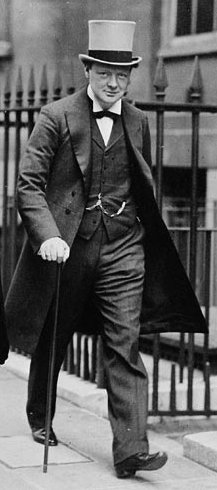

Winston Churchill

The Rt Hon Sir Winston Churchill | |

|---|---|

| |

| Prime Minister of the United Kingdom | |

| In office 26 October 1951 – 7 April 1955 | |

| Monarchs | George VI Elizabeth II |

| Deputy | Anthony Eden |

| Preceded by | Clement Attlee |

| Succeeded by | Sir Anthony Eden |

| In office 10 May 1940 – 27 July 1945 | |

| Monarch | George VI |

| Deputy | Clement Attlee |

| Preceded by | Neville Chamberlain |

| Succeeded by | Clement Attlee |

| Chancellor of the Exchequer | |

| In office 6 November 1924 – 4 June 1929 | |

| Prime Minister | Stanley Baldwin |

| Preceded by | Philip Snowden |

| Succeeded by | Philip Snowden |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 30 November 1874 Blenheim Palace, Woodstock, Oxfordshire, England |

| Died | 24 January 1965 (aged 90) Hyde Park Gate, London, England |

| Political party | Conservative Liberal |

| Spouse | Clementine Churchill |

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, KG, OM, CH, TD, FRS, PC (Can), Legion of Honor, (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 and again from 1951 to 1955. A noted statesman, orator and strategist, Churchill was also an officer in the British Army. He has been studied to a unique extent as part of modern British and world history. A prolific author, he won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1953 for his own historical writings.[1]

During his army career Churchill saw combat with the Malakand Field Force on the Northwest Frontier, at the Battle of Omdurman in the Sudan and during the Second Boer War in South Africa. During this period he also gained fame, and not a small amount of notoriety, as a correspondent. At the forefront of the political scene for almost sixty years, Churchill held numerous political and cabinet positions. Before the First World War, he served as President of the Board of Trade and Home Secretary during the Liberal governments. In the First World War Churchill served in numerous positions, as First Lord of the Admiralty, Minister of Munitions, Secretary of State for War and Secretary of State for Air. He also served in the British Army on the Western Front and commanded the 6th Battalion of the Royal Scots Fusiliers. During the interwar years, he served as Chancellor of the Exchequer.

After the outbreak of the Second World War, Churchill was appointed First Lord of the Admiralty. Following the resignation of Neville Chamberlain in May 1940, he became Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and led the British war effort against the Axis powers. His speeches were a great inspiration to the embattled Allied forces. After losing the 1945 election, Churchill became the leader of the opposition. In 1951, Churchill again became Prime Minister before finally retiring in 1955. Upon his death, he was granted the honour of a state funeral which saw one of the largest assemblies of politicians in the world.

Early life

A descendant of a famous aristocratic family, Churchill's birth surname was Spencer-Churchill. His family was the senior branch of the Spencer family, which added the surname Churchill to its own in the late 18th century. They did this to highlight their descent from John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough who won the Battle of Blenheim (a battle that seemed world decisive for the next couple of centuries); fought to deny Philippe, Duc d'Anjou his inheritance of the Spanish Succession which ultimately failed. Sir Winston descended from the first member of the Churchill family to achieve public prominence.[2]

Winston's father, Lord Randolph Churchill, the third son of the 7th Duke of Marlborough was also a politician; Winston's mother, Lady Randolph Churchill (née Jennie Jerome), the daughter of American millionaire Leonard Jerome, was of mostly Colonial American, ultimately English, descent. Churchill was born two months premature in a bedroom in Blenheim Palace in Woodstock, Oxfordshire on 30 November 1874.[2] He arrived eight months after his parents' hasty marriage.[3] He had one brother, John Strange Spencer-Churchill.

Churchill had an independent and rebellious nature and generally did poorly in school, for which he was punished. He entered Harrow School on 17 April 1888, where his military career began—within weeks of his arrival, he had joined the Harrow Rifle Corps.[4] Churchill earned high marks in English and history; he was also the school's fencing champion. He was rarely visited by his mother (then known as Lady Randolph), but wrote letters begging her to either come to the school or to allow him to come home. Churchill also had a very distant relationship with his father and Churchill once remarked how they barely talked to each other.[2] Due to his lack of parental contact Churchill became very close to his nanny, Elizabeth Anne Everest, whom he used to call "Woomany".[5][6]

Speech impediment

Churchill described himself as having a "speech impediment," which he consistently worked to overcome; after many years, he finally stated, "My impediment is no hindrance". Although the Stuttering Foundation has claimed that Churchill stuttered, the Churchill Centre has concluded that he lisped.[7] Churchill's impediment may also have been cluttering, which would fit more with his lack of attention to unimportant details and his very secure ego. Weiss suggests that Churchill may have "excelled because of, rather than in spite of his cluttering".[8]

Service in the Army

Sandhurst

After Churchill left Harrow in 1893, he applied to attend the Royal Military College, Sandhurst. However it took three attempts before Churchill passed the admittance exam.[2] Once there, Churchill did well and he graduated eighth out of a class of 150 in December 1894.[2] He was immediately commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in the 4th Queen's Own Hussars on 20 February 1895.[9] In 1941, he received the honour of Colonel of the Hussars.[9]

Churchill's official biographer Martin Gilbert noted in a 1991 interview about his book, Churchill: A Life,[10] that Churchill was accused of sodomising (or 'buggering') other students while at Sandhurst. In the book Gilbert states that Churchill immediately filed a libel case against his accuser, who was the father of a young officer snubbed by Churchill and his peers in the Hussars. According to Gilbert the father withdrew the charge and settled out of court with Churchill for a sum of £400.[11]

War correspondent

Churchill's pay as a second lieutenant in the 4th Hussars was £300. However Churchill believed that he needed at least £500 to support a style of life in keeping with other officers of the regiment. According to biographer Roy Jenkins, this is why Churchill took an interest in war correspondence.[2] When Churchill finished training he asked to be posted to areas of action in which, against all etiquette, he earned additional income as a roving war correspondent for the London newspapers.[12]

Lord Deedes explained to a gathering of the Royal Historical Society in 2001 about why Churchill went into the front line. "He was with the Grenadier Guards, who were dry [without alcohol] at battalion headquarters. They very much liked tea and condensed milk, which had no great appeal to Winston, but alcohol was permitted in the front line, in the trenches. So he suggested to the colonel that he really ought to see more of the war and get into the front line. This was highly commended by the colonel, who thought it was a very good thing to do."[13]

In 1895, Churchill travelled to Cuba to observe the Spanish fight the Cuban guerrillas; he had obtained a commission to write about the conflict from the Daily Graphic. To Churchill's delight, he came under fire for the first time on his twenty-first birthday.[9] Churchill soon received word that his nanny, Mrs Everest, was dying; he then returned to England and stayed with her for a week until she died. He wrote in his journal "She was my favourite friend." In Churchill's My Early Life he wrote "She had been my dearest and most intimate friend during the whole of the twenty years I had lived."[14] In early October 1896, he was transferred to Bombay, India. He was considered one of the best polo players in his regiment and led his team to many prestigious tournament victories.[15]

About this time he read Winwood Reade's Martyrdom of Man, a classic of Victorian atheism, which completed his loss of faith in Orthodox Christianity and left him with a sombre vision of a godless universe in which humanity was destined, nevertheless, to progress through the conflict between the more advanced and the more backward races. He passed for a time through an aggressively anti-religious phase, but this eventually gave way to a more tolerant belief in the workings of some kind of divine providence.[2]

Malakand

In 1897, Churchill attempted to travel to both report and, if necessary, fight in the Greco-Turkish War, but this conflict effectively ended before he could arrive. Later, while preparing for a leave in England, Churchill heard that three brigades of the British Army were going to fight against a Pashtun tribe and he asked his superior officer if he could join the fight.[16] He fought under the command of General Jeffery, who was the commander of the second brigade operating in Malakand, in what is now Pakistan. Jeffery sent fifteen scouts and Churchill to explore the Mamund Valley; while on reconnaissance, they encountered an enemy tribe, dismounted from their horses and opened fire. After an hour of shooting, their reinforcements, the 35th Sikhs arrived, and the fire gradually ceased and the brigade and the Sikhs marched on. Hundreds of tribesmen then ambushed them and opened fire forcing them to retreat. As they were retreating four men were carrying an injured officer but the fierceness of the fight forced them to leave him behind. The man who was left behind was slashed to death in front of Churchill’s eyes; afterwards he wrote, "I forgot everything else at this moment except a desire to kill this man".[17] However the Sikhs' numbers were being depleted so the next commanding officer told Churchill to get the rest of the men and boys to safety.

Before he left he asked for a note so he would not be charged with desertion.[18] He received the note, quickly signed, and headed up the hill and alerted the other brigade, whereupon they then engaged the army. The fighting in the region dragged on for another two weeks before the dead could be recovered. Churchill wrote in his journal: "Whether it was worth it I cannot tell."[17][19] An account of the Siege of Malakand was published in December 1900 as the The Story of the Malakand Field Force. He received £600 for his account. During the campaign, he also wrote articles for the newspapers The Pioneer and The Daily Telegraph.[2] His account of the battle was one of his first published stories, for which he received £5 per column from The Daily Telegraph.[20]

Sudan

Churchill was transferred to Egypt in 1898 where he visited Luxor before joining an attachment of the 21st Lancers serving in Sudan under the command of General Herbert Kitchener. During his time he encountered two future military officers of the First World War - Douglas Haig, then a captain and Earl Jellicoe, then a gunboat lieutenant.[2] While in the Sudan, Churchill participated in what has been described as the last meaningful British cavalry charge at the Battle of Omdurman in September 1898. He also served as a war correspondent for the Morning Post. By October 1898, he had returned to Britain and begun work on his two-volume work;The River War, an account of the reconquest of the Sudan published the following year. Churchill stood for parliament in 1899 as a Conservative candidate in Oldham in a by-election, which he lost, coming third.[2]

South Africa

After Churchill's failure at the election in Oldham he went to South Africa in 1899 to report on the Second Boer War as a war correspondent. On 12 October 1899, the war between Britain and the Boer Republics broke out in South Africa. Churchill was captured and held in a POW camp in Pretoria. Churchill escaped from his prison camp and travelled almost 300 miles (480 km) to Portuguese Lourenço Marques in Delagoa Bay, with the assistance of an English mine manager.[2] His escape made him a minor national hero for a time in Britain, though instead of returning home, he rejoined General Redvers Buller's army on its march to relieve the British at the Siege of Ladysmith and take Pretoria.[2] This time, although continuing as a war correspondent, Churchill gained a commission in the South African Light Horse Regiment. He was one of the first British troops into Ladysmith and Pretoria; in fact, he and the Duke of Marlborough, his cousin, were able to get ahead of the rest of the troops in Pretoria, where they demanded and received the surrender of 52 Boer guards of the prison camp there.[2]

In 1900, he returned to England on the RMS Dunottar Castle, the same ship on which he set sail for South Africa eight months earlier,[21] and he published books on the Boer war, London to Ladysmith via Pretoria and Ian Hamilton's March, which were published in May and October respectively.[2]

Early years in Parliament

After his failure to be elected in Oldham in 1899, he returned again to stand in the 1900 general election (also known as "the Khaki election"). This time he was elected; but rather than attending the opening of Parliament, he embarked on a speaking tour throughout Britain and the United States, in the process raising ten thousand pounds for himself. (Members of Parliament were unpaid in those days and Churchill was not rich by the standards of other MPs at that time.) In both these elections, his campaign expenses were paid by his cousin the 9th Duke of Marlborough.[22]

In Parliament, Churchill became associated with a group of Tory dissidents led by Lord Hugh Cecil called the Hughligans, a play of words on "hooligans". During his first parliamentary session, Churchill provoked controversy by opposing what he viewed as the government's extravagant military expenditure.[23] By 1903, he was drawing away from Lord Hugh's views. He also opposed the Liberal Unionist leader Joseph Chamberlain, whose party was in coalition with the Conservatives. Chamberlain proposed extensive tariffs intended to protect Britain's economic dominance. This earned Churchill the detestation of his own supporters—indeed, Conservative backbenchers even staged a walkout once while he was speaking.[24] His own constituency effectively deselected him, although he continued to sit for Oldham until the next general election.

In 1904, Churchill's dissatisfaction with the Conservatives had grown so strong that, on returning from the Whitsun recess, he crossed the floor to sit as a member of the Liberal Party. It was rumoured at the time that his real reason in doing so was that he would receive an official salary.[25] As a Liberal, he continued to campaign for free trade. He won the seat of Manchester North West (carefully selected for him by the party - his electoral expenses were paid for by his uncle Lord Tweedmouth, a senior Liberal[26] in the 1906 general election. As a Liberal, Churchill played an instrumental role in passing a law that established a minimum wage in Britain.

From 1903 until 1905, Churchill was also engaged in writing Lord Randolph Churchill, a two-volume biography of his father which was published in 1906 and received much critical acclaim.[27] However, filial devotion caused him to soften some of his father's less attractive aspects.[28] Theodore Roosevelt, who had known Lord Randolph, reviewed the book as "a clever tactful and rather cheap and vulgar life of that clever tactful and rather cheap and vulgar egotist".[29] Some historians suggest Churchill used the book in part to vindicate his own career and in particular to justify crossing the floor.[30]

Ministerial office

Growing prominence

When the Liberals took office, with Henry Campbell-Bannerman as Prime Minister, in December 1905, Churchill became Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies. Serving under the Secretary of State for the Colonies, Victor Bruce, 9th Earl of Elgin, Churchill dealt with the adoption of constitutions for the defeated Boer republics of the Transvaal and Orange River Colony and with the issue of 'Chinese slavery' in South African mines. He also became a prominent spokesman on free trade.

Churchill became the most prominent member of the Government outside the Cabinet, and when Campbell-Bannerman was succeeded by Herbert Henry Asquith in 1908, it came as little surprise when Churchill was promoted to the Cabinet as President of the Board of Trade. Under the law at the time, a newly appointed Cabinet Minister was obliged to seek re-election at a by-election. Churchill lost his Manchester seat to the Conservative William Joynson-Hicks but was soon elected in another by-election at Dundee constituency. As President of the Board of Trade, he pursued radical social reforms known as the Liberal reforms, enacted in conjunction with David Lloyd George, the new Chancellor of the Exchequer. Most notable amongst these was the People's Budget that led to the downfall of the House of Lords as well as the opposition of Navy building by then First Lord of the Admiralty, Reginald McKenna.

In 1910, Churchill was promoted to Home Secretary, where he was to prove somewhat controversial. A famous photograph from the time shows the impetuous Churchill at the scene of the January 1911 Siege of Sidney Street, peering around a corner to view a gun battle between cornered anarchists and Scots Guards. His role attracted much criticism. The building under siege caught fire and Churchill supported the decision to deny the fire brigade access, forcing the criminals to choose surrender or death. Arthur Balfour asked, "He [Churchill] and a photographer were both risking valuable lives. I understand what the photographer was doing but what was the Right Honourable gentleman doing?"

1910 also saw Churchill preventing the army being used to deal with a dispute at the Cambrian Colliery mine in Tonypandy. Initially, Churchill blocked the use of troops fearing a repeat of the 1887 'bloody Sunday' in Trafalgar Square. Nevertheless, troops were deployed to protect the mines and to avoid riots when thirteen strikers were tried for minor offences, an action that broke the tradition of not involving the military in civil affairs and led to lingering dislike for Churchill in Wales.

First Lord of the Admiralty

In 1911, Churchill became First Lord of the Admiralty, a post he held into World War I. He gave impetus to reform efforts, including development of naval aviation, tanks, and the switch in fuel from coal to oil, a massive engineering task, also depending on securing Mesopotamia's oil rights, bought circa 1907 through the secret service using the Royal Burmah Oil Company as a front company.[citation needed]

The development of the tank was financed from naval research funds via the Landships Committee, and, although a decade later development of the battle tank would be seen as a stroke of genius, at the time it was seen as misappropriation of funds. The tank was deployed too early and in too small numbers, much to Churchill's annoyance. He wanted a fleet of tanks used to surprise the Germans under cover of smoke, and to open a large section of the trenches by crushing barbed wire and creating a breakthrough sector.

In 1915, Churchill was one of the political and military engineers of the disastrous Gallipoli landings on the Dardanelles during World War I. Churchill took much of the blame for the fiasco, and when Prime Minister Asquith formed an all-party coalition government, the Conservatives demanded Churchill's demotion as the price for entry. For several months Churchill served in the sinecure of Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, before resigning from the government, feeling his energies were not being used. He rejoined the army, though remaining an MP, and served for several months on the Western Front commanding the 6th Battalion of the Royal Scots Fusiliers. During this period, his second-in-command was a young Archibald Sinclair who later led the Liberal Party.

Return to power

In December 1916, Asquith resigned as Prime Minister and was replaced by David Lloyd George. The time was thought not yet right to risk the Conservatives' wrath by bringing Churchill back into government. However, in July 1917, Churchill was appointed Minister of Munitions, and in January 1919, Secretary of State for War and Secretary of State for Air. He was the main architect of the Ten Year Rule, but the major preoccupation of his tenure in the War Office was the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War. Churchill was a staunch advocate of foreign intervention, declaring that Bolshevism must be "strangled in its cradle".[31] He secured, from a divided and loosely organised Cabinet, intensification and prolongation of the British involvement beyond the wishes of any major group in Parliament or the nation — and in the face of the bitter hostility of Labour. In 1920, after the last British forces had been withdrawn, Churchill was instrumental in having arms sent to the Poles when they invaded Ukraine.

He became Secretary of State for the Colonies in 1921 and was a signatory of the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921, which established the Irish Free State. Churchill always disliked Éamon de Valera, the Sinn Féin leader. Churchill, to protect British maritime interests engineered the Irish Free State agreement to include three Treaty Ports — Queenstown (Cobh), Berehaven and Lough Swilly — which could be used as Atlantic bases by the Royal Navy.[32] Under cuts instituted by Churchill as Chancellor of the Exchequer and others, the bases were neglected. Under the terms of the Anglo-Irish Trade Agreement the bases were returned to the newly constituted Éire in 1938.

As the President of the Air Council, he advocated the use of tear gas against insurgents, arguing that it was riduculous to "lacerate" a man with lead but "boggle" at making his eyes water.

Career between the wars

Second crossing of the floor

In 1920, as Secretaries of State for War and Air, Churchill had responsibility for quelling the rebellion of Kurds and Arabs in British-occupied Iraq.

In October 1922, Churchill underwent an operation to remove his appendix. Upon his return, he learned the government had fallen and a General Election was looming. The Liberal Party was now beset by internal division and Churchill's campaign was weak. Even the D. C. Thomson & Co. Ltd, a local newspaper publisher, published vitriolic rhetoric about his political status in the city, particularly from David Coupar Thomson. At one meeting, he was only able to speak for 40 minutes when he was barracked by a section of the audience.[33] He came only fourth in the poll and lost his seat at Dundee to the prohibitionist Edwin Scrymgeour, quipping later that he left Dundee "without an office, without a seat, without a party and without an appendix".[34]

Churchill stood for the Liberals again in the 1923 general election, losing in Leicester, but over the next few months he moved towards the Conservative Party in all but name. His first electoral contest as an Independent candidate, fought under the label of "Independent Anti-Socialist," was a narrow loss in a by-election in a London constituency — his third electoral defeat in less than two years. However, he stood for election yet again several months later in the General Election of 1924, again as an Independent candidate, this time under the label of "Constitutionalist" although with Conservative backing, and was finally elected to represent Epping - a statue in his honour in Woodford Green was erected when Woodford Green was part of the Epping constituency. The following year, he formally rejoined the Conservative Party, commenting wryly that "Anyone can rat [change parties], but it takes a certain ingenuity to re-rat." [34]

Chancellor of the Exchequer

He was appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1924 under Stanley Baldwin and oversaw Britain's disastrous return to the Gold Standard, which resulted in deflation, unemployment, and the miners' strike that led to the General Strike of 1926. This decision prompted the economist John Maynard Keynes to write The Economic Consequences of Mr. Churchill, arguing that the return to the gold standard at the pre-war parity in 1925 (£1=$4.86) would lead to a world depression. Interestingly, the pamphlet did not criticise the decision to return to the gold standard per se. Churchill later regarded this as the greatest mistake of his life; he stated he was not an economist and that he acted on the advice of the Governor of the Bank of England, Montagu Norman. However in discussions at the time with former Chancellor McKenna Churchill acknowledged that the return to the gold standard and the resulting 'dear money' policy was economically bad. In those discussions he maintained the policy as fundamentally political - a return to the pre war conditions in which he believed (James op cit 206)

During the General Strike of 1926, Churchill was reported to have suggested that machine guns be used on the striking miners. Churchill edited the Government's newspaper, the British Gazette, and, during the dispute, he argued that "either the country will break the General Strike, or the General Strike will break the country." Furthermore, he controversially claimed that the Fascism of Benito Mussolini had "rendered a service to the whole world," showing, as it had, "a way to combat subversive forces" — that is, he considered the regime to be a bulwark against the perceived threat of Communist revolution. At one point, Churchill went as far as to call Mussolini the "Roman genius… the greatest lawgiver among men."[35]

Political isolation

The Conservative government was defeated in the 1929 General Election. Churchill did not seek election to the Conservative Business Committee, the forerunner to the Shadow Cabinet. In the next two years, Churchill became estranged from the Conservative leadership over the issues of protective tariffs and Indian Home Rule, which he bitterly opposed. He further distanced himself from the party as a whole by his friendships with press barons, financiers and people seen as unsound and by his political views.When Ramsay MacDonald formed the National Government in 1931, Churchill was not invited to join the Cabinet. He was now at the low point in his career, in a period known as "the wilderness years".

He spent much of the next few years concentrating on his writing, including Marlborough: His Life and Times — a biography of his ancestor John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough — and A History of the English Speaking Peoples (which was not published until well after World War II). When struck by a taxi he wrote an article about the experience. He supported himself largely by his writing and was one of the best paid writers of his time. He spent so much time in writing that he rarely attended Parliament unless he intended making a speech. He continued writing A History of the English Speaking Peoples while First Lord of the Admiralty at the height of the Norwegian campaign [36])

His political views, set forth in his 1930 Romanes Election and published as Parliamentary Government and the Economic Problem (OUP) (republished in 1932 in his collection of essays "Thoughts and Adventures" (in America under the title Amid These Storms) involved abandoning universal suffrage, a return to a property franchise, proportional representation for the major cities and an economic 'sub parliament'. He continued to support Mussolini, in 1933 writing of him as 'the greatest lawgiver among men' [37]. Some suspected him of wishing to become the "British Mussolini". Harold Nicholson for example wrote in 1932 of a new Britain governed by Churchill and Oswald Mosley in his novel Public Faces.

He became most notable for his outspoken opposition towards the granting of independence to India (see Simon Commission and Government of India Act 1935). He denigrated the father of the Indian independence movement, Mahatma Gandhi, as "a half-naked fakir" who "ought to be laid, bound hand and foot, at the gates of Delhi and then trampled on by an enormous elephant with the new viceroy seated on its back." His views on India were set by his experience as a junior cavalry officer stationed in India in the 1890s and are shown in his book My Early Life which was published in 1930 [38]. He helped found the India Defence League a group dedicated to the preservation of British power in India. In speeches and press articles in this period he forecast widespread British unemployment and civil strife in India should independence be granted to India. [39].

He opposed the official government policy both in and out of parliament. His supporters 'stacked' the back bench Conservative India Committee in March 1931, prompting Baldwin on 13th March to attack Churchill by quoting Churchill's own speech on the Amritsar massacre and challenging his critics to depose him if they wished. The parliamentary assault collapsed [40].Out of parliament and on the eve of the St George by-election in which an independent supported by Lord Rothermere and Lord Beaverbrook (both of whom were Churchill's personal friends) and their respective newspapers stood against Duff Cooper, the official conservative candidate, Churchill spoke at a rally in which he attacked Baldwin's policy. Baldwin attacked the press barons in his speech on 18th March in supporting Duff Cooper's candidacy. [41] Duff Cooper won easily and the Conservative Party closed ranks behind Baldwin. The India Defence League folded shortly afterwards. Churchill was isolated and seen as a man who put personal ambition before both his party and the policy supported by all sides in Parliament.

Soon, though, his attention was drawn to the rise of Adolf Hitler and the dangers of Germany's rearmament. He later tried to portray himself as being for a time, a lone voice calling on Britain to strengthen itself to counter the belligerence of Germany.[42]. However Lord Lloyd was the first to so agitate [43]. Churchill's attitude toward the Fascist dictators was ambiguous. In contemporary newspaper articles he referred to the Spanish Republican government as a communist front, and Franco's army as the "Anti red movement [44]

In 1937 in his book "Great Contemporaries", Churchill wrote: "If our country were defeated, I hope we should find a champion as admirable (as Hitler) to restore our courage and lead us back to our place among the nations". In the same work, Churchill expressed a hope that despite Hitler's apparent dictatorial tendencies, he would use his power to rebuild Germany into a worthy member of the world community. The terms Churchill wrote this hope in suggested that if any calamity was to return to Europe, Hitler was most likely to be the responsible party and the entire article seems to be something of a personal challenge to Hitler to prove Churchill wrong.

He was also an outspoken supporter of King Edward VIII during the Abdication Crisis, leading to some speculation that he might be appointed Prime Minister if the King refused to take Baldwin's advice and consequently the government resigned. However, this did not happen, and Churchill found himself politically isolated and bruised for some time after this.

Churchill was a fierce critic of Neville Chamberlain's appeasement of Hitler, leading the wing of the Conservative Party that opposed the Munich Agreement which Chamberlain famously declared to mean "peace in our time".[45] In a speech to the House of Commons, he bluntly (and prophetically) stated, "You were given the choice between war and dishonour. You chose dishonour, and you will have war." [46]

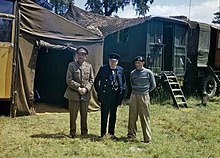

Role as wartime Prime Minister

"Winston is back"

After the outbreak of the World War II Churchill was appointed First Lord of the Admiralty and a member of the War Cabinet, just as he was in the first part of the World War I. The Navy, by myth, sent out the signal: "Winston is back."[47]

In this job, he proved to be one of the highest-profile ministers during the so-called "Phony War", when the only noticeable action was at sea. Churchill advocated the pre-emptive occupation of the neutral Norwegian iron-ore port of Narvik and the iron mines in Kiruna, Sweden, early in the War. However, Chamberlain and the rest of the War Cabinet disagreed, and the operation was delayed until the German invasion of Norway, which was successful.

Bitter beginnings of the war

On 10 May 1940, hours before the German invasion of France by a lightning advance through the Low Countries, it became clear that, following failure in Norway, the country had no confidence in Chamberlain's prosecution of the war and so Chamberlain resigned. The commonly accepted version of events states that Lord Halifax turned down the post of Prime Minister because he believed he could not govern effectively as a member of the House of Lords instead of the House of Commons. Although traditionally, the Prime Minister does not advise the King on the former's successor, Chamberlain wanted someone who would command the support of all three major parties in the House of Commons. A meeting between Chamberlain, Halifax, Churchill and David Margesson, the government Chief Whip, led to the recommendation of Churchill, and, as a constitutional monarch, George VI asked Churchill to be Prime Minister and to form an all-party government. Churchill's first act was to write to Chamberlain to thank him for his support.[48]

Churchill's greatest achievement was his refusal to capitulate when defeat seemed imminent, and he remained a strong opponent of any negotiations with Germany throughout the war. Few others in the Cabinet had this degree of resolve. By adopting a policy of no surrender, Churchill kept democracy alive in the UK and created the basis for the later Allied counter-attacks of 1942-45, with Britain serving as a platform for the supply of Soviet Union and the liberation of Western Europe.

Among the many consequences of this stand was that Britain was maintained as a base from which the Allies could attack Germany, thereby ensuring that the Soviet sphere of influence did not extend over Western Europe at the end of the war.

In response to previous criticisms that there had been no clear single minister in charge of the prosecution of the war, Churchill created and took the additional position of Minister of Defence. He immediately put his friend and confidant, the industrialist and newspaper baron Lord Beaverbrook, in charge of aircraft production. It was Beaverbrook's business acumen that allowed Britain to quickly gear up aircraft production and engineering that eventually made the difference in the war.

Churchill's speeches were a great inspiration to the embattled British. His first speech as Prime Minister was the famous "I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears, and sweat". He followed that closely with two other equally famous ones, given just before the Battle of Britain. One included the immortal line, "we shall fight in France, we shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be, we shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender." The other included the equally famous "Let us therefore brace ourselves to our duties, and so bear ourselves, that if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will still say, 'This was their finest hour.' "

At the height of the Battle of Britain, his bracing survey of the situation included the memorable line "Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few", which engendered the enduring nickname "The Few" for the Allied fighter pilots who won it. One of his most memorable war speeches came on 10 November 1942 at the Lord Mayor's Luncheon at Mansion House in London, in response to the Allied victory at the Second Battle of El Alamein. Churchill famously said:

"This is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning."

Without having much in the way of sustenance or good news to offer the British people, he took a political risk in deliberately choosing to emphasise the dangers instead.

"Rhetorical power," wrote Churchill, "is neither wholly bestowed, nor wholly acquired, but cultivated."

Relations with the United States

His good relationship with Franklin D. Roosevelt secured vital food, oil and munitions via the North Atlantic shipping routes. It was for this reason that Churchill was relieved when Roosevelt was re-elected in 1940. Upon re-election, Roosevelt immediately set about implementing a new method of providing military hardware and shipping to Britain without the need for monetary payment. Put simply, Roosevelt persuaded Congress that repayment for this immensely costly service would take the form of defending the USA; and so Lend-lease was born. Churchill had 12 strategic conferences with Roosevelt which covered the Atlantic Charter, Europe first strategy, the Declaration by the United Nations and other war policies. After Pearl Harbor was attacked, Churchill's first thought in anticipation of U.S. help was, "We have won the war!",[49] Then 26 December 1941 Churchill addressed a joint meeting of the U.S. Congress, asking of Germany and Japan, "What kind of people do they think we are?".[50] Churchill initiated the Special Operations Executive (SOE) under Hugh Dalton's Ministry of Economic Warfare, which established, conducted and fostered covert, subversive and partisan operations in occupied territories with notable success; and also the Commandos which established the pattern for most of the world's current Special Forces. The Russians referred to him as the "British Bulldog".

Churchill's health was fragile, as shown by a mild heart attack he suffered in December 1941 at the White House and also in December 1943 when he contracted pneumonia. Despite this, he travelled over 100,000 miles (160,000 km) throughout the war to meet other national leaders. For security, he usually travelled using the alias Colonel Warden.[51]

Churchill was party to treaties that would redraw post-World War II European and Asian boundaries. These were discussed as early as 1943. Proposals for European boundaries and settlements were officially agreed to by Harry S. Truman, Churchill, and Stalin at Potsdam. At the second Quebec Conference in 1944 he drafted and together with U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed a toned down version of the original Morgenthau Plan, where they pledged to convert Germany after its unconditional surrender "into a country primarily agricultural and pastoral in its character."[52] Churchill's strong relationship with Harry Truman was also of great significance to both countries. While he clearly regretted the loss of his close friend and counterpart Franklin D. Roosevelt, Churchill was enormously supportive of Truman in his first days in office, calling him, "the type of leader the world needs when it needs him most."

Relations with the Soviet Union

When Hitler invaded the Soviet Union, Winston Churchill, a vehement anti-Communist, famously stated "If Hitler were to invade Hell, I should find occasion to make a favourable preference to the Devil," regarding his policy toward Stalin. Soon, British supplies and tanks were flowing to help the Soviet Union.[53]

The settlement concerning the borders of Poland, that is, the boundary between Poland and the Soviet Union and between Germany and Poland, was viewed as a betrayal in Poland during the post-war years, as it was established against the views of the Polish government in exile. It was Winston Churchill, who tried to motivate Mikołajczyk who was Prime Minister of the Polish government in exile, to accept Stalin's wishes, but Mikołajczyk refused. Churchill was convinced that the only way to alleviate tensions between the two populations was the transfer of people, to match the national borders. As he expounded in the House of Commons in 1944, "Expulsion is the method which, insofar as we have been able to see, will be the most satisfactory and lasting. There will be no mixture of populations to cause endless trouble... A clean sweep will be made. I am not alarmed by these transferences, which are more possible in modern conditions." However the resulting expulsions of Germans was carried out by the Soviet Union in a way which resulted in much hardship and, according to a 1966 report by the West German Ministry of Refugees and Displaced Persons, the death of over 2,100,000. Churchill opposed the effective annexation of Poland by the Soviet Union and wrote bitterly about it in his books, but he was unable to prevent it at the conferences.

On 9 October 1944, he and Eden were in Moscow, and that night they met Joseph Stalin in the Kremlin, without the Americans. Bargaining went on throughout the night. Churchill wrote on a piece of paper that Stalin had a 90 percent "interest" in Romania, Britain a 90 percent "interest" in Greece, both Russia and Britain a 50 percent "interest" in Yugoslavia.[54] The crucial questions arose when the Ministers of Foreign Affairs discussed "percentages" in Eastern Europe. Molotov's proposals were that Russia should have a 75 percent interest in Hungary, 75 percent in Bulgaria, and 60 percent in Yugoslavia. This was Stalin's price for ceding Greece. Eden tried to haggle: Hungary 75/25, Bulgaria 80/20, but Yugoslavia 50/50. After lengthy bargaining they settled on an 80/20 division of interest between Russia and Britain in Bulgaria and Hungary, and a 50/50 division in Yugoslavia. U.S. Ambassador Averell Harriman was informed only after the bargain was struck. This so called Percentages agreement was sealed by Stalin ticking Churchill's paper.[55][56]

Dresden bombings controversy

Between February 13 and February 15 1945, British and the U.S. bombers attacked the German city of Dresden, which was crowded with German wounded, refugees[57] and Soviet prisoners of war.[citation needed] Because of the strategic insignificance and the large numbers of civilian casualties, this remains one of the most controversial Western Allied actions of the war. Ultimately, responsibility for the attack lay with Churchill, which is why he has been criticised for allowing the bombings to happen. However, no consensus has been reached by historians whether he can be accused of war crimes and deliberate violation of the Geneva Conventions. Following the bombing Churchill stated in a top secret telegram:

"It seems to me that the moment has come when the question of bombing of German cities simply for the sake of increasing the terror, though under other pretexts, should be reviewed." "...I feel the need for more precise concentration upon military objectives such as oil and communications behind the immediate battle-zone, rather than on mere acts of terror and wanton destruction, however impressive."

After World War II

Although the importance of Churchill's role in World War II is undeniable, he had many enemies in his own country. He expressed contempt for a number of popular ideas, in particular public health care and better public education, and his stance produced much popular opposition, particularly among those who had fought in the war.[citation needed] Immediately following the close of the war in Europe, Churchill was defeated in the 1945 election by Clement Attlee and the Labour Party.[58] Some historians think that many British voters believed that the man who had led the nation so well in war was not the best man to lead it in peace. Others see the election result as a reaction not against Churchill personally, but against the Conservative Party's record in the 1930s under Baldwin and Chamberlain. During the opening broadcast of the election campaign, Churchill astonished many of his admirers by warning that a Labour government would introduce into Britain "some form of Gestapo, no doubt humanely administered in the first instance". Churchill had been genuinely worried during the war by the inroads of state bureaucracy into civil liberty, and was clearly influenced by Friedrich Hayek's anti-totalitarian tract, The Road to Serfdom (1944).

Winston Churchill was an early supporter of the pan-Europeanism. In his famous speech at the University of Zurich in 1946, Winston Churchill called for a "United States of Europe" and the creation of a "Council of Europe". He also participated in the Hague Congress of 1948, which discussed the future structure and role of this Council of Europe. The Council of Europe was finally founded as the first European institution through the Treaty of London of 5 May 1949 and has its seat in Strasbourg.

However, this is often seen as his supporting Britain's membership in a united Europe, which is far from the truth. Rather, he saw Pan Europeanism as a Franco-German project which would foster cooperation amongst European countries and the rest of the world and prevent war on the European continent. This can be seen in Churchill’s landmark refusal to join the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) in 1951 as well as his often quoted speech in which he said of Britain's role with Europe:

We have our own dream and our own task. We are with Europe, but not of it. We are linked but not combined. We are interested and associated but not absorbed.[59]

This stance has, arguably, shaped Britain's feelings toward European integration and its subsequent general ambivalence towards all things Europe. He saw Britain's place as separate from the continent, much more in-line with the countries of the Commonwealth and the Empire and with the United States, the so-called Anglosphere. As evidenced in his speech at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri, given on 5 March 1946 where as a guest of Harry S. Truman, he declared:

Neither the sure prevention of war, nor the continuous rise of world organisation will be gained without what I have called the fraternal association of the English-speaking peoples. This means a special relationship between the British Commonwealth and Empire and the United States.[60]

It was also during this speech that he famously popularised the term "The Iron Curtain":

From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an Iron Curtain has descended across the continent. Behind that line lie all the capitals of the ancient states of Central and Eastern Europe. Warsaw, Berlin, Prague, Vienna, Budapest, Belgrade, Bucharest and Sofia, all these famous cities and the populations around them lie in what I must call the Soviet sphere.[60]

Churchill was instrumental in giving France a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council (which provided another European power to counterbalance the Soviet Union's permanent seat).

Second term

After Labour's defeat in the General Election of 1951, Churchill again became Prime Minister. His third government — after the wartime national government and the brief caretaker government of 1945 — would last until his resignation in 1955. During this period, he renewed what he called the "special relationship" between Britain and the United States, and engaged himself in the formation of the post-war order. On racial questions, Churchill was still a late Victorian. He tried in vain to manoeuvre the cabinet into restricting West Indian immigration. "Keep England White" was a good slogan, he told the cabinet in January 1955.[61]

His domestic priorities were, however, overshadowed by a series of foreign policy crises, which were partly the result of the continued decline of British military and imperial prestige and power. Being a strong proponent of Britain as an international power, Churchill would often meet such moments with direct action. Trying to retain what he could of the Empire, he once stated that, "I will not preside over a dismemberment."

The Mau Mau Rebellion

In 1951, grievances against the colonial distribution of land came to a head with the Kenya Africa Union demanding greater representation and land reform. When these demands were rejected, more radical elements came forward, launching the Mau Mau rebellion in 1952. On 17 August 1952, a state of emergency was declared, and British troops were flown to Kenya to deal with the rebellion. As both sides increased the ferocity of their attacks, the country moved to full-scale civil war.

In 1953, the Lari massacre, perpetrated by Mau-Mau insurgents against Kikuyu loyal to the British, changed the political complexion of the rebellion and gave the public-relations advantage to the British. Churchill's strategy was to use a military stick, extreme repression such as public executions, combined with implementing many of the concessions that Attlee's government had blocked in 1951. He ordered an increased military presence and appointed General Sir George Erskine, who would implement Operation Anvil in 1954 that defeated the rebellion in the city of Nairobi. Operation Hammer, in turn, was designed to kill rebels in the countryside. Churchill ordered peace talks opened, but these collapsed shortly after his leaving office.

Malayan Emergency

In Malaya, a rebellion against British rule had been in progress since 1948. Once again, Churchill's government inherited a crisis, and once again Churchill chose to use direct military action against those in rebellion while attempting to build an alliance with those who were not. He stepped up the implementation of a "hearts and minds" campaign and approved the creation of fortified villages, a tactic that would become a recurring part of Western military strategy in South-east Asia. (See Vietnam War).

The Malayan Emergency was a more direct case of a guerrilla movement, centred in an ethnic group, but backed by the Soviet Union. As such, Britain's policy of direct confrontation and military victory had a great deal more support than in Iran or in Kenya. At the highpoint of the conflict, over 35,500 British troops were stationed in Malaya. As the rebellion lost ground, it began to lose favour with the local population.

While the rebellion was slowly being defeated, it was equally clear that colonial rule from Britain was no longer plausible. In 1953, plans were drawn up for independence for Singapore and the other crown colonies in the region. The first elections were held in 1955, just days before Churchill's own resignation, and in 1957, under Prime Minister Anthony Eden, Malaya became independent.

Stroke

In June 1953, when he was 78, Churchill suffered a stroke after a meeting with the Italian Prime Minister Alcide De Gasperi at 10 Downing Street. News of this was kept from the public and from Parliament, who were told that Churchill was suffering from exhaustion. He went to his country home, Chartwell, to recuperate from the effects of the stroke which had affected his speech and ability to walk. He returned to public life in October to make a speech at a Conservative Party conference at Margate, having decided that if he couldn't make the speech, he would retire as Prime Minister — but he was able to deliver it without problems.

Family and personal life

On 12 September 1908 at the socially desirable St. Margaret's, Westminster, Churchill married Clementine Hozier, a woman whom he had met at a dinner party that March (he had proposed to actress Ethel Barrymore but was turned down). They had five children: Diana; Randolph; Sarah, who co-starred with Fred Astaire in Royal Wedding; Marigold (1918–21), who died in early childhood; and Mary, who has written a book about her parents. Churchill's son Randolph and his grandsons Nicholas Soames and Winston all followed him into Parliament. The daughters tended to marry politicians and support their careers.

Clementine's mother was Lady Blanche Hozier, second wife of Sir Henry Montague Hozier and a daughter of the 7th Earl of Airlie. Clementine's paternity, however, is open to debate. Lady Blanche was well known for sharing her favours and was eventually divorced as a result. She maintained that Clementine's father was Capt. William George "Bay" Middleton, a noted horseman. But Clementine's biographer Joan Hardwick has surmised, due to Sir Henry Hozier's reputed sterility, that all Lady Blanche's "Hozier" children were actually fathered by her sister's husband, Algernon Bertram Freeman-Mitford, better known as a grandfather of the famous Mitford sisters.

When not in London on government business, Churchill usually lived at Chartwell House, his home in Kent, two miles (3 km) south of Westerham. He and his wife bought the house in 1922 and lived there until his death in 1965. During his Chartwell stays, he enjoyed writing as well as painting, bricklaying, and admiring the estate's famous black swans.

For much of his life, Churchill battled with depression (or perhaps a sub-type of manic-depression), which he called his black dog.[62]

Churchill as a painter

As a painter he was prolific, with over 570 paintings and two sculptures; he received a Diploma from the Royal Academy of London. Approximately 350 paintings are housed in Churchill's garden Studio at Chartwell. His paintings were catalogued after his death by historian David Coombs with the support of the Churchill family. Coombs has published two books on the subject. The modern archive of Churchill's art work is managed by designer Tony Malone, who oversees the administration and management of digital catalogue. Anthea Morton Saner and the Churchill Heritage Trust are responsible for all copyrights.

Churchill began painting in his 40s following a personal and political disaster, the Dardanelles Campaign in 1915. He is quoted as telling the painter Sir John Rothenstein: "If it weren't for painting, I couldn't live; I couldn't bear the strain of things." In 1921, Winston Churchill's artwork was exhibited at the prestigious Galerie Druet in the Rue Royale, under the pseudonym Charles Morin. Six paintings were said to have been sold. In 1948, he was bestowed the prestigious recognition of Honorary Academician Extraordinary by the Royal Academy of Arts. Sir Hugh Casson, President of the Royal Academy of Art, introduced Churchill as "an amateur of considerable natural ability who, had he had the time (to study and practice), could have held his own with most professionals ... especially as a colourist."

For more than forty years he found contentment in his painting pastime.[2] Yet, as important as it was to him, this fascinating aspect of his life remained relatively unknown for years. The first public exhibition of his paintings was under an assumed name and only a few major shows were held in his lifetime. The Winston Churchill Trust has permitted Churchill’s works of art to be made available in the form of original limited editions, bearing the unique embossed seal of the Churchill Trust.

Churchill's work has been displayed in art galleries and exhibitions in Europe, Canada, Australia, Japan and the United States. Works by Churchill can be found in the permanent collections of the following museums: The Royal Academy and the Tate Gallery, London; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.; the Dallas Museum of Art; the Museum of Art in Sao Paolo, Brazil. His association with these prestigious institutions gives credibility to Churchill's work as an artist. Some of Churchill’s art has been sold at the major Auction houses, and the latest work, 'View of Tinherir', was sold at Sotheby’s for a record £612,800 (over US$1,100,000), nearly three times its estimate. A 76 inch x 63.5 inch landscape painting by Winston fetched one million pounds in July 2007.[63]

Clubs and drinking

Like many politicians of his age, Churchill was also a member of several English gentlemen's clubs — the Reform Club and the National Liberal Club whilst he was a Liberal MP, and later the Athenaeum, Boodle's, Buck's, and Carlton Clubs when he was a Conservative. Despite his multiple memberships, Churchill was not a habitual clubman; he spent relatively little time in each of these, and preferred to conduct any lunchtime or dinner meetings at the Savoy Grill or the Ritz, or else in the Members' Dining Room of the House of Commons when meeting other MPs.

Churchill's fondness for alcoholic beverages was well-documented. While in India and South Africa, he got in the habit of adding small amounts of whisky to the water he drank in order to prevent disease. He was quoted on the subject as saying that "by dint of careful application I learned to like it." He consumed alcoholic drinks on a near-daily basis for long periods in his life, and frequently imbibed before, after, and during mealtimes. According to William Manchester in The Last Lion, Churchill's favourite whisky was Johnnie Walker Red. He is not generally however considered by historians to have been an alcoholic. The Churchill Centre states that Churchill made a bet with a man with the last name of Rothermere (possibly one of the Viscounts Rothermere) in 1936 that Churchill would be able to successfully abstain from drinking hard liquor for a year; Churchill apparently won the bet.[64]

Retirement and death

Aware that he was slowing down both physically and mentally, Churchill retired as Prime Minister in 1955 and was succeeded by Anthony Eden, who had long been his ambitious protégé (three years earlier, Eden had married Churchill's niece, Anne Clarissa Spencer-Churchill, his second marriage.) Upon his resignation, the Queen offered him a dukedom; he declined, sometimes voting in parliamentary divisions, but never again speaking in the House. He continued to serve as an MP for Woodford until he stood down for the last time at the 1964 General Elections. His private verdict on the Suez fiasco was: "I would never have done it without squaring the Americans, and once I'd started I'd never have dared stop".[65] In 1959, he became Father of the House, the MP with the longest continuous service. Churchill spent most of his retirement at Chartwell House in Kent, two miles (3 km) south of Westerham.

As Churchill's mental and physical faculties decayed, he began to lose the battle he had fought for so long against the "black dog" of depression. He found some solace in the sunshine and colours of the Mediterranean. He took long holidays with his literary adviser Emery Reves and Emery's wife, Wendy Russell, at La Pausa, their villa on the French Riviera, seldom joined by Clementine. He also took eight cruises aboard the yacht Christina as the guest of Aristotle Onassis. Once, when the Christina had to pass through the Dardanelles, Onassis gave instructions that it was to do so during the night, so as not to disturb his guest with unhappy memories.

In 1963, U.S. President John F. Kennedy, acting under authorisation granted by an Act of Congress, proclaimed Churchill the first Honorary Citizen of the United States.[66] Churchill was physically incapable of attending the White House ceremony, so his son and grandson accepted the award for him.

Churchill's final years were melancholy. He never resolved the love–hate relationship between himself and his son. Sarah was descending into alcoholism and Diana committed suicide in the autumn of 1963. Churchill himself suffered a number of minor strokes. It was a figure ravaged by age and sorrow who appeared at the window of his London home, 28 Hyde Park Gate, to greet the photographers on his ninetieth birthday in November 1964.

On 15 January 1965, Churchill suffered another stroke — a severe cerebral thrombosis — that left him gravely ill. He died at his home nine days later, at age 90, shortly after eight o'clock on the morning of 24 January 1965, 70 years to the day after his father's death.

Funeral

By decree of the Queen, his body lay in state for three days and a state funeral service was held at St Paul's Cathedral.[67] This was the first state funeral for a non-royal family member since 1914, and no other of its kind has been held since.

As his coffin passed down the Thames on the Havengore, the cranes of London's docklands bowed in a spontaneous salute. The Royal Artillery fired a 19-gun salute (as head of government), and the RAF staged a fly-by of sixteen English Electric Lightning fighters. The state funeral was the largest gathering of dignitaries in Britain as representatives from well over 100 countries attended, including French President Charles de Gaulle, Canadian Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson, Prime Minister of Rhodesia Ian Smith, former U.S. president Dwight Eisenhower, and many other heads of state, including past and present heads of state and government, and members of royalty. The cortège left London from Waterloo station, as (according to legend) Churchill had requested should he predecease De Gaulle.[68] The train was hauled by Battle of Britain class Locomotive No. 34051 — Winston Churchill.[69] Fittingly, this was the last great State occasion to be movingly commented upon by the great British broadcaster Richard Dimbleby who died of lung cancer in December 1965. The funeral also saw the largest assemblage of statesmen in the world until the funeral of Pope John Paul II in 2005.

At Churchill's request, he was buried in the family plot at St Martin's Church, Bladon, near Woodstock, not far from his birthplace at Blenheim. In the fields along the route, and at the stations through which the train passed, thousands stood in silence to pay their last respects. In 1998 his tombstone had to be replaced due to the large number of visitors over the years having eroded it and its surrounding area. A new stone was dedicated in a ceremony attended by members of the Spencer-Churchill family.[70]

Because the funeral took place on 30 January, people in the United States marked it by paying tribute to his friendship with Franklin D. Roosevelt because it was the anniversary of FDR's birth. The tributes were led by Roosevelt's children at the president's grave at the FDR Presidential Library. On 9 February 1965, Churchill's estate was probated at £304,044 (equivalent to about £3.8m in 2004).

Churchill as historian

Honours

Aside from receiving the great honour of a state funeral, Churchill also received numerous awards and honours, including being made an Honorary Citizen of the United States.

Churchill's cabinets

- Churchill War Ministry (May 1940–May 1945)

- Churchill Caretaker Ministry (May–July 1945)

Winston Churchill's third cabinet, October 1951 – April 1955

- Winston Churchill — Prime Minister and Minister of Defence

- Lord Simonds — Lord Chancellor

- Lord Woolton — Lord President of the Council

- Lord Salisbury — Lord Privy Seal and Leader of the House of Lords

- Rab Butler — Chancellor of the Exchequer

- Sir David Maxwell-Fyfe — Secretary of State for the Home Department

- Anthony Eden — Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs

- Oliver Lyttelton — Secretary of State for the Colonies

- Lord Ismay — Secretary of State for Commonwealth Relations

- James Stuart — Secretary of State for Scotland

- Peter Thorneycroft — President of the Board of Trade

- Lord Cherwell — Paymaster-General

- Sir Walter Monckton — Minister of Labour

- Harry Crookshank — Minister of Health and Leader of the House of Commons

- Harold Macmillan — Minister of Housing and Local Government

- Lord Leathers — Minister for the Co-ordination of Transport, Fuel, and Power

Changes

- March 1952: Lord Salisbury succeeds Lord Ismay as Commonwealth Relations Secretary. Salisbury remains also Lord Privy Seal and Leader of the House of Lords. Lord Alexander of Tunis succeeds Churchill as Minister of Defence.

- May 1952: Harry Crookshank succeeds Lord Salisbury as Lord Privy Seal, remaining Leader of the House of Commons. Salisbury remains Commonwealth Relations Secretary and Leader of the House of Lords. Crookshank's successor as Minister of Health is not in the Cabinet.

- November 1952: Lord Woolton becomes Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. Lord Salisbury succeeds Lord Woolton as Lord President. Lord Swinton succeeds Lord Salisbury as Commonwealth Relations Secretary.

- September 1953: Florence Horsbrugh, the Minister of Education, Sir Thomas Dugdale, the Minister of Agriculture, and Gwilym Lloyd George, the Minister of Food, enter the cabinet. The Ministry for the Co-ordination of Transport, Fuel, and Power, is abolished, and Lord Leathers leaves the Cabinet.

- October 1953: Lord Cherwell resigns as Paymaster General. His successor is not in the Cabinet.

- July 1954: Alan Lennox-Boyd succeeds Oliver Lyttelton as Colonial Secretary. Derick Heathcoat Amory succeeds Sir Thomas Dugdale as Minister of Agriculture.

- October 1954: Sir David Maxwell-Fyfe, now Lord Kilmuir, succeeds Lord Simonds as Lord Chancellor. Gwilym Lloyd George succeeds him as Home Secretary. The Food Ministry is merged into the Ministry of Agriculture. Sir David Eccles succeeds Florence Horsbrugh as Minister of Education. Harold Macmillan succeeds Lord Alexander of Tunis as Minister of Defence. Duncan Sandys succeeds Macmillan as Minister of Housing and Local Government. Osbert Peake, the Minister of Pensions and National Insurance, enters the Cabinet.

In popular culture and the media

- In a November 2002 BBC poll of the "100 Greatest Britons", he was proclaimed "The Greatest of Them All" based on approximately a million votes from BBC viewers.[71]

- Churchill was rated as one of the most influential leaders in history by Time Magazine.[citation needed]

References

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Literature 1953". Retrieved 2007-08-18.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Jenkins, Roy (2001). Churchill. London: Macmillan. 0-333-78290-9.

- ^ "PM record breakers". Number 10 Downing Street. Retrieved 2007-02-26.

- ^ http://www.winstonchurchill.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=638

- ^ Douglas J. Hall. "Lady Randolph in Winston's Boyhood". The Churchill Centre. Retrieved 2007-04-26.

- ^ Forty Ways to Look at Winston Churchill - randomhouse.com

- ^ John Mather, M.D. "Leading Churchill Myths: He stuttered". The Churchill Centre. Retrieved 2007-03-10.

- ^ Weiss, Deso (1964). Cluttering. New Jersey: Prentice Hall, Inc. p. 58. LC 64-25326.

- ^ a b c Russell, Douglas S. (1995-10-28). "Lt. Churchill: 4th Queen's Own Hussars". Churchill Centre. Retrieved 2007-02-26.

- ^ Brian Lamb. "Churchill: A Life, by Martin Gilbert". Booknotes /CSPAN December 22, 1991.

- ^ Churchill: A Life, New York, 1991, ISBN 0805023968

- ^ "On the character and achievement of Sir Winston Churchill". The Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science, Vol 23, No. 2 May, 1957 (May, 1957): pp 173-194.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Text "author G. K. Lewis" ignored (help) - ^ "Churchill Remembered: Recollections by Tony Benn MP, Lord Carrington, Lord Deedes and Mary Soames". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, Vol 11, 2001 (2001): p 404. Retrieved 2007-06-17.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Text "author T. Benn et al" ignored (help) - ^ T. E. C. Jr. M.D (5 November 1977). "Winston Churchill's Poignant Description of the Death of his Nanny". PEDIATRICS Vol. 60 No.: pp. 752.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ R. V. Jones. "Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill. 1874-1965". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society, Vol. 12, Nov., 1966 (Nov., 1966): pp. 34-105.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Sir Winston S. Churchill. "The Story Of The Malakand Field Force - An Episode of Frontier War". arthursclassicnovels.com. Retrieved 2007-03-17.

- ^ a b "Two opposition views of Afghanistan: British activist and Dutch MP want to know why their countries are participating in a dangerous adventure". Spectrazine. 20 March 2006.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Churchill, Winston (2002). My Early Life. Eland Publishing Ltd. pp. p. 143. ISBN 0907871623.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Churchill On The Frontier - Mamund Valley III". UK Commentators. 11 December 2004.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "WINTER 1896-97 (Age 22) - "The University of My Life"". Sir Winston Churchill. Retrieved 2007-03-17.

- ^ "FinestHour" (pdf). Journal of the Churchill Center and Societies, Summer 2005. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- ^ (p37 "The Aristocratic Adventurer by David Cannadine originally an essay entitled Churchill: The Aristocratic Adventurer" in "Aspects of Aristocracy" )

- ^ Roy Jenkins Churchill (Macmillan, 2001), pages 74-76 ISBN 0-333-78290-9

- ^ Roy Jenkins Churchill (Macmillan, 2001), page 86 ISBN 0-333-78290-9

- ^ (Cannadine op cit 27)

- ^ See Cannadine op cit p3

- ^ Roy Jenkins Churchill (Macmillan, 2001), pages 102-103 ISBN 0-333-78290-9

- ^ Roy Jenkins Churchill (Macmillan, 2001), page 101 ISBN 0-333-78290-9

- ^ Cannadine op cit 47

- ^ e.g. Cannadine op cit p 41, Robert Rhodes James - Churchill: A Study in Failure p34-35

- ^ Jeffrey Wallin with Juan Williams (2001-09-04). "Cover Story: Churchill's Greatness". Churchill Centre. Retrieved 2007-02-26.

- ^ Paul Addison, 'Churchill, Sir Winston Leonard Spencer (1874–1965)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Sept 2004; online edn, May 2007 http://0-www.oxforddnb.com.catalogue.ulrls.lon.ac.uk:80/view/article/32413, accessed 10 Sept 2007

- ^ "Churchill Howled Down" (HTML). Churchill the Evidence. 1922.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Hall, Douglas J. (1950). "All the Elections Churchill Ever Contested" (HTML). Churchill and... Politics. The Churchill Centre. Retrieved 2007-02-26. Cite error: The named reference "centre-710" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Picknett, Lynn, Prince, Clive, Prior, Stephen & Brydon, Robert (2002). War of the Windsors: A Century of Unconstitutional Monarchy, p. 78. Mainstream Publishing. ISBN 1-84018-631-3.

- ^ Cannadine op cit p 46

- ^ Canadine op cit p52

- ^ James op cit 257f

- ^ James op cit 260

- ^ James op cit p261

- ^ James op cit 263

- ^ Picknett, et al., p. 75.

- ^ Lord Lloyd and the decline of the British Empire J Charmley p 1,2, 213ff

- ^ James op cit p 408

- ^ Picknett, et al., pp. 149–50.

- ^ Current Biography 1942, p. 155

- ^ Brendon, Piers. "The Churchill Papers: Biographical History". Churchill Archives Centre, Churchill College, Cambridge. Retrieved 2007-02-26.

- ^ Self, Robert (2006). Neville Chamberlain: A Biography, p. 431. Ashgate. ISBN 9-780754-656159.

- ^ Stokesbury, James L. (1980). A Short History of WWII. New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc. p. 171. 0-688-03587-6.

- ^ http://www.ibiblio.org/pha/policy/1941/411226a.html

- ^ "Books About Winston Churchill". Chartwell Booksellers. Retrieved 2007-02-26.

- ^ Michael R. Beschloss, (2002) ‘’The Conquerors’’ : pg. 131

- ^ Stokesbury, James L. (1980). A Short History of WWII. New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc. p. 159. 0-688-03587-6.

- ^ Jenkins, Roy (2001). Churchill. London: Macmillan. pp. 759–760. 0-333-78290-9.

- ^ Historical Papers: Documents from the British Archives

- ^ Churchill, Winstons (1953). The Second World War: Volume 6 - Triumph and Tragedy.

- ^ Taylor, Frederick; Dresden: Tuesday, February 13, 1945; US review, NY: HarperCollins, ISBN 0-06-000676-5; UK review, London: Bloomsbury, ISBN 0-7475-7078-7. pp. 262–4. There were an unknown number of refugees in Dresden, so the historians Matthias Neutzner, Götz Bergander and Frederick Taylor have used historical sources and deductive reasoning to estimate that the number of refugees in the city and surrounding suburbs was around 200,000 or less on the first night of the bombing.

- ^ Picknett, et al., p. 190.

- ^ "Remembrance Day 2003". Churchill Society London. Retrieved 2007-04-25.

- ^ a b Churchill, Winston. "Sinews of Peace (Iron Curtain)". Churchill Centre. Retrieved 2007-02-26.

- ^ Hennessy, p. 205

- ^ Black Dog, PBS.

- ^ "Winston Churchill's painting sold for a record million pounds". AndhraNews.net.

- ^ Richards, Michael. "Alcohol Abuser". Churchill Centre. Retrieved 2007-02-26.

- ^ Montague Brown, p. 213

- ^ Freedom of Information Act document, Department of State of the USA.

- ^ Picknett, et al., p. 252.

- ^ Fischer, Raymond (2005-02-04). "Letter: Hero of Waterloo". The Independent. Retrieved 2007-02-26.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ "Sir Winston Churchill's Funeral Train". Southern E-Group. Retrieved 2007-02-26.

- ^ "New grave honours Churchill". BBC News Online. 1998-05-08. Retrieved 2007-02-26.

- ^ Poll of the 100 Greatest Britons

Primary sources

- Churchill, Winston. The World Crisis (six volumes, 1923–31), 1-vol edition (2005); on World War I

- Churchill, Winston. The Second World War (six volumes, 1948–53)

- Gilbert, Martin, ed. Winston S. Churchill: Companion 15 vol (14,000 pages) of Churchill and other official and unofficial documents. Part 1: I. Youth, 1874-1900, 1966, 654 pp. (2 vol); II. Young Statesman, 1901-1914, 1967, 796 pp. (3 vol); III. The Challenge of War, 1914-1916, 1971, 1024 pp. (3 vol); IV. The Stricken World, 1916-1922, 1975, 984 pp. (2 vol); Part 2: The Prophet of Truth, 1923-1939, 1977, 1195 pp. (3 vol); II. Finest Hour, 1939-1941, 1983, 1328 pp. (2 vol entitled The Churchill War Papers); III. Road to Victory, 1941-1945, 1986, 1437 pp. (not published, 4 volumes are anticipated); IV. Never Despair, 1945-1965, 1988, 1438 pp. (not published, 3 volumes anticipated). See the editor's memoir, Martin Gilbert, In Search of Churchill: A Historian's Journey, (1994).

- James, Robert Rhodes, ed. Winston S. Churchill: His Complete Speeches, 1897-1963. 8 vols. London: Chelsea, 1974, 8917 pp.

- Sir Winston Churchill, His life through his paintings, David Coombs, Pegasus, 2003

- Quotations database, World Beyond Borders.

- The Oxford Dictionary of 20th century Quotations by Oxford University Press (ISBN 0-19-860103-4)

Secondary sources

- Michael R. Beschloss, (2002) The Conquerors: Roosevelt, Truman and the Destruction of Hitler's Germany, 1941-1945 pg. 131.

- Geoffrey Best. Churchill: A Study in Greatness (2003)

- Blake, Robert. Winston Churchill. Pocket Biographies (1997), 110 pages

- Blake, Robert and Louis William Roger, eds. Churchill: A Major New Reassessment of His Life in Peace and War Oxford UP, 1992, 581 pp; 29 essays by scholars

- John Charmley, Churchill, The End of Glory: A Political Biography (1993). revisionist; favors Chamberlain; says Churchill weakened Britain

- John Charmley. Churchill's Grand Alliance: The Anglo-American Special Relationship 1940-57 (1996)

- Richard Harding Davis, Real Soldiers of Fortune 1906, early biography. Project Gutenberg etext

- Martin Gilbert Churchill: A Life (1992) (ISBN 0-8050-2396-8); one volume version of 8-volume life (8900 pp); amazing detail but as Rasor complains, "no background, no context, no comment, no analysis, no judgments, no evaluation, and no insights."

- Sebastian Haffner, Winston Churchill 1967

- P. Hennessy, Prime minister: the office and its holders since 1945 2001

- Christopher Hitchens, "The Medals of His Defeats," The Atlantic April 2002.

- James, Robert Rhodes. Churchill: A Study in Failure, 1900-1939 (1970), 400 pp.

- Roy Jenkins. Churchill: A Biography (2001)

- François Kersaudy, Churchill and De Gaulle 1981 ISBN 0-00-216328-4.

- Christian Krockow, Churchill: Man of the Century by 2000 ISBN 1-902809-43-2.

- John Lukacs. Churchill : Visionary, Statesman, Historian Yale University Press, 2002.

- William Manchester, The Last Lion: Winston Spencer Churchill, Visions of Glory 1874-1932, 1983; ISBN 0-316-54503-1; The Last Lion: Winston Spencer Churchill, Alone 1932-1940, 1988, ISBN 0-316-54512-0; no more published

- Robert Massie Dreadnought: Britain, Germany and the Coming of the Great War (ISBN 1-84413-528-4); ch 40-41 on Churchill at Admiralty

- A. Montague Browne, Long sunset 1995

- Henry Pelling, Winston Churchill (first issue) 1974, (ISBN 1-84022-218-2), 736pp; comprehensive biography

- Rasor, Eugene L. Winston S. Churchill, 1874-1965: A Comprehensive Historiography and Annotated Bibliography. Greenwood Press. 2000. 710 pp. describes several thousand books and scholarly articles.

- Stansky, Peter, ed. Churchill: A Profile 1973, 270 pp. essays for and against Churchill by leading scholars

External links

- Works by Winston Churchill at Project Gutenberg

- Winston Churchill Memorial and Library at Westminster College, Missouri

- Churchill College Biography of Winston Churchill

- Books written by Churchill

- Imperial War Museum: Churchill Museum and Cabinet War Rooms. Comprising the original underground War Rooms perfectly preserved since 1945, from which Churchill ran the War, including the Cabinet Room, the Map Room and Churchill's bedroom, and the new Museum dedicated to Churchill's life.

- Collected Churchill Podcasts and speeches

- The Churchill Centre website

- Churchill and the Great Republic. Exhibition explores Churchill's lifelong relationship with the United States.

- Churchill and Zionism (by Dr. Yoav Tenenbaum, Tel Aviv University)

- Winston Churchill and the Bombing of Dresden UK National Archives documents.

- War Cabinet Minutes (1942 - 42), (1942 - 43), (1945 - 46), (1946 - 46)

- MCE European NAvigator European Union History tool, contains a number of Churchill recordings etc.

- The Real Churchill (critical) and a rebuttal

- A Rebuttal to "The Real Churchill

- Essay: Churchill and the Crucible of History

- Winston Churchill and Manic Depression

- More about Winston Churchill on the Downing Street website.

Speeches

Offices