Ali

| ʿAli ibn Abi Talib | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commander of the Faithful (Amir al-Mu'minin) | |||||

Caliph Ali's empire in 661, light green shows Ali's claim but not controlled. | |||||

| Reign | 656–661[1] | ||||

| Predecessor | Muhammad as Shia Imam/Uthman Ibn Affan as Caliph | ||||

| Successor | Hasan[2]/Muawiya I | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Wives |

| ||||

| Issue | Hasan Husayn Zaynab (See:Descendants of Ali ibn Abi Talib ) | ||||

| |||||

| House | Ahl al-Bayt Banu Hashim | ||||

| Father | Abu Talib | ||||

| Mother | Fatima bint Asad | ||||

Alī ibn Abī Ṭālib ([undefined] Error: {{Lang-xx}}: no text (help), [ʕaliː ibn ʔæbiː t̪ˤɑːlib]; 13th Rajab, 24 BH–21st Ramaḍān, 40 AH; approximately October 23, 598 or 600[3] or March 17, 599 – January 27, 661[4]) was the cousin and son-in-law of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, and ruled over the Islamic Caliphate from 656 to 661. Sunni Muslims consider Ali the fourth and final of the Rashidun (rightly guided Caliphs), while Shi'a Muslims regard Ali as the first Imam and consider him and his descendants the rightful successors to Muhammad, all of which are members of the Ahl al-Bayt, the household of Muhammad. This disagreement split the Ummah (Muslim community) into the Sunni and Shi'a branches.[1]

Most records do indicate that during Muhammad's time, Ali was the only person born in the Kaaba sanctuary in Mecca, the holiest place in Islam.[5] His father was Abu Talib ibn Abd al-Muttalib and his mother was Fatima bint Asad,[1] but he was raised in the household of Muhammad, who himself was raised by Abu Talib, Muhammad's uncle. When Muhammad reported receiving a divine revelation, Ali was the first male to accept his message, dedicating his life to the cause of Islam.[4][6][7][8]

Ali migrated to Medina shortly after Muhammad did. Once there Muhammad told Ali that God had ordered him to give his daughter, Fatimah, to Ali in marriage.[1] For the ten years that Muhammad led the community in Medina, Ali was extremely active in his service, leading parties of warriors on battles, and carrying messages and orders. Ali took part in the early raids against caravans from Mecca and later in almost all the battles fought by the early Muslim community.

Ali was appointed caliph by the Sahaba (Muhammad's companions) in Medina after the assassination of the third caliph, Uthman ibn Affan.[9][10] He encountered defiance and civil war during his reign. In 661, Ali was attacked while praying in the mosque of Kufa, dying a few days later.[11][12][13]

In Muslim culture, Ali is respected for his courage, knowledge, belief, honesty, unbending devotion to Islam, deep loyalty to Muhammad, equal treatment of all Muslims and generosity in forgiving his defeated enemies, and therefore is central to mystical traditions in Islam such as Sufism. Ali retains his stature as an authority on Qur'anic exegesis, Islamic jurisprudence and religious thought.[14] Ali holds a high position in almost all Sufi orders which trace their lineage through him to Muhammad. Ali's influence has thus continued throughout Islamic history.[1]

In Mecca

| Part of a series on |

| Ali |

|---|

|

Birth and childhood

Ali's father Abu Talib ibn ‘Abd al-Muttalib was the custodian of the Kaaba and a sheikh of the Banu Hashim, an important branch of the powerful Quraysh tribe. He was also an uncle of Muhammad. Ali's mother, Fatima bint Asad, also belonged to Banu Hashim, making Ali a descendant of Ishmael, the son of Ibrahim or Abraham.[15]

Many sources, including all Shi'a records, attest that during Mohammad's time Ali was the only person born inside the Kaaba in the city of Mecca, where he stayed with his mother for three days. However, some sources contend that he was born beside the Kaaba rather than inside it. According to a tradition, Muhammad was the first person whom Ali saw as he took the newborn in his hands. Muhammad named him Ali, meaning "the exalted one".[1][16]

Muhammad had a close relationship with Ali's parents. When Muhammad was orphaned and later lost his grandfather Abdul Muttalib, Ali's father took him into his house.[1] Ali was born two or three years after Muhammad married Khadijah bint Khuwaylid.[17] When Ali was five or six years old, a famine occurred in and around Mecca, affecting the economic conditions of Ali's father, who had a large family to support. Muhammad took Ali into his home to raise him.[1][6][18]

Acceptance of Islam

The second period of Ali's life begins in 610 when he declared Islam at age 10 and ends with the Hijra of Muhammad to Medina in 622.[1] When Muhammad reported that he had received a divine revelation, Ali, then only about ten years old, believed him and professed to Islam.[1][4][6][7] According to Ibn Ishaq and some other authorities, Ali was the first male to embrace Islam. Tabari adds other traditions making the similar claim of being the first Muslim in relation to Zayd or Abu Bakr.[19] Some historians and scholars believe Ali's conversion is not worthy enough to consider him the first male Muslim because he was a child at the time.[20]

Shi'a doctrine asserts that in keeping with Ali's divine mission, he accepted Islam before he took part in any pre-Islamic Meccan traditional religion rites, regarded by Muslims as polytheistic (see shirk) or paganistic. Hence the Shi'a say of Ali that his face is honored — that is, it was never sullied by prostrations before idols.[6] The Sunnis also use the honorific Karam Allahu Wajhahu, which means "God's Favor upon his Face."

The reason his acceptance is often not called a conversion, is because he was never an idol worshiper like the people of Mecca. He was known to have broken idols in the mold of Abraham and asked people why they worshiped something they made themselves. Ali's grandfather, it is acknowledged without controversy, along with some members of the Banu Hashim clan, were Hanifs, followers of a monotheistic belief system, prior to the coming of Islam.

After declaration of Islam

For three years Muhammad invited people to Islam in secret, then he started inviting publicly. When, according to the Quran, he was commanded to invite his closer relatives to come to Islam[21] he gathered the Banu Hashim clan in a ceremony.

According to al-Tabari, Ibn Athir and Abu al-Fida, Muhammad announced at invitational events that whoever assisted him in his invitation would become his brother, trustee and successor. Only Ali, who was thirteen or fourteen years old, stepped forward to help him. This invitation was repeated three times, but Ali was the only person who answered Muhammad. Upon Ali's constant and only answer to his call, Muhammad declared that Ali was his brother, inheritor and vice-regent and people must obey him. Most of the adults present were uncles of Ali and Muhammad, and Abu Lahab laughed at them and declared to Abu Talib ibn ‘Abd al-Muttalib|Abu Talib that he must bow down to his own son, as Ali was now his Emir[22] This event is known as the Hadith of Warning.

During the persecution of Muslims and boycott of the Banu Hashim in Mecca, Ali stood firmly in support of Muhammad.[23]

Migration to Medina

In 622, the year of Muhammad's migration to Yathrib (now Medina), Ali risked his life by sleeping in Muhammad's bed to impersonate him and thwart an assassination plot so that Muhammad could escape in safety.[1][6][24] This night is called Laylat al-Mabit. According to some hadith, a verse was revealed about Ali concerning his sacrifice on the night of Hijra which says, "And among men is he who sells his nafs (self) in exchange for the pleasure of Allah"[25][26]

Ali survived the plot, but risked his life again by staying in Mecca to carry out Muhammad's instructions: to restore to their owners all the goods and properties that had been entrusted to Muhammad for safekeeping. Ali then went to Medina with his mother, Muhammad's daughter Fatimah and two other women.[4][6]

In Medina

During Muhammad's era

Ali was 22 or 23 years old when he migrated to Medina. When Muhammad was creating bonds of brotherhood among his companions (sahaba) he selected Ali as his brother.[4][6][27] For the ten years that Muhammad led the community in Medina, Ali was extremely active in his service as his secretary and deputy, serving in his armies, the bearer of his banner in every battle, leading parties of warriors on raids, and carrying messages and orders. [28] As one of Muhammad's lieutenants, and later his son-in-law, Ali was a person of authority and standing in the Muslim community.

Family life

In 623, Muhammad told Ali that God ordered him to give his daughter Fatimah Zahra to Ali in marriage.[1] Muhammad said to Fatimah: "I have married you to the dearest of my family to me."[29] This family is glorified by Muhammad frequently and he declared them as his Ahl al-Bayt in events such as Mubahala and hadith like the Hadith of the Event of the Cloak. They were also glorified in the Qur'an in several cases such as "the verse of purification".[30][31]

Ali had four children born to Fatimah, the only child of Muhammad to have progeny. Their two sons (Hasan and Husain) were cited by Muhammad to be his own sons, honored numerous times in his lifetime and titled "the leaders of the youth of Jannah" (Heaven, the hereafter.)[32][33]

Theirs was a simple life of hardship and deprivation. Throughout their life together, Ali remained poor because he did not set great store by material wealth.To relieve their extreme poverty, Ali worked as a drawer and carrier of water and she as a grinder of corn. Often there was no food in her house. According to a famous Hadith, one day she said to Ali: "I have ground until my hands are blistered." and Ali answered "I have drawn water until I have pains in my chest."[34][35]

Their marriage lasted until Fatimah's death ten years later. Although polygamy was permitted, Ali did not marry another woman while Fatimah was alive, and his marriage to her possesses a special spiritual significance for all Muslims because it is seen as the marriage between two great figures surrounding Muhammad. After Fatimah's death, Ali married other wives and fathered many children.[1]

In battles

With the exception of the Battle of Tabouk, Ali took part in all battles and expeditions fought for Islam.[6] As well as being the standard-bearer in those battles, Ali led parties of warriors on raids into enemy lands.

Ali first distinguished himself as a warrior in 624 at the Battle of Badr. He defeated the Umayyad champion Walid ibn Utba as well as many other Meccan soldiers. According to Muslim traditions Ali killed between twenty and thirty-five enemies in battle, most agreeing with twenty-seven.[36]

Ali was prominent at the Battle of Uhud, as well as many other battles where he wielded a bifurcated sword known as Zulfiqar.[37] He had the special role of protecting Muhammad when most of the Muslim army fled from the battle of Uhud[1] and it was said "There is no brave youth except Ali and there is no sword which renders service except Zulfiqar."[38] He was commander of the Muslim army in the Battle of Khaybar.[39] Following this battle Mohammad gave Ali the name Asadullah, which in Arabic means "Lion of Allah" or "Lion of God". Ali also defended Muhammad in the Battle of Hunayn in 630.[1]

Missions for Islam

Muhammad designated Ali as one of the scribes who would write down the text of the Qur'an, which had been revealed to Muhammad during the previous two decades. As Islam began to spread throughout Arabia, Ali helped establish the new Islamic order. He was instructed to write down the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah, the peace treaty between Muhammad and the Quraysh in 628. Ali was so reliable and trustworthy that Muhammad asked him to carry the messages and declare the orders. In 630, Ali recited to a large gathering of pilgrims in Mecca a portion of the Qur'an that declared Muhammad and the Islamic community were no longer bound by agreements made earlier with Arab polytheists. During the Conquest of Mecca in 630, Muhammad asked Ali to guarantee that the conquest would be bloodless. He ordered Ali to break all the idols worshipped by the Banu Aus, Banu Khazraj, Tayy, and those in the Kaaba to purify it after its defilement by the polytheism of the pre-Islamic era. Ali was sent to Yemen one year later to spread the teachings of Islam. He was also charged with settling several disputes and putting down the uprisings of various tribes.[1][4]

The incident of Mubahala

According to hadith collections, in 631 an Arab Christian envoy from Najran (currently in northern Yemen and partly in Saudi Arabia) came to Muhammad to argue which of the two parties erred in its doctrine concerning Jesus. After likening Jesus' miraculous birth to Adam's creation[40], Muhammad called them to mubahala (cursing), where each party should ask God to destroy the lying party and their families.[41] Muhammad, to prove to them that he is a prophet, brought his daughter Fatimah and his surviving grandchildren Hasan ibn Ali and Husayn ibn Ali, and Ali ibn Abi Talib and came back to the Christians and said this is my family and covered himself and his family with a cloak.[42] When one of the Christian monks saw their faces, he advised his companions to withdraw from Mubahala for the sake of their lives and families. Thus the Christian monks vanished from the Mubahala place. Allameh Tabatabaei explains in Tafsir al-Mizan that the word "Our selves" in this verse [41] refers to Muhammad and Ali. Then he narrates Imam Ali al-Rida, eighth Shia Imam, in discussion with Al-Ma'mun, Abbasid caliph, referred to this verse to prove the superiority of Muhammad's progeny over the rest of the Muslim community, and considered it the proof for Ali's right for caliphate due to Allah made Ali like the self of Muhammad.[43]

Ghadir Khumm

As Muhammad was returning from his last pilgrimage in 632, he made statements about Ali that are interpreted very differently by Sunnis and Shias.[1] He halted the caravan at Ghadir Khumm, gathered the returning pilgrims for communal prayer and began to address them[44]:

O people, I am a human being. I am about to receive a message from my Lord and I, in response to Allah's call, (would bid good-bye to you), but I am leaving among you two weighty things: the one being the Book of Allah(Qur'an) in which there is right guidance and light, so hold fast to the Book of Allah and adhere to it. He exhorted (us) (to hold fast) to the Book of Allah and then said: The second are the members of my household I remind you (of your duties) to the members of my family.[45].

This quote is confirmed by both Shi’a and Sunni, but they interpret the quote differently.[46]

Some Sunni and Shi'a sources report that then he called Ali ibn Abi Talib to his sides, took his hand and raised it up declaring[47]

The Shia's regard these statements as constituting the investiture of Ali as the successor of Muhammad and as the first Imam; by contrast, the Sunnis take them only as an expression of Muhammad's closeness to Ali and of his wish that Ali, as his cousin and son-in-law, inherit his family responsibilities upon his death. [49] Many Sufis also interpret the episode as the transfer of Muhammad's spiritual power and authority to Ali, whom they regard as the wali par excellence.[1][50]

On the basis of this hadith, Ali later insisted on his religious authority superior to that of Abu Bakr and Umar.[51]

Succession to Muhammad

Template:Succession to Muhammad

| Part of a series on Shia Islam |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on Sunni Islam |

|---|

|

|

|

After uniting the Arabian tribes into a single Muslim religious polity in the last years of his life, Muhammad's death in 632 signalled disagreement over who would succeed him as leader of the Muslim community.[52] While Ali and the rest of Muhammad's close family were washing his body for burial, at a gathering attended by a small group of Muslims at Saqifah, a close companion of Muhammad named Abu Bakr was nominated for the leadership of the community. Others added their support and Abu Bakr was made the first caliph. The choice of Abu Bakr disputed by some of the Muhammad's companions, who held that Ali had been designated his successor by Muhammad himself.[8][53]

Following his election to the caliphate, Abu Bakr and Umar with a few other companions headed to Fatimah's house to obtain homage from Ali and his supporters who had gathered there. Then, it is alleged that Umar threatened to set the house on fire unless they came out and swore allegiance with Abu Bakr.[54] Then Umar set the house on fire and pushed the burnt door on Fatima. Some sources say upon seeing them, Ali came out with his sword drawn but was put in chains by Umar and their companions.[citation needed] Fatimah, in support of her husband, started a commotion and threatened to "uncover her hair", at which Abu Bakr relented and withdrew.[55] Ali is reported to have repeatedly said that had there been forty men with him he would have resisted.[54] When Abu Bakr's selection to the caliphate was presented as a fait accompli, Ali withheld his oaths of allegiance until after the death of Fatimah. Ali did not actively assert his own right because he did not want to throw the nascent Muslim community into strife.[4]

This contentious issue led Muslims to later split into two groups, Sunni and Shi'a. Sunnis assert that even though Muhammad never appointed a successor, Abu Bakr was elected first caliph by the Muslim community. The Sunnis recognize the first four caliphs as Muhammad's rightful successors. Shi'as believe that Muhammad explicitly named Ali as his successor at Ghadir Khumm and Muslim leadership belonged to him which had been determined by divine order.[8][56]

The two groups also disagree on Ali's attitude towards Abu Bakr, and the two caliphs who succeeded him: Umar and Uthman Ibn Affan. Sunnis tend to stress Ali's acceptance and support of their rule, while the Shi'a claim that he distanced himself from them, and that he was being kept from fulfilling the religious duty that Muhammad had assigned to him. Sunnis maintain that if Ali was the rightful successor as ordained by God Himself, then it would have been his duty as leader of the Muslim nation to make war with these people (Abu Bakr, Umar and Uthman) until Ali established the decree. Shias contend that Ali did not fight Abu Bakr, Umar or Uthman, because firstly he did not have the military strength and if he decided to, it would have caused a civil war amongst the Muslims.[57] Ali also believed that he could fulfil his role of Imam'ate without this fighting .[58]

Ali himself was firmly convinced of his legitimacy for caliphate based on his close kinship with Muhammad, his intimate association and his knowledge of Islam and his merits in serving its cause. He told Abu Bakr that his delay in pledging allegiance (bay'ah) as caliph was based on his belief of his own prior title. Ali did not change his mind when he finally pledged allegiance to Abu Bakr and then to Umar and to Uthman but had done so for the sake of the unity of Islam, at a time when it was clear that the Muslims had turned away from him.[8][59]

According to historical reports, Ali maintained his right to the caliphate and said:

By Allah the son of Abu Quhafah (Abu Bakr) dressed himself with it (the caliphate) and he certainly knew that my position in relation to it was the same as the position of the axis in relation to the hand-mill...I put a curtain against the caliphate and kept myself detached from it... I watched the plundering of my inheritance till the first one went his way but handed over the Caliphate to Ibn al-Khattab after himself.[60]

Inheritance

After Muhammad died his daughter, Fatimah, asked Abu Bakr to turn over their property, the lands of Fadak and Khaybar but he refused and told her that prophets didn't have any legacy and Fadak belonged to the Muslim community. Abu Bakr said to her, "Allah's Apostle said, we do not have heirs, whatever we leave is Sadaqa." Ali together with Umm Ayman testified to the fact that Muhammad granted it to Fatimah Zahra, when Abu Bakr requested Fatima to summon witnesses for her claim. Fatimah became angry and stopped speaking to Abu Bakr, and continued assuming that attitude until she died.[61]

After Fatima's death Ali again claimed her inheritance during Umar's era, but was denied with the same argument. Umar, the caliph who succeeded Abu Bakr, did restore the estates in Medina to ‘Abbas ibn ‘Abd al-Muttalib and Ali, as representatives of Muhammad's clan, the Banu Hashim. The properties in Khaybar and Fadak were retained as state property.[62]

Life after Muhammad

Another part of Ali's life started in 632 after death of Muhammad and lasted until assassination of Uthman Ibn Affan, the third caliph in 656. During these years, Ali neither took part in any battle or conquest.[4] nor did he assume any executive position. He withdrew from political affairs, especially after the death of his wife, Fatima Zahra. He used his time to serve his family and worked as a farmer. Ali dug a lot of wells and gardens near Medina and endowed them for public use. These wells are known today as Abar Ali ("Ali's wells").[63] He also made gardens for his family and descendants.[citation needed]

Ali compiled a complete version of the Qur'an, mus'haf.[64] six months after the death of Muhammad. The volume was completed and carried by camel to show to other people of Medina. The order of this mus'haf differed from that which was gathered later during the Uthmanic era. This book was rejected by several people when he showed it to them. Despite this, Ali made no resistance against standardized mus'haf.[65]

Ali and the Rashidun Caliphs

Ali did not give his oath of allegiance to Abu Bakr until some time after the death of his wife, Fatimah.[4] Ali participated in the funeral of Abu Bakr but did not participate in the Ridda Wars.[66]

He pledged allegiance to the second caliph Umar ibn Khattab and helped him as a trusted advisor. Caliph Umar particularly relied upon Ali as the Chief Judge of Medina. He also advised Umar to set Hijra as the beginning of the Islamic calendar. Umar used Ali's suggestions in political issues as well as religious ones.[67]

Ali was one of the electoral council to choose the third caliph which was appointed by Umar. Although Ali was one of the two major candidates, but the council's arrangement was against him. Sa'd ibn Abi Waqqas and Abdur Rahman bin Awf who were cousins, were naturally inclined to support Uthman, who was Abdur Rahman's brother-in-law. In addition, Umar gave the casting vote to Abdur Rahman. Abdur Rahman offered the caliphate to Ali on the condition that he should rule in accordance with the Quran, the example set by Muhammad, and the precedents established by the first two caliphs. Ali rejected the third condition while Uthman accepted it. According to Ibn Abi al-Hadid's Comments on the Peak of Eloquence Ali insisted on his prominence there, but most of the electors supported Uthman and Ali was reluctantly urged to accept him.[68]

Siege of Uthman

Uthman Ibn Affan, expressed generosity toward his kin, Banu Abd-Shams, who seemed to dominate him and his supposed arrogant mistreatment toward several of the earliest companions such as Abu Dharr al-Ghifari, Abd-Allah ibn Mas'ud and Ammar ibn Yasir provoked outrage among some groups of people. Dissatisfaction and resistance openly arose since 650-651 throughout most of the empire.[69] The dissatisfaction with his rule and the governments appointed by him was not restricted to the provinces outside Arabia.[70] When Uthman's kin, especially Marwan, gained control over him, the noble companions including most of the the members of elector council, turned against him or at least withdrew their support putting pressure on the caliph to mend his ways and reduce the influence of his assertive kin.[71]

At this time, Ali had acted as a restraining influence on Uthman without directly opposing him. On several occasions Ali disagreed with Uthman in the application of the Hudud; he had publicly shown sympathy for Abu Dharr al-Ghifari and had spoken strongly in the defense of Ammar ibn Yasir. He conveyed to Uthman the criticisms of other Companions and acted on Uthman's behalf as negotiator with the provincial opposition who had come to Medina; because of this some mistrust between Ali and Uthman's family seems to have arisen. Finally he tried to mitigate the severity of the siege by his insistence that Uthman should be allowed water.[4]

There is controversy among historians about the relationship between Ali and Uthman. Although pledging allegiance to Uthman, Ali disagreed with some of his policies. In particular, he clashed with Uthman on the question of religious law. He insisted that religious punishment had to done in several cases such as Ubayd Allah ibn Umar and Walid ibn Uqba. In 650 during pilgrimage, he confronted Uthman with reproaches for his change of the prayer ritual. When Uthman declared that he would take whatever he needed from the fey', Ali exclaimed that in that case the caliph would be prevented by force. Ali endeavored to protect companions from maltreatment by the caliph such as Ibn Mas'ud.[72] Therefore, some historians consider Ali one the leading members of Uthman's opposition, if not the main one. Because he could clearly be expected to be the prime beneficiary of the overthrow of Uthman. But Wilferd Madelung rejects their judgment due to the fact that Ali did not have the Quraysh's support to be elected as a caliph. According to him, there is even no evidence that Ali had close relations with rebels who supported his caliphate or directed their actions. [73] Some other sources says Ali had acted as a restraining influence on Uthman without directly opposing him.[4] However Madelung narrates Marwan told Zayn al-Abidin, the grandson of Ali, that

No one [among the Islamic nobility] was more temperate toward our master than your master.[74]

Caliphate

Election as Caliph

Ali was caliph between 656 and 661, during one of the more turbulent periods in Muslim history, which also coincided with the First Fitna.

Uthman's assassination meant that rebels had to select a new caliph. This met with difficulties since the rebels were divided into several groups comprising the Muhajirun, Ansar, Egyptians, Kufans and Basntes. There were three candidates: Ali, Talhah and al-Zubayr. First the rebels approached Ali, requesting him to accept being the caliph. Some of Muhammad's companions tried to persuade Ali in accepting the office,[60][75][76] but he turned down the offer, suggesting to be a counselor instead of a chief.[77]

Talhah, Zubayr and other companions also refused the rebels' offer of the caliphate. Therefore, the rebels warned the inhabitants of Medina to select a caliph within one day, or they would apply drastic action. In order to resolve the deadlock, the Muslims gathered in the Mosque of the Prophet on June 18, 656 to appoint the caliph. Initially Ali refused to accept simply because his most vigorous supporters were rebels. However, when some notable companions of Muhammad, in addition to the residents of Medina urged him to accept the offer, he finally agreed. According to Abu Mekhnaf's narration, Talhah was the first prominent companion who gave his pledge to Ali, but other narrations claimed otherwise, stating they were forced to give their pledge. Also, Talhah and Zubayr later claimed they supported him reluctantly. Regardless, Ali refuted these claims, insisting they recognized him as caliph voluntarily. Wilferd Madelung believes that force did not urge people to give their pledge and they pledged publicly in the mosque.[9][10]

While the overwhelming majority of Madina's population as well as many of the rebels gave their pledge, some important figures or tribes did not do so. The Umayyads, kinsmen of Uthman, fled to the Levant or remained in their houses, later refusing Ali's legitimacy. Sa‘ad ibn Abi Waqqas was absent and Abdullah ibn Umar abstained from offering his allegiance, but both of them assured Ali that they would not act against him.[9][10]

Reign as Caliph

Since the conflicts in which Ali was involved were perpetuated in polemical sectarian historiography, biographical material is often biased. But the sources agree that he was a profoundly religious man, devoted to the cause of Islam and the rule of justice in accordance with the Quran and the Sunna; he engaged in war against erring Muslims as a matter of religious duty. The sources abound in notices on his austerity, rigorous observance of religious duties, and detachment from worldly goods. Thus some authors have pointed out that he lacked political skill and flexibility.[4]

Ali inherited the Rashidun Caliphate—which extended from Egypt in the west to the Iranian highlands in the east—while the situation in the Hejaz and the other provinces on the eve of his election was unsettled. Soon after Ali became caliph, he dismissed provincial governors who had been appointed by Uthman, replacing them with trusted aides. He acted against the counsel of Mughira ibn Shu'ba and Ibn Abbas, who had advised him to proceed his governing cautiously. Madelung says Ali was deeply convinced of his right and his religious mission, unwilling to compromise his principles for the sake of political expediency, and ready to fight against overwhelming odds.[78] Muawiyah I, the kinsman of Uthman and governor of the Levant refused to submit to Ali's orders; he was the only governor to do so.[4]

When he was appointed caliph, Ali stated to the citizens of Medina that Muslim polity had come to be plagued by dissension and discord; he desired to purge Islam of any evil. He advised the populace to behave as true Muslims, warning that he would tolerate no sedition and those who were found guilty of subversive activities would be dealt with harshly.[79] Ali recovered the land granted by Uthman and swore to recover anything that elites had acquired before his election. Ali opposed the centralization of capital control over provincial revenues, favoring an equal distribution of taxes and booty amongst the Muslim citizens; He distributed the entire revenue of the treasury among them. Ali refrained from nepotism, including with his brother Aqeel ibn Abi Talib. This was an indication to Muslims of his policy of offering equality to Muslims who served Islam in its early years and to the Muslims who played a role in the later conquests.[4][80]

Ali succeeded in forming a broad coalition especially after the Battle of Bassorah. His policy of equal distribution of taxes and booty gained the support of Muhammad's companions especially the Ansar who were subordinated by the Quraysh leadership after Muhammad, the traditional tribal leaders, and the Qurra or Qur'an reciters that sought pious Islamic leadership. The successful formation of this diverse coalition seems to be due to Ali's charismatic character.[4][81] This diverse coalition became known as Shi'a Ali, meaning "party" or "faction of Ali". However according to Shia, as well as non-Shia reports, the majority of those who supported Ali after his election as caliph, were shia politically, not religiously. Although at this time there were many who counted as political Shia, few of them believed Ali's religious leadership.[82]

First Fitna

A'isha, Talhah, Al-Zubayr and Umayyad especially Muawiyah I wanted to take revenge for Uthman's death and punish the rioters who had killed him. They attacked Ali for not punishing the rebels and murderers of Uthman. However some historians believe that they use this issue to seek their political ambitions because they found Ali's caliphate against their own benefit. On the other hand, the rebels maintained that Uthman had been justly killed, for not governing according to Quran and Sunnah, hence no vengeance was to be invoked.[4][6][83] Historians disagree on Ali's position. Some say the caliphate was a gift of the rebels and Ali did not have enough force to control or punish them[79], while others say Ali accepted rebels argument or at least didn't consider Uthman just ruler.[84]

Under such circumstances, a schism took place which led to the first civil war in Muslim history. Some Muslims, known as Uthmanis, considered Uthman a rightful and just Imam (Islamic leader) till the end, who had been unlawfully killed. Thus his position was in abeyance until he had been avenged and a new caliph elected. In their view Ali was the Imam of error leading a party of infidels. Some others, who knows as party of Ali, believed Uthman had fallen into error, he had forfeited the caliphate and been lawfully executed for his refusal to mend his way or step down, thus Ali was the just and true Imam and his opponents are infidels. This civil war created permanent divisions within the Muslim community regarding who had the legitimate right to occupy the caliphate.[85]

The First Fitna, 656–661, followed the assassination of Uthman, continued during the caliphate of Ali, and was ended by Muawiyah's assumption of the caliphate. This civil war (often called the Fitna) is regretted as the end of the early unity of the Islamic ummah (nation). Ali was first opposed by a faction led by Talhah, Al-Zubayr and Muhammad's wife, Aisha bint Abu Bakr. This group, known as "disobedients" (Nakithin) by their enemies, gathered in Mecca then moved to Basra with the expectation of finding the necessary forces and resources to mobilize people of Iraq. The rebels occupied Basra, killing many people. They refused Ali's offer of obedience and pledge of allegiance. The two sides met at the Battle of Bassorah (Battle of the Camel) in 656, where Ali emerged victorious.[86]

Ali appointed Ibn Abbas governor of Basra and moved his capital to Kufa, the Muslim garrison city in Iraq. Kufa was in the middle of Islamic land and had strategic position.[87]

Later he was challenged by Muawiyah I, the governor of Levant and the cousin of Uthman, who refused Ali's demands for allegiance and called for revenge for Uthman. Ali opened negotiations hoping to regain his allegiance, but Muawiyah insisted on Levant autonomy under his rule. Muawiyah replied by mobilizing his Levantine supporters and refusing to pay homage to Ali on the pretext that his contingent had not participated in his election. The two armies encamped themselves at Siffin for more than one hundred days, most of the time being spent in negotiations. Although, Ali exchanged several letters with Muawiyah, he was unable to dismiss the latter, nor persuade him to pledge allegiance. Skirmishes between the parties led to the Battle of Siffin in 657. After a week of combat was followed by a violent battle known as laylat al-harir (the night of clamor), Muawiyah's army were on the point of being routed when Amr ibn al-Aas advised Muawiyah to have his soldiers hoist mus'haf (either parchments inscribed with verses of the Qur'an, or complete copies of it) on their spearheads in order to cause disagreement and confusion in Ali's army.[4][88] Ali saw through the stratagem, but only a minority wanted to pursue the fight.[8]

The two armies finally agreed to settle the matter of who should be Caliph by arbitration. The refusal of the largest bloc in Ali's army to fight was the decisive factor in his acceptance of the arbitration. The question as to whether the arbiter would represent Ali or the Kufans caused a further split in Ali's army. Ash'ath ibn Qays and some others rejected Ali's nominees, 'Abd Allah ibn 'Abbas and Malik al-Ashtar, and insisted on Abu Musa Ash'ari, who was opposed by Ali, since he had earlier prevented people from supporting him. Finally, Ali was urged to accept Abu Musa. Some of Ali's supporters, later were known as Kharijites (schismatics), opposed arbitration and rebelled and Ali had to fight with them in the Battle of Nahrawan. The arbitration resulted in the dissolution of Ali's coalition and some have opined that this was Muawiyah's intention.[4][89]

In the following years Muawiyah's army invaded and plundered cities of Iraq, which Ali's governors could not prevent and people did not support him to fight with them. Muawiyah overpowered Egypt, Hijaz, Yemen and other areas.[90] In the last year of Ali's caliphate, the mood in Kufa and Basra changed in his favor as Muawiyah's vicious conduct of the war revealed the nature of his reign. However the people's attitude toward Ali was deeply differed. Just a small minority of them believed that Ali was the best Muslim after Muhammad and the only one entitled to rule them, while the majority supported him due to their distrust and opposition to Muawiyah.[91]

Policies

What shows Ali's policies and ideas of governing is his instruction to Malik al-Ashtar, when appointed by him as governor of Egypt. This instruction which is considered by many Muslims and even non-Muslims as the ideal constitution for Islamic governance involved detailed description of duties and rights of the ruler and various functionaries of the state and the main classes of society at that time.[92][93]

Ali wrote in his instruction to Malik al-Ashtar:

Infuse your heart with mercy, love and kindness for your subjects. Be not in face of them a voracious animal, counting them as easy prey, for they are of two kinds:either they are your brothers in religion or your equals in creation. Error catches them unaware, deficiencies overcome them, (evil deeds) are committed by them intentionally and by mistake. So grant them your pardon and your forgiveness to the same extent that you hope God will grant you His pardon and His forgiveness. For you are above them, and he who appointed you is above you, and God is above him who appointed you. God has sought from you the fulfillment of their requirements and He is trying you with them.[94]

Since the majority of Ali's subjects were nomads and peasants, he was concerned with agriculture. He instructed to Malik to give more attention to development of the land than to the collection of the tax, because tax can only be obtained by the development of the land and whoever demands tax without developing the land ruins the country and destroys the people.[95]

Death

On the 19th of Ramadan, while Ali was praying in the Qibla of Great Mosque of Kufa, Abd-al-Rahman ibn Muljam, a Kharijite, assassinated him with a stroke of his poison-coated sword. Ali, wounded by the poisonous sword, lived for two days before dying in Kufa on the 21st of Ramadan in 661.[96]

Ali ordered his sons not to attack the Kharijites, even though a single member of the group of Kharijites killed him. Ali said to his son, Imam Hasan that if he lives on he will forgive Abd-al-Rahman ibn Muljam and free him, however, in the event of his death, ibn Muljim should get one equal hit and not more regardless if he dies from the hit or not, just as Ali himself received one hit from Abd-al-Rahman ibn Muljam.[97] Thus,Imam Hasan fulfilled Qisas and gave equal hurt as Ali got to ibn Muljam.[91]

Burial

According to Al-Shaykh Al-Mufid, Ali did not want his grave to be desecrated by his enemies and consequently asked his friends and family to bury him secretly. This secret gravesite was revealed later during the Abbasid caliphate by Imam Ja'far al-Sadiq, his descendant and the sixth Shia Imam.[98] Most Shi'as accept that Ali is buried at the Tomb of Imam Ali in the Imam Ali Mosque at what is now the city of Najaf, which grew around the mosque and shrine called Masjid Ali.[99][100]

However another story, usually maintained by some Afghans, notes that his body was taken and buried in the Afghan city of Mazar-E-Sharif at the famous Blue Mosque or Rawze-e-Sharif.[101]

Aftermath

After Ali's death, Kufi Muslims pledged allegiance to his eldest son Hasan without dispute, as Ali on many occasions had declared that just Ahl al-Bayt of Muhammad were entitled to rule the Muslim community.[102] At this time, Muawiyah held both Levant and Egypt and, as commander of the largest force in the Muslim Empire, had declared himself caliph and marched his army into Iraq, the seat of Hasan's caliphate.

War ensued during which Muawiyah gradually subverted the generals and commanders of Hasan's army with large sums of money and deceiving promises until the army rebelled against him. Finally, Hasan was forced to make peace and to yield the caliphate to Muawiyah. In this way Muawiyah captured the Islamic caliphate and in every way possible placed the severest pressure upon Ali's family and his Shi'a. Regular public cursing of Imam Ali in the congregational prayers remained a vital institution which was not abolished until 60 years later by Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz. Muawiyah also established the Umayyad caliphate which was a centralized monarchy. [103]

Madelung writes:

Umayyad highhandedness, misrule and repression were gradually to turn the minority of Ali's admirers into a majority. In the memory of later generations Ali became the ideal Commander of the Faithful. In face of the fake Umayyad claim to legitimate sovereignty in Islam as God's Vice-regents on earth, and in view of Umayyad treachery, arbitrary and divisive government, and vindictive retribution, they came to appreciate his [Ali's] honesty, his unbending devotion to the reign of Islam, his deep personal loyalties, his equal treatment of all his supporters, and his generosity in forgiving his defeated enemies.[14]

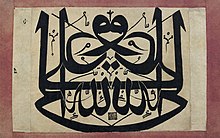

Knowledge

Ali is respected not only as a warrior and leader, but as a writer and religious authority. Numerous range of disciplines from theology and exegesis to calligraphy and numerology, from law and mysticism to Arabic grammar and Rhetoric regarded as having been first adumbrated by Ali.[100]

Shia and Sufis believe that Muhammad told about him "I'm the city of knowledge and Ali is its gate..."[100][104][105][106] Muslims regard Ali as a major authority on Islam. Ali himself gives this testimony:

Not a single verse of the Qur'an descended upon (was revealed to) the Messenger of God which he did not proceed to dictate to me and make me recite. I would write it with my own hand, and he would instruct me as to its tafsir (the literal explanation) and the ta'wil (the spiritual exegesis), the nasikh (the verse which abrogates) and the mansukh (the abrogated verse), the muhkam and the mutashabih (the fixed and the ambiguous), the particular and the general...[107]

According to Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Ali is credited with having established Islamic theology and his quotations contain the first rational proofs among Muslims of the unity of God.[108] Ibn Abi al-Hadid has quoted

As for theosophy and dealing with matters of divinity, it was not an Arab art. Nothing of the sort had been circulated among their distinguished figures or those of lower ranks. This art was the exclusive preserve of Greece whose sages were its only expounders. The first one among Arabs to deal with it was Ali.[109]

In later Islamic philosophy, especially in the teachings of Mulla Sadra and his followers, like Allameh Tabatabaei, Ali's sayings and sermons were increasingly regarded as central sources of metaphysical knowledge, or divine philosophy. Members of Sadra's school regard Ali as the supreme metaphysician of Islam.[1]; According to Henry Corbin, the Nahj al-Balagha may be regarded as one of the most important sources of doctrines professed by Shia thinkers especially after 1500AD. Its influence can be sensed in the logical co-ordination of terms, the deduction of correct conclusions, and the creation of certain technical terms in Arabic which entered the literary and philosophical language independently of the translation into Arabic of Greek texts.[110]

Ali was also a great scholar of Arabic literature and pioneered in the field of Arabic grammar and rhetoric. Numerous short sayings of Ali have become part of general Islamic culture and are quoted as aphorisms and proverbs in daily life. They have also become the basis of literary works or have been integrated into poetic verse in many languages. Already in the 8th century, literary authorities such as 'Abd al-Hamid ibn Yahya al-'Amiri pointed to the unparalleled eloquence of Ali's sermons and sayings, as did al-Jahiz in the following century.[1] Even staffs in the Divan of Umayyad recited Ali's sermons to improve their eloquence.[111] Of course, Peak of Eloquence (Nahj al-Balagha) is an extract of Ali's quotations from a literal viewpoint as its compiler mentioned in the preface. While there are many other quotations, prayers (Du'as), sermons and letters in other literal, historic and religious books.[112]

In addition, some hidden or occult sciences such as jafr, Islamic numerology, the science of the symbolic significance of the letters of the Arabic alphabet, are said to have been established by Ali[1] through his having studied the texts of al-Jafr and al-Jamia.

Works

The compilation of sermons, lectures and quotations attributed to Ali are compiled in the form of several books.

- Nahj al-Balagha (Way of Eloquence) contains eloquent sermons, letters and quotations attributed to Ali which is compiled by ash-Sharif ar-Radi(d. 1015). Despite ongoing questions about the authenticity of the text, recent scholarship suggests that most of the material in it can in fact be attributed to Ali.[100] This book has a prominent position in Arabic literature. It is also considered an important intellectual, political and religious work in Islam.[1][113][114] Masadir Nahj al-Balagha wa asaniduh written by al-Sayyid ‘Abd al-Zahra' al-Husayni al-Khatib introduces some of these sources.[115] Also Nahj al-sa'adah fi mustadrak Nahj al-balaghah by Muhammad Baqir al-Mahmudi represents all of Ali's extant speeches, sermons, decrees, epistles, prayers, and sayings have been collected. It includes the Nahj al-balagha and other discourses which were not incorporated by ash-Sharif ar-Radi or were not available to him. Apparently, except for some of the aphorisms, the original sources of all the contents of the Nahj al-balagha have been determined.[113] There are several Comments on the Peak of Eloquence by Sunnis and Shias such as Comments of Ibn Abi al-Hadid and comments of Muhammad Abduh.

- Supplications (Du'a), translated by William Chittick[116]

- Ghurar al-Hikam wa Durar al-Kalim (Exalted aphorisms and Pearls of Speech) which is compiled by Abd al-Wahid Amidi(d. 1116) consists of over ten thounsads short sayings of Ali [117]

- Nuzhat al-Absar va Mahasin al-Asar, Ali's sermons which has compiled by Ali ibn Muhammad Tabari Mamtiri[118]

- Divan-i Ali ibn Abi Talib (poems which are attributed to Ali ibn Abi Talib)[4][119]

Descendants

Ali had several wives, Fatimah being the most beloved. He had four children by Fatimah, Hasan_ibn_Ali, Husayn ibn Ali, Zaynab bint Ali[1] and Umm Kulthum bint Ali. His other well-known sons were al-Abbas ibn Ali born to Fatima binte Hizam (Um al-Banin) and Muhammad ibn al-Hanafiyyah.[120]

Hasan, born in 625 AD, was the second Shia Imam and he also occupied the outward function of caliph for about six months. In the year 50 A.H., he was poisoned and killed by a member of his own household who, as has been accounted by historians, had been motivated by Mu'awiyah.[121]

Husayn, born in 626 AD, was the third Shia Imam. He lived under severe conditions of suppression and persecution by Mu'awiyah. On the tenth day of Muharram, of the year 680, he lined up before the army of caliph with his small band of follower and nearly all of them were killed in the Battle of Karbala. The anniversary of his death is called the Day of Ashura and it is a day of mourning and religious observance for Shi'a Muslims.[122] In this battle some of Ali's other sons were killed. Al-Tabari has mentioned their names in his history. Al-Abbas ibn Ali, the holder of Husayn's standard, Ja'far, Abdallah and Uthman, the four sons born to Fatima binte Hizam. Muhammad and Abu Bakr. The death of the last one is doubtful.[123] Some historians have added the names of Ali's others sons who were killed in Karbala, including Ibrahim, Umar and Abdallah ibn al-Asqar.[124][125]

His daughter Zaynab—who was in Karbala—was captured by Yazid's army and later played a great role in revealing what happened to Husayn and his followers.[126]

Ali's descendants by Fatimah are known as sharifs, sayeds or sayyids. These are honorific titles in Arabic, sharif meaning 'noble' and sayed or sayyid meaning 'lord' or 'sir'. As Muhammad's only descendants, they are respected by both Sunni and Shi'a, though the Shi'as place much more emphasis and value on the distinction.[1]

Views

Muslim views

Except for Muhammad, there is no one in Islamic history about whom as much has been written in Islamic languages as Ali.[1] Ali is revered and honored by all Muslims. Having been one of the first Muslims and foremost Ulema (Islamic scholars), he was extremely knowledgeable in matters of religious belief and Islamic jurisprudence, as well as in the history of the Muslim community. He was known for his bravery and courage. Muslims honor Muhammad, Ali, and other pious Muslims and add pious interjections after their names.[citation needed]

Shi'a

The Shi'a regard Ali as the most important figure after Muhammad. According to them, Muhammad suggested on various occasions during his lifetime that Ali should be the leader of Muslims after his demise. This is supported by numerous Hadith, including Hadith of the pond of Khumm, Hadith of the two weighty things, Hadith of the pen and paper, Hadith of the invitation of the close families, and Hadith of the Twelve Successors. In particular, the Hadith of the Cloak is often quoted to illustrate Muhammad's feeling towards Ali and his family:

One morning Muhammad went out wearing a striped cloak of black camel's hair when along came Hasan b. 'Ali. He wrapped him under it, then came Husain and he wrapped him under it along with the other one (Hasan). Then came Fatima and he took her under it, then came 'Ali and he also took him under it and then said: God only desires to keep away the uncleanness from you, O People of the House! and to purify you a (thorough) purifying.

— Book 031, Number 5955, in 40, 40, Sahih Muslim

According to this view, Ali as the successor of Muhammad not only ruled over the community in justice, but also interpreted the Sharia Law and its esoteric meaning. Hence he was regarded as being free from error and sin (infallible), and appointed by God by divine decree (nass) through Muhammad.[127] Ali is known as "perfect man" (al-insan al-kamil) similar to Muhammad according to Shia viewpoint.[128]

Shia pilgrims usually go to Mashad Ali in Najaf for Ziyarat, pray there and read "Ziyarat Amin Allah"[129] or other Ziyaratnames.[130] Under the Safavid Empire, his grave became the focus of much devoted attention, exemplified in the pilgrimage made by Shah Ismail I to Najaf and Karbala.[8]

Sunni

Contemporary Sunni Muslims generally regard Ali with respect as one of the Ahl al-Bayt and the last of the Rashidun caliphs and view him as one of the most influential and respected figures in Islam. Also, he is one of the Al-Asharatu Mubashsharun, which is the promised Ten to be in heaven.

Sufi

Almost all Sufi orders trace their lineage to Muhammad through Ali, an exception being Naqshbandi, who go through Abu Bakr. Even in this order, there is Ja'far al-Sadiq, the great great grandson of Ali. Sufis, whether Sunni or Shi'ite, believe that Ali inherited from Muhammad the saintly power wilayah that makes the spiritual journey to God possible.[1] Imam Ali represents the essence of the teachings of the School of Islamic Sufism.[citation needed]

Sufis recite Manqabat Ali in the praise of Ali (Maula Ali), after Hamd and Naat in their Qawwali.[citation needed]

As a deity

Some groups (such as the Alawis) believe that Ali is a deity in his own right or he was God incarnate. They are described as ghulat (Ar: غُلاة) "exaggerators" by the vast majority of Islamic scholars. These groups have, in traditional Islamic thought, left Islam due to their exaggeration of a human being's praiseworthy traits. Ali is recorded in some traditions as having forbidden those who sought to worship him in his own lifetime.[131]

Non-Muslim views

The English historian Edward Gibbon stated: "The zeal and virtue of Ali were never outstripped by any recent proselyte. He united the qualifications of a poet, a soldier, and a saint; his wisdom still breathes in a collection of moral and religious sayings; and every antagonist, in the combats of the tongue or of the sword, was subdued by his eloquence and valour. From the first hour of his mission to the last rites of his funeral, the apostle was never forsaken by a generous friend, whom he delighted to name his brother, his vicegerent, and the faithful Aaron of a second Moses."[132]. Scottish Orientalist William Muir declared that Ali was "Endowed with a clear intellect, warm in affection, and confiding in friendship, he was from the boyhood devoted heart and soul to the Prophet. Simple, quiet, and unambitious, when in after days he obtained the rule of half of the Moslem world, it was rather thrust upon him than sought." [133] However others, such as Herni Lammens[134], have held a negative view of Ali.

The poet Khalil Gibran said of him: "In my view, ʿAlī was the first Arab to have contact with and converse with the universal soul. He died a martyr of his greatness, he died while prayer was between his two lips. The Arabs did not realise his value until appeared among their Persian neighbors some who knew the difference between gems and gravels[135][136]."

Historiography of his life

The primary sources for scholarship on the life of Ali are the Qur'an and the Hadith, as well as other texts of early Islamic history. The extensive secondary sources include, in addition to works by Sunni and Shī‘a Muslims, writings by Christian Arabs, Hindus, and other non-Muslims from the Middle East and Asia and a few works by modern Western scholars. However, many of the early Islamic sources are colored to some extent by a positive or negative bias towards Ali.[1]

There had been a common tendency among the earlier western scholars against these narrations and reports gathered in later periods due to their tendency towards later Sunni and Shī‘a partisan positions; such scholars regarding them as later fabrications. This leads them to regard certain reported events as inauthentic or irrelevant. Leone Caetani considered the attribution of historical reports to Ibn Abbas and Aisha as mostly fictitious while proffering accounts reported without isnad by the early compilers of history like Ibn Ishaq. Wilferd Madelung has rejected the stance of indiscriminately dismissing everything not included in "early sources" and in this approach tendentious alone is no evidence for late origin. According to him, Caetani's approach is inconsistent. Madelung and some later historians do not reject the narrations which have been complied in later periods and try to judge them in the context of history and on the basis of their compatibility with the events and figures [137]

Until the rise of the Abbasid Caliphate, few books were written and most of the reports had been oral. The most notable work previous to this period is The Book of Sulaym ibn Qays, written by Sulaym ibn Qays, a companion of Ali who lived before the Abbasid.[138] When paper was introduced to Muslim society, numerous monographs were written between 750 and 950 AD. According to Robinson, at least twenty-one separate monographs have been composed on the Battle of Siffin. Abi Mikhnaf is one of the most renowned writers of this period who tried to gather all of the reports. 9th and 10th century historians collected, selected and arranged the available narrations. However, most of these monographs do not exist anymore except for a few which have been used in later works such as History of the Prophets and Kings by Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari (d.932).[139]

Shi'a of Iraq actively participated in writing monographs but most of those works have been lost. On the other hand, in the 8th and 9th century Ali's descendants such as Muhammad al Baqir and Jafar as Sadiq narrated his quotations and reports which have been gathered in Shia hadith books. The later Shia works written after the 10th century AD are about biographies of The Fourteen Infallibles and Twelve Imams. The earliest surviving work and one of the most important works in this field is Kitab al-Irshad by Shaykh Mufid (d. 1022). The author has dedicated the first part of his book to a detailed account of Ali. There are also some books known as Manāqib which describe Ali's character from a religious viewpoint. Such works also constitute a kind of historiography.[140]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af Nasr, Seyyed Hossein. "Ali". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 2007-10-12.

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 311

- ^ a b Ahmed 2005, p. 234

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s "Ali ibn Abitalib". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 2010-05-15.

- ^ Encyclopaedia of the Holy Prophet and Companions

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Tabatabaei 1979, p. 191

- ^ a b Ashraf 2005, p. 14

- ^ a b c d e f Diana, Steigerwald. "Ali ibn Abi Talib". Encyclopaedia of Islam and the Muslim world; vol.1. MacMillan. ISBN 0028656040.

- ^ a b c Ashraf 2005, p. 119 and 120

- ^ a b c Madelung 1997, p. 141-145

- ^ Lapidus 2002, p. 47

- ^ Holt, Lambton & Lewis 1970, p. 70-72

- ^ Tabatabaei 1979, p. 50-75 and 192

- ^ a b Madelung 1997, p. 309 and 310

- ^ Ashraf 2005, p. 5

- ^

See:

- Ashraf 2005, p. 6

- "Khalifa Ali bin Talib". witness-pioneer.org. 2004-11-05. Retrieved 2008-12-19.

- ^ Ashraf 2005, p. 6 and 7

- ^ Ashraf 2005, p. 7

- ^ Watt 1953, p. xii

- ^ Watt 1953, p. 86

- ^ Quran 26:214

- ^ See:

- Momen 1985, p. 12

- Tabatabaei 1979, p. 39

- ^ Ashraf 2005, p. 16-26

- ^ Ashraf 2005, p. 28 and 29

- ^ Quran 2:207

- ^ Tabatabaei, Sayyid Mohammad Hosayn. "[[Tafsir al-Mizan]], Volume 3: Surah Baqarah, Verses 204-207". almizan.org. Retrieved 2008-12-19.

{{cite web}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ Ashraf 2005, p. 30-32

- ^ See:

- Momen 1985, p. 13 and 14

- Ashraf 2005, p. 28-118

- ^ Singh 2003, p. 175

- ^ Quran 33:33

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 14 and 15

- ^ See:

- ^ "Hasan ibn Ali". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 2009-12-06.

- ^ Sahih Muslim, 31:5955

- ^ Singh 2003, p. 176

- ^ See:

- Ashraf 2005, p. 36

- Merrick 2005, p. 247

- ^ Khatab, Amal (May 1, 1996). Battles of Badr and Uhud. Ta-Ha Publishers. ISBN 1-897940-39-4.

- ^ Ibn Al Atheer, In his Biography, vol 2 p 107 "لا فتی الا علي لا سيف الا ذوالفقار"

- ^ See:

- Ashraf 2005, p. 66-68

- Zeitlin 2007, p. 134

- ^ Quran 3:59

- ^ a b Quran 3:61

- ^ See:

- Sahih Muslim, Chapter of virtues of companions, section of virtues of Ali, 1980 Edition Pub. in Saudi Arabia, Arabic version, v4, p1871, the end of tradition #32

- Sahih al-Tirmidhi, v5, p654

- Madelung 1997, p. 15 and 16

- ^ Tabatabaei, Sayyid Mohammad Hosayn. "[[Tafsir al-Mizan]], v.6, Al Imran, verses 61-63". almizan.org. Retrieved 2008-12-19.

{{cite web}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ Dakake 2008, p. 34 - 39

- ^ See:

- Dakake 2008, p. 39 and 40

- Sahih Muslim 031.5920 The Book Pertaining to the Merits of the Companions (Allah Be Pleased With Them) of the Holy Prophet (May Peace Be Upon Him) (Kitab Al-Fada'il Al-Sahabah)

- ^ Dakake 2008, p. 39 and 40

- ^ Dakake 2008, p. 34-37

- ^ See:

- Dakake 2008, p. 34 and 35

- Ibn Taymiyyah, Minhaaj as-Sunnah 7/319

- ^ See:

- Dakake 2008, p. 43-48

- Tabatabaei 1979, p. 40

- ^ Dakake 2008, p. 33-35

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 253

- ^ Lapidus 2002, p. 31 and 32

- ^ See:

- Holt, Lambton & Lewis 1970, p. 57

- Madelung 1997, p. 26-27, 30-43 and 356-360

- ^ a b Madelung 1997, p. 43

- ^ "Fatima", Encyclopedia of Islam. Brill Online.

- ^ "Sunnite". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 2007-04-11.

- ^ Sahih Bukhari 5.57.50

- ^ Chirri 1982

- ^ See:

- Madelung 1997, p. 141 and 270

- Ashraf 2005, p. 99 and 100

- ^ a b

- Nahj Al-Balagha Nahj Al-Balagha Sermon 3

- For Isnad of this sermon and the name of the names of scholars who narrates it see Nahjul Balagha, Mohammad Askari Jafery (1984), pp. 108-112

- ^ See:

- Madelung 1997, p. 50 and 51

- Qazwini & Ordoni 1992, p. 211

- [Quran 27:16]

- [Quran 21:89]

- Sahih al-Bukhari, 4:53:325

- Sahih al-Bukhari, 5:59:546

- Sahih Muslim, 19:4352

- ^

- Madelung 1997, p. 62-64

- Sahih al-Bukhari, 4:53:326

- ^ History of Mecca, Medina and all other Ziyarats

- ^ Nasr, Seyyed Hossein (2007). "Qur'an". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 2007-11-04.

- ^ See:

- Tabatabaei 1987, p. chapter 5

- Observations on Early Qur'an Manuscripts in San'a

- The Qur'an as Text, ed. Wild, Brill, 1996 ISBN 90-04-10344-9

- ^

See:

- Ashraf 2005, p. 100 and 101

- Madelung 1997, p. 141

- Sahih al-Bukhari, 5:59:546

- Sahih al-Bukhari, 8:82:817

- Sahih Muslim, 19:4352

- Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari, vol. 3, p.208; Ibn Qutaybah, vol. 1, p.29; quoted in Ayoub, 2003, 18

- Rizvi, Sa'id Akhtar, Imamate: The Vicegerency of the Prophet by, quoting Ibn Qutaybah 18. SUNNI VIEWS ON THE CALIPHATE

- Shi'a encyclopedia quoting from Ibn Qutaybah, Muhammad al-Bukhari, Massudi, Ibn Abu al-Hadid

- The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire by Edward Gibbon, section Reign of Abubeker; A.D. 632, June 7.

- ^ See

- Ashraf 2005, p. 107-110

- The Caliphate of Umar

- ^ See:

- Madelung 1997, p. 70 - 72

- Dakake 2008, p. 41

- Momen 1985, p. 21

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 87 and 88

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 90

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 92-107

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 109 and 110

- ^ See:

- Holt, Lambton & Lewis 1970, p. 67 and 68

- Madelung 1997, p. 107 and 111

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 334

- ^ Ashraf 2005, p. 119

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 141-143

- ^ Hamidullah 1988, p. 126

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 148 and 149

- ^ a b Ashraf 2005, p. 121

- ^ See:

- Lapidus 2002, p. 46

- Madelung 1997, p. 150 and 264

- ^ Shaban 1971, p. 72

- ^ Momen 1985, p. 63

- ^ See:

- Madelung 1997, p. 147 and 148

- Lewis 1991, p. 214

- ^ Lewis 1991, p. 214

- ^ See:

- Lapidus 2002, p. 47

- Holt, Lambton & Lewis 1970, p. 72

- Tabatabaei 1979, p. 57

- ^ See:

- Lapidus 2002, p. 47

- Holt, Lambton & Lewis 1970, p. 70-72

- Tabatabaei 1979, p. 50 - 53

- ^ 'Ali

- ^ See:

- Lapidus 2002, p. 47

- Holt, Lambton & Lewis 1970, p. 70-72

- Tabatabaei 1979, p. 53 and 54

- ^ See:

- Madelung 1997, p. 241 - 259

- Lapidus 2002, p. 47

- Holt, Lambton & Lewis 1970, p. 70-72

- Tabatabaei 1979, p. 53 and 54

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 267-269 and 293-307

- ^ a b Madelung 1997, p. 309

- ^ Shah-Kazemi 2007, p. 81

- ^ United Nations Development Program, Arab human development report, (2002), p. 107

- ^ Nasr, Dabashi & Nasr 1989, p. 75

- ^ Lambton 1991, p. xix and xx

- ^ Tabatabaei 1979, p. 192

- ^ Kelsay 1993, p. 92

- ^ Al-Shaykh Al-Mufid 1986

- ^ Redha 1999

- ^ a b c d Shah-Kazemi, Reza (2006). "'Ali ibn Abi Talib". Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0415966914.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help), Pages 36 and 37 - ^ Balkh and Mazar-e-Sharif

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 313 and 314

- ^ See:

- Madelung 1997, p. 334

- Lapidus 2002, p. 47

- Holt, Lambton & Lewis 1970, p. 72

- Tabatabaei 1979, p. 195

- ^ Momen 1985, p. 14

- ^ School of Islamic Sufism

- ^ World of Tasawwuf

- ^ Corbin 1993, p. 46

- ^ Nasr 2006, p. 120

- ^ Nasr, Dabashi & Nasr 1996, p. 136

- ^ Corbin 1993, p. 35

- ^ "حفظت سبعين خطبة من خطب الاصلع ففاضت ثم فاضت ) ويعني بالاصلع أمير المؤمنين عليا عليه السلام"مقدمة في مصادر نهج البلاغة

- ^ See:

- ^ a b Mutahhari, 1997 The Glimpses of Nahj al Balaghah Part I - Introduction

- ^ Shah-Kazemi 2007, p. 3

- ^ Quarterly Journal of Islamic Thought and Culture, Vol. VII, No. 1 issue of Al-Tawhid

- ^ Ali ibn Abi Talib (1990). Supplications (Du'a). Muhammadi Trust. p. 42. ISBN 0950698644.

- ^ Shah-Kazemi 2007, p. 4

- ^ پیدا شدن مجموعه نفیس کلمات امام علی(ع) در واتیكان : «نزهه الأبصار و محاسن الآثار» عنوان کتابی است از ابوالحسن علی بن محمد بن مهدی طبری مامطیری، که دربر دارنده کلمات مولای متقیان امام علیبنابیطالب (ع) است و پیشینه ای بیش از نهجالبلاغه شریف رضی (ره) دارد

- ^ Collection of Ali's poems (I Arabic)

- ^ Stearns & Langer 2001, p. 1178

- ^ Tabatabaei 1979, p. 194

- ^ Tabatabaei 1979, p. 196 - 201

- ^ Al-Tabari 1990, p. vol.XIX pp. 178-179

- ^ The Sanctified Household

- ^ List of Martyrs of Karbala by Khansari "فرزندان اميراالمؤمنين(ع): 1-ابوبكربن علي(شهادت او مشكوك است). 2-جعفربن علي. 3-عباس بن علي(ابولفضل) 4-عبدالله بن علي. 5-عبدالله بن علي العباس بن علي. 6-عبدالله بن الاصغر. 7-عثمان بن علي. 8-عمر بن علي. 9-محمد الاصغر بن علي. 10-محمدبن العباس بن علي."

- ^ "Zaynab Bint ʿAlĪ". Encyclopedia of Religion. Gale Group. 2004. Retrieved 2008-04-10.

- ^ Nasr, Shi'ite Islam, preface, p. 10

- ^ Motahhari, Perfect man, Chapter 1

- ^ Trust, p. 695

- ^ Trust, p. 681

- ^ See:

- Peters 2003, p. 320 and 321

- Halm 2004, p. 154- 159

- ^ The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, London, 1911, (originally published 1776-88) volume 5, pp. 381-2

- ^ The Life of Mahomet, London, 1877, p. 250

- ^ Henri Lammens, Fatima and the Daughters of Muhammad, Rome and Paris: Scripta Pontificii Instituti Biblici, 1912. Translation by Ibn Warraq.

- ^ Morteza Motahhari, Islam and Religious Pluralism

- ^ George Jordac, the Voice of Human Justice

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. xi, 19 and 20

- ^

See:

- Dakake 2008, p. 270

- Lawson 2005, p. 59

- ^ Robinson 2003, p. 28 and 34

- ^ Jafarian, Rasul; Translated by Delārām Furādī, Publisher:Message of Thaqalayn

References

- Ahmed, M. Mukarram (2005). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Anmol Publications PVT. LTD. ISBN 8126123397.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Al-Shaykh Al-Mufid (1986). Kitab Al-Irshad: The Book of Guidance into the Lives of the Twelve Imams. Routledge Kegan & Paul. ISBN 0710301510.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Al-Tabari, Muhammad ibn Jarir (1990). History of the Prophets and Kings, translation and commentary issued by R. Stephen Humphreys. SUNY Press. ISBN 0791401545.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) (volume XV.) - Ashraf, Shahid (2005). Encyclopedia of Holy Prophet and Companions. Anmol Publications PVT. LTD. ISBN 8126119403.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Chirri, Mohammad (1982). The Brother of the Prophet Mohammad. Islamic Center of America, Detroit, Michigan. Alibris. ISBN 978-0942778007.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Corbin, Henry (1993) [1964]. History of Islamic Philosophy. London: Kegan Paul International in association with Islamic Publications for The Institute of Ismaili Studies. ISBN 0710304161.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) Translated by Liadain Sherrard, Philip Sherrard. - Dakake, Maria Massi (2008). The Charismatic Community: Shi'ite Identity in Early Islam. SUNY Press. ISBN 0791470334.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Halm, Halm (2004). Shi'ism. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0748618880.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hamidullah, Muhammad (1988). The Prophet's Establishing a State and His Succession. University of California. ISBN 9698016228.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Holt, P.M.; Lambton, Ann K.S.; Lewis, Bernard, eds. (1970). Cambridge History of Islam. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521291356.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kelsay, Jhon (1993). Islam and War: A Study in Comparative Ethics. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 0664253024.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lambton, Ann K. S. (1991). Landlord and Peasant in Persia. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 1850432937.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lawson, Todd, ed. (2005). Reason and Inspiration in Islam: Theology, Philosophy and Mysticism in Muslim Thought. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 1850434700.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lapidus, Ira (2002). A History of Islamic Societies (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521779333.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lewis, Bernard (1991). The Political Language of Islam. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226476936.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Madelung, Wilferd (1997). The Succession to Muhammad: A Study of the Early Caliphate. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521646960.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Merrick, James L. (2005). The Life and Religion of Mohammed as Contained in the Sheeah Traditions. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 1417955368.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Momen, Moojan (1985). An Introduction to Shi‘i Islam: The History and Doctrines of Twelver Shi'ism. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300035314.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nasr, Seyyed Hossein; Dabashi, Hamid; Nasr, Vali (1989). Expectation of the Millennium. Suny press. ISBN 088706843X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nasr, Seyyed Hossein; Leaman, Oliver (1996). History of Islamic Philosophy. Routledge. ISBN 0415131596.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nasr, Seyyed Hossein (2006). Islamic Philosophy from Its Origin to the Present. SUNY Press. ISBN 0791467996.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Peters, F. E. (2003). The Monotheists: Jews, Christians, and Muslims in Conflict and Competition. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691114617.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Qazwini, Muhammad Kazim; Ordoni, Abu Muhammad (1992). Fatima the Gracious. Ansariyan Publications. OCLC 61565460.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Redha, Mohammad (1999). Imam Ali Ibn Abi Taleb (Imam Ali the Fourth Caliph, 1/1 Volume). Dar Al Kotob Al ilmiyah. ISBN 2-7451-2532-X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Robinson, Chase F. (2003). Islamic Historiography. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521629365.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shaban, Muḥammad ʻAbd al-Ḥayy (1971). Islamic History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521291313.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shah-Kazemi, Reza (2007). Justice and Remembrance: Introducing the Spirituality of Imam Ali. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 1845115260.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Singh, N.K. (2003). Prophet Muhammad and His Companions. Global Vision Publishing Ho. ISBN 9788187746461.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stearns, Peter N.; Langer, William Leonard (2001). The Encyclopedia of World History: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern. Houghton Mifflin Books. ISBN 0395652375.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tabatabaei, Sayyid Mohammad Hosayn (1979). Shi'ite Islam. Suny press. ISBN 0-87395-272-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)| Translated by Seyyed Hossein Nasr. - Tabatabaei, Sayyid Mohammad Hosayn (1987). The Qur'an in Islam: Its Impact and Influence on the Life of Muslims. Zahra. ISBN 0710302657.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Watt, William Montgomery (1953). Muhammad at Mecca. Oxford University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Zeitlin, Irving M. (2007). The Historical Muhammad. Polity. ISBN 0745639984.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

Original sources

- Al-Bukhari, Muhammad. Sahih Bukhari, Book 4, 5, 8.

- Ali ibn Abi Talib (1984). Nahj al-Balagha (Peak of Eloquence), compiled by ash-Sharif ar-Radi. Alhoda UK. ISBN 0940368439.

- Ali ibn al-Athir. In his Biography, vol 2.

- Ibn Taymiyyah, Taqi ad-Din Ahmad. Minhaj as-Sunnah an-Nabawiyyah.(In Arabic)

- Muslim ibn al-Hajjaj. Sahih Muslim, Book 19, 31.

Secondary sources

- Books

- Abdul Rauf, Muhammad (1996). Imam 'Ali ibn Abi Talib: The First Intellectual Muslim Thinker. Al Saadawi Publications. ISBN 1881963497.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Al-Tabari, Muhammad ibn Jarir (1987 to 1996). History of the Prophets and Kings, translation and commentary issued in multiple volumes. SUNY Press.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) volumes 6-17 are relevant. - Motahhari, Murtaza (1981). Polarization Around the Character of 'Ali ibn Abi Talib. World Organization for Islamic Services, Tehran.

- Cleary, Thomas (1996). Living and Dying with Grace: Counsels of Hadrat Ali. Shambhala Publications, Incorporated. ISBN 1570622116.

- Corn, Patricia (2005). Medieval Islamic Political Thought. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0748621946.

- Gordagh, George (1956). Ali, The Voice of Human Justice. ISBN 0-941724-24-7.(in Arabic)

- Khatab, Amal (1996). Battles of Badr and Uhud. Ta-Ha Publishers. ISBN 1-897940-39-4.

- Kattani, Sulayman (1983). Imam 'Ali: Source of Light, Wisdom and Might, translation by I.K.A. Howard. Muhammadi Trust of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. ISBN 0950698660.

- Lakhani, M. Ali. (2007). The Sacred Foundations of Justice in Islam: The Teachings of Ali Ibn Abi Talib, Contributor Dr Seyyed Hossein Nasr. World Wisdom, Inc. ISBN 1933316268.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Motahhari, Morteza (1997). Glimpses of the Nahj Al-Balaghah, translated by Ali Quli Qara'i. Islamic Culture and Relations Organizati. ISBN 978-9644720710.

- Encyclopedia

- Encyclopaedia of Islam Online. Brill. 2004. E-ISSN 1573-3912.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Martin, Richard C. Encyclopaedia of Islam and the Muslim world; vol.1. MacMillan. ISBN 0028656040.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Encyclopædia Iranica. Center for Iranian Studies, Columbia University. ISBN 1568590504.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Meri, Josef W. (2006). Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0415966914.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Jones, Lindsay (2004). Encyclopedia of Religion. Gale Group. ISBN 9780028657332.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

External links

- The Secret of Imam Ali's Force of Attraction

- Ali ibn Abi Talib by I. K. Poonawala and E. Kohlberg in Encyclopædia Iranica

- Ali, article in Enyclopaedia Britannica Online

- Some of his most famous sermons and letters

- Imam Ali ibn Abi Talib Nahjul Balagha

- Order to Maalik al-Ashtar, governor of Egypt (UN Legal Committee, member states voted that the document should be considered as one of the sources of International Law.) The United Nation and Imam Ali’s Constitution

- A advice ti his son Hasan ib Ali (This letter contains ethical advisement)

- 185 Sermon about the Oneness of Allah

- The Last Will of Ali ibn Abi Talib

- Shī‘a biography

- The Life of the Commander of the Faithful Ali b. Abu Talib by Shaykh Mufid in Kitab al-Irshad

- Website devoted to the Life of Imam Ali ibn Abi Talib

- A Biographical Profile of Imam Ali (Archived 2009-10-25) by Syed Muhammad Askari Jafari

- The Seerat Of Amir al-Mu'mineen (SA)

- Sunni biography