Bristol

Bristol

County and City of Bristol[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Motto(s): "Virtute et Industria" "By Virtue and Industry" | |

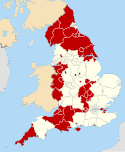

Location of the county of Bristol in England | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | England |

| Region | South West |

| Royal Charter | 1155 |

| County status | 1373 |

| Status | City, county and unitary authority |

| Government | |

| • Type | Unitary authority |

| • Governing body | Bristol City Council |

| • Admin HQ | City Hall, College Green |

| • Leadership | Mayor and Cabinet |

| • Mayor | George Ferguson |

| • MPs | Chris Skidmore (C) Kerry McCarthy (L)

|

| Area | |

| • City and county | 40 sq mi (110 km2) |

| Elevation | 36 ft (11 m) |

| Population (2012) | |

| • City and county | 432,500 (Ranked 10th district and 43rd ceremonial county) |

| • Density | 10,080/sq mi (3,892/km2) |

| • Urban | 617,000 (2,011 ONS estimate[3]) |

| • Metro | 1,006,600 (LUZ 2,009) |

| • Ethnicity[4] | 84.0% White (77.9% White British) 6.0% Black 5.5% Asian 3.6% Mixed Race 0.3% Arab 0.6% Other |

| Time zone | GMT (UTC) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (BST) |

| Postcode | |

| Area code(s) | 0117, 01275 |

| ISO 3166 code | GB-BST |

| GVA | 2012 |

| • Total | £11.7bn ($19.4bn) (8th) |

| • Growth | |

| • Per capita | £27,100 ($44,900) (5th) |

| • Growth | |

| GDP | US$ 47.7 billion [5] |

| GDP per capita | US$ 42,326[5] |

| Website | www.bristol.gov.uk |

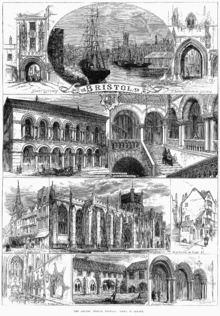

Bristol (/ˈbrɪstəl/ ) is a city, unitary authority and county in South West England with an estimated population of 437,500 in 2014.[6] It is England's sixth and the United Kingdom's eighth most populous city,[7] and the most populous city in Southern England outside London.

Bristol received a Royal charter in 1155. It was part of Gloucestershire until 1373 when it became a county in its own right.[8] From the 13th to the 18th century, it ranked among the top three English cities after London, along with York and Norwich, on the basis of tax receipts,[9] until the rapid rise of Manchester, Liverpool and Birmingham in the Industrial Revolution. It borders the counties of Somerset and Gloucestershire, with the historic cities of Bath and Gloucester to the south east and the north respectively. The city is built around the River Avon and also has a short coastline on the Severn Estuary which flows into the Bristol Channel.

Bristol's prosperity has been linked with the sea since its earliest days. The Port of Bristol was originally in the city centre before being moved to the Severn Estuary at Avonmouth; Royal Portbury Dock is on the western edge of the city. In recent years, the economy has depended on the creative media, electronics and aerospace industries and the city centre docks have been regenerated as a centre of heritage and culture.[10] People from Bristol are termed Bristolians.[11]

History

Archaeological finds, including flints tools created by the Levallois technique, believed to be 60,000 years old, have shown the presence of Neanderthals in the Shirehampton and St Annes areas of Bristol in the Middle Palaeolithic period.[13][14] Iron Age hill forts near the city are at Leigh Woods and Clifton Down on the side of the Avon Gorge, and on Kings Weston Hill, near Henbury.[15] During the Roman era there was a settlement, Abona,[16] at what is now Sea Mills, connected to Bath by a Roman road, and another at the present-day Inns Court. There were also isolated Roman villas and small Roman forts and settlements throughout the area.[17]

The town of Brycgstow (Old English, "the place at the bridge")[18] appears to have been founded by 1000 and by c.1020 was an important enough trading centre to possess its own mint, producing silver pennies bearing the town's name.[19] By 1067 the town was clearly a well-fortified burh that proved capable of resisting an invasion force sent from Ireland by Harold's sons.[19] Under Norman rule the town acquired one of the strongest castles in southern England.[20]

The area around the original junction of the River Frome with the River Avon, adjacent to the original Bristol Bridge and just outside the town walls, was where the port began to develop in the 11th century.[21] By the 12th century Bristol was an important port, handling much of England's trade with Ireland, including slaves. In 1247 a new stone bridge was built, which was replaced by the current Bristol Bridge in the 1760s,[22] and the town was extended to incorporate neighbouring suburbs, becoming in 1373 a county in its own right.[23][24] During this period Bristol also became a centre of shipbuilding and manufacturing.[25] By the 14th century Bristol was one of England's three largest medieval towns after London, along with York and Norwich. Between a third and half of the population were lost during the Black Death of 1348–49.[26] This had the effect of causing a slowing in the growth of the population, meaning that the number of residents stayed between 10,000 and 12,000 for most of the 15th and 16th centuries.[27]

In the 15th century, Bristol was the second most important port in the country, trading with Ireland,[28] Iceland,[29] and Gascony.[25] Bristol was the starting point for many important voyages, including that led by Robert Sturmy (1457–58) to try to break the Italian monopoly over trade with the Eastern Mediterranean.[30] After Sturmy's unsuccessful expedition, Bristol merchants turned west, launching expeditions into the Atlantic, in search of the phantom island of Hy-Brazil, by at least 1480. These Atlantic voyages were to culminate in John Cabot's 1497 voyage of exploration to North America and the subsequent expeditions undertaken by Bristol merchants to the new world up to 1508.[31][32] Another notable voyage during this period, led by William Weston of Bristol in 1499, was the first English-led expedition to North America.[33] In the sixteenth century, however, Bristol merchants concentrated on developing their trade with Spain and its American colonies.[34] This included the smuggling of 'prohibited' wares, such as foodstuffs and guns, to Iberia,[35] even during the Anglo-Spanish war of 1585–1604.[36] Indeed, the scale of the city's illicit trade grew enormously after 1558, to become an essential component of the city's economy.[37]

The Diocese of Bristol was founded in 1542,[38] with the former Abbey of St. Augustine, founded by Robert Fitzharding in 1140,[39] becoming Bristol Cathedral. Traditionally this is equivalent to the town being granted city status, which was granted to Bristol in that year. It was formally granted the status of county in 1542.[40] During the 1640s English Civil War the city was occupied by Royalist military, who built the Royal Fort House on the site of an earlier Parliamentarian stronghold.[41]

Renewed growth came with the 17th century rise of England's American colonies and the rapid 18th-century expansion of England's role in the Atlantic trade of Africans taken for slavery in the Americas. Bristol, along with Liverpool, became a centre for the Triangular trade. In the first stage of slavery triangle, manufactured goods were taken to West Africa and exchanged for Africans who were then, in the second stage or middle passage, transported across the Atlantic in brutal conditions.[42] The third leg of the triangle brought plantation goods such as sugar, tobacco, rum, rice and cotton back across the Atlantic,[42] along with small number of slaves, who were sold to the aristocracy as house servants. Some of the household slaves eventually bought their freedom.[43] During the height of the slave trade, from 1700 to 1807, more than 2,000 slaving ships were fitted out at Bristol, carrying a (conservatively) estimated half million people from Africa to the Americas and slavery.[44]

The Seven Stars public house,[45] where abolitionist Thomas Clarkson collected information on the slave trade, still exists.

Fishermen from Bristol had fished the Grand Banks of Newfoundland since the 15th century[46] and began settling Newfoundland permanently in larger numbers in the 17th century, establishing colonies at Bristol's Hope and Cuper's Cove. Bristol's strong nautical ties meant that maritime safety was an important issue in the city. During the 19th century Samuel Plimsoll, "the sailor's friend", campaigned to make the seas safer; he was shocked by the overloaded cargoes, and successfully fought for a compulsory load line on ships.[47]

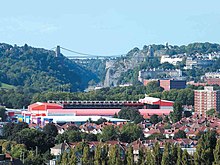

Competition from Liverpool from c. 1760, the disruption of maritime commerce caused by wars with France (1793) and the abolition of the slave trade (1807) contributed to the city's failure to keep pace with the newer manufacturing centres of the North of England and the West Midlands. The passage up the heavily tidal Avon Gorge, which had made the port highly secure during the Middle Ages, had become a liability. A scheme to improve the city's port with construction of a new "Floating Harbour" (designed by William Jessop) in 1804–9 proved a costly error, resulting in excessive harbour dues.[48] Nevertheless, Bristol's population (66,000 in 1801) quintupled during the 19th century, supported by new industries and growing commerce.[49] It was particularly associated with the noted Victorian engineer, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, who designed the Great Western Railway between Bristol and London Paddington, two pioneering Bristol-built oceangoing steamships, the SS Great Britain and SS Great Western, and the Clifton Suspension Bridge. John Wesley founded the very first Methodist Chapel, called the New Room, in Bristol in 1739. Riots occurred in 1793[50] and 1831, the first beginning as a protest at renewal of an act levying tolls on Bristol Bridge, and the latter after the rejection of the second Reform Bill.[51]

By 1901, some 330,000 people were living in Bristol and the city would grow steadily as the 20th century progressed. The city's docklands were enhanced in the early 1900s with the opening of Royal Edward Dock.[52] Another new dock – Royal Portbury Dock – was opened in the 1970s.[53] With the advent of air travel, aircraft manufacturers set up base at new factories in the city during the first half of the 20th century.[54]

Its education system received a major boost in 1909 with the formation of the University of Bristol,[55] though it really took off in 1925 when its main building was opened.[56] A polytechnic was opened in 1969 to give the city a second higher education institute, which would become the University of the West of England in 1992.[57]

Bristol suffered badly from Luftwaffe air raids in World War II, claiming some 1,300 lives of people living and working in the city, with nearly 100,000 buildings being damaged, at least 3,000 of them beyond repair.[58][59] The original central shopping area, near the bridge and castle, is now a park containing two bombed out churches and some fragments of the castle. A third bomb-damaged church nearby, St Nicholas, has been restored and has been made into a museum. It houses a triptych by William Hogarth, painted for the high altar of St Mary Redcliffe in 1756. The museum also contains statues moved from Arno's Court Triumphal Arch, of King Edward I and King Edward III, taken from Lawfords' Gate of the city walls when they were demolished around 1760, and 13th century figures from Bristol's Newgate representing Robert, the builder of Bristol Castle, and Geoffrey de Montbray, Bishop of Coutances, builder of the fortified walls of the city.[60]

The rebuilding of Bristol city centre was characterised by 1960s and 1970s skyscrapers, mid-century modern architecture, and the improvement of road infrastructure. Since the 1980s another trend has emerged with the closure of some main roads, the restoration of the Georgian era Queen Square and Portland Square, the regeneration of the Broadmead shopping area, and the loss of one of the city centre's tallest mid-century modern towers.[61]

Bristol's road infrastructure was altered dramatically in the 1960s and 1970s with the development of the M4 and M5 motorways, which meet at an interchange just north of the city. The motorways link the city with London (M4 eastbound), Swansea (M4 westbound across the Estuary of the River Severn), Exeter (M5 southbound) and Birmingham (M5 northbound).

The relocation of the docks to Avonmouth Docks and Royal Portbury Dock, 7 miles (11 km) downstream from the city centre during the 20th century has also allowed redevelopment of the old central dock area (the "Floating Harbour") in recent decades. At one time the continued existence of the docks was in jeopardy, because the area was viewed as a derelict industrial site rather than an asset. However, the first International Festival of the Sea, held in and around the docks in 1996, affirmed the dockside area in its new leisure role as a key feature of the city.[62]

On the sporting scene, Bristol Rugby union club has frequently competed at the highest level in the sport since its formation in 1888.[63] The club used to play at the Memorial Ground, which it shared with Bristol Rovers Football Club since 1996. Although the rugby club was landlord when the football club arrived at the stadium as tenants, a decline in the rugby club's fortunes shortly afterwards led to the football club becoming landlord and the rugby club becoming the stadium's tenant. Bristol Rovers had spent the previous 10 years playing their home games outside the city following the closure of their Eastville stadium in 1986, before returning to the city to play at the Memorial Ground.[64]

In 2014, Bristol Rugby club moved to their new home Ashton Gate stadium, home to Bristol Rovers rivals Bristol City, for the 2014/15 campaign.

Bristol Rovers have generally been overshadowed by their local rival, Bristol City, in terms of footballing success. Unlike Rovers, City has enjoyed top-flight football. The club's first spell in the Football League First Division began in 1906, and ended its first season in fine form among the elite by finishing second, only narrowly missing out on league title glory. Two years later, City was on the losing side in the final of the FA Cup, and relegated back to the Football League Second Division two years later. It would be another 65 years before First Division status was regained, in 1976. This time they spent four years among the elite before being relegated in 1980 – the first of a then unique three successive relegations, dropping the club into the Fourth Division in 1982. Although promotion was secured in 1984, City enjoyed a seventh spell in the league's third tier until 2007 when it was promoted to the second tier, narrowly missing out on top-flight promotion in the first season (Playoff final defeat against Hull City) English football. However the club regained League One in 2013. Since 1900 City's home games have been played at Ashton Gate,[65] although in recent years a number of schemes have been mooted to relocate the club to a new, larger stadium.[66]

Government

Bristol City Council consists of 70 councillors representing 35 wards. They are elected in thirds with two councillors per ward, each serving a four-year term. Wards never have both councillors up for election at the same time, so effectively two-thirds of the wards are up each election.[67] The Council has long been dominated by the Labour Party, but recently the Liberal Democrats have grown strong in the city and, as the largest party, took minority control of the Council at the 2005 election. In 2007, Labour and the Conservatives joined forces to vote down the Liberal Democrat administration, and as a result, Labour ruled the council under a minority administration, with Helen Holland as the council leader.[68] In February 2009, the Labour group resigned, and the Liberal Democrats took office with their own minority administration.[69] At the council elections on 4 June 2009 the Liberal Democrats gained four seats and, for the first time, overall control of the City Council.[70] The most recent City council elections were in May 2014.

On 3 May 2012, Bristol held a referendum to decide whether the city should have a directly elected mayor to replace the leader elected by councillors. The result, announced the following day, were 41,032 votes for an elected mayor and 35,880 votes against, with a turnout of 24 percent. An election for the new post was held on 15 November 2012 with Independent candidate George Ferguson becoming Mayor of Bristol.[71]

The Lord Mayor of Bristol, not to be confused with the Mayor of Bristol, is ceremonial figurehead, elected each May by city councillors. Councillor Faruk Choudhury was selected by his fellow councillors for this position in 2013. At age 38, he was the youngest person to serve as Lord Mayor of Bristol, and also the first Muslim elected to the office.[72]

Bristol constituencies in the House of Commons cross the borders with neighbouring authorities, and the city is divided into Bristol West, East, South and North-west. In the May 2010 General Election, the boundaries were changed to coincide with the county boundary. Following the 2010 election there were two Labour members of parliament (MPs), one Liberal Democrat and one Conservative.[73] After the 2010 British General election, the new political representation of the city was composed of two Labour MPs, and one MP each for the Liberal Democrats and the Conservatives. The Conservatives gained Bristol North-West from the Labour Party.[74]

Bristol has a tradition of local political activism, and has been home to many important political figures. Edmund Burke, MP for the Bristol constituency for six years from 1774, famously insisted that he was a member of parliament first, rather than a representative of his constituents' interests.[75][76] The women's rights campaigner Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence (1867–1954) was born in Bristol.[77] Tony Benn, a veteran left-wing politician, was MP for Bristol South East from 1950 to 1960 and again from 1963 until 1983.[78] In 1963, there was a boycott of the city's buses after the Bristol Omnibus Company refused to employ black drivers and conductors. The boycott is known to have influenced the creation of the UK's Race Relations Act in 1965.[79] The city was the scene of the first of the 1980s riots. In St. Paul's, a number of largely Afro-Caribbean people rose up against racism, police harassment and mounting dissatisfaction with their social and economic circumstances before similar disturbances followed across the UK. Local support of fair trade issues was recognised in 2005 when Bristol was granted Fairtrade City status.[80]

Bristol is unusual in having been a city with county status since medieval times. The county was expanded to include suburbs such as Clifton in 1835, and it was named a county borough in 1889, when the term was first introduced.[24] However, on 1 April 1974, it became a local government district of the short-lived county of Avon.[81] On 1 April 1996, it regained its independence and county status, when the county of Avon was abolished and Bristol became a Unitary authority.[82]

Geography and environment

Boundaries

There are a number of different ways in which Bristol's boundaries are defined, depending on whether the boundaries attempt to define the city, the built-up area, or the wider "Greater Bristol". The narrowest definition of the city is the city council boundary, which takes in a large section of the Severn Estuary west as far as, but not including, the islands of Steep Holm and Flat Holm.[83] A slightly less narrow definition is used by the Office for National Statistics (ONS); this includes built-up areas which adjoin Bristol but are not within the city council boundary, such as Whitchurch village, Filton, Patchway, Bradley Stoke, and excludes non-built-up areas within the city council boundary.[84] The ONS has also defined an area called the "Bristol Urban Area", which includes Kingswood, Mangotsfield, Stoke Gifford, Winterbourne, Frampton Cotterell, Almondsbury and Easton in Gordano.[85] The term "Greater Bristol", used for example by the Government Office of the South West,[86] usually refers to the area occupied by the city and parts of the three neighbouring local authorities (Bath and North East Somerset, North Somerset and South Gloucestershire), an area sometimes also known as the "former Avon area" or the "West of England".[87] The North Fringe of Bristol, a largely developed area within South Gloucestershire, located between the Bristol city boundary and the M4 and M5 motorways, was so named as part of a 1987 Local plan prepared by Northavon District Council.[88]

Physical geography

Bristol is in a limestone area, which runs from the Mendip Hills to the south to the Cotswolds to the north east.[89] The rivers Avon and Frome cut through this limestone to the underlying clays, creating Bristol's characteristic hilly landscape. The Avon flows from Bath in the east, through flood plains and areas which were marshy before the growth of the city. To the west, the Avon has cut through the limestone to form the Avon Gorge, partly aided by glacial meltwater after the last ice age.[90] The gorge helped to protect Bristol Harbour, and has been quarried for stone to build the city. The land surrounding the gorge has been protected from development, as The Downs and Leigh Woods. The gorge and estuary of the Avon form the county's boundary with North Somerset, and the river flows into the Severn Estuary at Avonmouth. There is also another gorge in the city, in the Blaise Castle estate to the north.[90]

Climate

Situated in the south of the country, Bristol is one of the warmest cities in the UK, with a mean annual temperature of 10.2–12 °C (50.4–53.6 °F).[91] It is also amongst the sunniest, with 1,541–1,885 hours sunshine per year.[92]

The city is partially sheltered by the Mendip Hills, but exposed to the Severn Estuary and Bristol Channel. Rainfall increases towards the south of the area, with annual totals north of the Avon River in the 600–900 mm (24–35 in) range, up to the 900–1,200 mm (35–47 in) range south of it.[93] Rain is fairly evenly distributed throughout the year, although autumn and winter are the wettest seasons.

The Atlantic strongly influences Bristol's weather, maintaining average temperatures above freezing throughout the year. However, cold spells in winter often bring frosts. Snow can fall at any time from early November through to late April, but it is an infrequent occurrence. Summers are drier and quite warm, with variable amounts of sunshine, rain and cloud. Spring is unsettled and changeable, and has brought spells of winter snow as well as summer sunshine.[94]

The nearest weather stations to Bristol for which long-term climate data are available are Long Ashton (about 5 miles (8 km) south-west of the city centre) and Bristol Weather Station (within the city centre). However, data collection at these locations ceased in 2002 and 2001 respectively, and Filton Airfield is now the closest weather station.[95] The temperature range at Long Ashton for the period 1959–2002 has spanned from 33.5 °C (92.3 °F) during July 1976,[96] down to −14.4 °C (6.1 °F) in January 1982.[97]

Monthly temperature extremes at Filton (since 2002) exceeding those recorded at Long Ashton include 25.7 °C (78.3 °F) during April 2003,[98] 34.5 °C (94.1 °F) during July 2006[99] and 26.8 °C (80.2 °F) in October 2011.[100] The lowest temperature recorded in recent years at Filton was −10.1 °C (13.8 °F) during December 2010.[101]

Many large cities experience an urban heat island effect, with temperatures being slightly warmer than surrounding rural areas, however there is limited evidence of this effect in Bristol.[102]

| Climate data for Bristol Weather Centre 11 m asl, 1971–2000 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 7.5 (45.5) |

7.4 (45.3) |

10.1 (50.2) |

12.7 (54.9) |

16.5 (61.7) |

18.9 (66.0) |

22.0 (71.6) |

21.0 (69.8) |

18.4 (65.1) |

14.7 (58.5) |

10.5 (50.9) |

8.9 (48.0) |

14.1 (57.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 3.8 (38.8) |

2.9 (37.2) |

4.9 (40.8) |

5.6 (42.1) |

9.0 (48.2) |

11.9 (53.4) |

14.3 (57.7) |

14.0 (57.2) |

12.0 (53.6) |

9.7 (49.5) |

6.3 (43.3) |

5.3 (41.5) |

8.3 (46.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 73 (2.9) |

48 (1.9) |

51 (2.0) |

52 (2.0) |

54 (2.1) |

64 (2.5) |

64 (2.5) |

52 (2.0) |

50 (2.0) |

59 (2.3) |

52 (2.0) |

59 (2.3) |

626.8 (24.68) |

| Source: MeteoFrance[103] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Long Ashton 51 m asl, 1971–2000, extremes 1959–2002 (Sunshine 1971–1989) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 14.2 (57.6) |

18.3 (64.9) |

21.7 (71.1) |

23.0 (73.4) |

26.5 (79.7) |

32.4 (90.3) |

33.5 (92.3) |

33.3 (91.9) |

28.3 (82.9) |

26.1 (79.0) |

17.5 (63.5) |

15.8 (60.4) |

33.5 (92.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 7.5 (45.5) |

7.7 (45.9) |

10.0 (50.0) |

12.4 (54.3) |

16.0 (60.8) |

18.7 (65.7) |

21.1 (70.0) |

20.7 (69.3) |

17.9 (64.2) |

14.1 (57.4) |

10.5 (50.9) |

8.3 (46.9) |

13.7 (56.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 2.1 (35.8) |

1.8 (35.2) |

3.4 (38.1) |

4.5 (40.1) |

7.3 (45.1) |

10.2 (50.4) |

12.4 (54.3) |

12.2 (54.0) |

10.2 (50.4) |

7.4 (45.3) |

4.5 (40.1) |

3.0 (37.4) |

6.6 (43.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −14.4 (6.1) |

−9.7 (14.5) |

−8.3 (17.1) |

−4.7 (23.5) |

−2 (28) |

0.6 (33.1) |

4.7 (40.5) |

3.9 (39.0) |

0.6 (33.1) |

−3.2 (26.2) |

−6.5 (20.3) |

−11.9 (10.6) |

−14.4 (6.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 94.36 (3.71) |

65.47 (2.58) |

73.73 (2.90) |

50.46 (1.99) |

61.30 (2.41) |

68.33 (2.69) |

52.23 (2.06) |

75.02 (2.95) |

85.95 (3.38) |

92.08 (3.63) |

91.62 (3.61) |

102.78 (4.05) |

913.33 (35.96) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 50.53 | 66.39 | 108.19 | 165.3 | 192.82 | 198.0 | 208.01 | 196.23 | 147.9 | 97.65 | 64.8 | 43.09 | 1,538.91 |

| Source 1: Met Office[104] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute[105] | |||||||||||||

Environment

Based on its environmental performance, quality of life, future-proofing and how well it is addressing climate change, recycling and biodiversity, Bristol was ranked as Britain's most sustainable city, topping environmental charity Forum for the Future's Sustainable Cities Index 2008.[106][107] Notable local initiatives include Sustrans, who have created the National Cycle Network, founded as Cyclebag in 1977,[108] and Resourcesaver established in 1988 as a non-profit business by Avon Friends of the Earth.[109] Bristol is the winner of the European Green Capital Award for 2015.[110]

Demographics

| Year | Population | Year | Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1377 | 9,518[111] | 1901 | 323,698[112] |

| 1607 | 10,549[113] | 1911 | 352,178[112] |

| 1700 | 20,000[112] | 1921 | 367,831[112] |

| 1801 | 68,944[112] | 1931 | 384,204[112] |

| 1811 | 83,922[112] | 1941 | 402,839[112] |

| 1821 | 99,151[112] | 1951 | 422,399[112] |

| 1831 | 120,789[112] | 1961 | 425,214[112] |

| 1841 | 144,803[112] | 1971 | 428,089[112] |

| 1851 | 159,945[112] | 1981 | 384,883[112] |

| 1861 | 194,229[112] | 1991 | 396,559[112] |

| 1871 | 228,513[112] | 2001 | 380,615[112] |

| 1881 | 262,797[112] | 2012 | 432,500[114] |

| 1891 | 297,525[112] | - | - |

In 2008 the Office for National Statistics estimated the Bristol unitary authority's population at 416,900,[115][116] making it the 47th-largest ceremonial county in England.[117] Using Census 2001 data the ONS estimated the population of the city to be 441,556,[118] and that of the contiguous urban area to be 551,066.[119] More recent 2006 ONS estimates put the urban area population at 587,400.[120] This makes the city England's sixth most populous city, and ninth most populous urban area.[119] At 3,599 inhabitants per square kilometre (9,321/sq mi) it has the seventh-highest population density of any English district.[121]

According to the 2011 census, 84.0% of the population was White (77.9% White British, 0.9% White Irish, 0.1% Gypsy or Irish Travellers, 5.1% Other White), 3.6% of mixed race (1.7% White and Black Caribbean, 0.4% White and Black African, 0.8% White and Asian, 0.7% Other Mixed), 5.5% Asian (1.5% Indian, 1.6% Pakistani, 0.5% Bangladeshi, 0.9% Chinese, 1.0% Other Asian), 6.0% Black (2.8% African, 1.6% Caribbean, 1.6% Other Black), 0.3% Arab and 0.6% of other ethnic heritage. Bristol is unusual among major British towns and cities in having a larger Black than Asian population.[122]

Historical population records

The statistics apply only to the Bristol Unitary Authority, which excludes areas that are part of the Bristol urban area (2006 estimated population 587,400) but are located in South Gloucestershire, BANES or North Somerset, such as Kingswood, Mangotsfield, Filton, Warmley etc., which border Bristol UA.[112]

Economy and industry

As a major seaport, Bristol has a long history of trading commodities, originally wool cloth exports and imports of fish, wine, grain and dairy produce,[123] later tobacco, tropical fruits and plantation goods; major imports now are motor vehicles, grain, timber, fresh produce and petroleum products. Since the 13th century, the rivers have been modified for use as docks including the diversion of the River Frome in the 1240s into an artificial deep channel known as "Saint Augustine's Reach", which flowed into the River Avon.[124][125] As early as 1420, vessels from Bristol were regularly travelling to Iceland and it is speculated that sailors from Bristol had made landfall in the Americas before Christopher Columbus or John Cabot.[21] The merchants of Bristol, operating under the name of the Society of Merchant Venturers, sponsored probes into the north Atlantic from the early 1480s, looking for possible trading opportunities.[21] In 1552 Edward VI granted a Royal Charter to the Merchant Venturers to manage the port. By 1670, the city had 6,000 tons of shipping, of which half was used for importing tobacco. By the late 17th century and early 18th century, this shipping was also playing a significant role in the slave trade.[21] During the 18th century it was Britain's second busiest port.[126] Deals were originally struck on a personal basis in the former trading area around The Exchange in Corn Street, and in particular, over bronze trading tables, known as "The Nails". This is often given as the origin of the expression "cash on the nail", meaning immediate payment, however it is likely that the expression was in use before the nails were erected.[127]

In addition to Bristol's nautical connections, the city's economy relies on the aerospace industry, defence, the media, information technology, financial services and tourism.[128] The former Ministry of Defence (MoD)'s Procurement Executive, later the Defence Procurement Agency, and now Defence Equipment and Support, moved to a purpose-built headquarters at Abbey Wood, Filton in 1995. The site employs some 7,000 to 8,000 staff and is responsible for procuring and supporting much of the MoD's defence equipment.[129]

In 2004, Bristol's GDP was £9.439 billion. The GDP per head was £23,962 (US$47,738, €35,124) making the city more affluent than the UK as a whole, at 40% above the national average. This makes it the third-highest per-capita GDP of any English city, after London and Nottingham, and the fifth highest GDP per capita of any city in the United Kingdom, behind London, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Belfast and Nottingham.[130] In March 2007, Bristol's unemployment rate was 4.8%, compared with 4.0% for the south west and 5.5% for England.[131]

Bristol's economy no longer relies upon the Port of Bristol, which was relocated gradually to docks at Avonmouth (1870s)[132] and Royal Portbury Dock (1977) as the size of ships increased. The city is the largest importer of cars to the UK. Until 1991 the port was publicly owned, since when it has been leased with £330 million being invested and the annual tonnage throughput has increased from 3.9 million long tons (4 million tonnes) to 11.8 million long tons (12 million tonnes).[133] The tobacco trade and cigarette manufacturing have now ceased, but imports of wines and spirits continue.[134]

The financial services sector employs 59,000 in the city.[135] High tech is also important, with 50 micro-electronics and silicon design companies, employing around 5,000 people. Hewlett-Packard opened its national research laboratories in Bristol during 1983.[136][137] As the UK's seventh most popular destination for foreign tourists, Bristol receives nine million visitors each year.[138]

In the 20th century, Bristol's manufacturing activities expanded to include aircraft production at Filton, by the Bristol Aeroplane Company, and aero-engine manufacture by Bristol Aero Engines (later Rolls-Royce) at Patchway. The aeroplane company became famous for the World War I Bristol Fighter,[139] and Second World War Blenheim and Beaufighter aircraft.[139] In the 1950s it became one of the country's major manufacturers of civil aircraft, with the Bristol Freighter, the Britannia and the huge Brabazon airliner. The Bristol Aeroplane Company diversified into automobile manufacturing in the 1940s, producing hand-built luxury cars at their factory in Filton, under the name Bristol Cars, which became independent from the Bristol Aeroplane Company in 1960.[140] The city also gave its name to the Bristol make of buses, manufactured in the city from 1908 to 1983, first by the local bus operating company, Bristol Tramways, and from 1955 by Bristol Commercial Vehicles.

In the 1960s Filton played a key role in the Anglo-French Concorde supersonic airliner project. The Bristol Aeroplane Company became part of the British partner, the British Aircraft Corporation (BAC). Concorde components were manufactured in British and French factories and shipped to the two final assembly plants, in Toulouse and Filton. The French manufactured the centre fuselage and centre wing and the British the nose, rear fuselage, fin and wingtips, while the Olympus 593 engine's manufacture was split between Rolls-Royce (Filton) and Snecma (Paris). The British Concorde prototype made its maiden flight from Filton to RAF Fairford on 9 April 1969, five weeks after the French test flight.[141] In 2003 British Airways and Air France decided to cease flying the aircraft and to retire them to locations (mostly museums) around the world. On 26 November 2003 Concorde 216 made the final Concorde flight, returning to Filton airfield to be kept there permanently as the centrepiece of a projected air museum. This museum will include the existing Bristol Aero Collection, which includes a Bristol Britannia aircraft.[142]

The aerospace industry remains a major segment of the local economy.[143] The major aerospace companies in Bristol now are BAE Systems, (formed by merger between Marconi Electronic Systems and BAe; the latter being formed by a merger of BAC, Hawker Siddeley and Scottish Aviation), Airbus[144] and Rolls-Royce are all based at Filton, and aerospace engineering is a prominent research area at the nearby University of the West of England. Another important aviation company in the city is Cameron Balloons, who manufacture hot air balloons.[145] Each August the city is host to the Bristol International Balloon Fiesta, one of Europe's largest hot air balloon events.[146]

A new £500 million shopping centre called Cabot Circus opened in 2008 amidst claims from developers and politicians that Bristol would become one of England's top ten retail destinations.[147] Bristol was selected as one of the world's top ten cities for 2009 by international travel publishers Dorling Kindersley in their Eyewitness series of guides for young adults.[148]

In 2011 it was announced that the Temple Quarter near Bristol Temple Meads railway station will become an enterprise zone.[149]

Culture

Arts

The city is famous for its music and film industries, and was a finalist for the 2008 European Capital of Culture, but the title was awarded to Liverpool.[150]

See No Evil, a street art event in Bristol, started in 2011. Bristol is also home to one of the seven national Foodies Festivals,[151] taking place 13–15 July 2012, with master classes by Levi Roots and Ed Baines, as well as city beaches, restaurant tents, pop-up cinemas and burlesque shows.

The city's principal theatre company, the Bristol Old Vic, was founded in 1946 as an offshoot of The Old Vic company in London. Its premises on King Street consist of the 1766 Theatre Royal (607 seats), a modern studio theatre called the New Vic (150 seats), and foyer and bar areas in the adjacent Coopers' Hall (built 1743). The Theatre Royal is a grade I listed building[152][153] and is the oldest continuously operating theatre in England.[154] The Bristol Old Vic Theatre School, which had originated in King Street, is now a separate company. The Bristol Hippodrome is a larger theatre (1,951 seats) which hosts national touring productions. Other theatres include the Tobacco Factory (250 seats), QEH (220 seats), the Redgrave Theatre (at Clifton College) (320 seats) and the Alma Tavern (50 seats). Bristol's theatre scene includes a large variety of producing theatre companies, apart from the Bristol Old Vic company, such as Show of Strength Theatre Company, Shakespeare at the Tobacco Factory and Travelling Light Theatre Company. Theatre Bristol is a partnership between Bristol City Council, Arts Council England and local theatre practitioners which aims to develop the theatre industry in Bristol.[155]

A number of organisations within the city support theatre makers. The Residence "artist led community", for example, provides office, social and rehearsal space for several Bristol-based theatre and performance companies.[156] Equity, the actors union, has a general branch based in the city.[157]

Since the late 1970s, the city has been home to bands combining punk, funk, dub and political consciousness. Among the most notable have been Glaxo Babies,[158] the Pop Group[159] and trip hop or "Bristol Sound" artists such as Tricky,[160] Portishead,[161] and Massive Attack;[162] the list of bands from Bristol is extensive. It is also a stronghold of drum and bass with notable artists such as the Mercury Prize winning Roni Size/Reprazent[163] as well as the pioneering DJ Krust[164] and More Rockers.[165] This music is part of the wider Bristol urban culture scene which received international media attention in the 1990s.[166]

Bristol has many live music venues, the largest of which is the 2,000-seat Colston Hall, named after Edward Colston. Others include the Bristol Academy, The Fleece, The Croft, The Exchange, Fiddlers, Victoria Rooms, Trinity Centre, St George's Bristol and a range of public houses from the jazz-orientated The Old Duke to rock at the Fleece and Firkin, and indie bands at the Louisiana.[167][168] In 2010, PRS for Music announced that Bristol is the most musical city in the UK, based on the number of its members born in Bristol in relation to the size of its population.[169]

The Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery houses a collection of natural history, archaeology, local glassware, Chinese ceramics and art. M Shed, the museum of Bristol, opened in 2011 on the site of the former Bristol Industrial Museum.[170] Both museums are operated by Bristol Museums, Galleries and Archives, which also runs three preserved historic houses – the Tudor Red Lodge, the Georgian House and Blaise Castle House – as well as Bristol Record Office.[171]

The Watershed Media Centre and Arnolfini gallery, both in disused dockside warehouses, exhibit contemporary art, photography and cinema, while the city's oldest gallery is at the Royal West of England Academy in Clifton.[172]

Antlers Gallery, Bristol's nomadic gallery opened in 2010, moving around the city into empty spaces on Park Street, Whiteladies Road and Purifier House on Bristol's Harbourside. The commercial gallery represents Bristol based artists through exhibitions, art fairs and private sales.

Stop frame animation films and commercials produced by Aardman Animations[173] and television series focusing on the natural world have also brought fame and artistic credit to the city.[174] The city is home to the regional headquarters of BBC West, and the BBC Natural History Unit.[175] Locations in and around Bristol have often featured in the BBC's natural history programmes, including the children's television programme Animal Magic, filmed at Bristol Zoo.[176]

In literature, Bristol is noted as the birthplace of the 18th century poets Robert Southey[177] and Thomas Chatterton.[178] Southey, who was born on Wine Street, Bristol in 1774, and his friend Samuel Taylor Coleridge married the Bristol Fricker sisters.[179] William Wordsworth spent time in the city,[180] where Joseph Cottle first published Lyrical Ballads in 1798.[181]

The 18th- and 19th century portrait painter Sir Thomas Lawrence and 19th century architect Francis Greenway, designer of many of Sydney's first buildings, came from the city, and more recently the graffiti artist Banksy, many of whose works can be seen in the city.[182] Some famous comedians are locals, including Justin Lee Collins,[183] Lee Evans,[184] Russell Howard,[185] and writer/comedian Stephen Merchant.[186]

University of Bristol graduates include magician and psychological illusionist Derren Brown;[187] the satirist Chris Morris;[188] Simon Pegg[189] and Nick Frost of Spaced, Shaun of the Dead and Hot Fuzz;[190] and Matt Lucas[191] and David Walliams[191] of Little Britain fame.[191] Hollywood actor Cary Grant was born in the city;[192] along with Dolly Read, UK Stars Ralph Bates and Norman Eshley. Peter O'Toole, Kenneth Cope, Patrick Stewart, Jane Lapotaire, Pete Postlethwaite, Jeremy Irons, Greta Scacchi, Miranda Richardson, Helen Baxendale, Daniel Day-Lewis and Gene Wilder are amongst the many actors who learnt their craft at the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School,[193] opened by Laurence Olivier in 1946. The comedian John Cleese was a pupil at Clifton College.[194] Hugo Weaving studied at Queen Elizabeth's Hospital School[195] and David Prowse (Darth Vader, Star Wars) attended Bristol Grammar School.[196]

Architecture

Bristol has 51 Grade I listed buildings,[153] 500 Grade II* and over 3,800 Grade II buildings,[197] in a wide variety of architectural styles, ranging from the medieval to the 21st century. In the mid-19th century, Bristol Byzantine, an architectural style unique to the city, was developed, of which several examples have survived. Buildings from most of the architectural periods of the United Kingdom can be seen throughout the city. Surviving elements of the fortified city and castle date back to the medieval era,[198] also some churches dating from the 12th century onwards.[199]

Outside the historical city centre there are several large Tudor and later mansions built for wealthy merchants.[200] Of particular note is Kings Weston House in the north of the city, designed by Sir John Vanbrugh and the only Vanbrugh building to be found in any UK city outside London. Almshouses[201] and public houses of the same period still exist,[202] intermingled with modern development. Several Georgian-era squares were laid out for the enjoyment of the middle class as prosperity increased in the 18th century.[203]

During World War II, the city centre suffered from extensive bombing during the Bristol Blitz.[204] The central shopping area around Wine Street and Castle Street was particularly badly hit, and architectural treasures such as the Dutch House and St Peter's Hospital were lost. Nonetheless in 1961 Betjeman still considered Bristol to be 'the most beautiful, interesting and distinguished city in England'.[205]

The redevelopment of shopping centres, office buildings, and the harbourside continues apace.

Sport in Bristol

Bristol has one Football League club, Bristol City and several non-league clubs, including Bristol Rovers, Mangotsfield United, Bristol Manor Farm and Brislington F.C.. Bristol City was formed in 1897, became runners-up in Division One in 1907, and losing FA Cup finalists in 1909. They returned to the top flight in 1976, but slowly descended to the bottom professional tier where, after bankruptcy in 1982 they reformed and climbed the league again. They were promoted to the second tier of English football in 2007. The team lost in the play-off final of the Championship to Hull City (2007–08 season). City announced plans for a new 30,000 all-seater stadium to replace their home, Ashton Gate.[65]

Bristol Rovers is the oldest professional football team in Bristol, formed in 1883. During their history, Rovers have been champions of the third tier (Division Three South in 1952–53 and Division Three in 1989–90), Watney Cup Winners (1972, 2006–07), and runners-up in the Johnstone's Paint Trophy. The Club has planning permission to build a new 21,700 capacity all-seater stadium on land at the University of the West of England's Frenchay campus. Construction of the new stadium is due to commence in Summer 2014, after a 12-month delay caused by a local pressure-group launching a Judicial Review over the redevelopment at the Memorial Stadium site.[206]

The city is also home to Bristol Rugby rugby union club,[207] a first-class cricket side, Gloucestershire C.C.C.[208] and a Rugby League Conference side, the Bristol Sonics. The city also stages an annual half marathon, and in 2001 played host to the World Half Marathon Championships. There are several athletics clubs in Bristol, including Bristol and West AC, Bitton Road Runners and Westbury Harriers. Speedway racing was staged, with breaks, at the Knowle Stadium from 1928 to 1960, when it was closed and the site redeveloped. The sport briefly returned to the city in the 1970s when the Bulldogs raced at Eastville Stadium.[209] In 2009, senior ice hockey returned to the city for the first time in 17 years with the newly formed Bristol Pitbulls playing out of Bristol Ice Rink.

Motor racing has strong roots in Bristol with Joe Fry setting many records in the Freikaiserwagen and events held around the city. Speed trials have been staged in Clapton-in-Gordano, Shipham, Backwell, Naish, Dyrham Park, Filton Airfield and in Whitchurch (then Bristol's airport). A stage of the 1983 RAC Rally was held in the Ashton Court Estate. To this day, a sporting trial is held in woodland on the outskirts of the city and a classic trial is held in the hills surrounding the city.

The Bristol International Balloon Fiesta, a major event for hot-air ballooning in the UK, is held each summer in the grounds of Ashton Court, to the west of the city.[210] The fiesta draws substantial crowds even for the early morning lift beginning at about 6.30 am. Events and a fairground entertain visitors throughout the day. A second mass ascent is made in the early evening, again taking advantage of lower wind speeds. Until 2007 Ashton Court also played host to the Ashton Court Festival each summer, an outdoor music festival known as the Bristol Community Festival.

For mountain biking in Bristol, the main area is around the Ashton Court estate, with the Timberland trails being the main route. There are also routes across the road in the Plantation, the 50 acre wood and Leigh Woods.[211]

Media

Bristol has two daily newspapers, the Western Daily Press and the Bristol Evening Post; a weekly free newspaper, the Bristol Observer; and a Bristol edition of the free Metro newspaper, all owned by the Daily Mail and General Trust.[212] The city has several local radio stations, including BBC Radio Bristol, Heart Bristol (previously known as GWR FM), Classic Gold 1260, Kiss 101, The Breeze (formerly Star 107.2), BCFM (a community radio station launched March 2007), Ujima 98 FM,[213] 106 Jack FM,[214] as well as two student radio stations, The Hub and BURST, and an internet radio station from the Jewish and Muslim communities of the city, Radio Salaam Shalom. Bristol also boasts television productions such as ITV News West Country for ITV West & Wales (formerly HTV West) and ITV Westcountry, Points West for BBC West, hospital drama Casualty (which has moved filming to Cardiff since 2012)[215] and Endemol productions such as Deal or No Deal. Bristol has been used as a location for the Channel 4 comedy drama Teachers, BBC drama Mistresses, E4 teen drama Skins and BBC3 comedy-drama series Being Human (which has since moved to Barry from series 3 onwards).

Independent publishers based in the city have included the 18th century, Bristolian Joseph Cottle, who was largely responsible for the launch of the Romantic Movement by publishing the works of William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge.[216] In the 19th century, J.W. Arrowsmith published the Victorian comedy classics Three Men in a Boat, by Jerome K. Jerome, and The Diary of a Nobody, by George and Weedon Grossmith.[217] Current publishers include the Redcliffe Press, which has published over 200 books on all aspects of the city.[218]

Bristol is home to the YouTube video-game group The Yogscast. Co-Founders, Simon Lane and Lewis Brindley moved operations from their shared house in Reading to Bristol in 2012.[citation needed] Other members of the network moved to Bristol to work in-office. Though their main office is in Bristol, the network has members in Scotland,the island of Jersey, the USA and Europe.[citation needed]

Dialect

A dialect of English is spoken by some Bristol inhabitants, known colloquially as Bristolian, "Bristolese" or even, following the publication of Derek Robson's "Krek Waiters peak Bristle", as "Bristle" or "Brizzle". Bristol natives speak with a rhotic accent, in which the post-vocalic r in words like car and card is still pronounced, having been lost from many other dialects of English, notably BBC English, or RP, i.e., "received pronunciation". The unusual feature of this accent, unique to Bristol, is the so-called Bristol L (or terminal L), in which an L sound appears to be appended to words that end in an 'a' or 'o'.[219] There is some dispute about whether this is broad "l" or "w".[220] Thus "area" becomes "areal" or "areaw", etc. The "-ol" ending of the city's name is a significant example of the occurrence of the so-called "Bristol L". Bristolians using the dialect tend to pronounce "a" and "o" at the end of a word almost as "aw", hence "cinemaw". To the stranger's ear this pronunciation sounds as if there is an "L" after the vowel.[221][222]

Further Bristolian linguistic features are an additional "to" in questions relating to direction or orientation, or using "to" instead of "at" (features also common to the coastal towns of South Wales probably reflecting the use of "tu" in Welsh, e.g., "Y mae efe tu maes" – "That is he to outside" = "He/It is outside"); and using male pronouns "he" and "him" instead of "it".[223][224] For example, "Where is it?" would be phrased as "Where's he to?" and "Where's that" as "Where's that to", a structure exported to Newfoundland English.[225]

Until recent times the dialect was characterised by retention of the second person singular as in the famous piece of doggerel, "Cassn't see what bist looking at? Cassn't see as well as couldst, casst? And if couldst, 'ouldn't, 'ouldst?" Notice the use of West Saxon "bist" for English "art".[226] Children could be admonished with, "Thee and thou, the Welshman's cow". As in French and German, use of the second person singular to a superior or parent was not permitted in Bristolese (except by Quakers with their notions of equality for all). The pronoun form 'thee' is also used in the subject position (e.g., 'What bist thee doing?') while 'I'/'he' are used in the object position (e.g., 'Give he to I.').[227]

Stanley Ellis, a dialect researcher, found that many of the dialect words in the Filton area were linked to work in the aerospace industry. He described this as "a cranky, crazy, crab-apple tree of language and with the sharpest, juiciest flavour that I've heard for a long time".[228]

Religion

In the United Kingdom Census 2011, 46.8% of Bristol's population reported themselves as being Christian, and 37.4% stated they were not religious; the national England averages are 59.4% and 24.7% respectively. Islam accounts for 5.1% of the population, Buddhism 0.6%, Hinduism 0.6%, Sikhism 0.5%, Judaism 0.2% and other religions 0.7%, while 8.1% did not state a religion.[229]

The city has many Christian churches, the most notable being the Anglican Bristol Cathedral and St Mary Redcliffe, and the Roman Catholic Clifton Cathedral. Nonconformist chapels include Buckingham Baptist Chapel and John Wesley's New Room in Broadmead.[230] St James's Presbyterian church was bombed on 24 November 1940, never to be used as a church again.[231] Its bell tower remains but the nave has been converted to offices.[232]

In Bristol, other religions are served by eleven mosques,[233] several Buddhist meditation centres,[234] a Hindu temple,[235] Progressive and Orthodox synagogues,[236] and four Sikh temples.[237][238][239]

Education, science and technology

Bristol is home to two major institutions of higher education: the University of Bristol, a "redbrick" chartered in 1909, and the University of the West of England, formerly Bristol Polytechnic, which gained university status in 1992. In addition the University of Law has a campus in the city. Bristol also has two dedicated further education institutions, City of Bristol College and South Gloucestershire and Stroud College, and three theological colleges, Trinity College, Wesley College and Bristol Baptist College. The city has 129 infant, junior and primary schools,[240] 17 secondary schools,[241] and three city learning centres. It has the country's second highest concentration of independent school places, after an exclusive corner of north London.[242] The independent schools in the city include Clifton College, Clifton High School, Badminton School, Bristol Grammar School, Redland High School, Queen Elizabeth's Hospital (the only all-boys school) and Red Maids' School, which claims to be the oldest girls' school in England, having been founded in 1634 by John Whitson.[243]

In 2005, Gordon Brown, then Chancellor of the Exchequer recognised Bristol's ties to science and technology by naming it one of six "science cities", and promising funding for further development of science in the city,[244] with a £300 million science park planned at Emersons Green.[245] As well as research at the two universities, Bristol Royal Infirmary, and Southmead Hospital, science education is important in the city, with At-Bristol, Bristol Zoo, Bristol Festival of Nature and the Create Centre[246] being prominent local institutions involved in science communication.

The city has a history of scientific luminaries, including the 19th century chemist Sir Humphry Davy,[247] who worked in Hotwells. Bishopston gave the world physicist Paul Dirac, who received the Nobel Prize in 1933 for crucial contributions to quantum mechanics.[248] Cecil Frank Powell was Melvill Wills Professor of Physics at Bristol University when he was awarded the Nobel prize for a photographic method of studying nuclear processes and associated discoveries in 1950. The city was the birthplace of Colin Pillinger,[249] planetary scientist behind the Beagle 2 Mars-lander project, and was home to the neuropsychologist Richard Gregory, founder of the Exploratory, a hands-on science centre, precursor of at-Bristol.[250]

Initiatives such as the Flying Start Challenge help encourage secondary school pupils around the Bristol area to take an interest in Science and Engineering. Links with major aerospace companies promote technical disciplines and advance students' understanding of practical design.[251] The Bloodhound SSC project, aiming to break the land speed record, is based at the Bloodhound Technology Centre on Bristol's harbourside.[252]

Transport

Template:Bristol railway map/collapse Bristol has two principal railway stations. Bristol Temple Meads, near the centre, sees mainly First Great Western services, including regular high speed trains to London Paddington, as well as other local, regional and CrossCountry trains. Bristol Parkway, to the north of the city, is mainly served by high speed First Great Western services between Cardiff and London, and CrossCountry services to Birmingham and the North East. A limited service to London Waterloo via Clapham Junction from Bristol Temple Meads is operated by South West Trains. There are also scheduled coach links to most major UK cities.[253]

The M4 motorway connects the city with an east-west axis from London to West Wales, while the M5 provides a north–southwest axis from Birmingham to Exeter. Also within the county is the M49 motorway, a short cut between the M5 in the south and M4 Severn Crossing in the west. The M32 motorway is a spur from the M4 to the city centre.[253]

Bristol Airport (BRS), at Lulsgate, has seen substantial investments in its runway, terminal and other facilities since 2001.[253]

Public transport in the city consists largely of its bus network, provided mostly by FirstGroup, formerly the Bristol Omnibus Company. Other services are provided by Abus,[254] Wessex Red (Operated by Wessex for the two universities),[255] and Wessex.[256] Buses in the city have been widely criticised for being unreliable and expensive; in 2005 First was fined for delays and safety violations.[257][258]

Private car usage in Bristol is high. The city suffers from congestion, costing an estimated £350 million per year.[259] Bristol is motorcycle friendly; the city allows motorcycles to use most of the city's bus lanes, as well as providing secure free parking.[260] Since 2000 the city council has included a light rail system in its local transport plan, but has so far been unwilling to fund the project. The city was offered European Union funding for the system, but the Department for Transport did not provide the required additional funding.[261] As well as support for public transport, there are several road building schemes supported by the local council, including re-routing and improving the South Bristol Ring Road.[262] There are also three park and ride sites serving the city, supported by the local council.[263] The central part of the city has water-based transport, operated by the Bristol Ferry Boat, Bristol Packet and Number Seven Boat Trips providing leisure and commuter services on the harbour.[264]

Bristol's principal surviving suburban railway is the Severn Beach Line to Avonmouth and Severn Beach. The Portishead Railway was closed to passengers under the Beeching Axe, but was relaid for freight only in 2000–2002 as far as the Royal Portbury Dock with a Strategic Rail Authority rail-freight grant. Plans to relay a further 3 miles (5 km) of track to Portishead, a largely dormitory town with only one connecting road, have been discussed but there is insufficient funding to rebuild stations.[265] Rail services in Bristol suffer from overcrowding and there is a proposal to increase rail capacity under the Greater Bristol Metro scheme.[266]

Bristol was named "England's first 'cycling city'" in 2008,[267] and is home to the sustainable transport charity Sustrans. It has a number of urban cycle routes, as well as links to National Cycle Network routes to Bath and London, to Gloucester and Wales, and to the south-western peninsula of England. Cycling has grown rapidly in the city, with a 21% increase in journeys between 2001 and 2005.[259]

Twin cities

Bristol was among the first cities to adopt the idea of town twinning. Its twin towns include:

Bordeaux,[268][269] France since 1947

Bordeaux,[268][269] France since 1947 Hanover,[270] Germany since 1947, the first post-war twinning of British and German cities.

Hanover,[270] Germany since 1947, the first post-war twinning of British and German cities.

Other twinnings include:

Porto, Portugal since 1984[271]

Porto, Portugal since 1984[271] Tbilisi, Georgia since 1988,[272]

Tbilisi, Georgia since 1988,[272] Puerto Morazán, Nicaragua since 1989[273]

Puerto Morazán, Nicaragua since 1989[273] Beira, Mozambique since 1990[274]

Beira, Mozambique since 1990[274] Guangzhou, China since 2001[275][276]

Guangzhou, China since 2001[275][276] Bristol, Virginia & Bristol, Tennessee, USA[citation needed]

Bristol, Virginia & Bristol, Tennessee, USA[citation needed]

See also

- Outline of England

- Bristol Pound

- Buildings and architecture of Bristol

- Healthcare in Bristol

- Parks of Bristol

- List of people from Bristol

- Subdivisions of Bristol

- Maltese cross (unofficial county flower)

- Hotel Bristol, explaining why so many hotels worldwide carry the name.

- W.D. & H.O. Wills

References

- ^ Lord-Lieutenant of the County & City of Bristol. Retrieved 20 August 2014

- ^ "Historical Weather for Bristol, England, United Kingdom". Weatherbase. Canty & Associates. June 2011. Retrieved 3 August 2007.

- ^ "The Population of Bristol August 2013" (PDF). Bristol City Council. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ "2011 Census: Ethnicgroup, local authorities in England and Wales". Census 2011. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ^ a b "Global city GDP 2014". Brookings Institution. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- ^ "The population of Bristol". Bristol City Council. Retrieved 26 January 2015

- ^ "Bristol Facts". University of the West of England. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ^ "Overview of history, facts and visiting Bristol for media". Visit Bristol. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ^ Manco, Jean (25 July 2009). "The Ranking of Provincial Towns in England 1066–1861". Delving into building history. Jean Manco. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- ^ Norwood, Graham (30 October 2007). "Bristol: seemingly unstoppable growth". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 18 December 2007.

- ^ "Famous Bristolians". Mintinit.com. Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- ^ Jean Manco (2006). "Ricart's View of Bristol". Bristol Magazine.

- ^ "The Palaeolithic in Bristol". Bristol City Council. 24 April 2007. Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 6 May 2007.

- ^ Bates, M.R.; Wenban-Smith, F.F. "Palaeolithic Research Framework for the Bristol Avon Basin" (PDF). Bristol City Council. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- ^ "Bristol in the Iron Age". Bristol City Council. Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 10 March 2007.

- ^ "Abona – Major Romano-British Settlement". Roman-Britain.org. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

- ^ "Bristol in the Roman Period". Bristol City Council. Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 10 March 2007.

- ^ Little, Bryan (1967). The City and County of Bristol. Wakefield: S. R. Publishers. p. ix. ISBN 0-85409-512-8.

- ^ a b Lobel, M. D.; Carus-Wilson, Eleanora Mary (1975). "Bristol". In M. D. Lobel (ed.) (ed.). The Atlas of Historic Towns. Vol. 2. London. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-0859671859.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "The Impregnable City". Bristol Past. Retrieved 7 October 2007.

- ^ a b c d Brace, Keith (1976). Portrait of Bristol. London: Robert Hale. pp. 13–15. ISBN 978-0-7091-5435-8. Cite error: The named reference "Brace" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Bristol Bridge". Images of England. English Heritage. Retrieved 22 December 2006.

- ^ Staff (2011). "High Sheriff – City of Bristol County History". highsheriffs.com. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- ^ a b Rayfield, Jack (1985). Somerset & Avon. London: Cadogan. pp. 17–23. ISBN 0-947754-09-1.

- ^ a b Carus-Wilson, Eleanora Mary (1933). "The overseas trade of Bristol". In Power, Eileen; Postan, M.M. (eds.). Studies in English Trade in the Fifteenth Century. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 183–246. ISBN 9781136619717.

- ^ McCulloch, John Ramsay (1839). A Statistical Account of the British Empire. London: Charles Knight and Co. pp. 398–399.

- ^ "History in Bristol". Discover Bristol. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ^ Childs, Wendy R. (1982). "Ireland's trade with England in the Later Middle Ages". Irish Economic and Social History. IX: 5–33.

- ^ Carus-Wilson, Eleanora Mary (1966). "The Iceland trade". In Power, Eileen; Postan, M.M. (eds.). Studies in English Trade in Fifteenth Century. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 155–182. ISBN 9781136619717.

- ^ Jenks, S. (2006). Robert Sturmy's Commercial Expedition to the Mediterranean (1457/8). Vol. 58. Bristol Record Society Publications. p. 1. ISBN 978-0901538284.

- ^ Jones, Evan T. (2008). "Alwyn Ruddock: 'John Cabot and the Discovery of America'". Historical Research. 81 (212): 231–34. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2281.2007.00422.x.

- ^ Williamson, J.A. (1962). The Cabot Voyages and Bristol Discovery Under Henry VII. (Hakluyt Society, Second Series, No. 120, CUP.

- ^ Jones, Evan T. (August 2010). "Henry VII and the Bristol expeditions to North America: the Condon documents". Historical Research. 83 (221): 444–454. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2281.2009.00519.x. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ^ Connell-Smith, Gordon K. (1954). Forerunners of Drake: A Study of English Trade with Spain in the Early Tudor period. Published for the Royal Empire Society by Longmans, Green.

- ^ Jones, Evan T. (February 2001). "Illicit business: accounting for smuggling in mid-sixteenth-century Bristol". The Economic History Review. 54 (1): 17–38. doi:10.1111/1468-0289.00182. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ^ Croft, Pauline (June 1989). "Trading with the Enemy 1585–1604". The Historical Journal. 32 (2): 281–302. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00012152. JSTOR 2639602.

- ^ Jones, Evan T. (June 2012). "Inside the Illicit Economy: Reconstructing the Smugglers' Trade of Sixteenth Century Bristol". Ashgate. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ^ Horn, Joyce M (1996). "BRISTOL: Introduction". Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1541–1857: volume 8: Bristol, Gloucester, Oxford and Peterborough dioceses. Institute of Historical Research: 3–6. Retrieved 14 March 2009.

- ^ Bettey, Joseph (1996). St Augustine's Abbey, Bristol. Bristol: Bristol Branch of the Historical Association. pp. 1–5. ISBN 0-901388-72-6.

- ^ Appendix to the First Report of the Commissioners Appointed to inquire into the Municipal Corporations of England and Wales. 1835. p. 1158. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ "Royal Fort dig". University of Bristol. 21 April 2009. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- ^ a b "Triangular trade". National Maritime Museum. Retrieved 22 March 2009.

- ^ "Black Lives in England : The Slave Trade and Abolition". English Heritage. Archived from the original on 12 June 2008. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ^ "Lottery Fund rejects Bristol application in support of a major exhibition to commemorate the 200th Anniversary of the Abolition of the Slave Trade" (PDF). British Empire & Commonwealth Museum. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- ^ "Seven Stars, Slavery and Freedom!". Bristol Radical History Group. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- ^ Cathcart, Brian (19 March 1995). "Rear Window: Newfoundland: Where fishes swim, men will fight". The Independent. London. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ^ "Samuel Plimsoll – the seaman's friend". BBC – Bristol – History. Retrieved 16 March 2009.

- ^ Buchanan, R A; Cossons, Neil (1969). "2". The Industrial Archaeology of the Bristol Region. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. pp. 32–33. ISBN 978-0-7153-4394-4.

- ^ Harvey, Charles; Press, Jon. "Industrial Change in Bristol Since 1800. Introduction". Bristol Historical Resource. University of the West of England. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ^ Hunt, Henry (1818). Memoirs of Henry Hunt, Esq. Vol. 3. Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 14 March 2009.

- ^ "BBC – Made in Bristol – 1831 Riot facts". BBC News. Retrieved 15 March 2009.

- ^ "Royal Edward Dock, Avonmouth". Engineering Timelines. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ^ Wessex Archaeology (November 2008). "Appendix H Cultural_Heritage" (PDF). eon-uk.com. p. H–4. Retrieved 20 June 2011.

- ^ Staff (2011). "BAC 100: 2010–1910s". bac2010.co.uk. Retrieved 20 June 2011.

- ^ Staff (2011). "How the University is run". Bristol University. Retrieved 20 June 2011.

- ^ Staff (21 February 2008). "Bristol University | News from the University | Wills Memorial Building". University of Bristol. Retrieved 20 June 2011.

- ^ Staff (2011). "UWE history timeline". UWE Bristol. Retrieved 20 June 2011.

- ^ Lambert, Tim. "A brief history of Bristol". Local Histories. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ^ Penny, John. "The Luftwaffe over Bristol". Fishponds Local History Society. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ^ "Four figures on Arno's Gateway". National Recording Project. Public Monument and Sculpture Association. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 19 March 2007.

- ^ "Demolition of city tower begins". BBC News. 13 January 2006. Retrieved 10 March 2007.

- ^ Atkinson, David; Laurier, David (May 1998). "A sanitised city? Social exclusion at Bristol's 1996 international festival of the sea". Geoforum. 29 (2): 199–206. doi:10.1016/S0016-7185(98)00007-4.

- ^ "History". Bristol Rugby. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ^ "Bristol Rovers FC". Football Ground Guide. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ^ a b "Potted History". Bristol City FC. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ^ "Bristol City New Stadium". Bristol City New Stadium. Archived from the original on 1 January 2012. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ^ "Wards up for future elections". Bristol City Council. Archived from the original on 5 December 2009. Retrieved 22 July 2007.

- ^ "Council leader battle resolved". BBC News. 27 May 2007. Retrieved 31 May 2007.

- ^ "Labour 'lost council confidence'". BBC News Bristol. 25 February 2009. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- ^ "Lib Dems take control of Bristol". BBC News. 5 June 2009. Retrieved 5 June 2009.

- ^ Morris, Steven (16 November 2012). "Bristol mayoral election won by independent George Ferguson". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ^ "Council elects Lord Mayor and approves the appointment of City Director". Bristol City Council. Retrieved 27 October 2013.

- ^ "Bristol's Members of Parliament and Members of the European Parliament". Bristol City Council. 2005. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ^ "Bristol North West". Election 2010. BBC. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ^ "Edmund Burke, Speech to the Electors of Bristol". University of Chicago. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ^ Wills, Garry. "Edmund Burke Against Grover Norquist". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ^ Harrison, Brian H. "Lawrence, Emmeline Pethick-, Lady Pethick-Lawrence (1867–1954), suffragette". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ^ "Mr Tony Benn". Hansard. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ^ Alan Rusbridger (10 November 2005). "In praise of ... the Race Relations Acts". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 12 May 2007.

- ^ Morris, Steven (4 March 2005). "From slave trade to fair trade, Bristol's new image". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 14 March 2009.

- ^ "Local Government Bill (Hansard, 16 November 1971)". hansard.millbanksystems.com. Retrieved 7 March 2009.

- ^ "The Avon (Structural Change) Order 1995". www.opsi.gov.uk. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ^ "Area boundary for the Bristol unitary authority". NOMIS Labour market statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ Pointer, Graham (2005). "The UK's major urban areas" (PDF). Focus on People and Migration. Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- ^ "Usual resident population: Census 2001, Key Statistics for urban areas". Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original (xls) on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ Atkins (2005). "Greater Bristol Strategic Transport Study" (PDF). South West Regional Assembly. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 April 2012. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ^ Staff (4 February 2011). "Avon and Somerset safety camera team to be disbanded". BBC News. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- ^ "Town and Country Planning Acts" (PDF). London Gazette. 24 July 1987. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ^ "CotswoldS AONB". Cotswold AONB. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ^ a b Hawkins, Alfred Brian (1973). "The geology and slopes of the Bristol region". Quarterly Journal of Engineering Geology and Hydrogeology. 6 (3–4). London: Geological Society of London: 185–205. doi:10.1144/GSL.QJEG.1973.006.03.02.

- ^ "Average annual temperature". Meteorological Office. 2000. Retrieved 12 May 2007.

- ^ "Average annual sunshine". Meteorological Office. 2000. Retrieved 12 May 2007.

- ^ "National Meteorological Library and Archive Fact sheet 7 — Climate of South West England" (PDF). Meteorological Office. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ "Average annual rainfall". Meteorological Office. 2000. Retrieved 12 May 2007.

- ^ "Weather Station Location". Meteorological Office. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ^ "1976 temperature". Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ^ "1982 temperature". Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ^ "Filton April temperature". TuTiempo. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ^ "Filton July temperature". TuTiempo. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ^ "Filton Oct temperature". TuTiempo. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ^ "Filton December temperature". TuTiempo. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ^ Hughes, Karen (2006). "The impact of urban areas on climate in the UK: a spatial and temporal analysis, with an emphasis on temperature and precipitation effects". Earth and Environment. 2: 54–83.

- ^ "MétéoFrance". Monde.meteofrance.com. Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- ^ "Long Ashton Long term averages". Meteorological Office. November 2011. Archived from the original on 22 December 2003. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- ^ "Long Ashton Extremes". Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (9 November 2008). "Bristol is Britain's greenest city". Evening Post. Bristol News and Media. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ^ "Sustainable Cities Index 2008". Forum for the Future. 25 November 2008. Archived from the original on 18 April 2009. Retrieved 5 July 2009.

- ^ Sustrans, 2002. The Official Guide to the National Cycle Network. 2nd ed. Italy: Canile & Turin. ISBN 1-901389-35-9. Relevant section reproduced here [1].

- ^ "Resourcesaver: Home Page". Beehive. Bristol News and Media. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 5 July 2009.

- ^ "2015-Bristol". European Commission. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ Russell, Joshiah Cox (1948). British Medieval Population. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. pp. 142–143.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w "Bristol England through time – Population Statistics – Total Population". Great Britain Historical GIS Project. University of Portsmouth. Retrieved 21 June 2009.

- ^ Latimer, John (1900). Annals of Bristol in the seventeenth century. Bristol: William George's Sons. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-143-19839-7.

- ^ "Mid-2012 Population Estimates" (PDF). Bristol City Council. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ "Mid 2007 population". Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ^ "Population Estimates". Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 22 February 2009. Retrieved 27 February 2009.

- ^ "ONS 2005 Mid-Year Estimates". Office for National Statistics. 20 December 2005. Archived from the original on 12 March 2007. Retrieved 12 May 2007.

- ^ "Usual resident population". Office for National Statistics, Census 2001. 5 August 2004. Archived from the original on 21 April 2007. Retrieved 12 May 2007.

- ^ a b "The UKs major urban areas" (PDF). Office for National Statistics, 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2007.

- ^ "The Population of Bristol". Bristol City Council. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 September 2010. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ^ "ONS 2005 Mid-Year Estimates". Office for National Statistics. 10 October 2006. Archived from the original on 2 March 2007. Retrieved 12 May 2007.

- ^ "2011 Census: Ethnic group, local authorities in England and Wales". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ^ Henry Bush (1828). "Chapter 3: Murage, keyage and pavage". Bristol Town Duties: A collection of original and interesting documents [etc.] Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ^ "Picturing the Docks". Responses: Andy Foyle. Retrieved 28 January 2007.

- ^ Watson, Sally (1991) Secret Underground Bristol. Bristol: Bristol Junior Chamber. ISBN 0-907145-01-9

- ^ "Bristol harbour reaches 200 years". BBC. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- ^ Knowles, Elizabeth (2006). The Oxford Dictionary of Phrase and Fable. Oxford University Press. p. 723. ISBN 0-19-860219-7.

- ^ "Bristol Local Economic Assessment March 2011" (PDF). Bristol City Council. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ^ "History of the Ministry of Defence" (PDF). Ministry of Defence. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ^ "Sub-regional: Gross value added1 (GVA) at current basic price". Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original (xls) on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ^ "Lead Key Figures". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 14 March 2009.