Jordan: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

|||

| Line 107: | Line 107: | ||

In antiquity, the present day Jordan became a home for several [[Semitic]] [[Canaanite languages|Canaanite-speaking]] ancient kingdoms, including the kingdom of [[Edom]], the kingdom of [[Moab]], the kingdom of [[Ammon]], [[Kingdom of Israel (united monarchy)|the kingdom of Israel]] and also the [[Amalekites]]. Throughout different eras of history, the region and its nations were subject to the control of powerful foreign empires; including the [[Akkadian Empire]] (2335-2193 BC), [[Ancient Egypt]] (15th to 13th centuries BC), [[Hittite Empire]] (14th and 13th centuries BC), the [[Middle Assyrian Empire]] (1365-1020 BC), [[Neo-Assyrian Empire]] (911-605 BC), the [[Neo-Babylonian Empire]] (604-539 BC) and the [[Achaemenid Empire]] (539-332 BC) and, for discrete periods of times, by [[Israelites]]. The [[Mesha Stele]] recorded the glory of the [[List of rulers of Edom|King of Edom]] and the victories over the Israelites and other nations. The Ammon and Moab kingdoms are mentioned in ancient maps, Near Eastern documents, ancient [[Greco-Roman world|Greco-Roman]] artifacts, and Christian and Jewish religious scriptures.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.bibleplaces.com/edom.htm |title=Edom |publisher=BiblePlaces.com |accessdate=15 June 2010}}</ref> |

In antiquity, the present day Jordan became a home for several [[Semitic]] [[Canaanite languages|Canaanite-speaking]] ancient kingdoms, including the kingdom of [[Edom]], the kingdom of [[Moab]], the kingdom of [[Ammon]], [[Kingdom of Israel (united monarchy)|the kingdom of Israel]] and also the [[Amalekites]]. Throughout different eras of history, the region and its nations were subject to the control of powerful foreign empires; including the [[Akkadian Empire]] (2335-2193 BC), [[Ancient Egypt]] (15th to 13th centuries BC), [[Hittite Empire]] (14th and 13th centuries BC), the [[Middle Assyrian Empire]] (1365-1020 BC), [[Neo-Assyrian Empire]] (911-605 BC), the [[Neo-Babylonian Empire]] (604-539 BC) and the [[Achaemenid Empire]] (539-332 BC) and, for discrete periods of times, by [[Israelites]]. The [[Mesha Stele]] recorded the glory of the [[List of rulers of Edom|King of Edom]] and the victories over the Israelites and other nations. The Ammon and Moab kingdoms are mentioned in ancient maps, Near Eastern documents, ancient [[Greco-Roman world|Greco-Roman]] artifacts, and Christian and Jewish religious scriptures.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.bibleplaces.com/edom.htm |title=Edom |publisher=BiblePlaces.com |accessdate=15 June 2010}}</ref> |

||

everyone from this shitehole are all idiots and probably a terriorist |

|||

===Classical Transjordan=== |

===Classical Transjordan=== |

||

[[File:MiddleEast tmo 2013349.jpg|thumb|500px|Jordan and its neighbors with a rare dusting of snow in several regions.<ref>[http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/IOTD/view.php?id=82611 Rare Middle Eastern Snow - December 17, 201]</ref>]] |

[[File:MiddleEast tmo 2013349.jpg|thumb|500px|Jordan and its neighbors with a rare dusting of snow in several regions.<ref>[http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/IOTD/view.php?id=82611 Rare Middle Eastern Snow - December 17, 201]</ref>]] |

||

Revision as of 11:06, 25 March 2014

Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan المملكة الأردنية الهاشمية al-Mamlakah al-Urdunīyah al-Hāshimīyah | |

|---|---|

| Motto: الله، الوطن، الملك (Arabic) Allāh, al-Waṭan, al-Malik "God, Country, The King"[citation needed] | |

| Anthem: السلام الملكي الأردني as-Salām al-Malakī al-Urdunī Long Live the King | |

Location and extent of Jordan (red) in Asia. | |

| Capital and largest city | Amman |

| Official languages | Arabic[1] |

| Ethnic groups |

|

| Demonym(s) | Jordanian |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy[2] |

• King | Abdullah II |

| Abdullah Ensour | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Senate | |

| Chamber of Deputies | |

| Independence | |

• League of Nations mandate ended | 25 May 1946 |

| Area | |

• Total | 89,342 km2 (34,495 sq mi) (112th) |

• Water (%) | 0.8 |

| Population | |

• July 2014 estimate | 7,930,491[3] (98th) |

• July 2004 census | 5,611,202 |

• Density | 68.4/km2 (177.2/sq mi) (133rd) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2011 estimate |

• Total | $39.29 billion (2012 est.)[3] (98th) |

• Per capita | $6,100 (2012 est.)[3] (108th) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2011 estimate |

• Total | $29.233 billion[4] (90th) |

• Per capita | $4,674[4] (96th) |

| Gini (2010) | 35.4[5] medium inequality |

| HDI (2013) | high (100th) |

| Currency | Jordanian dinar (JOD) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (UTC+2[7]) |

| Drives on | right |

| Calling code | +962 |

| ISO 3166 code | JO |

| Internet TLD | |

| |

Jordan (/ˈdʒɔːrdən/; Arabic: الأردن al-Urdun), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan (Arabic: المملكة الأردنية الهاشمية al-Mamlakah al-Urdunīyah al-Hāshimīyah), is an Arab kingdom in Western Asia, on the East Bank of the Jordan River, and extending into the historic region of Palestine. Jordan borders Saudi Arabia to the south and east, Iraq to the north-east, Syria to the north, and Palestine, the Dead Sea and Israel to the west.

The kingdom emerged from the post-World War I division of West Asia by Britain and France. In 1946, Jordan became an independent sovereign state officially known as the Hashemite Kingdom of Transjordan. After capturing the West Bank during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, Abdullah I took the title King of Jordan and Palestine. The name of the state was changed to The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan on 1 December 1948.[8]

Although Jordan is a constitutional monarchy, the king holds wide executive and legislative powers. Jordan is classified as a country of "medium human development"[9] by the 2011 Human Development Report, and an emerging market with the third freest economy in West Asia and North Africa (32nd freest worldwide).[10] Jordan has an "upper middle income" economy.[11] Jordan has enjoyed "advanced status" with the European Union since December 2010,[12] and it is a member of the Euro-Mediterranean free trade area. It is also a founding member of the Arab League[13] and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC).

History

In antiquity, the present day Jordan became a home for several Semitic Canaanite-speaking ancient kingdoms, including the kingdom of Edom, the kingdom of Moab, the kingdom of Ammon, the kingdom of Israel and also the Amalekites. Throughout different eras of history, the region and its nations were subject to the control of powerful foreign empires; including the Akkadian Empire (2335-2193 BC), Ancient Egypt (15th to 13th centuries BC), Hittite Empire (14th and 13th centuries BC), the Middle Assyrian Empire (1365-1020 BC), Neo-Assyrian Empire (911-605 BC), the Neo-Babylonian Empire (604-539 BC) and the Achaemenid Empire (539-332 BC) and, for discrete periods of times, by Israelites. The Mesha Stele recorded the glory of the King of Edom and the victories over the Israelites and other nations. The Ammon and Moab kingdoms are mentioned in ancient maps, Near Eastern documents, ancient Greco-Roman artifacts, and Christian and Jewish religious scriptures.[14]

everyone from this shitehole are all idiots and probably a terriorist

Classical Transjordan

Due to its strategic location in the middle of the ancient world, Transjordan came to be controlled by the ancient empires of Persians and later the Macedonian Greeks, who became the dominant force in the region, following the conquests of Alexander the Great. It later fell under the changing influence of the Hellenistic Seleucid Empire from the North and the Parthians from the East.

The Aramaic speaking Nabatean kingdom was one of the most prominent states in the region through the middle classic period, since the decline of the Seleucid control of the region in 168 BC. The Nabateans were most probably people of mixed Aramean, Canaanite and Arabian ancestry, who fell under the early influence of the Hellenistic and Parthian cultures, creating a unique civilized society, which roamed the roads of the deserts. They controlled the regional and international trade routes of the ancient world by dominating a large area southwest of the Fertile Crescent, which included the whole of modern Jordan in addition to the southern part of Syria in the north and the northern part of Arabian Peninsula in the south. The Nabataeans developed the Nabatean Alphabet, a descendant of the Aramaic alphabet, which was eventually to lead to the formation of the Arabic Script in the 4th century AD.[16] Their language was originally Aramaic (a West Semitic language), but became infused with South Semitic Arabic with the migration of Arab tribes into Nabatea in the 3rd and 4th centuries AD.[17] It acted as an intermediary between Aramaean and Classical Arabic, the latter of which evolved into Modern Arabic.

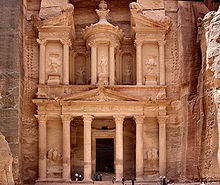

The Nabateans were largely conquered by the Hasmonean rulers of Judea and many of them forced to convert to Judaism in the late 2nd century BC. However, the Nabataeans managed to maintain a sort of semi-independent kingdom, which covered most parts of modern Jordan and beyond, before it was taken by the Herodians and finally annexed by the still expanding Roman Empire in 106 AD. However, apart from Petra, the Romans maintained the prosperity of most of the ancient cities in Transjordan which enjoyed a sort of city-state autonomy under the umbrella of the alliance of the Decapolis. Nabataean civilization left many magnificent archaeological sites at Petra, which is considered one of the New 7 Wonders of the World as well as recognized by the UNESCO as a World Heritage Site.

Following the establishment of Roman Empire at Syria, the country was incorporated into the client Judaean Kingdom of Herod, and later the Judaea Province. With the suppression of Jewish Revolts, the eastern bank of Transjordan was incorporated into the Syria Palaestina province, while the eastern deserts fell under Parthian and later Persian Sassanid control. During the Greco-Roman period, a number of semi-independent city-states also developed in the region of Transjordan under the umbrella of the Decapolis including: Gerasa (Jerash), Philadelphia (Amman), Raphana (Abila), Dion (Capitolias), Gadara (Umm Qais), and Pella (Irbid).

With the decline of the Eastern Roman Empire, Transjordan came to be controlled by the Christian Ghassanid Arab kingdom, which allied with Byzantium. The Byzantine site of Umm ar-Rasas is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Middle Ages to World War I

Due to its proximity to Damascus, Transjordan became in the 7th century a heartland for the Arabic Islamic Empire and therefore secured several centuries of stability and prosperity,[citation needed] which allowed the coining of its current Arabic Islamic identity. Different Caliphates' stages, including the Rashidun Empire, Umayyad Empire and Abbasid Empire controlled the region. Several resources pointed that the Abbasid movement, was started in region of Transjordan before it took over the Umayyad empire. After the decline of the Abbasid, It was ruled by several conflicting powers including the Mongols, the Crusaders, the Ayyubids and the Mamluks until it became part of the Ottoman Empire in 1516.[18]

The Umayyad caliphs constructed rural estates such as Qasr Mshatta, Qasr al Hallabat, Qasr Kharana, Qasr Tuba, and Qasr Amra. Castles constructed in the later Middle Ages including Ajloun, Al Karak, and Qasr Azraq were used in the Ayyubid, Crusader, and Mamluk eras.

In the 11th century, Transjordan witnessed a phase of instability, as it became a battlefield for the Crusades which ended with defeat by the Ayyubids. Jordan suffered also from the Mongol attacks which were blocked by Mamluks. In 1516, Transjordan became part of the Ottoman Empire and remained so until 1918, when the Hashemite Army of the Great Arab Revolt took over, and secured the present day Jordan with the help and support of Transjordanian local tribes.

During World War I, the Transjordanian tribes fought, along with other tribes of the Hijaz, the Tihamah, and Levant regions, as part of the Arab Army of the Great Arab Revolt. The revolt was launched by the Hashemites and led by Sherif Hussein of Mecca against the Ottoman Empire. It was supported by the Allies of World War I. The chronicle of the revolt was written by T. E. Lawrence who, as a young British Army officer, played a liaison role during the revolt. He published the chronicle in London, 1922 under the title "Seven Pillars of Wisdom",[19] which was the basis for the iconic movie "Lawrence of Arabia".

The Great Arab Revolt was successful in gaining independence for most of the territories of Hijaz and the Levant, including the region of east of Jordan. However, it failed to gain international recognition of the region as an independent state, due mainly to the secret Sykes–Picot Agreement of 1916 and the Balfour Declaration of 1917.[citation needed] This was seen by the Hashemites and the Arabs as betrayal of the previous agreements with the British, including the McMahon–Hussein Correspondence in 1915, in which the British stated their willingness to recognize the independence of the Arab state in Hijaz and the Levant. However, a compromise was eventually reached and the Emirate of Transjordan was created under the reign of the Hashemites.

British Transjordan mandate

In September 1922, the Council of the League of Nations recognized Transjordan as a state under the British Mandate and Transjordan memorandum excluded the territories east of the Jordan River from all of the provisions of the mandate dealing with Jewish settlement.[20] The Permanent Court of International Justice and an International Court of Arbitration established by the Council of the League of Nations handed down rulings in 1925 which determined that both a Jewish and an Arab state in the Mandatory regions of Palestine and Transjordan were to be newly created successor states of the Ottoman Empire as defined by international law.[21] The country remained under British supervision until 1946.

The Hashemite leadership met multiple difficulties upon assuming power in the region. The most serious threats to Emir Abdullah's position in Transjordan were repeated Wahhabi incursions from Najd into southern parts of his territory.[22] The emir was unable to repel those raids without support, so the British maintained a military base, with a small RAF detachment, at Marka, close to Amman.[22] The British force was also used to help the emir (and, subsequently, Sultan Adwan) suppress local rebellions at Kura in 1921 and 1923.[22]

Independence

On 25 May 1946, the United Nations approved the end of the British Mandate and recognized Transjordan as an independent sovereign kingdom. The Parliament of Transjordan proclaimed King Abdullah as the first King.

The name was changed from Transjordan to Jordan in 1948.[8] According to the prime minister Tewfik Abul Huda at the time, the name of the kingdom had been changed in 1946. On June 1, 1949, he issued a public notice:

It is to be remembered that the decision of the Houses of Parliament which was taken on May 25, 1946, and which declared the independence of this country said that the name of this Kingdom is the "Hashemite Kingdom of the Jordan." The Jordan Constitution, published at the beginning of February, 1947, approved this decision. However, it is noticed that the name of "Transjordan" is still applied to this Kingdom, and certain people and official institutions still use the old name in Arabic and foreign languages, which makes me obliged to point out to all who are concerned that the correct and official name which should be officially used in all cases is : Al-Mamlakeh Al-Urdunieh Al-Hashemieh and in English "The Hashemite Kingdom of the Jordan."[23]

Following the war with Israel in 1948 Jordan occupied the West Bank and on 24 April 1950 Jordan formally annexed these territories, an act that was regarded as illegal and void by the Arab League. The move formed part of Jordan’s "Greater Syria Plan" expansionist policy,[24] and in response, Saudi Arabia, Lebanon and Syria joined Egypt in demanding Jordan’s expulsion from the Arab League.[25][26] A motion to expel Jordan from the League was prevented by the dissenting votes of Yemen and Iraq.[27] On 12 June 1950, the Arab League declared the annexation was a temporary, practical measure and that Jordan was holding the territory as a “trustee” pending a future settlement.[28][29]

On 20 July 1951, as he was leaving the al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem, Abdullah I was assassinated by Mustafa Ashu, a Palestinian al-Jihad al-Muqaddas militant. The reason for his murder was, allegedly,[citation needed] the power rivalry of the al-Husseinis over control of Palestine, which Abdullah I had declared a part of the Hashemite Kingdom. Though Amin al-Husseini, the former Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, was not directly charged in the plot, Musa al-Husseini was among the six executed by Jordanian authorities following the assassination.

On 27 July 1953, King Hussein of Jordan announced that East Jerusalem was "the capital of the Hashemite Kingdom" and would form an "integral and inseparable part" of Jordan.[30] In 1957, Jordan terminated the Anglo-Jordanian treaty, one year after the king sacked the British personnel serving in the Jordanian Army. This act of Arabization ensured the complete sovereignty of Jordan as a fully independent nation.

In June 1967, having signed a military pact with Egypt the previous month, Jordan joined Egypt, Syria and Iraq in the Six-Day War against Israel. It ended in an Israeli victory and the capture of the West Bank. The period following the war saw an upsurge in the activity and numbers of Palestinian paramilitary elements (fedayeen) within the state of Jordan. These distinct, armed militias were becoming a "state within a state", threatening Jordan's rule of law. King Hussein's armed forces targeted the fedayeen and open fighting erupted in June 1970. The battle in which Palestinian fighters from various Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) groups were expelled from Jordan is commonly known as Black September.

The heaviest fighting occurred in northern Jordan and Amman, during which a Syrian tank force invaded northern Jordan to back the fedayeen fighters but subsequently retreated. King Hussein urgently asked the United States and Great Britain to intervene against Syria. Consequently, Israel performed mock air strikes on the Syrian column at the Americans' request. Soon after, Syrian President Nureddin al-Atassi ordered a hasty retreat from Jordanian soil.[31][32] By 22 September, Arab foreign ministers meeting in Cairo arranged a cease-fire beginning the following day. However, sporadic violence continued until Jordanian forces, led by Habis Al-Majali, managed to expel the fedayeen in July 1971 with the help of Iraqi forces.[33] The PLO's Yasser Arafat soon followed.

In 1973, allied Arab League forces attacked Israel in the Yom Kippur War and fighting occurred along the 1967 Jordan River cease-fire line. Jordan sent a brigade to Syria to attack Israeli units on Syrian territory but did not engage Israeli forces from Jordanian territory. At the Rabat summit conference in 1974, Jordan was now in a more secure position to agree, along with the rest of the Arab League, that the PLO was the "sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people", thereby relinquishing Jordan's role as representative of the West Bank to it.

The Amman Agreement of 11 February 1985, declared that the PLO and Jordan would pursue a proposed confederation between the state of Jordan and a Palestinian state.[34] In 1988, King Hussein dissolved the Jordanian parliament and renounced Jordanian claims to the West Bank. The PLO assumed responsibility as the Provisional Government of Palestine and an independent state was declared.[35]

In 1991, Jordan agreed to participate in direct peace negotiations with Israel at the Madrid Conference, sponsored by the US and the Soviet Union. It negotiated an end to hostilities with Israel and signed a declaration to that effect on 25 July 1994. As a result, an Israeli-Jordanian peace treaty was concluded on 26 October 1994. King Hussein was later honored when his picture appeared on an Israeli postage stamp in recognition of the good relations he established with his neighbor. Since the signing of the peace treaty, the United States not only contributes hundreds of millions of dollars in an annual foreign aid stipend to Jordan, but also has allowed it to establish a free trade zone in which to manufacture goods that will enter the US without paying the usual import taxes as long as a percentage of the material used in them is purchased in Israel.

The last major strain in Jordan's relations with Israel occurred in September 1997 when Israeli agents allegedly[citation needed] entered Jordan using Canadian passports and poisoned Khaled Meshal, a senior Hamas leader. Israel provided an antidote to the poison and released dozens of political prisoners, including Sheikh Ahmed Yassin.

Upon the death of his father Hussein, Abdullah became king on 7 February 1999. Hussein had recently named him Crown Prince on 24 January, replacing Hussein's brother Hassan who had served many years in the position. Abdullah is the namesake of King Abdullah I, his great-grandfather and founder of modern-day Jordan.[36]

Jordan's economy has improved greatly since Abdullah ascended to the throne in 1999. He has been credited with increasing foreign investment, improving public-private partnerships and providing the foundation for Aqaba's free-trade zone and Jordan's flourishing information and communication technology (ICT) sector. He also set up five other special economic zones: Irbid, Ajloun, Mafraq, Ma'an and the Dead Sea. As a result of these reforms, Jordan's economic growth has doubled to 6% annually under King Abdullah's rule compared to the latter half of the 1990s.[37] Foreign direct investment from the West as well as the countries of the Persian Gulf has continued to increase.[38] He also negotiated a free-trade agreement with the United States, which was the third free trade agreement for the U.S. and the first with an Arab country.[39]

During the suspension of Parliament between 2001 and 2003, the scope of King Abdullah II's power was demonstrated with the passing of 110 temporary laws. Two of these laws dealt with elections and were criticized as having the effect of reducing the power of Parliament.[40][41] In 2005, King Abdullah expressed his intentions of making Jordan a democratic country.[42] Thus far, however, democratic development has been limited, with the monarchy maintaining most power and its allies dominating parliament. Elections were held in November 2010.

In February 2011, responding to domestic and regional unrest, King Abdallah replaced his prime minister and formed a National Dialogue Commission with a reform mandate. The King told the new prime minister to "take quick, concrete and practical steps to launch a genuine political reform process", "to strengthen democracy," and provide Jordanians with the "dignified life they deserve."[43] The King called for an "immediate revision" of laws governing politics and public freedoms.[44] Initial reports say that this effort has started slowly and that several "fundamental rights" are not being addressed.[45]

Geography

Jordan lies on the continent of Asia between latitudes 29° and 34° N, and longitudes 35° and 40° E (a small area lies west of 35°). It consists of an arid plateau in the east, irrigated by oasis and seasonal water streams, with highland area in the west of arable land and Mediterranean evergreen forestry.

The Jordan Rift Valley of the Jordan River separates Jordan from Israel and the Palestinian Territories. The highest point in the country is Jabal Umm al Dami, at 1,854 m (6,083 ft) above sea level, its top is also covered with snow, while the lowest is the Dead Sea −420 m (−1,378 ft). Jordan is part of a region considered to be "the cradle of civilization", the Levant region of the Fertile Crescent.

Major cities include the capital Amman and Salt in the west, Irbid, Jerash and Zarqa, in the northwest and Madaba, Karak and Aqaba in the southwest. Major towns in the eastern part of the country are the oasis town of Azraq and Ruwaished.

Climate

The climate in Jordan is semi-dry in summer with average temperature in the mid 30 °C (86 °F) and is relatively cool in winter averaging around 13 °C (55 °F). The western part of the country receives greater precipitation during the winter season from November to March and snowfall in Amman (756 m (2,480 ft) ~ 1,280 m (4,199 ft) above sea-level) and Western Heights of 500 m (1,640 ft). Excluding the rift valley, the rest of the country is entirely above 300 m (984 ft) (SL).[46] The weather is humid from November to March and semi dry for the rest of the year. With hot, dry summers and cool winters during which practically all of the precipitation occurs, the country has a Mediterranean-style climate. In general, the farther inland from the Mediterranean a given part of the country lies, the greater are the seasonal contrasts in temperature and the less rainfall.

Politics and government

Although Jordan is a constitutional monarchy, the king holds wide executive and legislative powers. He serves as Head of State and Commander-in-Chief and appoints the executive branch consisting of the Prime Minister, the Cabinet of Jordan, and regional governors.[47][48] The current monarch is Abdullah II.

The Parliament of Jordan consists of two chambers: the House of Representatives (Majlis an-Nuwāb) and the Senate (Majlis al-'Aayan). The 150 members of the House are democratically elected from 12 constituencies, but 75 members of the Senate are all directly appointed by the King.[49] Women's quota in the house of representatives is 15 seats. 108 seats are chosen from constituencies while the remaining 27 seats are chosen through proportional representation on nationwide party lists.

King Abdullah II succeeded his father Hussein following the latter's death in February 1999. Abdullah moved quickly to reaffirm Jordan's peace treaty with Israel and its relations with the United States. During the first year in power, he refocused the government's agenda on economic reform.

Jordan has multi-party politics. Political parties contest fewer than a fifth of the seats; the remainder are assigned to independent politicians.[50] A new law enacted in July 2012 placed political parties under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Interior and forbade the establishment of parties based on religion.[51]

The last parliamentary elections were held on 23 January 2013. Because of a history of rigged elections, government critics have dismissed them as merely cosmetic. The Muslim Brotherhood and Hirak boycotted the vote.[52]

Law

The Jordanian legal system is derived from Sharia and an OttomanEgyptian form of the Napoleonic Code. It has also been influenced by tribal traditions.[53]

The highest court is the Court of Cassation, followed by the Courts of Appeal.[53] The lower courts are divided into civil courts and sharia courts. Civil courts have jurisdiction over criminal and civil cases, while the sharia courts have jurisdiction over personal status for Muslims, including marriage, divorce, and inheritance; parallel tribunals handle such matters for non-Muslims.[53] Shari’a courts also have jurisdiction over matters pertaining to the Islamic waqfs. In cases involving parties of different religions, regular courts have jurisdiction.[54]

The Constitution of Jordan was adopted on January 11, 1952 and has been amended many times. Article 97 of Jordan's constitution guarantees the independence of the judicial branch, clearly stating that judges are 'subject to no authority but that of the law.' While the king must approve the appointment and dismissal of judges, in practice these are supervised by the Higher Judicial Council. Article 99 of the Constitution divides the courts into three categories: civil, religious and special. The civil courts deal with civil and criminal matters in accordance with the law, and they have jurisdiction over all persons in all matters, civil and criminal, including cases brought against the government. The civil courts include Magistrate Courts, Courts of First Instance, Courts of Appeal, High Administrative Courts and the Supreme Court.

The Family Law in force is the Personal Status Law of 1976.[55] Sharia Courts have jurisdiction over personal status matters relating to Muslims.[56]

Jordan's law enforcement ranked 24th in the world, 4th in the Middle East, in terms of police services' reliability in the Global Competitiveness Report. Jordan also ranked 13th in the world and 3rd in the Middle East in terms of prevention of organized crime, making it one of the safest countries in the world.[57]

Foreign relations

Jordan has followed a pro-Western foreign policy and maintained close relations with the United States and the United Kingdom. These relations were damaged by Jordan's neutrality and maintaining relations with Iraq during the first Gulf War. Following the Gulf War, Jordan largely restored its relations with Western countries through its participation in the Southwest Asia peace process and enforcement of UN sanctions against Iraq. Relations between Jordan and the Persian Gulf countries improved substantially after King Hussein's death in 1999.

Jordan is a key ally of the USA and UK and, together with Egypt, is one of only two Arab nations to have signed peace treaties with Israel.[58][59]

In Israel in 2009, several Likud lawmakers proposed a bill that called for a Palestinian state on both sides of the Jordan River, presuming that Jordan should be the alternative homeland for the Palestinians. Later, following similar remarks by the Israeli Speaker of the Knesset, twenty Jordanian lawmakers proposed a bill in the Jordanian Parliament in which the peace treaty between Israel and Jordan would be frozen. The Israeli Foreign Ministry disavowed the original proposal.[60][61]

Military

The Jordanian military enjoys strong support and aid from the United States, the United Kingdom and France. This is due to its critical position between Israel, the West Bank, Syria, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia with very close proximity to Lebanon and Egypt. The development of the Special Operations Forces has been particularly significant, enhancing the capability of the forces to react rapidly to threats to state security, as well as training special forces from the region and beyond.[62][63]

There are about 50,000 Jordanian troops working with the United Nations in peacekeeping missions across the world. These soldiers provide everything from military defense, training of native police, medical help, and charity. Jordan ranks third internationally in taking part in UN peacekeeping missions.[64] Jordan has one of the highest levels of peacekeeping troop contributions of all U.N. member states.[65]

Jordan has dispatched several field hospitals to conflict zones and areas affected by natural disasters across the world such as Iraq, the West Bank, Lebanon, Afghanistan, Haiti, Indonesia, Congo, Liberia, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Sierra Leone and Pakistan. The Kingdom's field hospitals extended aid to more than one million people in Iraq, some one million in the West Bank and 55,000 in Lebanon. According to the military, there are Jordanian peacekeeping forces in Asia, Africa, Europe and Latin America. Jordanian Armed Forces field hospital in Afghanistan has since 2002 provided assistance to some 750,000 persons and has significantly reduced the suffering of people residing in areas where the hospital operates.In some missions, the number of Jordanian troops was the second largest, the sources said.[66] Jordan also provides extensive training of security forces in Iraq,[67] the Palestinian territories,[68] and the GCC.[69]

Administrative divisions

Jordan is divided into 12 provinces known as governorates, which, in turn, are subdivided into 54 departments or districts called nawahi.

| No. | Governorate | Capital | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| 1 | Irbid | Irbid | |

| 2 | Ajloun | Ajloun | |

| 3 | Jerash | Jerash | |

| 4 | Mafraq | Mafraq | |

| 5 | Balqa | Salt | |

| 6 | Amman | Amman | |

| 7 | Zarqa | Zarqa | |

| 8 | Madaba | Madaba | |

| 9 | Karak | Al Karak | |

| 10 | Tafilah | Tafilah | |

| 11 | Ma'an | Ma'an | |

| 12 | Aqaba | Aqaba |

Human rights

The 2010 Arab Democracy Index from the Arab Reform Initiative ranked Jordan first in the state of democratic reforms out of fifteen Arab countries.[70]

Civil liberties and political rights scored 5 and 6 respectively in Freedom House's Freedom in the World 2011 report, where 1 is most free and 7 is least free. This earned Jordan "Not Free" status.[71] Jordan ranked ahead of 6, behind 4, and the same as 8 countries in the Middle East and North Africa region.

Jordan ranked 6th among the 19 countries in the Middle East and North Africa region, and 50th out of 178 countries worldwide in the 2010 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) issued by Transparency International.[72] Jordan's 2010 CPI score was 4.7 on a scale from 0 (highly corrupt) to 10 (very clean). Jordan ratified the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) in February 2005[73] and has been a regional leader in spearheading efforts to promote the UNCAC and its implementation.[57]

According to a 2010 Pew Global Attitudes survey, 86% of Jordanians polled supported the death penalty for those who leave Islam; 58% supported whippings and cutting off of hands for theft and robbery; and 70% support stoning people who commit adultery.[74]

Economy

Jordan is classified by the World Bank as a country of "upper-middle income".[11] The economy has grown at an average rate of 4.3% per annum since 2005.[75] Approximately 13% of the population lives on less than US$ 3 a day.[75]

The GDP per capita rose by 351% in the 1970s, declined 30% in the 1980s, and rose 36% in the 1990s.[76][failed verification] Jordan has a free trade agreement with Turkey.[77] Jordan also enjoys advanced status with the EU.[78]

The Jordanian economy is based by insufficient supplies of water, oil and other natural resources.[3] Other challenges include high budget deficit, high outstanding public debt, high levels of poverty and unemployment.[75] Unemployment in 2012 is nominally around 13%, but is thought by many analysts to be as high as a quarter of the working-age population.[79] Youth unemployment is nearly 30%.[79] Jordan has few natural resources and a small industrial base.[79] Corruption is particularly pronounced and the use of wasta widespread.[79] Jordan also suffers from a brain drain of its most talented workers.[79] Remittances from Jordanian expatriates are a major source of foreign exchange.[80]

Due to slow domestic growth, high energy and food subsidies and a bloated public-sector workforce, Jordan usually runs annual budget deficits. These are partially offset by international aid.[79]

Jordan’s economy is relatively well diversified.[80] Trade and finance combined account for nearly one-third of GDP; transportation and communication, public utilities, and construction account for one-fifth, and mining and manufacturing constitute nearly that proportion.[80] Despite plans to increase the private sector, the state remains the dominant force in Jordan’s economy.[80] The government employs between one-third and two-thirds of all workers.[79]

In 2000, Jordan joined the World Trade Organization and signed the Jordan–United States Free Trade Agreement; in 2001, it signed an association agreement with the European Union.[81]

Net official development assistance to Jordan in 2009 totalled USD 761 million; according to the government, approximately two-thirds of this was allocated as grants, of which half was direct budget support.[75]

The Great Recession and the turmoil caused by the Arab Spring have depressed Jordan's GDP growth, impacting export-oriented sectors, construction, and tourism.[3] Tourist arrivals have dropped sharply since 2011, hitting an important source of revenue and employment.[82]

In an attempt to quell popular discontent, the government promised in 2011 to keep energy and food prices artificially low while raising wages and pensions in the public sector.[82] Jordan's finances have also been strained by a series of natural gas pipeline attacks in Egypt, causing it to substitute more expensive heavy-fuel oils to generate electricity.[3] $500 million was required to cover the resulting fuel shortage.[82]

In August 2012, the International Monetary Fund agreed to give Jordan a three-year $2-billion loan. As part of the deal, Jordan was expected to cut spending.[79] In November 2012, the government cut subsidies on fuel,[83] increasing its price. As a result, large scale protests broke out across the country and the increase was removed.[79]

Jordan's total foreign debt in 2012 was $22 billion, representing 72% of its GDP. Roughly two-thirds of this total had been raised on the domestic market, with the remaining owed to overseas lenders.[83] In late November 2012, the budgetary shortfall was estimated at around $3 billion, or about 11% of GDP.[83] Growth was expected to reach 3% by the end of 2012 and the IMF predicts GDP will increase by 3.5% in 2013, rising to 4.5% by 2017.[83] The inflation rate was forecast at 4.5% by the end of 2012.[83]

The official currency in Jordan is the Jordanian dinar, which is pegged to the IMF's special drawing rights (SDRs), equivalent to an exchange rate of 1 US$ ≡ 0.709 dinar, or approximately 1 dinar ≡ 1.41044 dollars.[84]

The proportion of skilled workers in Jordan is among the highest in the region. Agriculture in Jordan constituted almost 40% of GNP in the early 1950s; on the eve of the Six-Day War in June 1967, it was 17%.[85] By the mid-1980s, the agricultural share of Jordan's GNP was only about 6%.[85] Jordan has hosted the World Economic Forum on the Middle East and North Africa six times and plans to hold it for the seventh time in 2013 at the Dead Sea.[86]

Natural resources

Phosphate mines in the south have made Jordan one of the largest producers and exporters of this mineral in the world.[87][88][89][90][91] Phosphates were first discovered by Amin Kamel Kawar in 1935 at the site in Russeifa.[92][dubious – discuss]

Four nuclear power plants are planned, with the first due to start delivering electricity in 2019.[93] Jordan has been seeking US approval for the production of nuclear fuel from its uranium since 2010. According to Ha'aretz, the US position on the matter is the same as that of Israel and it has rejected Jordan's request.[94]

Natural gas was discovered in Jordan in 1987. The estimated size of the reserve discovered was about 230 billion cubic feet, a modest quantity compared with its other Arabian neighbours. The Risha field, in the Eastern Desert beside the Iraqi border, produces nearly 30 million cubic feet of gas a day, which is sent to a nearby power plant to produce nearly 10% of Jordan's electricity needs.[95]

Despite the fact that reserves of crude oil are non-commercial, Jordan possesses one of the world's richest stockpiles of oil shale where there are huge quantities that could be commercially exploited in the central and northern regions west of the country. This shale oil sits under 60% of Jordan’s surface.[96] The moisture content and ash within is relatively low. And the total thermal value is 7.5 megajoules/kg, and the content of ointments reach 9% of the weight of the organic content.[97] A switch to power plants operated by oil shale has the potential to reduce Jordan's energy bill by at least 40–50 per cent, according to the National Electric Power Company.[98]

Tourism

Tourism accounted for 10%–12% of the country's Gross National Product in 2006. In 2010, there were 8 million visitors to Jordan. The result was $3.4 billion in tourism revenues, $4.4 billion if medical tourists are included.[99] Jordan offers everything from world-class historical and cultural sites like Petra and Jerash to modern entertainment in urban areas most notably Amman. Moreover, seaside recreation is present in Aqaba and Dead Sea through numerous international resorts. Eco-tourists have numerous nature reserves to choose from as like Dana Nature Reserve. Religious tourists visit Mt. Nebo, the Baptist Site, and the mosaic city of Madaba.

Jordan has nightclubs, discothèques and bars in Amman, Irbid, Aqaba, and many 4 and 5-star hotels. Furthermore, beach clubs are also offered at the Dead Sea and Aqaba. Jordan played host to the Petra Prana Festival in 2007 which celebrated Petra's win as one of the New Seven Wonders of the World with world-renowned DJs like Tiesto and Sarah Main. The annual Distant Heat festival in Wadi Rum and Aqaba ranked as one of the world's top 10 raves.

Nature reserves in Jordan include the Dana Biosphere Reserve, Azraq Wetland Reserve, Shaumari Wildlife Reserve and Mujib Nature Reserve.

Medical tourism

Jordan has been a medical tourism destination in the Middle East since the 1970s. A study conducted by Jordan's Private Hospitals Association (PHA) found that 250,000 patients from 102 countries received treatment in the kingdom in 2010, compared to 190,000 in 2007, bringing over $1 billion in revenue. It is the region's top medical tourism destination as rated by the World Bank and fifth in the world overall.[100][101][102]

It is estimated that Jordan received 50,000 Libyan patients and 80,000 Syrian refugees, who also sought treatment in Jordanian hospitals, in the first six months of 2012.[103]

Jordan's main focus of attention in its marketing effort are the ex-Soviet states, Europe, and America.[104] Most common medical procedures on Arab and foreign patients included organ transplants, open heart surgeries, infertility treatment, laser vision corrections, bone operations and cancer treatment.[105]

Transportation

As it is a transit country for goods and services to the Palestinian territories and Iraq, Jordan maintains a well-developed transportation infrastructure. Jordan ranked as having the 35th best infrastructure in the world, one of the highest rankings in the developing world, according to the World Economic Forum's Index of Economic Competitiveness.[106]

In 2006, the Port of Aqaba was ranked as having the "Best Container Terminal" in the Middle East by Lloyd's List.[107]

Jordan has three commercial airports, all receiving and dispatching international flights. Two are in Amman and the third is in Aqaba. The largest airport in the country, serving as the hub of the flag carrier Royal Jordanian, is Queen Alia International Airport in Amman. The airport is currently[when?] under significant expansion in a bid to make it the hub for the Levant. Amman Civil Airport was the country's main airport before it was replaced by Queen Alia Airport but it still serves several regional routes. King Hussein International Airport serves Aqaba with connections to Amman and several regional and international cities.

Demographics

Transjordan had a population of 200,000 in 1920, 225,000 in 1922 and 400,000 in 1948.[108] Almost half of the population in 1922 (around 103,00) was nomadic.[108]

Jordan had two towns with more than 10,000 inhabitants in 1946: Amman (65,754) and Salt (14,479).[108] Following the influx of Palestinian refugees, Amman's population increased to 108,412 by 1952, and both Irbid and Zarqa more than doubled their population from less than 10,000 each to more than, respectively, 23,000 and 28,000.[108]

The Jordanian Department of Statistics estimated the 2011 population at 6,249,000.[109] In 2009, the population of Jordan was slightly over 6,300,000.[3] There were 946,000 households in Jordan in 2004, with an average of 5.3 persons/household (compared to 6 persons/household for the census of 1994).[110]

A study published by Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza found that the Jordanian genetics are closest to the Assyrians among all other nations of Western Asia.[111]

Immigrants and refugees

In 2007, there were 700,000–1,000,000 Iraqis in Jordan.[112] Since the Iraq War, many Christians (Assyrians/Chaldeans) from Iraq have settled permanently or temporarily in Jordan. They could number as many as 500,000.[113][dead link] There were also 15,000 Lebanese who emigrated to Jordan following the 2006 War with Israel.[114] To escape the violence, over 500,000 Syrian refugees have fled to Jordan since 2012.[115]

The vast majority of Jordanians are Arabs, accounting for 95-97% of the population. Assyrian Christians account for up to 150,000 persons, or 0.8% of the population. Most are Eastern Aramaic speaking refugees from Iraq.[116] Kurds, number some 30,000 people, and like the Assyrians, many are refugees from Iraq, Iran and Turkey.[117] Armenians number approximately 5,000 persons, mainly residing in Amman.[118] A small number of ethnic Mandeans also reside in Jordan, again mainly refugees from Iraq. Jews, once prevalent in Jordan, now number only 300 or so people in Tzofar.

There are around 1.2 million illegal and some 500,000 legal migrant workers in the Kingdom.[119] Furthermore, there are thousands of foreign women working in nightclubs, hotels and bars across the kingdom, mostly from Eastern Europe and North Africa.[120][121][122]

Jordan is home to a relatively large American and European expatriate population concentrated mainly in the capital as the city is home to many international organizations and diplomatic missions that base their regional operations in Amman.[3][123]

According to UNRWA, Jordan was home to 1,951,603 Palestinian refugees in 2008, most of them Jordanian citizens.[124] 338,000 of them were living in UNRWA refugee camps.[125] Jordan revoked the citizenship of thousands of Palestinians to thwart any attempt to resettle West Bank residents in Jordan. West Bank Palestinians with family in Jordan or Jordanian citizenship were issued yellow cards guaranteeing them all the rights of Jordanian citizenship. Palestinians living in Jordan with family in the West Bank were also issued yellow cards. All other Palestinians wishing such Jordanian papers were issued green cards to facilitate travel into Jordan.In general, however, population of Palestinian origin constitutes about 67 percent of the Kingdom's population.[126]

Languages

The official language is Modern Standard Arabic, a literary language taught in the schools. The native languages of most Jordanians are dialects of Jordanian Arabic, a nonstandard version of Arabic with many influences from English, French and Turkish. Jordanian Sign Language is the language of the deaf community.

English, though without an official status, is widely spoken throughout the country and is the de facto language of commerce and banking, as well as a co-official status in the education sector; almost all university-level classes are held in English.

Russian, Circassian, Armenian, Tagalog, Tamil, and Chechen are quite popular among their communities and acknowledged widely in the kingdom.

Most, if not all, public schools in the country teach the English and Standard Arabic.[citation needed] French is elective in many schools, mainly in the private sector. L'Ecole française d'Amman and Lycée français d'Amman are the most famous French language schools in the capital. French remains an elite language in Jordan, despite not enjoying the popularity it did in older times.

German is an increasingly popular language among the elite and the educated; it's been most likely introduced at a larger scale after the début of the Deutsche Universität, or as officially named, the German-Jordanian University. A historic society of German Protestants of Amman continue to use the German language in their events and daily lives.[127]

The media in Jordan revolves mainly around English, with many British and mostly American programmes and films shown on local television and cinemas. Egyptian Arabic is very popular, with many Egyptian movies playing in cinemas across the country.

The government-owned Jordan TV shows programmes and newscasts in Arabic (Standard and Jordanian), English and French; Radio Jordan offers radio services in Standard Arabic, the Jordanian dialects (informally), English and French, as well. When an English-language film is shown in a cinema, translatations into both French and Standard Arabic are available.

Religion

Islam is the official religion and approximately 92% of the population is Muslim. Sunnis form the majority with non-denominational Muslims being the second largest group of Muslims at 29%.[129]

Jordan has laws promoting religious freedom, but they fall short of protecting all minority groups. Muslims who convert to another religion as well as missionaries face societal and legal discrimination.[130]

According to the Legatum Prosperity Index, 46.2% of Jordanians regularly attend religious services in 2006.[131]

Jordan has an indigenous Christian minority. Christians made up 30% of the Jordanian population in 1950.[132]

Other religious minorities groups in Jordan include adherents to the Druze and Bahá'í Faith. The Druze are mainly located in the eastern oasis town of Azraq, some villages on the Syrian border and the city of Zarqa, while the village Adassiyeh bordering the Jordan Valley is home to Jordan's Bahá'í community.

Culture

FIFA Vice President.

Although religion and tradition play an important part in modern-day Jordanian society, Jordanians live in a relatively secular society that is increasingly grappling with the effects of globalization. Jordan is considered one of the Arab World's most cosmopolitan countries.[134] 67% of Jordanian youth identify themselves as liberals, second highest in the Arab World after Lebanon.[135]

According to the Center for Strategic Studies, 52% of Jordanians support a secular state in which religious practices were considered to be “private matters that must be differentiated from social and political life", 6% express indifference towards a secular state or a more religious one, while 42% prefer more religious involvement in social and political life.[136]

Arts

Art in Jordan is represented through many Institutions with the aim to increase the cultural awareness in plastic and visual arts and to represent the artistic movement in Jordan and it’s wide spectrum of creativity in various fields such as paintings, sculpture, video art, photography, graphic arts, ceramics and installations.

The Jordan National Gallery of Fine Arts is a major contemporary art museum located in Amman, Jordan.

Popular culture

Jordan imports the overwhelming majority of its music, cinema, and other forms of entertainment from other countries most specifically other Arab countries like Lebanon and Egypt as well as the West, primarily the United States. However, there has been a rise of home-grown songs, music, art, movies and television, although they still pale in comparison to the amount imported from abroad. Music in Jordan is now developing by a lot of new musicians and artist, who are now popular in the Middle East such as singer and composer Toni Qattan and singer Hani Metwasi who changed the old notion about the music of Jordan which was unpopular for many years.

Media

Jordan ranked 141 out of 196 countries worldwide, earning "Not Free" status in Freedom House's 2011 Freedom of the Press 2011 report.[137] Jordan had the 5th freest press of 19 countries in the Middle East and North Africa region. In the 2010 Press Freedom Index maintained by Reporters Without Borders, Jordan ranked 120th out of 178 countries listed, 5th out of the 20 countries in the Middle East and North Africa region. Jordan's score was 37 on a scale from 0 (most free) to 105 (least free).[138]

Health

Jordan prides itself on its health service, one of the best in the region.[139] Government figures have put total health spending in 2002 at some 7.5% of Gross domestic product (GDP), while international health organizations place the figure even higher, at approximately 9.3% of GDP. The CIA World Factbook estimates life expectancy in Jordan is 80.18 years, the second highest in the region after Israel.[140] The WHO gives a considerably lower figure however, at 73.0 years for 2011.[141] There were 203 physicians per 100,000 people in the years 2000–2004.[142]

The country's health care system is divided between public and private institutions. In the public sector, the Ministry of Health operates 1,245 primary health-care centers and 27 hospitals, accounting for 37% of all hospital beds in the country; the military's Royal Medical Services runs 11 hospitals, providing 24% of all beds; and the Jordan University Hospital accounts for 3% of total beds in the country. The private sector provides 36% of all hospital beds, distributed among 56 hospitals. On 1 June 2007, Jordan Hospital (as the biggest private hospital) was the first general specialty hospital to gain the international accreditation JCAHO.[143] The King Hussein Cancer Center is a leading cancer treatment center.

70% of the population has medical insurance.[144] Childhood immunization rates have increased steadily over the past 15 years; by 2002 immunizations and vaccines reached more than 95% of children under five.[143]

Water and sanitation, available to only 10% of the population in 1950, now reach 99% of Jordanians, according to government statistics.[145]

Education

The adult literacy rate in 2013 was 97%.[146] The Jordanian educational system consists of a two-year cycle of pre-school education, ten years of compulsory basic education, and two years of secondary academic or vocational education, after which the students sit for the Tawjihi.[147] UNESCO ranked Jordan's education system 18th out of 94 nations for providing gender equality in education.[148] 20.5% of Jordan's total government expenditures goes to education compared to 2.5% in Turkey and 3.86% in Syria.[149][150][151] Secondary school enrollment has increased from 63% to 97% of high school aged students in Jordan and between 79% and 85% of high school students in Jordan move on to higher education.[152]

There are 2,000 researchers per million people, compared to 5,000 researchers per million for the highest-performing countries.[153] According to the Global Innovation Index 2011, Jordan is the third-most innovative economy in the Middle East, behind Qatar and the United Arab Emirates.[154]

Jordan has 10 public universities, 16 private universities and 54 community colleges, of which 14 are public, 24 private and others affiliated with the Jordanian Armed Forces, the Civil Defence Department, the Ministry of Health and UNRWA.[155] There are over 200,000 Jordanian students enrolled in universities each year. An additional 20,000 Jordanians pursue higher education abroad primarily in the United States and Great Britain.[156] Jordan is already home to several international universities such as German-Jordanian University, Columbia University, NYIT, DePaul University and the American University of Madaba. George Washington University is planning to establish a medical university in Jordan.[157]

According to the Webometrics Ranking of World Universities, the top-ranking universities in the country are the University of Jordan (1,507th worldwide), Yarmouk University (2,165th) and the Jordan University of Science & Technology (2,335th).[158]

Internet-wise, Jordan contributes more content than any other Arab country: 75% of all Arabic online content.[159]

See also

References

- ^ "Ethnologue report for Jordan". Ethnologue.com. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ "Government". kinghussein.gov.jo. Retrieved 15 July 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "CIA – The World Fact book – Jordan". cia.gov. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- ^ a b "Jordan". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- ^ "Gini index". World Bank. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2010" (PDF). United Nations. 2010. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- ^ "Jordan Time Zone". Jordan News Agency. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ a b Howard Sachar, A History of Israel: From the Rise of Zionism to Our Time, Random House LLC, 31 July 2013.

- ^ "Regional and National Trends in the Human Development Index 1980–2011". United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ^ "Country Rankings: World & Global Economy Rankings on Economic Freedom". Heritage.org. 31 October 2012. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ a b "Country and Lending Groups". Data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ "Jordan obtains 'advanced status' with EU". Jordan Times. 27 October 2010. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ "League of Arab States". Arableagueonline.org. Retrieved 15 June 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "Edom". BiblePlaces.com. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ Rare Middle Eastern Snow - December 17, 201

- ^ ^ Jump up to: a b [1], http://www.omniglot.com/writing/nabataean.htm.

- ^ ^ Basalt, 1st century AD. Found in Sia in the Hauran, Southern Syria.

- ^ "Jordan – History – The Ottoman Empire". The Royal Hashemite Court. Retrieved 9 November 2009.

- ^ T. E. Lawrence (1922). Seven Pillars of Wisdom. United Kingdom.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ League of Nations Official Journal, Nov. 1922, pp. 1188–1189, 1390–1391.

- ^ Marjorie M. Whiteman, Digest of International Law, vol. 1, U.S. State Department (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1963) pp 650–652

- ^ a b c Kamal S. Salibi (15 December 1998). The Modern History of Jordan. I.B.Tauris. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-86064-331-6. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ^ Muhammad Khalil (1962). The Arab States and the Arab League: a Documentary Record. Beirut: Khayats. pp. 53–54. translating the Official Gazette, No. 984.

- ^ Naseer Hasan Aruri (1972). Jordan: a study in political development (1921–1965). Springer. p. 90. ISBN 978-90-247-1217-5. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

For Abdullah, the annexation of Palestine was the first step in the implementation of his Greater Syria Plan. His expansionist policy placed him at odds with Egypt and Saudi Arabic. Syria and Lebanon, which would be included in the Plan were uneasy. The annexation of Palestine was, therefore, condemned by the Arab League's Political Committee on May 15, 1950.

- ^ American Jewish Committee; Jewish Publication Society of America (1951). American Jewish year book. American Jewish Committee. pp. 405–6. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

On April 13, 1950, the council of the League resolved that "Jordan's annexation of Arab Palestine was illegal", and at a meeting of the League's political committee on May 15, 1950, Saudi Arabia, Lebanon and Syria joined Egypt in demanding Jordan's expulsion from the Arab League.

- ^ Council for Middle Eastern Affairs (1950). Middle Eastern affairs. Council for Middle Eastern Affairs. p. 206. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

May 12: Jordan's Foreign Minister walks out of the Political Committee during the discussion of Jordan's annexation of Arab Palestine. May 15: The Political Committee agrees that Jordan's annexation of Arab Palestine was illegal and violated the Arab League resolution of Apr. 12, 1948. A meeting is called for June 12 to decide whether to expel Jordan or take punitive action against her.

- ^ Naseer Hasan Aruri (1972). Jordan: a study in political development (1921–1965). Springer. p. 90. ISBN 978-90-247-1217-5. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

The annexation of Palestine was, therefore, condemned by the Arab League's Political Committee on May 15, 1950. A motion to expel Jordan from the League was prevented by the dissenting votes of Yemen and Iraq

- ^ Martin Sicker (2001). The Middle East in the Twentieth Century. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-275-96893-9. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- ^ Hasan Afif El-Hasan (15 September 2010). Israel Or Palestine? Is the Two-state Solution Already Dead?: A Political and Military History of the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict. Algora Publishing. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-87586-793-9. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- ^ Martin Gilbert (12 September 1996). Jerusalem in the Twentieth Century. J. Wiley & Sons. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-471-16308-4. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ "Jordan asked Nixon to attack Syria, declassified papers show". CNN. 28 November 2007. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

- ^ "Black September". History Central. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ^ "القيادة العامة الفلسطينية كما يراها أحمد جبريل ح8" (in Arabic). Aljazeera.net. 23 May 2004. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ^ "An Interview with Yasser Arafat, Volume 34, Number 10, 11 June 1987". New York Review of Books. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ^ "» Renouncing claims to the West Bank". Britannica.com. 15 June 1978. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ^ "Profile". King Abdullah II Official Website. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ "Jordan—Concluding Statement for the 2006 Article IV Consultation and Fourth Post-Program Monitoring Discussions". International Monetary Fund. 28 November 2006. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ^ "Trade and Investment". Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation. 11 September 2006. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ^ "Overview: U.S.-Jordan Free Trade Agreement". White House Office of the Press Secretary. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ^ Parker, C. (Spring Summer 2002). "Transformation without transition: electoral politics, network ties, and the persistence of the shadow state in Jordan". Elections in the Middle East: what do they mean. Cairo Papers in Social Sciences. 25 (½). Cairo: 148.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Better Governance for Development in the Middle East and North Africa: Enhancing Inclusiveness and Accountability" (PDF). World Bank. 2003. p. 44.

- ^ "Jordan edging towards democracy". BBC News. 27 January 2005. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ^ Derhally, Massoud A (1 February 2011). "Jordan's King Abdullah Replaces Prime Minister". Bloomberg. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- ^ "Jordan's king fires Cabinet amid protests". Apnews.myway.com. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- ^ Christoph Wilcke (8 March 2011). "Jordan: A Measure of Reform". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ^ "Weather - Jordan". BBC. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ^ "Jordan". Freedom in the World 2013. Freedom House. Retrieved 16 December 2013.

- ^ "Democracy index 2012: Democracy at a standstill". Economist Intelligence Unit. 14 March 2013. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ^ "Q&A: Jordan election". BBC News. 22 January 2013.

- ^ "As beleaguered as ever". The Economist. 13 October 2012.

- ^ "Countries at the Crossroads: Jordan". Freedom House. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- ^ "As Elections Near, Protesters in Jordan Increasingly Turn Anger Toward the King". The New York Times. 21 January 2013.

- ^ a b c Husseini, Rana. "Jordan" (PDF). Women’s Rights in the Middle East and North Africa: Progress Amid Resistance. Freedom House. p. 3. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- ^ Business Optimization Consultants B.O.C. "Jordan – Government – The Judicial Branch". Kinghussein.gov.jo. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "Women In Personal Status Laws: Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, Syria" (PDF). UNESCO. July 2005. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ^ "Jordan, Hashemite Kingdom of". Law.emory.edu. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ^ a b "Security & Political Stability". Jordaninvestment.com. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "Peace first, normalcy with Israel later: Egypt". Al Arabiya News Channel. 17 August 2009. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- ^ "Mideast peace drive gets two-prong boost". Hurriyet Daily News and Economic Review. 18 August 2009. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- ^ "Jordanian lawmakers demand freeze of peace pact with Israel". Monsters and Critics. 29 July 2009. Retrieved 23 March 2010.

- ^ Azoulay, Yuval. "Israel disavows MK's proposal to turn West Bank over to Jordan". Ha'aretz. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "Jordan Says It Trained 2,500 Afghan Special Forces". Globalresearch.ca. 13 May 2010. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ "AFP: Jordan trained 2,500 Afghan special forces: minister". Google. 12 May 2010. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ "Bakhit highlighted that Jordan ranks third internationally in taking part in UN peacekeeping missions". Zawya.com. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ "Hong kong, jordan, and estonia debut among the top 10 in expanded ranking of the world's most globalized countries". Atkearney.com. 22 October 2007. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "Jordanian peacekeepers earn country good reputation". Jordanembassyus.org. 26 September 2007. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "Special Operations: Jordanians Train Iraqi Commandoes". Strategypage.com. 14 May 2006. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "Jordan ready to train Palestinians — King". Retrieved 31 December 2012.

- ^ "Jordan Trains GCC States". MiddleEastNewsline. 19 August 2009. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "Report Card on Democratic Reforms in Arab World Issued". Voice of America (VOANews.com). 29 March 2010. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "Freedon in the World: Country Report for Jordan". Freedom House. 13 January 2011. Retrieved 20 May 2011.

- ^ "Corruption Perceptions Index 2010 Results". Transparency International. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ^ "Signatories to the United Nations Convention against Corruption". United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 1 May 2011. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ^ "Muslim Publics Divided on Hamas and Hezbollah". Pew Global Attitudes Project. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Jordan" (PDF). OECD.

- ^ "GDP per capita". Wayback.archive.org. 13 February 2010. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- ^ "Jordan and Turkey strengthening historical bonds". Zawya. 28 October 2010. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- ^ "Jordan obtains 'advanced status' with EU". Jordan Times. Archived from the original on 20 February 2011. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Sharp, Jeremy M. (3 October 2012). "Jordan: Background and US Relations" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. pp. 7–8.

- ^ a b c d "Jordan : Demographic trends". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- ^ "Jordan Economy". Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- ^ a b c "Harsh blow to Jordanian economy". FT.com. 28 June 2011.

- ^ a b c d e "Jordan: Year in Review 2012". Oxford Business Group. 20 December 2012.

- ^ "Exchange Rate Fluctuations". Programme Management Unit. Archived from the original on 19 July 2004.

- ^ a b Chapin Metz, Helen (1989). "Jordan: A Country Study:Agriculture". Library of Congress, Washington D.C. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- ^ "Jordan to host World Economic Forum in 2013". The Jordan Times. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ "Jordan Phosphate Mines Co". Jordanphosphate.com. Archived from the original on 19 May 2008. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "Jordan Phosphate – Aqaba". Sulphuric-acid.com. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ Azhar, Muhammad (22 September 2000). "Phosphate Exports By Jordan". Arab Studies Quarterly and HighBeam Research.

- ^ "Embassy of Jordan (Washington, D.C.)". Jordanembassyus.org. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "Jordan – Natural Resources". Countrystudies.us. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ Amin K. Kawar Biography

- ^ "Jordan to produce Uranium by 2013, says minister". Jordan News Agency. 21 September 2011. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ Bar, Zvi (7 July 2010). "Who's Afraid of the Jordanian Atom?". Ha'aretz. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ^ "Jordan". Mafhoum.com. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ^ "The economy: The haves and the have-nots". Economist.com. 13 July 2013. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ^ Arab Petroleum Research Center, 2003, Jordan, in Arab oil & gas directory 2003: Paris, France, Arab Petroleum Research Center, pp. 191–206.

- ^ "Oil shale ventures to create thousands of jobs". The Jordan Times. 30 August 2009. Archived from the original on 26 March 2012. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "Periodical Islamic Chamber Of Commerce & Industry Magazine". Chambermag.com. Archived from the original on 28 October 2012. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ Health Tourism Destinations says: (19 April 2009). "Jordan: Top Medical Tourism Destination in the Arab World". medicaltourismguide.com. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Associated, The. "Jordan launches medical tourism advertising campaign in U.S." Ha'aretz. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "Medical Tourism Jordan – Jordan Health Travel – Jordan Medical Tourism". Medicaltourismco.com. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "Libyan Fighters Recuperating In Jordan". PRI's The World. 2 March 2012. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ "Jordan pushes medical tourism industry". AMEinfo.com. Archived from the original on 18 January 2010. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "Kingdom's medical tourism sector cracks global top five". Jordanembassyus.org. 20 February 2011. Retrieved 26 July 2012.[dead link]

- ^ "The Global Competitiveness Report 2010–2011" (PDF). World Economic Forum. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- ^ ASC Staff (31 October 2006). "Top 10 Middle East Ports". ArabianSupplyChain.com. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Jordan's State Building and the Palestinian Problem". Jordanembassy.org.au. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ "Population of the Kingdom by Sex According to the 1952, 1961, 1979 and 1994 Censuses, and Estimated Population for Some Selected Years (In 000)" (PDF). Department of Statistics- Jordan.

- ^ "النتائج الاولية للتعداد". Dos.gov.jo. Archived from the original on 12 January 2007. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza; Paolo Menozzi; Alberto Piazza (1994). The History and Geography of Human Genes. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-08750-4.

- ^ Leyne, Jon (24 January 2007). "Doors closing on fleeing Iraqis". BBC News. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ^ Mark Pattison (29 September 2010). "Iraqi refugees in Jordan are 'guests' with few privileges". Catholic Courier. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ^ "15,000 Lebanese in Jordan following conflict – Bakhit". Jordanembassyus.org. 4 August 2006. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ Syria Regional Refugee Response - Jordan. UNHCR.

- ^ ^ Jordan Should Legally Recognize Displaced Iraqis As Refugees, AINA.org. Assyrian and Chaldean Christians Flee Iraq to Neighboring Jordan, ASSIST News Service

- ^ ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Language and Cultural Shift Among the Kurds of Jordan". Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- ^ ^ Ethnologue 14 report for language code:ARM

- ^ "Jordan faces challenge of meeting migrants' health demands –– study". The Jordan Times. 28 August 2012. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ Nadim Zaqqa (2006). Economic Development and Export of Human Capital - a Contradiction?. Kassel University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-3-89958-205-5. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ^ Author: Rola Abimourched Published: 26 November 2010 (26 November 2010). "The conditions of domestic workers in the Middle East". WoMen Dialogue. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "3% of Nightclub women are Jordanian". Ammonnews. 19 January 2011. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ "People of Jordan". State.gov. 19 January 2010. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "UNRWA Statistics". United Nations. Archived from the original on 13 July 2008. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "UNRWA". UNRWA. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ "Amman revoking Palestinians' citizenship". Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011.

- ^ "German Protestant Community Center Amman" (PDF). Deutsche Botschaft Amman - Jordanien. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ^ [1]. CIA World Factbook. 2014.

- ^ Chapter 1: Religious Affiliation retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ^ Meral, Ziya (2008). No Place to Call Home. Surrey, UK: Christian Solidarity Worldwide.

- ^ "Variables – Attended a place of worship in past week? (% yes)". Legatum Institute.

- ^ Fleishman, Jeffrey (10 May 2009). "For Christian enclave in Jordan, tribal lands are sacred". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 10 May 2009.

- ^ Business Optimization Consultants B.O.C. "Jordan – Jordanian Cuisine". Kinghussein.gov.jo. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "Westernized media in Jordan breaking old taboos – RT". rt.com. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ "Third Annual ASDA'A Burson-Marsteller Arab Youth Survey" (PDF). ASDA’A Burson-Marsteller. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- ^ "How Jordan's Islamists Came to Dominate Society: An Evolution". Al-Monitor. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ "Freedom of the Press 2011-Regional Tables" (PDF). Freedom House. 2 May 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 May 2011. Retrieved 20 May 2011.

- ^ "Press Freedom Index 2010". Reporters Without Borders. 28 October 2010. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ^ "BBC News - Jordan profile - Overview". bbc.co.uk. 18 November 2012. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ "Life Expectancy ranks". CIA World Factbook. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ^ "Country statistical profiles" (PDF). WHO. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2007/2008" (PDF). Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- ^ a b "Jordan country profile" (PDF). Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ^ "People & Talent". Jordaninvestment.com. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ Business Optimization Consultants B.O.C. "Jordan – Human Resources – A Healthy Population". Kinghussein.gov.jo. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "National adult literacy rates (15+), youth literacy rates (15-24) and elderly literacy rates (65+)". UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- ^ "USAID/ Jordan- Education". Jordan.usaid.gov. 12 June 2006. Archived from the original on 25 April 2006. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "Education system in Jordan scoring well". Global Arab Network. 21 October 2009. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "Time Series > Education > Public spending on education, total > % of GDP > Syria". NationMaster. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "Emerging Markets Economic Briefings". Oxfordbusinessgroup.com. Retrieved 15 June 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "People & Talent". Jordaninvestment.com. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "Education Reform for the Knowledge Economy II" (PDF). World Bank. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- ^ Nature (2 November 2006). ": Islam and Science: The data gap : Article". Nature. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ [2][dead link]

- ^ "Jordan raises admission scores for private universities". AMEinfo.com. Archived from the original on 1 March 2010. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "ICT". Jordaninvestment.com. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "George Washington University to establish Medical University in Jordan". Edarabia.com. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ "Jordan". Ranking Web of Universities. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ "75% of online Arabic content originates in Jordan". Jordanembassyus.org. 7 June 2011. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

Further reading

- El-Anis, Imad. Jordan and the United States: The Political Economy of Trade and Economic Reform in the Middle East (I.B. Tauris, distributed by Palgrave Macmillan; 2011) 320 pages; case studies of trade in textiles, pharmaceuticals, and financial services.

- Goichon, Amélie-Marie. Jordanie réelle. Paris: Desclée de Brouwer (1967-1972). 2 vol., ill.

- Robins, Philip. A History of Jordan (2004).

- Ryan, Curt. "Jordan in Transition: From Hussein to Abdullah" (2002).

- Salibi, Kamal S. The Modern History of Jordan (1998).

- Teller, Matthew. The Rough Guide to Jordan (4th ed., 2009).

- Eran, Oded. The End of Jordan as We Know It?, Israel Journal of Foreign Affairs, Vol. 6, No. 3 (2012)

External links

- Government of Jordan

- Jordan national TV channel (live)

- "Jordan". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency.

- Jordan Corruption Profile from the Business Anti-Corruption Portal

- Jordan web resources provided by GovPubs at the University of Colorado Boulder Libraries

- Jordan at Curlie

- Jordan profile from the BBC News

Wikimedia Atlas of Jordan

Wikimedia Atlas of Jordan Jordan travel guide from Wikivoyage

Jordan travel guide from Wikivoyage Geographic data related to Jordan at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Jordan at OpenStreetMap- Key Development Forecasts for Jordan from International Futures.

- Use dmy dates from November 2012

- Jordan

- Member states of the Arab League

- Arabic-speaking countries and territories

- Western Asian countries

- Fertile Crescent

- Levant

- Middle Eastern countries

- Near Eastern countries

- Member states of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation

- States and territories established in 1946

- Southern Levant

- Former British colonies

- Member states of the United Nations