Kingdom of Italy

Kingdom of Italy Regno d'Italia | |

|---|---|

| 1861–1946 | |

| Motto: FERT (Motto for the House of Savoy) | |

| Anthem: (1861–1943; 1944–1946) Marcia Reale d'Ordinanza ("Royal March of Ordinance") (1924–1943) Giovinezza ("Youth")[a] (1943–1944) La Leggenda del Piave ("The Legend of Piave") | |

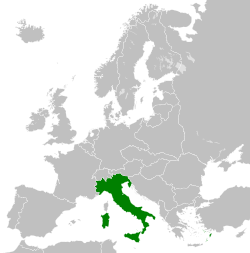

The Kingdom of Italy in 1936 | |

| Capital | |

| Largest city | Rome |

| Common languages | Italian |

| Religion | 96% Roman Catholicism (state religion) |

| Demonym(s) | Italian |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy

|

| King | |

• 1861–1878 | Victor Emmanuel II |

• 1878–1900 | Umberto I |

• 1900–1946 | Victor Emmanuel III |

• 1946 | Umberto II |

| Prime Minister | |

• 1861 (first) | Count of Cavour |

• 1922–1943 | Benito Mussolini[b] |

• 1945–1946 (last) | Alcide De Gasperi[c] |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Senate | |

| |

| History | |

| 17 March 1861 | |

| 3 October 1866 | |

| 20 September 1870 | |

| 20 May 1882 | |

| 26 April 1915 | |

| 28 October 1922 | |

| 22 May 1939 | |

| 27 September 1940 | |

| 25 July 1943 | |

• Republic | 2 June 1946 |

| Area | |

| 1861[1] | 250,320 km2 (96,650 sq mi) |

| 1936[1] | 310,190 km2 (119,770 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 1861[1] | 21,777,334 |

• 1936[1] | 42,993,602 |

| GDP (PPP) | 1939 estimate |

• Total | 151 billion (2.82 trillion in 2019) |

| Currency | Lira (₤) |

| |

The Kingdom of Italy (Template:Lang-it) was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia was proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946, when civil discontent led to an institutional referendum to abandon the monarchy and form the modern Italian Republic. The state resulted from a decades-long process, the Risorgimento, of consolidating the different states of the Italian Peninsula into a single state. That process was influenced by the Savoy-led Kingdom of Sardinia, which can be considered Italy's legal predecessor state.

Italy declared war on Austria in alliance with Prussia in 1866 and received the region of Veneto following their victory. Italian troops entered Rome in 1870, ending more than one thousand years of Papal temporal power. Italy entered into a Triple Alliance with the German Empire and the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1882, following strong disagreements with France about their respective colonial expansions. Although relations with Berlin became very friendly, the alliance with Vienna remained purely formal, due in part to Italy's desire to acquire Trentino and Trieste from Austria-Hungary. As a result, Italy accepted the British invitation to join the Allied Powers during World War I, as the western powers promised territorial compensation (at the expense of Austria-Hungary) for participation that was more generous than Vienna's offer in exchange for Italian neutrality. Victory in the war gave Italy a permanent seat in the Council of the League of Nations.

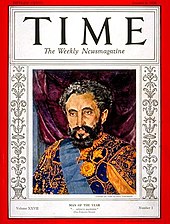

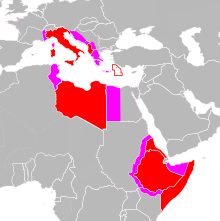

In 1922, Benito Mussolini became prime minister of Italy, ushering in an era of National Fascist Party government known as "Fascist Italy". The Italian Fascists imposed totalitarian rule and crushed the political and intellectual opposition while promoting economic modernization, traditional social values, and a rapprochement with the Roman Catholic Church. In the late 1930s, the Fascist government began a more aggressive foreign policy. This included war against Ethiopia, launched from Italian Eritrea and Italian Somaliland, which resulted in its annexation;[2] confrontations with the League of Nations, leading to sanctions; growing economic autarky; and the signing of the Pact of Steel.

Fascist Italy became a leading member of the Axis powers in World War II. By 1943, the German-Italian defeat on multiple fronts and the subsequent Allied landings in Sicily led to the fall of the Fascist regime. Mussolini was placed under arrest by order of the King Victor Emmanuel III. The new government signed an armistice with the Allies on September 1943. German forces occupied northern and central Italy, setting up the Italian Social Republic, a collaborationist puppet state still led by Mussolini and his Fascist loyalists. As a consequence, the country descended into civil war, with the Italian Co-belligerent Army and the resistance movement contending with the Social Republic's forces and its German allies.

Shortly after the war and the country's liberation, civil discontent led to the institutional referendum on whether Italy would remain a monarchy or become a republic. Italians decided to abandon the monarchy and form the Italian Republic, the present-day Italian state.

Overview

Territory

| History of Italy |

|---|

|

|

|

The Kingdom of Italy extended over the entire territory of present-day Italy and even more. The development of the Kingdom's territory progressed under Italian unification until 1870. Trieste and Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol were annexed in 1919 and remain Italian territories today. The Triple Entente promised to grant to Italy – if the state joined the Allies in World War I – several territories, including former Austrian Littoral, western parts of former Duchy of Carniola, Northern Dalmatia and notably Zara, Šibenik and most of the Dalmatian islands (except Krk and Rab), according to the secret London Pact of 1915.[3]

After the refusal by President Woodrow Wilson to acknowledge the London Pact and the signing of the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, with the Treaty of Rapallo in 1920 Italian claims on Northern Dalmatia were abandoned. During World War II, the Kingdom gained additional territory in Slovenia and Dalmatia from Yugoslavia after its breakup in 1941.[4]

The Italian Empire also gained territory until the end of World War II through colonies, protectorates, military occupations and puppet states. These included Eritrea, Italian Somaliland, Libya, Ethiopia (annexed by Italy from 1936 to 1941), Albania (an italian protectorate since 1939), British Somaliland, part of Greece, Corsica, southern France with Monaco, Tunisia, Kosovo and Montenegro (all territories occupied in World War II) Croatia (Italian and German client state in World War II), and a 46-hectare concession from China in Tianjin (see Italian concession in Tianjin).[5] However, it must be considered that all these territories were annexed and then lost at different times.

Government

The Kingdom of Italy was theoretically a constitutional monarchy. Executive power belonged to the monarch, who exercised his power through appointed ministers. The legislative branch was a bicameral Parliament comprising an appointive Senate and an elective Chamber of Deputies. The kingdom's constitution was the Statuto Albertino, the former governing document of the Kingdom of Sardinia. In theory, ministers were responsible solely to the king. However, by this time, a king couldn't appoint a government of his choosing or keep it in office against the express will of Parliament.

Members of the Chamber of Deputies were elected by plurality voting system elections in uninominal districts. A candidate needed the support of 50% of those voting and 25% of all enrolled voters to be elected in the first round of balloting. If not all seats were filled on the first ballot, a runoff was held shortly afterwards for the remaining vacancies.

After brief multinominal experimentation in 1882, proportional representation into large, regional, multi-seat electoral constituencies were introduced after World War I. Socialists became the major party. Still, they were unable to form a government in a parliament split into three different factions, with Christian populists and classical liberals. Elections took place in 1919, 1921 and 1924: in this last occasion, Mussolini abolished proportional representation, replacing it with the Acerbo Law, by which the party that won the largest share of the votes got two-thirds of the seats, which gave the Fascist Party an absolute majority of the Chamber seats.

Between 1925 and 1943, Italy was a quasi-de jure Fascist dictatorship, as the constitution formally remained in effect without alteration by the Fascists, though the monarchy also formally accepted Fascist policies and Fascist institutions. Changes in politics occurred, consisting of the establishment of the Grand Council of Fascism as a government body in 1928, which took control of the government system, as well as the Chamber of Deputies being replaced with the Chamber of Fasces and Corporations as of 1939.

Monarchs

The monarchs of the House of Savoy who led Italy were:

- Victor Emmanuel II (r. 1861–1878) – last King of Sardinia and first king of united Italy

- Umberto I (r. 1878–1900) – approved the Triple Alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary, assassinated in 1900 by the anarchist Gaetano Bresci

- Victor Emmanuel III (r. 1900–1946) – King of Italy during the First World War and during the Fascist regime of Benito Mussolini

- Umberto II (r. 1946–1946) – the last King of Italy who was pressured to call a referendum on whether Italy would retain the monarchy, but Italians voted to become a republic instead of a constitutional monarchy

Military structure

- King of Italy – supreme commander of the Italian Royal Army, Navy and later Air Force from 1861 to 1938 and 1943 to 1946

- First Marshal of the Empire – supreme commander of the Italian Royal Army, Air Force, Navy and the Voluntary Militia for National Security from 1938 to 1943 during the Fascist era, held by both Victor Emmanuel III and Benito Mussolini

- Regio Esercito (Royal Army)

- Regia Marina (Royal Navy)

- Regia Aeronautica (Royal Air Force)

- Milizia Volontaria per la Sicurezza Nazionale (Voluntary Militia for National Security also known as the "Blackshirts") – militia loyal to Mussolini during the Fascist era, abolished in 1943.

History

Unification process (1848–1870)

The creation of the Kingdom of Italy was the result of concerted efforts of Italian nationalists and monarchists loyal to the House of Savoy to establish a united kingdom encompassing the entire Italian Peninsula.

After the Revolutions of 1848, the apparent leader of the Italian unification movement was Italian revolutionary Giuseppe Garibaldi.[6] He led the Italian republican drive for unification in Southern Italy, but the Northern Italian monarchy of the House of Savoy in the Kingdom of Sardinia, a state with a significant Italian population, whose government was led by Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour, also had ambitions of establishing a united Italian state. Though the Kingdom had no physical connection to Rome (seen by all as the natural capital of Italy, still the capital of the Papal States), the Kingdom had successfully challenged Austria in the Second Italian War of Independence, liberating Lombardy–Venetia from Austrian rule. The Kingdom had also established important alliances that helped improve the chances of Italian unification, such as with the United Kingdom and France in the Crimean War. Sardinia was dependent on French protection, and in 1860, Sardinia was forced to cede territory to France to maintain relations, including Garibaldi's birthplace, Nizza. This event caused the Niçard exodus, that was the emigration of a quarter of the Niçard Italians to Italy.[7]

Cavour moved to challenge republican unification efforts by Garibaldi by organizing popular revolts in the Papal States and used these revolts as a pretext to invade the country, even though the invasion angered the Roman Catholics, whom he told that the invasion was an effort to protect the Roman Catholic Church from the anti-clerical secularist nationalist republicans of Garibaldi. Only a small portion of the Papal States around Rome remained in the control of Pope Pius IX.[8] Despite their differences, Cavour agreed to include Garibaldi's Southern Italy allowing it to join the union with the Kingdom of Sardinia in 1860. Subsequently, the Parliament declared the creation of the Kingdom of Italy on 18 February 1861 (officially proclaiming it on 17 March 1861)[9] composed of both Northern Italy and Southern Italy. King Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia was then declared King of Italy, though he did not renumber himself with the assumption of the new title. This title had been out of use since the abdication of Napoleon I of France on 6 April 1814.

Following the unification of most of Italy, tensions between the royalists and republicans erupted. In April 1861, Garibaldi entered the Italian parliament and challenged Cavour's leadership, accusing him of dividing Italy, and threatened a civil war between the Kingdom in the North and his forces in the South. On 6 June 1861, the Kingdom's strongman Cavour died. During the ensuing political instability, Garibaldi and the republicans became increasingly revolutionary in tone. Garibaldi's arrest in 1862 set off worldwide controversy.[10]

In 1866, Otto von Bismarck, Minister President of Prussia, offered Victor Emmanuel II an alliance with the Kingdom of Prussia in the Austro-Prussian War. In exchange, Prussia would allow Italy to annex Austria-controlled Veneto. King Emmanuel agreed to the alliance, and the Third Italian War of Independence began. Italy fared poorly in the war with a badly-organized military against Austria, but Prussia's victory allowed Italy to annex Veneto. At this point, one major obstacle to Italian unity remained: Rome.

In 1870, Prussia went to war with France, igniting the Franco-Prussian War. To keep the large Prussian Army at bay, France abandoned its positions in Rome – which protected the remnants of the Papal States and Pius IX – to fight the Prussians. Italy benefited from Prussia's victory against France by taking over the Papal States from French authority. The Kingdom of Italy captured Rome after several battles and guerrilla-like warfare by Papal Zouaves and official troops of the Holy See against the Italian invaders. Italy's unification was completed its capital moved to Rome. Economic conditions in united Italy were poor.[11] There were no industry or transportation facilities, extreme poverty (especially in the Mezzogiorno), high illiteracy, and only a small percent of wealthy Italians had the right to vote. The unification movement relied largely on foreign powers' support and remained so afterwards.

Following the capture of Rome in 1870 from French forces of Napoleon III, Papal troops and Zouaves, relations between Italy and the Vatican remained sour for the next sixty years with the Popes declaring themselves to be prisoners in the Vatican. The Roman Catholic Church frequently protested the actions of the secular and anticlerical-influenced Italian governments, refused to meet with envoys from the King and urged Roman Catholics not to vote in Italian elections.[12] It would not be until 1929 that positive relations would be restored between the Kingdom of Italy and the Vatican after the signing of the Lateran Pacts.

Unifying multiple bureaucracies

A major challenge for the prime ministers of the new Kingdom of Italy was integrating the political and administrative systems of the seven different major components into a unified set of policies. The different regions were proud of their historical patterns and could not easily be fitted into the Sardinian model. Cavour started planning but died before it was fully developed – indeed, the challenges of administration of various bureaucracies are thought to have hastened his death. The easiest challenge was to harmonize the administrative bureaucracies of Italy's regions. They practically all followed the Napoleonic precedent, so harmonization was straightforward. The second challenge was to develop a parliamentary system. Cavour and most liberals up and down the peninsula highly admired the British system, so it became the model for Italy to this day. Harmonizing the Army and Navy was much more complex, chiefly because the systems of recruiting soldiers and selecting and promoting officers were so different and needed to be grandfathered over decades. The disorganization helps explain why the Italian naval performance in the 1866 war was so abysmal. The military system was slowly integrated over several decades. Uniforming the several diverse education systems proved complicated as well. Shortly before his death, Cavour appointed Francesco De Sanctis as minister of education. De Sanctis was an eminent scholar from the University of Naples who proved an able and patient administrator. The addition of Veneto in 1866 and Rome in 1870 further complicated the challenges of bureaucratic coordination.[13]

Culture and society

Italian society after unification and throughout most of the Liberal Period was sharply divided along class, linguistic, regional and social lines.[14] The north-south divide is still present.

On 20 September 1870, the military forces of the King of Italy overthrew what little was left of the Papal States, capturing, in particular, the city of Rome. The following year, the capital was moved from Florence to Rome. For the next 59 years after 1870, the Church denied the legitimacy of the Italian King's dominion in Rome, which it claimed rightfully belonged to the Papal States. In 1929, the dispute was settled by the Lateran Treaty, in which the King recognized Vatican City as an independent state and paid a large sum of money to compensate the Church for the loss of the Papal States.

Liberal governments generally followed a policy of limiting the role of the Roman Catholic Church and its clergy as the state confiscated church lands.[15] Similar policies were supported by such anticlerical and secular movements as republicanism, socialism, anarchism,[16] Freemasonry,[17] Lazzarettism[18] and Protestantism.

Common cultural traits in Italy at this time were social conservative in nature, including a strong belief in the family as an institution and patriarchal values. In other areas, Italian culture was divided: aristocrats and upper middle class families in Italy at this time were highly traditional, and they emphasized honor above all, with challenges to honor ending in duels. After unification, several descendants of former royal nobility became residents of Italy, comprising 7,400 noble families. Many wealthy landowners maintained a feudal-like tight control over "their" peasants. Italian society in this period remained highly divided into regional and local sub-societies, which often had historical rivalries with each other.[19]

In 1860, Italy lacked a single national language: toscano (Tuscan), which is what we now know as Italian, was only used as a literary language and in Tuscany, while outside other languages were dominant. Even the kingdom's first king, Victor Emmanuel II, was known to speak almost entirely in Piedmontese, even to his cabinet ministers.[20] Illiteracy was high, with the 1871 census indicating that 61.9% of Italian men were illiterate and 75.7% of Italian women were illiterate. This illiteracy rate was far higher than in western European countries in the same period. Also, no national popular press was possible due to the diversity of regional languages.[21]

Italy had very few public schools upon unification, so the Italian government in the Liberal Period attempted to increase literacy by establishing state-funded schools to teach the official Italian language.[22]

Living standards were low during the Liberal Period, especially in southern Italy, due to various diseases such as malaria and epidemics that occurred during the period. There was initially a high death rate in 1871 at 30 people dying per 1,000, though this reduced to 24.2 per 1,000 by the 1890s. In addition, the mortality rate of children dying in their first year after birth in 1871 was 22.7 percent, while the number of children dying before reaching their fifth birthday was very high at 50 percent. The mortality rate of children dying in their first year after birth decreased to an average of 17.6 percent from 1891 to 1900.[23]

Economy

In terms of the entire period, Giovanni Federico has argued that Italy was not economically backward, for there was substantial development at various times between 1860 and 1940. Unlike most modern nations that relied on large corporations, industrial growth in Italy was a product of the entrepreneurial efforts of small, family-owned firms that succeeded in a local competitive environment.[24]

Political unification did not systematically bring economic integration, as Italy faced serious economic problems and economic division along political, social and regional lines. In the Liberal Period, Italy remained highly economically dependent on foreign trade and the international price of coal and grain.[25]

Upon unifying, Italy had a predominantly agrarian society as 60% of the active population worked in agriculture. Advances in technology, the sale of vast Church estates, foreign competition, and export opportunities rapidly transformed the agricultural sector in Italy shortly after unification. However, these developments did not benefit all of Italy in this period, as southern Italy's agriculture suffered from hot summers and drought. At the same time, the presence of malaria prevented the cultivation of low-lying areas along Italy's Adriatic Sea coast.[26]

The overwhelming attention paid to foreign policy alienated the agricultural community in Italy which had been in decline since 1873. Both radical and conservative forces in the Italian parliament demanded that the government investigate how to improve agriculture in Italy. The investigation, which started in 1877 and was released eight years later, showed that agriculture was not improving and that landowners were earning revenue from their lands and contributing almost nothing to the development of the land. The break-up of communal lands hurt lower-class Italians to the benefit of landlords. Most of the workers on the agricultural lands were not peasants, but short-term laborers (braccianti) who, at best, were employed for one year. Peasants without stable income were forced to rely on meagre food supplies, the disease[further explanation needed] was spreading rapidly, and plagues were reported, including a major cholera epidemic which killed at least 55,000 people.[27]

The Italian government could not deal with the situation effectively because of its massive debt. Italy suffered economically also as a consequence of the overproduction of grapes. In the 1870s and 1880s, France's vineyard industry was suffering from vine disease caused by pests. Italy prospered as the largest exporter of wine in Europe. Still, following the recovery of France in 1888, Southern Italy was overproducing and had to cut back, which caused greater unemployment and bankruptcies.[28]

The Italian government invested heavily in developing railways in the 1870s, more than doubling the existing length of railway line between 1870 and 1890.[25]

Il Mezzogiorno (Southern Italy)

Italy's population remained severely divided between wealthy elites and impoverished workers, especially in the South. An 1881 census found that over 1 million southern day-laborers were chronically under-employed and likely to become seasonal emigrants to sustain themselves economically.[29] Southern peasants, as well as small landowners and tenants, often were in a state of conflict and revolt throughout the late 19th century.[30] There were exceptions to the generally poor economic condition of agricultural workers of the South, as some regions near cities such as Naples and Palermo as well as along the Tyrrhenian Sea coast.[29]

From the 1870s onward, intellectuals, scholars and politicians examined the economic and social conditions of Southern Italy (Il Mezzogiorno), a movement known as meridionalismo ("Meridionalism"). For example, the 1910 Commission of Inquiry into the South indicated that the Italian government thus far had failed to ameliorate the severe economic differences. The limited voting rights only to those with sufficient property allowed rich landowners to exploit the poor.[31]

Liberal era of politics (1870–1914)

After unification, Italy's politics favored liberalism:[a] the liberal-conservative right (destra storica or Historical Right) was regionally fragmented[b] and liberal-conservative Prime Minister Marco Minghetti only held on to power by enacting revolutionary and left-leaning policies (such as the nationalization of railways) to appease the opposition.

Agostino Depretis

In 1876, Minghetti was ousted and replaced by liberal Agostino Depretis, who began the long Liberal Period. The Liberal Period was marked by corruption, government instability, continued poverty in Southern Italy and the use of authoritarian measures by the Italian government.

Depretis began his term as Prime Minister by initiating an experimental political notion known as trasformismo ("transformism"). The theory of trasformismo was that a cabinet should select a variety of moderates and capable politicians from a non-partisan perspective. In practice, trasformismo was authoritarian and corrupt as Depretis pressured districts to vote for his candidates if they wished to gain favourable concessions from Depretis when in power. The results of the Italian general election of 1876 resulted in only four representatives from the right being elected, allowing the government to be dominated by Depretis. Despotic and corrupt actions are believed to be the key means by which Depretis managed to keep support in Southern Italy. Depretis put through authoritarian measures, such as banning public meetings, placing "dangerous" individuals in internal exile on remote penal islands across Italy and adopting militarist policies. Depretis enacted controversial legislation for the time, such as abolishing arrest for debt and making elementary education free and compulsory while ending compulsory religious teaching in elementary schools.[32]

In 1887, Francesco Crispi became Prime Minister and began focusing government efforts on foreign policy. Crispi worked to build Italy as a great world power through increased military expenditures, advocacy of expansionism[33] and trying to win the favor of Germany. Italy joined the Triple Alliance, which included both Germany and Austria-Hungary in 1882 and which remained officially intact until 1915. While helping Italy develop strategically, he continued trasformismo and became authoritarian, once suggesting the use of martial law to ban opposition parties.[34] Despite being authoritarian, Crispi put through liberal policies such as the Public Health Act of 1888 and established tribunals for redress against abuses by the government.[35]

Francesco Crispi

Francesco Crispi was Prime Minister for a total of six years, from 1887 until 1891 and again from 1893 until 1896. Historian R. J. B. Bosworth says of his foreign policy:

Crispi pursued policies whose openly aggressive character would not be equaled until the days of the Fascist regime. Crispi increased military expenditure, talked cheerfully of a European conflagration, and alarmed his German or British friends with signs of preventative attacks on his enemies. His policies were ruinous for Italy's trade with France and, more humiliatingly, for colonial ambitions in Eastern Africa. Crispi's lust for territory there was thwarted when on 1 March 1896, the armies of Ethiopian Emperor Menelik routed Italian forces at Adowa [...] an unparalleled disaster for a modern army. Crispi, whose private life (he was perhaps a trigamist) and personal finances [...] were objects of perennial scandal, went into dishonorable retirement.[36]

Crispi greatly admired the United Kingdom, but was unable to get British assistance for his aggressive foreign policy and turned instead to Germany.[37] Crispi also enlarged the army and navy and advocated expansionism as he sought Germany's favor by joining the Triple Alliance which included both Germany and Austria-Hungary in 1882. It remained officially intact until 1915 and prevented hostilities between Italy and Austria, which controlled border regions that Italy claimed.

Colonialism

In the late 19th and early 20th century, Italy emulated the Great Powers in acquiring colonies, especially in the scramble to take control of Africa that took place in the 1870s. Italy was weak in military and economic resources compared to Britain, France and Germany. Still, it proved difficult due to popular resistance. It was unprofitable due to high military costs and the lesser economic value of spheres of influence remaining when Italy began to colonize. Britain was eager to block French influence and assisted Italy in gaining territory of the Red Sea.[38]

Several colonial projects were undertaken by the government. These were done to gain the support of Italian nationalists and imperialists, who wanted to rebuild a Roman Empire. Italy had already large settlements in Alexandria, Cairo and Tunis. Italy first attempted to gain colonies through negotiations with other world powers to make colonial concessions, but these negotiations failed. Italy also sent missionaries to uncolonized lands to investigate the potential for Italian colonization. The most promising and realistic of these were parts of Africa. Italian missionaries had already established a foothold at Massawa (in present-day Eritrea) in the 1830s and had entered deep into the Ethiopian Empire.[39]

The beginning of colonialism came in 1885, shortly after the fall of Egyptian rule in Khartoum, when Italy landed soldiers at Massawa in East Africa. In 1888, Italy annexed Massawa by force, creating the colony of Italian Eritrea. The Eritrean ports of Massawa and Assab handled trade with Italy and Ethiopia. The trade was promoted by the low duties paid on Italian trade. Italy exported manufactured products and imported coffee, beeswax and hides.[40] At the same time, Italy occupied territory on the south side of the horn of Africa, forming what would become Italian Somaliland.

The Treaty of Wuchale, signed in 1889, stated in the Italian language version that Ethiopia was to become an Italian protectorate, while the Ethiopian Amharic language version stated that the Ethiopian Emperor Menelik II could go through Italy to conduct foreign affairs. This happened presumably due to the mistranslation of a verb, which formed a permissive clause in Amharic and a mandatory one in Italian.[41] When the differences in the versions came to light, in 1895 Menelik II abrogated the treaty and abandoned the agreement to follow Italian foreign policy; Italy used this renunciation as a reason to invade Ethiopia.[42] Ethiopia gained the help of the Russian Empire, whose own interests in East Africa led the government of Nicholas II of Russia to send large amounts of modern weaponry to the Ethiopians to hold back an Italian invasion. In response, Britain decided to back the Italians to challenge Russian influence in Africa and declared that all of Ethiopia was within the sphere of Italian interest. On the verge of war, Italian militarism and nationalism reached a peak, with Italians flocking to the Royal Italian Army, hoping to take part in the upcoming war.[43]

The Italian army failed on the battlefield and was overwhelmed by a huge Ethiopian army at the Battle of Adwa. At that point, the Italian invasion force was forced to retreat into Eritrea. The war formally ended with the Treaty of Addis Ababa in 1896, which abrogated the Treaty of Wuchale, recognizing Ethiopia as an independent country. The failed Ethiopian campaign was one of the few military victories scored by the Africans against an imperial power at this time.[44]

From 2 November 1899 to 7 September 1901, Italy participated as part of the Eight-Nation Alliance forces during the Boxer Rebellion in China. On 7 September 1901, a concession in Tientsin was ceded to Italy by the Qing Dynasty. On 7 June 1902, the concession was taken into Italian possession and administered by an Italian consul.

In 1911, Italy declared war on the Ottoman Empire and invaded Tripolitania, Fezzan and Cyrenaica. These provinces together formed what became known as Libya. The war ended only one year later, but the occupation resulted in acts of discrimination against Libyans, such as the forced deportation of Libyans to the Tremiti Islands in October 1911. By 1912, one-third of these Libyan refugees had died from a lack of food and shelter.[45] The annexation of Libya led nationalists to advocate Italian domination of the Mediterranean Sea by occupying Greece and the Adriatic Sea coastal region of Dalmatia.[46]

Giovanni Giolitti

In 1892, Giovanni Giolitti became Prime Minister of Italy for his first term. Although his first government quickly collapsed one year later, Giolitti returned in 1903 to lead Italy's government during a fragmented period until 1914. Giolitti had spent his earlier life as a civil servant and then took positions within the cabinets of Crispi. Giolitti was the first long-term Italian Prime Minister because he mastered the political concept of trasformismo by manipulating, coercing and bribing officials to his side. In elections during Giolitti's government, voting fraud was common. Giolitti helped improve voting only in well-off, more supportive areas while attempting to isolate and intimidate poor areas where opposition was strong.[47] Southern Italy was in terrible shape before and during Giolitti's tenure as Prime Minister: four-fifths of southern Italians were illiterate, and the dire situation there ranged from problems of large numbers of absentee landlords to rebellion and even starvation.[48] Corruption was such a large problem that Giolitti himself admitted that there were places "where the law does not operate at all".[49]

In 1911, Giolitti's government sent forces to occupy Libya. While the success of the Libyan War improved the status of the nationalists, it did not help Giolitti's administration as a whole. The government attempted to discourage criticism by speaking about Italy's strategic achievements and inventiveness of their military in the war: Italy was the first country to use the airship for military purposes and undertook aerial bombing on the Ottoman forces.[50] The war radicalized the Italian Socialist Party, and anti-war revolutionaries called for violence to bring down the government. Elections were held in 1913, and Giolitti's coalition retained an absolute majority in the Chamber of Deputies, while the Radical Party emerged as the largest opposition bloc. The Italian Socialist Party gained eight seats and was the largest party in Emilia-Romagna.[51] Giolitti's coalition did not endure long after the election, and he was forced to resign in March 1914. Giolitti later returned as Prime Minister only briefly in 1920, but the era of liberalism was effectively over in Italy.

The 1913 and 1919 elections saw gains made by Socialist, Catholic and nationalist parties at the expense of the traditionally dominant Liberals and Radicals, who were increasingly fractured and weakened as a result.

World War I and failure of the liberal state (1915–1922)

Prelude to war and internal dilemma

In the lead-up to World War I, the Kingdom of Italy faced many short- and long-term problems in determining its allies and objectives. Italy's recent success in occupying Libya as a result of the Italo-Turkish War had sparked tension with its Triple Alliance allies, Germany and Austria-Hungary, because both countries had been seeking closer relations with the Ottoman Empire. In Munich, Germans reacted to Italy's aggression by singing anti-Italian songs.[52] Italy's relations with France were also in bad shape: France felt betrayed by Italy's support of Prussia in the Franco-Prussian War, opening the possibility of war erupting between the two countries.[53] Italy's relations with the United Kingdom had also been impaired by constant Italian demands for more recognition on the international stage following the occupation of Libya and its demands that other nations accept its spheres of influence in Eastern Africa and the Mediterranean Sea.[54]

In the Mediterranean Sea, Italy's relations with the Kingdom of Greece were aggravated when Italy occupied the Greek-populated Dodecanese Islands, including Rhodes, from 1912 to 1914. The Ottoman Empire had formerly controlled these islands. Italy and Greece were also in open rivalry over the desire to occupy Albania.[55] King Victor Emmanuel III himself was uneasy about Italy pursuing distant colonial adventures and said that Italy should prepare to take back Italian-populated land from Austria-Hungary as the "completion of the Risorgimento".[56] This idea put Italy at odds with Austria-Hungary.

A major hindrance to Italy's decision on what to do about the war was the political instability throughout Italy in 1914. After the formation of the government of Prime Minister Antonio Salandra in March 1914, the government attempted to win the support of nationalists. It moved to the political right.[57] At the same time, the left became more repulsed by the government after the killing of three anti-militarist demonstrators in June.[57] Many elements of the left including syndicalists, republicans, and anarchists protested against this and the Italian Socialist Party declared a general strike in Italy.[58] The protests that ensued became known as "Red Week" as leftists rioted and various acts of civil disobedience occurred in major cities and small towns such as seizing railway stations, cutting telephone wires and burning tax-registers.[57] However, only two days later the strike was officially called off, though the civil strife continued. Militarist nationalists and anti-militarist leftists fought on the streets until the Italian Royal Army forcefully restored calm after using thousands of men to put down the various protesting forces.[57] Following the invasion of Serbia by Austria-Hungary in 1914, World War I broke out. Despite Italy's official alliance with Germany and membership in the Triple Alliance, the Kingdom of Italy initially remained neutral, claiming that the Triple Alliance was only for defensive purposes.[59]

In Italy, society was divided over the war: Italian socialists generally opposed the war and supported pacifism, while nationalists militantly supported the war. Long-time nationalists Gabriele D'Annunzio and Luigi Federzoni, together with a former socialist journalist and new convert to nationalist sentiment, future Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini, demanded that Italy join the war. For nationalists, Italy had to maintain its alliance with the Central Powers to gain colonial territories at the expense of France. For the liberals, the war presented Italy a long-awaited opportunity to use an alliance with the Entente to gain certain Italian-populated and other territories from Austria-Hungary, which had long been part of Italian patriotic aims since unification. In 1915, relatives of Italian revolutionary and republican hero Giuseppe Garibaldi died on the battlefield of France, where they had volunteered to fight. Federzoni used the memorial services to declare the importance of Italy joining the war and to warn the monarchy of the consequences of continued disunity in Italy if it did not:

Italy has awaited this since 1866 her truly a national war, to feel unified, at last, renewed by the unanimous action and identical sacrifice of all her sons. Today, while Italy still wavers before the necessity imposed by history, the name of Garibaldi, resanctified by blood, rises again to warn her that she will not be able to defeat the revolution save by fighting and winning her national war.

– Luigi Federzoni, 1915[60]

Mussolini used his new newspaper Il Popolo d'Italia and his strong oratorical skills to urge a broad political audience – ranging from right-wing nationalists to patriotic revolutionary leftists – to support Italy's entry into the war to gain back Italian-populated territories from Austria-Hungary, by saying "enough of Libya, and on to Trento and Trieste".[60] Although the left was traditionally opposed to war, Mussolini claimed that this time it was in their interest to join the war to tear down the aristocratic Hohenzollern dynasty of Germany which he claimed was the enemy of all European workers.[61] Mussolini and other nationalists warned the Italian government that Italy must join the war or face revolution and called for violence against pacifists and neutralists.[62]

With nationalist sentiment firmly on the side of reclaiming Italian territories of Austria-Hungary, Italy entered negotiations with the Triple Entente. The negotiations ended successfully in April 1915 when the London Pact was brokered with the Italian government. The pact ensured Italy the right to attain all Italian-populated lands it wanted from Austria-Hungary, as well as concessions in the Balkan Peninsula and suitable compensation for any territory gained by the United Kingdom and France from Germany in Africa.[3] The proposal fulfilled the desires of Italian nationalists and Italian imperialism and was agreed to. Italy joined the Triple Entente in its war against Austria-Hungary.

The reaction in Italy was divided: former Prime Minister Giovanni Giolitti was furious over Italy's decision to go to war against its former allies, Germany and Austria-Hungary. Giolitti claimed that Italy would fail in the war, predicting high numbers of mutinies, Austro-Hungarian occupation of even more Italian territory and that the failure would produce a catastrophic rebellion that would destroy the liberal-democratic monarchy and the liberal-democratic secular institutions of the state.[63]

Italy's war effort

The outset of the campaign against Austria-Hungary looked to initially favor Italy: Austria-Hungary's army was spread to cover its fronts with Serbia and Russia and Italy had a numerical superiority against the Austro-Hungarian Army. However, this advantage was never fully utilized because Italian military commander Luigi Cadorna insisted on a dangerous frontal assault against Austria-Hungary in an attempt to occupy the Slovenian plateau and Ljubljana. This assault would put the Italian army not far away from Austria-Hungary's imperial capital, Vienna. After eleven offensives with an enormous loss of life and the final victory of the Central Powers, the Italian campaign to take Vienna collapsed.

Upon entering the war, geography was also difficult for Italy as its border with Austria-Hungary was along mountainous terrain. In May 1915, Italian forces at 400,000 men along the border outnumbered the Austrian and Germans almost four to one.[64] However, Austrian defences hold off the Italian offensive.[65] The battles with the Austro-Hungarian Army along the Alpine foothills in trench warfare were drawn-out, long engagements with little progress.[66] Italian officers were poorly trained in contrast to the Austro-Hungarian and German armies, Italian artillery was inferior to the Austrian machine guns, and the Italian forces had a dangerously low supply of ammunition; this shortage would continually hamper attempts to make advances into Austrian territory.[65] This combined with the constant replacement of officers by Cadorna resulted in few officers gaining the experience necessary to lead military missions.[67] In the first year of the war, poor conditions on the battlefield led to cholera outbreaks, causing many Italian soldiers to die.[68] Despite these serious problems, Cadorna refused to back down on the strategy of offence. Naval battles occurred between the Italian Royal Navy (Regia Marina) and the Austro-Hungarian Navy. The Austro-Hungarian fleet outclassed Italy's warships, and the situation was made direr for Italy in that both the French Navy and the (British) Royal Navy were not sent into the Adriatic Sea. Their respective governments viewed the Adriatic Sea as "far too dangerous to operate in due to the concentration of the Austro-Hungarian fleet there".[68]

Morale fell among Italian soldiers who lived a tedious life when not on the front lines, as they were forbidden to enter theaters or bars, even when on leave. However, alcohol was made freely available to the soldiers when battles were about to occur. Groups of soldiers worked to create improvized whorehouses.[69] To maintain morale, the Italian army had propaganda lectures on the importance of the war to Italy, especially to retrieve Trento and Trieste from Austria-Hungary.[69] Some of these lectures were carried out by popular nationalist war proponents such as Gabriele D'Annunzio. D'Annunzio himself would participate in several paramilitary raids on Austrian positions along the Adriatic Sea coastline during the war and temporarily lost his sight after an air raid.[70] Prominent pro-war advocate Benito Mussolini was prevented from giving lectures by the government, most likely because of his revolutionary socialist past.[69]

The Italian government became increasingly aggravated in 1915 with the passive nature of the Serbian army, which had not engaged in a serious offensive against Austria-Hungary for months.[71] The Italian government blamed Serbian military inactiveness for allowing the Austro-Hungarians to muster their armies against Italy.[72] Cadorna suspected that Serbia was attempting to negotiate an end to fighting with Austria-Hungary and addressed this to foreign minister Sidney Sonnino, who himself bitterly claimed that Serbia was an unreliable ally.[72] Relations between Italy and Serbia became so cold that the other Allied nations were forced to abandon the idea of forming a united Balkan front against Austria-Hungary.[72] In negotiations, Sonnino remained prepared to allow Bosnia to join Serbia, but refused to discuss the fate of Dalmatia, which was claimed both by Italy and by Pan-Slavists in Serbia.[72] As Serbia fell to the Austro-Hungarian and German forces in 1915, Cadorna proposed sending 60,000 men to land in Thessaloniki to help the Serbs now in exile in Greece and the Principality of Albania to fight off the opposing forces, but the Italian government's bitterness to Serbia resulted in the proposal being rejected.[72]

In the spring of 1916, Austro-Hungarians counterattacked in the Altopiano of Asiago, towards Verona and Padova, in their Strafexpedition, but were defeated by the Italians. In August, after the Battle of Doberdò, the Italians also captured the town of Gorizia; the front remained static for over a year. At the same time, Italy faced a shortage of warships, increased attacks by submarines, soaring freight charges threatening the ability to supply food to soldiers, lack of raw materials and equipment, and Italians faced high wartime taxes.[73] Austro-Hungarian and German forces had gone deep into Northern Italian territory. Finally, in November 1916, Cadorna ceased offensive operations and began a defensive approach. In 1917, France, the United Kingdom and the United States offered to send troops to Italy to help it fend off the offensive of the Central Powers. Still, the Italian government refused as Sonnino did not want Italy to be seen as a client state of the Allies and preferred isolation as the more brave alternative.[74] Italy also wanted to keep Greece out of the war as the Italian government feared that, should Greece the Allies, it would move to annex Italian-claimed Albania.[75] The Venizelist pro-war advocates in Greece failed to succeed in pressuring Constantine I of Greece to bring Italy into the conflict, and Italian aims on Albania remained unthreatened.[75]

The Russian Empire collapsed in 1917 Russian Revolution, eventually resulting in the rise of the communist Bolshevik regime of Vladimir Lenin. The resulting marginalization of the Eastern Front allowed for more Austro-Hungarian and German forces to arrive on the front against Italy. Internal dissent against the war grew with increasingly poor economic and social conditions in Italy due to the strain of the war. Much of the profit of the war was being made in the cities, while rural areas were losing income.[76] The number of men available for agricultural work had fallen from 4.8 million to 2.2 million, though with the help of women, agricultural production managed to be maintained at 90% of its pre-war total during the war.[77] Many pacifists and internationalist Italian socialists turned to Bolshevism and advocated negotiations with the workers of Germany and Austria-Hungary to help end the war and bring about Bolshevik revolutions.[77] Avanti!, the newspaper of the Italian Socialist Party, declared: "Let the bourgeoisie fight its war".[78] Leftist women in Northern Italian cities led protests demanding action against the high cost of living and demanding an end to the war.[79] In Milan in May 1917, communist revolutionaries organized and engaged in rioting, calling for an end to the war and managed to close down factories and stop public transportation.[80] The Italian Army was forced to enter Milan with tanks and machine guns to face communists and anarchists who fought violently until 23 May, when the Army gained control of the city with almost 50 people killed (three of which were Italian soldiers) and over 800 people arrested.[80]

After the disastrous Battle of Caporetto in 1917, Italian forces were forced far back into Italian territory as far as the Piave river. The humiliation led to the appointment of Vittorio Emanuele Orlando as Prime Minister, who managed to solve some of Italy's wartime problems. Orlando abandoned the previous isolationist approach to the war and increased coordination with the Allies. The convoy system was introduced to fend off submarine attacks and allowed Italy to end food shortages from February 1918 onward. Also, Italy received more raw materials from the Allies.[82] The new Italian chief of staff, Armando Diaz, ordered the Army to defend the Monte Grappa summit, where fortified defences were constructed; despite numerically inferior, the Italians managed to repel the Austro-Hungarian and German Army. 1918 also saw the beginning of the official suppression of enemy aliens. The Italian government increasingly suppressed the Italian socialists.

At the Battle of the Piave River, the Italian Army managed to hold off the Austro-Hungarian and German armies. The opposing armies repeatedly failed afterwards in major battles such as Battle of Monte Grappa and the Battle of Vittorio Veneto. After four days, the Italian Army defeated the Austro-Hungarian Army in the latter battle, aided by British and French divisions and the fact that the Imperial-Royal Army started to melt away as news arrived that the constituent regions of the Dual Monarchy had declared independence. Austria-Hungary ended the fighting against Italy with the armistice on 4 November 1918, one week before the 11 November armistice on the Western front.

The Italian government was infuriated by the Fourteen Points of Woodrow Wilson, the President of the United States, as advocating national self-determination which meant that Italy would not gain Dalmatia as had been promised in the Treaty of London.[83] In the Parliament of Italy, nationalists condemned Wilson's fourteen points as betraying the Treaty of London, while socialists claimed that Wilson's points were valid and claimed the Treaty of London was an offense to the rights of Slavs, Greeks and Albanians.[83] Negotiations between Italy and the Allies, particularly the new Yugoslav delegation (replacing the Serbian delegation), agreed to a trade off between Italy and the new Kingdom of Yugoslavia, which was that Dalmatia, despite being claimed by Italy, would be accepted as Yugoslav, while Istria, claimed by Yugoslavia, would be accepted as Italian.[84]

During the war, the Italian Royal Army increased in size from 15,000 men in 1914 to 160,000 men in 1918, with 5 million recruits in total entering service during the war.[67] This came at a terrible cost: by the end of the war, Italy had lost 700,000 soldiers and had a budget deficit of twelve billion lira. Italian society was divided between the majority of pacifists who opposed Italian involvement in the war and the minority of pro-war nationalists who had condemned the Italian government for not having immediately gone to war with Austria-Hungary in 1914.

Italy's territorial settlements and the reaction

As the war came to an end, Italian Prime Minister Vittorio Emanuele Orlando met with British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, Prime Minister of France Georges Clemenceau and United States President Woodrow Wilson in Versailles to discuss how the borders of Europe should be redefined to help avoid a future European war.

The talks provided little territorial gain to Italy because, during the peace talks, Wilson promised freedom to all European nationalities to form their nation-states. As a result, the Treaty of Versailles did not assign Dalmatia and Albania to Italy as had been promised in the Treaty of London. Furthermore, the British and French decided to divide the German overseas colonies into their mandates, with Italy receiving none of them. Italy also gained no territory from the breakup of the Ottoman Empire, despite a proposal being issued to Italy by the United Kingdom and France during the war, only to see these nations carve up the Ottoman Empire between themselves (also exploiting the forces of the Arab Revolt). Despite this, Orlando agreed to sign the Treaty of Versailles, which caused uproar against his government. Civil unrest erupted in Italy between nationalists who supported the war effort and opposed the "mutilated victory" (as nationalists referred to it) and leftists who were opposed to the war.[85]

Furious over the peace settlement, the Italian nationalist poet Gabriele D'Annunzio led disaffected war veterans and nationalists to form the Free State of Fiume in September 1919. His popularity among nationalists led him to be called Il Duce ("The Leader"), and he used black-shirted paramilitary in his assault on Fiume. The leadership title of Duce and the blackshirt paramilitary uniform would later be adopted by the Fascist movement of Benito Mussolini. The demand for the Italian annexation of Fiume spread to all sides of the political spectrum, including Mussolini's Fascists.[86] D'Annunzio's stirring speeches drew Croat nationalists to his side and also kept contact with the Irish Republican Army and Egyptian nationalists.[87]

Italy annexed territories that included not only ethnically-mixed places but also exclusively ethnic Slovene and Croat places, especially within the former Austrian Littoral and the former Duchy of Carniola. They included one-third of the entire territory inhabited by Slovenes at the time and one-quarter of the entire Slovene population,[88] who was during the 20 years long period of Italian Fascism (1922–1943) subjected to forced Italianization alongside 25,000 ethnic Germans. According to author Paul N. Hehn, "the treaty left half a million Slavs inside Italy, while only a few hundred Italians in the fledgling Yugoslav (i.e. Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes renamed Yugoslavia in 1929) state".[89]

Fascist regime (1922–1943)

| Part of a series on |

| Fascism |

|---|

|

Mussolini in war and postwar

In 1914, Benito Mussolini was forced out of the Italian Socialist Party after calling for Italian intervention in the war against Austria-Hungary. Before World War I, Mussolini had opposed military conscription, protested against Italy's occupation of Libya and was the editor of the Socialist Party's official newspaper, Avanti!, but over time he simply called for revolution without mentioning class struggle.[90] In 1914, Mussolini's nationalism enabled him to raise funds from Ansaldo (an armaments firm) and other companies to create his newspaper, Il Popolo d'Italia, which at first attempted to convince socialists and revolutionaries to support the war.[91] The Allied Powers, eager to draw Italy to the war, helped finance the newspaper.[92] Later, after the war, this publication would become the official newspaper of the Fascist movement. During the war, Mussolini served in the Army and was wounded once.[93]

Following the end of the war and the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, Mussolini created the Fasci di Combattimento or Combat League. It was originally dominated by patriotic socialist and syndicalist veterans who opposed the pacifist policies of the Italian Socialist Party. This early Fascist movement had a platform more inclined to the left, promising social revolution, proportional representation in elections, women's suffrage (partly realized in 1925) and dividing rural private property held by estates.[94][95] They also differed from later Fascism by opposing censorship, militarism and dictatorship.[96] Mussolini claimed that "we are libertarians above all, loving liberty for everyone, even for our enemies" and said that freedom of thought and speech were among the "highest expressions of human civilization."[97]

On 15 April 1919, the Fascists made their debut in political violence when a group of members from the Fasci di Combattimento attacked the offices of Avanti!. But they found little public support, and in the elections of November 1919, the Fascists suffered a heavy defeat, accompanied by a rapid loss of membership.[98] In response, Mussolini moved the organization away from the left and turned the revolutionary movement into an electoral movement in 1921 named the Partito Nazionale Fascista (National Fascist Party). The party echoed the nationalist themes of D'Annunzio and rejected parliamentary democracy while still operating within it in order to destroy it. Mussolini changed his original revolutionary policies, such as moving away from anti-clericalism to supporting the Roman Catholic Church and abandoned his public opposition to the monarchy.[99] Support for the Fascists began to grow in 1921, and pro-Fascist army officers began taking arms and vehicles from the army to use in counter-revolutionary attacks on socialists.[100]

In 1920, Giolitti came back as Prime Minister in an attempt to solve the deadlock. One year later, Giolitti's government had become unstable, and a growing socialist opposition further endangered his government. Giolitti believed that the Fascists could be toned down and used to protect the state from the socialists. He decided to include Fascists on his electoral list for the 1921 elections.[99] In the elections, the Fascists did not make large gains. Still, Giolitti's government failed to gather a large enough coalition to govern and offered the Fascists placements in his government. The Fascists rejected Giolitti's offers, forcing him to resign as his coalition no longer had enough support in parliament.[101] Many descendants of those who had served Garibaldi's revolutionaries during unification were won over to Mussolini's nationalist revolutionary ideals.[102] His advocacy of corporatism and futurism had attracted advocates of the "third way",[102] but most importantly, he had won over politicians like Facta and Giolitti. He did not condemn him for his Blackshirts' mistreatment of socialists.[103]

March on Rome and the Fascist government

In October 1922, Mussolini took advantage of a general strike by workers and announced his demands to the government to give the Fascist Party political power or face a coup. With no immediate response, a small number of Fascists began a long trek across Italy to Rome, which was known as the "March on Rome", claiming to Italians that Fascists intended to restore law and order. Mussolini himself did not participate until the very end of the march, with D'Annunzio being hailed as the leader of the march until it was learned that he had been pushed out of a window and severely wounded in a failed assassination attempt, depriving him of the possibility of leading an actual coup d'état orchestrated by an organization founded by himself. Under the leadership of Mussolini, the Fascists demanded Prime Minister Luigi Facta's resignation and that Mussolini be named Prime Minister. Although the Italian Army was far better armed than the Fascist paramilitaries, the Italian government under King Vittorio Emmanuele III faced a political crisis. The King was forced to decide which of the two rival movements in Italy would form the new government: Mussolini's Fascists or the anti-royalist Italian Socialist Party, ultimately deciding to endorse the Fascists.[104][105]

On 28 October 1922, the King invited Mussolini to become Prime Minister, allowing Mussolini and the Fascist Party to pursue their political ambitions as long as they supported the monarchy and its interests. At 39, Mussolini was young compared to other Italian and European leaders. His supporters named him Il Duce ("The Leader"). A personality cult was developed that portrayed him as the nation's saviour, aided by the personal popularity he held with Italians already, which would remain strong until Italy faced continuous military defeats in World War II.

Upon taking power, Mussolini formed a legislative coalition with nationalists, liberals and populists. However, goodwill by the Fascists towards parliamentary democracy faded quickly: Mussolini's coalition passed the electoral Acerbo Law of 1923, which gave two-thirds of the seats in parliament to the party or coalition that achieved 25% of the vote. The Fascist Party used violence and intimidation to achieve the 25% threshold in the 1924 election and became the ruling political party of Italy.

Following the election, Socialist deputy Giacomo Matteotti was assassinated after calling for an annulment of the elections because of the irregularities. Following the assassination, the Socialists walked out of parliament, allowing Mussolini to pass more authoritarian laws. On 3 January 1925, in a speech held at the Parliament, Mussolini accepted responsibility for the Fascist violence in 1924 and promised that dissenters would be dealt with harshly. Before the speech, Blackshirts smashed opposition presses and beat up several of Mussolini's opponents. This event is considered the onset of undisguised Fascist dictatorship in Italy, though it would be 1928 before the Fascist Party was formally declared the only legal party in the country.

Over the next four years, Mussolini eliminated nearly all checks and balances on his power. In 1926, Mussolini passed a law that declared he was responsible only to the King and made him the sole person able to determine Parliament's agenda. The fact that Mussolini had to pass such a law underscored how firmly the convention of parliamentary rule had been established; as mentioned above, the letter of the Statuto made ministers solely responsible to the King. Local autonomy was swept away; appointed podestas replaced communal mayors and councils. Soon after all other parties were banned in 1928, parliamentary elections were replaced by plebiscites in which the Grand Council nominated a single list of candidates. Mussolini wielded enormous political powers as the effective ruler of Italy. The King was a figurehead and handled ceremonial roles. However, he retained the power to dismiss the Prime Minister on the advice of the Grand Council, on paper the only check on Mussolini's power – which is what happened in 1943.

World War II and the fall of fascism

When Germany invaded Poland on 1 September 1939 beginning World War II, Mussolini publicly declared on 24 September 1939 that Italy had the choice of entering the war or to remain neutral which would cause the country to lose its national dignity. Nevertheless, despite his aggressive posture, Mussolini kept Italy out of the conflict for several months. Mussolini told his son-in-law Count Ciano that he was personally jealous of Hitler's accomplishments and hoped that Hitler's prowess would be slowed down by the Allied counterattack.[106] Mussolini went so far as to lessen Germany's successes in Europe by giving advanced notice to Belgium and the Netherlands of an imminent German invasion, of which Germany had informed Italy.[106]

In drawing out war plans, Mussolini and the Fascist regime decided that Italy would aim to annex large portions of Africa and the Middle East to be included in its colonial empire. Hesitance remained from the King and military commander Pietro Badoglio, who warned Mussolini that Italy had too few tanks, armoured vehicles and aircraft available to be able to carry out a long-term war; Badoglio told Mussolini "It is suicide" for Italy to get involved in the European conflict.[107] Mussolini and the Fascist regime took the advice to a degree and waited as Germany invaded France before getting involved.

As France collapsed under the German Blitzkrieg, Italy declared war on France and Britain on 10 June 1940, fulfilling its obligations of the Pact of Steel. Italy hoped to conquer Savoia, Nizza, Corsica, and the African colonies of Tunisia and Algeria from the French, but this was quickly stopped when Germany signed an armistice with the French commander Philippe Petain who established Vichy France which retained control over these territories. This decision by Nazi Germany angered Mussolini's Fascist regime.[108]

The one Italian strength that concerned the Allies was the Italian Royal Navy (Regia Marina), the fourth-largest navy in the world at the time. In November 1940, the British Royal Navy launched a surprise air attack on the Italian fleet at Taranto, which crippled Italy's major warships. Although the Italian fleet did not inflict serious damage as was feared, it did keep significant British Commonwealth naval forces in the Mediterranean Sea. This fleet needed to fight the Italian fleet to keep British Commonwealth forces in Egypt and the Middle East from being cut off from Britain. In 1941 on the Italian-controlled island of Kastelorizo, off of the coast of Turkey, Italian forces succeeded in repelling British and Australian forces attempting to occupy the island during Operation Abstention. In December 1941, a covert attack by Italian forces took place in Alexandria, Egypt, in which Italian divers attached explosives to British warships resulting in two British battleships being severely damaged. This was known as the Raid on Alexandria. In 1942, the Italian navy inflicted a serious blow to a British convoy fleet attempting to reach Malta during Operation Harpoon, sinking multiple British vessels. Over time, the Allied navies inflicted serious damage on the Italian fleet and ruined Italy's advantage over Germany.

Continuing indications of Italy's subordinate nature to Germany arose during the Greco-Italian War; the British air force prevented the Italian invasion and allowed the Greeks to push the Italians back to Albania. Mussolini had intended the war with Greece to prove to Germany that Italy was no minor power in the alliance but a capable empire which could hold its weight. Mussolini boasted to his government that he would even resign from being Italian if anyone found fighting the Greeks to be difficult.[109] Hitler and the German government were frustrated with Italy's failing campaigns, but so was Mussolini. Mussolini, in private, angrily accused Italians on the battlefield of becoming "overcome with a crisis of artistic sentimentalism and throwing in the towel".[110]

To gain background in Greece, Germany reluctantly began a Balkans Campaign alongside Italy, which also resulted in the destruction of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1941 and the ceding of Dalmatia to Italy. Mussolini and Hitler compensated Croatian nationalists by endorsing the creation of the Independent State of Croatia under the extreme nationalist Ustaše. To receive the support of Italy, the Ustaše agreed to concede the main central portion of Dalmatia and various Adriatic Sea islands to Italy, as Dalmatia held a significant number of Italians. The Independent State of Croatia considered the ceding of the Adriatic Sea islands to be a minimal loss, as in exchange for those cessions, they were allowed to annex all of modern-day Bosnia and Herzegovina, which led to the persecution of the Serb population there. Officially, the Independent State of Croatia was a kingdom and an Italian protectorate, ruled by Italian House of Savoy member Tomislav II of Croatia, but he never personally set foot on Croatian soil and the government was run by Ante Pavelić, the leader of the Ustaše. However, Italy did hold military control across all of Croatia's coast, which, combined with Italian control of Albania and Montenegro, gave Italy complete control of the Adriatic Sea, thus completing a key part of the Mare Nostrum policy of the Fascists. The Ustaše movement proved valuable to Italy and Germany as a means to counter Royalist Chetnik guerrillas (although they did work with them because they did not like the Ustaše movement, whom they left up to the Germans) and the communist Yugoslav Partisans under Josip Broz Tito who opposed the occupation of Yugoslavia.

Under Italian army commander Mario Roatta's watch, the violence against the Slovene civil population in the Province of Ljubljana easily matched that of the Germans[111] with summary executions, hostage-taking and hostage killing, reprisals, internments to Rab and Gonars concentration camps and the burning of houses and whole villages. Roatta issued additional special instructions stating that the repression orders must be "carried out most energetically and without any false compassion".[112] According to historians James Walston[113] and Carlo Spartaco Capogeco,[114] the annual mortality rate in the Italian concentration camps was higher than the average mortality rate in Nazi concentration camp Buchenwald (which was 15%), at least 18%. On 5 August 1943, Monsignor Joze Srebnic, Bishop of Veglia (Krk island), reported to Pope Pius XII that "witnesses, who took part in the burials, state unequivocally that the number of the dead totals at least 3,500".[114] Yugoslav Partisans perpetrated their crimes against the local ethnic Italian population (Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians) during and after the war, including the foibe massacres. After the war, Yugoslavia, Greece and Ethiopia requested the extradition of 1,200 Italian war criminals for trial, but they never saw anything like the Nuremberg trials because the British government with the beginning of the Cold War saw in Pietro Badoglio a guarantee of an anti-communist post-war Italy.[115] The repression of memory led to historical revisionism in Italy about the country's actions during the war. In 1963, the anthology "Notte sul'Europa", a photograph of an internee from Rab concentration camp, was included while claiming to be a photograph of an internee from a German Nazi camp when in fact, the internee was a Slovene Janez Mihelčič, born 1885 in Babna Gorica and died at Rab in 1943.[116] In 2003, the Italian media published Silvio Berlusconi's statement that Mussolini merely "used to send people on vacation".[117]

In 1940, Italy invaded Egypt and was soon driven far back into Libya by British Commonwealth forces.[118] The German army sent a detachment to join the Italian army in Libya to save the colony from the British advance. German army units in the Afrika Korps under General Erwin Rommel were the mainstay in the campaign to push the British out of Libya and into central Egypt from 1941 to 1942. The victories in Egypt were almost entirely credited to Rommel's strategic brilliance. The Italian forces received little media attention in North Africa because of their dependence on the superior weaponry and experience of Rommel's forces. For a time in 1942, Italy, from an official standpoint, controlled large amounts of territory along the Mediterranean Sea. With the collapse of Vichy France, Italy gained control of Corsica, Nizza, Savoia and other portions of southwestern France. Italy also oversaw a military occupation over significant sections of southern France. Still, despite the official territorial achievements, the so-called "Italian Empire" was a paper tiger by 1942: it was faltering as its economy failed to adapt to the conditions of war and the Allies bombing Italian cities. Also, despite Rommel's advances in 1941 and early 1942, the campaign in Northern Africa began to collapse in late 1942. The collapse came in 1943 when German and Italian forces fled Northern Africa to Sicily.

By 1943, Italy was failing on every front; by January of the year, half of the Italian forces serving on the Eastern Front had been destroyed,[119] the African campaign had collapsed, the Balkans remained unstable and demoralised Italians wanted an end to the war.[120] King Victor Emmanuel III urged Count Ciano to overstep Mussolini to try to begin talks with the Allies.[119] In mid-1943, the Allies commenced an invasion of Sicily to knock Italy out of the war and establish a foothold in Europe. Allied troops landed in Sicily with little initial opposition from Italian forces. The situation changed as the Allies ran into German forces, who held out for some time before the Allies took over Sicily. The invasion made Mussolini dependent on the German Armed Forces (Wehrmacht) to protect his regime. The Allies steadily advanced through Italy with little opposition from demoralized Italian soldiers while facing serious opposition from German forces.

Civil war (1943–1945)

By 1943, Mussolini had lost the support of the Italian population for having led a disastrous war effort. To the world, Mussolini was viewed as a "sawdust caesar" for leading his country to war with ill-equipped and poorly trained armed forces that failed in battle. The embarrassment of Mussolini to Italy led King Victor Emmanuel III and even members of the Fascist Party to desire Mussolini's removal. The first stage of his ousting took place when the Fascist Party's Grand Council, under the direction of Dino Grandi, voted to ask Victor Emmanuel to resume his constitutional powers–in effect, a vote of no confidence in Mussolini. On 26 July 1943, Victor Emmanuel officially sacked Mussolini as Prime Minister and replaced him with Marshal Pietro Badoglio. Mussolini was immediately arrested upon his removal. When the radio brought the unexpected news, Italians assumed the war was practically over. The Fascist organizations that had for two decades pledged their loyalty to Il Duce were silent – no effort was made by any of them to protest. The new Badoglio government stripped away the final elements of the Fascist government by banning the Fascist Party. The Fascists had never controlled the army, but they did have a separately armed militia, which was merged into the army. The main Fascist organs, including the Grand Council, the Special Tribunal for the Defense of the State and the Chambers, were all disbanded. All local Fascist formations clubs and meetings were shut down. Slowly, the most outspoken Fascists were purged from office.[121]

Italy then signed an armistice in Cassibile, ending its war with the Allies. However, Mussolini's reign in Italy was not over as a German commando unit, led by Otto Skorzeny, rescued Mussolini from the mountain hotel where he was being held under arrest. Hitler instructed Mussolini to establish the Italian Social Republic, a German puppet state in the portion of northern and central Italy held by the Wehrmacht. As a result, the country descended into civil war; the new Royalist government of Victor Emmanuel III and Marshal Badoglio raised an Italian Co-belligerent Army, Navy and Air Force, which fought alongside the Allies for the rest of the war. In contrast, other Italian troops, loyal to Mussolini and his new Fascist state, continued to fight alongside the Germans in the National Republican Army. Also, a large anti-fascist Italian resistance movement fought a guerrilla war against the German and RSI forces.

The RSI armed forces were a combination of Mussolini loyalist Fascists and German armed forces, although Mussolini had little power. Hitler and the German armed forces led the campaign against the Allies. They had little interest in preserving Italy as more than a buffer zone against an Allied invasion of Germany.[122] The Badoglio government attempted to establish a non-partisan administration, and many political parties were allowed to exist again after years of being banned under Fascism. These ranged from liberal to communist parties, which all were part of the government.[123] Italians celebrated the fall of Mussolini, and as the Allies took more Italian territory, the Allies were welcomed as liberators by Italians who opposed the German occupation.

Life for Italians under German occupation was hard, especially in Rome. Rome's citizens, by 1943, had grown tired of the war. Upon Italy signing an armistice with the Allies on 8 September 1943, Rome's citizens took to the streets chanting "Viva la pace!" ("Long live the peace!), but within hours German forces raided the city and attacked anti-Fascists, royalists and Jews.[124] Roman citizens were harassed by German soldiers to provide them food and fuel, German authorities arrested opposition, and many were sent into forced labor.[125] Rome's citizens, upon being liberated, reported that during the first week of the German occupation of Rome, crimes against Italian citizens took place as German soldiers looted stores and robbed Roman citizens at gunpoint.[125] Martial law was imposed on Rome by German authorities requiring all citizens to obey a curfew forbidding people to be out on the street after 9 p.m.[125] During the winter of 1943, Rome's citizens were denied access to sufficient food, firewood and coal which was taken by German authorities to be given to German soldiers housed in occupied hotels.[125] These actions left Rome's citizens living in the harsh cold and on the verge of starvation.[126] German authorities began arresting able-bodied Roman men to be conscripted into forced labour.[127] On 4 June 1944, the German occupation of Rome ended as German forces retreated as the Allies advanced.

Mussolini was captured on 27 April 1945 by Communist Italian partisans near the Swiss border as he tried to escape Italy. On the next day, he was executed[128] for high treason as sentenced in absentia by a tribunal of the National Liberation Committee. Afterwards, the bodies of Mussolini, his mistress and about fifteen other Fascists were taken to Milan, where they were displayed to the public.[129] Days later on 2 May 1945, the German forces in Italy surrendered.