Nitrous oxide

Template:Chembox/Top

|-

| align="center" colspan="2" bgcolor="#ffffff" |

![]()

|-

Template:Chembox/SectGeneral

Template:Chembox/Formula

Template:Chembox/MolarMass

Template:Chembox/Appearance

Template:Chembox/CASNo

Template:Chembox/SectProperties

| Density and phase

| 1222.8 kg m-3 (liquid)

1.8 kg m-3 (gas STP)

|-

Template:Chembox/Solubility

Template:Chembox/MeltingPt

Template:Chembox/BoilingPt

Template:Chembox/SectStructure

Template:Chembox/MolecularShape

Template:Chembox/DipoleMoment

Template:Chembox/SectThermo

Template:Chembox/DeltaHf298

Template:Chembox/SectHazards

Template:Chembox/EUClass

| NFPA 704

|

| ||||

|- | R-phrases | Template:R8 |- | S-phrases | Template:S38 |- Template:Chembox/SectDataPage Template:Chembox/SectRelated Template:Chembox/RelatedX Template:Chembox/RelatedCpds Template:Chembox/Bottom

Nitrous oxide, dinitrogen oxide or dinitrogen monoxide, is a chemical compound with chemical formula N2O. Under room conditions, it is a colorless non-flammable gas, with a pleasant, slightly sweet odor and taste. It is used in surgery and dentistry for its anaesthetic and analgesic effects, where it is commonly known as "laughing gas" due to the euphoric effects of inhaling it.

History

The gas was first synthesized by English chemist and natural philosopher Joseph Priestley in 1775 [1], who called it phlogisticated nitrous air (see phlogiston). Priestley describes the preparation of "nitrous air diminished" by heating iron filings dampened with nitric acid in Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air, (1775). Priestley was delighted with his discovery: "I have now discovered an air five or six times as good as common air... nothing I ever did has surprised me more, or is more satisfactory." [1] Humphry Davy in the 1790s tested the gas on himself and some of his friends, including the poets Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Robert Southey. They soon realised that nitrous oxide considerably dulled the sensation of pain, even if the inhaler were still semi-conscious. And so it came into use as an anaesthetic, particularly by dentists, who do not typically have access to the services of an anesthesiologist and who may benefit from a patient who can respond to verbal commands.

Manufacture

N2O is commonly made by heating ammonium nitrate. This method was developed by the French chemist Claude Louis Berthollet in 1785 and has been widely used ever since. Unfortunately, the method poses a potential explosion risk from overheating ammonium nitrate.

- NH4NO3(aq) → N2O(g) + 2H2O(l), ΔH = −36.8 kJ

The addition of various phosphates favors formation of a purer gas. This reaction occurs between 170 - 240°C, temperatures where ammonium nitrate is a moderately sensitive explosive and a very powerful oxidizer (perhaps on the order of fuming nitric acid). At temperatures much above 240 °C the exothermic reaction may run away, perhaps up to the point of detonation. The mixture must be cooled to avoid such a disaster. In practice, the reaction involves a series of tedious adjustments to control the temperature to within a narrow range. Professionals have destroyed whole neighborhoods by losing control of such commercial processes. Examples include the Ohio Chemical debacle in Montreal, 1966 and the Air Products & Chemicals, Inc. disaster in Delaware City, Delaware, 1977.

The direct oxidation of ammonia may someday rival the ammonium nitrate pyrolysis synthesis of nitrous oxide mentioned above. This capital-intensive process, which originates in Japan, uses a manganese dioxide-bismuth oxide catalyst. (Suwa et al. 1961; Showa Denka Ltd.)

- 2NH3 + 2O2 → N2O + 3H2O

Higher oxides of nitrogen are formed as impurities. Note that uncatalyzed ammonia oxidation (i.e. combustion or explosion) goes primarily to N2 and H2O. The Ostwald process oxidizes ammonia to nitric oxide (NO), using platinum; this is the beginning of the modern synthesis of nitric acid from ammonia (see above).

Nitrous oxide can be made by heating a solution of sulfamic acid and nitric acid. A lot of gas was made this way in Bulgaria (Brozadzhiew & Rettos, 1975).

- HNO3 + NH2SO3H → N2O + H2SO4 + H2O

There is no explosive hazard in this reaction if the mixing rate is controlled. However, as usual, toxic higher oxides of nitrogen form.

Colorless solutions of hydroxylammonium chloride and sodium nitrite can also be used to produce N2O:

- NH3OH+Cl− + NaNO2 → N2O + NaCl + H2O

If the nitrite is added to the hydroxylamine solution, the gas produced is pure enough for inhalation, and the only remaining byproduct is salt water. However, if the hydroxylamine solution is added to the nitrite solution (nitrite is in excess), then toxic higher oxides of nitrogen are produced.

Uses

Inhalant effects

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Routes of administration | Inhalation |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | 0.004% |

| Elimination half-life | 5 minutes |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| E number | E942 (glazing agents, ...) |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.030.017 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | N2O |

| Molar mass | 44.0128 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

Nitrous oxide (N2O) is a dissociative drug that can cause analgesia, euphoria, dizziness, flanging of sound, and slight hallucinations.

In medicine

In the 1800s, nitrous oxide was used by dentists and surgeons for its mild analgesic properties. Today, nitrous oxide is used in dental procedures to provide inhalation sedation and reduce patient anxiety. In small doses in a medical or dental setting, nitrous oxide is very safe, because the nitrous oxide is mixed with a sufficient amount of oxygen using a regulator valve. However, extended, heavy use of inhaled nitrous oxide has been associated with Olney's Lesions in rats, though it is not necessarily possible to extrapolate it to humans.

Typically nitrous oxide is administered by dentists through a demand-valve inhaler over the nose that only releases gas when the patient inhales through the nose; full-face masks are not used by dentists, so that the patient's mouth can be worked on while the patient continues to inhale the gas.

Because nitrous oxide is minimally metabolized, it retains its potency when exhaled into the room by the patient and can pose an intoxicating and prolonged-exposure hazard to the clinic staff if the room is poorly ventilated. Where nitrous oxide is administered, a continuous-flow fresh-air ventilation system or nitrous-scavenging system is used, to prevent waste gas buildup.

Nitrous oxide is a weak general anesthetic, and so is generally not used alone in general anaesthesia. However, it has a very low short-term toxicity and is an excellent analgesic. In addition, its lower solubility in blood means it has a very rapid onset and offset, so a 50/50 mixture of nitrous oxide and oxygen ("gas and air", supplied under the trade name Entonox) is commonly used for pain relief during childbirth, for dental procedures, and in emergency medicine.

In general anesthesia it is used as a carrier gas in a 2:1 ratio with oxygen for more powerful general anaesthetic agents such as sevoflurane or desflurane. It has a MAC (Minimum Alveolar Concentration) of 105% and a blood:gas partition coefficient of 0.Α46. Less than 0.004% is metabolised in humans.

Recreational use

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2007) |

Since the earliest uses of nitrous oxide for medical or dental purposes, it has also been used recreationally, because it causes euphoria and slight hallucinations. Only a small number of recreational users (such as dental office workers or medical gas technicians) have legal access to pure nitrous oxide canisters that are intended for medical or dental use. Most recreational users obtain nitrous oxide from compressed gas containers which use nitrous oxide as a propellant for whipped cream or from automotive nitrous systems. Automotive nitrous available to the public often has 10% sulphuric compounds added to prevent recreational use. Inhalation of these compounds can be fatal.

Users typically inflate a balloon or plastic bag with nitrous oxide and inhale the gas for its effects. While nitrous oxide is not a dangerous substance per se, recreational users typically do not mix it with air or oxygen (as is standard procedure in a dentist's office) and thus may risk injury or death from lack of oxygen (anoxia). Nitrous oxide gas inhaled directly from a metal canister or tank, or through a connection to a homemade mask over a user's mouth, presents more potential danger due to two combined factors: its sedative effect which may leave a user overly relaxed; and such a system's automatic, continuous application which may prevent air (oxygen) from reaching the user, rendering them unconscious, and, after an extended period of time without oxygen, dead. Inhaling nitrous oxide in conjunction with an alkyl nitrite is in some circles referred to as "space surfing", as the nitrous oxide acts synergistically with the alkyl nitrite to create strong (but short-lived) euphoria, analgesia, dissociation, and in some cases, sensations of internal movement or agitation. The name also comes from the sound-flanging effects of nitrous oxide, which some users compare to the sound of waves crashing on a beach (hence "surfing"). While powerful, this is a potentially dangerous combination, as the CNS depressing effects of the nitrous oxide, combined with the drop in blood pressure (which is characteristic of nitrite inhalant use), may cause hypotension, unconsciousness, or, in the case of extreme overdose, death. Individuals with cardiac conditions, complications arising from stroke or surgery, or chronically low blood pressure are advised not to use these two drugs simultaneously.

Nitrous oxide is used as a whipping agent due to the ease at which it migrates into and out of oils; only a few seconds of rapid shaking is enough to migrate the gas into the oily cream under pressure. Due to this ability, nitrous also easily moves throughout the body, into and out of cells, because cell membranes are oil-based lipids. Prolonged inhalation of high concentrations of nitrous oxide will cause it to migrate throughout the body into sinus cavities, the digestive tract, and into fat cells. An inactive person who has breathed high concentrations for 20-30 minutes but then breathes normally will still retain the gas in their body at low doses as the gas slowly migrates back out of these internal cavities. Even after several hours of not breathing the gas, sudden rapid whole-body movements such as calisthenics causes the dissolved gas to suddenly begin migrating out of fat cells, resulting in a latent dosing effect.

Nitrous oxide can be habit-forming because of its short-lived effect (generally from 1 - 5 minutes in recreational doses) and ease of access. Death can result if it is inhaled in such a way that not enough oxygen is breathed in. While the pure gas is generally not toxic, long-term use in very large quantities has been associated with vitamin B12 deficiency, anemia due to reduced hemopoiesis, neuropathy, tinnitus, and numbness in extremities. Harmful irreversible effects that may be caused by abuse of nitrous oxide include peripheral neuropathies and limb spasms.[2] Pregnant women should not use nitrous oxide as chronic use is teratogenic and foetotoxic. One study in rats found that long term exposure to high doses of nitrous oxide may lead to Olney's lesions.[3] Seizures, perception of time, and vision-altering perceptions are possible side effects.

Aerosol propellant

The gas is approved for use as a food additive (also known as E942), specifically as an aerosol spray propellant. Its most common uses in this context are in aerosol whipped cream canisters, cooking sprays, and as an inert gas used to displace bacteria-inducing oxygen when filling packages of potato chips and other similar snack foods.

The gas is extremely soluble in fatty compounds. In aerosol whipped cream, it is dissolved in the fatty cream until it leaves the can, when it becomes gaseous and thus creates foam. Used in this way, it produces whipped cream four times the volume of the liquid, whereas whipping air into cream only produces twice the volume. If air were used as a propellant, under increased pressure the oxygen would accelerate rancidification of the butterfat, while nitrous oxide inhibits such degradation. However, the whipped cream produced with nitrous oxide is unstable, and will return to a more or less liquid state within half an hour to one hour. Thus, the method is not suitable for decorating food that will not be immediately served.

Similarly, cooking spray, which is made from various types of oils combined with lecithin (an emulsifier), may use nitrous oxide as a propellant; other propellants used in cooking spray include food-grade alcohol and propane.

Users of nitrous oxide often obtain it from whipped cream dispensers that use nitrous oxide as a propellant (see above section), for recreational use a as a euphoria-inducing inhalant drug. It is non-harmful in small doses, but risks due to lack of oxygen do exist (see section on "Recreational use" above).

Rocket motors

Nitrous oxide can be used as an oxidizer in a rocket engine. This has the advantages over other oxidizers that it is non-toxic and, due to its stability at room temperature, easy to store and relatively safe to carry on a flight.

Nitrous oxide has been the oxidizer of choice in several hybrid rocket designs (using solid fuel with a liquid or gaseous oxidizer). The combination of nitrous oxide with hydroxyl-terminated polybutadiene fuel has been used by SpaceShipOne and others. It is also notably used in amateur and high power rocketry with various plastics as the fuel. An episode of MythBusters featured a hybrid rocket built using a paraffin/powdered carbon mixture (and later salami) as its solid fuel and nitrous oxide as its oxidizer.

Nitrous oxide can also be used in a monopropellant rocket. In the presence of a heated catalyst, N2O will decompose exothermically into nitrogen and oxygen, at a temperature of approximately 1300 °C. In a vacuum thruster, this can provide a monopropellant specific impulse (Isp) of as much as 180s. While noticeably less than the Isp available from hydrazine thrusters (monopropellant or bipropellant with nitrogen tetroxide), the decreased toxicity makes nitrous oxide an option worth investigating.

Internal combustion engine

In vehicle racing, nitrous oxide (often referred to as just "nitrous" in this context to differ from the acronym NOS which is the brand Nitrous Oxide Systems) is sometimes injected into the intake manifold (or prior to the intake manifold; some systems directly inject right before the cylinder) to increase power. The gas itself is not flammable, but it delivers more oxygen than atmospheric air by breaking down at elevated temperatures, allowing the engine to burn more fuel and air, resulting in more powerful combustion. Nitrous oxide is stored as a compressed liquid; the evaporation and expansion of liquid nitrous oxide in the intake manifold causes a large drop in intake charge temperature, resulting in a denser charge, further allowing more air/fuel mixture to enter the cylinder. The lower temperature can also reduce detonation.

The same technique was used during World War II by Luftwaffe aircraft with the GM 1 system to boost the power output of aircraft engines. Originally meant to provide the Luftwaffe standard aircraft with superior high-altitude performance, technological considerations limited its use to extremely high altitudes. Accordingly, it was only used by specialized planes like high-altitude reconnaissance aircraft, high-speed bombers and high-altitude interceptors.

One of the major problems of using nitrous oxide in a reciprocating engine is that it can produce enough power to damage or destroy the engine. Very large power increases are possible, and if the mechanical structure of the engine is not properly reinforced, the engine may be severely damaged or destroyed during this kind of operation.

It is very important with nitrous oxide augmentation of internal combustion engines to maintain proper operating temperatures and fuel levels to prevent preignition, or detonation (sometimes referred to as knocking or pinging).

Neuropharmacology

Nitrous oxide shares many pharmacological similarities with other inhaled anesthetics, but there are a number of differences.

Nitrous oxide is relatively non-polar, has a low molecular weight, and high lipid solubility. As a result it can quickly diffuse into phospholipid cell membranes.

Like many classical anesthetics, the exact mechanism of action is still open to some conjecture. It antagonizes the NMDA receptor at partial pressures similar to those used in general anaesthesia. The evidence on the effect of N2O on GABA-A currents is mixed, but tends to show a lower potency potentiation.[4] N2O, like other volatile anesthetics, activates twin-pore potassium channels, albeit weakly. These channels are largely responsible for keeping neurons at the resting (unexcited) potential.[5] Unlike many anesthetics, however, N2O does not seem to affect calcium channels.[4]

Unlike most general anesthetics, N2O appears to affect the GABA receptor. In many behavioral tests of anxiety, a low dose of N2O is a successful anxiolytic. This anti-anxiety effect is partially reversed by benzodiazepine receptor antagonists. Mirroring this, animals which have developed tolerance to the anxiolytic effects of benzodiazepines are partially tolerant to nitrous oxide.[6] Indeed, in humans given 30% N2O, benzodiazepine receptor antagonists reduced the subjective reports of feeling “high”, but did not alter psycho-motor performance.[7]

The effects of N2O seem linked to the interaction between the endogenous opioid system and the descending noradrenergic system. When animals are given morphine chronically they develop tolerance to its analgesic (pain killing) effects; this also renders the animals tolerant to the analgesic effects of N2O[8]. Administration of antibodies which bind and block the activity of some endogenous opioids (not beta-endorphin), also block the antinociceptive effects of N2O.[9] Drugs which inhibit the breakdown of endogenous opioids also potentiate the antinociceptive effects of N2O.[9] Several experiments have shown that opioid receptor antagonists applied directly to the brain block the antinociceptive effects of N2O, but these drugs have no effect when injected into the spinal cord. Conversely, alpha-adrenoreceptor antagonists block the antinociceptive effects of N2O when given directly to the spinal cord, but not when applied directly to the brain.[10] Indeed, alpha2B-adrenoreceptor knockout mice or animals depleted in noradrenaline are nearly completely resistant to the antinociceptive effects of N2O.[11] It seems N2O-induced release of endogenous opioids causes disinhibition of brain stem noradrenergic neurons, which release norepinephrine into the spinal cord and inhibit pain signaling (Maze, M. and M. Fujinaga, 2000). Exactly how N2O causes the release of opioids is still uncertain.

Safety

The major safety hazards of nitrous oxide come from the fact that it is a compressed liquified gas, an asphyxiation risk, and a dissociative anaesthetic.

Chemical/physical

While normally inert in storage and fairly safe to handle, nitrous oxide can decompose energetically and potentially detonate if initiated under the wrong circumstances. Liquid nitrous oxide acts as a good solvent for many organic compounds; liquid mixtures can form somewhat sensitive explosives. Contamination with fuels has been implicated in a handful of rocketry accidents, where small quantities of nitrous / fuel mixtures detonated, triggering the explosive decomposition of residual nitrous oxide in plumbing.

Biological

Nitrous oxide inactivates the cobalamin form of vitamin B12 by oxidation. Symptoms of vitamin B12 deficiency, including sensory neuropathy, myelopathy, and encephalopathy, can occur within days or weeks of exposure to nitrous oxide anesthesia in people with subclinical vitamin B12 deficiency. Symptoms are treated with high doses of vitamin B12, but recovery can be slow and incomplete. People with normal vitamin B12 levels have sufficient vitamin B12 stores to make the effects of nitrous oxide insignificant, unless exposure is repeated and prolonged (nitrous oxide abuse). Vitamin B12 levels should be checked in people with risk factors for vitamin B12 deficiency prior to using nitrous oxide anesthesia.

Nitrous oxide has also been shown to induce early stages of Olney's lesions in the brains of rats.[3]

Thermal

Compressed nitrous oxide is usually stored at room temperature, but as the gas expands it quickly cools to sub-zero temperatures. A leak or unexpected release of compressed nitrous oxide can result in an immediate and severe burn.

Legality

In the United States, possession of nitrous oxide is legal under federal law and is not subject to DEA purview.[12] It is, however, regulated by the Food and Drug Administration under the Food Drug and Cosmetics Act; prosecution is possible under its "misbranding" clauses, prohibiting the sale or distribution of nitrous oxide for the purpose of human consumption. Many states have laws regulating the possession, sale, and distribution of nitrous oxide; but these are normally limited to either banning distribution to minors, or to setting an upper limit for the amount of nitrous oxide that may be sold without special license, rather than banning possession or distribution completely. In most jurisdictions, like at the federal level, sale or distribution for the purpose of human consumption is illegal.[12]

In the United Kingdom, recreational use of nitrous oxide is illegal, though sale and possession for non-inhalant use is legal for adults over the age of 18.[13] According to Times online, and certain other sources, laughing gas is legal in the UK.[14]

In New Zealand, the Ministry of Health has warned that nitrous oxide is a prescription medicine, and its sale or possession without a prescription is an offence under the Medicines Act.[15] This statement would seemingly prohibit all non-medicinal uses of the chemical, though it is inferred that only recreational use will be legally targeted.

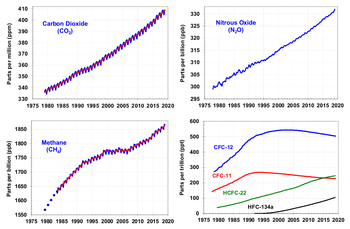

Nitrous oxide in the atmosphere

Unlike other nitrogen oxides, nitrous oxide is a major greenhouse gas. While its radiative warming effect is substantially less than CO2, nitrous oxide's persistence in the atmosphere, when considered over a 100 year period, per unit of weight, has 296 times more impact on global warming than that per mass unit of carbon dioxide (CO2) [2]. Control of nitrous oxide is part of efforts to curb greenhouse gas emissions, such as the Kyoto Protocol. Despite its relatively small concentration in the atmosphere, nitrous oxide is the third largest greenhouse gas contributor to overall global warming, behind carbon dioxide and methane. (The other nitrogen oxides contribute to global warming indirectly, by contributing to tropospheric ozone production during smog formation).

Nitrous oxide is emitted by bacteria in soils and oceans, and thus has been a part of Earth's atmosphere for eons. Agriculture is the main source of human-produced nitrous oxide: cultivating soil, the use of nitrogen fertilizers, and animal waste handling can all stimulate naturally occurring bacteria to produce more nitrous oxide. The livestock sector (primarily cows, chickens, and pigs) produces 65% of human-related nitrous oxide [3]. Industrial sources make up only about 20% of all anthropogenic sources, and include the production of nylon and nitric acid, and the burning of fossil fuel in internal combustion engines.

Human activity is thought to account for somewhat less than 2 teragrams (this is multiplied by about 300 when calculated as an equivalent amount of carbon dioxide) of nitrogen oxides per year, nature for over 15 teragrams [4]. The global anthropogenic nitrous oxide flux is about 1 petagram of carbon dioxide carbon-equivalents per year; this compares to 2 petagrams of methane carbon dioxide carbon-equivalents per year, and to an atmospheric loading rate of about 3.3 petagrams of carbon dioxide carbon-equivalents per year.

Nitrous oxide also attacks ozone in the stratosphere, aggravating the excess amount of UV light striking the earth's surface in recent decades, in a manner similar to various freons and related halogenated organics. Nitrous oxide is the main naturally-occurring regulator of stratospheric ozone.

References

- ^ J. R. Partington, A Short History of Chemistry, 3rd ed., Dover Publications, Inc., New York, New York, 1989, pp. 110-121.

- ^ National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2006). NIDA InfoFacts: Inhalants. Retrieved April 29, 2007, from http://www.drugabuse.gov/Infofacts/Inhalants.html

- ^ a b Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Beals J, Benshoff N, Olney J (2003). "Prolonged exposure to inhalational anesthetic nitrous oxide kills neurons in adult rat brain". Neuroscience. 122 (3): 609–16. PMID 14622904.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Mennerick, S., Jevtovic-Todorovic, V., Todorovic, S.M., Shen, W., Olney, J.W. & Zorumski, C.F. (1998). Effect of nitrous oxide on excitatory and inhibitory synaptic transmission in hippocampal cultures. J Neurosci, 18, 9716-26.

- ^ Gruss, M., Bushell, T.J., Bright, D.P., Lieb, W.R., Mathie, A. & Franks, N.P. (2004). Two-pore-domain K+ channels are a novel target for the anesthetic gases xenon, nitrous oxide, and cyclopropane. Mol Pharmacol, 65, 443-52.

- ^ Emmanouil, D.E., Johnson, C.H. & Quock, R.M. (1994). Nitrous oxide anxiolytic effect in mice in the elevated plus maze: mediation by benzodiazepine receptors. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 115, 167-72.

- ^ Zacny, J.P., Yajnik, S., Coalson, D., Lichtor, J.L., Apfelbaum, J.L., Rupani, G., Young, C., Thapar, P. & Klafta, J. (1995). Flumazenil may attenuate some subjective effects of nitrous oxide in humans: a preliminary report. Pharmacol Biochem Behav, 51, 815-9.

- ^ Berkowitz, B.A., Finck, A.D., Hynes, M.D. & Ngai, S.H. (1979). Tolerance to nitrous oxide analgesia in rats and mice. Anesthesiology, 51, 309-12.

- ^ a b Branda, E.M., Ramza, J.T., Cahill, F.J., Tseng, L.F. & Quock, R.M. (2000). Role of brain dynorphin in nitrous oxide antinociception in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav, 65, 217-21.

- ^ Guo, T.Z., Davies, M.F., Kingery, W.S., Patterson, A.J., Limbird, L.E. & Maze, M. (1999). Nitrous oxide produces antinociceptive response via alpha2B and/or alpha2C adrenoceptor subtypes in mice. Anesthesiology, 90, 470-6.

- ^ Sawamura, S., Kingery, W.S., Davies, M.F., Agashe, G.S., Clark, J.D., Koblika, B.K., Hashimoto, T. & Maze, M. (2000). Antinociceptive action of nitrous oxide is mediated by stimulation of noradrenergic neurons in the brainstem and activation of [alpha]2B adrenoceptors. J Neurosci, 20, 9242-51.

- ^ a b Center for Cognitive Liberty and Ethics: State Laws Concerning Inhalation of Nitrous Oxide

- ^ http://www.erowid.org/chemicals/nitrous/nitrous_law.shtml

- ^ http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/uk/article596797.ece

- ^ Beehive.govt.nz - Time's up for sham sales of laughing gas

External links

- Occupational Safety and Health Guideline for Nitrous Oxide

- Paul Crutzen Interview Freeview video of Paul Crutzen Nobel Laureate for his work on decomposition of ozone talking to Harry Kroto Nobel Laureate by the Vega Science Trust.

- National Pollutant Inventory - Oxide of nitrogen fact sheet

- Nitrous Oxide Specs Extremely thorough Nitrous Oxide Facts