Nantes

Nantes

| |

|---|---|

Prefecture and commune | |

Top to bottom, left to right: the Loire in central Nantes; the Château des ducs de Bretagne; the passage Pommeraye, and the île de Nantes between the branches of the Loire | |

| Motto(s): | |

| Coordinates: 47°13′05″N 1°33′10″W / 47.2181°N 1.5528°W | |

| Country | France |

| Region | Pays de la Loire |

| Department | Loire-Atlantique |

| Arrondissement | Nantes |

| Canton | 7 cantons |

| Intercommunality | Nantes Métropole |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (2020–2026) | Johanna Rolland[1] (PS) |

| Area 1 | 65.19 km2 (25.17 sq mi) |

| • Urban (2018) | 498.6 km2 (192.5 sq mi) |

| • Metro (2018) | 3,471.1 km2 (1,340.2 sq mi) |

| Population (2021)[2] | 323,204 |

| • Rank | 6th in France |

| • Density | 5,000/km2 (13,000/sq mi) |

| • Urban (2018) | 655,187 |

| • Urban density | 1,300/km2 (3,400/sq mi) |

| • Metro (2018) | 997,222 |

| • Metro density | 290/km2 (740/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Nantais (masculine) Nantaise (feminine) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| INSEE/Postal code | 44109 /44000, 44100, 44200 and 44300 |

| Dialling codes | 02 |

| Website | metropole.nantes.fr |

| 1 French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km2 (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. | |

Nantes (/nɒ̃t/, US also /nɑːnt(s)/,[3][4][5] French: [nɑ̃t] ; Gallo: Naunnt or Nantt [nɑ̃(ː)t];[6] Template:Lang-br [ˈnãunət])[7] is a city in Loire-Atlantique of France on the Loire, 50 km (31 mi) from the Atlantic coast. The city is the sixth largest in France, with a population of 320,732 in the proper Nantes and a metropolitan area of nearly 1 million inhabitants (2020).[8] With Saint-Nazaire, a seaport on the Loire estuary, Nantes forms one of the main north-western French metropolitan agglomerations.

It is the administrative seat of the Loire-Atlantique department and the Pays de la Loire region, one of 18 regions of France. Nantes belongs historically and culturally to Brittany, a former duchy and province, and its omission from the modern administrative region of Brittany is controversial.

Nantes was identified during classical antiquity as a port on the Loire. It was the seat of a bishopric at the end of the Roman era before it was conquered by the Bretons in 851. Although Nantes was the primary residence of the 15th-century dukes of Brittany, Rennes became the provincial capital after the 1532 union of Brittany and France. During the 17th century, after the establishment of the French colonial empire, Nantes gradually became the largest port in France and was responsible for nearly half of the 18th-century French Atlantic slave trade. The French Revolution resulted in an economic decline, but Nantes developed robust industries after 1850 (chiefly in shipbuilding and food processing). Deindustrialisation in the second half of the 20th century spurred the city to adopt a service economy.

In 2020, the Globalization and World Cities Research Network ranked Nantes as a Gamma world city. It is the third-highest-ranking city in France, after Paris and Lyon. The Gamma category includes cities such as Algiers, Orlando, Porto, Turin and Leipzig.[9] Nantes has been praised for its quality of life, and it received the European Green Capital Award in 2013.[10] The European Commission noted the city's efforts to reduce air pollution and CO2 emissions, its high-quality and well-managed public transport system and its biodiversity, with 3,366 hectares (8,320 acres) of green space and several protected Natura 2000 areas.[11]

Etymology

Nantes is named after a tribe of Gaul, the Namnetes, who established a settlement between the end of the second century and the beginning of the first century BC on the north bank of the Loire near its confluence with the Erdre. The origin of the name Namnetes is uncertain, but is thought to come from the Gaulish root *nant- 'river, stream'[12] (from the pre-Celtic root *nanto 'valley')[13] or from Amnites, another tribal name possibly meaning 'men of the river'.[14]

Its first recorded name was by the Greek writer Ptolemy, who referred to the settlement as Κονδηούινκον (Kondēoúinkon) and Κονδιούινκον (Kondioúinkon)[A]—which might be read as Κονδηούικον (Kondēoúikon)—in his treatise, Geography.[15] The name was Latinised during the Gallo-Roman period as Condevincum (the most common form), Condevicnum,[16] Condivicnum and Condivincum.[17] Although its origins are unclear, Condevincum seems to be related to the Gaulish word condate 'confluence'.[18]

The Namnete root of the city's name was introduced at the end of the Roman period, when it became known as Portus Namnetum "port of the Namnetes"[19] and civitas Namnetum 'city of the Namnetes'.[18] Like other cities in the region (including Paris), its name was replaced during the fourth century with a Gaulish one: Lutetia became Paris (city of the Parisii), and Darioritum became Vannes (city of the Veneti).[20] Nantes's name continued to evolve, becoming Nanetiæ and Namnetis during the fifth century and Nantes after the sixth, via syncope (suppression of the middle syllable).[21]

Modern pronunciation and nicknames

Nantes is pronounced [nɑ̃t], and the city's inhabitants are known as Nantais [nɑ̃tɛ]. In Gallo, the oïl language traditionally spoken in the region around Nantes, the city is spelled Naunnt or Nantt and pronounced identically to French, although northern speakers use a long [ɑ̃].[6] In Breton, Nantes is known as Naoned or an Naoned,[22] the latter of which is less common and reflects the more-frequent use of articles in Breton toponyms than in French ones.[23]

Nantes's historical nickname was "Venice of the West" (Template:Lang-fr), a reference to the many quays and river channels in the old town before they were filled in during the 1920s and 1930s.[24] The city is commonly known as la Cité des Ducs "the City of the Dukes [of Brittany]" for its castle and former role as a ducal residence.[25]

History

Prehistory and antiquity

The first inhabitants of what is now Nantes settled during the Bronze Age, later than in the surrounding regions (which have Neolithic monuments absent from Nantes). Its first inhabitants were apparently attracted by small iron and tin deposits in the region's subsoil.[26] The area exported tin, mined in Abbaretz and Piriac, as far as Ireland.[27] After about 1,000 years of trading, local industry appeared around 900 BC; remnants of smithies dated to the eighth and seventh centuries BC have been found in the city.[28] Nantes may have been the major Gaulish settlement of Corbilo, on the Loire estuary, which was mentioned by the Greek historians Strabo and Polybius.[28]

Its history from the seventh century to the Roman conquest in the first century BC is poorly documented, and there is no evidence of a city in the area before the reign of Tiberius in the first century AD.[29] During the Gaulish period it was the capital of the Namnetes people, who were allied with the Veneti[30] in a territory extending to the northern bank of the Loire. Rivals in the area included the Pictones, who controlled the area south of the Loire in the city of Ratiatum (present-day Rezé) until the end of the second century AD. Ratiatum, founded under Augustus, developed more quickly than Nantes and was a major port in the region. Nantes began to grow when Ratiatum collapsed after the Germanic invasions.[31]

Because tradesmen favoured inland roads rather than Atlantic routes,[32] Nantes never became a large city under Roman occupation. Although it lacked amenities such as a theatre or an amphitheatre, the city had sewers, public baths and a temple dedicated to Mars Mullo.[29] After an attack by German tribes in 275, Nantes's inhabitants built a wall; this defense also became common in surrounding Gaulish towns.[33] The wall in Nantes, enclosing 16 hectares (40 acres), was one of the largest in Gaul.[34]

Christianity was introduced during the third century. The first local martyrs (Donatian and Rogatian) were executed in 288–290,[35] and a cathedral was built during the fourth century.[36][31]

Middle Ages

Like much of the region, Nantes was part of the Roman Empire during the early Middle Ages. Although many parts of Brittany experienced significant Breton immigration (loosening ties to Rome), Nantes remained allied with the empire until its collapse in the fifth century.[37] Around 490, the Franks under Clovis I captured the city (alongside eastern Brittany) from the Visigoths after a sixty-day siege;[38] it was used as a stronghold against the Bretons. Under Charlemagne in the eighth century the town was the capital of the Breton March, a buffer zone protecting the Carolingian Empire from Breton invasion. The first governor of the Breton March was Roland, whose feats were mythologized in the body of literature known as the Matter of France.[39] After Charlemagne's death in 814, Breton armies invaded the March and fought the Franks. Nominoe (a Breton) became the first duke of Brittany, seizing Nantes in 850. Discord marked the first decades of Breton rule in Nantes as Breton lords fought among themselves, making the city vulnerable to Viking incursions. The most spectacular Viking attack in Nantes occurred in 843, when Viking warriors killed the bishop but did not settle in the city at that time.[39] Nantes became part of the Viking realm in 919, but the Norse were expelled from the town in 937 by Alan II, Duke of Brittany.[40]

Feudalism took hold in France during the 10th and 11th centuries, and Nantes was the seat of a county founded in the ninth century. Until the beginning of the 13th century, it was the subject of succession crises which saw the town pass several times from the Dukes of Brittany to the counts of Anjou (of the House of Plantagenet).[41] During the 14th century, Brittany experienced a war of succession which ended with the accession of the House of Montfort to the ducal throne. The Montforts, seeking emancipation from the suzerainty of the French kings, reinforced Breton institutions. They chose Nantes, the largest town in Brittany (with a population of over 10,000), as their main residence and made it the home of their council, their treasury and their chancery.[42][43] Port traffic, insignificant during the Middle Ages, became the city's main activity.[44] Nantes began to trade with foreign countries, exporting salt from Bourgneuf,[44] wine, fabrics and hemp (usually to the British Isles).[45] The 15th century is considered Nantes's first golden age.[46][47] The reign of Francis II saw many improvements to a city in dire need of repair after the wars of succession and a series of storms and fires between 1387 and 1415. Many buildings were built or rebuilt (including the cathedral and the castle), and the University of Nantes, the first in Brittany, was founded in 1460.[48]

Modern era

The marriage of Anne of Brittany to Charles VIII of France in 1491 began the unification of the duchy of Brittany with the French crown which was ratified by Francis I of France in 1532. The union ended a long feudal conflict between France and Brittany, reasserting the king's suzerainty over the Bretons. In return for surrendering its independence, Brittany retained its privileges.[49] Although most Breton institutions were maintained, the unification favoured Rennes (the site of ducal coronations). Rennes received most legal and administrative institutions, and Nantes kept a financial role with its Chamber of Accounts.[50] During the French Wars of Religion from 1562 to 1598, the city was a Catholic League stronghold. The Duke of Mercœur, governor of Brittany, strongly opposed the succession of the Protestant Henry IV of France to the throne of France in 1589. The Duke created an independent government in Nantes, allying with Spain and pressing for independence from France. Despite initial successes with Spanish aid, in 1598 he submitted to Henry IV (who had by then converted to Catholicism); the Edict of Nantes (legalising Protestantism in France) was signed in the town, concluding the French wars of religion. Nonetheless, the town remained fervently Catholic (by contrast to nearby La Rochelle), and the local Protestant community did not number more than 1,000.[51]

Coastal navigation and the export of locally produced goods (salt, wine and fabrics) dominated the local economy around 1600.[45] During the mid-17th century, the siltation of local salterns and a fall in wine exports compelled Nantes to find other activities.[52] Local shipowners began importing sugar from the French West Indies (Martinique, Guadeloupe and Saint-Domingue) in the 1640s, which became very profitable after protectionist reforms implemented by Jean-Baptiste Colbert prevented the import of sugar from Spanish colonies (which had dominated the market).[53] In 1664 Nantes was France's eighth-largest port, and it was the largest by 1700.[54] Plantations in the colonies needed labour to produce sugar, rum, tobacco, indigo dye, coffee and cocoa, and Nantes shipowners began trading African slaves in 1706.[55] The port was part of the triangular trade: ships went to West Africa to buy slaves, slaves were sold in the French West Indies, and the ships returned to Nantes with sugar and other exotic goods.[45] From 1707 to 1793, Nantes was responsible for 42 percent of the French slave trade; its merchants sold about 450,000 African slaves in the West Indies.[56]

Manufactured goods were more lucrative than raw materials during the 18th century. There were about fifteen sugar refineries in the city around 1750 and nine cotton mills in 1786.[57] Nantes and its surrounding area were the main producers of French printed cotton fabric during the 18th century,[58] and the Netherlands was the city's largest client for exotic goods.[57] Although trade brought wealth to Nantes, the city was confined by its walls; their removal during the 18th century allowed it to expand. Neoclassical squares and public buildings were constructed, and wealthy merchants built sumptuous hôtels particuliers.[59][60]

French Revolution

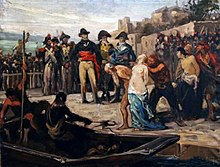

The French Revolution initially received some support in Nantes, a bourgeois city rooted in private enterprise. On 18 July 1789, locals seized the Castle of the Dukes of Brittany in an imitation of the storming of the Bastille.[61] Rural western France, Catholic and conservative, strongly opposed the abolition of the monarchy and the submission of the clergy.[62] A rebellion in the neighbouring Vendée began in 1793, quickly spreading to surrounding regions. Nantes was an important Republican garrison on the Loire en route to England. On 29 June 1793, 30,000 Royalist troops from Vendée attacked the city on their way to Normandy (where they hoped to receive British support). Twelve thousand Republican soldiers resisted and the Battle of Nantes resulted in the death of Royalist leader Jacques Cathelineau.[63] Three years later another Royalist leader, François de Charette, was executed in Nantes.[64]

After the Battle of Nantes, the National Convention (which had founded the First French Republic) decided to purge the city of its anti-revolutionary elements. Nantes was seen by the convention as a corrupt merchant city; the local elite was less supportive of the French Revolution, since its growing centralisation reduced their influence.[61] From October 1793 to February 1794, deputy Jean-Baptiste Carrier presided over a revolutionary tribunal notorious for cruelty and ruthlessness. Between 12,000 and 13,000 people (including women and children) were arrested, and 8,000 to 11,000 died of typhus or were executed by the guillotine, shooting or drowning. The Drownings at Nantes were intended to kill large numbers of people simultaneously, and Carrier called the Loire "the national bathtub".[61]

The French Revolution was disastrous for the local economy. The slave trade nearly disappeared because of the abolition of slavery and the independence of Saint-Domingue, and Napoleon's Continental Blockade decimated trade with other European countries. Nantes never fully recovered its 18th-century wealth; the port handled 43,242 tons of goods in 1807, down from 237,716 tons in 1790.[45]

Industries

Outlawed by the French Revolution, the slave trade re-established itself as Nantes's major source of income in the first decades of the 19th century.[45] It was the last French port to conduct the illegal Atlantic trade, continuing it until about 1827.[65] The 19th-century slave trade may have been as extensive as that of the previous century, with about 400,000 slaves deported to the colonies.[66] Businessmen took advantage of local vegetable production and Breton fishing to develop a canning industry during the 1820s,[67] but canning was eclipsed by sugar imported from Réunion in the 1840s and 1850s. Nantes tradesmen received a tax rebate on Réunion sugar, which was lucrative until disease devastated the cane plantations in 1863.[68] By the mid-19th century, Le Havre and Marseille were the two main French ports; the former traded with America and the latter with Asia. They had embraced the Industrial Revolution, thanks to Parisian investments; Nantes lagged behind, struggling to find profitable activities. Nostalgic for the pre-revolutionary golden age, the local elite had been suspicious of political and technological progress during the first half of the 19th century. In 1851, after much debate and opposition, Nantes was connected to Paris by the Tours–Saint-Nazaire railway.[65]

Nantes became a major industrial city during the second half of the 19th century with the aid of several families who invested in successful businesses. In 1900, the city's two main industries were food processing and shipbuilding. The former, primarily the canning industry, included the biscuit manufacturer LU and the latter was represented by three shipyards which were among the largest in France. These industries helped maintain port activity and facilitated agriculture, sugar imports, fertilizer production, machinery and metallurgy, which employed 12,000 people in Nantes and its surrounding area in 1914.[69] Because large, modern ships had increased difficulty traversing the Loire to reach Nantes, a new port in Saint-Nazaire had been established at the mouth of the estuary in 1835. Saint-Nazaire, primarily developed for goods to be transhipped before being sent to Nantes, also built rival shipyards. Saint-Nazaire surpassed Nantes in port traffic for the first time in 1868.[70] Reacting to the growth of the rival port, Nantes built a 15-kilometre-long (9.3 mi) canal parallel to the Loire to remain accessible to large ships. The canal, completed in 1892, was abandoned in 1910 because of the efficient dredging of the Loire between 1903 and 1914.[71]

Land reclamation

At the beginning of the 20th century, the river channels flowing through Nantes were increasingly perceived as hampering the city's comfort and economic development. Sand siltation required dredging, which weakened the quays; one quay collapsed in 1924. Embankments were overcrowded with railways, roads and tramways. Between 1926 and 1946, most of the channels were filled in and their water diverted. Large thoroughfares replaced the channels, altering the urban landscape. Feydeau and Gloriette Islands in the old town were attached to the north bank, and the other islands in the Loire were formed into the Isle of Nantes.[72]

When the land reclamation was almost complete, Nantes was shaken by the air raids of the Second World War. The city was captured by Nazi Germany on 18 June 1940, during the Battle of France.[73] Forty-eight civilians were executed in Nantes in 1941 in retaliation for the assassination of German officer Karl Hotz. They are remembered as "the 50 hostages" because the Germans initially planned to kill 50 people.[74] British bombs first hit the city in August 1941 and May 1942. The main attacks occurred on 16 and 23 September 1943, when most of Nantes's industrial facilities and portions of the city centre and its surrounding area were destroyed by American bombs.[72] About 20,000 people were left homeless by the 1943 raids, and 70,000 subsequently left the city. Allied raids killed 1,732 people and destroyed 2,000 buildings in Nantes, leaving a further 6,000 buildings unusable.[75] The Germans abandoned the city on 12 August 1944, and it was recaptured without a fight by the French Forces of the Interior and the U.S. Army.[76]

Postwar

The postwar years were a period of strikes and protests in Nantes. A strike organised by the city's 17,500 metallurgists during the summer of 1955 to protest salary disparities between Paris and the rest of France deeply impacted the French political scene, and their action was echoed in other cities.[77] Nantes saw other large strikes and demonstrations during the May 1968 events, when marches drew about 20,000 people into the streets.[78] The 1970s global recession brought a large wave of deindustrialisation to France, and Nantes saw the closure of many factories and the city's shipyards.[79] The 1970s and 1980s were primarily a period of economic stagnation for Nantes. During the 1980s and 1990s its economy became service-oriented and it experienced economic growth under Jean-Marc Ayrault, the city's mayor from 1989 to 2012. Under Ayrault's administration, Nantes used its quality of life to attract service firms. The city developed a rich cultural life, advertising itself as a creative place near the ocean. Institutions and facilities (such as its airport) were re-branded as "Nantes Atlantique" to highlight this proximity. Local authorities have commemorated the legacy of the slave trade, promoting dialogue with other cultures.[80]

Nantes has been noted in recent years for its climate of social unrest, marked by frequent and often violent clashes between protesters and police. Tear gas is frequently deployed during protests.[81] The city has a significant ultra-left radical scene, owing in part to the proximity of the ZAD de Notre-Dame-des-Landes.[82] Masked rioters have repeatedly ransacked shops, offices and public transport infrastructure.[83][84][85][86] The death of Steve Maia Caniço in June 2019 has led to accusations of police brutality and cover-ups.[87]

Geography

Location

Nantes is in north-western France, near the Atlantic Ocean and 340 kilometres (210 miles) south-west of Paris. Bordeaux, the other major metropolis of western France, is 275 kilometres (171 miles) south. Nantes and Bordeaux share positions at the mouth of an estuary, and Nantes is on the Loire estuary.[88]

The city is at a natural crossroads between the ocean in the west, the centre of France (towards Orléans) in the east, Brittany in the north and Vendée (on the way to Bordeaux) in the south.[89] It is an architectural junction; northern French houses with slate roofs are north of the Loire, and Mediterranean dwellings with low terracotta roofs dominate the south bank.[90][91] The Loire is also the northern limit of grape culture. Land north of Nantes is dominated by bocage and dedicated to polyculture and animal husbandry, and the south is renowned for its Muscadet vineyards and market gardens.[92] The city is near the geographical centre of the land hemisphere, identified in 1945 by Samuel Boggs as near the main railway station (around 47°13′N 1°32′W / 47.217°N 1.533°W).[93]

Hydrology

The Loire is about 1,000 kilometres (620 miles) long and its estuary, beginning in Nantes, is 60 kilometres (37 miles) in length.[89] The river's bed and banks have changed considerably over a period of centuries. In Nantes the Loire had divided into a number of channels, creating a dozen islands and sand ridges. They facilitated crossing the river, contributing to the city's growth. Most of the islands were protected with levees during the modern era, and they disappeared in the 1920s and 1930s when the smallest waterways were filled in. The Loire in Nantes now has only two branches, one on either side of the Isle of Nantes.[90]

The river is tidal in the city, and tides are observed about 30 kilometres (19 miles) further east.[89] The tidal range can reach 6 metres (20 feet) in Nantes, larger than at the mouth of the estuary.[94] This is the result of 20th-century dredging to make Nantes accessible by large ships; tides were originally much weaker. Nantes was at the point where the river current and the tides cancelled each other out, resulting in siltation and the formation of the original islands.[95][96][97]

The city is at the confluence of two tributaries. The Erdre flows into the Loire from its north bank, and the Sèvre Nantaise flows into the Loire from its south bank. These two rivers initially provided natural links with the hinterland. When the channels of the Loire were filled, the Erdre was diverted in central Nantes and its confluence with the Loire was moved further east. The Erdre includes Versailles Island, which became a Japanese garden during the 1980s. It was created in the 19th century with fill from construction of the Nantes–Brest canal.[98]

Geology

Nantes is built on the Armorican Massif, a range of weathered mountains which may be considered the backbone of Brittany. The mountains, stretching from the end of the Breton peninsula to the outskirts of the sedimentary Paris Basin, are composed of several parallel ridges of Ordovician and Cadomian rocks. Nantes is where one of these ridges, the Sillon de Bretagne, meets the Loire. It passes through the western end of the old town, forming a series of cliffs above the quays.[99] The end of the ridge, the Butte Sainte-Anne, is a natural landmark 38 metres (125 feet) above sea level; its foothills are at an elevation of 15 metres (49 feet).[100]

The Sillon de Bretagne is composed of granite; the rest of the region is a series of low plateaus covered with silt and clay, with mica schist and sediments found in lower areas. Much of the old town and all of the Isle of Nantes consist of backfill.[99] Elevations in Nantes are generally higher in the western neighbourhoods on the Sillon, reaching 52 metres (171 feet) in the north-west.[100] The Erdre flows through a slate fault.[90] Eastern Nantes is flatter, with a few hills reaching 30 metres (98 feet).[100] The city's lowest points, along the Loire, are 2 metres (6.6 feet) above sea level.[100]

Climate

Nantes has an oceanic climate (Köppen: Cfb)[101][102] influenced by its proximity to the Atlantic Ocean. West winds produced by cyclonic depressions in the Atlantic dominate, and north and north-west winds are also common.[103] Slight variations in elevation make fog common in valleys, and slopes oriented south and south-west have good insolation. Winters are cool and rainy, with an average temperature of 6 °C (43 °F); snow is rare. Summers are warm, with an average temperature of 20 °C (68 °F). Rain is abundant throughout the year, with an annual average of 820 millimetres (32 inches). The climate in Nantes is suitable for growing a variety of plants, from temperate vegetables to exotic trees and flowers imported during the colonial era.[92][104]

| Climate data for Nantes-Bouguenais (Nantes Atlantique Airport), elevation: 27 m or 89 ft, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1945–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 18.2 (64.8) |

22.6 (72.7) |

24.2 (75.6) |

28.3 (82.9) |

32.8 (91.0) |

39.1 (102.4) |

42.0 (107.6) |

39.6 (103.3) |

34.3 (93.7) |

30.2 (86.4) |

21.8 (71.2) |

18.4 (65.1) |

42.0 (107.6) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 14.3 (57.7) |

15.9 (60.6) |

19.9 (67.8) |

23.4 (74.1) |

27.7 (81.9) |

31.7 (89.1) |

33.1 (91.6) |

33.0 (91.4) |

29.0 (84.2) |

23.3 (73.9) |

18.0 (64.4) |

14.5 (58.1) |

35.0 (95.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 9.3 (48.7) |

10.5 (50.9) |

13.5 (56.3) |

16.2 (61.2) |

19.6 (67.3) |

23.0 (73.4) |

25.1 (77.2) |

25.4 (77.7) |

22.4 (72.3) |

17.6 (63.7) |

12.9 (55.2) |

9.8 (49.6) |

17.1 (62.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6.4 (43.5) |

6.7 (44.1) |

9.2 (48.6) |

11.4 (52.5) |

14.7 (58.5) |

17.8 (64.0) |

19.7 (67.5) |

19.8 (67.6) |

17.1 (62.8) |

13.5 (56.3) |

9.4 (48.9) |

6.7 (44.1) |

12.7 (54.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 3.4 (38.1) |

3.0 (37.4) |

4.9 (40.8) |

6.6 (43.9) |

9.8 (49.6) |

12.7 (54.9) |

14.3 (57.7) |

14.2 (57.6) |

11.8 (53.2) |

9.5 (49.1) |

5.9 (42.6) |

3.7 (38.7) |

8.3 (46.9) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | −4.3 (24.3) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

0.3 (32.5) |

3.7 (38.7) |

7.1 (44.8) |

9.6 (49.3) |

8.9 (48.0) |

5.9 (42.6) |

2.3 (36.1) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

−3.7 (25.3) |

−6.0 (21.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −13.0 (8.6) |

−15.6 (3.9) |

−9.6 (14.7) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

3.8 (38.8) |

5.8 (42.4) |

5.6 (42.1) |

2.8 (37.0) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

−6.8 (19.8) |

−10.8 (12.6) |

−15.6 (3.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 87.9 (3.46) |

67.5 (2.66) |

58.4 (2.30) |

58.3 (2.30) |

61.0 (2.40) |

48.5 (1.91) |

44.2 (1.74) |

50.3 (1.98) |

59.5 (2.34) |

88.8 (3.50) |

94.1 (3.70) |

101.0 (3.98) |

819.5 (32.26) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 12.5 | 10.6 | 9.4 | 9.7 | 9.6 | 7.6 | 7.1 | 7.2 | 7.8 | 11.8 | 13.0 | 13.5 | 119.7 |

| Average snowy days | 1.3 | 2.0 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 4.7 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 72 | 102 | 147 | 182 | 203 | 213 | 229 | 232 | 198 | 122 | 91 | 77 | 1,873 |

| Source: Meteo France[105][106] Infoclimat [107] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Nantes-Bouguenais (Nantes Atlantique Airport), elevation: 27 m or 89 ft, 1961–1990 normals and extremes | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 17.6 (63.7) |

19.5 (67.1) |

23.2 (73.8) |

27.4 (81.3) |

30.3 (86.5) |

36.7 (98.1) |

36.3 (97.3) |

37.4 (99.3) |

34.3 (93.7) |

27.0 (80.6) |

20.9 (69.6) |

18.2 (64.8) |

37.4 (99.3) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 11.3 (52.3) |

13.8 (56.8) |

15.4 (59.7) |

17.7 (63.9) |

23.5 (74.3) |

28.6 (83.5) |

28.5 (83.3) |

28.0 (82.4) |

24.6 (76.3) |

20.7 (69.3) |

14.6 (58.3) |

11.6 (52.9) |

28.6 (83.5) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 9.2 (48.6) |

9.8 (49.6) |

12.4 (54.3) |

14.8 (58.6) |

17.9 (64.2) |

21.6 (70.9) |

24.1 (75.4) |

23.8 (74.8) |

21.8 (71.2) |

17.0 (62.6) |

12.1 (53.8) |

9.5 (49.1) |

16.2 (61.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6.0 (42.8) |

6.5 (43.7) |

8.2 (46.8) |

10.3 (50.5) |

13.5 (56.3) |

16.8 (62.2) |

18.9 (66.0) |

18.5 (65.3) |

16.9 (62.4) |

13.3 (55.9) |

8.5 (47.3) |

6.3 (43.3) |

12.0 (53.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 2.9 (37.2) |

3.2 (37.8) |

4.2 (39.6) |

5.8 (42.4) |

8.8 (47.8) |

11.8 (53.2) |

13.6 (56.5) |

13.3 (55.9) |

12.1 (53.8) |

9.1 (48.4) |

5.1 (41.2) |

3.4 (38.1) |

7.8 (46.0) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | −3.6 (25.5) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

1.2 (34.2) |

4.0 (39.2) |

7.4 (45.3) |

9.4 (48.9) |

11.5 (52.7) |

11.8 (53.2) |

9.4 (48.9) |

5.1 (41.2) |

2.7 (36.9) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −13.0 (8.6) |

−12.3 (9.9) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

3.8 (38.8) |

6.1 (43.0) |

5.8 (42.4) |

2.9 (37.2) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

−5.9 (21.4) |

−10.2 (13.6) |

−13.0 (8.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 90.7 (3.57) |

59.9 (2.36) |

73.6 (2.90) |

44.7 (1.76) |

60.7 (2.39) |

37.8 (1.49) |

39.1 (1.54) |

35.5 (1.40) |

65.1 (2.56) |

66.0 (2.60) |

84.4 (3.32) |

77.0 (3.03) |

734.5 (28.92) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 13.0 | 11.0 | 11.5 | 9.5 | 10.5 | 7.5 | 6.5 | 6.0 | 8.0 | 10.5 | 10.5 | 11.5 | 116 |

| Average snowy days | 1.0 | trace | trace | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | trace | 1.0 | 2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 88 | 84 | 80 | 77 | 78 | 76 | 75 | 76 | 80 | 86 | 88 | 89 | 81 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 72.2 | 99.3 | 148.4 | 187.0 | 211.3 | 239.5 | 266.8 | 238.9 | 191.3 | 140.5 | 91.2 | 69.9 | 1,956.3 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 27.0 | 35.0 | 41.0 | 46.0 | 46.0 | 51.0 | 56.0 | 55.0 | 51.0 | 42.0 | 33.0 | 27.0 | 42.5 |

| Source 1: NOAA[108] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Infoclimat.fr (humidity)[109] | |||||||||||||

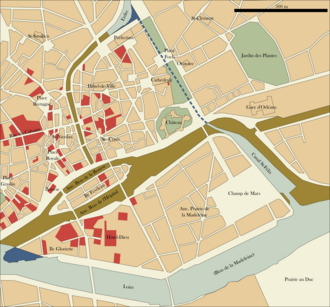

Urban layout

Nantes's layout is typical of French towns and cities. It has a historical centre with old monuments, administrative buildings and small shops, surrounded by 19th-century faubourgs surrounded by newer suburban houses and public housing. The city centre has a medieval core (corresponding to the former walled town) and 18th-century extensions running west and east. The northern extension, Marchix, was considered squalid and nearly disappeared during the 20th century. The old town did not extend south before the 19th century, since it would have meant building on the unsteady islands in the Loire.[110]

The medieval core has narrow streets and a mixture of half-timbered buildings, more recent sandstone buildings, post-World War II reconstruction and modern redevelopment. It is primarily a student neighbourhood, with many bars and small shops. The eastern extension (behind Nantes Cathedral) was traditionally inhabited by the aristocracy, and the larger western extension along the Loire was built for the bourgeoisie. It is Nantes's most-expensive area, with wide avenues, squares and hôtels particuliers.[111] The area was extended towards the Parc de Procé during the 19th century. The other faubourgs were built along the main boulevards and the plateaus, turning the valleys into parks.[112] Outside central Nantes several villages, including Chantenay, Doulon, L'Eraudière and Saint-Joseph-de-Porterie, were absorbed by urbanisation.[113]

After World War II, several housing projects were built to accommodate Nantes's growing population. The oldest, Les Dervallières, was developed in 1956 and was followed by Bellevue in 1959 and Le Breil and Malakoff in 1971.[113] Once areas of poverty, they are experiencing regeneration since the 2000s.[114] The northern outskirts of the city, along the Erdre, include the main campus of the University of Nantes and other institutes of higher education. During the second half of the 20th century, Nantes expanded south into the communes of Rezé, Vertou and Saint-Sébastien-sur-Loire (across the Loire but near the city centre) and north-bank communes including Saint-Herblain, Orvault and Sainte-Luce-sur-Loire.[113]

The 4.6-square-kilometre (1.8 sq mi) Isle of Nantes is divided between former shipyards on the west, an old faubourg in its centre and modern housing estates on the east. Since the 2000s, it has been subject to the conversion of former industrial areas into office space, housing and leisure facilities. Local authorities intend to make it an extension of the city centre. Further development is also planned on the north bank along an axis linking the train station and the Loire.[110]

Parks and environment

Nantes has 100 public parks, gardens and squares covering 218 hectares (540 acres).[115] The oldest is the Jardin des Plantes, a botanical garden created in 1807. It has a large collection of exotic plants, including a 200-year-old Magnolia grandiflora and the national collection of camellia.[116] Other large parks include the Parc de Procé, Parc du Grand Blottereau and Parc de la Gaudinière, the former gardens of country houses built outside the old town. Natural areas, an additional 180 hectares (440 acres), include the Petite Amazonie (a Natura 2000 protected forest) and several woods, meadows and marshes. Green space (public and private) makes up 41 percent of Nantes's area.[115]

The city adopted an ecological framework in 2007 to reduce greenhouse gases and promote energy transition.[117] Nantes has three ecodistricts (one on the Isle of Nantes, one near the train station and the third in the north-east of the city), which aim to provide affordable, ecological housing and counter urban sprawl by redeveloping neglected areas of the city.[118]

Governance

Local government

Nantes is the préfecture (capital city) of the Loire-Atlantique département and the Pays de la Loire région. It is the residence of a région and département prefect, local representatives of the French government. Nantes is also the meeting place of the région and département councils, two elected political bodies.

The city is administered by a mayor and a council, elected every six years. The council has 65 councillors.[119] It originated in 1410, when John V, Duke of Brittany created the Burghers's Council. The assembly was controlled by wealthy merchants and the Lord Lieutenant. After the union of Brittany and France, the burghers petitioned the French king to give them a city council which would enhance their freedom; their request was granted by Francis II in 1559. The new council had a mayor, ten aldermen and a crown prosecutor. The first council was elected in 1565 with Nantes's first mayor, Geoffroy Drouet.[120] The present city council is a result of the French Revolution and a 4 December 1789 act. The current mayor of Nantes is Johanna Rolland (Socialist Party), who was elected on 4 April 2014. The party has held a majority since 1983, and Nantes has become a left-wing stronghold.[121]

Since 1995, Nantes has been divided into 11 neighbourhoods (quartiers), each with an advisory committee and administrative agents. City-council members are appointed to each quartier to consult with the local committees. The neighbourhood committees, existing primarily to facilitate dialogue between citizens and the local government, meet twice a year.[122]

Like most French municipalities, Nantes is part of an intercommunal structure which combines the city with 24 smaller, neighbouring communes. Called Nantes Métropole, it encompasses the city's metropolitan area and had a population of 609,198 in 2013. Nantes Métropole administers urban planning, transport, public areas, waste disposal, energy, water, housing, higher education, economic development, employment and European topics.[123] As a consequence, the city council's mandates are security, primary and secondary education, early childhood, social aid, culture, sport and health.[124] Nantes Métropole, created in 1999, is administered by a council consisting of the 97 members of the local municipal councils. According to an act passed in 2014, beginning in 2020, the metropolitan council will be elected by the citizens of Nantes Métropole. The council is currently overseen by Rolland.[125]

Heraldry

Local authorities began using official symbols in the 14th century, when the provost commissioned a seal on which the Duke of Brittany stood on a boat and protected Nantes with his sword. The present coat of arms was first used in 1514; its ermines symbolise Brittany, and its green waves suggest the Loire.[126]

Nantes's coat of arms had ducal emblems before the French Revolution: the belt cord of the Order of the Cord (founded by Anne of Brittany) and the city's coronet. The coronet was replaced by a mural crown during the 18th century, and during the revolution a new emblem with a statue of Liberty replaced the coat of arms. During Napoleon's rule the coat of arms returned, with bees (a symbol of his empire) added to the chief. The original coat of arms was readopted in 1816, and the Liberation Cross and the 1939–45 War Cross were added in 1948.[126]

Before the revolution, Nantes's motto was "Oculi omnium in te sperant, Domine" ("The eyes of all wait upon thee, O Lord", a line from a grace). It disappeared during the revolution, and the city adopted its current motto—"Favet Neptunus eunti" ("Neptune favours the traveller")[126]—in 1816. Nantes's flag is derived from the naval jack flown by Breton vessels before the French Revolution. The flag has a white cross on a black one; its quarters have Breton ermines except for the upper left, which has the city's coat of arms. The black and white crosses are historic symbols of Brittany and France, respectively.[127]

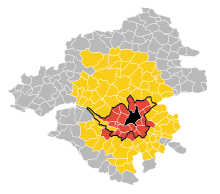

Nantes and Brittany

Nantes and the Loire-Atlantique département were part of the historic province of Brittany, and the city and Rennes were its traditional capitals. In the 1789 replacement of the historic provinces of France, Brittany was divided among five départements. The administrative region of Brittany did not exist during the 19th and early 20th centuries, although its cultural heritage remained.[128] Nantes and Rennes are in Upper Brittany (the Romance-speaking part of the region), and Lower Brittany in the west is traditionally Breton-speaking and more Celtic in culture. As a large port whose outskirts encompassed other provinces, Nantes has been Brittany's economic capital and a cultural crossroads. Breton culture in Nantes is not necessarily characteristic of Lower Brittany's, although the city experienced substantial Lower Breton immigration during the 19th century.[129][130]

In the mid-20th century, several French governments considered creating a new level of local government by combining départements into larger regions.[131] The regions, established by acts of parliament in 1955 and 1972, loosely follow the pre-revolutionary divisions and Brittany was revived as Region Brittany. Nantes and the Loire-Atlantique département were not included, because each new region centred on one metropolis.[132] Region Brittany was created around Rennes, similar in size to Nantes; the Loire-Atlantique département formed a new region with four other départements, mainly portions of the old provinces of Anjou, Maine and Poitou. The new region was called Pays de la Loire ("Loire Countries") although it does not include most of the Loire Valley. It has often been said that the separation of Nantes from the rest of Brittany was decided by Vichy France during the Second World War. Philippe Pétain created a new Brittany without Nantes in 1941, but his region disappeared after the liberation.[133][134][135]

Debate continues about Nantes's place in Brittany, with polls indicating a large majority in Loire-Atlantique and throughout the historic province favouring Breton reunification.[136] In a 2014 poll, 67 percent of Breton people and 77 percent of Loire-Atlantique residents favoured reunification.[137] Opponents, primarily Pays de la Loire officials, say that their region could not exist economically without Nantes. Pays de la Loire officials favour a union of Brittany with the Pays de la Loire, but Breton politicians oppose the incorporation of their region into a Greater West region.[138] Nantes's city council has acknowledged the fact that the city is culturally part of Brittany, but its position on reunification is similar to that of the Pays de la Loire.[139] City officials tend to consider Nantes an open metropolis with its own personality, independent of surrounding regions.[140]

Twin towns – sister cities

Cooperation agreements

Partnership agreements have been signed with cities in developing countries, including:[150]

Population

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: EHESS[151] and INSEE (1968–2020)[152] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Nantes had 320,732 inhabitants in 2020, the largest population in its history.[152] Although it was the largest city in Brittany during the Middle Ages, it was smaller than three other north-western towns: Angers, Tours and Caen.[153] Nantes has experienced consistent growth since the Middle Ages, except during the French Revolution and the reign of Napoleon I (when it experienced depopulation, primarily due to the Continental System).[154] In 1500, the city had a population of around 14,000.[153] Nantes's population increased to 25,000 in 1600 and to 80,000 in 1793.[154] In 1800 it was the sixth-largest French city, behind Paris (550,000), Lyon, Marseilles, Bordeaux and Rouen (all 80,000 to 109,000).[153] Population growth continued through the 19th century; although other European cities experienced increased growth due to industrialisation, in Nantes growth remained at its 18th-century pace.[154] Nantes reached the 100,000 mark about 1850, and 130,000 around 1900. In 1908 it annexed the neighbouring communes of Doulon and Chantenay, gaining almost 30,000 inhabitants. Population growth was slower during the 20th century, remaining under 260,000 from the 1960s to the 2000s primarily because urban growth spread to surrounding communes. Since 2000 the population of Nantes began to rise due to redevelopment,[155] and its urban area has continued to experience population growth. The Nantes metropolitan area had a population of 907,995 in 2013, nearly doubling since the 1960s. Its population is projected to reach one million by 2030, based on the fertility rate.[156]

The population of Nantes is younger than the national average, with 44.3 percent under age 29 (France 35.3 percent). People over age 60 account for 18.7 percent of the city's population (France 26.4 percent).[152] Single-person households are 53.1 percent of the total, and 16.4 percent of households are families with children.[157] Young couples with children tend to move outside the city because of high property prices, and most newcomers are students (37 percent) and adults moving for professional reasons (49 percent). Students generally come from within the region, and working people are often from Paris.[110] In 2020, the unemployment rate was 10.5 percent of the active population (France 9.5 percent, Loire-Atlantique 7.9 percent).[158] The poorest council estates had unemployment rates of 22 to 47 percent.[110] Of those employed, 59.5 percent were in intermediate or management positions, 24.1 percent were employees and 11.4 percent were workers in 2020.[158] In 2020, 39.7 percent of the population over 15 had a higher-education degree and 12.9 percent had no diploma.[159]

Ethnicity and languages

Nantes has long had ethnic minorities. Spanish, Portuguese and Italian communities were mentioned during the 16th century, and an Irish Jacobite community appeared a century later. However, immigration has always been lower in Nantes than in other large French cities. The city's foreign population has been stable since 1990, half the average for other French cities of similar size.[110] France does not have ethnic or religious categories in its census, but counts the number of people born in a foreign country. In 2013 this category had 24,949 people in Nantes, or 8.5 percent of the total population. The majority (60.8 percent) were 25 to 54 years old. Their primary countries of origin were Algeria (13.9 percent), Morocco (11.4 percent) and Tunisia (5.8 percent). Other African countries accounted for 24.9 percent, the European Union 15.6 percent, the rest of Europe 4.8 percent and Turkey 4.3 percent.[160]

The city is part of the territory of the langues d'oïl, a dialect continuum which stretches across northern France and includes standard French. The local dialect in Nantes is Gallo, spoken by some in Upper Brittany. Nantes, as a large city, has been a stronghold of standard French. A local dialect (parler nantais) is sometimes mentioned by the press, but its existence is dubious and its vocabulary mainly the result of rural emigration.[161] As a result of 19th-century Lower Breton immigration, Breton was once widely spoken in parts of Nantes.[162] Nantes signed the charter of the Public Office for the Breton Language in 2013. Since then, the city has supported its six bilingual schools and introduced bilingual signage.[163]

Economy

For centuries, Nantes's economy was linked to the Loire and the Atlantic; the city had France's largest harbour in the 18th century.[54] Food processing predominated during the Industrial Age, with sugar refineries (Beghin-Say), biscuit factories (LU and BN), canned fish (Saupiquet and Tipiak) and processed vegetables (Bonduelle and Cassegrain); these brands still dominate the French market. The Nantes region is France's largest food producer; the city has recently become a hub of innovation in food security, with laboratories and firms such as Eurofins Scientific.[164]

Nantes experienced deindustrialisation after port activity in Saint-Nazaire largely ceased, culminating in the 1987 closure of the shipyards. At that time, the city attempted to attract service firms. Nantes capitalised on its culture and proximity to the sea to present itself as creative and modern. Capgemini (management consulting), SNCF (rail) and Bouygues Telecom opened large offices in the city, followed by smaller companies.[165] Since 2000 Nantes has developed a business district, Euronantes, with 500,000 m2 (5.4 million sq ft) of office space and 10,000 jobs.[166] Although its stock exchange was merged with that of Paris in 1990,[167] Nantes is the third-largest financial centre in France after Paris and Lyon.[168]

The city has one of the best-performing economies in France, producing €55 billion annually; €29 billion returns to the local economy.[169] Nantes has over 25,000 businesses with 167,000 jobs,[170] and its metropolitan area has 42,000 firms and 328,000 jobs.[171] The city is one of France's most dynamic in job creation, with 19,000 jobs created in Nantes Métropole between 2007 and 2014 (outperforming larger cities such as Marseilles, Lyon and Nice).[171] The communes surrounding Nantes have industrial estates and retail parks, many along the region's ring road. The metropolitan area has ten large shopping centres; the largest, Atlantis in Saint-Herblain, is a mall with 116 shops and several superstores (including IKEA).[172] The shopping centres threaten independent shops in central Nantes, but it remains the region's largest retail area [173] with about 2,000 shops.[174] Tourism is a growing sector and Nantes, with two million visitors annually, is France's seventh-most-visited city.[175]

In 2021, 79.8 percent of the city's businesses were involved in trade, transport and services; 12.2 percent in public administration, education and health; 4.4 percent in construction, and 3.6 percent in industry.[176] Although industry is less significant than it was before the 1970s, Nantes is France's second-largest centre for aeronautics.[177] The European company Airbus produces its fleet's wingboxes and radomes in Nantes, employing about 2,000 people.[178] The city's remaining port terminal still handles wood, sugar, fertiliser, metals, sand and cereals, ten percent of the total Nantes–Saint-Nazaire harbour traffic (along the Loire estuary).[179] The Atlanpole technopole, in northern Nantes on its border with Carquefou, intends to develop technological and science sectors throughout the Pays de la Loire. With a business incubator, it has 422 companies and 71 research and higher-education facilities and specialises in biopharmaceuticals, information technology, renewable energy, mechanics, food production and naval engineering.[180] Creative industries in Nantes had over 9,000 architectural, design, fashion, media, visual-arts and digital-technology companies in 2016, a 15 percent job-creation rate between 2007 and 2012 and have a hub under construction on the Isle of Nantes.[181]

Architecture

Nantes's cityscape is primarily recent, with more buildings built during the 20th century than in any other era.[182] The city has 127 buildings listed as monuments historiques, the 19th-ranked French city.[183] Most of the old buildings were made of tuffeau stone (a light, easily sculpted sandstone typical of the Loire Valley) and cheaper schist. Because of its sturdiness, granite was often used for foundations. Old buildings on the former Feydeau Island and the neighbouring embankments often lean because they were built on damp soil.[184]

Nantes has a few structures dating to antiquity and the early Middle Ages. Remnants of the third-century Roman city wall exist in the old town.[185] The Saint-Étienne chapel, in the Saint-Donatien cemetery outside the city centre, dates to 510 and was originally part of a Roman necropolis.[186] The Roman city walls were largely replaced during the 13th and 15th centuries. Although many of the walls were destroyed in the 18th century, some segments (such as Porte Saint-Pierre, built in 1478) survived.[187]

Several 15th- and 16th-century half-timbered houses still stand in Le Bouffay, an ancient area corresponding to Nantes's medieval core[188] which is bordered by Nantes Cathedral and the Castle of the Dukes of Brittany. The large, Gothic cathedral replaced an earlier Romanesque church. Its construction took 457 years, from 1434 to 1891. The cathedral's tomb of Francis II, Duke of Brittany and his wife is an example of French Renaissance sculpture.[189] The Psallette, built next to the cathedral about 1500, is a late-Gothic mansion.[187] The Gothic castle is one of Nantes's chief landmarks. Begun in 1207, many of its current buildings date to the 15th century. Although the castle had a military role, it was also a residence for the ducal court. Granite towers on the outside hide delicate tuffeau-stone ornaments on its inner facades, designed in Flamboyant style with Italianate influence.[190] The Counter-Reformation inspired two baroque churches: the 1655 Oratory Chapel and Sainte-Croix Church, rebuilt in 1670. A municipal belfry clock (originally on a tower of Bouffay Castle, a prison demolished after the French Revolution) was added to the church in 1860. [191]

After the Renaissance, Nantes developed west of its medieval core along new embankments. Trade-derived wealth permitted the construction of many public monuments during the 18th century, most designed by the neoclassical architects Jean-Baptiste Ceineray and Mathurin Crucy. They include the Chamber of Accounts of Brittany (now the préfecture, 1763–1783); the Graslin Theatre (1788); Place Foch, with its column and statue of Louis XVI (1790), and the stock exchange (1790–1815). Place Royale was completed in 1790, and the large fountain added in 1865. Its statues represent the city of Nantes, the Loire and its main tributaries. The city's 18th-century heritage is also reflected in the hôtels particuliers and other private buildings for the wealthy, such as the Cours Cambronne (inspired by Georgian terraces).[192] Although many of the 18th-century buildings have a neoclassical design, they are adorned with sculpted rococo faces and balconies. This architecture has been called "Nantais baroque".[193]

Most of Nantes's churches were rebuilt during the 19th century, a period of population growth and religious revival after the French Revolution. Most were rebuilt in Gothic Revival style, including the city's two basilicas: Saint-Nicolas and Saint-Donatien. The first, built between 1844 and 1869, was one of France's first Gothic Revival projects. The latter was built between 1881 and 1901, after the Franco-Prussian War (which triggered another Catholic revival in France). Notre-Dame-de-Bon-Port, near the Loire, is an example of 19th-century neoclassicism. Built in 1852, its dome was inspired by that of Les Invalides in Paris.[194] The Passage Pommeraye, built in 1840–1843, is a multi-storey shopping arcade typical of the mid-19th century.[195]

Industrial architecture includes several factories converted into leisure and business space, primarily on the Isle of Nantes. The former Lefèvre-Utile factory is known for its Tour Lu, a publicity tower built in 1909. Two cranes in the former harbour, dating to the 1950s and 1960s, have also become landmarks. Recent architecture is dominated by postwar concrete reconstructions, modernist buildings and examples of contemporary architecture such as the courts of justice, designed by Jean Nouvel in 2000.[196][197]

Culture

Museums

Nantes has several museums. The Fine Art Museum is the city's largest. Opened in 1900, it has an extensive collection ranging from Italian Renaissance paintings to contemporary sculpture. The museum includes works by Tintoretto, Brueghel, Rubens, Georges de La Tour, Ingres, Monet, Picasso, Kandinsky and Anish Kapoor.[198] The Historical Museum of Nantes, in the castle, is dedicated to local history and houses the municipal collections. Items include paintings, sculptures, photographs, maps and furniture displayed to illustrate major points of Nantes history such as the Atlantic slave trade, industrialisation and the Second World War.[199]

The Dobrée Museum, closed for repairs as of 2017[update], houses the département's archaeological and decorative-arts collections. The building is a Romanesque Revival mansion facing a 15th-century manor. Collections include a golden reliquary made for Anne of Brittany's heart, medieval statues and timber frames, coins, weapons, jewellery, manuscripts and archaeological finds.[200] The Natural History Museum of Nantes is one of the largest of its kind in France. It has more than 1.6 million zoological specimens and several thousand mineral samples.[201] The Machines of the Isle of Nantes, opened in 2007 in the converted shipyards, has automatons, prototypes inspired by deep-sea creatures and a 12-metre-tall (39 ft) walking elephant. With 620,000 visitors in 2015, the Machines were the most-visited non-free site in Loire-Atlantique.[202] Smaller museums include the Jules Verne Museum (dedicated to the author, who was born in Nantes) and the Planetarium. The HAB Galerie, located in a former banana warehouse on the Loire, is Nantes's largest art gallery. Owned by the city council, it is used for contemporary-art exhibitions.[203] The council manages four other exhibition spaces, and the city has several private galleries.[204]

Venues

Le Zénith Nantes Métropole, an indoor arena in Saint-Herblain, has a capacity of 9,000 and is France's largest concert venue outside Paris.[205] Since its opening in 2006, Placebo, Supertramp, Snoop Dogg and Bob Dylan have performed on its stage. Nantes's largest venue is La Cité, Nantes Events Center, a 2,000-seat auditorium.[206] It hosts concerts, congresses and exhibitions, and is the primary venue of the Pays de la Loire National Orchestra. The Graslin Theatre, built in 1788, is home to the Angers-Nantes Opéra. The former LU biscuit factory, facing the castle, has been converted into Le Lieu unique. It includes a Turkish bath, restaurant and bookshop and hosts art exhibits, drama, music and dance performances.[207] The 879-seat Grand T is the Loire-Atlantique département theatre,[208] and the Salle Vasse is managed by the city. Other theatres include the Théâtre universitaire and several private venues. La Fabrique, a cultural entity managed by the city, has three sites which include music studios and concert venues. The largest is Stereolux, specialising in rock concerts, experimental happenings and other contemporary performances. The 140-seat Pannonica specialises in jazz, and the nearby 503-seat Salle Paul-Fort is dedicated to contemporary French singers.[209][210] Nantes has five cinemas, with others throughout the metropolitan area.[211]

Events and festivals

The Royal de Luxe street theatre company moved to Nantes in 1989, and has produced a number of shows in the city. The company is noted for its large marionettes (including a giraffe, the Little Giant and the Sultan's Elephant), and has also performed in Lisbon, Berlin, London and Santiago.[212] Former Royal de Luxe machine designer François Delarozière created the Machines of the Isle of Nantes and its large walking elephant in 2007. The Machines sponsor theatre, dance, concerts, ice-sculpting shows and performances for children in the spring and fall and at Christmastime.[213]

Estuaire contemporary-art exhibitions were held along the Loire estuary in 2007, 2009 and 2012.[214] They left several permanent works of art in Nantes and inspired the Voyage à Nantes, a series of contemporary-art exhibitions across the city which has been held every summer since 2012. A route (a green line painted on the pavement) helps visitors make the voyage between the exhibitions and the city's major landmarks. Some works of art are permanent, and others are used for a summer.[215] Permanent sculptures include Daniel Buren's Anneaux (a series of 18 rings along the Loire reminiscent of Atlantic slave trade shackles) and works by François Morellet and Dan Graham.[216]

La Folle Journée (The Mad Day, an alternate title of Pierre Beaumarchais' play The Marriage of Figaro) is a classical music festival held each winter. The original one-day festival now lasts for five days. Its programme has a main theme (past themes have included exile, nature, Russia and Frédéric Chopin), mixing classics with lesser-known and -performed works. The concept has been exported to Bilbao, Tokyo and Warsaw, and the festival sold a record 154,000 tickets in 2015.[217] The September Rendez-vous de l'Erdre couples a jazz festival with a pleasure-boating show on the Erdre,[218] exposing the public to a musical genre considered elitist; all concerts are free. Annual attendance is about 150,000.[219] The Three Continents Festival is an annual film festival dedicated to Asia, Africa and South America, with a Mongolfière d'or (Golden Hot-air Balloon) awarded to the best film. Nantes also hosts Univerciné (festivals dedicated to films in English, Italian, Russian and German) and a smaller Spanish film festival. The Scopitone festival is dedicated to digital art, and Utopiales is an international science fiction festival.[220]

Slavery Memorial

A path along the Loire river banks, between the Anne-de-Bretagne Bridge and the Victor-Schoelcher footbridge begins the Nantes slavery memorial. The path is covered in 2,000 spaced glass inserts, with 1,710 of them commemorating the names of slave ships and their port dates in Nantes. The other 290 inserts name ports in Africa, the Americas, and the area around the Indian Ocean. The path and surrounding 1.73-acre park lead to the under-the-docks part of the memorial which opens with a staircase, leading visitors underground closer to the water level of the river, which can be seen through the gaps between the support pillars. Upon entry, visitors are greeted with The Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the word "freedom" written in 47 different languages from areas affected by the slave trade. Other etchings of quotes by figures like Nelson Mandela and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. appear on the slanted frosted glass wall which lined the memorial wall opposite the pillars which open to the river. These quotes come from across the globe, from all four continents affected by the slave trade, and span over five centuries, from the 17th to the 21st. At the end of the hall, toward the exit, is a room with the timeline of slavery as it became abolished in various countries around the world.[221]

In the arts

Nantes has been described as the birthplace of surrealism, since André Breton (leader of the movement) met Jacques Vaché there in 1916.[222] In Nadja (1928), André Breton called Nantes "perhaps with Paris the only city in France where I have the impression that something worthwhile may happen to me".[223] Fellow surrealist Julien Gracq wrote The Shape of a City, published in 1985, about the city. Nantes also inspired Stendhal (in his 1838 Mémoires d'un touriste); Gustave Flaubert (in his 1881 Par les champs et par les grèves, where he describes his journey through Brittany); Henry James, in his 1884 A Little Tour in France; André Pieyre de Mandiargues in Le Musée noir (1946), and Paul-Louis Rossi in Nantes (1987).[224]

The city is the hometown of French New Wave film director Jacques Demy. Two of Demy's films were set and shot in Nantes: Lola (1964) and A Room in Town (1982). The Passage Pommeraye appears briefly in The Umbrellas of Cherbourg. Other films set (or filmed) in Nantes include God's Thunder by Denys de La Patellière (1965), The Married Couple of the Year Two by Jean-Paul Rappeneau (1971), Day Off by Pascal Thomas (2001) and Black Venus by Abdellatif Kechiche (2010). Jean-Luc Godard's Keep Your Right Up was filmed at its airport in 1987.[211]

Nantes appears in a number of songs, the best-known to non-French audiences being 2007's "Nantes" by the American band Beirut. French-language songs include "Nantes" by Barbara (1964) and "Nantes" by Renan Luce (2009). The city is mentioned in about 50 folk songs, making it the most-sung-about city in France after Paris. "Dans les prisons de Nantes" is the most popular, with versions recorded by Édith Piaf, Georges Brassens, Tri Yann and Nolwenn Leroy. Other popular folk songs include "Le pont de Nantes" (recorded by Guy Béart in 1967 and Nana Mouskouri in 1978), "Jean-François de Nantes" (a sea shanty) and the bawdy "De Nantes à Montaigu".[225]

British painter J. M. W. Turner visited Nantes in 1826 as part of a journey in the Loire Valley, and later painted a watercolour view of Nantes from Feydeau Island. The painting was bought by the city in 1994, and is on exhibit at the Historical Museum in the castle.[226] An engraving of this work was published in The Keepsake annual for 1831, with an illustrative poem entitled ![]() The Return. by Letitia Elizabeth Landon. Turner also made two sketches of the city, which are in collections at Tate Britain.[227]

The Return. by Letitia Elizabeth Landon. Turner also made two sketches of the city, which are in collections at Tate Britain.[227]

Cuisine

During the 19th century Nantes-born gastronome Charles Monselet praised the "special character" of the local "plebeian" cuisine, which included buckwheat crepes, caillebotte fermented milk and fouace brioche.[228] The Nantes region is renowned in France for market gardens and is a major producer of corn salad, leeks, radishes and carrots.[229] Nantes has a wine-growing region, the Vignoble nantais, primarily south of the Loire. It is the largest producer of dry white wines in France, chiefly Muscadet and Gros Plant (usually served with fish, langoustines and oysters).[230]

Local fishing ports such as La Turballe and Le Croisic mainly offer shrimp and sardines, and eels, lampreys, zander and northern pike are caught in the Loire.[228] Local vegetables and fish are widely available in the city's eighteen markets, including the Talensac covered market (Nantes's largest and best known). Although local restaurants tend to serve simple dishes made with fresh local products, exotic trends have influenced many chefs in recent years.[228]

Beurre blanc is Nantes's most-famous local specialty. Made with Muscadet, it was invented around 1900 in Saint-Julien-de-Concelles (on the south bank of the Loire) and has become a popular accompaniment for fish.[228] Other specialties are the LU and BN biscuits, including the Petit-Beurre (produced since 1886), berlingot (sweets made with flavoured melted sugar) and similar rigolette sweets with marmalade filling, gâteau nantais (a rum cake invented in 1820), Curé nantais and Mâchecoulais cheeses and fouace, a star-shaped brioche served with new wine in autumn.[229]

Education

The University of Nantes was first founded in 1460 by Francis II, Duke of Brittany, but it failed to become a large institution during the Ancien Régime. It disappeared in 1793 with the abolition of French universities. During the 19th century, when many of the former universities reopened, Nantes was neglected and local students had to go to Rennes and Angers. In 1961 the university was finally recreated, but Nantes has not established itself as a large university city.[231] The university had about 30,000 students during the 2013–2014 academic year, and the metropolitan area had a total student population of 53,000. This was lower than in nearby Rennes (64,000), and Nantes is the ninth-largest commune in France in its percentage of students.[232] The university is part of the EPSCP Bretagne-Loire Université, which joins seven universities in western France to improve the region's academic and research potential.[citation needed]

In addition to the university, Nantes has a number of colleges and other institutes of higher education. Audencia, a private management school, is ranked as one of the world's best by the Financial Times and The Economist.[233][234] The city has five engineering schools: Oniris (veterinary medicine and food safety), École centrale de Nantes (mechanical and civil engineering), Polytech Nantes (digital technology and civil engineering), École des mines de Nantes (now IMT Atlantique) (information technology, nuclear technology, safety and energy) and ICAM (research and logistics). Nantes has three other grandes écoles: the École supérieure du bois (forestry and wood processing), the School of Design and Exi-Cesi (computing). Other institutes of higher education include a national merchant navy school, a fine-arts school, a national architectural school and Epitech and Supinfo (computing).[235]

Sport

Nantes has several large sports facilities. The largest is the Stade de la Beaujoire, built for UEFA Euro 1984. The stadium, which also hosted matches during the 1998 FIFA World Cup and the 2007 Rugby World Cup, has 37,473 seats. The second-largest venue is the Hall XXL, an exhibition hall on the Stade de la Beaujoire grounds. The 10,700-seat stadium was selected as a venue for the 2017 World Men's Handball Championship. Smaller facilities include the 4,700-seat indoor Palais des Sports, a venue for EuroBasket 1983. The nearby Mangin Beaulieu sports complex has 2,500 seats and Pierre Quinon Stadium, an athletics stadium within the University of Nantes, has 790 seats. La Trocardière, an indoor 4,238-seat stadium, is in Rezé.[236] The Erdre has a marina and a centre for rowing, sailing and canoeing, and the city has six swimming pools.[237]

Six teams in Nantes play at a high national or international level. Best known is FC Nantes, which is a member of Ligue 1 for the 2018–19 season. Since its formation in 1943, the club has won eight Championnat titles and three Coupes de France. FC Nantes has several French professional football records, including the most consecutive seasons in the elite division (44), most wins in a season (26), consecutive wins (32) and consecutive home wins (92 games, nearly five years). In handball, volleyball and basketball, Nantes's men's and women's clubs play in the French first division: HBC Nantes and Nantes Loire Atlantique Handball (handball), Nantes Rezé Métropole Volley and Volley-Ball Nantes (volleyball) and Hermine de Nantes Atlantique and Nantes Rezé Basket (basketball). The men's Nantes Erdre Futsal futsal team plays in the Championnat de France de Futsal, and the main athletics team (Nantes Métropole Athlétisme) includes some of France's best athletes.[238]

Transport

The city is linked to Paris by the A11 motorway, which passes through Angers, Le Mans and Chartres. Nantes is on the Way of the Estuaries, a network of motorways connecting northern France and the Spanish border in the south-west while bypassing Paris. The network serves Rouen, Le Havre, Rennes, La Rochelle and Bordeaux. South of Nantes, the road corresponds to the A83 motorway; north of the city (towards Rennes) it is the RN137, a free highway. These motorways form a 43-kilometre (27 mi) ring road around the city, France's second longest after the ring in Bordeaux.[239]

Nantes's central railway station is connected by TGV trains to Paris, Lille, Lyon, Marseille and Strasbourg. The LGV Atlantique high-speed railway reaches Paris in two hours, ten minutes (compared with four hours by car). With almost 12 million passengers each year, the Nantes station is the sixth-busiest in France outside Paris.[240] In addition to TGV trains, the city is connected by Intercités trains to Rennes, Vannes, Quimper, Tours, Orléans, La Rochelle and Bordeaux.[241] Local TER trains serve Pornic, Cholet or Saint-Gilles-Croix-de-Vie.[242]

Nantes Atlantique Airport in Bouguenais, 8 kilometres (5 miles) south-west of the city centre, serves about 80 destinations in Europe (primarily in France, Spain, Italy, the United Kingdom and Greece) and connects airports in Africa, the Caribbean and Canada.[243] Air traffic has increased from 2.6 million passengers in 2009 to 4.1 million in 2014, while its capacity has been estimated at 3.5 million passengers per year.[244] A new Aéroport du Grand Ouest in Notre-Dame-des-Landes, 20 kilometres (12 miles) north of Nantes, was projected from the 1970s, to create a hub serving north-western France. Its construction was however strongly opposed, primarily by green and anti-capitalist activists. The potential construction site was long occupied and the project became a political topic on the national scale. The French government eventually decided to renounce to the project in 2018.[245][246][247]

Public transport in Nantes is managed by Semitan, also known as "Tan". One of the world's first horsebus transit systems was developed in the city in 1826. Nantes built its first compressed-air tram network in 1879, which was electrified in 1911. Like most European tram networks, Nantes's disappeared during the 1950s in the wake of automobiles and buses. However, in 1985 Nantes was the first city in France to reintroduce trams.[248] The city has an extensive public-transport network consisting of trams, buses and river shuttles. The Nantes tramway has three lines and a total of 43.5 kilometres (27 miles) of track. Semitan counted 132.6 million trips in 2015, of which 72.3 million were by tram.[249] Navibus, the river shuttle, has two lines: one on the Erdre and the other on the Loire. The latter has 520,000 passengers annually and succeeds the Roquio service, which operated on the Loire from 1887 to the 1970s.[250]

Nantes has also developed a tram-train system, the Nantes tram-train, which would allow suburban trains to run on tram lines; the system already exists in Mulhouse (in eastern France) and Karlsruhe, Germany. The city has two tram-train lines: Nantes-Clisson (southern) and Nantes-Châteaubriant (northern). Neither is yet connected to the existing tram network, and resemble small suburban trains more than tram-trains. The Bicloo bicycle-sharing system has 880 bicycles at 103 stations.[251]

Nantes Public Transportation statistics

The average amount of time people spend commuting with public transit in Nantes and Saint-Nazaire, for example to and from work, on a weekday is 40 minutes. 7.1% of public transit riders, ride for more than 2 hours every day. The average amount of time people wait at a stop or station for public transit is 12 minutes, while 16.8% of riders wait for over 20 minutes on average every day. The average distance people usually ride in a single trip with public transit is 5 km, while 2% travel for over 12 km in a single direction.[252]

Media

The local press is dominated by the Ouest-France group, which owns the area's two major newspapers: Ouest-France and Presse-Océan. Ouest-France, based in Rennes, covers north-western France and is the country's best-selling newspaper. Presse-Océan, based in Nantes, covers Loire-Atlantique. The Ouest-France group is also a shareholder of the French edition of 20 Minutes, one of two free newspapers distributed in the city. The other free paper is Direct Matin, which has no local edition. The news agency Médias Côte Ouest publishes Wik and Kostar, two free magazines dedicated to local cultural life. Nantes has a satirical weekly newspaper, La Lettre à Lulu, and several specialised magazines. Places publiques is dedicated to urbanism in Nantes and Saint-Nazaire; Brief focuses on public communication; Le Journal des Entreprises targets managers; Nouvel Ouest is for decision-makers in western France, and Idîle provides information on the local creative industry. Nantes is home to Millénaire Presse—the largest French publishing house dedicated to professional entertainers—which publishes several magazines, including La Scène.[253] The city publishes a free monthly magazine, Nantes Passion, and five other free magazines for specific areas: Couleur locale (Les Dervallières), Écrit de Bellevue, Malakocktail (Malakoff), Mosaïques (Nantes-Nord) and Zest for the eastern neighbourhoods.[254]

National radio stations FIP and Fun Radio have outlets in Nantes. Virgin Radio has a local outlet in nearby Basse-Goulaine, and Chérie FM and NRJ have outlets in Rezé. Nantes is home to France Bleu Loire-Océan, the local station of the Radio France public network, and several private local stations: Alternantes, dedicated to cultural diversity and tolerance; Euradionantes, a local- and European-news station; Fidélité, a Christian station; Hit West and SUN Radio, two music stations; Prun, dedicated to students, and Radio Atlantis (focused on the local economy).[255]

Nantes is the headquarters of France 3 Pays de la Loire, one of 24 local stations of the France Télévisions national public broadcaster. France 3 Pays de la Loire provides local news and programming for the region.[256] The city is also home to Télénantes, a local, private television channel founded in 2004. Primarily a news channel, it is available in Loire-Atlantique and parts of neighbouring Vendée and Maine-et-Loire.[257]

Notable residents

- Arthur I, Duke of Brittany (1187–probably 1203), was born in Nantes

- Duchess Anne of Brittany (1477–1514), twice queen consort, was born in Nantes

- Jacques Cassard (1679–1740), General

- Joseph Fouché (1763–1820), statesman, was educated there

- Pierre Cambronne (1770–1842), naval officer

- Floresca Guépin (1813–1889), feminist, teacher, school founder

- Jules Verne (1828–1905), science fiction writer

- Jules Vallès (1832–1885), journalist and activist