Modafinil: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 272: | Line 272: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

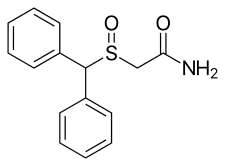

Modafinil is a [[racemic mixture]] of two [[enantiomer]]s, [[armodafinil]] ((''R'')-modafinil) and [[esmodafinil]] ((''S'')-modafinil).<ref name="pmid20307223"/> |

Modafinil is a [[racemic mixture]] of two [[enantiomer]]s, [[armodafinil]] ((''R'')-modafinil) and [[esmodafinil]] ((''S'')-modafinil).<ref name="pmid20307223">{{cite journal |vauthors=Bogan RK |title=Armodafinil in the treatment of excessive sleepiness |journal=Expert Opin Pharmacother |volume=11 |issue=6 |pages=993–1002 |date=April 2010 |pmid=20307223 |doi=10.1517/14656561003705738 |url=}}</ref> |

||

===Detection in body fluids=== |

===Detection in body fluids=== |

||

Revision as of 11:17, 8 December 2023

This article needs more reliable medical references for verification or relies too heavily on primary sources. (December 2023) |  |

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Provigil, Alertec, Modavigil, others |

| Other names | CRL-40476; Diphenylmethyl-sulfinylacetamide |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a602016 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Dependence liability | Relatively low |

| Addiction liability | Very low to low[1][2] |

| Routes of administration | By mouth[3] |

| Drug class | CNS stimulant |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Not determined due to its aqueous insolubility |

| Protein binding | 62.3% |

| Metabolism | Liver (primarily via amide hydrolysis);[8] CYP1A2, CYP2B6, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP3A4, CYP3A5 involved[11] |

| Elimination half-life | 12–15 h[8] (modafinil, the racemic mixture), 15 h (armodafinil, the (R)-enantiomer),[9] 4 h (esmodafinil, the (S)-enantiomer).[10] |

| Excretion | Urine (80%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.168.719 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C15H15NO2S |

| Molar mass | 273.35 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Modafinil, sold under the brand name Provigil among others, is a wakefulness-promoting medication used primarily to treat narcolepsy. It is classified as a eugeroic or wakefulness-promoting drug rather than a classical psychostimulant due to its lack of euphoric effects. Modafinil's unique mechanism of action sets it apart from other stimulants, making it a valuable medication in managing sleep disorders.

Narcolepsy is a neurological disorder characterized by excessive daytime sleepiness and sudden bouts of uncontrollable sleep attacks. People with narcolepsy often struggle to stay awake and alert during the day, impacting their daily activities and overall quality of life. Modafinil has been shown to significantly improve symptoms associated with narcolepsy, allowing individuals to maintain wakefulness and reduce sleep episodes.

Beyond narcolepsy, modafinil has also proven effective in treating other conditions, such as shift work sleep disorder and excessive daytime sleepiness caused by obstructive sleep apnea. In these cases, modafinil helps individuals manage their abnormal sleeping patterns and promotes optimal wakefulness when they need to be alert for work or daily responsibilities.

While modafinil has gained popularity as a cognitive enhancer or "smart drug" among healthy individuals seeking improved focus and productivity, its use outside medical supervision raises concerns regarding potential misuse or abuse. Research on the cognitive enhancement effects of modafinil in non-sleep-deprived individuals has yielded mixed results, with some studies suggesting modest improvements in attention and executive functions while others show no significant benefits or even a decline in cognitive functions.

Usage

Medical

Sleep disorders

Modafinil, a eugeroic or wakefulness-promoting drug, is primarily used for treating narcolepsy, a sleep disorder characterized by excessive daytime sleepiness and sudden sleep attacks.[12] Unlike classical psychostimulants, modafinil does not produce euphoric effects.[13][14]

Narcolepsy causes a strong urge to sleep during the day and can include symptoms like cataplexy, sleep paralysis, and hallucinations. The disorder is linked to a lack of the brain chemical hypocretin (or orexin), primarily produced in the hypothalamus.[15][16]

Modafinil is also prescribed for shift work sleep disorder and excessive daytime sleepiness in obstructive sleep apnea, though it is recommended that patients use continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy before starting modafinil.[17][18][19] For obstructive sleep apnea, modafinil is advised after optimal CPAP therapy use.[20]

Modafinil's use varies by region. In the US, it's approved for adult narcolepsy, shift work sleep disorder, and obstructive sleep apnea, but not for children.[21] In the UK and EU, since 2014, it's approved solely for narcolepsy, including in children, with its use for other conditions restricted by the European Medicines Agency.[22][23]

As of 2023,[update] the French and American Academy of Sleep Medicine strongly recommend modafinil as the first-choice treatment for narcolepsy.[24]

The recommended dose of modafinil for narcolepsy is 200 mg once a day in the morning.[25][21][26]

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK, along with various NGOs focused on multiple sclerosis (MS), endorse the off-label use of modafinil to alleviate fatigue associated with MS.[27][28][21]

MS-related fatigue is a common and often debilitating symptom experienced by many patients. It can significantly impact their daily functioning, quality of life, and ability to perform everyday activities. When prescribed for MS-related fatigue management, modafinil works by promoting wakefulness and increasing alertness without causing drowsiness or disrupting nighttime sleep. Patients often report increased energy levels, reduced feelings of tiredness, improved cognitive function, and an overall improvement in their quality of life when taking modafinil. While modafinil can provide relief from MS-related fatigue symptoms, it does not treat the underlying cause or cure MS itself. The primary goal when using modafinil is symptom management and improving daily functioning. The usual starting dosage of modafinil for MS-related fatigue is typically 200 mg per day. However, healthcare professionals may adjust the dosage based on individual patient needs and response to treatment. Some patients may require higher doses up to 400 mg per day if necessary.[29][30][31]

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Modafinil is occasionally prescribed off-label for individuals with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).[32][33][34] In adults, modafinil is inferior to other treatments such as lisdexamfetamine.[35][36] In children, modafinil is efficient in treating ADHD symptoms.[37][38]

Given its approved status in the US, physicians can legally prescribe modafinil for off-label uses, such as treating ADHD in both children and adults.[39][40][41]

The Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) suggests modafinil as a second-line choice for ADHD, after the first-line choices such as bupropion are exhausted.[42]

Bipolar depression

Modafinil is used off-label as an adjunctive treatment for bipolar depression, which is a depressive phase of bipolar disorder and is characterized by excessive sleepiness and fatigue. Adjunctive treatment with modafinil is an augmentation for the main treatment to increase its effect and is safe and effective especially for patients who do not respond well to standard antidepressants. Modafinil does not increase the risk of mood switch or suicide attempts in patients with bipolar depression, but common adverse effects in bipolar depression are headache, nausea, and insomnia. Modafinil may also have cognitive benefits in patients with bipolar disorder who are in a remission phase.[43][44]

Occupational

Modafinil was utilized by the French Foreign Legion,[45] US Air Force,[46][47][48] and US Marine[49] infantry during the Gulf War to enhance "operational tempo," a term that denotes the speed and intensity at which military operations or activities are executed, aiming to optimize the overall performance and efficiency of the unit.[48][50][51]

Adrafinil, a prodrug of modafinil, was initially tested for narcolepsy in France in 1986. Modafinil, identified as more efficient, was approved by the French Ministry of Defense in 1989 for military use under the name Virgyl. Its adoption aimed to improve unit efficiency in operations, a policy implemented before modafinil's commercial release in 1994.[52] Military personnel were not informed about the nature of the product during these trials.[53] Subsequent studies did not confirm modafinil's benefits in non-sleep-deprived military contexts.[47]

Armed forces in various countries, including the US, UK, India, and France, have considered modafinil as an alternative to traditional amphetamines for managing sleep deprivation in combat or extended missions.[54] The UK's Ministry of Defence and the Indian Air Force have included modafinil in their research and contingency plans.[55][56]

The US military approved modafinil for specific Air Force missions, replacing amphetamines for fatigue management.[57][58] Modafinil is also available to astronauts on the International Space Station to manage fatigue and circadian rhythm disruptions.[59]

The use of modafinil in military contexts without sleep deprivation is not recommended due to inconclusive evidence on its cognitive enhancement benefits and potential risks.[47]

Non-medical

Modafinil has been utilized non-medically as a "smart drug"[60][61] by various groups, including students,[62][63][64] office workers, transhumanists,[65][66] and professionals in various sectors. Its use is attributed by these individuals to its potential for enhancing attention, cognitive capabilities, and alertness.[67][68]

Despite its popularity, modafinil does not significantly enhance cognitive or attentional performance in non-sleep-deprived individuals. In some cases, it has even been associated with impairments in certain cognitive functions.[69][18][70]

Available forms

Modafinil is commercially available in 100 mg and 200 mg oral tablet forms.[17] Additionally, it is offered as the (R)-enantiomer, known as armodafinil, and as a prodrug named adrafinil.[71]

Drug tolerance

Extensive clinical research has not demonstrated drug tolerance, defined as a reduction in response, to modafinil's wakefulness-promoting and anti-fatigue properties, even with therapeutic use extending up to three years. While modafinil is generally well-tolerated, including in pediatric narcolepsy cases, there is evidence that long-term usage can lead to tolerance in some individuals. This necessitates higher doses to maintain the same level of cognitive enhancement or relief from sleepiness. Patients with current or past substance addictions and those with a family history of addiction are particularly at risk for developing tolerance. The mechanisms driving tolerance to modafinil, which may involve its impact on dopamine and norepinephrine levels in the brain, are not fully understood. Repeated administration of modafinil for off-label use such as increased alertness and cognitive-enhancing effects in sleep deprivation can lead to drug tolerance, which means that the effectiveness of the drug may decrease over time. Still, modafinil therapy as a eugeroic agent to treat narcolepsy does not typically lead to drug tolerance, i.e., does not usually decrease on prolonged use, although individual responses may vary.[18][72][73]

Contraindications

Modafinil is contraindicated for individuals with known hypersensitivity to either modafinil or armodafinil.[74]

The US FDA does not endorse modafinil for children's medical conditions due to an increased risk of rare but serious dermatological toxicity.[75][76][77] However, in Europe, modafinil may be prescribed for treating narcolepsy in children.[73]

Due to the limited information available on the excretion of modafinil into breastmilk and its potential effects on infants, breastfeeding mothers using modafinil are advised to be monitored closely, or alternative drugs may be preferred until more safety data emerge.[78]

Modafinil is also contraindicated in certain cardiac conditions, including uncontrolled moderate to severe hypertension, arrhythmia, cor pulmonale, and in cases with signs of CNS stimulant-induced mitral valve prolapse or left ventricular hypertrophy. It is further contraindicated in patients with congenital problems like galactose intolerance, lactase deficiency, or glucose-galactose malabsorption.[79][80]

Adverse effects

Modafinil is generally well-tolerated but can have potential risks and side effects. Common adverse effects, experienced by less than 10% of users, include headaches, nausea, and reduced appetite. Anxiety, insomnia, dizziness, diarrhea, and rhinitis are also reported in 5% to 10% of users.[21] Psychiatric reactions have occurred in individuals with and without a preexisting psychiatric history.[81]

No significant changes in body weight have been observed in clinical trials, although decreased appetite and weight loss have been noted in children and adolescents.[82] Modafinil can cause a slight increase in aminotransferase enzymes, indicative of liver function, but there is no evidence of serious liver damage when levels are within reference ranges.[83]

Rare but serious adverse effects include severe skin rashes and allergy-related symptoms. Between December 1998 and January 2007, the FDA received reports of six cases of severe cutaneous adverse reactions, including erythema multiforme, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and DRESS syndrome. The FDA has issued alerts regarding these risks and also noted reports of angioedema and multi-organ hypersensitivity reactions in postmarketing surveillance.[84][85]

In 2007, the FDA required Cephalon to modify the Provigil leaflet to include warnings about these serious conditions. The long-term safety and effectiveness of modafinil have not been conclusively established.[86] However, a longitudinal study has shown that modafinil and armodafinil are safe and effective in pediatric patients treated for narcolepsy for up to ten years, with no exacerbation of preexisting psychiatric conditions.[87]

An online survey in 2020 found higher levels of illicit drug use and psychiatric diagnoses among modafinil users compared to population-based data, with more frequent use associated with perceived benefits and a tentative link to psychiatric disorders, primarily depression and anxiety.[88]

Addiction and dependence

Modafinil's addiction and dependence liabilities are considered very low.[1][89] Although modafinil shares biochemical mechanisms with stimulant drugs, it is less likely to have mood-elevating properties.[89] The similarities in effects with caffeine are not clearly established.[13][90] It does not produce euphoric effects nor deviate from prescribed dosages.[91] However, caution is advised due to psychoactive effects similar to other CNS stimulants.[21]

The United States Drug Enforcement Administration classified modafinil as a schedule IV controlled substance,[7] and is recognized for having valid medical uses with low addiction potential.[1][39] The International Narcotics Control Board does not classify it as a narcotic or a psychotropic substance.[92][93] Studies suggest modafinil may improve abstinence in cocaine addicts, without notable adverse effects upon discontinuation.[94]

Overdose

An overdose of modafinil can lead to a range of symptoms and complications. Psychiatric symptoms may include psychosis, mania, hallucinations, and suicidal ideation, which can occur even in individuals without a history of mental illness and may persist after discontinuation of the drug.[95] Neurological complications, such as seizures, tremors, dystonia, and dyskinesia, may arise from modafinil's interaction with various neurotransmitter systems.[95] Hepatic toxicity, including elevated liver enzymes, jaundice, and hepatitis, may also occur due to the metabolism of modafinil.[96]

Allergic reactions such as rash, angioedema, anaphylaxis, and Stevens–Johnson syndrome may be triggered by an immunological response to modafinil or its metabolites.[97][98] Cardiovascular complications like hypertension, tachycardia, chest pain, and arrhythmias may also be observed due to modafinil's sympathomimetic action.[95]

In animal studies, the median lethal dose (LD50) of modafinil is approximately 1 mg/kg in mice and rats, and higher in other species. Human clinical trials have involved doses up to 1200 mg/d for 7–21 days. Acute one-time overdoses up to 4500 mg have not been life-threatening but resulted in symptoms like agitation, insomnia, tremor, palpitations, and gastrointestinal disturbances.[17]

The management of modafinil overdose involves supportive care, monitoring of vital signs, and treatment of specific complications. In cases of recent consumption, activated charcoal, gastric lavage, or hemodialysis may be used. There is no specific antidote for modafinil overdose.[95][99][100]

Interactions

Modafinil is known to interact with 463 drugs. These interactions can be classified as major (71), moderate (211), and minor (181).[101]

Some of the drugs that frequently interact with modafinil include Abilify (aripiprazole), Adderall (amphetamine / dextroamphetamine), aspirin, Benadryl (diphenhydramine), and others.[101]

Modafinil is a weak to moderate inducer of CYP3A4[102][103] and a weak inhibitor of CYP2C19, enzymes of the cytochrome P450 group of enzymes.[21] Modafinil also induces or inhibits other cytochrome P450 enzymes. One in vitro study predicts that modafinil may induce the cytochrome P450 enzymes CYP1A2, CYP3A4, and CYP2B6, as well as may inhibit CYP2C9 and CYP2C19.[11] However, other in-vitro studies find no significant inhibition of CYP2C9.[8][104] Modafinil may induce P-glycoprotein, which may affect drugs transported by P-glycoprotein, such as digoxin.[105] Therefore, modafinil affects pharmacodynamics of drugs which are metabolized by CYP3A4 and other enzymes of the cytochrome P450 family.[102]

For instance, induction of CYP3A4 by modafinil affects metabolism of the following medications and endogenous substances:[106]

- opioids, such as methadone, hydrocodone, oxycodone, or fentanyl – modafinil may result in a drop in opioid plasma concentrations because of faster clearance by CYP3A4. If the patient is not monitored closely, reduced efficacy or withdrawal symptoms can occur.[106]

- steroid hormones, such as estradiol, progesterone or cortisol. Modafinil may have an adverse effect on hormonal contraceptives for up to a month after discontinuation.[107] In a 2006 study, a single dose of modafinil 200 mg caused a decrease in blood prolactin levels, although it did not affect human growth hormone or thyroid-stimulating hormone.[108][109] Since modafinil induces the activity of the CYP3A4 enzyme involved in cortisol clearance,[110] modafinil may reduce the bioavailability of hydrocortisone. Therefore, it may be necessary to adjust the steroid substitution dose in subjects receiving CYP3A4-metabolism-inducing drugs such as modafinil.[111]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

| Site | Potency | Type | Species | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAT | 1.8–2.6 μM 4.8 μM 6.4 μM 4.0 μM |

Ki Ki IC50a IC50a |

Human Rat Human Rat |

[112][113] [112] [114][115] [112] |

| NET | >10 μM >92 μM 35.6 μM 136 μM |

Ki Ki IC50a IC50a |

Human Rat Human Rat |

[112][113] [112] [114][115] [112] |

| SERT | >10 μM 46.6 μM >500 μM >50 μM |

Ki Ki IC50a IC50a |

Human Rat Human Rat |

[112][113] [112] [114][115] [112] |

| D2 | >10 μM 16 μMb 120 μMb |

Ki Ki EC50a |

Human Rat Rat |

[112] [116] [116] |

| Footnotes: a = Functional activity, not binding inhibition. b = Armodafinil at D2High. Notes: No activity at a variety of other assessed targets.[112] | ||||

The precise mechanism of action of modafinil for narcolepsy and other sleep disorders remains unknown.[3][117][118][119]

Modafinil's mechanism of action involves various interactions with neurotransmitter systems in the brain. While its exact mode of action is not fully understood, several mechanisms have been proposed.[120][117]

One of the mechanisms is binding of modafinil to the dopamine transporter and inhibiting dopamine reuptake.[117] One significant aspect of modafinil's mechanism is its ability to inhibit the reuptake of dopamine, a neurotransmitter involved in motivation, reward, and wakefulness. Modafinil acts as a weak inhibitor of the dopamine transporter (DAT), which prevents the reabsorption of dopamine into presynaptic neurons. By blocking this reuptake process, modafinil increases extracellular dopamine levels in certain brain regions. Modafinil acts as an atypical, selective, and weak dopamine reuptake inhibitor and indirectly activates the release of orexin neuropeptides and histamine from the lateral hypothalamus and tuberomammillary nucleus, all of which may contribute to heightened arousal.[118][119][121][122] Modafinil has little to no affinity for serotonin or norepinephrine transporters and does not directly interact with these systems. However, studies have shown that elevated concentrations of norepinephrine and serotonin can occur as an indirect effect following modafinil administration due to increased extracellular dopamine activity. Unlike traditional psychostimulant drugs like cocaine or amphetamine, which often induce euphoric effects by directly binding to DATs or increasing synaptic dopamine levels significantly more than modafinal does, modanifl shows low potential for causing euphoria due to differences in how it interacts with DAT at a molecular level.[120][117]

In addition to its influence on dopaminergic pathways, modafinil may impact other neurotransmitter systems such as orexin/hypocretin and histamine. Orexin neurons play a crucial role in promoting wakefulness and regulating arousal states. Modafinil has been postulated to increase signaling within hypothalamic orexin pathways, potentially contributing to its wake-promoting effects. Histamine is another neurotransmitter associated with arousal regulation. Animal studies suggest that modafinil may affect histamine release or receptor activity in specific brain regions involved in sleep-wake control. Furthermore, there are indications that modafinil might have glutamatergic effects based on animal research findings.[21]

Another mechanism is modulating the function of astroglial connexins, specifically connexin 30,[117] which are proteins that facilitate intercellular communication and play a role in sleep-wake regulation.[123][124][125] Connexins form channels that allow the exchange of ions and signaling molecules between cells. In the brain, they are mainly expressed by astrocytes, which help regulate neuronal activity.[126] Modafinil increases the levels of connexin 30 in the cortex, enhancing communication between astrocytes and promoting wakefulness. Conversely, during sleep, connexin 30 levels decrease, contributing to the transition from wakefulness to sleep. Flecainide, a drug that blocks astroglial connexins, can enhance the effects of modafinil on wakefulness and cognition, and reduce narcoleptic episodes in animal models. These findings suggest that modafinil may exert its therapeutic effects by modulating astroglial connexins.[126][117][120]

Modafinil dampens amygdala activity by enhancing the availability and regulation of norepinephrine (NE) in the locus coeruleus (LC). The loss or reduction of hypocretin/orexin neurons in narcolepsy leads to LC dysregulation, which contributes to excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) and cataplexy symptoms. Modafinil increases catecholamines like NE, which helps regulate GABAergic inputs from the amygdala. This increased NE activation of GABA receptors reduces overall excitatory input to the LC, resulting in a decrease in amygdala activity. Consequently, modafinil dampens amygdala activity through its effects on NE neurotransmission within these neural circuits involved in regulating wakefulness and muscle tone during sleep/wake cycles.[127]

Pharmacokinetics

Cmax (peak levels) occurs approximately 2 to 3 hours after modafanil administration. Food slows absorption of modafanil, but does not affect the total AUC. In vitro measurements indicate that 60% of modafinil is bound to plasma proteins at clinical concentrations of the drug. This percentage changes very little when the concentration of modafinil is varied.[128]

Renal excretion of unchanged modafinil usually accounts for less than 10% of an oral dose. This means that when modafinil is taken by mouth, less than 10% of the drug is eliminated from the body through the urine without being metabolized (broken down) by the liver or other organs. The rest of the drug is either metabolized or excreted through other routes, such as feces or bile.[8] The two major circulating metabolites of modafinil are modafinil acid (CRL-40467) and modafinil sulfone (CRL-41056). Both of these metabolites have been described as inactive, and neither appears to contribute to the wakefulness-promoting effects of modafinil.[129][130][8][131] However, modafinil sulfone does appear to possess anticonvulsant effects, a property that it shares with modafinil.[132] Elimination half-life is in the range of 10 to 12 hours, subject to differences in cytochrome P450 genotypes, liver function, and renal function. Modafinil is metabolized mainly in the liver,[8] and its inactive metabolite is excreted in the urine. Urinary excretion of the unchanged drug is usually less than 10%, but can range from 0% to as high as 18.7%, depending on the factors mentioned.[128]

Chemistry

Enantiomers

Modafinil is a racemic mixture of two enantiomers, armodafinil ((R)-modafinil) and esmodafinil ((S)-modafinil).[133]

Detection in body fluids

Modafinil and/or its major metabolite, modafinil acid, may be quantified in plasma, serum, or urine to monitor dosage in those receiving the drug therapeutically, to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized patients, or to assist in the forensic investigation of a vehicular traffic violation. Instrumental techniques involving gas or liquid chromatography are usually employed for these purposes.[134][135] In 2011, modafinil was not tested for by common drug screens (except for anti-doping screens) and is unlikely to cause false positives for other chemically unrelated drugs such as substituted amphetamines.[115]

Reagent testing can screen for the presence of modafinil in samples.[136][137]

| RC | Marquis Reagent | Liebermann | Froehde |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modafinil | Yellow/Orange > Brown[136][137] | Darkening Orange[136] | Deep orange/red[137] |

Structural analogues

Many derivatives and structural analogues of modafinil have been synthesized and studied.[14][138][139] Examples include adrafinil, CE-123, fladrafinil (CRL-40941; fluorafinil), flmodafinil (CRL-40940; bisfluoromodafinil, lauflumide), and modafinil sulfone (CRL-41056).[140]

History

Modafinil was developed in France by neurophysiology professor Michel Jouvet and Lafon Laboratories. It is part of a series of benzhydryl sulfinyl compounds, including adrafinil, initially used as a treatment for narcolepsy in France in 1986.[52] Modafinil, the primary metabolite of adrafinil,[141] has been prescribed in France since 1994 under the name Modiodal,[52] and in the United States since 1998 as Provigil.[142] Unlike modafinil, adrafinil does not have FDA approval and was withdrawn from the French market in 2011.[143]

The US Food and Drug Administration approved modafinil in 1998 for narcolepsy treatment, and later for shift work sleep disorder and obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea in 2003.[7][144] It was approved in the UK in December 2002. In the United States, modafinil is marketed by Cephalon,[145] who acquired the rights from Lafon and purchased the company in 2001.[145]

Cephalon introduced armodafinil, the (R)-enantiomer of modafinil, in the United States in 2007. Generic versions of modafinil became available in the US in 2012 after extensive patent litigation.[146][147]

Society and culture

Legal status

Australia

In Australia, modafinil is considered to be a Schedule 4 prescription-only medicine or prescription animal remedy.[148]

Canada

In Canada, modafinil is not listed in the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, but it is a Schedule F prescription drug.[149]

China

In mainland China, modafinil is strictly controlled like other stimulants such as amphetamines and methylphenidate. It is classified as Class I psychotropic drug, requiring prescription.[150][151]

Moldova

In the Republic of Moldova, modafinil is classified as a psychotropic drug and is available by prescription.[152] Importation of modafinil may be considered illegal and subject to severe penalties.[153] In Transnistria, modafinil is completely prohibited, with possession potentially leading to imprisonment.[154]

Japan

In Japan, modafinil is Schedule I psychotropic drug.[155][156] Cephalon licensed Alfresa Corporation to produce, and Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma to sell modafinil products under the trade name Modiodal in Japan.[157] There have been arrests of people who imported modafinil for personal use.[158][159]

Romania

In Romania, modafinil is classified as a stimulant doping agent and is prohibited in sports competitions.[160] In 2022, laws were passed making its importation or sale a felony, punishable by three to seven years in jail.[161] Simple possession for personal use may result in a fine and confiscation.[161]

Russia

In Russia, starting from May 18, 2012, modafinil is Schedule II controlled substance like cocaine and morphine. Possession of a few modafinil pills can lead to three to ten years imprisonment.[154][162] There are multiple cases of criminal proceedings initiated against Russian residents who tried to import modafinil by mail from abroad.[163][164]

Sweden

In Sweden, modafinil is classified as a schedule IV substance; possession is illegal without prescription.[165]

United States

In the United States, modafinil it is classified as a schedule IV controlled substance under US federal law.[7][166][166][7] It is illegal to import it without a DEA-registered importer and a prescription.[167] Individuals may legally bring modafinil into the US from a foreign country for personal use, limited to 50 dosage units, with a prescription and proper declaration at the border.[168] Under the Pure Food and Drug Act, marketing drugs for off-label uses is prohibited.[169] Cephalon, the manufacturer of Modafinil, faced legal issues for promoting off-label uses and paid significant fines in 2008.[170]

Other countries

The following countries do not classify modafinil as a controlled substance:

- In Finland, modafinil is a prescription drug but not listed as a controlled substance.[171]

- In Denmark, modafinil is a prescription drug but not listed as a controlled substance.[172]

- In Mexico, modafinil is not listed as a controlled substance, in the National Health Law, and can be purchased in pharmacies without prescription.[173]

- In South Africa, it is Schedule V substance.[174]

- In the United Kingdom, it is not listed in Misuse of Drugs Act, so possession is not illegal, but a prescription is required.[175]

Brand names

Modafinil is sold under a variety of brand names worldwide, including Alertec, Alertex, Altasomil, Aspendos, Bravamax, Forcilin, Intensit, Mentix, Modafinil, Modafinilo, Modalert, Modanil, Modasomil, Modvigil, Modiodal, Modiwake, Movigil, Provigil, Resotyl, Stavigile, Vigia, Vigicer, Vigil, Vigimax, Waklert, and Zalux.[176]

Economics

Originally developed in the 1970s by French neuroscientist Michel Jouvet and Lafon Laboratories, Modafinil has been prescribed in France since 1994,[52] and was approved for medical use in the United States in 1998.[17]

In 2020, modafinil was the 302nd most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with just over 1000000 prescriptions.[177]

The global sales figures for modafinil are not known. Still, modafinil sold under the brand name Provigil accounted for over 40% of Cephalon's global turnover for several years, according to the information published in 2020.[178]

Concerns have been raised about the growing use of modafinil as a "smart drug" or cognitive enhancer among healthy individuals who use it to improve concentration and memory. The New York Times reported in 2004 that modafinil sales were skyrocketing, with some experts concerned that it had become a tempting pick-me-up for people looking for an extra edge in a productivity-obsessed society. The cost of modafinil can vary depending on factors such as location and insurance coverage. In 2013, the price was reported to be around $120 or more per monthly supply. However, the availability of generic versions has increased since then and may have driven down prices.[179][180][181]

Patent protection and litigation

Modafinil's patent history involves several key developments. The original patent, U.S. patent 4,927,855, was granted to Laboratoire L. Lafon in 1990, covering the chemical compound of modafinil. This patent expired in 2010.[182] In 1994, Cephalon filed a patent for modafinil in the form of particles of a defined size, represented by U.S. patent 5,618,845, which expired in 2015.[183]

Following the nearing expiration of marketing rights in 2002, generic manufacturers, including Mylan and Teva, applied for FDA approval to market a generic form of modafinil, leading to legal challenges by Cephalon regarding the particle size patent.[184] The patent RE 37,516 was declared invalid and unenforceable in 2011.[185]

In addition, Cephalon entered agreements with several generic drug manufacturers to delay the sale of generic modafinil in the US. These agreements were subject to legal scrutiny and antitrust investigations, culminating in a ruling by the Court of Appeals in 2016, which found that the settlements did not violate antitrust laws.[186]

Sports

The regulation of modafinil as a doping agent has been controversial in the sporting world, with high-profile cases attracting press coverage since several prominent American athletes tested positive for the substance. Some athletes who used modafinil protested that the drug was not on the prohibited list at the time of their offenses.[187] However, the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) maintains that modafinil was related to already-banned substances. The Agency added modafinil to its list of prohibited substances on August 3, 2004, ten days before the start of the 2004 Summer Olympics.

Several athletes (such as sprinter Kelli White in 2003,[188] cyclist David Clinger[189] and basketball player Diana Taurasi[190] in 2010, and rower Timothy Grant in 2015[191]) were accused of using modafinil as a performance-enhancing doping agent. Taurasi and another player—Monique Coker, tested at the same lab—were later cleared.[192] Kelli White, who tested positive after her 100m victory at the 2003 World Championships in Paris, was stripped of her gold medals.[193] She claimed that she used modafinil to treat narcolepsy, but the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) ruled that modafinil was a performance-enhancing drug.[193]

The BALCO scandal brought to light an unsubstantiated (but widely published) account of Major League Baseball's all-time leading home-run hitter Barry Bonds' supplemental chemical regimen that included modafinil in addition to anabolic steroids and human growth hormone.[194]

In a study on 15 healthy male subjects, published in Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, an academic journal, acute ingestion of modafinil of 4 mg·kg−1 (at a dose of 4 mg per kilogram of body weight), prolonged exercise time to exhaustion while performing at 85% of VO2max threshold, and also reduced the perception of effort required to maintain this threshold,[195] i.e., the control subjects were able to perform at 85% of their maximum oxygen consumption without feeling as much effort as without modafinil (with placebo).[195]

Social views

The use of modafinil as a supposed cognitive enhancer is viewed differently among various groups.[196] Some groups consider such use as cheating, unnatural, or risky.[197] For instance, some academic institutions such as University of Sussex in the UK have explored this question raised by the students, although the university do not have a strong, official stance on its use, explaining that it is a prescription drug and the decision should be made by the doctor on whether to prescribe modafinil to a student.[198] In the realm of bioethics, the President's Council on Bioethics in the US, chaired by Leon Kass, argued that excellence achieved through the use of drugs like modafinil is "cheap" as it obviates the need for hard work and study, and is not fully authentic because the excellence is partly attributable to the drug, not the individual.[199] On the other hand, some people, particularly those in high-pressure environments like Wall Street traders, do not view the use of modafinil as cheating. They argue that if modafinil can give them an edge and they are aware of the risks involved, it should not be considered as cheating.[200] Due to such varying views, modafinil users for nacrolepsy may cope with stigma by hiding, denying, or justifying their use, or by seeking support from others who share their views or experiences.[88][201]

Research

Psychiatric conditions

Major depression

Modafinil has been studied in the treatment of major depressive disorder.[202][203][204] In a 2021 systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of psychostimulants for depression, modafinil and other stimulants such as methylphenidate and amphetamines improved depression in traditional meta-analysis.[204] However, when subjected to network meta-analysis, modafinil and most other stimulants did not significantly improve depression, with only methylphenidate remaining effective.[204] Modafinil and other stimulants likewise did not improve quality of life in the meta-analysis, although there was evidence for reduced fatigue and sleepiness with modafinil and other stimulants.[204] While significant effectiveness of modafinil for depression has been reported,[205][206][203] reviews and meta-analyses note that the effectiveness of modafinil for depression is limited, the quality of available evidence is low, and the results are inconclusive.[207][204][208]

Bipolar depression

Modafinil and armodafinil have been repurposed as adjunctive treatments for acute depression in people with bipolar disorder.[209] A 2021 meta-analysis concluded that add-on modafinil and armodafinil were more effective than placebo on response to treatment, clinical remission, and reduction in depressive symptoms, with only minor side effects, but the effect sizes are small and the quality of evidence is therefore low, limiting the clinical relevance of the evidence.[209] Very low rates of mood switch (a change in mood from one extreme to another)[210] have been observed with modafinil and armodafinil in bipolar disorder.[206][211]

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (research)

Modafinil was considered for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) because of its lower abuse potential than conventional psychostimulants like methylphenidate and amphetamines.[40][212] In 2008, an application to market modafinil for pediatric ADHD was submitted to the Food and Drug Administration in the USA.[213]

However, evidence of modafinil for treatment of adult ADHD is mixed, and a 2016 systematic review of alternative drug therapies for adult ADHD did not recommend its use in this context.[36] In a later large phase 3 clinical trial of modafinil for adult ADHD, modafinil was not effective in improving symptoms, and there was a high rate of side effects (86%) and discontinuation (47%).[214] The poor tolerability of modafinil in this study was possibly due to the use of excessively high doses (210–500 mg).[214] Another reason for the denial of the approval was due to concerns about rare but serious dermatological toxicity (Stevens–Johnson syndrome).[213]

Substance dependence

Modafinil was studied for the treatment of stimulant dependence, but the results are mixed and inconclusive.[14][215]

Modafinil has been investigated as a possible pharmacotherapy for substance abuse, especially stimulant abuse, because of its effects on the dopaminergic system. Modafinil binds to the dopamine transporter and inhibits its reuptake, increasing extracellular dopamine levels in the brain. The affinity and occupancy of modafinil at the dopamine transporter are comparable to those of low doses of methylphenidate, a widely used stimulant with high abuse potential. Modafinil also shares behavioral effects with psychostimulants, such as enhancing arousal, attention, and cognitive performance. However, unlike most psychostimulants, modafinil has a low potential for misuse and abuse, as evidenced by its low self-administration rates in animals and humans and its lack of euphoric or reinforcing effects in clinical studies. This combination of pharmacological and behavioral properties makes modafinil a promising candidate for a replacement therapy for stimulant abuse, as it could provide some of the therapeutic benefits of stimulants without their adverse consequences, still, modafinil is not a controlled substance in most countries, unlike other medications that have similar effects on the dopaminergic system, such as bupropion, which has a lower affinity and occupancy at the dopamine transporter than modafinil or methylphenidate and is also used to treat depression and nicotine dependence.[216]

Despite these theoretical advantages, the empirical evidence for the efficacy of modafinil in treating substance abuse has been inconsistent. Several randomized controlled trials have evaluated the effects of modafinil on cocaine and amphetamine dependence, but the results have been mostly negative or inconclusive. Neither modafinil nor methylphenidate were effective in promoting sustained abstinence from cocaine or amphetamine use, compared to placebo or other active treatments. The lack of efficacy of modafinil might be due to its relatively weak effects on the dopaminergic system, which might not be sufficient to counteract the solid reinforcing effects of stimulants. Still, the doses of modafinil used in the trials (ranging 100–400 mg/d) might have been too low to produce optimal effects, and higher doses (up to 800 mg/d) might be more effective, but also more likely to cause adverse effects and abuse liability.[216]

The clinical trials that have tested modafinil as a treatment for stimulant abuse have failed to demonstrate its efficacy and the optimal dose and duration of modafinil treatment remain unclear, and modafinil is not a recommended pharmacotherapy for stimulant abuse.[216]

Treatment of cocaine addiction

Modafinil has been studied for the treatment of cocaine addiction.[21] Modafinil binds to the dopamine transporter (DAT) in an open-to-out conformation, differently than cocaine and methylphenidate.[217][218][219] Subjects pretreated with modafinil report experiencing less euphoria from cocaine administration.[218] Modafinil does not potentiate self-administration of cocaine in pretreated rats.[220]

The mechanism by which modafinil inhibits cocaine self-administration is likely more complex than the simple observation that modafinil occupies the DAT, as drugs like methylphenidate (another dopamine re-uptake inhibitor (DRI) fail to reduce cocaine self-administration.[217][221] Atypical DRIs like modafinil that bind to the DAT in an open-to-out conformation often lack abuse potential relative to cocaine-like DAT ligands.[222]

Schizophrenia

Modafinil and armodafinil were studied as a complement to antipsychotic medications in the treatment of schizophrenia. They showed no effect on positive symptoms or cognitive performance.[223][224] A 2015 meta-analysis found that modafinil and armodafinil may slightly reduce negative symptoms in people with acute schizophrenia, though they do not appear useful for people with the condition who are stable, with high negative symptom scores.[224] Among medications demonstrated to be effective for reducing negative symptoms in combination with antipsychotics, modafinil and armodafinil are among the smallest effect sizes.[225]

Cognitive enhancement

A 2015 review of clinical studies of possible nootropic effects in healthy people found: "...whilst most studies employing basic testing paradigms show that modafinil intake enhances executive function, only half show improvements in attention and learning and memory, and a few even report impairments in divergent creative thinking. In contrast, when more complex assessments are used, modafinil appears to consistently engender enhancement of attention, executive functions, and learning. Importantly, we did not observe any preponderances for side effects or mood changes."[18] A 2019 review of studies of a single-dose of modafinil on mental function in healthy, non-sleep-deprived people found a statistically significant but small effect and concluded that the drug has limited usefulness as a cognitive enhancer in non-sleep-deprived persons.[226] A 2020 review of the cognitive enhancing potential of methylphenidate, d-amphetamine, and modafinil in healthy individuals across various domains found that modafinil has a small, positive effect on memory updating.[227]

Modafinil has been used off-label in trials with people with post-chemotherapy cognitive impairment, also known as "chemobrain", but a 2011 review found that it was no better than a placebo.[228]

Post-anesthesia sedation

General anesthesia is required for many surgeries, but may cause lingering fatigue, sedation, and/or drowsiness after surgery that lasts for hours to days. In outpatient settings in which patients are discharged home after surgery, this sedation, fatigue, and occasional dizziness is problematic, but it was only tested in one small study, and the results are inconclusive.[39]

Modafinil was studied for use in multiple sclerosis-associated fatigue, but the resulting evidence was weak and inconclusive.[229][230][231] There were two small controlled studies with conflicting results, and no large, long-term, randomized controlled studies.[31] Therefore, the benefit of using modafinil for the treatment of multiple sclerosis-related fatigue was not confirmed by the solid evidence.[31][232]

Findings from controlled studies on modafinil's effectiveness in this application are mixed, largely due to the absence of extensive, long-term, randomized controlled trials.[31] In a placebo-controlled clinical trial, modafinil did not significantly reduce fatigue compared to the placebo.[233] Additionally, the modafinil-treated group reported a higher incidence of side effects, such as insomnia and gastrointestinal issues.[233]

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome

Caution should be exercised in patients who have narcolepsy in comorbidity with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS). Modafinil, like other centrally acting stimulants prescribed for patients in narcolepsy, increases POTS-related autonomic dysfunction and results in tachycardia/arrhythmia side effects in patients with cardiovascular risk factors. Sodium oxybate, a metabolite of GABA, is an alternative drug for stimulant-intolerant patients with POTS.[234][235]

Inflammation

There is limited research on the potential use of modafinil as an anti-inflammatory agent,[236][237] even though some studies predict that modafinil may have anti-inflammatory effects.[238][239] The results of studies on the potential anti-inflammatory properties of modafinil still need to be more conclusive.[237][240][236]

References

- ^ a b c Mignot EJ (October 2012). "A practical guide to the therapy of narcolepsy and hypersomnia syndromes". Neurotherapeutics. 9 (4): 739–752. doi:10.1007/s13311-012-0150-9. PMC 3480574. PMID 23065655.

- ^ Krishnan R, Chary KV (2015). "A rare case modafinil dependence". Journal of Pharmacology & Pharmacotherapeutics. 6 (1). J Pharmacol Pharmacotherapy: 49–50. doi:10.4103/0976-500X.149149. PMC 4319252. PMID 25709356.

- ^ a b "Modafinil Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on March 30, 2019. Retrieved June 24, 2018.

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved October 22, 2023.

- ^ Anvisa (March 31, 2023). "RDC Nº 784 – Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 – Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published April 4, 2023). Archived from the original on August 3, 2023. Retrieved August 3, 2023.

- ^ "Modafinil Product information". Health Canada. April 25, 2012. Archived from the original on June 10, 2022. Retrieved June 10, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "Provigil- modafinil tablet". DailyMed. November 30, 2018. Archived from the original on June 10, 2022. Retrieved June 10, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Robertson P, Hellriegel ET (2003). "Clinical pharmacokinetic profile of modafinil". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 42 (2): 123–137. doi:10.2165/00003088-200342020-00002. PMID 12537513. S2CID 1266677.

- ^ Darwish M, Kirby M, Hellriegel ET, Yang R, Robertson P (2009). "Pharmacokinetic profile of armodafinil in healthy subjects: pooled analysis of data from three randomized studies". Clinical Drug Investigation. 29 (2): 87–100. doi:10.2165/0044011-200929020-00003. PMID 19133704. S2CID 24886727.

- ^ "Nuvigil- armodafinil tablet". DailyMed. November 30, 2018. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved June 10, 2022.

- ^ a b Robertson P, DeCory HH, Madan A, Parkinson A (June 2000). "In vitro inhibition and induction of human hepatic cytochrome P450 enzymes by modafinil". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 28 (6): 664–671. PMID 10820139.

- ^ Maski K, Trotti LM, Kotagal S, Robert Auger R, Rowley JA, Hashmi SD, Watson NF (September 2021). "Treatment of central disorders of hypersomnolence: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline". J Clin Sleep Med. 17 (9): 1881–1893. doi:10.5664/jcsm.9328. PMC 8636351. PMID 34743789.

- ^ a b Kim D (2012). "Practical use and risk of modafinil, a novel waking drug". Environ Health Toxicol. 27: e2012007. doi:10.5620/eht.2012.27.e2012007. PMC 3286657. PMID 22375280.

- ^ a b c Tanda G, Hersey M, Hempel B, Xi ZX, Newman AH (February 2021). "Modafinil and its structural analogs as atypical dopamine uptake inhibitors and potential medications for psychostimulant use disorder". Curr Opin Pharmacol. 56: 13–21. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2020.07.007. PMC 8247144. PMID 32927246.

- ^ Barateau L, Pizza F, Plazzi G, Dauvilliers Y (August 2022). "Narcolepsy". J Sleep Res. 31 (4): e13631. doi:10.1111/jsr.13631. PMID 35624073. S2CID 251107306.

- ^ Anderson D (June 2021). "Narcolepsy: A clinical review". JAAPA. 34 (6): 20–25. doi:10.1097/01.JAA.0000750944.46705.36. PMID 34031309. S2CID 241205299.

- ^ a b c d "Provigil Prescribing Information" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc. January 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 17, 2017. Retrieved July 18, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Hashemian SM, Farhadi T (2020). "A review on modafinil: the characteristics, function, and use in critical care". J Drug Assess. 9 (1): 82–86. doi:10.1080/21556660.2020.1745209. PMC 7170336. PMID 32341841.

- ^ Morgenthaler TI, Lee-Chiong T, Alessi C, Friedman L, Aurora RN, Boehlecke B, Brown T, Chesson AL, Kapur V, Maganti R, Owens J, Pancer J, Swick TJ, Zak R (November 2007). "Practice parameters for the clinical evaluation and treatment of circadian rhythm sleep disorders. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine report". Sleep. 30 (11): 1445–1459. doi:10.1093/sleep/30.11.1445. PMC 2082098. PMID 18041479.

- ^ Chapman JL, Vakulin A, Hedner J, Yee BJ, Marshall NS (May 2016). "Modafinil/armodafinil in obstructive sleep apnoea: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The European Respiratory Journal. 47 (5): 1420–1428. doi:10.1183/13993003.01509-2015. PMID 26846828. S2CID 4730459.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Greenblatt K, Adams N (February 2022). "Modafinil". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30285371. Archived from the original on October 8, 2022. Retrieved October 9, 2022.

- ^ "Modafinil (Provigil): Now restricted to narcolepsy".

- ^ "Modafinil: Restricted use recommended".

- ^ Arnulf I, Thomas R, Roy A, Dauvilliers Y (June 2023). "Update on the treatment of idiopathic hypersomnia: Progress, challenges, and expert opinion". Sleep Med Rev. 69: 101766. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2023.101766. PMID 36921459. S2CID 257214950.

- ^ https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/020717s037s038lbl.pdf

- ^ "Drug Summary".

- ^ "Multiple sclerosis in adults: Management, Guidance". The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). June 22, 2022. Archived from the original on September 5, 2022. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ "Provigil". National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Archived from the original on September 5, 2022. Retrieved September 6, 2022.

- ^ Ciancio A, Moretti MC, Natale A, Rodolico A, Signorelli MS, Petralia A, Altamura M, Bellomo A, Zanghì A, D'Amico E, Avolio C, Concerto C (July 2023). "Personality Traits and Fatigue in Multiple Sclerosis: A Narrative Review". J Clin Med. 12 (13): 4518. doi:10.3390/jcm12134518. PMC 10342558. PMID 37445551.

- ^ MacAllister WS, Krupp LB (May 2005). "Multiple sclerosis-related fatigue". Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 16 (2): 483–502. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2005.01.014. PMID 15893683.

- ^ a b c d Brown JN, Howard CA, Kemp DW (June 2010). "Modafinil for the treatment of multiple sclerosis-related fatigue". Ann Pharmacother. 44 (6): 1098–103. doi:10.1345/aph.1M705. PMID 20442351. S2CID 207263842.

- ^ Wilms W, Woźniak-Karczewska M, Corvini PF, Chrzanowski Ł (October 2019). "Nootropic drugs: Methylphenidate, modafinil and piracetam – Population use trends, occurrence in the environment, ecotoxicity and removal methods – A review". Chemosphere. 233: 771–785. Bibcode:2019Chmsp.233..771W. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.06.016. PMID 31200137. S2CID 189861826.

- ^ Kittel-Schneider S, Quednow BB, Leutritz AL, McNeill RV, Reif A (May 2021). "Parental ADHD in pregnancy and the postpartum period – A systematic review" (PDF). Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 124: 63–77. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.01.002. PMID 33516734. S2CID 231723198.

- ^ Weiergräber M, Ehninger D, Broich K (April 2017). "Neuroenhancement and mood enhancement – Physiological and pharmacodynamical background". Medizinische Monatsschrift Fur Pharmazeuten. 40 (4): 154–164. PMID 29952165.

- ^ Stuhec M, Lukić P, Locatelli I (February 2019). "Efficacy, Acceptability, and Tolerability of Lisdexamfetamine, Mixed Amphetamine Salts, Methylphenidate, and Modafinil in the Treatment of Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 53 (2): 121–133. doi:10.1177/1060028018795703. PMID 30117329. S2CID 52019992.

- ^ a b Buoli M, Serati M, Cahn W (2016). "Alternative pharmacological strategies for adult ADHD treatment: a systematic review". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 16 (2): 131–144. doi:10.1586/14737175.2016.1135735. PMID 26693882. S2CID 33004517.

- ^ Cortese S, Adamo N, Del Giovane C, Mohr-Jensen C, Hayes AJ, Carucci S, et al. (September 2018). "Comparative efficacy and tolerability of medications for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children, adolescents, and adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis". The Lancet. Psychiatry. 5 (9): 727–738. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30269-4. PMC 6109107. PMID 30097390.

- ^ Rodrigues R, Lai MC, Beswick A, Gorman DA, Anagnostou E, Szatmari P, Anderson KK, Ameis SH (June 2021). "Practitioner Review: Pharmacological treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms in children and youth with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis". J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 62 (6): 680–700. doi:10.1111/jcpp.13305. PMID 32845025. S2CID 221329069.

- ^ a b c Ballon JS, Feifel D (April 2006). "A systematic review of modafinil: Potential clinical uses and mechanisms of action" (PDF). The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 67 (4): 554–566. doi:10.4088/jcp.v67n0406. PMID 16669720. S2CID 17047074. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 20, 2019. Retrieved November 14, 2020.

- ^ a b Turner D (April 2006). "A review of the use of modafinil for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 6 (4): 455–468. doi:10.1586/14737175.6.4.455. PMID 16623645. S2CID 24293088.

- ^ Lindsay SE, Gudelsky GA, Heaton PC (October 2006). "Use of modafinil for the treatment of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 40 (10): 1829–1833. doi:10.1345/aph.1H024. PMID 16954326. S2CID 37368284.

- ^ Bond DJ, Hadjipavlou G, Lam RW, McIntyre RS, Beaulieu S, Schaffer A, Weiss M (February 2012). "The Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) task force recommendations for the management of patients with mood disorders and comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Ann Clin Psychiatry. 24 (1): 23–37. PMID 22303520.

- ^ Nunez NA, Singh B, Romo-Nava F, Joseph B, Veldic M, Cuellar-Barboza A, et al. (March 2020). "Efficacy and tolerability of adjunctive modafinil/armodafinil in bipolar depression: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Bipolar Disorders. 22 (2): 109–120. doi:10.1111/bdi.12859. PMID 31643130.

- ^ Elsayed OH, Ercis M, Pahwa M, Singh B (2022). "Treatment-Resistant Bipolar Depression: Therapeutic Trends, Challenges and Future Directions". Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 18: 2927–2943. doi:10.2147/NDT.S273503. PMC 9767030. PMID 36561896.

- ^ Sylvia Hughes (February 1991). "Drugged troops could soldier on without sleep". New Scientist. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021.

- ^ "Air Force scientists battle aviator fatigue". Air Force. April 30, 2004. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

- ^ a b c Van Puyvelde M, Van Cutsem J, Lacroix E, Pattyn N (January 2022). "A State-of-the-Art Review on the Use of Modafinil as A Performance-enhancing Drug in the Context of Military Operationality". Military Medicine. 187 (1–2): 52–64. doi:10.1093/milmed/usab398. PMID 34632515.

- ^ a b Brunyé TT, Brou R, Doty TJ (2020). "A Review of US Army Research Contributing to Cognitive Enhancement in Military Contexts". J Cogn Enhanc. 4 (4): 453–468. doi:10.1007/s41465-020-00167-3. S2CID 256621326.

- ^ "Go Pills for Black Shoes? | Proceedings - July 2017 Vol. 143/7/1,373".

- ^ Caldwell JA, Caldwell JL (July 2005). "Fatigue in military aviation: an overview of US military-approved pharmacological countermeasures". Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine. 76 (7 Suppl): C39–C51. PMID 16018329.

- ^ Sample I, Evans R (July 29, 2004). "MoD bought thousands of stay awake pills in advance of war in Iraq". The Guardian.

- ^ a b c d Denis F (2021). "Smart drugs et nootropiques". Socio-anthropologie (43): 97–110. doi:10.4000/socio-anthropologie.8393. ISSN 1276-8707. S2CID 237863162.

- ^ "Les cobayes de la guerre du Golfe". Le Monde (in French). December 18, 2005. Archived from the original on April 10, 2021. Retrieved February 26, 2021.

- ^ Martin R (November 1, 2003). "It's Wake-Up Time". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved May 23, 2019.

- ^ Wheeler B (October 26, 2006). "BBC report on MoD research into modafinil". BBC News. Archived from the original on February 15, 2009. Retrieved July 4, 2012.

- ^ "Indian Air Force pilots popping pills to 'heighten alertness'". DAWN. February 8, 2016. Retrieved January 5, 2017.

- ^ Taylor GP Jr, Keys RE (December 1, 2003). "Memorandum for SEE distribution" (PDF). United States Department of the Air Force. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 12, 2009.

- ^ "Air Force Special Operations Command Instruction 48–101" (PDF). November 30, 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 10, 2018.

(sects. 1.7.4), U.S. Air Force Special Operations Command

- ^ Thirsk R, Kuipers A, Mukai C, Williams D (June 2009). "The space-flight environment: the International Space Station and beyond". CMAJ. 180 (12): 1216–1220. doi:10.1503/cmaj.081125. PMC 2691437. PMID 19487390.

- ^ "Smart drugs". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

- ^ Slotnik, Daniel E. (October 11, 2017). "Michel Jouvet, Who Unlocked REM Sleep's Secrets, Dies at 91". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

- ^ Cadwalladr C (February 14, 2015). "Students used to take drugs to get high. Now they take them to get higher grades". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- ^ "The drug does work". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

- ^ "Professors are taking the same 'smart drugs' as students to keep up with workloads". The Independent. May 30, 2017. Archived from the original on December 7, 2022. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- ^ Talbot M. "Brain Gain". The New Yorker. Retrieved April 9, 2017.

- ^ "Towards immortality". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

- ^ Van Rooyen LR, Gihwala R, Laher AE (May 2021). "Stimulant use among prehospital emergency care personnel in Gauteng Province, South Africa". South African Medical Journal = Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Geneeskunde. 111 (6): 587–590. doi:10.7196/SAMJ.2021.v111i6.15465. PMID 34382572. S2CID 236402826.

- ^ "Supercharging the brain". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

- ^ Zamanian MY, Karimvandi MN, Nikbakhtzadeh M, Zahedi E, Bokov DO, Kujawska M, et al. (2023). "Effects of Modafinil (Provigil) on Memory and Learning in Experimental and Clinical Studies: From Molecular Mechanisms to Behaviour Molecular Mechanisms and Behavioural Effects". Current Molecular Pharmacology. 16 (4): 507–516. doi:10.2174/1874467215666220901122824. PMID 36056861. S2CID 252046371.

- ^ Meulen R, Hall W, Mohammed A (2017). Rethinking Cognitive Enhancement. Oxford University Press. p. 116. ISBN 9780198727392.

- ^ Billiard M, Lubin S (2015). "Modafinil: Development and Use of the Compound". Sleep Medicine. New York, NY: Springer New York. pp. 541–544. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-2089-1_61. ISBN 978-1-4939-2088-4.

- ^ Sharif S, Guirguis A, Fergus S, Schifano F (March 2021). "The Use and Impact of Cognitive Enhancers among University Students: A Systematic Review". Brain Sci. 11 (3): 355. doi:10.3390/brainsci11030355. PMC 8000838. PMID 33802176.

- ^ a b Bassetti CL, Kallweit U, Vignatelli L, Plazzi G, Lecendreux M, Baldin E, Dolenc-Groselj L, Jennum P, Khatami R, Manconi M, Mayer G, Partinen M, Pollmächer T, Reading P, Santamaria J, Sonka K, Dauvilliers Y, Lammers GJ (December 2021). "European guideline and expert statements on the management of narcolepsy in adults and children". J Sleep Res. 30 (6): e13387. doi:10.1111/jsr.13387. PMID 34173288. S2CID 235648766.

- ^ "FDA data on Modafinil" (PDF). Accessdata.fda.gov. 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved September 9, 2018.

- ^ "FDA Provigil Drug Safety Data" (PDF). Fda.gov. January 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 2, 2017.

- ^ Sousa A, Dinis-Oliveira RJ (2020). "Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic of the cognitive enhancer modafinil: Relevant clinical and forensic aspects". Substance Abuse. 41 (2): 155–173. doi:10.1080/08897077.2019.1700584. PMID 31951804. S2CID 210709160.

- ^ Rugino T (June 2007). "A review of modafinil film-coated tablets for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 3 (3): 293–301. PMC 2654790. PMID 19300563.

- ^ Modafinil. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 2006. PMID 30000988.

- ^ Miller M, et al. (Hull & East Riding Prescribing Committee). Morgan J (ed.). "Prescribing Framework for Modafinil for Daytime Hypersomnolence and excessive daytime sleepiness in Parkinsons" (PDF). Northern Lincolnshire, UK: National Health Service.

- ^ "Modafinil for the treatment of adult patients with excessive sleepiness" (PDF). National Health Service, UK. November 10, 2022.

- ^ "Australian Adverse Drug Reactions Bulletin 2008". Australian Adverse Drug Reactions Bulletin. December 1, 2008. Archived from the original on July 3, 2020.

- ^ "Provigil" (PDF). Medication Guide. Cephalon, Inc. November 1, 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved December 31, 2013.

- ^ Modafinil. 2012. PMID 31643597.

- ^ "Modafinil (marketed as Provigil): Serious Skin Reactions". Food and Drug Administration. 2007. Archived from the original on January 15, 2009.

- ^ Li, Thian Wen (November 6, 2023). "Three men hospitalised after taking modafinil or armodafinil to stay awake; drugs were not prescribed". The Straits Times.

- ^ Banerjee D, Vitiello MV, Grunstein RR (October 2004). "Pharmacotherapy for excessive daytime sleepiness". Sleep Medicine Reviews. 8 (5): 339–354. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2004.03.002. PMID 15336235.

- ^ Ivanenko A, Kek L, Grosrenaud J (April 28, 2017). "0954 Long-Term Use of Modafinil and Armodafinil in Pediatric Patients with Narcolepsy". Sleep. 40 (suppl_1): A354–A355. doi:10.1093/sleepj/zsx050.953. ISSN 0161-8105. Archived from the original on June 8, 2021. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ a b Teodorini RD, Rycroft N, Smith-Spark JH (2020). "The off-prescription use of modafinil: An online survey of perceived risks and benefits". PLOS ONE. 15 (2): e0227818. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1527818T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0227818. PMC 7001904. PMID 32023288.

- ^ a b "Provigil: Prescribing information" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. Cephalon, Inc. January 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 17, 2017. Retrieved August 16, 2015.

- ^ Warot D, Corruble E, Payan C, Weil JS, Puech AJ (1993). "Subjective effects of modafinil, a new central adrenergic stimulant in healthy volunteers: a comparison with amphetamine, caffeine and placebo". European Psychiatry. 8 (4): 201–208. doi:10.1017/S0924933800002923. ISSN 0924-9338. S2CID 151797528. Archived from the original on July 7, 2023. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ O'Brien CP, Dackis CA, Kampman K (June 2006). "Does modafinil produce euphoria?". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 163 (6): 1109. doi:10.1176/ajp.2006.163.6.1109. PMID 16741217.

- ^ International Narcotics Control Board (July 2020), Yellow List: List of Narcotic Drugs Under International Control, In accordance with the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961 [Protocol of March 25, 1972, amending the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961] (59th ed.), Yellow List PDF, archived from the original on January 16, 2022, retrieved January 12, 2022

- ^ International Narcotics Control Board (July 2020), Green List: List of Psychotropic Substances Under International Control, In accordance with Convention psychotropic substances of 1971 (31st ed.), United Nations Publications, archived from the original on January 18, 2022, retrieved January 12, 2022

- ^ Sangroula D, Motiwala F, Wagle B, Shah VC, Hagi K, Lippmann S (August 2017). "Modafinil Treatment of Cocaine Dependence: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Substance Use & Misuse. 52 (10): 1292–1306. doi:10.1080/10826084.2016.1276597. PMID 28350194. S2CID 4775658.

- ^ a b c d Reinert JP, Dunn RL (September 2019). "Management of overdoses of loperamide, gabapentin, and modafinil: a literature review". Expert Review of Clinical Pharmacology. 12 (9): 901–908. doi:10.1080/17512433.2019.1657830. PMID 31422705. S2CID 201063075.

- ^ "E-Poster Viewing". European Psychiatry. 56: S322–S553. 2019. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2019.01.002. S2CID 210495403.

- ^ Prince V, Philippidou M, Walsh S, Creamer D (March 2018). "Stevens-Johnson syndrome induced by modafinil". Clinical and Experimental Dermatology. 43 (2): 191–192. doi:10.1111/ced.13282. PMID 29028129. S2CID 204987385.

- ^ "Modafinil overdose". Reactions Weekly. 1690: 136. 2018. doi:10.1007/s40278-018-42202-6. S2CID 195079873.

- ^ "Modafinil overdose/misuse/abuse". Reactions Weekly. 1723: 215. 2018. doi:10.1007/s40278-018-52897-7. S2CID 195081462.

- ^ Spiller HA, Borys D, Griffith JR, Klein-Schwartz W, Aleguas A, Sollee D, et al. (February 2009). "Toxicity from modafinil ingestion". Clinical Toxicology. 47 (2): 153–156. doi:10.1080/15563650802175595. PMID 18787992. S2CID 12421545.

- ^ a b "Modafinil Interactions Checker".

- ^ a b "Drug Development and Drug Interactions | Table of Substrates, Inhibitors and Inducers". FDA. May 26, 2021. Archived from the original on November 4, 2020. Retrieved April 8, 2022.

- ^ "Cytochrome P450 3A (including 3A4) inhibitors and inducers". UpToDate. Archived from the original on April 8, 2022. Retrieved April 8, 2022.

- ^ Robertson P, Hellriegel ET, Arora S, Nelson M (February 2002). "Effect of modafinil at steady state on the single-dose pharmacokinetic profile of warfarin in healthy volunteers". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 42 (2): 205–214. doi:10.1177/00912700222011120. PMID 11831544. S2CID 29223738. Archived from the original on October 28, 2022. Retrieved October 28, 2022.

- ^ Zhu HJ, Wang JS, Donovan JL, Jiang Y, Gibson BB, DeVane CL, Markowitz JS (January 2008). "Interactions of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder therapeutic agents with the efflux transporter P-glycoprotein". European Journal of Pharmacology. 578 (2–3): 148–158. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.09.035. PMC 2659508. PMID 17963743.

- ^ a b "Modafinil drug interactions". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on May 3, 2021. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ "National Institutes Drug Information: Modafinil". NIH. July 1, 2005. Archived from the original on June 10, 2007. Retrieved July 21, 2007.

- ^ Minzenberg MJ, Carter CS (June 2008). "Modafinil: a review of neurochemical actions and effects on cognition". Neuropsychopharmacology. 33 (7). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 1477–1502. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1301534. PMID 17712350. S2CID 13752498.

- ^ Samuels ER, Hou RH, Langley RW, Szabadi E, Bradshaw CM (November 2006). "Comparison of pramipexole and modafinil on arousal, autonomic, and endocrine functions in healthy volunteers". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 20 (6). SAGE Publications: 756–770. doi:10.1177/0269881106060770. PMID 16401653. S2CID 8033437.

- ^ Niwa T, Murayama N, Imagawa Y, Yamazaki H (May 2015). "Regioselective hydroxylation of steroid hormones by human cytochromes P450". Drug Metabolism Reviews. 47 (2). Informa UK Limited: 89–110. doi:10.3109/03602532.2015.1011658. PMID 25678418. S2CID 5791536.

- ^ Aquinos BM, García Arabehety J, Canteros TM, de Miguel V, Scibona P, Fainstein-Day P (2021). "[Adrenal crisis associated with modafinil use]". Medicina (in Spanish). 81 (5): 846–849. PMID 34633961.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Zolkowska D, Jain R, Rothman RB, Partilla JS, Roth BL, Setola V, et al. (May 2009). "Evidence for the involvement of dopamine transporters in behavioral stimulant effects of modafinil". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 329 (2): 738–746. doi:10.1124/jpet.108.146142. PMC 2672878. PMID 19197004.

- ^ a b c Krief S, Berrebi-Bertrand I, Nagmar I, Giret M, Belliard S, Perrin D, et al. (October 2021). "Pitolisant, a wake-promoting agent devoid of psychostimulant properties: Preclinical comparison with amphetamine, modafinil, and solriamfetol". Pharmacology Research & Perspectives. 9 (5): e00855. doi:10.1002/prp2.855. PMC 8381683. PMID 34423920.

- ^ a b c Murillo-Rodríguez E, Barciela Veras A, Barbosa Rocha N, Budde H, Machado S (February 2018). "An Overview of the Clinical Uses, Pharmacology, and Safety of Modafinil". ACS Chemical Neuroscience. 9 (2): 151–158. doi:10.1021/acschemneuro.7b00374. PMID 29115823.

- ^ a b c d Loland CJ, Mereu M, Okunola OM, Cao J, Prisinzano TE, Mazier S, Kopajtic T, Shi L, Katz JL, Tanda G, Newman AH (September 2012). "R-modafinil (armodafinil): a unique dopamine uptake inhibitor and potential medication for psychostimulant abuse". Biol Psychiatry. 72 (5): 405–13. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.03.022. PMC 3413742. PMID 22537794.

- ^ a b Seeman P, Guan HC, Hirbec H (August 2009). "Dopamine D2High receptors stimulated by phencyclidines, lysergic acid diethylamide, salvinorin A, and modafinil". Synapse. 63 (8): 698–704. doi:10.1002/syn.20647. PMID 19391150.

- ^ a b c d e f Thorpy MJ, Bogan RK (April 2020). "Update on the pharmacologic management of narcolepsy: mechanisms of action and clinical implications". Sleep Med. 68: 97–109. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2019.09.001. PMID 32032921. S2CID 203405397.

- ^ a b Stahl SM (March 2017). "Modafinil". Prescriber's Guide: Stahl's Essential Psychopharmacology (6th ed.). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 491–495. ISBN 9781108228749.

- ^ a b Gerrard P, Malcolm R (June 2007). "Mechanisms of modafinil: A review of current research". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 3 (3): 349–364. PMC 2654794. PMID 19300566.

- ^ a b c Lazarus M, Chen JF, Huang ZL, Urade Y, Fredholm BB (2019). "Adenosine and Sleep". Handb Exp Pharmacol. 253: 359–381. doi:10.1007/164_2017_36. PMID 28646346.

- ^ Ishizuka T, Murotani T, Yamatodani A (2012). "Action of modafinil through histaminergic and orexinergic neurons". Sleep Hormones. Vitamins & Hormones. Vol. 89. Academic Press. pp. 259–78. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-394623-2.00014-7. ISBN 9780123946232. PMID 22640618.

- ^ Salerno M, Villano I, Nicolosi D, Longhitano L, Loreto C, Lovino A, et al. (January 2019). "Modafinil and orexin system: interactions and medico-legal considerations". Frontiers in Bioscience. 24 (3): 564–575. doi:10.2741/4736. PMID 30468674. S2CID 53713777.

- ^ Que M, Li Y, Wang X, Zhan G, Luo X, Zhou Z (2023). "Role of astrocytes in sleep deprivation: accomplices, resisters, or bystanders?". Front Cell Neurosci. 17: 1188306. doi:10.3389/fncel.2023.1188306. PMC 10330732. PMID 37435045.

- ^ Ingiosi AM, Frank MG (May 2023). "Goodnight, astrocyte: waking up to astroglial mechanisms in sleep". FEBS J. 290 (10): 2553–2564. doi:10.1111/febs.16424. PMC 9463397. PMID 35271767.

- ^ Thorpy MJ (January 2020). "Recently Approved and Upcoming Treatments for Narcolepsy". CNS Drugs. 34 (1): 9–27. doi:10.1007/s40263-019-00689-1. PMC 6982634. PMID 31953791.

- ^ a b Yang S, Kong XY, Hu T, Ge YJ, Li XY, Chen JT, He S, Zhang P, Chen GH (2022). "Aquaporin-4, Connexin-30, and Connexin-43 as Biomarkers for Decreased Objective Sleep Quality and/or Cognition Dysfunction in Patients With Chronic Insomnia Disorder". Front Psychiatry. 13: 856867. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.856867. PMC 8989729. PMID 35401278.

- ^ Szabo ST, Thorpy MJ, Mayer G, Peever JH, Kilduff TS (February 2019). "Neurobiological and immunogenetic aspects of narcolepsy: Implications for pharmacotherapy". Sleep Med Rev. 43: 23–36. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2018.09.006. PMC 6351197. PMID 30503715.

- ^ a b Gilman A, Goodman LS, Hardman JG, Limbird LE (2001). Goodman & Gilman's the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 1984. ISBN 978-0-07-135469-1.

- ^ Ramachandra B (November 2016). "A Critical Review of Properties of Modafinil and Analytical, Bioanalytical Methods for its Determination". Crit Rev Anal Chem. 46 (6): 482–9. doi:10.1080/10408347.2016.1153948. PMID 26908128.

- ^ Schwertner HA, Kong SB (March 2005). "Determination of modafinil in plasma and urine by reversed phase high-performance liquid-chromatography". J Pharm Biomed Anal. 37 (3): 475–9. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2004.11.014. PMID 15740906.

- ^ Robertson P, Hellriegel ET, Arora S, Nelson M (January 2002). "Effect of modafinil on the pharmacokinetics of ethinyl estradiol and triazolam in healthy volunteers". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 71 (1): 46–56. doi:10.1067/mcp.2002.121217. PMID 11823757. S2CID 21552865.

- ^ Chatterjie N, Stables JP, Wang H, Alexander GJ (August 2004). "Anti-narcoleptic agent modafinil and its sulfone: a novel facile synthesis and potential anti-epileptic activity". Neurochem Res. 29 (8): 1481–6. doi:10.1023/b:nere.0000029559.20581.1a. PMID 15260124.

- ^ Bogan RK (April 2010). "Armodafinil in the treatment of excessive sleepiness". Expert Opin Pharmacother. 11 (6): 993–1002. doi:10.1517/14656561003705738. PMID 20307223.

- ^ Wong YN, King SP, Laughton WB, McCormick GC, Grebow PE (March 1998). "Single-dose pharmacokinetics of modafinil and methylphenidate given alone or in combination in healthy male volunteers". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 38 (3): 276–282. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1998.tb04425.x. PMID 9549666. S2CID 26877375.

- ^ Baselt RC (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man. Foster City, CA: Biomedical Publications. pp. 1152–1153. ISBN 978-0-9626523-7-0.

- ^ a b c Spratley TK, Hayes PA, Geer LC, Cooper SD, McKibben TD (2005). "Analytical Profiles for Five "Designer" Tryptamines" (PDF). Microgram Journal. 3 (1–2): 54–68. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 2, 2020. Retrieved December 18, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Modafinil reaction with the Froehde reagent and others". Reagent Tests UK. December 13, 2015. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved December 18, 2015.