Europe: Difference between revisions

m →References: remove duplicate reflist |

→Modern Period: Finished the bulk of the writing. |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 50: | Line 50: | ||

{{seealso|Ancient Greece|Ancient Rome}} |

{{seealso|Ancient Greece|Ancient Rome}} |

||

[[Image:Selinonte_Temple_E2.jpg|thumb|left|The Greek Temple of Hera, [[Selinunte]], [[Sicily]]]] |

[[Image:Selinonte_Temple_E2.jpg|thumb|left|The Greek Temple of Hera, [[Selinunte]], [[Sicily]]]] |

||

[[Ancient Greece]] had a profound impact on Western civilization. Western [[democracy|democratic]] and [[individualism|individualistic]] [[culture]] are often attributed to Ancient Greece.<ref name="natgeo 76">National Geographic, 76.</ref> The Greeks invented the [[polis]], or city-state, which played a fundamental role in their concept of identity.<ref name="natgeo 82">National Geographic, 82.</ref> These Greek political ideals were rediscovered in the late 18th century by European philosophers and idealists. Greece also generated many cultural contributions: in [[philosophy]], [[humanism]] and [[rationalism]] under [[Aristotle]], [[Socrates]] and [[Plato]]; in [[historiography|history]] with [[Herodotus]] and [[Thucydides]]; in dramatic and narrative verse, starting with the epic poems of [[Homer]];<ref name="natgeo 76"/> and in [[science]] with [[Pythagoras]], [[Euclid]] and [[Archimedes]]. |

[[Ancient Greece]] had a profound impact on Western civilization. Western [[democracy|democratic]] and [[individualism|individualistic]] [[culture]] are often attributed to Ancient Greece.<ref name="natgeo 76">National Geographic, 76.</ref> The Greeks invented the [[polis]], or city-state, which played a fundamental role in their concept of identity.<ref name="natgeo 82">National Geographic, 82.</ref> These Greek political ideals were rediscovered in the late 18th century by European philosophers and idealists. Greece also generated many cultural contributions: in [[philosophy]], [[humanism]] and [[rationalism]] under [[Aristotle]], [[Socrates]] and [[Plato]]; in [[historiography|history]] with [[Herodotus]] and [[Thucydides]]; in dramatic and narrative verse, starting with the epic poems of [[Homer]];<ref name="natgeo 76"/> and in [[science]] with [[Pythagoras]], [[Euclid]] and [[Archimedes]].<ref>{{Harvard reference| first=Thomas Little | last=Heath| authorlink= T. L. Heath| title=A History of Greek Mathematics, Volume I| publisher=Dover publications| year=1981| isbn=0486240738}}</ref><ref>{{Harvard reference| first=Thomas Little| last=Heath| authorlink= T. L. Heath| title=A History of Greek Mathematics, Volume II| publisher=Dover publications| year=1981| isbn=0486240746}}</ref><ref>Pedersen, Olaf. ''Early Physics and Astronomy: A Historical Introduction''. 2nd edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993. </ref> |

||

<ref>{{Harvard reference |

|||

| first=Thomas Little |

|||

| last=Heath |

|||

| authorlink= T. L. Heath |

|||

| title=A History of Greek Mathematics, Volume I |

|||

| publisher=Dover publications |

|||

| year=1981 |

|||

| isbn=0486240738 |

|||

}}</ref><ref> |

|||

{{Harvard reference |

|||

| first=Thomas Little |

|||

| last=Heath |

|||

| authorlink= T. L. Heath |

|||

| title=A History of Greek Mathematics, Volume II |

|||

| publisher=Dover publications |

|||

| year=1981 |

|||

| isbn=0486240746 |

|||

}}</ref><ref>Pedersen, Olaf. ''Early Physics and Astronomy: A Historical Introduction''. 2nd edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993. </ref> |

|||

Another major influence on Europe came from the [[Roman Empire]] which left its mark on [[Roman law|law]], [[Latin|language]], [[Roman engineering|engineering]], [[Roman architecture|architecture]], and [[centralized government|government]].<ref name="natgeo 77">National Geographic, 76-77.</ref> During the ''[[pax romana]]'', the Roman Empire expanded to encompass the entire [[Mediterranean Basin]] and much of Europe. <ref> |

Another major influence on Europe came from the [[Roman Empire]] which left its mark on [[Roman law|law]], [[Latin|language]], [[Roman engineering|engineering]], [[Roman architecture|architecture]], and [[centralized government|government]].<ref name="natgeo 77">National Geographic, 76-77.</ref> During the ''[[pax romana]]'', the Roman Empire expanded to encompass the entire [[Mediterranean Basin]] and much of Europe.<ref>{{citation|last=McEvedy|first=Colin|title=The Penguin Atlas of Medieval History|publisher=Penguin Books|year=1961}}</ref> [[Stoicism]] influenced emperors such as [[Hadrian]], [[Antoninus Pius]] and [[Marcus Aurelius]], who all spent time on the Empire's northern border fighting [[Germanic peoples|Germanic]], [[Picts|Pictish]] and [[Scottish people|Scottish]] tribes. <ref name="natgeo 123">National Geographic, 123.</ref><ref> Foster, Sally M., ''Picts, Gaels, and Scots: Early Historic Scotland.'' Batsford, London, 2004. ISBN 0-7134-8874-3</ref> [[Christianity]] was eventually [[Constantine I and Christianity|legitimized]] by [[Constantine I]] after three centuries of imperial [[Persecution of Christians|persecution]]. |

||

{{citation| |

|||

last=McEvedy|first=Colin|title=The Penguin Atlas of Medieval History|publisher=Penguin Books|year=1961}}</ref> [[Stoicism]] influenced emperors such as [[Hadrian]], [[Antoninus Pius]] and [[Marcus Aurelius]], who all spent time on the Empire's northern border fighting [[Germanic peoples|Germanic]], [[Picts|Pictish]] and [[Scottish people|Scottish]] tribes. <ref name="natgeo 123">National Geographic, 123.</ref> |

|||

<ref> Foster, Sally M., ''Picts, Gaels, and Scots: Early Historic Scotland.'' Batsford, London, 2004. ISBN 0-7134-8874-3</ref> [[Christianity]] was eventually [[Constantine I and Christianity|legitimized]] by [[Constantine I]] after three centuries of imperial [[Persecution of Christians|persecution]]. |

|||

=== Dark Ages === |

=== Dark Ages === |

||

| Line 79: | Line 58: | ||

{{seealso|Dark Ages|Age of Migrations}} |

{{seealso|Dark Ages|Age of Migrations}} |

||

[[Image:Rolandfealty.jpg|thumb|right|[[Roland]] pledges [[fealty]] to [[Charlemagne]], [[Holy Roman Emperor]]]] |

[[Image:Rolandfealty.jpg|thumb|right|[[Roland]] pledges [[fealty]] to [[Charlemagne]], [[Holy Roman Emperor]]]] |

||

During the [[decline of the Roman Empire]], Europe entered a long period of change arising from what is known in America as the [[Age of Migrations]]. There were numerous invasions and migrations amongst the [[Ostrogoths]], [[Visigoths]], [[Goths]], [[Vandals]], [[Huns]], [[Franks]], [[Angles]], [[Saxons]] and, slightly later, the [[Vikings]] |

During the [[decline of the Roman Empire]], Europe entered a long period of change arising from what is known in America as the [[Age of Migrations]]. There were numerous invasions and migrations amongst the [[Ostrogoths]], [[Visigoths]], [[Goths]], [[Vandals]], [[Huns]], [[Franks]], [[Angles]], [[Saxons]] and, slightly later, the [[Vikings]]. The period became known as the "[[Dark Ages]]" to Renaissance thinkers such as [[Petrarch]].<ref>[http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0022-5037%28194301%294%3A1%3C49%3ASROTQO%3E2.0.CO%3B2-W Renaissance or Prenaissance], ''Journal of the History of Ideas'', Vol. 4, No. 1. (Jan., 1943), pp. 69-74. </ref> Isolated monastic communities in Ireland, Scotland and elsewhere carefully safeguarded and compiled written knowledge accumulated previously; very few written records survive and much literature, philosophy, mathematics, and other thinking from the classical period disappeared from European popular currency.<ref>[[Norman Cantor|Norman F. Cantor]], ''The Medieval World 300 to 1300''.</ref> |

||

<ref>[http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0022-5037%28194301%294%3A1%3C49%3ASROTQO%3E2.0.CO%3B2-W Renaissance or Prenaissance], ''Journal of the History of Ideas'', Vol. 4, No. 1. (Jan., 1943), pp. 69-74. </ref> Isolated monastic communities in Ireland, Scotland and elsewhere carefully safeguarded and compiled written knowledge accumulated previously; very few written records survive and much literature, philosophy, mathematics, and other thinking from the classical period disappeared from European popular currency. <ref>[[Norman Cantor|Norman F. Cantor]], ''The Medieval World 300 to 1300''.</ref> |

|||

During the Dark Ages, the [[Western Roman Empire]] fell under the control of Celt, Slav and Germanic tribes. The Celtic tribes established their kingdoms in [[Gaul]], the predecessor to the Frankish kingdoms that eventually became [[France]].<ref name="natgeo 140">National Geographic, 140</ref> The Germanic and Slav tribes established their domains over Central and Eastern Europe respectively.<ref name="natgeo 143">National Geographic, 143-145.</ref> Eventually the [[Franks|Frankish tribes]] were united under [[Clovis I]].<ref name="natgeo 162">National Geographic, 162.</ref> [[Charlemagne]], a Frankish king of the [[Carolingian]] dynasty who had conquered most of Western Europe, was anointed "Holy Roman Emperor" by the Pope in [[800]]. This led to the founding of the [[Holy Roman Empire]], which eventually became centered in the German principalities of central Europe.<ref name="natgeo 166">National Geographic, 166.</ref> |

During the Dark Ages, the [[Western Roman Empire]] fell under the control of Celt, Slav and Germanic tribes. The Celtic tribes established their kingdoms in [[Gaul]], the predecessor to the Frankish kingdoms that eventually became [[France]].<ref name="natgeo 140">National Geographic, 140</ref> The Germanic and Slav tribes established their domains over Central and Eastern Europe respectively.<ref name="natgeo 143">National Geographic, 143-145.</ref> Eventually the [[Franks|Frankish tribes]] were united under [[Clovis I]].<ref name="natgeo 162">National Geographic, 162.</ref> [[Charlemagne]], a Frankish king of the [[Carolingian]] dynasty who had conquered most of Western Europe, was anointed "Holy Roman Emperor" by the Pope in [[800]]. This led to the founding of the [[Holy Roman Empire]], which eventually became centered in the German principalities of central Europe.<ref name="natgeo 166">National Geographic, 166.</ref> |

||

| Line 91: | Line 69: | ||

The Middle Ages were dominated by the two upper echelons of the social structure: the nobility and the clergy. Feudalism already developed in [[France]] in the [[Early Middle Ages]], but soon spread throughout Europe.<ref name="natgeo 158">National Geographic, 158.</ref> The struggle between the nobility and the monarchy in England led to the writing of the [[Magna Carta]] and the establishment of a [[parliament]].<ref name="natgeo 186">National Geographic, 186.</ref> The primary source of culture in this period came from the [[Roman Catholic Church]]. Through monasteries and cathedral schools, the Church was responsible for education in much of Europe.<ref name="natgeo 158"/> |

The Middle Ages were dominated by the two upper echelons of the social structure: the nobility and the clergy. Feudalism already developed in [[France]] in the [[Early Middle Ages]], but soon spread throughout Europe.<ref name="natgeo 158">National Geographic, 158.</ref> The struggle between the nobility and the monarchy in England led to the writing of the [[Magna Carta]] and the establishment of a [[parliament]].<ref name="natgeo 186">National Geographic, 186.</ref> The primary source of culture in this period came from the [[Roman Catholic Church]]. Through monasteries and cathedral schools, the Church was responsible for education in much of Europe.<ref name="natgeo 158"/> |

||

The [[Papacy]] reached the height of its power during the High Middle Ages. The [[East-West Schism]] in [[1054]] split the former Roman Empire religiously, with the [[Eastern Orthodox Church]] in the [[Byzantine Empire]] and the [[Roman Catholic Church]] in the former Western Roman Empire. In [[1095]] [[Pope Urban II]] called for a [[Crusades|crusade]] against [[Muslims]] occupying [[Jerusalem]] and the [[Holy Land]].<ref name="natgeo 192">National Geographic, 192.</ref> |

The [[Papacy]] reached the height of its power during the High Middle Ages. The [[East-West Schism]] in [[1054]] split the former Roman Empire religiously, with the [[Eastern Orthodox Church]] in the [[Byzantine Empire]] and the [[Roman Catholic Church]] in the former Western Roman Empire. In [[1095]] [[Pope Urban II]] called for a [[Crusades|crusade]] against [[Muslims]] occupying [[Jerusalem]] and the [[Holy Land]].<ref name="natgeo 192">National Geographic, 192.</ref> In Europe itself, the Church organized the [[Inquisition]] against heretics. In [[Spain]], the [[Reconquista]] concluded with the fall of [[Granada]] in [[1492]], ending over seven centuries of Muslim rule in the [[Iberian Peninsula]].<ref name="natgeo 199">National Geographic, 199.</ref> |

||

In Europe itself, the Church organized the [[Inquisition]] against heretics. In [[Spain]], the [[Reconquista]] concluded with the fall of [[Granada]] in [[1492]], ending over seven centuries of Muslim rule in the [[Iberian Peninsula]].<ref name="natgeo 199">National Geographic, 199.</ref> |

|||

Europe was devastated in the mid-14th century by the [[Black Death]], which killed an estimated 25 million people - a third of the European population at the time.<ref name="natgeo 158"/> Successive epidemics led to increased religious fervor,<ref name="natgeo 159">National Geographic, 159.</ref> a result of which was widespread [[persecution of Jews]].<ref name="natgeo 223">National Geographic, 223.</ref> |

Europe was devastated in the mid-14th century by the [[Black Death]], which killed an estimated 25 million people - a third of the European population at the time.<ref name="natgeo 158"/> Successive epidemics led to increased religious fervor,<ref name="natgeo 159">National Geographic, 159.</ref> a result of which was widespread [[persecution of Jews]].<ref name="natgeo 223">National Geographic, 223.</ref> |

||

| Line 101: | Line 78: | ||

{{main|Early modern period}} |

{{main|Early modern period}} |

||

{{seealso|Renaissance|Protestant Reformation|Age of Discovery}} |

{{seealso|Renaissance|Protestant Reformation|Age of Discovery}} |

||

The [[Renaissance]] was a period of cultural change originating in Italy in the 14C. The rise of a [[Renaissance humanism|new humanism]] was accompanied by the recovery of forgotten [[Renaissance#Assimilation of Greek and Arabic knowledge|classical and Arabic knowledge]] from monastic libraries and the Islamic world.<ref name="natgeo 159"/> |

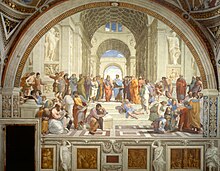

The [[Renaissance]] was a period of cultural change originating in Italy in the 14C. The rise of a [[Renaissance humanism|new humanism]] was accompanied by the recovery of forgotten [[Renaissance#Assimilation of Greek and Arabic knowledge|classical and Arabic knowledge]] from monastic libraries and the Islamic world.<ref name="natgeo 159"/><ref>[[Roberto Weiss|Weiss, Roberto]] (1969) ''The Renaissance Discovery of Classical Antiquity'', ISBN 1-597-40150-1</ref><ref>cob Burckhardt|Burckhardt, Jacob (1878), [http://www.boisestate.edu/courses/hy309/docs/burckhardt/burckhardt.html ''The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy''], trans S.G.C Middlemore, republished in 1990 ISBN 0-14-044534-X </ref> The Renaissance spread across Europe between the 14th and 16th centuries: it saw the flowering of art, philosophy, music and the sciences, under the joint patronage of royalty, the nobility, the Roman Catholic Church and an emerging merchant class.<ref name="natgeo 254">National Geographic, 254.</ref><ref>Jensen, De Lamar (1992), ''Renaissance Europe'', ISBN 0-395-88947-2</ref><ref>{{citation|last=Levey|first=Michael|title=Early Rennaissance|publisher=Penguin Books|year=1967}}</ref> Patrons in Italy, including the [[Medici]] family of [[Florence|Florentine]] bankers and the [[Pope]]s in [[Rome]], funded prolific [[quattrocento]] and [[cinquecento]] artists such as [[Raphael]], [[Michelangelo]] and [[Leonardo da Vinci]].<ref name="natgeo 292">National Geographic, 292.</ref><ref>{{citation|last=Levey|first=Michael|title=High Rennaissance|publisher=Penguin Books|year=1971}}</ref> |

||

The Renaissance spread across Europe between the 14th and 16th centuries: it saw the flowering of art, philosophy, music and the sciences, under the joint patronage of royalty, the nobility, the Roman Catholic Church and an emerging merchant class.<ref name="natgeo 254">National Geographic, 254.</ref> |

|||

<ref>Jensen, De Lamar (1992), ''Renaissance Europe'', ISBN 0-395-88947-2</ref> |

|||

<ref>{{citation| |

|||

last=Levey|first=Michael|title=Early Rennaissance|publisher=Penguin Books|year=1967}}</ref> |

|||

Patrons in Italy, including the [[Medici]] family of [[Florence|Florentine]] bankers and the [[Pope]]s in [[Rome]], funded prolific [[quattrocento]] and [[cinquecento]] artists such as [[Raphael]], [[Michelangelo]] and [[Leonardo da Vinci]].<ref name="natgeo 292">National Geographic, 292.</ref> |

|||

<ref>{{citation| |

|||

last=Levey|first=Michael|title=High Rennaissance|publisher=Penguin Books|year=1971}}</ref> |

|||

Political intrigue within the Church in the mid-14th century caused the [[Western Schism|Great Schism]]. During this forty-year period, two popes - one in [[Avignon]] and one in [[Rome]] - claimed rulership over the Church. Although the schism was eventually healed in [[1417]], the papacy's spiritual authority had suffered greatly.<ref name="natgeo 193">National Geographic, 193.</ref> The Church's power was further weakened by the [[Protestant Reformation]] of [[Martin Luther]], a result of the lack of reform within the Church. The Reformation also damaged the Holy Roman Empire's power, as German princes became divided between Catholic, Protestant and [[Calvinist]] faiths.<ref name="natgeo 256">National Geographic, 256-257.</ref> This eventually led to the [[Thirty Years War]] ([[1618]]-[[1648]]), which crippled the Holy Roman Empire and devastated much of Germany. In the aftermath of the [[Peace of Westphalia]], [[France]] rose to predominance within Europe.<ref name="natgeo 269">National Geographic, 269.</ref> |

Political intrigue within the Church in the mid-14th century caused the [[Western Schism|Great Schism]]. During this forty-year period, two popes - one in [[Avignon]] and one in [[Rome]] - claimed rulership over the Church. Although the schism was eventually healed in [[1417]], the papacy's spiritual authority had suffered greatly.<ref name="natgeo 193">National Geographic, 193.</ref> The Church's power was further weakened by the [[Protestant Reformation]] of [[Martin Luther]], a result of the lack of reform within the Church. The Reformation also damaged the Holy Roman Empire's power, as German princes became divided between Catholic, Protestant and [[Calvinist]] faiths.<ref name="natgeo 256">National Geographic, 256-257.</ref> This eventually led to the [[Thirty Years War]] ([[1618]]-[[1648]]), which crippled the Holy Roman Empire and devastated much of Germany. In the aftermath of the [[Peace of Westphalia]], [[France]] rose to predominance within Europe.<ref name="natgeo 269">National Geographic, 269.</ref> |

||

[[Image:MercatormapFullEurope16thcentury.jpg|thumb|left|Map of Europe made by [[Gerardus Mercator]]]] |

[[Image:MercatormapFullEurope16thcentury.jpg|thumb|left|Map of Europe made by [[Gerardus Mercator]]]] |

||

The Renaissance and the [[New Monarchs]] marked the start of an [[Age of Discovery]], a period of exploration, invention, and scientific development |

The Renaissance and the [[New Monarchs]] marked the start of an [[Age of Discovery]], a period of exploration, invention, and scientific development. In the 15th century, [[Portugal]] and [[Spain]], the two greatest naval powers of the time, took the lead in exploring the world.<ref name="natgeo 296">National Geographic, 296.</ref> [[Christopher Columbus]] discovered the [[New World]] in the [[1498]], and soon after the Spanish and Portuguese began establishing colonial empires in the Americas.<ref name="natgeo 338">National Geographic, 338.</ref> [[France]], the [[Netherlands]] and [[England]] soon followed in building large colonial empires with vast holdings in [[Africa]], [[the Americas]], and [[Asia]]. |

||

=== 18th and 19th centuries === |

|||

===Modern Period=== |

|||

{{main|Modern History}} |

{{main|Modern History}} |

||

{{seealso|Industrial Revolution|French Revolution}} |

{{seealso|Industrial Revolution|French Revolution}} |

||

After the age of discovery, the ideas of [[democracy]] took hold in Europe. Struggles for independence arose, most notably in [[France]] during the period known as the [[French Revolution]]. This led to vast upheaval in Europe as these revolutionary ideas propagated across the continent. The rise of democracy led to increased tension within Europe on top of the tension already existing because of competition within the [[New World]]. The most famous of these conflicts happened when [[Napoleon I of France|Napoleon Bonaparte]] rose to power and set out on a conquest, forming a new [[First French Empire|French Empire]], which soon collapsed. After these conquests Europe stabilized, but the old foundations were already beginning to crumble. |

|||

[[The Enlightenment]] arose during the 18th century as a powerful intellectual movement in which scientific and reason-based thought began to emerge.<ref name="natgeo 255">National Geographic, 255.</ref> The [[French Revolution]] grew out of the Enlightenment and [[bourgeoisie]] discontent with the aristocracy and clergy's monopoly on political power. The Revolution succeeded at toppling the monarchy and the upper classes and established a [[First French Republic|French republic]].<ref name="natgeo 350">National Geographic, 350.</ref> The [[Napoleonic Wars]], which took place over the course of fifteen years, marked the end of the French Revolution. During the Napoleonic Wars, [[Napoleon I of France|Napoleon Bonaparte]] rose to power and established a [[First French Empire|French Empire]] that grew to encompass almost all of Europe before collapsing.<ref name="natgeo 360">National Geographic, 360.</ref> |

|||

The [[Industrial Revolution]] started in [[Kingdom of Great Britain|Great Britain]] in the late 18th century, leading to a move away from agriculture, much greater general prosperity and a corresponding increase in population. Many of the states in Europe took their present form in the [[aftermath of World War I#Geopolitical and Economic Consequences|aftermath of World War I]]. From the end of [[World War II]] through the end of the [[Cold War]], Europe was divided into two major political and economic blocks: [[Communism|Communist]] nations in [[Eastern Europe]] and [[Capitalist]] countries in [[Southern Europe]], [[Northern Europe]] and [[Western Europe]]. Disintegration of the [[Iron Curtain]] and [[Eastern Block]] accelerated in 1989 with the fall of the [[Berlin Wall]], culminating in the formal dissolution of the [[Soviet Union]] in 1991. |

|||

But French armies brought with them the concepts of [[liberalism]], [[nationalism]] and a new [[Napoleonic Code|legal system]], all of which had a powerful impact on the lower and middle classes of other European nations.<ref name="natgeo 350">National Geographic, 350.</ref> The [[Congress of Vienna]] was convened after Napoleon's downfall. It established a new balance of power in Europe centered on the five "[[great power]]s": [[Great Britain]], [[France]], [[Prussia]], [[Austria]] and [[Russia]].<ref name="natgeo 367">National Geographic, 367.</ref> This balance would remain in place until the [[Revolutions of 1848]], during which liberal uprisings affected all of continental Europe except for Russia. The revolutions were eventually put down by more conservative elements and few reforms resulted.<ref name="natgeo 371">National Geographic, 371-373.</ref> |

|||

[[Image:European flag in the wind.jpg|thumb|250px|The [[Council of Europe]] created in 1955 [[flag of Europe|a flag]] for itself and all of Europe. Today it is most commonly associated with the [[European Union]]. It has multiple roles, and varying legitimacy for the role as an ''official'' flag for the continent as a whole.]] |

|||

The [[Industrial Revolution]] started in [[Kingdom of Great Britain|Great Britain]] in the late 18th century. Although it started mainly as a technological leap, it soon led to reforms in social and economic spheres as well.<ref name="natgeo 368">National Geographic, 368.</ref> The Industrial Revolution led to the formation of the first [[child labor]] laws and [[organized labor]] movements. [[Karl Marx]] also began writing about [[socialism]] during this time.<ref name="natgeo 369">National Geographic, 369.</ref> |

|||

[[European integration]] has been a theme in European politics since the end of the first World War, and has accelerated since the end of the [[Cold War]]. Following the devastation of Europe in the second World War, the idea of European integration led to the creation of the [[Council of Europe]] in Strasbourg in 1949, which produced in 1950 the [[European Convention on Human Rights]] and a [[European Court of Human Rights]]. After the fall of the [[Berlin Wall]], former communist countries in central and eastern Europe were able to accede to the Council of Europe, which now comprises all 47 states in Europe with the exception of Belarus because of its non-democratic government. In 1951, a few European states agreed to confer powers over their steel and coal production to the [[European Coal and Steel Community]] in Luxembourg. This transfer of national powers to a "Community" to be exercised by its Commission was paralleled under the 1957 Treaties of Rome establishing the [[European Atomic Energy Community]] and the [[European Economic Community]] in Brussels. The present [[European Union]], the successor to the [[European Communities]], has enlarged from 6 original founding members to 27 today. The European Union has developed from a trade-oriented organisation into one resembling a confederation in a number of respects. The European Union, or EU, describes itself as a family of democratic European countries, committed to working together for peace and prosperity. The organisation oversees co-operation among its members in diverse areas, including trade, the environment, transport, security, science, education and employment. Human rights and democracy remain the domain of the Council of Europe, thus extending these standards to the whole of Europe. European membership of [[NATO]] has also increased since the end of the Cold War, with the admission of a number of eastern European countries. |

|||

=== 20th century and present === |

|||

The first half of the 20th century was dominated by two world wars and an economic depression. [[World War I]], which was fought between [[1914]] and [[1918]], was an incredibly destructive conflict. It started when the Austrian Archduke [[Franz Ferdinand]] was assassinated by a [[Serbia]]n nationalist.<ref name="natgeo 407">National Geographic, 407.</ref> Through complicated series of treaties, all the nations in Europe were drawn into the war, during which between 10 and 13 million people lost their lives.<ref name="natgeo 440">National Geographic, 440.</ref> World War I changed the map of Europe. [[Russia]] was plunged into the [[Russian Revolution]], after which it became the [[Soviet Union]].<ref name="natgeo 480">National Geographic, 480.</ref> [[Austria-Hungary]] and the [[Ottoman Empire]] collapsed completely, and many other nations had their borders redrawn or eliminated altogether. The [[Treaty of Versailles]] was harsh towards [[Germany]], upon whom it placed full responsibility for the war and imposed heavy sanctions.<ref name="natgeo 443">National Geographic, 443.</ref> |

|||

The collapse of the [[New York Stock Exchange]] in 1929 sent economic shockwaves throughout the global economy and plunged the world into the [[Great Depression]] during the [[1930s]]. Anti-democratic movements strengthened in Central and Eastern Europe during the economic crisis, placing [[fascist]] leaders [[Adolf Hitler]] of [[Nazi Germany]] and [[Benito Mussolini]] of [[Italy]] in power.<ref name="natgeo 438">National Geographic, 438.</ref> Hitler's [[1939 invasion of Poland]] marked the beginning of [[World War II]] in Europe, which lasted until the fall of Berlin in 1945. The war was the largest and most destructive in human history, with 60 million dead across the world.<ref name="natgeo 439">National Geographic, 439.</ref> |

|||

World War II's destruction ended European dominance in world affairs, replaced by the now-[[superpower]] United States and the Soviet Union, who were soon locked in the fifty-year [[Cold War]]. An "[[iron curtain]]" divided the continent into two rival blocs, with [[NATO]] in Western Europe and the [[Warsaw Pact]] in Eastern Europe.<ref name="natgeo 530">National Geographic, 530.</ref> The Cold War ended in [[1991]] with the fall of the Soviet Union. Elsewhere in the world, [[decolonization]] led to independence for nations in Asia and Africa as the old European colonial empires crumbled.<ref name="natgeo 534">National Geographic, 534.</ref> [[European integration]] accelerated beginning in the 1990s, as the [[European Union]] expanded to include 27 European nations.<ref name="natgeo 535">National Geographic, 535.</ref> |

|||

==Geography and extent== |

==Geography and extent== |

||

Revision as of 00:37, 30 November 2007

| Area | 10,180,000 km² (3,930,000 sq mi) |

| Population | 710,000,000 |

| Government | 48 countries, 27 of which are in the European Union |

| Internet TLD | Multiple |

| Calling Code | Multiple |

Europe is one of the seven traditional continents of the Earth. Physically and geologically, Europe is the westernmost peninsula of Eurasia, west of Asia. Europe is bounded to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the west by the Atlantic Ocean, to the south by the Mediterranean Sea, to the southeast by the Caucasus Mountains and the Black Sea and the waterways connecting the Black Sea to the Mediterranean. To the east, Europe is generally divided from Asia by the water divide of the Ural Mountains, the Ural River, and by the Caspian Sea.

Europe is the world's second-smallest continent in terms of area, covering about 10,180,000 square kilometres (3,930,000 sq mi) or 2.0% of the Earth's surface. The only continent smaller than Europe is Australia. It is the third most populous continent (after Asia and Africa) with a population of 710,000,000 or about 11% of the world's population. However, the term continent can refer to a cultural and political distinction or a physiographic one, leading to various perspectives about Europe's precise borders, area and population. Of Europe's 48 countries, Russia is its largest by area and population, while the Vatican is the smallest.

Europe is the birthplace of Western culture. European nations played a predominant role in global affairs from the 16th century onwards, especially after the beginning of colonization. By the 17th and 18th centuries European nations controlled most of Africa, the Americas and large portions of Asia. World War I and World War II led to a decline in European dominance in world affairs as the United States and Soviet Union took preeminence. The Cold War between those two superpowers divided Europe along the Iron Curtain. European integration led to the formation of the Council of Europe and the European Union in Western Europe, both of which eventually expanded to include Central and Eastern Europe after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Etymology

In ancient Greek mythology, Europa was a Phoenician princess who was abducted by Zeus in bull form and taken to the island of Crete, where she gave birth to Minos, Rhadamanthus and Sarpedon. For Homer, Europe (Greek: Εὐρώπη Eurṓpē; see also List of traditional Greek place names) was this mythological queen of Crete, not a geographical designation. Later Europa stood for mainland Greece, and by 500 BC its meaning had been extended to lands to the north.

In etymology one theory suggests the name Europe is derived from the Greek words meaning broad (eurys) and face (opsis)—broad having been an epithet of Earth itself in the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European religion; see Prithvi (Plataia). A minority, however, suggest this Greek popular etymology is really based on a Semitic word such as the Akkadian erebu meaning "to go down, set",[1] cognate to Phoenician 'ereb "evening; west" and Arabic Maghreb, Hebrew ma'ariv. (see also Erebus).

The majority of major world languages use words derived from "Europa" to refer to the continent—e.g. Chinese uses the word Ōuzhōu (歐洲), which is an abbreviation of the transliterated name Ōuluóbā zhōu (歐羅巴洲). However, for centuries, the Turks used the term Frengistan (land of the Franks) in referring to Europe.[2]

History

Prehistory

Homo georgicus, which lived roughly 1.8 million years ago in Georgia, is the first hominid to have so far been discovered in Europe.[3] Other hominid remains, dating back roughly 1 million years, have been discovered in Spain. [4] Neanderthal man (named for the Neander Valley in Germany) first migrated to Europe 150,000 years ago and disappeared from the fossil record about 30,000 years ago. The Neanderthals were supplanted by the Cro-Magnons, who appeared around 40,000 years ago.[5] During this period many megalithic monuments such as Stonehenge were constructed throughout Europe. [6]

Classical antiquity

Ancient Greece had a profound impact on Western civilization. Western democratic and individualistic culture are often attributed to Ancient Greece.[7] The Greeks invented the polis, or city-state, which played a fundamental role in their concept of identity.[8] These Greek political ideals were rediscovered in the late 18th century by European philosophers and idealists. Greece also generated many cultural contributions: in philosophy, humanism and rationalism under Aristotle, Socrates and Plato; in history with Herodotus and Thucydides; in dramatic and narrative verse, starting with the epic poems of Homer;[7] and in science with Pythagoras, Euclid and Archimedes.[9][10][11]

Another major influence on Europe came from the Roman Empire which left its mark on law, language, engineering, architecture, and government.[12] During the pax romana, the Roman Empire expanded to encompass the entire Mediterranean Basin and much of Europe.[13] Stoicism influenced emperors such as Hadrian, Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius, who all spent time on the Empire's northern border fighting Germanic, Pictish and Scottish tribes. [14][15] Christianity was eventually legitimized by Constantine I after three centuries of imperial persecution.

Dark Ages

During the decline of the Roman Empire, Europe entered a long period of change arising from what is known in America as the Age of Migrations. There were numerous invasions and migrations amongst the Ostrogoths, Visigoths, Goths, Vandals, Huns, Franks, Angles, Saxons and, slightly later, the Vikings. The period became known as the "Dark Ages" to Renaissance thinkers such as Petrarch.[16] Isolated monastic communities in Ireland, Scotland and elsewhere carefully safeguarded and compiled written knowledge accumulated previously; very few written records survive and much literature, philosophy, mathematics, and other thinking from the classical period disappeared from European popular currency.[17]

During the Dark Ages, the Western Roman Empire fell under the control of Celt, Slav and Germanic tribes. The Celtic tribes established their kingdoms in Gaul, the predecessor to the Frankish kingdoms that eventually became France.[18] The Germanic and Slav tribes established their domains over Central and Eastern Europe respectively.[19] Eventually the Frankish tribes were united under Clovis I.[20] Charlemagne, a Frankish king of the Carolingian dynasty who had conquered most of Western Europe, was anointed "Holy Roman Emperor" by the Pope in 800. This led to the founding of the Holy Roman Empire, which eventually became centered in the German principalities of central Europe.[21]

The Eastern Roman Empire became known in the west as the Byzantine Empire. Based in Constantinople, they viewed themselves as the natural successors to the Roman Empire.[22] Emperor Justinian I presided over Constantinople's first golden age: he established a legal code, funded the construction of the Hagia Sophia and brought the Christian church under state control.[23] Fatally weakened by the sack of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade, the Byzantines fell in 1453 when they were conquered by the Ottoman Empire.[24]

Middle Ages

The Middle Ages were dominated by the two upper echelons of the social structure: the nobility and the clergy. Feudalism already developed in France in the Early Middle Ages, but soon spread throughout Europe.[25] The struggle between the nobility and the monarchy in England led to the writing of the Magna Carta and the establishment of a parliament.[26] The primary source of culture in this period came from the Roman Catholic Church. Through monasteries and cathedral schools, the Church was responsible for education in much of Europe.[25]

The Papacy reached the height of its power during the High Middle Ages. The East-West Schism in 1054 split the former Roman Empire religiously, with the Eastern Orthodox Church in the Byzantine Empire and the Roman Catholic Church in the former Western Roman Empire. In 1095 Pope Urban II called for a crusade against Muslims occupying Jerusalem and the Holy Land.[27] In Europe itself, the Church organized the Inquisition against heretics. In Spain, the Reconquista concluded with the fall of Granada in 1492, ending over seven centuries of Muslim rule in the Iberian Peninsula.[28]

Europe was devastated in the mid-14th century by the Black Death, which killed an estimated 25 million people - a third of the European population at the time.[25] Successive epidemics led to increased religious fervor,[29] a result of which was widespread persecution of Jews.[30]

Early modern period

The Renaissance was a period of cultural change originating in Italy in the 14C. The rise of a new humanism was accompanied by the recovery of forgotten classical and Arabic knowledge from monastic libraries and the Islamic world.[29][31][32] The Renaissance spread across Europe between the 14th and 16th centuries: it saw the flowering of art, philosophy, music and the sciences, under the joint patronage of royalty, the nobility, the Roman Catholic Church and an emerging merchant class.[33][34][35] Patrons in Italy, including the Medici family of Florentine bankers and the Popes in Rome, funded prolific quattrocento and cinquecento artists such as Raphael, Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci.[36][37]

Political intrigue within the Church in the mid-14th century caused the Great Schism. During this forty-year period, two popes - one in Avignon and one in Rome - claimed rulership over the Church. Although the schism was eventually healed in 1417, the papacy's spiritual authority had suffered greatly.[38] The Church's power was further weakened by the Protestant Reformation of Martin Luther, a result of the lack of reform within the Church. The Reformation also damaged the Holy Roman Empire's power, as German princes became divided between Catholic, Protestant and Calvinist faiths.[39] This eventually led to the Thirty Years War (1618-1648), which crippled the Holy Roman Empire and devastated much of Germany. In the aftermath of the Peace of Westphalia, France rose to predominance within Europe.[40]

The Renaissance and the New Monarchs marked the start of an Age of Discovery, a period of exploration, invention, and scientific development. In the 15th century, Portugal and Spain, the two greatest naval powers of the time, took the lead in exploring the world.[41] Christopher Columbus discovered the New World in the 1498, and soon after the Spanish and Portuguese began establishing colonial empires in the Americas.[42] France, the Netherlands and England soon followed in building large colonial empires with vast holdings in Africa, the Americas, and Asia.

18th and 19th centuries

The Enlightenment arose during the 18th century as a powerful intellectual movement in which scientific and reason-based thought began to emerge.[43] The French Revolution grew out of the Enlightenment and bourgeoisie discontent with the aristocracy and clergy's monopoly on political power. The Revolution succeeded at toppling the monarchy and the upper classes and established a French republic.[44] The Napoleonic Wars, which took place over the course of fifteen years, marked the end of the French Revolution. During the Napoleonic Wars, Napoleon Bonaparte rose to power and established a French Empire that grew to encompass almost all of Europe before collapsing.[45]

But French armies brought with them the concepts of liberalism, nationalism and a new legal system, all of which had a powerful impact on the lower and middle classes of other European nations.[44] The Congress of Vienna was convened after Napoleon's downfall. It established a new balance of power in Europe centered on the five "great powers": Great Britain, France, Prussia, Austria and Russia.[46] This balance would remain in place until the Revolutions of 1848, during which liberal uprisings affected all of continental Europe except for Russia. The revolutions were eventually put down by more conservative elements and few reforms resulted.[47]

The Industrial Revolution started in Great Britain in the late 18th century. Although it started mainly as a technological leap, it soon led to reforms in social and economic spheres as well.[48] The Industrial Revolution led to the formation of the first child labor laws and organized labor movements. Karl Marx also began writing about socialism during this time.[49]

20th century and present

The first half of the 20th century was dominated by two world wars and an economic depression. World War I, which was fought between 1914 and 1918, was an incredibly destructive conflict. It started when the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated by a Serbian nationalist.[50] Through complicated series of treaties, all the nations in Europe were drawn into the war, during which between 10 and 13 million people lost their lives.[51] World War I changed the map of Europe. Russia was plunged into the Russian Revolution, after which it became the Soviet Union.[52] Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire collapsed completely, and many other nations had their borders redrawn or eliminated altogether. The Treaty of Versailles was harsh towards Germany, upon whom it placed full responsibility for the war and imposed heavy sanctions.[53]

The collapse of the New York Stock Exchange in 1929 sent economic shockwaves throughout the global economy and plunged the world into the Great Depression during the 1930s. Anti-democratic movements strengthened in Central and Eastern Europe during the economic crisis, placing fascist leaders Adolf Hitler of Nazi Germany and Benito Mussolini of Italy in power.[54] Hitler's 1939 invasion of Poland marked the beginning of World War II in Europe, which lasted until the fall of Berlin in 1945. The war was the largest and most destructive in human history, with 60 million dead across the world.[55]

World War II's destruction ended European dominance in world affairs, replaced by the now-superpower United States and the Soviet Union, who were soon locked in the fifty-year Cold War. An "iron curtain" divided the continent into two rival blocs, with NATO in Western Europe and the Warsaw Pact in Eastern Europe.[56] The Cold War ended in 1991 with the fall of the Soviet Union. Elsewhere in the world, decolonization led to independence for nations in Asia and Africa as the old European colonial empires crumbled.[57] European integration accelerated beginning in the 1990s, as the European Union expanded to include 27 European nations.[58]

Geography and extent

Physiographically, Europe is the northwestern constituent of the larger landmass known as Eurasia, or Africa-Eurasia: Asia occupies the eastern bulk of this continuous landmass and all share a common continental shelf. Europe's eastern frontier is now commonly delineated by the Ural Mountains in Russia. The first century AD geographer Strabo, [59] took the Tanais River to be the boundary, as did early Judaic sources. The southeast boundary with Asia is not universally defined. Most commonly the Ural or, alternatively, the Emba River serve as possible boundaries. The boundary continues to the Caspian Sea, the crest of the Caucasus Mountains or, alternatively, the Kura River in the Caucasus, and on to the Black Sea; the Bosporus, the Sea of Marmara, and the Dardanelles conclude the Asian boundary. The Mediterranean Sea to the south separates Europe from Africa. The western boundary is the Atlantic Ocean; Iceland, though nearer to Greenland (North America) than mainland Europe, is generally included in Europe. There is ongoing debate on where the geographical centre of Europe is. For detailed description of the boundary between Asia and Europe see transcontinental nation.

Because of sociopolitical and cultural differences, there are various descriptions of Europe's boundary; in some sources, some territories are not included in Europe, while other sources include them. For instance, geographers from Russia and other post-Soviet states generally include the Urals in Europe while including Caucasia in Asia. Similarly, numerous geographers consider Azerbaijan's and Armenia's southern border with Iran and Turkey's southern and eastern border with Syria, Iraq and Iran as the boundary between Asia and Europe because of political and cultural reasons. In the same way, despite being close to Asia and Africa, the Mediterranean islands of Cyprus and Malta are considered part of Europe.

Physical geography

Land relief in Europe shows great variation within relatively small areas. The southern regions, however, are more mountainous, while moving north the terrain descends from the high Alps, Pyrenees and Carpathians, through hilly uplands, into broad, low northern plains, which are vast in the east. This extended lowland is known as the Great European Plain, and at its heart lies the North German Plain. An arc of uplands also exists along the north-western seaboard, which begins in the western parts of Britain and Ireland, and then continues along the mountainous, fjord-cut, spine of Norway.

This description is simplified. Sub-regions such as the Iberian Peninsula and the Italian Peninsula contain their own complex features, as does mainland Central Europe itself, where the relief contains many plateaus, river valleys and basins that complicate the general trend. Sub-regions like Iceland, Britain and Ireland are special cases. The former is a land unto itself in the northern ocean which is counted as part of Europe, while the latter are upland areas that were once joined to the mainland until rising sea levels cut them off.

-

Mount Elbrus, the highest mountain in Europe.

-

Tara River Canyon, the deepest canyon in Europe is located in Montenegro.

-

Shoreline in Mediterranean Greece.

-

Europe's longest river, the Volga River, at Yaroslavl.

-

Aletsch Glacier, the largest glacier in Continental Europe, is located in Switzerland

Biodiversity

Having lived side-by-side with agricultural peoples for millennia, Europe's animals and plants have been profoundly affected by the presence and activities of man. With the exception of Fennoscandia and northern Russia, few areas of untouched wilderness are currently found in Europe, except for various national parks.

The main natural vegetation cover in Europe is mixed forest. The conditions for growth are very favourable. In the north, the Gulf Stream and North Atlantic Drift warm the continent. Southern Europe could be described as having a warm, but mild climate. There are frequent summer droughts in this region. Mountain ridges also affect the conditions. Some of these (Alps, Pyrenees) are oriented east-west and allow the wind to carry large masses of water from the ocean in the interior. Others are oriented south-north (Scandinavian Mountains, Dinarides, Carpathians, Apennines) and because the rain falls primarily on the side of mountains that is oriented towards sea, forests grow well on this side, while on the other side, the conditions are much less favourable. Few corners of mainland Europe have not been grazed by livestock at some point in time, and the cutting down of the pre-agricultural forest habitat caused disruption to the original plant and animal ecosystems.

Eighty to ninety per cent of Europe was once covered by forest. It stretched from the Mediterranean Sea to the Arctic Ocean. Though over half of Europe's original forests disappeared through the centuries of deforestation, Europe still has over one quarter of its land area as forest, such as the taiga of Scandinavia and Russia, mixed rainforests of the Caucasus and the Cork oak forests in the western Mediterranean. During recent times, deforestation has been slowed and many trees have been planted. However, in many cases monoculture plantations of conifers have replaced the original mixed natural forest, because these grow quicker. The plantations now cover vast areas of land, but offer poorer habitats for many European forest dwelling species which require a mixture of tree species and diverse forest structure. The amount of natural forest in Western Europe is just 2–3% or less, in European Russia 5–10%. The country with the smallest percentage of forested area (excluding the micronations) is Iceland (2%), while the most forested country is Finland(72%).

In temperate Europe, mixed forest with both broadleaf and coniferous trees dominate. The most important species in central and western Europe are beech and oak. In the north, the taiga is a mixed spruce-pine-birch forest; further north within Russia and extreme northern Scandinavia, the taiga gives way to tundra as the Arctic is approached. In the Mediterranean, many olive trees have been planted, which are very well adapted to its arid climate; Mediterranean Cypress is also widely planted in southern Europe. The semi-arid Mediterranean region hosts much scrub forest. A narrow east-west tongue of Eurasian grassland (the steppe) extends eastwards from Ukraine and southern Russia and ends in Hungary and traverses into taiga to the north.

Glaciation during the most recent ice age and the presence of man affected the distribution of European fauna. As for the animals, in many parts of Europe most large animals and top predator species have been hunted to extinction. The woolly mammoth was extinct before the end of the Neolithic period. Today wolves (carnivores) and bears (omnivores) are endangered. Once they were found in most parts of Europe. However, deforestation caused these animals to withdraw further and further. By the Middle Ages the bears' habitats were limited to more or less inaccessible mountains with sufficient forest cover. Today, the brown bear lives primarily in the Balkan peninsula, Scandinavia, and Russia; a small number also persist in other countries across Europe (Austria, Pyrenees etc.), but in these areas brown bear populations are fragmented and marginalised because of the destruction of their habitat. In addition, polar bears may be found on Svalbard, a Norwegian archipelago far north of Scandinavia. The wolf, the second largest predator in Europe after the brown bear, can be found primarily in Eastern Europe and in the Balkans, with a handful of packs in pockets of Western Europe (Scandinavia, Spain, etc.).

Other important European carnivores are Eurasian lynx, European wild cat, foxes (especially the red fox), jackal and different species of martens, hedgehogs, different species of reptiles snakes (vipers, grass snake…), different birds (owls, hawks and other birds of prey).

Important European herbivores are snails, amphibian larvae, fish, different birds, and mammals, like rodents, deer and roe deer, boars, and living in the mountains, marmots, steinbocks, chamois among others.

Sea creatures are also an important part of European flora and fauna. The sea flora is mainly phytoplankton. Important animals that live in European seas are zooplankton, molluscs, echinoderms, different crustaceans, squids and octopuses, fish, dolphins, and whales.

Biodiversity is protected in Europe through the Council of Europe Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats (Bern Convention), which has also been signed by the European Community as well as non-European states.

Demographics

Since the Renaissance and the Age of Discovery, Europe has had a major influence in culture, economics and social movements in the world. European demographics are important not only historically, but also in understanding current international relations and population issues.

Some current and past issues in European demographics have included religious emigration, race relations, economic immigration, a declining birth rate and an aging population. In some countries, such as the Republic of Ireland and Poland, access to abortion is currently limited; in the past, such restrictions and also restrictions on artificial birth control were commonplace throughout Europe. Furthermore, three European countries (The Netherlands, Belgium and Switzerland) have allowed a limited form of voluntary euthanasia for some terminally ill people.

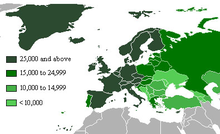

In 2005 the population of Europe was estimated to be 728 million according to the United Nations, which is slightly more than one-ninth of the world's population. A century ago Europe had nearly a quarter of the world's population. The population of Europe has grown in the past century, but in other areas of the world (in particular Africa and Asia) the population has grown far more quickly.[60] According to UN population projection (medium variant), Europe's share will fall to 7% in 2050, numbering 653 million.[61] Within this context, significant disparities exist between religions in relation to fertility rates. The average number of children per female of child bearing age is 1.52. According to some sources,[62][63] this rate is higher among Muslims. In 2005 the EU had an overall net gain from immigration of 1.8 million people, despite having one of the highest population densities in the world. This accounted for almost 85% of Europe's total population growth.[64]

Political geography

Territories and regions

The countries in this table are categorised according to the scheme for geographic subregions used by the United Nations, and data included are per sources in cross-referenced articles. Where they differ, provisos are clearly indicated.

According to different definitions, such as consideration of the concept of Central Europe, the following territories and regions may be subject to various other categorisations.

| Name of region[a] and territory, with flag |

Area (km²) |

Population (1 July, 2002 est.) |

Population density (per km²) |

Capital |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern Europe: | ||||

| 207,600 | 10,335,382 | 49.8 | Minsk | |

| 110,910 | 7,621,337 | 68.7 | Sofia | |

| 78,866 | 10,256,760 | 130.1 | Prague | |

| 93,030 | 10,075,034 | 108.3 | Budapest | |

| 33,843 | 4,434,547 | 131.0 | Chişinău | |

| 312,685 | 38,625,478 | 123.5 | Warsaw | |

| 238,391 | 21,698,181 | 91.0 | Bucharest | |

| 3,960,000 | 106,037,143 | 26.8 | Moscow | |

| 48,845 | 5,422,366 | 111.0 | Bratislava | |

| 603,700 | 48,396,470 | 80.2 | Kiev | |

| Northern Europe: | ||||

| 1,552 | 26,008 | 16.8 | Mariehamn | |

| 43,094 | 5,368,854 | 124.6 | Copenhagen | |

| 45,226 | 1,415,681 | 31.3 | Tallinn | |

| 1,399 | 46,011 | 32.9 | Tórshavn | |

| 336,593 | 5,157,537 | 15.3 | Helsinki | |

| 78 | 64,587 | 828.0 | St Peter Port | |

| 103,000 | 307,261 | 2.7 | Reykjavík | |

| 70,280 | 4,234,925 | 60.3 | Dublin | |

| 572 | 73,873 | 129.1 | Douglas | |

| 116 | 89,775 | 773.9 | Saint Helier | |

| 64,589 | 2,366,515 | 36.6 | Riga | |

| 65,200 | 3,601,138 | 55.2 | Vilnius | |

| 324,220 | 4,525,116 | 14.0 | Oslo | |

Mayen Islands (Norway) |

62,049 | 2,868 | 0.046 | Longyearbyen |

| 449,964 | 9,090,113 | 19.7 | Stockholm | |

| 244,820 | 61,100,835 | 244.2 | London | |

| Southern Europe: | ||||

| 28,748 | 3,600,523 | 125.2 | Tirana | |

| 468 | 68,403 | 146.2 | Andorra la Vella | |

| 51,129 | 4,448,500 | 77.5 | Sarajevo | |

| 56,542 | 4,437,460 | 77.7 | Zagreb | |

| 5.9 | 27,714 | 4,697.3 | Gibraltar | |

| 131,940 | 10,645,343 | 80.7 | Athens | |

| 301,230 | 58,751,711 | 191.6 | Rome | |

| 25,333 | 2,054,800 | 81.1 | Skopje | |

| 316 | 397,499 | 1,257.9 | Valletta | |

| 13,812 | 616,258 | 44.6 | Podgorica | |

| 91,568 | 10,084,245 | 110.1 | Lisbon | |

| 61 | 27,730 | 454.6 | San Marino | |

| 88,361 | 9,663,742 | 109.4 | Belgrade | |

| 20,273 | 1,932,917 | 95.3 | Ljubljana | |

| 504,851 | 45,061,274 | 89.3 | Madrid | |

| 0.44 | 900 | 2,045.5 | Vatican City | |

| Western Europe: | ||||

| 83,858 | 8,169,929 | 97.4 | Vienna | |

| 30,510 | 10,274,595 | 336.8 | Brussels | |

| 547,030 | 59,765,983 | 109.3 | Paris | |

| 357,021 | 83,251,851 | 233.2 | Berlin | |

| 160 | 32,842 | 205.3 | Vaduz | |

| 2,586 | 448,569 | 173.5 | Luxembourg | |

| 1.95 | 31,987 | 16,403.6 | Monaco | |

| 41,526 | 16,318,199 | 393.0 | Amsterdam | |

| 41,290 | 7,507,000 | 176.8 | Bern | |

| Central Asia: | ||||

| 150,000 | 600,000 | 4.0 | Astana | |

| Western Asia:[k] | ||||

| 7,110 | 175,200 | 24.6 | Baku | |

| 2,000 | 37,520 | 18.8 | Tbilisi | |

| 24,378 | 11,044,932 | 453.1 | Ankara | |

| Total | 10,176,246[o] | 709,608,850[p] | 69.7 | |

Economy

As a continent, the economy of Europe is currently the largest on Earth. The European Union, or EU, an intergovernmental body composed of most of the European states, is one of the two largest in the world. Of the member states in the EU, Germany has the largest national economy. Thirteen EU countries share a common unit of currency, the euro. Major economic sectors in Europe include agriculture, manufacturing, and investment. The majority of the EU's trade is with the United States, China, India, Russia and non-member European states.

Languages and cultures

There are several linguistic groups widely recognised in Europe. These sometimes (but not always) coincide with cultural and historical connections between the various nations, though in other cases religion is considered a more significant distinguishing factor.

Multiligualism and the protection of regional and minority languages are recognised political goals in Europe today. The Council of Europe Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities and the Council of Europe's European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages set up a legal framework for language rights in Europe.

Romance languages

Romance languages are spoken more or less in south-western Europe, as well as Romania and Moldova which are situated in Eastern Europe. This area consists of: Andorra, Italy, Portugal, France (excluding parts of Nord and Alsace), Spain, Romania, Moldova, French-speaking Belgium (Wallonia, partly Brussels), French-speaking Switzerland (Romandy), Italian-speaking Switzerland, Italian-speaking Croatia (part of Istria), and Romansch-speaking Switzerland. All Romance languages are principally derived from the Roman language, Latin, as designated.

Germanic languages

Germanic languages are spoken more or less in north-western Europe and some parts of central Europe. This region consists of: Norway, Sweden, Germany, Austria, the United Kingdom, the Republic of Ireland, Denmark, the Netherlands, Dutch-speaking Belgium (Flanders, partly Brussels and the German-speaking areas east of Wallonia), Austria, Hungary (the City of Sopron), Slovakia (Bratislava), Transylvania (Romania), Liechtenstein, 68-74% of Switzerland, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Luxemburg, Poland (areas in Silesia), Pomerania, East Prussia, France (Alsace-Lorraine, and Nord-Pas de Calais), the Swedish-speaking municipalities of Finland, and the Alto Adige and South Tirol in Italy.

Celtic languages

The Celtic languages once stretched across western and central Europe and into Anatolia, but today they are largely limited to the western fringe of the Celtic nations: Ireland, Scotland, the Isle of Man, Wales, Cornwall, and Brittany. The Continental Celtic languages, including Gaulish and Celtiberian, died out by the sixth century; only the Insular Celtic languages—the Goidelic languages (Irish, Scottish Gaelic, Manx) and the Brythonic languages (Welsh, Breton, Cornish)—have survived into modern times.

Slavic languages

Slavic languages are spoken in Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. This area consists of: Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, regions of Saxony and Brandenburg in Germany (Sorbs), the Republic of Macedonia, some parts of Northern Greece, Montenegro, Poland, Russia, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, regions of Moldova (including the territory of Transnistria), and Ukraine.

Uralic languages

The Uralic languages are divided into three main groups, two of which have representatives in Europe. The Finno-Permic languages are spoken in Finland, Estonia, and parts of Sweden, Norway, Latvia, and European Russia while the Ugric languages are spoken in Hungary and parts of Romania, Slovakia, Serbia, Ukraine, and Siberian Russia. These two groups comprise the Finno-Ugric branch of the Uralic language family.

Turkic languages

Turkic languages are spoken as the main language in Turkey and Azerbaijan and as a minority language in parts of Cyprus, Bulgaria, Serbia, Greece, Russia, Republic of Macedonia, Moldova, Ukraine, the Caucasus, and in Turkish diaspora communities in several other European countries (most notably Germany, Sweden, France, Belgium, and the Netherlands).

Baltic languages

Baltic languages are spoken in Lithuania and Latvia. Estonia's national language is part of the Finno-Ugric family even though it is a Baltic state geographically.

Other languages

Outside of these seven main linguistic groups one can find:

- The Greek language, one of the oldest European languages spoken in Greece, Cyprus, and parts of Turkey, Albania, Georgia, Armenia and Italy, and in Greek diaspora communities in several other European countries (most notably Germany).

- The Ossetic language, an Iranian language spoken in North Ossetia-Alania and South Ossetia (or Ossetia, a region on the slopes of the Caucasus mountains on the borders of Russia and Georgia).

- The Armenian language, an Indo-European language is spoken in Armenia and around Eastern Europe with a variety of dialects.

- The North Caucasian, a group that includes ethnic groups throughout the Caucasus region (both North and South). North Caucasian languages are divided into two main branches: Northeast Caucasian and Northwest Caucasian. This group includes Abkhaz, Chechens, Ingush, Bats, and a number of other smaller ethnic groups that reside in the Caucasus.

- The South Caucasian, or Kartvelian languages, a group that includes the Georgian language.

- The Maltese language, a heavily Romanticised Semitic language, descended from Maghrebi Arabic, is spoken in Malta. Unlike other Semitic languages, Maltese is written in the Roman alphabet.

- The Basque language is spoken in the Basque Country, i.e. parts of southern France and northern Spain.

- The Albanian language, which, like the Greek language, forms its own independent branch of the Indo-European language family with no close living relatives. Major Albanian-speaking communities outside Albania live in Kosovo (Serbia), the Republic of Macedonia, Montenegro, Greece, Turkey, and southern Italy.[65]

- The Mongolic branch of the Altaic phylum is represented in Europe by the Kalmyk language, which is spoken by the Kalmyk people in Kalmykia, a constituent republic of the Russian Federation.

Religions

The most prevalent religions of Europe are the following:

- Christianity

- Roman Catholicism: Countries or areas with significant Catholic populations are Andorra, Austria, west Belarus, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, the Czech Republic, France, south and west Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latgale region in Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Monaco, south Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, San Marino, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, central and south Switzerland, and Vatican City. There are also large Catholic minorities in Great Britain: England, Scotland, Wales and most European countries.

- Eastern-Rite Catholicism also known as "Uniatism", is found in western Ukraine, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Greece, Armenia, Hungary, the Republic of Macedonia, Romania, Serbia and Slovakia, southern Italy (Sardinia and Sicily) and Corsica, France.

- Orthodox Christianity: The countries with significant Orthodox populations are Greece, Russia, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Republic of Macedonia, Moldova, Montenegro, Armenia, Serbia, Ukraine, Romania, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Georgia, easternmost Hungary, a small minority in Southern Italy, Kazakhstan, sizable minorities in Albania, Latvia and Lithuania, small minority in Poland, Finland (Karelia).

- Protestantism: Countries with significant Protestant populations include Denmark, Estonia, Finland, north and east Germany, Iceland, Latvia, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden; east, north and west Switzerland; and the United Kingdom. There are significant minorities in France, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Ireland, and a small minority in Poland.

- Islam: Countries with significant Muslim population are Albania, Azerbaijan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Montenegro, several republics of Russia, Serbia, Turkey, Crimea in Ukraine, and, from Western Europe, France. [66]

Other religions are practiced by smaller groups in Europe, including:

- Judaism primarily in France, Germany, the United Kingdom, Russia. At one time Judaism was practiced widely throughout the European continent, though it has dwindled in numbers since the expulsion, extermination, and exodus of Jews during the later portion of the second millennium.

- Hinduism mainly among Indian immigrants in the United Kingdom. In 1998 there were an estimated 1,382,000 Hindu adherents in Europe alone [2].

- Buddhism thinly spread throughout Europe.

- Indigenous European pagan traditions and beliefs, many countries (a fast-growing neopagan movement in France, Germany, Ireland and United Kingdom is noted), and one neopagan faith Asatru recognized as a minority religion in Iceland (since 1973), Norway and Sweden.

- Rastafari, communities in the United Kingdom, France, Spain, Portugal, Italy and elsewhere.

- Sikhism and Jainism, small membership rolls, both mainly among Indian immigrants in the United Kingdom.

- Voodoo, mainly among black Caribbean and West African immigrants in the United Kingdom and France.

- Traditional African Religions (including Muti), mainly in the United Kingdom and France.

- Other religions with few (or under a million) adherents in Europe: Animism, Christian Scientists, Eco-religion, Gnosticism, Paganism, Jehovah's Witnesses, Mennonites, Moravian Church, Mormonism or Latter-day Saints, Pantheism, Polytheism, theological relativism, Scientology, Seventh-day Adventists, Universal Life Church, Unitarians, Wiccan, and Zoroastrianism.

Millions of Europeans profess no religion or are atheist, agnostic or humanist. The largest non-confessional populations (as a percentage) are found in the Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and the former soviet countries of Belarus, Estonia, Russia and Ukraine, although most former communist countries have significant non-confessional populations.

Official religions

A number of countries in Europe have official religions, including Liechtenstein, Malta, Monaco, the Vatican City (Catholic), Greece (Eastern Orthodox), Denmark, Iceland, and Norway (Lutheran). In Switzerland, some cantons are officially Catholic, others Reformed Protestant. Some Swiss villages even have their religion as well as the village name written on the signs at their entrances.

Georgia has no established church, but the Georgian Orthodox Church enjoys de facto privileged status. In Finland, both the Finnish Orthodox Church and the Lutheran Church are official. England, a part of the UK, has Anglicanism as its official religion. Scotland, another part of the UK, has Presbyterianism as its national church, but it is no longer "official", and in Sweden, the national church is Lutheranism, but it is also no longer "official". Azerbaijan, France, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Spain and Turkey are officially "secular".

See also

Lists and tables

- General

- Demographics

- Economics

- Politics

Notes

^ a: Continental regions as per UN categorisations/map. Depending on definitions, various territories cited below may be in one or both of Europe and Asia, Africa, or Oceania.

^ b: Includes Transnistria, a region that has declared, and de facto achieved, independence; however, it is not recognised de jure by sovereign states.

^ c: Russia is generally considered a transcontinental country in Eastern Europe (UN region) and Asia, with European territory west of the Ural Mountains and both the Ural and Emba rivers; population and area figures are for European portion only.

^ d: Guernsey, Isle of Man and Jersey are Crown dependencies of the United Kingdom.

^ e: Montenegro declared independence from the union of Serbia and Montenegro on June 3, 2006.

^ f: Figures for Portugal include the Azores west of Portugal but exclude the Madeira Islands, west of Morocco in Africa.

^ g: Figures for Serbia include Kosovo and Metohia, a province administrated by the UN (UNMIK) as per Security Council Resolution 1244.

^ h: Figures for France include only metropolitan France: some politically integral parts of France are geographically located outside Europe.

^ i: Netherlands population for July 2004. Population and area details include European portion only: Netherlands and two entities outside Europe (Aruba and the Netherlands Antilles, in the Caribbean) constitute the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Amsterdam is the official capital, while The Hague is the administrative seat.

^ j: Kazakhstan is sometimes considered a transcontinental country in Central Asia (UN region) and Eastern Europe, with European territory west of the Ural Mountains and both the Ural and Emba rivers; area figures are for European portion out of total.

^ k: Armenia and Cyprus are sometimes considered transcontinental countries: both are physiographically in Western Asia but have historical and sociopolitical connections with Europe.

^ l: Azerbaijan is often considered a transcontinental country in Western Asia (UN region) and Eastern Europe; population and area figures are for European portion (north of the crest of the Caucasus and the Kura River) out of total. This excludes the exclave of Nakhchivan and Nagorno-Karabakh (a region that has declared, and de facto achieved, independence; however, it is not recognised de jure by sovereign states).

^ m: Georgia is often considered a transcontinental country in Western Asia (UN region) and Eastern Europe; population and area figures are for European portion (north of the crest of the Caucasus and the Kura River) out of total. Also includes Abkhazia and South Ossetia, two regions that have declared, and de facto achieved, independence; however, they are not recognised de jure by sovereign states.

^ n: Turkey is generally considered a transcontinental country in Western Asia (UN region) and Southern Europe: the region of Rumelia (Trakya)—which includes the provinces of Edirne, Kırklareli, Tekirdağ, and the western parts of the Çanakkale and Istanbul Provinces—is west and north of the Bosporus and the Dardanelles; population and area figures are for European portion (including all of Istanbul) out of total population.

^ o: The total area figure includes only European portions of transcontinental countries.

^ p: The total population figure includes only European portions of transcontinental countries.

Citations

- ^ "Etymonline: European". Retrieved 2006-09-10.

- ^ Davidson, Roderic H. (1960). "Where is the Middle East?". Foreign Affairs. 38: p. 665–675.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ A. Vekua, D. Lordkipanidze, G. P. Rightmire, J. Agusti, R. Ferring, G. Maisuradze; et al. (2002). "A new skull of early Homo from Dmanisi, Georgia". Science. 297: 85–9.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ The million year old tooth from Atapuerca, Spain, found in June 2007

- ^ National Geographic, 21.

- ^ Atkinson, R J C, Stonehenge (Penguin Books, 1956)

- ^ a b National Geographic, 76.

- ^ National Geographic, 82.

- ^ Template:Harvard reference

- ^ Template:Harvard reference

- ^ Pedersen, Olaf. Early Physics and Astronomy: A Historical Introduction. 2nd edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- ^ National Geographic, 76-77.

- ^ McEvedy, Colin (1961), The Penguin Atlas of Medieval History, Penguin Books

- ^ National Geographic, 123.

- ^ Foster, Sally M., Picts, Gaels, and Scots: Early Historic Scotland. Batsford, London, 2004. ISBN 0-7134-8874-3

- ^ Renaissance or Prenaissance, Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol. 4, No. 1. (Jan., 1943), pp. 69-74.

- ^ Norman F. Cantor, The Medieval World 300 to 1300.

- ^ National Geographic, 140

- ^ National Geographic, 143-145.

- ^ National Geographic, 162.

- ^ National Geographic, 166.

- ^ National Geographic, 210.

- ^ National Geographic, 135.

- ^ National Geographic, 211.

- ^ a b c National Geographic, 158.

- ^ National Geographic, 186.

- ^ National Geographic, 192.

- ^ National Geographic, 199.

- ^ a b National Geographic, 159.

- ^ National Geographic, 223.

- ^ Weiss, Roberto (1969) The Renaissance Discovery of Classical Antiquity, ISBN 1-597-40150-1

- ^ cob Burckhardt|Burckhardt, Jacob (1878), The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy, trans S.G.C Middlemore, republished in 1990 ISBN 0-14-044534-X

- ^ National Geographic, 254.

- ^ Jensen, De Lamar (1992), Renaissance Europe, ISBN 0-395-88947-2

- ^ Levey, Michael (1967), Early Rennaissance, Penguin Books

- ^ National Geographic, 292.

- ^ Levey, Michael (1971), High Rennaissance, Penguin Books

- ^ National Geographic, 193.

- ^ National Geographic, 256-257.

- ^ National Geographic, 269.

- ^ National Geographic, 296.

- ^ National Geographic, 338.

- ^ National Geographic, 255.

- ^ a b National Geographic, 350.

- ^ National Geographic, 360.

- ^ National Geographic, 367.

- ^ National Geographic, 371-373.

- ^ National Geographic, 368.

- ^ National Geographic, 369.

- ^ National Geographic, 407.

- ^ National Geographic, 440.

- ^ National Geographic, 480.

- ^ National Geographic, 443.

- ^ National Geographic, 438.

- ^ National Geographic, 439.

- ^ National Geographic, 530.

- ^ National Geographic, 534.

- ^ National Geographic, 535.

- ^ Strabo Geography 11.1

- ^ UNPP, 2004 Revision World Population Prospects: The 2004 Revision Population Database. United Nations Population Division, 2005. Last accessed October 25, 2006.

- ^ http://esa.un.org/unpp/p2k0data.asp

- ^ Brookings Institute Report

- ^ http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/europe/4385768.stm

- ^ Europe: Population and Migration in 2005

- ^ [1]

- ^ Muslims in Europe: BBC Country guide

References

- National Geographic (2005). National Geographic Visual History of the World. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society. ISBN 0-7922-3695-5.

External links

- Template:Wikitravel

- "Europe". The Columbia Gazetteer of the World Online. 2005. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Europe at Night at NASA Earth Observatory

- Council of Europe

- European Union