Militant atheism: Difference between revisions

| Line 93: | Line 93: | ||

Dawkins has responded to criticisms that he is hostile towards religion, saying "such hostility as I or other atheists occasionally voice toward religion is limited to words" and "It is all too easy to confuse fundamentalism with passion. I may well appear passionate when I defend evolution against a fundamentalist creationist, but this is not because of a rival fundamentalism of my own."<ref>http://www.beliefnet.com/Faiths/Secular-Philosophies/Why-I-Am-Hostile-Toward-Religion.aspx</ref> |

Dawkins has responded to criticisms that he is hostile towards religion, saying "such hostility as I or other atheists occasionally voice toward religion is limited to words" and "It is all too easy to confuse fundamentalism with passion. I may well appear passionate when I defend evolution against a fundamentalist creationist, but this is not because of a rival fundamentalism of my own."<ref>http://www.beliefnet.com/Faiths/Secular-Philosophies/Why-I-Am-Hostile-Toward-Religion.aspx</ref> |

||

==Criticism== |

|||

===General=== |

|||

[[Melanie Phillips]], a British author, suggests that militant atheism "in junking religion, has destroyed our sense of anything beyond our material selves and the here and now" and "paved the way for the onslaught on bedrock moral values ... and intimidation and bullying to drive this agenda into public policy".<ref name="Phillips">{{Cite web|url=http://www.spectator.co.uk/melaniephillips/2447021/the-culture-war-for-the-white-house.thtml|author=[[Melanie Phillips]]|title=The culture war for the White House|publisher=[[The Spectator]]|quote=I see this financial breakdown, moreover, as being not merely a moral crisis but the monetary expression of the broader degradation of our values – the erosion of duty and responsibility to others in favour of instant gratification, unlimited demands repackaged as ‘rights’ and the loss of self-discipline. And the root cause of that erosion is ‘militant atheism’ which, in junking religion, has destroyed our sense of anything beyond our material selves and the here and now and, through such hyper-individualism, paved the way for the onslaught on bedrock moral values expressed through such things as family breakdown and mass fatherlessness, educational collapse, widespread incivility, unprecedented levels of near psychopathic violent crime, epidemic drunkenness and drug abuse, the repudiation of all authority, the moral inversion of victim culture, the destruction of truth and objectivity and a corresponding rise in credulousness in the face of lies and propaganda -- and intimidation and bullying to drive this agenda into public policy.|date=16 October 2008|accessdate=2007-12-31}}</ref> |

|||

[[Simon Blackburn]] writes that "many professional philosophers, including ones such as myself who have no religious beliefs at all, are slightly embarrassed, or even annoyed, by the voluble disputes between militant atheists and [[Christian apologetics|religious apologists]]".<ref name="Blackburn">{{Cite web|url=http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/story.asp?storycode=405647|author=[[Simon Blackburn]]|title=Divine Irony|publisher=[[Times Higher Education (THE)]]|quote=I suspect that many professional philosophers, including ones such as myself who have no religious beliefs at all, are slightly embarrassed, or even annoyed, by the voluble disputes between militant atheists and religious apologists.|date=5 March 2009|accessdate=2007-12-31}}</ref> |

|||

===Humanism=== |

|||

[[Paul Kurtz]], considered by many to be the founder of secular [[humanism]],<ref name="Humanism">{{cite book |

|||

|url=http://www.pointofinquiry.org/paul_kurtz_the_new_atheism_and_secular_humanism/ |

|||

|title=The New Atheism and Secular Humanism|publisher=Center for Inquiry|quote=Paul Kurtz, considered by many the father of the secular humanist movement, is Professor Emeritus of Philosophy at the State University of New York at Buffalo. |

|||

|date=19 October 2009}}</ref> has criticized militant atheists in that "they resist any effort to engage in inquiry or debate" and militant atheism as "becom[ing] mere [[dogma]]."<ref name="KurtzCriticism">{{cite book |

|||

|author=Paul Kurtz, Vern L. Bullough, Tim Madigan|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=e9OJSW5dkM8C&pg=PA250&dq=militant+atheist+deaths&hl=en&ei=Sqb3TfnGAebX0QGHqJ3gDA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCkQ6AEwADgK#v=onepage&q&f=false |

|||

|title=Toward a New Enlightenment: the Philosophy of Paul Kurtz |

|||

|publisher=Transaction Books |

|||

|quote=Ranged against the true believer are the militant atheists, who adamantly reject the faith as false stupid, and reactionary. They consider all religious believers to be gullbile fools and claim that they are given to accepting gross exaggerations and untenable premises. Historic religious claims, they think, are totally implausbile, unbelievable, disreputable, and controvertible, for they go beyond the bounds of reason. Militant atheists can find no value at all to any religious beliefs or institutions. They resist any effort to engage in inquiry or debate. Madalyn Murray O'Hair is as arrogant in her rejection of religion as is the true believer in his or her profession of faith. This form of atheism thus becomes mere dogma.|date=19 October 2009}}</ref> Kurtz has criticized the militant atheism of the Soviet Union, which he stated "persecuted religious beleivers, confiscated church properties, executed or exiled tens of thousands of clerics, and prohibited believers to engage in religious instruction or publish religious materials" and praised [[Mikhail Gorbachev]]'s "dismantling such policies by permitting greater freedom of religious conscience...moving from militant atheism to tolerant humanism."<ref name="Tolerance">{{cite book|author=Paul Kurtz, Vern L. Bullough, Tim Madigan|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=e9OJSW5dkM8C&pg=PA250&dq=militant+atheist+deaths&hl=en&ei=Sqb3TfnGAebX0QGHqJ3gDA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCkQ6AEwADgK#v=onepage&q&f=false|title=Toward a New Enlightenment: the Philosophy of Paul Kurtz|publisher=Transaction Books|quote=In the past, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union waged unremmitting warfare against religion. It persecute religious beleivers, confiscated church properties, executed or exiled tens of thousands of clerics, and prohibited believers to engage in religious instruction or publish religious materials. It has also carried on militant pro-atheist propaganda campaigns as part of the official ideology of the state, in an effort to establish a "new Soviet man" commited to the ideals of Communist society. Mikhail Gorbachev is dismantling such policies by permitting greater freedom of religious conscience. If his reforms proceed unabated, they could have dramatic implications for the entire Communist world, for the Russians may be moving from militant atheism to tolerant humanism.|date=19 October 2009}}</ref> Kurtz cited the commitment to "human freedom and democracy" as [[humanism|humanism's]] basic difference from the militant atheism of the Soviet Union, which consistently violated basic [[human rights]].<ref name="Rights">{{cite book|author=Paul Kurtz, Vern L. Bullough, Tim Madigan|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=e9OJSW5dkM8C&pg=PA250&dq=militant+atheist+deaths&hl=en&ei=Sqb3TfnGAebX0QGHqJ3gDA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCkQ6AEwADgK#v=onepage&q&f=false|title=Toward a New Enlightenment: the Philosophy of Paul Kurtz|publisher=Transaction Books|quote=There have been fundamental and irreconcilable differences between humanists and atheists, particularly Marxist-Leninists. The defining characteristic of humanism is its commitment to human freedom and democracy; the kind of atheism practiced in the Soviet Union has consistently violated basic human rights. Humanists believe first and foremost in the freedom of conscience, the free mind, and the right of dissent. The defense of religious liberty is as precious to the humanist as are the rights of the believers. |

|||

|date=19 October 2009}}</ref> Kurtz also stated that the "defense of religious liberty is as precious to the humanist as are the rights of the believers."<ref name="Rights"/> |

|||

===Terms=== |

|||

[[Catherine Fahringer]] of the [[Freedom From Religion Foundation]] suggested that the label ''militant'' was often routinely applied to ''atheist'' for no good reason – "very much as was the adjective 'damn' attached to the noun 'Yankee' during the Civil War."<ref>Catherine Fahringer, [http://ffrf.org/fttoday/1997/october97/fahringer.html The militant atheist], ''Freethought Today'', October 1997.</ref> The linguist [[Larry Trask]] suggests that the word ''militant'' "is used all too freely in the feebler sense of 'holding or expressing views which are unpopular or which I don't like'." He notes that Richard Dawkins is "accused by tabloid newspapers and other commentators of being a 'militant atheist'", for saying he doesn't like religion. However, according to Trask, activity engaged in by some Christians, such as knocking on strangers' doors "demanding to talk about the Bible", never seems to "draw forth the label 'militant'." Trask concludes, "if you find yourself writing this word, stop and think whether it has any clear meaning, or whether you are just using it as a swearword."<ref>"Militant", in Trask, R.L. (2001). ''Mind the gaffe: the Penguin guide to common errors in English.'' London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-051476-7, pp. 186–187.</ref> |

[[Catherine Fahringer]] of the [[Freedom From Religion Foundation]] suggested that the label ''militant'' was often routinely applied to ''atheist'' for no good reason – "very much as was the adjective 'damn' attached to the noun 'Yankee' during the Civil War."<ref>Catherine Fahringer, [http://ffrf.org/fttoday/1997/october97/fahringer.html The militant atheist], ''Freethought Today'', October 1997.</ref> The linguist [[Larry Trask]] suggests that the word ''militant'' "is used all too freely in the feebler sense of 'holding or expressing views which are unpopular or which I don't like'." He notes that Richard Dawkins is "accused by tabloid newspapers and other commentators of being a 'militant atheist'", for saying he doesn't like religion. However, according to Trask, activity engaged in by some Christians, such as knocking on strangers' doors "demanding to talk about the Bible", never seems to "draw forth the label 'militant'." Trask concludes, "if you find yourself writing this word, stop and think whether it has any clear meaning, or whether you are just using it as a swearword."<ref>"Militant", in Trask, R.L. (2001). ''Mind the gaffe: the Penguin guide to common errors in English.'' London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-051476-7, pp. 186–187.</ref> |

||

Revision as of 19:07, 10 July 2011

| Part of a series on |

| Atheism |

|---|

Militant atheism is a controversial term which can mean any of the following: 1) Strong atheism. 2) The view that certain religions are harmful (see antitheism or antireligion). 3) The application of violence (or the threat of violence) in suppressing certain religions, in order to protect people from their alleged harmfulness.

British philosopher Julian Baggini describes an atheist's hostility to religion as militant and says that this hostility "requires more than just strong disagreement with religion — it requires something verging on hatred and is characterized by a desire to wipe out all forms of religious belief." Militant atheists, Baggini continues, "tend to make one or both of two claims that moderate atheists do not. The first is that religion is demonstrably false or nonsense, and the second is that it is usually or always harmful."[1]

Militant atheism was an integral part of the materialism of Marxism-Leninism,[2][3] and significant in the French Revolution,[4] atheist states such as the Soviet Union,[5][6] and Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution.[7] According to Baggini, the "too-zealous" militant atheism found in the Soviet Union was characterized by thinking the best way to counter religion was "by oppression and making atheism the official state credo."[8]

Recently the term militant atheist[9][10][11][12] has been used, frequently pejoratively, to describe leaders of the New Atheism movement.

The term militant atheist has been used going back to at least 1894.[13]

Soviet Bloc

Militant atheism was effectively the state religion of the Soviet Union, with the Communist Party functioning as an established church.[2][3][14] The militant atheism of the Bolsheviks owed its origins not just to the "standard Marxist feeling that religion was the opium of the masses", but also to the fact that the Russian Orthodox Church had "always been a pillar of czarism."[15] The goal of the Soviet Union was the liquidation of religion and the means to achieve this goal included the destruction of churches, mosques, madrasahs, religious monuments, as well the mass deportation to Siberia of believers of different religions.[5][6][16] Under the Soviet doctrine of separation of church and state, detailed in the Constitution of the Soviet Union, churches in the Soviet Union were forbidden to give to the poor or carry on educational activities.[17] They could not publish literature since all publishing was done by state agencies, although after World War II the Russian Orthodox Church was given the right to publish church calendars, a very limited number of Bibles, and a monthly journal in a limited number of copies.[17] Churches were forbidden to hold any special meetings for children, youth or women, or any general meetings for religious study or recreation, or to open libraries or keep any books other than those necessary for the performance of worship services.[17][18][19] Furthermore, under militant atheist policies, Church property was expropriated.[14][20] Moreover, not only was religion banned from the school and university system, but pupils were to be indoctrinated with atheism and antireligious teachings.[21][22][23] For example, schoolchildren were asked to convert family members to atheism and memorize antireligious rhymes, songs, and catechisms, while university students who declined to propagate atheism lost their scholarships and were expelled from universities.[22] Severe criminal penalties were imposed for violation of these rules.[17][24] By the 1960s, with the fourth Soviet anti-religious campaign underway, half of the amount of Russian Orthodox churches were closed, along with five out of the eight seminaries.[25] In addition, several other Christian denominations were brought to extinction, including the Baptist Church, Methodist Church, Evangelical Christian Church, and the Evangelical Lutheran Church.[26][27] Before the Russian Revolution, there were more than fifty thousand Orthodox Christian clergymen, but by 1939, there were no more than three to four hundred left.[28] In the year 1922 alone, under the militant atheistic system, 2691 secular priests, 1962 monks and 3447 nuns were martyred for their faith.[29][30] Marxist-Leninist militant atheism resulted in the administrative elimination of the clergy, the housing of atheist museums where churches had once stood, the sending of many religious people to prisons and concentration camps, a continuous stream of propaganda, and the imposing of atheism through education (and forced re-education through torture at various prisons).[31][32][33][34] Specifically, by 1941, 40,000 Christian churches and 25,000 Muslim mosques had been closed down and converted into schools, cinemas, clubs, warehouses and grain stores, or Museums of Scientific Atheism.[35][36]

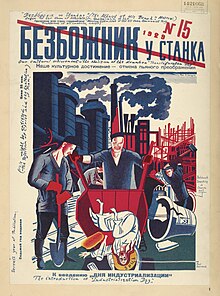

Oscar J. Hammen, an American historian, classified Engels as a militant atheist,[37] although the Soviet professor, N. Lobkowicz, challenged the assertion that Marx was a militant atheist.[38] The ascent of the Bolsheviks to power in 1917 "meant the beginning of a campaign of militant atheism."[39] and in 1922 Lenin referred with approval to "militant atheist literature" and demanded that the journal Pod Znamenem Marksizma "must be a militant atheist organ", explaining that he meant militant 'in the sense of unflinchingly exposing and indicting all modern “graduated flunkeys of clericalism”, irrespective of whether they act as representatives of official science or as free lances calling themselves “democratic Left or ideologically socialist” publicists'.[40] In 1923, the Bezbozhnik ("Atheist", or "Godless") magazine appeared,[41] around which the "Union of the Friends of the Bezbozhnik" was formed in 1924. The organization, renamed the League of Militant Atheists (Russian: Союз воинствующих безбожников, Soyuz voinstvuyushchikh bezbozhnikov) in 1929, along with the Tatar Union of the Militant Godless,[42] carried out anti-religious propaganda at the grassroots level.[43][44][45] In 1941, soon after the Nazi invasion of the USSR, the newspaper closed, and in 1947 the society itself folded, the task of the anti-religious propaganda being transferred to the more neutrally named All-Union Society for the Dissemination of Political and Scientific Knowledge (Всесоюзное общество по распространению политических и научных знаний).[46] Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, a Soviet concentration camp survivor, wrote of the The Union of the Militant Godless, stating that its members "went on rampages, blew out candles, and smashed icons with axes."[47] The society in its turn was in 1963 renamed to simply Obshchestvo "Znanie" (Общество "Знание", The All-Union Knowledge Society).[48] Since 1959 the society has published a monthly journal called Nauka i Religya (Science and Religion) which, during the Soviet era, described itself as "a fighting organ of militant atheism", rejecting the view that religion would disappear of itself. In 1961 the Ukrainian branch produced a similar journal called Militant Atheist (Voivnichy Ateist).[49]

In general, scientists and party philosophers in the Soviet Union worked to establish a view of science acceptable to Marxist-Leninist philosophy.[50] In addition to the antireligious substance of each course, the curriculum from the universities in the Soviet Union presented scientific findings correct or incorrect based on their supposed ideological positions, not on the objective, applied, and experimental essence of science.[51] Militant atheists also believed science disproved religion because God remained unseen, His miracles were never subject to empirical verification, and certain religious stories were scientifically inconceivable.[52] Bruce Sheiman, himself a leader in the Atheist 3.0 movement, has criticized militant atheism for asserting this belief that science is capable of determining the existence of God.[53]

Joseph McCabe, himself a militant atheist,[54] wrote in 1936 that "Russia is doing the finest and soundest reconstructive work of our time, and it is doing this, not only without God, but on a basis of militant Atheism."[55] However, militant atheism failed to eradicate Christianity, which resulted in the reopening of churches, the abandonment of the atheist teaching in schools, and the restoration of the seven day week.[56] Moreover, John W. Garver observes that the collapse of the Soviet Union ended the dominance of militant atheism over South-Central Asia and led to the reemergence of Islam in the region.[57]

Moldova

In Moldova, according to Mihaela Robila, during "the several decades of state-sponsored militant atheism, drastic methods were used" to prohibit the "expression of religious life"; such methods included the "forcible destruction of religious monuments, liquidation of churches, and mass deportation" of believers of different religions to Siberia.[58]

French Revolution

Two prominent militant atheists of the French Revolution included Jacques Hébert and Baron Anacharsis Cloots, who both advocated the dechristianisation of France.[4] Cloots, says Alister McGrath, did not believe in religious tolerance.[4] He vigorously campaigned for the atheistic Cult of Reason, which was officially proclaimed on 10 November 1793.[59] According to James Gray, Thomas Holcroft, an English militant atheist, was instrumental in founding the London Corresponding Society in 1792, "whose main aim was to connect with radical elements in Paris in the same year".[60]

PRC and the Cultural Revolution

The People's Republic of China is an atheist state,[61][62] as atheism is officially endorsed by the ruling Chinese Communist Party.[7] When the People's Republic of China was established, militant atheism compelled the Party to impose control on and limit religious suppliers.[63] As a result, foreign missionaries were expelled from the nation.[63] Furthermore, major religions including Buddhism, Daoism, Islam and Christianity were co-opted into national associations, while minor sects were labelled as reactionary organisations and were therefore banned.[63]

However, during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, a new form of militant atheism made great efforts to eradicate religion completely.[7][64] Under this militant atheism espoused by Mao Zedong, houses of worship were shut down; Buddhist pagodas, Daoist temples, Christian churches, and Muslim mosques were destroyed; artifacts were smashed; and sacred texts were burnt.[7][64] Moreover, it was a criminal offence to even possess a religious artifact or sacred text.[7] However, following the death of Mao Zedong in 1976, many former policies towards religious freedom returned although they are limited and tenuous, as religion is closely regulated by the government.[65]

According to philosopher Julia Ching, the Falun Gong religion was seen by Jiang Zemin, the General Secretary of the Communist Party of China, as an ideological threat to militant atheism and historical materialism.[66]

Politics

History

Sociologist Rodney Stark describes Thomas Hobbes and the other originators of the 'social "scientific" study of religion' as "militant opponents of religion" whose "militant atheism...was motivated partly by politics".[67] The 19th-century political activist Charles Bradlaugh is credited as the first militant atheist in the history of Western civilization.[68][69][70][71][72][73] The term has also been applied to other 19th-century political thinkers such as Ludwig Andreas Feuerbach,[74] Annie Besant,[75][76][77] and Schopenhauer.[78]

The Polish religious leader Stefan Wyszynski decided during his imprisonment (1953–1956) "to defend the faith of the nation against militant atheism by means of the power of the Virgin Mary."[79]

Italian Socialist movement

Benito Mussolini was a militant atheist in his early life.[80][81][82][83][84][85] Like other socialists of the Romagna, Mussolini adopted the militant atheism of the Italian Socialist movement.[86] In his later life, however, Mussolini signed a Concordat with the Church in order to consort with the bishops who blessed the Facist banners.[80][87]

Today

Figures in the 21st century in the USA and the UK who have been described as militant atheists include Michael Newdow.[88][89] In The Washington Monthly, Kevin Drum applies the term to Polly Toynbee.[90] The Argentinian Supreme Court Judge Carmen Argibay also describes herself as a "militant atheist",[91][92] and the journalist and campaigner Paul Foot has been praised as a "militant atheist".[93] Moreover, comedian Kathy Griffin identifies herself as a militant atheist.[94]

New Atheism

The terms militant atheist and atheist fundamentalist, have been used to criticize the New Atheism movement.[11] For example, Ian H. Hutchinson, professor of nuclear science and engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, has stated that the New Atheism movement constitutes militant atheism because demonstrates an "attack on religion" and a "lack of respect at all for religion."[12] Prof. Hutchinson also states that the arguments employed by the New Atheism movement are extensions of intellectual threads which have existed since the late 19th century.[12] As such, in the academic journal titled "International Journal for Philosophy of Religion," New Atheist leaders including Harris, Dawkins, and Hitchens are referred to as militant atheists.[95] The same phenomenon takes place in the academic journal titled "Studies: an Irish Quarterly Review,"[96] and "The Literary Review,"[97] as well as in academic literature, such as the Rowman & Littlefield published The Secularization Debate,[98] and the Sydney University Press published Politics and Religion in the New Century, for example.[99]

These individuals have also been labelled as militant atheists by other atheists such as Michael Ruse,[100][101] and Bruce Sheiman, a leader in the Atheism 3.0 movement, who stated that "when militant atheists portray religion, they critique every political and organizational misdeed that can be attributed to it" but "portray science in idealized terms, untainted by commercial interests, political intrusions, and ethical conundrums."[102] Richard Dawkins has, in turn, compared Ruse to "Neville Chamberlain, the British prime minister best known for his appeasement policy toward Nazi Germany."[103] Other articles in the popular media make reference to the leaders representing the New Atheism movement as militant atheists or atheist fundamentalists.[104][105][106]

Media

Journalist Charles Moore in the Daily Telegraph, authored an article entitled "Militant atheists: too clever for their own good",[107] which discussed Richard Dawkins, Christopher Hitchens, and A. C. Grayling; the article levied the labels of "intolerance, dogmatism, righteousness, moral contempt for one's opponents" to these New Atheist leaders.[108] Moore also stated that Dawkins promulgated the idea that atheism is "a superior order of being".[108] In the same newspaper, Raj Persaud categorised Richard Dawkins as a militant atheist for his "famously virulent views on religion, attacking it as a 'virus of the mind' and an 'infantile regression'."[109]

The editor of Quadrant Magazine, a literary and cultural journal, also refers to Dawkins in these terms, and suggests that Dawkins' views are an extreme example of intolerance.[110] Journalist RJ Eskow, in The Huffington Post refers to Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris as fundamentalist atheists, saying "I believe most atheists are progressive, enlightened people who are simply 'nonbelievers.' My quarrel is only with those who advocate the elimination of religion based on grandiose and unsubstantiated claims."[111]

British writer Theo Hobson in The Guardian claims that "criticisms levelled at religion by militant atheists are often crude and short-sighted".[112] Dawkins has responded to criticisms that he is hostile towards religion, saying "such hostility as I or other atheists occasionally voice toward religion is limited to words" and "It is all too easy to confuse fundamentalism with passion. I may well appear passionate when I defend evolution against a fundamentalist creationist, but this is not because of a rival fundamentalism of my own."[113]

Criticism

General

Melanie Phillips, a British author, suggests that militant atheism "in junking religion, has destroyed our sense of anything beyond our material selves and the here and now" and "paved the way for the onslaught on bedrock moral values ... and intimidation and bullying to drive this agenda into public policy".[114]

Simon Blackburn writes that "many professional philosophers, including ones such as myself who have no religious beliefs at all, are slightly embarrassed, or even annoyed, by the voluble disputes between militant atheists and religious apologists".[115]

Humanism

Paul Kurtz, considered by many to be the founder of secular humanism,[116] has criticized militant atheists in that "they resist any effort to engage in inquiry or debate" and militant atheism as "becom[ing] mere dogma."[117] Kurtz has criticized the militant atheism of the Soviet Union, which he stated "persecuted religious beleivers, confiscated church properties, executed or exiled tens of thousands of clerics, and prohibited believers to engage in religious instruction or publish religious materials" and praised Mikhail Gorbachev's "dismantling such policies by permitting greater freedom of religious conscience...moving from militant atheism to tolerant humanism."[118] Kurtz cited the commitment to "human freedom and democracy" as humanism's basic difference from the militant atheism of the Soviet Union, which consistently violated basic human rights.[34] Kurtz also stated that the "defense of religious liberty is as precious to the humanist as are the rights of the believers."[34]

Terms

Catherine Fahringer of the Freedom From Religion Foundation suggested that the label militant was often routinely applied to atheist for no good reason – "very much as was the adjective 'damn' attached to the noun 'Yankee' during the Civil War."[119] The linguist Larry Trask suggests that the word militant "is used all too freely in the feebler sense of 'holding or expressing views which are unpopular or which I don't like'." He notes that Richard Dawkins is "accused by tabloid newspapers and other commentators of being a 'militant atheist'", for saying he doesn't like religion. However, according to Trask, activity engaged in by some Christians, such as knocking on strangers' doors "demanding to talk about the Bible", never seems to "draw forth the label 'militant'." Trask concludes, "if you find yourself writing this word, stop and think whether it has any clear meaning, or whether you are just using it as a swearword."[120]

See also

- Atheist state

- Soviet anti-religious legislation

- Persecution of Christians in the Soviet Union

- Society of the Godless

- The Trouble with Atheism

- Alexander Solzhenitsyn

Notes and references

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Bagginiwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Harold Joseph Berman (1993). Faith and Order: The Reconciliation of Law and Religion. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. Retrieved 2011-07-09.

One fundamental element of that system was its propogation of a doctrine called Marxism-Leninism, and one fundamental element of that doctrine was militant atheism. Until only a little over three years ago, militant atheism was the official religion, one might say, of the Soviet Union and the Communist Party was the established church in what might be called an atheocratic state.

Cite error: The named reference "Integral" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b J. D. Van der Vyver, John Witte (1996). Religious Human Rights in Global Perspective: Legal Perspectives. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. Retrieved 2011-07-09.

For seventy years, from the Bolshevik Revolution to the closing years of the Gorbachev regime, militant atheism was the official religion, one might say, of the Soviet Union, and the Communist Party was, in effect, the established church. It was an avowed task of the Soviet state, led by the Communist Party, to root out from the minds and hearts of the Soviet state, all belief systems other than Marxism-Leninism.

Cite error: The named reference "Fundamental" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b c Alister E. McGrath. The Twilight of Atheism: The Rise and Fall of Disbelief in the Modern World. Random House. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

So was the French Revolution fundamentally atheist? There is no doubt that such a view is to be found in much Christian and atheist literature on the movement. Cloots was at the forefront of the dechristianization movement that gathered around the militant atheist Jacques Hébert. He "debaptised" himself, setting aside his original name of Jean-Baptiste du Val-de-Grâce. For Cloots, religion was simply not to be tolerated.

- ^ a b Gerhard Simon (1974). Church, State, and Opposition in the U.S.S.R. University of California Press. Retrieved 2011-07-09.

On the other hand the Communist Party has never made any secret of the fact, either before or after 1917, that it regards 'militant atheism' as an integral part of its ideology and will regard 'religion as by no means a private matter'. It therefore uses 'the means of ideological influence to educate people in the spirit of scientific materialism and to overcome religious prejudices..' Thus it is the goal of the C.P.S.U. and thereby also of the Soviet state, for which it is after all the 'guiding cell', gradually to liquidate the religious communities.

- ^ a b Simon Richmond (2006). Russia & Belarus. BBC Worldwide. Retrieved 2011-07-09.

Soviet 'militant atheism' led to the closure and destruction of nearly all the mosques and madrasahs (Muslim religious schools) in Russia, although some remained in the Central Asian states. Under Stalin there were mass deportations and liquidation of the Muslim elite.

- ^ a b c d e The Price of Freedom Denied: Religious Persecution and Conflict in the Twenty-First Century (Cambridge Studies in Social Theory, Religion and Politics). Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

Seeking a complete annihilation of religion, places of worship were shut down; temples, churches, and mosques were destroyed; artifacts were smashed; sacred texts were burnt; and it was a criminal offence even to possess a religious artifact or sacred text. Atheism had long been the official doctrine of the Chinese Communist Party, but this new form of militant atheism made every effort to eradicate religion completely.

- ^

Julian Baggini. Atheism. Sterling Publishing. p. 131. Retrieved 2011-06-28.

However, although this defense is certainly enough to justify a "not guilty" verdict in the court of history, the Soviet experience does point to two dangers of atheism. The first of these is a too-zealous militancy. It is one thing to disagree with religion and quite another to think that the best way to counter it is by oppression and making atheism the official state credo. What happened in Soviet Russia is one of the reasons why I personally dislike militant atheism.

- ^ Watson, Simon (Spring 2010). "Review Essay: Richard Dawkins' The God Delusion and Atheist Fundamentalism". Anthropoetics: the Journal of Generative Anthropology. 15 (2). UCLA. Retrieved 19 October 2009.

Aware of the accusation that his hostility to religion marks him out as "a fundamentalist atheist," Dawkins defends himself by delineating an overly simplified and shallow definition of "fundamentalism."

- ^ Rodrigues, Luís. Open Questions: Diverse Thinkers Discuss God, Religion, and Faith. ABC-CLIO. Retrieved 2011-06-27.

When we talk about militant atheists or fundamentalist atheists, I have a problem with those terms because... a militant or fundamentalist atheist simply says. "You can have your beliefs; just keep them private and don't force them on us."

- ^ a b

Amarnath Amarasingam. Religion and the New Atheism: A Critical Appraisal. Brill Academic Publishers. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

It is no exaggeration to describe the movement popularized by the likes of Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennet, Sam Harris, and Christopher Hitchens as a new and particularly zealous form of fundamentalism— an atheist fundamentalism.

- ^ a b c "Ian Hutchinson on the New Atheists". BioLogos Foundation. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

Ian Hutchinson tells us in this video discussion that New Atheism -- a term used to describe recent intellectual attacks against religion -- is actually a misnomer. It is better, he says, to call the movement "Militant Atheism". In fact, the arguments made by New Atheists are not new at all, but rather extensions of intellectual threads which have existed since the late 19th century. The only unique quality of this movement is the degree of criticism and edge with which its members write and speak about religion. According to Hutchinson, the books written by New Atheists in the past decade simply restate many of the same arguments which have emanated from atheist thinkers for decades. The militant edge of these arguments is what makes "New" Atheism unique and elevates it to a level of popularity within a subset of the population. It is because these Militant Atheists show no respect at all for religion, says Hutchinson, that they are receiving status as a new movement.

- ^

George William Foote (1894). "Flowers of Freethought". Nabu Press. Retrieved 2011-07-09.

At the same time, however, we admit that militant Atheism is still, as of old, an offence to the superfine sceptics who desire to stand well with the great firm of Bumble and Grundy, as well as to the vast army of priests and preachers who have a professional interest in keeping heresy "dark," and to the truling and priviledged classes, who feel that militant Atheism is a great disturber of the peace which is founded on popular superstition and injustice.

- ^ a b R. J. Overy (19 October 2009). The Dictators: Hitler's Germany and Stalin's Russia. W. W. Norton & Company.

The communist regime treated the Church as a political institution rather than as a set of beliefs. On 28 January 1918 the Russian Orthodox Church was formally separated from the state; religious belief was permitted as long as it did not threaten public order or trespass on political soil. Religious property was liquidated, and a twenty-year programme of church closures begun. Religion was banned from schools. The state and the pary were officially atheist.

- ^ Crane Brinton. A History of Civilization: 1648 to the present. Prentice Hall. Retrieved 19 October 2009.

Militant atheism had been the policy of the early Bolsheviks. Behind their attitude lay more than the standard Marxist feeling that religion was the opium of the masses; in Russia the Orthodox church had always been a pillar of czarism.

- ^ Dimitry Pospielovsky (19 October 2009). The Orthodox Church in the History of Russia. St Vladimir's Seminary Press.

It might be expected that as a Christian leader, he would at least declare that a Christian could not vote for a party that preached and practiced genocide, whether racial or class-based , nor for a party whose ideology included a militant atheism aiming at liquidation of religion.

- ^ a b c d Harold Joseph Berman (19 October 2009). Faith and Order: The Reconciliation of Law and Religion. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing.

Under the doctrine of spearation of church and state, churches in the Soviet Union were forbidden to engage in any activities that were within the sphere of responsibilities of the state. The meant, for example, that churches could not give to the poor or carry on educational activities. They could not publish literature since all publishing was done by state agencies, although after World War II the Russian Orthodox Church was given the right to publish church calendars, a very limited number of Bibles, and a monthly journal in a limited number of copies. Churches were forbidden to hold any special meetings for children, youth or women, or any general meetings for religious study or recreation, or to open libraries or keep any books other than those necessary for the performance of worship services. Severe criminal penalties were imposed for violation of these rules.

Cite error: The named reference "Separation" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Christel Lane (19 October 2009). Christian Religion in the Soviet Union: A Sociological Study. State University of New York Press.

Militant atheist measures, both in premeditated and in unforeseen ways, have also caused far-reaching changes in the organisational structure of collectivities, in the ways they perform their religious functions and in which believers satisfy their religious requirements. In the field of organisation, most measures have had the effect of weakening or destroying central organisation and strengthening local independence and spontaneity.

- ^ J. D. Van der Vyver, John Witte (19 October 2009). Religious Human Rights in Global Perspective: Legal Perspectives. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.

Churches, mosques, and synagogues were deprived of almost all activities except the conduct or worship services. Moreover, schools were not merely to avoid the teaching of religion; they were actively to promote the teaching of atheism. These doctringes were spelled out in a 1929 law that remained the basic legistlation on the subject until the Gorbachev reforms of the late 1980s. There was freedom of religious worship, but churches were forbidden to give any material aid to their memebers or charity of any kind, or to hold any special meetings for children, youth, or women, or general meetings for religious study, recreation, or any similar purpose or to open libraries or to keep any books other thanose necessary for the performance of worhsip services. The formula of the 1929 law was repeated in the 1936 Constitution and again in the 1977 Constitution: freedom of religious worship and freedom of atheist propogranda-meaning (1) no freedom of religious teaching outside of the worship service itself, plus (2) a vigorous campaign in the schools, in the press, and in special meetings organized by atheist agitators, to convice people of the folly of religious beliefs.

- ^ Richard Sakwa (19 October 2009). The Rise and Fall of the Soviet Union, 1917-1991. Psychology Press.

Marx's view on religion as the 'opiate of the people' under the Bolsheviks took the form a militant atheism that sought to destroy the social sources of the power of the Church, and to extirpate religious belief as a social phenomenon. Uner the slogan of separating Church and state, the Bolsheviks in effect expropriated church property and dramatically limited the Church's ability to conduct a normal religious life.

- ^ J. D. Van der Vyver, John Witte (19 October 2009). Religious Human Rights in Global Perspective: Legal Perspectives. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.

Moreover, schools were not merely to avoid the teaching of religion; they were actively to promote the teaching of atheism.

- ^ a b Paul Froese. The Plot to Kill God: findings from the Soviet experiment in Secularization. University of California Press. Retrieved 2007–10–18.

Militant atheists also believed that science disproved religion because God remained unseen, his miracles were never subject to empirical verification, and certain religious stories were inconceivable. As such, the Soviet school system consistently promoted "atheistic science" to combat the effects of religion. The curriculum of scientific atheism resembled the curriculum of scientific atheism resembled the curriculum for much of the Soviet educational system, as it was based more on memorization than critical analysis. For homework, schoolchildren were sometimes asked to convert a member of their family to atheism by reciting arguments that were intended to disprove religious beliefs. And schoolchildren often memorized antireligious rhymes, songs, and catechisms. Antireligious ideas infiltrated the most basic in unrelated topics: "Physics, biology, chemistry, astronomy, mathematics, history, geography and literature all serve as jumping-off points to instruct pupils on the evils or falsity of religion." Although many school subjects appear unrelated to religion, Soviets believed that any intellectual activity was intrinsically opposed to religion. The Soviet educational system officially stated that "that bringing up of children in the atheist spirit" was one of its primary missions. University students were also required to actively propogate atheism and were told, "Those who refuse to make such practical application of their study [of scientific atheism] will lose their scholarships and must leave the university. Special pressure was placed on academics and scientists to join the atheist educational organization Znanie, and, b the late 1970s, for example, over 80 percent of all professors and doctors of science in Luthuania became members. The course syllabi from the atheist universities of the Soviet Union indicate how the topic of atheism was presented as a historically logical outcome of scientific development.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Harold Joseph Berman (19 October 2009). Faith and Order: The Reconciliation of Law and Religion. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing.

The formula of the 1936 and 1977 Soviet Constitutions was: freedom of religious worship and freedom of atheist propoganda-meaning, first no freedom of religious teaching other than the worship service itself, and second, a vigorous campaign in the schools and universities, in the press, and in special meetings organized by atheist so-called "agitators," to convince people of the folly of religious beliefs.

- ^ J. D. Van der Vyver, John Witte (19 October 2009). Religious Human Rights in Global Perspective: Legal Perspectives. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.

In 1960 Criminal Code of the Russian Republic imposed a fine for violating lasw of separation from the state and of the school from the church, and, for repeated violators, deprivation of freedom up to three years (Article 142). Such violations included organizing religious assemblies and processions, organizing religious instruction for minors, and preparing written materials calling for such activities. Other types of religious activities were subject to more severe sanctions: thus leaders and active participants in religious groups that caused damage to the health of citizens or violted personal rights, or that tried to persaude citizens not to participate in social activities or to perform duties of citizens, or that drew minors into such group, were punishable by deprivation of freedom up to give years (Article 277).

- ^ J. D. Van der Vyver, John Witte (19 October 2009). Religious Human Rights in Global Perspective: Legal Perspectives. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.

These articles of the Criminal Code were enacted as part of the severe anti-religious campaign launched under Khrushchev in the early 1960s, when an estimated 10,000 Russian Orthodox churches-half the total number-were closed, together with five of the eight insitutions for training priests, and the independence of the priesthood were curtailed both nationally and locally.

- ^ Gerhard Simon (19 October 2009). Church, State, and Opposition in the U.S.S.R. University of California Press.

The extensive application of the laws on religion, massive atheist propoganda and Stalinist terror in the 1930s had led by the eve of the Second World War to the complete destruction of several denominations include the Baptists, the Evangelical Christians and the Evangelical-Lutheran Church. Even the Russian Orthodox Church seemed in 1939 to be on the eve of disintegration. In the whole of the Soviet Union there were only a few hundred clergy and open churches left, only seven bishops were still in office and all diocesan administrations, except those in Moscow and Leningrad, had had to cease their activity.

- ^ Rev. Thomas Hoffmann; William Alex Pridemore. "Esau's Birthright and Jacob's Pottage: A Brief Look at Orthodox-Methodist Ecumenism in Twentieth-Century Russia" (PDF). Demokratizatsiya. Retrieved 19 October 2009.

One of these was the resurgence of non-Orthodox Christian confessions, including the Methodist Church-a denomination completely eradicated in Russia during the Soviet era.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Paul Froese. The Plot to Kill God: findings from the Soviet experiment in Secularization. University of California Press. Retrieved 2007–10–18.

There were more than fifty thousand Orthodox priests before the Russian Revolution, and by mid-1939, there were no more than three to four hundred clergy.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ John Meyendorff. Witness to the World. St Vladimir's Seminary Press. Retrieved 2007–10–18.

After having been the state religion for centuries both in Russian and in almost all the countries of Europe, Christianity suddenly was confronted with a militant atheistic system claiming to regulate not only the material, but also the spiritual life of man. The number of those who died for the faith is innumerable: in the year 1922 alone, 2691 secular priests, 1962 monks and 3447 nuns (N. Struve, Christians in Russia, Harvill Press, London, 1967, p. 38).

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Timothy Ware. The Orthodox Church. Penguin Books. Retrieved 2007–10–18.

Chapter 8 The Twentieth Century, II: Orthodoxy and the Militant Atheists: The Ottoman Turks, while non-Christians, were still worshippers of the one God and, as we have seen, allowed the Church a large measure of toleration. But Soviet Communism was committed by its fundamental principles to an aggressive and militant atheism. Not only were churches closed on a massive scale in the 1920s and 1930s, but huge numbers of bishops and clergy, monks, nuns and laity were sent to prison and to concentration camps. How many were executed or died from ill-treatment we simply cannot calculate. Nikita Struve provides a list of martyr-bishops running to 130 names, and even this he terms 'provisional and incomplete'. The sum total of priest-martyrs must extend into tens of thousands.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ De James Thrower (19 October 2009). Marxist-Leninist Scientific Atheism and the Study of Religion and Atheism in the USSR. Walter de Gruyter.

In the pre-war period the emphasis was on 'practical atheism' -- the more so as Stalin, the sole arbiter in such matters had not made a single theoretical pronouncement on religion or the study of religion - and 'practical atheism' meant schools from the propogation of atheism, the administrative elimination of the clergy, atheist museums where churches had once stood, and a continuois stream of hate-propganda designed to terroise the faithful into submission.

- ^ A short history of Soviet socialism ISBN 9781857283556

- ^ Orthodox Christianity and Militant Atheism in the Twentieth Century

- ^ a b c Paul Kurtz, Vern L. Bullough, Tim Madigan. Toward a New Enlightenment: the philosophy of Paul Kurtz. Transaction Books. Retrieved 2007–10–18.

There have been fundamental and irreconciliable differences between humanists and atheists, particularly Marxist-Leninists. The defining characteristic of humanism is its committment to human freedom and democracy; the kind of atheism practiced in the Soviet Union has consistently violated basic human rights.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cite error: The named reference "Rights" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Allan Todd, Sally Waller (19 October 2009). Origins and Development of Authoritarian and Single Party States. Cambridge University Press.

By the time of the Nazi invasion in 1941, nearly 40,000 Christian churches and 25,000 Muslims mosques had been closed down and converted into schools, cinemas, clubs, warehouses and grain stores, or Museums of Scientific Atheism.

- ^ Allan Todd, Sally Waller. "Crispin Paine". Present Pasts. 1.

By the time of the Nazi invasion in 1941, nearly 40,000 Christian churches and 25,000 Muslims mosques had been closed down and converted into schools, cinemas, clubs, warehouses and grain stores, or Museums of Scientific Atheism.

- ^ Freidrich Engels Encyclopedia Britannica 2008.

- ^ Lobkowicz, N (1964). "Karl Marx's Attitude toward Religion", The Review of Politics, Vol. 26 (3), July, pp.319–352. [1], see also [2]

- ^ John F. Pollard Benedict XV: the unknown pope and the pursuit of peace p. 199.

- ^ On the Significance of Militant Materialism Lenin 1922

- ^ Журнал "БЕЗБОЖНИК", Москва, СССР (Bezbozhnik Magazine, Moscow, USSR). The page is in UTF-8 encoding. The caption to the front page picture of the No. 1 issue, by Dmitry Moor, shown in the article, is "We've finished with the earthly kings – now it's time to take care of the heavenly ones!"

- ^ Alexandre A. Bennigsen, S. Enders Wimbush (19 October 2009). Muslim National Communism in the Soviet Union: A Revolutionary Strategy for the Colonial World. University of Chicago Press.

In disgrace after Sultan Galiev's trial in 1928, he was, until his final purge in 1937, chairman of the Tatar Union of Militant Godless.

- ^ Sabrina P. Ramet (19 October 2009). Religious Policy in the Soviet Union. Cambridge University Press.

Local public and voluntary organisations - the Komsomol, the Young Pioneers, workers' Clubs and, of course, the League of Militant Atheists - were encouraged to undertake a whole range of anti-religious initiatives: promoting the observance of the five day working week, ensuring that priests did not visit believers in their homes, supervising the setting-up of cells of the Leauge of Militant Atheists in the army. Public lampoons and blasphemous parades, recalling the early 1920s, were resumed from 1928. One of the main activities of the League of Militant Atheists was the publication of massive quantities of anti-religious literature, cpmprising regular journals and newspapers as well as books and pamphlets. The number of printed pages rose from 12 million in 1927 to 800 million in 1930.

- ^ William G. Rosenberg (19 October 2009). Bolshevik Visions: First Phase of the Cultural Revolution in Soviet Russia, Part 1. University of Michigan Press.

The publication in 1923 of Yaroslavsky's response to Khegund (see below), signalled the beginning of an organized ant-religious movement. Many in the party still urged caution; the "League of Militant Atheists, formally the a "private union" rather than a party body, was not permitted to function until 1925.

- ^ M. Searle Bates (19 October 2009). Religious Liberty: An Inquiry. Kessinger Publishing Company.

On the other hand, the League of Militant Atheists reproted for 1932 an organization of 80,000 cells with 7,000,000 members, besides 1,500,000 children in affiliated groups.

- ^ Союз воинствующих безбожников (Union of the Militant Atheists) in the Great soviet Encyclopedia

- ^ Joseph Pearce. Solzhenitsyn: A Soul in Exile. Ignatius Press. Retrieved 2007–10–18.

In the years immediately before and after the Revolution, the church was shunned and subjected to ridicule by young people and the intelligentsia. Solzhenitsyn rememberd how many fiery adherents were claimed by militant atheism in the 1920s. "Those who went on rampages, blew out candles, and smashed icons with axes have now crumbled into dust, like thier Union of the Militant Godless."

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Знание", Всесоюзное общество (The All-Union "Knowledge" Society) in the Great soviet Encyclopedia

- ^ Dr. John Anderson. Religion, state, and politics in the Soviet Union and successor states. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 2007–10–18.

In 1961 the Ukrainian branch of the society started to produce a similar journal initially entitled Voivnichy ateist (Militant Atheist).

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Helge Kragh. Entropic Creation. Ashgate Publishing. Retrieved 2007–10–18.

In the attempts to establish an ideologically acceptable view of science, the new physics became a matter of considerable controversy in the young Soviet Union. Physicists and party philosophers discussed the problematic relationship of relativity theory and quantum mehanics to Marxist-Leninist philosophy.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Paul Froese. The Plot to Kill God: findings from the Soviet experiment in Secularization. University of California Press. Retrieved 2007–10–18.

Militant atheists also believed that science disproved religion because God remained unseen, his miracles were never subject to empirical verification, and certain religious stories were inconceivable. The course syllabi from the atheist universities of the Soviet Union indicate how the topic of atheism was presented as a historically logical outcome of scientific development; Soviet college students chose from the following course selections: Physics...Chemistry...Geology...Mathematics...Biology...Medicine...What stands out in these syllabi, in addition to the antireligious substance of each course, is the way in which the curriculum appears to ignore the objective, applied, and experimental essence of science. Instead, scientific findings are presented as correct or incorrect based on their supposed ideological positions. Religion is presented as the historic cofounder of scientific advancement, with atheism providing the phislosophical framework from which to conduct accurate science.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Paul Froese. The Plot to Kill God: findings from the Soviet experiment in Secularization. University of California Press. Retrieved 2007–10–18.

Militant atheists also believed science disproved religion because God remained unseen, his miracles were never subject to empirical verification, and certain religious stories were scientifically inconceivable. Following World War II and after the dissolution of the League of Militant Atheists, Soviet officials started a campaign to produce natural-scientific arguments against belief in God. For instance, Soviet scientists placed holy water under a microscope to prove that it had no special properties, and the corpses of saints were exhumed to demonstrate that they too were subject to corruption. These activities indicated that atheist propgandists held a very literal interpretation of religious language; for them, holy water and the bodies of saints were expected to hold some physical sign of their divinity.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Bruce Sheiman. An Atheist Defends Religion: Why Humanity is Better Off with Religion Than Without It. Penguin Books. Retrieved 2007–10–18.

The militant atheist asserts, incorrectly, that science is capable of determining the nonexistence of God.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Madalyn Murray O'Hair. The Atheist World. Kessinger Publishing.

This is a listing of the great and near great compiled by Joseph McCabe, ex-Roman Catholic priest and militant Atheist of early in this century.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Joseph McCabe. Is the Position of Atheism Growing Stronger?. Kessinger Publishing. Retrieved 2007–10–18.

For the news is spreading, and is triumphing even over reactionary opposition that Russia is doing the finest and soundest reconstructive work of our time, and it is doing this, not only without God, but on a basis of militant atheism.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Earle E. Cairns. Christianity through the centuries: a History of the Christian Church. Zondervan. Retrieved 2007–10–18.

The failure of militant atheism to eradicate Christianity; the persistence of belief in God, which approximately half of the Russian people expressed in the 1937 census; and the threatening international situation dictated the need for a strategic retreat after 1939. Churches were reopened, the antireligious carnivals were dropped, and the teaching of atheism in schools was abandoned. In 1943 Sergius was permitted to function as the patriarch of Moscow and all Russia. The seven-day week was resotred, seminaries were permitted to reopen, and the Orthodox church was freed of many burdensome restrictions.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ John W. Garver. China and Iran: Ancient Partners in a Post-Imperial World. University of Washington Press. Retrieved 2007–10–18.

Post-Soviet Central Asia witnessed a swift revival of Islam. The collapse of Soviet power lifted a seventy-year-long reign of militant atheism and opened the way to reemergence of the long-suppressed Islamic faith of the Central Asian peoples.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Mihaela Robila (19 October 2009). Families in Eastern Europe. Emerald Group Publishing.

quote=During several decades of state-sponsored "militant atheism," drastic methods were used to suppress and prohibit any expression of religious life. There was a forcible destruction of religious monuments, liquidation of churches, and mass deportation to Siberia of religious people and believers of different religions

{{cite book}}: Missing pipe in:|quote=(help) - ^ Alister E. McGrath. The Twilight of Atheism: The Rise and Fall of Disbelief in the Modern World. Random House. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

Where Robespierre sought to advocate the religion of the Supreme Being, around which the French people could unite, Cloots vigorously pursued a more atheistic approach. He was an active member of the faction that successfully campaigned for the atheistic "Cult of Reason," which was officially proclaimed on November 10, 1793.

- ^ James Gray. "Review of The French Revolution and the London Stage 1789-1805, by George Taylor". Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

n two chapters devoted to reactions of the English stage to the Reign of Terror in France, Taylor notes that Thomas Holcroft (1745-1809), a militant atheist and a pro-Revolutionary zealot, helped to found in 1792 the London Corresponding Society, whose main aim was to connect with radical elements in Paris in the same year.

- ^ China in the 21st century. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

China is still officially an atheist country, but many religions are growing rapidly, including evangelical Christianity (estimates of how many Chinese have converted to some form of Protestantism range widely, but at least tens of millions have done so) and various hybrid sects that combine elements of traditional creeds and belief systems (Buddhism mixed with local folk cults, for example).

- ^ The State of Religion Atlas. Simon & Schuster. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

Atheism continues to be the official position of the governments of China, North Korea and Cuba.

- ^ a b c The New Blackwell Companion to the Sociology of Religion. Wiley-Blackwell. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

As soon as the PRC was established, militant atheism compelled the party to impose control and limitations on religious suppliers. Foreign missionaries, who were considered a part of Western imperialism, were expelled, and cultic or heterodox sects that were regarded as reactionary organizations (fandong hui dao men), were banned. Further, major religions - Buddhism, Daoism, Islam, Catholicism, and Protestantism, which were difficult to eliminate and possesed diplomatic value for the isolated regime - were co-opted into national associations.

- ^ a b Bryan S. Turner. Religion and Modern Society: Citizenship, Secularisation and the State. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

The contrast between religion in American and militant atheism in China could not have been more stark or profound. While the Red Guards under Mao Zedong's leadership were busy destorying Buddhist pagodas, Catholic churches and Daoist temples, the Christian Right were equally busy condemning the communists.

- ^ The Price of Freedom Denied: Religious Persecution and Conflict in the Twenty-First Century (Cambridge Studies in Social Theory, Religion and Politics). Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

Following Mao Zedong's death in 1976, however, many of the former "tolerations" for religion gradually returned. Like the former policies of religious toleration, however, freedoms were limited and tenuous. Modern China remains a nation where there are few social pressures preventing involvement, but religion is still closely regulated by the sate and atheism remains part of the official policy.

- ^ The Falun Gong: Religious and political implications American Asian Review/January 1, 2001 By Professor Julie Ching Institute of Asian Studies University of Toronto [3]

- ^ Rodney Stark "Atheism, Faith and the Social Scientific Study of Religion" Journal of Contemporary Religion Vol 14 No 1 1999, pp. 41–62.

- ^ Madalyn Murray O'Hair. "Agnostics". American Atheist Online Services. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

Charles Bradlaugh was the first militant Atheist in the history of Western civilization. He was elected to the British parliament six times, and each time that body refused to seat him because he was an Atheist -- and because he would not swear his allegiance to queen and country, so help him "God." Everyone in England knew Bradlaugh and his fight, and he raised the issue of Atheism to every person in public life as he sought allies.

- ^ Ian Hill Nish, Hugh Cortazzi. Britain & Japan: Biographical Portraits. Psychology Press. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

At South Place, Robert Young also came to know Charles Bradlaugh (1833-91), the first militant Atheist.

- ^ Laurel Brake, Marysa Demoor. Dictionary of nineteenth-century journalism in Great Britain and Ireland. Academia Press. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

A well-set Sunday weekly* selling for 1 d, the Secular Review's stance was representative of a relatively moderate style of Secularism, sympatheitc to socialism and aligned against the individualism and militant atheism of Charles Bradlaugh and his National Reformer. In its discussion of religion, philosophy, ethics, science and history, and in reviewing Secularism and 'what purports to be so, and is not', the title's stated domain of inquiry was 'this world, without implying disregard or denial of another' (Holyoake 1876).

- ^ Craig Ott; Harold A. Netland. Globalizing Theology: Belief and Practice in an Era of World Christianity. Baker Academic. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

She was a close friend and coworker of Charles Bradlaugh, the militant atheist and first president of the National Secular Society (set up in 1866), and helped to edit his journal, the National Reformer.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ James Richard Moore. History, Humanity and Evolution: Essays for John C. Greene. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

Though at first allied with the militant atheist Charles Bradlaugh (1833-91) and his National Secular Society (NSS), the elder Watts refused in 1877 to defend Bradlaugh's right to republish Knowlton's Fruits of Philosophy, a pamphlet on on birth control.

- ^ Bryan S. Turner. Religion and Modern Society: Citizenship, Secularisation and the State. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

Secularism, when under the inspiration of militant atheists such as Charles Bradlaugh, Member of Parliament for Northhampton in Great Britan, assumed a more striden, uncrompromising and critical relationship to religious belief.

- ^ The Debate Between Feuerbach and Stirner: An Introduction, in The Philosophical Forum 8, number 2-3-4, (1976)- available on the web here

- ^ Annie Wood Besant. Theosophist Magazine Collection 1920-1955. Kessinger Publishing. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

Madame Blavatsky, a Russian, suspected of being a sypy, converted Anglo-Indians to a passioante belief in her Theosophy mission, even when the Jingo fever was the hottist, and in her declining years she succeeded in winning over to the new-old religion Annie Besant, who had for years fought in the forefront of the van of militant atheism.

- ^ Joel H. Spring. Globalization and educational rights: an intercivilizational analysis. Psychology Press. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

Annie Besant had an important influence on Nehru's family and on social reform in India. Born in 1847, she was known in England as "Red Annie" because of her activities as a militant atheist, socialist, and trade union organizer.

- ^ S. W. Jackman, Sydney Wayne Jackman. Deviating voices: women and orthodox religious tradition. James Clarke & Co. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

The final chapter of Helena Petrovna Blavatsky's life was to be shared with the individual who probably became her most famous disciple, namely, Annie Besant, who had had two children while married to an Anglican clergyman, but was now a militant atheist and radical.

- ^ Gerard Mannion. Schopenhauer, religion and morality: the humble path to ethics. Ashgate Publishing. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

This work challenges the textbook assessment of Schopenhauer as militant atheist and absolute pessimist.

- ^ George Weigel The Final Revolution: The Resistance Church and the Collapse of Communism p. 114.

- ^ a b Fascism: Post-war fascisms. Taylor & Francis. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

Mussolini did not have any philosophy: he only had rhetoric. He was a militant atheist at the beginning and alter signed the Convention with the Church and welcomed the bishops who blessed the Fascist pennants. In his early anticerlical years, according to a likely legend, he once asked God, in order to prove His existence to strike him down on the spot.

Cite error: The named reference "Mussolini1" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ United States. Directorate for Armed Forces Information and Education. Ideas in Conflict: Writing about the Great Issues of Civilization. Wadsworth Publishing. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

He became a militant atheist at an early age and throughout his life, flouted the conventions of Christain morality.

- ^ United States. Directorate for Armed Forces Information and Education. Ideas in Conflict: Writing about the Great Issues of Civilization. Wadsworth Publishing. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

He became a militant atheist at an early age and throughout his life, flouted the conventions of Christian morality.

- ^ William Henry Chamberlin (1941). The World's Iron Age. The Macmillan Company. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

Fascism, according to the former militant atheist Mussolini, "respects the God of the ascetics, of the saints, of the heroes and also God as prayed to by the primitive heart of the people."

- ^ Maxine Block, E. Mary Trow (1942accessdate = 2011-03-05). Current Biography: Who's News and Why, 1942. H. W. Wilson Company.

It was also pointed out that Mussolini had been a militant atheist and that the accord with the Pope was one the latter would one day regret, although the Catholic Church had supported the crusade for nationalism and "against Bolshevism.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Alfred Mitchell Bingham (1942). Man's estate: adventures in economic discovery. W. W. Norton & Company. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

Mussolini was a militant atheist, a militant republican, and a militant Marxist, before he became a fascist.

- ^ Jasper Godwin Ridley. Mussolini: a biography. Cooper Square Press. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

Mussolini, like all the Socialists of the Romagna, had adopted the militant atheism of the Italian Socialist movement.

- ^ Five Moral Pieces. Mariner Books. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

He started out as a militant atheist, only to sign the Concordat with the Church and to consort with the bishops who blessed the Facist banners.

- ^ The New American Vol. 18, No. 15, 29 July 2002.

- ^ Les Kinsolving. "Militant atheism on display". WorldNetDaily. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

But that right is not enough for militant atheist Newdow. He wants the Supreme Court of the United States to eliminate the right of the Congress to vote to include the two words "under God" in the Pledge of Allegiance. His demand in court, which was affirmed by California's Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, is an attempt to censor the majority's free exercise of both the First Amendment's guarantee of free speech and freedom of religious expression. That this affirmation "under God" is by no means worship – any more that it is compulsory for all to say it – makes no difference to this militant atheist.

- ^ "Huffing over Narnia". The Washington Monthly. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

I'm not an especially militant atheist myself, but I have to admit that it's bracing to see one in high dudgeon occasionally. Today, the Guardian's famously acerbic Polly Toynbee, honorary associate of Britain's National Secular Society, takes on the Christian imagery of CS Lewis's Narnia books: Philip Pullman — he of the marvellously secular trilogy His Dark Materials — has called Narnia "one of the most ugly, poisonous things I have ever read".

- ^ "The Tablet". Tablet Pub. Co. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

As soon as her appointment was announced, Carmen Argibay told journalists she was a "militant atheist" and in favour of relaxing the strict abortion laws. Her declarations were met with a barrage of criticism from Catholic media.

- ^ "The Catholic world report, Volume 14". Ignatius Press. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

Argentine President Nestor Kirchner has proposed Carmen Argibay , who has described herself as a "militant atheist" and proponent of legal abortion to be a member of the Supreme Court.

- ^ "The epistles of Saint Paul". The Guardian. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

Paul Foot, militant atheist, revolutionary socialist and a man who couldn't listen to a pious sentiment without barking out a guffaw, would have agreed.

- ^ Blase DiStefano (June 2007). "Foul-Mouthed and Funny". OutSmart. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-07-01.

- ^ Fiala, Andrew. "Militant atheism, pragmatism, and the God-shaped hole". International Journal for Philosophy of Religion. 65 (3): 139–51.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Studies: an Irish quarterly review. Talbot Press. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

The leader of militant atheism in this part of the world is Richard Dawkins, a zoologist by training, who holds a chair founded for him at Oxford University.

- ^ Gillian Greenwood. The Literary Review. Fairleigh Dickinson University. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

Yet there is something wrong with Dawkins. He has an obsessive hatred of God or, as he would put it, the idea of God and those who propagate the idea. His life is dominated by his militant atheism.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|issues=ignored (help) - ^ William H. Swatos, Daniel V. A. Olson. The Secularization Debate. Rowman & Littlefield. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

But, aren't some scientists militant atheists who write books to discredit religion — Richard Dawkins and Carl Sagan for example? Of course. But, it also is worth note that most of those, like Dawkins and Sagan, are marginal to the scientific community for lack of significant scientific work. And possibly even more important is the fact that theologians (cf., Cupitt 1997) and professors of religious studies (cf., Mack 1996) are a far more prolific source of popular works of atheism.

- ^ Philip Andrew Quadrio, Carrol Besseling. Politics and Religion in the New Century: Philosophical Reflections. Sydney University Press. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

There is, therefore, a particular irony in the most recent spate of militant atheist attacks on the irrationality of religious belief (Dennett 2006; Dawkins 2006; Hitchens 2007; Harris 2004, 2007) which are, at the same time, the most conspicuous examples of slavish commitment to crude, popular ethnic stereotypes, combined with an almost delusional misrepresentation of the facts of recent history. These militant atheists use the rhetoric of critical rationality to wage ideological warfare, not just against religion, but against Muslims.

- ^ Michael Ruse. Mystery of mysteries: is evolution a social construction?. Harvard University Press. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

On reading Dawkins's more recent writings, where he has appointed himself the spokesman for militant atheism as well as militant Darwinism, one might be tempted to link the two.

- ^ Michael Ruse. Philosophy after Darwin: classic and contemporary readings. Princeton University Press. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

To be sure, there are militant Darwinian atheists such as Richard Dawkins. But I see no reason to accept the claim of people like Dawkins that Darwinian science dictates atheism (Dawkins 1986).

- ^ An Atheist Defends Religion. Penguin Books. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

Militant atheists like Dawkins, Hitchens, and Harris go to great lengths in their books to relegate religion to the lowest cultural status while placing reason and science well above it. The portray science in idealized terms, untainted by commercial interests, political intrusions, and ethical conundrums. But when militant atheists portray religion, they critique every political and organizational misdeed that can be attributed to it. Militant atheists speak of organized religion, but not, correspondingly, of organized science. To be fair, militant athiests need to view religion in the same sanitized way as they view science—or understand science through the same lens of doubt and skepticism as they view religion.

- ^ Mark A. Kellner. "Is Aggressive Atheism Ascending?". Adventist Review. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

In his book, Dawkins likens philosopher Michael Ruse, a Florida State University philosophy professor who has worked on the creationism/evolution debate in public schools, to Neville Chamberlain, the British prime minister best known for his appeasement policy toward Nazi Germany. Ruse, in turn, accuses "militant atheism" of not extending the same professional and academic courtesy to religion that it demands from others. Atheism's new dogmatic streak is not that different from the religious extremists it calls to task, Ruse said.

- ^ M. Paulli, Spoils split at 'Nibbie' awards

- ^ Johann Harri in The Independent

- ^ The Belief Trap: The evolutionary explanation of religion gets stuck. By Judith Shulevitz, Slate 8 March 2006.

- ^ "Militant atheists: too clever for their own good"

- ^ a b

Charles Moore. Militant atheists: too clever for their own good. Brill Academic Publishers. Retrieved 10 March 2011.