Bahrain

Kingdom of Bahrain مملكة البحرين Mamlakat al-Baḥrayn | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: Bahrainona | |

![Location of Bahrain (green) in the Middle East (grey) – [Legend]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/83/Map_of_Bahrain.svg/250px-Map_of_Bahrain.svg.png) Location of Bahrain (green) in the Middle East (grey) – [Legend] | |

| Capital and largest city | Manama |

| Official languages | Arabic |

| Demonym(s) | Bahraini |

| Government | Constitutional monarchy |

• King | Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa |

| Salman bin Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa | |

| Khalifa bin Salman Al Khalifa | |

| Legislature | National Assembly |

| Consultative Council | |

| Council of Representatives | |

| Independence | |

• From Persia | 1783 |

• Termination of special treaty with the United Kingdom | 15 August 1971 |

| Area | |

• Total | 765.3 km2 (295.5 sq mi) (190th) |

• Water (%) | 0 |

| Population | |

• 2010 estimate | 1,234,571[1] (155th) |

• Density | 1,626.6/km2 (4,212.9/sq mi) (7th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2011 estimate |

• Total | $31.101 billion[2] (91st) |

• Per capita | $27,556[2] (33rd) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2011 estimate |

• Total | $26.108 billion[2] (91st) |

• Per capita | $23,132[2] (33rd) |

| HDI (2011) | Error: Invalid HDI value (42nd) |

| Currency | Bahraini dinar (BHD) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (AST) |

| Drives on | Right |

| Calling code | 973 |

| ISO 3166 code | BH |

| Internet TLD | .bh |

Bahrain () (Arabic: البحرين, al-Baḥrayn) (Persian: بحرين, Baḥrain), officially the Kingdom of Bahrain (Arabic: مملكة البحرين, ), is a small island country situated near the western shores of the Persian Gulf. It is an archipelago of 33 islands, the largest being Bahrain Island, at 55 km (34 mi) long by 18 km (11 mi) wide. Saudi Arabia lies to the west and is connected to Bahrain by the King Fahd Causeway. Iran lies 200 km (120 mi)* to the north of Bahrain, across the Gulf. The peninsula of Qatar is to the southeast across the Gulf of Bahrain. The planned Qatar Bahrain Causeway will link Bahrain and Qatar and become the world's longest marine causeway.[4] The population in 2010 stood at 1,234,571, including 666,172 non-nationals.[1]

Bahrain is believed to be the site of the ancient land of the Dilmun civilisation. Bahrain came under the rule of successive Persian empires, the Parthians and Sassanians empires respectively. Bahrain was one of the earliest areas to convert to Islam in 628 AD. Following a successive period of Arab rule, the country was occupied by the Portuguese in 1521. The Portuguese were later expelled, in 1602, by Shah Abbas I of the Safavid empire. In 1783, the Bani Utbah tribe captured Bahrain from the Persians and was ruled by the Al Khalifa royal family since, with Ahmed al Fateh being the first hakim of Bahrain. In the late 1800s, following successive treaties with the British, Bahrain became a protectorate of the United Kingdom. Following the withdrawal of the British from the region in the late 1960s, Bahrain declared independence in 1971. Formerly an emirate, Bahrain was declared a kingdom in 2002.

Bahrain today has a very high Human Development Index (42nd highest in the world) and the World Bank identified it as a high income economy. Bahrain is also a member of the United Nations, World Trade Organisation, the Arab League, the Non-Aligned Movement, the Organization of the Islamic Conference as well as being a founding member of the Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf.[5] Bahrain was also designated as a major non-NATO ally by the George W. Bush administration in 2001.[6]

Oil was discovered in Bahrain in 1932 (the first in the Arabian side of the Gulf). In recent decades, Bahrain has sought to diversify its economy and be less dependent on oil by investing in the banking sector and tourism.[7] The country's capital, Manama, is home to many large financial structures, including the Bahrain World Trade Center and the Bahrain Financial Harbour, with a proposal in place to build the 1,022 m (3,353 ft) high Murjan Tower. The Qal'at al-Bahrain (the harbour and capital of the ancient land of Dilmun) was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2005.[8] The Bahrain Formula One Grand Prix takes place at the Bahrain International Circuit.[9]

Since 2011, the government of Bahrain has faced a series of massive demonstrations, amounting to a sustained campaign of civil unrest, also known as the 2011–2012 Bahraini uprising, and has faced widespread criticism for its crackdown on protestors which has resulted in about 95 deaths.

Etymology

In Arabic, bahrayn is the dual form of bahr ("sea"), so al-Bahrayn means "the Two Seas". However, which two seas were originally intended remains in dispute.[10] The term appears five times in the Qur'an, but does not refer to the modern island—originally known to the Arabs as "Awal"—but rather to the oases of al-Katif and Hadjar (modern al-Hasa).[10] It is unclear when the term began to refer exclusively to the Awal islands, but it was probably after the 15th century.

Today, al-Hasa belongs to Saudi Arabia and Bahrain's "two seas" are instead generally taken to be the bay east and west of the island,[11] the seas north and south of the island,[12] or the salt and fresh water present above and below the ground.[13] In addition to wells, there are places in the sea north of Bahrain where fresh water bubbles up in the middle of the salt water, noted by visitors since antiquity.[14]

An alternate theory offered by al-Ahsa was that the two seas were the Great Green Ocean and a peaceful lake on the Arabian mainland; still another provided by al-Jawahari is that the more formal name Bahri (lit. "belonging to the sea") would have been misunderstood and so was opted against.[13]

History

Pre-Islamic period

Inhabited since ancient times, Bahrain occupies a strategic location in the Persian Gulf. It is the best natural port between the mouth of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers and Oman, a source of copper in ancient times. Bahrain may have been associated with Dilmun, an important Bronze age trade centre linking Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley.[15] It has been ruled by the Assyrians,[16] Babylonians,[17] Persians,[18] and then Arabs, under whom the island became first Christian and then Islamic.

From the 6th to 3rd century BC, Bahrain was added to the Persian Empire by the Achaemenian dynasty. By about 250 BC, the Parthians brought the Persian Gulf under its control and extended its influence as far as Oman. During the classical era, the island was known as Tylos in Europe. In order to control trade routes, the Parthians established garrisons along the southern coast of the Persian Gulf.[19] In the 3rd century, Ardashir I, the first ruler of the Sassanid dynasty, marched on Oman and Bahrain, where he defeated Sanatruq the ruler of Bahrain.[20] At this time, Bahrain comprised the southern Sassanid province along with the Persian Gulf's southern shore.[21]

The Sassanid Empire divided their southern province into the three districts of Haggar (now al-Hafuf province in Saudi Arabia), Batan Ardashir (now al-Qatif province in Saudi Arabia) and Mishmahig (which in Middle-Persian/Pahlavi means "ewe-fish").[20] Early Islamic sources describe the country as inhabited by members of the Abdul Qais,[22] Tamim, and Bakr tribes who worshipped the idol Awal, from which the Arabs named the island of Bahrain Awal for many centuries. However, Bahrayn was also a center of Nestorian Christianity, including two of its bishoprics.[20]

Islamic conversion, Iranian dynasties, and Portuguese control

Traditional Islamic accounts state that Al-ʿAlāʾ Al-Haḍrami was sent as an envoy to the Bahrain region by the prophet Muhammad in AD 628 and that Munzir ibn-Sawa al-Tamimi, the local ruler, responded to his mission and converted the entire area.[23][24]

In 899 AD, the Qarmatians, a millenarian Ismaili Muslim sect seized Bahrain, seeking to create a utopian society based on reason and redistribution of property among initiates. Thereafter, the Qarmatians demanded tribute from the caliph in Baghdad, and in 930 AD sacked Mecca and Medina, bringing the sacred Black Stone back to their base in Ahsa, in medieval Bahrain, for ransom. According to historian Al-Juwayni, the stone was returned 22 years later in 951 under mysterious circumstances. Wrapped in a sack, it was thrown into the Great Mosque of Kufa in Iraq, accompanied by a note saying "By command we took it, and by command we have brought it back." The theft and removal of the Black Stone caused it to break into seven pieces.[20][25][26]

Following a 976 AD defeat by the Abbasids,[27] the Quarmations were overthrown by the Arab Uyunid dynasty of al-Hasa, who took over the entire Bahrain region in 1076.[28] The Uyunids controlled Bahrain until 1235, when the archipelago was briefly occupied by the Iranian ruler of Fars. In 1253, the Bedouin Usfurids brought down the Uyunid dynasty, thereby gaining control over eastern Arabia, including the islands of Bahrain. In 1330, the archipelago became a tributary state of the rulers of Hormuz,[29] though locally the islands were controlled by the Shi'ite Jarwanid dynasty of Qatif.[30]

Until the late Middle Ages, "Bahrain" referred to the larger historical region of Bahrain that included Al-Ahsa, Al-Qatif (both now within the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia) and the Awal Islands (now the Bahrain Islands). The region stretched from Basra in Iraq to the Strait of Hormuz in Oman. This was Iqlīm al-Bahrayn's "Bahrayn Province". The exact date at which the term "Bahrain" began to refer solely to the Awal archipelago is unknown.[31] In the mid-15th century, the archipelago came under the rule of the Jabrids, a Bedouin dynasty also based in Al-Ahsa that ruled most of eastern Arabia.

In 1521, the Portuguese allied with Hormuz and seized Bahrain from the Jabrid ruler Migrin ibn Zamil, who was killed during the takeover. Portuguese rule lasted for around 80 years, during which time they depended mainly on Sunni Persian governors.[32] The Portuguese were expelled from the islands in 1602 by Abbas I of the Safavid dynasty of Iran, who declared Shia Islam the official religion of Bahrain.[33] For the next two centuries, Iranian rulers retained control of the archipelago, interrupted by the 1717 and 1738 invasions of the Ibadhis of Oman.[34][35] During most of this period, they resorted to governing Bahrain indirectly, either through the city of Bushehr or through immigrant Sunni Arab clans. The latter were tribes returning to the Arabian side of the Persian Gulf from Persian territories in the north who were known as Huwala (literally: those that have changed or moved).[32][36][37] In 1753, the Huwala clan of Nasr Al-Madhkur invaded Bahrain on behalf of the Iranian Zand leader Karim Khan Zand and restored direct Iranian rule.[37]

Rise of the Bani Utbah

In 1783, Nasr Al-Madhkur, ruler of Bahrain and Bushire, lost the islands of Bahrain following his defeat by the Bani Utbah tribe at the 1782 Battle of Zubarah. Bahrain was not new territory to the Bani Utbah; they had been a presence there since the 17th century.[38] During that time, they started purchasing date palm gardens in Bahrain. A document belonging to Shaikh Salama Bin Saif Al Utbi, one of the shaikhs of the Al Bin Ali tribe (an offshoot of the Bani Utbah), states that Mariam Bint Ahmed Al Sindi, a Shia woman, sold a palm garden on the island of Sitra to Shaikh Salama Bin Saif Al Utbi in the year 1699–1111 Hijri calendar, preceding the arrival of the Al-Khalifa to Bahrain by 81 years.[39]

The Al Bin Ali were the dominant group controlling the town of Zubarah on the Qatar peninsula,[40][41] originally the center of power of the Bani Utbah. After the Bani Utbah gained control of Bahrain, the Al Bin Ali had a practically independent status there as a self-governing tribe. They used a flag with four red and three white stripes, called the Al-Sulami flag[42] in Bahrain, Qatar, Kuwait, and the Eastern province of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. It was raised on their ships during wartime, in the pearl season and on special occasions such as weddings and during Eid ul-Fitr as well as in the "Ardha of war".[43] The Al Bin Ali were known for their courage, persistence, and abundant wealth.[44]

Later, different Arab family clans and tribes from Qatar moved to Bahrain to settle after the fall of Nasr Al-Madhkur of Bushehr. These families and tribes included the Al Khalifa, Al-Ma'awdah, Al-Fadhil, Al-Mannai, Al-Noaimi, Al-Sulaiti, Al-Sadah, Al-Thawadi, and other families and tribes.[45]

Al Khalifa ascendancy to Bahrain and their treaties with the British

In 1797, fourteen years later after gaining the power of the Bani Utbah, the Al Khalifa family moved to Bahrain and settled in Jaww, later moving to Riffa. They were originally from Kuwait having left in 1766. Al-Sabah family traditions relates that the ancestors of their tribe and those of the Al-Khalifa tribe came to Kuwait after their expulsion from Umm Qasr upon Khor Zubair by the Turks, an earlier base from which they preyed on the caravans of Basra and pirated ships in the Shatt al-Arab waterway.[46]

In the early 19th century, Bahrain was invaded by both the Omanis and the Al Sauds. In 1802 it was governed by a twelve year old child, when the Omani ruler Sayyid Sultan installed his son, Salim, as Governor in the Arad Fort.[47]

In 1820, the Al Khalifa tribe regained power in Bahrain and entered a treaty relationship with Great Britain, by then the dominant military power in the Persian Gulf. This treaty recognised the Al Khalifa as the rulers ("Al-Hakim" in Arabic) of Bahrain. [48] After the Egyptian ruler, Mohammad Ali Pasha took the Arabian Peninsula from the Wahhabis on behalf of the Ottoman Empire in 1830, the Egyptian army demanded yearly tributes from Sheikh Abdul Al Khalifa. He had earlier sought Persian and British protection from the Egyptians. [49] The Sheikh agreed to the terms of the Egyptians.

In 1860, the Government of Al Khalifa used the same tactic when the British tried to overpower Bahrain. Sheikh Mohammad bin Khalifa Al Khalifa wrote letters to both the Persian Prince-Governor of Fars and to the Ottoman Wali of Baghdad, to place Bahrain in the protection of each respective state.[49] Both sides sent wakils (a person who is an authorised repesentative), who offered the Sheikh their conditions, of which the Ottoman terms were more beneficial and was accepted in March, 1860.[49] In another letter to the Iranian Foreign Minister, Sheikh Mohammad demanded that the Government of Iran provide direct guidance and protection from British pressure. [49]

Later on, under pressure from Colonel Sir Lewis Pelly, Sheikh Mohammad requested military assistance from Iran, but the Government of Iran at that time provided no aid to protect Bahrain from British aggression.[49] As a result the Government of British India eventually overpowered Bahrain.[49] Colonel Pelly signed an agreement with Sheikh Mohammad in May 1861 and later with his brother Sheikh Ali that placed Bahrain under British rule and protection.[49]

In 1868, following the Qatari–Bahraini War, British representatives signed another agreement with the Al Khalifa rulers, making Bahrain part of the British protectorate territories in the Persian Gulf. It specified that the ruler could not dispose of any of his territory except to the United Kingdom and could not enter into relationships with any foreign government without British consent.[50] [51] In return the British promised to protect Bahrain from all aggression by sea and to lend support in case of land attack.[51] More importantly the British promised to support the rule of the Al Khalifa in Bahrain, securing its unstable position as rulers of the country. Other agreements in 1880 and 1892 sealed the protectorate status of Bahrain to the British.[51]

Unrest amongst the people of Bahrain began when Britain officially established complete dominance over the territory in 1892. The first revolt and widespread uprising took place in March 1895 against Sheikh Issa bin Ali, then ruler of Bahrain.[52] Sheikh Issa was the first of the Al Khalifa to rule without Iranian relations. Sir Arnold Wilson, Britain's representative in the Persian Gulf and author of The Persian Gulf, arrived in Bahrain from Mascat at this time.[52] The uprising developed further with some protesters killed by British forces.[52]

Early 20th Century reforms

In 1911, a group of Bahraini merchants demanded restrictions on the British influence in the country. The group's leaders were subsequently arrested and exiled to India. In 1923, the British deposed Sheikh Issa bin Ali whom they accused of opposing Britain and set up a permanent representative in Bahrain. This coincided with renewal of Iran's claim over the ownership of Bahrain, a development that Sheikh Issa had been accused of welcoming. The preference shown by the people of Bahrain towards the renewal of Iran ownership's claim also caused concern for Britain. To remedy these problems, in 1926, Britain dispatched Sir Charles Belgrave, one of her most experienced colonial officers, as an advisor to the Ruler of Bahrain. His harsh measures intensified the increasing aversion of people towards him and led to his eventual expulsion from Bahrain in 1957. Belgrave's colonial undertakings were not limited to violent deeds against Bahrainis but also included a series of initiatives that included removal of Iranian influence on Bahrain and the Persian Gulf. In 1937, Belgrave proposed changing the name of the Persian Gulf to the "Gulf of Arabia", a move that did not take place.[53]

In 1927, Rezā Shāh demanded the return of Bahrain in a letter to the League of Nations. Britain believed that weakened domination over Bahrain would cause her to lose control all over the Persian Gulf, and decided to bring uprisings amongst the people of Bahrain under control at any cost. To achieve this they encouraged conflicts between Shiite and Sunni Muslims in Bahrain.[54]

Bahrain underwent a period of major social reform between 1926 and 1957, under the de facto rule of Charles Belgrave, the British advisor to Shaikh Hamad ibn Isa Al Khalifa (1872–1942). The country's first modern school, the Al-Hiddaya Boys School, was established in 1919, whilst the Gulf's first girls' school opened in 1928.[55] The American Mission Hospital, established by the Dutch Reformed Church, began work in 1903. Other reforms included the abolition of slavery. At the same time, the pearl diving industry developed at a rapid pace.

These reforms were often vigorously opposed by powerful groups within Bahrain including sections within the ruling family, tribal forces, the religious authorities and merchants. In order to counter conservatives, the British removed the Ruler, Isa ibn Ali Al Khalifa in 1923 and replaced him with his son. Some Sunni tribes such as the al Dossari left Bahrain to mainland Arabia, whilst clerical opponents of social reforms were exiled to Saudi Arabia and Iran. The heads of some merchant and notable families were likewise exiled.[56] Britain's interest in Bahrain's development was motivated by concerns over the ambitions of the Saudi-Wahabi and the Iranians.

Discovery of petroleum

The discovery of oil in 1932 by Bahrain Petroleum Company[57] brought rapid modernisation to Bahrain. Relations with the United Kingdom became closer, as evidenced by the British Royal Navy moving its entire Middle Eastern command from Bushehr in Iran to Bahrain in 1935.[58] British influence continued to grow as the country developed, culminating with the appointment of Charles Belgrave as advisor.[59] He went on to establish a modern education system in Bahrain.[59]

Bahrain participated in the Second World War on the Allied side, joining on the 10th of September, 1939. On the 19th of October, 1940, four Italian SM.82s bombers bombed Bahrain alongside Dhahran oilfields in Saudi Arabia,[60] targeting Allied-operated oil refineries.[61] Although minimal damage was caused in both locations, the attack forced the Allies to upgrade Bahrain's defences which further stretched Allied military resources. After World War II, increasing anti-British sentiment spread throughout the Arab World and led to riots in Bahrain. The riots focused on the Jewish community, which included distinguished writers, singers, accountants, engineers and middle managers working for the oil company, textile merchants with business all over the peninsula, and free professionals.

In 1948, following rising hostilities and looting,[62] most members of Bahrain's Jewish community abandoned their properties and evacuated to Bombay, later settling in Israel (Pardes Hanna-Karkur) and the United Kingdom. As of 2008, 37 Jews remained in the country.[62] The issue of compensation was never settled. In 1960, the United Kingdom put forward Bahrain's future for international arbitration and requested that the United Nations Secretary-General take on this responsibility.

Drop of Iranian claim

Iran's parliament passed a bill in November 1957 declaring Bahrain to be the 14th province of Iran,[63] with two empty seats allocated for its representatives. This action caused numerous problems for Iran in its international relations, especially with some United Nations bodies, Britain, Saudi Arabia, and a number of Arab countries.[64]

At this time, Britain set out to change the demographics of Bahrain. The policy of “deiranisation” consisted of importing a large number of different Arabs and others from British colonies as labourers.[65]

In 1965 Britain began dialogue with Iran to determine their borders in the Persian Gulf. Before long extensive differences over borders and territory came to light, including the dispute over the dominion of Bahrain. The two were not able to determine the maritime borders between the northern and southern countries of the Persian Gulf. At the same time King Faisal of Saudi Arabia arrived in Iran on a visit which included the creation of Islamic Conference and the decision to determine the maritime borders of the two countries. In return, the Shah of Iran agreed to visit Saudi Arabia in 1967. A week before this visit, the Saudis received Sheikh Isa bin Salman Al Khalifa, the that time Ruler of Bahrain as a head of state in the Saudi capital Riyadh. As a result the Shah's visit was cancelled, seriously damaging relations between the two countries. Following mediation by King Hassan II of Morocco, the relationship was repaired.[66]

Eventually Iran and Britain agreed to put the matter of Dominion of Bahrain to international judgment and requested the United Nations General Secretary take on this responsibility.[67][68]

Iran pressed hard for a referendum in Bahrain in the face of strong opposition from both the British and the Bahraini leaders.[65] Their opposition was based on Al Khalifa's view that such a move would negate 150 years of their clan's rule in the country. In the end, as an alternative to the referendum, Iran and Britain agreed to request the United Nations conduct an opinion poll in Bahrain that would determine the political future of the territory. In reply to letters from the British and Iranians, U Thant, then Secretary General of the United Nations, declared that the poll would take place on 30 March 1970. Vittorio Winspeare-Giucciardi, Manager of the United Nations office in Geneva was put in charge of the project. Report no. 9772 was submitted to the UN General Secretary and on 11 May 1970, the United Nations Security Council endorsed Winspeare's conclusion that an overwhelming majority of the people wished recognition of Bahrain's identity as a fully independent and sovereign state free to decide its own relations with other states.[69] Both Britain and Iran accepted the report and brought their dispute to a close.[70]

Independence

On 15 August 1971, Bahrain declared independence and signed a new treaty of friendship with the United Kingdom. Bahrain joined the United Nations and the Arab League later in the year. [71] The oil boom of the 1970s benefited Bahrain greatly, although the subsequent downturn hurt the economy. The country had already begun diversification of its economy and benefited further from the 1970s Lebanese Civil War, when Bahrain replaced Beirut as the Middle East's financial hub after Lebanon's large banking sector was driven out of the country by the war.[72] Following the 1979 Islamic revolution in Iran, in 1981 Bahraini Shī'a fundamentalists orchestrated a failed coup attempt under the auspices of a front organisation, the Islamic Front for the Liberation of Bahrain. The coup would have installed a Shī'a cleric exiled in Iran, Hujjatu l-Islām Hādī al-Mudarrisī, as supreme leader heading a theocratic government.[73] In 1994, a wave of rioting by disaffected Shīa Islamists was sparked by women's participation in a sporting event.[74]

The 1990s Uprising in Bahrain occurred in Bahrain between 1994 and 2000 in which leftists, liberals and Islamists joined forces.[75] The event resulted in approximately forty deaths and ended after Hamad ibn Isa Al Khalifa became the Emir of Bahrain in 1999.[76] A referendum on 14–15 February 2001 massively supported the National Action Charter.[77] He instituted elections for parliament, gave women the right to vote, and released all political prisoners. These moves were described by Amnesty International as representing an "historic period of human rights".[78] As part of the adoption of the National Action Charter on 14 February 2002, Bahrain changed its formal name from the State (dawla) of Bahrain to the Kingdom of Bahrain.[79]

The country participated in military action against the Taliban in October 2001 by deploying a frigate in the Arabian Sea for rescue and humanitarian operations.[80] As a result, in November of that year , US president George W. Bush's administration designated Bahrain as a "major non-NATO ally".[80] Bahrain opposed the invasion of Iraq and had offered Saddam Hussein asylum in the days prior to the invasion.[80] Relations improved with neighbouring Qatar after the border dispute over the Hawar Islands was resolved by the International Court of Justice in The Hague in 2001. Following the political liberalization Bahrain negotiated a free trade agreement with the United States in 2004.[81]

2011–2012 Bahraini uprising

The protests in Bahrain started on 14 February, and were initially aimed at achieving greater political freedom and respect for human rights; they were not intended to directly threaten the monarchy.[82][83]: 162–3 Lingering frustration among the Shiite majority with being ruled by the Sunni government was a major root cause, but the protests in Tunisia and Egypt are cited as the inspiration for the demonstrations.[82][83]: 65 The protests were largely peaceful until a pre-dawn raid by police on 17 February to clear protestors from Pearl Roundabout in Manama, in which police killed four protesters.[83]: 73–4 Following the raid, some protesters began to expand their aims to a call for the end of the monarchy.[84] On 18 February army forces opened fire on protesters when they tried to reenter the roundabout, fatally wounding one.[83]: 77–8 The following day protesters reoccupied Pearl Roundabout after the government ordered troops and police to withdraw.[83]: 81 [85] Subsequent days saw large demonstrations; on 21 February a pro-government Gathering of National Unity drew tens of thousands,[83]: 86 [86] whilst on 22 February the number of protestors at the Pearl Roundabout peaked at over 150,000 after more than 100,000 protesters marched there.[83]: 88 On 14 March, Saudi-led GCC forces were requested by the government and entered the country,[83]: 132 which the opposition called an "occupation".[87]

King Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa declared a three-month state of emergency on 15 March and asked the military to reassert its control as clashes spread across the country.[83]: 139 [82] On 16 March, armed soldiers and riot police cleared the protesters' camp in the Pearl Roundabout, in which 3 policemen and 3 protesters were reportedly killed.[83]: 133–4 [88] Later, on 18 March, the government tore down Pearl Roundabout monument.[83]: 150 [89] After the lifting of emergency law on 1 June,[90] several large rallies were staged by the opposition parties.[91] Smaller-scale protests and clashes outside of the capital have continued to occur almost daily.[92][93] On 9 March 2012 over 100,000 protested in what the opposition called "the biggest march in our history".[94][95]

The police response has been described as a "brutal" crackdown on peaceful and unarmed protestors, including doctors and bloggers.[96][97][98] The police carried out midnight house raids in Shia neighbourhoods, beatings at checkpoints, and denial of medical care in a "campaign of intimidation".[99] [100][101][102] More than 2,929 people have been arrested,[103][104] and at least five people died due to torture while in police custody.[83]: 287,288 On 23 November 2011 the Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry released its report on its investigation of the events, finding that the government had systematically tortured prisoners and committed other human rights violations.[83]: 415–422 It also rejected the government's claims that the protests were instigated by Iran.[105] Although the report found that systematic torture had stopped,[83]: 417 the Bahraini government has refused entry to several international human rights groups and news organizations, and delayed a visit by a UN inspector.[106][107]

Politics

Bahrain is a Constitutional monarchy headed by the King, Shaikh Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa; the head of government is the Prime Minister, Shaikh Khalīfa bin Salman al Khalifa, who is the uncle of the current king. Bahrain has a bicameral National Assembly (al-Jamiyh al-Watani) consisting of the Shura Council (Majlis Al-Shura) with 40 seats and the Council of Representatives (Majlis Al-Nuwab) with 40 seats. The 40 members of the Shura are appointed by the king. In the Council of Representatives, 40 members are elected by absolute majority vote in single-member constituencies to serve 4-year terms.[108]

The first round of voting in the 2006 parliamentary election took place on 25 November 2006, and in the second round Islamists hailed a huge election victory.[109]

The opening up of politics has seen big gains for both Shīa and Sunnī Islamists in elections, which have given them a parliamentary platform to pursue their policies.[110] This has meant parties launching campaigns to impose bans on female mannequins displaying lingerie in shop windows,[111] and the hanging of underwear on washing lines.[112]

Analysts of democratisation in the Middle East cite the Islamists' references to respect for human rights in their justification for these programmes as evidence that these groups can serve as a progressive force in the region.[113] Islamist parties have been particularly critical of the government's readiness to sign international treaties such as the United Nation's International Convention on Civil and Political Rights.[114] At a parliamentary session in June 2006 to discuss ratification of the Convention, Sheikh Adel Mouwda, the former leader of salafist party, Asalah, explained the party's objections: "The convention has been tailored by our enemies, God kill them all, to serve their needs and protect their interests rather than ours. This why we have eyes from the American Embassy watching us during our sessions, to ensure things are swinging their way".[115]

Both Sunnī and Shī'a Islamists suffered a setback in March 2006 when 20 municipal councillors, most of whom represented religious parties, went missing in Bangkok on an unscheduled stopover when returning from a conference in Malaysia.[116] After the missing councillors eventually arrived in Bahrain they defended their stay at the Radisson Hotel in Bangkok, telling journalists it was a "fact-finding mission", and explaining: "We benefited a lot from the trip to Thailand because we saw how they managed their transport, landscaping and roads".[117] Bahraini liberals have responded to the growing power of religious parties by organising themselves to campaign through civil society in order to defend basic personal freedoms from being legislated away. In November 2005, al Muntada, a grouping of liberal academics, launched "We Have A Right", a campaign to explain to the public why personal freedoms matter and why they need to be defended.[118]

Women's rights

Women's political rights in Bahrain saw an important step forward when women were granted the right to vote and stand in national elections for the first time in the 2002 election.[119] However, no women were elected to office in that year's polls. Instead, Shī'a and Sunnī Islamists dominated the election, collectively winning a majority of seats.[120] In response to the failure of women candidates, six were appointed to the Shura Council, which also includes representatives of the Kingdom's indigenous Jewish and Christian communities.[121] Dr. Nada Haffadh became the country's first female cabinet minister on her appointment as Minister of Health in 2004. The quasi-governmental women's group, the Supreme Council for Women, trained female candidates to take part in the 2006 general election. When Bahrain was elected to head the United Nations General Assembly in 2006 it appointed lawyer and women's rights activist Haya bint Rashid Al Khalifa President of the United Nations General Assembly, only the third woman in history to head the world body.[122] In the year 2000, the King created the Supreme Judicial Council[123][124] to regulate the country's courts and institutionalise the separation of the administrative and judicial branches of government;[125] the leader of this court is Mohammed Humaidan.

On 11–12 November 2005, Bahrain hosted the Forum for the Future, bringing together leaders from the Middle East and G8 countries to discuss political and economic reform in the region.[126] The near total dominance of religious parties in elections has given a new prominence to clerics within the political system, with the most senior Shia religious leader, Sheikh Isa Qassim, playing an extremely important role. According to one academic paper, "In fact, it seems that few decisions can be arrived at in Al Wefaq – and in the whole country, for that matter – without prior consultation with Isa Qassim, ranging from questions with regard to the planned codification of the personal status law to participation in elections".[127] In 2007, Al Wefaq-backed parliamentary investigations were credited with forcing the government to remove ministers who had frequently clashed with MPs: the Minister of Health, Dr. Nada Haffadh and the Minister of Information, Dr Mohammed Abdul Gaffar.[128]

Military

The kingdom has a small but well equipped military called the Bahrain Defence Force (BDF), numbering around 13,000 personnel.[129] The supreme commander of the Bahraini military is King Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa and the deputy supreme commander is the Crown Prince, Salman bin Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa. [130]

The BDF is primarily equipped with United States equipment, such as the F16 Fighting Falcon, F5 Freedom Fighter, UH60 Blackhawk, M60A3 tanks, and the ex-USS Jack Williams, an Oliver Hazard Perry class frigate renamed the RBNS Sabha. The Government of Bahrain has close relations with the United States, having signed a cooperative agreement with the United States Military and has provided the United States a base in Juffair since the early 1990s. This is the home of the headquarters for Commander, United States Naval Forces Central Command (COMUSNAVCENT) / United States Fifth Fleet (COMFIFTHFLT), and about 1500 United States and coalition military personnel.[131]

Foreign relations

Bahrain established bilateral relations with 190 countries worldwide.[132] As of 2012, Bahrain maintains a network of 25 embassies, 3 consulates and 4 permanent missions to the Arab League, United Nations and European Union respectively.[133] Bahrain also hosts 36 embassies. Bahrain plays a modest, moderating role in regional politics and adheres to the views of the Arab League on Middle East peace and Palestinian rights, it supports the two state solution.[134] Bahrain is also one of the founding members of the Gulf Cooperation Council.[135] Relations with Iran tend to be tense as a result of a failed coup in 1981 which Bahrain blames Iran for and occasional claims of Iranian sovereignty over Bahrain by ultra conservative elements in the Iranian public.[136] [137]

Governorates

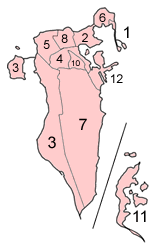

Prior to July 3, 2002, Bahrain was divided into 12 municipalities that are listed below:

| Map | Former Municipality |

|---|---|

| |

| 1. Al Hidd | |

| 2. Manama | |

| 3. Western Region | |

| 4. Central Region | |

| 5. Northern Region | |

| 6. Muharraq | |

| 7. Rifa and Southern Region | |

| 8. Jidd Haffs | |

| 9. Hamad Town (not shown) | |

| 10. Isa Town | |

| 11. Hawar Islands | |

| 12. Sitra |

Bahrain is currently split into five administrative governorates, each of which has its own governor.[138] These governorates are:

| Map | Governorates |

|---|---|

| |

| 1. Capital Governorate | |

| 2. Central Governorate | |

| 3. Muharraq Governorate | |

| 4. Northern Governorate | |

| 5. Southern Governorate |

Economy

According to a January 2006 report by the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia, Bahrain has the fastest growing economy in the Arab world.[139] Bahrain also has the freest economy in the Middle East and is twelfth freest overall in the world based on the 2011 Index of Economic Freedom published by the Heritage Foundation/Wall Street Journal, .[140]

In 2008, Bahrain was named the world's fastest growing financial center by the City of London's Global Financial Centres Index.[139][139] Bahrain's banking and financial services sector, particularly Islamic banking, have benefited from the regional boom driven by demand for oil.[139] Petroleum production and processing account is Bahrain's most exported product, accounting for 60% of export receipts, 70% of government revenues, and 11% of GDP.[141] Aluminium production is the second most exported product, followed by finance and construction materials.[141]

Economic conditions have fluctuated with the changing price of oil since 1985, for example during and following the Persian Gulf crisis of 1990–91. With its highly developed communication and transport facilities, Bahrain is home to a number of multinational firms and construction proceeds on several major industrial projects. A large share of exports consist of petroleum products made from imported crude oil. In 2004, Bahrain signed the US-Bahrain Free Trade Agreement, which will reduce certain trade barriers between the two nations.[142] Due to the combination of the global financial crisis and the recent unrest, the growth rate decreased to 2.2% which is the lowest growth rate since 1994.[143]

Unemployment, especially among the young, and the depletion of both oil and underground water resources are major long-term economic problems. In 2008, the jobless figure was at 4%,[144] with women over represented at 85% of the total.[145] In 2007 Bahrain became the first Arab country to institute unemployment benefits as part of a series of labour reforms instigated under Minister of Labour, Dr. Majeed Al Alawi.[146]

Tourism

As a tourist destination, Bahrain receives over eight million visitors in 2008 though the exact number varies yearly.[147] Most of these are from the surrounding Arab states although an increasing number hail from outside the region due to growing awareness of the kingdom's heritage and its higher profile as a result of the Bahrain International F1 Circuit. The Lonely Planet Guide describes Bahrain as "an excellent introduction to the Persian Gulf",[148] because of its authentic Arab heritage and reputation as a liberal and modern country.

The kingdom combines modern Arab culture and the archaeological legacy of five thousand years of civilisation. The island is home to forts including Qalat Al Bahrain which has been listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site. The Bahrain National Museum has artefacts from the country's history dating back to the island's first human inhabitants some 9000 years ago and the Beit Al Quran (Arabic: بيت القرآن, meaning: the House of Qur'an) is a museum that holds Islamic artefacts of the Qur'an. Some of the popular historical tourist attractions in the kingdom are the Al Khamis Mosque, which is the one of the oldest mosques in the region, the Arad fort in Muharraq, Barbar temple, which is an ancient temple from the Dilmunite period of Bahrain, as well as the A'ali Burial Mounds and the Saar temple. The Tree of Life, a 400 year-old tree that grows in the Sakhir desert with no nearby water, is also a popular tourist attraction.[149]

Bird watching (primarily in the Hawar Islands), scuba diving and horse riding are popular tourist activities in Bahrain. Many tourists from nearby Saudi Arabia and across the region visit Manama primarily for the shopping malls in the capital Manama, such as the Bahrain City Centre and Seef Mall in the Seef district of Manama. The Manama Souq and Gold Souq in the old district of Manama are also popular with tourists.[150]

Since 2005, Bahrain annually hosts a festival in March, titled Spring of Culture, which features internationally renowned musicians and artists performing in concerts.[151] Manama was named the Arab Capital of Culture for 2012 and Capital of Arab Tourism for 2013 by the Arab League. The 2012 festival featured concerts starring Andrea Bocelli, Julio Iglesias and other musicians.[152]

Infrastructure

Bahrain has one main international airport, the Bahrain International Airport (BIA) which is located on the island of Muharraq, in the north-east. The airport handled more than 100,000 flights and more than 8 million passengers in 2010. Bahrain's national carrier, Gulf Air operates and bases itself in the BIA. Bahrain Air, a privately owned Bahraini airline, also operates from the same airport.

Bahrain has a well-developed road network, particularly in Manama. The discovery of oil in the early 1930s accelerated the creation of multiple roads and highways in Bahrain, connecting several isolated villages, such as Budaiya, to Manama. [153]

To the east, a bridge connected Manama to Muharraq since 1929, a new causeway was built in 1941 which replaced the old wooden bridge.[153] Transits between the two islands peaked after the construction of the Bahrain International Airport in 1932.[153] Ring roads and highways were later built to connect Manama to the villages of the Northern Governorate and towards towns in central and southern Bahrain.

The four main islands and all the towns and villages are linked by well-constructed roads. There were 3,164 km (1,966 mi) of roadways in 2002, of which 2,433 km (1,512 mi) were paved. A causeway stretching over 2.8 km (2 mi), connect Manama with Muharraq Island, and another bridge joins Sitra to the main island. The King Fahd Causeway, measuring 24 km (15 mi), links Bahrain with the Saudi Arabian mainland via the island of Umm an-Nasan. It was completed in December, 1986, and financed by Saudi Arabia. In 2008, there were 17,743,495 passengers transiting through the causeway. [154]

Bahrain's port of Mina Salman can accommodate 16 oceangoing vessels drawing up to 11 m (36 ft). In 2001, Bahrain had a merchant fleet of eight ships of 1,000 GRT or over, totaling 270,784 GRT. Private vehicles and taxis are the primary means of transportation in the city.

Telecommunications

The telecommunications sector in Bahrain officially started in 1981 with the establishment of Bahrain's first telecommunications company, Batelco and until 2004, it monopolised the sector. In 1981, there were more than 45,000 telephones in use in the country. By 1999, Batelco had more than 100,000 mobile contracts[155] In 2002, under pressure from international bodies, Bahrain implemented its telecommunications law which included the establishment of an independent Telecommunications Regulatory Authority (TRA).[155]. In 2004, Zain (a rebranded version of MTC Vodafone) started operations in Bahrain.

Bahrain has been connected to the internet since 1995 with the country's domain suffix is '.bh'. The country's connectivity score (a statistic which measures both Internet access and fixed and mobile telephone lines) is 210.4 percent per person, while the regional average in the Gulf States is 135.37 percent.[156] The number of Bahraini internet users has risen from 40,000 in 2000[157] to 250,000 in 2008,[158] or from 5.95 to 33 percent of the population. As of January 2012, the TRA has licensed 34 Internet Service Providers, the largest of which is Batelco.[159]

Geography

Bahrain is a generally flat and arid archipelago in the Persian Gulf, east of Saudi Arabia. It consists of a low desert plain rising gently to a low central escarpment with the highest point the 134 m (440 ft) Mountain of Smoke (Jabal ad Dukhan).[160] [161] Bahrain had a total area of 665 km2 (257 sq mi) but due to land reclamation, the area increased to 767 km2 (296 sq mi), which is slightly larger than the Isle of Man.[161]

As an archipelago of thirty-three islands, Bahrain does not share a land boundary with another country but does have a 161 km (100 mi) coastline. The country also claims a further 22 km (12 nmi) of territorial sea and a 44 km (24 nmi) contiguous zone. Bahrain's largest islands are Bahrain Island, Muharraq Island, Umm an Nasan, and Sitrah. Bahrain has mild winters and very hot, humid summers. The country's natural resources include large quantities of oil and natural gas as well as fish in the offshore waters. Arable land constitutes only 2.82%[141] of the total area.

92% of Bahrain is desert with periodic droughts and dust storms the main natural hazards for Bahrainis. Environmental issues facing Bahrain include desertification resulting from the degradation of limited arable land, coastal degradation (damage to coastlines, coral reefs, and sea vegetation) resulting from oil spills and other discharges from large tankers, oil refineries, distribution stations, and illegal land reclamation at places such as Tubli Bay. The agricultural and domestic sectors' over-utilization of the Dammam Aquifer, the principal aquifer in Bahrain, has led to its salinisation by adjacent brackish and saline water bodies. Over-abstraction of the Dammam aquifer, the principal aquifer in Bahrain, by the agricultural and domestic sectors, has led to its salinization by adjacent brackish and saline water bodies. A hydrochemical study identified the locations of the sources of aquifer salinization and delineated their areas of influence. The investigation indicates that the aquifer water quality is significantly modified as groundwater flows from the northwestern parts of Bahrain, where the aquifer receives its water by lateral underflow from eastern Saudi Arabia, to the southern and southeastern parts. Four types of salinization of the aquifer are identified: brackish-water up-flow from the underlying brackish-water zones in north-central, western, and eastern regions; seawater intrusion in the eastern region; intrusion of sabkha water in the southwestern region; and irrigation return flow in a local area in the western region. Four alternatives for the management of groundwater quality that are available to the water authorities in Bahrain are discussed and their priority areas are proposed, based on the type and extent of each salinization source, in addition to groundwater use in that area.[162]

Climate

The Zagros Mountains across the Persian Gulf in Iraq cause low level winds to be directed toward Bahrain. Dust storms from Iraq and Saudi Arabia transported by northwesterly winds cause reduced visibility in the months of June and July.

Due to the Persian Gulf area's low moisture, summers are very hot and dry. The seas around Bahrain are very shallow, heating up quickly in the summer to produce high humidity, especially at night. Summer temperatures may reach more than 40 °C (104 °F) under the right conditions. Rainfall in Bahrain is minimal and irregular. Rainfalls mostly occur in winter, with a recorded maximum of 71.8 mm (2.83 in).[163]

| Climate data for Manama | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 20.0 (68.0) |

21.2 (70.2) |

24.7 (76.5) |

29.2 (84.6) |

34.1 (93.4) |

36.4 (97.5) |

37.9 (100.2) |

38.0 (100.4) |

36.5 (97.7) |

33.1 (91.6) |

27.8 (82.0) |

22.3 (72.1) |

30.1 (86.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 14.1 (57.4) |

14.9 (58.8) |

17.8 (64.0) |

21.5 (70.7) |

26.0 (78.8) |

28.8 (83.8) |

30.4 (86.7) |

30.5 (86.9) |

28.6 (83.5) |

25.5 (77.9) |

21.2 (70.2) |

16.2 (61.2) |

23.0 (73.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 14.6 (0.57) |

16.0 (0.63) |

13.9 (0.55) |

10.0 (0.39) |

1.1 (0.04) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.5 (0.02) |

3.8 (0.15) |

10.9 (0.43) |

70.8 (2.79) |

| Average precipitation days | 2.0 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.4 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 1.7 | 9.9 |

| Source: World Meteorological Organisation (UN) [164] | |||||||||||||

Biodiversity

More than 330 species of birds were recorded in the Bahrain archipelago, 26 species of which breed in the country. Millions of migratory birds pass through the Gulf region in the winter and autumn months.[165] One globally endangered species, Chlamydotis undulata, is a regular migrant in the autumn.[165] The many islands and shallow seas of Bahrain are globally important for the breeding of the Phalacrocorax nigrogularis specie of bird, up to 100,000 pairs of these birds were recorded over the Hawar islands.[165] Only 18 species of mammals are found in Bahrain, animals such as Gazelles, desert rabbits and hedgehogs are common in the wild but the Arabian Oryx was hunted to extinction on the island.[165] 25 species of amphibians and reptiles were recorded as well as 21 species of butterflies and 307 species of flora.[165] The marine biotopes are diverse and include extensive sea grass beds and mudflats, patchy coral reefs as well as offshore islands. Sea grass beds are important foraging grounds for some threatened species such as dugongs and the green turtle.[166] In 2003, Bahrain banned the capture of sea cows, marine turtles and dolphins within its territorial waters.[165]

The Hawar Islands Protected Area provides valuable feeding and breeding grounds for a variety of migratory seabirds, it is an internationally recognised site for bird migration. The breeding colony of Socotra Cormorant on Hawar Islands is the largest in the world, and the dugongs foraging around the archipelago form the second largest dugong aggregation after Australia.[166]

Bahrain has five designated protected areas, four of which are marine environments.[165] They are:

- Hawar Islands

- Mashtan Island, off the coast of Bahrain.

- Arad bay, in Muharraq.

- Tubli Bay

- Al Areen Wildlife Park, which is a zoo and a breeding centre for endangered animals, is the only protected area on land and also the only protected area which is managed on a day-to-day basis.[165]

Demographics

In 2010, Bahrain's population grew to 1.2 million, of which 568,399 were Bahraini and 666,172 were non-nationals.[1] It had risen from 1.05 million (517,368 non-nationals) in 2007, the year when Bahrain's population crossed the one million mark.[167] Though a majority of the population is ethnically Arab, a sizeable number of people from South Asia live in the country. In 2008, approximately 290,000 Indian nationals lived in Bahrain, making them the single largest expatriate community in the country.[168][169]

Bahrain is the fourth most densely populated sovereign state in the world with a population density of 1,646 people per km2 in 2010.[170] The only sovereign states with larger population densities are city states. Much of this population is concentrated in the north of the country with the Southern Governorate being the least densely populated part.[1] The north of the country is so urbanised that it is considered by some to be one large metropolitan area.[171]

The official religion of Bahrain is Islam and 99.8% of Bahraini citizens are Muslim. There are no official figures for the proportion of Shia and Sunni among the Muslims of Bahrain, but approximately 66-70% percent of Bahraini Muslims are Shias.[172][173][174][175] Due to an influx of immigrants and guest workers from non-Muslim countries, such as India, Philippines and Sri Lanka, the overall percentage of Muslims in the country has declined in recent years.[176] According to the 2001 census, 81.2% of Bahrain's population was Muslim, 9% were Christian, and 9.8% practised Hinduism or other religions.[141] The 2010 census records that the Muslim proportion had fallen to 70.2% (the 2010 census did not differentiate between the non-Muslim religions).[177]

Languages

Arabic is the official language of Bahrain, though English is widely used.[178] Bahrani Arabic is the most widely spoken dialect of the Arabic language, though this differs slightly from standard Arabic. Arabic plays an important role in political life, as, according to article 57 (c) of Bahrain's constitution, an MP must be fluent in Arabic to stand for parliament. Among the non-Bahraini population, many people speak Farsi, the official language of Iran, or Urdu, the official language of Pakistan.[178] Malayalam and Hindi is also widely spoken in the Indian community.[178]{ Many commercial institutions and road signs are bilingual, displaying both English and Arabic.[179]

Education

Education is compulsory for children between the ages of 6 and 14.[180] Education is free for Bahraini citizens in public schools, with the Bahraini Ministry of Education providing free textbooks. Coeducation is not used in public schools, with boys and girls segregated into separate schools.[181]

At the beginning of the 20th century, Qur'anic schools (Kuttab) were the only form of education in Bahrain. [182]They were traditional schools aimed at teaching children and youth the reading of the Qur'an. After World War I, Bahrain became open to western influences, and a demand for modern educational institutions appeared. 1919 marked the beginning of modern public school system in Bahrain when the Al-Hidaya Al-Khalifia School for boys opened in Muharraq.[182] In 1926, the Education Committee opened the second public school for boys in Manama, and in 1928 the first public school for girls was opened in Muharraq.[182] As of 2011, there are a total of 126,981 students studying in public schools.[183]

In 2004, King Hamad ibn Isa Al Khalifa introduced the "King Hamad Schools of Future" project that uses Information Communication Technology to support K–12 education in Bahrain.[184] The project's objective is to connect all schools within the kingdom with the Internet.[185] In addition to British intermediate schools, the island is served by the Bahrain School (BS). The BS is a United States Department of Defense school that provides a K-12 curriculum including International Baccalaureate offerings. There are also private schools that offer either the IB Diploma Programme or United Kingdom's A-Levels.

Bahrain also encourages institutions of higher learning, drawing on expatriate talent and the increasing pool of Bahrain nationals returning from abroad with advanced degrees. The University of Bahrain was established for standard undergraduate and graduate study, and the King Abdulaziz University College of Health Sciences, operating under the direction of the Ministry of Health, trains physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and paramedics. The 2001 National Action Charter paved the way for the formation of private universities such as the Ahlia University in Manama and University College of Bahrain in Saar. The Royal University for Women (RUW), established in 2005, was the first private, purpose-built, international University in Bahrain dedicated solely to educating women. The University of London External has appointed MCG (Management Consultancy Group) as the regional representative office in Bahrain for distance learning programs.[186] MCG is one of the oldest private institutes in the country. Institutes have also opened which educate Asian students, such as the Pakistan Urdu School, Bahrain and the Indian School, Bahrain. A few prominent institutions are DePaul University, Bentley University, the Ernst & Young Training Institute, NYIT and the Birla Institute of Technology International Centre In 2004, the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland (RCSI) setup a constituent medical university in the country. In addition to the Arabian Gulf University, AMA International University and the College of Health Sciences, these are the only medical schools in Bahrain.

Health

Bahrain has a universal health care system, dating back to 1960.[187] Government-provided health care is free to Bahraini citizens and heavily subsidised for non-Bahrainis. Healthcare expenditure accounted for 4.5% of Bahrain's GDP, according to the World Health Organisation. Bahraini physicians and nurses form a majority of the country's workforce in the health sector, unlike neighbouring Gulf states.[188] The first hospital to open in Bahrain is the American Missionary Hospital, which first opened in 1893 as a dispensary.[189] The first public hospital, and also tertiary hospital, to open in Bahrain is the Salmaniya Medical Complex, in the Salmaniya district of Manama, in 1957.[190] Private hospitals are also present throughout the country, such as the International Hospital of Bahrain.

The life expectancy in Bahrain is 73 for males and 76 for females. Compared to many countries in the region, the prevalence of AIDS and HIV is relatively low.[191] Malaria and tuberculosis (TB) do not constitute major problems in Bahrain as neither disease is indigenous to the country. As a result, cases of malaria and TB have declined in recent decades with cases of contractions amongst Bahraini nationals becoming rare.[191] The Ministry of Health sponsors regular vaccination campaigns against TB and other diseases such as hepatitis B. [191] [192]

Bahrain is currently suffering from an obesity epidemic as 28.9% of all males and 38.2% of all females are classified as obese.[193] Bahrain also has one of the highest prevalence of diabetes in the world (5th place), with more than 15% of the Bahraini population suffering from the disease, and accounting for 5% of deaths in the country.[194] Cardiovascular diseases account for 32% of all deaths in Bahrain, being the number one cause of death in the country (the second being cancer).[195] Sickle cell anaemia and thalassaemia are prevalent in the country, with a study concluding that 18% of Bahrainis are carriers of sickle cell anaemia while 24% are carriers of thalassaemia.[196]

Culture

Bahrain is sometimes described as "Middle East lite"[197] due to its combination of modern infrastructure with a Persian Gulf identity. While Islam is the main religion, Bahrainis are known for their tolerance towards the practice of other faiths.[198]

In common with the rest of the Muslim world, though Bahrain has take strong strides for women's rights, it does not recognise lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender rights.[199]

Another facet of the new openness is Bahrain's status as the most prolific book publisher in the Arab world, with 132 books published in 2005 for a population of 700,000. In comparison, the 2005 average for the entire Arab world was seven books published per one million people, according to the United Nations Development Programme.[200]

Music

The music style in Bahrain is similar to that of its neighbours. The Khaliji style of music, which is folk music, is popular in the country. The sawt style of music, which involves a complex form of urban music, performed by an Oud (plucked lute), a violin and mirwas (a drum), is also popular in Bahrain.[201] Ali Bahar was one of the most famous singer in Bahrain. He performed his music with his Band Al-Ekhwa (The Brothers). Bahrain was also the site of the first recording studio amongst the Gulf states.[201]

Sports

Association football is the most popular sport in Bahrain.[202] Bahrain's national football team has competed multiple times at the Asian Cup, Arab Nations Cup and played in the FIFA World Cup qualifiers, though it has never qualified for the World Cup.[203] Bahrain has its own top-tier domestic professional football league, the Bahraini Premier League. Basketball, Rugby and horse riding are also widely popular in the country.

Bahrain has competed in six Summer Olympics, debuting in the 1984 Los Angelas Summer Olympics.[204] Bahrain has never won an Olympic medal in its history, the closest being via Rashid Ramzi winning the men's 1,500 meters race at the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics but having his medal stripped after failing a doping test.[205] It has competed in every Summer Olympic since then and is scheduled to compete in the upcoming 2012 London Summer Olympics. Bahrain has never competed in the Winter Olympics.

Bahrain has a Formula One race-track, which hosted the inaugural Gulf Air Grand Prix on 4 April 2004, the first in an Arab country. This was followed by the Bahrain Grand Prix in 2005. Bahrain hosted the opening Grand Prix of the 2006 season on 12 March of that year. Both the above races were won by Fernando Alonso of Renault. The race has since been hosted annually, with the latest edition of the Bahrain Grand Prix was the 2012 Bahrain Grand Prix, that occurred despite concerns of the safety of the teams and the ongoing protests in the country.[206] The race's opponents described the decision to hold the race despite ongoing protests and violence[207] as "one of the most controversial Grands Prix in the sport's sixty-year history".[208][209][210]

In 2006, Bahrain also hosted its inaugural Australian V8 Supercar event dubbed the "Desert 400". The V8s will return every November to the Sakhir circuit. The Bahrain International Circuit also features a full length drag strip where the Bahrain Drag Racing Club has organised invitational events featuring some of Europe's top drag racing teams to try to raise the profile of the sport in the Middle East.[211]

Holidays

On 1 September 2006, Bahrain changed its weekend from being Thursdays and Fridays to Fridays and Saturdays, in order to have a day of the weekend shared with the rest of the world. Other non-regular holidays are listed below:

| Date | English name | Local (Arabic) name | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 January | New Year's Day | رأس السنة الميلادية | The Gregorian New Year's Day, celebrated by most parts of the world. |

| 1 May | Labour Day | يوم العمال | |

| 16 December | National Day | اليوم الوطني | National Day, Accession Day for the late Amir Sh. Isa Bin Salman Al Khalifa |

| 17 December | Accession Day | يوم الجلوس | |

| 1st Muharram | Islamic New Year | رأس السنة الهجرية | Islamic New Year (also known as: Hijri New Year). |

| 9th, 10th Muharram | Day of Ashura | عاشوراء | Commemorates the martyrdom of Imam Hussein. |

| 12th Rabiul Awwal | Prophet Muhammad's birthday | المولد النبوي | Commemorates Prophet Muhammad's birthday, celebrated in most parts of the Muslim world. |

| 1st, 2nd, 3rd Shawwal | Little Feast | عيد الفطر | Commemorates end of Ramadan. |

| 9th Zulhijjah | Arafat Day | يوم عرفة | |

| 10th, 11th, 12th Zulhijjah | Feast of the Sacrifice | عيد الأضحى | Commemorates Ibrahim's willingness to sacrifice his son. Also known as the Big Feast (celebrated from the 10th to 13th). |

See also

- Bahrain World Trade Center

- Manama

- Utub

- List of towns and villages of Bahrain

- List of tallest buildings and structures in Bahrain

References

- ^ a b c d e f "General Tables". Bahraini Census 2010. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Bahrain". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2011" (PDF). United Nations. 2011. Retrieved 19 January 2012.

- ^ "Project overview: Qatar-Bahrain Causeway". 13 June 2009. Retrieved 21 March 2010.

- ^ "Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Bahrain - International Organisations". Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Bahrain. Retrieved 24 June 2012.

- ^ "Bahrain Becomes a 'Major Non-NATO Ally'". Voice of America. 2001-10-26. Retrieved 24 June 2012.

- ^ "Bahrain's economy praised for diversity and sustainability". Bahrain Economic Development Board. Retrieved 24 June 2012.

- ^ "Qal'at al-Bahrain – Ancient Harbour and Capital of Dilmun – UNESCO World Heritage Centre". Whc.unesco.org. 15 July 2005. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- ^ "Bahrain – Home of Motorsport in the Middle East". Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- ^ a b Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. I. "Bahrayn", p. 941. E.J. Brill (Leiden), 1960.

- ^ Room, Adrian. Origins and Meanings of the Names for 6,600 Countries, Cities, Territories, Natural Features and Historic Sites. 2006. ISBN 978-0-7864-2248-7.

- ^ Brill, E.J. First encyclopaedia of Islam 1913-1936. p. 584. ISBN 978-9004097964.

- ^ a b Faroughy, Abbas. The Bahrein Islands (750–1951): A Contribution to the Study of Power Politics in the Persian Gulf. Verry, Fisher & Co. (New York), 1951.

- ^ Rice, Michael. The Archaeology of the Arabian Gulf, c. 5000-323 BC. Routledge, 1994. ISBN 0-415-03268-7.

- ^ History of Bahrain History of Nations website

- ^ Bahrain History - Pre-Islam

- ^ Brief History of Bahrain - Travel Guide

- ^ Security and Territoriality in the Persian Gulf: A Maritime Political Geography by Pirouz Mojtahed-Zadeh, page 119

- ^ Bahrain By Federal Research Division, page 7

- ^ a b c d Robert G. Hoyland, Arabia and the Arabs: From the Bronze Age to the Coming of Islam, Routledge 2001, p. 28 Cite error: The named reference "Ref_" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Conflict and Cooperation: Zoroastrian Subalterns and Muslim Elites in ... by Jamsheed K. Choksy, 1997, page 75

- ^ http://www.rasoulallah.net/v2/document.aspx?lang=en&doc=2589

- ^ A letter purported to be from Muhammad to al-Tamimi is preserved at the Beit al-Qur'an Museum in Hoora, Bahrain.

- ^ "The letters of the Prophet Muhammed beyond Arabia" (PDF). Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ Cyril Glasse, New Encyclopedia of Islam, p. 245. Rowman Altamira, 2001. ISBN 0-7591-0190-6

- ^ "Black Stone of Mecca". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 25 June 2007 <http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9015514>.

- ^ Juan Cole, Sacred Space and Holy War, IB Tauris, 2007

- ^ Smith, G.R. "Uyūnids". Encyclopaedia of Islam. Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs. Brill, 2008. Brill Online. 16 March 2008 [1]

- ^ Rentz, G. "al- Baḥrayn". Encyclopaedia of Islam. Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs. Brill, 2008. Brill Online. 15 March 2008 [2]

- ^ Juan R. I. Cole, "Rival Empires of Trade and Imami Shiism in Eastern Arabia, 1300–1800", International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 19, No. 2. (May 1987), pp. 177–203, at p. 179, through JSTOR. [3]

- ^ Rentz, G. "al- Baḥrayn".

- ^ a b Rentz, "al- Baḥrayn".

- ^ Juan R. I. Cole, "Rival Empires of Trade and Imami Shiism in Eastern Arabia, 1300–1800", p. 186, through JSTOR. [4]

- ^ X. De Planhol

- ^ Juan R. I. Cole, Rival Empires of Trade and Imami Shiism in Eastern Arabia, 1300–1800, p. 194

- ^ Juan R. I. Cole, "Rival Empires of Trade and Imami Shiism in Eastern Arabia, 1300–1800", p. 187

- ^ a b McCoy, Eric (2008). Iranians in Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates: Migration, Minorities, and Identities in the Persian Gulf Arab States. ProQuest. p. 73.

- ^ The Origins of Kuwait, B.J. Slot, p110

- ^ Ownership deeds to a palm garden on the island of Sitra, Bahrain, belonging to Shaikh Salama Bin Saif Al Utbi, dated 1699–1111 Hijri,

- ^ Arabia's Frontiers: The Story of Britain's Boundary Drawing in the Desert, John C. Wilkinson, p44

- ^ Around the Coast, Amin Reehani, p297

- ^ Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf, Oman, and Central Arabia, Geographical, Volume 1, 1905

- ^ Picture of the Al Sulami Flag in the "Ardha of War" which was celebrated in Eid Al Fitr in Muharraq 1956 which was attended by Shaikh Salman Bin Hamad Al Khalifa, ex Ruler of Bahrain, http://www.albdoo.info/imgcache2008/4ab9efef269d2d54873df27f7495a456.jpg

- ^ Arabian Studies by R.B. Serjeant, R.L. Bidwell, p67

- ^ Background Notes: Mideast, March, 2011. US State Department. 2011. ISBN 1592431267.

- ^ Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf, Oman, and Central Arabia, John Gordon Lorimer, Volume 1 Historical, Part 1, p1000, 1905

- ^ James Onley, The Politics of Protection in the Persian Gulf: The Arab Rulers and the British Resident in the Nineteenth Century, Exeter University, 2004 p44

- ^ Al-Baharna, Husain (1968). Legal Status of the Arabian Gulf States: A Study of Their Treaty Relations and Their International Problems. Manchester University Press. p. 31. ISBN 0719003326.

- ^ a b c d e f g Pridham, B.R. (2004). New Arabian Studies, Volume 6. University of Exeter Press. pp. 51, 52, 53, 67, 68. ISBN 0859897060.

- ^ Pridham, B. R. (1985). The Arab Gulf and the West. Croom Helm. pp. `7. ISBN 0709940114.

- ^ a b c Wilson, Arnold T. The Persian Gulf. Routledge. ISBN 1136841059.

- ^ a b c Mojtahed-Zadeh, Pirouz (1999). Security and Territoriality in the Persian Gulf: A Maritime Political Geography. Routledge. p. 130. ISBN 0700710981.

- ^ "All at sea over 'the Gulf'". Asia Times. Dec 9, 2004. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ^ "Bahrain:"How was separated from Iran" ?". Iran Chamber Society. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- ^ "Bahrain Education". Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- ^ "Bahrain's Re-Reform Movement". Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- ^ "Bahrain: Discovery of Oil". January 1993. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ "Bahrain". Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ a b [5], Cambridge Archive Editions: Bahrain

- ^ Italian Air Raid!

- ^ Italian Raid on Manama 1940

- ^ a b The King of Bahrain Wants the Jews Back, Israel National News, 14 August 2008

- ^ "Bahrain's journey from kingdom to province". MEED. 17 March 2011. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ Iran Chamber: Bahrain

- ^ a b Mojtahedzadeh, Piruz (1995). "Bahrain: the land of political movements". Rahavard, a Persian Journal of Iranian Studies. XI (39).

- ^ Al-Saud, Faisal (2004). Iran, Saudi Arabia and the Gulf: Power Politics in Transition 1968-1971. pp. 40, 41, 42. ISBN 1860648819.

- ^ Breffni O'Rourke (November 15, 2007). "Iran: Ahmadinejad's Bahrain Visit New Piece In Complex Pattern". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Archived from the original on 2010-06-17. Retrieved 2012-06-17.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "" Independence or Iran?" UN asks Bahrainis". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- ^ "Cascon Case BAH: Bahrain 1970". Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ "UN Report no. 9772" (PDF). UN. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- ^ The Middle East and North Africa 2004. Routledge. 2003. p. 225. ISBN 1857431847.

- ^ Bahrain Profile National Post 7 April 2007

- ^ "Stay just over the horizon this time", Time magazine, 25 October 1982

- ^ "Bahrain: 1994-1999 Uprising". Scribd.

- ^ Rebellion in Bahrain, Middle East Review of International Affairs, March 1999

- ^ "Country Profiles Bahrain" The Arab Center for the Development of the Rule of Law and Integrity Retrieved 1 December 2010

- ^ "Country Theme: Elections: Bahrain". UNDP-Programme on Governance in the Arab Region. 2011. Archived from the original on 9 February 2011. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Bahrain: Promising human rights reform must continue" (Document). Amnesty International. 13 March 2001.

{{cite document}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|coauthors=and|work=(help); Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|archivedate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|archiveurl=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|format=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ "The Kingdom of Bahrain: The Constitutional Changes". The Estimate: Political and Security Analysis of the Islamic World and its Neighbors. 22 February 2002. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

- ^ a b c The Middle East and North Africa 2004. Europa Publications. 2003. p. 232. ISBN 1857431847.

- ^ "To Implement the United States-Bahrain Free Trade Agreement, and for Other Purposes". White House Archives. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- ^ a b c "Bahrain declares state of emergency after unrest". Reuters. 15 March 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Report of the Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry". BICI.

- ^ "Bahrain mourners call for end to monarchy". The Guardian. 18 February 2011.

- ^ "Day of transformation in Bahrain's 'sacred square'". BBC News. 19 February 2011.

- ^ "Bangladeshis complain of Bahrain rally 'coercion'". BBC News. 17 March 2011.

- ^ "Gulf States Send Force to Bahrain Following Protests". BBC News. 14 March 2011. Archived from the original on 20 April 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Curfew Follows Deadly Bahrain Crackdown – Curfew Enforced, Several Dead and Hundreds Injured as Security Forces Use Tanks and Helicopters To Quash Protest". Al Jazeera English. 16 March 2011. Archived from the original on 14 April 2011. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Bahrain authorities destroy Pearl Roundabout". The Daily Telegraph. 18 March 2011.

- ^ "Bahrain sees new clashes as martial law lifted". The Guardian. 1 June 2011.

- ^ "Thousands rally for reform in Bahrain". Reuters. 11 June 2011.

- ^ "Bahrain live blog 25 Jan 2012". Al Jazeera. 25 January 2012. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- ^ "Heavy police presence blocks Bahrain protests". Al Jazeera. 15 February 2012. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- ^ "Bahrain protesters join anti-government march in Manama". BBC. 9 March 2012.

- ^ "Mass pro-democracy protest rocks Bahrain". Reuters. 9 March 2012.

- ^ Law, Bill (6 April 2011). "Police Brutality Turns Bahrain Into 'Island of Fear'. Crossing Continents (via BBC News). Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ^ Press release (30 March 2011). "USA Emphatic Support to Saudi Arabia". Zayd Alisa (via Scoop). Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ^ Cockburn, Patrick (18 March 2011). "The Footage That Reveals the Brutal Truth About Bahrain's Crackdown – Seven Protest Leaders Arrested as Video Clip Highlights Regime's Ruthless Grip on Power". The Independent. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ^ Wahab, Siraj (18 March 2011).

- ^ Law, Bill (22 March 2011). "Bahrain Rulers Unleash 'Campaign of Intimidation'". Crossing Continents (via BBC News). Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ^ (registration required) "UK – Bahrain Union Suspends General Strike". Financial Times. 22 March 2011. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- ^ Chick, Kristen (1 April 2011). "Bahrain's Calculated Campaign of Intimidation – Bahraini Activists and Locals Describe Midnight Arrests, Disappearances, Beatings at Checkpoints, and Denial of Medical Care – All Aimed at Deflating the Country's Pro-Democracy Protest Movement". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ^ "Bahrain inquiry confirms rights abuses - Middle East". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 2012-06-19.

- ^ Applying pressure on Bahrain, 9 May 2011, Retrieved 9 May 2011

- ^ "Bahrain protesters join anti-government march in Manama". BBC. 9 March 2012. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ^ "Report: Doctors targeted in Bahrain". Al Jazeera. 18 July 2011. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Bahrain delays U.N. investigator, limits rights group visits". Reuters. 1 March 2012.

- ^ "Bahrain". International Foundation for Electoral Systems. 26 July 2010. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ Gulf News, 27 November 2006

- ^ "Islamists Dominate Bahrain Elections". Washington Post. November 26, 2006. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- ^ Mannequins ban councillor up in arms Gulf Daily News, 11 April 2005

- ^ Drying underwear in public 'offensive', Gulf Daily News, 11 March 2005

- ^ "Islamist Terrorism and Democracy in the Middle East". The New Republic. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- ^ The International Convention on Civil and Political Rights Human Rights Web

- ^ Rights push by Bahrain, Gulf Daily News, 14 June 2006

- ^ Councillors 'missing' in Bangkok, Gulf Daily News, 15 March 2006

- ^ Councillors face the music after Bangkok jaunt, Gulf Daily News 16 March 2006

- ^ "Liberals celebrate first anniversary of 'union'". Gulf News. August 1, 2006. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- ^ MacFARQUHAR, NEIL (22 May 2002). "In Bahrain, Women Run, Women Vote, Women Lose". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- ^ Islamists gain majority in Bahrain The Telegraph

- ^ Jew and Christian amongst 10 women in Shura council Middle East Online

- ^ 'UN General Assembly to be headed by its third-ever woman president', United Nations, 8 June 2006

- ^ Bahrain International Commission Jurists

- ^ Bahrain Law on Judicial Authority Published on WikiSource from the Arab Judicial Forum 15–17 September 2003

- ^ Bahrain sets up institute to train judges and prosecutors Gulf News, 15 November 2005

- ^ Forum for the Future Factsheet US State Department, 2005