of all who followed, hence his appellation "Avinu" (Our Father) – is in the Judeo-Spanish song born already in the "djudería" (modern Spanish: judería), the Jewish quarter. This makes Terach and his wife into Hebrews, as are the parents of other babies killed by Nimrod. In essence, unlike its Biblical model, the song is about a Hebrew community persecuted by a cruel king and witnessing the birth of a miraculous saviour – a subject of obvious interest and attraction to the Jewish people who composed and sang it in Medieval Spain.

The song attributes to Abraham elements from the story of Moses's birth (the cruel king killing innocent babies, with the midwives ordered to kill them, the 'holy light' in the Jewish area) and from the careers of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego who emerged unscathed from the fiery furnace. Nimrod is thus made to conflate the role and attributes of two archetypal cruel and persecuting kings – Nebuchadnezzar and Pharaoh. For more information, see Nimrod.

Selected words by origin

Words derived from Arabic:

- Alforría - "liberty", "freedom"

- Alhát - "Sunday"

- Atemar - to terminate

- Saraf - "money changer"

- Shara - "wood"

- Ziara - "cemetery visit"

Words derived from Hebrew:

- Alefbet - "alphabet" (from the Hebrew names of the first two letters of the alphabet)

- Anav - "humble", "obedient"

- Arón - "grave"

- Atakanear - to arrange

- Badkar - to reconsider

- Beraxa - "blessing"

- Din - "religious law"

- Kal - "community", "synagogue"

- Kamma - to ask "how much?", "how many?"

- Maaráv - "west"

- Maasé - "story", "event"

- Maabe - "deluge", "downpour", "torrent"

- Mazal - "star", "destiny"

- Met - "dead"

- Niftar - "dead"

- Purimlik - "Purim present" (Derived from the Hebrew "Purim" + Turkic ending "-lik")

- Sedaka - "charity"

- Tefilá - "prayer"

- Zahut - "blessing"

Words derived from Persian:

- Chay - "tea"

- Chini - "plate"

- Paras - "money"

- Shasheo - "dizziness"

Words derived from Portuguese:

- Abastádo - "almighty", "omnipotent" (referring to God)

- Aínda - "yet"

- Chapeo - "hat"

- Preto - "black" (in color)

- Trocar - to change

Words derived from Turkish:

- Balta - "axe"

- Biterear - to terminate

- Boyadear - to paint, color

- Innat - "whim"

- Kolay - "easy"

- Kushak - "belt", "girdle"

- Maalé - "street", "quarters", "neighborhood"; Maalé yahudí - Jewish quarters

Modern singers

Jennifer Charles and Oren Bloedow from the New York-based band Elysian Fields released a CD in 2001 called La Mar Enfortuna, which featured modern versions of traditional Sephardic songs, many sung by Charles in Judeo-Spanish. The American singer, Tanja Solnik, has released several award-winning albums that feature songs sung in Ladino: From Generation to Generation: A Legacy of Lullabies and Lullabies and Love Songs. There are a number of groups in Turkey that sing in Judeo-Spanish, notably Janet – Jak Esim Ensemble, Sefarad, Los Pasharos Sefaradis, and the children's chorus Las Estreyikas d'Estambol. There is a Brazilian-born singer of Sephardic origins[citation needed] called Fortuna who researches and plays Judeo-Spanish music.

The Jewish Bosnian-American musician Flory Jagoda recorded two CDs of music taught to her by her grandmother, a Sephardic folk singer, among a larger discography.

The cantor Dr. Ramón Tasat, who learned Judeo-Spanish at his grandmother's knee in Buenos Aires, has recorded many songs in the language, with three of his CDs focusing primarily on that music.

The Israeli singer Yasmin Levy has also brought a new interpretation to the traditional songs by incorporating more "modern" sounds of Andalusian Flamenco. Her work revitalising Sephardi music has earned Levy the Anna Lindh Euro-Mediterranean Foundation Award for promoting cross-cultural dialogue between musicians from three cultures.[41] In Yasmin Levy's own words:

I am proud to combine the two cultures of Ladino and flamenco, while mixing in Middle Eastern influences. I am embarking on a 500 years old musical journey, taking Ladino to Andalusia and mixing it with flamenco, the style that still bears the musical memories of the old Moorish and Jewish-Spanish world with the sound of the Arab world. In a way it is a ‘musical reconciliation’ of history.[42]

Notable music groups performing in Judeo-Spanish include Voice of the Turtle, Oren Bloedow and Jennifer Charles' "La Mar Enfortuna" and Vanya Green, who was awarded a Fulbright Fellowship for her research and performance of this music. She was recently selected as one of the top ten world music artists by the We are Listening International World of Music Awards for her interpretations of the music.

Robin Greenstein, a New York-based musician, received a federal CETA grant in the 1980s to collect and perform Sephardic Ladino Music under the guidance of the American Jewish Congress. Her mentor was Joe Elias, noted Sephardic singer from Brooklyn. She recorded residents of the Sephardic Home for the Aged, a nursing home in Coney Island, NY singing songs from their childhood. Amongst the voices recorded was Victoria Hazan, a well known Sephardic singer who recorded many 78's in Ladino and Turkish from the 1930s and 1940s. Two Ladino songs can be found on her "Songs of the Season" holiday CD released in 2010 on Windy Records.

See also

- Haketia

- Jewish languages

- Judaism

- Judaeo-Spanish Wikipedia

- Judeo-Portuguese

- Judeo-Romance languages

- Mozarabic

- Aki Yerushalayim, an Israeli magazine in Judeo-Spanish published 2–3 times a year

- Şalom, a Turkish newspaper with a Judeo-Spanish page[43]

- Sephardic Jews

- Tetuani Ladino

- Knaanic language

- Yiddish language

- Los Serenos Sefarad, Djudeo Espanyol Hip-Hop

- Cicurel family

- Pallache family

References

Notes

- ^ Also pronounced [dʒuˈdeu spaˈɲol] (Western Judaeo-Spanish) and [ʒuˈðeo espaˈɲol] (Moroccan dialects).

- ^ Speakers use different orthographical conventions depending on their social, educational, national and personal backgrounds, thus there is no uniformity in spelling, although some established conventions exist. The endonym Judeo-Espanyol is thus also spelled as Cudeo-Espanyol, Djudeo-Espanyol, Djudeo-Espagnol, Judeo-Español, Judeo-Espaniol, Džudeo-Espanjol, Giudeo-Espagnol, Ǧudéo-Españól and Ĵudeo-Español.

- ^ The modern Spanish spelling Mallorca is a hypercorrection.

Citations

- ^ Judaeo-Spanish at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Minervini, Laura (2006). "El desarollo histórico del judeoespañol". Revista Internacional de Lingüística Iberoamericana.

- ^ a b Jewish Museum of Thessaloniki. Jmth.gr. Retrieved on 19 October 2011.

- ^ Real Academia Española dictionary, entry: Judeo-Español in the Diccionario de la Real Academia Española (DRAE).

- ^ Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (2005). "Ladino". Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Fifteenth edition. SIL International. Retrieved 25 September 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Harris, Tracy (1994). Death of a language: The history of Judeo-Spanish. Newark, DE: University of Delaware Press.

- ^ Template:Es icon DRAE: Ladino, 2nd sense. Buscon.rae.es. Retrieved on 19 October 2011.

- ^ Historia 16, 1978

- ^ Real Academia Española dictionary (2001), entry: Ladino Dictionary of the Royal Spanish Academy of the Spanish tongue, Diccionario de la lengua española de la Real Academia Española, Espasa.

- ^ "Clearing up Ladino, Judeo-Spanish, Sephardic Music" Judith Cohen, HaLapid, winter 2001; Sephardic Song at the Wayback Machine (archived 16 April 2008), Judith Cohen, Midstream July/August 2003

- ^ The UCLA Phonetics Lab archive

- ^ a b c d e Penny, Ralph (2000). Variation and Change in Spanish. Cambridge University Press. pp. 179–189. ISBN 0 521 60450 8.

- ^ Batzarov, Zdravko. "Judeo-Spanish: Noun". www.orbilat.com. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- ^ Verba Hispanica X: Los problemas del estudio de la lengua sefardí, Katja Šmid, Ljubljana, pages 113–124: Es interesante el hecho que en Bulgaria se imprimieron unas pocas publicaciones en alfabeto cirílico búlgaro y en Grecia en alfabeto griego. [...] Nezirović (1992: 128) anota que también en Bosnia se ha encontrado un documento en que la lengua sefardí está escrita en alfabeto cirilico. The Nezirović reference is: Nezirović, M., Jevrejsko-Španjolska književnost. Institut za književnost, Svjetlost, Sarajevo, Bosnia 1992.

- ^ See preface by Iacob M Hassán to Romero, Coplas Sefardíes, Cordoba, pp. 23–24.

- ^ "Ladinoikonunita: A quick explanation of Ladino (Judaeo-Spanish). Sephardicstudies.org. Retrieved on 19 October 2011.

- ^ palavră in the Dicționarul etimologic român, Alexandru Ciorănescu, Universidad de la Laguna, Tenerife, 1958–1966: Cuvînt introdus probabil prin. iud. sp: "Word introduced probably through Judaeo-Spanish.

- ^ Συγκριτικός πίνακας των στοιχείων των απογραφών του 1928, 1940 ΚΑΙ 1951 σχετικά με τις ομιλούμενες γλώσσες στην Ελλάδα. – Μεινοτικές γλώσσες στην Ελλάδα Κωνσταντίνος Τσιτσελίκης (2001), Πύλη για την Ελληνική Γλώσσα

- ^ Eliezer Papo: From the Wailing Wall (in Bosnian)

- ^ Reka Network: Kol Israel International Archived 23 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Radio Exterior de España: Emisión en sefardí

- ^ Nir Hasson, Holocaust survivor revives Jewish dialect by translating Greek epic, at Haaretz, 9 March 2012.

- ^ Borovaya, Olga (2012). Modern Ladino Culture: Press, Belles Lettres, and Theater in the Late Ottoman Empire. Indiana University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978 0 253 35672 7.

- ^ Borovaya, Olga (2012). Modern Ladino Culture: Press, Belles Lettres, and Theater in the Late Ottoman Empire. Indiana University Press. p. 24. ISBN 978 0 253 35672 7.

- ^ Borovaya, Olga (2012). Modern Ladino Culture: Press, Belles Lettres, and Theater in the Late Ottoman Empire. Indiana University Press. p. 144. ISBN 978 0 253 35672 7.

- ^ Borovaya, Olga (2012). Modern Ladino Culture: Press, Belles Lettres, and Theater in the Late Ottoman Empire. Indiana University Press. p. 191. ISBN 978 0 253 35672 7.

- ^ Etz Ahaim home page

- ^ Frishman, Elyse D., ed. (2007). Mishkan T'filah : a Reform siddur : services for Shabbat. New York: Central Conference of American Rabbis. p. 327. ISBN 0-88123-104-5.

- ^ > Events > Exhibitions > Rare Book Library Collection Restoration Project – Ladino. American Sephardi Federation (23 April 1918). Retrieved on 19 October 2011.

- ^ Yalkut May'Am Loez, Jerusalem 5736 Hebrew translation from Ladino language.

- ^ Price, Sarah. (2005-08-25) Schools to Teach Ein Bisel Yiddish | Education. Jewish Journal. Retrieved on 19 October 2011.

- ^ The Mendele Review: Yiddish Literature and Language, Volume 11, No. 10. Yiddish.haifa.ac.il (30 September 2007). Retrieved on 19 October 2011.

- ^ EJP | News | Western Europe | Judaeo-Spanish language revived. Ejpress.org (19 September 2005). Retrieved on 19 October 2011.

- ^ Jewish Studies Program. Ccat.sas.upenn.edu. Retrieved on 19 October 2011.

- ^ Ladino Class at Penn Tries to Resuscitate Dormant Language. The Jewish Exponent (1 February 2007). Retrieved on 19 October 2011.

- ^ Department of German, Russian & Asian Languages and Literature – Tufts University. Ase.tufts.edu. Retrieved on 19 October 2011.

- ^ For love of Ladino – The Jewish Standard. Jstandard.com. Retrieved on 19 October 2011.

- ^ Courses – Ladino Studies At The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Pluto.huji.ac.il (30 July 2010). Retrieved on 19 October 2011.

- ^ "Hebrew Philology courses (in Spanish)". UCM. UCM. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- ^ title=Why I'm teaching a new generation to read and write Ladino|url=http://jewishstudies.washington.edu/blog/why-im-teaching-a-new-generation-to-read-and-write-ladino

- ^ "2008 Event Media Release – Yasmin Levy". Sydney Opera House. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- ^ "BBC – Awards for World Music 2007 – Yasmin Levy". BBC. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- ^ Åžalom Gazetesi – 12.10.2011 – Judeo-Espanyol İçerikleri. Salom.com.tr. Retrieved on 19 October 2011.

Bibliography

- Barton, Thomas Immanuel (Toivi Cook) (2010) Judezmo Expressions. USA ISBN 978-89-00-35754-7

- Barton, Thomas Immanuel (Toivi Cook) (2008) Judezmo (Judeo-Castilian) Dictionary. USA ISBN 978-1-890035-73-0

- Bunis, David M. (1999) Judezmo: an introduction to the language of the Sephardic Jews of the Ottoman Empire. Jerusalem ISBN 978-965-493-024-6

- Габинский, Марк А. (1992) Сефардский (еврейской-испанский) язык (M. A. Gabinsky. Sephardic (Judeo-Spanish) language, in Russian). Chişinău: Ştiinţa

- Harris, Tracy. 1994. Death of a language: The history of Judeo-Spanish. Newark, DE: University of Delaware Press.

- Hemsi, Alberto (1995) Cancionero Sefardí; edited and with an introduction by Edwin Seroussi (Yuval Music Series; 4.) Jerusaelem: The Jewish Music Research Centre, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem

- Hualde, José Ignacio and Mahir Saul (2011) "Istanbul Judeo-Spanish" Journal of the International Phonetic Association 41(1): 89-110.

- Hualde, José Ignacio (2013) “Intervocalic lenition and word-boundary effects: Evidence from Judeo-Spanish”. Diachronica 30.2: 232-26.

- Kohen, Elli; Kohen-Gordon, Dahlia (2000) Ladino-English, English-Ladino: concise encyclopedic dictionary. New York: Hippocrene Books

- Markova, Alla (2008) Beginner's Ladino with 2 Audio CDs. New York: Hippocrene Books ISBN 0-7818-1225-9

- Markus, Shimon (1965) Ha-safa ha-sefaradit-yehudit (The Judeo-Spanish language, in Hebrew). Jerusalem

- Minervini, Laura (1999) “The Formation of the Judeo-Spanish koiné: Dialect Convergence in the Sixteenth Century”. In Proceedings of the Tenth British Conference on Judeo-Spanish Studies. Edited by Annete Benaim, 41-52. London: Queen Mary and Westfield College.

- Minervini, Laura (2006) “El desarollo histórico del judeoespañol,” Revista Internacional de Lingüística Iberoamericana 4.2: 13-34.

- Molho, Michael (1950) Usos y costumbres de los judíos de Salónica

- Quintana Rodriguez, Aldina. 2001. Concomitancias lingüisticas entre el aragones y el ladino (judeoespañol). Archivo de Filología Aragonesa 57–58, 163–192.

- Quintana Rodriguez, Aldina. 2006. Geografía lingüistica del judeoespañol: Estudio sincrónico y diacrónico. Bern: Peter Lang.

- Varol, Marie-Christine (2004) Manuel de Judéo-Espagnol, langue et culture (book & CD, in French), Paris: L'Asiathèque ISBN 2-911053-86-9

Further reading

- Lleal, Coloma (1992) "A propósito de una denominación: el judeoespañol", available at Centro Virtual Cervantes, http://www.cervantesvirtual.com/FichaObra.html?Ref=19944

- Saporta y Beja, Enrique, comp. (1978) Refranes de los judíos sefardíes y otras locuciones típicas de Salónica y otros sitios de Oriente. Barcelona: Ameller

External links

- Template:DMOZ

- Autoridad Nasionala del Ladino Template:Lad icon

- Ladino

- Jewish Museum of Thessaloniki

- Ladino Center

- Ladinokomunita, an email list in Ladino

- La pajina djudeo-espanyola de Aki Yerushalayim

- The Ladino Alphabet

- Judeo-Spanish (Ladino) at Orbis Latinus

- Ladino music by Suzy and Margalit Matitiahu

- Socolovsky, Jerome. "Lost Language of Ladino Revived in Spain", Morning Edition, National Public Radio, 19 March 2007.

- A randomly selected example of use of ladino on the Worldwide Web: La komponente kulinaria i linguístika turka en la kuzina djudeo-espanyola

- Israeli Ladino Language Forum (Hebrew)

- LadinoType – A Ladino Transliteration System for Solitreo, Meruba, and Rashi

- Habla Ladino? Sephardim meet to preserve language Friday 9 January 1998

- Edición SEFARAD, Radio programme in Ladino from Radio Nacional de España

- Etext of Nebrija's Gramática de la lengua castellana, showing orthography of Old Spanish.

- Sefarad, Revista de Estudios Hebraicos, Sefardíes y de Oriente Próximo, ILC, CSIC

- Judæo-Spanish Language (Ladino) and Literature, Jewish Encyclopedia

- Dr Yitshak (Itzik) Levy An authentic documentation of Ladino heritage and culture

- Sephardic Studies Digital Library & Museum – UW Stroum Jewish Studies

- An inside look into the Portuguese corpus of words in Nehama's Dictionnaire du Judeo-Espagnol Yossi Gur, 2003.