Social issues in India

Since India's Independence in 1947, the South Asian nation has faced multiple social and economic issues.

Overpopulation

The population of India is an estimated 1.27 billion.[1][2][3] Though India ranks second in population, it ranks 33 in population density. Indira Gandhi,then Prime Minister of India, had implemented a forced sterilisation programme in the early 1970s but the programme failed.[citation needed] Officially, men with two children or more were required to be sterilised, but many unmarried young men, political opponents and ignorant, poor men were also believed to have been affected by this programme. This programme is still remembered and regretted in India, and is blamed for creating a public aversion to family planning, which hampered Government programmes for decades.[4] One of the reasons the population has increased is that a dip in the rate of infant mortality has not been accompanied by a corresponding fall in the birth rate.[citation needed]

Economic issues

Poverty

India suffers from substantial poverty. In 2012, the Indian government stated 21.9% of its population is below its official poverty limit.[6] The World Bank, in 2011 based on 2005's PPPs International Comparison Program,[7] estimated 23.6% of Indian population, or about 276 million people, lived below $1.25 per day on purchasing power parity.[8][9] According to United Nation's Millennium Development Goal (MDG) programme 270 millions or 21.9% people out of 1.2 billion of Indians lived below poverty line of $1.25 in 2011-2012 as compare to 41.6% in 2004-05.[10]

Official figures estimate that 27.5%[11] of Indians lived below the national poverty line in 2004–2005.[12] A 2007 report by the state-run National Commission for Enterprises in the Unorganized Sector (NCEUS) found that 25% of Indians, or 236 million people, lived on less than 20 rupees per day[13] with most working in "informal labour sector with no job or social security, living in abject poverty."[14] Indira Gandhi, Prime Minister of India in 1971 election campaign gave the slogan garibi hatao desh bachavo but it helped little to the cause of poverty eradication in India. It was part of the 5th Five-Year Plan.

Sanitation

Lack of proper sanitation is a major concern for the people of India. Statistics conducted by UNICEF have shown that only 90% of India’s population is able to utilise proper sanitation facilities as of 2008.[15] It is estimated that one in every ten deaths in India is linked to poor sanitation and hygiene. Diarrhea is the single largest killer and accounts for one in every twenty deaths.[15] Around 450,000 deaths were linked to diarrhea alone in 2006, of which 88% were deaths of children below five.[15] Studies by UNICEF have also shown that diseases resulting from poor sanitation affects children in their cognitive development.[16]

People without access to proper sanitation facilities more-often-than-not defecate in public or in rivers. One gram of faeces could potentially contain 10 million viruses, one million bacteria, 1000 parasite cysts and 100 worm eggs.[17] The Ganga river in India has a stunning 1.1 million litres of raw sewage being disposed into it every minute.[17] The high level of contamination of the river by human waste allow diseases like cholera to spread easily, resulting in many deaths, especially among children who are more susceptible to such viruses.[18]

A lack of adequate sanitation also leads to significant economic losses for the country. A Water and sanitation Program (WSP) study The Economic Impacts of Inadequate Sanitation in India (2010) showed that inadequate sanitation caused India considerable economic losses, equivalent to 6.4 per cent of India’s GDP in 2006 at US$53.8 billion (Rs.2.4 trillion) In addition, the poorest 20% of households living in urban areas bore the highest per capita economic impacts of inadequate sanitation.[19]

Recognising the importance of proper sanitation, the Government of India started the Central Rural Sanitation Program (CRSP) in 1986, in hope of improving the basic sanitation amenities of rural areas. This program was later reviewed and, in 1999, the Total Sanitation Campaign (TSC) was launched. Programmes such as Individual Household Latrines (IHHL), School Sanitation and Hygiene Education (SSHE), Community Sanitary Complex, Anganwadi toilets were implemented under the TSC.[20]

Through the TSC, the Indian Government hopes to stimulate the demand for sanitation facilities in its less-urbanised areas, rather than to continually provide these amenities to these area's residents. This is a two-pronged strategy, where the people involved in this programme take ownership and better maintain their sanitation facilities, and at the same time, reduces the liabilities and costs on the Indian Government. This would allow the government to reallocate their resources to other aspects of development.[23] Thus, the government set the objective of granting access to toilets to all by 2017.[24]

To meet this objective, incentives are given out to encourage participation from the rural population to construct their own sanitation amenities. In addition, the government has set out to educate its people on the importance and benefits of proper sanitation through mass communication and interpersonal communication techniques. This is done through mass and print media to reach out to a larger audience and through group discussions and games to better engage and interact with the individual.[25]

Corruption

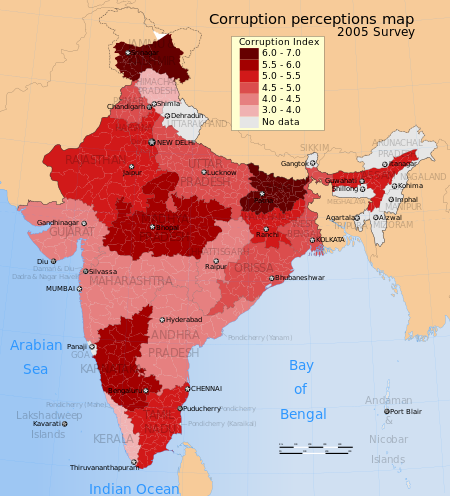

Corruption is widespread in India. India is ranked 76 out of a 179 countries in Transparency International's Corruption Perceptions Index, but its score has improved consistently from 2.7 in 2002 to 3.1 in 2011.[26]

In India, corruption takes the form of bribes, tax evasion, exchange controls, embezzlement, etc. A 2005 study done by Transparency International[unreliable source?] (TI) India found that more than 50%[dubious – discuss] had firsthand[dubious – discuss] experience of paying bribe or peddling influence to get a job done in a public office.[27] The chief economic consequences of corruption are the loss to the exchequer, an unhealthy climate for investment and an increase in the cost of government-subsidised services.

The TI India study estimates the monetary value of petty corruption in 11 basic services provided by the government, like education, healthcare, judiciary, police, etc., to be around Rs.21,068 crores.[27] India still ranks in the bottom quartile of developing nations in terms of the ease of doing business, and compared to China and other lower developed Asian nations, the average time taken to secure the clearances for a startup or to invoke bankruptcy is much greater.[28] Recently a revelation of tax evasion (Panama Papers' Leak) case involving some high-profile celebrities and businessmen has added spark to the fumes of corruption charges against the elite of the country.

Debt bondage

Debt bondage in India was legally abolished in 1976 but it remains prevalent, with weak enforcement of the law by governments.[29] Bonded labour involves the exploitive interlinking of credit and labour agreements that devolve into slave-like exploitation due to severe power imbalances between the lender and the borrower.[29]

The rise of Dalit activism, government legislation starting as early as 1949,[30] as well as ongoing work by NGOs and government offices to enforce labour laws and rehabilitate those in debt, appears to have contributed to the reduction of bonded labour in India. However, according to research papers presented by the International Labour Organization, there are still many obstacles to the eradication of bonded labour in India.[31][32]

Debt bondage in India is most prevalent in agricultural areas. Farmers taking small loans can find themselves paying interest on the loans that exceeds 100% of the loan per year.[29]

Education

Poor education

Since the Indian Constitution was completed in 1949, education has remained one of the priorities of the Indian government. The first education minister Maulana Azad founded a system of education which aimed to provide free education at the primary level. Primary education was made free and compulsory for children from 6-14, and child labour was banned. The government introduced incentives to education and disincentives for not receiving education – for instance, the provision of mid-day meals in schools were introduced.

Many similar initiatives echoed, and the largest of such initiatives is Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, which actively promoted “Education for All”. In line with this, the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) aimed to increase their expenditure on education to 6% of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) from values fluctuating about 3% through their National Common Minimum Programme (NCMP) in 2004. The Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act was also imposed in 2009. Despite these initiatives, education continues to persist as an impediment to development.

Issues

While many schools were built, they had poor infrastructure and inadequate facilities. Schools in the rural areas were especially affected. According to District Information System for Education (DISE) in India in 2009, only about 51.5% of all schools in India have boundary walls, 16.65% have computers and 39% have electricity. Of which, only 6.47% of primary schools and 33.4% of upper primary schools have computers, and only 27.7% of primary schools have electricity.[34] Learning in poorly furnished schools was not conducive, resulting in poor quality education.

Furthermore, the absence rates of teachers and students were high, while their retainment rates low. The incentives for going to school were not apparent, while punishment for absence was not enforced. Despite the government’s decree on compulsory education and the child labour ban, many children were still missing classes to go to work. The government did not interfere even when children missed school.

Also, online country studies publications by the Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress stated that “it was not unusual for the teacher to be absent or even to subcontract the teaching work to unqualified substitutes”.[35] This exacerbates the problems of the lack of qualified teachers. Currently, the student-teacher ratio remains high at around 32, which is not much of an improvement since 2006 when the ratio was 34.[36]

Economic and social disparities also plague the fundamentals of the education system. Rural children are less able to receive education because of greater opportunity costs, since rural children have to work to contribute to the family’s income. According to the Annual Status of Education in 2009, the average attendance rate of students in the rural states is about 75%. Though this rate varies significantly, states like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar had more than 40% absentees during a random visit to their schools. In the urban states, more than 90% of the students were present in their schools during a visit.

Opportunity for youth

India, one of the youngest countries in the world, where youth accounted for 20% of the total population in 2011, according to the Registrar General of India. However, youth unemployment remains high in India.

[37] India has an unrivaled youth demographic: 65% of its population is 35 or under, and half (50%) of the country's population of 1.25 billion people is under 25 years of age.[38]

Superstition

Superstition is considered a widespread social problem in India. Superstition refers to any belief or practice which is explained by supernatural causality, and is in contradiction to modern science.[39] Some beliefs and practices, which are considered superstitious by some, may not be considered so by others. The gap, between what is superstitious and what is not, widens even more when considering the opinions of the general public and scientists.[40] Prevalent superstition in India had earned it the title of "The Land of Snake Charmers and Black Magic". Till only 25-30 years back, if not more, there were many people in the world who thought that India was a country of snake charmers, it was a country which practiced in black magic.[41]

Violence

Religious violence

Constitutionally India is a secular state, [42] but large-scale violence have periodically occurred in India since independence. In recent decades, communal tensions and religion-based politics have become more prominent.

In Jammu and Kashmir, Since March 1990, estimates of between 250,000 and 300,000 pandits have migrated outside Kashmir due to persecution by Islamic fundamentalists in the largest case of ethnic cleansing since the partition of India.[43] The proportion of Kashmiri Pandits in the Kashmir valley has declined from about 15% in 1947 to, by some estimates, less than 0.1% since the insurgency in Kashmir took on a religious and sectarian flavor.[44] Many Kashmiri Pandits have been killed by Islamist terrorists in incidents such as the Wandhama massacre and the 2000 Amarnath pilgrimage massacre.[45][46][47][48][49]

In 1990s, violent attacks on Christians in India were reported.[50] The acts of violence include arson of churches, forced conversion of Christians to Hinduism, distribution of threatening literature, raping of nuns, murder of Christian priests and destruction of Christian schools, colleges, and cemeteries.[51][52] The Sangh Parivar and related organisations have stated that the violence is an expression of "spontaneous anger" of "vanvasis" against "forcible conversion" activities undertaken by missionaries,[51][53][54] a claim described as "absurd" and rejected by scholars.[51]

Between 1964 and 1996, thirty-eight incidents of violence against Christians were reported.[51] In 1997, twenty-four such incidents were reported.[55] In 2007 and 2008 there was a further flare up of tensions in Odisha, the first following the Christians' putting up a Pandhal in land traditionally used by Hindus and the second after the unprovoked murder of a Hindu Guru and four of his disciples while observing Janmashtami puja. This was followed by an attack on a 150-year-old church in Madhya Pradesh,[56] and more attacks in Karnataka,[57]

Terrorism

The regions with long term terrorist activities today are Jammu and Kashmir, Central India (Naxalism) and Seven Sister States (independence and autonomy movements). In the past, the Punjab insurgency led to militant activities in the Indian state of Punjab as well as the national capital Delhi (Delhi serial blasts, anti-Sikh riots). As of 2006, at least 232 of the country’s 608 districts were afflicted, at differing intensities, by various insurgent and terrorist movements.[58]

Terrorism in India has often been alleged to be sponsored by Pakistan. After most acts of terrorism in India, many journalists and politicians accuse Pakistan's intelligence agency, the Inter-Services Intelligence of playing a role.[59]

Naxalite Maoist insurgency

Naxalism is an informal name given to communist groups that were born out of the Sino-Soviet split in the Indian communist movement. Ideologically they belong to various trends of Maoism. Initially the movement had its centre in West Bengal. In recent years, they have spread into less developed areas of rural central and eastern India, such as Chhattisgarh and Andhra Pradesh through the activities of underground groups like the Communist Party of India (Maoist).[60] The CPI (Maoist) and some other Naxal factions are considered terrorists by the Government of India and various state governments in India.[61]

Caste related violence

Over the years, various incidents of violence against Dalits, such as Kherlanji Massacre have been reported from many parts of India. At the same time, many violent protests by Dalits, such as the 2006 Dalit protests in Maharashtra, have been reported as well.

The Mandal Commission was established in 1979 to "identify the socially or educationally backward",[64] and to consider the question of seat reservations and quotas for people to redress caste discrimination. In 1980, the commission's report affirmed the affirmative action practice under Indian law whereby members of lower castes were given exclusive access to a certain portion of government jobs and slots in public universities. When V. P. Singh Government tried to implement the recommendations of Mandal Commission in 1989, massive protests were held in the country. Many alleged that the politicians were trying to cash in on caste-based reservations for purely pragmatic electoral purposes.

In 1990s, many parties Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), the Samajwadi Party and the Janata Dal started claiming that they are representing the backward castes. Many such parties, relying primarily on Backward Classes' support, often in alliance with Dalits and Muslims, rose to power in Indian states.[65] At the same time, many Dalit leaders and intellectuals started realising that the main Dalit oppressors were so-called Other Backward Classes,[66] and formed their own parties, such as the Indian Justice Party. The Congress (I) in Maharashtra long relied on OBCs' backing for its political success.[65]

Bharatiya Janata Party has also showcased its Dalit and OBC leaders to prove that it is not an upper-caste party. Bangaru Laxman, the former BJP president (2001–2002) was a Dalit. Sanyasin Uma Bharati, former CM of Madhya Pradesh, who belongs to OBC caste, was a former BJP leader. In 2006 Arjun Singh cabinet minister for MHRD of the UPA government was accused of playing caste politics when he introduced reservations for OBCs in educational institutions all around.

See also

- Dowry death

- Health in India

- Suicide in India

- Domestic violence in India

- Sexism in India

- Rape in India

- Environmental issues in India

- Women in India

- Gender pay gap in India

- brain drain

References

- ^ "Overpopulation in India" (PDF). Serendip.brynmawr.edu. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ "Overpopulation in India and China". Web.archive.org. 27 October 2009. Archived from the original on 27 October 2009. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ "Over-population warning as India's billionth baby is born". The Guardian. London. 11 May 2000. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ "Manas: History and Politics, Indira Gandhi". Sscnet.ucla.edu. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ Shawn Donnan (May 9, 2014), World Bank eyes biggest global poverty line increase in decades, The Financial Times

- ^ "Number and Percentage of Population Below Poverty Line". Reserve Bank of India. 2012. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- ^ World Bank’s $1.25/day poverty measure- countering the latest criticisms The World Bank (2010)

- ^ Note: 24.6% rate is based on 2005 PPP at $1.25 per day, International dollar basis, The World Bank (2015). A measured approach to ending poverty and boosting shared prosperity (PDF). World Bank Group. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-4648-0361-1.

- ^ Chandy and Kharas, What Do New Price Data Mean for the Goal of Ending Extreme Poverty? Brookings Institution, Washington D.C. (May 2014)

- ^ "8% GDP growth helped reduce poverty: UN report". The Hindu: Mobile Edition. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ^ This figure is extremely sensitive to the surveying methodology used. The Uniform Recall Period (URP) gives 27.5%. The Mixed Recall Period (MRP) gives a figure of 21.8%

- ^ Planning commission of India. Poverty estimates for 2004–2005

- ^ This figure has been variously reported as either "2 dollars per day" or "0.5 dollars per day". The former figure comes from the PPP conversion rate, whereas the latter comes from the market exchange rate. Also note that this figure does not contradict the NSS derived figure, which uses calorie consumption as the basis for its poverty line. It just uses a more inclusive poverty line

- ^ Nearly 80 Percent of India Lives On Half Dollar A Day, Reuters, 10 August 2007, retrieved 15 August 2007

- ^ a b c "India: Health Statistics". UNICEF Statistics. Retrieved 13 September 2011.

- ^ "10 Facts on Sanitation: 2". World Health Organization Fact Fille. Retrieved 12 September 2011.

- ^ a b "10 Facts on Sanitation: 3". World Health Organization Fact File. Retrieved 12 September 2011.

- ^ "Enhanced Quality of Life through Sustained Sanitation" (PDF). India Country Paper. Government of India. p. 14. Retrieved 12 September 2011.

- ^ "The Economic Impacts of Inadequate Sanitation in India" (PDF). Water and Sanitation Program Publications. p. 6. Retrieved 12 September 2011.

- ^ "Total Sanitation Campaign (TSC)". Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation Programmes. Retrieved 12 September 2011.

- ^ Nicholas Charron (2010), The Correlates of Corruption in India: Analysis and Evidence from the States, Asian Journal of Political Science, Volume 18, Issue 2, pp. 177-194

- ^ Debroy and Bhandari (2011). "Corruption in India". The World Finance Review.

- ^ "Sanitation: A Long Way to Go" (PDF). WaterAid: Inputs at SACOSAN. WaterAid. Retrieved 12 September 2011.

- ^ "Guidelines: Total Sanitation Campaign" (PDF). Central Rural Sanitation Programme. p. 5. Retrieved 12 September 2011.

- ^ "Techniques of IEC". Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation: TSC — Information. Education & Communication (IEC). Retrieved 12 September 2011.

- ^ Believe it or not! India is becoming less corrupt. CNN-IBN. 26 September 2007.

- ^ a b Centre for Media Studies (2005), India Corruption Study 2005: To Improve Governance Volume – I: Key Highlights, Transparency International India.

- ^ Economic Survey 2004–2005

- ^ a b c "A $110 loan, then 20 years of debt bondage". CNN. 2 June 2011.

- ^ Hart, Christine Untouchability Today: The Rise of Dalit Activism, Human Rights and Human Welfare, Topical Research Digest 2011, Minority Rights

- ^ "International Dalit Solidarity Network: Key Issues: Bonded Labour".

- ^ Ravi S. Srivastava Bonded Labor in India: Its Incidence and Pattern InFocus Programme on Promoting the Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work; and International Labour Office,(2005). Forced Labor. Paper 18

- ^ Ranking of states and union territories by lireacy rate: 2011 Census of India Report (2013)

- ^ Statistics from the District Information System for Education (DISE)

- ^ "India - Education". Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ^ Statistics from the District Information System for Education (DISE)

- ^ +Arun Prabhudesai. "Indian Education Report 2009". Trak.in - Indian Business of Technology, Mobile & Startups. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ^ +Priya Virmani. "India elections 2014 - Opinion". The Guardian - © 2016 Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ^ Dale B. Martin (30 June 2009). Inventing Superstition: From the Hippocratics to the Christians. Harvard University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-674-04069-4. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- ^ Stuart A. Vyse (2000). Believing in Magic: The Psychology of Superstition. Oxford University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-19-513634-0. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- ^ Narendra Modi. "Independence Day Speech - 15 August 2014". India, News - India Today. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ^ "Constitution of India as of 29 July 2008" (PDF). The Constitution Of India. Ministry of Law & Justice. Retrieved 13 April 2011.

- ^ Kashmiri Pandits in Nandimarg decide to leave Valley, Outlook, 30 March 2003, retrieved 30 November 2007

- ^ Kashmir: The scarred and the beautiful. New York Review of Books, 1 May 2008, p. 14.

- ^ 'I heard the cries of my mother and sisters', Rediff, 27 January 1998, retrieved 30 November 2007

- ^ Migrant Pandits voted for end of terror in valley, The Tribune, 27 April 2004, retrieved 30 November 2007

- ^ At least 58 dead in 2 attacks in Kashmir, CNN, 2 August 2000, archived from the original on 6 December 2006, retrieved 30 November 2007

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ City shocked at killing of Kashmiri Pandits, The Times of India, 25 March 2003, retrieved 30 November 2007

- ^ Phil Reeves (25 March 2003), Islamic militants kill 24 Hindus in Kashmir massacre, The Independent, retrieved 30 November 2007

- ^ Anti-Christian Violence on the Rise in India

- ^ a b c d Anti-Christian Violence in India

- ^ "Anti-Christian Violence on the Rise in India". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ^ Low, Alaine M.; Brown, Judith M.; Frykenberg, Robert Eric (eds.) (2002), Christians, Cultural Interactions, and India's Religious Traditions, Grand Rapids, Mich: W.B. Eerdmans, p. 134, ISBN 0-7007-1601-7

{{citation}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Subba, Tanka Bahadur; Som, Sujit; Baral, K. C (eds.) (2005), Between Ethnography and Fiction: Verrier Elwin and the Tribal Question in India, New Delhi: Orient Longman, ISBN 81-250-2812-9

{{citation}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ram Puniyani (2003), Communal Politics: Facts Versus Myths, SAGE, p. 167, ISBN 0-7619-9667-2

- ^ "150-yr-old church set afire in Madhya Pradesh". The Times Of India. 20 September 2008.

- ^ "Protest in Delhi over violence against Christians — Thaindian News". Thaindian.com. 26 September 2008. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ "India Assessment 2014". Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ^ "'Pak the problem, not the solution'". Hindustan Times. 16 September 2008. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ Ramakrishnan, Venkitesh (21 September 2005), The Naxalite Challenge, Frontline Magazine (The Hindu), retrieved 15 March 2007

- ^ Diwanji, A. K. (2 October 2003), Primer: Who are the Naxalites?, Rediff.com, retrieved 15 March 2007

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Incidence of Total Cognizable Crime (IPC) 1953-2011, Compendium of Crime in India, National Crime Research Bureau (NCRB), Union Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India (2012)

- ^ CRIMINAL VICTIMIZATION, 2012 Bureau of Justice Statistics, Department of Justice (USA), page 6, October 2013.

- ^ Bhattacharya, Amit. Who are the OBCs?, archived from the original on 27 June 2006, retrieved 19 April 2006 Times of India, 8 April 2006.

- ^ a b Caste-Based Parties, Country Studies US, retrieved 12 December 2006

- ^ Danny Yee, Book review of Caste, Society and Politics in India: From the Eighteenth Century to the Modern Age, retrieved 11 December 2006