Ooty

Ooty

Udagamandalam | |

|---|---|

Town | |

| Ootacamund | |

| Nickname: Queen of hill stations[1] | |

| Coordinates: 11°25′N 76°42′E / 11.41°N 76.70°E | |

| Country | |

| State | Tamil Nadu |

| Region | Kongu Nadu |

| District | Nilgiris District |

| Government | |

| • Type | Special Grade Municipality |

| • Body | Udagamandalam Municipality |

| Area | |

• Total | 30.36 km2 (11.72 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 2,240 m (7,350 ft) |

| Population (2011)[3] | |

• Total | 88,430 |

| • Density | 2,900/km2 (7,500/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Ootian, Ootacamandian, Udaghaikaran |

| Languages | |

| • Official | Tamil |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

| PIN | 643001 |

| Tele | 91423 |

| Vehicle registration | TN-43 |

| Climate | Subtropical Highland (Köppen) |

| Precipitation | 1,100 mm (43 in) |

| Website | tnurbantree.tn.gov.in/ |

Ooty (; officially Udagamandalam, anglicized: Ootacamund (), abbreviated as Udagai) is a town and municipality in the Nilgiris district of the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. It is located 86 km (53 mi) northwest of Coimbatore, and is the headquarters of Nilgiris district. Situated in the Nilgiri hills, it is known by the epithet "Queen of Hill Stations", and is a popular tourist destination.

Originally occupied by the Toda people, the area came under the rule of the East India Company in the 18th century. It later served as the summer capital of Madras Presidency. The economy is based on the hospitality industry serving tourism and agriculture. The town is connected to the plains by the Nilgiri ghat roads and Nilgiri Mountain Railway.

Etymology

[edit]The region was earlier known as Ottakal Mandu, with Otha-Cal meaning "single stone" in Tamil, a reference to a sacred stone revered by the local Toda people and Mandu, a Toda word for "village".[4] This later became Udagamandalam which was anglicised to Ootacamund by the British, with the first part of the name (Ootaca), a corruption of the local name for the region and the second part (Mand), a shortening of the local Toda word Mandu.[5][6][7] The first known written mention of the place is given as Wotokymund in a letter dated March 1821, written to the Madras Gazette by an unknown correspondent.[8] Ootacamund was later shortened to Ooty. Ooty is in the Nilgiri hills, meaning the "blue mountains", so named due to the Kurunji flower, which used to give the slopes a bluish tinge.[9]

History

[edit]The earliest reference to Nilgiri hills is found in the Tamil Sangam epic Silappathikaram from the 5th or 6th century CE.[9] The region was a land occupied by various tribes such as Badagas, Todas, Kotas, Irulas and Kurumbas.[2] The region was ruled by the three tamil kingdoms of Cheras, Cholas and Pandyas during various times.[10][11] The Todas are referenced in a record belonging to Hoysala king Vishnuvardhana and his general Punisa, dated 1117 CE.[12] It was also ruled by various dynasties like Pallavas, Satavahanas, Gangas, Kadambas, Rashtrakutas, Hoysalas and the Vijayanagara empire.[13][14] Tipu Sultan captured Nilgiris in the eighteenth century and the region came into possession of British in 1799.[15] It became part of Coimbatore district of the Madras Presidency.[8]

In 1818, J. C. Whish and N. W. Kindersley, assistants to John Sullivan, then collector of Coimbatore district, visited Kotagiri nearby and reported on the region's potential to serve as a summer retreat.[9] Sullivan established his residence there and reported to the Board of Revenue on 31 July 1819. He also started work on a road from Sirumugai which was completed in May 1823 and extended up to Coonoor between 1830–32.[9] By 1827, it was established as a sanatorium of the Madras Presidency and developed further at the behest of then Governor of Madras Stephen Lushington. The Government Botanical Garden, covering 51 acres (21 ha), was established in 1842 and a library was established in 1959.[16]

Ooty was made a municipality in 1866, and civic improvements including roads, drainage, and water supply from the Marlimund and Tiger Hill reservoirs were added through Government loans.[16] In August 1868, the Nilgiris was separated from the Coimbatore district, and James Wilkinson Breeks was appointed its first commissioner.[9] On 1 February 1882, Nilgiris was made a district, and Richard Wellesley Barlow, the then commissioner, became its first collector.[8] By the early 20th century, Ooty was a well-developed hill station, with an artificial lake, various parks, religious structures, and sporting facilities for polo, golf, and cricket.[16] It served as the summer capital of the Madras Presidency and as a retreat for the British officials.[17]

Post-independence, the town developed into a popular hill resort and the nearby Wellington became the home of the Defence Services Staff College of the Indian Army.[18][19]

Geography

[edit]

Ooty is located in the Nilgiri hills, which are part of the Western Ghats in the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve. It is separated from the neighboring state of Karnataka by the Moyar river in the north and from the Anaimalai and Palani hills in the south by the Palghat Gap.[20] It is situated at an altitude of 2,240 metres (7,350 feet) above sea level.[2] The total area of the town is 30.36 km2 (11.72 sq mi).[2] Doddabetta is the highest peak (2,623 m or 8,606 ft) in the Nilgiris, about 10 km (6.2 mi) from Ooty.[21]

Ooty Lake is an artificial lake covering 65 acres (26 ha) created in 1824.[22] The Pykara, a river located 19 km (12 mi) from Ooty, rises at Mukurthi peak and flows through a series of cascades with the last two falls of 55 metres (180 ft) and 61 metres (200 ft) known as Pykara falls.[23] Kamaraj Sagar Dam is located 10 km (6.2 mi) from the Ooty.[24] Emerald Lake, Avalanche Lake and Porthimund Lake are other lakes in the region.[25]

Climate

[edit]Ooty features a subtropical highland climate (Cwb) under Köppen climate classification.[26] Because of its high altitude, the temperatures are generally lower than the surrounding plains with the average between 10–25 °C (50–77 °F) during summer and 0–21 °C (32–70 °F) during winter.[2] The highest temperature ever recorded was 28.5 °C (83.3 °F) and the lowest temperature was −5.1 °C (22.8 °F).[27] The town gets heavy rainfall during both South-West and North-East monsoons and the average rainfall is about 1,100 millimetres (43 in) of precipitation annually.[2]

| Climate data for Ooty (Udagamandalam) 1991-2020 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 27.5 (81.5) |

27.3 (81.1) |

27.5 (81.5) |

28.5 (83.3) |

28.0 (82.4) |

26.1 (79.0) |

24.4 (75.9) |

23.0 (73.4) |

23.3 (73.9) |

26.8 (80.2) |

25.2 (77.4) |

27.4 (81.3) |

28.5 (83.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 21.4 (70.5) |

21.9 (71.4) |

23.3 (73.9) |

22.7 (72.9) |

22.8 (73.0) |

18.8 (65.8) |

17.2 (63.0) |

17.5 (63.5) |

19.1 (66.4) |

19.0 (66.2) |

19.1 (66.4) |

20.9 (69.6) |

20.4 (68.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 6.5 (43.7) |

7.3 (45.1) |

9.5 (49.1) |

11.1 (52.0) |

11.8 (53.2) |

11.7 (53.1) |

11.2 (52.2) |

11.0 (51.8) |

10.8 (51.4) |

10.6 (51.1) |

9.6 (49.3) |

6.9 (44.4) |

9.8 (49.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −2.1 (28.2) |

0.0 (32.0) |

1.1 (34.0) |

4.0 (39.2) |

4.4 (39.9) |

2.2 (36.0) |

2.5 (36.5) |

4.6 (40.3) |

4.4 (39.9) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−2.1 (28.2) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 4.9 (0.19) |

5.1 (0.20) |

22.4 (0.88) |

84.0 (3.31) |

123.9 (4.88) |

147.6 (5.81) |

152.3 (6.00) |

116.5 (4.59) |

117.1 (4.61) |

189.2 (7.45) |

144.5 (5.69) |

49.9 (1.96) |

1,157.4 (45.57) |

| Average rainy days | 0.7 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 5.6 | 8.6 | 11.1 | 12.4 | 9.4 | 8.9 | 11.4 | 7.8 | 3.2 | 80.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 17:30 IST) | 69 | 67 | 61 | 70 | 75 | 85 | 88 | 88 | 86 | 86 | 85 | 73 | 77 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 6 |

| Source 1: Indian Meteorological Department[28][29] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather2Travel for sunshine [30] | |||||||||||||

Biodiversity and wildlife

[edit]

Ooty forms part of the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve, the largest protected forest area in India.[31] It was declared as a protected reserve in 1986 and is part of UNESCO's Man and the Biosphere Programme.[32] Mudumalai National Park and tiger reserve lies on the north-western side, about 31 km (19 mi) from Ooty and was established in 1940 as the first wildlife sanctuary in India.[33]

The region is part of the South Western Ghats montane rain forests ecoregion.[34] Nilgiris harbours thousands of plant species including medicinal plants and endemic flowering plants.[32] Stunted evergreen trees grow in shola forest patches above 1,800 m (5,900 ft) and are festooned with epiphytes.[35] The native vegetation consisted of Meadows and grasslands on the hillsides with shola forests in the valleys. When the British populated the town, invasive species of pine, wattle and eucalyptus were planted along with tea plantations and they became the dominant species replacing the native vegetation.[36]

The region has one of the largest bengal tiger populations.[37] The Indian elephant is the largest mammal in the region.[38] The gaur is the largest ungulate in the region that frequent grasslands in the vicinity of water sources.[39] Other mega-fauna include Indian leopard and sloth bear.[40] Smaller fauna include Jungle cat, rusty-spotted cat, leopard cat, dhole, Golden jackal, Nilgiri marten, Small Indian civet, Asian palm civet, brown palm civet, ruddy mongoose, wild boar, Indian pangolin, Indian crested porcupine and Indian giant squirrel.[41] Indian giant flying squirrel,[42][43][44][45][46] Smooth-coated otter groups are observed along the Moyar River.[47] Deer include sambar deer, chital, Indian spotted chevrotain, Indian muntjac, four-horned antelope and blackbuck.[48] Monkeys, including the endangered Nilgiri langur, bonnet macaque and gray langur are also found in the region.[49] Nilgiri tahr is an endangered ungulate that is endemic to the Nilgiris and is the state animal of Tamil Nadu.[50] Bats are found in darker caves in the hills.[51] More than 200 species of birds are found in the region.[52]

Demographics

[edit]According to the 2011 census, Udagamandalam had a population of 88,430 with a sex-ratio of 1,053 females for every 1,000 males, much above the national average of 929.[3][53] A total of 7,781 were under the age of six, constituting 3,915 males and 3,866 females.Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes accounted for 28.98% and 0.30% of the population respectively. The average literacy of the city in 2011 was 90.2%,[54] compared to the national average of 72.99%.[53] The city had a total of 23,235 households. There were a total of 35,981 workers, comprising 636 cultivators, 5,194 agricultural labourers, 292 in household industries, 26,411 other workers, 3,448 marginal workers, 65 marginal cultivators, 828 marginal agricultural labourers, 56 marginal workers in household industries and 2,499 other marginal workers.[55] As per the religious census of 2011, Udagamandalam had 64.36% Hindus, 21.25% Christians, 13.37% Muslims, 0.03% Sikhs, 0.3% Buddhists, 0.4% Jains, 0.28% following other religions and 0.02% following no religion or did not indicate any religious preference.[56]

Tamil is the official language of Udagamandalam. Languages native to the Nilgiris including Badaga, Paniya, Irula and Kurumba.[57] Due to its proximity to the neighboring states of Kerala and Karnataka and being a tourist destination, Malayalam, Kannada and English are also spoken and understood to an extent.[58] According to the 2011 census, the most widely spoken languages in Udagamandalam taluk were Tamil, spoken by 88,896, followed by Badaga with 41,213 and Kannada with 27,070 speakers.[59]

Administration and politics

[edit]Ooty is the headquarters of the Nilgiris district.[8] The town is part of the Udagamandalam Assembly constituency which forms part of the Nilgiris Lok Sabha constituency.[60] The town is administered by Udagamanadalam municipality which was established in 1866 and the town is divided into 36 wards.[61] The municipality is responsible for water services, sewage disposal and maintenance of public infrastructure.[62]

Economy

[edit]

Ooty is a market town for the surrounding area, which is still largely dependent on agriculture. Vegetables cultivated include potato, carrot, cabbage and cauliflower and fruits include peach, plum, pear and strawberry.[63] There is a daily wholesale auction of these products at the Ooty Municipal Market.[64] Dairy farming has long been present in the area, and there is a cooperative dairy manufacturing cheese and skimmed milk powder.[65] Floriculture and sericulture are also practised, as is the cultivation of mushrooms. The local area is known for tea cultivation. Nilgiri tea is a black tea variety unique to the region.[66]

The Human Biologicals Institute, established in 1999, is involved in vaccine manufacturing.[67] Other manufacturing industries located on the outskirts include Ketti (manufacture of needles) and Aruvankadu (manufacture of cordite).

Transport

[edit]Road

[edit]Ooty is connected by roads known as the Nilgiri Ghat Roads. It is situated on NH 181. The municipality maintains roads in the town.[68] Public bus services are operated by the Coimbatore division of TNSTC.[69] SETC, KSRTC (Karnataka) and KSRTC (Kerala) connect to distant towns in Tamil Nadu and neighboring states.

Rail

[edit]

Nilgiri Mountain Railway is a 1,000 mm (3 ft 3+3⁄8 in) metre gauge railway in Nilgiris district, connecting Udagamandalam and Mettupalayam. The Nilgiri Railway Company was formed in 1885, and the Mettupalayam-Coonoor section of the track was opened for traffic on 15 June 1899. The railway was operated by the Madras Railway until 31 December 1907, when it was handed over to the South Indian Railway. The line from Coonoor to Ooty was completed in 1908.[70][71] Operated currently by the Southern Railway zone of Indian Railways, it is the only rack railway in India and operates on its own fleet of steam locomotives between Coonoor and Udagamandalam.[72] In July 2005, UNESCO added the Nilgiri Mountain Railway as an extension to the World Heritage Site of Mountain Railways of India.[71]

Air

[edit]The nearest airport is Coimbatore International Airport, located 96 km (60 mi) from the town. The airport has regular flights from and to major domestic destinations and international destinations like Sharjah, Colombo and Singapore.[73] Ooty has three helipads, one at Theettukal and two at Kodanad with the Theettukal helipad, approved by the Airports Authority of India for defence and VIP services. Pawan Hans planned to start commercial services with Bell 407, but the plan has been shelved.[74][75]

Education

[edit]Government Arts College, established in 1955, is one of the oldest institutions in Ooty and is affiliated with Bharathiar University.[76] There are a few other colleges in the town. Boarding schools have been a feature of Ooty since the British Raj and continue to operate currently, including some of the most expensive schools in India.[77]

Tourism

[edit]

A boat house located alongside the Ooty Lake offers boating facilities to tourists and is a major tourist attraction in Ooty.[22] Similar boating facilities are also available at the Pykara falls and dam.[23] The Government Botanical Garden, laid out in 1842, has several speciesindigenous and exotic plants, and hosts an annual flower show in May.[16][78] The garden also hosts a 20-million-year-old fossilized tree.[79] The Government Rose Garden, situated on the slopes of Elk Hill at an altitude of 2,200 m (7,200 ft), has more than 20,000 varieties of roses from 2,800 cultivars and is the largest rose garden in India.[80] A deer park was established along the edges of the lake in 1986 and is the second-highest altitude zoo in India.[81]

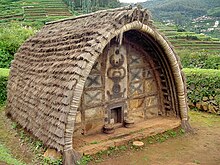

There are a few traditional Toda dogles (huts) on the hills above the Botanical Garden.[82] A Tribal Museum was opened in 1995 as a part of the Tribal Research Center, located about (10 km (6.2 mi) from the town and hosts rare artifacts and photographs of tribal groups of Tamil Nadu and Andaman and Nicobar, and other anthropological and archaeological finds on early human culture and heritage.[83] The Stone House was the first bungalow constructed in the town.[84] St Stephen's Church, built in 1829, is one of the oldest churches in the Nilgiris district.[85] St. Thomas Church, opened in 1871, hosts many famous graves in the churchyard including those of Josiah John Goodwin, William Patrick Adam, whose grave is topped by a pillar monument dedicated to St. Thomas, the tallest structure in Ooty.[86][87] Spread over an area of nearly 1 acre (0.40 ha), a tea factory and museum displays the process of tea processing and the machines used.[88]

The Ooty Radio Telescope was completed in 1970 and is part of the National Centre for Radio Astrophysics (NCRA) of the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR), funded by the Government of India through the Department of Atomic Energy.[89]

Sports and recreation

[edit]Snooker originated on the billiard tables of the Ootacamund Club, invented by Neville Chamberlain.[90] There was also a cricket ground with regular matches played between teams from the Army and Indian Civil Service. There were riding stables and kennels at Ooty and the hounds hunted across the surrounding countryside and the open grasslands of the Wenlock downs. Horse racing is held at the Ooty Racecourse.[91][92] Ooty Golf Course is at an altitude of 7,600 feet (2,300 m) and extends over 193.56 acres (78.33 ha).[93]

In popular culture

[edit]Ooty varkey is a crispy and crusty cookie snack popular in Ooty.[94] A number of films have been shot in Ooty. The town was used as a setting in David Lean's 1984 movie, A Passage to India, which was based on E. M. Forster's novel of the same name.[95]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Queen of hill stations-Ooty". Hindustan Times. 9 October 2012. Archived from the original on 27 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Udagamandalam". Government of Tamil Nadu. Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ a b Udagamandalam City Population Census 2011 – Tamil Nadu (Report). Registrar General and Census Commissioner, Government of India. Archived from the original on 14 August 2024. Retrieved 14 August 2024.

- ^ Mathew Chacko, Pariyaram (2005). Tribal Communities and Social Change. SAGE. pp. 180, 188. ISBN 978-0-7619-3330-4.

- ^ Price, Frederick (1908). Ootacamund, A History. Madras Government Press. pp. 14–15.

- ^ Guides, Rough (October 2023). The Rough Guide to South India & Kerala (Travel Guide eBook). Apa Publications (UK) Limited. ISBN 978-1-83905-950-6.

- ^ Hariharan, Githa (22 March 2016). Almost Home: Finding a Place in the World from Kashmir to New York. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-63206-061-7. Archived from the original on 14 August 2024. Retrieved 14 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Nilgiris district". Government of Tamil Nadu. Archived from the original on 27 July 2023. Retrieved 15 February 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "Nilgiris history". Government of Tamil Nadu. Archived from the original on 2 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Senapati, Nilamani; Sahu, N. K. (1955). Gazetteers of India: Nilgiris District. Government Press. pp. 3, 199–201, 866.

The location of the Nilgiris is unique that it was in the tri-junction of ancient Tamil kingdoms of Cholas, Cheras and the Pandyas. Hence, it was under Cheras, Cholas or local chieftains at various...

- ^ Indian Navy (1989). Maritime Heritage of India. Notion Press. p. 244. ISBN 978-9-3520-6917-0.

At their peak, the Cholas ruled over not just the whole of south India, but also conquered island nations..

- ^ Francis, Walter (1908). Madras District Gazetteers: The Nilgiris. Vol. 1. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. pp. 90–94, 102–105. ISBN 978-8-1206-0546-6.

- ^ Sundaresan, C.S. (1 January 2007). South Asia and Multilateral Trade Regime: Disorders for Development. Regal Publications. p. 81. ISBN 978-8189-915-31-5.

- ^ Sagar, Ravi. "Decoding the Nilgiris" (PDF). India Brand Equity Foundation: 53. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 February 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

Not even the dynastic rulers—the Cheras, the Cholas, the Pandiyas, the Rashtrakutas, the Gangas, the Pallavas, the Kadambas and the Hoysalas—can be credited with discovering this jewel (Nilgiris) in their crown.

- ^ Kohn, George Childs (2013). Dictionary of Wars. Routledge. pp. 322–323. ISBN 978-1-1359-5494-9. Archived from the original on 8 November 2023. Retrieved 27 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d Hunter, William Wilson (1908). The Imperial Gazetteer Of India - Volume 19 (2 ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 238-240.

- ^ The Illustrated Weekly of India. Bennett, Coleman & Company. 1975. p. 39.

- ^ "Defence Services Staff College". Indian Army. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Ooty". Government of Tamil Nadu. Archived from the original on 22 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Nilgiri Hills". Britannica. Archived from the original on 8 October 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Udagamandalam". Britannica. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ a b "Ooty Lake". Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ a b "Pykara". Government of Tamil Nadu. Archived from the original on 4 October 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Kamraj Sagar Dam". WRIS, Government of India. Retrieved 23 August 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Avalanche". Government of Tamil Nadu. Archived from the original on 8 August 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- ^ "Climate: Ooty – Climate graph, Temperature graph, Climate table". Climate-Data. Archived from the original on 27 February 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- ^ "Extremes of Temperature & Rainfall for Indian Stations (Up to 2012)" (PDF). India Meteorological Department. December 2016. p. M207. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ^ "Climatological Tables of Observatories in India 1991-2020" (PDF). India Meteorological Department. Retrieved 8 April 2024.

- ^ "Monthly mean maximum & minimum temperature and total rainfall based upon 1901-2000 data" (PDF). imd.gov.in. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 April 2015. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- ^ "Ooty Climate and Weather Averages, India.htm". Weather2Travel. Archived from the original on 1 October 2015. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- ^ "Conservationist joins SC panel on elephant corridor case". The Hindu. 27 January 2021. ISSN 0971-751X. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- ^ a b Ranjit Daniels, R.J. & Vijayan, V.S. (1996). The Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve: A Review of Conservation Status with Recommendations for a Wholistic Approach to Management (PDF) (Report). Working Paper No. 16. Paris: UNESCO South-South Co-operation Programme for Environmentally Sound Socio-Economic Development in the Humid Tropics. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 27 December 2023.

- ^ Hegde, R. & Enters, T. (2000). "Forest products and household economy: a case study from Mudumalai Wildlife Sanctuary, Southern India". Environmental Conservation. 27 (3): 250–259. Bibcode:2000EnvCo..27..250H. doi:10.1017/S037689290000028X. S2CID 86160884.

- ^ Wikramanayake, Eric D. (2002). Terrestrial ecoregions of the Indo-Pacific: a Conservation Assessment. Washington, D.C.: Island Press. pp. 284–285. ISBN 978-1-5596-3923-1. OCLC 48435361.

- ^ Chandrashekara, U.M.; Muraleedharan, P.K. & Sibichan, V. (2006). "Anthropogenic pressure on structure and composition of a shola forest in Kerala, India". Journal of Mountain Science. 3 (1): 58–70. Bibcode:2006JMouS...3...58C. doi:10.1007/s11629-006-0058-0. S2CID 55780505.

- ^ "Invasive species may soon wipe out Shola vegetation from Nilgiris: Report". Down to Earth. 19 September 2019. Archived from the original on 27 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Kalle, R.; Ramesh, T.; Qureshi, Q. & Sankar, K. (2011). "Density of tiger and leopard in a tropical deciduous forest of Mudumalai Tiger Reserve, southern India, as estimated using photographic capture–recapture sampling". Acta Theriologica. 56 (4): 335–342. doi:10.1007/s13364-011-0038-9. S2CID 196598615.

- ^ Baskaran, N.; Udhayan, A. & Desai, A.A. (2010). "Status of the Asian Elephant population in Mudumalai Wildlife Sanctuary, southern India". Gajah (32): 6–13. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1070.6845.

- ^ Ramesh, T.; Sankar, K.; Qureshi, Q. & Kalle, R. (2012). "Group size and population structure of megaherbivores (gaur Bos gaurus and Asian elephant Elephas maximus) in a deciduous habitat of Western Ghats, India". Mammal Study. 37 (1): 47–54. doi:10.3106/041.037.0106. S2CID 86098742.

- ^ Ramesh, T.; Sankar, K. & Qureshi, Q. (2009). "Additional notes on the diet of Sloth Bear Melursus ursinus in Mudumalai Tiger Reserve as shown by scat analysis". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 106 (2): 204–206.

- ^ Baskaran, N.; Venkatesan, S.; Mani, J.; Srivastava, S.K. & Desai, A.A. (2011). "Some aspects of the ecology of the Indian Giant Squirrel Ratufa indica (Erxleben, 1777) in the tropical forests of Mudumalai Wildlife Sanctuary, southern India and their conservation implications". Journal of Threatened Taxa. 3 (7): 1899–1908. doi:10.11609/JoTT.o2593.1899-908.

- ^ Babu, S.; Kumara, H.N. & Jayson, E.A. (2015). "Distribution, abundance, and habitat signature of the Indian Giant Flying Squirrel Petaurista philippensis (Elliot 1839) in the Western Ghats, India". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 112 (2): 65–71. doi:10.17087/jbnhs/2015/v112i2/104925.

- ^ Kalle, R.; Ramesh, T.; Qureshi, Q. & Sankar, K. (2013). "The occurrence of small felids in Mudumalai Tiger Reserve, Tamil Nadu, India". Cat News (58): 32–35.

- ^ Venkataraman, A.B.; Arumugam, R. & Sukumar, R. (1995). "The foraging ecology of dhole (Cuon alpinus) in Mudumalai Sanctuary, southern India". Journal of Zoology. 237 (4): 543–561. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1995.tb05014.x.

- ^ Kalle, R.; Ramesh, T.; Sankar, K. & Qureshi, Q. (2013). "Observations of sympatric small carnivores in Mudumalai Tiger Reserve, Western Ghats, India". Small Carnivore Conservation. 49 (4): 53–59.

- ^ Kalle, R.; Ramesh, T.; Sankar, K. & Qureshi, Q. (2012). "Diet of mongoose in Mudumalai Tiger Reserve, southern India". Journal of Scientific Transactions in Environment and Technovation. 6 (1): 44–51.

- ^ Narasimmarajan, K.; Hayward, M.W. & Mathai, M.T. (2021). "Assessing the occurrence and resource use pattern of Smooth-coated Otters Lutrogale perspicillata Geoffroy (Carnivora, Mustelidae) in the Moyar River of the Western Ghats Biodiversity Hotspot" (PDF). IUCN Otter Specialist Group Bulletin. 38 (1): 45–58. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 October 2021. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ^ Ramesh, T.; Sankar, K.; Qureshi, Q. & Kalle, R. (2012). "Group size, sex and age composition of chital (Axis axis) and sambar (Rusa unicolor) in a deciduous habitat of Western Ghats". Mammalian Biology. 77 (1): 53–59. doi:10.1016/j.mambio.2011.09.003.

- ^ Ramakrishnan, U. & Coss, R.G. (2000). "Recognition of heterospecific alarm vocalization by Bonnet Macaques (Macaca radiata)". Journal of Comparative Psychology. 114 (1): 3–12. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.558.6257. doi:10.1037/0735-7036.114.1.3. PMID 10739307.

- ^ Prater, S. H. (1971) [1948]. The book of Indian Animals. Bombay: Bombay Natural History Society.

- ^ Nachiketha, S.R. & Sreepada K.S. (2013). "Occurrence of Indian Painted Bat (Kerivuola picta) in dry deciduous forests of Mudumalai Tiger Reserve, Southern India" (PDF). Small Mammal Mail. 5 (1): 16–17. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 August 2022. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ^ Gokula, V. & Vijayan, L. (1996). "Birds of Mudumalai Wildlife Sanctuary, India" (PDF). Forktail. 12: 143–152. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 April 2023. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ^ a b Census Info 2011 Final population totals (Report). Registrar General and Census Commissioner, Government of India. 2013. Archived from the original on 13 November 2013. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ^ Provisional Population Totals, Census of India 2011 (PDF) (Report). Registrar General and Census Commissioner, Government of India. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 March 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ "Census Info 2011 Final population totals – Uthagamandalam". Office of The Registrar General and Census Commissioner, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. 2013. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ^ Population By Religious Community – Tamil Nadu (XLS) (Report). Registrar General and Census Commissioner, Government of India. 2011. Archived from the original on 13 September 2015. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- ^ International School of Dravidian Linguistics (1996). The encyclopaedia of Dravidian tribes. Vol. 2. International School of Dravidian Linguistics. p. 170.

- ^ "Languages in Ooty". mapsofindia. Archived from the original on 2 March 2008. Retrieved 16 February 2008.

- ^ "Census of India – Language". Registrar General and Census Commissioner, Government of India. Archived from the original on 1 November 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ List of Parliamentary and Assembly Constituencies (PDF) (Report). Election Commission of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 February 2009. Retrieved 10 October 2008.

- ^ Ward map, Udagamanadalam (PDF) (Report). Government of Tamil Nadu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 August 2024. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Water supply, Udagamanadalam". Government of Tamil Nadu. Archived from the original on 25 May 2024. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Organic farming is catching on in Tamil Nadu's Nilgiris". The Hindu. 20 November 2023. Archived from the original on 23 August 2024. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Stone throwing leads to tension in Uthagamandalam". The Hindu. 31 August 2009. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

- ^ "Oldest dairy farm in Ooty faces closure". New Indian Express. 2 November 2008. Archived from the original on 27 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ van Driem, George (2019). The Tale of Tea A Comprehensive History of Tea from Prehistoric Times to the Present Day. Brill. ISBN 978-9-0043-8625-9.

- ^ "commemorates 25 yrs of Human Biologicals Institute, announces new vaccines". The Times of India. 26 November 2023. Archived from the original on 27 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Roads in Uthagamandalam". Government of Tamil Nadu. Archived from the original on 3 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "New buses to replace TNSTC's aging fleet in the Nilgiris". The Hindu. 22 June 2023. Archived from the original on 27 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Nilgiri Mountain railway". Indian Railways. Archived from the original on 6 December 2019. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ^ a b "Mountain Railways of India". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 3 May 2006. Retrieved 30 April 2006.

- ^ "he Nilgiri Mountain Railway as old as the hills". The Hindu. 27 July 2019. Archived from the original on 30 March 2023. Retrieved 1 March 2023.

- ^ "Coimbatore Airport". Airports Authority of India. Archived from the original on 23 August 2024. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- ^ Anubhuti, Vishnoi (19 March 2008). "Ooty, Uttarakhand chopper plans hit roadblock". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ "Jayalalithaa leaves Kodanad". The Hindu. 13 August 2013. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ "Government Arts College". Government of Tamil Nadu. Archived from the original on 17 May 2022. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Top 10 expensive schools in India". Free press journal. Archived from the original on 23 August 2024. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Botanical Garden". Government of Tamil Nadu. Archived from the original on 1 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Hills beckon again". Tribune India. 22 January 2011. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Rose Garden". Government of Tamil Nadu. Archived from the original on 21 April 2024. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Deer Park". Government of Tamil Nadu. Archived from the original on 23 August 2024. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Chhabra, Tarun (2005). "How Traditional Ecological Knowledge addresses Global Climate change: the perspective of the Todas – the indigenous people of the Nilgiri hills of South India" (PDF). Proceedings of the Earth in Transition: First World Conference. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 September 2012.

- ^ "Tribal Museum". Government of Tamil Nadu. Archived from the original on 21 April 2024. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Tourist Guide to South India. South India. 2006. p. 96. ISBN 978-8-1747-8175-8.

- ^ "St. Stephen's Church". Government of Tamil Nadu. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Goodwin – Unsung Stenographer of Swami Vivekananda". The Hindu. 18 October 2013. Archived from the original on 29 July 2018. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ Thiagarajan, Shantha (9 October 2017). "St.Thomas Church Celebrates 150th Anniversary". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 5 January 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ "Tea museum". Government of Tamil Nadu. Archived from the original on 5 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "National Centre for Radio Astrophysics". Indian Space Statio. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- ^ "Sporting Vernacular 11. Snooker". The Independent. 26 April 1999. Archived from the original on 25 February 2007. Retrieved 25 February 2007.

- ^ D. Radhakrishnan (4 May 2011). "Lucky draw to mark Ooty racing milestone". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ "Ooty (Udagamandalam): Racecourse". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ^ Duttagupta, Ishani (19 September 2010). "Young & wealthy executives transforming the face of golfing". The Economic Times. Archived from the original on 15 October 2012. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ^ Nainar, Nahla (17 August 2018). "The journey of the famous Ooty 'varkey'". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Archived from the original on 26 December 2022. Retrieved 15 December 2023.

- ^ "The slowest train journey in India". BBC. 13 March 2023. Archived from the original on 14 February 2024. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Weeks, Stephen (1979). Decaying splendours: two palaces: reflections in an Indian mirror. University of California: British Broadcasting Corporation. ISBN 978-0-563-17516-2. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

External links

[edit] Ooty travel guide from Wikivoyage

Ooty travel guide from Wikivoyage