Protestantism

| Part of a series on |

| Protestantism |

|---|

|

|

|

Protestantism encompasses forms of Christian faith and practice that originated with doctrines and religious, political, and ecclesiological impulses of the Protestant Reformation, against what they considered the errors of the Roman Catholic Church. The term refers to the letter of protestation by Lutheran princes against the decision of the Diet of Speyer in 1529, which reaffirmed the edict of the Diet of Worms condemning the teachings of Martin Luther as heresy. Protestantism is reformed Christianity.[1]

The Protestant movement has its origins in Germany and is popularly considered to have begun in 1517 when Luther published The Ninety-Five Theses as a reaction against medieval doctrines and practices, especially with regard to salvation, justification, and ecclesiology. The various Protestant denominations share a rejection of the authority of the pope and generally deny the Roman Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation, although they disagree among themselves about the doctrine of Christ's presence in the Eucharist. They generally emphasize the priesthood of all believers, the doctrine of justification by faith alone (sola fide) apart from good works, and a belief in the Bible alone (rather than with Catholic tradition) as the supreme authority in matters of faith and morals (sola scriptura).

In the 16th century, the followers of Martin Luther established the Lutheran churches of Germany and Scandinavia. Reformed churches in Hungary, Scotland, Switzerland and France were established by other reformers such as John Calvin, Huldrych Zwingli, and John Knox. The Church of England declared independence from papal authority in 1534, and was influenced by some Reformation principles, notably during the reign of Edward VI. There were also reformation movements throughout continental Europe known as the Radical Reformation which gave rise to the Anabaptist, Moravian, and other pietistic movements.

Protestants generally may be divided among: The "mainline" churches with direct roots in the Magisterial Reformation, the churches of the Radical Reformation, and the churches of the Puritan Reformation. There are over 33,000 Protestant denominations, and not every one fits neatly into these categories. Encompassing more than 800 million members, or 37% of world's Christians, Protestantism is present on all populated continents.[2]

A Protestant is a member of one of the several denominations denying the universal authority of the Pope and affirming the Reformation principles: justification by faith alone, the priesthood of all believers, and the primacy of the Bible as the only source of revealed truth and affirming the Nicene creed. [3]

Etymology

The exact origin of the term protestant is uncertain, and may come either from French protestant or German Protestant. However, it is certain that both languages derived their word from the Template:Lang-la, meaning "one who publicly declares/protests",[4] which refers to the protest against some beliefs and practices of the early 16th century Roman Catholic Church. The word "protest" being derived from the Latin prōtestārī, which literally means to testify, or give a public witness.[5]

Fundamental principles

The three fundamental principles of traditional Protestantism are the following:

- Scripture alone

- The belief in the Bible as the supreme source of authority for the church. The early churches of the Reformation believed in a critical, yet serious, reading of scripture and holding the Bible as a source of authority higher than that of church tradition. The many abuses that had occurred in the Western Church prior to the Protestant Reformation led the reformers to reject much of the tradition of the Western Church, though some would maintain tradition has been maintained and reorganized in the liturgy and in the confessions of the Protestant churches of the Reformation. In the early 20th century there developed a less critical reading of the Bible in the United States that has led to a "fundamentalist" reading of scripture. Christian fundamentalists read the Bible as the "inerrant, infallible" word of God, as do the Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Anglican churches, to name a few, but interpret it in a more literal way.

- Justification by faith alone

- "The subjective principle of the Reformation is justification by faith alone, or, rather, by free grace through faith operative in good works. It has reference to the personal appropriation of the Christian salvation and aims to give all glory to Christ by declaring that the sinner is justified before God (i.e., is acquitted of guilt and declared righteous) solely on the ground of the all-sufficient merits of Christ as apprehended by a living faith, in opposition to the theory — then prevalent and substantially sanctioned by the Council of Trent — which makes faith and good works coordinate sources of justification, laying the chief stress upon works. Protestantism does not depreciate good works, but it denies their value as sources or conditions of justification and insists on them as the necessary fruits of faith and evidence of justification."[6]

- Universal priesthood of believers

- The universal priesthood of believers implies the right and duty of the Christian laity not only to read the Bible in the vernacular, but also to take part in the government and all the public affairs of the Church. It is opposed to the hierarchical system which puts the essence and authority of the Church in an exclusive priesthood, and makes ordained priests the necessary mediators between God and the people.[6]

Theology

Protestants/Evangelicals/Reformed adhere to the Nicene Creed. Protestants believe in 3 "Persons", God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit, as one God.

The Ninety-Five Theses

In 1517, Martin Luther, a German Augustinian friar, published The Ninety-Five Theses. Popular history holds that these theses were nailed to a church door in the university town of Wittenberg by Luther himself, but this claim has recently come under scrutiny (see article on Martin Luther for discussion). Luther's propositions challenged some portions of Catholic doctrine and a number of specific practices.

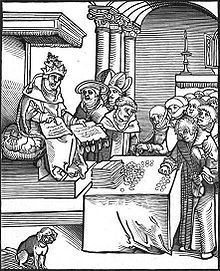

Luther was particularly criticizing a common church practice of the day, the selling of indulgences. In Catholic theology, an indulgence is the full or partial remission of temporal punishment due for sins which have already been forgiven. However, Pope Leo X had declared that indulgences were not only for the remission of temporal punishment, but also for guilt itself.[citation needed] To Luther, it appeared that selling indulgences was tantamount to selling salvation, something that he felt was against both biblical teaching and Catholic doctrine. At the time, Rome was using the sale of indulgences as a means to raise money for a massive church project, the construction of St. Peter's Basilica.

The Disputation of Doctor Martin Luther on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences (commonly known as The Ninety-Five Theses)[7] was a request for a formal disputation that criticized the practice of selling indulgences. This kind of disputation was a common academic exercise during this era. Luther maintained that justification (salvation) was granted by faith alone, saying that good works and the sacraments were not necessary in order to be saved. A copy of the disputation eventually made it to the hands of the regional bishop, who in turn forwarded the disputation to Rome.[8]

Five solae

| Five solae of the Protestant Reformation |

|---|

| Sola scriptura |

| Sola fide |

| Sola gratia |

| Solus Christus |

| Soli Deo gloria |

The Five solae are five Latin phrases (or slogans) that emerged during the Protestant Reformation and summarize the reformers' basic differences in theological beliefs in opposition to the teaching of the Catholic Church of the day. The Latin word sola means "alone", "only", or "single".

The use of the phrases as summaries of teaching emerged over time during the reformation, based on the overarching principle of sola scriptura (by scripture alone). This idea contains the four main doctrines on the Bible: that its teaching is needed for salvation (necessity); that all the doctrine necessary for salvation comes from the Bible alone (sufficiency); that everything taught in the Bible is correct (inerrancy); and that, by the Holy Spirit overcoming sin, believers may read and understand truth from the Bible itself, though understanding is difficult, so the means used to guide individual believers to the true teaching is often mutual discussion within the church (clarity).

The necessity and inerrancy were well-established ideas, garnering little criticism, though they later came under debate from outside during the Enlightenment. The most contentious idea at the time though was the notion that anyone could simply pick up the Bible and learn enough to gain salvation. Though the reformers were concerned with ecclesiology (the doctrine of how the church as a body works), they had a different understanding of the process in which truths in scripture were applied to life of believers, compared to the Catholics' idea that certain people within the church, or ideas that were old enough, had a special status in giving understanding of the text.

The second main principle, sola fide (by faith alone), states that faith in Christ is sufficient alone for eternal salvation. Though argued from scripture, and hence logically consequent to sola scriptura, this is the guiding principle of the work of Luther and the later reformers. Because sola scriptura placed the Bible as the only source of teaching, sola fide epitomises the main thrust of the teaching the reformers wanted to get back to, namely the direct, close, personal connection between Christ and the believer, hence the reformers' contention that their work was Christocentric.

The other solas, as statements, emerged later, but the thinking they represent was also part of the early reformation.

- Solus Christus: Christ alone.

- The Protestants characterize the dogma concerning the Pope as Christ's representative head of the Church on earth, the concept of works made meritorious by Christ, and the Catholic idea of a treasury of the merits of Christ and his saints, as a denial that Christ is the only mediator between God and man. Catholics, on the other hand, maintained the traditional understanding of Judaism on these questions, and appealed to the universal consensus of Christian tradition.[9]

- Sola Gratia: Grace alone.

- Protestants perceived Roman Catholic salvation to be dependent upon the grace of God and the merits of one's own works. The reformers posited that salvation is a gift of God (i.e., God's act of free grace), dispensed by the Holy Spirit owing to the redemptive work of Jesus Christ alone. Consequently, they argued that a sinner is not accepted by God on account of the change wrought in the believer by God's grace, and that the believer is accepted without regard for the merit of his works, for no one deserves salvation.Matt. 7:21

- Soli Deo Gloria: Glory to God alone

- All glory is due to God alone since salvation is accomplished solely through his will and action — not only the gift of the all-sufficient atonement of Jesus on the cross but also the gift of faith in that atonement, created in the heart of the believer by the Holy Spirit. The reformers believed that human beings — even saints canonized by the Catholic Church, the popes, and the ecclesiastical hierarchy — are not worthy of the glory.

Christ's presence in the Eucharist

The Protestant movement began to diverge into several distinct branches in the mid-to-late 16th century. One of the central points of divergence was controversy over the Eucharist. Early Protestants rejected the Roman Catholic dogma of transubstantiation, which teaches that the bread and wine used in the sacrificial rite of the Mass lose their natural substance by being transformed into the body, blood, soul, and divinity of Christ. They disagreed with one another concerning the presence of Christ and his body and blood in Holy Communion.

- Lutherans hold that within the Lord's Supper the consecrated elements of bread and wine are the true body and blood of Christ "in, with, and under the form" of bread and wine for all those who eat and drink it,1Cor 10:16 11:20,27 [10] a doctrine that the Formula of Concord calls the Sacramental union.[11] God earnestly offers to all who receive the sacrament,Lk 22:19–20[12] forgiveness of sins,Mt 26:28[13] and eternal salvation.[14]

- The reformed closest to Calvin emphasize the real presence, or sacramental presence, of Christ, saying that the sacrament is a means of saving grace through which only the elect believer actually partakes of Christ, but merely with the bread and wine rather than in the elements. Calvinists deny the Lutheran assertion that all communicants, both believers and unbelievers, orally receive Christ's body and blood in the elements of the sacrament but instead affirm that Christ is united to the believer through faith — toward which the supper is an outward and visible aid. This is often referred to as dynamic presence.

- A Protestant holding a popular simplification of the Zwinglian view, without concern for theological intricacies as hinted at above, may see the Lord's Supper merely as a symbol of the shared faith of the participants, a commemoration of the facts of the crucifixion, and a reminder of their standing together as the body of Christ (a view referred to somewhat derisively as memorialism).

History

Proto-Reformation

- 12th century

- Peter Waldo, founder of the Waldensians, proto-reformed group that continues to exist to this day in Italy.

- 14th century

- John Wycliffe, English reformer, the "Morning Star of Reformation".

- 15th century

- Jan Hus, Roman Catholic priest and professor, influenced by John Wycliff's writings, founder of an early Protestant church (Moravians), Czech reformist/dissident; burned to death in Constance, Holy Roman Empire in 1415 by Roman Catholic Church authorities "for unrepentant and persistent heresy." After the devastations of the Hussite Wars some of his followers founded the Unitas Fratrum in 1457, "Unity of the Brethren", which was renewed under the leadership of Count Zinzendorf in Herrnhut, Saxony in 1722 after its almost total destruction in the 30 Years War and Counter-Reformation. Today it is usually referred to in English as the Moravian Church, in German the Herrnhuter Brüdergemeinde.

Reformation proper

- 16th century

- Jacobus Arminius, Dutch theologian, founder of school of thought known as Arminianism

- Heinrich Bullinger, successor of Zwingli, leading reformed theologian

- John Calvin, French theologian, reformer and resident of Geneva, Switzerland, he founded the school of theology known as Calvinism

- Balthasar Hubmaier, influential Anabaptist theologian, author of numerous works during his five years of ministry, tortured at Zwingli's behest, and executed in Vienna

- John Knox, Scottish Calvinist and leader of the Scottish Reformation

- Martin Luther, church reformer and founder of Protestantism whose theological works guided those now known as Lutherans

- Philipp Melanchthon, early Lutheran leader

- Menno Simons, Anabaptist leader who, through his writings, articulated and thereby formalized Mennonitism

- John Smyth, early Baptist leader

- Huldrych Zwingli, founder of Swiss Reformed tradition

The Protestant Reformation of the early 16th century began as an attempt to reform the Roman Catholic Church. German theologian Martin Luther wrote his Ninety-Five Theses on the sale of indulgences in 1517. Parallel to events in Germany, a movement began in Switzerland under the leadership of Ulrich Zwingli. The political separation of the Church of England from Rome under Henry VIII, beginning in 1529 and completed in 1536, brought England alongside this broad reformed movement. The Scottish Reformation of 1560 decisively shaped the Church of Scotland[15] and, through it, all other Presbyterian churches worldwide.

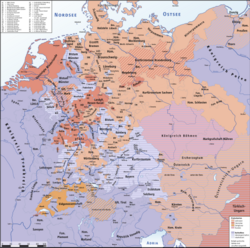

Following the excommunication of Luther and condemnation of the Reformation by the Pope, the work and writings of John Calvin were influential in establishing a loose consensus among various groups in Switzerland, Scotland, Hungary, Germany and elsewhere. In the course of this religious upheaval, the German Peasants' War of 1524–1525 swept through the Bavarian, Thuringian and Swabian principalities. After the Eighty Years' War (1568–1648) in the Low Countries and the French Wars of Religion (1562–1598), the confessional division of the states of the Holy Roman Empire eventually erupted in the Thirty Years' War of 1618–1648. This left Germany weakened and fragmented for more than two centuries, until the unification of Germany under the German Empire of 1871.

The success of the Counter-Reformation on the continent and the growth of a Puritan party dedicated to further protestant reform polarized the Elizabethan Age, although it was not until the Civil War of the 1640s that England underwent religious strife comparable to that which its neighbours had suffered some generations before.

The "Great Awakenings" were periods of rapid and dramatic religious revival in Anglo-American religious history, generally recognized as beginning in the 1730s. They have also been described as periodic revolutions in colonial religious thought.

Mainstream Protestantism began with the Magisterial Reformation, so called because the movement received support from the magistrates (that is, the civil authorities.

In the 20th century, Protestantism, especially in the United States, was characterized by accelerating fragmentation. The century saw the rise of both liberal and conservative splinter groups, as well as a general secularization of Western society. Notable developments in the 20th century of American protestantism were the rise of Pentecostalism, Christian fundamentalism and Evangelicalism. While these movements have spilled over to Europe to a limited degree, the development of protestantism in Europe was more dominated by secularization, leading to an increasingly "post-Christian Europe".

Radical Reformation

Unlike mainstream Protestant/Evangelical (Lutheran) and Protestant/Evangelical/Reformed (Calvinist, Zwinglian) movements, the Radical Reformation, which had no state sponsorship, generally abandoned the idea of the "Church visible" as distinct from the "Church invisible". It was a rational extension of the state-approved Protestant dissent, which took the value of independence from constituted authority a step further, arguing the same for the civic realm. The Radical Reformation was non-mainstream.

Protestant ecclesial leaders such as Hubmaier and Hofmann preached the invalidity of infant baptism, advocating baptism as following conversion ("believer's baptism") instead. This was not a doctrine new to the reformers, but was taught by earlier groups, such as the Albigenses in 1147.[citation needed]

In the view of many associated with the Radical Reformation, the Magisterial Reformation had not gone far enough. Radical Reformer, Andreas von Bodenstein Karlstadt, for example, referred to the Lutheran theologians at Wittenberg as the "new papists".[16] Since the term "magister" also means "teacher", the Magisterial Reformation is also characterized by an emphasis on the authority of a teacher. This is made evident in the prominence of Luther, Calvin, and Zwingli as leaders of the reform movements in their respective areas of ministry. Because of their authority, they were often criticized by Radical Reformers as being too much like the Roman Popes. A more political side of the Radical Reformation can be seen in the thought and practice of Hans Hut, although typically Anabaptism has been associated with pacifism.

Denominations

Protestants refer to specific groupings of churches that share in common foundational doctrines and the name of their groups as "denominations". Protestants reject the Roman Catholic doctrine that it is the one true church. Some Protestant denominations are less accepting of other denominations, and the basic orthodoxy of some is questioned by most of the others. Individual denominations also have formed over very subtle theological differences. Other denominations are simply regional or ethnic expressions of the same beliefs. Because the five solas are the main tenets of the Protestant faith, Non-denominational groups and organizations are also considered Protestant. Due to all these factors, an exact count is not possible, but it is estimated that there are approximately 33,000 Protestant denominations.[17]

Various ecumenical movements have attempted cooperation or reorganization of the various divided Protestant denominations, according to various models of union, but divisions continue to outpace unions, as there is no overarching authority to which any of the churches owe allegiance, which can authoritatively define the faith. Most denominations share common beliefs in the major aspects of the Christian faith while differing in many secondary doctrines, although what is major and what is secondary is a matter of idiosyncratic belief.

There are about 800 million Protestants worldwide,[18] among approximately 2.1 billion Christians.[19][20] These include 170 million in North America, 160 million in Africa, 120 million in Europe, 70 million in Latin America, 60 million in Asia, and 10 million in Oceania. United States is home to approximately 20% of Protestants.[21]

Denominational Families

| Christian denominations in the English-speaking world |

|---|

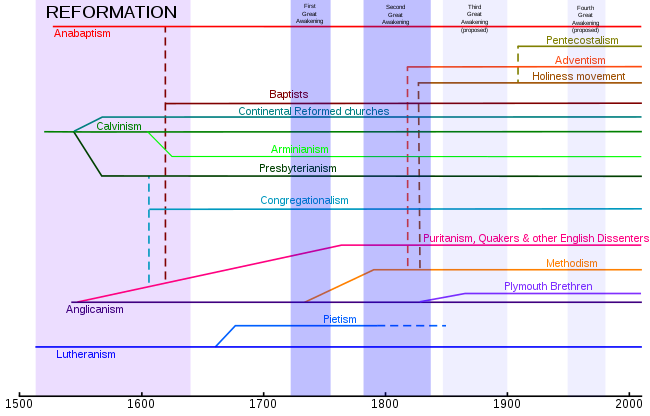

Protestants can be differentiated according to how they have been influenced by important movements since the Magisterial Reformation, Radical Reformation and the Puritan Reformation. Some of these movements have a common lineage, sometimes directly spawning individual denominations within denominational families. Only denominational families are listed below (due to the earlier stated multitude of denominations).

Historical chart

Catholic and Orthodox view on Protestant denominations

The view of the Roman Catholic Church is that Protestant denominations cannot be considered "churches" but rather that they are ecclesial communities or "specific faith-believing communities" because their ordinances and doctrines are not historically the same as the Catholic sacraments and dogmas, and the Protestant communities have no sacramental ministerial priesthood and therefore lack true apostolic succession.[22][23] According to Bishop Hilarion (Alfeyev) the Orthodox Catholic Church shares the same view on the subject.[24]

Contrary to how the Protestant Reformers were often characterized, the concept of a catholic or universal Church was not brushed aside during the Protestant Reformation. On the contrary, the visible unity of the catholic or universal Church was seen by the Reformers as an important and essential doctrine of the Reformation. The Magisterial Reformers, such as Martin Luther, John Calvin, and Ulrich Zwingli, believed that they were "reforming" the Roman Catholic Church, which they viewed as having become corrupted. Each of them took very seriously the charges of schism and innovation, denying these charges and maintaining that it was the Roman Catholic Church that had left them.[25] In order to justify their departure from the Roman Catholic Church, Protestants often posited a new argument, saying that there was no real visible Church with divine authority, only a "spiritual", "invisible", and "hidden" church— this notion began in the early days of the Protestant Reformation.[citation needed]

Wherever the Magisterial Reformation, which received support from the ruling authorities, took place, the result was a reformed national Protestant church envisioned to be a part of the whole "invisible church", but disagreeing, in certain important points of doctrine and doctrine-linked practice, with what had until then been considered the normative reference point on such matters, namely the Papacy and central authority of the Roman Catholic Church. The Reformed churches thus believed in some form of Catholicity, founded on their doctrines of the five solas and a visible ecclesiastical organization based on the 14th and 15th century Conciliar movement, rejecting the papacy and papal infallibility in favor of ecumenical councils, but rejecting the latest ecumenical council, the Council of Trent. Religious unity therefore became not one of doctrine and identity but one of invisible character, wherein the unity was one of faith in Jesus Christ, not common identity, doctrine, belief, and collaborative action. The Roman Catholic Church, citing corinthians 1:10-13 1Corinthians 1:10–13, 4:1-6 Ephesians 4:1–6, 2:1-2 Philippians 2:1–2, and peter 3:8 1Peter 3:8, opposed this view. citation needed

Today there is a growing movement of Protestants, especially of the Calvinist tradition, that either reject or down-play the designation "Protestant" because of the negative idea that the word invokes in addition to its primary meaning, preferring the designation "Reformed", "Evangelical" or even "Reformed Catholic" expressive of what they call a "Reformed Catholicity" and defending their arguments from the traditional Protestant confessions.[26]

Movements

Anglicanism

The original separation of the Church of England (then including the Wales) and the Church of Ireland from Rome under King Henry VIII was largely political and its religious dimension smaller than some historians have assumed.[27] Apart from the introduction of the vernacular "Great Bible" in 1539 and a few minor changes, official stances on Christian faith and practice remained virtually unchanged until Henry's death.[28] A "programme of coherent Protestant reform" was implemented after his death by the Privy Council, its chief component being Cranmer's two Books of Common Prayer of 1549 and 1552.[28] This reform was reversed by Mary I (1553-8) but restored in a slightly more conservative shape by Elizabeth I in 1559, who resisted all attempts to move the Church of England towards a more extreme form of Protestantism.[28]

In the 19th century some of the Tractarians argued that the Church of England and the other Anglican churches were not Protestant but a "reformed Catholic" or middle path (via media) between Rome and Protestantism. This assertion was attacked by, among others, the Church Association.[29] Today, the Anglican Communion continues to be composed of theologically diverse traditions, from reformed Sydney Anglicanism to Anglo-Catholicism, but the general understanding of its position is now that it contains both "Catholic" and "Protestant" elements of doctrine and practice.[30]

Pietism and Methodism

The German Pietist movement, together with the influence of the Puritan Reformation in England in the 17th century, were important influences upon John Wesley and Methodism, as well as new groups such as the Religious Society of Friends ("Quakers") and the Moravian Brethren from Herrnhut, Saxony, Germany.

The practice of a spiritual life, typically combined with social engagement, predominates in classical Pietism, which was a protest against the doctrine-centered "Protestant orthodoxy" of the times, in favor of depth of religious experience. Many of the more conservative Methodists went on to form the Holiness movement, which emphasized a rigorous experience of holiness in practical, daily life.

Evangelicalism

Beginning at the end of 18th century, several international revivals of Pietism (such as the Great Awakening and the Second Great Awakening) took place across denominational lines, largely in the English-speaking world. Their teachings and successor groupings are referred to generally as the Evangelical movement. The chief emphases of this movement were individual conversion, personal piety and Bible study, public morality often including temperance and abolitionism, de-emphasis of formalism in worship and in doctrine, a broadened role for laity (including women)[citation needed] in worship, evangelism and teaching, and cooperation in evangelism across denominational lines. Some of the major figures in this movement include Billy Graham, Harold John Ockenga, John Stott, and Martyn Lloyd-Jones.

During the 20th century evangelicals reacted to perceived excesses of Christian fundamentalism, adding to concern for biblical authority, an emphasis on liberal arts, cooperation among churches, Christian apologetics, and non-denominational evangelization.

Adventism

Adventism is a Christian movement which began in the 19th century, in the context of the Second Great Awakening in the United States. The name refers to belief in the imminent Second Coming (or "Second Advent") of Jesus Christ. It was started by Baptist minister William Miller, whose followers became known as Millerites. Today, the largest church within the movement is the Seventh-day Adventist Church.

The Adventist family of churches is regarded today as conservative.[31] Although these churches hold much in common, their theology differs on whether the intermediate state is unconscious sleep or consciousness, whether the ultimate punishment of the wicked is annihilation or eternal torment, the nature of immortality, whether or not the wicked are resurrected after the millennium, and whether the sanctuary of Daniel 8 refers to the one in heaven or one on earth.[31] The movement has encouraged examination of the New Testament, leading it to observe the Sabbath.

Modernism and Liberalism

Modernism and liberalism do not constitute rigorous and well-defined schools of theology, but are rather an inclination by some writers and teachers to integrate Christian thought into the spirit of the Age of Enlightenment. New understandings of history and the natural sciences of the day led directly to new approaches to theology.

Pentecostalism

Pentecostalism, as a movement, began in the United States early in the 20th century, starting especially within the Holiness movement. Seeking a return to the operation of New Testament gifts of the Holy Spirit, speaking in tongues as evidence of the "baptism of the Holy Ghost" or to make the unbeliever believe became the leading feature. Divine healing and miracles were also emphasized. Pentecostalism swept through much of the Holiness movement, and eventually spawned hundreds of new denominations in the United States. A later "charismatic" movement also stressed the gifts of the Spirit, but often operated within existing denominations, rather than by coming out of them.

Fundamentalism

In reaction to liberal Bible critique, fundamentalism arose in the 20th century, primarily in the United States, among those denominations most affected by Evangelicalism. Fundamentalist theology tends to stress Biblical inerrancy and Biblical literalism.

Toward the end of the 20th century, some have tended to confuse evangelicalism and fundamentalism, however the labels represent very distinct differences of approach that both groups are diligent to maintain, although because of fundamentalism's dramatically smaller size it often gets classified simply as an ultra-conservative branch of evangelicalism.

Neo-orthodoxy and Paleo-orthodoxy

A non-fundamentalist rejection of liberal Christianity, associated primarily with Karl Barth and Jürgen Moltmann, neo-orthodoxy sought to counter-act the tendency of liberal theology to make theological accommodations to modern scientific perspectives. Sometimes called "Crisis theology", according to the influence of philosophical existentialism on some important segments of the movement; also, somewhat confusingly, sometimes called neo-evangelicalism.

Paleo-orthodoxy is a movement similar in some respects to neo-evangelicalism but emphasizing the ancient Christian consensus of the undivided church of the first millennium AD, including in particular the early creeds and church councils as a means of properly understanding the scriptures. This movement is cross-denominational and the most notable exponent in the movement is United Methodist theologian Thomas Oden.

Protestant culture

Although the Reformation was a religious movement, it also had a strong impact on all other aspects of life: marriage and family, education, the humanities and sciences, the political and social order, the economy, and the arts.[32] All Protestant churches allow their clergy to marry. Many of their families contributed to the development of intellectual elites in their countries.[33] Since about 1950, women have entered the ministry, and some have assumed leading positions (e.g. bishops), in most Protestant churches.

As the reformers wanted all members of the church to be able to read the Bible, education on all levels got a strong boost. For example, the Puritans who established Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1628 founded Harvard College only eight years later. About a dozen other colleges followed in the 18th century, including Yale (1701). Pennsylvania also became a centre of learning.[34][35]

The Protestant concept of God and man allows believers to use all their God-given faculties, including the power of reason. That means that they are allowed to explore God's creation and, according to Genesis 2:15, make use of it in a responsible and sustainable way. Thus a cultural climate was created that greatly enhanced the development of the humanities and the sciences.[36] Another consequence of the Protestant understanding of man is that the believers, in gratitude for their election and redemption in Christ, are to follow God's commandments. Industry, frugality, calling, discipline, and a strong sense of responsibility are at the heart of their moral code.[37][38] In particular, Calvin rejected luxury. Therefore craftsmen, industrialists, and other businessmen were able to reinvest the greater part of their profits in the most efficient machinery and the most modern production methods that were based on progress in the sciences and technology. As a result, productivity grew, which led to increased profits and enabled employers to pay higher wages. In this way, the economy, the sciences, and technology reinforced each other. The chance to participate in the economic success of technological inventions was a strong incentive to both inventors and investors.[39][40][41][42] The Protestant work ethic was an important force behind the unplanned and uncoordinated mass action that influenced the development of capitalism and the Industrial Revolution. This idea is also known as the "Protestant ethic thesis."[43]

Protestantism has had an important influence on science. According to the Merton Thesis, there was a positive correlation between the rise of English Puritanism and German Pietism on the one hand and early experimental science on the other.[44] The Merton Thesis has two separate parts: Firstly, it presents a theory that science changes due to an accumulation of observations and improvement in experimental technique and methodology; secondly, it puts forward the argument that the popularity of science in 17th-century England and the religious demography of the Royal Society (English scientists of that time were predominantly Puritans or other Protestants) can be explained by a correlation between Protestantism and the scientific values.[45] Merton focused on English Puritanism and German Pietism as having been responsible for the development of the scientific revolution of the 17th and 18th centuries. He explained that the connection between religious affiliation and interest in science was the result of a significant synergy between the ascetic Protestant values and those of modern science.[46] Protestant values encouraged scientific research by allowing science to identify God's influence on the world - his creation - and thus providing a religious justification for scientific research.[44]

In the Middle Ages, the Church and the worldly authorities were closely related. Martin Luther separated the religious and the worldly realms in principle (doctrine of the two kingdoms).[47] The believers were obliged to use reason to govern the worldly sphere in an orderly and peaceful way. Luther's doctrine of the priesthood of all believers upgraded the role of laymen in the church considerably. The members of a congregation had the right to elect a minister and, if necessary, to vote for his dismissal (Treatise On the right and authority of a Christian assembly or congregation to judge all doctrines and to call, install and dismiss teachers, as testified in Scripture; 1523).[48] Calvin strengthened this basically democratic approach by including elected laymen (church elders, presbyters) in his representative church government.[49] The Huguenots added regional synods and a national synod, whose members were elected by the congregations, to Calvin's system of church self-government. This system was taken over by the other reformed churches.[50]

Politically, Calvin favoured a mixture of aristocracy and democracy. He appreciated the advantages of democracy: "It is an invaluable gift, if God allows a people to freely elect its own authorities and overlords."[51] Calvin also thought that earthly rulers lose their divine right and must be put down when they rise up against God. To further protect the rights of ordinary people, Calvin suggested separating political powers in a system of checks and balances (separation of powers). Thus he and his followers resisted political absolutism and paved the way for the rise of modern democracy.[52] Besides England, the Netherlands were, under Calvinist leadership, the freest country in Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. It granted asylum to philosophers like Baruch Spinoza and Pierre Bayle. Hugo Grotius was able to teach his natural-law theory and a relatively liberal interpretation of the Bible.[53]

Consistent with Calvin's political ideas, Protestants created both the English and the American democracies. In seventeenth-century England, the most important persons and events in this process were the English Civil War, Oliver Cromwell, John Milton, John Locke, the Glorious Revolution, the English Bill of Rights, and the Act of Settlement.[54] Later, the British took their democratic ideals to their colonies, e.g. Australia, New Zealand, and India. In North America, Plymouth Colony (Pilgrim Fathers; 1620) and Massachusetts Bay Colony (1628) practised democratic self-rule and separation of powers.[55][56][57][58] These Congregationalists were convinced that the democratic form of government was the will of God.[59] The Mayflower Compact was a social contract.[60][61]

Protestants also took the initiative in creating religious freedom, the starting-point of human rights. Freedom of conscience had had high priority on the theological, philosophical, and political agendas since Luther refused to recant his beliefs before the Diet of the Holy Roman Empire at Worms (1521). In his view, faith was a free work of the Holy Spirit and could therefore not be forced on a person.[62] The persecuted Anabaptists and Huguenots demanded freedom of conscience, and they practised separation of church and state.[63] In the early seventeenth century, Baptists like John Smyth and Thomas Helwys published tracts in defence of religious freedom.[64] Their thinking influenced John Milton and John Locke's stance on tolerance.[65][66] Under the leadership of Baptist Roger Williams, Congregationalist Thomas Hooker, and Quaker William Penn, respectively, Rhode Island, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania combined democratic constitutions with freedom of religion. These colonies became safe havens for persecuted religious minorities, including Jews.[67][68][69] The United States Declaration of Independence, the United States Constitution, and the American Bill of Rights with its fundamental human rights made this tradition permanent by giving it a legal and political framework.[70] The great majority of American Protestants, both clergy and laity, strongly supported the independence movement. All major Protestant churches were represented in the First and Second Continental Congresses.[71] In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the American democracy became a model for numerous other countries and regions throughout the world (e.g., Latin America, Japan, and Germany). The strongest link between the American and French Revolutions was Marquis de Lafayette, an ardent supporter of the American constitutional principles. The French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen was mainly based on Lafayette’s draft of this document.[72] The United Nations Declaration and Universal Declaration of Human Rights also echo the American constitutional tradition.[73][74][75]

Democracy, social-contract theory, separation of powers, religious freedom, separation of church and state – these achievements of the Reformation and early Protestantism were elaborated on and popularized by Enlightenment thinkers. The philosophers of the English, Scottish, German, and Swiss Enlightenment - Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, John Toland, David Hume, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Christian Wolff, Immanuel Kant, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau - had a Protestant background.[76] For example, John Locke, whose political thought was based on "a set of Protestant Christian assumptions",[77] derived the equality of all humans, including the equality of the genders ("Adam and Eve"), from Genesis 1, 26-28. As all persons were created equally free, all governments needed the consent of the governed.[78] These Lockean ideas were fundamental to the United States Declaration of Independence, which also deduced human rights from the biblical belief in creation: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.” These rights were theonomous ideas (theonomy).[79]

Also, other human rights were initiated by Protestants. For example, torture was abolished in Prussia in 1740, slavery in Britain in 1834 and in the United States in 1865 (William Wilberforce, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Abraham Lincoln).[80][81] Hugo Grotius and Samuel Pufendorf were among the first thinkers who made significant contributions to international law.[82][83] The Geneva Convention, an important part of humanitarian international law, was largely the work of Henry Dunant, a reformed pietist. He also founded the Red Cross.[84]

Protestants have founded hospitals, homes for disabled or elderly people, educational institutions, organizations that give aid to developing countries, and other social welfare agencies.[85][86][87] In the nineteenth century, throughout the Anglo-American world, numerous dedicated members of all Protestant denominations were active in social reform movements such as the abolition of slavery, prison reforms, and woman suffrage.[88][89][90] As an answer to the "social question" of the nineteenth century, Germany under Chancellor Otto von Bismarck introduced insurance programs that led the way to the welfare state (health insurance, accident insurance, disability insurance, old-age pensions). To Bismarck this was "practical Christianity".[91][92] These programs, too, were copied by many other nations, particularly in the Western world.

The arts have been strongly inspired by Protestant beliefs. Martin Luther, Paul Gerhardt, George Wither, Isaac Watts, Charles Wesley, William Cowper, and many other authors and composers created well-known church hymns. Musicians like Heinrich Schütz, Johann Sebastian Bach, George Frideric Handel, Henry Purcell, Johannes Brahms, and Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy composed great works of music. Prominent painters with Protestant background were, for example, Albrecht Dürer, Hans Holbein the Younger, Lucas Cranach, Rembrandt, and Vincent van Gogh. World literature was enriched by the works of Edmund Spenser, John Milton, John Bunyan, John Donne, John Dryden, Daniel Defoe, William Wordsworth, Jonathan Swift, Johann Wolfgang Goethe, Friedrich Schiller, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Edgar Allan Poe, Matthew Arnold, Conrad Ferdinand Meyer, Theodor Fontane, Washington Irving, Robert Browning, Emily Dickinson, Emily Brontë, Charles Dickens, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Thomas Stearns Eliot, John Galsworthy, Thomas Mann, William Faulkner, John Updike, and many others.

Ecumenism

The ecumenical movement has had an influence on mainline churches, beginning at least in 1910 with the Edinburgh Missionary Conference. Its origins lay in the recognition of the need for cooperation on the mission field in Africa, Asia and Oceania. Since 1948, the World Council of Churches has been influential, but ineffective in creating a united church. There are also ecumenical bodies at regional, national and local levels across the globe; but schisms still far outnumber unifications. One, but not the only expression of the ecumenical movement, has been the move to form united churches, such as the Church of South India, the Church of North India, the US-based United Church of Christ, the United Church of Canada, the Uniting Church in Australia and the United Church of Christ in the Philippines which have rapidly declining memberships. There has been a strong engagement of Orthodox churches in the ecumenical movement, though the reaction of individual Orthodox theologians has ranged from tentative approval of the aim of Christian unity to outright condemnation of the perceived effect of watering down Orthodox doctrine.[93]

A Protestant baptism is held to be valid by the Catholic Church if given with the trinitarian formula and with the intent to baptize. However, as the ordination of Protestant ministers is not recognized due to the lack of apostolic succession and the disunity from Catholic Church, all other sacraments (except marriage) performed by Protestant denominations and ministers are not recognized as valid. Therefore, Protestants desiring full communion with the Catholic Church are not re-baptized (although they are confirmed) and Protestant ministers who become Catholics may be ordained to the priesthood after a period of study.

In 1999, the representatives of Lutheran World Federation and Catholic Church signed the Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification, apparently resolving the conflict over the nature of justification which was at the root of the Protestant Reformation, although Confessional Lutherans reject this statement.[94] This is understandable, since there is no compelling authority within them. On July 18, 2006, delegates to the World Methodist Conference voted unanimously to adopt the Joint Declaration.[95][96]

See also

- Anti-Catholicism

- Anti-Protestantism

- European Wars of Religion

- Islam and Protestantism

- List of Protestant churches

- Protestant work ethic

- Mormonism

References

- ^ http://atheism.about.com/library/glossary/western/bldef_reformation.htm.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Pewforum: Christianity (2010)

- ^ http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/protestant?show=0&t=1399262487.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary". Retrieved 7 April 2012.

- ^ Protest - Dictionary Reference. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- ^ a b Johann Jakob Herzog, Philip Schaff, Albert. The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge. 1911, page 419. http://books.google.com/books?id=AmYAAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA419

- ^ Luther, Martin (1517). Disputation of Doctor Martin Luther on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences. Wittenburg.

- ^ "The Protestant Reformation". Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ^ Matt. 16:18, 1 Cor. 3:11, Eph. 2:20, 1 Pet. 2:5–6, Rev. 21:14

- ^ Engelder, T.E.W., Popular Symbolics. St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1934. p. 95, Part XXIV. "The Lord's Supper", paragraph 131.

- ^ "The Solid Declaration of the Formula of Concord, Article 8, The Holy Supper". Bookofconcord.com. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ Graebner, Augustus Lawrence (1910). Outlines Of Doctrinal Theology. Saint Louis, MO: Concordia Publishing House. p. 162.

- ^ Graebner, Augustus Lawrence (1910). Outlines Of Doctrinal Theology. Saint Louis, MO: Concordia Publishing House. p. 163.

- ^ Luther's Small Catechism, Part IV, The Sacrament of the Altar, "What is the benefit of such eating and drinking? That is shown us in these words: Given, and shed for you, for the remission of sins; namely, that in the Sacrament forgiveness of sins, life, and salvation are given us through these words. For where there is forgiveness of sins, there is also life and salvation." Graebner, Augustus Lawrence (1910). Outlines Of Doctrinal Theology. Saint Louis, MO: Concordia Publishing House. p. 163.

- ^ Article 1, of the Articles Declaratory of the Constitution of the Church of Scotland 1921 states 'The Church of Scotland adheres to the Scottish Reformation'.

- ^ The Magisterial Reformation.

- ^ The World Christian Encyclopedia by David B. Barrt, George T. Kurian, and Todd M. Johnson (2001 edition)

- ^ Jay Diamond, Larry. Plattner, Marc F. and Costopoulos, Philip J. World Religions and Democracy. 2005, page 119.( also in PDF file, p49), saying "Not only do Protestants presently constitute 13 percent of the world's population—about 800 million people—but since 1900 Protestantism has spread rapidly in Africa, Asia, and Latin America."

- ^ "between 1,250 and 1,750 million adherents, depending on the criteria employed": McGrath, Alister E. Christianity: An Introduction. 2006, page xv1.

- ^ "2.1 thousand million Christians": Hinnells, John R. The Routledge Companion to the Study of Religion. 2005, page 441.

- ^ Pewforum: Christianity (2010)

- ^ Responses to Some Questions Regarding Certain Aspects of the Doctrine on the Church, June 29, 2007, Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.

- ^ Stuard-will, Kelly; Emissary (2007). Karitas Publishing (ed.). A Faraway Ancient Country. United States: Gardners Books. p. 216. ISBN 978-0-615-15801-3.

- ^ Bishop Hilarion of Vienna and Austria: The Vatican Document Brings Nothing New

- ^ The Protestant Reformers formed a new and radically different theological opinion on ecclesiology, that the visible Church is "catholic" (lower-case "c") rather than "Catholic" (upper-case "C"). Accordingly, there is not an indefinite number of parochial, congregational or national churches, constituting, as it were, so many ecclesiastical individualities, but one great spiritual republic of which these various organizations form a part, although they each have very different opinions. This was markedly far-removed from the traditional and historic Roman Catholic understanding that the Roman Catholic Church was the one true Church of Christ. Yet in the Protestant understanding, the "visible church" is not a genus, so to speak, with so many species under it. It is thus you may think of the State, but the visible church is a totum integrale, it is an empire, with an ethereal emperor, rather than a visible one. The churches of the various nationalities constitute the provinces of this empire; and though they are so far independent of each other, yet they are so one, that membership in one is membership in all, and separation from one is separation from all.... This conception of the church, of which, in at least some aspects, we have practically so much lost sight, had a firm hold of the Scottish theologians of the seventeenth century. James Walker in The Theology of Theologians of Scotland. (Edinburgh: Rpt. Knox Press, 1982) Lecture iv. pp.95-6.

- ^ The Canadian Reformed Magazine, 18 (September 20–27, October 4–11, 18, November 1, 8, 1969) http://spindleworks.com/library/faber/008_theca.htm

- ^ Keith Randell. Henry VIII and the Reformation in England, Hodder & Stoughton (1998) p. 88.

- ^ a b c William P. Haugaard. "The History of Anglicanism I", The Study of Anglicanism, Stephen Sykes and John Booty (eds) SPCK 1988, p.7; pp.7-8; pp.8-9 (respectively)

- ^ "Church Association Tract 049" (PDF). Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (1974), art. "Anglicanism", New International Dictionary of the Christian Church, Paternoster Press, Exeter (1974), art. "England, Church of".

- ^ a b "Adventist and Sabbatarian (Hebraic) Churches" section (p. 256–276) in Frank S. Mead, Samuel S. Hill and Craig D. Atwood, Handbook of Denominations in the United States, 12th edn. Nashville: Abingdon Press

- ^ Karl Heussi, Kompendium der Kirchengeschichte, 11. Auflage (1956), Tübingen (Germany), pp. 317-319, 325-326

- ^ Karl Heussi, Kompendium der Kirchengeschichte, p. 319

- ^ Clifton E. Olmstead (1960), History of Religion in the United States, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J., pp. 69-80, 88-89, 114-117, 186-188

- ^ M. Schmidt, Kongregationalismus, in Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart, 3. Auflage, Band III (1959), Tübingen (Germany), col. 1770

- ^ Gerhard Lenski (1963), The Religious Factor: A Sociological Study of Religion's Impact on Politics, Economics, and Family Life, Revised Edition, A Doubleday Anchor Book, Garden City, N.Y., pp.348-351

- ^ Cf. Robert Middlekauff (2005), The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789, Revised and Expanded Edition, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-516247-9, p. 52

- ^ Jan Weerda, Soziallehre des Calvinismus, in Evangelisches Soziallexikon, 3. Auflage (1958), Stuttgart (Germany), col. 934

- ^ Eduard Heimann, Kapitalismus, in Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart, 3. Auflage, Band III (1959), Tübingen (Germany), col. 1136-1141

- ^ Hans Fritz Schwenkhagen, Technik, in Evangelisches Soziallexikon, 3. Auflage, col. 1029-1033

- ^ Georg Süßmann, Naturwissenschaft und Christentum, in Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart, 3. Auflage, Band IV, col. 1377-1382

- ^ C. Graf von Klinckowstroem, Technik. Geschichtlich, in Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart, 3. Auflage, Band VI, col. 664-667

- ^ Kim, Sung Ho (Fall 2008). "Max Weber". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, CSLI, Stanford University. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- ^ a b Sztompka, 2003

- ^ Gregory, 1998

- ^ Becker, 1992

- ^ Heinrich Bornkamm, Toleranz. In der Geschichte des Christentums in Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart, 3. Auflage, Band VI (1962), col. 937

- ^ Original German title: Dass eine christliche Versammlung oder Gemeine Recht und Macht habe, alle Lehre zu beurteilen und Lehrer zu berufen, ein- und abzusetzen: Grund und Ursach aus der Schrift

- ^ Clifton E. Olmstead, History of Religion in the United States, pp. 4-10

- ^ Karl Heussi, Kompendium der Kirchengeschichte, 11. Auflage, p. 325

- ^ Quoted in Jan Weerda, Calvin, in Evangelisches Soziallexikon, 3. Auflage (1958), Stuttgart (Germany), col. 210

- ^ Clifton E. Olmstead, History of Religion in the United States, p. 10

- ^ Karl Heussi, Kompendium der Kirchengeschichte, S. 396-397

- ^ Cf. M. Schmidt, England. Kirchengeschichte, in Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart, 3. Auflage, Band II (1959), Tübingen (Germany), col. 476-478

- ^ Nathaniel Philbrick (2006), Mayflower: A Story of Courage, Community, and War, Penguin Group, New York, N.Y., ISBN 0-670-03760-5

- ^ Clifton E. Olmstead, History of Religion in the United States, pp. 65-76

- ^ Christopher Fennell (1998), Plymouth Colony Legal Structure, <http://www.histarch.uiuc.edu/plymouth/ccflaw.html>

- ^ Hanover Historical Texts Project <http://history.hanover.edu/texts/masslib.html>

- ^ M. Schmidt, Pilgerväter, in Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart, 3. Auflage, Band V (1961), col. 384

- ^ Christopher Fennell, Plymouth Colony Legal Structure

- ^ Allen Weinstein and David Rubel (2002), The Story of America: Freedom and Crisis from Settlement to Superpower, DK Publishing, Inc., New York, N.Y., ISBN 0-7894-8903-1, p. 61

- ^ Clifton E. Olmstead, History of Religion in the United States, p. 5

- ^ Heinrich Bornkamm, Toleranz. In der Geschichte des Christentums, in Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart, 3. Auflage, Band VI (1962), col. 937-938

- ^ H. Stahl, Baptisten, in Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart, 3. Auflage, Band I, col. 863

- ^ G. Müller-Schwefe, Milton, John, in Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart, 3. Auflage, Band IV, col. 955

- ^ Karl Heussi, Kompendium der Kirchengeschichte, p. 398

- ^ Clifton E. Olmstead, History of Religion in the United States, pp. 99-106, 111-117, 124

- ^ Edwin S. Gaustad (1999), Liberty of Conscience: Roger Williams in America, Judson Press, Valley Forge, p. 28

- ^ Hans Fantel (1974), William Penn: Apostle of Dissent, William Morrow & Co., New York, N.Y., pp. 150-153

- ^ Robert Middlekauff (2005), The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789, Revised and Expanded Edition, Oxford University Press, New York, N.Y., ISBN 978-0-19-516247-9, pp. 4-6, 49-52, 622-685

- ^ Clifton E. Olmstead, History of Religion in the United States, pp. 192-209

- ^ Cf. R. Voeltzel, Frankreich. Kirchengeschichte, in Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart, 3. Auflage, Band II (1958), col. 1039

- ^ Douglas K. Stevenson (1987), American Life and Institutions, Ernst Klett Verlag, Stuttgart (Germany), p. 34

- ^ G. Jasper, Vereinte Nationen, in Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart, 3. Auflage, Band VI, col. 1328-1329

- ^ Cf. G. Schwarzenberger, Völkerrecht, in Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart, 3. Auflage, Band VI, col. 1420-1422

- ^ Karl Heussi, Kompendium der Kirchengeschichte, 11. Auflage, pp. 396-399, 401-403, 417-419

- ^ Jeremy Waldron (2002), God, Locke, and Equality: Christian Foundations in Locke’s Political Thought, Cambridge University Press, New York, N.Y., ISBN 978-0521-89057-1, p. 13

- ^ Jeremy Waldron, God, Locke, and Equality, pp. 21-43, 120

- ^ W. Wertenbruch, Menschenrechte, in Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart, 3. Auflage, Band IV, col. 869

- ^ Allen Weinstein and David Rubel, The Story of America, pp. 189-309

- ^ Karl Heussi, Kompendium der Kirchengeschichte, 11. Auflage, pp. 403, 425

- ^ M. Elze,Grotius, Hugo, in Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart, 3. Auflage, Band II, col. 1885-1886

- ^ H. Hohlwein, Pufendorf, Samuel, in Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart, 3. Auflage, Band V, col. 721

- ^ R. Pfister, Schweiz. Seit der Reformation, in Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart, 3. Auflage, Band V (1961), col. 1614-1615

- ^ Clifton E. Olmstead, History of Religion in the United States, pp. 484-494

- ^ H. Wagner, Diakonie, in Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart, 3. Auflage, Band I, col. 164-167

- ^ J.R.H. Moorman, Anglikanische Kirche, in Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart, 3. Auflage, Band I, col. 380-381

- ^ Clifton E.Olmstead, History of Religion in the United States, pp. 461-465

- ^ Allen Weinstein and David Rubel, The Story of America, pp. 274-275

- ^ M. Schmidt, Kongregationalismus, in Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart, 3. Auflage, Band III, col. 1770

- ^ K. Kupisch, Bismarck, Otto von, in Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart, 3. Auflage, Band I, col. 1312-1315

- ^ P. Quante, Sozialversicherung, in Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart, Band VI, col. 205-206

- ^ "Orthodox Church: text - IntraText CT". Intratext.com. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ WELS Topical Q&A: Justification, stating: "A document which is aimed at settling differences needs to address those differences unambiguously. The Joint Declaration does not do this. At best, it sends confusing mixed signals and should be repudiated by all Lutherans."

- ^ "News Archives". UMC.org. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ "CNS STORY: Methodists adopt Catholic-Lutheran declaration on justification". Catholicnews.com. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

Further reading

- Cook, Martin L. (1991). The Open Circle: Confessional Method in Theology. Minneapolis, Minn.: Fortress Press. xiv, 130 p. N.B.: Discusses the place of Confessions of Faith in Protestant theology, especially in Lutheranism. ISBN 0-8006-2482-3

- Dillenberger, John, and Claude Welch (1988). Protestant Christianity, Interpreted through Its Development. Second ed. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co. ISBN 0-02-329601-1

- McGrath, Alister E. (2007). Christianity's Dangerous Idea. New York: HarperOne.

- Nash, Arnold S., ed. (1951). Protestant Thought in the Twentieth Century: Whence & Whither? New York: Macmillan Co.

- Noll, Mark A. (2011). Protestantism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

External links

This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (August 2010) |

- "Protestantism" from the 1917 Catholic Encyclopedia

- World Council of Churches World body for mainline protestant churches