Naringenin: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Added section on structure and subsection on chirality. |

||

| Line 49: | Line 49: | ||

'''Naringenin''' is a [[flavanone]], a type of [[flavonoid]]. It is the predominant flavanone in [[grapefruit]].<ref name="pmid11093936">{{cite journal |vauthors=Felgines C, Texier O, Morand C, Manach C, Scalbert A, Régerat F, Rémésy C | title = Bioavailability of the flavanone naringenin and its glycosides in rats | journal = Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. | volume = 279 | issue = 6 | pages = G1148–54 |date=December 2000 | pmid = 11093936 | doi = }}</ref> |

'''Naringenin''' is a [[flavanone]], a type of [[flavonoid]]. It is the predominant flavanone in [[grapefruit]].<ref name="pmid11093936">{{cite journal |vauthors=Felgines C, Texier O, Morand C, Manach C, Scalbert A, Régerat F, Rémésy C | title = Bioavailability of the flavanone naringenin and its glycosides in rats | journal = Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. | volume = 279 | issue = 6 | pages = G1148–54 |date=December 2000 | pmid = 11093936 | doi = }}</ref> |

||

== Structure == |

|||

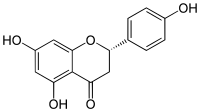

Naringenin has the skeleton structure of a flavanone with three [[Hydroxy group|hydroxy groups]] at the 4', 5, and 7 carbons. It may be found both in the [[Aglycone|aglycol]] form, as naringenin, or in its [[Glycoside|glycosidic]] form, [[naringin]], which has the addition of the [[disaccharide]] [[neohesperidose]] attached via a [[Glycosidic bond|glycosidic]] linkage at carbon 7. |

|||

=== Chirality === |

|||

Like the majority of flavanones, naringenin has a single chiral center at carbon 2, resulting in [[Enantiomer|enantiomeric]] forms of the compound.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Yáñez|first=Jaime A.|last2=Andrews|first2=Preston K.|last3=Davies|first3=Neal M.|date=2007-04-01|title=Methods of analysis and separation of chiral flavonoids|url=http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1570023206008671|journal=Journal of Chromatography B|volume=848|issue=2|pages=159–181|doi=10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.10.052}}</ref> The enantiomers are found in varying ratios in natural sources.<ref name=":0" /> [[Racemization]] of S(-)-naringenin has been shown to occur fairly quickly.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Krause|first=M.|last2=Galensa|first2=R.|date=1991-07-01|title=Analysis of enantiomeric flavanones in plant extracts by high-performance liquid chromatography on a cellulose triacetate based chiral stationary phase|url=https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF02262470|journal=Chromatographia|language=en|volume=32|issue=1-2|pages=69–72|doi=10.1007/BF02262470|issn=0009-5893}}</ref> |

|||

Separation and analysis of the enantiomers has been explored for over 20 years,<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Yáñez|first=Jaime A.|last2=Andrews|first2=Preston K.|last3=Davies|first3=Neal M.|date=2007-04-01|title=Methods of analysis and separation of chiral flavonoids|url=http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1570023206008671|journal=Journal of Chromatography B|volume=848|issue=2|pages=159–181|doi=10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.10.052}}</ref> primarily via [[high-performance liquid chromatography]] on polysaccharide-derived chiral stationary phases. <ref>{{Cite journal|last=Krause|first=M.|last2=Galensa|first2=R.|date=1991-07-01|title=Analysis of enantiomeric flavanones in plant extracts by high-performance liquid chromatography on a cellulose triacetate based chiral stationary phase|url=https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF02262470|journal=Chromatographia|language=en|volume=32|issue=1-2|pages=69–72|doi=10.1007/BF02262470|issn=0009-5893}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Krause|first=Martin|last2=Galensa|first2=Rudolf|title=High-performance liquid chromatography of diastereomeric flavanone glycosides in Citrus on a β-cyclodextrin-bonded stationary phase (Cyclobond I)|url=https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9673(91)85005-Z|journal=Journal of Chromatography A|language=en|volume=588|issue=1-2|pages=41–45|doi=10.1016/0021-9673(91)85005-z}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Gaggeri|first=Raffaella|last2=Rossi|first2=Daniela|last3=Collina|first3=Simona|last4=Mannucci|first4=Barbara|last5=Baierl|first5=Marcel|last6=Juza|first6=Markus|date=2011-08-12|title=Quick development of an analytical enantioselective high performance liquid chromatography separation and preparative scale-up for the flavonoid Naringenin|url=http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0021967311002536|journal=Journal of Chromatography A|volume=1218|issue=32|pages=5414–5422|doi=10.1016/j.chroma.2011.02.038}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Wan|first=Lili|last2=Sun|first2=Xipeng|last3=Li|first3=Yan|last4=Yu|first4=Qi|last5=Guo|first5=Cheng|last6=Wang|first6=Xiangwei|date=2011-04-01|title=A Stereospecific HPLC Method and Its Application in Determination of Pharmacokinetics Profile of Two Enantiomers of Naringenin in Rats|url=https://academic.oup.com/chromsci/article/49/4/316/336608/A-Stereospecific-HPLC-Method-and-Its-Application|journal=Journal of Chromatographic Science|volume=49|issue=4|pages=316–320|doi=10.1093/chrsci/49.4.316|issn=0021-9665}}</ref> There is evidence to suggest [[Stereospecificity|stereospecific]] [[pharmacokinetics]] and [[pharmacodynamics]] profiles, which has been proposed to be an explanation for the wide variety in naringenin's reported bioactivity. <ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last=Yáñez|first=Jaime A.|last2=Remsberg|first2=Connie M.|last3=Miranda|first3=Nicole D.|last4=Vega-Villa|first4=Karina R.|last5=Andrews|first5=Preston K.|last6=Davies|first6=Neal M.|date=2008-01-01|title=Pharmacokinetics of selected chiral flavonoids: hesperetin, naringenin and eriodictyol in rats and their content in fruit juices|url=http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/bdd.588/abstract|journal=Biopharmaceutics & Drug Disposition|language=en|volume=29|issue=2|pages=63–82|doi=10.1002/bdd.588|issn=1099-081X}}</ref> |

|||

== Sources and bioavailability == |

== Sources and bioavailability == |

||

Revision as of 01:51, 9 May 2017

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

5,7-Dihydroxy-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)chroman-4-one

| |

| Other names

Naringetol; Salipurol; Salipurpol; 4',5,7-Trihydroxyflavanone

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.006.865 |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C15H12O5 | |

| Molar mass | 272.256 g·mol−1 |

| Melting point | 251 °C (484 °F; 524 K)[1] |

| 475 mg/L[1] | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Naringenin is a flavanone, a type of flavonoid. It is the predominant flavanone in grapefruit.[2]

Structure

Naringenin has the skeleton structure of a flavanone with three hydroxy groups at the 4', 5, and 7 carbons. It may be found both in the aglycol form, as naringenin, or in its glycosidic form, naringin, which has the addition of the disaccharide neohesperidose attached via a glycosidic linkage at carbon 7.

Chirality

Like the majority of flavanones, naringenin has a single chiral center at carbon 2, resulting in enantiomeric forms of the compound.[3] The enantiomers are found in varying ratios in natural sources.[4] Racemization of S(-)-naringenin has been shown to occur fairly quickly.[5]

Separation and analysis of the enantiomers has been explored for over 20 years,[6] primarily via high-performance liquid chromatography on polysaccharide-derived chiral stationary phases. [7][8][9][10] There is evidence to suggest stereospecific pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics profiles, which has been proposed to be an explanation for the wide variety in naringenin's reported bioactivity. [4]

Sources and bioavailability

Naringenin can be found in grapefruit, oranges, tomatoes (skin)[11] and in water mint.

This bioflavonoid is difficult to absorb on oral ingestion. In the best-case scenario, only 15% of ingested naringenin will get absorbed in the human gastrointestinal tract. [citation needed]

The naringenin-7-glucoside form seems less bioavailable than the aglycol form.[12]

Grapefruit juice can provide much higher plasma concentrations of naringenin than orange juice.[13] Also found in grapefruit is the related compound kaempferol, which has a hydroxyl group next to the ketone group.

Naringenin can be absorbed from cooked tomato paste.[14]

Potential biological effects

Naringenin has been shown to have an inhibitory effect on the human cytochrome P450 isoform CYP1A2, which can change pharmacokinetics in a human (or orthologous) host of several popular drugs in an adverse manner, even resulting in carcinogens of otherwise harmless substances.[15] The National Research Institute of Chinese Medicine in Taiwan conducted experiments on the effects of the grapefruit flavanones naringin and naringenin on CYP450 enzyme expression. Naringenin proved to be a potent inhibitor of the benzo(a)pyrene metabolizing enzyme benzo(a)pyrene hydroxylase (AHH) in experiments in mice.[16]

Naringenin has also been shown to reduce oxidative damage to DNA in vitro and in animal studies.[17]

Naringenin has also been shown to reduce hepatitis C virus production by infected hepatocytes (liver cells) in cell culture. This seems to be secondary to naringenin's ability to inhibit the secretion of very-low-density lipoprotein by the cells.[18] The antiviral effects of naringenin are currently under clinical investigation.[19]

Naringenin seems to protect LDLR-deficient mice from the obesity effects of a high-fat diet.[20]

Naringenin lowers the plasma and hepatic cholesterol concentrations by suppressing HMG-CoA reductase and ACAT in rats fed a high-cholesterol diet.[21]

It also produces BDNF-dependent antidepressant-like effects in mice.[22]

In 2006 it was shown to increase the mRNA expression levels of two DNA repair enzymes, DNA pol beta and OGG1, specifically in prostate cancer cells.[23]

Like many other flavonoids, naringenin has been found to possess weak activity at the opioid receptors.[24] It specifically acts as a non-selective antagonist of all three opioid receptors, albeit with weak affinity.[24]

Metabolism

The enzyme naringenin 8-dimethylallyltransferase uses dimethylallyl diphosphate and (−)-(2S)-naringenin to produce diphosphate and 8-prenylnaringenin.

Biodegradation

Cunninghamella elegans, a fungal model organism of the mammalian metabolism, can be used to study the naringenin sulfation.[25]

References

- ^ a b "Naringenin". ChemIDplus.

- ^ Felgines C, Texier O, Morand C, Manach C, Scalbert A, Régerat F, Rémésy C (December 2000). "Bioavailability of the flavanone naringenin and its glycosides in rats". Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 279 (6): G1148–54. PMID 11093936.

- ^ Yáñez, Jaime A.; Andrews, Preston K.; Davies, Neal M. (2007-04-01). "Methods of analysis and separation of chiral flavonoids". Journal of Chromatography B. 848 (2): 159–181. doi:10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.10.052.

- ^ a b Yáñez, Jaime A.; Remsberg, Connie M.; Miranda, Nicole D.; Vega-Villa, Karina R.; Andrews, Preston K.; Davies, Neal M. (2008-01-01). "Pharmacokinetics of selected chiral flavonoids: hesperetin, naringenin and eriodictyol in rats and their content in fruit juices". Biopharmaceutics & Drug Disposition. 29 (2): 63–82. doi:10.1002/bdd.588. ISSN 1099-081X.

- ^ Krause, M.; Galensa, R. (1991-07-01). "Analysis of enantiomeric flavanones in plant extracts by high-performance liquid chromatography on a cellulose triacetate based chiral stationary phase". Chromatographia. 32 (1–2): 69–72. doi:10.1007/BF02262470. ISSN 0009-5893.

- ^ Yáñez, Jaime A.; Andrews, Preston K.; Davies, Neal M. (2007-04-01). "Methods of analysis and separation of chiral flavonoids". Journal of Chromatography B. 848 (2): 159–181. doi:10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.10.052.

- ^ Krause, M.; Galensa, R. (1991-07-01). "Analysis of enantiomeric flavanones in plant extracts by high-performance liquid chromatography on a cellulose triacetate based chiral stationary phase". Chromatographia. 32 (1–2): 69–72. doi:10.1007/BF02262470. ISSN 0009-5893.

- ^ Krause, Martin; Galensa, Rudolf. "High-performance liquid chromatography of diastereomeric flavanone glycosides in Citrus on a β-cyclodextrin-bonded stationary phase (Cyclobond I)". Journal of Chromatography A. 588 (1–2): 41–45. doi:10.1016/0021-9673(91)85005-z.

- ^ Gaggeri, Raffaella; Rossi, Daniela; Collina, Simona; Mannucci, Barbara; Baierl, Marcel; Juza, Markus (2011-08-12). "Quick development of an analytical enantioselective high performance liquid chromatography separation and preparative scale-up for the flavonoid Naringenin". Journal of Chromatography A. 1218 (32): 5414–5422. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2011.02.038.

- ^ Wan, Lili; Sun, Xipeng; Li, Yan; Yu, Qi; Guo, Cheng; Wang, Xiangwei (2011-04-01). "A Stereospecific HPLC Method and Its Application in Determination of Pharmacokinetics Profile of Two Enantiomers of Naringenin in Rats". Journal of Chromatographic Science. 49 (4): 316–320. doi:10.1093/chrsci/49.4.316. ISSN 0021-9665.

- ^ Vallverdú-Queralt, A; Odriozola-Serrano, I; Oms-Oliu, G; Lamuela-Raventós, RM; Elez-Martínez, P; Martín-Belloso, O (2012). "Changes in the polyphenol profile of tomato juices processed by pulsed electric fields". J Agric Food Chem. 60 (38): 9667–9672. doi:10.1021/jf302791k. PMID 22957841.

- ^ Choudhury R, Chowrimootoo G, Srai K, Debnam E, Rice-Evans CA (November 1999). "Interactions of the flavonoid naringenin in the gastrointestinal tract and the influence of glycosylation". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 265 (2): 410–5. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1999.1695. PMID 10558881.

- ^ Erlund I, Meririnne E, Alfthan G, Aro A (February 2001). "Plasma kinetics and urinary excretion of the flavanones naringenin and hesperetin in humans after ingestion of orange juice and grapefruit juice". J. Nutr. 131 (2): 235–41. PMID 11160539.

- ^ Bugianesi R, Catasta G, Spigno P, D'Uva A, Maiani G (November 2002). "Naringenin from cooked tomato paste is bioavailable in men". J. Nutr. 132 (11): 3349–52. PMID 12421849.

- ^ Fuhr U, Klittich K, Staib AH (April 1993). "Inhibitory effect of grapefruit juice and its bitter principal, naringenin, on CYP1A2 dependent metabolism of caffeine in man". Br J Clin Pharmacol. 35 (4): 431–6. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(96)00417-1. PMC 1381556. PMID 8485024.

- ^ Ueng YF, Chang YL, Oda Y, Park SS, Liao JF, Lin MF, Chen CF (1999). "In vitro and in vivo effects of naringin on cytochrome P450-dependent monooxygenase in mouse liver". Life Sci. 65 (24): 2591–602. doi:10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00528-7. PMID 10619367.

- ^ Sumit Kumar; Ashu Bhan Tiku (2016). "Biochemical and Molecular Mechanisms of Radioprotective Effects of Naringenin, a Phytochemical from Citrus Fruits". J. Agric. Food Chem. 64 (8): 1676–1685. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.5b05067.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Nahmias Y, Goldwasser J, Casali M, van Poll D, Wakita T, Chung RT, Yarmush ML (May 2008). "Apolipoprotein B-dependent hepatitis C virus secretion is inhibited by the grapefruit flavonoid naringenin". Hepatology. 47 (5): 1437–45. doi:10.1002/hep.22197. PMID 18393287.

- ^ A Pilot Study of the Grapefruit Flavonoid Naringenin for HCV Infection

- ^ Mulvihill EE, Allister EM, Sutherland BG, Telford DE, Sawyez CG, Edwards JY, Markle JM, Hegele RA, Huff MW (October 2009). "Naringenin prevents dyslipidemia, apolipoprotein B overproduction, and hyperinsulinemia in LDL receptor-null mice with diet-induced insulin resistance". Diabetes. 58 (10): 2198–210. doi:10.2337/db09-0634. PMC 2750228. PMID 19592617.

- ^ Lee SH, Park YB, Bae KH, Bok SH, Kwon YK, Lee ES, Choi MS (1999). "Cholesterol-lowering activity of naringenin via inhibition of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase and acyl coenzyme A:cholesterol acyltransferase in rats". Ann. Nutr. Metab. 43 (3): 173–80. doi:10.1159/000012783. PMID 10545673.

- ^ Yi LT, Liu BB, Li J, Luo L, Liu Q, Geng D, Tang Y, Xia Y, Wu D (October 2013). "BDNF signaling is necessary for the antidepressant-like effect of naringenin". Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 48C: 135–141. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2013.10.002. PMID 24121063.

- ^ Gao, K; Henning, S; Niu, Y; Youssefian, A; Seeram, N; Xu, A; Heber, D (2006). "The citrus flavonoid naringenin stimulates DNA repair in prostate cancer cells". The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 17 (2): 89–95. doi:10.1016/j.jnutbio.2005.05.009. PMID 16111881.

- ^ a b Katavic PL, Lamb K, Navarro H, Prisinzano TE (August 2007). "Flavonoids as opioid receptor ligands: identification and preliminary structure-activity relationships". J. Nat. Prod. 70 (8): 1278–82. doi:10.1021/np070194x. PMC 2265593. PMID 17685652.

- ^ Ibrahim AR (January 2000). "Sulfation of naringenin by Cunninghamella elegans". Phytochemistry. 53 (2): 209–12. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(99)00487-2. PMID 10680173.