Linux: Difference between revisions

| [pending revision] | [pending revision] |

m Reverted 1 edit by 69.203.202.49 to last revision by Yamla. using TW |

|||

| Line 186: | Line 186: | ||

* [http://www.linuxmark.org/ The Linux Mark Institute] (manages the Linux trade mark) |

* [http://www.linuxmark.org/ The Linux Mark Institute] (manages the Linux trade mark) |

||

* [http://www.linux-foundation.org/ The Linux Foundation] |

* [http://www.linux-foundation.org/ The Linux Foundation] |

||

* [http://www.linuxhaxor.net/ Hacking with Linux] |

|||

{{unix-like}} |

{{unix-like}} |

||

Revision as of 19:48, 6 September 2007

Tux, the penguin, mascot of the Linux kernel | |

| OS family | Unix-like |

|---|---|

| Working state | Current |

| Latest release | 2.6.22.6 (Linux kernel) / August 31 2007 |

| Kernel type | Monolithic kernel |

| License | Kernel: GNU General Public License/various |

| Official website | kernel |

Linux (IPA pronunciation: /ˈlɪnʊks/) is a Unix-like computer operating system. Linux is one of the most prominent examples of free software and open source development; its underlying source code can be freely modified, used, and redistributed by anyone.[1]

The Linux kernel was first released to the public on 17 September 1991, for the Intel x86 PC architecture. The kernel was augmented with system utilities and libraries from the GNU project to create a usable operating system, which later led to the alternate term GNU/Linux.[2] Linux is now packaged for different uses in Linux distributions, which contain the sometimes modified kernel along with a variety of other software packages tailored to different requirements.

Predominantly known for its use in servers, Linux has gained the support of corporations such as IBM, Sun Microsystems, Dell, Hewlett-Packard and Novell, and is used as an operating system for a wide variety of computer hardware, including desktop computers, supercomputers,[3], video game systems (PlayStation 2 and 3 for example) and embedded devices such as mobile phones and routers.

History

The Unix operating system was conceived and implemented in the 1960s and first released in 1970. Its wide availability and portability meant that it was widely adopted, copied and modified by academic institutions and businesses, with its design being influential on authors of other systems. One so-called Unix-like system was GNU, started in 1984, which had the goal of creating a POSIX-compatible operating system from entirely free software. In 1985, Richard Stallman created the Free Software Foundation and developed the GNU General Public License (GNU GPL), in order to spread the software freely. Many of the programs required in an OS (such as libraries, compilers, text editors, a Unix shell, and a GUI) were developed by the early 1990s, so that most of the requirements for an operating system were complete, although low level elements such as device drivers, daemons, and the kernel were stalled and incomplete.[4] Linus Torvalds has said that if the GNU kernel had been available at the time, he would not have decided to write his own.[5]

MINIX, a Unix-like system intended for academic use, was released by Andrew S. Tanenbaum in 1987. While source code for the system was available, modification and redistribution were restricted. In addition, MINIX's 16-bit design was not well adapted to the 32-bit design of the increasingly cheap and popular Intel 386 architecture for personal computers.

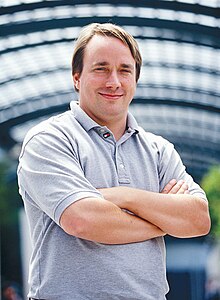

In 1991, Linus Torvalds began to work on a non-commercial replacement for MINIX while he was attending the University of Helsinki.[6] This eventually became the Linux kernel.

Linux was dependent on the Minix userspace at first. With code from the GNU system freely available, it was advantageous if this could be used with the fledgling OS. Code licensed under the GNU GPL can be used in other projects, so long as they also are released under the same or a compatible license. In order to make the Linux kernel compatible with the components from the GNU Project, Torvalds initiated a switch from his original license (which prohibited commercial redistribution) to the GNU GPL.[7] Linux and GNU developers worked to integrate GNU components with Linux to make a fully functional and free operating system.[4]

Today Linux is used in numerous domains, from embedded systems[8] to supercomputers,[9] and has secured a place in server installations with the popular LAMP application stack.[10] Torvalds continues to direct the development of the kernel. Stallman heads the Free Software Foundation, which in turn develops the GNU components. Finally, individuals and corporations develop third-party non-GNU components. These third-party components comprise a vast body of work and may include both kernel modules and user applications and libraries. Linux vendors and communities combine and distribute the kernel, GNU components, and non-GNU components, with additional package management software in the form of Linux distributions.

Ownership

The Linux kernel and most GNU software are licensed under the GNU General Public License (GPL), version 2. The GPL requires that anyone who distributes the Linux kernel must make the source code (and any modifications) available to the recipient under the same terms. In 1997, Linus Torvalds stated, “Making Linux GPL'd was definitely the best thing I ever did.”[11] Other key components of a Linux system may use other licenses; many libraries use the GNU Lesser General Public License (LGPL), a more permissive variant of the GPL, and the X Window System uses the MIT License.

Torvalds has publicly stated that he would not move the Linux kernel to version 3 of the GPL, released in mid-2007, specifically citing some provisions in the new license which prohibit the use of the software in digital rights management.[12][13]

In March 2003, the SCO Group filed a lawsuit against IBM, claiming that IBM had contributed parts of SCO's copyrighted code to the Linux kernel, violating IBM's license to use Unix. Also, SCO sent letters to several companies warning that their use of Linux without a license from SCO may be actionable, and claimed in the press that they would be suing individual Linux users. Per the Utah District Court ruling on July 3, 2006; 182 out of 294 items of evidence provided by SCO against IBM in discovery were dismissed.[14]

In 2004, Ken Brown, president of the Alexis de Tocqueville Institution, published Samizdat, a highly controversial book which, among other criticism of open source software, denied Torvalds' authorship of the Linux kernel (attributing it to Tanenbaum, instead). This was rebutted by Tanenbaum himself.[15][16]

In the United States, the name Linux is a trademark registered to Linus Torvalds.[17] Initially, nobody registered it, but on August 15 1994, William R. Della Croce, Jr. filed for the trademark Linux, and then demanded royalties from Linux distributors. In 1996, Torvalds and some affected organizations sued to have the trademark assigned to Torvalds, and in 1997 the case was settled.[18] The licensing of the trademark has since been handled by the Linux Mark Institute. Torvalds has stated that he only trademarked the name to prevent someone else from using it, but was bound in 2005 by United States trademark law to take active measures to enforce the trademark. As a result, the LMI sent out a number of letters to distribution vendors requesting that a fee be paid for the use of the name, and a number of companies have complied.[19]

Development

A 2001 study of Red Hat Linux 7.1 found that this distribution contained 30 million source lines of code. Using the Constructive Cost Model, the study estimated that this distribution required about eight thousand man-years of development time. According to the study, if all this software had been developed by conventional proprietary means, it would have cost about 1.08 billion dollars (year 2000 U.S. dollars) to develop in the United States.[20]

Most of the code (71%) was written in the C programming language, but many other languages were used, including C++, Lisp, assembly language, Perl, Fortran, Python and various shell scripting languages. Slightly over half of all lines of code were licensed under the GPL. The Linux kernel itself was 2.4 million lines of code, or 8% of the total.[20]

In a later study, the same analysis was performed for Debian GNU/Linux version 2.2.[21] This distribution contained over fifty-five million source lines of code, and the study estimated that it would have cost 1.9 billion dollars (year 2000 U.S. dollars) to develop by conventional means.

Programming on Linux

Most Linux distributions support dozens of programming languages. The most common collection of utilities for building both Linux applications and operating system programs is found within the GNU toolchain, which includes the GNU Compiler Collection (GCC) and the GNU build system. Amongst others, GCC provides compilers for C, C++, Java, Ada and Fortran. The Linux kernel itself is written to be compiled with GCC.

Most also include support for Perl, Ruby, Python and other dynamic languages. Examples of languages that are less common, but still well-supported, are C# via the Mono project, and Scheme. A number of Java Virtual Machines and development kits run on Linux, including the original Sun Microsystems JVM (HotSpot), and IBM's J2SE RE, as well as many open-source projects like Kaffe. The two main frameworks for developing graphical applications are those of GNOME and KDE. These projects are based on the GTK+ and Qt widget toolkits, respectively, which can also be used independently of the larger framework. Both support a wide variety of languages. There are a number of Integrated development environments available including Anjuta, Code::Blocks, Eclipse, KDevelop, Ultimate++, MonoDevelop, NetBeans, and Omnis Studio while the traditional editors Vim and Emacs remain popular.[22]

Although free and open source compilers and tools are widely used under Linux, there are also proprietary solutions available from a range of companies, including the Intel C++ Compiler, PathScale, Micro Focus COBOL, Franz Inc and the Portland Group.

Philosophy

The primary difference between Linux and many other popular contemporary operating systems is that the Linux kernel and other components are free and open source software. Linux is not the only such operating system, although it is the most well-known and widely used one. Some free and open source software licences are based on the principle of copyleft, a kind of reciprocity: any work derived from a copyleft piece of software must also be copyleft itself. The most common free software license, the GNU GPL, is used for the Linux kernel and many of the components from the GNU project.

Interoperability

As an operating system underdog competing with mainstream operating systems, Linux cannot rely on a monopoly advantage; in order for Linux to be convenient for users, Linux aims for interoperability with other operating systems and established computing standards. Linux systems adhere to POSIX,[23] SUS,[24] ISO, and ANSI standards where possible, although to date only one Linux distribution has been POSIX.1 certified, Linux-FT.[25]

Portability

Linux is a widely ported operating system. While the Linux kernel was originally designed only for Intel 80386 microprocessors, it now runs on a more diverse range of computer architectures than any other operating system—from the hand-held ARM-based iPAQ to the mainframe IBM System z9, in devices ranging from supercomputers to mobile phones.[26] Specialized distributions exist for less mainstream architectures. The ELKS kernel fork can run on Intel 8086 or Intel 80286 16-bit microprocessors, while the µClinux kernel may run on systems without a memory management unit. The kernel also runs on architectures that were only ever intended to use a manufacturer-created operating system, such as Macintosh computers, PDAs, Video game consoles, portable music players, and Mobile phones.

Community

Linux is largely driven by its developer and user communities. Some vendors develop and fund their distributions on a volunteer basis, Debian being a well-known example. Others maintain a community version of their commercial distributions, as RedHat does with Fedora.

In many cities and regions, local associations known as Linux Users Groups (LUGs) seek to promote Linux and by extension free software. They hold meetings and provide free demonstrations, training, technical support, and operating system installation to new users. There are also many internet communities that seek to provide support to Linux users and developers. Most distributions and open source projects have IRC chatrooms or newsgroups. Online forums are another means for support, with notable examples being LinuxQuestions.org and the Gentoo forums. Linux distributions host mailing lists; commonly there will be a specific topic such as usage or development for a given list.

There are several technology websites with a Linux focus. Linux Weekly News is a weekly digest of Linux-related news; the Linux Journal is an online magazine of Linux articles published monthly; Slashdot is a technology-related news website with many stories on Linux and open source software; Groklaw has written in depth about Linux-related legal proceedings; and there are many articles relevant to the Linux kernel and its relationship with the GNU on the project's website.

Although Linux is generally available free of charge, several large corporations have established business models that involve selling, supporting, and contributing to Linux and free software. These include Dell, IBM, HP, Sun Microsystems, Novell, and Red Hat. The free software licenses on which Linux is based explicitly accommodate and encourage commercialization; the relationship between Linux as a whole and individual vendors may be seen as symbiotic. One common business model of commercial suppliers is charging for support, especially for business users. A number of companies also offer a specialized business version of their distribution, which adds proprietary support packages and tools to administer higher numbers of installations or to simplify administrative tasks. Another business model is to give away the software in order to sell hardware.

The XO laptop project of One Laptop Per Child is creating a new and potentially much larger Linux community, planned to reach several hundred million schoolchildren and their families and communities in developing countries. Six countries have ordered a million or more units each for delivery in 2007 to distribute to schoolchildren at no charge. Google, Red Hat, and eBay are major supporters of the project.

Distribution

Free software projects, although developed in a collaborative fashion, are often produced independently of each other. However, given that the software licenses explicitly permit redistribution, this provides a basis for larger scale projects that collect the software produced by stand-alone projects and make it available all at once in the form of a Linux distribution.

A Linux distribution, commonly called a “distro”, is a project that manages a remote collection of Linux-based software, and facilitates installation of a Linux operating system. Distributions are maintained by individuals, loose-knit teams, volunteer organizations, and commercial entities. They include system software and application software in the form of packages, and distribution-specific software for initial system installation and configuration as well as later package upgrades and installs. A distribution is responsible for the default configuration of installed Linux systems, system security, and more generally integration of the different software packages into a coherent whole.

As well as those designed for general purpose use on desktops and servers, distributions may be specialized for different purposes including: computer architecture support, embedded systems, stability, security, localization to a specific region or language, targeting of specific user groups, support for real-time applications, or commitment to a given desktop environment. Furthermore, some distributions deliberately include only free software. Currently, over three hundred distributions are actively developed, with about a dozen distributions being most popular for general-purpose use.[27]

Naming

The correct pronunciation of "Linux" has long been disputed.[28] In 1992, Torvalds explained that he pronounces it as /ˈlɪnʊks/. [29]

The Free Software Foundation views Linux distributions which use GNU software as “GNU variants” and they ask that such operating systems be referred to as GNU/Linux or a Linux-based GNU system.[30] However, the media and population at large refers to this family of operating systems simply as Linux. While some distributors make a point of using the aggregate form, most notably Debian with the Debian GNU/Linux distribution, the term's use outside of the enthusiast community is limited. The distinction between the Linux kernel and distributions based on it plus the GNU system is a source of confusion to many newcomers, and the naming remains controversial.

User interface

Linux is coupled to a text-based command line interface (CLI), though this is usually hidden on desktop computers by a graphical environment. On small devices, input may be handled through controls on the device itself, and direct input to Linux might be hidden entirely.

Command line interface

Linux systems usually provide a CLI of some sort through a shell, the traditional way of interacting with Unix systems. Even on modern desktop machines, some form of CLI is almost always accessible. Linux distributions specialized for servers may use the CLI as their only interface, and Linux machines can run without a monitor attached. Such “headless systems” may be controlled by command line via a protocol such as SSH or telnet.

Most low-level Linux components, including the GNU userland, use the CLI exclusively. The CLI is particularly suited for automation of repetitive or delayed tasks, and provides very simple inter-process communication. Graphical terminal emulator programs can be used to access the CLI from a Linux desktop.

Graphical interfaces

The X Window System (X) is the predominant graphical subsystem used in Linux. X provides network transparency, enabling graphical output to be displayed on machines other than that which a program runs on. For desktop machines X runs locally.

Early GUIs for Linux were based on a stand-alone X window manager such as FVWM, Enlightenment, or Window Maker, and a suite of diverse applications running under it. The window manager provides a means to control the placement and appearance of individual application windows, and interacts with the X window system. Because the X window managers only manage the placement of windows, their decoration, and some inter-process communication, the look and feel of individual applications may vary widely, especially if they use different graphical user interface toolkits.

This model contrasts with that of platforms such as Mac OS, where a single toolkit provides support for GUI widgets and window decorations, manages window placement, and otherwise provides a consistent look and feel to the user. For this reason, the use of window managers by themselves declined with the rise of Linux desktop environments. They combine a window manager with a suite of standard applications that adhere to human interface guidelines. While a window manager is analogous to the Aqua user interface for Mac OS X, a desktop environment is analogous to Aqua with all of the default Mac OS X graphical applications and configuration utilities. KDE, which was announced in 1996, along with GNOME and Xfce which were both announced in 1997, are the most popular desktop environments.[31]

Applications

Desktop

Although in specialized application domains such as desktop publishing and professional audio there may be a lack of commercial quality software, users migrating from Mac OS X and Windows can find equivalent applications for most tasks.[32]

Many free software titles that are popular on Windows are also available, such as Pidgin, Mozilla Firefox, Openoffice.org, and GIMP, amongst others. A growing amount of proprietary desktop software is also supported under Linux,[33] examples being Adobe Flash Player, Acrobat Reader, Nero Burning ROM, Opera, RealPlayer, and Skype. In the field of animation and visual effects, most high end software, such as AutoDesk Maya, Softimage XSI and Apple Shake are available both for Linux, Windows and/or MacOS X. Additionally, CrossOver is a commercial solution based on the open source WINE project that supports running Windows versions of Microsoft Office and Photoshop.

Servers and supercomputers

Historically, Linux has mainly been used as a server operating system, and has risen to prominence in that area; Netcraft reported in September 2006 that eight of the ten most reliable internet hosting companies run Linux on their web servers.[34] This is due to its relative stability and long uptime, and the fact that desktop software with a graphical user interface is often unneeded. Enterprise and non-enterprise Linux distributions may be found running on servers. Linux is the cornerstone of the LAMP server-software combination (Linux, Apache, MySQL, Perl/PHP/Python) which has achieved popularity among developers, and which is one of the more common platforms for website hosting.

Linux is commonly used as an operating system for supercomputers. As of June 2007, out of the top 500 systems, 389 (77.8%) run Linux.[35]

Embedded devices

Due to its low cost and ability to be easily modified, an embedded Linux is often used in embedded systems. Linux has become a major competitor to the proprietary Symbian OS found in many mobile phones — 16.7% of smartphones sold worldwide during 2006 were using Linux[36] — and it is an alternative to the dominant Windows CE and Palm OS operating systems on handheld devices. The popular TiVo digital video recorder uses a customized version of Linux.[37] Several network firewall and router standalone products, including several from Linksys, use Linux internally, using its advanced firewall and routing capabilities. The Korg OASYS and the Yamaha Motif XS music workstations also run Linux.[38]

Market share and uptake

Many quantitative studies of open source software focus on topics including market share and reliability, with numerous studies specifically examining Linux.[39] The Linux market is growing rapidly, and the revenue of servers, desktops, and packaged software running Linux is expected to exceed $35.7 billion by 2008.[40] According to market research company IDC, 25% of servers and 2.8% of desktop computers ran Linux as of 2004.[41]

The difficulty of measuring the exact number of deployments becomes apparent when looking at IDC's report for Q1 2007, which says that Linux now holds 12.7% of the overall server market.[42] This estimate was based on the number of Linux servers sold by various companies. However, since most Linux distributions do not require a separate license for each copy, this number says nothing about the actual market share of the operating system, just how much money companies are making from selling it.

It has been alleged that people regard Linux as suitable mostly for computer experts because mainstream computer magazine reporters cannot explain what Linux is in a meaningful way, as they lack real life experience using it.[43] Furthermore, the frictional cost of switching operating systems and lack of support for certain hardware and application programs designed for Microsoft Windows have been two factors that have inhibited adoption. However, as of early 2007, significant progress in hardware compatibility has been made, and it is becoming increasingly common for hardware to work “out of the box” with many Linux distributions. Proponents and analysts attribute the relative success of Linux to its security, reliability,[44] low cost, and freedom from vendor lock-in.[45]

See also

- List of Linux distributions

- Comparison of Linux distributions

- Comparison of Windows and Linux

- Comparison of open source and closed source

- List of Linux magazines

- The Cathedral and the Bazaar

- Linux software

References

- ^ "Linux Online ─ About the Linux Operating System". Linux.org. Retrieved 2007-07-06.

- ^ Weeks, Alex (2004). "1.1". Linux System Administrator's Guide (version 0.9 ed.). Retrieved 2007-01-18.

- ^ Lyons, Daniel. "Linux rules supercomputers". Retrieved 2007-02-22.

- ^ a b http://www.gnu.org/gnu/gnu-history.html

- ^ "Linus vs. Tanenbaum debate".

- ^ Torvalds, Linus. "What would you like to see most in minix?". Newsgroup: comp.os.minix. 1991Aug25.205708.9541@klaava.Helsinki.FI. Retrieved 2006-09-09.

- ^ Torvalds, Linus (1992-01-05). "RELEASE NOTES FOR LINUX v0.12". Linux Kernel Archives. Retrieved 2007-07-23.

The Linux copyright will change: I've had a couple of requests to make it compatible with the GNU copyleft, removing the "you may not distribute it for money" condition. I agree. I propose that the copyright be changed so that it confirms to GNU ─ pending approval of the persons who have helped write code. I assume this is going to be no problem for anybody: If you have grievances ("I wrote that code assuming the copyright would stay the same") mail me. Otherwise The GNU copyleft takes effect as of the first of February. If you do not know the gist of the GNU copyright ─ read it.

- ^ Santhanam, Anand (1 March 2002). "Linux system development on an embedded device". DeveloperWorks. IBM. Retrieved 2007-07-26.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Lyons, Daniel. "Linux rules supercomputers". Retrieved 2007-02-22.

- ^ Schrecker, Michael. "Turn on Web Interactivity with LAMP". Retrieved 2007-02-22.

- ^ "Linus Torvalds interview". Retrieved 2006-05-08.

- ^ Torvalds, Linus (2006-01-26). "Re: GPL V3 and Linux ─ Dead Copyright Holders". Linux Kernel Mailing List.

- ^ Torvalds, Linus (2006-09-25). "Re: GPLv3 Position Statement". Linux Kernel Mailing List.

- ^ "SCO Losing Linux Battle With IBM".

- ^ Tannenbaum, Andrew S. "Some notes on the "Who wrote Linux" Kerfuffle". Retrieved 2006-06-26.

- ^ Tannenbaum, Andrew S. "Source comparison of early linux and minix versions". Retrieved 2007-05-11.

- ^ "U.S. Reg No: 1916230". United States Patent and Trademark Office. Retrieved 2006-04-01.

- ^ "Linux Timeline". Linux Journal. 31 May 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Linus gets tough on Linux trademark". 2005-09-05. Retrieved 2006-09-04.

- ^ a b Wheeler, David A (2002-07-29). "More Than a Gigabuck: Estimating GNU/Linux's Size". Retrieved 2006-05-11.

- ^ González-Barahona, Jesús M (3 January 2002). "Counting potatoes: The size of Debian 2.2". Retrieved 2006-05-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Brockmeier, Joe. "A survey of Linux Web development tools". Retrieved 2006-12-16.

- ^ "POSIX.1 (FIPS 151-2) Certification".

- ^ "How source code compatible is Debian with other Unix systems?". Debian FAQ. the Debian project.

- ^ "Certifying Linux".

- ^ Advani, Prakash (February 8 2004). "If I could re-write Linux". freeos.com. Retrieved 2007-01-23.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "The LWN.net Linux Distribution List". Retrieved 2006-05-19.

- ^ "List of words of disputed pronunciation". Retrieved 2007-03-12.

- ^ "Re: How to pronounce "Linux"?". 23 April 1992. 1992Apr23.123216.22024@klaava.Helsinki.FI.

{{cite newsgroup}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|newsgroups=ignored (help) Torvalds has made available an audio sample which indicates his own pronunciation, in English (/ˈlɪnʊks/) ─ "How to pronounce Linux?". Retrieved 2006-12-17. ─ and Swedish (/ˈlɪːnɤks/) ─ "Linus pronouncing Linux in English and Swedish". Retrieved 2007-01-20. - ^ Stallman, Richard (2007-03-03). "Linux and the GNU Project". Free Software Foundation. Retrieved 2007-03-12.

- ^ "Debian popularity-contest program information".

- ^ "The table of equivalents/replacements/analogs of Windows software in Linux".

- ^ "The Global Desktop Project, Building Technology and Communities". Retrieved 2006-05-07.

- ^ "Rackspace Most Reliable Hoster in September". Netcraft. October 7 2006. Retrieved 2006-11-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ http://www.top500.org/stats/list/29/osfam

- ^ "The Palm OS Clings To Life".

- ^ "TiVo ─ GNU/Linux Source Code". Retrieved 2006-12-12.

- ^ "Case Study: How MontaVista Linux helped Yamaha developers make a great product greater" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-08-26.

- ^ Wheeler, David A. "Why Open Source Software/Free Software (OSS/FS)? Look at the Numbers!". Retrieved 2006-04-01.

- ^ "Linux To Ring Up $35 Billion By 2008". Retrieved 2006-04-01.

- ^ White, Dominic (2004-04-02). "Microsoft eyes up a new kid on the block". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2006-09-09. The estimate of these numbers is driven by website traffic analysis, which may be inaccurate due to user agent string manipulation. "A Note on User Agent Identifiers and Browser Statistics".

- ^ Linux-watch.com ─ IDC Q1 2007 report

- ^ Linux Online ─ Getting Started with Linux ─ Lesson 1 (2)

- ^ "Why customers are flocking to Linux".

- ^ "The rise and rise of Linux".

External links

- Linux kernel website and archives

- The Linux Mark Institute (manages the Linux trade mark)

- The Linux Foundation