Women in Islam: Difference between revisions

Sourced data |

|||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

{{Women in society sidebar |religion}} |

{{Women in society sidebar |religion}} |

||

The experiences of [[Muslim]] women vary widely between and within different societies.<ref name=bodman>{{cite book|title=Women in Muslim Societies: Diversity Within Unity|editors=Herbert L. Bodman, Nayereh Esfahlani Tohidi|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=PFzdA2Hini4C&pg=PA2|pages=2–3|publisher=Lynne Rienner Publishers|year=1998}}</ref> At the same time, their adherence to Islam is a shared factor that affects their lives to a varying degree and gives them a common identity that may serve to bridge the wide cultural, social, and economic differences between them.<ref name=bodman/> |

The experiences of [[Muslim]] women vary widely between and within different societies<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://qurannyc.com/status-women-islam-quran/|title=The status of Women in Islam as by Quran - Quran|date=2017-09-05|work=Quran|access-date=2017-09-05|language=en-US}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|url=https://pbctimes.com/prayertimes/women-islam/|title=The status of Women in Islam - Prayer Times NYC|date=2017-04-10|work=Prayer Times NYC|access-date=2017-09-05|language=en-US}}</ref>.<ref name=bodman>{{cite book|title=Women in Muslim Societies: Diversity Within Unity|editors=Herbert L. Bodman, Nayereh Esfahlani Tohidi|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=PFzdA2Hini4C&pg=PA2|pages=2–3|publisher=Lynne Rienner Publishers|year=1998}}</ref> At the same time, their adherence to Islam is a shared factor that affects their lives to a varying degree and gives them a common identity that may serve to bridge the wide cultural, social, and economic differences between them.<ref name=bodman/> |

||

Among the influences which have played an important role in defining the social, spiritual and cosmological status of women in the course of [[History of Islam|Islamic history]] are Islam's sacred text, the [[Quran|Qur'an]]; the [[Hadith|Ḥadīths]], which are traditions relating to the deeds and aphorisms of Islam's [[Muhammad|Prophet Muḥammad]];<ref>i{{Cite book|title=The Concise Encyclopaedia of Islam|last=Glassé|first=Cyril|publisher=Stacey International|year=1989|isbn=|location=London, England|pages=141–143}}</ref> ijmā', which is a consensus, expressed or tacit, on a question of law;<ref>{{Cite book|title=The Concise Encyclopaedia of Islam|last=Glassé|first=Cyril|publisher=Stacey International|year=1989|isbn=|location=London, England|pages=182}}</ref> qiyās, the principle by which the laws of the Qur'an and the Sunnah or Prophetic custom are applied to situations not explicitly covered by these two sources of legislation;<ref>{{Cite book|title=The Concise Encyclopaedia of Islam|last=Glassé|first=Cyril|publisher=Stacey International|year=1989|isbn=|location=London, England|pages=325}}</ref> and fatwas, non-binding published opinions or decisions regarding religious doctrine or points of law. Additional influences include pre-Islamic cultural traditions; secular laws, which are fully accepted in Islam so long as they do not directly contradict Islamic precepts;<ref>{{Cite book|title=The Heart of Islam: Enduring Values for Humanity|last=Nasr|first=Seyyed Hossein|publisher=HarperOne|year=2004|isbn=978-0-06-073064-2|location=New York|pages=121–122}}</ref> religious authorities, including government-controlled agencies such as the [[Indonesian Ulema Council]] and Turkey's [[Presidency of Religious Affairs|Diyanet]];<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.csmonitor.com/2005/0427/p04s01-woeu.html|title=In Turkey, Muslim women gain expanded religious authority|last=Schleifer|first=Yigal|date=27 April 2005|website=The Christian Science Monitor|publisher=|access-date=10 June 2015}}</ref> and spiritual teachers, which are particularly prominent in Islamic mysticism or [[Sufism]]. Many of the latter{{snd}}including perhaps most famously, Ibn al-'Arabī{{snd}}have themselves produced texts that have elucidated the metaphysical symbolism of the feminine principle in Islam.<ref>{{Cite book|title=The Tao of Islam: A Sourcebook on Gender Relationships in Islamic Thought|last=Murata|first=Sachiko|publisher=State University of New York Press|year=1992|isbn=978-0-7914-0914-5|location=Albany|pages=188–202}}</ref> |

Among the influences which have played an important role in defining the social, spiritual and cosmological [https://pbctimes.com/prayertimes/women-islam/ status of women in Islam] among the course of [[History of Islam|Islamic history]] are Islam's sacred text, the [[Quran|Qur'an]]; the [[Hadith|Ḥadīths]], which are traditions relating to the deeds and aphorisms of Islam's [[Muhammad|Prophet Muḥammad]];<ref>i{{Cite book|title=The Concise Encyclopaedia of Islam|last=Glassé|first=Cyril|publisher=Stacey International|year=1989|isbn=|location=London, England|pages=141–143}}</ref> ijmā', which is a consensus, expressed or tacit, on a question of law;<ref>{{Cite book|title=The Concise Encyclopaedia of Islam|last=Glassé|first=Cyril|publisher=Stacey International|year=1989|isbn=|location=London, England|pages=182}}</ref> qiyās, the principle by which the laws of the Qur'an and the Sunnah or Prophetic custom are applied to situations not explicitly covered by these two sources of legislation;<ref>{{Cite book|title=The Concise Encyclopaedia of Islam|last=Glassé|first=Cyril|publisher=Stacey International|year=1989|isbn=|location=London, England|pages=325}}</ref> and fatwas, non-binding published opinions or decisions regarding religious doctrine or points of law. Additional influences include pre-Islamic cultural traditions; secular laws, which are fully accepted in Islam so long as they do not directly contradict Islamic precepts;<ref>{{Cite book|title=The Heart of Islam: Enduring Values for Humanity|last=Nasr|first=Seyyed Hossein|publisher=HarperOne|year=2004|isbn=978-0-06-073064-2|location=New York|pages=121–122}}</ref> religious authorities, including government-controlled agencies such as the [[Indonesian Ulema Council]] and Turkey's [[Presidency of Religious Affairs|Diyanet]];<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.csmonitor.com/2005/0427/p04s01-woeu.html|title=In Turkey, Muslim women gain expanded religious authority|last=Schleifer|first=Yigal|date=27 April 2005|website=The Christian Science Monitor|publisher=|access-date=10 June 2015}}</ref> and spiritual teachers, which are particularly prominent in Islamic mysticism or [[Sufism]]. Many of the latter{{snd}}including perhaps most famously, Ibn al-'Arabī{{snd}}have themselves produced texts that have elucidated the metaphysical symbolism of the feminine principle in Islam.<ref>{{Cite book|title=The Tao of Islam: A Sourcebook on Gender Relationships in Islamic Thought|last=Murata|first=Sachiko|publisher=State University of New York Press|year=1992|isbn=978-0-7914-0914-5|location=Albany|pages=188–202}}</ref> |

||

There is considerable variation as to how the above sources are interpreted by Orthodox Muslims, both Sunni and Shi'a{{snd}}approximately 90% of the world's Muslim population{{snd}}and ideological fundamentalists, most notably those subscribing to Wahhabism or [[Salafi movement|Salafism]], who comprise roughly 9% of the total.<ref>{{Cite book|title=The Muslim 500: The World's 500 Most Influential Muslims, 2016|last=Schleifer|first=Professor S Abdallah|publisher=The Royal Islamic Strategic Studies Centre|year=2015|isbn=978-1-4679-9976-2|location=Amman|pages=28}}</ref> In particular, Wahhabis and Salafists tend to reject mysticism and theology outright; this has profound implications for the way that women are perceived within these ideological sects.<ref>{{Cite book|title=Terror's Source: The Ideology of Wahhabi-Salafism and its Consequences|last=Oliveti|first=Vicenzo|publisher=Amadeus Books|year=2002|isbn=978-0-9543729-0-3|location=Birmingham, United Kingdom|pages=34–35}}</ref> Conversely, within Islamic Orthodoxy, both the established theological schools and Sufism are at least somewhat influential.<ref>{{Cite book|title=The Muslim 500: The World's 500 Most Influential Muslims, 2016|last=Schleifer|first=Prof S Abdallah|publisher=The Royal Islamic Strategic Studies Centre|year=2015|isbn=978-1-4679-9976-2|location=Amman|pages=28–30}}</ref> |

There is considerable variation as to how the above sources are interpreted by Orthodox Muslims, both Sunni and Shi'a{{snd}}approximately 90% of the world's Muslim population{{snd}}and ideological fundamentalists, most notably those subscribing to Wahhabism or [[Salafi movement|Salafism]], who comprise roughly 9% of the total.<ref>{{Cite book|title=The Muslim 500: The World's 500 Most Influential Muslims, 2016|last=Schleifer|first=Professor S Abdallah|publisher=The Royal Islamic Strategic Studies Centre|year=2015|isbn=978-1-4679-9976-2|location=Amman|pages=28}}</ref> In particular, Wahhabis and Salafists tend to reject mysticism and theology outright; this has profound implications for the way that women are perceived within these ideological sects.<ref>{{Cite book|title=Terror's Source: The Ideology of Wahhabi-Salafism and its Consequences|last=Oliveti|first=Vicenzo|publisher=Amadeus Books|year=2002|isbn=978-0-9543729-0-3|location=Birmingham, United Kingdom|pages=34–35}}</ref> Conversely, within Islamic Orthodoxy, both the established theological schools and Sufism are at least somewhat influential.<ref>{{Cite book|title=The Muslim 500: The World's 500 Most Influential Muslims, 2016|last=Schleifer|first=Prof S Abdallah|publisher=The Royal Islamic Strategic Studies Centre|year=2015|isbn=978-1-4679-9976-2|location=Amman|pages=28–30}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 08:51, 5 September 2017

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Women in society |

|---|

|

The experiences of Muslim women vary widely between and within different societies[1][2].[3] At the same time, their adherence to Islam is a shared factor that affects their lives to a varying degree and gives them a common identity that may serve to bridge the wide cultural, social, and economic differences between them.[3]

Among the influences which have played an important role in defining the social, spiritual and cosmological status of women in Islam among the course of Islamic history are Islam's sacred text, the Qur'an; the Ḥadīths, which are traditions relating to the deeds and aphorisms of Islam's Prophet Muḥammad;[4] ijmā', which is a consensus, expressed or tacit, on a question of law;[5] qiyās, the principle by which the laws of the Qur'an and the Sunnah or Prophetic custom are applied to situations not explicitly covered by these two sources of legislation;[6] and fatwas, non-binding published opinions or decisions regarding religious doctrine or points of law. Additional influences include pre-Islamic cultural traditions; secular laws, which are fully accepted in Islam so long as they do not directly contradict Islamic precepts;[7] religious authorities, including government-controlled agencies such as the Indonesian Ulema Council and Turkey's Diyanet;[8] and spiritual teachers, which are particularly prominent in Islamic mysticism or Sufism. Many of the latter – including perhaps most famously, Ibn al-'Arabī – have themselves produced texts that have elucidated the metaphysical symbolism of the feminine principle in Islam.[9]

There is considerable variation as to how the above sources are interpreted by Orthodox Muslims, both Sunni and Shi'a – approximately 90% of the world's Muslim population – and ideological fundamentalists, most notably those subscribing to Wahhabism or Salafism, who comprise roughly 9% of the total.[10] In particular, Wahhabis and Salafists tend to reject mysticism and theology outright; this has profound implications for the way that women are perceived within these ideological sects.[11] Conversely, within Islamic Orthodoxy, both the established theological schools and Sufism are at least somewhat influential.[12]

Sources of influence

There are four sources of influence under Islam for Muslim women. The first two, the Quran and Hadiths, are considered primary sources, while the other two are secondary and derived sources that differ between various Muslim sects and schools of Islamic jurisprudence. The secondary sources of influence include ijma, qiyas and, in forms such as fatwa, ijtihad.[13][14][15]

Primary

Women in Islam are provided a number of guidelines under Quran and hadiths, as understood by fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence) as well as of the interpretations derived from the hadith that were agreed upon by majority of Sunni scholars as authentic beyond doubt based on hadith studies.[17][18] These interpretations and their application were shaped by the historical context of the Muslim world at the time they were written.[17]

During his life, Muhammad married nine or eleven women depending upon the differing accounts of who were his wives. In Arabian culture, marriage was generally contracted in accordance with the larger needs of the tribe and was based on the need to form alliances within the tribe and with other tribes. Virginity at the time of marriage was emphasised as a tribal honour.[19] William Montgomery Watt states that all of Muhammad's marriages had the political aspect of strengthening friendly relationships and were based on the Arabian custom.[20]

An-Nisa

Women or Sūrat an-Nisāʼ[21] is the fourth chapter of the Quran. The title of the sura derives from the numerous references to women throughout the chapter, including verses 3-4 and 127-130.[22]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2016) |

Secondary

The above primary sources of influence on women of Islam do not deal with every conceivable situation over time. This led to the development of jurisprudence and religious schools with Islamic scholars that referred to resources such as identifying authentic documents, internal discussions and establishing a consensus to find the correct religiously approved course of action for Muslims.[13][14] These formed the secondary sources of influence for women. Among them are ijma, qiya, ijtihad and others depending on sect and the school of Islamic law. Included in secondary sources are fatwas, which are often widely distributed, orally or in writing by Muslim clerics, to the masses, in local language and describe behavior, roles and rights of women that conforms with religious requirements. Fatwas are theoretically non-binding, but seriously considered and have often been practiced by most Muslim believers. The secondary sources typically fall into five types of influence: the declared role or behavior for Muslims, both women and men, is considered obligatory, commendable, permissible, despised or prohibited. There is considerable controversy, change over time, and conflict between the secondary sources.[23][24][25]

Gender roles

Gender roles in Islam are simultaneously coloured by two Qur'anic precepts: (i) spiritual equality between women and men; and (ii) the idea that women are meant to exemplify femininity, and men masculinity.[29]

Spiritual equality between women and men is detailed in Sūrat al-Aḥzāb (33:35):

Verily, men who surrender unto God, and women who surrender, and men who believe and women who believe, and men who obey and women who obey, and men who speak the truth and women who speak the truth...and men who give alms and women who give alms, and men who fast and women who fast, and men who guard their modesty and women who guard (their modesty), and men who remember God much and women who remember – God hath prepared for them forgiveness and a vast reward.

Islam's basic view of women and men postulates a complementarity of functions: like everything else in the universe, humanity has been created in a pair (Sūrat al-Dhāriyāt, 51:49) – neither can be complete without the other.[31] In Islamic cosmological thinking, the universe is perceived as an equilibrium built on harmonious polar relationships between the pairs that make up all things.[31] Moreover, all outward phenomena are reflections of inward noumena and ultimately of God.[31]

The emphasis which Islam places upon the feminine/masculine polarity (and therefore complementarity) results, quite logically, in a separation of social functions.[32] In general, a woman's sphere of operation is the home in which she is the dominant figure – and a man's corresponding sphere is the outside world.[33] [better source needed]However, this separation is not, in practice, as rigid as it appears.[32] There are many examples – both in the early history of Islam and in the contemporary world – of Muslim women who have played prominent roles in public life, including being sultanas, queens, elected heads of state and wealthy businesswomen Moreover, it is important to recognise that in Islam, home and family are firmly situated at the centre of life in this world and of society: a man's work cannot take precedence over the private realm.[33]

The Quran dedicates numerous verses to Muslim women, their role, duties and rights, in addition to Sura 4 with 176 verses named "An-Nisa" ("Women").[34]

Islam differentiates the gender role of women who believe in Islam and those who do not.[citation needed] The Muslim male's right to own slave women, seized during military campaigns and jihad against non-believing pagans and infidels from Southern Europe to Africa to India to Central Asia, was considered natural.[35][36] Slave women could be sold without their consent, expected to provide concubinage, required permission from their owner to marry; and children born to them were automatically considered Muslim under Islamic law if the father was a Muslim.[37][38][39]

Female education

The classical position

Both the Qur'an – Islam's sacred text – and the spoken or acted example of the Prophet Muḥammad (Sunnah) advocate the rights of women and men equally to seek knowledge.[41] The Qur'an commands all Muslims to exert effort in the pursuit of knowledge, irrespective of their biological sex: it constantly encourages Muslims to read, think, contemplate and learn from the signs of God in nature.[41] Moreover, Muḥammad encouraged education for both males and females: he declared that seeking knowledge was a religious duty binding upon every Muslim man and woman.[42] Like her male counterpart, each woman is under a moral and religious obligation to seek knowledge, develop her intellect, broaden her outlook, cultivate her talents and then utilise her potential to the benefit of her soul and her society.[43]

The interest of the Prophet Muḥammad in female education was manifest in the fact that he himself used to teach women along with men.[43] Muḥammad's teachings were widely sought by both sexes, and accordingly at the time of his death it was reported that there were many female scholars of Islam.[42] Additionally, the wives of the Prophet Muḥammad – particularly Aisha – also taught both women and men; many of Muḥammad's companions and followers learned the Qur'an, ḥadīth and Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) from Aisha.[44] Notably, there was no restriction placed on the type of knowledge acquired: a woman was free to choose any field of knowledge that interested her.[45] Because Islam recognises that women are in principle wives and mothers, the acquisition of knowledge in fields which are complementary to these social roles was specially emphasised.[46]

History of women's education

Islam encouraged religious education of Muslim women.[47] According to a hadith in Saḥih Muslim variously attributed to 'Ā'isha and Muhammad, the women of the ansar were praiseworthy because shame did not prevent them from asking detailed questions about Islamic law.[47][48]

While it was not common for women to enroll as students in formal religious schools, it was common for women to attend informal lectures and study sessions at mosques, madrasas and other public places. For example, the attendance of women at the Fatimid Caliphate's "sessions of wisdom" (majālis al-ḥikma) was noted by various historians, including Ibn al-Tuwayr, al-Muṣabbiḥī and Imam.[49] Historically, some Muslim women played an important role in the foundation of many religious educational institutions, such as Fatima al-Fihri's founding of the University of al-Karaouine in 859 CE.[50]: 274 According to the 12th-century Sunni scholar Ibn 'Asakir, there were various opportunities for female education in what is known as the Islamic Golden Age. He writes that women could study, earn ijazahs (religious degrees) and qualify as ulama and Islamic teachers.[50]: 196, 198 Similarly, al-Sakhawi devotes one of the twelve volumes of his biographical dictionary Daw al-Lami to female religious scholars between 700 and 1800 CE, giving information on 1,075 of them. [51] Women of prominent urban families were commonly educated in private settings and many of them received and later issued ijazas in hadith studies, calligraphy and poetry recitation.[52][53] Working women learned religious texts and practical skills primarily from each other, though they also received some instruction together with men in mosques and private homes.[52]

During the colonial era, until the early 20th century, there was a gender struggle among Muslims in the British empire; educating women was viewed as a prelude to social chaos, a threat to the moral order, and man's world was viewed as a source of Muslim identity.[54] Muslim women in British India, nevertheless, pressed for their rights independent of men; by the 1930s, 2.5 million girls had entered schools of which 0.5 million were Muslims.[54]

Current situation

- Literacy

In a 2013 statement, the Organization of Islamic Cooperation noted that restricted access to education is among the challenges faced by girls and women in the developing world, including OIC member states.[56] UNICEF notes that out of 24 nations with less than 60% female primary enrollment rates, 17 were Islamic nations; more than half the adult population is illiterate in several Islamic countries, and the proportion reaches 70% among Muslim women.[57] UNESCO estimates that the literacy rate among adult women was about 50% or less in a number of Muslim-majority countries, including Morocco, Yemen, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Niger, Mali, Gambia, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, and Chad.[58] Egypt had a women literacy rate of 64% in 2010, Iraq of 71% and Indonesia of 90%.[58] While literacy has been improving in Saudi Arabia since the 1970s, the overall female literacy rate in 2005 was 50%, compared to male literacy of 72%.[59]

- Gender and participation in education

Some scholars[60][61] contend that Islamic nations have the world's highest gender gap in education. The 2012 World Economic Forum annual gender gap study finds the 17 out of 18 worst performing nations, out of a total of 135 nations, are the following members of Organisation of Islamic Cooperation: Algeria, Jordan, Lebanon, (Nepal[62]), Turkey, Oman, Egypt, Iran, Mali, Morocco, Côte d'Ivoire, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Chad, Pakistan and Yemen.[63]

In contrast, UNESCO notes that at 37% the share of female researchers in Arab states compares well with other regions.[65] In Turkey, the proportion of female university researchers is slightly higher (36%) than the average for the 27-member European Union as of 2012 (33%).[66] In Iran, women account for over 60% of university students.[67] Similarly, in Malaysia,[68] Algeria,[69] and in Saudi Arabia,[70] the majority of university students have been female in recent years, while in 2016 Emirati women constituted 76.8% of people enrolled at universities in the United Arab Emirates.[71] At the University of Jordan, which is Jordan's largest and oldest university, 65% of students were female in 2013.[72]

In a number of OIC member states, the ratio of women to men in tertiary education is exceptionally high. Qatar leads the world in this respect, having 6.66 females in higher education for every male as of 2015.[73] Other Muslim-majority states with notably more women university students than men include Kuwait, where 41% of females attend university compared with 18% of males;[73] Bahrain, where the ratio of women to men in tertiary education is 2.18:1;[73] Brunei Darussalam, where 33% of women enroll at university vis à vis 18% of men;[73] Tunisia, which has a women to men ratio of 1.62 in higher education; and Kyrgyzstan, where the equivalent ratio is 1.61.[73] Additionally, in Kazakhstan, there were 115 female students for every 100 male students in tertiary education in 1999; according to the World Bank, this ratio had increased to 144:100 by 2008.[74]

Female employment

Some scholars[75][76] refer to verse 28:23 in the Quran and to Khadijah, Muhammad's first wife, a merchant before and after converting to Islam, as indications that Muslim women may undertake employment outside their homes.

And when he came to the water of Madyan, he found on it a group of men watering, and he found besides them two women keeping back (their flocks). He said: What is the matter with you? They said: We cannot water until the shepherds take away (their sheep) from the water, and our father is a very old man.

Traditional interpretations of Islam require a woman to have her husband's permission to leave the house and take up employment.[77][78][79]

History

During medieval times, the labor force in Spanish Caliphate included women in diverse occupations and economic activities such as farming, construction workers, textile workers, managing slave girls, collecting taxes from prostitutes, as well as presidents of guilds, creditors, religious scholars.[80]

In the 12th century, Ibn Rushd, claimed that women were equal to men in all respects and possessed equal capacities to shine, citing examples of female warriors among the Arabs, Greeks and Africans to support his case.[81] In the early history of Islam, examples of notable female Muslims who fought during the Muslim conquests and Fitna (civil wars) as soldiers or generals included Nusaybah bint Ka'ab[82] a.k.a. Umm Amarah, Aisha,[83] Kahula and Wafeira.[84]

Medieval bimarestan or hospitals included female staff as female nurses. Muslim hospitals were also the first to employ female physicians, such as Banu Zuhr family who served the Almohad caliph ruler Abu Yusuf Yaqub al-Mansur in the 12th century.[85] This was necessary due to the segregation of male and female patients in Islamic hospitals. Later in the 15th century, female surgeons were employed at Şerafeddin Sabuncuoğlu's Cerrahiyyetu'l-Haniyye (Imperial Surgery).[86]

Modern era

Patterns of women's employment vary throughout the Muslim world: as of 2005, 16% of Pakistani women were "economically active" (either employed, or unemployed but available to furnish labor), whereas 52% of Indonesian women were.[90] According to a 2012 World Economic Forum report[91] and other recent reports,[92] Islamic nations in the Middle East and North Africa region are increasing their creation of economic and employment opportunities for women; compared, however, to every other region in the world, the Middle East and North African region ranks lowest on economic participation, employment opportunity and the political empowerment of women. Ten countries with the lowest women labour force participation in the world – Jordan, Oman, Morocco, Iran, Turkey, Algeria, Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan and Syria – are Islamic countries, as are the four countries that have no female parliamentarians.[91]

Women are allowed to work in Islam, subject to certain conditions, such as if a woman is in financial need and her employment does not cause her to neglect her important role as a mother and wife.[75][93] It has been claimed that it is the responsibility of the Muslim community to organize work for women, so that she can do so in a Muslim cultural atmosphere, where her rights (as set out in the Quran) are respected.[75] Islamic law however, permits women to work in Islamic conditions,[75] such as the work not requiring the woman to violate Islamic law (e.g., serving alcohol), and that she maintain her modesty while she performs any work outside her home.

In some cases, when women have the right to work and are educated, women's job opportunities may in practice be unequal to those of men. In Egypt for example, women have limited opportunities to work in the private sector because women are still expected to put their role in the family first, which causes men to be seen as more reliable in the long term.[94][page needed] In Saudi Arabia, it is illegal for Saudi women to drive, serve in military and other professions with men.[95][page needed] It is becoming more common for Saudi Arabian women to procure driving licences from other Gulf Cooperation Council states such as the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain.[96]

According to the International Business Report (2014) published by global accounting network Grant Thornton, Indonesia – which is the world's largest Muslim country by population – has ≥40% of senior business management positions occupied by women, a greater proportion than the United States (22%) and Denmark (14%).[97] Prominent female business executives in the Islamic world include Güler Sabancı, the CEO of the industrial and financial conglomerate Sabancı Holding;[98] Ümit Boyner, a non-executive director at Boyner Holding who was the chairwoman of TÜSİAD, the Turkish Industrialists and Businessmen Association, from 2010 to 2013;[99] Bernadette Ruth Irawati Setiady, the CEO of PT Kalbe Farma Tbk., the largest pharmaceutical company in the ASEAN trade bloc;[100] Atiek Nur Wahyuni, the director of Trans TV, a major free-to-air television station in Indonesia;[101] and Elissa Freiha, a founding partner of the UAE-based investment platform WOMENA.[102][103]

Financial and legal matters

According to all schools of Islamic law, the injunctions of the sharī'ah of Islam apply to all Muslims, male and female, who have reached the age of majority – and only to them.[30] All Muslims are in principle equal before the law.[104] The Qur'an especially emphasises that its injunctions concern both men and women in several verses where both are addressed clearly and in a distinct manner, such as in Sūrat al-Aḥzāb at 33:35 ('Verily, men who surrender unto God, and women who surrender...').

Most Muslim majority countries, and some Muslim minority countries, follow a mixed legal system, with positive laws and state courts, as well as sharia-based religious laws and religious courts.[105] Those countries that use Sharia for legal matters involving women, adopt it mostly for personal law; however, a few Islamic countries such as Saudi Arabia, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Yemen also have sharia-based criminal laws.[106]

According to Jan Michiel Otto, "[a]nthropological research shows that people in local communities often do not distinguish clearly whether and to what extent their norms and practices are based on local tradition, tribal custom, or religion."[107] In some areas, tribal practices such as vani, Ba'ad and "honor" killing remain an integral part of the customary legal processes involving Muslim women.[108][109] In turn, article 340 of the Jordanian Penal Code, which reduces sentences for killing female relatives over adultery, and is commonly believed to be derived from Islamic law, was in fact borrowed from French criminal law during the Ottoman era.[110]

Other than applicable laws to Muslim women, there is gender-based variation in the process of testimony and acceptable forms of evidence in legal matters.[111][112] Some Islamic jurists have held that certain types of testimony by women may not be accepted. In other cases, the testimony of two women equals that of one man.[111][112]

Financial and legal agency: The classical position

According to verse 4:32 of Islam's sacred text, both men and women have an independent economic position: 'For men is a portion of what they earn, and for women is a portion of what they earn. Ask God for His grace. God has knowledge of all things.'[113] Women therefore are at liberty to buy, sell, mortgage, lease, borrow or lend, and sign contracts and legal documents.[113] Additionally, women can donate money, act as trustees and set up a business or company.[113] These rights cannot be altered, irrespective of marital status.[113] When a woman is married, she legally has total control over the dower – the mahr or bridal gift, usually financial in nature, while the groom pays to the bride upon marriage – and retains this control in the event of divorce.[113][114]

Qur'anic principles, especially the teaching of zakāh or purification of wealth, encourage women to own, invest, save and distribute their earnings and savings according to their discretion.[113][page needed] These also acknowledge and enforce the right of women to participate in various economic activities.[113][page needed]

In contrast to many other cultures, a woman in Islam has always been entitled as per sharī'ah law to keep her family name and not take her husband's name.[115] Therefore, a Muslim woman has traditionally always been known by the name of her family as an indication of her individuality and her own legal identity: there is no historically practiced process of changing the names of women be they married, divorced or widowed.[115] With the spread of modern, western-style state bureaucracies across the Islamic world from the nineteenth century onwards, this latter convention has come under increasing pressure, and it is now commonplace for Muslim women to change their names upon marriage.

Property rights

Quran states:

"For men is a share from what the parents and near relatives leave, and for women is a share from what the parents and near relative leave from less from it or more, a legal share."

(Al-Quran 4:7)

Bernard Lewis says that classical Islamic civilization granted free Muslim women relatively more property rights than women in the West, even as it sanctified three basic inequalities between master and slave, man and woman, believer and unbeliever.[116] Even in cases where property rights were granted in the West, they were very limited and covered only upper class women.[117] Over time, while women's rights have improved elsewhere, those in many Muslim-dominated countries have remained comparatively restricted.[118][119]

Women's property rights in the Quran are from parents and near relatives. A woman, according to Islamic tradition, does not have to give her pre-marriage possessions to her husband and receive a mahr (dower) which she then owns.[120] Furthermore, any earnings that a woman receives through employment or business, after marriage, is hers to keep and need not contribute towards family expenses. This is because, once the marriage is consummated, in exchange for tamkin (sexual submission), a woman is entitled to nafaqa – namely, the financial responsibility for reasonable housing, food and other household expenses for the family, including the spouse, falls entirely on the husband.[77][78] In traditional Islamic law, a woman is also not responsible for the upkeep of the home and may demand payment for any work she does in the domestic sphere.[121]

Property rights enabled some Muslim women to possess substantial assets and fund charitable endowments. In mid-sixteenth century Istanbul, 36.8% of charitable endowments (awqāf) were founded by women.[122] In eighteenth century Cairo, 126 out of 496 charitable foundations (25.4%) were endowed by women.[123] Between 1770 and 1840, 241 out of 468 or 51% of charitable endowments in Aleppo were founded by women.[124]

The Qur'an grants inheritance rights to wife, daughter, and sisters of the deceased.[125] However, women's inheritance rights to her father's property are unequal to her male siblings, and varies based on number of sisters, stepsisters, stepbrothers, if mother is surviving, and other claimants. The rules of inheritance are specified by a number of Qur'an verses, including Surah "Baqarah" (chapter 2) verses 180 and 240; Surah "Nisa(h)" (chapter 4) verses 7–11, 19 and 33; and Surah "Maidah" (chapter 5), verses 106–108. Three verses in Surah "Nisah" (chapter 4), verses 11, 12 and 176, describe the share of close relatives. The religious inheritance laws for women in Islam are different from inheritance laws for non-Muslim women under common laws.[126]

Rape, adultery, and fornication

Zina

- Traditional jurisprudence

Zina is an Islamic legal term referring to unlawful sexual intercourse.[127] According to traditional jurisprudence, zina can include adultery (of married parties), fornication (of unmarried parties), prostitution, bestiality, and according to some scholars, rape.[127] The Quran disapproved of the promiscuity prevailing in Arabia at the time, and several verses refer to unlawful sexual intercourse, including one that prescribes the punishment of 100 lashes for fornicators.[128] Zina thus belong to the class of hadd (pl. hudud) crimes which have Quranically specified punishments.[128]

Although stoning for zina is not mentioned in the Quran, all schools of traditional jurisprudence agreed on the basis of hadith that it is to be punished by stoning if the offender is muhsan (adult, free, Muslim, and having been married), with some extending this punishment to certain other cases and milder punishment prescribed in other scenarios.[128][127] The offenders must have acted of their own free will.[128] According to traditional jurisprudence, zina must be proved by testimony of four four adult, pious male eyewitnesses to the actual act of penetration, or a confession repeated four times and not retracted later.[128][127] Any Muslim who accuses another Muslim of zina but fails to produce the required witnesses commits the crime of false accusation (qadhf, القذف).[129][130][131] Some contend that this sharia requirement of four eyewitnesses severely limits a man's ability to prove zina charges against women, a crime often committed without eyewitnesses.[129][132][133] The Maliki legal school also allows an unmarried woman's pregnancy to be used as evidence, but the punishment can be averted by a number of legal "semblances" (shubuhat), such as existence of an invalid marriage contract.[128] These requirements made zina virtually impossible to prove in practice.[127]

- History

Aside from "a few rare and isolated" instances from the pre-modern era and several recent cases, there is no historical record of stoning for zina being legally carried out.[127] Zina became a more pressing issue in modern times, as Islamist movements and governments employed polemics against public immorality.[127] After sharia-based criminal laws were widely replaced by European-inspired statutes in the modern era, in recent decades several countries passed legal reforms that incorporated elements of hudud laws into their legal codes.[134] Iran witnessed several highly publicized stonings for zina in the aftermath the Islamic revolution.[127] In Nigeria local courts have passed several stoning sentences, all of which were overturned on appeal or left unenforced.[135] While the harsher punishments of the Hudood Ordinances have never been applied in Pakistan,[136] in 2005 Human Rights Watch reported that over 200,000 zina cases against women were underway at various levels in Pakistan's legal system.[137]

Rape

- Traditional jurisprudence

Rape is considered a serious sexual crime in Islam, and can be defined in Islamic law as: "Forcible illegal sexual intercourse by a man with a woman who is not legally married to him, without her free will and consent".[138] Sharī'ah law makes a distinction between adultery and rape and applies different rules.[139] According to Professor Oliver Leaman, the required testimony of four male witnesses having seen the actual penetration applies to illicit sexual relations (i.e. adultery and fornication), not to rape.[140] The requirements for proof of rape are less stringent:

Rape charges can be brought and a case proven based on the sole testimony of the victim, providing that circumstantial evidence supports the allegations. It is these strict criteria of proof which lead to the frequent observation that where injustice against women does occur, it is not because of Islamic law. It happens either due to misinterpretation of the intricacies of the Sharia laws governing these matters, or cultural traditions; or due to corruption and blatant disregard of the law, or indeed some combination of these phenomena.[140]

In the case of rape, the adult male perpetrator (i.e. rapist) of such an act is to receive the ḥadd zinā, but the non-consenting or invalidly consenting female (i.e. rape victim) is to be regarded as innocent of zinā and relieved of the ḥadd punishment.[141]

- Modern criminal laws

Rape laws in a number of Muslim-majority countries have been a subject of controversy. In some of these countries, such as Morocco, the penal code is neither based on Islamic law nor significantly influenced by it,[142] while in other cases, such as Pakistan's Hudood Ordinances, the code incorporates elements of Islamic law.

In Afghanistan, Dubai, Morocco and Pakistan, some women who made accusations of rape have been charged with fornication or adultery.[143][144][145][146] This law was amended in Pakistan in 2006.[147]

In several countries, including Morocco ( - 2014), Jordan ( - 2017), Lebanon, Algeria, Afghanistan and Pakistan, rapists have been allowed to avoid criminal prosecution if they married their victim.[148][149][150] There is a disagreement whether this practice is sanctioned by Islam or part of local custom.[151][152][need quotation to verify]

Witness of woman

In Qur'an, surah 2:182 equates two women as substitute for one man, in matters requiring witnesses.[153]

O ye who believe! When ye contract debt with each other for a fixed period of time, reduce them to writing. Let a scribe write down faithfully as between the parties: let not the scribe refuse to write: as Allah has taught him, so let him write. Let him who incurs the liability dictate, but let him fear His Lord Allah, and not diminish aught of what he owes. If they party liable is mentally deficient, or weak, or unable himself to dictate, let his guardian dictate faithfully, and get two witnesses, out of your own men, and if there are not two men, then a man and two women, such as ye choose, for witnesses, so that if one of them errs, the other can remind her. The witnesses should not refuse when they are called on (For evidence). Disdain not to reduce to writing (your contract) for a future period, whether it be small or big: it is juster in the sight of Allah, More suitable as evidence, and more convenient to prevent doubts among yourselves but if it be a transaction which ye carry out on the spot among yourselves, there is no blame on you if ye reduce it not to writing.

Narrated Abu Sa'id Al-Khudri:

The prophet said,"Isn't the witness of a woman equal to half of that of a man?" The women said, "Yes". He said, " This is deficiency of her mind".

(Sahih Bukhari: Book of Witnesses: Chapter witness of women: Hadith no. 2658)

In Islamic law, testimony (shahada) is defined as attestation of knowledge with regard to a right of a second party against a third. It exists alongside other forms of evidence, such as the oath, confession, and circumstantial evidence.[154]

In classical Shari'a criminal law men and women are treated differently with regard to evidence and bloodmoney. The testimony of a man has twice the strength of that of a woman. However, with regard to hadd offences and retaliation, the testimonies of female witnesses are not admitted at all.[112] A number of Muslim-majority countries, particularly in the Arab world, presently treat a woman's testimony as half of a man's in certain cases, mainly in family disputes adjudicated based on Islamic law.[155]

Classical commentators commonly explained the unequal treatment of testimony by asserting that women's nature made them more prone to error than men. Muslim modernists have followed the Egyptian reformer Muhammad Abduh in viewing the relevant scriptural passages as conditioned on the different gender roles and life experiences that prevailed at the time rather than women's innately inferior mental capacities, making the rule not generally applicable in all times and places.[156]

Domestic breach

Discussions on the topic of domestic violence and Islam tend to centre on part of a single verse of the Qur'an – the thirty-fourth ayat of Sūrat an-Nisāʼ (4:34) – which has been claimed to permit mild physical discipline of a wife[citation needed] as a last resort in the event of 'disloyalty', such as an extra-marital affair or similar phenomenon.

Men have authority over women by [right of] what Allah has given one over the other and what they spend [for maintenance] from their wealth. So righteous women are devoutly obedient, guarding in [the husband's] absence what Allah would have them guard. But those [wives] from whom you fear arrogance – [first] advise them; [then if they persist], forsake them in bed; and [finally], strike them. But if they obey you [once more], seek no means against them. Indeed, Allah is ever Exalted and Grand. If you fear a breach between them then appoint an arbiter from his folks and an arbiter from her folks; if they desire reconciliation God will affect between them; indeed God is All-knowing All-aware (Al-Quran, An-Nisa, 34-35)

Firstly, the word "strike" in this verse which is understood as "beating" or "hitting" in English – w'aḍribūhunna – is derived from the Arabic root word ḍaraba, which has over fifty derivations and definitions, including "to separate', "to oscillate" and "to play music".[158] Even within the Qur'an itself, the most common use[where?] of this word is not with the definition "to beat", but as verb phrases which provide a number of other meanings, including several which are more plausible within the context of 4:34, such as "to leave [your wife in the event of disloyalty]", and "to draw them lovingly towards you [following temporarily not sleeping with them in protest at their disloyal behaviour]".[159]

Secondly, accepting physical violence – no matter how symbolic – as a legitimate marital disciplinary tool is perceived as being contradictory to the ethos of marriage as described in the Qur'an: (i) according to 30:21, one of God's signs is the creation of the "love and mercy" between married couples which is meant to characterise this type of relationship; and (ii) at 4:19, men are exhorted to "consort with their wives in kindness".[non-primary source needed]

Sharī'ah law addresses domestic violence through the concept of darar or harm that encompasses several types of abuse against a spouse, including physical abuse. The laws concerning darar state that if a woman is being harmed in her marriage, she can have it annulled: physically assaulting a wife violates the marriage contract and is grounds for immediate divorce.[160][unreliable source?]

Sharī'ah court records from the Ottoman period illustrate the ability of women to seek justice when subject to physical abuse: as a notable 1687 case from Aleppo demonstrates, courts gave out penalties such as corporal punishment to abusive husbands.[160]

A sixteenth-century fatwa issued by the Şeyhülislam (Shaykh al-Islam, the highest religious authority in the jurisdiction) of the Ottoman Empire stated that in the event of a judge becoming aware of serious spousal abuse, he has the legal authority to prevent the husband hurting his wife "by whatever means possible", including ordering their separation (at the request of the wife).[160]

In recent years, numerous prominent scholars in the tradition of Orthodox Islam have issued fatwas (legal opinions) against domestic violence. These include the Shī'ite scholar Mohammed Hussein Fadlallah, who promulgated a fatwa on the occasion of the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women in 2007, which states that Islam forbids men from exercising any form of violence against women;[161] Shakyh Muhammad Hisham Kabbani, the Chairman of the Islamic Supreme Council of America, who co-authored The Prohibition of Domestic Violence in Islam (2011) with Dr. Homayra Ziad;[162] and Cemalnur Sargut, the president of the Turkish Women's Cultural Association (TÜRKKAD), who has stated that men who engage in domestic violence "in a sense commit polytheism (shirk)".[163]

Some scholars[164][165] claim Islamic law, such as verse 4:34 of Quran, allows and encourages domestic violence against women, when a husband suspects nushuz (disobedience, disloyalty, rebellion, ill conduct) in his wife.[166] Other scholars claim wife beating, for nashizah, is not consistent with modern perspectives of Quran,.[167]

Some conservative translations suggest Muslim husbands are permitted to use light force on their wives, and others claim permissibility to strike, hit, chastise, or beat.[168][169] The relationship between Islam and domestic violence is disputed by some Islamic scholars.[168][170]

The Lebanese educator and journalist 'Abd al-Qadir al-Maghribi argued that perpetrating acts of domestic violence goes against Muḥammad's own example and injunction. In his 1928 essay, Muḥammad and Woman, al-Maghribi said: "He [Muḥammad] prohibited a man from beating his wife and noted that beating was not appropriate for the marital relationship between them".[171] Muḥammad underlined the moral and logical inconsistency in beating one's wife during the day and then praising her at night as a prelude to conjugal relations.[171] The Austrian scholar and translator of the Qur'an Muhammad Asad (Leopold Weiss) said: It is evident from many authentic traditions that the Prophet himself intensely detested the idea of beating one's wife...According to another tradition, he forbade the beating of any woman with the words, "Never beat God's handmaidens."'[172]

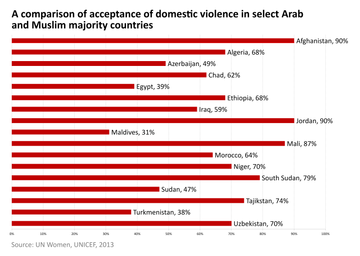

In practice, the legal doctrine of many Islamic nations, in deference to Sharia law, have refused to include, consider or prosecute cases of domestic violence, limiting legal protections available to Muslim women.[173][174][175][176] In 2010, for example, the highest court of United Arab Emirates (Federal Supreme Court) considered a lower court's ruling, and upheld a husband's right to "chastise" his wife and children with physical violence. Article 53 of the United Arab Emirates' penal code acknowledges the right of a "chastisement by a husband to his wife and the chastisement of minor children" so long as the assault does not exceed the limits prescribed by Sharia.[177] In Lebanon, as many as three-quarters of all Lebanese women have suffered physical abuse at the hands of husbands or male relatives at some point in their lives.[178][179] In Afghanistan, over 85% of women report domestic violence;[180] other nations with very high rates of domestic violence and limited legal rights include Syria, Pakistan, Egypt, Morocco, Iran, Yemen and Saudi Arabia.[181] In some Islamic countries such as Turkey, where legal protections against domestic violence have been enacted, serial domestic violence by husband and other male members of her family is mostly ignored by witnesses and accepted by women without her getting legal help, according to a Government of Turkey report.[182]

Turkey was the first country in Europe to ratify (on 14 March 2012) the Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence,[183] which is known as the Istanbul Convention because it was first opened for signature in Turkey's largest city (on 11 May 2011).[184] Three other European countries with a significant (≥c.20%) Muslim population – Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro – have also ratified the convention, while Macedonia is a signatory to the document.[185] The aim of the convention is to create a Europe free from violence against women and domestic violence.[186]

Love

Among classical Muslim authors, the notion of love was developed along three conceptual lines, conceived in an ascending hierarchical order: natural love, intellectual love and divine love.[187]

Romantic love

In traditional Islamic societies, love between men and women was widely celebrated,[190] and both the popular and classical literature of the Muslim world is replete with works on this theme. Throughout Islamic history, intellectuals, theologians and mystics have extensively discussed the nature and characteristics of romantic love ('ishq).[187] In its most common intellectual interpretation of the Islamic Golden Age, ishq refers to an irresistible desire to obtain possession of the beloved, expressing a deficiency that the lover must remedy in order to reach perfection.[187] Like the perfections of the soul and the body, love thus admits of hierarchical degrees, but its underlying reality is the aspiration to the beauty which God manifested in the world when he created Adam in his own image.[187]

The Arab love story of Lāyla and Majnūn was arguably more widely known amongst Muslims than that of Romeo and Juliet in (Northern) Europe,[190] while Jāmī's retelling of the story of Yusuf (Joseph) and Zulaykhā — based upon the narrative of Surat Yusuf in the Qur'an — is a seminal text in the Persian, Urdu and Bengali literary canons. The growth of affection (mawadda) into passionate love (ishq) received its most probing and realistic analysis in The Ring of the Dove by the Andalusian scholar Ibn Hazm.[187] The theme of romantic love continues to be developed in the modern and even postmodern fiction from the Islamic world: The Black Book (1990) by the Nobel Prize winner Orhan Pamuk is a nominal detective story with extensive meditations on mysticism and obsessive love, while another Turkish writer, Elif Şafak, intertwines romantic love and Sufism in her 2010 book The Forty Rules of Love: A Novel of Rumi.[191]

In Islamic mysticism or Sufism, romantic love is viewed as a metaphysical metaphor for the love of God. However, the importance of love extends beyond the metaphorical: ibnʿArabī, who is widely recognised as the 'greatest of spiritual masters [of Sufism]', posited that for a man, sex with a woman is the occasion for experiencing God's 'greatest self-disclosure' (the position is similar vice versa):[192]

The most intense and perfect contemplation of God is through women, and the most intense union is the conjugal act.'[193]

This emphasis on the sublimity of the conjugal act holds true for both this world and the next: the fact that Islam considers sexual relationships one of the ultimate pleasures of paradise is well-known; moreover, there is no suggestion that this is for the sake of producing children.[194] Accordingly, (and in common with civilisations such as the Chinese, Indian and Japanese), the Islamic world has historically generated significant works of erotic literature and technique, and many centuries before such a genre became culturally acceptable in the West: Richard Burton's substantially ersatz 1886 translation of The Perfumed Garden of Sensual Delight, a fifteenth-century sex manual authored by Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad al-Nafzawi, was labelled as being 'for private circulation only' owing to the puritanical mores and corresponding censorship laws of Victorian England.[195]

Love of women

Particularly within the context of religion – a domain which is often associated with sexual asceticism – Muḥammad is notable for emphasising the importance of loving women. According to a famous ḥadīth, Muḥammad stated: "Three things of this world of yours were made lovable to me: women, perfume – and the coolness of my eye was placed in the ritual prayer".[196] This is enormously significant because in the Islamic faith, Muḥammad is by definition the most perfect human being and the most perfect male: his love for women shows that the perfection of the human state is connected with love for other human beings, not simply with love for God.[196] More specifically, it illustrates that male perfection lies in women and, by implication, female perfection in men.[196] Consequently, the love Muḥammad had for women is obligatory on all men, since he is the model of perfection that must be emulated.[197]

There is a Hadith quoting,

"There is nothing better for two who love each other than marriage."[198]

Prominent figures in Islamic mysticism have elaborated on this theme. Ibn 'Arabī reflected on the above ḥadīth as follows: "….he [Muḥammad] mentioned women [as one of three things from God's world made lovable to him]. Do you think that which would take him far from his Lord was made lovable to him? Of course not. That which would bring him near to his Lord was made lovable to him.

"He who knows the measure of women and their mystery will not renounce love for them. On the contrary, one of the perfections of the gnostic is love for them, for this is a prophetic heritage and a divine love. For the Prophet said, '[women] were made lovable to me.' Hence he ascribed his love for them only to God. Ponder this chapter – you will see wonders!"[197]

Ibn 'Arabī held that witnessing God in the female human form is the most perfect mode of witnessing: if the Prophet Muḥammad was made to love women, it is because women reflect God.[199] Rūmī came to a similar conclusion: "She [woman] is the radiance of God, she is not your beloved. She is the Creator – you could say that she is not created."[199][200]

According to Gai Eaton, there are several other ḥadīths on the same theme which underline Muḥammad's teaching on the importance of loving women:

- "You should cherish your woman from the perfume of her hair to the tips of her toes."[201]

- "The best of you is the one who is best to his wife."[202]

- "The whole world is to be enjoyed, but the best thing in the world is a good woman."[203]

Marriage

Metaphysical and cosmological significance of marriage

The metaphysical and cosmological significance of marriage within Islam – particularly within Sufism or Islamic mysticism – is difficult to overstate. The relationship and interplay between male and female is viewed as nothing less than that between heaven (represented by the husband) and earth (symbolised by the wife).[204][additional citation(s) needed] Because of her beauty and virtue, the earth is eminently lovable: heaven marries her not simply out of duty, but for pleasure and joy.[204] Marriage and sexual intercourse are not merely human phenomena, but the universal power of productivity found within every level of existence: sex within marriage is the supreme instance of witnessing God in the full splendour of His self-disclosure.[205][additional citation(s) needed]

Legal framework

Marriage is the central institution of family life and society, and therefore the central institution of Islam.[206] On a technical level, it is accomplished through a contract which is confirmed by the bride's reception of a dowry or mahr, and by the witnessing of the bride's consent to the marriage.[207] A woman has the freedom to propose to a man of her liking, either orally or in writing.[208] The Prophet Muḥammad himself was the subject of a spoken marriage proposal from a Muslim lady which was worded "I present myself to you", although ultimately Muḥammad solemnized her marriage to another man.[209]

Within the marriage contract itself, the bride has the right to stipulate her own conditions.[210] These conditions usually pertain to such issues as marriage terms (e.g. that her husband may not take another wife), and divorce terms (e.g. that she may dissolve the union at her own initiative if she deems it necessary).[210] In addition, dowries – one on marriage, and another deferred in case of divorce – must be specified and written down; they should also be of substance.[210] The dowry is the exclusive property of the wife and should not be given away, neither to her family nor her relatives.[210] According to the Qur'an (at 4:2), the wife may freely choose to give part of their dowry to the husband.[210] Fiqh doctrine says a woman's property, held exclusively in her name cannot be appropriated by her husband, brother or father.[211] For many centuries, this stood in stark contrast with the more limited property rights of women in (Christian) Europe.[211] Accordingly, Muslim women in contemporary America are sometimes shocked to find that, even though they were careful to list their assets as separate, these can be considered joint assets after marriage.[211]

Marriage ceremony and celebrations

When agreement to the marriage has been expressed and witnessed, those present recite the fātiḥah prayer (the opening chapter of the Qur'an).[207] Normally, marriages are not contracted in mosques but in private homes or at the offices of a judge (qāḍi).[207] The format and content of the ceremony (if there is one) is often defined by national or tribal customs, as are the celebrations ('urs) that accompany it.[207] In some parts of the Islamic world these may include processions in which the bride gift is put on display; receptions where the bride is seen adorned in elaborate costumes and jewellery; and ceremonial installation of the bride in the new house to which she may be carried in a litter (a type of carriage).[207] The groom may ride through the streets on a horse, followed by his friends and well-wishers, and there is always a feast called the walīmah.[207]

Historical commonality of divorce

In contrast to the Western and Orient world where divorce was relatively uncommon until modern times, divorce was a more common occurrence in certain parts of the late medieval Muslim world. In the Mamluk Sultanate and Ottoman Empire, the rate of divorce was high.[212][213] The work of the scholar and historian Al-Sakhawi (1428-1497) on the lives of women show that the marriage pattern of Egyptian and Syrian urban society in the fifteenth century was greatly influenced by easy divorce, and practically untouched by polygamy.[214][215] Earlier Egyptian documents from the eleventh to thirteenth centuries also showed a similar but more extreme pattern: in a sample of 273 women, 118 (45%) married a second or third time.[215] Edward Lane's careful observation of urban Egypt in the early nineteenth century suggests that the same regime of frequent divorce and rare polygamy was still applicable in these last days of traditional society.[215] In the early 20th century, some villages in western Java and the Malay peninsula had divorce rates as high as 70%.[212]

Polygamy

Marriage customs vary in Muslim dominated countries. Islamic law allows polygamy where a Muslim man can be married to four wives at the same time, under restricted conditions,[216] but it is not widespread.[217] As the Sharia demands that polygamous men treat all wives equally, classical Islamic scholars opined that it is preferable to avoid polygamy altogether, so one does not even come near the chance of committing the forbidden deed of dealing unjustly between the wives.[218] Most modern Muslims view the practice of polygamy as allowed, but unusual and not recommended.[219] In some countries, polygamy is restricted by new family codes, for example the Moudawwana in Morocco.[220] Some countries allow Muslim men to enter into additional temporary marriages, beyond the four allowed marriages, such as the practice of sigheh marriages in Iran,[221] and Nikah Mut'ah elsewhere in some Middle East countries.[222][223]

A marriage of pleasure, where a man pays a sum of money to a woman or her family in exchange for a temporary spousal relationship, is found and considered legal among Shia sect of Islam, for example in Iran after 1979. Temporary marriages are forbidden among Sunni sect of Islam.[224] Among Shia, the number of temporary marriages can be unlimited, for a duration that is less than an hour to few months, recognized with an official temporary marriage certificate, and divorce is unnecessary because the temporary marriage automatically expires on the date and time specified on the certificate.[225] Payment to the woman by the man is mandatory, in every temporary marriage and considered as mahr.[226][227] Its practitioners cite sharia law as permitting the practise. Women's rights groups have condemned it as a form of legalized prostitution.[228][229]

Polyandry

Polyandry, the practice of a woman having more than one husband (even temporarily, after payment of a sum of money to the man or the man's family), by contrast, is not permitted.[230][231]

Endogamy

Endogamy is common in Islamic countries. The observed endogamy is primarily consanguineous marriages, where the bride and the groom share a biological grandparent or other near ancestor.[236][237] The most common observed marriages are first cousin marriages, followed by second cousin marriages. Consanguineous endogamous marriages are most common for women in Muslim communities in the Middle East, North Africa and Islamic Central Asia.[238][239] About 1 in 3 of all marriages in Saudi Arabia, Iran and Pakistan are first cousin marriages; while overall consanguineous endogamous marriages exceed 65 to 80% in various Islamic populations of the Middle East, North Africa and Islamic Central Asia.[237][240]

Forbidden marriages

Do not marry women your fathers married to except that has passed; Indeed it was lewdness, disobedience and bad way. Prohibited to you are your mothers, your daughters, your sisters, your paternal aunts, your maternal aunts, brother's daughters, sister's daughters, your suckling-mothers, your sisters from suckling, mothers of your women, your stepdaughters in your guardianship from your women you have entered into them but if you have not entered into them then there is no blame on you, women of your sons from your loins and that you add two sisters (in a wedlock) except that has passed; surely God is All-forgiving and all-merciful.

Some marriages are forbidden between Muslim women and Muslim men, according to sharia.[241] In the Quran, Surah An-Nisa gives a list of forbidden marriages.[Quran 4:22] Examples include marrying one's stepson, biological son, biological father, biological brother, biological sibling's son, biological uncle, milk son or milk brother she has nursed, husband of her biological daughter, and a stepfather who has had sexual relations with her biological mother and father-in-law.[242][243] There are disputes between Hanafis, Malikis, Shafi'is and Hanabalis schools of Sunni Islamic jurisprudence on whether and which such marriages are irregular but not void if already in place (fasid), and which are void (batil) marriages.[244]

Age of marriage

Child marriage, which was once a globally accepted phenomenon, has come to be discouraged in most countries, but it persists to some extent in most parts of the Muslim world.[245] Islam is one of several major faiths whose teachings have been used to justify marriage of girls.[246]

The age of marriage in Islam for women varies with country. Traditionally, Islam has permitted marriage of girls below the age of 10, because Sharia considers practices of Muhammad as a basis for Islamic law. According to Sahih Bukhari and Sahih Muslim, the two Sunni hadiths, Muhammed married Aisha, his third wife when she was 6, and consummated the marriage when she reached the age of 9 or 10. (This version of events is rejected by Shia Muslims.)[247][248]

Narrated 'Aisha: that the Prophet married her when she was six years old and he consummated his marriage when she was nine years old, and then she remained with him for nine years (i.e., till his passing away).

Some Islamic scholars suggest that it is not the calendar age that matters, rather it is the biological age of the girl that determines when she can be married under Islamic law. According to these Islamic scholars, marriageable age in Islam is when a girl has reached sexual maturity, as determined by her nearest male guardian; this age can be, claim these Islamic scholars, less than 10 years, or 12, or another age depending on each girl.[245][249]

Some clerics and conservative elements of Muslim communities in Yemen,[250][251] Saudi Arabia,[252] India,[253][254] Bangladesh, Pakistan,[255] Indonesia,[256] Egypt,[257] Nigeria[258] and elsewhere have insisted that it is their Islamic right to marry girls below age 15.[259]

Interfaith marriages and Muslim women

According to sharī'ah law, it is legal for a Muslim man to marry a Christian or Jewish woman, or a woman of any of the divinely-revealed religions.[207] A female does not have to convert from Christianity or Judaism to Islam in order to marry a Muslim male.[260] While sharī'ah law does not allow a Muslim woman to marry outside her religion,[207] a significant number of non-Muslim men have entered into the Islamic faith in order to satisfy this aspect of the religious law where it is in force.[207] With deepening globalisation, it has become more common for Muslim women to marry non-Muslim men who remain outside Islam.[207][261] These marriages meet with varying degrees of social approval, depending on the milieu.[207] However, conversions of non-Muslim men to Islam for the purpose of marriage are still numerous, in part because the procedure for converting to Islam is relatively expeditious.[262]

Behaviour and rights within marriage

Islamic law and practice recognize gender disparity, in part, by assigning separate rights and obligations to a woman in married life. A woman's space is in the private sphere of the home, and a man's is in the public sphere.[263][264] Women must primarily fulfill marital and maternal responsibilities,[265] whereas men are financial and administrative stewards of their families.[263][266] According to Sayyid Qutb, the Qur'an "gives the man the right of guardianship or superiority over the family structure in order to prevent dissension and friction between the spouses. The equity of this system lies in the fact that God both favoured the man with the necessary qualities and skills for the 'guardianship' and also charged him with the duty to provide for the structure's upkeep."[267]

The Quran considers the love between men and women to be a Sign of God.[Quran 30:21] This said, the Quran also permits men to first admonish, then lightly tap or push and even beat her, if he suspects nushuz (disobedience, disloyalty, rebellion, ill conduct) in his wife.[166][Quran 4:34][268]

In Islam, there is no coverture, an idea central in European, American as well as in non-Islamic Asian common law, and the legal basis for the principle of marital property. An Islamic marriage is a contract between a man and a woman. A Muslim man and woman do not merge their legal identity upon marriage, and do not have rights over any shared marital property. The assets of the man before the marriage, and earned by him after the marriage, remain his during marriage and in case of a divorce.[269] A divorce under Islamic law does not require redistribution of property. Rather, each spouse walks away from the marriage with his or her individual property. Divorcing Muslim women who did not work outside their home after marriage do not have a claim on the collective wealth of the couple under Islamic law, except for deferred mahr – an amount of money or property the man agrees to pay her before the woman signs the marriage contract.[93][270]

Quran states

And for you is half of what your wives left, if they do not have child; and if they have child yours is one-fourth of what they left; after the will they have bequeteth or debt. And for them is one fourth of what you leave, if you do not have child; but if you have child theirs is one-eighth; after the will you have bequeteth or debt. And if the man or woman, inherited from, is Kalalah(childless) and; he has brother or sister, for each of them is one-sixth; And if they are more than it they will share one-third; after the will he bequetteth or untroubling debt. It is ordianance from God; and God is All-knowing and Allbearing.

{Al-Quran 4:12}

In case of husband's death, a portion of his property is inherited by his wives according to a combination of sharia laws. If the man did not leave any children, his wives receive a quarter of the property and the remaining three quarters is shared by the blood relatives of the husband (for example, parents, siblings).[271] If he had children from any of his wives, his wives receive an eighth of the property and the rest is for his surviving children and parents.[271] The wives share as inheritance a part of movable property of her late husband, but they do not share anything from immovable property [citation needed] such as land, real estate, farm or such value. A woman's deferred mahr and the dead husband's outstanding debts are paid before any inheritance is applied.[272] Sharia mandates that inheritance include male relatives of the dead person, that a daughter receive half the inheritance as a son, and a widow receives less than her daughters.[272][273][better source needed]

Sexuality

In Islam, a Muslim woman can only have sex after her "nikah" – a proper marriage contract – with one Muslim man; sex is permitted to her only with her husband.[129][274][275] The woman's husband, may however, marry and have sex with more than one Muslim woman, as well as have sex with non-Muslim slaves.[130][274][276] According to Quran and Sahih Muslim, two primary sources of Sharia, Islam permits only vaginal sex.[277]

(…) "If he likes he may (have intercourse) being on the back or in front of her, but it should be through one opening (vagina)."

There is disagreement among Islamic scholars on proper interpretation of Islamic law on permissible sex between a husband and wife, with claims that non-vaginal sex within a marriage is disapproved but not forbidden.[277][278][279] Anal intercourse and sex during menstruation are prohibited, as is violence and force against a partner's will.[280] However, these are the only restrictions; as the Qur'an says at 2:223 (Sūratu l-Baqarah): 'Your women are your fields; go to your women as you wish'.[280]

After sex, as well as menstruation, Islam requires men and women to do ghusl (major ritual washing with water, ablutions), and in some Islamic communities xoslay (prayers seeking forgiveness and purification), as sex and menstruation are considered some of the causes that makes men and women religiously impure (najis).[281][282] Some Islamic jurists suggest touching and foreplay, without any penetration, may qualify wudu (minor ritual washing) as sufficient form of religiously required ablution.[283] A Muslim men and woman must also abstain from sex during a ritual fast, and during all times while on a pilgrimage to Mecca, as sexual act, touching of sexual parts and emission of sexual bodily fluids are considered ritually dirty.[284]

Sexual intercourse is not allowed to a Muslim woman during menstruation, postpartum period, during fasting and certain religious activities, disability and in iddah after divorce or widowhood. Homosexual relations and same sex marriages are forbidden to women in Islam.[278] In vitro fertilization (IVF) is acceptable in Islam; but ovum donation along with sperm donation, embryo donation and child adoption are prohibited by Islam.[277] These marriages meet with varying degrees of social approval, depending on the milieu./>[285][286] Some debated fatwas from Shia sect of Islam, however, allow third party participation.[287][288]

Islam requires both husband and wife/wives to meet their conjugal duties. Religious qadis (judges) have admonished the man or women who fail to meet these duties.[289]

A high value is placed on female chastity and exhibitionism is prohibited.[290]

Female genital mutilation

The classical position

There is no mention of female circumcision – let alone other forms of female genital mutilation – in the Qur'an. Furthermore, Muḥammad did not subject any of his daughters to this practice, which is itself of real significance as it does not form part of his spoken or acted example.[293] Moreover, the origins of female circumcision are not Islamic: it is first thought to have been practiced in ancient Egypt.[294] Alternatively, it has been suggested that the practice may be an old African puberty rite that was passed on to Egypt by cultural diffusion.[295]

Notwithstanding these facts, there is a belief amongst some Muslims – particularly though not entirely exclusively in (sub-Saharan) Africa – that female circumcision (specifically the cutting of the prepuce or hood of the clitoris) is religiously vindicated by the existence of a handful of ḥadīths which apparently recommend it.[294] However, these ḥadīths are generally regarded as inauthentic, unreliable and weak, and therefore as having no legislative foundation and/or practical application.[296]

Notable Islamic perspectives on FGM

In answering the question of how "Islamic" female circumcision is, Haifaa A. Jawad – an academic specialising in Islamic thought and the author of The Rights of Women in Islam: An Authentic Approach – has concluded that "the practice has no Islamic foundation whatsoever. It is nothing more than an ancient custom which has been falsely assimilated to the Islamic tradition, and with the passage of time it has been presented and accepted (in some Muslim countries) as an Islamic injunction."[297] Jawad notes that the argument which states that there is an indirect correlation between Islam and female circumcision fails to explain why female circumcision is not practiced in much of the Islamic world, and conversely is practiced in Latin American countries such as Brazil, Mexico and Peru.[298][299]

The French intellectual, journalist and translator Renée Saurel observed that female circumcision and FGM more generally directly contradict Islam's sacred text: "The Koran, contrary to Christianity and Judaism, permits and recommends that the woman be given physical and psychological pleasure, pleasure found by both partners during the act of love. Forcibly split, torn, and severed tissues are neither conducive to sensuality nor to the blessed feeling given and shared when participating in the quest for pleasure and the escape from pain."[300]