Irish passport

| Irish Passport Pas Éireannach[a] | |

|---|---|

The front cover of a contemporary Irish biometric passport booklet (with chip | |

| Type | Passport |

| Issued by | Ireland |

| First issued | 3 April 1924 (first version) 1 January 1985 (first EU format) 1 October 2006[1] (first biometric passport) 3 October 2013[1] (current version) 2 October 2015[2] (passport card) |

| Purpose | Identification |

| Eligibility | Irish citizens |

| Expiration |

|

| Cost | Adult (18 or older)[4]

Child

|

An Irish passport (Irish: pas Éireannach) is the passport issued to citizens of Ireland. An Irish passport enables the bearer to travel internationally and serves as evidence of Irish nationality and citizenship of the European Union. It also facilitates the access to consular assistance from both Irish embassies and any embassy from other European Union member states while abroad.

Irish passports are issued by the Passport Office, a division of the Department of Foreign Affairs. All Irish passports have been biometric since 2006. In 2015, the Irish government introduced the Passport Card, which enables Irish citizens who already possess a passport to travel throughout the European Economic Area (EEA) and Switzerland. An Irish Passport Card is intended for travel and identification purposes and functions similarly to an EEA national identity card.

Both Irish passports and Irish passport cards allow Irish citizens to travel, live, and work without restriction in any country within the EEA, Switzerland and the Common Travel Area. Irish citizens have visa-free or visa on arrival access to 193 countries and territories; the international access available to Irish citizens ranks third in the world according to the 2024 Visa Restrictions Index.[6]

As of 2024[update], Irish citizens are the only nationality in the world with the automatic right to live and work in both the European Union and the United Kingdom.

History

[edit]The Irish Free State was created in 1922 as a dominion of the British Commonwealth, modelled explicitly on the Dominion of Canada. At the time, dominion status was a limited form of independence and while the Free State Constitution referred to "citizens of the Irish Free State", the rights and obligations of such citizens were expressed to apply only "within the limits of the jurisdiction of the Irish Free State".[7]

The Irish Free State first notified the UK Government that it proposed to issue its own passports in 1923.[8] The Irish government initially proposed that the description they would give citizens in their passports would be "Citizen of the Irish Free State".[9] According to a report from The Irish Times the first time that Irish passports were used was by the Irish delegation to the League of Nations in August 1923.[10] The British Government objected to this. It insisted that the appropriate description was "British subject", because, inter alia, the Irish Free State was part of the British Commonwealth. The Irish government considered the British viewpoint. The Governor-General subsequently informed the British government that the description that would generally be used (with some exceptions) would be "Citizen of the Irish Free State and of the British Commonwealth of Nations".[8] Without reaching agreement with the UK, the Irish government issued its first passports to the general public on 3 April 1924,[11] using this description.

The British Government was not satisfied with this compromise. It instructed its consular and passport officers everywhere that Irish Free State passports were not to be recognised if the holder was not described in the passport as a "British subject".[12] This led to considerable practical difficulty for Irish Free State citizens abroad, with many having to obtain British passports in addition to their Irish Free State passports. The British consular officers would also confiscate the Irish Free State passports, a practice the Irish authorities regarded as "very humiliating".[12]

The stalemate as regards Irish passports continued until January 1930 when the Irish authorities reluctantly accepted a compromise formula originally suggested by the Irish Minister for External Affairs, Desmond Fitzgerald, in 1926.[13] The Irish authorities issued a circular letter to British consular and passport authorities agreeing that Irish passports would be changed so that they were issued by the Minister for External Affairs in the name of the king using the king's full title; would describe the bearer as "one of His Majesty's subjects of the Irish Free State"; and if passports were issued to persons other than subjects of His Majesty, that fact would be stated.[13] This formula settled the thorny issue.

In 1939, two years after the adoption of the Constitution of 1937, which formally renamed the state "Ireland", the Irish government decided to make significant changes to the form of Irish passports. As a courtesy, the Irish authorities notified the British authorities. In a memorandum dated 1 March 1939 entitled "The Form of Eire Passports", the British Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs, Thomas W. H. Inskip, informed his government of developments which had recently taken place "regarding the form of passports issued by the Government of Eire".[14]

In the memorandum, the Secretary of State reported that "hitherto [the passports] (which have not, I understand, been amended since 1936) have borne two indications of relationship to the British Commonwealth of Nations". These, the memorandum noted, were the reference to the king including his full title in the "request" page; and a front page, where underneath the words "Irish Free State" (in Irish, English and French) appear the words "British Commonwealth of Nations". The proposals notified by the Irish authorities included replacing the reference to "Irish Free State" with "Ireland"; amending the "request" page to drop reference to the king; and dropping the reference to the "British Commonwealth of Nations". The Secretary of State proposed that he reply to the Irish authorities in terms that "His Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom greatly regrets the proposed elimination of the king's name from Éire passports; that in their view, the omission, when it comes to be known, is bound to create a bad impression in the UK and to widen the separation which Mr de Valera deplores between Éire and Northern Ireland".[14]

The Secretary of State noted in his memorandum that to "say more than this might raise questions [relating to whether or not Ireland was still in the Commonwealth] which it was the object of the statement of the 30th December 1937, to avoid". This was a reference to the communique published by Downing Street noting the adoption of the Irish Constitution, stating that in their view Ireland continued to be part of the Commonwealth and affirming the position of Northern Ireland as part of the United Kingdom.[14]

Ultimately, the Irish proceeded with their plans including that the term "Citizen of the Irish Free State and of the British Commonwealth of Nations" would be replaced with "Citizen of Ireland". This has remained the description up to present time, with current Irish passports describing the holder as a "citizen of Ireland" on the request page and giving the holder's nationality as "Éireannach/Irish" on the information page.

The evolution of the physical description of the passport utilised by Irish citizens from 3 April 1924 to 1 January 1985 (when the new European passports were introduced) was one of change. Prior to the first usage of an Irish passport in 1924, Irish citizens were issued with a 32-page British Passport, which had a navy blue hardcover with an embossed British coat of arms. Above the coat of arms the identifier "British Passport" was printed, while below the coat of arms the inscription "The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland" was printed. It also contained two cut-outs in the cover, which allowed the bearer's name and the passport number to be displayed. The first Irish passport, issued to the general public from 3 April 1924, contained a green hardcover with the Irish coat of arms, the harp, embossed in the centre. The passport was bilingual in Irish and English whereby, encircling the harp was the national inscription of Saorstát Éireann and "Irish Free State", while above the coat of arms the identifier "Pas" and "Passport" was printed. It also contained a cut-out for the bearer's name.

Following the enactment of the Irish constitution, the physical appearance of the Irish passport changed again. While it retained the green colour and the embossed harp at the centre, the number of languages on the cover changed to three, with French joining Irish and English. To the left of the harp, the national inscription "Éire", "Ireland", and "Irlande" was printed in a row, while to the right of the harp, the identifier "Pas", "Passport", and "Passeport" was printed. The 1970s saw a slight change to the document: while the national inscription was made bigger in the three languages, and moved to the top right corner, the identifier "passport" was also enlarged, and moved to the bottom left corner of the cover. On 23 June 1981, during the council meeting of the member states of the European Communities (now the European Union), a resolution was agreed to make all member state passports more uniform.[15][16][17] This change, which included changing the colour of all member states passports to burgundy was to see the first European passports from 1 January 1985.[15] However, only three member states (Denmark, Ireland, and Italy) had implemented this change on the specified date, with all other member states complying later.[16][17] Irish citizens in possession of the old green Irish passports could still make use of their passports until they expired.[16]

"Sale" of passports in 1988–1998

[edit]A 1988 scheme was designed to draw foreign investment into Ireland, described in a 1998 Seanad debate as the "Passports for investment scheme"[18] Each had to invest $1,000,000 and live in Ireland for varying periods. The scheme was scrapped in 1998.[19] Before long it was being described as the "sale" of passports in the media, but only 143 passports were passed on under the scheme. Notable applicants included some of the Getty family,[20] Sheikh Khalid bin Mahfouz and Khalid Sabih Masri. Masri had lent IR£1,100,000 to the pet food company of Taoiseach Albert Reynolds.[21]

Another was Norman Turner from Manchester, whose proposed investment was to build a casino in Dublin's Phoenix Park. Turner had entertained Bertie Ahern and had paid £10,000 in cash to his party, and received his passport later in 1994.[22] The matter was revealed during the Mahon Tribunal hearings in 2008; Mr Ahern commented that Mr Turner had an Irish mother, and that in 2007 some 7,000 other passport applications were assisted in some way by politicians.[23]

The 2006 Moriarty Tribunal report covered the grant of passports to a Mr Fustok and some of his friends. Mr Fustok had previously bought a yearling horse from Taoiseach Charles Haughey for IR£50,000. The tribunal considered that "The explanation advanced for the payment, namely that it was in consideration for the purchase of a yearling, is highly unconvincing and improbable".[24]

Passport-granting officials have also sold passports illegally, notably Kevin McDonald while working in London, who had sold "hundreds" of passports to criminals for up to £15,000 each in the 1980s, grossing $400,000. McDonald was prosecuted in 1989 and was sentenced to 21 months in jail.[25]

Increased demand following Brexit

[edit]After the UK's Brexit referendum on 23 June 2016, tens of thousands of Britons as well as many residents in Northern Ireland, applied for an Irish Passport.[26][27]

Senator Neale Richmond, chairman of the Brexit Committee in the Seanad, described in October 2018 the fast growth in the number of Irish passport applications received from the United Kingdom since the Brexit vote. There were 46,229 applications in 2015, the year before the referendum, "consistent with the annual average up to then". In 2016, the year of the Brexit vote, 63,453 applications were received, and there were 80,752 applications in 2017. In first half of 2018, the number was already at 44,962 applications. Richmond stated that "Embassy officials predict that based on this, 2018 will be the busiest year so far for Irish passport applications in the UK".[28][29]

98,544 applications for Irish passports were received from Great Britain in 2018, an increase of 22% on the previous year. The number of applications from Northern Ireland increased by 2% to 84,855.[30]

Passport booklet

[edit]

Physical appearance

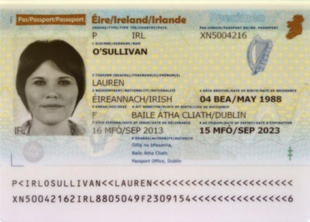

[edit]Irish passport booklets use the standard European Union design, with a machine-readable identity page and 32 or 66 visa pages. The cover bears the harp, the national symbol of Ireland. The words on the cover are in both of Ireland's official languages, Irish and English. The top of the cover page reads An tAontas Eorpach and the equivalent in English, European Union. Just above the harp are the words Éire and its equivalent in English, Ireland. The identity page on older Irish passport booklets was on the back cover of the booklet. Newly issued passport booklets have been redesigned with additional security features. The identity page is now a plastic card attached between the front cover and the first paper page (the "Observations" page).

The ePassport or biometric passport, was launched on 16 October 2006 with the first ePassports presented that day by the minister for foreign affairs.[31]

- Photo of passport holder, printed in greyscale.

- Type (P)

- Country (IRL)

- Passport number

- 1. Surname

- 2. Forename(s)

- 3. Nationality (Éireannach/Irish)

- 4. Date of Birth

- 5. Sex

- 6. Place of birth (county of birth if born on the island of Ireland (all 32 counties), 3 letter country code of country of birth if born elsewhere.)

- 7. Date of issue

- 8. Date of expiry

- 9. Authority

- 10. Signature

The information page ends with the machine readable zone starting with P<IRL.

Request page

[edit]Irish passport booklets contain a note on the inside cover which states:

In Irish:

- Iarrann Aire Gnóthaí Eachtracha agus Trádála na hÉireann ar gach n-aon lena mbaineann ligean dá shealbhóir seo, saoránach d'Éirinn, gabháil ar aghaidh gan bhac gan chosc agus gach cúnamh agus caomhnú is gá a thabhairt don sealbhóir.

In English:

- The Minister for Foreign Affairs and Trade of Ireland requests all whom it may concern to allow the bearer, a citizen of Ireland, to pass freely and without hindrance and to afford the bearer all necessary assistance and protection.

Formerly, the request was also made in French, but this has been discontinued as newer versions of the passport were introduced.

Languages

[edit]The data page/information page is printed in Irish, English and French. Each detail includes a reference number (e.g. "1 SLOINNE/SURNAME/NOM"). This reference number can be used to look up translations into any other EU language, as all EU passports share a standard text layout.

Security features

[edit]The latest Irish passport booklets have security features designed to make them difficult to forge or be mistaken as forgeries. They have also been optimised for machine reading.

The identity page of the passport booklet has been moved to the front of the passport and is now printed on a plastic card. This allows easier machine reading of the passport, as the official has to spend less time finding the identity page in the passport. The top-right corner of the passport booklet contains the biometric chip, which contains a copy of the information contained on the identity page, and a facial scan of the holder. To prevent unauthorised parties remotely accessing the information stored in the RFID biometric chip, the machine readable zone of the identity page must be scanned to unlock it.[32] This safeguard is known as Basic Access Control.

The title of the identity page "Éire/Ireland/Irlande" "Pas/Passport/Passeport" is printed in colour-changing ink, which varies from light green to gold-red, depending on the angle of the light shining on it. The background of the identity page is a complex celtic design, with the words "Éire Ireland" occasionally woven into the design.

The identity picture is now greyscale, and is digitally printed onto the surface of the page, rather than the actual photos sent by the applicant being pasted onto the page. The Irish harp is superimposed as a hologram onto the bottom right corner of the photograph. The words "Éire Ireland" are embossed several times into either side of the identity page. This embossing partially covers the photograph as an added security measure. A likeness of the photograph of the applicant is pin-punched into the surface of the identity page, and can be viewed when the identity page is held to light.

Under UV light, fluorescing fibres are visible on every page except the data page. The first sentence of Article 2 of the Irish constitution is visible under UV light and is printed in both Irish and English on alternate pages. The 2013 version of the passport also reveal a topographical map of Ireland on the observations page. Later pages include such landmarks as the Cliffs of Moher, the Samuel Beckett Bridge and the Aviva Stadium; there are excerpts from poems in Irish (by Nuala Ni Dhomhnaill), English (by William Butler Yeats) and Ulster Scots (by James Orr) and from the score of the national anthem, Amhrán na bhFiann (Irish for 'The Soldiers Song').[33]

Passport card

[edit]| Passport Card | |

|---|---|

| Type | Passport card; optional convenient addition/replacement for existing bearers of an Irish passport booklet for extra charge of €35 |

| Issued by | Ireland |

| Purpose | Proof of identity |

| Valid in | Rest of Europe (except Belarus, North Macedonia, Russia and Ukraine) |

| Eligibility | Irish citizens[5] |

| Expiration | 5 years or until expiry date of passport booklet (whichever comes first) |

A credit card-sized Passport Card was introduced on 5 October 2015.[34] It was originally announced as being available in mid-July 2015 but was subsequently delayed.[35][36] It conforms to international standards for biometric and machine readable travel documents promulgated by ICAO.[37]

Unlike the United States Passport Card, which cannot be used for international air travel or for land and sea travel outside North America, the Irish passport card can be used for air travel and throughout the European Economic Area and Switzerland and some non-EEA countries such as Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Moldova, Montenegro, Kosovo, Montserrat (max. 14 days in transit to a third country), Serbia, and the United Kingdom.[38] However, at introduction, it was only publicised as having been approved for entry and exit by countries in the EEA. A few days afterwards it was confirmed that Switzerland had given its approval.[39]

The Irish Passport Card is a passport in card format and is intended to be usable as a travel document in most European countries, in a similar way to national identity cards elsewhere in the EEA or the Russian internal passport with respect to travel to some countries and autonomous territories within the former USSR. It is largely treated in the same way as an identity card in several other EU countries,[40] since that is what their laws call such cards.[41][38] However, the IATA Timatic database used by airlines to find out document requirements lists the passport card as a separate document type. The card uses the designation "IP" in its machine readable zone (MRZ) (the "I" means identity card and the "P" is undefined in the MRZ standard). Although ICAO began preparatory work on machine readable passport cards as early as 1968, Ireland was the first country to issue one for air travel and the Irish Minister for Foreign Affairs and Trade, Charles Flanagan, highlighted the novelty and utility of Ireland's Passport Card at its 2015 introduction.[42][37]

The card costs €35, with a €10 discount if applied for at the same time as a passport book, and is valid for five years or the validity of the bearer's passport booklet, whichever is less. From November 2018, Passport Cards are available to Irish Citizens of all ages.[5]

Unlike national identity cards issued in other parts of the EU, an Irish passport card cannot be issued unless the bearer already has a valid passport booklet but, because of its convenient size and durable format compared to the Irish passport booklet, it will also serve purposes similar to that of national identity cards in other parts of the EU: identity and age verification, and intra-EU travel.[43]

Although they can be used at electronic passport control gates at Dublin Airport,[44] it was not possible, in 2018, to use this card at many electronic border gates/e-gates in continental Europe.

Regulation (EU) 2019/1157, which requires EEA national identity cards issued since 2 August 2021 to contain fingerprints, does not apply to the passport card issued by Ireland, as confirmed by Recital 14 in the preamble. However, the passport card directly follows ICAO document 9303, which gives other biometric requirements on which Regulation (EU) 2019/1157 is based.

Security features

[edit]Irish passport cards have security features designed to make them difficult to forge or be mistaken as forgeries. They have also been optimised for machine reading. The top-left corner of the passport card contains the biometric chip, which contains a copy of the information printed on the card, and a facial scan of the holder. To prevent unauthorised parties remotely accessing the information stored in the RFID biometric chip, the machine readable zone of the identity page must be scanned to unlock it. This safeguard is known as Basic Access Control.

The designation of the document "Éire/Ireland/Irlande" "Pas/Passport/Passeport" is printed in colour-changing ink, which varies from light green to gold-red, depending on the angle of the light shining on it. The background for the front of the passport card is a complex Celtic design, with the words for Ireland appearing in the official languages of the EU as part of the design.

The identity picture is greyscale, and is digitally printed onto the surface of the special security polycarbonate. The Irish harp is superimposed as a hologram onto the bottom right corner of the photograph. A likeness of the applicant in a hologram photo on a strip on the back:. According to Charles Flanagan, the then Foreign Affairs Minister, this is the first time such a security feature was going to be used on travel documents.[45][46] The Passport Card was updated in October 2021 to change the strip at the rear of the card from a silver reflective (OSM) strip to a SealCrypt strip.[47]

Ireland's passport card was joint winner of the 'Best Regional ID Document' at the High Security Printing Europe Conference in Bucharest, Romania in March 2016.[48]

Northern Ireland

[edit]

Irish nationality law does not distinguish between Northern Ireland and the rest of the island of Ireland. This means that those in Northern Ireland, or with ancestry in Northern Ireland, are covered by citizenship law of two states, the Republic of Ireland and the United Kingdom.

Anyone born on the island of Ireland (including Northern Ireland), before 1 January 2005, is entitled to Irish citizenship.[50]

In the 2011 census, 1,070,413 British and 375,826 Irish passports were held.[51] In the 2021 census, this was 1,000,207 British and 614,251 Irish passports.[52] Passports are travel documents and are not necessarily a full reflection of the complexity of a person's cultural and national identity. Under Irish law the use of a passport of another jurisdiction does not affect Irish citizenship.

A person born on or after 1 January 2005 on the island of Ireland is entitled to Irish citizenship if either or both parents were either Irish or British citizen(s), or entitled to live in Ireland or Northern Ireland without any time limit to their residency, or were legally resident in the island of Ireland for at least 3 out of the 4 years immediately before birth.[53]

Visa free travel

[edit]

Visa requirements for Irish citizens are travel restrictions placed upon citizens of Ireland by the authorities of other states. As of 5 June 2024, Irish citizens had visa-free or visa on arrival access to 193 countries and territories, ranking the Irish passport 2nd worldwide (tied with the Austrian, Finnish, Luxembourg, Dutch, South Korean, and Swedish passports) according to the Henley Passport Index.[54]

Notable cases of purported fraudulent use

[edit]An Irish passport, legitimate or fraudulent, is viewed by many – including intelligence services and journalists – as a highly valuable and 'safe' document due to Ireland's policy of neutrality.[55]

- Oliver North (using the name "John Clancy") a United States Marine Corps Lieutenant Colonel and a central figure in the Iran-Contra scandal, carried a false Irish passport while visiting Iran in 1986, as did his fellow covert operatives.[56][57] This was part of a series of events that became known as the Iran–Contra affair.

- In December 2005, Ireland's Minister for Justice Michael McDowell accused journalist Frank Connolly of having travelled to Colombia in 2001 on a falsely obtained Irish passport in connection with the group known as the Colombia Three.[58] Connolly, who worked at the Centre for Public Inquiry, (intended as a public watch-dog organisation), vigorously denied the allegation and in turn accused the Minister of abusing his position.[59]

- On 19 January 2010, Mahmoud al-Mabhouh, a senior Hamas military commander, was assassinated in Dubai by a team involving at least 11 Israeli individuals, three of whom were initially reported as using counterfeit Irish passports.[60] The number of forged Irish passports used in the killing was later revised upwards to eight following a Garda and Department of Foreign Affairs investigation.[61] The Irish government responded by expelling a staff member of the Israeli Embassy in Dublin. It stated that it considered "an Israeli government agency was responsible for the misuse and, most likely, the manufacture of the forged Irish passports associated with the murder of Mr. Mabhouh."[62]

- In June 2010 it was alleged that one of ten covert sleeper agents of the Russian government under non-official cover in the United States as part of the "Illegals Program" used a forged Irish passport issued in the name of "Eunan Gerard Doherty" to "Richard Murphy."[63] The Russian embassy in Dublin reportedly declined to comment on the allegations that its officials had used a counterfeit Irish passport.[64] "Richard Murphy," who later identified himself as Russian national Vladimir Guryev, was repatriated to Russia, along with the other nine members of the Illegals Program, as part of a prisoner exchange.[65] It later emerged that the passports of up to six Irish citizens may have been compromised by the Russian agents.[66] This led to the expulsion of a Dublin-based Russian diplomat in February 2011.[67]

Eligibility for an Irish passport

[edit]In 1978 the High Court ruled that among the unenumerated rights of citizens implicit in Article 40.3 of the Constitution are the right to travel outside the state and by extension the right to a passport.[68] However, the state may limit this right for purposes of national security, and courts also have the power to confiscate passports of criminal defendants.[68][69][70][71] Citizenship is defined by Irish nationality law; non citizens cannot have passports. Adult passport booklets are generally valid for 10 years and child passport booklets valid for 5 years. The validity of passport booklets can be limited by the Passport Office for certain individuals, especially those who have lost two or more passports. Passport cards are valid for 5 years or the validity of the corresponding passport booklet, whichever is the lesser period.

Gallery of historic images

[edit]-

Irish Free State passport cover as issued 1927 (holder's name removed)

-

... and its associated 'Request' page.

-

Passport from 1950

-

Passport from 1978

-

Two shilling passport revenue stamp, 1939.

-

Prior to Irish independence, British passports were used

See also

[edit]- Driving licence in the Republic of Ireland

- Irish nationality law

- Passports of the European Union

- Visa requirements for Irish citizens

Notes

[edit]- ^ in Irish

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Council of the European Union - PRADO - IRL-AO-04001". www.consilium.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 5 October 2021. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- ^ "Council of the European Union - PRADO - IRL-TO-01002". www.consilium.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 5 October 2021. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- ^ "Passport Fees - Department of Foreign Affairs".

- ^ "Passport fees - How much does a passport cost?". Department of Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 22 January 2018. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- ^ a b c Ó Conghaile, Pól (28 November 2018). "Irish Passport Cards and online passport renewal now available for children". Irish Independent. Dublin: Independent News & Media. Archived from the original on 5 October 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- ^ "Passport Ranking 2023". Henley & Partners. 2023. Retrieved 7 March 2023.

- ^ "Constitution of the Irish Free State (Saorstát Eireann) Act, 1922". Irishstatutebook.ie. 6 December 1921. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- ^ a b "Despatch, T.M. Healy to J.H. Thomas from T.M. Healy to J.H. Thomas - 04 March 1924 - Documents on IRISH FOREIGN POLICY". Difp.ie. 4 March 1924. Archived from the original on 2 December 2017. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- ^ "Letter, Walshe to O'Hegarty enclosing a memorandum from FitzGerald to Walshe from Joseph Walshe to Diarmuid O'Hegarty - 28 December 1923 - Documents on IRISH FOREIGN POLICY". Difp.ie. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- ^ "Irish delegation to Geneva". The Irish Times. Dublin. 8 September 1923. p. 4.

The Irish delegation to the League of Nations left Kingstown last week by the mail boat Soctia, en route for Geneva...[seeking] admission for the Irish Free State to the League of Nations...The party are travelling on Irish passports. This is the first occasion on which Irish passports have come into use.

- ^ O'Halpin, Eunan (1999). Defending Ireland: The Irish State and its Enemies since 1922. Oxford University Press. p. 75. ISBN 0-19-820426-4. Archived from the original on 19 December 2021. Retrieved 24 September 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b "Passports from Gearóid Ó Lochlainn to J.P. Walshe - 20 August 1927 - Documents on IRISH FOREIGN POLICY". Difp.ie. 20 August 1927. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- ^ a b 'Irish Nationality and Citizenship since 1922' by Mary E. Daly, in 'Irish Historical Studies' Vol. 32, No. 127, May, 2001 (pp. 377-407)

- ^ a b c British Archives, Memorandum to Cabinet dated 1 March 1939 by Thomas WH Inskip

- ^ a b Resolution of the Representatives of the Governments of the Member States of the European Communities, Meeting Within the Council of 23 June 1981 Archived 15 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Official Journal of the European Communities. C 241. also EUR-Lex - 41981X0919 - EN Archived 1 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Fanning, Mary (12 November 1984). "Green Passport Goes Burgendy 1984: New Passports for European Member States Will Have a Common Look and Format". RTE News Archives. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021.

- ^ a b Publications, Europa (1999). The European Union Encyclopedia and Directory (3rd ed.). Psychology Press. p. 63. ISBN 9781857430561.

- ^ "Seanad Éireann - Volume 154 - 04 March, 1998 - Passports for Investme…". archive.is. 10 July 2012. Archived from the original on 10 July 2012.

- ^ Dundon, Mary (1 June 1998). "Ahern facing grassroots revolt over Burke affair". Irish Examiner. Cork: Thomas Crosbie Holdings. Archived from the original on 29 January 2009. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ^ Reilly, Jerome (22 October 2006). "Gettys seek return of €4m from 'passports for sale' scheme". Irish Independent. Dublin: Independent News & Media. Archived from the original on 30 March 2017. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ^ Collins, Neil; O'Shea, Mary (2000). Understanding corruption in Irish politics. Undercurrents. Vol. 17. Cork University Press. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-1-85915-273-7. Retrieved 20 October 2011 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Turner and the casino plan: background". RTÉ News. RTÉ. 31 January 2008. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ^ "Ahern helped businessman get passport". RTÉ News. RTÉ. 31 January 2008. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ^ "17: Irish Passports and "Mr. Fustok's Friends"" (PDF). Report of the Tribunal of Inquiry into Payments to Politicians and Related Matters. Moriarty Tribunal (Report). Vol. Part 1. Dublin. p. 422. ISBN 0-7557-7459-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 May 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- ^ "Irish Official Suspected of Passport Selling". Los Angeles Times. London. Press Association. 13 April 1987. eISSN 2165-1736. Archived from the original on 17 February 2020. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- ^ Tamplin, Harley (25 June 2016). "Northern Irish people are scrambling for Irish passports after Brexit". Metro Online. DMG Media. Archived from the original on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

Post Offices across Northern Ireland have run out of Irish passport forms as demand sky-rocketed following Britain's decision to Leave the EU.

- ^ McDonald, Henry; Duncan, Pamela (13 October 2016). "Huge rise in Britons applying for Irish citizenship after Brexit vote". The Guardian. London. eISSN 1756-3224. Archived from the original on 21 October 2016. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- ^ "UK demand for Irish passports surges as Brexit nears". RTÉ News. RTÉ. 31 October 2018. Archived from the original on 3 November 2018. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ^ Hunt, Conor (30 October 2018). "Govt denies 15,000 British residents were refused Irish passports". RTÉ News. RTÉ. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ^ "Record-breaking year for Irish passports as 822,000 issued". The Irish Times. Dublin. 31 December 2018. Archived from the original on 20 October 2019. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- ^ "Minister for Foreign Affairs, Dermot Ahern TD, Launches new ePassport, 16th October 2006". Department of Foreign Affairs (Press release). 16 October 2006. Archived from the original on 17 June 2009. Retrieved 28 March 2009.

- ^ "ePassports FAQs". Department of Foreign Affairs. 15 March 2008. Archived from the original on 15 March 2008. Retrieved 24 March 2008.

- ^ "The New Irish Passport". Department of Foreign Affairs (Press release). 30 September 2013. Archived from the original on 21 June 2018. Retrieved 5 June 2018.; Hutton, Brian (30 September 2013). "New Irish passport launched". The Irish Independent. Dublin: Independent News & Media. ISSN 0021-1222. Archived from the original on 21 June 2018. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ^ Kelly, Fiach (5 October 2015). "Credit-card size passport for European travel available today". The Irish Times. Dublin. Archived from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- ^ "Minister for Foreign Affairs and Trade, Charles Flanagan, announces new Irish Passport Card". Department of Foreign Affairs (Press release). 26 January 2015. Archived from the original on 15 November 2017. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- ^ McMahon, Aine (21 December 2014). "New passport card for travel in EU arriving early in 2015". The Irish Times. Dublin. Archived from the original on 13 September 2017. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- ^ a b "Doc 9303: Machine Readable Travel Documents" (PDF) (Seventh ed.). International Civil Aviation Organization. 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 July 2021. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

ICAO's work on machine readable travel documents began in 1968 with the establishment, by the Air Transport Committee of the Council, of a Panel on Passport Cards. This Panel was charged with developing recommendations for a standardized passport book or card that would be machine readable, in the interest of accelerating the clearance of passengers through passport controls. ... In 1998, the New Technologies Working Group of the TAG/MRTD began work to establish the most effective biometric identification system and associated means of data storage for use in MRTD applications, particularly in relation to document issuance and immigration considerations. The bulk of the work had been completed by the time the events of 11 September 2001 caused States to attach greater importance to the security of a travel document and the identification of its holder. The work was quickly finalized and endorsed by the TAG/MRTD and the Air Transport Committee. ... The Seventh Edition of Doc 9303 represents a restructuring of the ICAO specifications for Machine Readable Travel Documents. Without incorporating substantial modifications to the specifications, in this new edition Doc 9303 has been reformatted into a set of specifications for Size 1 Machine Readable Official Travel Documents (TD1), Size 2 Machine Readable Official Travel Documents (TD2), and Size 3 Machine Readable Travel Documents (TD3) ...

- ^ a b "Entering the UK". gov.uk. Archived from the original on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ^ Written answers to questions asked in the Irish Parliament on Tuesday, 13 October 2015 quoted in kildarestreet.com Archived 5 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine and accessed 2 December 2015: "Q 345: Paul Murphy (Dublin South West, Socialist Party) To ask the Minister for Foreign Affairs and Trade further to Parliamentary Question No. 483 of 10 February 2015, and the contradictory information on the Department website (details supplied), if he will confirm whether the passport card is valid for travel to Switzerland. [35223/15]. A 345: Charles Flanagan (Minister, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade; Laois-Offaly, Fine Gael) On 5 October I launched the passport card which will facilitate travel by Irish citizens within all thirty countries of the European Union and the European Economic Area. Last week, my Department, through the Embassy in Berne, received confirmation from the authorities in Switzerland that they will also accept the passport card for travel. Our website has been updated accordingly."

- ^ There are references for Sweden and UK nine words to the right

- ^ "Utlänningsförordning (2006:97)" [Aliens Regulation (2006: 97)]. Notisum.se [17 § An identity card for a foreigner who is a national of the issuing state which indicates citizenship and is issued by a competent authority in an EEA state or Switzerland, is valid as a passport at the alien's arrival to and departure from Sweden, and while the alien is permitted to stay here.] (in Swedish). Karnov Group. 23 February 2006. Archived from the original on 17 February 2020. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- ^ "Minister Flanagan Launches Irish Passport Card for Use in 30 European Countries". Department of Foreign Affairs (Press release). 2 October 2015. Archived from the original on 5 October 2021. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

The introduction of the passport card is a significant innovation that will enhance the travel experience for Irish people as they go on holidays or business trips ... I am particularly proud that we are one of the very first countries in the world to introduce such a passport card. It represents a very positive story of Irish-led creative thinking and innovation and illustrates that we are very much pioneers in this area.

- ^ "Passport Card FAQ". Department of Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 25 November 2015. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- ^ Ó Conghaile, Pól (30 November 2017). "New passport machines and 'e-Gates' have opened at Dublin Airport". Irish Independent. Dublin: Independent News & Media. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- ^ "Irish passport card delayed to improve its durability". SecurityDocumentWorld.com. Science Media Partners. 16 July 2015. Archived from the original on 7 July 2018. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

A hologram photo on a strip on the back is the first time this security feature will be used on travel documents.

- ^ "Ireland rolls out new passport card". SecurityDocumentWorld.com. Science Media Partners. 13 October 2015. Archived from the original on 10 July 2018. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- ^ "Passport Card - changes to the Passport Card 2021". Department of Foreign Affairs. 19 January 2024. Archived from the original on 19 January 2024. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^ Mayhew, Stephen (4 April 2016). "Ireland's selfie-friendly passport card wins international security award". BiometricUpdate.com. Biometrics Research Group. Archived from the original on 5 April 2016. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

Ireland's new selfie-friendly passport card was a joint winner of the Best Regional ID Document at last month's High Security Printing Europe Conference in Bucharest, Romania.

- ^ "Passports Held - 18 Categories by Religion or Religion Brought Up In". Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ^ Citizensinformation.ie. "Entitlement to Irish citizenship". www.citizensinformation.ie. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ^ "Northern Ireland Neighbourhood Information Service". Retrieved 8 September 2024.

- ^ "Passports Held". Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. Retrieved 12 August 2024.

- ^ Citizensinformation.ie. "Entitlement to Irish citizenship". www.citizensinformation.ie. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ^ "The Official Passport Index Ranking". Henley & Partners. Retrieved 29 September 2022.

- ^ "Nice and neutral: why Irish passports are a spook's best friend". Irish Times. 20 February 2010. Archived from the original on 9 February 2012. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- ^ North, Oliver (2003). War stories: Operation Iraqi Freedom. Vol. 1. Regnery Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-89526-063-5. Archived from the original on 19 December 2021. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- ^ Persico, Joseph E. (1990). Casey: from the OSS to the CIA. Publisher Viking. p. 503. ISBN 978-0-670-82342-0. Archived from the original on 19 December 2021. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- ^ "Connolly accused of using false passport". RTÉ News. 6 December 2005. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- ^ "US backer withdraws funding for CPI". RTÉ News. 7 December 2005. Archived from the original on 17 January 2008. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- ^ "'Hit squad' used fake Irish passports". Independent.ie. 16 February 2010. Archived from the original on 18 February 2010. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- ^ "Irish to expel Israeli diplomat over Hamas killing". BBC News. 15 June 2010. Archived from the original on 15 June 2010. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "Statement on... fraudulent use of Irish passports in the assassination of Mr. Mahmoud al Mabhouh". Irish Department of Foreign Affairs. 15 June 2010. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "False Irish passport 'used by spy ring'". UTV News. 29 June 2010. Archived from the original on 1 July 2010. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ^ "False Irish passport 'used by spy subject'". The Sunday Business Post. ThePost.ie. 29 June 2010. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ^ Moore, Kevin; Johnson, Martha T. (9 July 2010). "Pleas in Russian spy case set deal in motion". USA Today. New York: Gannett. Associated Press. ISSN 0734-7456. Archived from the original on 2 November 2012. Retrieved 11 July 2010.

- ^ Brady, Tom; Guidera, Anita (12 October 2010). "Russian spy ring linked to forged Irish passports". Irish Independent. Dublin: Independent News & Media. Archived from the original on 13 October 2010. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- ^ "Russian diplomat expelled over fake passports". RTÉ News. RTÉ. 1 February 2011. Archived from the original on 16 March 2016. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- ^ a b

- State (M.) v Attorney General, [1979 IR 73] (High Court 29 May 1978).

- Kelly, J. M.; Hogan, Gerard W; Whyte, Gerry (2003). The Irish Constitution (4th ed.). Dublin: Butterworths. pp. 173–174. ISBN 1-85475-8950.

- ^ "Fundamental Rights under the Irish Constitution". www.citizensinformation.ie. Archived from the original on 14 November 2010. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- ^ "10.4 Issue of Passports to Irish Citizens: Eligibility". Section 16 Reference Book (Microsoft Word Document). Department of Foreign Affairs. p. 54. Archived from the original (DOC) on 9 July 2013. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- ^ "A.G. v. X [1992] IESC 1; [1992] 1 IR 1 (5th March, 1992)". 18 July 2012. Archived from the original on 18 July 2012 – via archive.today.

Further reading

[edit]- Torpey, John C. (2000). The Invention of the Passport: Surveillance, Citizenship, and the State. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-63493-9.

- Lloyd, Martin (2003). The Passport: The History of Man's Most Travelled Document. Sutton. ISBN 978-0-7509-2964-6.

- O'Grady, Joseph P. (November 1989). "The Irish Free State Passport and the Question of Citizenship, 1921-4". Irish Historical Studies. 26 (104): 396–405. doi:10.1017/S0021121400010130. JSTOR 30008695. S2CID 159821785.

- Daly, Mary E. (May 2001). "Irish Nationality and Citizenship since 1922". Irish Historical Studies. 32 (127): 377–407. doi:10.1017/S0021121400015078. JSTOR 30007221. S2CID 159806730.