Hillary Clinton: Difference between revisions

→Whitewater and other investigations: WP:SUMMARY in preparation for WP:LIMIT editorial effort |

→Whitewater and other investigations: how about using the 'Details3' template, like this, to promote the detail articles but not chop the text up; also handles text without a detail article (Foster files) better |

||

| Line 146: | Line 146: | ||

=== Whitewater and other investigations === |

=== Whitewater and other investigations === |

||

{{Details3|[[Whitewater controversy]], [[Travelgate]], [[Filegate]], and [[Hillary Rodham cattle futures controversy]]|these investigations}} |

|||

{{Details|Whitewater controversy}} |

|||

The [[Whitewater controversy]] was the focus of media attention from the publication of a ''[[The New York Times|New York Times]]'' report during the 1992 presidential campaign,<ref name="nyt030892">{{Cite news |author=Gerth, Jeff |url=http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9E0CE5DD1F38F93BA35750C0A964958260 |title=Clintons Joined S.& L. Operator In an Ozark Real-Estate Venture |work=The New York Times |date=March 8, 1992 |authorlink=Jeff Gerth}}</ref> and throughout her time as First Lady. The Clintons had lost their late-1970s investment in the [[Whitewater Development Corporation]];<ref name="gerth-72">Gerth and Van Natta Jr. 2007, pp. 72–73.</ref> at the same time, their partners in that investment, [[Jim McDougal|Jim]] and [[Susan McDougal]], operated [[Madison Guaranty]], a [[savings and loan]] institution that retained the legal services of [[Rose Law Firm]]<ref name="gerth-72"/> and may have been improperly subsidizing Whitewater losses.<ref name="nyt030892"/> Madison Guaranty later failed, and Clinton's work at Rose was scrutinized for a possible conflict of interest in representing the bank before state regulators that her husband had appointed;<ref name="nyt030892"/> she claimed she had done minimal work for the bank.<ref name="cnn050696">{{Cite news |url=http://www.cnn.com/US/9604/13/whitewater.background/index.html |title=Whitewater started as 'sweetheart' deal |publisher=CNN |date=May 6, 1996 |accessdate=October 4, 2007}}</ref> [[Independent counsel]]s [[Robert B. Fiske|Robert Fiske]] and [[Kenneth Starr]] subpoenaed Clinton's legal billing records; she said she did not know where they were.<ref name="pbs100797"/><ref name="gerth-158"/> The records were found in the First Lady's White House book room after a two-year search, and delivered to investigators in early 1996.<ref name="gerth-158">Gerth and Van Natta Jr. 2007, pp. 158–160.</ref> The delayed appearance of the records sparked intense interest and another investigation about how they surfaced and where they had been;<ref name="gerth-158"/> Clinton's staff attributed the problem to continual changes in White House storage areas since the move from the Arkansas Governor's Mansion.<ref>{{Harvnb|Bernstein|2007|pp=441–442}}</ref> After the discovery of the records, on January 26, 1996, Clinton made history by becoming the first First Lady to be [[subpoena]]ed to testify before a Federal [[grand jury]].<ref name="pbs100797">{{Cite news |url=http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/arkansas/docs/recs.html |work=Once Upon a Time in Arkansas |title=Rose Law Firm Billing Records |publisher=[[Frontline (U.S. TV series)|Frontline]] |date=October 7, 1997 |accessdate=September 26, 2007}}</ref> After several Independent Counsels had investigated, a final report was issued in 2000 that stated there was insufficient evidence that either Clinton had engaged in criminal wrongdoing.<ref name=nyt092100/> |

The [[Whitewater controversy]] was the focus of media attention from the publication of a ''[[The New York Times|New York Times]]'' report during the 1992 presidential campaign,<ref name="nyt030892">{{Cite news |author=Gerth, Jeff |url=http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9E0CE5DD1F38F93BA35750C0A964958260 |title=Clintons Joined S.& L. Operator In an Ozark Real-Estate Venture |work=The New York Times |date=March 8, 1992 |authorlink=Jeff Gerth}}</ref> and throughout her time as First Lady. The Clintons had lost their late-1970s investment in the [[Whitewater Development Corporation]];<ref name="gerth-72">Gerth and Van Natta Jr. 2007, pp. 72–73.</ref> at the same time, their partners in that investment, [[Jim McDougal|Jim]] and [[Susan McDougal]], operated [[Madison Guaranty]], a [[savings and loan]] institution that retained the legal services of [[Rose Law Firm]]<ref name="gerth-72"/> and may have been improperly subsidizing Whitewater losses.<ref name="nyt030892"/> Madison Guaranty later failed, and Clinton's work at Rose was scrutinized for a possible conflict of interest in representing the bank before state regulators that her husband had appointed;<ref name="nyt030892"/> she claimed she had done minimal work for the bank.<ref name="cnn050696">{{Cite news |url=http://www.cnn.com/US/9604/13/whitewater.background/index.html |title=Whitewater started as 'sweetheart' deal |publisher=CNN |date=May 6, 1996 |accessdate=October 4, 2007}}</ref> [[Independent counsel]]s [[Robert B. Fiske|Robert Fiske]] and [[Kenneth Starr]] subpoenaed Clinton's legal billing records; she said she did not know where they were.<ref name="pbs100797"/><ref name="gerth-158"/> The records were found in the First Lady's White House book room after a two-year search, and delivered to investigators in early 1996.<ref name="gerth-158">Gerth and Van Natta Jr. 2007, pp. 158–160.</ref> The delayed appearance of the records sparked intense interest and another investigation about how they surfaced and where they had been;<ref name="gerth-158"/> Clinton's staff attributed the problem to continual changes in White House storage areas since the move from the Arkansas Governor's Mansion.<ref>{{Harvnb|Bernstein|2007|pp=441–442}}</ref> After the discovery of the records, on January 26, 1996, Clinton made history by becoming the first First Lady to be [[subpoena]]ed to testify before a Federal [[grand jury]].<ref name="pbs100797">{{Cite news |url=http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/arkansas/docs/recs.html |work=Once Upon a Time in Arkansas |title=Rose Law Firm Billing Records |publisher=[[Frontline (U.S. TV series)|Frontline]] |date=October 7, 1997 |accessdate=September 26, 2007}}</ref> After several Independent Counsels had investigated, a final report was issued in 2000 that stated there was insufficient evidence that either Clinton had engaged in criminal wrongdoing.<ref name=nyt092100/> |

||

| Line 154: | Line 154: | ||

Other investigations took place during Hillary Clinton's time as First Lady. |

Other investigations took place during Hillary Clinton's time as First Lady. |

||

Scrutiny of the May 1993 firings of the White House Travel Office employees, an affair that became known as "[[Travelgate]]", began with charges that the White House had used audited financial irregularities in the Travel Office operation as an excuse to replace the staff with friends from Arkansas.<ref>{{Harvnb|Bernstein|2007|pp=327–328}}</ref> The 1996 discovery of a two-year-old White House memo caused the investigation to focus more on whether Hillary Clinton had orchestrated the firings and whether the statements she made to investigators about her role in the firings were true.<ref>{{Harvnb|Bernstein|2007|pp=439–444}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |author=Johnson, David |title=Memo Places Hillary Clinton At Core of Travel Office Case|work=The New York Times|date=January 5, 1996 |url=http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9A0DE2DA1239F936A35752C0A960958260}}</ref> The 2000 final Independent Counsel report concluded she was involved in the firings and that she had made "factually false" statements, but that there was insufficient evidence that she knew the statements were false, or knew that her actions would lead to firings, to prosecute her.<ref>{{Cite news |author=Hughes, Jane |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/americas/802335.stm |title=Hillary escapes 'Travelgate' charges |publisher=BBC News |date=June 23, 2000 |accessdate=August 16, 2007}}</ref> |

|||

{{Main|Travelgate}} |

|||

Following deputy White House counsel [[Vince Foster]]'s July 1993 suicide, allegations were made that Hillary Clinton had ordered the removal of potentially damaging files (related to Whitewater or other matters) from Foster's office on the night of his death.<ref>{{Cite news |url=http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/whitewater/june96/senate_report_6-18.html |title=Opening the Flood Gates? |publisher=[[The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer|NewsHour]] |date=June 18, 1996 |accessdate=September 26, 2007}}</ref> Independent Counsel Kenneth Starr investigated this, and by 1999, Starr was reported to be holding the investigation open, despite his staff having told him there was no case to be made.<ref>{{Cite news |url=http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/politics/special/clinton/stories/shadow061599.htm |title=A Prosecutor Bound by Duty |author=Woodward, Bob |work=The Washington Post |date=June 15, 1999 |authorlink=Bob Woodward}}</ref> When Starr's successor [[Robert Ray (prosecutor)|Robert Ray]] issued his final Whitewater reports in 2000, no claims were made against Hillary Clinton regarding this.<ref name=nyt092100>{{Cite news |url=http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9E01E6DF103BF932A1575AC0A9669C8B63 |title=Statement by Independent Counsel on Conclusions in Whitewater Investigation |work=The New York Times |date=September 21, 2000 |accessdate=October 4, 2007}}</ref> |

|||

An outgrowth of the Travelgate investigation was the June 1996 discovery of improper White House access to hundreds of FBI background reports on former Republican White House employees, an affair that some called "[[Filegate]]".<ref name="cnn072800"/> Accusations were made that Hillary Clinton had requested these files and that she had recommended hiring an unqualified individual to head the White House Security Office.<ref>{{Cite news |url=http://www.cnn.com/ALLPOLITICS/1998/04/01/filegate/index.html |title='Filegate' Depositions Sought From White House Aides |publisher=CNN |date=April 1, 1998 |accessdate=September 26, 2007}}</ref> The 2000 final Independent Counsel report found no substantial or credible evidence that Hillary Clinton had any role or showed any misconduct in the matter.<ref name="cnn072800">{{Cite news |url=http://archives.cnn.com/2000/ALLPOLITICS/stories/07/28/clinton.filegate/ |title=Independent counsel: No evidence to warrant prosecution against first lady in 'filegate' |publisher=CNN |date=July 28, 2000 |accessdate=September 26, 2007}}</ref> |

An outgrowth of the Travelgate investigation was the June 1996 discovery of improper White House access to hundreds of FBI background reports on former Republican White House employees, an affair that some called "[[Filegate]]".<ref name="cnn072800"/> Accusations were made that Hillary Clinton had requested these files and that she had recommended hiring an unqualified individual to head the White House Security Office.<ref>{{Cite news |url=http://www.cnn.com/ALLPOLITICS/1998/04/01/filegate/index.html |title='Filegate' Depositions Sought From White House Aides |publisher=CNN |date=April 1, 1998 |accessdate=September 26, 2007}}</ref> The 2000 final Independent Counsel report found no substantial or credible evidence that Hillary Clinton had any role or showed any misconduct in the matter.<ref name="cnn072800">{{Cite news |url=http://archives.cnn.com/2000/ALLPOLITICS/stories/07/28/clinton.filegate/ |title=Independent counsel: No evidence to warrant prosecution against first lady in 'filegate' |publisher=CNN |date=July 28, 2000 |accessdate=September 26, 2007}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | In March 1994, newspaper reports revealed [[Hillary Rodham cattle futures controversy|her spectacular profits from cattle futures trading]] in 1978–1979;<ref>{{Cite news |url=http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9E01E2DB1F3DF93BA25750C0A962958260 |title=Top Arkansas Lawyer Helped Hillary Clinton Turn Big Profit |author=[[Jeff Gerth|Gerth, Jeff]]; and others |work=The New York Times |date=March 18, 1994}}</ref> allegations were made in the press of conflict of interest and disguised bribery,<ref name="wsj102600"/> and several individuals analyzed her trading records, but no formal investigation was made and she was never charged with any wrongdoing.<ref name="wsj102600">{{Cite news |author=Rosett, Claudia |url=http://www.opinionjournal.com/columnists/cRosett/?id=65000476 |title=Hillary's Bull Market |work=The Wall Street Journal |date=October 26, 2000 |accessdate=July 14, 2007 |authorlink=Claudia Rosett}}</ref> |

||

{{Main|Hillary Rodham cattle futures controversy}} |

|||

| ⚫ | In March 1994 newspaper reports revealed [[Hillary Rodham cattle futures controversy|her spectacular profits from cattle futures trading]] in 1978–1979;<ref>{{Cite news |url=http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9E01E2DB1F3DF93BA25750C0A962958260 |title=Top Arkansas Lawyer Helped Hillary Clinton Turn Big Profit |author=[[Jeff Gerth|Gerth, Jeff]]; and others |work=The New York Times |date=March 18, 1994}}</ref> allegations were made in the press of conflict of interest and disguised bribery,<ref name="wsj102600"/> and several individuals analyzed her trading records, but no formal investigation was made and she was never charged with any wrongdoing.<ref name="wsj102600">{{Cite news |author=Rosett, Claudia |url=http://www.opinionjournal.com/columnists/cRosett/?id=65000476 |title=Hillary's Bull Market |work=The Wall Street Journal |date=October 26, 2000 |accessdate=July 14, 2007 |authorlink=Claudia Rosett}}</ref> |

||

Some believed the Independent Counsels were politically motivated.<ref>{{cite news |last=Bennet |first=James |authorlink=James Bennet |newspaper=[[New York Times]] |title=News leaks prompt lawyer to seek sanctions against Starr's Office |accessdate=2012-02-05}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.huffingtonpost.com/joseph-a-palermo/the-starr-report-how-to-_b_71821.html |title=The Starr Report: How To Impeach A President (Repeat) |work=Huffington Post |accessdate=2012-02-05 |last=Palermo |first=Joseph A. |authorlink=Joseph Palermo |date=March 28, 2008}}</ref> |

Some believed the Independent Counsels were politically motivated.<ref>{{cite news |last=Bennet |first=James |authorlink=James Bennet |newspaper=[[New York Times]] |title=News leaks prompt lawyer to seek sanctions against Starr's Office |accessdate=2012-02-05}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.huffingtonpost.com/joseph-a-palermo/the-starr-report-how-to-_b_71821.html |title=The Starr Report: How To Impeach A President (Repeat) |work=Huffington Post |accessdate=2012-02-05 |last=Palermo |first=Joseph A. |authorlink=Joseph Palermo |date=March 28, 2008}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 11:26, 7 February 2012

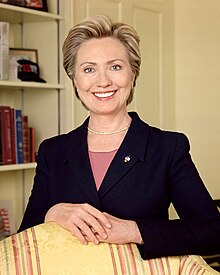

Hillary Rodham Clinton | |

|---|---|

| |

| 67th United States Secretary of State | |

| Assumed office January 21, 2009 | |

| President | Barack Obama |

| Deputy | James Steinberg (2009-2011) William Burns (2011-present) |

| Preceded by | Condoleezza Rice |

| United States Senator from New York | |

| In office January 3, 2001 – January 21, 2009 | |

| Preceded by | Daniel Patrick Moynihan |

| Succeeded by | Kirsten Gillibrand |

| First Lady of the United States | |

| In office January 20, 1993 – January 20, 2001 | |

| Preceded by | Barbara Bush |

| Succeeded by | Laura Bush |

| First Lady of Arkansas | |

| In office January 11, 1983 – December 12, 1992 | |

| Preceded by | Gay Daniels White |

| Succeeded by | Betty Tucker |

| In office January 9, 1979 – January 19, 1981 | |

| Preceded by | Barbara Pryor |

| Succeeded by | Gay Daniels White |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Hillary Diane Rodham October 26, 1947 Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | Bill Clinton |

| Relations | Hugh E. Rodham (father, deceased) Dorothy Howell Rodham (mother, deceased) Hugh Rodham (brother) Tony Rodham (brother) |

| Children | Chelsea |

| Residence(s) | Chappaqua, New York, United States |

| Alma mater | Wellesley College (B.A.) Yale Law School (J.D.) |

| Profession | Lawyer |

| Signature | |

| Website | Official website |

Template:HillaryRodhamClintonSegmentsUnderInfoBox Hillary Diane Rodham Clinton (/[invalid input: 'icon']ˈhɪləri daɪˈæn ˈrɒdəm ˈklɪntən/; born October 26, 1947) is the 67th United States Secretary of State, serving in the administration of President Barack Obama. She was a United States Senator for New York from 2001 to 2009. As the wife of the 42nd President of the United States, Bill Clinton, she was the First Lady of the United States from 1993 to 2001. In the 2008 election, Clinton was a leading candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination.

A native of Illinois, Hillary Rodham first attracted national attention in 1969 for her remarks as the first student commencement speaker at Wellesley College. She embarked on a career in law after graduating from Yale Law School in 1973. Following a stint as a Congressional legal counsel, she moved to Arkansas in 1974 and married Bill Clinton in 1975. Rodham cofounded the Arkansas Advocates for Children and Families in 1977 and became the first female chair of the Legal Services Corporation in 1978. Named the first female partner at Rose Law Firm in 1979, she was twice listed as one of the 100 most influential lawyers in America. First Lady of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and 1983 to 1992 with husband Bill as Governor, she successfully led a task force to reform Arkansas's education system. She sat on the board of directors of Wal-Mart and several other corporations.

In 1994 as First Lady of the United States, her major initiative, the Clinton health care plan, failed to gain approval from the U.S. Congress. However, in 1997 and 1999, Clinton played a role in advocating the creation of the State Children's Health Insurance Program, the Adoption and Safe Families Act, and the Foster Care Independence Act. Her years as First Lady drew a polarized response from the American public. The only First Lady to have been subpoenaed, she testified before a federal grand jury in 1996 due to the Whitewater controversy, but was never charged with wrongdoing in this or several other investigations during her husband's administration. The state of her marriage was the subject of considerable speculation following the Lewinsky scandal in 1998.

After moving to the state of New York, Clinton was elected as a U.S. Senator in 2000. That election marked the first time an American First Lady had run for public office; Clinton was also the first female senator to represent the state. In the Senate, she initially supported the Bush administration on some foreign policy issues, including a vote for the Iraq War Resolution. She subsequently opposed the administration on its conduct of the war in Iraq and on most domestic issues. Senator Clinton was reelected by a wide margin in 2006. In the 2008 presidential nomination race, Hillary Clinton won more primaries and delegates than any other female candidate in American history, but narrowly lost to Illinois Senator Barack Obama.

As Secretary of State, Clinton became the first former First Lady to serve in a president's cabinet. She has put into place institutional changes seeking to maximize departmental effectiveness and promote the empowerment of women worldwide, and has set records for most-traveled secretary for time in office. She has been at the forefront of the U.S. response to the Arab Spring, including advocating for the military intervention in Libya. She has used "smart power" as the strategy for asserting U.S. leadership and values in the world and has championed the use of social media in getting the U.S. message out.

Early life and education

Early life

Hillary Diane Rodham[nb 1] was born at Edgewater Hospital in Chicago, Illinois.[1][2] She was raised in a United Methodist family, first in Chicago and then, from the age of three, in suburban Park Ridge, Illinois.[3] Her father, Hugh Ellsworth Rodham (1911–1993), was the son of Welsh and English immigrants;[4] he managed a successful small business in the textile industry.[5] Her mother, Dorothy Emma Howell (1919–2011), was a homemaker of English, Scottish, French, French Canadian, and Welsh descent.[4][6] Hillary grew up with two younger brothers, Hugh and Tony.

As a child, Hillary Rodham was a teacher's favorite at her public schools in Park Ridge.[7][8] She participated in swimming, baseball, and other sports.[7][8] She also earned numerous awards as a Brownie and Girl Scout.[8] She attended Maine East High School, where she participated in student council, the school newspaper, and was selected for National Honor Society.[1][9] For her senior year, she was redistricted to Maine South High School, where she was a National Merit Finalist and graduated in the top five percent of her class of 1965.[9][10] Her mother wanted her to have an independent, professional career,[6] and her father, otherwise a traditionalist, was of the opinion that his daughter's abilities and opportunities should not be limited by gender.[11]

Raised in a politically conservative household,[6] at age thirteen Rodham helped canvass South Side Chicago following the very close 1960 U.S. presidential election, where she found evidence of electoral fraud against Republican candidate Richard Nixon.[12] She then volunteered to campaign for Republican candidate Barry Goldwater in the U.S. presidential election of 1964.[13] Rodham's early political development was shaped most by her high school history teacher (like her father, a fervent anticommunist), who introduced her to Goldwater's classic The Conscience of a Conservative,[14] and by her Methodist youth minister (like her mother, concerned with issues of social justice), with whom she saw and met civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr., in Chicago in 1962.[15]

Wellesley College years

In 1965, Rodham enrolled at Wellesley College, where she majored in political science.[16] During her freshman year, she served as president of the Wellesley Young Republicans;[17][18] with this Rockefeller Republican-oriented group,[19] she supported the elections of John Lindsay and Edward Brooke.[20] She later stepped down from this position, as her views changed regarding the American Civil Rights Movement and the Vietnam War.[17] In a letter to her youth minister at this time, she described herself as "a mind conservative and a heart liberal."[21] In contrast to the 1960s current that advocated radical actions against the political system, she sought to work for change within it.[22] In her junior year, Rodham became a supporter of the antiwar presidential nomination campaign of Democrat Eugene McCarthy.[23] Following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., Rodham organized a two-day student strike and worked with Wellesley's black students to recruit more black students and faculty.[23] In early 1968, she was elected president of the Wellesley College Government Association and served through early 1969;[22][24] she was instrumental in keeping Wellesley from being embroiled in the student disruptions common to other colleges.[22] A number of her fellow students thought she might some day become the first woman President of the United States.[22] So she could better understand her changing political views, Professor Alan Schechter assigned Rodham to intern at the House Republican Conference, and she attended the "Wellesley in Washington" summer program.[23] Rodham was invited by moderate New York Republican Representative Charles Goodell to help Governor Nelson Rockefeller’s late-entry campaign for the Republican nomination.[23] Rodham attended the 1968 Republican National Convention in Miami. However, she was upset by how Richard Nixon's campaign portrayed Rockefeller and by what she perceived as the convention's "veiled" racist messages, and left the Republican Party for good.[23]

Rodham wrote her senior thesis, a critique of the tactics of radical community organizer Saul Alinsky, under Professor Schechter.[25] (Years later, while she was First Lady, access to the thesis was restricted at the request of the White House and it became the subject of some speculation.)[25]

In 1969, she graduated with a Bachelor of Arts,[26] with departmental honors in political science.[25] Following pressure from some fellow students,[27] she became the first student in Wellesley College history to deliver its commencement address.[24] Her speech received a standing ovation lasting seven minutes.[22][28][29] She was featured in an article published in Life magazine,[30] due to the response to a part of her speech that criticized Senator Edward Brooke, who had spoken before her at the commencement.[27] She also appeared on Irv Kupcinet's nationally syndicated television talk show as well as in Illinois and New England newspapers.[31] That summer, she worked her way across Alaska, washing dishes in Mount McKinley National Park and sliming salmon in a fish processing cannery in Valdez (which fired her and shut down overnight when she complained about unhealthy conditions).[32]

Yale Law School and postgraduate studies

Rodham then entered Yale Law School, where she served on the editorial board of the Yale Review of Law and Social Action.[33] During her second year, she worked at the Yale Child Study Center,[34] learning about new research on early childhood brain development and working as a research assistant on the seminal work, Beyond the Best Interests of the Child (1973).[35][36] She also took on cases of child abuse at Yale-New Haven Hospital[35] and volunteered at New Haven Legal Services to provide free legal advice for the poor.[34] In the summer of 1970, she was awarded a grant to work at Marian Wright Edelman's Washington Research Project, where she was assigned to Senator Walter Mondale's Subcommittee on Migratory Labor. There she researched migrant workers' problems in housing, sanitation, health and education.[37] Edelman later became a significant mentor.[38] Rodham was recruited by political advisor Anne Wexler to work on the 1970 campaign of Connecticut U.S. Senate candidate Joseph Duffey, with Rodham later crediting Wexler with providing her first job in politics.[39]

In the late spring of 1971, she began dating Bill Clinton, also a law student at Yale. That summer, she interned at the Oakland, California, law firm of Treuhaft, Walker and Burnstein.[40] The firm was well known for its support of constitutional rights, civil liberties, and radical causes (two of its four partners were current or former Communist Party members);[40] Rodham worked on child custody and other cases.[nb 2] Clinton canceled his original summer plans, in order to live with her in California;[41] the couple continued living together in New Haven when they returned to law school.[42] The following summer, Rodham and Clinton campaigned in Texas for unsuccessful 1972 Democratic presidential candidate George McGovern.[43] She received a Juris Doctor degree from Yale in 1973,[26] having stayed on an extra year to be with Clinton.[44] Clinton first proposed marriage to her following graduation, but she declined.[44]

Rodham began a year of postgraduate study on children and medicine at the Yale Child Study Center.[45] Her first scholarly article, "Children Under the Law", was published in the Harvard Educational Review in late 1973.[46] Discussing the new children's rights movement, it stated that "child citizens" were "powerless individuals"[47] and argued that children should not be considered equally incompetent from birth to attaining legal age, but that instead courts should presume competence except when there is evidence otherwise, on a case-by-case basis.[48] The article became frequently cited in the field.[49]

Marriage and family, law career and First Lady of Arkansas

From the East Coast to Arkansas

During her postgraduate study, Rodham served as staff attorney for Edelman's newly founded Children's Defense Fund in Cambridge, Massachusetts,[50] and as a consultant to the Carnegie Council on Children.[51] During 1974, she was a member of the impeachment inquiry staff in Washington, D.C., advising the House Committee on the Judiciary during the Watergate scandal.[52] Under the guidance of Chief Counsel John Doar and senior member Bernard Nussbaum,[35] Rodham helped research procedures of impeachment and the historical grounds and standards for impeachment.[52] The committee's work culminated in the resignation of President Richard Nixon in August 1974.[52]

By then, Rodham was viewed as someone with a bright political future; Democratic political organizer and consultant Betsey Wright had moved from Texas to Washington the previous year to help guide her career;[53] Wright thought Rodham had the potential to become a future senator or president.[54] Meanwhile, Clinton had repeatedly asked her to marry him, and she continued to demur.[55] However, after failing the District of Columbia bar exam[56] and passing the Arkansas exam, Rodham came to a key decision. As she later wrote, "I chose to follow my heart instead of my head".[57] She thus followed Bill Clinton to Arkansas, rather than staying in Washington where career prospects were brighter. He was then teaching law and running for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives in his home state. In August 1974, Rodham moved to Fayetteville, Arkansas, and became one of only two female faculty members in the School of Law at the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville.[58][59] She gave classes in criminal law, where she was considered a rigorous teacher and tough grader, and was the first director of the school's legal aid clinic.[60] She still harbored doubts about marriage, concerned that her separate identity would be lost and that her accomplishments would be viewed in the light of someone else's.[61]

Early Arkansas years

Hillary Rodham and Bill Clinton bought a house in Fayetteville in the summer of 1975, and Hillary finally agreed to marry.[63] Their wedding took place on October 11, 1975, in a Methodist ceremony in their living room.[64] She announced she was keeping the name Hillary Rodham,[64] to keep their professional lives separate and avoid apparent conflicts of interest and because "it showed that I was still me,"[65] although her decision upset their mothers.[66] Bill Clinton had lost the congressional race in 1974, but in November 1976 was elected Arkansas Attorney General, and so the couple moved to the state capital of Little Rock.[67] There, in February 1977, Rodham joined the venerable Rose Law Firm, a bastion of Arkansan political and economic influence.[68] She specialized in patent infringement and intellectual property law[33] while also working pro bono in child advocacy;[69] she rarely performed litigation work in court.[70]

Rodham maintained her interest in children's law and family policy, publishing the scholarly articles "Children's Policies: Abandonment and Neglect" in 1977[71] and "Children's Rights: A Legal Perspective" in 1979.[72] The latter continued her argument that children's legal competence depended upon their age and other circumstances and that in serious medical rights cases, judicial intervention was sometimes warranted.[48] An American Bar Association chair later said, "Her articles were important, not because they were radically new but because they helped formulate something that had been inchoate."[48] Historian Garry Wills would later describe her as "one of the more important scholar-activists of the last two decades",[73] while conservatives said her theories would usurp traditional parental authority,[74] allow children to file frivolous lawsuits against their parents,[48] and argued that her work was legal "crit" theory run amok.[75]

In 1977, Rodham cofounded the Arkansas Advocates for Children and Families, a state-level alliance with the Children's Defense Fund.[33][76] Later that year, President Jimmy Carter (for whom Rodham had been the 1976 campaign director of field operations in Indiana)[77] appointed her to the board of directors of the Legal Services Corporation,[78] and she served in that capacity from 1978 until the end of 1981.[79] From mid-1978 to mid-1980,[nb 3] she served as the chair of that board, the first woman to do so.[80] During her time as chair, funding for the Corporation was expanded from $90 million to $300 million; subsequently she successfully fought President Ronald Reagan's attempts to reduce the funding and change the nature of the organization.[69]

Following her husband's November 1978 election as Governor of Arkansas, Rodham became First Lady of Arkansas in January 1979, her title for twelve years (1979–1981, 1983–1992). Clinton appointed her chair of the Rural Health Advisory Committee the same year,[81] where she successfully secured federal funds to expand medical facilities in Arkansas's poorest areas without affecting doctors' fees.[82]

In 1979, Rodham became the first woman to be made a full partner of Rose Law Firm.[83] From 1978 until they entered the White House, she had a higher salary than that of her husband.[84] During 1978 and 1979, while looking to supplement their income, Rodham made a spectacular profit from trading cattle futures contracts;[85] an initial $1,000 investment generated nearly $100,000 when she stopped trading after ten months.[86] The couple also began their ill-fated investment in the Whitewater Development Corporation real estate venture with Jim and Susan McDougal at this time.[85]

On February 27, 1980, Rodham gave birth to a daughter, Chelsea, her only child. In November 1980, Bill Clinton was defeated in his bid for reelection.

Later Arkansas years

Bill Clinton returned to the governor's office two years later by winning the election of 1982. During her husband's campaign, Rodham began to use the name Hillary Clinton, or sometimes "Mrs. Bill Clinton", to assuage the concerns of Arkansas voters;[nb 4] she also took a leave of absence from Rose Law to campaign for him full-time.[87] As First Lady of Arkansas, Hillary Clinton was named chair of the Arkansas Educational Standards Committee in 1983, where she sought to reform the state's court-sanctioned public education system.[88][89] In one of the Clinton governorship's most important initiatives, she fought a prolonged but ultimately successful battle against the Arkansas Education Association, to establish mandatory teacher testing and state standards for curriculum and classroom size.[81][88] In 1985, she also introduced Arkansas's Home Instruction Program for Preschool Youth, a program that helps parents work with their children in preschool preparedness and literacy.[90] She was named Arkansas Woman of the Year in 1983 and Arkansas Mother of the Year in 1984.[91][92]

Clinton continued to practice law with the Rose Law Firm while she was First Lady of Arkansas. She earned less than the other partners, as she billed fewer hours,[93] but still made more than $200,000 in her final year there.[94] She seldom did trial work,[94] but the firm considered her a "rainmaker" because she brought in clients, partly thanks to the prestige she lent the firm and to her corporate board connections.[94] She was also very influential in the appointment of state judges.[94] Bill Clinton's Republican opponent in his 1986 gubernatorial reelection campaign accused the Clintons of conflict of interest, because Rose Law did state business; the Clintons deflected the charge by saying that state fees were walled off by the firm before her profits were calculated.[95]

From 1982 to 1988, Clinton was on the board of directors, sometimes as chair, of the New World Foundation,[96] which funded a variety of New Left interest groups.[97] From 1987 to 1991, she chaired the American Bar Association's Commission on Women in the Profession,[98] which addressed gender bias in the law profession and induced the association to adopt measures to combat it.[98] She was twice named by the National Law Journal as one of the 100 most influential lawyers in America: in 1988 and in 1991.[99] When Bill Clinton thought about not running again for governor in 1990, Hillary considered running, but private polls were unfavorable and, in the end, he ran and was reelected for the final time.[100]

Clinton served on the boards of the Arkansas Children's Hospital Legal Services (1988–1992)[101] and the Children's Defense Fund (as chair, 1986–1992).[1][102] In addition to her positions with nonprofit organizations, she also held positions on the corporate board of directors of TCBY (1985–1992),[103] Wal-Mart Stores (1986–1992)[104] and Lafarge (1990–1992).[105] TCBY and Wal-Mart were Arkansas-based companies that were also clients of Rose Law.[94][106] Clinton was the first female member on Wal-Mart's board, added following pressure on chairman Sam Walton to name a woman to the board.[106] Once there, she pushed successfully for Wal-Mart to adopt more environmentally friendly practices, was largely unsuccessful in a campaign for more women to be added to the company's management, and was silent about the company's famously anti-labor union practices.[104][106][107]

Bill Clinton presidential campaign of 1992

Hillary Clinton received sustained national attention for the first time when her husband became a candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination of 1992. Before the New Hampshire primary, tabloid publications printed claims that Bill Clinton had had an extramarital affair with Arkansas lounge singer Gennifer Flowers.[108] In response, the Clintons appeared together on 60 Minutes, where Bill Clinton denied the affair but acknowledged "causing pain in my marriage."[109] This joint appearance was credited with rescuing his campaign.[110] During the campaign, Hillary Clinton made culturally disparaging remarks about Tammy Wynette and her outlook on marriage,[nb 5] and about women staying home and baking cookies and having teas,[nb 6] that were ill-considered by her own admission. Bill Clinton said that in electing him, the nation would "get two for the price of one", referring to the prominent role his wife would assume.[111] Beginning with Daniel Wattenberg's August 1992 The American Spectator article "The Lady Macbeth of Little Rock", Hillary Clinton's own past ideological and ethical record came under conservative attack.[74] At least twenty other articles in major publications also drew comparisons between her and Lady Macbeth.[112]

First Lady of the United States

Role as First Lady

When Bill Clinton took office as president in January 1993, Hillary Rodham Clinton became the First Lady of the United States, and announced that she would be using that form of her name.[113] She was the first First Lady to hold a postgraduate degree[114] and to have her own professional career up to the time of entering the White House.[114] She was also the first to have an office in the West Wing of the White House in addition to the usual First Lady offices in the East Wing.[45][115] She was part of the innermost circle vetting appointments to the new administration, and her choices filled at least eleven top-level positions and dozens more lower-level ones.[116] She is regarded as the most openly empowered presidential wife in American history, save for Eleanor Roosevelt.[117][118]

Some critics called it inappropriate for the First Lady to play a central role in matters of public policy. Supporters pointed out that Clinton's role in policy was no different from that of other White House advisors and that voters were well aware that she would play an active role in her husband's presidency.[119] Bill Clinton's campaign promise of "two for the price of one" led opponents to refer derisively to the Clintons as "co-presidents",[120] or sometimes the Arkansas label "Billary".[81][121] The pressures of conflicting ideas about the role of a First Lady were enough to send Clinton into "imaginary discussions" with the also-politically-active Eleanor Roosevelt.[nb 7] From the time she came to Washington, she also found refuge in a prayer group of The Fellowship that featured many wives of conservative Washington figures.[122][123] Triggered in part by the death of her father in April 1993, she publicly sought to find a synthesis of Methodist teachings, liberal religious political philosophy, and Tikkun editor Michael Lerner's "politics of meaning" to overcome what she saw as America's "sleeping sickness of the soul" and that would lead to a willingness "to remold society by redefining what it means to be a human being in the twentieth century, moving into a new millennium."[124][125] Other segments of the public focused on her appearance, which had evolved over time from inattention to fashion during her days in Arkansas,[126] to a popular site in the early days of the World Wide Web devoted to showing her many different, and frequently analyzed, hairstyles as First Lady,[127][128] to an appearance on the cover of Vogue magazine in 1998.[129]

Health care and other policy initiatives

In January 1993, Bill Clinton appointed Hillary Clinton to head the Task Force on National Health Care Reform, hoping to replicate the success she had in leading the effort for Arkansas education reform.[131] She privately urged that passage of health care reform be given higher priority than the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) (which she was also unenthusiastic about the merits of).[132][133] The recommendation of the task force became known as the Clinton health care plan, a comprehensive proposal that would require employers to provide health coverage to their employees through individual health maintenance organizations. Its opponents quickly derided the plan as "Hillarycare"; some protesters against it became vitriolic, and during a July 1994 bus tour to rally support for the plan, she was forced to wear a bulletproof vest at times.[134][135]

The plan did not receive enough support for a floor vote in either the House or the Senate, although Democrats controlled both chambers, and the proposal was abandoned in September 1994.[134] Clinton later acknowledged in her book, Living History, that her political inexperience partly contributed to the defeat, but mentioned that many other factors were also responsible. The First Lady's approval ratings, which had generally been in the high-50s percent range during her first year, fell to 44 percent in April 1994 and 35 percent by September 1994.[136] Republicans made the Clinton health care plan a major campaign issue of the 1994 midterm elections,[137] which saw a net Republican gain of fifty-three seats in the House election and seven in the Senate election, winning control of both; many analysts and pollsters found the plan to be a major factor in the Democrats' defeat, especially among independent voters.[138] The White House subsequently sought to downplay Hillary Clinton's role in shaping policy.[139] Opponents of universal health care would continue to use "Hillarycare" as a pejorative label for similar plans by others.[140]

Along with Senators Ted Kennedy and Orrin Hatch, she was a force behind the passage of the State Children's Health Insurance Program in 1997, a federal effort that provided state support for children whose parents could not provide them with health coverage, and conducted outreach efforts on behalf of enrolling children in the program once it became law.[141] She promoted nationwide immunization against childhood illnesses and encouraged older women to seek a mammogram to detect breast cancer, with coverage provided by Medicare.[142] She successfully sought to increase research funding for prostate cancer and childhood asthma at the National Institutes of Health.[45] The First Lady worked to investigate reports of an illness that affected veterans of the Gulf War, which became known as the Gulf War syndrome.[45] Together with Attorney General Janet Reno, Clinton helped create the Office on Violence Against Women at the Department of Justice.[45] In 1997, she initiated and shepherded the Adoption and Safe Families Act, which she regarded as her greatest accomplishment as First Lady.[45][143] In 1999, she was instrumental in the passage of the Foster Care Independence Act, which doubled federal monies for teenagers aging out of foster care.[143] As First Lady, Clinton hosted numerous White House conferences, including ones on Child Care (1997),[144] on Early Childhood Development and Learning (1997),[145] and on Children and Adolescents (2000).[146] She also hosted the first-ever White House Conference on Teenagers (2000)[147] and the first-ever White House Conference on Philanthropy (1999).[148]

Clinton traveled to 79 countries during this time,[149] breaking the mark for most-traveled First Lady held by Pat Nixon.[150] She did not hold a security clearance or attend National Security Council meetings, but played a soft power role in U.S. diplomacy.[151] A March 1995 five-nation trip to South Asia, on behest of the U.S. State Department and without her husband, sought to improve relations with India and Pakistan.[152] Clinton was troubled by the plight of women she encountered, but found a warm response from the people of the countries she visited and a gained better relationship with the American press corps.[152][153] The trip was a transformative experience for her and presaged her eventual career in diplomacy.[154] In a September 1995 speech before the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing, Clinton argued very forcefully against practices that abused women around the world and in the People's Republic of China itself,[155] declaring "that it is no longer acceptable to discuss women's rights as separate from human rights".[155] Delegates from over 180 countries heard her say: "If there is one message that echoes forth from this conference, let it be that human rights are women's rights and women's rights are human rights, once and for all."[156] In doing so, she resisted both internal administration and Chinese pressure to soften her remarks.[149][156] She was one of the most prominent international figures during the late 1990s to speak out against the treatment of Afghan women by the Islamist fundamentalist Taliban.[157][158] She helped create Vital Voices, an international initiative sponsored by the United States to promote the participation of women in the political processes of their countries.[159] It and Clinton's own visits encouraged women to make themselves heard in the Northern Ireland peace process.[160]

Whitewater and other investigations

The Whitewater controversy was the focus of media attention from the publication of a New York Times report during the 1992 presidential campaign,[161] and throughout her time as First Lady. The Clintons had lost their late-1970s investment in the Whitewater Development Corporation;[162] at the same time, their partners in that investment, Jim and Susan McDougal, operated Madison Guaranty, a savings and loan institution that retained the legal services of Rose Law Firm[162] and may have been improperly subsidizing Whitewater losses.[161] Madison Guaranty later failed, and Clinton's work at Rose was scrutinized for a possible conflict of interest in representing the bank before state regulators that her husband had appointed;[161] she claimed she had done minimal work for the bank.[163] Independent counsels Robert Fiske and Kenneth Starr subpoenaed Clinton's legal billing records; she said she did not know where they were.[164][165] The records were found in the First Lady's White House book room after a two-year search, and delivered to investigators in early 1996.[165] The delayed appearance of the records sparked intense interest and another investigation about how they surfaced and where they had been;[165] Clinton's staff attributed the problem to continual changes in White House storage areas since the move from the Arkansas Governor's Mansion.[166] After the discovery of the records, on January 26, 1996, Clinton made history by becoming the first First Lady to be subpoenaed to testify before a Federal grand jury.[164] After several Independent Counsels had investigated, a final report was issued in 2000 that stated there was insufficient evidence that either Clinton had engaged in criminal wrongdoing.[167]

Other investigations took place during Hillary Clinton's time as First Lady.

Scrutiny of the May 1993 firings of the White House Travel Office employees, an affair that became known as "Travelgate", began with charges that the White House had used audited financial irregularities in the Travel Office operation as an excuse to replace the staff with friends from Arkansas.[168] The 1996 discovery of a two-year-old White House memo caused the investigation to focus more on whether Hillary Clinton had orchestrated the firings and whether the statements she made to investigators about her role in the firings were true.[169][170] The 2000 final Independent Counsel report concluded she was involved in the firings and that she had made "factually false" statements, but that there was insufficient evidence that she knew the statements were false, or knew that her actions would lead to firings, to prosecute her.[171]

Following deputy White House counsel Vince Foster's July 1993 suicide, allegations were made that Hillary Clinton had ordered the removal of potentially damaging files (related to Whitewater or other matters) from Foster's office on the night of his death.[172] Independent Counsel Kenneth Starr investigated this, and by 1999, Starr was reported to be holding the investigation open, despite his staff having told him there was no case to be made.[173] When Starr's successor Robert Ray issued his final Whitewater reports in 2000, no claims were made against Hillary Clinton regarding this.[167]

An outgrowth of the Travelgate investigation was the June 1996 discovery of improper White House access to hundreds of FBI background reports on former Republican White House employees, an affair that some called "Filegate".[174] Accusations were made that Hillary Clinton had requested these files and that she had recommended hiring an unqualified individual to head the White House Security Office.[175] The 2000 final Independent Counsel report found no substantial or credible evidence that Hillary Clinton had any role or showed any misconduct in the matter.[174]

In March 1994, newspaper reports revealed her spectacular profits from cattle futures trading in 1978–1979;[176] allegations were made in the press of conflict of interest and disguised bribery,[177] and several individuals analyzed her trading records, but no formal investigation was made and she was never charged with any wrongdoing.[177]

Some believed the Independent Counsels were politically motivated.[178][179]

Lewinsky scandal

In 1998, the Clintons' relationship became the subject of much speculation when investigations revealed that the President had had extramarital relations with White House intern Monica Lewinsky.[180] Events surrounding the Lewinsky scandal eventually led to the impeachment of Bill Clinton by the House of Representatives. When the allegations against her husband were first made public, Hillary Clinton stated that they were the result of a "vast right-wing conspiracy",[181] characterizing the Lewinsky charges as the latest in a long, organized, collaborative series of charges by Bill Clinton's political enemies[nb 8] rather than any wrongdoing by her husband. She later said that she had been misled by her husband's initial claims that no affair had taken place.[182] After the evidence of President Clinton's encounters with Lewinsky became incontrovertible, she issued a public statement reaffirming her commitment to their marriage,[183] but privately was reported to be furious at him[184] and was unsure if she wanted to stay in the marriage.[185]

There was a variety of public reactions to Hillary Clinton after this: some women admired her strength and poise in private matters made public, some sympathized with her as a victim of her husband's insensitive behavior, others criticized her as being an enabler to her husband's indiscretions, while still others accused her of cynically staying in a failed marriage as a way of keeping or even fostering her own political influence.[186] Her public approval ratings in the wake of the revelations shot upward to around 70 percent, the highest they had ever been.[186] In her 2003 memoir, she would attribute her decision to stay married to "a love that has persisted for decades" and add: "No one understands me better and no one can make me laugh the way Bill does. Even after all these years, he is still the most interesting, energizing and fully alive person I have ever met."[187]

Traditional duties

Clinton initiated and was Founding Chair of the Save America's Treasures program, a national effort that matched federal funds to private donations to preserve and restore historic items and sites,[188] including the flag that inspired "The Star-Spangled Banner" and the First Ladies Historic Site in Canton, Ohio.[45] She was head of the White House Millennium Council,[189] and hosted Millennium Evenings,[190] a series of lectures that discussed futures studies, one of which became the first live simultaneous webcast from the White House.[45] Clinton also created the first White House Sculpture Garden, located in the Jacqueline Kennedy Garden, which displayed large contemporary American works of art loaned from museums.[191]

In the White House, Clinton placed donated handicrafts of contemporary American artisans, such as pottery and glassware, on rotating display in the state rooms.[45] She oversaw the restoration of the Blue Room to be historically authentic to the period of James Monroe,[192] the redecoration of the Treaty Room into the presidential study along 19th century lines,[193] and the redecoration of the Map Room to how it looked during World War II.[193] Clinton hosted many large-scale events at the White House, such as a Saint Patrick's Day reception, a state dinner for visiting Chinese dignitaries, a contemporary music concert that raised funds for music education in public schools, a New Year's Eve celebration at the turn of the 21st century, and a state dinner honoring the bicentennial of the White House in November 2000.[45]

Senate election of 2000

When the long-serving United States Senator from New York, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, announced his retirement in November 1998, several prominent Democratic figures, including Representative Charles B. Rangel of New York, urged Clinton to run for Moynihan's open seat in the United States Senate election of 2000.[194] Once she decided to run, the Clintons purchased a home in Chappaqua, New York, north of New York City, in September 1999.[195] She became the first First Lady of the United States to be a candidate for elected office.[196] Initially, Clinton expected to face Rudy Giuliani, the Mayor of New York City, as her Republican opponent in the election. However, Giuliani withdrew from the race in May 2000 after being diagnosed with prostate cancer and having developments in his personal life become very public, and Clinton instead faced Rick Lazio, a Republican member of the United States House of Representatives representing New York's 2nd congressional district. Throughout the campaign, opponents accused Clinton of carpetbagging, as she had never resided in New York nor participated in the state's politics before this race. Clinton began her campaign by visiting every county in the state, in a "listening tour" of small-group settings.[197] During the campaign, she devoted considerable time in traditionally Republican Upstate New York regions.[198] Clinton vowed to improve the economic situation in those areas, promising to deliver 200,000 jobs to the state over her term. Her plan included tax credits to reward job creation and encourage business investment, especially in the high-tech sector. She called for personal tax cuts for college tuition and long-term care.[198]

The contest drew national attention. Lazio blundered during a September debate by seeming to invade Clinton's personal space trying to get her to sign a fundraising agreement.[199] The campaigns of Clinton and Lazio, along with Giuliani's initial effort, spent a record combined $90 million.[200] Clinton won the election on November 7, 2000, with 55 percent of the vote to Lazio's 43 percent.[199] She was sworn in as United States Senator on January 3, 2001.

United States Senator

First term

Upon entering the Senate, Clinton maintained a low public profile and built relationships with senators from both parties.[201] She forged alliances with religiously inclined senators by becoming a regular participant in the Senate Prayer Breakfast.[122][202]

Clinton served on five Senate committees: Committee on Budget (2001–2002),[203] Committee on Armed Services (since 2003),[204] Committee on Environment and Public Works (since 2001),[203] Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions (since 2001)[203] and Special Committee on Aging.[205] She was also a Commissioner of the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe[206] (since 2001).[207]

Following the September 11, 2001, attacks, Clinton sought to obtain funding for the recovery efforts in New York City and security improvements in her state. Working with New York's senior senator, Charles Schumer, she was instrumental in quickly securing $21 billion in funding for the World Trade Center site's redevelopment.[202][208] She subsequently took a leading role in investigating the health issues faced by 9/11 first responders.[209] Clinton voted for the USA Patriot Act in October 2001. In 2005, when the act was up for renewal, she worked to address some of the civil liberties concerns with it,[210] before voting in favor of a compromise renewed act in March 2006 that gained large majority support.[211]

Clinton strongly supported the 2001 U.S. military action in Afghanistan, saying it was a chance to combat terrorism while improving the lives of Afghan women who suffered under the Taliban government.[212] Clinton voted in favor of the October 2002 Iraq War Resolution, which authorized United States President George W. Bush to use military force against Iraq, should such action be required to enforce a United Nations Security Council Resolution after pursuing with diplomatic efforts.

After the Iraq War began, Clinton made trips to Iraq and Afghanistan to visit American troops stationed there. On a visit to Iraq in February 2005, Clinton noted that the insurgency had failed to disrupt the democratic elections held earlier, and that parts of the country were functioning well.[213] Noting that war deployments were draining regular and reserve forces, she cointroduced legislation to increase the size of the regular United States Army by 80,000 soldiers to ease the strain.[214] In late 2005, Clinton said that while immediate withdrawal from Iraq would be a mistake, Bush's pledge to stay "until the job is done" was also misguided, as it gave Iraqis "an open-ended invitation not to take care of themselves."[215] Her stance caused frustration among those in the Democratic Party who favored immediate withdrawal.[216] Clinton supported retaining and improving health benefits for veterans, and lobbied against the closure of several military bases.[217]

Senator Clinton voted against President Bush's two major tax cut packages, the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001 and the Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003.[218] Clinton voted against the 2005 confirmation of John G. Roberts as Chief Justice of the United States and the 2006 confirmation of Samuel Alito to the United States Supreme Court.[219]

In 2005, Clinton called for the Federal Trade Commission to investigate how hidden sex scenes showed up in the controversial video game Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas.[220] Along with Senators Joe Lieberman and Evan Bayh, she introduced the Family Entertainment Protection Act, intended to protect children from inappropriate content found in video games. In 2004 and 2006, Clinton voted against the Federal Marriage Amendment that sought to prohibit same-sex marriage.[218][221]

Looking to establish a "progressive infrastructure" to rival that of American conservatism, Clinton played a formative role in conversations that led to the 2003 founding of former Clinton administration chief of staff John Podesta's Center for American Progress, shared aides with Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington, founded in 2003, and advised the Clintons' former antagonist David Brock's Media Matters for America, created in 2004.[222] Following the 2004 Senate elections, she successfully pushed new Democratic Senate leader Harry Reid to create a Senate war room to handle daily political messaging.[223]

Reelection campaign of 2006

In November 2004, Clinton announced that she would seek a second Senate term. The early frontrunner for the Republican nomination, Westchester County District Attorney Jeanine Pirro, withdrew from the contest after several months of poor campaign performance.[224] Clinton easily won the Democratic nomination over opposition from antiwar activist Jonathan Tasini.[225] Clinton's eventual opponents in the general election were Republican candidate John Spencer, a former mayor of Yonkers, along with several third-party candidates. She won the election on November 7, 2006, with 67 percent of the vote to Spencer's 31 percent,[226] carrying all but four of New York's sixty-two counties.[227] Clinton spent $36 million for her reelection, more than any other candidate for Senate in the 2006 elections did. Some Democrats criticized her for spending too much in a one-sided contest, while some supporters were concerned she did not leave more funds for a potential presidential bid in 2008.[228] In the following months, she transferred $10 million of her Senate funds toward her presidential campaign.[229]

Second term

Clinton opposed the Iraq War troop surge of 2007.[230] In March 2007, she voted in favor of a war-spending bill that required President Bush to begin withdrawing troops from Iraq by a deadline; it passed almost completely along party lines[231] but was subsequently vetoed by President Bush. In May 2007, a compromise war funding bill that removed withdrawal deadlines but tied funding to progress benchmarks for the Iraqi government passed the Senate by a vote of 80–14 and would be signed by Bush; Clinton was one of those who voted against it.[232] Clinton responded to General David Petraeus's September 2007 Report to Congress on the Situation in Iraq by saying, "I think that the reports that you provide to us really require a willing suspension of disbelief."[233]

In March 2007, in response to the dismissal of U.S. attorneys controversy, Clinton called on Attorney General Alberto Gonzales to resign.[234] In May and June 2007, regarding the high-profile, hotly debated comprehensive immigration reform bill known as the Secure Borders, Economic Opportunity and Immigration Reform Act of 2007, Clinton cast several votes in support of the bill, which eventually failed to gain cloture.[235]

As the financial crisis of 2007–2008 reached a peak with the liquidity crisis of September 2008, Clinton supported the proposed bailout of United States financial system, voting in favor of the $700 billion Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008, saying that it represented the interests of the American people.[236] It passed the Senate 74–25.

Presidential campaign of 2008

Clinton had been preparing for a potential candidacy for United States President since at least early 2003.[237] On January 20, 2007, Clinton announced via her web site the formation of a presidential exploratory committee for the United States presidential election of 2008; she stated, "I'm in, and I'm in to win."[238] No woman had ever been nominated by a major party for President of the United States. In April 2007, the Clintons liquidated a blind trust, that had been established when Bill Clinton became president in 1993, to avoid the possibility of ethical conflicts or political embarrassments in the trust as Hillary Clinton undertook her presidential race.[239] Later disclosure statements revealed that the couple's worth was now upwards of $50 million,[239] and that they had earned over $100 million since 2000, with most of it coming from Bill Clinton's books, speaking engagements, and other activities.[240]

Clinton led candidates competing for the Democratic nomination in opinion polls for the election throughout the first half of 2007. Most polls placed Senator Barack Obama of Illinois and former Senator John Edwards of North Carolina as Clinton's closest competitors.[241] Clinton and Obama both set records for early fundraising, swapping the money lead each quarter.[242] By September 2007, polling in the first six states holding Democratic primaries or caucuses showed that Clinton was leading in all of them, with the races being closest in Iowa and South Carolina. By the following month, national polls showed Clinton far ahead of Democratic competitors.[243] At the end of October, Clinton suffered a rare poor debate performance against Obama, Edwards, and her other opponents.[244][245][246] Obama's message of "change" began to resonate with the Democratic electorate better than Clinton's message of "experience".[247] The race tightened considerably, especially in the early caucus and primary states of Iowa, New Hampshire, and South Carolina, with Clinton losing her lead in some polls by December.[248]

In the first vote of 2008, she placed third in the January 3 Iowa Democratic caucus to Obama and Edwards.[249] Obama gained ground in national polling in the next few days, with all polls predicting a victory for him in the New Hampshire primary.[250][251] However, Clinton gained a surprise win there on January 8, defeating Obama narrowly.[252] Explanations for her New Hampshire comeback varied but often centered on her being seen more sympathetically, especially by women, after her eyes welled with tears and her voice broke while responding to a voter's question the day before the election.[252][253]

The nature of the contest fractured in the next few days. Several remarks by Bill Clinton and other surrogates,[254] and a remark by Hillary Clinton concerning Martin Luther King, Jr., and Lyndon B. Johnson,[nb 9] were perceived by many as, accidentally or intentionally, limiting Obama as a racially oriented candidate or otherwise denying the post-racial significance and accomplishments of his campaign.[255] Despite attempts by both Hillary Clinton and Obama to downplay the issue, Democratic voting became more polarized as a result, with Clinton losing much of her support among African Americans.[254][256] She lost by a two-to-one margin to Obama in the January 26 South Carolina primary,[257] setting up, with Edwards soon dropping out, an intense two-person contest for the twenty-two February 5 Super Tuesday states. Bill Clinton had made more statements attracting criticism for their perceived racial implications late in the South Carolina campaign, and his role was seen as damaging enough to her that a wave of supporters within and outside of the campaign said the former President "needs to stop."[258]

On Super Tuesday, Clinton won the largest states, such as California, New York, New Jersey and Massachusetts, while Obama won more states; they almost evenly split the total popular vote.[259][260] But Obama was gaining more pledged delegates for his share of the popular vote due to better exploitation of the Democratic proportional allocation rules.[261]

The Clinton campaign had counted on winning the nomination by Super Tuesday, and was unprepared financially and logistically for a prolonged effort; lagging in Internet fundraising, Clinton began loaning her campaign money.[247][262] There was continuous turmoil within the campaign staff and she made several top-level personnel changes.[262][263] Obama won the next eleven February caucuses and primaries across the country, often by large margins, and took a significant pledged delegate lead over Clinton.[261][262] On March 4, Clinton broke the string of losses by winning in Ohio among other places,[262] where her criticism of NAFTA, a major legacy of her husband's presidency, had been a key issue.[264] Throughout the campaign, Obama dominated caucuses, which the Clinton campaign largely ignored organizing for.[247][261][265] Obama did well in primaries where African Americans or younger, college-educated, or more affluent voters were heavily represented; Clinton did well in primaries where Hispanics or older, non-college-educated, or working-class white voters predominated.[266][267] Some Democratic party leaders expressed concern that the drawn-out campaign between the two could damage the winner in the general election contest against Republican presumptive nominee John McCain, especially if an eventual triumph for Clinton was won via party-appointed superdelegates.[268]

On April 22, she won the Pennsylvania primary, and kept her campaign alive.[270] However, on May 6, a narrower-than-expected win in the Indiana primary coupled with a large loss in the North Carolina primary ended any realistic chance she had of winning the nomination.[270] She vowed to stay on through the remaining primaries, but stopped attacks against Obama; as one advisor stated, "She could accept losing. She could not accept quitting."[270] She won some of the remaining contests, and indeed, over the last three months of the campaign she won more delegates, states, and votes than Obama, but it was not enough to overcome Obama's lead.[262]

Following the final primaries on June 3, 2008, Obama had gained enough delegates to become the presumptive nominee.[271] In a speech before her supporters on June 7, Clinton ended her campaign and endorsed Obama, declaring, "The way to continue our fight now to accomplish the goals for which we stand is to take our energy, our passion, our strength and do all we can to help elect Barack Obama."[272] By campaign's end, Clinton had won 1,640 pledged delegates to Obama's 1,763;[273] at the time of the clinching, Clinton had 286 superdelegates to Obama's 395,[274] with those numbers widening to 256 versus 438 once Obama was acknowledged the winner.[273] Clinton and Obama each received over 17 million votes during the nomination process,[nb 10] with both breaking the previous record.[275] Clinton also eclipsed, by a very large margin, Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm's 1972 mark for most primaries and delegates won by a woman.[276] Clinton gave a passionate speech supporting Obama at the 2008 Democratic National Convention and campaigned frequently for him in Fall 2008, which concluded with his victory over McCain in the general election on November 4.[277] Clinton's campaign ended up severely in debt; she owed millions of dollars to outside vendors and wrote off the $13 million that she lent it herself.[278]

Secretary of State

Nomination and confirmation

In mid-November 2008, President-elect Obama and Clinton discussed the possibility of her serving as U.S. Secretary of State in his administration,[279] and on November 21, reports indicated that she had accepted the position.[280] On December 1, President-elect Obama formally announced that Clinton would be his nominee for Secretary of State.[281] Clinton said she was reluctant to leave the Senate, but that the new position represented a "difficult and exciting adventure".[281] As part of the nomination and in order to relieve concerns of conflict of interest, Bill Clinton agreed to accept several conditions and restrictions regarding his ongoing activities and fundraising efforts for the Clinton Presidential Center and Clinton Global Initiative.[282]

The appointment required a Saxbe fix, passed and signed into law in December 2008.[283] Confirmation hearings before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee began on January 13, 2009, a week before the Obama inauguration; two days later, the Committee voted 16–1 to approve Clinton.[284] By this time, her public approval rating had reached 65 percent, the highest point since the Lewinsky scandal.[285] On January 21, 2009, Clinton was confirmed in the full Senate by a vote of 94–2.[286] Clinton took the oath of office of Secretary of State and resigned from the Senate that same day.[287] She became the first former First Lady to serve in the United States Cabinet.[288]

Tenure

Clinton spent her initial days as Secretary of State telephoning dozens of world leaders and indicating that U.S. foreign policy would change direction: "We have a lot of damage to repair."[289] She advocated an expanded role in global economic issues for the State Department and cited the need for an increased U.S. diplomatic presence, especially in Iraq where the Defense Department had conducted diplomatic missions.[290] She pushed for a larger international affairs budget;[290] the Obama administration's proposed 2010 budget contained a 7 percent increase for the State Department and other international programs.[291] In March 2009, Clinton prevailed over Vice President Joe Biden on an internal debate to send an additional 20,000 troops to the war in Afghanistan.[292] An elbow fracture and subsequent painful recuperation caused Clinton to miss two foreign trips in June 2009.[292][293]

Clinton announced the most ambitious of her departmental reforms, the Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review, which establishes specific objectives for the State Department’s diplomatic missions abroad; it is modeled after a similar process in the Defense Department that she was familiar with from her time on the Senate Armed Services Committee.[294] (The first such review was issued in late 2010 and called for the U.S. leading through "civilian power" as a cost-effective way of responding to international challenges and defusing crises.[295] It also sought to institutionalize goals of empowering women throughout the world.[156]) In September, Clinton unveiled the Global Hunger and Food Security Initiative at the annual meeting of her husband's Clinton Global Initiative.[296] The new initiative seeks to battle hunger worldwide as a strategic part of U.S. foreign policy, rather than just react to food shortage emergencies as they occur, and emphasizes the role of women farmers.[296] In October, on a trip to Switzerland, Clinton’s intervention overcame last-minute snags and saved the signing of an historic Turkish–Armenian accord that established diplomatic relations and opened the border between the two long-hostile nations.[297][298] In Pakistan, she engaged in several unusually blunt discussions with students, talk show hosts, and tribal elders, in an attempt to repair the Pakistani image of the U.S.[154]

In a major speech in January 2010, Clinton drew analogies between the Iron Curtain and the free and unfree Internet.[299] Chinese officials reacted negatively towards it, and it garnered attention as the first time a senior American official had clearly defined the Internet as a key element of American foreign policy.[300] By mid-2010, Clinton and Obama had forged a good working relationship; she was a team player within the administration and a defender of it to the outside, and was careful that neither she nor her husband would upstage him.[301] She met with him weekly, but did not have the close, daily relationship that some of her predecessors had had with their presidents.[301] In July 2010, Secretary Clinton visited Korea, Vietnam, Pakistan and Afghanistan, all the while preparing for the July 31 wedding of daughter Chelsea amid much media attention.[302] In late November 2010, Clinton led the U.S. damage control effort after WikiLeaks released confidential State Department cables containing blunt statements and assessments by U.S. and foreign diplomats.[303][304] A few of the cables released by WikiLeaks concerned Clinton directly: they revealed that directions to members of the foreign service, written by the CIA, had gone out in 2009 under her (systematically attached) name to gather biometric and other personal details on foreign diplomats, including officials of the United Nations and U.S. allies.[305][306][307]

The 2011 Egyptian protests posed the biggest foreign policy crisis for the administration yet.[308] Clinton was in the forefront of U.S. public response to it, quickly evolving from an early assessment that the government of Hosni Mubarak was "stable" to a stance that there needed to be an "orderly transition [to] a democratic participatory government" to a condemnation of violence against the protesters.[309][310] Obama also came to rely upon Clinton's advice, organization, and personal connections in the behind-the-scenes response to developments.[308] As protests spread throughout the region, Clinton was at the forefront of a U.S. response that she recognized was sometimes contradictory, backing some regimes while supporting protesters against others.[311] As the 2011 Libyan civil war took place, Clinton's shift in favor of military intervention was a key turning point in overcoming internal administration opposition and gaining the backing for, and Arab and U.N. approval of, the 2011 military intervention in Libya.[311][312][313] She later used U.S. allies and what she called "convening power" to help keep the Libyan rebels unified as they eventually overthrew the Gaddafi regime.[313] Following the successful May 2011 U.S. mission to kill Osama bin Laden, Clinton played a key role in the administration's decision not to release photographs of the dead al-Qaeda leader.[314] In a December 2011 speech before the United Nations Human Rights Council, she said that the U.S. would advocate for gay rights abroad and that "Gay rights are human rights" and that "It should never be a crime to be gay."[315] The same month saw her conclude the first visit to Burma by a U.S. secretary of state since 1955, as she met with Burmese leaders as well as opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi and sought to support the 2011 Burmese democratic reforms.[316]