John McCain: Difference between revisions

→Family background and early education: insert "tough guy" |

→Cultural and political image: wikifying |

||

| Line 309: | Line 309: | ||

*During a taping of ''[[The Daily Show]]'' on [[April 24]], [[2007]], host [[Jon Stewart]] asked McCain, "What do you want to start with, the bomb Iran song or the walk through the market in Baghdad?" McCain responded by saying, "I think maybe shopping in Baghdad ... I had something picked out for you, too — a little [[Improvised explosive device|IED]] to put on your desk." On [[April 25]], [[2007]], representative [[John Murtha]] demanded an apology from McCain on the floor of the House, where Murtha said that to make jokes about bringing IEDs back for comedians was unconscionable when so many soldiers are dying from IEDs in Iraq.<ref>{{cite news |url = http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,268698,00.html |title = McCain Brushes Off Latest Criticism of His Sense of Humor |date = [[2007-04-26]]}}</ref> McCain responded by telling Murtha and other critics to "Lighten up and get a life."<ref>{{cite news |url = http://abcnews.go.com/GMA/story?id=3082244 |title = John McCain to Murtha: 'Lighten Up,' 'Get a Life' |date = [[2007-04-26]]}}</ref> |

*During a taping of ''[[The Daily Show]]'' on [[April 24]], [[2007]], host [[Jon Stewart]] asked McCain, "What do you want to start with, the bomb Iran song or the walk through the market in Baghdad?" McCain responded by saying, "I think maybe shopping in Baghdad ... I had something picked out for you, too — a little [[Improvised explosive device|IED]] to put on your desk." On [[April 25]], [[2007]], representative [[John Murtha]] demanded an apology from McCain on the floor of the House, where Murtha said that to make jokes about bringing IEDs back for comedians was unconscionable when so many soldiers are dying from IEDs in Iraq.<ref>{{cite news |url = http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,268698,00.html |title = McCain Brushes Off Latest Criticism of His Sense of Humor |date = [[2007-04-26]]}}</ref> McCain responded by telling Murtha and other critics to "Lighten up and get a life."<ref>{{cite news |url = http://abcnews.go.com/GMA/story?id=3082244 |title = John McCain to Murtha: 'Lighten Up,' 'Get a Life' |date = [[2007-04-26]]}}</ref> |

||

*On [[May 18]], [[2007]], during a meeting to negotiate immigration legislation, McCain swore at fellow Senator [[John Cornyn]] (R-Texas) after Cornyn expressed concerns about the number of appeals that illegal immigrants could receive. According to multiple sources, Cornyn told McCain, "Wait a second here. I've been sitting in here for all of these negotiations and you just parachute in here on the last day. You're out of line," to which McCain replied, "Fuck you! I know more about this than anyone else in the room."<ref name="mccainvscornyn">[http://blog.washingtonpost.com/capitol-briefing/2007/05/mccain_cornyn_cursing_showdown.html McCain, Cornyn Engage in Heated Exchange] ''Washington Post Blog'' Capital Exchange. [[May 18]], [[2007]] Retrieved [[June 21]], [[2007]]</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.salon.com/opinion/feature/2007/05/23/immigration/ |title=Is Rush Limbaugh right? |work=Slate |date=[[May 23]], [[2007]] |accessdate=2007-05-23}}</ref> |

*On [[May 18]], [[2007]], during a meeting to negotiate immigration legislation, McCain swore at fellow Senator [[John Cornyn]] (R-Texas) after Cornyn expressed concerns about the number of appeals that illegal immigrants could receive. According to multiple sources, Cornyn told McCain, "Wait a second here. I've been sitting in here for all of these negotiations and you just parachute in here on the last day. You're out of line," to which McCain replied, "[[Fuck you]]! I know more about this than anyone else in the room."<ref name="mccainvscornyn">[http://blog.washingtonpost.com/capitol-briefing/2007/05/mccain_cornyn_cursing_showdown.html McCain, Cornyn Engage in Heated Exchange] ''Washington Post Blog'' Capital Exchange. [[May 18]], [[2007]] Retrieved [[June 21]], [[2007]]</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.salon.com/opinion/feature/2007/05/23/immigration/ |title=Is Rush Limbaugh right? |work=Slate |date=[[May 23]], [[2007]] |accessdate=2007-05-23}}</ref> |

||

[[Image:McCains.JPG|thumb|John and Cindy McCain]] |

[[Image:McCains.JPG|thumb|John and Cindy McCain]] |

||

Revision as of 07:54, 11 February 2008

John McCain | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator from Arizona | |

| Assumed office January 3 1987 Serving with Jon Kyl | |

| Preceded by | Barry Goldwater |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Arizona's 1st district | |

| In office January 3 1983 – January 3 1987 | |

| Preceded by | John Jacob Rhodes Jr. |

| Succeeded by | John Jacob Rhodes III |

| Personal details | |

| Born | August 29, 1936 File:Panama canal zone flag.gif Panama Canal Zone |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | Cindy Hensley McCain |

| Alma mater | United States Naval Academy |

| Profession | Naval aviator |

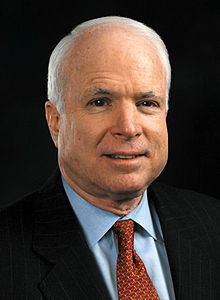

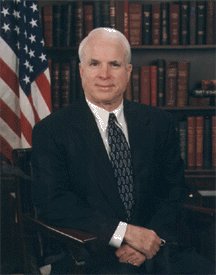

John Sidney McCain III (born August 29 1936) is the senior United States Senator from Arizona, and a candidate for the Republican Party nomination in the 2008 presidential election.

Both McCain's grandfather and father were Admirals in the United States Navy. McCain attended the United States Naval Academy and graduated near the bottom of his class in 1958, though he was intelligent and had done well in subjects that interested him. He became a naval aviator, flying attack aircraft from carriers. During the Vietnam War in 1967, he narrowly escaped death in the Forrestal fire. On his twenty-third bombing mission over North Vietnam later in 1967, he was shot down and badly injured. He then endured five and a half years as a prisoner of war, including periods of torture, before he was released following the Paris Peace Accords in 1973.

Retiring from the Navy in 1981 and moving to Arizona, McCain entered politics. In 1982 he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives from Arizona's 1st congressional district. After serving two terms there, he was elected to the U.S. Senate from Arizona in 1986. He was re-elected Senator in 1992, 1998, and 2004. While generally adhering to American conservatism, McCain established a reputation as a political maverick for his willingness to defy Republican orthodoxy on several issues. Surviving the Keating Five scandal of the 1980s, he made campaign finance reform one of his signature concerns, which eventually led to the passing of the McCain-Feingold Act in 2002.

McCain was a candidate for the Republican nomination in the 2000 presidential election, but was defeated by George W. Bush after closely contested battles in several early primary states. In the 2008 presidential election cycle, McCain was the Republican front-runner as the cycle began, but suffered a near-collapse of his campaign in mid-2007 due to financial issues, and due to his support for comprehensive immigration reform. In late 2007 he staged a comeback, won several key primaries during January 2008, and by the end of that month was the Republican front-runner once again — a status solidified by his Super Tuesday gains in early February and the subsequent withdrawal of his closest competitor, Mitt Romney.

Early life and military career

Family background and early education

McCain was born on August 29, 1936, at the Coco Solo Air Base in the then-American-controlled Panama Canal Zone[1] to Admiral John S. "Jack" McCain, Jr. (1911–1981) and Roberta (Wright) McCain (b. 1912). His father and grandfather were United States Navy admirals,[2] and were the first father-son pair to both achieve four-star admiral rank.[3] His grandfather, Admiral John S. "Slew" McCain, Sr., was a pioneer of aircraft carrier strategy[4] who commanded all carrier forces in the Pacific Ocean theater of World War II, and led American forces into epic actions such as the Battle of Leyte Gulf, dying four days after the conclusion of that war.[3] His father was a submarine commander[3] decorated with both the Silver Star and Bronze Star.[4] McCain has Scots-Irish ancestry.[5]

For the first ten years of his life, "Johnny" McCain (as he was often known)[4] was frequently uprooted as his family (including older sister Sandy and younger brother Joe)[4] followed his father to New London, Connecticut, Pearl Harbor, Hawaii and various other stations in the Pacific Ocean; McCain attended whatever naval base school was available, often to the detriment to his education.[6] After the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, his father was absent for long stretches.[4] As a child, John was known for a quick temper and an aggressive drive to compete and prevail.[6] After World War II was over, his father stayed in the Navy, sometimes working political liaison posts;[4] the family settled in Northern Virginia, and McCain attended the educationally stronger St. Stephen's School in Alexandria, Virginia from 1946 to 1949,[7] where he began to develop an unruly, defiant streak.[8] Another two years were then spent following his father to naval stations;[9] altogether he attended about twenty different schools during his youth.[10] In 1951, McCain enrolled at Episcopal High School in Alexandria, a top private school with a rigorous honor code.[11] McCain earned two varsity letters in wrestling,[12] and he excelled in the lighter weight classes.[3] Gaining the nicknames "Punk" and "McNasty" due to his combative and fiery disposition, he enjoyed and cultivated that tough guy image; he also made some good friends, and graduated from high school in 1954.[8][13][12]

Naval training, early assignments, first marriage and children

Following in the footsteps of his father and grandfather, McCain entered the United States Naval Academy. McCain was a rebellious midshipman, and his career at the Naval Academy was ambivalent and lackluster.[14] He had his share of run-ins with the faculty and leadership; each year he was given over 100 demerits (for unshined shoes, formation faults, talking out of place, and the like),[14] earning him membership in the "Century Club".[3] He did not take well to those of higher rank arbitrarily wielding power over him — "It was bullshit, and I resented the hell out of it"[14] — and would sometimes intervene when he saw it being done to others.[3] At 5 foot 7 inches[15] and 127 pounds[16] (1.70 m and 58 kg), he competed as a lightweight boxer for three years, where he lacked skills but was fearless and "didn't have a reverse gear," as he later put it.[16] Possessed of a strong intelligence,[17] he did well in a few subjects that interested him, such as English literature, history and government.[3][14] Despite his low standing, he was a leader among his fellow midshipmen,[14] especially in organizing off-Yard activities; one classmate said that "being on liberty with John McCain was like being in a train wreck."[14] Despite his difficulties, he later wrote that he never wavered in his desire to show his father and family that he was of the same mettle as his naval forbears. Dropping out was unthinkable, and so he successfully completed his training and graduated from the Naval Academy in 1958; he was sixth from the bottom in class rank,[18] 894th out of 899.[14]

McCain was then commissioned an ensign, and spent two and a half years as a naval aviator in training at Naval Air Station Pensacola in Florida and Naval Air Station Corpus Christi in Texas,[19] flying A-1 Skyraiders.[20] He earned a reputation as a party man, as he drove a Corvette, dated an exotic dancer named "Marie the Flame of Florida", and, as he would later say, "generally misused my good health and youth."[10] He began as a subpar flier, with limited patience for studying aviation manuals.[21] During a practice run in Texas, his engine quit while landing, and his aircraft crashed into Corpus Christi Bay, though he escaped without major injuries.[21][19] He graduated from flight school in 1960,[22] and became a naval pilot of attack aircraft.

McCain was then stationed on the aircraft carriers USS Intrepid and USS Enterprise,[23] in the Caribbean Sea and in deployments to the Mediterranean Sea.[21] He was on alert duty on Enterprise when it imposed a blockade and quarantine of Cuba during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis.[24][22] His aviation skills improved, but he had another close call when he and his plane emerged intact from a collision with power lines, after flying too low over Spain.[21] He was rotated back to shore duty, serving as a flight instructor at Naval Air Station Meridian in Mississippi, where McCain Field was named for his grandfather.[23]

By 1964 he was in a relationship with Carol Shepp, a model originally from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; they had known each other at Annapolis and she had married and then divorced one of his classmates.[19][23] On July 3, 1965, McCain married Shepp in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[18] McCain adopted her two children Doug and Andy,[25] who were five and three years old at the time;[23] he and Carol then had a daughter named Sidney in September 1966.[26][27][28]

In fall 1965, he had his third close call when a flameout over Norfolk, Virginia led to his ejecting safely, and his plane crashed.[21] McCain grew frustrated with his training role, and requested a combat assignment.[20] In December 1966, McCain was assigned to the aircraft carrier USS Forrestal, flying A-4 Skyhawks with the VA-46 "Clansmen";[29] his service there began with tours in the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean.[30] By this time, McCain's father had risen in the ranks, making rear admiral in 1958 and vice admiral in 1963.[31] In May of 1967, his father was promoted to four-star admiral, and became Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Naval Forces, Europe, stationed in London.[4]

Vietnam operations

John Sidney McCain III | |

|---|---|

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service/ | United States Navy (Naval aviation) |

| Years of service | 1958–1981 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Unit | USS Forrestal (CV-59) USS Oriskany (CV-34) |

| Battles/wars | Vietnam |

| Awards | Silver Star Legion of Merit Distinguished Flying Cross Bronze Star Purple Heart |

| Other work | Naval liaison to the United States Senate, United States Senator from Arizona, Presidential candidate |

In Spring 1967, Forrestal was assigned to join Operation Rolling Thunder, the bombing campaign against North Vietnam during the Vietnam War.[18][32] The alpha strikes flown from Forrestal were against specific, pre-selected infrastructure targets such as arms depots, factories, and bridges;[33] they were quite dangerous due to the Soviet-designed and supplied anti-aircraft system fielded by the North Vietnamese Air Defense Force.[33] McCain's first five attack missions over North Vietnam went without incident,[20] and while still unconcerned with minor Navy regulations, McCain had by now garnered the reputation of a serious aviator.[24] McCain and his fellow pilots were already frustrated by Rolling Thunder's infamous micromanagement from Washington;[33] he would later write that "The target list was so restricted that we had to go back and hit the same targets over and over again.... Most of our pilots flying the missions believed that our targets were virtually worthless. In all candor, we thought our civilian commanders were complete idiots who didn’t have the least notion of what it took to win the war."[32]

By then a Lieutenant Commander, McCain was again almost killed in action on July 29, 1967 while serving on Forrestal, operating at Yankee Station in the Gulf of Tonkin. The crew was preparing to launch attacks, when a Zuni rocket from an F-4 Phantom was accidentally fired across the carrier's deck. The rocket struck McCain's A-4E Skyhawk as the jet was preparing for launch.[34][35] The impact ruptured the Skyhawk's fuel tank, which ignited the fuel and knocked two bombs loose. McCain escaped from his jet by climbing out of the cockpit, working himself to the nose of the jet, and jumping off its refueling probe onto the burning deck of the aircraft carrier. Ninety seconds after the impact, one of the bombs exploded underneath his airplane. McCain was struck in the legs and chest by shrapnel. The ensuing fire killed 132 sailors, injured 62 others, destroyed at least 20 aircraft, and took 24 hours to control.[36] A day or two after the Forrestal incident, McCain told New York Times reporter R. W. Apple, Jr. in Saigon that, "It's a difficult thing to say. But now that I've seen what the bombs and the napalm did to the people on our ship, I'm not so sure that I want to drop any more of that stuff on North Vietnam."[37] But such a change of course was unlikely; as McCain said, "I always wanted to be in the Navy. I was born into it and I never really considered another profession. But I always had trouble with the regimentation."[37]

As Forrestal headed for repairs, McCain volunteered to join the VA-163 "Saints" on board the short-staffed USS Oriskany. This ship had earlier endured its own deck fire disaster[20] and its squadrons had suffered heavy losses during Rolling Thunder, with one-third of its pilots killed or captured during 1967.[20] McCain joined Oriskany in September 1967, for a tour he expected would finish early the next summer.[38] By late October 1967, McCain had flown a total of 22 bombing missions.[39]

Prisoner of war

On October 26, 1967, McCain was flying as part of a 20-plane attack against a thermal power plant in central Hanoi, a heavily defended target area that had previously been off-limits to U.S. raids.[41][42] McCain's A-4 Skyhawk was shot down by a Soviet-made SA-2 anti-aircraft missile[42] while pulling up after dropping its bombs.[43] McCain fractured both arms and a leg in being hit and ejecting from his plane.[44] He nearly drowned after he parachuted into Truc Bach Lake in Hanoi.[41] After he regained consciousness, a mob gathered around, spat on him, kicked him, and stripped him of his clothes.[45] Others crushed his shoulder with the butt of a rifle and bayoneted him in his left foot and abdominal area; he was then transported to Hanoi's main Hoa Loa Prison, nicknamed the "Hanoi Hilton" by American POWs.[45][46] Although McCain was badly wounded, his captors refused to give him medical care unless he gave them military information; they beat and interrogated him, but McCain only offered his name, rank, serial number, and date of birth.[45] Soon thinking he was near death, McCain said he would give them information if taken to the hospital, hoping he could then put them off once he was treated.[47] A prison doctor came and said it was too late, as McCain was about to die anyway.[45] Only when the North Vietnamese discovered that his father was a top admiral did they give him medical care[45] and announce his capture. At this point, two days after McCain's plane went down, that event and his status as a POW made the front pages of The New York Times[37] and The Washington Post.[48]

McCain spent six weeks in the Hoa Loa hospital, receiving marginal care.[41] He was interviewed by a French television reporter whose report was carried on CBS, and was observed by a variety of North Vietnamese, including the famous General Vo Nguyen Giap.[45] Many of the North Vietnamese observers assumed that he must be part of America's political-military-economic elite.[45] Now having lost 50 pounds, in a chest cast, and with his hair turned white,[41] McCain was sent to a prisoner-of-war camp on the outskirts of Hanoi nicknamed "the Plantation"[49] in December 1967, into a cell with two other Americans who did not expect him to live a week (one was Bud Day, a future Medal of Honor recipient); they nursed McCain and kept him alive.[50] In March 1968, McCain was put into solitary confinement, where he would remain for two years.[45] In July 1968, McCain's father was named Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Command (CINCPAC), stationed in Honolulu and commander of all U.S. forces in the Vietnam theater.[4] McCain was immediately offered a chance to return home early:[41] the North Vietnamese wanted a worldwide propaganda coup by appearing merciful, and also wanted to show other POWs that elites like McCain were willing to be treated preferentially.[45] McCain turned down the offer of repatriation, due to the Code of Conduct principle of "first in, first out": he would only accept the offer if every man taken in before him was released as well.[51] McCain's refusal to be released was even remarked upon by North Vietnamese senior negotiator Le Duc Tho to U.S. envoy Averell Harriman during the ongoing Paris Peace Talks.[52]

In August of 1968, a program of vigorous torture methods began on McCain, using rope bindings into painful positions, and beatings every two hours, at the same time as he was suffering from dysentery.[45][41] Teeth and bones were broken again, as was McCain's spirit; the beginning of a suicide attempt was stopped by guards.[41] After four days of this, McCain signed an anti-American propaganda "confession" that said he was a "black criminal" and an "air pirate",[41] although he used stilted Communist jargon and ungrammatical language to signal that the statement was forced.[53] He felt then and always that he had dishonored his country, his family, his comrades and himself by his statement,[54] but as he would later write, "I had learned what we all learned over there: Every man has his breaking point. I had reached mine."[45] His injuries to this day have left him incapable of raising his arms above his head.[13] Two weeks later his captors tried to force him to sign a second statement, and this time, his will to resist restored, he refused.[45] He received two to three beatings per week because of his continued refusal.[55] Other American POWs were similarly tortured and maltreated in order to extract "confessions".[45] On one occasion when McCain was physically coerced to give the names of members of his squadron, he supplied them the names of the Green Bay Packers' offensive line.[53] On another occasion, a guard surreptitiously loosened McCain's painful rope bindings for a night; when the guard later saw McCain on Christmas Day, he stood next to McCain and silently drew a cross in the dirt with his foot[56] (decades later, McCain would relate this Good Samaritan story during his presidential campaigns, as a testament to faith and humanity[57][58]). McCain refused to meet with various anti-war peace groups coming to Hanoi, such as those led by David Dellinger, Tom Hayden, and Rennie Davis, not wanting to give either them or the North Vietnamese a propaganda victory based on his connection to his father.[45]

In May 1969, U.S. Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird began publicly questioning North Vietnamese treatment of U.S. prisoners.[59] On June 5, 1969, a Radio Hanoi broadcast denied any mistreatment, and quoted from a statement it attributed to McCain: "I have bombed the cities, towns and villages and caused injuries and even death for the people of North Vietnam. After I was captured, I was taken to a hospital in Hanoi where I received very good medical treatment."[59] In October 1969, treatment of McCain and the other POWs suddenly improved, after a badly beaten and weakened POW who had been released that summer disclosed to the world press the conditions to which they were being subjected.[45] In December 1969, McCain was transferred back to the Hoa Loa "Hanoi Hilton";[45] his solitary confinement ended in March 1970.[45] McCain continued to refuse to see anti-war groups or journalists sympathetic to the North Vietnamese regime;[45] to one visitor who did speak with him, McCain later wrote, "I told him I had no remorse about what I did, and that I would do it over again if the same opportunity presented itself."[45] McCain and other prisoners were moved around to different camps at times, but conditions over the next several years were generally more tolerable than they had been before.[45] Back at the "Hanoi Hilton" from November 1971 onward,[45] McCain and the other POWs cheered the intense, Hanoi-focused, B-52-led U.S. "Christmas Bombing" campaign of December 1972 — whose explosions lit the night sky and shook the walls of the camp, and whose daily orders were issued by McCain's father, knowing his son was in the vicinity — as a forceful measure to force North Vietnam to terms.[45][60]

Altogether, McCain was held as a prisoner of war in North Vietnam for five and a half years. The Paris Peace Accords were signed on January 27, 1973, ending direct U.S. involvement in the war, but the Operation Homecoming arrangements for POWs took longer; McCain was finally released from captivity on March 15, 1973,[61] having been a POW for almost an extra five years due to his refusal to accept the out-of-sequence repatriation offer.[62]

Return to United States

Upon his return to the United States, McCain was reunited with his wife Carol, who had suffered her own crippling, near-death ordeal during his captivity, due to an automobile accident in December 1969 that left her facing months of operations and physical therapy;[63] by the time he saw her again she was four inches shorter, on crutches, and substantially heavier.[64] As a returned POW, McCain became a celebrity of sorts: The New York Times ran a front-page photo of him getting off the plane at Clark Air Base in the Philippines;[65] he published a long cover story describing his ordeal and his support for the Nixon administration's handling of the war in U.S. News & World Report;[45] he participated in several parades and personal appearances; and a photograph of him on crutches shaking the hand of President Richard Nixon at a White House reception for returning POWs became iconic.[63] The McCains became frequent guests of honor at dinners hosted by Governor of California Ronald Reagan and his wife Nancy Reagan;[66] Ronald Reagan had been admired by McCain and other POWs even while in captivity, and would serve as a later role model for McCain.[67]

McCain underwent treatment for his injuries, and attended the National War College in Fort McNair in Washington, D.C. during 1973–1974.[63][22] There he studied intensively the history of Vietnam and of the war; he came to terms with what had happened, as well as with the anti-war movement in the U.S. and those who had evaded the draft.[68] He returned to Saigon in November 1974, to speak at the South Vietnamese war college, five months before the city fell.[69] He resolved not to become a "professional POW" but to move forward and rebuild his life.[68] Few thought McCain could fly again, but he was determined to try, and he engaged in nine months of grueling, painful physical therapy, especially to get his knees to bend again.[64] By late 1974 McCain had recuperated just enough to pass his flight physical[64] and have his flight status reinstated,[63] and he became Executive Officer and then Commanding Officer of the VA-174 "Hellrazors", which was an A-7 Corsair II Navy training squadron stationed at Naval Air Station Cecil Field outside Jacksonville, Florida and the largest attack squadron in the Navy.[63][22][70] McCain's leadership abilities were credited with turning around a mediocre unit, improving its aircraft readiness and pilot safety metrics and winning the squadron its first Meritorious Unit Commendation.[64] While some senior officers resented McCain's presence as favoritism due to his father, junior officers rallied to him and helped him qualify for A-7 carrier landings.[64]

During their time in Jacksonville, the McCains' marriage began to falter.[71] McCain had extramarital affairs,[71] and he would later say, "My marriage's collapse was attributable to my own selfishness and immaturity more than it was to Vietnam, and I cannot escape blame by pointing a finger at the war. The blame was entirely mine."[71] His wife Carol would later echo those sentiments, saying "I attribute [the breakup of our marriage] more to John turning 40 and wanting to be 25 again than I do to anything else."[71]

Senate liaison and second marriage

In 1976, McCain briefly thought of running for the U.S. House of Representatives from Florida.[72] Instead, based upon the recommendation of Admiral James L. Holloway III,[63] in 1977 McCain was appointed the Navy's liaison to the U.S. Senate.[72] Returning to the Washington, D.C. area, McCain soon became the leader of the Russell Senate Office Building liaison operation, and would later say it represented "[my] real entry into the world of politics and the beginning of my second career as a public servant."[63] McCain was influenced by senators of both parties, and especially by a strong bond with Republican Senator John Tower of Texas, ranking member of the Senate Armed Services Committee.[63] McCain was still living with his wife, although they had been briefly separated soon after returning to Washington.[64]

In 1979, while attending a military reception in Hawaii, McCain met and fell in love with Cindy Lou Hensley, 17 years his junior, a teacher from Phoenix, Arizona who was the daughter of James Willis Hensley, a wealthy Anheuser-Busch distributor, and Marguerite Smith Hensley.[71] By then McCain's naval career had stalled, as he had poor annual physicals and he had been given no major sea command.[73] It was unlikely he would ever be promoted to admiral as his grandfather and father had been; he had no base from which to go into politics, and he was at a turning point.[64]

McCain filed for and obtained an uncontested divorce from his wife Carol in Florida on April 2, 1980;[25] he gave her a generous settlement, including houses in Virginia and Florida and financial support for her ongoing medical treatments, and they would remain on good terms.[71] McCain and Hensley were married on May 17, 1980[18] in Phoenix, Arizona, with Senators William Cohen and Gary Hart as best man and groomsman.[71] McCain's children were upset with him and did not attend the wedding,[64] but after several years they reconciled with him and Cindy.[64][27] Carol became a personal assistant to Nancy Reagan and later head of the White House Visitors Center.[74]

McCain retired from the Navy in 1981 as a Captain.[15] During his military career, he received a Silver Star, a Bronze Star, the Legion of Merit, the Purple Heart, and a Distinguished Flying Cross.[75]

Political career

U.S. Congressman and more children

Living in Phoenix, McCain went to work for his new father-in-law Jim Hensley's large Anheuser-Busch beer distributorship as Vice President of Public Relations,[71] where he gained political support among the local business community,[72] meeting powerful figures such as banker Charles Keating, Jr., real estate developer Fife Symington III,[71] and newspaper publisher Darrow "Duke" Tully,[72] all the while looking for an electoral opportunity.[71] When John Jacob Rhodes, Jr., the longtime Republican congressman from Arizona's 1st congressional district, announced his retirement, McCain ran for the seat as a Republican in 1982.[76] McCain faced two experienced state legislators in the Republican nomination process, and as a newcomer to the state was hit with repeated charges of being a carpetbagger.[71] Finally at a candidates forum he gave a famous refutation to a voter making the charge:

Listen, pal. I spent 22 years in the Navy. My father was in the Navy. My grandfather was in the Navy. We in the military service tend to move a lot. We have to live in all parts of the country, all parts of the world. I wish I could have had the luxury, like you, of growing up and living and spending my entire life in a nice place like the First District of Arizona, but I was doing other things. As a matter of fact, when I think about it now, the place I lived longest in my life was Hanoi. [71][77]

A Phoenix Gazette columnist would later label this "the most devastating response to a potentially troublesome political issue I've ever heard."[71] With the assistance of some local political endorsements and his Washington connections, as well as effective television advertising, partly financed by $167,000 that his wife lent to his campaign (which helped him outspend his opponents),[72] and with support of Tully's The Arizona Republic (the state's most powerful newspaper),[72] McCain won the highly contested primary election in September 1982.[71] By comparison, the general election two months later became an easy lopsided victory for him in the heavily Republican district.[71]

McCain made an immediate impression in Congress. He was elected the president of the 1983 Republican freshman class of representatives.[71] He was assigned to the Committee on Interior Affairs, the Select Committee on Aging, and eventually to the chairmanship of the Republican Task Force on Indian Affairs.[78] He sponsored a number of Indian Affairs bills, dealing mainly with giving distribution of lands to reservations and tribal tax status; most of these bills were unsuccessful.[79] McCain’s politics at this point were mainly in line with President Ronald Reagan, from issues ranging from the economy to the Soviet Union;[80] however, his vote against a resolution allowing President Reagan to keep U.S. Marines deployed as part of the Multinational Force in Lebanon, on the grounds that he "[did] not foresee obtainable objectives in Lebanon," would seem prescient after the catastrophic Beirut barracks bombing a month later;[71] this vote would also start his national media reputation as a political maverick.[71] McCain won re-election to the House easily in 1984.[71] In the new term McCain got the Indian Economic Development Act of 1985 signed into law.[81] In 1985 he returned to Vietnam with Walter Cronkite for a CBS News special, and saw the monument put up next to where the famous downed "air pirate Ma Can" had been pulled from the Hanoi lake;[82] it was the first of several return trips McCain would make there.[82] In 1986 he broke ranks again in voting to successfully override Reagan's veto of the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act that imposed sanctions against South Africa.[83]

In 1984 McCain and his wife Cindy had their first child together, daughter Meghan. She was followed in 1986 by son John Sidney IV (known as "Jack"), and in 1988 by son James.[84] In 1991, Cindy McCain brought an abandoned three-month old girl, who badly needed medical treatment for a severe cleft palate, to the U.S. from a Bangladeshi orphanage run by Mother Teresa;[85] the McCains decided to adopt her, and named her Bridget.[86] A drawn-out adoption process began, slowed down by uncertainty over the exact fate of the girl's father,[87] but in 1993 the adoption was ruled final.[88] McCain then stood by his wife when she disclosed in 1994 a previous addiction to painkillers and said that she hoped the publicity would give other drug addicts courage in their struggles.[89] Beginning in the early 1990s, McCain began attending the 6,000-member North Phoenix Baptist Church in Arizona, part of the Southern Baptist Convention, later saying "[I found] the message and fundamental nature more fulfilling than I did in the Episcopal church. ... They're great believers in redemption, and so am I."[90] Nevertheless he still identified himself as Episcopalian,[90] and while Cindy and two of their children were baptized into the Baptist church, he was not.[90]

U.S. Senator

McCain decided to run for United States Senator from Arizona in 1986, when longtime American conservative icon and Arizona fixture Barry Goldwater retired.[91] No Republican would oppose McCain in the primary, and as described by his press secretary Torie Clarke, McCain's political strength convinced his most formidable possible Democratic opponent, Governor Bruce Babbitt, not to run for the senate seat.[91] Instead McCain faced a weaker opponent, former state legislator Richard Kimball, a young politician with an offbeat personality who slept on his office floor[92] and whom McCain's allies in the Arizona press characterized as having "terminal weirdness."[91] McCain's associations with Duke Tully, who by now had been disgraced for having concocted a fictitious military record, as well as revelations of father-in-law Jim Hensley's past brushes with the law, became campaign issues, but in the end McCain won the election easily with 60 percent of the vote to Kimball's 40 percent.[91][72]

Upon entering the Senate in 1987, McCain became a member of the Senate Armed Services Committee, with whom he had formerly done his Navy liaison work; he also joined the Commerce Committee and the Indian Affairs Committee.[91] He has often supported the Native American agenda, advocating self-governance and sovereignty, supporting Native American gambling enterprises and tribe control of adoptions. "Never deceived them," McCain once said, "They have been deceived too many times in the last 200 years."[93]

McCain was a strong supporter of the Gramm-Rudman legislation that enforced automatic spending cuts in the case of budget deficits.[94] McCain soon gained national visibility, delivering an emotional, impassioned speech about his time as a POW at the 1988 Republican National Convention[95] being mentioned by the press as a short list vice-presidential running mate for Republican nominee George H. W. Bush,[95][91] and being named chairman of Veterans for Bush.[96] In 1989, he became a staunch defender of his friend John Tower's doomed nomination for U.S. Secretary of Defense; McCain butted heads with Moral Majority co-founder Paul Weyrich — who was challenging Tower regarding alleged heavy drinking and extramarital affairs[91] — and thus began McCain's difficult relationship with the Christian right, as he would later write that Weyrich was "a pompous self-serving son of a bitch."[91]

Keating Five

McCain's upwards political trajectory was jolted when he became enmeshed in the Keating Five scandal of the 1980s. In the context of the Savings and Loan crisis of that decade, Charles Keating Jr.'s Lincoln Savings and Loan Association, a subsidiary of his American Continental Corporation, was insolvent due to some bad loans. In order to regain solvency, Lincoln sold investment in a real estate venture as a FDIC insured savings account. This caught the eye of federal regulators who were looking to shut it down. It is alleged that Keating contacted five senators to whom he made contributions. McCain was one of those senators and he met at least twice in 1987 with Ed Gray, chairman of the Federal Home Loan Bank Board, seeking to prevent the government's seizure of Lincoln. Between 1982 and 1987, McCain received approximately $112,000 in political contributions from Keating and his associates.[97] In addition, McCain's wife and her father had invested $359,100 in a Keating shopping center in April 1986, a year before McCain met with the regulators. McCain, his family and baby-sitter made at least nine trips at Keating's expense, sometimes aboard the American Continental jet. After learning Keating was in trouble over Lincoln, McCain paid for the air trips totaling $13,433.[98]

Eventually the real estate venture failed, leaving many broke. Federal regulators ultimately filed a $1.1 billion civil racketeering and fraud suit against Keating, accusing him of siphoning Lincoln's deposits to his family and into political campaigns. The five senators came under investigation for attempting to influence the regulators. In the end, none of the senators were convicted of any crime, although McCain was rebuked by the Senate Ethics Committee for exercising "poor judgment" for intervening with the federal regulators on behalf of Keating.[99] On his Keating Five experience, McCain said: "The appearance of it was wrong. It's a wrong appearance when a group of senators appear in a meeting with a group of regulators, because it conveys the impression of undue and improper influence. And it was the wrong thing to do."[99]

McCain survived the political scandal by, in part, becoming friendly with the political press;[100] with his blunt manner, he became a frequent guest on television news shows, especially once the 1991 Gulf War began and his military and POW experience became in demand.[100] McCain began campaigning against lobbyist money in politics from then on. His 1992 re-election campaign found his opposition split between Democratic community and civil rights activist Claire Sargent and impeached and removed former Governor Evan Mecham running as an independent.[100] Although Mecham garnered some hard-core conservative support, Sargent's campaign never gathered momentum and the Keating Five affair did not dominate discussion.[100][101] McCain again won handily,[100] getting 56 percent of the vote to Sargent's 32 percent and Mecham's 11 percent.

A "maverick" senator

In January 1993 McCain was named chairman of the board of directors of the International Republican Institute,[102] a non-profit democracy promotion organization with informal ties to the Republican party. The position would allow McCain to bolster his foreign policy expertise and credentials.[102]

McCain also branched out and worked with Democratic senators. He was a member of the 1991–1993 Senate Select Committee on POW/MIA Affairs, chaired by Democrat and fellow Vietnam War veteran John Kerry, convened to investigate the fate of U.S. service personnel listed as missing in action during the Vietnam War. The committee's work included more visits to Vietnam and getting the Department of Defense to declassify over a million pages of relevant documents.[103] The committee's final report, which McCain endorsed, stated that, "While the Committee has some evidence suggesting the possibility a POW may have survived to the present, and while some information remains yet to be investigated, there is, at this time, no compelling evidence that proves that any American remains alive in captivity in Southeast Asia."[104] After many years of disliking Kerry due to his actions with Vietnam Veterans Against the War,[105] McCain developed "unbounded respect and admiration" for Kerry during the hearings.[105][106] The actions of the committee were designed to allow for improved ties between the two countries;[107] McCain pressed for normalization of diplomatic relations with Vietnam, partly because it was "a time to heal ... it's a way of ending the war; it's time to move on,"[108] and partly because he saw it in the U.S. national interest to do so,[108] in particular envisioning Vietnam as a valuable regional counterbalance against China.[109] In 1994 the Senate passed a resolution, sponsored by Kerry and McCain, that called for an end to the existing trade embargo against Vietnam; it was intended to pave the way for normalization.[110] During his time on the committee and afterward, McCain was vilified as a fraud,[108] traitor,[105] or "Manchurian Candidate"[109] by some POW/MIA activists who believed that there were large numbers of American servicemen still being held against their will in Southeast Asia.[108] McCain said that he and Kerry had gotten the Vietnamese to give them full access to their records, and that he had spent thousands of hours trying to find real, not fabricated, evidence of surviving Americans.[103] In 1995, President Bill Clinton normalized diplomatic relations with the country of Vietnam,[109] with McCain's and Kerry's visible support during the announcement giving the Vietnam War-avoiding Clinton some political cover.[109][105]

Having survived the Keating Five scandal, McCain made attacking the corrupting influence of big money on American politics his signature issue.[83] Starting in late 1994 he worked with Democratic Wisconsin Senator Russ Feingold on campaign finance reform;[83] their McCain-Feingold bill would attempt to put limits on "soft money", funds that corporations, unions, and other organizations could donate to political parties, which would then be funneled to political candidates in circumvention of "hard money" donation limits.[83] From the start, McCain and Feingold's efforts were opposed by large money interests, by incumbents in both parties, by those who felt spending limits impinged on free political speech, and by those who wanted to lessen the power of what they saw as media bias.[83] On the other hand, it garnered considerable sympathetic coverage in the national media, and from 1995 on, "maverick Republican" became a label frequently applied to McCain in stories.[83] He has used the term himself, and in fact one of the chapters in his 2002 book Worth the Fighting For is titled "Maverick".[111] The first version of the McCain-Feingold Act was introduced into the Senate in September 1995; it was filibustered in 1996 and never came to a vote.[112]

McCain also attacked pork barrel spending within Congress, believing that the practice did not contribute to the greater national interest.[83] Towards this end he was instrumental in pushing through approval of the Line Item Veto Act of 1996,[83] which gave the president the power to veto individual items of pork. Although this was one of McCain's biggest Senate victories,[83] the effect was short-lived as the U.S. Supreme Court ruled the act unconstitutional in 1998.[113] In a more symbolic attempt to limit congressional privilege, he introduced an amendment in 1994 to remove free VIP parking for members of Congress at D.C. area airports; his annoyed colleagues rejected the notion and accused McCain of grandstanding.[83] McCain was one of only four Republicans in Congress to vote against the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act in 1995,[114] and was the only Republican senator to vote against the Freedom to Farm Act in 1996.[115] He was one of only five senators to vote against the Telecommunications Act of 1996.[116]

At the start of the 1996 presidential election, McCain served as national campaign chairman for the highly unsuccessful Republican nomination effort of Texas Senator Phil Gramm.[117] After Gramm dropped out, McCain endorsed eventual nominee Senate Majority Leader Bob Dole,[117] and was again on the short list of possible vice-presidential picks.[118][100] McCain formed a close bond with Dole, based in part on their shared near-death war experiences;[118] he nominated Dole at the 1996 Republican National Convention and was a key friend and advisor to Dole throughout his ultimately losing general election campaign.[118]

In 1997, McCain became chairman of the powerful Senate Commerce Committee; he was criticized for accepting funds from corporations and businesses under the committee's purview,[83] but responded by saying that, "Literally every business in America falls under the Commerce Committee" and that he restricted those contributions to $1,000 and thus was not part of the big-money nature of the campaign finance problem.[83] In that year, Time magazine named McCain as one of the "25 Most Influential People in America".[119] McCain used his chairmanship to take on the tobacco industry in 1998, proposing legislation that would increase cigarette taxes in order to fund anti-smoking campaigns and reduce the number of teenage smokers, increase research money on health studies, and help states pay for smoking-related health care costs.[120][83] The industry spent some $40–50 million in national advertising in response;[120][83] while McCain's bill had the support of the Clinton administration and many public health groups, most Republican senators opposed it, stating it would create an unwieldy new bureaucracy.[120] The bill failed to gain cloture twice[120] and was seen as a bad political defeat for McCain.[120] During 1998 a revised version of the McCain-Feingold Act came up for Senate consideration, but while having majority support it again fell victim to a filibuster and failed to gain cloture.[112]

McCain easily won re-election to a third senate term in November 1998, gaining 69 percent of the vote to 27 percent for his Democratic opponent, environmental lawyer Ed Ranger.[83] Ranger was a motorcycle enthusiast[121] and political novice who had only recently returned from Mexico.[122] McCain took no "soft money" during the campaign, but still raised $4.4 million for his bid, explaining that he had needed it in case the tobacco companies or other Washington special interests mounted a strong effort against him.[83] One of Ranger's campaigning points had been that McCain was really more interested in running for president;[83] McCain indeed created a presidential exploratory committee the following month.[121]

During 1999, the McCain-Feingold Act once again came up for consideration, but the same failure to gain cloture befell it again.[112] During that year, McCain shared the Profile in Courage Award with Feingold for their work in trying to enact this campaign finance reform; McCain was cited for opposing his own party on the bill at a time when he was trying to win the party's presidential nomination.[123]

2000 presidential campaign

McCain's co-authored, best-selling family memoir, Faith of My Fathers, published in August 1999, helped propel his presidential run for 2000.[124] McCain had initially planned on announcing his candidacy and beginning active campaigning in April 1999, but the state of the U.S. involvement in the Kosovo War caused him to simply state without fanfare that he would be a candidate.[125] McCain formally announced his candidacy on September 27, 1999 in Nashua, New Hampshire,[126] saying he was staging "a fight to take our government back from the power brokers and special interests and return it to the people and the noble cause of freedom it was created to serve."[124] There was a crowded field of Republican candidates, but the big leader in terms of establishment party support and fundraising was Texas Governor and presidential son George W. Bush.[127] Indeed, top-echelon Republican contenders such as Lamar Alexander, John Kasich, and Dan Quayle were already withdrawing from the race due to Bush's strength.[127] The day after McCain announced, Bush made a show of visiting Phoenix and displaying that he, not McCain, had the endorsement of Arizona Governor Jane Dee Hull and several other prominent local political figures;[124] Hull would continue to attack McCain during the campaign, and was featured in high-profile Arizona Republic and New York Times stories about McCain's reputation for having a bad temper.[124][128]

Following political consultant Mike Murphy's advice,[129] McCain skipped the Iowa caucus, where his lack of base party support would hurt him in organizing, and focused instead on the New Hampshire primary, where his message held appeal to independents and where Bush's father had never been very popular.[129] He traveled on a campaign bus called the Straight Talk Express, whose name capitalized on his reputation as a political maverick who would speak his mind. In visits to towns he gave a ten-minute talk focused on campaign reform issues, then announced he would stay until he answered every question that everyone had. He made over two hundred stops, talking in every town in New Hampshire in an example of "retail politics" that overcame Bush's familiar name. McCain was famously accessible to the press, using free media to compensate for his lack of funds;[124] as one reporter later recounted, "McCain talked all day long with reporters on his Straight Talk Express bus; he talked so much that sometimes he said things that he shouldn't have, and that's why the media loved him."[130] On February 1, 2000, he won the primary with 49 percent of the vote to Bush's 30 percent, and suddenly was the celebrity of the hour. Other Republican candidates had dropped out or failed to gain traction, and McCain became Bush's only serious opponent. Analysts predicted that a McCain victory in the crucial South Carolina primary might give his insurgency campaign unstoppable momentum;[131][132][133] a degree of fear and panic crept into not only the Bush campaign[124] but also the Republican establishment and movement conservatism.[132][133]

The battle between Bush and McCain for South Carolina has entered American political lore as one of the nastiest, dirtiest, and most brutal ever.[124][134][135] On the one hand, Bush switched his label for himself from "compassionate conservative" to "reformer with results",[136] as part of trying to co-opt McCain's popular message of reform.[124][136] On the other hand, a variety of business and interest groups that McCain had challenged in the past now pounded McCain with negative ads.[124] The day that a new poll showed McCain five points ahead in the state,[137] Bush allied himself on stage with a marginal and controversial veterans activist named J. Thomas Burch, who accused McCain of having "abandoned the veterans" on POW/MIA and Agent Orange issues: "He came home from Vietnam and forgot us."[124][137] Incensed,[137] McCain ran ads accusing Bush of lying and comparing Bush to Bill Clinton,[124] which Bush complained was "about as low a blow as you can give in a Republican primary."[124] But that was not the worst. A mysterious semi-underground campaign began against McCain, delivered by push polls, faxes, e-mails, flyers, and the like, and comprising a series of smears: most famously, that he had fathered a black child out of wedlock (a hurtful reference to the McCains' dark-skinned daughter Bridget, adopted from Bangladesh, and thought to be an especially effective slur in a Deep South state where race was still central[135]), but also that his wife Cindy was a drug addict, that he was a homosexual, that he was a "Manchurian Candidate" traitor or mentally unstable from his North Vietnam POW days.[124][134] The Bush campaign strongly denied any involvement with these attacks;[134] Bush said he would fire anyone who ran defamatory push polls.[138] Above ground, Bush mobilized the state's evangelical voters,[124] and conservative über-broadcaster Rush Limbaugh entered the fray supporting Bush and going on at length about how McCain was a favorite of liberal Democrats.[139] Polls swung in Bush's favor; by not having accepted federal matching funds for its campaign, Bush had unlimited money to spend on advertisements, while McCain was near his limit.[139] With three days to go, McCain shut down his negative ads against Bush and tried to stress a positive image.[139] McCain lost South Carolina on February 19, with 42 percent of the vote against Bush's 53 percent,[140] allowing Bush to regain the momentum.[140]

While South Carolina was known for legendary hard-knuckled political consultant Lee Atwater[135] and rough elections,[134] this had been more: Michael Graham, a native writer, radio host, and political operative, would say "I have worked on hundreds of campaigns in South Carolina, and I've never seen anything as ugly as that campaign."[141] In subsequent years there would be persistent accounts trying to tie the anti-McCain smears to high levels of the Bush campaign: the 2003 book Bush's Brain would use it to build up their "evil genius" depiction of Bush chief strategist Karl Rove,[142] while a 2008 PBS NOW program showed a local political consultant stating that Warren Tompkins, a Lee Atwater protegé and then Bush chief strategist for the state, was responsible.[135][143] In contrast, in 2004 National Review's Byron York would try to debunk many of the South Carolina smear reports as unfounded legend.[144] McCain's campaign manager said in 2004 they never found out where the smear attacks came from,[145] while McCain himself never doubted their existence;[124] McCain would say of the rumor spreaders, "I believe that there is a special place in hell for people like those."[86] McCain regretted some aspects of his own campaign there as well, in particular changing his stance on flying the Confederate flag at the state capitol from a "very offensive" "symbol of racism and slavery" to "a symbol of heritage";[124][134] he would later write, "I feared that if I answered honestly, I could not win the South Carolina primary. So I chose to compromise my principles."[134] According to one report, the South Carolina experience overall left McCain in a "very dark place."[134]

McCain's campaign never completely recovered from his defeat in South Carolina, although he did rebound partially by winning in Arizona and Michigan on February 22,[146] mocking Governor Hull's opposition in the former,[124] and capturing many Democratic and independent votes in the latter;[146] however, he made serious mistakes that negated any momentum he may have regained with the Michigan victory. Still reeling from his South Carolina experience, he made a February 28 speech in Virginia Beach that criticized as divisive conservative Christian leaders such as Pat Robertson and Jerry Falwell,[134] declaring "... we embrace the fine members of the religious conservative community. But that does not mean that we will pander to their self-appointed leaders."[147] McCain lost the Virginia primary on February 29, as well as one in Washington.[148] A week later on March 7, 2000, he lost nine of the thirteen primaries on Super Tuesday to Bush, including large states such as California, New York, Ohio, and Georgia; McCain's wins were confined to the New England states of Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut and Vermont.[149] His overall loss on that day has been attributed to his going "off message", ineffectively accusing Bush of being anti-Catholic due to having visited Bob Jones University[150] and getting into a verbal battle with leaders of the Religious Right.[151] With no hope of catching Bush's delegate lead after Super Tuesday, McCain withdrew from the race on March 9, 2000.[152]

2001–2004

With no love lost between them, McCain began 2001 by breaking against the new George W. Bush administration on a number of matters.[154] In January 2001 the latest iteration of McCain-Feingold was introduced into the Senate; it was opposed by Bush and most of the Republican establishment,[154] but helped by the 2000 election results, it passed the Senate in one form until procedural obstacles delayed it again.[155] In these few months McCain also opposed Bush on an HMO reform bill, on climate change measures, and on gun legislation.[154] Then in May 2001, McCain voted against the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001,[156] Bush's $350 billion in tax breaks over 11 years, which became known as "the Bush tax cuts". He was one of only two Republicans to do so,[154] saying that "I cannot in good conscience support a tax cut in which so many of the benefits go to the most fortunate among us, at the expense of middle class Americans who most need tax relief."[157][156] Then when Republican Senator Jim Jeffords became an Independent, throwing control of the Senate to Democrats, McCain defended him against "self-appointed enforcers of party loyalty."[154] Indeed, there was speculation at the time,[158] and in years since,[159] about McCain himself possibly leaving the Republican Party during the first half of 2001. Accounts have differed as to who initiated any discussions, and McCain has always adamantly denied, then and later, that he ever considered doing so.[154][159] In any case, all of this was enough for conservative Arizonan critics of McCain to organize rallies and recalls against him in May and June 2001.[154]

After the September 11, 2001 attacks, McCain became a supporter of Bush and an advocate for strong military measures against those responsible with respect to the U.S.-led war in Afghanistan;[154] in a high-profile[154] late October 2001 Wall Street Journal op-ed piece he wrote, "America is under attack by a depraved, malevolent force that opposes our every interest and hates every value we hold dear." After advocating an overwhelming, not increment, approach against the Taliban in Afghanistan, including the use of ground forces, he concluded, "War is a miserable business. Let's get on with it."[160] He and Democratic Senator Joe Lieberman wrote the legislation that created the 9/11 Commission,[161] while he and Democratic Senator Fritz Hollings co-sponsored the Aviation and Transportation Security Act that federalized airport security under what became the Transportation Security Administration.[162]

McCain-Feingold had been yet further delayed by the effects of September 11.[155] Finally in March 2002, aided by the aftereffects of the Enron scandal, it passed both House and Senate and, known formally as the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act, was signed into law by President Bush.[154] Seven years in the making, it was McCain's greatest legislative achievement[154] and had become, in the words of one biographer, "one of the most famous pieces of federal legislation in modern American political history."[163]

Meanwhile, in discussions over proposed U.S. action against Iraq, McCain was a strong supporter of the Bush position, labeling Saddam Hussein "a megalomaniacal tyrant whose cruelty and offense to the norms of civilization are infamous."[154] Unequivocally stating that Iraq had substantial weapons of mass destruction, McCain stated that Iraq was "a clear and present danger to the United States of America."[154] Accordingly he voted for the Iraq War Resolution in October 2002.[154] Both before and immediately after the Iraq War started in March 2003, McCain agreed with the Bush administration's assertions that the U.S. forces would be treated as liberators by most of the Iraqi people.[164] In May 2003, McCain voted against the Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003, the second round of Bush tax cuts which served to extend and accelerate the first (which he had also voted against), saying it was unwise at a time of war.[156] By November 2003, after a trip to Iraq, McCain was publicly questioning Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld's handling of the Iraq War, saying that "All of the trends are in the wrong direction" and that more U.S. troops were needed to handle the deteriorating situation in the Sunni Triangle.[165] By December 2004, McCain was bluntly announcing that he had lost confidence in Rumsfeld.[166]

In the 2004 U.S. presidential election, McCain was once again frequently mentioned for the vice-presidential slot, only this time as part of the Democratic ticket underneath nominee John Kerry.[167][168] Kerry and McCain had been close since their work on the early 1990s Senate Select Committee on POW/MIA Affairs, and the pairing was seen as having great allure to independent voters,[167] with polls seeming to confirm the notion.[168] In June 2004, it was reported that Kerry had informally offered the slot to McCain several times, but McCain had declined, either on grounds that it would be infeasible and weaken the presidency[168] or that the vice-presidency held no appeal for McCain.[167] McCain's office formally denied that any vice-presidential offer had taken place.[168] At the 2004 Republican National Convention, McCain enthusiastically supported Bush for re-election,[169] praising Bush's management of the War on Terror since the September 11 attacks.[169] At the same time, McCain defended Kerry by labeling the Swift Boat Veterans for Truth campaign against Kerry's Vietnam war record as "dishonest and dishonorable" and urging the Bush campaign to condemn it.[170] By August 2004, McCain had the best favorable-to-unfavorable rating (55 percent to 19 percent) of any national politician.[169]

McCain was himself up for re-election as Senator in 2004. There was some talk of Representative Jeff Flake mounting a Republican primary challenge against McCain;[166] Stephen Moore, president of the ideologically-oriented Club for Growth (which attempts to defeat those it considers Republican in Name Only), led talk for the prospect,[171] saying "Our members loathe John McCain."[172] Flake decided not to do it, later saying "I would have been whipped."[171] In the general election McCain had his biggest margin of victory yet, garnering 77 percent of the vote against little-known Democrat Stuart Starky, an eighth grade math teacher.[173] whom The Arizona Republic termed a "sacrificial lamb".[166] Exit polls showed that McCain even won a majority of the votes cast by Democrats.[174]

Following his 2000 presidential campaign, McCain became a frequent sight on entertainment programs in the television and film worlds, and even more so after 2004.[166] He hosted the October 12, 2002, episode of Saturday Night Live, making him the third U.S. Senator after Paul Simon and George McGovern, to host the show.

2005 - 2007

In the comedic news realm, he has been a regular guest on The Daily Show, and is a good friend of host Jon Stewart;[175] as of 2006 he had been on that show eleven times, more than anyone else. McCain appeared in slightly edgy bits on Late Night with Conan O'Brien,[176] and also appeared several times on The Tonight Show with Jay Leno and the Late Show with David Letterman.[177] McCain made a brief cameo on the television show 24 in 2006[177] and also made a cameo in the 2005 summer movie Wedding Crashers. In the more serious realm, a television film entitled Faith Of My Fathers, based on McCain's memoir of his experiences as a POW, aired on Memorial Day, 2005, on A&E.[178] McCain is also interviewed in the 2005 documentary Why We Fight by Eugene Jarecki.[179]

On judicial appointments, McCain was long a believer in judges who “would strictly interpret the Constitution,” and accordingly over the years would support the confirmations of Robert Bork, Clarence Thomas, John Roberts, and Samuel Alito.[180] McCain also drew the ire of the originalist and similar legal movements in the U.S. in May 2005, however, when he led the so-called "Gang of 14" in the Senate, which established a compromise that preserved the ability of senators to filibuster judicial nominees, but only in "extraordinary circumstances." Breaking from his 2001 and 2003 votes, McCain supported the Bush tax cut extension in May 2006, known as the Tax Increase Prevention and Reconciliation Act of 2005, saying not to do so would amount to a tax increase.[156] Working with Democratic Senator Ted Kennedy, McCain was a strong proponent of comprehensive immigration reform, which would involve legalization, guest worker programs, and border enforcement components: the Secure America and Orderly Immigration Act was never voted on in 2005, while the Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act of 2006 passed the Senate in May 2006 but then failed in the House.[166] In June 2007, President Bush, McCain and others made the strongest push yet for such a bill, the Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act of 2007, but it aroused tremendous grassroots opposition among talk radio listeners and others as an "amnesty" program, and twice failed to gain cloture in the Senate and thus failed.

Owing to his time as a POW, McCain has been recognized for his sensitivity to the detention and interrogation of detainees in the War on Terror. On October 3, 2005, McCain introduced the McCain Detainee Amendment to the Defense Appropriations bill for 2005. On October 5, 2005, the United States Senate voted 90-9 to support the amendment.[181] The amendment prohibits inhumane treatment of prisoners, including prisoners at Guantanamo Bay, by confining interrogations to the techniques in FM 34-52 Intelligence Interrogation.

Although Bush had threatened to veto the bill if McCain's language was included,[182] the President announced on December 15, 2005 that he accepted McCain's terms and would "make it clear to the world that this government does not torture and that we adhere to the international convention of torture, whether it be here at home or abroad."[183] Bush made clear his interpretation of this legislation on in a signing statement, reserving what he interpreted to be his Presidential constitutional authority in order to avoid further terrorist attacks.[184] Meanwhile, McCain continued questioning the progress of the war in Iraq. In September 2005, he questioned Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Richard Myers' habit of optimistic outlooks on the war's progress: "Things have not gone as well as we had planned or expected, nor as we were told by you, General Myers."[185] In August 2006 he criticized the administration for continually understating the effectiveness of the insurgency: "We [have] not told the American people how tough and difficult this could be."[166] From the beginning McCain strongly supported the Iraq troop surge of 2007;[186] the strategy's opponents labeled it "McCain's plan"[187] and University of Virginia political science professor Larry Sabato said, "McCain owns Iraq just as much as Bush does now."[166] The surge and the war were quite unpopular during most of the year, even within the Republican Party,[17] as McCain's presidential campaign was underway; faced with the consequences, McCain frequently responded, "I would much rather lose a campaign than a war."[188]

2008 presidential campaign

Template:Future election candidate

McCain established his presidential exploratory committee on November 15, 2006,[166] then announced he was seeking the 2008 Presidential nomination from the Republican Party on the February 28, 2007, telecast of the Late Show With David Letterman.[189][190] McCain officially started his 2008 presidential campaign on April 25, 2007, in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Should McCain win in 2008, he would be the oldest person to assume the Presidency in history at initial ascension to office, being 72 years old and surpassing Ronald Reagan, who was 69 years old at his inauguration following the 1980 election. He has dismissed concerns about his age and past health concerns (malignant melanoma in 2000), stating in 2005 that his health was "excellent."[191][192] In the event of his victory in 2008, he would also become the first President of the United States to be born in a U.S. territory outside of the current 50 states.

McCain's oft-cited strengths[193] as a presidential candidate for 2008 included national name recognition, sponsorship of major lobbying and campaign finance reform initiatives, leadership in exposing the Abramoff scandal,[194] his well-known military service and experience as a POW, his experience from the 2000 presidential campaign, extensive fundraising abilities, and strong advocacy for President Bush's re-election campaign in 2004. During the 2006 election cycle, McCain attended 346 events[13] and raised more than $10.5 million on behalf of Republican candidates. He also donated nearly $1.5 million to federal, state and county parties. In a bid to finally gain support from the Christian right, McCain gave the May 2006 commencement address at Jerry Falwell's Liberty University. During his 2000 presidential bid, McCain had called Falwell an "agent of intolerance"; McCain now said that Falwell was no longer as divisive and the two have discussed their shared values.[195] McCain was also more willing to ask business and industry for campaign contributions, counting more lobbyists as fundraisers than any other candidate,[196] while maintaining adamantly that such contributions would not affect any senatorial decisions he made.[196]

McCain's second-quarter 2007 fundraising totals fell from $13.6 million in the first quarter to $11.2 million in the second, and expenses continuing such that only $2 million cash was on hand with about $1 million[197] in debts. Both McCain supporters and political observers pointed to McCain's support for the Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act of 2007, very unpopular among the Republican base electorate, as a primary cause of his fundraising problems. Large-scale campaign staff downsizing took place in early July, with 50 to 100 staffers let go and others taking pay cuts or switching to no pay. McCain's aides said the campaign was considering taking public matching funds, and would focus its efforts on the early primary and caucus states. McCain however said he was not considering dropping out of the race.[198][199] Campaign shakeups reached the top level on July 10, 2007, when his campaign manager and campaign chief strategist both departed.[200]

McCain subsequently resumed his familiar position as a political underdog, embracing a "Living Off the Land" strategy that called for McCain to ride the Straight Talk Express and take advantage of free media such as debates and sponsored events.[201] By December 2007, the Republican race was quite unsettled, with none of the top-tier candidates dominating the race and all of them possessing major vulnerabilities with different elements of the Republican base electorate.[202] McCain was showing a resurgence, in particular with renewed strength in New Hampshire — scene of his 2000 triumph — and was bolstered further by the endorsements of The Boston Globe, the Manchester Union-Leader, and almost two dozen other state newspapers,[203] as well as from Democratic Senator Joe Lieberman.[204] All of this paid off when McCain won the New Hampshire primary on January 8, 2008, beating former Governor of Massachusetts Mitt Romney in a close contest, to once again become one of the front-runners in the race.[205] On January 19, 2008, McCain placed first in the South Carolina primary, narrowly defeating former Governor of Arkansas Mike Huckabee, and thereby reversing his loss there in 2000.[206] He followed this up with another win a week later in the Florida primary,[207] beating Romney again in close, negative and attack-filled contest, thereby making him the front-runner in the nomination race.[207] Following this victory, rival Rudy Giuliani announced he was dropping out of the race and cast his support for McCain's candidacy.[208] As of February 2, 2008, McCain had an overall 97-92 lead over Romney in delegates to the 2008 Republican National Convention. [209] On February 5, Super Tuesday, McCain won both the majority of states and delegates in the Republican primaries, giving him a commanding lead toward the Republican nomination. With Mitt Romney's departure from the race on February 7,[210] McCain is widely regarded as the presumptive Republican nominee, although Mike Huckabee and Ron Paul remain in the race.

Political positions

Assessments by political interest groups

A lifelong Republican,[211] McCain has received a lifetime American Conservative Union rating of 82 percent, with a moderate 65 percent rating for 2006.[212]

In the 2000 elections, many thought of Bush as the more conservative candidate and McCain as the more moderate candidate. In fact, according to Voteview.com, McCain's voting record in the 109th Congress was the second most conservative among senators.[213] However, his voting record during the 107th Congress, from January 2001 through November 2002, placed him as the sixth most liberal Republican senator, according to the same analysis.[214]

Positions on specific issues

McCain has many traditionally Republican views. He has a strong conservative voting record on pro-life[215] and free trade issues, favors private social security accounts, and opposes an expanded government role in health care. McCain also supports school vouchers, capital punishment, mandatory sentencing, and welfare reform. He is generally regarded as a hawk in foreign policy. When a questioner said, "President Bush has talked about our staying in Iraq for 50 years." McCain responded, "Make it a hundred. We've been in Japan for 60 years, we've been in South Korea for 50 years or so. That'd be fine with me as long as Americans are not being injured or harmed or wounded or killed. That's fine with me. I hope it will be fine with you if we maintain a presence in a very volatile part of the world where Al Qaeda is training, recruiting, equipping, and motivating people every single day."[216]

Nevertheless, McCain has supported liberal legislation opposed by his own party and has been called a "maverick" by certain members of the American media.[217] Arizona Republic columnist and RealClearPolitics contributor Robert Robb, using a formulation devised by William F. Buckley, describes McCain as "conservative" but not "a conservative", meaning that while McCain usually tends towards conservative positions, he is not "anchored by the philosophical tenets of modern American conservatism."[218] McCain declined to sign the pledge put forth by Americans for Tax Freedom not to impose any new taxes or increase existing taxes.[219]

McCain's reputation as a maverick stems primarily from his authorship of the McCain-Feingold Act for campaign finance reform and his stance on illegal immigration.[220] McCain's views about abortion have also fluctuated; in 1999, he said of Roe v. Wade, "in the short term, or even the long term, I would not support repeal of Roe v. Wade,"[221] but in 2007 McCain stated "It should be overturned."[222]

In 2007, McCain co-sponsored controversial legislation with Senator Ted Kennedy known as the Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act of 2007 which would have allowed tens of millions of illegal immigrants already in the United States a path to citizenship. Further, the Washington Post reports that McCain and South Carolina Senator Lindsey Graham "first checked with Mr. Kennedy before deciding to vote with the Massachusetts Democrat on an amendment to the Senate bill".[223]

McCain has been a lead sponsor of gun control legislation as well as what organizations including Gun Owners of America argue are restrictions on the free speech of pro-Second Amendment organizations[224] even earning an F- rating from Gun Owners of America. Yet in the past McCain had voted against the passage and renewal of the Federal Assault Weapons Ban and the Brady Bill.[225][226]

McCain voted against President Bush's tax cuts in 2001 and 2003, though he voted to extend the tax breaks in 2005.[227]

McCain has been a strong opponent of the Bush administration's use of "enhanced interrogation techniques" in the War on Terror, and has specifically referred to waterboarding as torture.[228][229] He has also said that he intends to "immediately close" the Guantanamo Bay detainment camp.[230]

Cultural and political image