Edward Teller

Edward Teller | |

|---|---|

Teller Ede | |

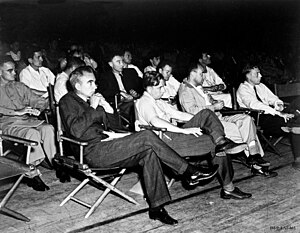

Teller in 1958 | |

| Born | January 15, 1908 |

| Died | September 9, 2003 (aged 95) Stanford, California, U.S. |

| Citizenship |

|

| Alma mater | |

| Known for | |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 2 |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics (theoretical) |

| Institutions | |

| Thesis | Über das Wasserstoffmolekülion (1930) |

| Doctoral advisor | Werner Heisenberg |

| Doctoral students |

|

| Other notable students | Jack Steinberger |

| Signature | |

Edward Teller (Template:Lang-hu; January 15, 1908 – September 9, 2003) was a Hungarian-American theoretical physicist and chemical engineer who is known colloquially as "the father of the hydrogen bomb" and one of the creators of the Teller–Ulam design.

Born in Austria-Hungary in 1908, Teller emigrated to the United States in the 1930s, one of the many so-called "Martians", a group of prominent Hungarian scientist émigrés. He made numerous contributions to nuclear and molecular physics, spectroscopy (in particular the Jahn–Teller and Renner–Teller effects), and surface physics. His extension of Enrico Fermi's theory of beta decay, in the form of Gamow–Teller transitions, provided an important stepping stone in its application, while the Jahn–Teller effect and the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) theory have retained their original formulation and are still mainstays in physics and chemistry.[1]

Teller made contributions to Thomas–Fermi theory, the precursor of density functional theory, a standard modern tool in the quantum mechanical treatment of complex molecules. In 1953, with Nicholas Metropolis, Arianna Rosenbluth, Marshall Rosenbluth, and Augusta Teller, Teller co-authored a paper that is a standard starting point for the applications of the Monte Carlo method to statistical mechanics and the Markov chain Monte Carlo literature in Bayesian statistics.[2] Teller was an early member of the Manhattan Project, which developed the first atomic bomb. He made a serious push to develop the first fusion-based weapons, but ultimately fusion bombs only appeared after World War II. He co-founded the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and was its director or associate director. After his controversial negative testimony in the Oppenheimer security clearance hearing of his former Los Alamos Laboratory superior, J. Robert Oppenheimer, the scientific community ostracized Teller.

Teller continued to find support from the U.S. government and military research establishment, particularly for his advocacy for nuclear energy development, a strong nuclear arsenal, and a vigorous nuclear testing program. In his later years, he advocated controversial technological solutions to military and civilian problems, including a plan to excavate an artificial harbor in Alaska using a thermonuclear explosive in what was called Project Chariot, and Ronald Reagan's Strategic Defense Initiative. Teller was a recipient of the Enrico Fermi Award and the Albert Einstein Award. He died on September 9, 2003, in Stanford, California, at 95.

Early life and work

Ede Teller was born on January 15, 1908, in Budapest, Austria-Hungary, into a Jewish family. His parents were Ilona (née Deutsch),[3][4] a pianist, and Max Teller, an attorney.[5] He attended the Minta Gymnasium in Budapest.[6] Teller was an agnostic. "Religion was not an issue in my family", he later wrote, "indeed, it was never discussed. My only religious training came because the Minta required that all students take classes in their respective religions. My family celebrated one holiday, the Day of Atonement, when we all fasted. Yet my father said prayers for his parents on Saturdays and on all the Jewish holidays. The idea of God that I absorbed was that it would be wonderful if He existed: We needed Him desperately but had not seen Him in many thousands of years."[7] Teller was a late talker, but he became very interested in numbers and for fun calculated large numbers in his head.[8]

Teller left Hungary for Germany in 1926, partly due to the discriminatory numerus clausus rule under Miklós Horthy's regime. The political climate and revolutions in Hungary during his youth instilled a lingering animosity toward Communism and Fascism.[9]

From 1926 to 1928, Teller studied mathematics and chemistry at the University of Karlsruhe, from which he graduated with a Bachelor of Science in chemical engineering.[10][11] He once stated that the person who was responsible for his becoming a physicist was Herman Mark, who was a visiting professor,[12] after hearing lectures on molecular spectroscopy where Mark made it clear to him that it was new ideas in physics that were radically changing the frontier of chemistry.[13] Mark was an expert in polymer chemistry, a field which is essential to understanding biochemistry, and Mark taught him about the leading breakthroughs in quantum physics made by Louis de Broglie, among others. It was his exposure to Mark's lectures that initially motivated Teller to switch to physics.[14] After informing his father of his intent to switch, his father was so concerned that he traveled to visit him and speak with his professors at the school. While a degree in chemical engineering was a sure path to a well-paying job at chemical companies, there was not such a clear-cut route for a career with a degree in physics. He was not privy to the discussions his father had with his professors, but the result was that he got his father's permission to become a physicist.[15]

Teller then attended the University of Munich, where he studied physics under Arnold Sommerfeld. On July 14, 1928, while still a student in Munich, while riding a streetcar to catch a train for a hike in the nearby Alps, he jumped off the car while it was still moving. He fell, and the wheel nearly severed his right foot. For the rest of his life, he walked with a limp, and on occasion he wore a prosthetic foot.[16][17] The painkillers he was taking were interfering with his thinking, so he decided to stop taking them, instead using his willpower to deal with the pain, including use of the placebo effect, by which he convinced himself that he had taken painkillers rather than water.[18] Werner Heisenberg said that it was the hardiness of Teller's spirit, rather than stoicism, that allowed him to cope so well with the accident.[19]

In 1929, Teller transferred to the University of Leipzig where in 1930, he received his PhD in physics under Heisenberg. Teller's dissertation dealt with one of the first accurate quantum mechanical treatments of the hydrogen molecular ion. That year, he befriended Russian physicists George Gamow and Lev Landau. Teller's lifelong friendship with a Czech physicist, George Placzek, was also very important for his scientific and philosophical development. It was Placzek who arranged a summer stay in Rome with Enrico Fermi in 1932, thus orienting Teller's scientific career in nuclear physics.[20] Also in 1930, Teller moved to the University of Göttingen, then one of the world's great centers of physics due to the presence of Max Born and James Franck,[21] but after Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany in January 1933, Germany became unsafe for Jewish people, and he left through the aid of the International Rescue Committee.[22] He went briefly to England, and moved for a year to Copenhagen, where he worked under Niels Bohr.[23] In February 1934 he married his long-time girlfriend Augusta Maria "Mici" (pronounced "Mitzi") Harkanyi, who was the sister of a friend. Since Mici was a Calvinist Christian, Edward and she were married in a Calvinist church.[19][24] He returned to England in September 1934.[25][26]

Mici had been a student in Pittsburgh and wanted to return to the United States. Her chance came in 1935, when, thanks to George Gamow, Teller was invited to the United States to become a professor of physics at George Washington University, where he worked with Gamow until 1941.[27] At George Washington University in 1937, Teller predicted the Jahn–Teller effect, which distorts molecules in certain situations; this affects the chemical reactions of metals, and in particular the coloration of certain metallic dyes.[28] Teller and Hermann Arthur Jahn analyzed it as a piece of purely mathematical physics. In collaboration with Stephen Brunauer and Paul Hugh Emmett, Teller also made an important contribution to surface physics and chemistry: the so-called Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) isotherm.[29] Teller and Mici became naturalized citizens of the United States on March 6, 1941.[30]

When World War II began, Teller wanted to contribute to the war effort. On the advice of the well-known Caltech aerodynamicist and fellow Hungarian émigré Theodore von Kármán, Teller collaborated with his friend Hans Bethe in developing a theory of shock-wave propagation. In later years, their explanation of the behavior of the gas behind such a wave proved valuable to scientists who were studying missile re-entry.[31]

Manhattan Project

Los Alamos Laboratory

In 1942, Teller was invited to be part of Robert Oppenheimer's summer planning seminar at the University of California, Berkeley, on the origins of the Manhattan Project, the U.S. effort to develop the first nuclear weapons. A few weeks earlier, Teller had been meeting with his friend and colleague Enrico Fermi about the prospects of atomic warfare, and Fermi had nonchalantly suggested that perhaps a weapon based on nuclear fission could be used to set off an even larger nuclear fusion reaction. Even though he initially explained to Fermi why he thought the idea would not work, Teller was fascinated by the possibility and was quickly bored with the idea of "just" an atomic bomb even though this was not yet anywhere near completion. At the Berkeley session, Teller diverted discussion from the fission weapon to the possibility of a fusion weapon—what he called the "Super", an early conception of the hydrogen bomb.[32][33]

Arthur Compton, the chairman of the University of Chicago physics department, coordinated the uranium research of Columbia University, Princeton University, the University of Chicago, and the University of California, Berkeley. To remove disagreement and duplication, Compton transferred the scientists to the Metallurgical Laboratory at Chicago.[34] Even though Teller and Mici were now American citizens, they had relatives in enemy countries, so Teller did not at first go to Chicago.[35] In early 1943, construction of the Los Alamos Laboratory Los Alamos, New Mexico began. With Oppenheimer as its director, the laboratory's purpose was to design an atomic bomb. Teller moved there in March 1943.[36] In Los Alamos, Teller managed to annoy his neighbors by playing piano late at night.[37]

Teller became part of the Theoretical (T) Division.[38][39] He was given a secret identity of Ed Tilden.[40] He was irked at being passed over as its head; the job was instead given to Hans Bethe. Oppenheimer had him investigate unusual approaches to building fission weapons, such as autocatalysis, in which the efficiency of the bomb would increase as the nuclear chain reaction progressed, but proved to be impractical.[39] He also investigated using uranium hydride instead of uranium metal, but its efficiency turned out to be "negligible or less".[41] He continued to push his ideas for a fusion weapon even though it had been put on a low priority during the war (as the creation of a fission weapon proved to be difficult enough).[38][39] On a visit to New York, he asked Maria Goeppert-Mayer to carry out calculations on the Super for him. She confirmed Teller's own results: the Super was not going to work.[42]

A special group was established under Teller in March 1944 to investigate the mathematics of an implosion-type nuclear weapon.[43] It too ran into difficulties. Because of his interest in the Super, Teller did not work as hard on the implosion calculations as Bethe wanted. These too were originally low-priority tasks, but the discovery of spontaneous fission in plutonium by Emilio Segrè's group gave the implosion bomb increased importance. In June 1944, at Bethe's request, Oppenheimer moved Teller out of T Division, and placed him in charge of a special group responsible for the Super, reporting directly to Oppenheimer. He was replaced by Rudolf Peierls from the British Mission, who in turn brought in Klaus Fuchs, who was later revealed to be a Soviet spy.[44][42] Teller's Super group became part of Fermi's F Division when he joined the Los Alamos Laboratory in September 1944.[44] It included Stanislaw Ulam, Jane Roberg, Geoffrey Chew, Harold and Mary Argo,[45] and Maria Goeppert-Mayer.[46]

Teller made valuable contributions to bomb research, especially in the elucidation of the implosion mechanism. He was the first to propose the solid pit design that was eventually successful. This design became known as a "Christy pit", after the physicist Robert F. Christy who made the pit a reality.[47][48][49][50] Teller was one of the few scientists to actually watch (with eye protection) the Trinity nuclear test in July 1945, rather than follow orders to lie on the ground with backs turned. He later said that the atomic flash "was as if I had pulled open the curtain in a dark room and broad daylight streamed in".[51]

Decision to drop the bombs

In the days before and after the first demonstration of a nuclear weapon (the Trinity test in July 1945), Hungarian Leo Szilard circulated the Szílard petition, which argued that a demonstration to the Japanese of the new weapon should occur prior to actual use on Japan, and that the weapons should never be used on people. In response to Szilard's petition, Teller consulted his friend Robert Oppenheimer. Teller believed that Oppenheimer was a natural leader and could help him with such a formidable political problem. Oppenheimer reassured Teller that the nation's fate should be left to the sensible politicians in Washington. Bolstered by Oppenheimer's influence, he decided to not sign the petition.[52]

Teller therefore penned a letter in response to Szilard that read:

I am not really convinced of your objections. I do not feel that there is any chance to outlaw any one weapon. If we have a slim chance of survival, it lies in the possibility to get rid of wars. The more decisive a weapon is the more surely it will be used in any real conflict and no agreements will help. Our only hope is in getting the facts of our results before the people. This might help to convince everybody that the next war would be fatal. For this purpose actual combat-use might even be the best thing.[53]

On reflection on this letter years later when he was writing his memoirs, Teller wrote:

First, Szilard was right. As scientists who worked on producing the bomb, we bore a special responsibility. Second, Oppenheimer was right. We did not know enough about the political situation to have a valid opinion. Third, what we should have done but failed to do was to work out the technical changes required for demonstrating the bomb [very high] over Tokyo and submit that information to President Truman.[54]

Unknown to Teller at the time, four of his colleagues were solicited by the then secret May to June 1945 Interim Committee. It is this organization which ultimately decided on how the new weapons should initially be used. The committee's four-member Scientific Panel was led by Oppenheimer, and concluded immediate military use on Japan was the best option:

The opinions of our scientific colleagues on the initial use of these weapons are not unanimous: they range from the proposal of a purely technical demonstration to that of the military application best designed to induce surrender ... Others emphasize the opportunity of saving American lives by immediate military use ... We find ourselves closer to these latter views; we can propose no technical demonstration likely to bring an end to the war; we see no acceptable alternative to direct military use.[55]

Teller later learned of Oppenheimer's solicitation and his role in the Interim Committee's decision to drop the bombs, having secretly endorsed an immediate military use of the new weapons. This was contrary to the impression that Teller had received when he had personally asked Oppenheimer about the Szilard petition: that the nation's fate should be left to the sensible politicians in Washington. Following Teller's discovery of this, his relationship with his advisor began to deteriorate.[52]

In 1990, the historian Barton Bernstein argued that it is an "unconvincing claim" by Teller that he was a "covert dissenter" to the use of the bomb.[56] In his 2001 Memoirs, Teller claims that he did lobby Oppenheimer, but that Oppenheimer had convinced him that he should take no action and that the scientists should leave military questions in the hands of the military; Teller claims he was not aware that Oppenheimer and other scientists were being consulted as to the actual use of the weapon and implies that Oppenheimer was being hypocritical.[57]

Hydrogen bomb

Despite an offer from Norris Bradbury, who had replaced Oppenheimer as the director of Los Alamos in November 1945 to become the head of the Theoretical (T) Division, Teller left Los Alamos on February 1, 1946, to return to the University of Chicago as a professor and close associate of Fermi and Maria Goeppert Mayer.[58] Goepper-Mayer's work on the internal structure of the elements would earn her the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1963.[59]

On April 18–20, 1946, Teller participated in a conference at Los Alamos to review the wartime work on the Super. The properties of thermonuclear fuels such as deuterium and the possible design of a hydrogen bomb were discussed. It was concluded that Teller's assessment of a hydrogen bomb had been too favourable, and that both the quantity of deuterium needed, as well as the radiation losses during deuterium burning, would shed doubt on its workability. Addition of expensive tritium to the thermonuclear mixture would likely lower its ignition temperature, but even so, nobody knew at that time how much tritium would be needed, and whether even tritium addition would encourage heat propagation.[60][61]

At the end of the conference, in spite of opposition by some members such as Robert Serber, Teller submitted an optimistic report in which he said that a hydrogen bomb was feasible, and that further work should be encouraged on its development. Fuchs also participated in this conference, and transmitted this information to Moscow. With John von Neumann, he contributed an idea of using implosion to ignite the Super. The model of Teller's "classical Super" was so uncertain that Oppenheimer would later say that he wished the Russians were building their own hydrogen bomb based on that design, so that it would almost certainly delay their progress on it.[60]

By 1949, Soviet-backed governments had already begun seizing control throughout Eastern Europe, forming such puppet states as the Hungarian People's Republic in Teller's homeland of Hungary, where much of his family still lived, on August 20, 1949.[62] Following the Soviet Union's first test detonation of an atomic bomb on August 29, 1949, President Harry Truman announced a crash development program for a hydrogen bomb.[63]

Teller returned to Los Alamos in 1950 to work on the project. He insisted on involving more theorists, but many of Teller's prominent colleagues, like Fermi and Oppenheimer, were sure that the project of the H-bomb was technically infeasible and politically undesirable. None of the available designs were yet workable.[63] However, Soviet scientists who had worked on their own hydrogen bomb have claimed that they developed it independently.[64]

In 1950, calculations by the Polish mathematician Stanislaw Ulam and his collaborator Cornelius Everett, along with confirmations by Fermi, had shown that not only was Teller's earlier estimate of the quantity of tritium needed for the reaction to begin was low, but that even with higher amounts of tritium, the energy loss in the fusion process would be too great to enable the fusion reaction to propagate. However, in 1951 Teller and Ulam made a breakthrough, and invented a new design, proposed in a classified March 1951 paper, On Heterocatalytic Detonations I: Hydrodynamic Lenses and Radiation Mirrors, for a practical megaton-range H-bomb. The exact contribution provided respectively from Ulam and Teller to what became known as the Teller–Ulam design is not definitively known in the public domain, and the exact contributions of each and how the final idea was arrived upon has been a point of dispute in both public and classified discussions since the early 1950s.[65]

In an interview with Scientific American from 1999, Teller told the reporter:

I contributed; Ulam did not. I'm sorry I had to answer it in this abrupt way. Ulam was rightly dissatisfied with an old approach. He came to me with a part of an idea which I already had worked out and had difficulty getting people to listen to. He was willing to sign a paper. When it then came to defending that paper and really putting work into it, he refused. He said, "I don't believe in it."[9]

The issue is controversial. Bethe considered Teller's contribution to the invention of the H-bomb a true innovation as early as 1952,[66] and referred to his work as a "stroke of genius" in 1954.[67] In both cases, however, Bethe emphasized Teller's role as a way of stressing that the development of the H-bomb could not have been hastened by additional support or funding, and Teller greatly disagreed with Bethe's assessment. Other scientists (antagonistic to Teller, such as J. Carson Mark) have claimed that Teller would have never gotten any closer without the assistance of Ulam and others.[68] Ulam himself claimed that Teller only produced a "more generalized" version of Ulam's original design.[69]

The breakthrough—the details of which are still classified—was apparently the separation of the fission and fusion components of the weapons, and to use the X-rays produced by the fission bomb to first compress the fusion fuel (by a process known as "radiation implosion") before igniting it. Ulam's idea seems to have been to use mechanical shock from the primary to encourage fusion in the secondary, while Teller quickly realized that X-rays from the primary would do the job much more symmetrically. Some members of the laboratory (J. Carson Mark in particular) later expressed the opinion that the idea to use the X-rays would have eventually occurred to anyone working on the physical processes involved, and that the obvious reason why Teller thought of it right away was because he was already working on the "Greenhouse" tests for the spring of 1951, in which the effect of X-rays from a fission bomb on a mixture of deuterium and tritium was going to be investigated.[65]

Priscilla Johnson McMillan in her book The Ruin of J. Robert Oppenheimer: And the Birth of the Modern Arms Race, writes that Teller "concealed the role" of Ulam, and that only "radiation implosion" was Teller's idea. Teller even refused to sign the patent application, because it would need Ulam's signature. Thomas Powers writes that "of course the bomb designers all knew the truth, and many considered Teller the lowest, most contemptible kind of offender in the world of science, a stealer of credit".[70]

Whatever the actual components of the so-called Teller–Ulam design and the respective contributions of those who worked on it, after it was proposed it was immediately seen by the scientists working on the project as the answer which had been so long sought. Those who previously had doubted whether a fission-fusion bomb would be feasible at all were converted into believing that it was only a matter of time before both the US and the USSR had developed multi-megaton weapons. Even Oppenheimer, who was originally opposed to the project, called the idea "technically sweet".[71]

Though he had helped to come up with the design and had been a long-time proponent of the concept, Teller was not chosen to head the development project (his reputation of a thorny personality likely played a role in this). In 1952 he left Los Alamos and joined the newly established Livermore branch of the University of California Radiation Laboratory, which had been created largely through his urging. After the detonation of Ivy Mike, the first thermonuclear weapon to utilize the Teller–Ulam configuration, on November 1, 1952, Teller became known in the press as the "father of the hydrogen bomb". Teller himself refrained from attending the test—he claimed not to feel welcome at the Pacific Proving Grounds—and instead saw its results on a seismograph at Berkeley.[72]

There was an opinion that by analyzing the fallout from this test, the Soviets (led in their H-bomb work by Andrei Sakharov) could have deciphered the new American design. However, this was later denied by the Soviet bomb researchers.[73] Because of official secrecy, little information about the bomb's development was released by the government, and press reports often attributed the entire weapon's design and development to Teller and his new Livermore Laboratory (when it was actually developed by Los Alamos).[64]

Many of Teller's colleagues were irritated that he seemed to enjoy taking full credit for something he had only a part in, and in response, with encouragement from Enrico Fermi, Teller authored an article titled "The Work of Many People", which appeared in Science magazine in February 1955, emphasizing that he was not alone in the weapon's development. He would later write in his memoirs that he had told a "white lie" in the 1955 article in order to "soothe ruffled feelings", and claimed full credit for the invention.[74][75]

Teller was known for getting engrossed in projects which were theoretically interesting but practically infeasible (the classic "Super" was one such project.)[37] About his work on the hydrogen bomb, Bethe said:

Nobody will blame Teller because the calculations of 1946 were wrong, especially because adequate computing machines were not available at Los Alamos. But he was blamed at Los Alamos for leading the laboratory, and indeed the whole country, into an adventurous programme on the basis of calculations, which he himself must have known to have been very incomplete.[76]

During the Manhattan Project, Teller advocated the development of a bomb using uranium hydride, which many of his fellow theorists said would be unlikely to work.[77] At Livermore, Teller continued work on the hydride bomb, and the result was a dud.[78] Ulam once wrote to a colleague about an idea he had shared with Teller: "Edward is full of enthusiasm about these possibilities; this is perhaps an indication they will not work."[79] Fermi once said that Teller was the only monomaniac he knew who had several manias.[80]

Carey Sublette of Nuclear Weapon Archive argues that Ulam came up with the radiation implosion compression design of thermonuclear weapons, but that on the other hand Teller has gotten little credit for being the first to propose fusion boosting in 1945, which is essential for miniaturization and reliability and is used in all of today's nuclear weapons.[81]

Oppenheimer controversy

Teller became controversial in 1954 when he testified against Oppenheimer at Oppenheimer's security clearance hearing. Teller had clashed with Oppenheimer many times at Los Alamos over issues relating both to fission and fusion research, and, during Oppenheimer's hearing, he was the only member of the scientific community to state that Oppenheimer should not be granted security clearance.[82]

Asked at the hearing by Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) attorney Roger Robb whether he was planning "to suggest that Dr. Oppenheimer is disloyal to the United States", Teller replied that:

I do not want to suggest anything of the kind. I know Oppenheimer as an intellectually most alert and a very complicated person, and I think it would be presumptuous and wrong on my part if I would try in any way to analyze his motives. But I have always assumed, and I now assume that he is loyal to the United States. I believe this, and I shall believe it until I see very conclusive proof to the opposite.[83]

He was immediately asked whether he believed that Oppenheimer was a "security risk", to which he testified:

In a great number of cases I have seen Dr. Oppenheimer act—I understood that Dr. Oppenheimer acted—in a way which for me was exceedingly hard to understand. I thoroughly disagreed with him in numerous issues and his actions frankly appeared to me confused and complicated. To this extent I feel that I would like to see the vital interests of this country in hands which I understand better, and therefore trust more. In this very limited sense I would like to express a feeling that I would feel personally more secure if public matters would rest in other hands.[67]

Teller also testified that Oppenheimer's opinion about the thermonuclear program seemed to be based more on the scientific feasibility of the weapon than anything else. He additionally testified that Oppenheimer's direction of Los Alamos was "a very outstanding achievement" both as a scientist and an administrator, lauding his "very quick mind" and that he made "just a most wonderful and excellent director".[67]

After this, however, he detailed ways in which he felt that Oppenheimer had hindered his efforts towards an active thermonuclear development program, and at length criticized Oppenheimer's decisions not to invest more work onto the question at different points in his career, saying: "If it is a question of wisdom and judgment, as demonstrated by actions since 1945, then I would say one would be wiser not to grant clearance."[67]

By recasting a difference of judgment over the merits of the early work on the hydrogen bomb project into a matter of a security risk, Teller effectively damned Oppenheimer in a field where security was necessarily of paramount concern. Teller's testimony thereby rendered Oppenheimer vulnerable to charges by a Congressional aide that he was a Soviet spy, which resulted in the destruction of Oppenheimer's career.[84]

Oppenheimer's security clearance was revoked after the hearings. Most of Teller's former colleagues disapproved of his testimony and he was ostracized by much of the scientific community.[82] After the fact, Teller consistently denied that he was intending to damn Oppenheimer, and even claimed that he was attempting to exonerate him. However, documentary evidence has suggested that this was likely not the case. Six days before the testimony, Teller met with an AEC liaison officer and suggested "deepening the charges" in his testimony.[85]

Teller always insisted that his testimony had not significantly harmed Oppenheimer. In 2002, Teller contended that Oppenheimer was "not destroyed" by the security hearing but "no longer asked to assist in policy matters". He claimed his words were an overreaction, because he had only just learned of Oppenheimer's failure to immediately report an approach by Haakon Chevalier, who had approached Oppenheimer to help the Russians. Teller said that, in hindsight, he would have responded differently.[82]

Historian Richard Rhodes said that in his opinion it was already a foregone conclusion that Oppenheimer would have his security clearance revoked by then AEC chairman Lewis Strauss, regardless of Teller's testimony. However, as Teller's testimony was the most damning, he was singled out and blamed for the hearing's ruling, losing friends due to it, such as Robert Christy, who refused to shake his hand in one infamous incident. This was emblematic of his later treatment which resulted in him being forced into the role of an outcast of the physics community, thus leaving him little choice but to align himself with industrialists.[86]

US government work and political advocacy

After the Oppenheimer controversy, Teller became ostracized by much of the scientific community, but was still quite welcome in the government and military science circles. Along with his traditional advocacy for nuclear energy development, a strong nuclear arsenal, and a vigorous nuclear testing program, he had helped to develop nuclear reactor safety standards as the chair of the Reactor Safeguard Committee to the AEC in the late 1940s,[87] and in the late 1950s headed an effort at General Atomics which designed research reactors in which a nuclear meltdown would be impossible. The TRIGA (Training, Research, Isotopes, General Atomic) has been built and used in hundreds of hospitals and universities worldwide for medical isotope production and research.[88]

Teller promoted increased defense spending to counter the perceived Soviet missile threat. He was a signatory to the 1958 report by the military sub-panel of the Rockefeller Brothers funded Special Studies Project, which called for a $3 billion annual increase in America's military budget.[89]

In 1956 he attended the Project Nobska anti-submarine warfare conference, where discussion ranged from oceanography to nuclear weapons. In the course of discussing a small nuclear warhead for the Mark 45 torpedo, he started a discussion on the possibility of developing a physically small one-megaton nuclear warhead for the Polaris missile. His counterpart in the discussion, J. Carson Mark from the Los Alamos National Laboratory, at first insisted it could not be done. However, Dr. Mark eventually stated that a half-megaton warhead of small enough size could be developed. This yield, roughly thirty times that of the Hiroshima bomb, was enough for Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Arleigh Burke, who was present in person, and Navy strategic missile development shifted from Jupiter to Polaris by the end of the year.[90]

He was Director of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, which he helped to found with Ernest O. Lawrence, from 1958 to 1960, and after that he continued as an associate director. He chaired the committee that founded the Space Sciences Laboratory at Berkeley. He also served concurrently as a professor of physics at the University of California, Berkeley.[91] He was a tireless advocate of a strong nuclear program and argued for continued testing and development—in fact, he stepped down from the directorship of Livermore so that he could better lobby against the proposed test ban. He testified against the test ban both before Congress as well as on television.[92]

Teller established the Department of Applied Science at the University of California, Davis and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in 1963, which holds the Edward Teller endowed professorship in his honor.[93] In 1975 he retired from both the lab and Berkeley, and was named director emeritus of the Livermore Laboratory and appointed Senior Research Fellow at the Hoover Institution.[37] After the end of communism in Hungary in 1989, he made several visits to his country of origin, and paid careful attention to the political changes there.[94]

Global climate change

Teller was one of the first prominent people to raise the danger of climate change, driven by the burning of fossil fuels. At an address to the membership of the American Chemical Society in December 1957, Teller warned that the large amount of carbon-based fuel that had been burnt since the mid-19th century was increasing the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, which would "act in the same way as a greenhouse and will raise the temperature at the surface", and that he had calculated that if the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere increased by 10% "an appreciable part of the polar ice might melt".[95]

In 1959, at a symposium organised by the American Petroleum Institute and the Columbia Graduate School of Business for the centennial of the American oil industry, Edward Teller warned that:[96]

I am to talk to you about energy in the future. I will start by telling you why I believe that the energy resources of the past must be supplemented. ... And this, strangely, is the question of contaminating the atmosphere. ... Whenever you burn conventional fuel, you create carbon dioxide. ... Carbon dioxide has a strange property. It transmits visible light but it absorbs the infrared radiation which is emitted from the earth. Its presence in the atmosphere causes a greenhouse effect. ... It has been calculated that a temperature rise corresponding to a 10 per cent increase in carbon dioxide will be sufficient to melt the icecap and submerge New York. All the coastal cities would be covered, and since a considerable percentage of the human race lives in coastal regions, I think that this chemical contamination is more serious than most people tend to believe.

Non-military uses of nuclear explosions

Teller was one of the strongest and best-known advocates for investigating non-military uses of nuclear explosives, which the United States explored under Operation Plowshare. One of the most controversial projects he proposed was a plan to use a multi-megaton hydrogen bomb to dig a deep-water harbor more than a mile long and half a mile wide to use for shipment of resources from coal and oil fields through Point Hope, Alaska. The Atomic Energy Commission accepted Teller's proposal in 1958 and it was designated Project Chariot. While the AEC was scouting out the Alaskan site, and having withdrawn the land from the public domain, Teller publicly advocated the economic benefits of the plan, but was unable to convince local government leaders that the plan was financially viable.[97]

Other scientists criticized the project as being potentially unsafe for the local wildlife and the Inupiat people living near the designated area, who were not officially told of the plan until March 1960.[98][99] Additionally, it turned out that the harbor would be ice-bound for nine months out of the year. In the end, due to the financial infeasibility of the project and the concerns over radiation-related health issues, the project was abandoned in 1962.[100]

A related experiment which also had Teller's endorsement was a plan to extract oil from the tar sands in northern Alberta with nuclear explosions, titled Project Oilsands. The plan actually received the endorsement of the Alberta government, but was rejected by the Government of Canada under Prime Minister John Diefenbaker, who was opposed to having any nuclear weapons in Canada. After Diefenbaker was out of office, Canada went on to have nuclear weapons, from a US nuclear sharing agreement, from 1963 to 1984.[101][102]

Teller also proposed the use of nuclear bombs to prevent damage from powerful hurricanes. He argued that when conditions in the Atlantic Ocean are right for the formation of hurricanes, the heat generated by well-placed nuclear explosions could trigger several small hurricanes, rather than waiting for nature to build one large one.[103]

Nuclear technology and Israel

For some twenty years, Teller advised Israel on nuclear matters in general, and on the building of a hydrogen bomb in particular.[104] In 1952, Teller and Oppenheimer had a long meeting with David Ben-Gurion in Tel Aviv, telling him that the best way to accumulate plutonium was to burn natural uranium in a nuclear reactor. Starting in 1964, a connection between Teller and Israel was made by the physicist Yuval Ne'eman, who had similar political views. Between 1964 and 1967, Teller visited Israel six times, lecturing at Tel Aviv University, and advising the chiefs of Israel's scientific-security circle as well as prime ministers and cabinet members.[105]

In 1967 when the Israeli nuclear program was nearing completion, Teller informed Neeman that he was going to tell the CIA that Israel had built nuclear weapons, and explain that it was justified by the background of the Six-Day War. After Neeman cleared it with Prime Minister Levi Eshkol, Teller briefed the head of the CIA's Office of Science and Technology, Carl Duckett. It took a year for Teller to convince the CIA that Israel had obtained nuclear capability; the information then went through CIA Director Richard Helms to the president at that time, Lyndon B. Johnson. Teller also persuaded them to end the American attempts to inspect the Negev Nuclear Research Center in Dimona. In 1976 Duckett testified in Congress before the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, that after receiving information from an "American scientist", he drafted a National Intelligence Estimate on Israel's nuclear capability.[106]

In the 1980s, Teller again visited Israel to advise the Israeli government on building a nuclear reactor.[107] Three decades later, Teller confirmed that it was during his visits that he concluded that Israel was in possession of nuclear weapons. After conveying the matter to the U.S. government, Teller reportedly said: "They [Israel] have it, and they were clever enough to trust their research and not to test, they know that to test would get them into trouble."[106]

Three Mile Island

Teller had a heart attack in 1979, and blamed it on Jane Fonda, who had starred in The China Syndrome, which depicted a fictional reactor accident and was released less than two weeks before the Three Mile Island accident. She spoke out against nuclear power while promoting the film. After the accident, Teller acted quickly to lobby in defence of nuclear energy, testifying to its safety and reliability, and soon after one flurry of activity suffered the attack. He signed a two-page-spread ad in the July 31, 1979, issue of The Washington Post with the headline "I was the only victim of Three-Mile Island".[108] It opened with:

On May 7, a few weeks after the accident at Three-Mile Island, I was in Washington. I was there to refute some of that propaganda that Ralph Nader, Jane Fonda and their kind are spewing to the news media in their attempt to frighten people away from nuclear power. I am 71 years old, and I was working 20 hours a day. The strain was too much. The next day, I suffered a heart attack. You might say that I was the only one whose health was affected by that reactor near Harrisburg. No, that would be wrong. It was not the reactor. It was Jane Fonda. Reactors are not dangerous.[109]

Strategic Defense Initiative

In the 1980s, Teller began a strong campaign for what was later called the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), derided by critics as "Star Wars", the concept of using ground and satellite-based lasers, particle beams and missiles to destroy incoming Soviet ICBMs. Teller lobbied with government agencies—and got the approval of President Ronald Reagan—for a plan to develop a system using elaborate satellites which used atomic weapons to fire X-ray lasers at incoming missiles—as part of a broader scientific research program into defenses against nuclear weapons.[110]

Scandal erupted when Teller (and his associate Lowell Wood) were accused of deliberately overselling the program and perhaps encouraging the dismissal of a laboratory director (Roy Woodruff) who had attempted to correct the error.[111] His claims led to a joke which circulated in the scientific community, that a new unit of unfounded optimism was designated as the teller; one teller was so large that most events had to be measured in nanotellers or picotellers.[112]

Many prominent scientists argued that the system was futile. Hans Bethe, along with IBM physicist Richard Garwin and Cornell University colleague Kurt Gottfried, wrote an article in Scientific American which analyzed the system and concluded that any putative enemy could disable such a system by the use of suitable decoys that would cost a very small fraction of the SDI program.[113]

In 1987 Teller published a book entitled Better a Shield than a Sword, which supported civil defense and active protection systems. His views on the role of lasers in SDI were published, and are available, in two 1986–87 laser conference proceedings.[114][115]

Asteroid impact avoidance

Following the 1994 Shoemaker-Levy 9 comet impacts with Jupiter, Teller proposed to a collective of U.S. and Russian ex-Cold War weapons designers in a 1995 planetary defense workshop at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, that they collaborate to design a 1 gigaton nuclear explosive device, which would be equivalent to the kinetic energy of a 1 km diameter asteroid.[116][117][118] In order to safeguard the earth, the theoretical 1 Gt device would weigh about 25–30 tons—light enough to be lifted on the Russian Energia rocket—and could be used to instantaneously vaporize a 1 km asteroid, or divert the paths of extinction event class asteroids (greater than 10 km in diameter) with a few months' notice; with 1-year notice, at an interception location no closer than Jupiter, it would also be capable of dealing with the even rarer short period comets which can come out of the Kuiper belt and transit past Earth orbit within 2 years. For comets of this class, with a maximum estimated 100 km diameter, Charon served as the hypothetical threat.[116][117][118]

Death and legacy

Teller died in Stanford, California on September 9, 2003, at the age of 95.[37] He had suffered a stroke two days before and had long been experiencing a number of conditions related to his advanced age.[119]

Teller's vigorous advocacy for strength through nuclear weapons, especially when so many of his wartime colleagues later expressed regret about the arms race, made him an easy target for the "mad scientist" stereotype. In 1991 he was awarded one of the first Ig Nobel Prizes for Peace in recognition of his "lifelong efforts to change the meaning of peace as we know it". He was also rumored to be one of the inspirations for the character of Dr. Strangelove in Stanley Kubrick's 1964 satirical film of the same name.[37] In the aforementioned Scientific American interview from 1999, he was reported as having bristled at the question: "My name is not Strangelove. I don't know about Strangelove. I'm not interested in Strangelove. What else can I say? ... Look. Say it three times more and I throw you out of this office."[9]

Nobel Prize winning physicist Isidor I. Rabi once suggested that "It would have been a better world without Teller."[120]

In 1981, Teller became a founding member of the World Cultural Council.[121] A wish for his 100th birthday, made around the time of his 90th, was for Lawrence Livermore's scientists to give him "excellent predictions—calculations and experiments—about the interiors of the planets".[19]

In 1986, he was awarded the United States Military Academy's Sylvanus Thayer Award. He was elected a member of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences in 1948.[122] He was a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the American Nuclear Society,[123] and the American Physical Society.[124] Among the honors he received were the Albert Einstein Award in 1958,[91] the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement in 1961,[125] the Enrico Fermi Award in 1962,[91] the Herzl Prize in 1978, the Eringen Medal in 1980,[126] the Harvey Prize in 1975, the National Medal of Science in 1983, the Presidential Citizens Medal in 1989,[91] and the Corvin Chain in 2001.[127] He was also named as part of the group of "U.S. Scientists" who were Time magazine's People of the Year in 1960,[128] and an asteroid, 5006 Teller, is named after him.[129] He was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President George W. Bush in 2003, less than two months before his death.[37]

His final paper, published posthumously, advocated the construction of a prototype liquid fluoride thorium reactor.[130][131] The genesis and impetus for this last paper was recounted by the co-author Ralph Moir in 2007.[132]

He was portrayed by David Suchet in the 1980 TV miniseries Oppenheimer and by Benny Safdie in the 2023 biopic film Oppenheimer.[133]

Bibliography

- Our Nuclear Future; Facts, Dangers, and Opportunities (1958), with Albert L. Latter as co-author[134]

- Basic Concepts of Physics (1960)

- The Legacy of Hiroshima (1962), with Allen Brown[135][136]

- The Constructive Uses of Nuclear Explosions (1968)

- Energy from Heaven and Earth (1979)

- The Pursuit of Simplicity (1980)

- Better a Shield Than a Sword: Perspectives on Defense and Technology (1987)[137]

- Conversations on the Dark Secrets of Physics (1991), with Wendy Teller and Wilson Talley ISBN 978-0306437724[138][139]

- Memoirs: A Twentieth-Century Journey in Science and Politics. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Publishing. 2001 – via Internet Archive., with Judith Shoolery[140]

References

Citations

- ^ Goodchild 2004, p. 36.

- ^ Metropolis, Nicholas; Rosenbluth, Arianna W.; Rosenbluth, Marshall N.; Teller, Augusta H.; Teller, Edward (1953). "Equation of State Calculations by Fast Computing Machines". Journal of Chemical Physics. 21 (6): 1087–1092. Bibcode:1953JChPh..21.1087M. doi:10.1063/1.1699114. OSTI 4390578. S2CID 1046577.

- ^ The Martians of Science: Five Physicists Who Changed the Twentieth Century. Oxford University Press, USA. 2006. ISBN 978-0198039679.

- ^ Libby, Stephen B.; Van Bibber, Karl A. (2010). Edward Teller Centennial Symposium: Modern Physics and the Scientific Legacy of Edward Teller: Livermore, CA 2008. World Scientific. ISBN 978-9812838001.

- ^ "Edward Teller Is Dead at 95; Fierce Architect of H-Bomb". The New York Times. September 10, 2003.

- ^ Horvath, Tibor (June 1997). "Theodore Karman, Paul Wigner, John Neumann, Leo Szilard, Edward Teller and Their Ideas of Ultimate Reality and Meaning". Ultimate Reality and Meaning. 20 (2–3): 123–146. doi:10.3138/uram.20.2-3.123. ISSN 0709-549X.

- ^ Teller & Shoolery 2001, p. 32.

- ^ Video in which Teller recalls his earliest memories on YouTube

- ^ a b c Stix, Gary (October 1999). "Infamy and honor at the Atomic Café: Edward Teller has no regrets about his contentious career". Scientific American: 42–43. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1099-42. Retrieved November 25, 2007.

- ^ "Edward Teller - Nuclear Museum". ahf.nuclearmuseum.org/. Retrieved June 10, 2023.

- ^ "Manhattan Project Scientists: Edward Teller (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved June 10, 2023.

- ^ Edward Teller - The inspiration of Herman Mark (segment 18 of 147), June 1996 interview with John H. Nuckolls, former director of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (posted on January 24, 2008)

Alternate source video (uploaded to Web of Stories YouTube channel on September 27, 2017) - ^ Edward Teller Facts, quote:

"Leaving Hungary because of anti-Semitism, Teller went to Germany to study chemistry and mathematics at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology from 1926 to 1928. A lecture he heard by Herman Mark on the new science of molecular spectroscopy made a lasting impression on him: "He [Mark] made it clear that new ideas in physics had changed chemistry into an important part of the forefront of physics." - ^ Edward Teller – Wave-particle duality sparked a fascination with physics (segment 16 of 147), June 1996 interview with John H. Nuckolls, former director of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (posted on 24 January 2008)

Alternate source video (uploaded to Web of Stories YouTube channel on Sep 27, 2017)

Quote:

"This theory [of polymer chemistry, and its relation to quantum physics] managed to make in me a big change from an interest in mathematics to an interest in physics." - ^ Edward Teller – Permission to become a physicist (segment 17 of 147), June 1996 interview with John H. Nuckolls, former director of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (posted on January 24, 2008)

Alternate source video (uploaded to Web of Stories YouTube channel on September 27, 2017) - ^ Edward Teller – Jumping off the moving train (segment 20 of 147), June 1996 interview with John H. Nuckolls, former director of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (posted on January 24, 2008) (uploaded to Web of Stories YouTube channel on September 27, 2017)

- ^ Rhodes 1986, p. 189.

- ^ Edward Teller and the Other Martians of Science by Istvan Hargittai, NIST Colloquium, November 4, 2011 (published on YouTube, June 26, 2012)

Note:

Speaker is the author of The Martians of Science: Five Physicists Who Changed the Twentieth Century (2006, ISBN 978-0195178456). - ^ a b c Witt, Gloria. "Glimpses of an exceptional man". Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. Archived from the original on March 24, 2016. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- ^ Teller & Shoolery 2001, p. 80; see also "Interview with Edward Teller, part 40. Going to Rome with Placzek to visit Fermi". Peoples Archive. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- ^ Teller & Shoolery 2001, pp. 70–72.

- ^ Teller & Shoolery 2001, pp. 77–80.

- ^ Teller & Shoolery 2001, pp. 94–104.

- ^ Edward Teller, the Real Dr. Strangelove. Harvard University Press. 2004. ISBN 978-0674016699.

- ^ Teller & Shoolery 2001, p. 109.

- ^ Hargittai, István; Hargittai, Magdolna (2015). Budapest Scientific: A Guidebook. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0191068492.

- ^ Teller & Shoolery 2001, pp. 118–120.

- ^ Jahn, H.; Teller, E. (1937). "Stability of Polyatomic Molecules in Degenerate Electronic States. I. Orbital Degeneracy". Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 161 (905): 220–235. Bibcode:1937RSPSA.161..220J. doi:10.1098/rspa.1937.0142.

- ^ Journal of the American Chemical Society, 60 (2), pp. 309–319 (1938).

- ^ Teller & Shoolery 2001, p. 151.

- ^ Brown & Lee 2009, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Herken 2002, pp. 63–67.

- ^ Rhodes 1986, pp. 415–420.

- ^ Rhodes 1986, pp. 399–400.

- ^ Teller & Shoolery 2001, p. 158.

- ^ Teller & Shoolery 2001, pp. 163–165.

- ^ a b c d e f Shurkin, Joel N (September 10, 2003). "Edward Teller, 'Father of the Hydrogen Bomb,' is dead at 95". Stanford Report. Stanford News Service. Archived from the original on May 13, 2015. Retrieved November 27, 2007.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b Hoddeson et al. 1993, pp. 76–77.

- ^ a b c Herken 2002, pp. 85–87.

- ^ Hoddeson et al. 1993, p. 95.

- ^ Hoddeson et al. 1993, p. 181.

- ^ a b Herken 2002, pp. 117–118.

- ^ Hoddeson et al. 1993, pp. 129–130.

- ^ a b Hoddeson et al. 1993, pp. 160–162.

- ^ Hoddeson et al. 1993, p. 204.

- ^ Dash 1973, pp. 296–299.

- ^ "Robert F. Christy". Atomic Heritage Foundation. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- ^ Wellerstein, Alex. "Christy's Gadget: Reflections on a death". Restricted data blog. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- ^ "Hans Bethe 94 – Help from the British, and the 'Christy Gadget'". Web of Stories. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- ^ "Constructing the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb". Web of Stories. Archived from the original on October 10, 2014. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- ^ "Edward Teller, RIP". The New Atlantis (3): 105–107. Fall 2003. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- ^ a b Blumberg & Panos 1990, pp. 82–83.

- ^ "Edward Teller to Leo Szilard" (PDF). Nuclear Secrecy blog. July 2, 1945. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved November 15, 2015. Copy in the J. Robert Oppenheimer papers (MS35188), Library of Congress, Washington, DC, Box 71, Folder, Teller, Edward, 1942–1963

- ^ Teller & Shoolery 2001, p. 206.

- ^ "Recommendations on the Immediate Use of Nuclear Weapons by the Scientific Panel of the Interim Committee, June 16, 1945". Nuclear Age Peace Foundation. Archived from the original on February 4, 2011. Retrieved March 2, 2011.

- ^ "Essay Review-From the A-Bomb to Star Wars: Edward Teller's History. Better A Shield Than a Sword: Perspectives on Defense and Technology". Technology and Culture. 31 (4): 848. October 1990.

- ^ Teller & Shoolery 2001, pp. 206–209.

- ^ Herken 2002, pp. 153–155.

- ^ Teller & Shoolery 2001, pp. 239–243.

- ^ a b Rhodes 1995, pp. 252–255.

- ^ Herken 2002, pp. 171–173.

- ^ "Early Research on Fusion Weapons". Nuclear Weapons Archive. November 15, 2015.

- ^ a b Herken 2002, pp. 201–210.

- ^ a b Khariton, Yuli; Smirnov, Yuri (May 1993). "The Khariton version". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 49 (4): 20–31. Bibcode:1993BuAtS..49d..20K. doi:10.1080/00963402.1993.11456341.

- ^ a b Rhodes 1995, pp. 461–472.

- ^ Bethe, Hans (1952). "Memorandum on the History of the Thermonuclear Program". Federation of American Scientists. Retrieved December 15, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Bethe, Hans (1954). "Testimony in the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer". Atomic Archive. Retrieved November 10, 2006.

- ^ Carlson, Bengt (July–August 2003). "How Ulam set the stage". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 59 (4): 46–51. doi:10.2968/059004013.

- ^ Ulam 1983, p. 220.

- ^ Powers, Thomas. "An American Tragedy". The New York Review of Books. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ^ Thorpe 2006, p. 106.

- ^ Herken 2002, pp. 256–257.

- ^ Gorelik 2009, pp. 169–197.

- ^ Teller & Shoolery 2001, p. 407.

- ^ Uchii, Soshichi (July 22, 2003). "Review of Edward Teller's Memoirs". PHS Newsletter. 52. Archived from the original on July 25, 2011. Retrieved October 22, 2009.

- ^ Bethe, Hans A. (1982). "Comments on The History of the H-Bomb" (PDF). Los Alamos Science. 3 (3): 47. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved November 28, 2007.

- ^ Goodchild 2004, p. 217.

- ^ Herken 2002, pp. 284–286.

- ^ Rhodes 1995, p. 467.

- ^ Goodchild 2004, p. 131.

- ^ Sublette, Carey. "Basic Principles of Staged Radiation Implosion ("Teller–Ulam Design")". Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- ^ a b c Lennick, Michael (June–July 2005). "A Final Interview with Edward Teller". American Heritage. Archived from the original on May 17, 2008.

- ^ Teller, Edward (April 28, 1954). "In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer: Transcript of Hearing Before Personnel Security Board". pbs.org. United States Government Printing Office. Archived from the original on December 11, 2008. Retrieved November 24, 2007.

- ^ Broad, William J. (October 11, 2014). "Transcripts Kept Secret for 60 years Bolster Defense of Oppenheimer's Loyalty". The New York Times. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- ^ Shapin, Steven (April 25, 2002). "Megaton Man". London Review of Books. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved November 24, 2007.

- ^ "Richard Rhodes on: Edward Teller's Role in the Oppenheimer Hearings". PBS. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- ^ Teller & Shoolery 2001, pp. 263–272.

- ^ Teller & Shoolery 2001, pp. 423–424.

- ^ "Rockefeller Report Calls for Meeting It With Better Military Setup, Sustained Will". Time. January 13, 1958. Archived from the original on January 4, 2013.

- ^ Teller & Shoolery 2001, pp. 420–421.

- ^ a b c d "In Memoriam: Edward Teller". University of California, Davis. Archived from the original on November 10, 2014. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- ^ Herken 2002, p. 330.

- ^ "Hertz Foundation Makes US$1 Million Endowment in Honor of Edward Teller" (Press release). UC Davis News Service. June 14, 1999. Retrieved November 24, 2007.

- ^ Teller & Shoolery 2001, pp. 552–555.

- ^ Matthews, M.A. (October 8, 1959). "The Earth's Carbon Cycle". New Scientist. 6: 644–646.

- ^ Benjamin Franta, "On its 100th birthday in 1959, Edward Teller warned the oil industry about global warming", The Guardian, January 1, 2018 (page visited on January 2, 2018).

- ^ Chance, Norman. "Project Chariot: The Nuclear Legacy of Cape Thompson, Alaska Norman Chance – Part 1". University of Connecticut. Archived from the original on September 21, 2015. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- ^ O'Neill 1994, pp. 97, 111.

- ^ Broad 1992, p. 48.

- ^ Chance, Norman. "Project Chariot: The Nuclear Legacy of Cape Thompson, Alaska Norman Chance – Part 2". University of Connecticut. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- ^ Loreto, Frank (April 26, 2002). "Review of Nuclear Dynamite". CM. Vol. 8, no. 17. University of Manitoba. Archived from the original on October 15, 2002.

- ^ Clearwater, John (1998). "Canadian Nuclear Weapons". Dundurn Press (Toronto). Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved January 30, 2011.

- ^ "Nuke Hurricanes, Teller Proposes". The Orlando Sentinel. June 9, 1990. Retrieved July 8, 2021.

- ^ Karpin 2005, pp. 289–293.

- ^ Gábor Palló (2000). "The Hungarian Phenomenon in Israeli Science" (PDF). Bull. Hist. Chem. 25 (1): 35–42. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ^ a b Cohen 1998, pp. 297–300.

- ^ UPI (December 6, 1982). "Edward Teller in Israel To Advise on a Reactor". The New York Times. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ^ Goodchild 2004, p. 327.

- ^ "I was the only victim of Three-Mile Island". Chicago Tribune. October 17, 1979.

- ^ Gwynne, Peter (September 21, 1987). "Teller on SDI, Competitiveness". The Scientist.

- ^ Scheer, Robert (July 17, 1988). "The Man Who Blew the Whistle on 'Star Wars': Roy Woodruff's Ordeal Began When He Tried to Turn the Vision of an X-ray Laser into Reality". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- ^ "Edward Teller: the Man Behind the Myth". The Truth Seeker. September 15, 2003. Archived from the original on July 30, 2020. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- ^ Bethe, Hans; Garwin, Richard; Gottfried, Kurt (October 1, 1984). "Space-Based Ballistic-Missile Defense". Scientific American. 251 (4): 39. Bibcode:1984SciAm.251d..39B. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1084-39. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- ^ Wang, C. P. (Ed.), Proceedings of the International Conference on Lasers '85 (STS, McLean, Va, 1986).

- ^ Duarte, F. J. (Ed.), Proceedings of the International Conference on Lasers '87 (STS, McLean, Va, 1988).

- ^ a b Planetary defense workshop LLNL 1995

- ^ a b Jason Mick (October 17, 2013). "The mother of all bombs would sit in wait in an orbitary platform". Archived from the original on October 9, 2014.

- ^ a b "A new use for nuclear weapons: hunting rogue asteroids". Center for Public Integrity. October 16, 2013. Archived from the original on March 20, 2016.

- ^ Goodchild 2004, p. 394.

- ^ This quote has been primarily attributed to Rabi in many news sources (see, e.g., McKie, Robin (May 2, 2004). "Megaton megalomaniac". The Observer. but in a few reputable sources it has also been attributed to Hans Bethe (i.e. in Herken 2002, notes to the Epilogue.

- ^ "About Us". World Cultural Council. Retrieved November 8, 2016.

- ^ "Edward Teller". www.nasonline.org.

- ^ "About the lab:Edward Teller – A Life Dedicated to Science". Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. January 7, 2004. Archived from the original on April 18, 2008. Retrieved November 28, 2007.

- ^ "APS Fellow Archive". American Physical Society. (search on year=1936 and institution=George Washington University)

- ^ "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ "SES Medallists". Society of Engineering Science. Archived from the original on October 8, 2015. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- ^ "Hungarians recognize H-bomb physicist Teller". Deseret News. August 16, 2001. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- ^ "Time Person of the year, 1960: U.S. Scientists". TIME. January 2, 1961. Archived from the original on May 5, 2007. Retrieved November 28, 2007.

- ^ "The Ames Astrogram: Teller visits Ames" (PDF). NASA. November 27, 2000. p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved November 28, 2007.

- ^ Ritholtz, Barry (March 7, 2012). Motherboard TV: Doctor Teller's Strange Loves, from the Hydrogen Bomb to Thorium Energy. Motherboard TV. Retrieved November 16, 2015.

- ^ Moir, Ralph; Teller, Edward (2005). "Thorium-Fueled Underground Power Plant Based on Molten Salt Technology". Nuclear Technology. 151 (3). American Nuclear Society: 334–340. Bibcode:2005NucTe.151..334M. doi:10.13182/NT05-A3655. S2CID 36982574. Archived from the original on April 4, 2013. Retrieved March 22, 2012.

- ^ "Material on Teller's last paper to consider for the Edward Teller Centennial. Edward Tellr – Ralph Moir 2007" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

- ^ Thomas, Michael (July 19, 2023). "'Oppenheimer' Cast and Character Guide: Who's Who in Christopher Nolan's Historical Epic". Collider. Retrieved July 21, 2023.

- ^ Selove, Walter (1958). "Review of Our Nuclear Future: Facts, dangers and opportunities by Edward Teller and Albert L. Latter". Science. 127 (3305): 1042. doi:10.1126/science.127.3305.1042.b. S2CID 239881549.

- ^ Frisch, David (1962). "Review of The Legacy of Hiroshima by Edward Teller and Allen Brown". Physics Today. 15 (7): 50–51. Bibcode:1962PhT....15g..50T. doi:10.1063/1.3058270.

- ^ "Mini-review of The Legacy of Hiroshima by Edward Teller and Allen Brown". Naval War College Review. 15 (6): 40. September 1962.

- ^ Bernstein, Barton J. (1990). "Reviewed work: Better a Shield Than a Sword: Perspectives on Defense and Technology by Edward Teller". Technology and Culture. 31 (4): 846–861. doi:10.2307/3105912. JSTOR 3105912. S2CID 115370103.

- ^ "Review of Conversations on the Dark Secrets of Physics by Edward Teller with Wendy Teller and Wilson Talley". Publishers Weekly. January 1, 2000.

- ^ Borcherds, P. (2003). "Review of Conversations on the Dark Secrets of Physics by Edward Teller with Wendy Teller and Wilson Talley". European Journal of Physics. 24 (4): 495–496. doi:10.1088/0143-0807/24/4/702. S2CID 250893374.

- ^ Dyson, Freeman J. (2002). "Review of Memoirs: A Twentieth-Century Journey in Science and Politics by Edward Teller with Judith Shoolery". American Journal of Physics. 70 (4): 462–463. Bibcode:2002AmJPh..70..462T. doi:10.1119/1.1456079.

Sources

- Blumberg, Stanley; Panos, Louis (1990). Edward Teller: Giant of The Golden Age of Physics. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company. ISBN 0684190427.

- Broad, William J. (1992). Teller's War: The Top-Secret Story Behind the Star Wars Deception. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0671701061.

- Brown, Gerald E.; Lee, Sabine (2009). Hans Albrecht Bethe (PDF). Biographical Memoirs. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences.

- Cohen, Avner (1998). Israel and the bomb. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231104838.

- Dash, Joan (1973). A Life of One's Own: Three Gifted Women and the Men They Married. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0060109493. OCLC 606211.

- Goncharov, German (2005). "The Extraordinarily Beautiful Physical Principle of Thermonuclear Charge Design (on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the test of RDS-37 – the first Soviet two-stage thermonuclear charge". Physics-Uspekhi. 48 (11): 1187–1196. Bibcode:2005PhyU...48.1187G. doi:10.1070/PU2005v048n11ABEH005839. S2CID 250820514. Russian text (free download)

- Goodchild, Peter (2004). Edward Teller: The Real Dr. Strangelove. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674016699.

- Gorelik, Gennady (2009). "The Paternity of the H-Bombs: Soviet-American Perspectives". Physics in Perspective. 11 (2): 169–197. Bibcode:2009PhP....11..169G. doi:10.1007/s00016-007-0377-8. S2CID 120853984.

- Herken, Gregg (2002). Brotherhood of the Bomb: The Tangled Lives and Loyalties of Robert Oppenheimer, Ernest Lawrence, and Edward Teller. New York: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 0805065881.

- Hoddeson, Lillian; Henriksen, Paul W.; Meade, Roger A.; Westfall, Catherine L. (1993). Critical Assembly: A Technical History of Los Alamos During the Oppenheimer Years, 1943–1945. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521441323. OCLC 26764320.

- Karpin, Michael (2005). The Bomb in the Basement. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0743265955.

- O'Neill, Dan (1994). The Firecracker Boys. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0312110863.

- Rhodes, Richard (1986). The Making of the Atomic Bomb. London: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0671441337.

- Rhodes, Richard (1995). Dark Sun: The Making of the Hydrogen Bomb. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 068480400X.

- Teller, Edward; Shoolery, Judith L. (2001). Memoirs: A Twentieth-Century Journey in Science and Politics. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Perseus Publishing. ISBN 073820532X.

- Thorpe, Charles (2006). Oppenheimer: The Tragic Intellect. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226798453.

- Ulam, S. M (1983). Adventures of a Mathematician. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 978-0684143910. OCLC 1528346.

Further reading

- Stanley A. Blumberg and Louis G. Panos. Edward Teller : Giant of the Golden Age of Physics; a Biography (Scribner's, 1990)

- Istvan Hargittai, Judging Edward Teller: a Closer Look at One of the Most Influential Scientists of the Twentieth Century (Prometheus, 2010).

- Carl Sagan writes at length about Teller's career in chapter 16 of his book The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark (Headline, 1996), p. 268–274.

- Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory's Science and Technology Review contains 10 articles written primarily by Stephen B. Libby in 2007, about Edward Teller's life and contributions to science, to commemorate the 2008 centennial of his birth.

- Heisenberg Sabotaged the Atomic Bomb (Heisenberg hat die Atombombe sabotiert) an interview in German with Edward Teller in: Michael Schaaf: Heisenberg, Hitler und die Bombe. Gespräche mit Zeitzeugen Berlin 2001, ISBN 3928186604.

- Coughlan, Robert (September 6, 1954). "Dr. Edward Teller's Magnificent Obsession". Life. Retrieved January 29, 2019.

- Szilard, Leo. (1987) Toward a Livable World: Leo Szilard and the Crusade for Nuclear Arms Control. Cambridge: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0262192606

External links

- 1986 Audio Interview with Edward Teller by S. L. Sanger Voices of the Manhattan Project

- Annotated Bibliography for Edward Teller from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

- "Edward Teller's Role in the Oppenheimer Hearings" interview with Richard Rhodes

- Edward Teller Biography and Interview on American Academy of Achievement

- A radio interview with Edward Teller Aired on the Lewis Burke Frumkes Radio Show in January 1988.

- The Paternity of the H-Bombs: Soviet-American Perspectives Archived June 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Edward Teller tells his life story at Web of Stories (video)

- Works by Edward Teller at Project Gutenberg

- Edward Teller

- 1908 births

- 2003 deaths

- 20th-century Hungarian physicists

- Academic staff of the University of Göttingen

- American agnostics

- American amputees

- American nuclear physicists

- American people of Hungarian-Jewish descent

- American scientists with disabilities

- Enrico Fermi Award recipients

- Fasori Gimnázium alumni

- Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- Fellows of the American Association for the Advancement of Science

- Fellows of the American Physical Society

- Founding members of the World Cultural Council

- George Washington University faculty

- Hungarian agnostics

- Hungarian amputees

- Hungarian emigrants to the United States

- Hungarian Jews

- Israeli nuclear development

- Jewish agnostics

- Jewish American physicists

- Jewish emigrants from Nazi Germany to the United States

- Karlsruhe Institute of Technology alumni

- Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory staff

- Leipzig University alumni

- Manhattan Project people

- Members of the International Academy of Quantum Molecular Science

- Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences

- National Medal of Science laureates

- Nuclear proliferation

- Scientists from Budapest

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- Theoretical physicists

- Time Person of the Year

- University of California, Berkeley faculty

- University of Chicago faculty

- American Zionists