China–Philippines relations

| |

China |

Philippines |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| Chinese Embassy, Makati | Philippine Embassy, Beijing |

| Envoy | |

| Ambassador Huang Xilian | Ambassador Jaime FlorCruz |

Bilateral relations between China and the Philippines have significantly progressed in recent years, peaking during the Philippine presidencies of Gloria Macapagal Arroyo and Rodrigo Duterte. However, relations have become increasingly tense due to territorial disputes in the South China Sea, particularly since the 2012 Scarborough Shoal standoff; in 2013, the Philippine government under President Benigno Aquino III in 2013 filed an arbitration case at The Hague against China over China's expansive maritime claims. The policy of current Philippine president Bongbong Marcos aims for distancing relations between the Philippines and China in favor of the country's relationship with the United States. The current policy of the general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party aims for greater influence over the Philippines, and the region in general, while combating American influence.[1]

During Rodrigo Duterte's presidency,[2] the Philippines improved its relations and cooperation with China on various issues, developing a stronger and stable ties with the country, as well as a successful Code of conduct with China and the rest of ASEAN.[3][4][5] China is the Philippines' top trading partner.[6] However, average trust view of Filipinos towards China is negative 33.[needs update] Relations deteriorated during the presidency of Bongbong Marcos due to increasing tensions over the South China sea dispute,[7] culminating in the Philippines withdrawing from the Belt and Road initiative.[8]

Political relations

Imperial China and Precolonial Philippine States

Before Spain colonized the Philippines, Imperial China acknowledged the existence of several Precolonial Philippine kingdoms and the Chinese Emperor received embassies from Filipino Datus, Rajahs, and Sultans.[9]

Establishment of official diplomatic relations

After the Philippines became independent in 1946, it established diplomatic relations with the Nationalist government of China and continued on after it lost the mainland to the Chinese Communist Party which declared the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949 that forced the Republic of China to relocate on the island of Taiwan, formerly a Japanese colony that the ROC received in 1945. During the Cold War, the two countries were part of the anti-communist camp that view the Chinese Communists as a security threat.[10] It began considering normalizing relations with the People's Republic at the start of the 1970s and the Philippines recognized the PRC on 9 June 1975, with the signing of the Joint Communiqué by leaders of the two countries.[11]

Over the 34 years, China–Philippines relations in general have attained a smooth development, and also remarkable achievements in all areas of bilateral cooperation.[11]

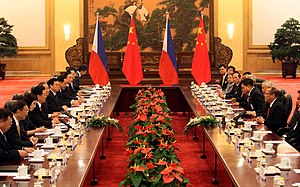

Bilateral relations between the Philippines and China have significantly progressed in recent years. The growing bilateral relations were highlighted by the state visit to China of Philippine President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo on 29–31 October 2001. During the visit, President Arroyo held bilateral talks with top Chinese leaders, namely President Jiang Zemin, NPC Chairman Li Peng, and Premier Zhu Rongji. President Arroyo also attended the 9th APEC Economic Leaders Meeting held in Shanghai on 20–21 October 2001, where she also had bilateral talks with President Jiang. During President Arroyo's visit, eight important bilateral agreements were signed.

High level visits

Since the establishment of diplomatic relations, there has been frequent exchange of high-level visits between China and the Philippines. Philippine Presidents Marcos Sr. (June 1975), Corazon Aquino (April 1988), Ramos (April 1993), Estrada (May 2000), Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo (November 2001 and September 2004), Benigno Aquino III (August–September 2011), and Duterte (October 2016, May 2017, April 2018, April 2019, and August–September 2019) have all visited China. Premier Li Peng (December 1990), Chairman of the Standing Committee of the 8th National People's Congress Mr. Qiao Shi (August 1993), President Jiang Zemin (November 1996), Premier Zhu Rongji (November 1999), Chairman of the Standing Committee of the 9th National People's Congress Mr. Li Peng (September 2002), Chairman of the Standing Committee of the 10th National People's Congress Mr. Wu Bangguo (August 2003), Paramount leader Hu Jintao (April 2005), Premier Wen Jiabao (January 2007), and Paramount leader Xi Jinping (November 2018) have all visited the Philippines as well.

Major agreements

Several major bilateral agreements were signed between the two countries over the years, such as: Joint Trade Agreement (1975); Scientific and Technological Cooperation Agreement (1978); Postal Agreement (1978); Air Services Agreement (1979); Visiting Forces Agreement (1999); Cultural Agreement (1979); Investment Promotion and Protection Agreement (1992); Agreement on Agricultural Cooperation (1999); Tax Agreement (1999); and Treaty on Mutual Judicial Assistance on Criminal Matters (2000). In May 2000, on the eve of the 25th anniversary of their diplomatic relations, the two countries signed a joint statement defining the framework of bilateral relations in the 21st century.

During President Jiang Zemin's state visit to the Philippines in 1996, leaders of the two countries agreed to establish a cooperative relationship based on good-neighborliness and mutual trust towards the 21st century, and reached important consensus and understanding of "Shelving disputes and going in for joint development" on the issue of South China Sea. In 2000, China and the Philippines signed the "Joint Statement Between China and the Philippines on the Framework of Bilateral Cooperation in the Twenty-First Century", which confirmed that the two sides will establish a long-term and stable relationship on the basis of good neighborliness, cooperation, mutual trust and benefit. During Chinese leader Hu Jintao's state visit to the Philippines in 2005, both countries are determined to establish the strategic and cooperative relations that aim at the peace and development. During Premier Wen Jiabao's official visit to the Philippines in January 2007, both sides issued a joint statement, reaffirming the commitment of taking further steps to deepen the strategic and cooperative relationship for peace and development between the two countries.

In April 2007 President Arroyo attended the annual meeting of the Boao Forum for Asia. In June 2007 she visited Chengdu and Chongqing, and in October, she attended Shanghai Special Olympics and made a side trip to Yantai, Shandong Province. In January 2008, Speaker of the Philippine House of Representatives De Venecia visited China. In August, President Arroyo attended the opening ceremony of the Beijing Olympic Games and made a side trip to Chengdu. In October Arroyo attended the Asia-Europe Summit Meeting in China and made a side trip to Wuhan and Hangzhou. Speaker of the Philippine House of Representatives Nograles went to Nanning for the 5th China-ASEAN Expo and paid a visit to Kunming and Xiamen. Vice President De Castro attended the 9th China Western International Exposition in Chengdu. In November De Castro attended the 4th World Cities Forum in Nanjing and visited Anhui and Shanghai. In December, President Arroyo went to Hong Kong to attend the Clinton Global Initiative Forum- Asia Meeting. China's Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Department of Foreign Affairs of the Philippines set up a consultation mechanism in 1991, and 15 rounds of diplomatic consultations have been held since then. Apart from reciprocal establishment of Embassies, China has a consulate general in Cebu, and established a consulate office in Laoag in April 2007. The Philippines has consulates general in Xiamen, Guangzhou, Shanghai, Chongqing, Chengdu and Hong Kong.

In July 2019, UN ambassadors of 37 countries, including Philippines, have signed a joint letter to the UNHRC defending China's treatment of Uyghurs in the Xinjiang region.[12]

Trade and commerce

Since Song dynasty times in China and precolonial times in the Philippines, evidence of trade contact can already be observed in the chinese ceramics found in archaeological sites, like in Santa Ana, Manila.[13] During Ming and Qing dynasty times in China and Spanish colonial era in the Philippines, the Philippines through Manila has had centuries-long trade contacts with cities such as Quanzhou, Zhangzhou, Xiamen in Fujian province and Guangzhou and Macau in Guangdong province, especially as part of the Maritime Silk Road trade, then connected with the Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade that ensured the export of Chinese trade goods, such as chinaware, across Spanish America and Europe in the Spanish colonial empire and the constant supply of Spanish silver into the economy of China as observed in the later dominance and widespread use of the Spanish silver dollar coins in the Ming and Qing dynasty coinage and its general acceptance as a de facto standard of trade across the Far East around the 16th to 19th century. In 1567, the Spanish trade port in the city of Manila in the Philippines as part of the Spanish colonial empire was opened which until the fall of the Ming dynasty brought over forty million Kuping Taels of silver to China with the annual Chinese imports numbering at 53,000,000 pesos (each peso being 8 real) or 300,000 Kuping Taels. During the Ming dynasty the average Chinese junk which took the voyage from the Spanish East Indies to the city of Guangzhou took with it eighty thousand pesos, a number which increased under the Qing dynasty as until the mid-18th century the volume of imported Spanish pesos had increased to 235,370,000 (or 169 460,000 Kuping Tael). The Spanish mention that around 12,000,000 pesos were shipped from Acapulco to Manila in the year 1597 as part of the Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade while in other years this usually numbered between one and four million pesos.[14]

Bilateral trade volume in 2007 was US$30.62 billion. From January to October 2008, bilateral trade volume reached US$25.3 billion, an increase of 1.4% as compared with the same period last year. By the end of September 2008, the actually utilized value of accumulative investment from the Philippines to China reached US$2.5 billion. China's transformation into a major economic power in the 21st century has led to an increase of foreign investments in the bamboo network, a network of overseas Chinese businesses operating in the markets of Southeast Asia that share common family and cultural ties.[15][16]

In 1999, China's Ministry of Agriculture and the Department of Agriculture of the Philippines signed the Agreement on Strengthening Cooperation in Agriculture and Related Fields. In 2000, relevant government agencies signed an agreement whereby China offers the Philippines US$100 million credit facility. In March 2003, China's aid project the China-Philippines Agricultural Technology Center was completed. With its successful trial planting in the Philippines, China's hybrid rice and corn have been growing over large areas in the country. In 2004, both sides signed the Memorandum of Understanding on Fisheries Cooperation. In January 2007, Chinese and Philippine Ministries of Agriculture signed Memorandum of Understanding on Broadening and Deepening Agriculture and Fisheries Cooperation.

In August 2003, the two countries signed the Memorandum of Understanding on Cooperation in Constructing the Northern Luzon Railway Project. In April 2005, the two countries signed the Memorandum of Understanding on Cooperation in the field of Infrastructure between the Ministry of Commerce of the People's Republic of China and the Department of Trade and Industry of the Republic of the Philippines.

Military relations

In April 2002, Philippine Secretary of Defense Reyes visited to China. In June, Philippine naval fleets visited China for the first time. In September, Chinese Vice Chairman of the Central Military Commission, State Councilor and Defense Minister Chi Haotian visited the Philippines. In 2004, Narciso Abaya, Chief of the General Staff of Philippine Armed Forces (AFP) and Secretary of Defense Avelino Cruz paid visits to China respectively, and both sides established the mechanism of annual Defense and Security Consultation. In May 2005, Xiong Guangkai, Deputy Chief of the General Staff of the Chinese People's Liberation Army (PLA) visited the Philippines and held the first Defense and Security Consultation with Philippine Defense Undersecretary Antonio Santos. In May 2006, Chief of the General Staff of AFP Gen. Denga visited China. In October, Philippine vice Secretary of Defense Santos visited China and both sides held the second round of Defense and Security Consultation. Also in October, North China Sea Fleet visited the Philippines, conducting a joint non-traditional security exercises. In May 2007, Zhang Qinsheng, Deputy Chief of the General Staff of PLA visited the Philippines and both sides held the Defense and Security Consultation for the third time. Chinese Vice Chairman of the Central Military Commission, State Councilor and Defense Minister Cao Gangchuan, paid a visit to the Philippines in September.

In 2023 Chinese Coast guard fired on Philippines military ships in Philippines waters.[17]

Bilateral agreements

The cooperation in the fields of culture, technology, judiciary, and tourism between the two countries achieves continuous progress. So far, the two sides have signed 11 two-year action plans of cultural cooperation. The joint committee of scientific and technological cooperation has held 13 sessions, during which 244 research projects have been confirmed.

The major bilateral agreements between the two countries are as follows: Scientific and Technological Cooperation Agreement (1978), Cultural Cooperation Agreement (1979), Civil Aviation and Transportation Agreement (1979), Memorandum of Understanding on Sports Cooperation (2001), Memorandum of Understanding on Cooperation in Information Industry (2001), Memorandum of Understanding on Cooperation in the Crackdown on Transnational Crimes (2001), Treaty on Extradition (2001), Pact on Cooperation Against Illicit Traffic and Abuse of Narcotic Drugs (2001), Memorandum of Understanding on Tourism Cooperation (2002), Memorandum of Understanding on Maritime Cooperation (2005), Pact on Cooperation in Youth Affairs (2005), Memorandum of Understanding on Cooperation in Sanitary and Phytosanitary Cooperation (2007), Memorandum of Understanding on Education Cooperation (2007), Pact on Protection of Cultural Heritage (2007), Pact on Sanitary Cooperation (2008), etc.

Official Development Assistance (ODA)

During the respective visits of Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte to the People's Republic of China and the Chinese Communist Party general secretary Xi Jinping's visit to the Philippines, the two agreed to a significant increase of Official Development Assistance (ODA) from the People's Republic of China as part of Xi's Belt and Road Initiative.[18] However, concerns were soon raised over the terms and conditions of the ODA funding and the lack of transparency over the details of the details.[19] As of 2018, the delivery of that aid had also stalled, with few firm commitments put in place by the Xi administration.[18][19] Despite this, the Duterte administration continued to make the relationship a major part of its economic agenda.[19]

Others

Chinese Filipinos constitute one group of overseas Chinese and are one of the largest overseas Chinese communities in Southeast Asia. As of 2005[update], Chinese Filipinos number approximately 1.5 million corresponding to 1.6% of the Philippine population. Chinese Filipinos are well represented in all levels of Philippine society, and well integrated politically and economically.[citation needed] The ethnically Chinese Filipinos comprise 1.6% (1.5 million) of the population or ~15-27% of the population including all variants of Chinese mestizos. Pure Chinese Filipinos comprise the 9th largest, and the largest non-indigenous ethnic group in the Philippines.[citation needed]

Chinese Filipinos are present within several commerce and business sectors in the Philippines and a few sources estimate companies which comprise a majority of the Philippine economy are owned by Chinese Filipinos, if one includes Chinese mestizos.[20][21][22][23]

In view of the ongoing territorial dispute of China and the Philippines (such as Scarborough Shoal), Chinese-Filipinos prefer a peaceful solution through diplomatic talks while some view that China should not extend its claims to other parts of South China Sea.[24]

There are 24 pairs of sister-cities or sister-provinces between China and the Philippines, namely: Hangzhou and Baguio, Guangzhou and Manila, Shanghai and Metro Manila, Xiamen and Cebu City, Shenyang and Quezon City, Fushun and Lipa, Hainan and Cebu province, Sanya and Lapu-Lapu, Shishi and Naga, Camarines Sur, Shandong and Ilocos Norte, Zibo and Mandaue, Anhui and Cavite, Hubei and Leyte, Liuzhou and Muntinlupa, Hezhou and San Fernando,[which?] Harbin and Cagayan de Oro, Laibin and Laoag, Beijing and Manila, Jiangxi and Bohol, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region and Davao City, Lanzhou and Albay, Beihai and Puerto Princesa, Fujian and Laguna, Wuxi and Puerto Princesa.

The Chinese official Xinhua News Agency has its branch in Manila while CCTV-4, the Chinese international TV program, has landed in the Philippines.

According to a 2023 report by the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism, tycoon George Siy's think tank, the Integrated Development Studies Institute, has been a major promoter of pro-Chinese government narratives in the Philippines.[25]

-

Noble Prince and Princess from Ming Dynasty China

-

Ming Dynasty Chinese general with attendant

-

Hakka Chinese Fisherman with Wife

Territorial disputes

Spratly Islands and the South China Sea

The two countries have disputes over the sovereignty of some islands and shoals in the Spratly Islands.[26] After rounds of consultations, both sides agreed to strive for a solution through bilateral friendly consultation. In October 2004, Chinese Maritime Safety Administration and Philippine Coast Guard conducted a joint sand table rescue exercise for the first time. China National Offshore Oil Corp. and Philippine National Oil Company signed the "Agreement for Joint Marine Seismic Undertaking on Certain Areas in the South China Sea" on 1 September 2004. In May 2005, Vietnam agreed to join the Sino-Philippine cooperation. Oil companies from three countries signed the "Agreement for Joint Marine Seismic Undertaking on Certain Areas in the South China Sea" in March 2005.

Due to the 2012 Scarborough Shoal standoff, relations between the two countries have soured greatly after China pursued to grab the Scarborough Shoal, which has been in Philippine possession until the standoff. After a few weeks, a storm passed by the area and the international community of nations urged both nations to ease tensions by withdrawing from the site. Both nations agreed to withdraw, however, when the Philippines withdrew, China immediately sent warships to counter any arrival from the Philippine side. The blatant defiance to the truce met international outcry towards China. China afterwards began establishing structures on the shoal. An American footage showed after a few months that the shoal may possess Chinese ballistic missiles.[27] A 2014 survey conducted by the Pew Research Center showed 93% of Filipinos were concerned that territorial disputes between China and neighboring countries could lead to a military conflict.[28][needs update]

In April 2019, international satellites and local reports revealed that Chinese ships have swarmed Philippine-controlled areas in the South China Sea through a cabbage strategy.[29][30][31] Later reports showed that endangered giant clams under Philippine law protection were illegally being harvested by Chinese ships.[32][33] The swarming continued for the entirety of April, with the Philippine foreign affairs secretary, Teddy Locsin Jr., expressing dismay over the incident and calling it an intentional "embarrassment" aimed against the Philippines.[34] A few days before the 2019 Philippine independence day, President Duterte stated that the country may go to war with China if China claims disputed resources.[35]

2019 Reed Bank incident

On 9 June, a Chinese ship, Yuemaobinyu 42212, rammed and sank a Philippine fishing vessel, F/B Gem-Ver, near Reed Bank, west of Palawan. The fishermen were caught by surprise as they were asleep during the said event. The Chinese ship afterwards left the sank Philippine vessel, while the Filipino fishermen were adrift in the middle of sea and left to the elements, in violation of a rule under UNCLOS.[35][36] The 22 Filipino fishermen were later rescued by a ship from Vietnam.[37][38]

The government responded a day later, stating that they may cut ties with China if the culprits are not punished by the Chinese.[39][40] China has stated that the event was an ordinary maritime accident,[41] which was later backed up by investigations from the Armed Forces of the Philippines.[42]

The Chinese crew was later criticized for failing to undertake measures to avoid colliding with the F/B Gem-Ver and abandoning the stricken boat's crew, in violation of maritime laws.[43][44]

Benham Rise

In March 2017, Chinese ships were spotted in the Benham Rise, a protected food supply exclusive zone of the Philippines. The Philippines, through its ambassador to Beijing has officially asked China to explain the reported presence of one of its vessels in Benham Rise in the Pacific.[45][46] A week later, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs released a statement saying that China is honoring the Philippines' sovereign rights over Benham Rise, and that the ship was passing by. However, the ship was revealed to have been on the area for about three months.[47] In May 2017, Philippine president Duterte revealed that the Chinese Communist Party leader Xi Jinping made an unveiled threat of war against the Philippines over the islands in the South China Sea during a meeting in Beijing.[48]

In January 2018, the Department of Foreign Affairs approved the Chinese Institute of Oceanology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences to perform a scientific survey of the Rise, with the approval of President Rodrigo Duterte.[49] In February, Duterte ordered the halting of all foreign researches in the Philippines Rise, however, the research being conducted by the Chinese Academy of Sciences was already finished before the halt order.[50]

The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) and the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC) of the UNESCO have rules wherein the entity that first discovers unnamed features underwater have the right to name those features, prompting Filipino officials to realize that China was after, not just research, but also the naming rights over the underwater features of the Philippine Rise which will be internationally recognized through UNESCO.[51] It was later clarified by the Philippine government that all researches ongoing at the time the halting was made were officially cancelled, but the government still allows research activities in the Rise. Foreign researchers may still do research within the Rise if they apply for research activities through the Philippine government.[52] The government is also maintaining that the Rise belongs to the Philippines.[53] On 12 February 2018, the International Hydrographic Organization approved the names proposed by China for five features in the Philippine Rise after China submitted to the organization its research findings on the area. The Chinese naming of the features met public protests in the Philippines.[54][55]

2016 UNCLOS-PCA ruling on Spratly

In January 2013, the Philippines formally initiated arbitration proceedings against China's claim on the territories within the "nine-dash line" that includes Spratly Islands, which it said is "unlawful" under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).[56][57] An arbitration tribunal was constituted under Annex VII of UNCLOS and it was decided in July 2013 that the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) would function as registry and provide administrative duties in the proceedings.[58]

On 12 July 2016, the arbitrators of the tribunal of PCA agreed unanimously with the Philippines. They concluded in the award that there was no evidence that China had historically exercised exclusive control over the waters or resources, hence there was "no legal basis for China to claim historic rights" over the nine-dash line.[59] Accordingly, the PCA tribunal decision is ruled as final and non-appealable by either countries.[60][61] The tribunal also criticized China's land reclamation projects and its construction of artificial islands in the Spratly Islands, saying that it had caused "severe harm to the coral reef environment".[62] It also characterized Taiping Island and other features of the Spratly Islands as "rocks" under UNCLOS, and therefore are not entitled to a 200 nautical mile exclusive economic zone.[63] China however rejected the ruling, calling it "ill-founded".[64] Taiwan, which currently administers Taiping Island, the largest of the Spratly Islands, also rejected the ruling.[65]

On 26 June 2020, the statement of the 36th ASEAN Summit was released. The statement said the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea is "the basis for determining maritime entitlements, sovereign rights, jurisdiction and legitimate interests over maritime zones, and the 1982 UNCLOS sets out the legal framework within which all activities in the oceans and seas must be carried out."[66]

Other disputes

The Philippines has accused China of parking its navy and coast guard vessels near some artificial island. As a result, Philippine vessels cannot pass through this area. The Philippines called this a floating barrier.[67]

See also

China

Philippines

References

- ^ "Philippines' Duterte in China announces split with US". Aljazeera.com. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- ^ "Subscribe | theaustralian". www.theaustralian.com.au.

- ^ "China, ASEAN agree on framework for South China Sea code of conduct". Reuters. 2017.

- ^ "China, Philippines confirm twice-yearly bilateral consultation mechanism on South China Sea - Xinhua | English.news.cn". news.xinhuanet.com. Archived from the original on 19 May 2017.

- ^ "Progress made on draft of South China Sea code of conduct". The Philippine Star.

- ^ "PH trade deficit narrows in May; China is top trade partner". ABS-CBN News. 11 July 2023. Archived from the original on 11 July 2023. Retrieved 25 September 2023.

- ^ "Philippines, China trade blame for collision in disputed waters". France24. 10 December 2023.

Relations between Manila and Beijing have deteriorated under President Ferdinand Marcos, who has sought to improve ties with traditional ally Washington and push back against Chinese actions in the South China Sea.

- ^ "After Italy, Philippines to exit China's Belt and Road Initiative". Times Now News. 4 November 2023.

- ^ Scott, William Henry (1989). "Filipinos in China in 1500" (PDF). China Studies Program. De la Salle University. p. 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- ^ Zhao, Hong (2012). "Sino-Philippines Relations: Moving beyond South China Sea Dispute?". Journal of East Asian Affairs: 57. ISSN 1010-1608. Archived from the original on 24 September 2018.

- ^ a b Banlaoi, Rommel C. (2007). Security Aspects of Philippines-China Relations: Bilateral Issues and Concerns in the Age of Global Terrorism. Rex Bookstore, Inc. p. 53-55. ISBN 978-971-23-4929-4. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ "Which Countries Are For or Against China's Xinjiang Policies?". The Diplomat. 15 July 2019.

- ^ "Pre-colonial Manila". Malacañan Palace: Presidential Museum And Library. Archived from the original on 24 July 2015. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ ChinaKnowledge.de – An Encyclopaedia on Chinese History, Literature and Art "Qing Period Money". Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ^ Quinlan, Joe (13 November 2007). "Insight: China's capital targets Asia's bamboo network". Financial Times.

- ^ Murray L Weidenbaum (1 January 1996). The Bamboo Network: How Expatriate Chinese Entrepreneurs are Creating a New Economic Superpower in Asia. Martin Kessler Books, Free Press. pp. 4–8. ISBN 978-0-684-82289-1.

- ^ "Philippines accuses China of water cannon attack in Spratly Islands". The Guardian. 6 August 2023. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 8 August 2023.

- ^ a b "Japan, China battle for ODA influence in the Philippines". 20 November 2018.

- ^ a b c "The meager truth of China's aid to the Philippines". Asia Times. 5 December 2018.

- ^ Amy Chua, "World on Fire", 2003, Doubleday, pp. 3 & 43.

- ^ "Is Democracy Dangerous?". BusinessWeek. 30 December 2002. Archived from the original on 8 January 2003. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ^ "The ethnic Chinese variable in domestic and foreign policies in Malaysia and Indonesia" (PDF). Summit.sfu.ca. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^ Chirot, Daniel; Reid, Anthony (October 2011). Essential Outsiders: Chinese and Jews in the Modern Transformation of Southeast Asia and Central Europe. University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295800264. Retrieved 6 May 2012 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Scarborough in the eyes of Filipino-Chinese". Rappler. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- ^ Elemia, Camille (23 October 2023). "Philippines confronts unlikely adversary in SCS row: Filipinos echoing 'pro-Beijing' narratives". Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism. Retrieved 29 October 2023.

- ^ "Lawless Ocean: The Link Between Human Rights Abuses and Overfishing". Yale E360. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- ^ Zirulnick, Ariel. "Philippines feels the economic cost of standing up to China". The Christian Science Monitor, 15 May 2012.

- ^ "Chapter 4: How Asians View Each Other". Pew Research Center. 14 July 2014. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ^ "China's swarming: 'Cabbage strategy'". The Philippine Star. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ "In swarming Pagasa, China aims to control Sandy Cay". The Philippine Star. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ "Philippines hits out at China's 'swarming' South China Sea ships". Nikkei Asian Review. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ News, Chiara Zambrano, ABS-CBN. "EXCLUSIVE: Chinese harvesting giant clams in Scarborough Shoal". ABS-CBN News.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ News, Arianne Merez, ABS-CBN. "China's harvest of giant clams an 'affront' to Philippines: Palace". ABS-CBN News.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "China 'continually embarrasses' PH by swarming West Philippine Sea - DFA chief". CNN Philippines.

- ^ a b "Rodrigo Duterte threatens war with Beijing over South China Sea resources". South China Morning Post. 29 May 2018.

- ^ II, Paterno Esmaquel. "Hold China accountable, Del Rosario says after sinking of PH boat". Rappler.

- ^ Maru, Davinci. "How the Vietnamese rescued Pinoy fishermen rammed by Chinese vessel". ABS-CBN News.

- ^ Gutierrez, Jason; Beech, Hannah (13 June 2019). "Sinking of Philippine Boat Puts South China Sea Back at Issue". The New York Times.

- ^ Ranada, Pia. "Panelo says possible for PH to cut ties with China over boat sinking". Rappler.

- ^ "Philippines asks China to sanction ship crew in 'hit-and-run'". ABS-CBN News.

- ^ "China calls sinking of Philippine boat an 'ordinary maritime accident'". Rappler. Agence France-Presse.

- ^ News, Arianne Merez, ABS-CBN. "Military cites report: Chinese ship 'accidentally collided' with Filipino fishing boat". ABS-CBN News.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Senators denounce 'acts of inhumanity' by Chinese crew". Philippine News Agency.

- ^ "Abandonment of Pinoy fishermen in sea 'collision' violates UNCLOS: Panelo | ANC" – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ "Phl to China: Explain ship in Benham Rise". The Philippine Star. Archived from the original on 13 March 2017. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- ^ "PH, China exchange statements over ships spotted in Benham Rise". CNN Philippines. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- ^ "China: We respect Philippines' rights over Benham Rise". CNN Philippines. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- ^ "Duterte says China's Xi threatened war if Philippines drills for oil". Reuters. 19 May 2017 – via www.reuters.com.

- ^ Amurao, George (18 January 2018). "China eyes Philippines' strategic eastern shores". Asia Times.

- ^ "Duterte orders no more foreign explorations in Benham Rise —Piñol". GMA News.

- ^ "China seeks to name sea features in Philippine Rise". The Philippine Star.

- ^ Gita, Ruth Abbey (6 February 2018). "Palace clarifies: Foreign research may be allowed in Philippine Rise". SunStar.

- ^ Gita, Ruth Abbey (10 February 2018). "Philippine Rise belongs to the Philippines, Duterte insists". SunStar.

- ^ "China named 5 undersea features at PH Rise, says expert". ABS-CBN News.

- ^ Mangosing, Frances. "China named 5 undersea features at PH Rise – expert". Philippine Daily Inquirer.

- ^ "Timeline: South China Sea dispute". Financial Times. 12 July 2016.

- ^ Beech, Hannah (11 July 2016). "China's Global Reputation Hinges on Upcoming South China Sea Court Decision". Time.

- ^ "Press Release: Arbitration between the Republic of the Philippines and the People's Republic of China: Arbitral Tribunal Establishes Rules of Procedure and Initial Timetable". PCA. 27 August 2013. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ "Press Release: The South China Sea Arbitration (The Republic of the Philippines v. The People's Republic of China)" (PDF). PCA. 12 July 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 July 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ "A UN-appointed tribunal dismisses China's claims in the South China Sea". The Economist. 12 July 2016.

- ^ Perez, Jane (12 July 2016). "Beijing's South China Sea Claims Rejected by Hague Tribunal". The New York Times.

- ^ Tom Phillips; Oliver Holmes; Owen Bowcott (12 July 2016). "Beijing rejects tribunal's ruling in South China Sea case". The Guardian.

- ^ Chow, Jermyn (12 July 2016). "Taiwan rejects South China Sea ruling, says will deploy another navy vessel to Taiping". The Straits Times.

- ^ "South China Sea: Tribunal backs case against China brought by Philippines". BBC. 12 July 2016.

- ^ Jun Mai; Shi Jiangtao (12 July 2016). "Taiwan-controlled Taiping Island is a rock, says international court in South China Sea ruling". South China Morning Post.

- ^ B Pitlo III, Lucio (3 July 2020). "ASEAN stops pulling punches over South China Sea". Asia Times. Archived from the original on 17 August 2020. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- ^ "China accused of erecting new barrier near disputed South China Sea shoal". ABC News. 24 September 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

External links

Media related to Relations of China and the Philippines at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Relations of China and the Philippines at Wikimedia Commons- Chinese Embassy in Manila

- Philippine Embassy in Beijing