Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight D. Eisenhower | |

|---|---|

| |

| 34th President of the United States | |

| In office January 20, 1953 – January 20, 1961 | |

| Vice President | Richard Nixon |

| Preceded by | Harry S. Truman |

| Succeeded by | John F. Kennedy |

| 1st Supreme Allied Commander Europe | |

| In office April 2, 1951 – May 30, 1952 | |

| President | Harry S. Truman |

| Deputy | Arthur Tedder |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Matthew Ridgway |

| 16th Chief of Staff of the Army | |

| In office November 19, 1945 – February 6, 1948 | |

| President | Harry S. Truman |

| Deputy | J. Lawton Collins |

| Preceded by | George Marshall |

| Succeeded by | Omar Bradley |

| Military Governor of the U.S. Occupation Zone in Germany | |

| In office May 8, 1945 – November 10, 1945 | |

| President | Harry S. Truman |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | George S. Patton (acting) |

| 13th President of Columbia University | |

| In office June 7, 1948 – January 19, 1953 | |

| Preceded by | Frank D. Fackenthal (acting) |

| Succeeded by | Grayson L. Kirk |

| Personal details | |

| Born | David Dwight Eisenhower October 14, 1890 Denison, Texas, U.S. |

| Died | March 28, 1969 (aged 78) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library, Museum and Boyhood Home |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | |

| Children | |

| Parent |

|

| Education | United States Military Academy (BS) |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1915–1953 1961–1969[1] |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | World War I World War II |

| Awards | Army Distinguished Service Medal (5) Navy Distinguished Service Medal Legion of Merit Full list |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

World War II

34th President of the United States

First Term

Second Term

Presidential campaigns Post-Presidency

|

||

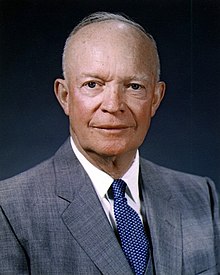

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (/ˈaɪzənhaʊ.ər/ EYE-zən-how-ər; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American army general and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. He also served as a five-star general in the United States Army during World War II, and was responsible for planning and supervising Allied operations on the Western Front during 1943-45 when Germany was defeated.

Eisenhower was born David Dwight Eisenhower and was raised in a tight-knit German-American family in Abilene, Kansas. He graduated from West Point in 1915 and trained tank crews on the home front during World War I. Following the war, he served in various assignments, reaching the rank of brigadier general shortly before the United States entered World War II. He became a top Army was planner. He led the victorious Allied invasion of North Africa. He also presided over the initial phases of the Italian campaign. Eisenhower was then selected to lead the invasion of Western Europe, and he remained in command of the American zone of defeated Germany.

After the war, Eisenhower served as Chief of Staff of the United States Army, as president of Columbia University, and as the first Supreme Commander of NATO. In 1952, Eisenhower entered the presidential race as a Republican, largely to block the isolationist foreign policies of Senator Robert A. Taft. He defeated Taft at the 1952 Republican National Convention and went on to win the 1952 presidential election in a landslide over Democrat Adlai Stevenson II. Taking office in the midst of the Cold War, he continued President Harry S. Truman's containment policy against the Soviet Union and brought the Korean War to an end. He also gave strong financial support to the new state of South Vietnam and put a new emphasis on the Middle East. His attempts to reach a nuclear test ban treaty with the Soviet Union were derailed by the 1960 U-2 incident.

On the domestic front, President Eisenhower was a moderate conservative who usually let Taft take the lead. He continued Social Security, emphasized a balanced budget, and presided over a period of economic growth until a recession hit in 1958. He operated quietly behind the scenes to shape all major policies of his administration. His signature program was the Interstate Highway System, a massive infrastructure project that connected the nation through tens of thousands of miles of divided highways and was sold as a defense program that would facilitate the evacuation of cities in wartime. He was reelected in an even bigger landslide in 1956. After the Soviet Union launched Sputnik I space satellite in 1957, Eisenhower pushed the National Defense Education Act, which increased educational funding, and authorized the establishment of NASA, which led to the Space Race. He did not embrace the Supreme Court's landmark desegregation ruling in the 1954 case of Brown v. Board of Education. He did intervene with federal troops to uphold a federal court otder to integrate a high school in Little Rock Arkansas. He let Vice President Richard Nixon handle the role of campaigning in support of the Republican Party state by state. He retired in 1961 and died at the of 78 in 1969. Historical evaluations of his presidency generally place him among the upper half of American presidents.

Early life and education, 1890–1915

Dwight David Eisenhower was born on October 14, 1890, in Denison, Texas, the third of seven sons born to David Eisenhower and his wife, Ida Elizabeth (Stover) Eisenhower.[2] His mother originally named him David Dwight, but later reversed the two names after his birth to avoid the confusion of having two Davids in the family.[3] His father, David Jacob Eisenhower, was a college-educated engineer originally from Pennsylvania. He had moved to Kansas in 1875 along with his parents, and had briefly owned a dry-goods store in Kansas before moving to Denison in 1888.[4] His mother, Ida, was born in Virginia and, unusually for a 19th century woman in Kansas, had attended college for a year at Lane University, where she had met David.[5] The Eisenhower family returned to Kansas in 1891, settling in the town of Abilene.[6] By 1898, the parents made a decent living and provided a suitable home for their large family.[7] As children, Eisenhower and all of his brothers were called some form of "Ike", such as "Big Ike" (Edgar) and "Little Ike" (Dwight); the nickname was intended as an abbreviation of their last name.[8]

As a child, Eisenhower developed a keen and enduring interest in exploring the outdoors.[9] His parents set aside specific times at breakfast and at dinner for daily family Bible reading, and chores were regularly assigned and rotated among all the children.[10] At the time of Eisenhower's birth, both of his parents were members of the River Brethren sect of the Mennonites, but they later joined the Bible Students (later known as Jehovah's Witnesses).[11] Eisenhower himself never joined the International Bible Students, but his family home served as the local meeting hall from 1896 to 1915.[12] Eisenhower's mother was morally opposed to war, but it was her collection of history books that first sparked Eisenhower's early and lasting interest in military history.[13] Eisenhower's later decision to attend West Point saddened his mother, but she did not overrule his decision.[14]

Eisenhower attended Abilene High School and graduated with the class of 1909.[15] As a freshman, Eisenhower developed a leg infection which his doctor diagnosed as life-threatening. The doctor insisted that the leg be amputated, but Dwight refused to allow it and ultimately recovered, though he had to repeat his freshman year.[16] After high school, he and his older brother, Edgar, made a pact to take alternate years at college while the other worked to earn tuition.[17] Edgar took the first turn at school, while Eisenhower worked at a creamery alongside his father.[18] Encouraged by his friend, "Swede" Hazlett, Eisenhower contacted U.S. Senator Joseph L. Bristow for an appointment to either the United States Naval Academy (his first choice) or the United States Military Academy (known metonymically as West Point), neither of which required tuition. Unusually for the era, Bristow made his selections for the service academies on the basis of a competitive examination, and Eisenhower did well enough on the test to receive an appointment to West Point.[19]

Eisenhower reported to West Point in June 1911.[20] During his time there, Eisenhower relished the emphasis on traditions and on sports, but was less enthusiastic about the hazing. He was also a regular violator of the more detailed regulations, and finished school with a less than stellar discipline rating. Academically, his performance was average, though he thoroughly enjoyed the typical emphasis of engineering, science, and mathematics.[21] Historian William I. Hitchcock describes football as Eisenhower's "one true passion" during his academy years, and he spent much of his time focused on athletics.[22] He was a starter as a running back and linebacker in 1912, and in one game he tackled noted football player Jim Thorpe of the Carlisle Indians.[23] A knee injury forced him to stop playing football and nearly prevented him from getting a commission in the army, but Colonel Henry Alden Shaw, the chief medical officer at West Point, ultimately cleared him for service.[24] Eisenhower graduated in the middle of the class of 1915, which became known as "the class the stars fell on" because 59 members (including Eisenhower and Omar Bradley) eventually became general officers.[22]

Military career, 1915–1945

Early years

After graduating from West Point in June 1915, Eisenhower was commissioned as a second lieutenant in September.[22] He requested to serve in the Philippines, but was instead assigned to the 19th Infantry Regiment at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas.[25] While stationed there, Eisenhower served as the football coach for St. Louis College, now St. Mary's University.[26] He also met and married Mamie Doud, the daughter of a meat-processing facility owner from Denver, Colorado.[27]

World War I had broken out in Europe in 1914, and the U.S. joined the war on the side of the Entente Powers in April 1917.[28] Like many other 19th Infantry personnel, Eisenhower was promoted and assigned to the newly-created 57th Infantry Regiment, where he served as the regimental supply officer.[29] He was later assigned command of the 301st Heavy Tank Battalion, overseeing training at Camp Meade, Maryland and Camp Colt, Pennsylvania.[30] In October 1918, Eisenhower received orders to deploy to Europe, but the war ended with the signing of the Armistice of 11 November 1918.[31] Though Eisenhower and his tank crews never saw combat, he displayed excellent organizational skills, as well as an ability to accurately assess junior officers' strengths and make optimal placements of personnel.[32] During World War II, rivals who had combat service in the first great war often sought to denigrate Eisenhower for his previous lack of combat experience.[33]

Between wars

Service in the 1920s

With the end of World War I, the United States dramatically cut back military spending, and the number of active duty personnel in the army dropped from 2.4 million in late 1918 to about 150,000 in 1922.[34] Eisenhower reverted to his regular rank of captain, but was almost immediately promoted to the rank of major. He would hold that rank for the next sixteen years.[35] In 1919, he served on the Transcontinental Motor Convoy, an army convoy that traveled from Washington, D.C. to San Francisco at a pace of 5 mph.[36] The convoy, which was designed both as a training exercise and as a way to publicize the need for better roads, spurred many states to increase funding for road-building.[37] He then returned to his duties at Camp Meade, commanding a battalion of tanks until 1922. His new expertise in tank warfare was strengthened by a close collaboration with George S. Patton, Sereno E. Brett, and other senior tank leaders. Their leading-edge ideas of speed-oriented offensive tank warfare were strongly discouraged by superiors, who considered the new approach too radical and preferred to continue using tanks in a strictly supportive role for the infantry.[38]

Between 1922 and 1939, Eisenhower served under a succession of talented generals – Fox Conner, John J. Pershing, and Douglas MacArthur. He first became executive officer to General Conner in the Panama Canal Zone, where, joined by Mamie, he served until 1924. Under Conner's tutelage, he studied military history and theory (including Carl von Clausewitz's On War). He later cited Conner's enormous influence on his military thinking, saying in 1962 that "Fox Conner was the ablest man I ever knew."[39] Conner would play a critical role in Eisenhower's career, often helping him gain choice assignments.[40] In 1925–26, Eisenhower attended the Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, where he graduated first in a class of 245 officers.[41] With Conner's help, Eisenhower was assigned to work under General Pershing on the American Battle Monuments Commission, which established monuments and cemeteries in Western Europe to honor fallen American soldiers.[42] In 1929, Eisenhower became the executive officer to General George Van Horn Moseley, who served on the staff of Assistant Secretary of War Frederick Huff Payne.[43] In this role, Eisenhower helped make national defense policy and studied wartime industrial mobilization.[44]

Service in the 1930s

After Douglas MacArthur became Chief of Staff of the United States Army, Eisenhower began working as MacArthur's unofficial military secretary[45] In 1932, he participated in MacArthur's violent clearing of the Bonus March encampment in Washington, D.C.[46] Eisenhower did not vote in the 1932 presidential election, but he privately supported President Franklin D. Roosevelt's early New Deal measures as a way of rescuing the country from the Great Depression.[47] In 1935 he accompanied MacArthur to the Philippines, where he was charged with developing the nascent Philippine Army.[48] He had strong philosophical disagreements with MacArthur regarding the role of the Philippine Army and the leadership qualities that an American army officer should exhibit and develop in his subordinates. The resulting antipathy between Eisenhower and MacArthur lasted the rest of their lives,[49] though Eisenhower later emphasized that too much had been made of the disagreements with MacArthur. Historians have concluded that this assignment provided valuable preparation for handling the challenging personalities of Winston Churchill, George S. Patton, George Marshall, and Bernard Montgomery during World War II.[50]

World War II broke out in Europe following Nazi Germany's invasion of Poland in September 1939. Under the direction of Chief of Staff George Marshall and Secretary of War Henry Stimson, the army expanded from about 200,000 men in late 1939 to 1.4 million men in mid-1941.[51] By the end of 1939, Eisenhower had impressed his fellow officers with his administrative skills, but he had never held an active command above a battalion and few considered him a potential commander of major operations. Eisenhower returned to the United States in December 1939 and was assigned as commanding officer of the 15th Infantry Regiment.[52] In June 1941, after briefly serving under Major General Kenyon Joyce, he was appointed chief of staff to General Walter Krueger, commander of the Third Army.[53] In mid-1941, the U.S. Army conducted the Louisiana Maneuvers, the largest military exercise that the army had ever conducted on U.S. soil.[54] The Third Army's success in the Louisiana Maneuvers impressed Eisenhower's superiors, and he was promoted to brigadier general on October 3, 1941.[52]

World War II

War Plans Division

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the United States entered World War II. The war pitted the Allied Powers of the United States, Britain, the Soviet Union, and other countries against the Axis Powers of Nazi Germany, the Empire of Japan, the Kingdom of Italy, and other states. Almost immediately after the attack on Pearl Harbor, General Marshall assigned Eisenhower to the War Plans Division in Washington, where Eisenhower helped the country's grand strategy in the war. Eisenhower and Marshall both shared the conclusion of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill that the United States should pursue a Europe first against the Axis Powers.[55] Biographer Jean Edward Smith writes that Marshall and Eisenhower developed a "father-son relationship"; it was widely assumed that Marshall would eventually lead major operations in Europe, and he initially sought to prepare Eisenhower to serve as his chief of staff during those operations.[56]

Operations in North Africa and Italy

In June 1942, Eisenhower was transferred to London and assigned command of all U.S. soldiers in the European Theater of Operations.[57] His command involved important military and administrative duties, but one of his chief challenges was coordinating a multinational military and political alliance among combatants with contrasting military traditions and doctrines, as well a level of distrust.[58] He also frequently met with the press and emerged as a public symbol of the Allied war effort.[59] Overcoming objections from Eisenhower and Marshall, Prime Minister Churchill convinced Roosevelt that the Allies should launch an invasion against Axis Power's "soft underbelly" in the Mediterranean rather than in Western Europe. Eisenhower was thus assigned to lead Operation Torch, the November 1942 Allied invasion of French North Africa.[58] Eisenhower became the commander of all Allied forces operating in the Mediterranean Theater of Operations, making him the direct superior of both American and British officers.[60]

At the time, both Algeria and French Morocco were controlled by Vichy France, an officially neutral power that had been established in southern France following the French surrender to Germany in 1940.[61] Vichy France had a complex relationship with the Allied Powers; it collaborated with Nazi Germany, but was recognized by the United States as the official government of France.[62] Hoping to encourage French forces in Africa to support the Allied campaign, Eisenhower and diplomat Robert Daniel Murphy attempted to recruit General Henri Giraud, who lived in the Vichy-controlled part of France but was not part of its high command.[63] French forces resisted the Allied landing until diplomat Robert Daniel Murphy and General Mark W. Clark negotiated an agreement with Admiral François Darlan, the commander-in-chief of Vichy armed forces, that granted the Allied Powers military access to French North Africa and confirmed French sovereignty over the region.[64] Darlan was later assassinated,[65] and Free France leader Charles de Gaulle emerged as the leader of the French war effort by the end of 1943.[66]

Following the success of Operation Torch, the Allies launched an invasion of Tunisia.[67] Bolstered by superior tanks and air power, as well as favorable weather, the German forces established a strong defense of the city of Tunis, leading to a stalemate in the campaign.[68] In February 1943, German forces launched a successful attack on General Lloyd Fredendall's II Corps at the Battle of Kasserine Pass. The II Corps collapsed and Eisenhower relieved Fredendall of command, but Allied forces prevented a German breakthrough.[69] After the battle, the Allies continually built up their forces[70] and forced the surrender of 250,000 Axis soldiers in May 1943, bringing an end to the North African Campaign.[71]

As the length of the Tunisia Campaign had made a cross-channel invasion of France impracticable in 1943, Roosevelt and Churchill agreed that the next Allied target would be Italy.[72] The Allies invaded Sicily in July and took control of the island by the end of August. During the campaign in Sicily, King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy arrested Prime Minister Benito Mussolini and replaced him with Pietro Badoglio, who secretly negotiated a surrender with the Allies.[73] Germany responded by shifting several divisions to Italy, occupying Rome, and establishing a puppet state, the Italian Social Republic.[74] The Allied invasion of mainland Italy began in September 1943. In the aftermath of Italy's surrender, the Allies faced unexpectedly strong resistance from German forces under Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, who nearly defeated Operation Avalanche, the Allied landing near the port of Salerno.[75] With 24 German divisions defending the country's rugged terrain, Italy quickly became a secondary theater in the war.[76]

Operation Overlord

In December 1943, President Roosevelt decided that Eisenhower – not Marshall – would lead Operation Overlord, the Allied invasion of Western Europe.[77] Eisenhower, as well as the officers and troops under him, had learned valuable lessons in their previous operations, preparing them for the most difficult campaign against the Germans—a beach landing assault in northern France.[78] Drawing on the experience of Operation Avalanche, Eisenhower bellieved that it was "vital that the entire sum of our assault power, including the two Strategic Air Forces, be available for use during the critical stages of the attack."[79] The operation would ultimately require 6,000 ships to carry 150,000 soldiers across the English Channel, where, with the support of Allied air power, Allied soldiers would assault entrenched German defenders in Normandy.[80] Eisenhower helped secure de Gaulle's participation in the landing, partly by avoiding a diplomatic incident stemming from the arrest of several former Vichy officials who had assisted the Allies.[81] His sense of responsibility for the invasion was underscored by his draft of a statement to be issued if the invasion failed. It has been called one of the great speeches of history:

Our landings in the Cherbourg-Havre area have failed to gain a satisfactory foothold and I have withdrawn the troops. My decision to attack at this time and place was based on the best information available. The troops, the air and the Navy did all that bravery and devotion to duty could do. If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt, it is mine alone.[82]

High winds delayed Operation Overlord by a day, but Eisenhower chose to take advantage of a break in the weather and ordered the Normandy landings to take place on June 6, 1944.[83] The timing and location of the landings surprised the Germans, who failed to reinforce their coastal defenders in a timely manner.[84] Allied forces quickly secured four of the five landing zones, though the Germans put up a strong defense of Omaha Beach.[85] The Allies consolidated control of the landing zones and launched the next phase of the operation, capturing the port of Cherbourg by the end of June. By the end of July, over 1.5 million Allied soldiers and over 300,000 vehicles had landed in Normandy.[86] The Allies repulsed a German counter-attack in the Battle of the Falaise Pocket, bringing a close to the fighting in Normandy before the end of August.[87] Meanwhile, the Allied landing in Southern France succeeded, as the Allies captured Marseille and began moving north.[88] On the Eastern Front, the Soviet Union launched a major offensive known as Operation Bagration, preventing Germany from sending reinforcements west.[89]

Liberation of France and victory in Europe

Once the coastal assault had succeeded, Eisenhower insisted on retaining personal control over the land battle strategy, and was immersed in the command and supply of multiple assaults.[90] Encouraged by de Gaulle and the German commander Dietrich von Choltitz, Eisenhower ordered the liberation of Paris in late August.[91] With German resistance collapsing sooner than had been expected, the Allies rapidly liberated most of France, Belgium, and Luxembourg.[92] In recognition of his senior position in the Allied command, on December 20, 1944, he was promoted to General of the Army, equivalent to the rank of field marshal in most European armies.[93][a] That same month, the Germans launched a surprise counter offensive, the Battle of the Bulge, which the Allies turned back in early 1945 after Eisenhower repositioned his armies and after improved weather allowed the Air Force to engage.[95] Though many Allied soldiers lost their lives in the fighting, Germany suffered a decisive defeat in the battle.[96]

After the Battle of the Bulge and the success of a massive Soviet offensive in early 1945, Eisenhower sent Air Chief Marshal Tedder to the Soviet Union to help establish a joint strategy for the invasion of Germany.[97] Eisenhower declined to engage the Soviets in a race for the German capital of Berlin, and instead prioritized linking up with Soviet forces as soon as possible.[98][b] Allied soldiers reached the Rhine in early March, capturing a key bridge near the town of Remagen before the Germans could destroy it.[100] German resistance quickly collapsed, and Eisenhower accepted the surrender of Germany on May 7, 1945.[101]

Postwar career, 1945–1953

Postwar military service, 1945–1948

After the war, Eisenhower became the military governor of the American occupation zone, located primarily in Southern Germany and headquartered at the IG Farben Building in Frankfurt am Main.[102] Though Eisenhower aggressively purged ex-Nazis, his actions largely reflected the American attitude that the broad German populace were victims of the Nazis.[102] He also developed a strong working relationship with Soviet Marshal Georgy Zhukov, the commander of the Soviet occupation zone in Germany, and visited Moscow at Zhukov's request.[103] Eisenhower learned of the secret development of the atomic bomb weeks before the Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki; he expressed opposition to the bombings on the grounds that the use of atomic weaponry would increase post-war tensions.[104]

Following the Surrender of Japan and the end of the World War II, Marshall retired in November 1945. On Marshall's recommendation, President Truman selected Eisenhower as the new chief of staff of the army.[105] His main task in that role was the demobilization of millions of soldiers, but he also advised the president on military policy[106] and made numerous public appearances in order to maintain public support for the army.[107] Concerned that rapid demobilization would deprive the army of necessary manpower in its duties and fully return the military to its small, pre-war state, Eisenhower joined Truman in calling for some form of universal military service. Congress rejected the idea of universal service, though it did extend the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940.[108] Eisenhower was convinced in 1946 that the Soviet Union did not want war and that friendly relations could be maintained; he strongly supported the new United Nations and favored its involvement in the control of atomic bombs. By mid-1947, as East–West tensions over economic recovery in Germany and the Greek Civil War escalated, Eisenhower had come to agree with the containment policy of stopping Soviet expansion.[106]

President of Columbia University

In 1948, Eisenhower became the president of Columbia University, an Ivy League university in New York City.[109] Biographer William I. Hitchcock writes that Eisenhower was "temperamentally unsuited" to the position, as "[h]e wanted to move fast; the university moved slowly. He wanted decision-making power in his hands; the trustees often derailed his plans. ... Before long it was clear that Eisenhower did not fit in."[110] Nonetheless, Eisenhower enjoyed some success at Columbia, notably convincing New York Mayor William O'Dwyer to close the portion of 116th Street that had previously bisected Columbia's campus.[111]

During his time at Columbia, Eisenhower developed a network of political and business contacts, chief among them William E. Robinson, who convinced Eisenhower to publish his memoirs, Crusade in Europe.[112] Eisenhower earned about $475,000 in after-tax profits from Crusade in Europe, making him financially independent.[113] He also advised the military on the unification of the services pursuant to the National Security Act of 1947, and gave numerous speeches.[114] His various activities contributed to a perception held by many Columbia University faculty and staff that Eisenhower was an absentee president who was using the university for his own interests.[115]

NATO Supreme Commander

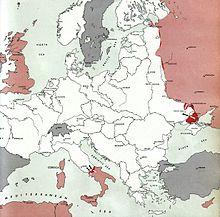

In June 1950, Communist-backed North Korea invaded U.S.-aligned South Korea, marking the start of the Korean War. The U.S. intervened on behalf of South Korea and inflicted several defeats on North Korean forces, but the war settled into a stalemate after the People's Republic of China committed forces to aid North Korea. Distressed by U.S. unpreparedness in the war, President Truman shook up his national security team and proposed dramatic increases in military spending.[116] As part of this response, Truman asked Eisenhower to make the public case for the importance of U.S. commitments to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), a military alliance of Western states that had been formed in 1949.[117] Though Eisenhower was unable to sway Robert A. Taft, a powerful Republican senator from Ohio, most other members of Congress agreed to support the alliance. In April 1951, after taking a leave of absence from Columbia, Eisenhower was confirmed by the Senate as the first Supreme Commander of NATO. In this role, he was charged with forging a cohesive military force capable of standing up to a potential Soviet invasion.[118]

Election of 1952

Postwar political involvement

Prior to the 1948 presidential election, many prominent citizens and politicians from both parties urged Eisenhower to run for president.[119] Marshall and MacArthur were also the subject of presidential speculation, but New York Times journalist Arthur Krock noted that Eisenhower was "the one military name that crops up in both Republican and Democratic groups".[120] In 1945, President Truman told Eisenhower that, if Eisenhower desired, Truman would help the general win the 1948 presidential election.[119] As others asked him about his political future, Eisenhower expressed a reluctance to go into politics, saying that he could not imagine wanting to be considered for any political job "from dogcatcher to Grand High Supreme King of the Universe". In January 1948, after learning of plans in New Hampshire to elect delegates supporting him for the forthcoming 1948 Republican National Convention, Eisenhower stated through the army that he was "not available for and could not accept nomination to high political office".[119] Privately, he was disappointed by Truman's victory over Republican Thomas Dewey in the 1948 election.[121] Though he had generally supported Truman's foreign policy, Eisenhower held conservative views on most domestic issues and never seriously considered running for office as a Democrat.[122]

Republican nomination

With polling often showing Truman's approval rating below 30 percent after 1950, many observers believed that Republicans were likely to win the 1952 presidential election, which would represent the party's first victory since the onset of the Great Depression.[123] Along with Senator Taft, Eisenhower emerged as one of the two major candidates in the 1952 Republican presidential primaries.[124] Taft led the conservative wing of the party, which was centered in the Midwest, rejected many of the New Deal social welfare programs created in the 1930s, and generally held a non-interventionist foreign policy stance. Taft had been a candidate for the Republican nomination in 1940 and 1948, but had been defeated both times by moderate Republicans. These moderates were generally willing to accept most aspects of the social welfare state created by the New Deal and tended to be interventionists in the Cold War.[125] Beginning in 1951, they assembled a draft Eisenhower organization.[126] Eisenhower's key supporters, including Dewey, General Lucius D. Clay, and attorney Herbert Brownell Jr., asked Senator Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. to serve as the public head of the draft Eisenhower movement.[127]

Though reluctant to become involved in partisan politics[128] Eisenhower was troubled by Taft's non-interventionist views, especially his opposition to NATO.[129] He indicated in late 1951 that he would not oppose efforts to nominate him for president, but nor would he openly seek nomination.[130] While Eisenhower served in Europe, Taft threw himself into the campaign, pledging an "all-out attack" on government spending and the New Deal. Nonetheless, with the support of Governor Sherman Adams and other notable state party leaders, Eisenhower won the crucial New Hampshire primary.[131] Now fully committed to running for president, Eisenhower resigned from his NATO command and returned to the United States. The Taft forces put up a strong fight in the remaining primaries, and, by the time of the July 1952 Republican National Convention, it was still unclear whether Taft or Eisenhower would win the presidential nomination.[132] After a closely-contested series of votes on the seating of delegates, Eisenhower won the presidential nomination on the first ballot of the convention. Afterward, Senator Richard Nixon of California was nominated by acclamation as his vice-presidential running mate.[133] Nixon, whose name came to the forefront early and frequently in pre-convention conversations among Eisenhower's campaign managers, was selected because of his relative youth and solid anti-communist credentials.[134] Eisenhower would later consider dropping Nixon from the ticket after Nixon was accused of improperly using a fund established by his backers.[135] Nixon remained on the ticket after delivering the well-received "Checkers speech", but the incident permanently strained relations between Nixon and Eisenhower.[136]

General election

With Truman retiring from office, the Democrats nominated Illinois governor Adlai Stevenson II for president.[137] Although his style thrilled intellectuals and academics, some political experts wondered if Stevenson were speaking "over the heads" of most of his listeners, and they dubbed him an "egghead." His biggest liability however, was the unpopularity of Truman.[138] Meanwhile, Republican strategy during the campaign focused on Eisenhower's unrivaled popularity.[139] Ike traveled to 45 of the 48 states; his heroic image and plain talk excited the large crowds who heard him speak from the campaign train's caboose. In his speeches, Eisenhower never mentioned Stevenson by name, instead relentlessly attacking the alleged failures of the Truman administration: "Korea, Communism, and corruption."[140] In domestic policy, Eisenhower criticized the growing influence of the federal government in the economy, while in foreign affairs, he supported a strong American role in stemming the expansion of Communism. Eisenhower adopted much of the rhetoric and positions of the contemporary GOP, and many of his public statements were designed to win over conservative supporters of Taft.[141]

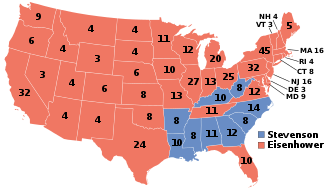

Ultimately, the burden of the ongoing Korean War and Truman's unpopularity, as well as Eisenhower's high public standing, were too much for Stevenson to overcome.[142] Eisenhower won a landslide victory, taking 55.2 percent of the popular vote and 442 electoral votes, while Stevenson received 44.5 percent of the popular vote and 89 electoral votes. Eisenhower won every state outside of the South, as well as Virginia, Florida, and Texas, each of which voted Republican for just the second time since the end of Reconstruction.[143] Compared to Dewey's 1948 candidacy, he improved with Catholics, farmers, blue-collar workers, and voters from the suburbs.[144] In the concurrent congressional elections, Republicans won control of the House of Representatives and the Senate, giving the party unified control of Congress and the presidency for the first time since the 1930 elections.[145] Eisenhower became the last president born in the 19th century,[146] the third commanding general of the army to serve as president, after George Washington and Ulysses S. Grant, and the last to have not held political office prior to being president until Donald Trump entered office in January 2017.[147]

Presidency, 1953–1961

| The Eisenhower cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | Dwight D. Eisenhower | 1953–1961 |

| Vice President | Richard Nixon | 1953–1961 |

| Secretary of State | John Foster Dulles | 1953–1959 |

| Christian Herter | 1959–1961 | |

| Secretary of the Treasury | George M. Humphrey | 1953–1957 |

| Robert B. Anderson | 1957–1961 | |

| Secretary of Defense | Charles Erwin Wilson | 1953–1957 |

| Neil H. McElroy | 1957–1959 | |

| Thomas S. Gates Jr. | 1959–1961 | |

| Attorney General | Herbert Brownell Jr. | 1953–1957 |

| William P. Rogers | 1957–1961 | |

| Postmaster General | Arthur Summerfield | 1953–1961 |

| Secretary of the Interior | Douglas McKay | 1953–1956 |

| Fred A. Seaton | 1956–1961 | |

| Secretary of Agriculture | Ezra Taft Benson | 1953–1961 |

| Secretary of Commerce | Sinclair Weeks | 1953–1958 |

| Frederick H. Mueller | 1959–1961 | |

| Secretary of Labor | Martin Patrick Durkin | 1953 |

| James P. Mitchell | 1953–1961 | |

| Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare | Oveta Culp Hobby | 1953–1955 |

| Marion B. Folsom | 1955–1958 | |

| Arthur Sherwood Flemming | 1958–1961 | |

| Ambassador to the United Nations | Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. | 1953–1960 |

| James Jeremiah Wadsworth | 1960–1961 | |

Eisenhower delegated the selection of his cabinet to two close associates, Lucius Clay and Herbert Brownell, the latter of whom became attorney general. The office of Secretary of State went to John Foster Dulles, a long-time Republican spokesman on foreign policy who had helped design the United Nations Charter and the Treaty of San Francisco. For his other Cabinet appointments, Eisenhower sought out leaders of big business such as Charles Erwin Wilson, the CEO of General Motors, and George M. Humphrey, the CEO of several steel and coal companies.[148] Martin Patrick Durkin, a Democrat and president of the plumbers and steamfitters union, was selected as secretary of labor.[148] As a result, it became a standing joke that Eisenhower's inaugural Cabinet was composed of "nine millionaires and a plumber."[149]

Since the 19th century, many if not all presidents were assisted by a central figure or "gatekeeper", sometimes described as the president's private secretary, but Eisenhower formalized this role as the White House Chief of Staff, appointing Sherman Adams to the position.[150][page needed] Eisenhower appointed Robert Cutler as National Security Advisor, and Cutler helped turn the National Security Council into an important decision-making body.[151] Eisenhower gave Vice President Nixon multiple diplomatic, domestic, and political assignments so that he "evolved into one of Ike's most valuable subordinates." The office of vice president was thereby fundamentally upgraded from a minor ceremonial post to a major role in the presidential team.[152] Nonetheless, Eisenhower did not trust Nixon to ably lead the country if he acceded to the presidency, and he attempted to remove Nixon from the Republican ticket in 1956 by offering him the position of Secretary of Defense. Nixon declined the offer, but Eisenhower decided not to actively oppose Nixon's re-nomination.[153]

Eisenhower frequently met with the press corps, but his performance in these meetings was widely regarded as awkward. These press conferences contributed greatly to the criticism that Eisenhower was ill-informed or merely a figurehead in his government. At times, he was able to use his reputation for unintelligible press conferences to his advantage, as it allowed him to obfuscate his position on difficult subjects.[154] On January 19, 1955 Eisenhower became the first president to conduct a televised news conference.[155] On August 26, 1959, he became the first president to fly in Air Force One, which replaced the Columbine as the presidential aircraft.[156]

Foreign affairs

Cold War policies

The Cold War dominated international politics in the 1950s. As both the United States and the Soviet Union possessed nuclear weapons, any conflict presented the risk of escalation into nuclear warfare.[157] Eisenhower continued the basic Truman administration policy of containment of Soviet expansion and the strengthening of the economies of Western Europe.[158] In April 1953, Eisenhower delivered his "Chance for Peace speech," in which he called for an armistice in Korea, free elections to re-unify Germany, the "full independence" of Eastern European nations, and United Nations control of atomic energy. Though well received in the West, the Soviet leadership viewed Eisenhower's speech as little more than propaganda. In 1954, Soviet leader Georgy Malenkov was succeeded by a more confrontational leader, Nikita Khrushchev.[159] In response to the integration of West Germany into NATO in 1955, Eastern bloc leaders established a rival alliance known as the Warsaw Pact.[160]

Eisenhower pursued a national security policy known as the New Look, which reflected his concern for balancing the Cold War military commitments of the United States with the nation's financial resources. The policy emphasized reliance on strategic nuclear weapons, rather than conventional military power, to deter both conventional and nuclear military threats.[161] Eisenhower sought to create a nuclear triad consisting of land-launched nuclear missiles, nuclear-missile-armed submarines, and strategic aircraft with nuclear weapons. Throughout the 1950s, both the United States and the Soviet Union developed intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBMs) and intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBMs) capable of delivering nuclear warheads. Eisenhower also presided over the development of the UGM-27 Polaris missile, which was capable of being launched from submarines, and continued funding for long-range bombers like the Boeing B-52 Stratofortress.[162] The New Look policy allowed Eisenhower to reduce the size of the army and navy, but some military leaders, including General Matthew Ridgway and General Maxwell Taylor, criticized the New Look policy for forcing the United States into an "all or nothing" policy regarding wars.[163]

Eisenhower, while accepting the doctrine of containment, also sought to counter the Soviet Union through more active means as detailed in the State-Defense report NSC 68.[164] An early use of covert action was against the elected Prime Minister of Iran, Mohammed Mosaddeq, resulting in the 1953 Iranian coup d'état. Eisenhower was concerned about the possibility of a Communist takeover of the country, but another important factor was Iran's earlier decision to nationalize the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company.[165] The CIA also instigated the 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état by the local military that overthrew president Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán, whom U.S. officials viewed as too friendly toward the Soviet Union.[166] The Eisenhower administration placed a high priority on undermining Soviet influence on Eastern Europe, and escalated a propaganda war during Eisenhower's first term. After Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev dispatched 60,000 soldiers to crush the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, the United States shifted its policy in Eastern Europe from encouraging revolt to seeking cultural and economic ties as a means of undermining Communist regimes.[167] In January 1959, the Cuban Revolution ousted U.S.-aligned President Fulgencio Batista in favor of Fidel Castro.[168] As Castro drew closer to the Soviet Union, the U.S. broke diplomatic relations, launched a near-total embargo, and began preparations for an invasion of Cuba by Cuban exiles. The invasion took place shortly after Eisenhower left office, becoming known as the Bay of Pigs Invasion; it ultimately failed to dislodge Castro.[169]

East Asia and Southeast Asia

Truman had begun peace talks in the ongoing Korean War in mid-1951, but the issue of over 40,000 North Korean and Chinese prisoner who refused repatration was a major sticking point in the negotiations.[170] Upon taking office, Eisenhower demanded a solution, warning China that he would use nuclear weapons if the war continued.[171] China came to terms, and an armistice was signed on July 27, 1953 as the Korean Armistice Agreement. Historian Edward C. Keefer says that in accepting the American demands that POWs could refuse to return to their home country, "China and North Korea still swallowed the bitter pill, probably forced down in part by the atomic ultimatum."[172] The armistice led to decades of uneasy peace between North Korea and South Korea. The United States and South Korea signed a defensive treaty in October 1953, and the U.S. would continue to station thousands of soldiers in South Korea long after the end of the Korean War.[173]

Seeking to bolster France and prevent the fall of Vietnam to Communism, the Truman and Eisenhower administrations played a major role in financing French military operations in the First Indochina War.[174] In 1954, the French requested the United States to intervene in the Battle of Dien Bien Phu, which would prove to be the climactic battle of the war. As France refused to commit to granting independence to Vietnam, Congress refused to approve of an intervention in Vietnam, and the French were defeated at Dien Bien Phu. At the contemporaneous Geneva Conference, Dulles convinced Chinese and Soviet leaders to pressure Viet Minh leaders to accept the temporary partition of Vietnam; the country was divided into a Communist northern half (under the leadership of Ho Chi Minh) and a non-Communist southern half (under the leadership of Ngo Dinh Diem).[175]

Despite some doubts about the strength of Diem's government, the Eisenhower administration directed aid to South Vietnam in hopes of creating a bulwark against further Communist expansion.[176] With Eisenhower's approval, Diem refused to hold elections to re-unify Vietnam; those elections had been scheduled for 1956 as part of the agreement at the Geneva Conference.[177] Eisenhower's commitment in South Vietnam was part of a broader program to contain China and the Soviet Union in East Asia, and the United States joined seven other countries in establishing the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO), a defensive alliance dedicated to preventing the spread of Communism in Southeast Asia. In 1954, the United States and the Republic of China signed the Sino-American Mutual Defense Treaty, which committed the United States to the defense of the Republic of China.[178] Tensions in China led to the First Taiwan Strait Crisis and the Second Taiwan Strait Crisis during Eisenhower's presidency, but both crises ended peacefully.[179]

Middle East

The Middle East became increasingly important to U.S. foreign policy during the 1950s and, as it did in several other regions, the Eisenhower administration sought to establish stable, friendly, anti-Communist regimes in the Arab World.[180] In 1952, a revolution led by Gamal Abdel Nasser had overthrown the pro-British Egyptian government. Eisenhower sought to bring Nasser into the American sphere of influence through economic aid, but Nasser's Arab nationalism and opposition to Israel served as a source of friction between the United States and Egypt. In July 1956, just a week after the collapse of aid negotiations between the United States and Egypt regarding the Aswan Dam, Nasser nationalized the British-run Suez Canal, sparking the Suez Crisis.[181] With the support of Britain and France, Israel attacked Egypt in October 1956, quickly seizing control of the Sinai Peninsula. The Eisenhower administration proposed a cease fire and used economic pressure to force France and Britain to withdraw.[182] Though opposed to the nationalization of the canal, Eisenhower feared that the military intervention would disrupt global trade and alienate Middle Eastern countries from the West.[183] In early 1958, Eisenhower used the threat of economic sanctions to coerce Israel into withdrawing from the Sinai Peninsula, and the Suez Canal resumed operations under the control of Egypt.[184]

In response to the power vacuum in the Middle East following the Suez Crisis, the Eisenhower administration developed a new policy designed to stabilize the region against Soviet threats or internal turmoil. Under the policy, known as the Eisenhower Doctrine, any Middle Eastern country could request American economic assistance or aid from U.S. military forces if it was being threatened by armed aggression. Though Eisenhower found it difficult to convince leading Arab states or Israel to endorse the doctrine, he applied the new doctrine by dispensing economic aid to shore up the Kingdom of Jordan and sending U.S. troops into Lebanon to prevent a radical revolution from sweeping over that country.[185] The troops sent to Lebanon never saw any fighting, but the deployment marked the only time during Eisenhower's presidency when U.S. troops were sent abroad into a potential combat situation.[186]

U-2 Crisis

U.S. and Soviet leaders met at the 1955 Geneva Summit, the first such summit since the 1945 Potsdam Conference. No progress was made on major issues; the two sides had major differences on German policy, and the Soviets dismissed Eisenhower's "Open Skies" proposal.[187] Despite the lack of agreement on substantive issues, the conference marked the start of a minor thaw in Cold War relations.[188] Kruschev toured the United States in 1959, and he and Eisenhower conducted high-level talks regarding nuclear disarmament and the status of Berlin.[189] Towards the end of his second term, Eisenhower was determined to reach a nuclear test ban treaty as part of an overall move towards détente with the Soviet Union. Khrushchev had also become increasingly interested in reaching an accord, partly due to the growing Sino-Soviet split.[190] Hopes for reaching a nuclear agreement at a May 1960 summit in Paris were derailed by the downing of an American U-2 spy plane over the Soviet Union.[189] The Eisenhower administration, initially thinking the pilot had died in the crash, authorized the release of a cover story claiming that the plane was a "weather research aircraft" which had unintentionally strayed into Soviet airspace after the pilot had radioed "difficulties with his oxygen equipment" while flying over Turkey.[191] When the Soviets produced the pilot, Captain Francis Gary Powers, the Americans were caught misleading the public, and the incident resulted in international embarrassment for the United States.[192][193] Later, Eisenhower stated the Paris summit was ruined because of that "stupid U-2 business".[194]

Domestic affairs

Modern Republicanism

Eisenhower's approach to politics was described by contemporaries as "modern Republicanism," which occupied a middle ground between the liberalism of the New Deal and the conservatism of the Old Guard of the Republican Party.[195] Although Eisenhower favored some reduction of the federal government's functions and had strongly opposed President Truman's Fair Deal, he supported the continuation of Social Security and other New Deal programs that he saw as beneficial for the common good.[196] In 1954, he signed a law that increased Social Security benefits and added about ten million self-employed individuals into the program.[197] Eisenhower's largely nonpartisan stance enabled him to work smoothly with the Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn and Senate Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson, who came into power following Democratic victories in the 1954 elections.[198] In his own party, Eisenhower maintained strong support with moderates, but he frequently clashed with conservative members of Congress, especially over foreign policy.[199]

When Republicans gained control of both houses of the Congress at the beginning of Eisenhower's term, conservatives pressed the president to support tax cuts. Eisenhower however, gave a higher priority to balancing the budget, refusing to cut taxes "until we have in sight a program of expenditure that shows that the factors of income and outgo will be balanced." Eisenhower kept the national debt low and inflation near zero.[200] Meanwhile, throughout his presidency, the top marginal tax rate was 91 percent—among the highest in American history.[201] Federal spending as a percentage of GDP fell from 20.4 to 18.4 percent—there has not been a decline of any size in federal spending as a percentage of GDP during any administration since.[202] The 1950s were a period of economic expansion in the United States, and the gross national product jumped from $355.3 billion in 1950 to $487.7 billion in 1960. Unemployment rates were also generally low, except for in 1958.[203]

Interstate highway system

One of Eisenhower's enduring achievements was the Interstate Highway System, which Congress authorized through the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956.[204] In 1954, Eisenhower appointed General Lucius D. Clay to head a committee charged with proposing an interstate highway system plan.[205] The president's support for the project was influenced by his experiences as a young army officer crossing the country as part of the 1919 Army Convoy.[206] Summing up motivations for the construction of such a system, Clay stated,

It was evident we needed better highways. We needed them for safety, to accommodate more automobiles. We needed them for defense purposes, if that should ever be necessary. And we needed them for the economy. Not just as a public works measure, but for future growth.[207][208]

Clay's committee proposed a 10-year, $100 billion program, which would build 40,000 miles of divided highways linking all American cities with a population of greater than 50,000. Eisenhower initially preferred a system consisting of toll roads, but Clay convinced Eisenhower that toll roads were not feasible outside of the highly populated coastal regions. In February 1955, Eisenhower forwarded Clay's proposal to Congress. The bill quickly won approval in the Senate, but House Democrats objected to the use of public bonds as the means to finance construction. Eisenhower and the House Democrats agreed to instead finance the system through the Highway Trust Fund, which itself would be funded by a gasoline tax.[209] In long-term perspective the interstate highway system was a remarkable success; although there have been objections to the negative impact of clearing neighborhoods in cities in order to build highways, the system sharply reduced the cost of shipping and travel.[210] Another major infrastructure project, the Saint Lawrence Seaway, was also completed during Eisenhower's presidency.[211]

McCarthyism

With the onset of the Cold War, the House of Representatives established the House Un-American Activities Committee to investigate alleged disloyal activities, and a new Senate committee made Senator Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin a national leader and namesake of the anti-Communist movement.[212] Though McCarthy remained a popular figure when Eisenhower took office, his constant attacks on the State Department and the army, and his reckless disregard for due process, offended many Americans.[213] Privately, Eisenhower held McCarthy and his tactics in contempt, but his reluctance to publicly oppose McCarthy drew criticism even from many of Eisenhower's own advisers.[214] In early 1954, after McCarthy escalated his investigation into the army, Eisenhower moved against McCarthy by releasing a report indicating that McCarthy had pressured the army to grant special privileges to an associate, G. David Schine.[215] Eisenhower also refused to allow members of the executive branch to testify in the Army–McCarthy hearings, contributing to the collapse of those hearings.[216] Following those hearings, Senator Ralph Flanders introduced a successful measure to censure McCarthy; Senate Democrats voted unanimously for the censure, while half of the Senate Republicans voted for it. The censure ended McCarthy's status as a major player in national politics, and he died of liver failure in 1957.[217] Though he disagreed with McCarthy on tactics, Eisenhower considered Communist infiltration to be a serious threat, and he authorized department heads to dismiss employees if there was cause to believe those employees might be disloyal to the United States. Under the direction of Dulles, the State Department purged over 500 employees.[218]

Civil rights

In the 1950s, African Americans in the South faced mass disenfranchisement and racially segregated schools, bathrooms, and drinking fountains. Even outside of the South, African Americans faced employment discrimination, housing discrimination, and high rates of poverty and unemployment.[219] Truman had begun the process of desegregating the Armed Forces in 1948, but actual implementation had been slow.[220] Upon taking office, Eisenhower moved quickly to end resistance to desegregation of the military by using government control of spending to compel compliance from military officials. "Wherever federal funds are expended," he told reporters in March, "I do not see how any American can justify a discrimination in the expenditure of those funds."[221] Eisenhower also sought to end discrimination in federal hiring and in Washington, D.C. facilities.[222] Despite these actions, Eisenhower resisted becoming involved in the expansion of voting rights, the desegregation of public education, or the eradication of employment discrimination.[223] On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court handed down its landmark ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, declaring state laws establishing separate public schools for black and white students to be unconstitutional. Privately, Eisenhower disapproved of the Supreme Court's holding, stating that he believed it "set back progress in the South at least fifteen years."[224]

Segregationists, including the Ku Klux Klan, responded with a campaign of "massive resistance," violently opposing those who sought to desegregate public education in the South. In 1956, most Southern members of Congress signed the Southern Manifesto, which called for the overturning of Brown.[225] As Southern leaders continued to resist desegregation, Eisenhower introduced a civil rights bill designed to increase the protection of African American voting rights; approximately 80% of African Americans were disenfranchised in the mid-1950s.[226] The bill faced strong opposition in the Senate from Southerners, and it bill passed only after many of its original provisions were removed. Though some black leaders urged him to reject the watered-down bill as inadequate, Eisenhower signed the Civil Rights Act of 1957 into law. It was the first federal law designed to protect African Americans since the end of Reconstruction.[227]

Eisenhower hoped that the passage of the Civil Rights Act would, at least temporarily, remove the issue of civil rights from the forefront of national politics, but events in Arkansas would force him into action.[228] The school board of Little Rock, Arkansas created a federal court-approved plan for desegregation, with the program to begin implementation at Little Rock Central High School. Governor Orval Faubus mobilized the National Guard to prevent nine black students, known as the "Little Rock Nine," from entering Central High. Though Eisenhower had not fully embraced the cause of civil rights, he was determined to uphold federal authority and to prevent an incident that could embarrass the United States on the international stage. Eisenhower sent the army into Little Rock, and the army ensured that the Little Rock Nine could attend Central High. Faubus derided Eisenhower's actions, claiming that Little Rock had become "occupied territory," and in 1958 he temporarily shut down Little Rock high schools.[229] Towards the end of his second term, Eisenhower proposed another civil rights bill designed to help protect voting rights, but Congress once again passed a bill with weaker provisions than Eisenhower had requested. Eisenhower signed the bill into law as the Civil Rights Act of 1960.[230]

Space program and education

Americans were astonished when, on October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1, which became the first man-made object to enter into Earth's orbit.[231] Three months later, a nationally televised test of the American Vanguard TV3 missile failed in an embarrassing fashion; the missile was facetiously referred to as "Flopnik" and "Stay-putnik."[232] To many, the success of the Soviet satellite program suggested that the Soviet Union had made a substantial leap forward in technology that posed a serious threat to U.S. national security. While Eisenhower initially downplayed the gravity of the Soviet launch, public fear and anxiety about the perceived technological gap grew.[233] The president was, as British prime minister Harold Macmillan observed during a June 1958 visit to the U.S., "under severe attack for the first time" in his presidency.[234]

The launch spurred a series of federal government initiatives ranging from defense to education. Renewed emphasis was placed on the Explorers program to launch an American satellite into orbit; this was accomplished on January 31, 1958 with the successful launch of Explorer 1.[235] In February 1958, Eisenhower authorized formation of the Advanced Research Projects Agency, later renamed the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), within the Department of Defense to develop emerging technologies for the U.S. military.[236] In July 1958, he signed the National Aeronautics and Space Act, which established NASA as a civilian space agency.[237] NASA took over the space technology research started by DARPA, as well as the air force's manned satellite program, Man In Space Soonest, which was renamed as Project Mercury.[238] In September 1958, the president signed into law the National Defense Education Act, a four-year program that poured billions of dollars into the U.S. education system. Between 1953 and 1960, total educational funding grew almost six-fold.[239]

States admitted to the Union

Eisenhower had called for the admission of Alaska and Hawaii as states during his 1952 campaign, but various issues delayed their statehood. Hawaii faced opposition from Southern members of Congress who objected to the island chain's large non-white population, while concerns about military bases in Alaska convinced Eisenhower to oppose statehood for the territory early in his tenure.[240] In 1958, Eisenhower reached an agreement with Congress on a bill that provided for the admission of Alaska and set aside large portions of Alaska for military bases. Eisenhower signed the Alaska Statehood Act into law in July 1958, and Alaska became the 49th state on January 3, 1959. Two months later, Eisenhower signed the Hawaii Admission Act, and Hawaii became the 50th state in August 1959.[241]

Judicial appointments

Eisenhower appointed five justices of the Supreme Court of the United States.[243] In 1953, Eisenhower nominated Governor Earl Warren to succeed Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson. Many conservative Republicans opposed Warren's nomination, but they were unable to block the appointment, and Warren's nomination was approved by the Senate in January 1954. Warren presided over a court that generated numerous liberal rulings on various topics, beginning in 1954 with the desegregation case of Brown v. Board of Education.[244] Robert H. Jackson's death in late 1954 generated another vacancy on the Supreme Court, and Eisenhower successfully nominated federal appellate judge John Marshall Harlan II to succeed Jackson. Harlan joined the conservative bloc on the bench, often supporting the position of Associate Justice Felix Frankfurter.[245]

After Sherman Minton resigned in 1956, Eisenhower nominated state supreme court justice William J. Brennan to the Supreme Court. Eisenhower hoped that the appointment of Brennan, a liberal-leaning Catholic, would boost his own re-election campaign. Opposition from Senator Joseph McCarthy and others delayed Brennan's confirmation, so Eisenhower placed Brennan on the court via a recess appointment in 1956; the Senate confirmed Brennan's nomination in early 1957. Brennan joined Warren as a leader of the court's liberal bloc. Stanley Reed's retirement in 1957 created another vacancy, and Eisenhower nominated federal appellate judge Charles Evans Whittaker, who would serve on the Supreme Court for just five years before resigning. The fifth and final Supreme Court vacancy of Eisenhower's tenure arose in 1958 due to the retirement of Harold Burton. Eisenhower successfully nominated federal appellate judge Potter Stewart to succeed Burton, and Stewart became a centrist on the court.[245] Eisenhower also appointed 45 judges to the United States Courts of Appeals, and 129 judges to the United States district courts.

Health issues

Eisenhower left office as the oldest president in U.S. history,[c] and he suffered from some health issues during his presidency.[247] Eisenhower had begun chain smoking cigarettes at West Point, often three or four packs a day.[248] He was the first president to release information about his health and medical records while in office, but people around him deliberately misled the public about his health. On September 24, 1955, while vacationing in Colorado, he had a serious heart attack.[249] Dr. Howard Snyder, his personal physician, misdiagnosed the symptoms as indigestion, and failed to call in the help that was urgently needed. Snyder later falsified his own records to cover his blunder and to protect Eisenhower's need to portray he was healthy enough to do his job.[250][251][252] The heart attack required six weeks' hospitalization, during which time Nixon, Dulles, and Sherman Adams assumed administrative duties and provided communication with the President.[253]

As a consequence of his heart attack, Eisenhower developed a left ventricular aneurysm, which was in turn the cause of a mild stroke on November 25, 1957. This incident occurred during a cabinet meeting when Eisenhower suddenly found himself unable to speak or move his right hand. The president also suffered from Crohn's disease,[254] chronic inflammatory condition of the intestine,[255] which necessitated surgery for a bowel obstruction on June 9, 1956.[256] To treat the intestinal block, surgeons bypassed about ten inches of his small intestine.[257] His scheduled meeting with Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru was postponed so he could recover at his farm.[258] Eisenhower's health issues forced him to give up smoking and make some changes to his dietary habits, though he still indulged in alcohol.[259]

Elections of 1956 and 1958

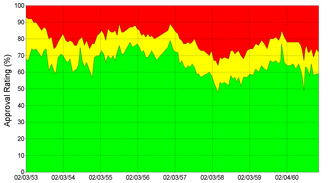

In July 1955, TIME Magazine lauded the president for bringing "prosperity to the nation," noting that, "In the 29 months since Dwight Eisenhower moved into the White House, a remarkable change has come over the nation. Blood pressure and temperature have gone down; nerve endings have healed over. The new tone could be described in a word: confidence."[260] This sentiment was reflected by Eisenhower's Gallup poll approval rating, which ranged between 68 and 79 percent during his first term.[261] Eisenhower's September 1955 heart attack engendered speculation about whether he would be able to seek a second term, but his doctor pronounced him fully recovered in February 1956, and soon thereafter Eisenhower announced his decision to run for reelection.[262] He was unanimously re-nominated at the 1956 Republican National Convention.[263] Meanwhile, the 1956 Democratic National Convention nominated Adlai Stevenson for president, setting up a re-match of the 1952 election.[264]

Eisenhower campaigned on his record of economic prosperity and his Cold War foreign policy.[265] The Suez Crisis and the Hungarian Revolution became the focus of Eisenhower's attention in the final weeks of the campaign, and his actions in the former crises boosted his popularity.[266] On election day, Eisenhower won by an even greater margin than he had four years earlier, taking 457 electoral votes to Stevenson's 73.[267] In interviews with pollsters, his voters were less likely to bring up his leadership record. Instead what stood out this time, "was the response to personal qualities— to his sincerity, his integrity and sense of duty, his virtue as a family man, his religious devotion, and his sheer likeableness."[268] Eisenhower's victory did not provide a strong coattail effect for other Republican candidates, and Democrats retained control of Congress.[269]

The economy began to decline in mid-1957 and reached its nadir in early 1958. The Recession of 1958 was the worst economic downturn of Eisenhower's tenure, as the unemployment rate reached a high of 7.5%. The poor economy, Sputnik, the federal intervention in Little Rock, and a contentious budget battle all sapped Eisenhower's popularity, with Gallup polling showing that his approval rating dropped from 79 percent in February 1957 to 52 percent in March 1958.[270] A controversy broke out in mid-1958 after a House subcommittee discovered that White House Chief of Staff Sherman Adams had accepted an expensive gift from Bernard Goldfine, textile manufacturer under investigation by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). Adams denied the accusation that he had interfered with the FTC investigation on Goldfine's behalf, but Eisenhower forced him to resign in September 1958.[271] Republicans suffered major defeats in the 1958 elections, as Democrats picked up over forty seats in the House and over ten seats in the Senate.[272]

1960 election and transition

The 22nd Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ratified in 1951, established a two-term limit for the presidency. As the amendment had not applied to President Truman, Eisenhower became the first president constitutionally limited to two terms. Eisenhower nonetheless closely watched the 1960 presidential election, which he viewed as a referendum on his presidency.[273] Eisenhower offered Nixon lukewarm support in the 1960 Republican primaries; when asked by reporters to list one of Nixon's policy ideas he had adopted, Eisenhower joked, "If you give me a week, I might think of one. I don't remember."[274] Despite the lack of strong support from Eisenhower, Nixon's successful cultivation of party elites ensured that he faced only a weak challenge from Governor Nelson Rockefeller for the Republican nomination.[275]

The 1960 campaign was dominated by the Cold War and the economy. John F. Kennedy triumphed at the 1960 Democratic National Convention, defeating Lyndon B. Johnson, Hubert Humphrey, and other candidates to become the party's presidential nominee. To shore up support in the South and West, Kennedy chose Johnson as his running mate. In the general election, Kennedy attacked the alleged "missile gap" and endorsed federal aid for education, an increased minimum wage, and the establishment of a federal health insurance program for the elderly.[276] Nixon, meanwhile, wanted to win on his own, and did not take up Eisenhower's offers for help.[277] To Eisenhower's great disappointment, Kennedy defeated Nixon in an extremely close election.[278] Kennedy took 49.7 percent of the popular vote and won the electoral vote by a margin of 303-to-219.[279]

During the campaign, Eisenhower had privately lambasted Kennedy's inexperience and connections to political machines, but after the election he worked with Kennedy to ensure a smooth transition. He personally met twice with Kennedy, emphasizing especially the danger posed by Cuba.[280] On January 17, 1961, Eisenhower gave his final televised Address to the Nation from the Oval Office.[281] In his farewell address, Eisenhower raised the issue of the Cold War and role of the U.S. armed forces. He described the Cold War: "We face a hostile ideology global in scope, atheistic in character, ruthless in purpose and insidious in method ..." and warned about what he saw as unjustified government spending proposals and continued with a warning that "we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military–industrial complex."[281] Eisenhower's address reflected his fear that military spending and the desire to ensure total security would be pursued to the detriment of other goals, including a sound economy, efficient social programs, and individual liberties.[282]

Post-presidency, 1961–1969

Retirement

After leaving office, Eisenhower moved to the place where he and Mamie had spent much of their post-war time, a working farm adjacent to the Civil War battlefield at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.[283][284] They also maintained a winter home at the Eldorado Country Club in Southern California's Coachella Valley.[285] In his retirement, Eisenhower did not completely retreat from political life. He occasionally advised President Kennedy and President Lyndon B. Johnson, especially regarding the Vietnam War.[286] He also addressed the 1964 Republican National Convention, in San Francisco, and appeared with party nominee Barry Goldwater in a campaign commercial from his Gettysburg retreat.[287] That endorsement came somewhat reluctantly because Goldwater had in the late 1950s criticized Eisenhower's administration as "a dime-store New Deal".[288] On January 20, 1969, the day Nixon was inaugurated as President, Eisenhower issued a statement praising his former vice president and calling it a "day for rejoicing".[289]

During his retirement, Eisenhower suffered several ultimately crippling heart attacks.[290] A severe heart attack in August 1965 largely ended his participation in public affairs.[291] In August 1966 he began to show symptoms of cholecystitis, for which he underwent surgery on December 12, 1966, when his gallbladder was removed, containing 16 gallstones.[290] After Eisenhower's death in 1969 (see below), an autopsy unexpectedly revealed an adrenal pheochromocytoma,[292] a benign adrenaline-secreting tumor that may have made the President more vulnerable to heart disease. Eisenhower suffered seven heart attacks from 1955 until his death.[290]

Death and funeral

On the morning of March 28, 1969, Eisenhower died in Washington, D.C., of congestive heart failure at Walter Reed Army Medical Center; he was 78 years old. The following day, his body was moved to the Washington National Cathedral's Bethlehem Chapel, where he lay in repose for 28 hours.[293] He was then transported to the United States Capitol, where he lay in state in the Capitol Rotunda March 30–31.[294] A state funeral service was conducted at the Washington National Cathedral on March 31. The president and First Lady, Richard and Pat Nixon, attended, as did former president Lyndon Johnson. Also among the 2,000 invited guests were several Heads of state, including Charles de Gaulle of France and the Shah of Iran. The service included the singing of Faure's The Palms, and the playing of Onward, Christian Soldiers.[295]

That evening, Eisenhower's body was placed onto a special funeral train for its journey from the nation's capital through seven states to his hometown of Abilene, Kansas. First incorporated into President Abraham Lincoln's funeral in 1865, a funeral train would not be part of a U.S. state funeral again until 2018.[296] Eisenhower is buried inside the Place of Meditation, the chapel on the grounds of the Eisenhower Presidential Center in Abeline. As requested, he was buried in a Government Issue casket, and wearing his World War II uniform, decorated with: Army Distinguished Service Medal with three oak leaf clusters, Navy Distinguished Service Medal, and the Legion of Merit. Buried alongside Eisenhower are his son Doud, who died at age 3 in 1921, and wife Mamie, who died in 1979.[293]

President Richard Nixon eulogized Eisenhower in 1969, saying:

Some men are considered great because they lead great armies or they lead powerful nations. For eight years now, Dwight Eisenhower has neither commanded an army nor led a nation; and yet he remained through his final days the world's most admired and respected man, truly the first citizen of the world.[297]

Personal life

Eisenhower met his wife, Mamie (née Doud) in October 1915 while stationed at Fort Sam Houston. They became engaged in February 1916 and were married on July 1, 1916. Eisenhower enjoyed an excellent relationship with his in-laws, and Mamie's gregariousness and devotion to her husband were major assets to his military career.[298] The Eisenhowers frequently moved during his time in the military and did not own a home until 1950, when they purchased a farmhouse in Gettysburg.[299] Dwight and Mamie Eisenhower had two children, both sons. Doud Dwight "Icky" Eisenhower, died of scarlet fever in 1921 at the age of three. Eisenhower later wrote that Doud's death was "the greatest disappointment and disaster in my life, the one I have never been able to forget completely."[300] Their second son, John Eisenhower, was born in 1922.[42] John served in the United States Army, retired as a brigadier general, became an author and served as U.S. Ambassador to Belgium from 1969 to 1971.[301] John and his wife, Barbara had four children: David, Barbara Ann, Susan Elaine and Mary Jean. David, after whom Camp David is named,[302] married Richard Nixon's daughter Julie in 1968.[286]

Eisenhower was a golf enthusiast later in life, and he joined the Augusta National Golf Club in 1948. He had a small, basic golf facility installed at Camp David, and became close friends with the Augusta National Chairman Clifford Roberts, inviting Roberts to stay at the White House on several occasions.[303][page needed] With his excellent memory and ability to focus, Eisenhower was skilled at card games, especially poker and contract bridge, which he frequently played.[304] Oil painting was another of Eisenhower's hobbies.[305] Eisenhower painted about 260 oils, mostly landscapes, during the last 20 years of his life.[306] A conservative in both art and politics, in a 1962 speech he denounced modern art as "a piece of canvas that looks like a broken-down Tin Lizzie, loaded with paint, has been driven over it".[305] Angels in the Outfield was Eisenhower's favorite movie,[307] and his favorite reading material for relaxation were the Western novels of Zane Grey.[308]