NATO

50°52′34″N 4°25′19″E / 50.87611°N 4.42194°E

| Organisation du Traité de l'Atlantique Nord | |

Logo | |

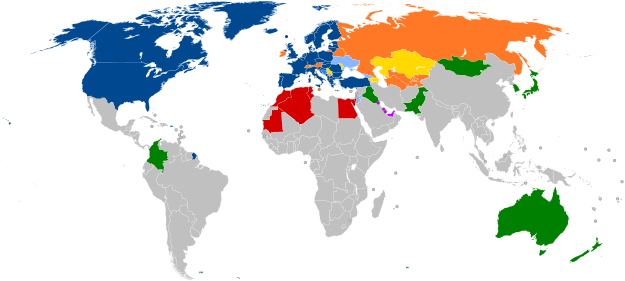

Member states of NATO | |

| Abbreviation | NATO, OTAN |

|---|---|

| Formation | 4 April 1949 |

| Type | Military alliance |

| Headquarters | Brussels, Belgium |

Membership | |

Official language | English French[1] |

| Jens Stoltenberg | |

| Petr Pavel | |

| Curtis Scaparrotti | |

| Denis Mercier | |

| Website | nato |

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO /ˈneɪtoʊ/; Template:Lang-fr; OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance based on the North Atlantic Treaty which was signed on 4 April 1949. The organization constitutes a system of collective defence whereby its member states agree to mutual defence in response to an attack by any external party. NATO's headquarters are located in Haren, Brussels, Belgium, where the Supreme Allied Commander also resides. Belgium is one of the 28 member states across North America and Europe, the newest of which, Albania and Croatia, joined in April 2009. An additional 22 countries participate in NATO's Partnership for Peace program, with 15 other countries involved in institutionalized dialogue programmes. The combined military spending of all NATO members constitutes over 70% of the global total.[3] Members' defence spending is supposed to amount to 2% of GDP.[4]

NATO was little more than a political association until the Korean War galvanized the organization's member states, and an integrated military structure was built up under the direction of two US supreme commanders. The course of the Cold War led to a rivalry with nations of the Warsaw Pact, which formed in 1955. Doubts over the strength of the relationship between the European states and the United States ebbed and flowed, along with doubts over the credibility of the NATO defence against a prospective Soviet invasion—doubts that led to the development of the independent French nuclear deterrent and the withdrawal of France from NATO's military structure in 1966 for 30 years. After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the organization was drawn into the breakup of Yugoslavia, and conducted its first military interventions in Bosnia from 1992 to 1995 and later Yugoslavia in 1999. Politically, the organization sought better relations with former Warsaw Pact countries, several of which joined the alliance in 1999 and 2004.

Article 5 of the North Atlantic treaty, requiring member states to come to the aid of any member state subject to an armed attack, was invoked for the first and only time after the September 11 attacks,[5] after which troops were deployed to Afghanistan under the NATO-led ISAF. The organization has operated a range of additional roles since then, including sending trainers to Iraq, assisting in counter-piracy operations[6] and in 2011 enforcing a no-fly zone over Libya in accordance with U.N. Security Council Resolution 1973. The less potent Article 4, which merely invokes consultation among NATO members, has been invoked five times: by Turkey in 2003 over the Iraq War; twice in 2012 by Turkey over the Syrian Civil War, after the downing of an unarmed Turkish F-4 reconnaissance jet, and after a mortar was fired at Turkey from Syria;[7] in 2014 by Poland, following the Russian intervention in Crimea;[8] and again by Turkey in 2015 after threats by the Islamic State to its territorial integrity.[9]

History

Beginnings

The Treaty of Brussels, signed on 17 March 1948 by Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, France, and the United Kingdom, is considered the precursor to the NATO agreement. The treaty and the Soviet Berlin Blockade led to the creation of the Western European Union's Defence Organization in September 1948.[10] However, participation of the United States was thought necessary both to counter the military power of the USSR and to prevent the revival of nationalist militarism, so talks for a new military alliance began almost immediately resulting in the North Atlantic Treaty, which was signed in Washington, D.C. on 4 April 1949. It included the five Treaty of Brussels states plus the United States, Canada, Portugal, Italy, Norway, Denmark and Iceland.[11] The first NATO Secretary General, Lord Ismay, stated in 1949 that the organization's goal was "to keep the Russians out, the Americans in, and the Germans down."[12] Popular support for the Treaty was not unanimous, and some Icelanders participated in a pro-neutrality, anti-membership riot in March 1949. The creation of NATO can be seen as the primary institutional consequence of a school of thought called Atlanticism which stressed the importance of trans-Atlantic cooperation.[13]

The members agreed that an armed attack against any one of them in Europe or North America would be considered an attack against them all. Consequently, they agreed that, if an armed attack occurred, each of them, in exercise of the right of individual or collective self-defence, would assist the member being attacked, taking such action as it deemed necessary, including the use of armed force, to restore and maintain the security of the North Atlantic area. The treaty does not require members to respond with military action against an aggressor. Although obliged to respond, they maintain the freedom to choose the method by which they do so. This differs from Article IV of the Treaty of Brussels, which clearly states that the response will be military in nature. It is nonetheless assumed that NATO members will aid the attacked member militarily. The treaty was later clarified to include both the member's territory and their "vessels, forces or aircraft" above the Tropic of Cancer, including some Overseas departments of France.[14]

The creation of NATO brought about some standardization of allied military terminology, procedures, and technology, which in many cases meant European countries adopting US practices. The roughly 1300 Standardization Agreements (STANAG) codified many of the common practices that NATO has achieved. Hence, the 7.62×51mm NATO rifle cartridge was introduced in the 1950s as a standard firearm cartridge among many NATO countries. Fabrique Nationale de Herstal's FAL, which used 7.62 NATO cartridge, was adopted by 75 countries, including many outside of NATO.[15] Also, aircraft marshalling signals were standardized, so that any NATO aircraft could land at any NATO base. Other standards such as the NATO phonetic alphabet have made their way beyond NATO into civilian use.

Cold War

The outbreak of the Korean War in June 1950 was crucial for NATO as it raised the apparent threat of all Communist countries working together, and forced the alliance to develop concrete military plans.[16] Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE) was formed to direct forces in Europe, and began work under Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower in January 1951.[17] In September 1950, the NATO Military Committee called for an ambitious buildup of conventional forces to meet the Soviets, subsequently reaffirming this position at the February 1952 meeting of the North Atlantic Council in Lisbon. The Lisbon conference, seeking to provide the forces necessary for NATO's Long-Term Defence Plan, called for an expansion to ninety-six divisions. However this requirement was dropped the following year to roughly thirty-five divisions with heavier use to be made of nuclear weapons. At this time, NATO could call on about fifteen ready divisions in Central Europe, and another ten in Italy and Scandinavia.[18][19] Also at Lisbon, the post of Secretary General of NATO as the organization's chief civilian was created, and Lord Ismay was eventually appointed to the post.[20]

In September 1952, the first major NATO maritime exercises began; Exercise Mainbrace brought together 200 ships and over 50,000 personnel to practice the defence of Denmark and Norway.[21] Other major exercises that followed included Exercise Grand Slam and Exercise Longstep, naval and amphibious exercises in the Mediterranean Sea, Italic Weld, a combined air-naval-ground exercise in northern Italy, Grand Repulse, involving the British Army on the Rhine (BAOR), the Netherlands Corps and Allied Air Forces Central Europe (AAFCE), Monte Carlo, a simulated atomic air-ground exercise involving the Central Army Group, and Weldfast, a combined amphibious landing exercise in the Mediterranean Sea involving American, British, Greek, Italian and Turkish naval forces.[22]

Greece and Turkey also joined the alliance in 1952, forcing a series of controversial negotiations, in which the United States and Britain were the primary disputants, over how to bring the two countries into the military command structure.[17] While this overt military preparation was going on, covert stay-behind arrangements initially made by the Western European Union to continue resistance after a successful Soviet invasion, including Operation Gladio, were transferred to NATO control. Ultimately unofficial bonds began to grow between NATO's armed forces, such as the NATO Tiger Association and competitions such as the Canadian Army Trophy for tank gunnery.[23][24]

In 1954, the Soviet Union suggested that it should join NATO to preserve peace in Europe.[25] The NATO countries, fearing that the Soviet Union's motive was to weaken the alliance, ultimately rejected this proposal.

On 17 December 1954, the North Atlantic Council approved MC 48, a key document in the evolution of NATO nuclear thought. MC 48 emphasized that NATO would have to use atomic weapons from the outset of a war with the Soviet Union whether or not the Soviets chose to use them first. This gave SACEUR the same prerogatives for automatic use of nuclear weapons as existed for the commander-in-chief of the US Strategic Air Command.

The incorporation of West Germany into the organization on 9 May 1955 was described as "a decisive turning point in the history of our continent" by Halvard Lange, Foreign Affairs Minister of Norway at the time.[26] A major reason for Germany's entry into the alliance was that without German manpower, it would have been impossible to field enough conventional forces to resist a Soviet invasion.[27] One of its immediate results was the creation of the Warsaw Pact, which was signed on 14 May 1955 by the Soviet Union, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Bulgaria, Romania, Albania, and East Germany, as a formal response to this event, thereby delineating the two opposing sides of the Cold War.

Three major exercises were held concurrently in the northern autumn of 1957. Operation Counter Punch, Operation Strikeback, and Operation Deep Water were the most ambitious military undertaking for the alliance to date, involving more than 250,000 men, 300 ships, and 1,500 aircraft operating from Norway to Turkey.[28]

French withdrawal

NATO's unity was breached early in its history with a crisis occurring during Charles de Gaulle's presidency of France.[29] De Gaulle protested against the USA's strong role in the organization and what he perceived as a special relationship between it and the United Kingdom. In a memorandum sent to President Dwight D. Eisenhower and Prime Minister Harold Macmillan on 17 September 1958, he argued for the creation of a tripartite directorate that would put France on an equal footing with the US and the UK.[30]

Considering the response to be unsatisfactory, de Gaulle began constructing an independent defence force for his country. He wanted to give France, in the event of an East German incursion into West Germany, the option of coming to a separate peace with the Eastern bloc instead of being drawn into a larger NATO–Warsaw Pact war.[31] In February 1959, France withdrew its Mediterranean Fleet from NATO command,[32] and later banned the stationing of foreign nuclear weapons on French soil. This caused the United States to transfer two hundred military aircraft out of France and return control of the air force bases that had operated in France since 1950 to the French by 1967.

Though France showed solidarity with the rest of NATO during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, de Gaulle continued his pursuit of an independent defence by removing France's Atlantic and Channel fleets from NATO command.[33] In 1966, all French armed forces were removed from NATO's integrated military command, and all non-French NATO troops were asked to leave France. US Secretary of State Dean Rusk was later quoted as asking de Gaulle whether his order included "the bodies of American soldiers in France's cemeteries?"[34] This withdrawal forced the relocation of SHAPE from Rocquencourt, near Paris, to Casteau, north of Mons, Belgium, by 16 October 1967.[35] France remained a member of the alliance, and committed to the defence of Europe from possible Warsaw Pact attack with its own forces stationed in the Federal Republic of Germany throughout the Cold War. A series of secret accords between US and French officials, the Lemnitzer–Ailleret Agreements, detailed how French forces would dovetail back into NATO's command structure should East-West hostilities break out.[36]

France announced their return to full participation at the 2009 Strasbourg/ Kehl Summit.[37]

Détente and escalation

During most of the Cold War, NATO's watch against the Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact did not actually lead to direct military action. On 1 July 1968, the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty opened for signature: NATO argued that its nuclear sharing arrangements did not breach the treaty as US forces controlled the weapons until a decision was made to go to war, at which point the treaty would no longer be controlling. Few states knew of the NATO nuclear sharing arrangements at that time, and they were not challenged. In May 1978, NATO countries officially defined two complementary aims of the Alliance, to maintain security and pursue détente. This was supposed to mean matching defences at the level rendered necessary by the Warsaw Pact's offensive capabilities without spurring a further arms race.[38]

On 12 December 1979, in light of a build-up of Warsaw Pact nuclear capabilities in Europe, ministers approved the deployment of US GLCM cruise missiles and Pershing II theatre nuclear weapons in Europe. The new warheads were also meant to strengthen the western negotiating position regarding nuclear disarmament. This policy was called the Dual Track policy.[39] Similarly, in 1983–84, responding to the stationing of Warsaw Pact SS-20 medium-range missiles in Europe, NATO deployed modern Pershing II missiles tasked to hit military targets such as tank formations in the event of war.[40] This action led to peace movement protests throughout Western Europe, and support for the deployment wavered as many doubted whether the push for deployment could be sustained.

The membership of the organization at this time remained largely static. In 1974, as a consequence of the Turkish invasion of Cyprus, Greece withdrew its forces from NATO's military command structure but, with Turkish cooperation, were readmitted in 1980. The Falklands War between the United Kingdom and Argentina did not result in NATO involvement because article 6 of the North Atlantic Treaty specifies that collective self-defence is only applicable to attacks on member state territories north of the Tropic of Cancer.[41] On 30 May 1982, NATO gained a new member when, following a referendum, the newly democratic Spain joined the alliance. At the peak of the Cold War, 16 member nations maintained an approximate strength of 5,252,800 active military, including as many as 435,000 forward deployed US forces, under a command structure that reached a peak of 78 headquarters, organized into four echelons.[42]

After the Cold War

The Revolutions of 1989 and the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact in 1991 removed the de facto main adversary of NATO and caused a strategic re-evaluation of NATO's purpose, nature, tasks, and their focus on the continent of Europe. This shift started with the 1990 signing in Paris of the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe between NATO and the Soviet Union, which mandated specific military reductions across the continent that continued after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in December 1991.[43] At that time, European countries accounted for 34 percent of NATO's military spending; by 2012, this had fallen to 21 percent.[44] NATO also began a gradual expansion to include newly autonomous Central and Eastern European nations, and extended its activities into political and humanitarian situations that had not formerly been NATO concerns.

The first post-Cold War expansion of NATO came with German reunification on 3 October 1990, when the former East Germany became part of the Federal Republic of Germany and the alliance. This had been agreed in the Two Plus Four Treaty earlier in the year. To secure Soviet approval of a united Germany remaining in NATO, it was agreed that foreign troops and nuclear weapons would not be stationed in the east, and there are diverging views on whether negotiators gave commitments regarding further NATO expansion east.[45] Jack Matlock, American ambassador to the Soviet Union during its final years, said that the West gave a "clear commitment" not to expand, and declassified documents indicate that Soviet negotiators were given the impression that NATO membership was off the table for countries such as Czechoslovakia, Hungary, or Poland.[46] In 1996, Gorbachev wrote in his Memoirs, that "during the negotiations on the unification of Germany they gave assurances that NATO would not extend its zone of operation to the east,"[47] and repeated this view in an interview in 2008.[48] According to Robert Zoellick, a State Department official involved in the Two Plus Four negotiating process, this appears to be a misperception, and no formal commitment regarding enlargement was made.[49]

As part of post-Cold War restructuring, NATO's military structure was cut back and reorganized, with new forces such as the Headquarters Allied Command Europe Rapid Reaction Corps established. The changes brought about by the collapse of the Soviet Union on the military balance in Europe were recognized in the Adapted Conventional Armed Forces in Europe Treaty, which was signed in 1999. The policies of French President Nicolas Sarkozy resulted in a major reform of France's military position, culminating with the return to full membership on 4 April 2009, which also included France rejoining the NATO Military Command Structure, while maintaining an independent nuclear deterrent.[36][50]

Enlargement and reform

Between 1994 and 1997, wider forums for regional cooperation between NATO and its neighbors were set up, like the Partnership for Peace, the Mediterranean Dialogue initiative and the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council. In 1998, the NATO-Russia Permanent Joint Council was established. On 8 July 1997, three former communist countries, Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Poland, were invited to join NATO, which each did in 1999. Membership went on expanding with the accession of seven more Central and Eastern European countries to NATO: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovenia, Slovakia, Bulgaria, and Romania. They were first invited to start talks of membership during the 2002 Prague summit, and joined NATO on 29 March 2004, shortly before the 2004 Istanbul summit. In Istanbul, NATO launched the Istanbul Cooperation Initiative with four Persian Gulf nations.[51]

New NATO structures were also formed while old ones were abolished. In 1997, NATO reached agreement on a significant downsizing of its command structure from 65 headquarters to just 20.[52] The NATO Response Force (NRF) was launched at the 2002 Prague summit on 21 November, the first summit in a former Comecon country. On 19 June 2003, a further restructuring of the NATO military commands began as the Headquarters of the Supreme Allied Commander, Atlantic were abolished and a new command, Allied Command Transformation (ACT), was established in Norfolk, Virginia, United States, and the Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE) became the Headquarters of Allied Command Operations (ACO). ACT is responsible for driving transformation (future capabilities) in NATO, whilst ACO is responsible for current operations.[53] In March 2004, NATO's Baltic Air Policing began, which supported the sovereignty of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia by providing jet fighters to react to any unwanted aerial intrusions. Eight multinational jet fighters are based in Lithuania, the number of which was increased from four in 2014.[54]

The 2006 Riga summit was held in Riga, Latvia, and highlighted the issue of energy security. It was the first NATO summit to be held in a country that had been part of the Soviet Union. At the April 2008 summit in Bucharest, Romania, NATO agreed to the accession of Croatia and Albania and both countries joined NATO in April 2009. Ukraine and Georgia were also told that they could eventually become members.[55] The issue of Georgian and Ukrainian membership in NATO prompted harsh criticism from Russia, as did NATO plans for a missile defence system. Studies for this system began in 2002, with negotiations centered on anti-ballistic missiles being stationed in Poland and the Czech Republic. Though NATO leaders gave assurances that the system was not targeting Russia, both presidents Vladimir Putin and Dmitry Medvedev criticized it as a threat.[56]

In 2009, US President Barack Obama proposed using the ship-based Aegis Combat System, though this plan still includes stations being built in Turkey, Spain, Portugal, Romania, and Poland.[57] NATO will also maintain the "status quo" in its nuclear deterrent in Europe by upgrading the targeting capabilities of the "tactical" B61 nuclear bombs stationed there and deploying them on the stealthier Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II.[58][59] Following the 2014 Crimean crisis, NATO committed to forming a new "spearhead" force of 5,000 troops at bases in Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia, Poland, Romania, and Bulgaria.[60][61] On June 15, 2016, NATO officially recognized cyberwarfare as an operational domain of war, just like land, sea and aerial warfare. This means that any cyber attack on NATO members can trigger Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty.[62]

Military operations

Early operations

No military operations were conducted by NATO during the Cold War. Following the end of the Cold War, the first operations, Anchor Guard in 1990 and Ace Guard in 1991, were prompted by the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. Airborne Early Warning aircraft were sent to provide coverage of South Eastern Turkey, and later a quick-reaction force was deployed to the area.[63]

Bosnia and Herzegovina intervention

The Bosnian War began in 1992, as a result of the Breakup of Yugoslavia. The deteriorating situation led to United Nations Security Council Resolution 816 on 9 October 1992, ordering a no-fly zone over central Bosnia and Herzegovina, which NATO began enforcing on 12 April 1993 with Operation Deny Flight. From June 1993 until October 1996, Operation Sharp Guard added maritime enforcement of the arms embargo and economic sanctions against the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. On 28 February 1994, NATO took its first wartime action by shooting down four Bosnian Serb aircraft violating the no-fly zone.[64]

On 10 and 11 April 1994, during the Bosnian War, the United Nations Protection Force called in air strikes to protect the Goražde safe area, resulting in the bombing of a Bosnian Serb military command outpost near Goražde by two US F-16 jets acting under NATO direction.[65] This resulted in the taking of 150 U.N. personnel hostage on 14 April.[66][67] On 16 April a British Sea Harrier was shot down over Goražde by Serb forces.[68] A two-week NATO bombing campaign, Operation Deliberate Force, began in August 1995 against the Army of the Republika Srpska, after the Srebrenica massacre.[69]

NATO air strikes that year helped bring the Yugoslav wars to an end, resulting in the Dayton Agreement in November 1995.[69] As part of this agreement, NATO deployed a UN-mandated peacekeeping force, under Operation Joint Endeavor, named IFOR. Almost 60,000 NATO troops were joined by forces from non-NATO nations in this peacekeeping mission. This transitioned into the smaller SFOR, which started with 32,000 troops initially and ran from December 1996 until December 2004, when operations were then passed onto European Union Force Althea.[70] Following the lead of its member nations, NATO began to award a service medal, the NATO Medal, for these operations.[71]

Kosovo intervention

In an effort to stop Slobodan Milošević's Serbian-led crackdown on KLA separatists and Albanian civilians in Kosovo, the United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 1199 on 23 September 1998 to demand a ceasefire. Negotiations under US Special Envoy Richard Holbrooke broke down on 23 March 1999, and he handed the matter to NATO,[72] which started a 78-day bombing campaign on 24 March 1999.[73] Operation Allied Force targeted the military capabilities of what was then the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. During the crisis, NATO also deployed one of its international reaction forces, the ACE Mobile Force (Land), to Albania as the Albania Force (AFOR), to deliver humanitarian aid to refugees from Kosovo.[74]

Though the campaign was criticized for high civilian casualties, including bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade, Milošević finally accepted the terms of an international peace plan on 3 June 1999, ending the Kosovo War. On 11 June, Milošević further accepted UN resolution 1244, under the mandate of which NATO then helped establish the KFOR peacekeeping force. Nearly one million refugees had fled Kosovo, and part of KFOR's mandate was to protect the humanitarian missions, in addition to deterring violence.[74][75] In August–September 2001, the alliance also mounted Operation Essential Harvest, a mission disarming ethnic Albanian militias in the Republic of Macedonia.[76] As of 1 December 2013[update], 4,882 KFOR soldiers, representing 31 countries, continue to operate in the area.[77]

The US, the UK, and most other NATO countries opposed efforts to require the U.N. Security Council to approve NATO military strikes, such as the action against Serbia in 1999, while France and some others claimed that the alliance needed UN approval.[78] The US/UK side claimed that this would undermine the authority of the alliance, and they noted that Russia and China would have exercised their Security Council vetoes to block the strike on Yugoslavia, and could do the same in future conflicts where NATO intervention was required, thus nullifying the entire potency and purpose of the organization. Recognizing the post-Cold War military environment, NATO adopted the Alliance Strategic Concept during its Washington summit in April 1999 that emphasized conflict prevention and crisis management.[79]

Afghanistan War

The September 11th attacks in the United States caused NATO to invoke Article 5 of the NATO Charter for the first time in the organization's history. The Article says that an attack on any member shall be considered to be an attack on all. The invocation was confirmed on 4 October 2001 when NATO determined that the attacks were indeed eligible under the terms of the North Atlantic Treaty.[80] The eight official actions taken by NATO in response to the attacks included Operation Eagle Assist and Operation Active Endeavour, a naval operation in the Mediterranean Sea which is designed to prevent the movement of terrorists or weapons of mass destruction, as well as enhancing the security of shipping in general which began on 4 October 2001.[81]

The alliance showed unity: on 16 April 2003, NATO agreed to take command of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF), which includes troops from 42 countries. The decision came at the request of Germany and the Netherlands, the two nations leading ISAF at the time of the agreement, and all nineteen NATO ambassadors approved it unanimously. The handover of control to NATO took place on 11 August, and marked the first time in NATO's history that it took charge of a mission outside the north Atlantic area.[82]

ISAF was initially charged with securing Kabul and surrounding areas from the Taliban, al Qaeda and factional warlords, so as to allow for the establishment of the Afghan Transitional Administration headed by Hamid Karzai. In October 2003, the UN Security Council authorized the expansion of the ISAF mission throughout Afghanistan,[83] and ISAF subsequently expanded the mission in four main stages over the whole of the country.[84]

On 31 July 2006, the ISAF additionally took over military operations in the south of Afghanistan from a US-led anti-terrorism coalition.[85] Due to the intensity of the fighting in the south, in 2011 France allowed a squadron of Mirage 2000 fighter/attack aircraft to be moved into the area, to Kandahar, in order to reinforce the alliance's efforts.[86] During its 2012 Chicago Summit, NATO endorsed a plan to end the Afghanistan war and to remove the NATO-led ISAF Forces by the end of December 2014.[87] ISAF was disestablished in December 2014 and replaced by the follow-on training Resolute Support Mission.

Iraq training mission

In August 2004, during the Iraq War, NATO formed the NATO Training Mission – Iraq, a training mission to assist the Iraqi security forces in conjunction with the US led MNF-I.[88] The NATO Training Mission-Iraq (NTM-I) was established at the request of the Iraqi Interim Government under the provisions of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1546. The aim of NTM-I was to assist in the development of Iraqi security forces training structures and institutions so that Iraq can build an effective and sustainable capability that addresses the needs of the nation. NTM-I was not a combat mission but is a distinct mission, under the political control of NATO's North Atlantic Council. Its operational emphasis was on training and mentoring. The activities of the mission were coordinated with Iraqi authorities and the US-led Deputy Commanding General Advising and Training, who was also dual-hatted as the Commander of NTM-I. The mission officially concluded on 17 December 2011.[89]

Gulf of Aden anti-piracy

Beginning on 17 August 2009, NATO deployed warships in an operation to protect maritime traffic in the Gulf of Aden and the Indian Ocean from Somali pirates, and help strengthen the navies and coast guards of regional states. The operation was approved by the North Atlantic Council and involves warships primarily from the United States though vessels from many other nations are also included. Operation Ocean Shield focuses on protecting the ships of Operation Allied Provider which are distributing aid as part of the World Food Programme mission in Somalia. Russia, China and South Korea have sent warships to participate in the activities as well.[90][91] The operation seeks to dissuade and interrupt pirate attacks, protect vessels, and abetting to increase the general level of security in the region.[92]

Libya intervention

During the Libyan Civil War, violence between protestors and the Libyan government under Colonel Muammar Gaddafi escalated, and on 17 March 2011 led to the passage of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1973, which called for a ceasefire, and authorized military action to protect civilians. A coalition that included several NATO members began enforcing a no-fly zone over Libya shortly afterwards. On 20 March 2011, NATO states agreed on enforcing an arms embargo against Libya with Operation Unified Protector using ships from NATO Standing Maritime Group 1 and Standing Mine Countermeasures Group 1,[93] and additional ships and submarines from NATO members.[94] They would "monitor, report and, if needed, interdict vessels suspected of carrying illegal arms or mercenaries".[93]

On 24 March, NATO agreed to take control of the no-fly zone from the initial coalition, while command of targeting ground units remained with the coalition's forces.[95][96] NATO began officially enforcing the UN resolution on 27 March 2011 with assistance from Qatar and the United Arab Emirates.[97] By June, reports of divisions within the alliance surfaced as only eight of the 28 member nations were participating in combat operations,[98] resulting in a confrontation between US Defense Secretary Robert Gates and countries such as Poland, Spain, the Netherlands, Turkey, and Germany to contribute more, the latter believing the organization has overstepped its mandate in the conflict.[99][100][101] In his final policy speech in Brussels on 10 June, Gates further criticized allied countries in suggesting their actions could cause the demise of NATO.[102] The German foreign ministry pointed to "a considerable [German] contribution to NATO and NATO-led operations" and to the fact that this engagement was highly valued by President Obama.[103]

While the mission was extended into September, Norway that day announced it would begin scaling down contributions and complete withdrawal by 1 August.[104] Earlier that week it was reported Danish air fighters were running out of bombs.[105][106] The following week, the head of the Royal Navy said the country's operations in the conflict were not sustainable.[107] By the end of the mission in October 2011, after the death of Colonel Gaddafi, NATO planes had flown about 9,500 strike sorties against pro-Gaddafi targets.[108][109] A report from the organization Human Rights Watch in May 2012 identified at least 72 civilians killed in the campaign.[110] Following a coup d'état attempt in October 2013, Libyan Prime Minister Ali Zeidan requested technical advice and trainers from NATO to assist with ongoing security issues.[111]

Participating countries

Members

NATO has twenty-eight members, mainly in Europe and North America. Some of these countries also have territory on multiple continents, which can be covered only as far south as the Tropic of Cancer in the Atlantic Ocean, which defines NATO's "area of responsibility" under Article 6 of the North Atlantic Treaty. During the original treaty negotiations, the United States insisted that colonies like the Belgian Congo be excluded from the treaty.[112][113] French Algeria was however covered until their independence on 3 July 1962.[114] Twelve of these twenty-eight are original members who joined in 1949, while the other sixteen joined in one of seven enlargement rounds. Few members spend more than two percent of their gross domestic product on defence,[115] with the United States accounting for three quarters of NATO defense spending.[116]

From the mid-1960s to the mid-1990s, France pursued a military strategy of independence from NATO under a policy dubbed "Gaullo-Mitterrandism".[citation needed] Nicolas Sarkozy negotiated the return of France to the integrated military command and the Defence Planning Committee in 2009, the latter being disbanded the following year. France remains the only NATO member outside the Nuclear Planning Group and unlike the United States and the United Kingdom, will not commit its nuclear-armed submarines to the alliance.[36][50]

Enlargement

New membership in the alliance has been largely from Central and Eastern Europe, including former members of the Warsaw Pact. Accession to the alliance is governed with individual Membership Action Plans, and requires approval by each current member. NATO currently has three candidate countries that are in the process of joining the alliance: Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, and the Republic of Macedonia. On 2 December 2015, NATO Foreign Ministers decided to invite Montenegro to start accession talks to become the 29th member of the Alliance.[117] In NATO official statements, the Republic of Macedonia is always referred to as the "former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia", with a footnote stating that "Turkey recognizes the Republic of Macedonia under its constitutional name". Though Macedonia completed its requirements for membership at the same time as Croatia and Albania, NATO's most recent members, its accession was blocked by Greece pending a resolution of the Macedonia naming dispute.[118] In order to support each other in the process, new and potential members in the region formed the Adriatic Charter in 2003.[119] Georgia was also named as an aspiring member, and was promised "future membership" during the 2008 summit in Bucharest,[120] though in 2014, US President Barack Obama said the country was not "currently on a path" to membership.[121]

Russia continues to oppose further expansion, seeing it as inconsistent with understandings between Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev and European and American negotiators that allowed for a peaceful German reunification.[46] NATO's expansion efforts are often seen by Moscow leaders as a continuation of a Cold War attempt to surround and isolate Russia,[122] though they have also been criticised in the West.[123] Ukraine's relationship with NATO and Europe has been politically divisive, and contributed to "Euromaidan" protests that saw the ousting of pro-Russian President Viktor Yanukovych in 2014. In March 2014, Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk reiterated the government's stance that Ukraine is not seeking NATO membership.[124] Ukraine's president subsequently signed a bill dropping his nation's nonaligned status in order to pursue NATO membership, but signaled that it would hold a referendum before seeking to join.[125] Ukraine is one of eight countries in Eastern Europe with an Individual Partnership Action Plan. IPAPs began in 2002, and are open to countries that have the political will and ability to deepen their relationship with NATO.[126]

Partnerships

The Partnership for Peace (PfP) programme was established in 1994 and is based on individual bilateral relations between each partner country and NATO: each country may choose the extent of its participation.[128] Members include all current and former members of the Commonwealth of Independent States.[129] The Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council (EAPC) was first established on 29 May 1997, and is a forum for regular coordination, consultation and dialogue between all fifty participants.[130] The PfP programme is considered the operational wing of the Euro-Atlantic Partnership.[128] Other third countries also have been contacted for participation in some activities of the PfP framework such as Afghanistan.[131]

The European Union (EU) signed a comprehensive package of arrangements with NATO under the Berlin Plus agreement on 16 December 2002. With this agreement the EU was given the possibility to use NATO assets in case it wanted to act independently in an international crisis, on the condition that NATO itself did not want to act—the so-called "right of first refusal".[132] It provides a "double framework" for the EU countries that are also linked with the PfP programme. Additionally, NATO cooperates and discusses its activities with numerous other non-NATO members. The Mediterranean Dialogue was established in 1994 to coordinate in a similar way with Israel and countries in North Africa. The Istanbul Cooperation Initiative was announced in 2004 as a dialog forum for the Middle East along the same lines as the Mediterranean Dialogue. The four participants are also linked through the Gulf Cooperation Council.[133]

Political dialogue with Japan began in 1990, and since then, the Alliance has gradually increased its contact with countries that do not form part of any of these cooperation initiatives.[134] In 1998, NATO established a set of general guidelines that do not allow for a formal institutionalisation of relations, but reflect the Allies' desire to increase cooperation. Following extensive debate, the term "Contact Countries" was agreed by the Allies in 2000. By 2012, the Alliance had broadened this group, which meets to discuss issues such as counter-piracy and technology exchange, under the names "partners across the globe" or "global partners".[135][136] Australia and New Zealand, both contact countries, are also members of the AUSCANNZUKUS strategic alliance, and similar regional or bilateral agreements between contact countries and NATO members also aid cooperation. In June 2013, Colombia and NATO signed an Agreement on the Security of Information to explore future cooperation and consultation in areas of common interest; Colombia became the first and only Latin American country to cooperate with NATO.[137]

Structures

The main headquarters of NATO is located on Boulevard Léopold III/Leopold III-laan, B-1110 Brussels, which is in Haren, part of the City of Brussels municipality.[138] A new €750 million headquarters building is, as of 2014[update], under construction across from the current complex, and is due for completion by 2016.[139] Problems in the current building stem from its hurried construction in 1967, when NATO was forced to move its headquarters from Porte Dauphine in Paris, France following the French withdrawal.[140][35]

The staff at the Headquarters is composed of national delegations of member countries and includes civilian and military liaison offices and officers or diplomatic missions and diplomats of partner countries, as well as the International Staff and International Military Staff filled from serving members of the armed forces of member states.[141] Non-governmental citizens' groups have also grown up in support of NATO, broadly under the banner of the Atlantic Council/Atlantic Treaty Association movement.

NATO Council

Like any alliance, NATO is ultimately governed by its 28 member states. However, the North Atlantic Treaty and other agreements outline how decisions are to be made within NATO. Each of the 28 members sends a delegation or mission to NATO's headquarters in Brussels, Belgium.[142] The senior permanent member of each delegation is known as the Permanent Representative and is generally a senior civil servant or an experienced ambassador (and holding that diplomatic rank). Several countries have diplomatic missions to NATO through embassies in Belgium.

Together, the Permanent Members form the North Atlantic Council (NAC), a body which meets together at least once a week and has effective governance authority and powers of decision in NATO. From time to time the Council also meets at higher level meetings involving foreign ministers, defence ministers or heads of state or government (HOSG) and it is at these meetings that major decisions regarding NATO's policies are generally taken. However, it is worth noting that the Council has the same authority and powers of decision-making, and its decisions have the same status and validity, at whatever level it meets. France, Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom and the United States are together referred to as the Quint, which is an informal discussion group within NATO. NATO summits also form a further venue for decisions on complex issues, such as enlargement.[143]

The meetings of the North Atlantic Council are chaired by the Secretary General of NATO and, when decisions have to be made, action is agreed upon on the basis of unanimity and common accord. There is no voting or decision by majority. Each nation represented at the Council table or on any of its subordinate committees retains complete sovereignty and responsibility for its own decisions.

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| † Acting Secretary General | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

NATO Parliamentary Assembly

The body that sets broad strategic goals for NATO is the NATO Parliamentary Assembly (NATO-PA) which meets at the Annual Session, and one other during the year, and is the organ that directly interacts with the parliamentary structures of the national governments of the member states which appoint Permanent Members, or ambassadors to NATO. The NATO Parliamentary Assembly is made up of legislators from the member countries of the North Atlantic Alliance as well as thirteen associate members. Karl A. Lamers, German Deputy Chairman of the Defence Committee of the Bundestag and a member of the Christian Democratic Union, became president of the assembly in 2010.[146] It is however officially a different structure from NATO, and has as aim to join together deputies of NATO countries in order to discuss security policies on the NATO Council.

The Assembly is the political integration body of NATO that generates political policy agenda setting for the NATO Council via reports of its five committees:

- Committee on the Civil Dimension of Security

- Defence and Security Committee

- Economics and Security Committee

- Political Committee

- Science and Technology Committee

These reports provide impetus and direction as agreed upon by the national governments of the member states through their own national political processes and influencers to the NATO administrative and executive organizational entities.

Military structures

NATO's military operations are directed by the Chairman of the NATO Military Committee, and split into two Strategic Commands commanded by a senior US officer and (currently) a senior French officer[147] assisted by a staff drawn from across NATO. The Strategic Commanders are responsible to the Military Committee for the overall direction and conduct of all Alliance military matters within their areas of command.[53]

Each country's delegation includes a Military Representative, a senior officer from each country's armed forces, supported by the International Military Staff. Together the Military Representatives form the Military Committee, a body responsible for recommending to NATO's political authorities those measures considered necessary for the common defence of the NATO area. Its principal role is to provide direction and advice on military policy and strategy. It provides guidance on military matters to the NATO Strategic Commanders, whose representatives attend its meetings, and is responsible for the overall conduct of the military affairs of the Alliance under the authority of the Council.[148] The Chairman of the NATO Military Committee is Petr Pavel of the Czech Republic, since 2015. Like the Council, from time to time the Military Committee also meets at a higher level, namely at the level of Chiefs of Defence, the most senior military officer in each nation's armed forces. Until 2008 the Military Committee excluded France, due to that country's 1966 decision to remove itself from NATO's integrated military structure, which it rejoined in 1995. Until France rejoined NATO, it was not represented on the Defence Planning Committee, and this led to conflicts between it and NATO members.[149] Such was the case in the lead up to Operation Iraqi Freedom.[150] The operational work of the Committee is supported by the International Military Staff.

The structure of NATO evolved throughout the Cold War and its aftermath. An integrated military structure for NATO was first established in 1950 as it became clear that NATO would need to enhance its defences for the longer term against a potential Soviet attack. In April 1951, Allied Command Europe and its headquarters (SHAPE) were established; later, four subordinate headquarters were added in Northern and Central Europe, the Southern Region, and the Mediterranean.[151]

From the 1950s to 2003, the Strategic Commanders were the Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR) and the Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic (SACLANT). The current arrangement is to separate responsibility between Allied Command Transformation (ACT), responsible for transformation and training of NATO forces, and Allied Command Operations (ACO), responsible for NATO operations worldwide.[152] Starting in late 2003 NATO has restructured how it commands and deploys its troops by creating several NATO Rapid Deployable Corps, including Eurocorps, I. German/Dutch Corps, Multinational Corps Northeast, and NATO Rapid Deployable Italian Corps among others, as well as naval High Readiness Forces (HRFs), which all report to Allied Command Operations.[153]

In early 2015, in the wake of the War in Donbass, meetings of NATO ministers decided that Multinational Corps Northeast would be augmented so as to develop greater capabilities, to, if thought necessary, prepare to defend the Baltic States, and that a new Multi-National Division Southeast would be established in Romania. Six NATO Force Integration Units would also be established to coordinate preparations for defence of new Eastern members of NATO.[154]

References

- ^ "English and French shall be the official languages for the entire North Atlantic Treaty Organization.", Final Communiqué following the meeting of the North Atlantic Council on 17 September 1949. "(..) the English and French texts [of the Treaty] are equally authentic (...)" The North Atlantic Treaty, Article 14

- ^ "The Official motto of NATO". NATO. 20 January 2011. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- ^ "The SIPRI Military Expenditure Database". Milexdata.sipri.org. Archived from the original on 28 March 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Erlanger, Steven (26 March 2014). "Europe Begins to Rethink Cuts to Military Spending". nytimes.com. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

Last year, only a handful of NATO countries met the target, according to NATO figures, including the United States, at 4.1 percent, and Britain, at 2.4 percent.

- ^ "Invocation of Article 5 confirmed". North Atlantic Treaty Organization. 3 October 2001. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ^ "Counter-piracy operations". North Atlantic Treaty Organization. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- ^ Croft, Adrian (3 October 2012). "NATO demands halt to Syria aggression against Turkey". Reuters. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ^ "Statement by the North Atlantic Council following meeting under article 4 of the Washington Treaty". NATO Newsroom. 4 March 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ^ Ford, Dana (26 July 2015). "Turkey calls for rare NATO talks after attacks along Syrian border". www.cnn.com. CNN. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- ^ Isby & Kamps Jr. 1985, p. 13.

- ^ "A short history of NATO". NATO. 2 April 2012. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ Reynolds 1994, p. 13.

- ^ Straus, Ira (June 2005). "Atlanticism as the core 20 th century U.S. strategy for internationalism" (PDF). Streit Council. Annual Meeting of the Society of Historians of American Foreign Relations. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ "Protocol to the North Atlantic Treaty on the Accession of Greece and Turkey". NATO. 4 April 1949. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ^ Willbanks 2004, pp. 129–130.

- ^ Isby & Kamps Jr. 1985, pp. 13–14.

- ^ a b Ismay, Hastings (4 September 2001). "NATO the first five years 1949-1954". NATO. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ Osgood 1962, p. 76.

- ^ Park 1986, p. 28.

- ^ "NATO: The Man with the Oilcan". Time. 24 March 1952. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ^ Baldwin, Hanson (28 September 1952). "Navies Meet the Test in Operation Mainbrace". New York Times: E7. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ Ismay, Hastings (17 September 2001). "The increase in strength". NATO the first five years 1949-1954. NATO. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ^ "Organisation". NATO Tiger Association. 2013. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ^ "Historical Overview". Canadian Army Trophy. 5 October 2012. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ^ "Fast facts about NATO". CBC News. 6 April 2009. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- ^ "West Germany accepted into Nato". BBC News. 9 May 2011. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ^ Isby & Kamps Jr. 1985, p. 15.

- ^ "Emergency Call". Time. 30 September 1957. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- ^ Garret Martin, "The 1967 withdrawal from NATO – a cornerstone of de Gaulle's grand strategy?" Journal of Transatlantic Studies (2011) 9#3 pp 232–243. doi:10.1080/14794012.2011.593819

- ^ Wenger, Nuenlist & Locher 2007, pp. 67–69.

- ^ Dowd, Alan (22 September 2009). "Not Enough NATO In Afghanistan". CBS News. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ^ National Defense University 1997, p. 50.

- ^ van der Eyden 2003, pp. 104–106.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1988, p. 421.

- ^ a b Le Blévennec, François (25 October 2011). "The Big Move". NATO Review. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ^ a b c Cody, Edward (12 March 2009). "After 43 Years, France to Rejoin NATO as Full Member". The Washington Post. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ^ "Defence Planning Committee (DPC) (Archived)". NATO. 11 November 2014. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ^ Garthoff 1994, pp. 659–661.

- ^ Njølstad 2004, pp. 280–282.

- ^ Njølstad 2004, pp. 278–279.

- ^ Kaplan 2004, pp. 89–91.

- ^ Weinrod, W. Bruce; Barry, Charles L. (September 2010). "NATO Command Structure: Considerations for the Future" (PDF). Center for Technology and National Security Policy. National Defense University. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ^ Harding, Luke (14 July 2007). "Kremlin tears up arms pact with Nato". The Observer. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ^ "The future of NATO: Bad timing". The Economist. 31 March 2012. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- ^ Sarotte, Mary Elise (September–October 2014). "A Broken Promise?". Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- ^ a b Klussmann, Uwe; Schepp, Matthias; Wiegrefe, Klaus (26 November 2009). "NATO's Eastward Expansion: Did the West Break Its Promise to Moscow?". Spiegel Online. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ Gorbachev 1996, p. 675.

- ^ Blomfield A and Smith M (6 May 2009). "Gorbachev: US could start new Cold War". Paris: The Telegraph. Retrieved 22 May 2009.

- ^ Zoellick, Robert B. (22 September 2000). "The Lessons of German Unification". The National Interest.

- ^ a b Stratton, Allegra (17 June 2008). "Sarkozy military plan unveiled". The Guardian. UK.

- ^ "History". NATO. 15 December 2011. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- ^ Albright, Madeleine (16 December 1997). "Statement by Secretary of State Madeleine K. Albright During the North Atlantic Council Ministerial Meeting". NATO. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ^ a b "Allied Command Operations (ACO)". NATO. 10 May 2013. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ^ Sytas, Andrius (29 March 2016). "NATO needs to beef up defense of Baltic airspace: top commander". Reuters. Retrieved 9 April 2016.

- ^ Archived 2008-04-07 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Englund, Will (23 March 2012). "Medvedev calls missile defense a threat to Russia". The Washington Post. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ "Part of NATO missile defense system goes live in Turkey". CNN. 16 January 2012. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ^ Norton-Taylor, Richard. "Nato plans to upgrade nuclear weapons 'expensive and unnecessary'." guardian.co.uk, 10 May 2012.

- ^ Becker, Markus. "US Nuclear Weapons Upgrades." Der Spiegel, 16 May 2012.

- ^ "Ukraine crisis: Nato bolsters Eastern Europe against Russia". BBC News. 5 February 2015. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- ^ "NATO Meets to Approve Strengthening Forces in Eastern Europe". Newsweek. Reuters. 5 February 2015. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- ^ Hardy, Catherine. "Cyberspace is officially a war zone – NATO". euronews. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ^ "NATO's Operations 1949 - Present" (PDF). NATO. 2009. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- ^ Zenko 2010, pp. 133–134.

- ^ Zenko 2010, p. 134.

- ^ NATO Handbook: Evolution of the Conflict, NATO, archived from the original on 7 November 2001

- ^ Rubin, Trudy (31 May 1995). "U.N. Must Stand Up To The Serbs". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved 5 September 2013.

- ^ Bethlehem & Weller 1997, p. liiv.

- ^ a b Zenko 2010, pp. 137–138

- ^ Clausson 2006, p. 94–97.

- ^ Tice, Jim (22 February 2009). "Thousands more now eligible for NATO Medal". Army Times. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ "Nato to strike Yugoslavia". BBC News. 24 March 1999. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- ^ Thorpe, Nick (24 March 2004). "UN Kosovo mission walks a tightrope". BBC News. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ a b "Operation Shining Hope". Global Security. 5 July 2011. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ "Kosovo Report Card". International Crisis Group. 28 August 2000. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ Helm, Toby (27 September 2001). "Macedonia mission a success, says Nato". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ "Kosovo Force (KFOR) Key Facts and Figures" (PDF). NATO. 1 December 2013. Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- ^ "NATO reaffirms power to take action without U.N. approval". CNN. 24 April 1999. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ^ "Allied Command Atlantic". NATO Handbook. NATO. Archived from the original on 13 August 2008. Retrieved 3 September 2008.

- ^ "NATO Update: Invocation of Article 5 confirmed – 2 October 2001". Nato.int. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ "NATO's Operations 1949-Present" (PDF). NATO. 22 January 2010. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ^ David P. Auerswald, and Stephen M. Saideman, eds. NATO in Afghanistan: Fighting Together, Fighting Alone (Princeton U.P., 2014)

- ^ "UNSC Resolution 1510, October 13, 2003" (PDF). Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ^ "ISAF Chronology". Nato.int. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ^ Morales, Alex (5 October 2006). "NATO Takes Control of East Afghanistan From U.S.-Led Coalition". Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ^ "La France et l'OTAN". Le Monde (in French). France. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- ^ "NATO sets "irreversible" but risky course to end Afghan war". Reuters. Reuters. 21 May 2012. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ^ Official Website

- ^ El Gamal, Rania (17 December 2011). "NATO closes up training mission in Iraq". Reuters. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ^ "Operation Ocean Shield". NATO. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ "2009 Operation Ocean Shield News Articles". NATO. October 2010. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ "Operation Ocean Shield purpose". 12 July 2016. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ^ a b "Statement by the NATO Secretary General on Libya arms embargo". NATO. 22 March 2011.

- ^ "Press briefing by NATO Spokesperson Oana Lungescu, Brigadier General Pierre St-Amand, Canadian Air Force and General Massimo Panizzi, spokesperson of the Chairman of the Military Committee". NATO. 23 March 2011.

- ^ "NATO reaches deal to take over Libya operation; allied planes hit ground forces". Washington Post. 25 March 2011.

- ^ "NATO to police Libya no-fly zone". 24 March 2011.

- ^ O'Sullivan, Arieh (31 March 2011). "UAE and Qatar pack an Arab punch in Libya operation". Jerusalem Post. se. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ^ "NATO strikes Tripoli, Gaddafi army close on Misrata", Khaled al-Ramahi. Malaysia Star. 9 June 2011. Retrieved 9 June 2011

- ^ Coughlin, Con (9 June 2011). "Political Gridlock at NATO", Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 9 June 2011

- ^ "Gates Calls on NATO Allies to Do More in Libya", Jim Garamone. US Department of Defense. 8 June 2011. Retrieved 9 June 2011

- ^ Cloud, David S. (9 June 2011). "Gates calls for more NATO allies to join Libya air campaign", Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 9 June 2011

- ^ Burns, Robert (10 June 2011). "Gates blasts NATO, questions future of alliance", Washington Times. Retrieved January 29, 2013

- ^ Birnbaum, Michael (10 June 2011). "Gates rebukes European allies in farewell speech", Washington Post. Retrieved 10 June 2011.

- ^ Amland, Bjoern H. (10 June 2011). "Norway to quit Libya operation by August", AP. Retrieved January 29, 2013

- ^ "Danish planes running out of bombs", Times of Malta. 10 June 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2011

- ^ "Danish Planes in Libya Running Out of Bombs: Report", Defense News. 9 June 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2011

- ^ "Navy chief: Britain cannot keep up its role in Libya air war due to cuts", James Kirkup. The Telegraph. 13 June 2011. Retrieved January 29, 2013

- ^ "NATO: Ongoing resistance by pro-Gadhafi forces in Libya is 'surprising'". The Washington Post. UPI. 11 October 2011. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ^ "NATO strategy in Libya may not work elsewhere". USA Today. 21 October 2011. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ^ Tharoor, Ishaan (16 May 2012). "How Many Innocent Civilians Did NATO Kill in Libya?". Time Magazine. Retrieved 9 April 2016.

- ^ Croft, Adrian. "NATO to advise Libya on strengthening security forces". Reuters.

- ^ Collins 2011, pp. 122–123.

- ^ "The area of responsibility". NATO Declassified. NATO. 23 February 2013. Retrieved 28 September 2013.

- ^ "Washington Treaty". NATO. 11 April 2011. Retrieved 28 September 2013.

- ^ Adrian Croft (19 September 2013). "Some EU states may no longer afford air forces-general". Reuters. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ^ Craig Whitlock (29 January 2012). "NATO allies grapple with shrinking defense budgets". Washington Post. Retrieved 29 March 2013.

- ^ "Alliance invites Montenegro to start accession talks to become member of NATO". NATO. NATO. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ^ Joy, Oliver (16 January 2014). "Macedonian PM: Greece is avoiding talks over name dispute". CNN. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- ^ Ramadanovic, Jusuf; Nedjeljko Rudovic (12 September 2008). "Montenegro, BiH join Adriatic Charter". Southeast European Times. Retrieved 24 March 2009.

- ^ George J, Teigen JM (2008). "NATO Enlargement and Institution Building: Military Personnel Policy Challenges in the Post-Soviet Context". European Security. 17 (2): 346. doi:10.1080/09662830802642512.

- ^ Cathcourt, Will (27 March 2014). "Obama Tells Georgia to Forget About NATO After Encouraging It to Join". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ^ "Medvedev warns on Nato expansion". BBC News. 25 March 2008. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ^ Art 1998, pp. 383–4: "The United States and its NATO allies have gotten themselves into a real pickle ... [w]ith their decision to enlarge NATO by taking in Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic ... How large can a NATO-without-Russia become before the West more or less permanently alienates Russia? ... Taking in Ukraine without also inducting Russia is the quickest way to alienate Russia ... and would justifiably give rise within Russia to fears of encirclement by, and exclusion from, the West."

- ^ Polityuk, Pavel (18 March 2014). "PM tells Ukrainians: No NATO membership, armed groups to disarm". Reuters. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ^ "Ukrainian President Signs Law Allowing NATO Membership Bid". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 29 December 2014. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ^ "NATO Topics: Individual Partnership Action Plans". Nato.int. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ^ "Cooperative Archer military exercise begins in Georgia". RIA Novosti. 9 July 2007. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- ^ a b "Partnership for Peace". Nato.int. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ "Nato and Belarus – partnership, past tensions and future possibilities". Foreign Policy and Security Research Center. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- ^ "NATO Topics: The Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council". Nato.int. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ "Declaration by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan". Nato.int. Archived from the original on 8 September 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ Bram Boxhoorn, Broad Support for NATO in the Netherlands, 21 September 2005, Archived 2007-02-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "NATO Partner countries". Nato.int. 6 March 2009. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- ^ NATO, Relations with Contact Countries. Retrieved January 29, 2013.

- ^ "NATO PARTNERSHIPS: DOD Needs to Assess U.S. Assistance in Response to Changes to the Partnership for Peace Program" (PDF). United States Government Accountability Office. September 2010. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ^ "Partners". NATO. 2 April 2012. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ^ "NATO and Colombia open channel for future cooperation". Nato.int. 25 June 2013. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ^ "NATO homepage". Retrieved 12 March 2006.

- ^ Mayo, Virginia (13 November 2014). "NATO shows off its new HQ-to-be". Associated Press. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- ^ Collins 2011, p. 26.

- ^ "NATO Headquarters". Nato.int. 10 August 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ "National delegations to NATO What is their role?". NATO. 18 June 2007. Archived from the original on 14 July 2007. Retrieved 15 July 2007.

- ^ "Battle for Ukraine: How a diplomatic success unravelled". The Financial Times. 3 February 2015. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ^ "NATO Who's who? – Secretaries General of NATO". Nato.int. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ "NATO Who's who? – Deputy Secretaries General of NATO". NATO. Retrieved 20 July 2012.

- ^ Press Statement: German MP Karl A. Lamers elected President of NATO PA. NATO Parliamentary Assembly, 16 November 2010

- ^ "General Stéphane Abrial, French Air Force, assumed duties as Supreme Allied Commander Transformation in summer 2009". Act.nato.int. 29 July 2009. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- ^ "Topic: The Military Committee". NATO. 5 March 2012. Retrieved 5 September 2013.

- ^ "France to rejoin NATO command". CNN. 17 June 2008. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ^ Fuller, Thomas (18 February 2003). "Reaching accord, EU warns Saddam of his 'last chance'". International Herald Tribune. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 15 July 2007.

- ^ "1949-1952: Creating a Command Structure for NATO". NATO. 2013. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ^ Espen Barth, Eide; Frédéric Bozo (Spring 2005). "Should NATO play a more political role?". Nato Review. NATO. Retrieved 15 July 2007.

- ^ "The Rapid Deployable Corps". NATO. 26 November 2012. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ^ BBC, NATO Readjusts as UKraine Crisis Looms, 5 February 2015.

Bibliography

- Art, Robert J. (1998). "Creating a Disaster: NATO's Open Door Policy". Political Science Quarterly. 113 (3): 383–403. JSTOR 2658073.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Auerswald, David P., and Stephen M. Saideman, eds. NATO in Afghanistan: Fighting Together, Fighting Alone (Princeton U.P., 2014)

- Bethlehem, Daniel L.; Weller, Marc (1997). The 'Yugoslav' Crisis in International Law. Cambridge International Documents Series. Vol. 5. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-46304-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Clausson, M. I. (2006). NATO: Status, Relations, and Decision-Making. Nova Publishers. ISBN 1-60021-098-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Collins, Brian J. (2011). NATO: A Guide to the Issues. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 0-3133-5491-X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Garthoff, Raymond L. (1994). Détente and confrontation: American-Soviet relations from Nixon to Reagan. Brookings Institution Press. ISBN 0-8157-3041-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gorbachev, Mikhail (1996). Memoirs. London: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-40668-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Harsch, Michael F. (2015). The Power of Dependence: NATO-UN Cooperation in Crisis Management. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-1910-3396-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Isby, David C.; Kamps Jr., Charles (1985). Armies of NATO's Central Front. Jane's Information Group. ISBN 0-7106-0341-X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kaplan, Lawrence S. (2013). NATO before the Korean War: April 1949-June 1950. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press.

- Kaplan, Lawrence S. (2004). NATO Divided, NATO United: The Evolution of an Alliance. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-2759-8006-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - National Defense University (1997). Allied command structures in the new NATO. DIANE Publishing. ISBN 1-57906-033-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Njølstad, Olav (2004). The last decade of the Cold War: from conflict escalation to conflict transformation. Vol. 5. Psychology Press. ISBN 0-7146-8539-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Osgood, Robert E. (1962). NATO: The Entangling Alliance. University of Chicago Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Park, William (1986). Defending the West: a history of NATO. Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-0408-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Reynolds, David (1994). The Origins of the Cold War in Europe: International Perspectives. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10562-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Schoenbaum, Thomas J. (1988). Waging Peace and War: Dean Rusk in the Truman, Kennedy, and Johnson Years. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-60351-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - van der Eyden, Ton (2003). Public management of society: rediscovering French institutional engineering in the European context. Vol. 1. IOS Press. ISBN 1-58603-291-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wenger, Andreas; Nuenlist, Christian; Locher, Anna (2007). Transforming NATO in the Cold War: Challenges beyond deterrence in the 1960s. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-415-39737-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Willbanks, James H. (2004). Machine Guns: An Illustrated History of Their Impact. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-8510-9480-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Zenko, Micah (2010). Between Threats and War: U.S. Discrete Military Operations in the Post-Cold War World. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-7191-X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Asmus, Ronald. A Little War that Shook the World : Georgia, Russia, and the Future of the West. NYU (2010). ISBN 978-0-230-61773-5

External links

- Official

- Collected news

- NATO collected news and commentary at Al Jazeera English

- NATO collected news and commentary at Dawn

- NATO collected news and commentary at The Guardian

- NATO collected news and commentary at The New York Times

- Template:WSJ topic

- Historic films

- The short film Big Picture: Why NATO? is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- The short film Big Picture: NATO Maneuvers is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- Use dmy dates from July 2012

- 1949 in military history

- 20th-century military alliances

- 21st-century military alliances

- Anti-communist organizations

- Cold War organizations

- Cold War treaties

- Foreign relations of the Soviet Union

- International military organizations

- Military alliances involving Belgium

- Military alliances involving Bulgaria

- Military alliances involving Canada

- Military alliances involving Estonia

- Military alliances involving France

- Military alliances involving Greece

- Military alliances involving Hungary

- Military alliances involving Italy

- Military alliances involving Latvia

- Military alliances involving Lithuania

- Military alliances involving Luxembourg

- Military alliances involving Poland

- Military alliances involving Portugal

- Military alliances involving Romania

- Military alliances involving Spain

- Military alliances involving Turkey

- Military alliances involving the Netherlands

- Military alliances involving the United Kingdom

- Military alliances involving the United States

- NATO

- Organisations based in Brussels

- Organizations established in 1949

- Supraorganizations

- 1949 establishments in Washington, D.C.