Greeks

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 14 – c. 17 million[1][2] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

(2011 census) | |

| 1,279,000–3,000,000b (2016 estimate)[5][6] | |

| 650,000–721,000a (2011 estimate)[7][8][9] | |

| 395,000g (2012 estimate)[10] | |

| 378,300 (2011 census)[11] | |

| 290,000–345,000 (2011 estimate)[12] | |

| 252,960 (2011 census)[13] | |

| 200,000[14] | |

| 91,000 (2011 data)[15] | |

| 85,640 (2010 census)[16] | |

| 30,000–200,000d (2013 estimate)[17][18][19] | |

| 50,000e[20] | |

| 45,000 (2011 estimate)[21] | |

| 35,000 (2013 estimate)[22] | |

| 35,000 (2011 estimate)[23] | |

| 20,000–30,000 (2013 estimate)[24] | |

| 28,500 (2011 estimate)[25] | |

| 15,000 (2011 estimate)[26] | |

| 12,000–15,000 (2011 estimate)[27] | |

| 12,000[28] | |

| 10,000–12,000 (2011 estimate)[29] | |

| 11,000 (2015 estimate)[30] | |

| 10,000 (2013 estimate)[31] | |

| 9,500 (2000 estimate)[32] | |

| 4,000[33][34] | |

| Languages | |

| Greek | |

| Religion | |

| mostly | |

a Citizens of Greece and the Republic of Cyprus. The Greek government does not collect information about ethnic self-determination at the national censuses. b Includes those of ancestral descent. c Those whose stated ethnic origins included "Greek" among others. The number of those whose stated ethnic origin is solely "Greek" is 145,250. An additional 3,395 Cypriots of undeclared ethnicity live in Canada. dApprox. 60,000 Griko people and 30,000 post WW2 migrants. e "Including descendants". gIncludes people with "cultural roots". | |

The Greeks or Hellenes (/ˈhɛliːnz/; Template:Lang-el, Éllines [ˈelines]) are an ethnic group native to Greece, Cyprus, southern Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt and, to a lesser extent, other countries surrounding the Mediterranean Sea. They also form a significant diaspora, with Greek communities established around the world.[35]

Greek colonies and communities have been historically established on the shores of the Mediterranean Sea and Black Sea, but the Greek people have always been centered on the Aegean and Ionian seas, where the Greek language has been spoken since the Bronze Age.[36][37] Until the early 20th century, Greeks were distributed between the Greek peninsula, the western coast of Asia Minor, the Black Sea coast, Cappadocia in central Anatolia, Egypt, the Balkans, Cyprus, and Constantinople.[37] Many of these regions coincided to a large extent with the borders of the Byzantine Empire of the late 11th century and the Eastern Mediterranean areas of ancient Greek colonization.[38] The cultural centers of the Greeks have included Athens, Thessalonica, Alexandria, Smyrna, and Constantinople at various periods.

Most ethnic Greeks live nowadays within the borders of the modern Greek state and Cyprus. The Greek genocide and population exchange between Greece and Turkey nearly ended the three millennia-old Greek presence in Asia Minor. Other longstanding Greek populations can be found from southern Italy to the Caucasus and southern Russia and Ukraine and in the Greek diaspora communities in a number of other countries. Today, most Greeks are officially registered as members of the Greek Orthodox Church.[39]

Greeks have greatly influenced and contributed to culture, arts, exploration, literature, philosophy, politics, architecture, music, mathematics, science and technology, business, cuisine, and sports, both historically and contemporarily.

History

The Greeks speak the Greek language, which forms its own unique branch within the Indo-European family of languages, the Hellenic.[37] They are part of a group of classical ethnicities, described by Anthony D. Smith as an "archetypal diaspora people".[41][42]

Origins

The Proto-Greeks probably arrived at the area now called Greece, in the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, at the end of the 3rd millennium BC.[43][44][note 1] The sequence of migrations into the Greek mainland during the 2nd millennium BC has to be reconstructed on the basis of the ancient Greek dialects, as they presented themselves centuries later and are therefore subject to some uncertainties. There were at least two migrations, the first being the Ionians and Aeolians, which resulted in Mycenaean Greece by the 16th century BC,[48][49] and the second, the Dorian invasion, around the 11th century BC, displacing the Arcadocypriot dialects, which descended from the Mycenaean period. Both migrations occur at incisive periods, the Mycenaean at the transition to the Late Bronze Age and the Doric at the Bronze Age collapse.

An alternative hypothesis has been put forth by linguist Vladimir Georgiev, who places Proto-Greek speakers in northwestern Greece by the Early Helladic period (3rd millennium BC), i.e. towards the end of the European Neolithic.[50] Linguists Russell Gray and Quentin Atkinson in a 2003 paper using computational methods on Swadesh lists have arrived at a somewhat earlier estimate, around 5000 BC for Greco-Armenian split and the emergence of Greek as a separate linguistic lineage around 4000 BC.[51]

Mycenaean

In c. 1600 BC, the Mycenaean Greeks borrowed from the Minoan civilization its syllabic writing system (i.e. Linear A) and developed their own syllabic script known as Linear B,[52] providing the first and oldest written evidence of Greek.[52][53] The Mycenaeans quickly penetrated the Aegean Sea and, by the 15th century BC, had reached Rhodes, Crete, Cyprus and the shores of Asia Minor.[37][54]

Around 1200 BC, the Dorians, another Greek-speaking people, followed from Epirus.[55] Traditionally, historians have believed that the Dorian invasion caused the collapse of the Mycenaean civilization, but it is likely the main attack was made by seafaring raiders (Sea Peoples) who sailed into the eastern Mediterranean around 1180 BC.[56] The Dorian invasion was followed by a poorly attested period of migrations, appropriately called the Greek Dark Ages, but by 800 BC the landscape of Archaic and Classical Greece was discernible.[57]

The Greeks of classical antiquity idealized their Mycenaean ancestors and the Mycenaean period as a glorious era of heroes, closeness of the gods and material wealth.[58] The Homeric Epics (i.e. Iliad and Odyssey) were especially and generally accepted as part of the Greek past and it was not until the time of Euhemerism that scholars began to question Homer's historicity.[57] As part of the Mycenaean heritage that survived, the names of the gods and goddesses of Mycenaean Greece (e.g. Zeus, Poseidon and Hades) became major figures of the Olympian Pantheon of later antiquity.[59]

Classical

The ethnogenesis of the Greek nation is linked to the development of Pan-Hellenism in the 8th century BC.[60] According to some scholars, the foundational event was the Olympic Games in 776 BC, when the idea of a common Hellenism among the Greek tribes was first translated into a shared cultural experience and Hellenism was primarily a matter of common culture.[35] The works of Homer (i.e. Iliad and Odyssey) and Hesiod (i.e. Theogony) were written in the 8th century BC, becoming the basis of the national religion, ethos, history and mythology.[61] The Oracle of Apollo at Delphi was established in this period.[62]

The classical period of Greek civilization covers a time spanning from the early 5th century BC to the death of Alexander the Great, in 323 BC (some authors prefer to split this period into "Classical", from the end of the Greco-Persian Wars to the end of the Peloponnesian War, and "Fourth Century", up to the death of Alexander). It is so named because it set the standards by which Greek civilization would be judged in later eras.[63] The Classical period is also described as the "Golden Age" of Greek civilization, and its art, philosophy, architecture and literature would be instrumental in the formation and development of Western culture.

While the Greeks of the classical era understood themselves to belong to a common Hellenic genos,[64] their first loyalty was to their city and they saw nothing incongruous about warring, often brutally, with other Greek city-states.[65] The Peloponnesian War, the large scale civil war between the two most powerful Greek city-states Athens and Sparta and their allies, left both greatly weakened.[66]

Most of the feuding Greek city-states were, in some scholars' opinions, united under the banner of Philip's and Alexander the Great's Pan-Hellenic ideals, though others might generally opt, rather, for an explanation of "Macedonian conquest for the sake of conquest" or at least conquest for the sake of riches, glory and power and view the "ideal" as useful propaganda directed towards the city-states.[67]

In any case, Alexander's toppling of the Achaemenid Empire, after his victories at the battles of the Granicus, Issus and Gaugamela, and his advance as far as modern-day Pakistan and Tajikistan,[68] provided an important outlet for Greek culture, via the creation of colonies and trade routes along the way.[69] While the Alexandrian empire did not survive its creator's death intact, the cultural implications of the spread of Hellenism across much of the Middle East and Asia were to prove long lived as Greek became the lingua franca, a position it retained even in Roman times.[70] Many Greeks settled in Hellenistic cities like Alexandria, Antioch and Seleucia.[71] Two thousand years later, there are still communities in Pakistan and Afghanistan, like the Kalash, who claim to be descended from Greek settlers.[72]

Hellenistic

The Hellenistic civilization was the next period of Greek civilization, the beginnings of which are usually placed at Alexander's death.[73] This Hellenistic age, so called because it saw the partial Hellenization of many non-Greek cultures,[74] lasted until the conquest of Egypt by Rome in 30 BC.[73]

This age saw the Greeks move towards larger cities and a reduction in the importance of the city-state. These larger cities were parts of the still larger Kingdoms of the Diadochi.[75][76] Greeks, however, remained aware of their past, chiefly through the study of the works of Homer and the classical authors.[77] An important factor in maintaining Greek identity was contact with barbarian (non-Greek) peoples, which was deepened in the new cosmopolitan environment of the multi-ethnic Hellenistic kingdoms.[77] This led to a strong desire among Greeks to organize the transmission of the Hellenic paideia to the next generation.[77] Greek science, technology and mathematics are generally considered to have reached their peak during the Hellenistic period.[78]

In the Indo-Greek and Greco-Bactrian kingdoms, Greco-Buddhism was spreading and Greek missionaries would play an important role in propagating it to China.[79] Further east, the Greeks of Alexandria Eschate became known to the Chinese people as the Dayuan.[80]

Roman Empire

Between 168 BC and 30 BC, the entire Greek world was conquered by Rome, and almost all of the world's Greek speakers lived as citizens or subjects of the Roman Empire. Despite their military superiority, the Romans admired and became heavily influenced by the achievements of Greek culture, hence Horace's famous statement: Graecia capta ferum victorem cepit ("Greece, although captured, took its wild conqueror captive").[81] In the centuries following the Roman conquest of the Greek world, the Greek and Roman cultures merged into a single Greco-Roman culture.

In the religious sphere, this was a period of profound change. The spiritual revolution that took place, saw a waning of the old Greek religion, whose decline beginning in the 3rd century BC continued with the introduction of new religious movements from the East.[35] The cults of deities like Isis and Mithra were introduced into the Greek world.[76][82] Greek-speaking communities of the Hellenized East were instrumental in the spread of early Christianity in the 2nd and 3rd centuries,[83] and Christianity's early leaders and writers (notably Saint Paul) were generally Greek-speaking,[84] though none were from Greece. However, Greece itself had a tendency to cling to paganism and was not one of the influential centers of early Christianity: in fact, some ancient Greek religious practices remained in vogue until the end of the 4th century,[85] with some areas such as the southeastern Peloponnese remaining pagan until well into the 10th century AD.[86]

While ethnic distinctions still existed in the Roman Empire, they became secondary to religious considerations and the renewed empire used Christianity as a tool to support its cohesion and promoted a robust Roman national identity.[87] From the early centuries of the Common Era, the Greeks self-identified as Romans (Greek: Ῥωμαῖοι Rhōmaîoi).[88] By that time, the name Hellenes denoted pagans but was revived as an ethnonym in the 11th century.[89]

Byzantine Empire

There are three schools of thought regarding this Byzantine Roman identity in contemporary Byzantine scholarship: The first considers "Romanity" the mode of self-identification of the subjects of a multi-ethnic empire at least up to the 12th century, where the average subject identified as Roman; a perennialist approach, which views Romanity as the medieval expression of a continuously existing Greek nation; while a third view considers the eastern Roman identity as a pre-modern national identity.[90] The Byzantine Greeks' essential values were drawn from both Christianity and the Homeric tradition of ancient Greece.[91][92] The Eastern Roman Empire (today conventionally named the Byzantine Empire, a name not used during its own time[93]) became increasingly influenced by Greek culture after the 7th century when Emperor Heraclius (r. 610–641 AD) decided to make Greek the empire's official language.[94][95] Although the Catholic Church recognized the Eastern Empire's claim to the Roman legacy for several centuries, after Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne, king of the Franks, as the "Roman Emperor" on 25 December 800, an act which eventually led to the formation of the Holy Roman Empire, the Latin West started to favour the Franks and began to refer to the Eastern Roman Empire largely as the Empire of the Greeks (Imperium Graecorum).[96][97] In the eastern Roman Empire the use of the Latinizing term Graikoí (Γραικοί, "Greeks") was uncommon and nonexistent in official Byzantine political correspondence, prior to the Fourth Crusade of 1204.[98] While this Latin term for the ancient Hellenes could be used neutrally, its use by Westerners from the 9th century onwards in order to challenge Byzantine claims to ancient Roman heritage rendered it a derogatory exonym for the Byzantines who barely used it, mostly in contexts relating to the West, such as texts relating to the Council of Florence, to present the Western viewpoint.[99][100]

A distinct Greek identity re-emerged in the 11th century in educated circles and became more forceful after the fall of Constantinople to the Crusaders of the Fourth Crusade in 1204.[101] In the Empire of Nicaea, a small circle of the elite used the term "Hellene" as a term of self-identification.[102] After the Byzantines recaptured Constantinople, however, in 1261, Rhomaioi became again dominant as a term for self-description and there are few traces of Hellene (Έλληνας), such as in the writings of George Gemistos Plethon,[103] who abandoned Christianity and in whose writings culminated the secular tendency in the interest in the classical past.[101] However, it was the combination of Orthodox Christianity with a specifically Greek identity that shaped the Greeks' notion of themselves in the empire's twilight years.[101] In the twilight years of the Byzantine Empire, prominent Byzantine personialities proposed referring to the Byzantine Emperor as the "Emperor of the Hellenes".[104][105] These largely rhetorical expressions of Hellenic identity were confined within intellectual circles, but were continued by Byzantine intellectuals who participated in the Italian Renaissance.[106] The interest in the Classical Greek heritage was complemented by a renewed emphasis on Greek Orthodox identity, which was reinforced in the late Medieval and Ottoman Greeks' links with their fellow Orthodox Christians in the Russian Empire. These were further strengthened following the fall of the Empire of Trebizond in 1461, after which and until the second Russo-Turkish War of 1828–29 hundreds of thousands of Pontic Greeks fled or migrated from the Pontic Alps and Armenian Highlands to southern Russia and the Russian South Caucasus (see also Greeks in Russia, Greeks in Armenia, Greeks in Georgia, and Caucasian Greeks).[107]

These Byzantine Greeks were largely responsible for the preservation of the literature of the classical era.[92][108][109] Byzantine grammarians were those principally responsible for carrying, in person and in writing, ancient Greek grammatical and literary studies to the West during the 15th century, giving the Italian Renaissance a major boost.[110][111] The Aristotelian philosophical tradition was nearly unbroken in the Greek world for almost two thousand years, until the Fall of Constantinople in 1453.[112]

To the Slavic world, the Byzantine Greeks contributed by the dissemination of literacy and Christianity. The most notable example of the later was the work of the two Byzantine Greek brothers, the monks Saints Cyril and Methodius from the port city of Thessalonica, capital of the theme of Thessalonica, who are credited today with formalizing the first Slavic alphabet.[113]

Ottoman Empire

Following the Fall of Constantinople on 29 May 1453, many Greeks sought better employment and education opportunities by leaving for the West, particularly Italy, Central Europe, Germany and Russia.[110] Greeks are greatly credited for the European cultural revolution, later called, the Renaissance. In Greek-inhabited territory itself, Greeks came to play a leading role in the Ottoman Empire, due in part to the fact that the central hub of the empire, politically, culturally, and socially, was based on Western Thrace and Greek Macedonia, both in Northern Greece, and of course was centred on the mainly Greek-populated, former Byzantine capital, Constantinople. As a direct consequence of this situation, Greek-speakers came to play a hugely important role in the Ottoman trading and diplomatic establishment, as well as in the church. Added to this, in the first half of the Ottoman period men of Greek origin made up a significant proportion of the Ottoman army, navy, and state bureaucracy, having been levied as adolescents (along with especially Albanians and Serbs) into Ottoman service through the devshirme. Many Ottomans of Greek (or Albanian or Serb) origin were therefore to be found within the Ottoman forces which governed the provinces, from Ottoman Egypt, to Ottomans occupied Yemen and Algeria, frequently as provincial governors.

For those that remained under the Ottoman Empire's millet system, religion was the defining characteristic of national groups (milletler), so the exonym "Greeks" (Rumlar from the name Rhomaioi) was applied by the Ottomans to all members of the Orthodox Church, regardless of their language or ethnic origin.[114] The Greek speakers were the only ethnic group to actually call themselves Romioi,[115] (as opposed to being so named by others) and, at least those educated, considered their ethnicity (genos) to be Hellenic.[116] There were, however, many Greeks who escaped the second-class status of Christians inherent in the Ottoman millet system, according to which Muslims were explicitly awarded senior status and preferential treatment. These Greeks either emigrated, particularly to their fellow Greek Orthodox protector, the Russian Empire, or simply converted to Islam, often only very superficially and whilst remaining crypto-Christian. The most notable examples of large-scale conversion to Turkish Islam among those today defined as Greek Muslims—excluding those who had to convert as a matter of course on being recruited through the devshirme—were to be found in Crete (Cretan Turks), Greek Macedonia (for example among the Vallahades of western Macedonia), and among Pontic Greeks in the Pontic Alps and Armenian Highlands. Several Ottoman sultans and princes were also of part Greek origin, with mothers who were either Greek concubines or princesses from Byzantine noble families, one famous example being sultan Selim the Grim (r. 1517–1520), whose mother Gülbahar Hatun was a Pontic Greek.

The roots of Greek success in the Ottoman Empire can be traced to the Greek tradition of education and commerce exemplified in the Phanariotes.[117] It was the wealth of the extensive merchant class that provided the material basis for the intellectual revival that was the prominent feature of Greek life in the half century and more leading to the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence in 1821.[118] Not coincidentally, on the eve of 1821, the three most important centres of Greek learning were situated in Chios, Smyrna and Aivali, all three major centres of Greek commerce.[118] Greek success was also favoured by Greek domination of the Eastern Orthodox church.

Modern

The relationship between ethnic Greek identity and Greek Orthodox religion continued after the creation of the modern Greek nation-state in 1830. According to the second article of the first Greek constitution of 1822, a Greek was defined as any native Christian resident of the Kingdom of Greece, a clause removed by 1840.[119] A century later, when the Treaty of Lausanne was signed between Greece and Turkey in 1923, the two countries agreed to use religion as the determinant for ethnic identity for the purposes of population exchange, although most of the Greeks displaced (over a million of the total 1.5 million) had already been driven out by the time the agreement was signed.[note 2][120] The Greek genocide, in particular the harsh removal of Pontian Greeks from the southern shore area of the Black Sea, contemporaneous with and following the failed Greek Asia Minor Campaign, was part of this process of Turkification of the Ottoman Empire and the placement of its economy and trade, then largely in Greek hands under ethnic Turkish control.[121]

Identity

The terms used to define Greekness have varied throughout history but were never limited or completely identified with membership to a Greek state.[122] Herodotus gave a famous account of what defined Greek (Hellenic) ethnic identity in his day, enumerating

- shared descent (ὅμαιμον - homaimon, "of the same blood"),[123]

- shared language (ὁμόγλωσσον - homoglōsson, "speaking the same language")[124]

- shared sanctuaries and sacrifices (Greek: θεῶν ἱδρύματά τε κοινὰ καὶ θυσίαι - theōn hidrumata te koina kai thusiai)[125]

- shared customs (Greek: ἤθεα ὁμότροπα - ēthea homotropa, "customs of like fashion").[126][127][128]

By Western standards, the term Greeks has traditionally referred to any native speakers of the Greek language, whether Mycenaean, Byzantine or modern Greek.[114][129] Byzantine Greeks self-identified as Romaioi ("Romans"), Graikoi ("Greeks") and Christianoi ("Christians") since they were the political heirs of imperial Rome, the descendants of their classical Greek forebears and followers of the Apostles;[130] during the mid-to-late Byzantine period (11th–13th century), a growing number of Byzantine Greek intellectuals deemed themselves Hellenes although for most Greek-speakers, "Hellene" still meant pagan.[89][131] On the eve of the Fall of Constantinople the Last Emperor urged his soldiers to remember that they were the descendants of Greeks and Romans.[132]

Before the establishment of the modern Greek nation-state, the link between ancient and modern Greeks was emphasized by the scholars of Greek Enlightenment especially by Rigas Feraios. In his "Political Constitution", he addresses to the nation as "the people descendant of the Greeks".[133] The modern Greek state was created in 1829, when the Greeks liberated a part of their historic homelands, Peloponnese, from the Ottoman Empire.[134] The large Greek diaspora and merchant class were instrumental in transmitting the ideas of western romantic nationalism and philhellenism,[118] which together with the conception of Hellenism, formulated during the last centuries of the Byzantine Empire, formed the basis of the Diafotismos and the current conception of Hellenism.[101][114][135]

The Greeks today are a nation in the meaning of an ethnos, defined by possessing Greek culture and having a Greek mother tongue, not by citizenship, race, and religion or by being subjects of any particular state.[136] In ancient and medieval times and to a lesser extent today the Greek term was genos, which also indicates a common ancestry.[137][138]

Names

Greeks and Greek-speakers have used different names to refer to themselves collectively. The term Achaeans (Ἀχαιοί) is one of the collective names for the Greeks in Homer's Iliad and Odyssey (the Homeric "long-haired Achaeans" would have been a part of the Mycenaean civilization that dominated Greece from c. 1600 BC until 1100 BC). The other common names are Danaans (Δαναοί) and Argives (Ἀργεῖοι) while Panhellenes (Πανέλληνες) and Hellenes (Ἕλληνες) both appear only once in the Iliad;[139] all of these terms were used, synonymously, to denote a common Greek identity.[140][141] In the historical period, Herodotus identified the Achaeans of the northern Peloponnese as descendants of the earlier, Homeric Achaeans.[142]

Homer refers to the "Hellenes" (/ˈhɛliːnz/) as a relatively small tribe settled in Thessalic Phthia, with its warriors under the command of Achilleus.[143] The Parian Chronicle says that Phthia was the homeland of the Hellenes and that this name was given to those previously called Greeks (Γραικοί).[144] In Greek mythology, Hellen, the patriarch of the Hellenes who ruled around Phthia, was the son of Pyrrha and Deucalion, the only survivors after the Great Deluge.[145] The Greek philosopher Aristotle names ancient Hellas as an area in Epirus between Dodona and the Achelous river, the location of the Great Deluge of Deucalion, a land occupied by the Selloi and the "Greeks" who later came to be known as "Hellenes".[146] In the Homeric tradition, the Selloi were the priests of Dodonian Zeus.[147]

In the Hesiodic Catalogue of Women, Graecus is presented as the son of Zeus and Pandora II, sister of Hellen the patriarch of the Hellenes.[148] According to the Parian Chronicle, when Deucalion became king of Phthia, the Graikoi (Γραικοί) were named Hellenes.[144] Aristotle notes in his Meteorologica that the Hellenes were related to the Graikoi.[146]

Continuity

The most obvious link between modern and ancient Greeks is their language, which has a documented tradition from at least the 14th century BC to the present day, albeit with a break during the Greek Dark Ages (11th- 8th cent. BC, though the Cypriot syllabary was in use during this period).[149] Scholars compare its continuity of tradition to Chinese alone.[149][150] Since its inception, Hellenism was primarily a matter of common culture and the national continuity of the Greek world is a lot more certain than its demographic.[35][151] Yet, Hellenism also embodied an ancestral dimension through aspects of Athenian literature that developed and influenced ideas of descent based on autochthony.[152] During the later years of the Eastern Roman Empire, areas such as Ionia and Constantinople experienced a Hellenic revival in language, philosophy, and literature and on classical models of thought and scholarship.[151] This revival provided a powerful impetus to the sense of cultural affinity with ancient Greece and its classical heritage.[151] Throughout their history, the Greeks have retained their language and alphabet, certain values and cultural traditions, customs, a sense of religious and cultural difference and exclusion (the word barbarian was used by 12th-century historian Anna Komnene to describe non-Greek speakers),[153] a sense of Greek identity and common sense of ethnicity despite the undeniable socio-political changes of the past two millennia.[151] In recent anthropological studies, both ancient and modern Greek osteological samples were analyzed demonstrating a bio-genetic affinity and continuity shared between both groups.[154][155]

Demographics

Today, Greeks are the majority ethnic group in the Hellenic Republic,[156] where they constitute 93% of the country's population,[157] and the Republic of Cyprus where they make up 78% of the island's population (excluding Turkish settlers in the occupied part of the country).[158] Greek populations have not traditionally exhibited high rates of growth; a large percentage of Greek population growth since Greece's foundation in 1832 was attributed to annexation of new territories, as well as the influx of 1.5 million Greek refugees after the 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey.[159] About 80% of the population of Greece is urban, with 28% concentrated in the city of Athens.[160]

Greeks from Cyprus have a similar history of emigration, usually to the English-speaking world because of the island's colonization by the British Empire. Waves of emigration followed the Turkish invasion of Cyprus in 1974, while the population decreased between mid-1974 and 1977 as a result of emigration, war losses, and a temporary decline in fertility.[161] After the ethnic cleansing of a third of the Greek population of the island in 1974,[162][163] there was also an increase in the number of Greek Cypriots leaving, especially for the Middle East, which contributed to a decrease in population that tapered off in the 1990s.[161] Today more than two-thirds of the Greek population in Cyprus is urban.[161]

There is a sizeable Greek minority of approximately 200,000 people in Albania.[14] The Greek minority of Turkey, which numbered upwards of 200,000 people after the 1923 exchange, has now dwindled to a few thousand, after the 1955 Constantinople Pogrom and other state sponsored violence and discrimination.[164] This effectively ended, though not entirely, the three-thousand-year-old presence of Hellenism in Asia Minor.[165][166] There are smaller Greek minorities in the rest of the Balkan countries, the Levant and the Black Sea states, remnants of the Old Greek Diaspora (pre-19th century).[167]

Diaspora

The total number of Greeks living outside Greece and Cyprus today is a contentious issue. Where Census figures are available, they show around 3 million Greeks outside Greece and Cyprus. Estimates provided by the SAE - World Council of Hellenes Abroad put the figure at around 7 million worldwide.[168] According to George Prevelakis of Sorbonne University, the number is closer to just below 5 million.[167] Integration, intermarriage, and loss of the Greek language influence the self-identification of the Omogeneia. Important centres of the New Greek Diaspora today are London, New York, Melbourne and Toronto.[167] In 2010, the Hellenic Parliament introduced a law that enables Diaspora Greeks in Greece to vote in the elections of the Greek state.[169] This law was later repealed in early 2014.[170]

Ancient

In ancient times, the trading and colonizing activities of the Greek tribes and city states spread the Greek culture, religion and language around the Mediterranean and Black Sea basins, especially in Sicily and southern Italy (also known as Magna Grecia), Spain, the south of France and the Black sea coasts.[171] Under Alexander the Great's empire and successor states, Greek and Hellenizing ruling classes were established in the Middle East, India and in Egypt.[171] The Hellenistic period is characterized by a new wave of Greek colonization that established Greek cities and kingdoms in Asia and Africa.[172] Under the Roman Empire, easier movement of people spread Greeks across the Empire and in the eastern territories, Greek became the lingua franca rather than Latin.[94] The modern-day Griko community of southern Italy, numbering about 60,000,[18][19] may represent a living remnant of the ancient Greek populations of Italy.

Modern

During and after the Greek War of Independence, Greeks of the diaspora were important in establishing the fledgling state, raising funds and awareness abroad.[173] Greek merchant families already had contacts in other countries and during the disturbances many set up home around the Mediterranean (notably Marseilles in France, Livorno in Italy, Alexandria in Egypt), Russia (Odessa and Saint Petersburg), and Britain (London and Liverpool) from where they traded, typically in textiles and grain.[174] Businesses frequently comprised the extended family, and with them they brought schools teaching Greek and the Greek Orthodox Church.[174]

As markets changed and they became more established, some families grew their operations to become shippers, financed through the local Greek community, notably with the aid of the Ralli or Vagliano Brothers.[175] With economic success, the Diaspora expanded further across the Levant, North Africa, India and the USA.[175][176]

In the 20th century, many Greeks left their traditional homelands for economic reasons resulting in large migrations from Greece and Cyprus to the United States, Great Britain, Australia, Canada, Germany, and South Africa, especially after the Second World War (1939–1945), the Greek Civil War (1946–1949), and the Turkish Invasion of Cyprus in 1974.[177]

While official figures remain scarce, polls and anecdotal evidence point to renewed Greek emigration as a result of the Greek financial crisis.[178] According to data published by the Federal Statistical Office of Germany in 2011, 23,800 Greeks emigrated to Germany, a significant increase over the previous year. By comparison, about 9,000 Greeks emigrated to Germany in 2009 and 12,000 in 2010.[179][180]

Culture

Greek culture has evolved over thousands of years, with its beginning in the Mycenaean civilization, continuing through the classical era, the Hellenistic period, the Roman and Byzantine periods and was profoundly affected by Christianity, which it in turn influenced and shaped.[181] Ottoman Greeks had to endure through several centuries of adversity that culminated in genocide in the 20th century.[182][183] The Diafotismos is credited with revitalizing Greek culture and giving birth to the synthesis of ancient and medieval elements that characterize it today.[101][114]

Language

Most Greeks speak the Greek language, an independent branch of the Indo-European languages, with its closest relations possibly being Armenian (see Graeco-Armenian) or the Indo-Iranian languages (see Graeco-Aryan).[149] It has the longest documented history of any living language and Greek literature has a continuous history of over 2,500 years.[184] The oldest inscriptions in Greek are in the Linear B script, dated as far back as 1450 BC.[185] Following the Greek Dark Ages, from which written records are absent, the Greek alphabet appears in the 9th-8th century BC. The Greek alphabet derived from the Phoenician alphabet, but is considered the first true alphabet as it is the first to have explicit symbols for vowels.[186] The Greek alphabet in turn is the parent alphabet of the Latin, Cyrillic, and several other alphabets. The earliest Greek literary works are the Homeric epics, variously dated from the 8th to the 6th century BC. Notable scientific and mathematical works include Euclid's Elements, Ptolemy's Almagest, and others. The New Testament was originally written in Koine Greek.

Greek demonstrates several linguistic features that are shared with other Balkan languages, such as Albanian, Bulgarian and Eastern Romance languages (see Balkan sprachbund), and has absorbed many foreign words, primarily of Western European and Turkish origin.[187] Because of the movements of Philhellenism and the Diafotismos in the 19th century, which emphasized the modern Greeks' ancient heritage, these foreign influences were excluded from official use via the creation of Katharevousa, a somewhat artificial form of Greek purged of all foreign influence and words, as the official language of the Greek state. In 1976, however, the Hellenic Parliament voted to make the spoken Dimotiki the official language, making Katharevousa obsolete.[188]

Modern Greek has, in addition to Standard Modern Greek or Dimotiki, a wide variety of dialects of varying levels of mutual intelligibility, including Cypriot, Pontic, Cappadocian, Griko and Tsakonian (the only surviving representative of ancient Doric Greek).[189] Yevanic is the language of the Romaniotes, and survives in small communities in Greece, New York and Israel. In addition to Greek, many Greeks in Greece and the Diaspora are bilingual in other languages or dialects such as English, Arvanitika/Albanian, Aromanian, Macedonian Slavic, Russian and Turkish.[149][190]

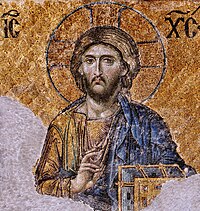

Religion

Most Greeks are Christians, belonging to the Greek Orthodox Church.[191] During the first centuries after Jesus Christ, the New Testament was originally written in Koine Greek, which remains the liturgical language of the Greek Orthodox Church, and most of the early Christians and Church Fathers were Greek-speaking.[181] There are small groups of ethnic Greeks adhering to other Christian denominations like Greek Catholics, Greek Evangelicals, Pentecostals, and groups adhering to other religions including Romaniot and Sephardic Jews and Greek Muslims. About 2,000 Greeks are members of Hellenic Polytheistic Reconstructionism congregations.[192][193][194]

Greek-speaking Muslims live mainly outside Greece in the contemporary era. There are both Christian and Muslim Greek-speaking communities in Lebanon and Syria, while in the Pontus region of Turkey there is a large community of indeterminate size who were spared from the population exchange because of their religious affiliation.[195]

Arts

Greek art has a long and varied history. Greeks have contributed to the visual, literary and performing arts.[196] In the West, classical Greek art was influential in shaping the Roman and later the modern Western artistic heritage. Following the Renaissance in Europe, the humanist aesthetic and the high technical standards of Greek art inspired generations of European artists.[196] Well into the 19th century, the classical tradition derived from Greece played an important role in the art of the Western world.[197] In the East, Alexander the Great's conquests initiated several centuries of exchange between Greek, Central Asian and Indian cultures, resulting in Greco-Buddhist art, whose influence reached as far as Japan.[198]

Byzantine Greek art, which grew from classical art and adapted the pagan motifs in the service of Christianity, provided a stimulus to the art of many nations.[199] Its influences can be traced from Venice in the West to Kazakhstan in the East.[199][200] In turn, Greek art was influenced by eastern civilizations (i.e. Egypt, Persia, etc.) during various periods of its history.[201]

Notable modern Greek artists include Renaissance painter Dominikos Theotokopoulos (El Greco), Panagiotis Doxaras, Nikolaos Gyzis, Nikiphoros Lytras, Yannis Tsarouchis, Nikos Engonopoulos, Constantine Andreou, Jannis Kounellis, sculptors such as Leonidas Drosis, Georgios Bonanos, Yannoulis Chalepas and Joannis Avramidis, conductor Dimitri Mitropoulos, soprano Maria Callas, composers such as Mikis Theodorakis, Nikos Skalkottas, Iannis Xenakis, Manos Hatzidakis, Eleni Karaindrou, Yanni and Vangelis, one of the best-selling singers worldwide Nana Mouskouri and poets such as Kostis Palamas, Dionysios Solomos, Angelos Sikelianos and Yannis Ritsos. Alexandrian Constantine P. Cavafy and Nobel laureates Giorgos Seferis and Odysseas Elytis are among the most important poets of the 20th century. Novel is also represented by Alexandros Papadiamantis and Nikos Kazantzakis.

Notable Greek actors include Marika Kotopouli, Melina Mercouri, Ellie Lambeti, Academy Award winner Katina Paxinou, Dimitris Horn, Manos Katrakis and Irene Papas. Alekos Sakellarios, Michael Cacoyannis and Theo Angelopoulos are among the most important directors.

Science

The Greeks of the Classical and Hellenistic eras made seminal contributions to science and philosophy, laying the foundations of several western scientific traditions, such as astronomy, geography, historiography, mathematics, medicine and philosophy. The scholarly tradition of the Greek academies was maintained during Roman times with several academic institutions in Constantinople, Antioch, Alexandria and other centers of Greek learning, while Byzantine science was essentially a continuation of classical science.[202] Greeks have a long tradition of valuing and investing in paideia (education).[77] Paideia was one of the highest societal values in the Greek and Hellenistic world while the first European institution described as a university was founded in 5th century Constantinople and operated in various incarnations until the city's fall to the Ottomans in 1453.[203] The University of Constantinople was Christian Europe's first secular institution of higher learning since no theological subjects were taught,[204] and considering the original meaning of the world university as a corporation of students, the world's first university as well.[203]

As of 2007, Greece had the eighth highest percentage of tertiary enrollment in the world (with the percentages for female students being higher than for male) while Greeks of the Diaspora are equally active in the field of education.[160] Hundreds of thousands of Greek students attend western universities every year while the faculty lists of leading Western universities contain a striking number of Greek names.[205] Notable modern Greek scientists of modern times include Dimitrios Galanos, Georgios Papanikolaou (inventor of the Pap test), Nicholas Negroponte, Constantin Carathéodory, Manolis Andronikos, Michael Dertouzos, John Argyris, Panagiotis Kondylis, John Iliopoulos (2007 Dirac Prize for his contributions on the physics of the charm quark, a major contribution to the birth of the Standard Model, the modern theory of Elementary Particles), Joseph Sifakis (2007 Turing Award, the "Nobel Prize" of Computer Science), Christos Papadimitriou (2002 Knuth Prize, 2012 Gödel Prize), Mihalis Yannakakis (2005 Knuth Prize) and Dimitri Nanopoulos.

Symbols

The most widely used symbol is the flag of Greece, which features nine equal horizontal stripes of blue alternating with white representing the nine syllables of the Greek national motto Eleftheria i Thanatos (Freedom or Death), which was the motto of the Greek War of Independence.[206] The blue square in the upper hoist-side corner bears a white cross, which represents Greek Orthodoxy. The Greek flag is widely used by the Greek Cypriots, although Cyprus has officially adopted a neutral flag to ease ethnic tensions with the Turkish Cypriot minority (see flag of Cyprus).[207]

The pre-1978 (and first) flag of Greece, which features a Greek cross (crux immissa quadrata) on a blue background, is widely used as an alternative to the official flag, and they are often flown together. The national emblem of Greece features a blue escutcheon with a white cross surrounded by two laurel branches. A common design involves the current flag of Greece and the pre-1978 flag of Greece with crossed flagpoles and the national emblem placed in front.[208]

Another highly recognizable and popular Greek symbol is the double-headed eagle, the imperial emblem of the last dynasty of the Eastern Roman Empire and a common symbol in Asia Minor and, later, Eastern Europe.[209] It is not part of the modern Greek flag or coat-of-arms, although it is officially the insignia of the Greek Army and the flag of the Church of Greece. It had been incorporated in the Greek coat of arms between 1925 and 1926.[210]

Surnames and personal names

Greek surnames began to appear in the 9th and 10th century, at first among ruling families, eventually supplanting the ancient tradition of using the father's name as disambiguator.[211][212] Nevertheless, Greek surnames are most commonly patronymics,[211] such those ending in the suffix -opoulos or -ides, while others derive from trade professions, physical characteristics, or a location such as a town, village, or monastery.[212] Commonly, Greek male surnames end in -s, which is the common ending for Greek masculine proper nouns in the nominative case. Occasionally (especially in Cyprus), some surnames end in -ou, indicating the genitive case of a patronymic name.[213] Many surnames end in suffixes that are associated with a particular region, such as -akis (Crete), -eas or -akos (Mani Peninsula), -atos (island of Cephalonia), and so forth.[212] In addition to a Greek origin, some surnames have Turkish or Latin/Italian origin, especially among Greeks from Asia Minor and the Ionian Islands, respectively.[214] Female surnames end in a vowel and are usually the genitive form of the corresponding males surname, although this usage is not followed in the diaspora, where the male version of the surname is generally used.

With respect to personal names, the two main influences are Christianity and classical Hellenism; ancient Greek nomenclatures were never forgotten but have become more widely bestowed from the 18th century onwards.[212] As in antiquity, children are customarily named after their grandparents, with the first born male child named after the paternal grandfather, the second male child after the maternal grandfather, and similarly for female children.[215] Personal names are often familiarized by a diminutive suffix, such as -akis for male names and -itsa or -oula for female names.[212] Greeks generally do not use middle names, instead using the genitive of the father's first name as a middle name. This usage has been passed on to the Russians and other East Slavs (otchestvo).

Sea

The traditional Greek homelands have been the Greek peninsula and the Aegean Sea, Southern Italy (Magna Graecia), the Black Sea, the Ionian coasts of Asia Minor and the islands of Cyprus and Sicily. In Plato's Phaidon, Socrates remarks, "we (Greeks) live around a sea like frogs around a pond" when describing to his friends the Greek cities of the Aegean.[216][217] This image is attested by the map of the Old Greek Diaspora, which corresponded to the Greek world until the creation of the Greek state in 1832. The sea and trade were natural outlets for Greeks since the Greek peninsula is rocky and does not offer good prospects for agriculture.[35]

Notable Greek seafarers include people such as Pytheas of Marseilles, Scylax of Caryanda who sailed to Iberia and beyond, Nearchus, the 6th century merchant and later monk Cosmas Indicopleustes (Cosmas who Sailed to India) and the explorer of the Northwestern Passage, Apostolos Valerianos also known as Juan de Fuca.[218] In later times, the Byzantine Greeks plied the sea-lanes of the Mediterranean and controlled trade until an embargo imposed by the Byzantine emperor on trade with the Caliphate opened the door for the later Italian pre-eminence in trade.[219]

The Greek shipping tradition recovered during Ottoman rule when a substantial merchant middle class developed, which played an important part in the Greek War of Independence.[101] Today, Greek shipping continues to prosper to the extent that Greece has the largest merchant fleet in the world, while many more ships under Greek ownership fly flags of convenience.[160] The most notable shipping magnate of the 20th century was Aristotle Onassis, others being Yiannis Latsis, George Livanos, and Stavros Niarchos.[220][221]

Genetics

Genetic studies using multiple autosomal gene markers, Y chromosomal DNA haplogroup analysis and mitochondrial gene markers (mtDNA) show that Greeks share similar backgrounds as the rest of the Europeans and especially southern Europeans (Italians and southern Balkan populations). According to the studies using multiple autosomal gene markers, Greeks are some of the earliest contributors of genetic material to the rest of the Europeans as they are one of the oldest populations in Europe.[222] A study in 2008 showed that Greeks are genetically closest to Italians and Romanians[223] and another 2008 study showed that they are close to Italians, Albanians, Romanians and southern Balkan Slavs.[224] A 2003 study showed that Greeks cluster with other South European (mainly Italians) and North-European populations and are close to the Basques,[225] and FST distances showed that they group with other European and Mediterranean populations,[222][226] especially with Italians (−0.0001) and Tuscans (0.0005).[227] A 2017 study showed that Southern Italian populations appear genetically closer to Greek islands than to continental Greece.[228]

Y DNA studies show that Greeks cluster with other Europeans[229][230][231][232][233] and that they carry some of the oldest Y haplogroups in Europe, in particular the J2 haplogroup (and other J subhaplogroups) and E haplogroups, which are genetic markers denoting early farmers.[229][233][234][235] The Y-chromosome lineage E-V13 appears to have originated in Greece or the southern Balkans and is high in Greeks as well as in Albanians, southern Italians and southern Slavs. E-V13 is also found in Corsicans and Provencals, where an admixture analysis estimated that 17% of the Y-chromosomes of Provence may be attributed to Greek colonization, and is also found at low frequencies on the Anatolian mainland. These results suggest that E-V13 may trace the demographic and socio-cultural impact of Greek colonization in Mediterranean Europe, a contribution that appears to be considerably larger than that of a Neolithic pioneer colonization.[236][237][238] A study in 2008 showed that Greek regional samples from the mainland cluster with those from the Balkans while Cretan Greeks cluster with the central Mediterranean and Eastern Mediterranean samples.[230] Greek signature DNA influence can be seen in Southern Italy and Sicily, where the genetic contribution of Greek chromosomes to the Sicilian gene pool is estimated to be about 37%, and the Southern Balkans.[233][234]

Studies using mitochondrial DNA gene markers (mtDNA) showed that Greeks group with other Mediterranean European populations[239][240][241] and principal component analysis (PCA) confirmed the low genetic distance between Greeks and Italians[242] and also revealed a cline of genes with highest frequencies in the Balkans and Southern Italy, spreading to lowest levels in Britain and the Basque country, which Cavalli-Sforza associates it with "the Greek expansion, which reached its peak in historical times around 1000 and 500 BC but which certainly began earlier".[243]

A 2017 study on the genetic origins of the Minoans and Mycenaeans showed that modern Greeks resemble the Mycenaeans, but with some additional dilution of the early neolithic ancestry. The results of the study support the idea of genetic continuity between these civilizations and modern Greeks but not isolation in the history of populations of the Aegean, before and after the time of its earliest civilizations.[244][245][246] In an interview, the study's author, Harvard University geneticist Iosif Lazaridis, precised "that all three Bronze Age groups (Minoans, Mycenaeans, and Bronze Age southwestern Anatolians) trace most of their ancestry from the earlier Neolithic populations that were very similar in Greece and western Anatolia. But, they also had some ancestry from the 'east', related to populations of the Caucasus and Iran" as well as "some ancestry from the "north", related to hunter-gatherers of eastern Europe and Siberia and also to the Bronze Age people of the steppe", and argues that "some had theorized that the Minoan and Mycenaean civilizations were influenced both culturally and genetically by the old civilizations of the Levant and Egypt, but there is no quantifiable genetic influence".[247]

Physical appearance

A study from 2013 for prediction of hair and eye colour from DNA of the Greek people showed that the self-reported phenotype frequencies according to hair and eye colour categories was as follows: 119 individuals – hair colour, 11 blond, 45 dark blond/light brown, 49 dark brown, 3 brown red/auburn and 11 had black hair; eye colour, 13 with blue, 15 with intermediate (green, heterochromia) and 91 had brown eye colour.[248]

Another study from 2012 included 150 dental school students from the University of Athens, and the results of the study showed that light hair colour (blonde/light ash brown) was predominant in 10.7% of the students. 36% had medium hair colour (light brown/medium darkest brown), 32% had darkest brown and 21% black (15.3 off black, 6% midnight black). In conclusion, the hair colour of young Greeks are mostly brown, ranging from light to dark brown with significant minorities having black and blonde hair. The same study also showed that the eye colour of the students was 14.6% blue/green, 28% medium (light brown) and 57.4% dark brown.[249]

Timeline

The history of the Greek people is closely associated with the history of Greece, Cyprus, Constantinople, Asia Minor and the Black Sea. During the Ottoman rule of Greece, a number of Greek enclaves around the Mediterranean were cut off from the core, notably in Southern Italy, the Caucasus, Syria and Egypt. By the early 20th century, over half of the overall Greek-speaking population was settled in Asia Minor (now Turkey), while later that century a huge wave of migration to the United States, Australia, Canada and elsewhere created the modern Greek diaspora.

|

|

See also

|

|

Notes

- ^ Though there is a range of interpretations; Carl Blegen dates the arrival of the Greeks around 1900 BC, John Caskey believes that there were two waves of immigrants and Robert Drews places the event as late as 1600 BC.[45][46] A variety of more theories has also been supported,[47] but there is a general consensus that the coming of the Greek tribes occurred around 2100 BC.

- ^ While Greek authorities signed the agreement legalizing the population exchange this was done on the insistence of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk and after a million Greeks had already been expelled from Asia Minor (Gilbar 1997, p. 8).

Citations

- ^ Maratou-Alipranti 2013, p. 196: "The Greek diaspora remains large, consisting of up to 4 million people globally."

- ^ Clogg 2013, p. 228: "Greeks of the diaspora, settled in some 141 countries, were held to number 7 million although it is not clear how this figure was arrived at or what criteria were used to define Greek ethnicity, while the population of the homeland, according to the 1991 census, amounted to some 10.25 million."

- ^ "2011 Population and Housing Census" (PDF). Hellenic Statistical Authority. 12 September 2014.

The Resident Population of Greece is 10.816.286, of which 5.303.223 male (49,0%) and 5.513.063 female (51,0%) ... The total number of permanent residents of Greece with foreign citizenship during the Census was 912.000. [See Graph 6: Resident Population by Citizenship]

- ^ "Statistical Data on Immigrants in Greece: An Analytic Study of Available Data and Recommendations for Conformity with European Union Standards" (PDF). Archive of European Integration (AEI). University of Pittsburgh. 15 November 2004. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

[p. 5] The Census recorded 762.191 persons normally resident in Greece and without Greek citizenship, constituting around 7% of total population. Of these, 48.560 are EU or EFTA nationals; there are also 17.426 Cypriots with privileged status.

- ^ "Total ancestry categories tallied for people with one or more ancestry categories reported 2011–2013 American Community Survey 3-Year Estimates". American FactFinder. U.S. Department of Commerce: United States Census Bureau. 2013.

- ^ "U.S. Relations with Greece". United States Department of State. 10 March 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

Today, an estimated three million Americans resident in the United States claim Greek descent. This large, well-organized community cultivates close political and cultural ties with Greece.

- ^ Statistical Service (2003–2016). "Preliminary Results of the Census of Population, 2011". Republic of Cyprus, Ministry of Finance, Statistical Service.

- ^ Cole 2011, Yiannis Papadakis, "Cypriots, Greek", pp. 92–95

- ^ "Where are the Greek communities of the world?". themanews.com. Protothemanews.com. 2013.

- ^ "Statistical Yearbook Germany Extract Chapter 2: Population, Families and Living Arrangements in Germany". Statistisches Bundesamt. 14 March 2013. p. 21.

- ^ "2071.0 - Reflecting a Nation: Stories from the 2011 Census, 2012–2013". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 21 June 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- ^ "United Kingdom: Cultural Relations and Greek Community". Hellenic Republic: Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 9 July 2013.

There are between 40 and 45 thousand Greeks residing permanently in the UK, and the Greek Orthodox Church has a strong presence in the Archdiocese of Thyateira and Great Britain ... There is a significant Greek presence of Greek students in tertiary education in the UK. A large Cypriot community – numbering 250–300 thousand – rallies round the National Federation of Cypriots in Great Britain and the Association of Greek Orthodox Communities of Great Britain.

- ^ "Ethnic Origin (264), Single and Multiple Ethnic Origin Responses (3), Generation Status (4), Age Groups (10) and Sex (3) for the Population in Private Households of Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2011 National Household Survey". Statistics Canada. 8 May 2013. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ^ a b Jeffries 2002, p. 69: "It is difficult to know how many ethnic Greeks there are in Albania. The Greek government, it is typically claimed, says there are around 300,000 ethnic Greeks in Albania, but most Western estimates are around the 200,000 mark ..."

- ^ "Ukraine: Cultural Relations and Greek Community". Hellenic Republic: Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 4 February 2011.

There is a significant Greek presence in southern and eastern Ukraine, which can be traced back to ancient Greek and Byzantine settlers. Ukrainian citizens of Greek descent amount to 91,000 people, although their number is estimated to be much higher by the Federation of Greek communities of Mariupol.

- ^ "Итоги Всероссийской переписи населения 2010 года в отношении демографических и социально-экономических характеристик отдельных национальностей".

- ^ "Italy: Cultural Relations and Greek Community". Hellenic Republic: Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 9 July 2013.

The Greek Italian community numbers some 30,000 and is concentrated mainly in central Italy. The age-old presence in Italy of Italians of Greek descent – dating back to Byzantine and Classical times – is attested to by the Griko dialect, which is still spoken in the Magna Graecia region. This historically Greek-speaking villages are Condofuri, Galliciano, Roccaforte del Greco, Roghudi, Bova and Bova Marina, which are in the Calabria region (the capital of which is Reggio). The Grecanic region, including Reggio, has a population of some 200,000, while speakers of the Griko dialect number fewer that 1,000 persons.

- ^ a b "Grecia Salentina" (in Italian). Unione dei Comuni della Grecìa Salentina. 2016.

La popolazione complessiva dell'Unione è di 54278 residenti così distribuiti (Dati Istat al 31° dicembre 2005. Comune Popolazione Calimera 7351 Carpignano Salentino 3868 Castrignano dei Greci 4164 Corigliano d'Otranto 5762 Cutrofiano 9250 Martano 9588 Martignano 1784 Melpignano 2234 Soleto 5551 Sternatia 2583 Zollino 2143 Totale 54278).

- ^ a b Bellinello 1998, p. 53: "Le attuali colonie Greche calabresi; La Grecìa calabrese si inscrive nel massiccio aspromontano e si concentra nell'ampia e frastagliata valle dell'Amendolea e nelle balze più a oriente, dove sorgono le fiumare dette di S. Pasquale, di Palizzi e Sidèroni e che costituiscono la Bovesia vera e propria. Compresa nei territori di cinque comuni (Bova Superiore, Bova Marina, Roccaforte del Greco, Roghudi, Condofuri), la Grecia si estende per circa 233 kmq. La popolazione anagrafica complessiva è di circa 14.000 unità."

- ^ "The Greek Community". Archived from the original on 13 June 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "South Africa: Cultural Relations and Greek Community". Hellenic Republic: Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 4 February 2011.

It is difficult to determine the precise number of Greeks due to constant comings and goings, although the estimated figure is above 45,000.

- ^ "France: Cultural Relations and Greek Community". Hellenic Republic: Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 9 July 2013.

Some 15,000 Greeks reside in the wider region of Paris, Lille and Lyon. In the region of Southern France, the Greek community numbers some 20,000.

- ^ "Belgium: Cultural Relations and Greek Community". Hellenic Republic: Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 28 January 2011.

Some 35,000 Greeks reside in Belgium. Official Belgian data numbers Greeks in the country at 17,000, but does not take into account Greeks who have taken Belgian citizenship or work for international organizations and enterprises.

- ^ "Argentina: Cultural Relations and Greek Community". Hellenic Republic: Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 9 July 2013.

It is estimated that some 20,000 to 30,000 persons of Greek origin currently reside in Argentina, and there are Greek communities in the wider region of Buenos Aires.

- ^ "Bulgaria: Cultural Relations and Greek Community". Hellenic Republic: Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 28 January 2011.

There are some 28,500 persons of Greek origin and citizenship residing in Bulgaria. This number includes approximately 15,000 Sarakatsani, 2,500 former political refugees, 8,000 "old Greeks", 2,000 university students and 1,000 professionals and their families.

- ^ "Georgia: Cultural Relations and Greek Community". Hellenic Republic: Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 31 January 2011.

The Greek community of Georgia is currently estimated at 15,000 people, mostly elderly people living in the Tsalkas area.

- ^ "Sweden: Cultural Relations and Greek Community". Hellenic Republic: Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 4 February 2011.

The Greek community in Sweden consists of approximately 12,000 – 15,000 Greeks who are permanent inhabitants, included in Swedish society and active in various sectors: science, arts, literature, culture, media, education, business, and politics.

- ^ Hellenic Republic: Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 9 March 2011 http://cizinci.cz/repository/2240/file/Rekove2.pdf.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Kazakhstan: Cultural Relations and Greek Community". Hellenic Republic: Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 3 February 2011.

There are between 10,000 and 12,000 ethnic Greeks living in Kazakhstan, organized in several communities.

- ^ "Switzerland: Cultural Relations and Greek Community". Hellenic Republic: Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 10 December 2015.

The Greek community in Switzerland is estimated to number some 11,000 persons (of a total of 1.5 million foreigners residing in the country.

- ^ "Romania: Cultural Relations and Greek Community". Hellenic Republic: Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 6 December 2013.

The Greek Romanian community numbers some 10,000, and there are many Greeks working in established Greek enterprises in Romania.

- ^ "Greeks in Uzbekistan". Central Asia-Caucasus Analyst. The Central Asia-Caucasus Institute. 21 June 2000.

Currently there are about 9,500 Greeks living in Uzbekistan, with 6,500 living in Tashkent.

- ^ "World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples – Turkey: Rum Orthodox Christians". Minority Rights Group (MRG). 2005. Archived from the original on 29 March 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Pontic". Ethnologue: Languages of the World. SIL International. 2016. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Roberts 2007, pp. 171–172, 222.

- ^ Latacz 2004, pp. 159, 165–166.

- ^ a b c d Sutton 1996.

- ^ Beaton 1996, pp. 1–25.

- ^ CIA World Factbook on Greece: Greek Orthodox 98%, Greek Muslim 1.3%, other 0.7%.

- ^ Georgiev 1981, p. 156: "The Proto-Greek region included Epirus, approximately up to Αυλών in the north including Paravaia, Tymphaia, Athamania, Dolopia, Amphilochia, and Acarnania), west and north Thessaly (Hestiaiotis, Perrhaibia, Tripolis, and Pieria), i.e. more or less the territory of contemporary northwestern Greece)."

- ^ Guibernau & Hutchinson 2004, p. 23: "Indeed, Smith emphasizes that the myth of divine election sustains the continuity of cultural identity, and, in that regard, has enabled certain pre-modern communities such as the Jews, Armenians, and Greeks to survive and persist over centuries and millennia (Smith 1993: 15–20)."

- ^ Smith 1999, p. 21: "It emphasizes the role of myths, memories and symbols of ethnic chosenness, trauma, and the 'golden age' of saints, sages, and heroes in the rise of modern nationalism among the Jews, Armenians, and Greeks—the archetypal diaspora peoples."

- ^ Bryce 2006, p. 91

- ^ Cadogan & Langdon Caskey 1986, p. 125

- ^ Bryce 2006, p. 92

- ^ Drews 1994, p. 21

- ^ Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 243

- ^ "The Greeks". Encyclopædia Britannica. US: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. 2008. Online Edition.

- ^ Chadwick, John (1976). The Mycenaean world. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–3. ISBN 0-521-29037-6.

- ^ Vladimir I. Georgiev, for example, placed Proto-Greek in northwestern Greece during the Late Neolithic period. (Georgiev 1981, p. 192: "Late Neolithic Period: in northwestern Greece the Proto-Greek language had already been formed: this is the original home of the Greeks.")

- ^ Gray & Atkinson 2003, pp. 437–438; Atkinson & Gray 2006, p. 102.

- ^ a b "Linear A and Linear B". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- ^ Castleden 2005, p. 228.

- ^ Tartaron 2013, p. 28; Schofield 2006, pp. 71–72; Panayotou 2007, pp. 417–426.

- ^ Hall 2014, p. 43.

- ^ Chadwick 1976, p. 176 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFChadwick1976 (help).

- ^ a b Castleden 2005, p. 2.

- ^ Hansen 2004, p. 7; Podzuweit 1982, pp. 65–88.

- ^ Castleden 2005, p. 235; Dietrich 1974, p. 156.

- ^ Burckhardt 1999, p. 168: "The establishment of these Panhellenic sites, which yet remained exclusively Hellenic, was a very important element in the growth and self-consciousness of Hellenic nationalism; it was uniquely decisive in breaking down enmity between tribes, and remained the most powerful obstacle to fragmentation into mutually hostile poleis."

- ^ Zuwiyya 2011, pp. 142–143; Budin 2009, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Morgan 1990, pp. 1–25, 148–190.

- ^ "Ancient Greek Civilization". Encyclopædia Britannica. United States: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. 18 February 2016. Online Edition.

- ^ Konstan 2001, pp. 29–50.

- ^ Steinberger 2000, p. 17; Burger 2008, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Burger 2008, pp. 57–58: "Poleis continued to go to war with each other. The Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC) made this painfully clear. The war (really two wars punctuated by a peace) was a duel between Greece's two leading cities, Athens and Sparta. Most other poleis, however, got sucked into the conflict as allies of one side or the other ... The fact that Greeks were willing to fight for their cities against other Greeks in conflicts like the Peloponnesian War showed the limits of the pull of Hellas compared with that of the polis."

- ^ Fox, Robin Lane (2004). "Riding with Alexander". Archaeology. The Archaeological Institute of America.

Alexander inherited the idea of an invasion of the Persian Empire from his father Philip whose advance-force was already out in Asia in 336 BC. Philips campaign had the slogan of "freeing the Greeks" in Asia and "punishing the Persians" for their past sacrileges during their own invasion (a century and a half earlier) of Greece. No doubt, Philip wanted glory and plunder.

- ^ Brice 2012, pp. 281–286.

- ^ "Alexander the Great". Columbia Encyclopedia. United States: Columbia University Press. 2008. Online Edition.

- ^ Green 2008, p. xiii.

- ^ Morris, Ian (December 2005). "Growth of the Greek Colonies in the First Millennium BC" (PDF). Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics. Princeton/Stanford University.

- ^ Wood 2001, p. 8.

- ^ a b Boardman, Griffin & Murray 1991, p. 364

- ^ Arun, Neil (7 August 2007). "Alexander's Gulf outpost uncovered". BBC News.

- ^ Grant 1990, Introduction.

- ^ a b "Hellenistic age". Encyclopædia Britannica. United States: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. 27 May 2015. Online Edition.

- ^ a b c d Harris 1991, pp. 137–138.

- ^ Lucore 2009, p. 51: "The Hellenistic period is commonly portrayed as the great age of Greek scientific discovery, above all in mathematics and astronomy."

- ^ Foltz 2010, pp. 43–46.

- ^ Burton 1993, pp. 244–245.

- ^ Zoch 2000, p. 136.

- ^ "Hellenistic religion". Encyclopædia Britannica. United States: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. 13 May 2015. Online Edition.

- ^ Ferguson 2003, pp. 617–618.

- ^ Dunstan 2011, p. 500.

- ^ Milburn 1988, p. 158.

- ^ Makrides 2009, p. 206.

- ^ Kaldellis 2008, pp. 35–40.

- ^ Howatson 1989, p. 264: "From the fourth century AD onwards the Greeks of the eastern Roman empire called themselves Rhomaioi ('Romans') ..."

- ^ a b Cameron 2009, p. 7.

- ^ Stouraitis 2014, pp. 176, 177.

- ^ Finkelberg 2012, p. 20.

- ^ a b Burstein 1988, pp. 47–49.

- ^ "Byzantine Empire". Encyclopædia Britannica. United States: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. 23 December 2015. Online Edition.

- ^ a b Haldon 1997, p. 50.

- ^ Shahid 1972, pp. 295–296, 305.

- ^ Klein 2004, p. 290 (Note #39); Annales Fuldenses, 389: "Mense lanuario c. epiphaniam Basilii, Graecorum imperatoris, legati cum muneribus et epistolis ad Hludowicum regem Radasbonam venerunt ...".

- ^ Fouracre & Gerberding 1996, p. 345: "The Frankish court no longer regarded the Byzantine Empire as holding valid claims of universality; instead it was now termed the 'Empire of the Greeks'."

- ^ Angelov 2007, p. 96 (including footnote #67); Makrides 2009, p. 74; Magdalino 1991, Chapter XIV: "Hellenism and Nationalism in Byzantium", p. 10.

- ^ Page 2008, pp. 66, 87, 256

- ^ Kaplanis 2014, pp. 86–7

- ^ a b c d e f "Greece during the Byzantine period (c. AD 300–c. 1453), Population and languages, Emerging Greek identity". Encyclopædia Britannica. United States: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. 2008. Online Edition.

- ^ Angold 1975, p. 65, Page 2008, p. 127.

- ^ Kaplanis 2014, p. 92.

- ^ Vasiliev, Alexander A. (1964). History of the Byzantine Empire, 324–1453. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 582. ISBN 9780299809256.

- ^ Jane Perry Clark Carey; Andrew Galbraith Carey (1968). The Web of Modern Greek Politics. Columbia University Press. p. 33.

By the end of the fourteenth century the Byzantine emperor was often called "Emperor of the Hellenes"

- ^ Mango 1965, p. 33.

- ^ See for example Anthony Bryer, 'The Empire of Trebizond and the Pontus' (Variourum, 1980), and his 'Migration and Settlement in the Caucasus and Anatolia' (Variourum, 1988), and other works listed in Caucasian Greeks and Pontic Greeks.

- ^ Norwich 1998, p. xxi.

- ^ Harris 1999, Part II Medieval Libraries: Chapter 6 Byzantine and Moslem Libraries, pp. 71–88

- ^ a b "Renaissance". Encyclopædia Britannica. United States: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. 30 March 2016. Online Edition.

- ^ Robins 1993, p. 8.

- ^ "Aristotelianism". Encyclopædia Britannica. United States: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. 2016. Online Edition.

- ^ "Cyril and Methodius, Saints". The Columbia Encyclopedia. United States: Columbia University Press. 2016. Online Edition.

- ^ a b c d Mazower 2002, pp. 105–107.

- ^ "History of Europe, The Romans". Encyclopædia Britannica. United States: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. 2008. Online Edition.

- ^ Mavrocordatos, Nicholaos (1800). Philotheou Parerga. Grēgorios Kōnstantas (Original from Harvard University Library).

Γένος μεν ημίν των άγαν Ελλήνων

- ^ "Phanariote". Encyclopædia Britannica. United States: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. 2016. Online Edition.

- ^ a b c "History of Greece, Ottoman Empire, The merchant middle class". Encyclopædia Britannica. United States: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. 2008. Online Edition.

- ^ "Greek Constitution of 1822 (Epidaurus)" (PDF) (in Greek). 1822.

- ^ Barutciski 2003, p. 28; Clark 2006, pp. xi–xv; Hershlag 1980, p. 177; Özkırımlı & Sofos 2008, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Üngör 2008, pp. 15–39.

- ^ Broome 1996, "Greek Identity", pp. 22–27

- ^ ὅμαιμος, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ ὁμόγλωσσος, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ I. Polinskaya, "Shared sanctuaries and the gods of others: On the meaning Of 'common' in Herodotus 8.144", in: R. Rosen & I. Sluiter (eds.), Valuing others in Classical Antiquity (LEiden: Brill, 2010), 43-70.

- ^ ὁμότροπος, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus)

- ^ Herodotus, 8.144.2: "The kinship of all Greeks in blood and speech, and the shrines of gods and the sacrifices that we have in common, and the likeness of our way of life."

- ^ Athena S. Leoussi, Steven Grosby, Nationalism and Ethnosymbolism: History, Culture and Ethnicity in the Formation of Nations, Edinburgh University Press, 2006, p. 115

- ^ Adrados 2005, p. xii.

- ^ Finkelberg 2012, p. 20; Harrison 2002, p. 268; Kazhdan & Constable 1982, p. 12; Runciman 1970, p. 14.

- ^ Ševčenko 2002, p. 284.

- ^ Sphrantzes, George (1477). The Chronicle of the Fall.

- ^ Feraios, Rigas. New Political Constitution of the Inhabitants of Rumeli, Asia Minor, the Islands of the Aegean, and the Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia.

- ^ Koliopoulos & Veremis 2002, p. 277.

- ^ Smith 2003, p. 98: "After the Ottoman conquest in 1453, recognition by the Turks of the Greek millet under its Patriarch and Church helped to ensure the persistence of a separate ethnic identity, which, even if it did not produce a "precocious nationalism" among the Greeks, provided the later Greek enlighteners and nationalists with a cultural constituency fed by political dreams and apocalyptic prophecies of the recapture of Constantinople and the restoration of Greek Byzantium and its Orthodox emperor in all his glory."

- ^ Tonkin, Chapman & McDonald 1989.

- ^ Patterson 1998, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Psellos, Michael (1994). Michaelis Pselli Orationes Panegyricae. Stuttgart/Leipzig: Walter de Gruyter. p. 33. ISBN 0-297-82057-5.

- ^ See Iliad, II.2.530 for "Panhellenes" and Iliad II.2.653 for "Hellenes".

- ^ Cartledge 2011, Chapter 4: Argos, p. 23: "The Late Bronze Age in Greece is also called conventionally 'Mycenaean', as we saw in the last chapter. But it might in principle have been called 'Argive', 'Achaean', or 'Danaan', since the three names that Homer does apply to Greeks collectively were 'Argives', 'Achaeans', and 'Danaans'." harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCartledge2011 (help)

- ^ Nagy 2014, Texts and Commentaries – Introduction #2: "Panhellenism is the least common denominator of ancient Greek civilization ... The impulse of Panhellenism is already at work in Homeric and Hesiodic poetry. In the Iliad, the names "Achaeans" and "Danaans" and "Argives" are used synonymously in the sense of Panhellenes = "all Hellenes" = "all Greeks.""

- ^ Herodotus. Histories, 7.94 and 8.73.

- ^ Homer. Iliad, 2.681–685

- ^ a b The Parian Marble, Entry #6: "From when Hellen [son of] Deuc[alion] became king of [Phthi]otis and those previously called Graekoi were named Hellenes."

- ^ Pseudo-Apollodorus. Bibliotheca.

- ^ a b Aristotle. Meteorologica, 1.14: "The deluge in the time of Deucalion, for instance took place chiefly in the Greek world and in it especially about ancient Hellas, the country about Dodona and the Achelous."

- ^ Homer. Iliad, 16.233–16.235: "King Zeus, lord of Dodona ... you who hold wintry Dodona in your sway, where your prophets the Selloi dwell around you."

- ^ Hesiod. Catalogue of Women, Fragment 5.

- ^ a b c d Adrados 2005, pp. xii, 3–5.

- ^ Browning 1983, p. vii: "The Homeric poems were first written down in more or less their present form in the seventh century B.C. Since then Greek has enjoyed a continuous tradition down to the present day. Change there has certainly been. But there has been no break like that between Latin and Romance languages. Ancient Greek is not a foreign language to the Greek of today as Anglo-Saxon is to the modern Englishman. The only other language which enjoys comparable continuity of tradition is Chinese."

- ^ a b c d Smith 1991, pp. 29–32.

- ^ Isaac 2004, p. 504: "Autochthony, being an Athenian idea and represented in many Athenian texts, is likely to have influenced a broad public of readers, wherever Greek literature was read."

- ^ Anna Comnena. Alexiad, Books 1–15.

- ^ Papagrigorakis, Kousoulis & Synodinos 2014, p. 237: "Interpreted with caution, the craniofacial morphology in modern and ancient Greeks indicates elements of ethnic group continuation within the unavoidable multicultural mixtures."

- ^ Argyropoulos, Sassouni & Xeniotou 1989, p. 200: "An overall view of the finding obtained from these cephalometric analyses indicates that the Greek ethnic group has remained genetically stable in its cephalic and facial morphology for the last 4,000 years."

- ^ "Πίνακας 9. Πληθυσμός κατά υπηκοότητα και φύλο" (PDF) (in Greek). Hellenic Statistical Authority. 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 February 2009. Retrieved 7 January 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "CIA Factbook". Central Intelligence Agency. United States Government. 2007. Retrieved 19 December 2008.

- ^ "Census of Population 2001". Γραφείο Τύπου και Πληροφοριών, Υπουργείο Εσωτερικών, Κυπριακή Δημοκρατία. Archived from the original on 3 February 2017. Retrieved 11 June 2016.