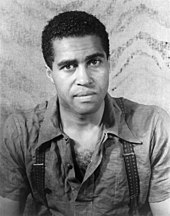

James Earl Jones

James Earl Jones | |

|---|---|

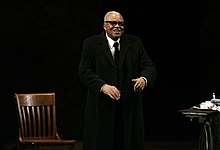

Jones in 2013 | |

| Born | January 17, 1931 Arkabutla, Mississippi, U.S. |

| Alma mater | University of Michigan (BA) |

| Occupation | Actor |

| Years active | 1953–present |

| Works | Full list |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 1 |

| Father | Robert Earl Jones |

| Awards | Full list |

James Earl Jones (born January 17, 1931) is an American actor. He has been described as "one of America's most distinguished and versatile" actors for his performances on stage and screen,[1] and "one of the greatest actors in American history".[2] His deep voice has been praised as a "a stirring basso profondo that has lent gravel and gravitas" to his projects.[3][4] Over his career, he has received three Tony Awards, two Emmy Awards, and a Grammy Award. He was inducted into the American Theater Hall of Fame in 1985. He was honored with the National Medal of Arts in 1992, the Kennedy Center Honor in 2002, the Screen Actors Guild Life Achievement Award in 2009 and the Honorary Academy Award in 2011.[5][2]

Suffering from a stutter in childhood, Jones has said that poetry and acting helped him overcome the disability. A pre-med major in college, he served in the United States Army during the Korean War before pursuing a career in acting. Since his Broadway debut in 1957, he has performed in several Shakespeare plays including Othello, Hamlet, Coriolanus, and King Lear.[6] Jones worked steadily in theater winning his first Tony Award in 1968 for his role in The Great White Hope, which he reprised in the 1970 film adaptation earning him Academy Award and Golden Globe nominations.

Jones won his second Tony Award in 1987 for his role in August Wilson's Fences. He was further Tony nominated for his roles in On Golden Pond (2005), and The Best Man (2012). Other Broadway performances include Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (2008), Driving Miss Daisy (2010–2011), You Can't Take It with You (2014), and The Gin Game (2015–2016). He received a Special Tony Award for Lifetime Achievement in 2017.[7][8]

Jones made his film debut in Stanley Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove (1964). He received a Golden Globe Award nomination for Claudine (1974). Jones gained international fame for his voice role as Darth Vader in the Star Wars franchise, beginning with the original 1977 film. Jones' other notable roles include in Conan the Barbarian (1982), Matewan (1987), Coming to America (1988), Field of Dreams (1989), The Hunt for Red October (1990), The Sandlot (1993), and The Lion King (1994). Jones has reprised his roles in Star Wars media, The Lion King (2019), and Coming 2 America (2021).

Early life and education

James Earl Jones was born in Arkabutla, Mississippi, on January 17, 1931,[citation needed] to Ruth (née Connolly); (1911–1986), a teacher and maid, and Robert Earl Jones (1910–2006), a boxer, butler and chauffeur. His father left the family shortly after James Earl's birth and later became a stage and screen actor in New York and Hollywood.[9] Jones and his father did not get to know each other until the 1950s, when they reconciled. He has said in interviews that his parents were both of mixed African-American, Irish and Native American ancestry.[10][11] His great grandfather's mother was Parthenia Connolly; who is a 3rd great grandchild of Rob Roy MacGregor on her mothers side [12]

From the age of five, Jones was raised by his maternal grandparents, John Henry and Maggie Connolly,[citation needed] on their farm in Jackson, Michigan; they had moved from Mississippi in the Great Migration.[13] Jones found the transition to living with his grandparents in Michigan traumatic and developed a stutter so severe that he refused to speak. "I was a stutterer. I couldn't talk. So my first year of school was my first mute year, and then those mute years continued until I got to high school."[13] He credits his English teacher, Donald Crouch, who discovered he had a gift for writing poetry, with helping him end his silence.[9] Crouch urged him to challenge his reluctance to speak through reading poetry aloud to the class.[14][15]

In 1949, Jones graduated from Dickson Rural Agricultural School[16] (now Brethren High School) in Brethren, Michigan, where he served as vice president of his class.[17] He attended the University of Michigan, where he was initially a pre-med major.[9] He joined the Reserve Officers' Training Corps and excelled. He felt comfortable within the structure of the military environment and enjoyed the camaraderie of his fellow cadets in the Pershing Rifles Drill Team and Scabbard and Blade Honor Society.[18] During the course of his studies, Jones discovered he was not cut out to be a physician.[citation needed]

Instead, he focused on drama at the University of Michigan with the thought of doing something he enjoyed, before, he assumed, he would have to go off to fight in the Korean War. After four years of college, Jones graduated from the university in 1955 with a Bachelor of Arts with a major in drama.[19][20]

Military service

With the war intensifying in Korea, Jones expected to be deployed as soon as he received his commission as a second lieutenant. As he waited for his orders, he worked on the stage crew and acted at the Ramsdell Theatre in Manistee, Michigan.[21] Jones was commissioned in mid-1953, after the Korean War's end, and reported to Fort Moore to attend the Infantry Officers Basic Course. He attended Ranger School and received his Ranger Tab. Jones was assigned to Headquarter and Headquarters Company, 38th Regimental Combat Team.[22] He was initially to report to Fort Leonard Wood, but his unit was instead sent to establish a cold-weather training command at the former Camp Hale near Leadville, Colorado. His battalion became a training unit in the rugged terrain of the Rocky Mountains. Jones was promoted to first lieutenant prior to his discharge.[23]

Jones moved to New York, where he studied at the American Theatre Wing and worked as a janitor to support himself.[24][25]

Career

| External audio | |

|---|---|

1953–1973: Early roles and acclaim

Jones began his acting career at the Ramsdell Theatre in Manistee, Michigan. In 1953, he was a stage carpenter, and between 1955 and 1957, he acted and was a stage manager. In his first acting season at the Ramsdell, he portrayed Othello.[27] His early career also included an appearance in the ABC radio anthology series Theatre-Five.[28] In 1957, he made his Broadway debut as understudy to Lloyd Richards in the short-lived play The Egghead by Molly Kazan.[29] The play ran only 21 performances,[30] however three months later, Jones created the featured role of Edward the butler in Dore Schary's Sunrise at Campobello at the Cort Theatre in January 1958.[31]

During the early to mid 1960s, Jones acted in various works of William Shakespeare, becoming one of the best known Shakespearean actors of the time. He tackled roles such as Othello and King Lear, Oberon in A Midsummer Night's Dream, Abhorson in Measure for Measure, and Claudius in Hamlet. Also during this time, Jones made his film debut in Stanley Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964) as the young Lt. Lothar Zogg, the B-52 bombardier. Jones would later play a surgeon and Haitian rebel leader in The Comedians, alongside Richard Burton, Elizabeth Taylor and Alec Guinness.

In December 1967, Jones starred alongside Jane Alexander in Howard Sackler's play The Great White Hope at the Arena Stage in Washington, D.C. Jones took the role of the talented but troubled boxer "Jack Jefferson," who is based on the real champion Jack Johnson. The play was a huge success when it moved to Broadway on October 3, 1968. The play was well received, winning the Pulitzer Prize for Drama. Jones himself won the 1969 Tony Award for Best Actor in a Play, and the Drama Desk Award for his performance.[32]

In 1969, Jones participated in making test films for the children's education series Sesame Street; these shorts, combined with animated segments, were shown to groups of children to gauge the effectiveness of the then-groundbreaking Sesame Street format. As cited by production notes included in the DVD release Sesame Street: Old School 1969–1974, the short that had the greatest impact with test audiences was one showing bald-headed Jones counting slowly to ten. This and other segments featuring Jones were eventually aired as part of the Sesame Street series itself when it debuted later in 1969 and Jones is often cited as the first celebrity guest on that series, although a segment with Carol Burnett was the first to actually be broadcast.[9] He also appeared on the soap opera Guiding Light.

In 1973, Jones played Hickey on Broadway at the Circle in the Square Theater in a revival of Eugene O'Neill's The Iceman Cometh. Jones played Lennie on Broadway in the 1974 Brooks Atkinson Theatre production of the adaptation of John Steinbeck's novella, Of Mice and Men, with Kevin Conway as George and Pamela Blair as Curley's Wife. That same year he starred in the title role of William Shakespeare's King Lear opposite Paul Sorvino, René Auberjonois and Raul Julia at the New York City Shakespeare Festival in Central Park.[33]

In 1970, Jones reunited with Jane Alexander in the film adaptation of The Great White Hope. This would be Jones' first leading film role. Jones portrayed boxer Jack Johnson, a role he had previously originated on stage. His performance was acclaimed by critics and earned him an Academy Award nomination for Best Actor. He was the second African-American male performer after Sidney Poitier to be nominated for this award.[9] Variety described his performance declaring, "Jones' recreation of his stage role is an eye-riveting experience. The towering rages and unrestrained joys of which his character was capable are portrayed larger than life."[34] In The Man (1972), Jones starred as a senator who unexpectedly becomes the first African-American president of the United States. The film also starred Martin Balsam and Burgess Meredith.

1974–1983: Rise to prominence

In 1974, Jones co-starred with Diahann Carroll in the film Claudine, the story of a woman who raises her six children alone after two failed and two "almost" marriages. The film is a romantic comedy and drama, focusing on systemic racial disparities black families face. It was one of the first major films to tackle themes such as welfare, economic inequality, and the typical marriage of men and women in the African American community during the 1970s. Jones and Carroll received widespread critical acclaim and Golden Globe nominations for their performances. Carroll was also nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actress.

In 1977, Jones made his debut in his iconic voiceover role as Darth Vader in George Lucas' space opera blockbuster film Star Wars: A New Hope, which he would reprise for the sequels The Empire Strikes Back (1980) and Return of the Jedi (1983). Darth Vader was portrayed in costume by David Prowse in the film trilogy, with Jones dubbing Vader's dialogue in postproduction because Prowse's strong West Country accent was deemed unsuitable for the role by director George Lucas.[35] At his own request, Jones was uncredited for the release of the first two Star Wars films,[36] though he would be credited for the third film and eventually also for the first film's 1997 "Special Edition" re-release.[37] As he explained in a 2008 interview:

When Linda Blair did the girl in The Exorcist, they hired Mercedes McCambridge to do the voice of the devil coming out of her. And there was controversy as to whether Mercedes should get credit. I was one who thought no, she was just special effects. So when it came to Darth Vader, I said, no, I'm just special effects. But it became so identified that by the third one, I thought, OK I'll let them put my name on it.[36]

In 1977, Jones also received a Grammy Award for Best Spoken Word Album for Great American Documents. In late 1979, Jones appeared on the short-lived CBS police drama Paris, which was notable as the first program on which Steven Bochco served as executive producer. Jones also starred that year in the critically acclaimed TV mini-series sequel Roots: The Next Generations as the older version of author Alex Haley.[9]

1985–1999: Established career

In 1987, Jones starred in August Wilson's play Fences as Troy Maxson, a middle aged working class father who struggles to provide for his family. The play, set in the 1950s, is part of Wilson's ten-part "Pittsburgh Cycle". The play explores the evolving African American experience and examines race relations, among other themes. Jones won widespread critical acclaim, earning himself his second Tony Award for Best Actor in a Play. Beside the Star Wars sequels, Jones was featured in several other box office hits of the 1980s: the action/fantasy film Conan the Barbarian (1982), the Eddie Murphy comedy Coming to America (1988), and the sports drama/fantasy Field of Dreams (1989) which earned an Academy Award for Best Picture nomination. He also starred in the independent film Matewan (1987). The film dramatized the events of the Battle of Matewan, a coal miners' strike in 1920 in Matewan, a small town in the hills of West Virginia. He received an Independent Spirit Award nomination for his performance.

In 1985, Jones lent his bass voice as Pharaoh in the first episode of Hanna-Barbera's The Greatest Adventure: Stories from the Bible. From 1989 to 1992, Jones served as the host of the children's TV series Long Ago and Far Away. Jones appeared in several more successful films during the early-to-mid 1990s, including The Hunt for Red October (1990), Patriot Games (1992), The Sandlot (1993), Clear and Present Danger (1994), and Cry, the Beloved Country (1995). He also lent his distinctive bass voice to the role of Mufasa in the 1994 Disney animated film The Lion King. In 1992, Jones was presented with the National Medal of the Arts by President George H. W. Bush. Jones has the distinction of winning two Primetime Emmys[38] in the same year, in 1991 as Best Actor for his role in Gabriel's Fire and as Best Supporting Actor for his work in Heat Wave.[1]

He has played lead characters on television in three series. The second show aired on ABC between 1990 and 1992, the first season being titled Gabriel's Fire and the second (after a format revision) Pros and Cons. In both formats of that show, Jones played a former policeman wrongly convicted of murder who, upon his release from prison, became a private eye. In 1995, Jones starred in Under One Roof as Neb Langston, a widowed African-American police officer sharing his home in Seattle with his daughter, his married son with his children, and Neb's newly adopted son. The show was a mid-season replacement and lasted only six weeks, but earned him another Emmy nomination. He also portrayed Thad Green on "Mathnet", a parody of Dragnet that appeared in the PBS program Square One Television. In 1998, Jones starred in the widely acclaimed syndicated program An American Moment (created by James R. Kirk and Ninth Wave Productions). Jones took over the role left by Charles Kuralt, upon Kuralt's death.

Jones has guest starred in many television shows over the years, including for NBC's Law & Order, Frasier, and Will & Grace, and ABC's Lois & Clark: The New Adventures of Superman. In 1990, Jones performed voice work for The Simpsons first "Treehouse of Horror" Halloween special, in which he was the narrator for the Simpsons' version of Edgar Allan Poe's poem "The Raven". He also voiced the Emperor of the Night in Pinocchio and the Emperor of the Night and Ommadon in Flight of Dragons.

On July 13, 1993, accompanied by the Morgan State University choir, Jones spoke the U.S. National Anthem before the 1993 Major League Baseball All-Star Game in Baltimore.[39][40] In 1996, he recited the classic baseball poem "Casey at the Bat" with the Cincinnati Pops Orchestra,[41] and in 2007 before a Philadelphia Phillies home game on June 1, 2007.[42] On August 20, 1999, Command & Conquer: Tiberian Sun released starring Jones as a lead character known as General Solomon. Further mentions of General Solomon continue throughout the series, indicating praise for James' outstanding work in the game.

2000–2009

During the 2000s Jones made appearances on various television shows such as CBS' Two and a Half Men, the WB drama Everwood, Fox's medical drama House, M.D., and CBS' The Big Bang Theory.[43][44]

In 2002, Jones received Kennedy Center Honors at the John F. Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C.. Also at the ceremony included fellow honorees Paul Simon, Elizabeth Taylor, and Chita Rivera. President George W. Bush joked, "People say that the voice of the president is the most easily recognized voice in America. Well, I'm not going to make that claim in the presence of James Earl Jones."[45] Those there to honor Jones included, Sidney Poitier, Kelsey Grammer, Charles S. Dutton, and Courtney B. Vance.

He also has done the CNN tagline, "This is CNN", as well as "This is CNN International", and the opening for CNN's morning show New Day. Jones was also a longtime spokesman for Bell Atlantic and later Verizon. He also lent his voice to the opening for NBC's coverage of the 2000 and 2004 Summer Olympics; "the Big PI in the Sky" (God) in the computer game Under a Killing Moon; a Claymation film, The Creation; and several other guest spots on The Simpsons. Jones narrated all 27 books of the New Testament in the audiobook James Earl Jones Reads the Bible.[46] Although uncredited, Jones' voice is possibly heard as Darth Vader at the conclusion of Star Wars: Episode III – Revenge of the Sith (2005). When specifically asked whether he had supplied the voice, possibly from a previous recording, Jones told Newsday: "You'd have to ask Lucas about that. I don't know."[36] On April 7, 2005, Jones and Leslie Uggams headed the cast in an African-American Broadway revival version of On Golden Pond, directed by Leonard Foglia and produced by Jeffrey Finn.[9] In February 2008, he starred on Broadway as Big Daddy in a limited-run, all-African-American production of Tennessee Williams' Pulitzer Prize-winning drama Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, directed by Debbie Allen and mounted at the Broadhurst Theatre. In November 2009, James reprised the role of Big Daddy in Cat On A Hot Tin Roof at the Novello Theatre in London's West End. This production also stars Sanaa Lathan as Maggie, Phylicia Rashad as Big Mamma, and Adrian Lester as Brick. In 2009, Jones appeared as a patient in the fourth episode of the sixth season of the medical drama House M.D. Also in 2009, for his work on film and television, Jones was presented with the Screen Actors Guild Life Achievement Award by Forest Whitaker.

2010–present

In October 2010, Jones returned to the Broadway stage in Alfred Uhry's Driving Miss Daisy, along with Vanessa Redgrave at the Golden Theatre.[47] In November 2011, Jones starred in Driving Miss Daisy in London's West End, and on November 12 received an honorary Oscar in front of the audience at the Wyndham's Theatre, which was presented to him by Ben Kingsley.[48] In March 2012, Jones played the role of President Art Hockstader in Gore Vidal's The Best Man on Broadway at the Schoenfeld Theatre: he was nominated for a Tony for Best Performance in a Lead Role in a Revival. The play also starred Angela Lansbury, John Larroquette (as candidate William Russell), Candice Bergen, Eric McCormack (as candidate Senator Joseph Cantwell), Jefferson Mays, Michael McKean, and Kerry Butler, with direction by Michael Wilson.[49][50]

In 2013, Jones starred opposite Vanessa Redgrave in a production of Much Ado About Nothing directed by Mark Rylance at The Old Vic, London.[51] From February to June 2013, Jones starred alongside Dame Angela Lansbury in an Australian tour of Driving Miss Daisy.[52] In 2014, Jones starred alongside Annaleigh Ashford as Grandpa in the Broadway revival of the George S. Kaufman comedic play You Can't Take It with You at the Longacre Theatre, Broadway. Ashford received a Tony Award for Best Featured Actress in a Play nomination for her performance. On September 23, 2015, Jones opened in a new revival of The Gin Game opposite Cicely Tyson, in the John Golden Theater, where the play had originally premiered (with Hume Cronyn and Jessica Tandy). The play had a planned limited run of 16 weeks.[53] It closed on January 10, 2016.

In 2013–2014, he appeared alongside Malcolm McDowell in a series of commercials for Sprint in which the two dramatically recited mundane phone and text-message conversations.[54][55] In 2015, Jones starred as the Chief Justice Caleb Thorne in the American drama series Agent X alongside actress Sharon Stone, Jeff Hephner, Jamey Sheridan, and others. The television series was aired by TNT from November 8 to December 27, 2015, running only one season and 10 episodes. Jones officially reprised his voice role of Darth Vader for the character's appearances in the animated TV series Star Wars Rebels[56][57] and the live-action film Rogue One: A Star Wars Story (2016),[58][59] as well as for a three-word cameo in Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker (2019).[60]

In 2019, he reprised his voice role of Mufasa for the CGI remake of The Lion King, directed by Jon Favreau, in which he was the only original cast member to do so.[61][62] According to Favreau, Jones' lines remained mostly the same from the original film.[63][64] Chiwetel Ejiofor, who voiced Mufasa's evil brother Scar in the remake, said that "the comfort of [Jones reprising his role] is going to be very rewarding in taking [the audience] on this journey again. It's a once-in-a-generation vocal quality."[63] Jones reprised the role of King Jaffe Joffer in Coming 2 America (2021), the sequel to Coming to America (1988).[65] In 2022, his voice was used via Respeecher software for Darth Vader in the Disney+ miniseries Obi-Wan Kenobi.[66] During production, Jones signed a deal with Lucasfilm authorizing archival recordings of his voice to be used in the future to artificially generate the voice of Darth Vader.[67] In September 2022, Jones announced that he would retire from the role of voicing Darth Vader with future voice roles for Vader being created with AI voice software using archive audio of Jones.[68]

Personal life

In 1968, Jones married actress and singer Julienne Marie, whom he met while performing as Othello in 1964.[69] They had no children and divorced in 1972.[70] In 1982, he married actress Cecilia Hart, with whom he had a son, Flynn (b. 1982).[71][72] Hart died from ovarian cancer on October 16, 2016.[73]

In April 2016, Jones spoke publicly for the first time in nearly 20 years about his long-term health challenge with type 2 diabetes. He was diagnosed in the mid-1990s after his doctor noticed he had fallen asleep while exercising at a gym.[74]

Jones is Catholic, having converted during his time in the military.[75]

Filmography

Jones has had an extensive career in film, television, and theater. He started out in film by appearing in the 1964 political satire film Dr. Strangelove as Lt. Lothar Zogg. He then went on to star in the 1970 film The Great White Hope as Jack Jefferson, a role he first played in the Broadway production of the same name.

Jones' television work includes playing Woodrow Paris in the series Paris between 1979 and 1980. He voiced various characters on the animated series The Simpsons in three separate seasons (1990, 1994, 1998).

Jones' theater work includes numerous Broadway plays, including Sunrise at Campobello (1958–1959), Danton's Death (1965), The Iceman Cometh (1973–1974), Of Mice and Men (1974–1975), Othello (1982), On Golden Pond (2005), Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (2008) and You Can't Take It with You (2014–2015).

Awards and honors

Jones has received two Primetime Emmy Awards, two Tony Awards, and a Grammy Award. He also is the recipient of a Golden Globe Award and the Screen Actors Guild Life Achievement Award. In 2011, he received an Academy Honorary Award.[76] As such, he is a recipient of the EGOT (Emmy, Grammy, Oscar, Tony).[77]

In 1985, Jones was inducted into the American Theater Hall of Fame[78][79] He was also the 1987 First recipient of the National Association for Hearing and Speech Action's Annie Glenn Award.[80] In 1991, he received the Common Wealth Award for Outstanding Achievement in the Dramatic Arts. In 1992, he was awarded the National Medal of Arts by George H. W. Bush. He received the 1996 Golden Palm Star on the Palm Springs, California, Walk of Stars.[81] Also in 1996, he was given the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement presented by Awards Council member George Lucas.[82][83] In 2002, he was the featured Martin Luther King Day speaker for Lauderhill, Florida.[84] In 2011, he received the Eugene O'Neill Theater Center Monte Cristo Award Recipient.[85] He was the 2012 Marian Anderson Award Recipient.[86][87] Jones won the 2014 Voice Icon Award sponsored by Society of Voice Arts and Sciences at the Museum of the Moving Image. In 2017, he received an Honorary Doctor of Arts from Harvard University.[88] In 2019, he was honored as a Disney Legend.[89] In March 2022, Broadway's Cort Theatre was renamed the James Earl Jones Theatre.[90][91]

He received an Honorary Academy Award on November 12, 2011.[2] Jones received an Honorary Doctor of Arts degree from Harvard University on May 25, 2017.[92] He was honored with a Special Tony Award for Lifetime Achievement in 2017.[93] On September 12, 2022, the Cort Theatre, a Broadway theater in Manhattan, New York City, was renamed the James Earl Jones Theatre in his honor.

References

- ^ Jump up to: a b Marx, Rebecca Flint. "James Earl Jones Biography". All Movie Guide. Archived from the original on August 6, 2021. Retrieved April 12, 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Sperling, Nicole; Susan King (November 12, 2011). "Oprah shines, Ratner controversy fades at honorary Oscars gala". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 20, 2014. Retrieved November 14, 2011.

- ^ Hornaday, Ann (September 25, 2014). "James Earl Jones: A voice for the ages, aging gracefully". Archived from the original on February 7, 2021. Retrieved August 12, 2016 – via washingtonpost.com.

- ^ Moore, Caitlin (September 25, 2014). "James Earl Jones might have the most recognizable voice in film and television". Archived from the original on August 28, 2016. Retrieved August 12, 2016 – via washingtonpost.com.

- ^ "SAG to honor James Earl Jones". The Hollywood Reporter. October 2, 2008. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- ^ "About James Earl Jones". americantheatrewing.org. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- ^ "Acceptance Speech: James Earl Jones (2017)". Tony Awards. Archived from the original on April 24, 2023. Retrieved April 10, 2023.

- ^ "James Earl Jones Will Receive a Lifetime Achievement Tony Award". Playbill. Archived from the original on November 26, 2022. Retrieved April 10, 2023.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Bandler, Michael J. (March 2008). "This is James Earl Jones". NWA World Traveler. Northwest Airlines. Archived from the original on March 20, 2008. Retrieved April 3, 2008.

- ^ Levesque, Carl (August 1, 2002). "Unconventional wisdom: James Earl Jones speaks out". Association Management. The Gale Group. Archived from the original on November 18, 2017. Retrieved November 18, 2017.

- ^ Davis, Dorothy (February 2005). "Speaking with James Earl Jones". Education Update. Archived from the original on October 20, 2017. Retrieved February 20, 2008.

- ^ "James Earl Jones' Family Tree". www.geni.com. Archived from the original on November 24, 2023. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "James Earl Jones Biography and Interview – Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement. Archived from the original on June 26, 2019. Retrieved April 3, 2019.

- ^ Davies-Cole, Andrew (February 18, 2010). "The daddy of them all". Herald Scotland. Archived from the original on August 11, 2011. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ^ Wilkerson, Isabel. "The Long-Lasting Legacy of the Great Migration". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on February 15, 2020. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

- ^ Jones, James Earl; Niven, Penelope (2002). Voices and Silences: With a New Epilogue. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 68. ISBN 9780879109691. Archived from the original on April 5, 2023. Retrieved April 5, 2023.

- ^ "James Earl Jones". The History Makers. thehistorymakers.org. Archived from the original on February 3, 2023. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ^ Ensian (Yearbook of the University of Michigan), p. 156 (1952).

- ^ "Notable Alumni". University of Michigan. Archived from the original on February 26, 2012. Retrieved February 27, 2012.

- ^ "James Earl Jones | Biography, Plays, & Movies | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Archived from the original on February 3, 2023. Retrieved February 2, 2023.

- ^ Jones, James Earl; Niven, Penelope (2006) [2002]. Voices and Silences: With a New Epilogue (2nd ed.). Limelight Editions. p. 82. ISBN 9780879109691. Archived from the original on March 4, 2023. Retrieved April 6, 2023.

- ^ "Shadow box". Archived from the original on February 3, 2021. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- ^ "Soldiers to Celebrities: James Earl Jones – U.S. Army". Hollywood Hired Guns. Hired Guns Productions. January 20, 2008. Archived from the original on December 27, 2008. Retrieved February 20, 2008.

- ^ "About James Earl Jones". americantheatrewing.org. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

- ^ "James Earl Jones: From Stutterer To Janitor To Broadway Star". NPR. Archived from the original on February 3, 2023. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

- ^ "James Earl Jones talks with Studs Terkel on WFMT; 1968/02". Studs Terkel Radio Archive. February 1, 1968. Archived from the original on September 25, 2020.

- ^ "Ramsdell Theatre History". Ramsdell-theater.org. Archived from the original on January 4, 2009. Retrieved March 1, 2011.

- ^ "Theater Five – Single Episodes". Internet Archive. January 15, 2007.

- ^ "James Earl Jones – Broadway Cast & Staff | IBDB". IBDB. Archived from the original on April 29, 2021. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ League, The Broadway. "The Egghead – Broadway Play – Original | IBDB". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ League, The Broadway. "Sunrise at Campobello – Broadway Play – Original | IBDB". IBDB. Archived from the original on April 27, 2021. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ "The Great White Hope". Internet Broadway Database. Archived from the original on March 6, 2009. Retrieved July 10, 2009.

- ^ "Shakespeare's King Lear. James Earl Jones, NYC Shakespeare Festival, 1974". Youtube. Archived from the original on February 3, 2023. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ "The Great White Hope". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on February 3, 2023. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ "The Green force". BBC News. February 14, 2006. Archived from the original on May 12, 2009. Retrieved March 1, 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Lovece, Frank (March 12, 2008). "Fast Chat: James Earl Jones". Newsday. New York City. Archived from the original on December 4, 2009. Retrieved March 1, 2011.

- ^ Sragow, Michael (February 6, 1997). "Isn't That Spacial? Back to the future with 'Star Wars: The Special Edition'". Phoenix New Times. Phoenix, Arizona. Archived from the original on January 31, 2015. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- ^ James Earl Jones – Awards & Nominations Archived September 28, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Television Academy.

- ^ "James Earl Jones Recites National Anthem at the 1993 All Star game". You Tube. Major League Baseball. Archived from the original on December 21, 2021. Retrieved February 18, 2019.

- ^ Luke, Bob (January 14, 2016). Integrating the Orioles: Baseball and Race in Baltimore. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, Inc. ISBN 978-1-4766-6212-1.

- ^ Drayer, Shannon (June 3, 2013). "Audio treasure: Dave Niehaus reads 'Casey at the Bat'". KTTH / 710 ESPN Seattle. Archived from the original on September 20, 2014. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

James Earl Jones more than did the piece justice in a recording with the Cincinnati Pops in 1996...

- ^ "Actor James Earl Jones smiles before reading..." Townhall.com. Reuters. Archived from the original on January 31, 2015. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- ^ Schedeen, Jesse (January 31, 2014). "The Big Bang Theory: "The Convention Conundrum" Review". IGN. Archived from the original on July 11, 2020. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ^ Hughes, Jason (January 31, 2014). "James Earl Jones Is Hilarious On 'The Big Bang Theory'". HuffPost. Archived from the original on July 13, 2020. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ^ "KENNEDY CENTER TOASTS PAUL SIMON, LIZ TAYLOR, JAMES EARL JONES". Hartford Courant.com. December 27, 2002. Archived from the original on September 20, 2020. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- ^ "James Earl Jones Reads The New Testament – Digital Edition". Archived from the original on June 27, 2014.

- ^ "James Earl Jones and Vanessa Redgrave to Star in Broadway's Driving Miss Daisy". Playbill. Archived from the original on August 3, 2010. Retrieved March 1, 2011.

- ^ "Actor James Earl Jones receives Oscar in London" Archived January 27, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, BBC News. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ "Gore Vidal's The Best Man" Archived January 17, 2013, at the Wayback Machine at IBDB.

- ^ Gans, Andrew; Jones, Kenneth (May 17, 2012). "'The Best Man', Tony Nominee as Best Revival of a Play, Extends Booking a Second Time". Playbill. London, England: Playbill, Inc. Archived from the original on September 4, 2012.

- ^ Trueman, Matt (December 4, 2012). "Vanessa Redgrave and James Earl Jones to reunite for Old Vic's Much Ado". The Guardian. London, England. Archived from the original on January 26, 2013. Retrieved July 10, 2013.

- ^ Gans, Andrew (July 31, 2012). "Driving Miss Daisy Will Ride Into Australia with James Earl Jones and Angela Lansbury". Playbill. Archived from the original on November 5, 2013. Retrieved January 3, 2016.

- ^ "The Gin Game at John Golden Theater". New York City Theater. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- ^ Tim Nudd, "Inside James Earl Jones and Malcolm McDowell's Dramatic Readings for Sprint" Archived January 1, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, AdWeek, December 16, 2013.

- ^ "Sprint Commercial (2013–2014)". popisms.com. Archived from the original on January 9, 2014. Retrieved January 9, 2014.

- ^ "James Earl Jones to Voice Darth Vader in Star Wars: Rebels' Premiere on ABC!" Archived February 25, 2015, at the Wayback Machine Star Wars Episode VII News, October 9, 2014.

- ^ "James Earl Jones confirmed as Darth Vader" Archived April 22, 2015, at the Wayback Machine Blastr, April 21, 2015.

- ^ Skrebels, Joe (June 23, 2016). "Rogue One's Darth Vader Will Be Played by James Earl Jones and "A Variety of Large-Framed Performers"". Archived from the original on August 2, 2020. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ "James Earl Jones Is The One & Only Darth Vader". Bustle. December 15, 2016. Archived from the original on June 27, 2021. Retrieved December 9, 2020.

- ^ "All Of The Cameos In Star Wars: Rise Of Skywalker". Cinemablend. December 23, 2019. Archived from the original on November 27, 2020. Retrieved December 9, 2020.

- ^ Couch, Aaron (February 17, 2017). "'Lion King' Remake Casts Donald Glover as Simba, James Earl Jones as Mufasa". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on February 18, 2017. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ "The Lion King director recalls James Earl Jones' 'powerful' return as Mufasa". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on April 26, 2019. Retrieved December 9, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "What To Expect From The Characters In The Upcoming 'The Lion King' Adaptation – Entertainment Weekly". Entertainment Weekly/YouTube. April 25, 2019. Archived from the original on December 21, 2021. Retrieved April 29, 2019.

- ^ Snetiker, Marc (April 26, 2019). "The Lion King director recalls James Earl Jones' 'powerful' return as Mufasa". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on April 26, 2019. Retrieved May 2, 2019.

- ^ "James Earl Jones & Paul Bates Returning For 'Coming To America' Sequel, Rick Ross Also Joining". Deadline Hollywood. August 7, 2019. Archived from the original on November 7, 2020. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- ^ Scott, Lyvie (June 1, 2022). "Who Is Voicing Darth Vader In Obi-Wan Kenobi? It's Complicated". /Film. Archived from the original on June 4, 2022. Retrieved June 4, 2022.

- ^ Breznican, Anthony (September 23, 2022). "Darth Vader's Voice Emanated From War-Torn Ukraine". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on September 23, 2022. Retrieved September 23, 2022.

- ^ Bell, BreAnna (September 24, 2022). "James Earl Jones Steps Back From Voicing Darth Vader, Signs Off on Using Archived Recordings to Recreate Voice With A.I." Variety. Archived from the original on February 3, 2023. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

- ^ "As He Readies For His Latest Broadway Return, We Celebrate Over 50 Years of James Earl Jones Onstage". Playbill. London, England: Playbill, Inc. June 8, 2020. Archived from the original on October 19, 2016. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- ^ Jones, James Earl. Oxford University Press. 2009. pp. 53–54. ISBN 9780195167795. Archived from the original on February 3, 2023. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Marlowe, Sam (September 19, 2013). "James Earl Jones: I'll just keep going until I fall over". Metro News. Archived from the original on March 12, 2014. Retrieved March 12, 2014.

- ^ "James Earl Jones Biography: Film Actor, Theater Actor, Television Actor (1931–)". Biography.com (FYI / A&E Networks). Archived from the original on April 2, 2016. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- ^ Barnes, Mike (October 22, 2016). "Cecilia Hart, Actress and Wife of James Earl Jones, Dies at 68". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on October 22, 2016. Retrieved October 22, 2016.

- ^ Firman, Tehrene (January 4, 2018). "James Earl Jones Discusses His Diabetes for the First Time in Two Decades". Good Housekeeping. Archived from the original on June 9, 2020. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ Dudar, Helen (March 22, 1987). "James Earl Jones At Bat". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 19, 2021. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ "Actor James Earl Jones receives Oscar in London". BBC News. November 14, 2011. Archived from the original on June 3, 2021. Retrieved December 9, 2020.

- ^ "Why James Earl Jones' honorary Oscar doesn't get him an EGOT". Los Angeles Times. August 3, 2011. Archived from the original on November 30, 2020. Retrieved December 9, 2020.

- ^ "Broadway's Best". The New York Times. March 5, 1985. Archived from the original on January 23, 2014. Retrieved February 6, 2014.

- ^ "Theater Hall of Fame members". Archived from the original on January 18, 2015. Retrieved February 6, 2014.

- ^ About: "Annie Glenn" Archived May 18, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, John and Annie Glenn Museum.

- ^ Palm Springs Walk of Stars by date dedicated

- ^ "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement. Archived from the original on December 12, 2017. Retrieved April 24, 2019.

- ^ "2004 Summit Highlights Photo". 2004. Archived from the original on September 17, 2020. Retrieved December 8, 2020.

Awards Council member and actor James Earl Jones presents the Academy's Golden Plate Award to Congressman John Lewis during the introductory evening of the 2004 International Achievement Summit in Chicago, Illinois.

- ^ "James Earl Jones vs. James Earl Ray Mix-Up". January 19, 2003. Archived from the original on August 6, 2021. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- ^ Adam Hetrick, "James Earl Jones Receives O'Neill Center's Monte Cristo Award May 9" Archived January 20, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Playbill, May 9, 2011. Retrieved January 20, 2011.

- ^ Carrie Rickey, "Actor James Earl Jones wins Marian Anderson Award" Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Philly.com, June 5, 2012. Retrieved January 20, 2015.

- ^ "James Earl Jones to Receive Philadelphia's 2012 Marian Anderson Award" Archived January 20, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Broadway World, June 5, 2012. Retrieved January 20, 2015.

- ^ "Harvard awards 10 honorary degrees at 366th Commencement" Archived May 25, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Harvard Gazette, May 25, 2017. Retrieved May 30, 2017.

- ^ Abell, Bailee (May 16, 2019). "Robert Downey Jr. and James Earl Jones highlight the list of Disney Legends to be honored at D23 Expo 2019". Inside the Magic. Archived from the original on May 17, 2019. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- ^ Paulson, Michael (March 2, 2022). "Broadway's Cort Theater Will Have a New Name: James Earl Jones". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 3, 2023. Retrieved March 2, 2022.

- ^ "James Earl Jones honored in renaming of historic N.Y. Broadway theater". NBC News. March 2, 2022. Archived from the original on February 3, 2023. Retrieved March 3, 2022.

- ^ "Harvard awards 10 honorary degrees". Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved May 26, 2017.

- ^ "Tony Awards: James Earl Jones to Receive Lifetime Achievement Honor". The Hollywood Reporter. April 27, 2017. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

Further reading

- Ann Hornaday, "James Earl Jones: A Voice for the Ages, Aging Gracefully," Washington Post, September 27, 2014.

- Jones, James Earl, and Penelope Niven. James Earl Jones: Voices and Silences (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1993) ISBN 0-684-19513-5

- Lifetime Honors – National Medal of Arts

External links

- 1931 births

- Living people

- 20th-century American male actors

- 21st-century American male actors

- Academy Honorary Award recipients

- Activists for African-American civil rights

- American Roman Catholics

- African-American Catholics

- African-American male actors

- African-American United States Army personnel

- African Americans in the Korean War

- American male film actors

- American male Shakespearean actors

- American male soap opera actors

- American male stage actors

- American male television actors

- American male video game actors

- American male voice actors

- American people of Irish descent

- American people who self-identify as being of Native American descent

- Audiobook narrators

- Daytime Emmy Award winners

- Disney Legends

- Drama Desk Award winners

- Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- Grammy Award winners

- Male actors from Michigan

- Male actors from Mississippi

- Military personnel from Mississippi

- New Star of the Year (Actor) Golden Globe winners

- Obie Award recipients

- Outstanding Performance by a Lead Actor in a Drama Series Primetime Emmy Award winners

- Outstanding Performance by a Supporting Actor in a Miniseries or Movie Primetime Emmy Award winners

- People from Manistee County, Michigan

- People from Tate County, Mississippi

- People with speech impediment

- Pershing Riflemen

- Special Tony Award recipients

- Tony Award winners

- United States Army officers

- United States National Medal of Arts recipients

- University of Michigan alumni

- Kennedy Center honorees