Herbert Hoover

Herbert Hoover | |

|---|---|

Hoover in 1928 | |

| 31st President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1929 – March 4, 1933 | |

| Vice President | Charles Curtis |

| Preceded by | Calvin Coolidge |

| Succeeded by | Franklin D. Roosevelt |

| 3rd United States Secretary of Commerce | |

| In office March 5, 1921 – August 21, 1928 | |

| President |

|

| Preceded by | Joshua W. Alexander |

| Succeeded by | William F. Whiting |

| Director of the United States Food Administration | |

| In office August 21, 1917 – November 16, 1918 | |

| President | Woodrow Wilson |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished |

| Chairman of the Commission for Relief in Belgium | |

| In office October 22, 1914 – April 14, 1917 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Herbert Clark Hoover August 10, 1874 West Branch, Iowa, U.S. |

| Died | October 20, 1964 (aged 90) New York City, U.S. |

| Resting place | Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum |

| Political party | Independent (before 1920) Republican (1920–1964) |

| Spouse | |

| Children | |

| Education | Stanford University (BS) |

| Signature | |

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was the 31st president of the United States, serving from 1929 to 1933. A wealthy mining engineer before his presidency, Hoover led the wartime Commission for Relief in Belgium and was the director of the U.S. Food Administration, followed by post-war relief of Europe. A member of the Republican Party, he served as the U.S. Secretary of Commerce from 1921 to 1928 before being elected president in 1928. His presidency was dominated by the Great Depression, and his policies and methods to combat it were seen as lackluster. Amid his unpopularity, he decisively lost reelection to Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932.

Born to a Quaker family in West Branch, Iowa, Hoover grew up in Oregon. He was one of the first graduates of the new Stanford University in 1895. Hoover took a position with a London-based mining company working in Australia and China. He rapidly became a wealthy mining engineer. In 1914, the outbreak of World War I, he organized and headed the Commission for Relief in Belgium, an international relief organization that provided food to occupied Belgium. When the U.S. entered the war in 1917, President Woodrow Wilson appointed Hoover to lead the Food Administration. He became famous as his country's "food czar". After the war, Hoover led the American Relief Administration, which provided food to the starving millions in Central and Eastern Europe, especially Russia. Hoover's wartime service made him a favorite of many progressives, and he unsuccessfully sought the Republican nomination in the 1920 U.S. presidential election.

Hoover served as the secretary of commerce under Presidents Warren G. Harding and Calvin Coolidge. Hoover was an unusually active and visible Cabinet member, becoming known as "Secretary of Commerce and Under-Secretary of all other departments." He was influential in the development of air travel and radio. Hoover led the federal response to the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927. He won the Republican nomination in the 1928 presidential election and defeated Democratic candidate Al Smith in a landslide. In 1929, Hoover assumed the presidency. However, during his first year in office, the stock market crashed, signaling the onset of the Great Depression, which dominated Hoover's presidency until its end. His response to the depression was widely seen as lackluster and he scapegoated Mexican Americans for the economic crisis. Approximately one million Mexican Americans were forcibly "repatriated" to Mexico in a forced migration campaign known as the Mexican Repatriation even though a majority of them were born in the United States.

In the midst of the Great Depression, he was decisively defeated by Democratic nominee Franklin D. Roosevelt in the 1932 presidential election. Hoover's retirement was over 31 years long, one of the longest presidential retirements. He authored numerous works and became increasingly conservative in retirement. He strongly criticized Roosevelt's foreign policy and the New Deal. In the 1940s and 1950s, public opinion of Hoover improved, largely due to his service in various assignments for Presidents Harry S. Truman and Dwight D. Eisenhower, including chairing the influential Hoover Commission. Critical assessments of his presidency by historians and political scientists generally rank him as a significantly below-average president, although Hoover has received praise for his actions as a humanitarian and public official.[1][2][3]

Early life and education

Herbert Clark Hoover was born on August 10, 1874, in West Branch, Iowa.[a] His father, Jesse Hoover, was a blacksmith and farm implement store owner of German, Swiss, and English ancestry.[4] Hoover's mother, Hulda Randall Minthorn, was raised in Norwich, Ontario, Canada, before moving to Iowa in 1859. Like most other citizens of West Branch, Jesse and Hulda were Quakers.[5] Around age two "Bertie", as he was called during that time, contracted a serious bout of croup, and was momentarily thought to have died until resuscitated by his uncle, John Minthorn.[6] As a young child he was often referred to by his father as "my little stick in the mud" when he repeatedly got trapped in the mud crossing the unpaved street.[7] Herbert's family figured prominently in the town's public prayer life, due almost entirely to mother Hulda's role in the church.[8] As a child, Hoover consistently attended schools, but he did little reading on his own aside from the Bible.[9] Hoover's father, noted by the local paper for his "pleasant, sunshiny disposition", died in 1880 at the age of 34 of a sudden heart attack.[10] Hoover's mother died in 1884 of typhoid, leaving Hoover, his older brother, Theodore, and his younger sister, May, as orphans.[11] Hoover lived the next 18 months with his uncle Allen Hoover at a nearby farm.[12][13]

In November 1885, Hoover was sent to Newberg, Oregon, to live with his uncle John Minthorn, a Quaker physician and businessman whose own son had died the year before.[14] The Minthorn household was considered cultured and educational, and imparted a strong work ethic.[15] Much like West Branch, Newberg was a frontier town settled largely by Midwestern Quakers.[16] Minthorn ensured that Hoover received an education, but Hoover disliked the many chores assigned to him and often resented Minthorn. One observer described Hoover as "an orphan [who] seemed to be neglected in many ways".[17] Hoover attended Friends Pacific Academy (now George Fox University), but dropped out at the age of thirteen to become an office assistant for his uncle's real estate office (Oregon Land Company)[18] in Salem, Oregon. Though he did not attend high school, Hoover learned bookkeeping, typing, and mathematics at a night school.[19]

Hoover was a member of the inaugural "Pioneer Class" of Stanford University, entering in 1891 despite failing all the entrance exams except mathematics.[20][b] During his freshman year, he switched his major from mechanical engineering to geology after working for John Casper Branner, the chairman of Stanford's geology department. During his sophomore year, Sam Collins proposed founding, Romero Hall Boarding Club, the first student cooperative boarding house at Romero Hall, for "sociability and economy", which Hoover and William Foster Hidden co-founded.[22][23][24][25] Hoover was a mediocre student, and he spent much of his time working in various part-time jobs or participating in campus activities.[26] Though he was initially shy among fellow students, Hoover won election as student treasurer and became known for his distaste for fraternities and sororities.[27] He served as student manager of both the baseball and football teams, and helped organize the inaugural Big Game versus the University of California.[28] During the summers before and after his senior year, Hoover interned under economic geologist Waldemar Lindgren of the United States Geological Survey; these experiences convinced Hoover to pursue a career as a mining geologist.[29]

Mining engineer

Bewick, Moreing

When Hoover graduated from Stanford in 1895, the country was in the midst of the Panic of 1893 and he initially struggled to find a job.[27] He worked in various low-level mining jobs in the Sierra Nevada Mountains until persuading prominent mining engineer Louis Janin to hire him.[30] After working as a mine scout for a year, Hoover was hired by Bewick, Moreing & Co. ("Bewick"), a London-based company that operated gold mines in Western Australia.[31] He first went to Coolgardie, then the center of the Eastern Goldfields, which was actually in Western Australia, receiving a $5,000 salary (equivalent to $183,120 in 2023). Conditions were harsh in the goldfields; Hoover described the Coolgardie and Murchison rangelands on the edge of the Great Victoria Desert as a land of "black flies, red dust and white heat".[32][33]

Hoover traveled constantly across the Outback to evaluate and manage the company's mines.[34] He convinced Bewick to purchase the Sons of Gwalia gold mine, which proved to be one of the most successful mines in the region.[35] Partly due to Hoover's efforts, the company eventually controlled approximately 50 percent of gold production in Western Australia.[36] Hoover brought in many Italian immigrants to cut costs and counter the labour movement of the Australian miners.[37][38] During his time with the mining company, Hoover became opposed to measures such as a minimum wage and workers' compensation, feeling that they were unfair to owners. Hoover's work impressed his employers, and in 1898 he was promoted to junior partner.[39] An open feud developed between Hoover and his boss, Ernest Williams, but Bewick's leaders defused the situation by offering Hoover a compelling position in China.[40]

Upon arriving in China, Hoover developed gold mines near Tianjin on behalf of Bewick and the Chinese-owned Chinese Engineering and Mining Company.[41] He became deeply interested in Chinese history, but gave up on learning the language to a fluent level. He publicly warned that Chinese workers were inefficient and racially inferior.[42] He made recommendations to improve the lot of the Chinese worker, seeking to end the practice of imposing long-term servitude contracts and to institute reforms for workers based on merit.[43] The Boxer Rebellion broke out shortly after the Hoovers arrived in China, trapping them and numerous other foreign nationals until a multi-national military force defeated Boxer forces in the Battle of Tientsin. Fearing the imminent collapse of the Chinese government, the director of the Chinese Engineering and Mining Company agreed to establish a new Sino-British venture with Bewick. After they established effective control over the new Chinese mining company, Hoover became the operating partner in late 1901.[44]

In this role, Hoover continually traveled the world on behalf of Bewick, visiting mines operated by the company on different continents. Beginning in December 1902, the company faced mounting legal and financial issues after one of the partners admitted to having fraudulently sold stock in a mine. More issues arose in 1904 after the British government formed two separate royal commissions to investigate Bewick's labor practices and financial dealings in Western Australia. After the company lost a lawsuit Hoover began looking for a way to get out of the partnership, and he sold his shares in mid-1908.[45]

Sole proprietor

After leaving Bewick, Moreing, Hoover worked as a London-based independent mining consultant and financier. Though he had risen to prominence as a geologist and mine operator, Hoover focused much of his attention on raising money, restructuring corporate organizations, and financing new ventures.[46] He specialized in rejuvenating troubled mining operations, taking a share of the profits in exchange for his technical and financial expertise.[47] Hoover thought of himself and his associates as "engineering doctors to sick concerns", and he earned a reputation as a "doctor of sick mines".[48] He made investments on every continent and had offices in San Francisco; London; New York City; Paris; Petrograd; and Mandalay, British Burma.[49] By 1914, Hoover was a very wealthy man, with an estimated personal fortune of $4 million (equivalent to $121.67 million in 2023).[50]

Hoover co-founded the Zinc Corporation to extract zinc near the Australian city of Broken Hill, New South Wales.[51] The Zinc Corporation developed the froth flotation process to extract zinc from lead-silver ore[52] and operated the world's first selective ore differential flotation plant.[53] Hoover worked with the Burma Corporation, a British firm that produced silver, lead, and zinc in large quantities at the Namtu Bawdwin Mine.[54]: 90–96, 101–102 [55] He also helped increase copper production in Kyshtym, Russia, through the use of pyritic smelting. He also agreed to manage a separate mine in the Altai Mountains that, according to Hoover, "developed probably the greatest and richest single body of ore known in the world".[54]: 102–108 [56]

In his spare time, Hoover wrote. His lectures at Columbia and Stanford universities were published in 1909 as Principles of Mining, which became a standard textbook. The book reflects his move towards progressive ideals, as Hoover came to endorse eight-hour workdays and organized labor.[57] Hoover became deeply interested in the history of science, and he was especially drawn to the De re metallica, an influential 16th century work on mining and metallurgy by Georgius Agricola. In 1912, Hoover and his wife published the first English translation of De re metallica.[58] Hoover also joined the board of trustees at Stanford, and led a successful campaign to appoint John Branner as the university's president.[59]

Marriage and family

During his senior year at Stanford, Hoover became smitten with a classmate named Lou Henry, though his financial situation precluded marriage at that time.[27] The daughter of a banker from Monterey, California, Lou Henry decided to study geology at Stanford after attending a lecture delivered by John C. Branner.[60] Immediately after earning a promotion in 1898, Hoover cabled Lou Henry, asking her to marry him. After she cabled back her acceptance of the proposal, Hoover briefly returned to the United States for their wedding.[39] They would remain married until Lou Henry Hoover's death in 1944.[61] Hoover was the first president to be a widower since Woodrow Wilson.

Though his Quaker upbringing strongly influenced his career, Hoover rarely attended Quaker meetings during his adult life.[62][63] Hoover and his wife had two children: Herbert Hoover Jr. (born in 1903) and Allan Henry Hoover (born in 1907).[39] The Hoover family began living in London in 1902, though they frequently traveled as part of Hoover's career.[64] After 1916, the Hoovers began living in the United States, maintaining homes in Stanford, California, and Washington, D.C.[65] Hoover's great-grandaughter (through Allan) is conservative political commentator, strategist, media personality and author Margaret Hoover.[66]

Hoover's elder brother Theodore also studied mining engineering at Stanford, and returned there to become dean of the engineering school. In retirement, Theodore bought a large property on the remote north coast of Santa Cruz County. The Theodore J. Hoover Natural Preserve is now part of Big Basin State Park.

World War I and aftermath

Relief in Europe

World War I broke out in August 1914, pitting Germany and its allies against France and its allies. The German Schlieffen plan was to achieve a quick victory by marching through neutral Belgium to envelop the French Army east of Paris. The maneuver failed to reach Paris but the Germans did control nearly all of Belgium for the entire war. Hoover and other London-based American businessmen established a committee to organize the return of the roughly 100,000 Americans stranded in Europe. Hoover was appointed as the committee's chairman and, with the assent of Congress and the Wilson administration, took charge of the distribution of relief to Americans in Europe.[67] Hoover later stated, "I did not realize it at the moment, but on August 3, 1914, my career was over forever. I was on the slippery road of public life."[68] By early October 1914, Hoover's organization had distributed relief to at least 40,000 Americans.[69]

The German invasion of Belgium in August 1914 set off a food crisis in Belgium, which relied heavily on food imports. The Germans refused to take responsibility for feeding Belgian citizens in captured territory, and the British refused to lift their blockade of German-occupied Belgium unless the U.S. government supervised Belgian food imports as a neutral party in the war.[70] With the cooperation of the Wilson administration and the CNSA, a Belgian relief organization, Hoover established the Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB).[71] The CRB obtained and imported millions of tons of foodstuffs for the CNSA to distribute, and helped ensure that the German army did not appropriate the food. Private donations and government grants supplied the majority of its $11-million-a-month budget, and the CRB became a veritable independent republic of relief, with its own flag, navy, factories, mills, and railroads.[72][73][failed verification]

Hoover worked 14-hour days from London, administering the distribution of over two million tons of food to nine million war victims. In an early form of shuttle diplomacy, he crossed the North Sea forty times to meet with German authorities and persuade them to allow food shipments.[74] He also convinced British Chancellor of the Exchequer David Lloyd George to allow individuals to send money to the people of Belgium, thereby lessening workload of the CRB.[75] At the request of the French government, the CRB began delivering supplies to the people of German-occupied Northern France in 1915.[76] American diplomat Walter Page described Hoover as "probably the only man living who has privately (i.e., without holding office) negotiated understandings with the British, French, German, Dutch, and Belgian governments".[77][78]

U.S. Food Administration

War upon Germany was declared in April 1917, and American food was essential to Allied victory. With the U.S. mobilizing for war, President Wilson appointed Hoover to head the U.S. Food Administration, which was charged with ensuring the nation's food needs during the war.[79] Hoover had hoped to join the administration in some capacity since at least 1916, and he obtained the position after lobbying several members of Congress and Wilson's confidant, Edward M. House.[80] Earning the appellation of "food czar", Hoover recruited a volunteer force of hundreds of thousands of women and deployed propaganda in movie theaters, schools, and churches.[81] He carefully selected men to assist in the agency leadership—Alonzo E. Taylor (technical abilities), Robert Taft (political associations), Gifford Pinchot (agricultural influence), and Julius Barnes (business acumen).[82]

World War I had created a global food crisis that dramatically increased food prices and caused food riots and starvation in the countries at war. Hoover's chief goal as food czar was to provide supplies to the Allied Powers, but he also sought to stabilize domestic prices and to prevent domestic shortages.[83] Under the broad powers granted by the Food and Fuel Control Act, the Food Administration supervised food production throughout the United States, and the administration made use of its authority to buy, import, store, and sell food.[84] Determined to avoid rationing, Hoover established set days for people to avoid eating specified foods and save them for soldiers' rations: meatless Mondays, wheatless Wednesdays, and "when in doubt, eat potatoes". These policies were dubbed "Hooverizing" by government publicists, in spite of Hoover's continual orders that publicity should not mention him by name.[85] The Food Administration shipped 23 million metric tons of food to the Allied Powers, preventing their collapse and earning Hoover great acclaim.[86] As head of the Food Administration, Hoover gained a following in the United States, especially among progressives who saw in Hoover an expert administrator and symbol of efficiency.[87] He was elected to the American Philosophical Society during his tenure.[88]

Post-war relief in Europe

World War I came to an end in November 1918, but Europe continued to face a critical food situation; Hoover estimated that as many as 400 million people faced the possibility of starvation.[89] The United States Food Administration became the American Relief Administration (ARA), and Hoover was charged with providing food to Central and Eastern Europe.[90] In addition to providing relief, the ARA rebuilt infrastructure in an effort to rejuvenate the economy of Europe.[91] Throughout the Paris Peace Conference, Hoover served as a close adviser to President Wilson, and he largely shared Wilson's goals of establishing the League of Nations, settling borders on the basis of self-determination, and refraining from inflicting a harsh punishment on the defeated Central Powers.[92] The following year, the famed British economist John Maynard Keynes wrote in The Economic Consequences of the Peace that if Hoover's realism, "knowledge, magnanimity and disinterestedness" had found wider play in the councils of Paris, the world would have had "the Good Peace".[93] After U.S. government funding for the ARA expired in mid-1919, Hoover transformed the ARA into a private organization, raising millions of dollars from private donors.[90] He also established the European Children's Fund, which provided relief to fifteen million children across fourteen countries.[94]

Despite the opposition of Senator Henry Cabot Lodge and other Republicans, Hoover provided aid to the defeated German nation after the war, as well as relief to famine-stricken Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic.[90] Hoover condemned the Bolsheviks but warned President Wilson against an intervention in the Russian Civil War, as he viewed the White Russian forces as little better than the Bolsheviks and feared the possibility of a protracted U.S. involvement.[95] The Russian famine of 1921–22 claimed six million people, but the intervention of the ARA likely saved millions of lives.[96] When asked if he was not helping Bolshevism by providing relief, Hoover stated, "twenty million people are starving. Whatever their politics, they shall be fed!"[90] Reflecting the gratitude of many Europeans, in July 1922, Soviet author Maxim Gorky told Hoover that "your help will enter history as a unique, gigantic achievement, worthy of the greatest glory, which will long remain in the memory of millions of Russians whom you have saved from death".[97]

In 1919, Hoover established the Hoover War Collection at Stanford University. He donated all the files of the Commission for Relief in Belgium, the U.S. Food Administration, and the American Relief Administration, and pledged $50,000 as an endowment (equivalent to $878,695 in 2023). Scholars were sent to Europe to collect pamphlets, society publications, government documents, newspapers, posters, proclamations, and other ephemeral materials related to the war and the revolutions that followed it. The collection was renamed the Hoover War Library in 1922 and is now known as the Hoover Institution Library and Archives.[98] During the post-war period, Hoover also served as the president of the Federated American Engineering Societies.[99][100]

1920 election

Hoover had been little known among the American public before 1914, but his service in the Wilson administration established him as a contender in the 1920 presidential election. Hoover's wartime push for higher taxes, criticism of Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer's actions during the First Red Scare, and his advocacy for measures such as the minimum wage, forty-eight-hour workweek, and elimination of child labor made him appealing to progressives of both parties.[101] Despite his service in the Democratic administration of Woodrow Wilson, Hoover had never been closely affiliated with either the Democrats or the Republicans. He initially sought to avoid committing to any party in the 1920 election, hoping that either of the two major parties would draft him for president at their national conventions.[102] In March 1920, he changed strategy and declared himself a Republican; he was motivated in large part by the belief that the Democrats had little chance of winning.[103] Despite his national renown, Hoover's service in the Wilson administration had alienated farmers and the conservative Old Guard of the GOP, and his presidential candidacy fizzled out after his defeat in the California primary by favorite son Hiram Johnson. At the 1920 Republican National Convention, Warren G. Harding emerged as a compromise candidate after the convention became deadlocked between supporters of Johnson, Leonard Wood, and Frank Orren Lowden.[101] Hoover backed Harding's successful campaign in the general election, and he began laying the groundwork for a future presidential run by building a base of strong supporters in the Republican Party.[104]

Secretary of Commerce (1921–1928)

After his election as president in 1920, Harding rewarded Hoover for his support, offering to appoint him as either Secretary of the Interior or Secretary of Commerce. Secretary of Commerce was considered a minor Cabinet post, with limited and vaguely defined responsibilities, but Hoover decided to accept the position.[105] Hoover's progressive stances, continuing support for the League of Nations, and recent conversion to the Republican Party aroused opposition to his appointment from many Senate Republicans.[106] To overcome this opposition, Harding paired Hoover's nomination with that of conservative favorite Andrew Mellon as Secretary of the Treasury, and the nominations of both Hoover and Mellon were confirmed by the Senate. Hoover would serve as Secretary of Commerce from 1921 to 1928, serving under Harding and, after Harding's death in 1923, President Calvin Coolidge.[105] While some of the most prominent members of the Harding administration, including Attorney General Harry M. Daugherty and Secretary of Interior Albert B. Fall, were implicated in major scandals, Hoover emerged largely unscathed from investigations into the Harding administration.[107]

Hoover envisioned the Commerce Department as the hub of the nation's growth and stability.[108] His experience mobilizing the war-time economy convinced him that the federal government could promote efficiency by eliminating waste, increasing production, encouraging the adoption of data-based practices, investing in infrastructure, and conserving natural resources. Contemporaries described Hoover's approach as a "third alternative" between "unrestrained capitalism" and socialism, which was becoming increasingly popular in Europe.[109] Hoover sought to foster a balance among labor, capital, and the government, and for this, he has been variously labeled a corporatist or an associationalist.[110] A high priority was economic diplomacy, including promoting the growth of exports, as well as protection against monopolistic practices of foreign governments, especially regarding rubber and coffee.[111]

Hoover demanded, and received, authority to coordinate economic affairs throughout the government. He created many sub-departments and committees, overseeing and regulating everything from manufacturing statistics to air travel. In some instances, he "seized" control of responsibilities from other Cabinet departments when he deemed that they were not carrying out their responsibilities well; some began referring to him as the "Secretary of Commerce and Under-Secretary of all other departments".[108] In response to the Depression of 1920–21, he convinced Harding to assemble a presidential commission on unemployment, which encouraged local governments to engage in countercyclical infrastructure spending.[112] He endorsed much of Mellon's tax reduction program but favored a more progressive tax system and opposed the treasury secretary's efforts to eliminate the estate tax.[113]

Radio regulation and air travel

Between 1923 and 1929, the number of families with radios grew from 300,000 to 10 million,[114] and Hoover's tenure as Secretary of Commerce heavily influenced radio use in the United States. In the early and mid-1920s, Hoover's radio conferences played a key role in the organization, development, and regulation of radio broadcasting. Hoover also helped pass the Radio Act of 1927, which allowed the government to intervene and abolish radio stations that were deemed "non-useful" to the public. Hoover's attempts at regulating radio were not supported by all congressmen, and he received much opposition from the Senate and from radio station owners.[115][116][117]

Hoover was also influential in the early development of air travel, and he sought to create a thriving private industry boosted by indirect government subsidies. He encouraged the development of emergency landing fields, required all runways to be equipped with lights and radio beams, and encouraged farmers to make use of planes for crop dusting.[118] He also established the federal government's power to inspect planes and license pilots, setting a precedent for the later Federal Aviation Administration.[119]

As Commerce Secretary, Hoover hosted national conferences on street traffic collectively known as the National Conference on Street and Highway Safety. Hoover's chief objective was to address the growing casualty toll of traffic accidents, but the scope of the conferences grew and soon embraced motor vehicle standards, rules of the road, and urban traffic control. He left the invited interest groups to negotiate agreements among themselves, which were then presented for adoption by states and localities. Because automotive trade associations were the best organized, many of the positions taken by the conferences reflected their interests. The conferences issued a model Uniform Vehicle Code for adoption by the states and a Model Municipal Traffic Ordinance for adoption by cities. Both were widely influential, promoting greater uniformity between jurisdictions and tending to promote the automobile's priority in city streets.[120]

Hoover's image building

Phillips Payson O'Brien argues that Hoover had a Britain problem. He had spent so many years living in Britain and Australia, as an employee of British companies, there was a risk that he would be labeled a British tool. There were three solutions, all of which he tried in close collaboration with the media, which greatly admired him.[121] First came the image of the dispassionate scientist, emotionally uninvolved but always committed to finding and implementing the best possible solution. The second solution was to gain the reputation of a humanitarian, deeply concerned with the world's troubles, such as famine in Belgium, as well as specific American problems which he had solved as food commissioner during the world war. The third solution to was to fall back on that old tactic of twisting the British tail. He employed that solution in 1925–1926 in the worldwide rubber crisis. The American auto industry consumed 70% of the world's output, but British investors controlled much of the supply. Their plan was to drastically cut back on output from British Malaya, which had the effect of tripling rubber prices. Hoover energetically gave a series of speeches and interviews denouncing the monopolistic practice and demanding that it be ended. The American State Department wanted no such crisis and compromised the issue in 1926. By then Hoover had solved his image problem, and during his 1928 campaign he successfully squelched attacks that alleged he was too close to British interests.[122]

Other initiatives

With the goal of encouraging wise business investments, Hoover made the Commerce Department a clearinghouse of information. He recruited numerous academics from various fields and tasked them with publishing reports on different aspects of the economy, including steel production and films. To eliminate waste, he encouraged standardization of products like automobile tires and baby bottle nipples.[123] Other efforts at eliminating waste included reducing labor losses from trade disputes and seasonal fluctuations, reducing industrial losses from accident and injury, and reducing the amount of crude oil spilled during extraction and shipping. He promoted international trade by opening overseas offices to advise businessmen. Hoover was especially eager to promote Hollywood films overseas.[124] His "Own Your Own Home" campaign was a collaboration to promote ownership of single-family dwellings, with groups such as the Better Houses in America movement, the Architects' Small House Service Bureau, and the Home Modernizing Bureau. He worked with bankers and the savings and loan industry to promote the new long-term home mortgage, which dramatically stimulated home construction.[125] Other accomplishments included winning the agreement of U.S. Steel to adopt an eight-hour workday, and the fostering of the Colorado River Compact, a water rights compact among Southwestern states.[126]

Mississippi flood

The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 broke the banks and levees of the lower Mississippi River in early 1927, resulting in the flooding of millions of acres and leaving 1.5 million people displaced from their homes. Although disaster response did not fall under the duties of the Commerce Department, the governors of six states along the Mississippi River specifically asked President Coolidge to appoint Hoover to coordinate the response to the flood.[127] Believing that disaster response was not the domain of the federal government, Coolidge initially refused to become involved, but he eventually acceded to political pressure and appointed Hoover to chair a special committee to help the region.[128] Hoover established over one hundred tent cities and a fleet of more than six hundred vessels and raised $17 million (equivalent to $298.18 million in 2023). In large part due to his leadership during the flood crisis, by 1928, Hoover had begun to overshadow President Coolidge himself.[127] Though Hoover received wide acclaim for his role in the crisis, he ordered the suppression of reports of mistreatment of African Americans in refugee camps.[129] He did so with the cooperation of black American leader Robert Russa Moton, who was promised unprecedented influence once Hoover became president.[130]

Presidential election of 1928

Hoover quietly gathered support for a future presidential bid throughout the 1920s, but he carefully avoided alienating Coolidge, who possibly could have run for another term in the 1928 presidential election.[131] Along with the rest of the nation, he was surprised when Coolidge announced in August 1927 that he would not seek another term. With the impending retirement of Coolidge, Hoover immediately emerged as the front-runner for the 1928 Republican nomination, and he quickly put together a strong campaign team led by Hubert Work, Will H. Hays, and Reed Smoot.[132] Coolidge was unwilling to anoint Hoover as his successor; on one occasion he remarked that, "for six years that man has given me unsolicited advice—all of it bad".[133] Despite his lukewarm feelings towards Hoover, Coolidge had no desire to split the party by publicly opposing the popular Commerce Secretary's candidacy.[134]

Many wary Republican leaders cast about for an alternative candidate, such as Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon or former secretary of state Charles Evans Hughes.[135] However, Hughes and Mellon declined to run, and other potential contenders like Frank Orren Lowden and Vice President Charles G. Dawes failed to garner widespread support.[136] Hoover won the presidential nomination on the first ballot of the 1928 Republican National Convention. Convention delegates considered re-nominating Vice President Charles Dawes to be Hoover's running mate, but Coolidge, who hated Dawes, remarked that this would be "a personal affront" to him. The convention instead selected Senator Charles Curtis of Kansas.[137] Hoover accepted the nomination at Stanford Stadium, telling a huge crowd that he would continue the policies of the Harding and Coolidge administrations.[138] The Democrats nominated New York governor Al Smith, who became the first Catholic major party nominee for president.[139]

Hoover submitted his resignation as Commerce Secretary on July 7, but Coolidge kept him on until August 21 to wind up pending business.[140][141] Hoover centered his campaign around the Republican record of peace and prosperity, as well as his own reputation as a successful engineer and public official. Averse to giving political speeches, Hoover largely stayed out of the fray and left the campaigning to Curtis and other Republicans.[142] Smith was more charismatic and gregarious than Hoover, but his campaign was damaged by anti-Catholicism and his overt opposition to Prohibition. Hoover had never been a strong proponent of Prohibition, but he accepted the Republican Party's plank in favor of it and issued an ambivalent statement calling Prohibition "a great social and economic experiment, noble in motive and far-reaching in purpose".[143] In the South, Hoover and the national party pursued a "lily-white" strategy, removing black Republicans from leadership positions in an attempt to curry favor with white Southerners.[144]

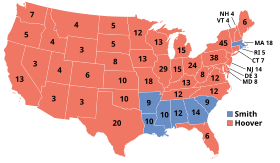

Hoover maintained polling leads throughout the 1928 campaign, and he decisively defeated Smith on election day, taking 58 percent of the popular vote and 444 of the 531 electoral votes.[145] Historians agree that Hoover's national reputation and the booming economy, combined with deep splits in the Democratic Party over religion and Prohibition, guaranteed his landslide victory.[146] Hoover's appeal to Southern white voters succeeded in cracking the "Solid South", and he won five Southern states.[147] Hoover's victory was positively received by newspapers; one wrote that Hoover would "drive so forcefully at the tasks now before the nation that the end of his eight years as president will find us looking back on an era of prodigious achievement".[148]

Hoover's detractors wondered why he did not do anything to reapportion congress after the 1920 United States census which saw an increase in urban and immigrant populations. The 1920 census was the first and only decennial census where the results were not used to reapportion Congress, which ultimately influenced the 1928 Electoral College and impacted the presidential election.[149][150]

Presidency (1929–1933)

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in the United States |

|---|

|

Hoover saw the presidency as a vehicle for improving the conditions of all Americans by encouraging public-private cooperation—what he termed "volunteerism". He tended to oppose governmental coercion or intervention, as he thought they infringed on American ideals of individualism and self-reliance.[151] The first major bill that he signed, the Agricultural Marketing Act of 1929, established the Federal Farm Board in order to stabilize farm prices.[152] Hoover made extensive use of commissions to study issues and propose solutions, and many of those commissions were sponsored by private donors rather than by the government. One of the commissions started by Hoover, the Research Committee on Social Trends, was tasked with surveying the entirety of American society.[153] He appointed a Cabinet consisting largely of wealthy, business-oriented conservatives,[154] including Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon.[155] Lou Henry Hoover was an activist First Lady. She typified the new woman of the post–World War I era: intelligent, robust, and aware of multiple female possibilities.[156]

Great Depression

On taking office, Hoover said that "given the chance to go forward with the policies of the last eight years, we shall soon with the help of God, be in sight of the day when poverty will be banished from this nation".[157] Having seen the fruits of prosperity brought by technological progress, many shared Hoover's optimism, and the already bullish stock market climbed even higher on Hoover's accession.[158] This optimism concealed several threats to sustained U.S. economic growth, including a persistent farm crisis, a saturation of consumer goods like automobiles, and growing income inequality.[159] Most dangerous of all to the economy was excessive speculation that had raised stock prices far beyond their value.[160] Some regulators and bankers had warned Coolidge and Hoover that a failure to curb speculation would lead to "one of the greatest financial catastrophes that this country has ever seen," but both presidents were reluctant to become involved with the workings of the Federal Reserve System, which regulated banks.[161]

In late October 1929, the stock market crashed, and the worldwide economy began to spiral downward into the Great Depression.[162] The causes of the Great Depression remain a matter of debate,[163] but Hoover viewed a lack of confidence in the financial system as the fundamental economic problem facing the nation.[164] He sought to avoid direct federal intervention, believing that the best way to bolster the economy was through the strengthening of businesses such as banks and railroads. He also feared that allowing individuals on the "dole" would permanently weaken the country.[165] Instead, Hoover strongly believed that local governments and private giving should address the needs of individuals.[166]

Early policies

Though he attempted to put a positive spin on Black Tuesday, Hoover moved quickly to address the stock market collapse.[167] In the days following Black Tuesday, Hoover gathered business and labor leaders, asking them to avoid wage cuts and work stoppages while the country faced what he believed would be a short recession similar to the Depression of 1920–21.[168] Hoover also convinced railroads and public utilities to increase spending on construction and maintenance, and the Federal Reserve announced that it would cut interest rates.[169] In early 1930, Hoover acquired from Congress an additional $100 million to continue the Federal Farm Board lending and purchasing policies.[170] These actions were collectively designed to prevent a cycle of deflation and provide a fiscal stimulus.[169] At the same time, Hoover opposed congressional proposals to provide federal relief to the unemployed, as he believed that such programs were the responsibility of state and local governments and philanthropic organizations.[171]

Hoover had taken office hoping to raise agricultural tariffs in order to help farmers reeling from the farm crisis of the 1920s, but his attempt to raise agricultural tariffs became connected with a bill that broadly raised tariffs.[172] Hoover refused to become closely involved in the congressional debate over the tariff, and Congress produced a tariff bill that raised rates for many goods.[173] Despite the widespread unpopularity of the bill, Hoover felt that he could not reject the main legislative accomplishment of the Republican-controlled 71st Congress. Over the objection of many economists, Hoover signed the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act into law in June 1930.[174] Canada, France, and other nations retaliated by raising tariffs, resulting in a contraction of international trade and a worsening of the economy.[175] Progressive Republicans such as Senator William E. Borah of Idaho were outraged when Hoover signed the tariff act, and Hoover's relations with that wing of the party never recovered.[176]

Later policies

By the end of 1930, the national unemployment rate had reached 11.9 percent, but it was not yet clear to most Americans that the economic downturn would be worse than the Depression of 1920–21.[177] A series of bank failures in late 1930 heralded a larger collapse of the economy in 1931.[178] While other countries left the gold standard, Hoover refused to abandon it;[179] he derided any other monetary system as "collectivism".[180] Hoover viewed the weak European economy as a major cause of economic troubles in the United States.[181] In response to the collapse of the German economy, Hoover marshaled congressional support behind a one-year moratorium on European war debts.[182] The Hoover Moratorium was warmly received in Europe and the United States, but Germany remained on the brink of defaulting on its loans.[183] As the worldwide economy worsened, democratic governments fell; in Germany, Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler assumed power and dismantled the Weimar Republic.[184]

By mid-1931, the unemployment rate had reached 15 percent, giving rise to growing fears that the country was experiencing a depression far worse than recent economic downturns.[185] A reserved man with a fear of public speaking, Hoover allowed his opponents in the Democratic Party to define him as cold, incompetent, reactionary, and out-of-touch.[186] Hoover's opponents developed defamatory epithets to discredit him, such as "Hooverville" (the shanty towns and homeless encampments), "Hoover leather" (cardboard used to cover holes in the soles of shoes), and "Hoover blanket" (old newspaper used to cover oneself from the cold).[187] While Hoover continued to resist direct federal relief efforts, Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt of New York launched the Temporary Emergency Relief Administration to provide aid to the unemployed. Democrats positioned the program as a kinder alternative to Hoover's alleged apathy towards the unemployed, despite Hoover's belief that such programs were the responsibility of state and local governments.[188]

The economy continued to worsen, with unemployment rates nearing 23 percent in early 1932,[189] and Hoover finally heeded calls for more direct federal intervention.[190] In January 1932, he convinced Congress to authorize the establishment of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC), which would provide government-secured loans to financial institutions, railroads, and local governments.[191] The RFC saved numerous businesses from failure, but it failed to stimulate commercial lending as much as Hoover had hoped, partly because it was run by conservative bankers unwilling to make riskier loans.[192] The same month the RFC was established, Hoover signed the Federal Home Loan Bank Act, establishing 12 district banks overseen by a Federal Home Loan Bank Board in a manner similar to the Federal Reserve System.[193] He also helped arrange passage of the Glass–Steagall Act of 1932, emergency banking legislation designed to expand banking credit by expanding the collateral on which Federal Reserve banks were authorized to lend.[194] As these measures failed to stem the economic crisis, Hoover signed the Emergency Relief and Construction Act, a $2 billion public works bill, in July 1932.[189]

Budget policy

After a decade of budget surpluses, the federal government experienced a budget deficit in 1931.[195] Though some economists, like William Trufant Foster, favored deficit spending to address the Great Depression, most politicians and economists believed in the necessity of keeping a balanced budget.[196] In late 1931, Hoover proposed a tax plan to increase tax revenue by 30 percent, resulting in the passage of the Revenue Act of 1932.[197] The act increased taxes across the board, rolling back much of the tax cut reduction program Mellon had presided over during the 1920s. Top earners were taxed at 63 percent on their net income, the highest rate since the early 1920s. The act also doubled the top estate tax rate, cut personal income tax exemptions, eliminated the corporate income tax exemption, and raised corporate tax rates.[198] Despite the passage of the Revenue Act, the federal government continued to run a budget deficit.[199]

Civil rights and Mexican Repatriation

Hoover seldom mentioned civil rights while he was president. He believed that African Americans and other races could improve themselves with education and individual initiative.[200] Hoover appointed more African Americans to federal positions than Harding and Coolidge combined, but many African American leaders condemned various aspects of the Hoover administration, including Hoover's unwillingness to push for a federal anti-lynching law.[201] Hoover also continued to pursue the lily-white strategy, removing African Americans from positions of leadership in the Republican Party in an attempt to end the Democratic Party's dominance in the South.[202] Though Robert Moton and some other black leaders accepted the lily-white strategy as a temporary measure, most African American leaders were outraged.[203] Hoover further alienated black leaders by nominating conservative Southern judge John J. Parker to the Supreme Court; Parker's nomination ultimately failed in the Senate due to opposition from the NAACP and organized labor.[204] Many black voters switched to the Democratic Party in the 1932 election, and African Americans would later become an important part of Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal coalition.[205]

As part of his efforts to limit unemployment, Hoover sought to cut immigration to the United States, and in 1930 he promulgated an executive order requiring individuals to have employment before migrating to the United States.[206] The Hoover Administration began a campaign to prosecute illegal immigrants in the United States, which most strongly affected Mexican Americans, especially those living in Southern California.[207] Many of the deportations were overseen by state and local authorities who acted on the encouragement of the Hoover Administration.[208] During the 1930s, approximately one million Mexican Americans were forcibly "repatriated" to Mexico; approximately sixty percent of those deported were birthright citizens.[209] According to legal professor Kevin R. Johnson, the repatriation campaign meets the modern legal standards of ethnic cleansing, as it involved the forced removal of a racial minority by government actors.[210]

Hoover reorganized the Bureau of Indian Affairs to limit exploitation of Native Americans.[211]

Prohibition

On taking office, Hoover urged Americans to obey the Eighteenth Amendment and the Volstead Act, which had established Prohibition across the United States.[212] To make public policy recommendations regarding Prohibition, he created the Wickersham Commission.[213] Hoover had hoped that the commission's public report would buttress his stance in favor of Prohibition, but the report criticized the enforcement of the Volstead Act and noted the growing public opposition to Prohibition. After the Wickersham Report was published in 1931, Hoover rejected the advice of some of his closest allies and refused to endorse any revision of the Volstead Act or the Eighteenth Amendment, as he feared doing so would undermine his support among Prohibition advocates.[214] As public opinion increasingly turned against Prohibition, more and more people flouted the law, and a grassroots movement began working in earnest for Prohibition's repeal.[215] In January 1933, a constitutional amendment repealing the Eighteenth Amendment was approved by Congress and submitted to the states for ratification. By December 1933, it had been ratified by the requisite number of states to become the Twenty-first Amendment.[216]

Foreign relations

According to Leuchtenburg, Hoover was "the last American president to take office with no conspicuous need to pay attention to the rest of the world". Nevertheless, during Hoover's term, the world order established in the immediate aftermath of World War I began to crumble.[217] As president, Hoover largely made good on his pledge made prior to assuming office not to interfere in Latin America's internal affairs. In 1930, he released the Clark Memorandum, a rejection of the Roosevelt Corollary and a move towards non-interventionism in Latin America. Hoover did not completely refrain from the use of the military in Latin American affairs; he thrice threatened intervention in the Dominican Republic, and he sent warships to El Salvador to support the government against a left-wing revolution.[218] Notwithstanding those actions, he wound down the Banana Wars, ending the occupation of Nicaragua and nearly bringing an end to the occupation of Haiti.[219]

Hoover placed a priority on disarmament, which he hoped would allow the United States to shift money from the military to domestic needs.[220] Hoover and Secretary of State Henry L. Stimson focused on extending the 1922 Washington Naval Treaty, which sought to prevent a naval arms race.[221] As a result of Hoover's efforts, the United States and other major naval powers signed the 1930 London Naval Treaty.[222] The treaty represented the first time that the naval powers had agreed to cap their tonnage of auxiliary vessels, as previous agreements had only affected capital ships.[223]

At the 1932 World Disarmament Conference, Hoover urged further cutbacks in armaments and the outlawing of tanks and bombers, but his proposals were not adopted.[223]

In 1931, Japan invaded Manchuria, defeating the Republic of China's National Revolutionary Army and establishing Manchukuo, a puppet state. The Hoover administration deplored the invasion, but also sought to avoid antagonizing the Japanese, fearing that taking too strong a stand would weaken the moderate forces in the Japanese government and alienate a potential ally against the Soviet Union, which he saw as a much greater threat.[224] In response to the Japanese invasion, Hoover and Secretary of State Stimson outlined the Stimson Doctrine, which held that the United States would not recognize territories gained by force.[225]

Bonus Army

Thousands of World War I veterans and their families demonstrated and camped out in Washington, DC, during June 1932, calling for immediate payment of bonuses that had been promised by the World War Adjusted Compensation Act in 1924; the terms of the act called for payment of the bonuses in 1945. Although offered money by Congress to return home, some members of the "Bonus Army" remained. Washington police attempted to disperse the demonstrators, but they were outnumbered and unsuccessful. Shots were fired by the police in a futile attempt to attain order, and two protesters were killed while many officers were injured. Hoover sent U.S. Army forces led by General Douglas MacArthur to the protests. MacArthur, believing he was fighting a Communist revolution, chose to clear out the camp with military force. Though Hoover had not ordered MacArthur's clearing out of the protesters, he endorsed it after the fact.[226] The incident proved embarrassing for the Hoover administration and hurt his bid for re-election.[227]

1932 re-election campaign

By mid-1931 few observers thought that Hoover had much hope of winning a second term in the midst of the ongoing economic crisis.[228] The Republican expectations were so bleak that Hoover faced no serious opposition for re-nomination at the 1932 Republican National Convention. Coolidge and other prominent Republicans all passed on the opportunity to challenge Hoover.[229] Franklin D. Roosevelt won the presidential nomination on the fourth ballot of the 1932 Democratic National Convention, defeating the 1928 Democratic nominee, Al Smith. The Democrats attacked Hoover as the cause of the Great Depression, and for being indifferent to the suffering of millions.[230] As Governor of New York, Roosevelt had called on the New York legislature to provide aid for the needy, establishing Roosevelt's reputation for being more favorable toward government interventionism during the economic crisis.[231] The Democratic Party, including Al Smith and other national leaders, coalesced behind Roosevelt, while progressive Republicans like George Norris and Robert La Follette Jr. deserted Hoover.[232] Prohibition was increasingly unpopular and wets offered the argument that states and localities needed the tax money. Hoover proposed a new constitutional amendment that was vague on particulars. Roosevelt's platform promised repeal of the 18th Amendment.[233][234]

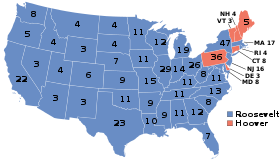

Hoover originally planned to make only one or two major speeches and to leave the rest of the campaigning to proxies, as sitting presidents had traditionally done. However, encouraged by Republican pleas and outraged by Democratic claims, Hoover entered the public fray. In his nine major radio addresses Hoover primarily defended his administration and his philosophy of government, urging voters to hold to the "foundations of experience" and reject the notion that government interventionism could save the country from the Depression.[235] In his campaign trips around the country, Hoover was faced with perhaps the most hostile crowds ever seen by a sitting president. Besides having his train and motorcades pelted with eggs and rotten fruit, he was often heckled while speaking, and on several occasions, the Secret Service halted attempts to hurt Hoover, including capturing one man nearing Hoover carrying sticks of dynamite, and another already having removed several spikes from the rails in front of the president's train.[236] Hoover's attempts to vindicate his administration fell on deaf ears, as much of the public blamed his administration for the depression.[237] In the electoral vote, Hoover lost 59–472, carrying six states.[238] Hoover won 39.6 percent of the popular vote, a plunge of 18.6 percentage points from his result in the 1928 election.[239]

Post-presidency (1933–1964)

Roosevelt administration

Opposition to New Deal

Hoover departed from Washington in March 1933, bitter at his election loss and continuing unpopularity.[240] As Coolidge, Harding, Wilson, and Taft had all died during the 1920s or early 1930s and Roosevelt died in office, Hoover was the sole living former president from 1933 to 1953. He and his wife lived in Palo Alto until her death in 1944, at which point Hoover began to live permanently at the Waldorf Astoria hotel in New York City.[241] During the 1930s, Hoover increasingly self-identified as a conservative.[242] He closely followed national events after leaving public office, becoming a constant critic of Franklin Roosevelt. In response to continued attacks on his character and presidency, Hoover wrote more than two dozen books, including The Challenge to Liberty (1934), which harshly criticized Roosevelt's New Deal. Hoover described the New Deal's National Recovery Administration and Agricultural Adjustment Administration as "fascistic", and he called the 1933 Banking Act a "move to gigantic socialism".[243]

Only 58 when he left office, Hoover held out hope for another term as president throughout the 1930s. At the 1936 Republican National Convention, Hoover's speech attacking the New Deal was well received, but the nomination went to Kansas governor Alf Landon.[244] In the general election, Hoover delivered numerous well-publicized speeches on behalf of Landon, but Landon was defeated by Roosevelt.[245] Though Hoover was eager to oppose Roosevelt at every turn, Senator Arthur Vandenberg and other Republicans urged the still-unpopular Hoover to remain out of the fray during the debate over Roosevelt's proposed Judiciary Reorganization Bill of 1937. At the 1940 Republican National Convention, he again hoped for the presidential nomination, but it went to the internationalist Wendell Willkie, who lost to Roosevelt in the general election.[246] Hoover remained the latest president to run for re-election after leaving office until 2022 when Donald Trump, following his win in 2016 and loss in 2020, announced his bid for 2024 presidential election.[247]

World War II

During a 1938 trip to Europe, Hoover met with Adolf Hitler and stayed at Hermann Göring's hunting lodge.[248] He expressed dismay at the persecution of Jews in Germany and believed that Hitler was mad, but did not present a threat to the U.S. Instead, Hoover believed that Roosevelt posed the biggest threat to peace, holding that Roosevelt's policies provoked Japan and discouraged France and the United Kingdom from reaching an "accommodation" with Germany.[249] After the September 1939 invasion of Poland by Germany, Hoover opposed U.S. involvement in World War II, including the Lend-Lease policy.[250] He was active in the isolationist America First Committee.[251] He rejected Roosevelt's offers to help coordinate relief in Europe,[252] but, with the help of old friends from the CRB, helped establish the Commission for Polish Relief.[253] After the beginning of the occupation of Belgium in 1940, Hoover provided aid for Belgian civilians, though this aid was described as unnecessary by German broadcasts.[254][255]

In December 1939, sympathetic Americans led by Hoover formed the Finnish Relief Fund to donate money to aid Finnish civilians and refugees after the Soviet Union had started the Winter War by attacking Finland, which had outraged Americans.[256] By the end of January, it had already sent more than two million dollars to the Finns.[257]

During a radio broadcast on June 29, 1941, one week after the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union, Hoover disparaged any "tacit alliance" between the U.S. and the USSR, stating, "if we join the war and Stalin wins, we have aided him to impose more communism on Europe and the world... War alongside Stalin to impose freedom is more than a travesty. It is a tragedy."[258] Much to his frustration, Hoover was not called upon to serve after the United States entered World War II due to his differences with Roosevelt and his continuing unpopularity.[241] He did not pursue the presidential nomination at the 1944 Republican National Convention, and, at the request of Republican nominee Thomas E. Dewey, refrained from campaigning during the general election.[259] In 1945, Hoover advised President Harry S. Truman to drop the United States' demand for the unconditional surrender of Japan because of the high projected casualties of the planned invasion of Japan, although Hoover was unaware of the Manhattan Project and the atomic bomb.[260]

In 1943, Hoover expressed his support for Zionism. He advocated population transfers of Palestinians to Iraq.[261]

Post-World War II

Following World War II, Hoover befriended President Truman despite their ideological differences.[262] Because of Hoover's experience with Germany at the end of World War I, in 1946 Truman selected the former president to tour Allied-occupied Germany and Rome, Italy to ascertain the food needs of the occupied nations. After touring Germany, Hoover produced a number of reports critical of U.S. occupation policy.[263] He stated in one report that "there is the illusion that the New Germany left after the annexations can be reduced to a 'pastoral state.' It cannot be done unless we exterminate or move 25,000,000 people out of it."[264] On Hoover's initiative, a school meals program in the American and British occupation zones of Germany was begun on April 14, 1947; the program served 3,500,000 children.[265]

| External audio | |

|---|---|

Even more important, in 1947 Truman appointed Hoover to lead the Commission on Organization of the Executive Branch of the Government a new high level study. Truman accepted some of the recommendations of the "Hoover Commission" for eliminating waste, fraud, and inefficiency, consolidating agencies, and strengthening White House control of policy.[267][268] Though Hoover had opposed Roosevelt's concentration of power in the 1930s, he believed that a stronger presidency was required with the advent of the Atomic Age.[269] During the 1948 presidential election, Hoover supported Republican nominee Thomas E. Dewey's unsuccessful campaign against Truman, but he remained on good terms with Truman.[270] Hoover favored the United Nations in principle, but he opposed granting membership to the Soviet Union and other Communist states. He viewed the Soviet Union to be as morally repugnant as Nazi Germany and supported the efforts of Richard Nixon and others to expose Communists in the United States.[271]

In 1949, Dewey, as governor of New York, offered Hoover the Senate seat vacated by Robert F. Wagner. It was a matter of being senator for only two months and he declined.[272]

Hoover backed conservative leader Robert A. Taft at the 1952 Republican National Convention, but the party's presidential nomination instead went to Dwight D. Eisenhower, who went on to win the 1952 election.[273] Though Eisenhower appointed Hoover to another presidential commission, Hoover disliked Eisenhower, faulting the latter's failure to roll back the New Deal.[269] Hoover's public work helped to rehabilitate his reputation, as did his use of self-deprecating humor; he occasionally remarked that "I am the only person of distinction who's ever had a depression named after him."[274] In 1958, Congress passed the Former Presidents Act, offering a $25,000 yearly pension (equivalent to $264,014 in 2023) to each former president.[275] Hoover took the pension even though he did not need the money, possibly to avoid embarrassing Truman, whose allegedly precarious financial status played a role in the law's enactment.[276] In the early 1960s, President John F. Kennedy offered Hoover various positions; Hoover declined the offers but defended the Kennedy administration after the Bay of Pigs Invasion, Cuban Missile Crisis and was personally distraught by Kennedy's assassination in 1963.[277]

Hoover wrote several books during his retirement, including The Ordeal of Woodrow Wilson, in which he strongly defended Wilson's actions at the Paris Peace Conference.[278] In 1944, he began working on Freedom Betrayed, which he often referred to as his "magnum opus". In Freedom Betrayed, Hoover strongly critiques Roosevelt's foreign policy, especially Roosevelt's decision to recognize the Soviet Union in order to provide aid to that country during World War II.[279] The book was published in 2012 after being edited by historian George H. Nash.[280]

Death

Hoover faced three major illnesses during the last two years of his life, including an August 1962 operation in which a growth on his large intestine was removed.[281][282] He died in New York City on October 20, 1964, following massive internal bleeding.[283] Though Hoover's last spoken words are unknown, his last-known written words were a get-well message to his friend former President Harry S. Truman, six days before his death, after he heard that Truman had sustained injuries from slipping in a bathroom: "Bathtubs are a menace to ex-presidents for as you may recall a bathtub rose up and fractured my vertebrae when I was in Venezuela on your world famine mission in 1946. My warmest sympathy and best wishes for your recovery."[284] Two months earlier, on August 10, Hoover reached the age of 90, only the second U.S. president (after John Adams) to do so. When asked how he felt on reaching the milestone, Hoover replied, "Too old."[282] At the time of his death, Hoover had been out of office for over 31 years (11,553 days all together). This was the longest retirement in presidential history until Jimmy Carter broke that record in September 2012.[285]

Hoover was honored with a state funeral in which he lay in state in the United States Capitol rotunda.[286] President Lyndon Johnson and First Lady Lady Bird Johnson attended, along with former presidents Truman and Eisenhower. Then, on October 25, he was buried in West Branch, Iowa, near his presidential library and birthplace on the grounds of the Herbert Hoover National Historic Site. Afterwards, Hoover's wife, Lou Henry Hoover, who had been buried in Palo Alto, California, following her death in 1944, was re-interred beside him.[287] Hoover was the last surviving member of the Harding and Coolidge cabinets. John Nance Garner (the speaker of the House during the second half of Hoover's term) was the only person in Hoover's United States presidential line of succession he did not outlive.

Legacy

Historical reputation

Hoover was extremely unpopular when he left office after the 1932 election, and his historical reputation would not begin to recover until the 1970s. According to Professor David E. Hamilton, historians have credited Hoover for his genuine belief in voluntarism and cooperation, as well as the innovation of some of his programs. However, Hamilton also notes that Hoover was politically inept and failed to recognize the severity of the Great Depression.[288] Nicholas Lemann writes that Hoover has been remembered "as the man who was too rigidly conservative to react adeptly to the Depression, as the hapless foil to the great Franklin Roosevelt, and as the politician who managed to turn a Republican country into a Democratic one".[3] Polls of historians and political scientists have generally ranked Hoover in the bottom third of presidents. A 2018 poll of the American Political Science Association's Presidents and Executive Politics section ranked Hoover as the 36th best president.[289] A 2017 C-SPAN poll of historians also ranked Hoover as the 36th best president.[290]

Although Hoover is generally regarded as having had a failed presidency, he has also received praise for his actions as a humanitarian and public official.[3] Biographer Glen Jeansonne writes that Hoover was "one of the most extraordinary Americans of modern times," adding that Hoover "led a life that was a prototypical Horatio Alger story, except that Horatio Alger stories stop at the pinnacle of success".[291] Biographer Kenneth Whyte writes that, "the question of where Hoover belongs in the American political tradition remains a loaded one to this day. While he clearly played important roles in the development of both the progressive and conservative traditions, neither side will embrace him for fear of contamination with the other."[292]

Historian Richard Pipes, on his actions leading the American Relief Administration, said of him: "Many statesmen occupy a prominent place in history for having sent millions to their death; Herbert Hoover, maligned for his performance as President, and soon forgotten in Russia, has the rare distinction of having saved millions."[293]

Views of race

Although racist remarks and humor were common at the time, Hoover never indulged in them while president, and deliberate discrimination was anathema to him. Like many of his peers, Hoover considered white people to be inherently superior to black people, considering the "mixture of bloods disadvantageous". He did think education and work would improve black people's standing, hence his support for the Tuskegee Institute.[294] His wife Lou Henry Hoover broke the color bar as first lady by inviting Jessie De Priest, wife of the first black congressman elected in several decades, to a traditional tea for the wives of congressmen, as well as later inviting the Tuskegee Institute choir (then under the direction of William Dawson).[295]

Although he thought of himself as a friend to black people and an advocate for their progress,[296] many of his black contemporaries had a different view. W. E. B. Du Bois described him as an "undemocratic racist who saw blacks as a species of 'sub-men'".[294] Some historians trace the disaffection of African-Americans with the Republican party to his time in office especially due to his attempt to remove African-Americans from leadership in the Republican party in the South.[294]

Hoover's time in China shaped his views of Asian people and Asian-Americans. He erroneously wrote that "no world-startling mechanical invention" had come from China, claiming this was due to Chinese people not possessing the same mechanical instincts as Europeans.[294] This may have influenced his decision to reduce immigration through restrictions on visas.[297]

Memorials

The Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum is located in West Branch, Iowa next to the Herbert Hoover National Historic Site. The library is one of thirteen presidential libraries run by the National Archives and Records Administration. The Hoover–Minthorn House, where Hoover lived from 1885 to 1891, is located in Newberg, Oregon. His Rapidan fishing camp in Virginia, which he donated to the government in 1933, is now a National Historic Landmark within the Shenandoah National Park. The Lou Henry and Herbert Hoover House, built in 1919 in Stanford, California, is now the official residence of the president of Stanford University, and a National Historic Landmark. Also located at Stanford is the Hoover Institution, a think tank and research institution started by Hoover.

Hoover has been memorialized in the names of several things, including the Hoover Dam on the Colorado River and numerous elementary, middle, and high schools across the United States. Two minor planets, 932 Hooveria[298] and 1363 Herberta, are named in his honor.[299] The Polish capital of Warsaw has a square named after Hoover,[300] and the historic townsite of Gwalia, Western Australia contains the Hoover House Bed and Breakfast, where Hoover resided while managing and visiting the mine during the first decade of the twentieth century.[301] A medicine ball game known as Hooverball is named for Hoover; it was invented by White House physician Admiral Joel T. Boone to help Hoover keep fit while serving as president.[302]

-

Hoover Presidential Library located in West Branch, Iowa

-

A plaque in Poznań honoring Hoover

-

Medal depicting Hoover, by Devreese Godefroi

Other honors

Hoover was inducted into the National Mining Hall of Fame in 1988 (inaugural class).[303] His wife was inducted into the hall in 1990.[304]

Hoover was inducted into the Australian Prospectors and Miners' Hall of Fame in the category Directors and Management.[305]

Hoover was awarded an honorary doctorate by the Charles University in Prague and University of Helsinki in March 1938.[306][307][308] The ceremonial sword is today on display in the lobby of the Hoover tower.

See also

- List of presidents of the United States

- List of presidents of the United States by previous experience

- Progressive Era

- Roaring Twenties

Explanatory notes

- ^ Hoover later became the first president born west of the Mississippi River, and remains the only president born in Iowa.[4]

- ^ Hoover later claimed to be the first student at Stanford, by virtue of having been the first person in the first class to sleep in the dormitory.[21]

References

Citations

- ^ Levinson, Martin H. (2011). "Indexing and Dating America's 'Worst' Presidents". ETC: A Review of General Semantics. 68 (2): 147–155. ISSN 0014-164X. JSTOR 42579110.

- ^ Merry, Robert W. (January 3, 2021). "RANKED: Historians Don't Think Much of These Five U.S. Presidents". The National Interest. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ^ a b c Lemann, Nicholas (October 23, 2017). "Hating on Herbert Hoover". The New Yorker. Retrieved February 18, 2019.

- ^ a b Burner 1996, p. 4.

- ^ Whyte 2017, pp. 5–10.

- ^ Burner, p. 6.

- ^ Burner, p. 7.

- ^ Burner, p. 9.

- ^ Whyte 2017, pp. 13–14, 31.

- ^ Burner 1996, p. 10.

- ^ Whyte 2017, pp. 17–18.

- ^ "Column: President spent days of his boyhood only 90 miles away". August 19, 2017.

- ^ "National Park Service – The Presidents (Herbert Hoover)".

- ^ "Timeline". December 6, 2017.

- ^ Burner 1996, p. 12.

- ^ Whyte 2017, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Whyte 2017, pp. 22–24.

- ^ "Timeline". December 6, 2017.

- ^ Leuchtenburg 2009, pp. 4–6.

- ^ Burner 1996, p. 16.

- ^ Revsine, David 'Dave' (November 30, 2006), "One-sided numbers dominate Saturday's rivalry games", ESPN, Go, retrieved November 30, 2006

- ^ Lane, Rose Wilder (1920). The Making of Herbert Hoover. New York: The Century Co. pp. 130–139. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

- ^ Irwin, Will (1928). Herbert Hoover: A Reminiscent Biography. Century Company. Retrieved September 15, 2024 – via archive.org.

- ^ Lockley, Fred (1928). "W. Foster Hidden (William Foster Hidden (1871–1963))". History of the Columbia River Valley from the Dalles to the Sea. S. J. Clarke Publishing Company. p. 498. Retrieved September 15, 2024 – via Google Books.

In 1891 he was among the first high school pupils to receive diplomas in Vancouver and next matriculated in Leland Stanford University, becoming a member of the class of 1895, with which Herbert Hoover was also identified. While a sophomore in that institution he helped to establish the Romero Hall Boarding Club, of which Mr. Hoover also became a member.

- ^ "Trail Breakers – Vol. 45, July 2018 to June 2019" (PDF). Retrieved October 29, 2024.

- ^ Whyte 2017, pp. 35–39.

- ^ a b c Leuchtenburg 2009, pp. 6–9.

- ^ Big Games: College Football's Greatest Rivalries – Page 222

- ^ Whyte 2017, pp. 39–41.

- ^ Whyte 2017, pp. 46–48.

- ^ Whyte 2017, pp. 48–50.

- ^ "Herbert Hoover, the graduate: Have Stanford degree, will travel". Hoover Institution. June 15, 2011. Retrieved January 24, 2013.

- ^ "What did the President do in Western Australia?", FAQ, Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum, archived from the original on January 18, 2012, retrieved January 18, 2012

- ^ Whyte 2017, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Whyte 2017, p. 56.

- ^ Nash 1983, p. 283.

- ^ Gwalia Historic Site, AU

- ^ "Hoover's Gold" (PDF). Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 2005. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ a b c Leuchtenburg 2009, pp. 10–13.

- ^ Burner 1996, p. 32.

- ^ Whyte 2017, pp. 70–71, 76.

- ^ Whyte 2017, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Burner 1996, p. 34.

- ^ Whyte 2017, pp. 77–81, 85–89.

- ^ Whyte 2017, pp. 88–93, 98, 102–104.

- ^ Whyte 2017, pp. 112–115.

- ^ Leuchtenburg 2009, pp. 11–13.

- ^ Nash 1983, p. 392.

- ^ Hoover, Herbert C. (1952). The Memoirs of Herbert Hoover Years of Adventure 1874–1920. London: Hollis & Carter. p. 99

- ^ Nash 1983, p. 569.

- ^ Whyte 2017, p. 115.

- ^ Burner 1996, pp. 24–43.

- ^ Blainey, Geoffrey (1963). The Rush That Never Ended. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press. pp. 265–268.

- ^ a b Hoover, Herbert C. (1952). The Memoirs of Herbert Hoover Years of Adventure 1874–1920. London: Hollis & Carter

- ^ Nash 1983, p. 381.