Flunitrazepam

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌfluːnɪˈtræzɪpæm/ |

| Trade names | Rohypnol |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Dependence liability | Very high |

| Routes of administration | By mouth (tablets) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

Sweden schedule II |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 64–77% (by mouth) 50% (suppository) |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 18–26 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.015.089 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

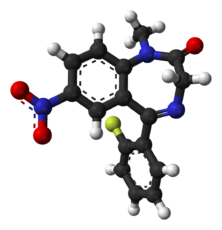

| Formula | C16H12FN3O3 |

| Molar mass | 313.3 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Flunitrazepam, also known as Rohypnol among other names,[1] is an intermediate acting benzodiazepine used in some countries to treat severe insomnia and in fewer, early in anesthesia.[2]

Just as with other hypnotics, flunitrazepam should be strictly used only on a short-term basis or by those with chronic insomnia on an occasional basis.[2] Flunitrazepam has been referred to as a date rape drug, though the percentage of reported rape cases in which it is reported to be involved is few.[3]

Use

In countries where the drug is used, it is used for treatment of sleeping problems, and in some countries to begin anesthesia.[2][4] These were also the uses for which it was originally studied.[5]

Adverse effects

Adverse effects of flunitrazepam include dependence, both physical and psychological; reduced sleep quality resulting in somnolence; and overdose, resulting in excessive sedation, impairment of balance and speech, respiratory depression or coma, and possibly death. Because of the latter, flunitrazepam is commonly used in suicide. When used in pregnancy, it might cause hypotonia.

Dependence

Flunitrazepam as with other benzodiazepines can lead to drug dependence and benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome.[6] Discontinuation may result in the appearance of withdrawal symptoms when the drug is discontinued. Abrupt withdrawal may lead to a benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome characterised by seizures, psychosis, insomnia, and anxiety. Rebound insomnia, worse than baseline insomnia, typically occurs after discontinuation of flunitrazepam even after short-term single nightly dose therapy.[7]

Sleep depth

This section needs more reliable medical references for verification or relies too heavily on primary sources. (October 2017) |  |

Flunitrazepam produces a decrease in delta wave activity. The effect of benzodiazepine drugs on delta waves, however, may not be mediated via benzodiazepine receptors. Delta activity is an indicator of depth of sleep within non-REM sleep; increased levels of delta sleep reflects better quality of sleep. Thus, flunitrazepam and other benzodiazepines[citation needed] cause a deterioration in sleep quality. Cyproheptadine may be superior[citation needed] to benzodiazepines in the treatment of insomnia as it enhances sleep quality based on EEG studies.

Paradoxical effects

Flunitrazepam may cause a paradoxical reaction in some individuals causing symptoms including anxiety, aggressiveness, agitation, confusion, disinhibition, loss of impulse control, talkativeness, violent behavior, and even convulsions. Paradoxical adverse effects may even lead to criminal behaviour.[8]

Hypotonia

Benzodiazepines such as flunitrazepam are lipophilic and rapidly penetrate membranes and, therefore, rapidly cross over into the placenta with significant uptake of the drug. Use of benzodiazepines including flunitrazepam in late pregnancy, especially high doses, may result in hypotonia, also known as floppy baby syndrome.[9]

Other

Flunitrazepam impairs cognitive functions. This may appear as lack of concentration, confusion and anterograde amnesia. It can be described as a hangover-like effect which can persist to the next day.[10] It also impairs psychomotor functions similar to other benzodiazepines and nonbenzodiazepine hypnotic drugs; falls and hip fractures were frequently reported. The combination with alcohol increases these impairments. Partial, but incomplete tolerance develops to these impairments.[11]

Other adverse effects include:

- Slurred speech

- Gastrointestinal disturbances, lasting 12 or more hours

- Vomiting

- Respiratory depression in higher doses

- Special precautions

Benzodiazepines require special precaution if used in the elderly, during pregnancy, in children, in alcohol- or drug-dependent individuals, and in individuals with comorbid psychiatric disorders.[12]

Impairment of driving skills with a resultant increased risk of road traffic accidents is probably the most important adverse effect. This side-effect is not unique to flunitrazepam but also occurs with other hypnotic drugs. Flunitrazepam seems to have a particularly high risk of road traffic accidents compared to other hypnotic drugs. Extreme caution should be exercised by drivers after taking flunitrazepam.[13][14]

Interactions

The use of flunitrazepam in combination with alcoholic beverages synergizes the adverse effects, and can lead to toxicity and death.[3]

Overdose

Flunitrazepam is a drug that is frequently involved in drug intoxication, including overdose.[15][16] Overdose of flunitrazepam may result in excessive sedation, or impairment of balance or speech. This may progress in severe overdoses to respiratory depression or coma and possibly death. The risk of overdose is increased if flunitrazepam is taken in combination with CNS depressants such as ethanol (alcohol) and opioids. Flunitrazepam overdose responds to the benzodiazepine receptor antagonist flumazenil, which thus can be used as a treatment.

Detection

As of 2016, blood tests can identify flunitrazepam at concentrations of as low as 4 ng/ml; the elimination half life of the drug is 11–25 hours. For urine samples, metabolites can be identified 60 hours to 28 days, depending on the dose and analytical method used. Hair and saliva can also be analyzed; hair is useful when a long time has transpired since ingestion, and saliva for workplace drug tests.[17]

Flunitrazepam can be measured in blood or plasma to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized patients, provide evidence in an impaired driving arrest, or assist in a medicolegal death investigation. Blood or plasma flunitrazepam concentrations are usually in a range of 5–20 μg/L in persons receiving the drug therapeutically as a nighttime hypnotic, 10–50 μg/L in those arrested for impaired driving and 100–1000 μg/L in victims of acute fatal overdosage. Urine is often the preferred specimen for routine drug abuse monitoring purposes. The presence of 7-aminoflunitrazepam, a pharmacologically-active metabolite and in vitro degradation product, is useful for confirmation of flunitrazepam ingestion. In postmortem specimens, the parent drug may have been entirely degraded over time to 7-aminoflunitrazepam.[18][19][20] Other metabolites include desmethylflunitrazepam and 3-hydroxydesmethylflunitrazepam.

Pharmacology

The main pharmacological effects of flunitrazepam are the enhancement of GABA at various GABA receptors.[3]

While 80% of flunitrazepam that is taken orally is absorbed, bioavailability in suppository form is closer to 50%.[21]

Flunitrazepam has a long half-life of 18–26 hours, which means that flunitrazepam's effects after nighttime administration persist throughout the next day.[10]

Flunitrazepam is lipophilic and is metabolised hepatically via oxidative pathways. The enzyme CYP3A4 is the main enzyme in its phase 1 metabolism in human liver microsomes.[22]

Chemistry

Flunitrazepam is classed as a nitro-benzodiazepine. It is the fluorinated N-methyl derivative of nitrazepam. Other nitro-benzodiazepines include nitrazepam (the parent compound), nimetazepam (methylamino derivative) and clonazepam (2ʹ-chlorinated derivative).[23]

History

Flunitrazepam was discovered at Roche as part of the benzodiazepine work led by Leo Sternbach; the patent application was filed in 1962 and it was first marketed in 1974.[24][25]

Due to abuse of the drug for date rape and recreation, in 1998 Roche modified the formulation to give lower doses, make it less soluble, and add a blue dye for easier detection in drinks.[17] It was never marketed in the US, and by 2016 had been withdrawn from the markets in Spain, France, Germany, and the UK.[17]

Society and culture

Recreational and illegal uses

Recreational use

A 1989 journal on Clinical Pharmacology reports that benzodiazepines accounted for 52% of prescription forgeries, suggesting that benzodiazepines was a major prescription drug class of abuse. Nitrazepam accounted for 13% of forged prescriptions.[26]

Flunitrazepam and other sedative hypnotic drugs are detected frequently in cases of people suspected of driving under the influence of drugs. Other benzodiazepines and nonbenzodiazepines (anxiolytic or hypnotic) such as zolpidem and zopiclone (as well as cyclopyrrolones, imidazopyridines, and pyrazolopyrimidines) are also found in high numbers of suspected drugged drivers. Many drivers have blood levels far exceeding the therapeutic dose range suggesting a high degree of abuse potential for benzodiazepines and similar drugs.[27]

Suicide

In studies in Sweden, flunitrazepam was the second most common drug used in suicides, being found in about 16% of cases.[28] In a retrospective Swedish study of 1587 deaths, in 159 cases benzodiazepines were found. In suicides when benzodiazepines were implicated, the benzodiazepines flunitrazepam and nitrazepam were occurring in significantly higher concentrations, compared to natural deaths. In 4 of the 159 cases, where benzodiazepines were found, benzodiazepines alone were the only cause of death. It was concluded that flunitrazepam and nitrazepam might be more toxic than other benzodiazepines.[29][30]

Drug-facilitated sexual assault

Flunitrazepam is known to induce anterograde amnesia in sufficient doses; individuals are unable to remember certain events that they experienced while under the influence of the drug, which complicates investigations.[31][32] This effect could be particularly dangerous if flunitrazepam is used to aid in the commission of sexual assault; victims may be unable to clearly recall the assault, the assailant, or the events surrounding the assault.[17]

While use of flunitrazepam in sexual assault has been prominent in the media, as of 2015 appears to be fairly rare, and use of alcohol and other benzodiazepine drugs in date rape appears to be a larger but underreported problem.[3]

Drug-facilitated robbery

In the United Kingdom, the use of flunitrazepam and other "date rape" drugs have also been connected to stealing from sedated victims. An activist quoted by a British newspaper estimated that up to 2,000 individuals are robbed each year after being spiked with powerful sedatives,[33] making drug-assisted robbery a more commonly reported problem than drug-assisted rape.

Regional use

Flunitrazepam is a Schedule III drug under the international Convention on Psychotropic Substances of 1971.[34]

- In Australia, as of 2013 the drug was authorized for prescribing for severe cases of insomnia but was restricted as a Schedule 8 medicine.[2][35]

- In France, as of 2016 flunitrazepam was not marketed.[17]

- In Germany, as of 2016 flunitrazepam is an Anlage III Betäubungsmittel (controlled substance which is allowed to be marketed and prescribed by physicians under specific provisions) and is available on a special narcotic drug prescription as the Rohypnol 1 mg film-coated tablets and several generic preparations (November 2016).[36]

- In Ireland, flunitrazepam is a Schedule 3 controlled substance with strict restrictions.[37]

- In Japan, flunitrazepam is marketed by Japanese pharmaceutical company Chugai under the tradename Rohypnol and is indicated for the treatment of insomnia as well as used for preanesthetic medication.[4]

- In Mexico, Rohypnol is approved for medical use.[citation needed]

- In Norway, on January 1, 2003, flunitrazepam was moved up one level in the schedule of controlled drugs and, on August 1, 2004, the manufacturer Roche removed Rohypnol from the market there altogether.[38]

- In South Africa, Rohypnol is classified as a schedule 6 drug.[39] It is available by prescription only, and restricted to 1 mg doses. Travelers from South Africa to the United States are limited to a 30-day supply. The drug must be declared to US Customs upon arrival. If a valid prescription cannot be produced, the drug may be subject to Customs search and seizure, and the traveler may face criminal charges or deportation.

- In Sweden, flunitrazepam is available from Mylan.[40] It is listed as a List II (Schedule II) under the Narcotics Control Act (1968).[citation needed]

- In the United Kingdom, flunitrazepam is not licensed for medical use[14][17] and is a controlled drug under Schedule 3 and Class C[41]

- In the United States, the drug has not been approved by the Food and Drug Administration and is considered to be an illegal drug; as of 2016 it is Schedule IV.[17][42] 21 U.S.C. § 841 and 21 U.S.C. § 952 provide for punishment for the importation and distribution of up to 20 years in prison and a fine; possession is punishable by three years and a fine.[6]

Names

Flunitrazepam is marketed under many brand names in the countries where it is legal.[1] It also has many street names, including "roofie" and "ruffie".[6]

References

- ^ a b Drugs.com International brands for Flunitrazepam Page accessed April 13, 2016

- ^ a b c d "Prescribing of Benzodiazepines Alprazolam and Flunitrazepam" (PDF). Pharmaceutical Services Branch. New South Wales Health. November 2013.

- ^ a b c d European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction Benzodiazepines drug profile. Page last updated January 8, 2015

- ^ a b "Kusuri-no-Shiori Drug Information Sheet". RAD-AR Council, Japan. October 2015. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

- ^ Mattila, MA; Larni, HM (November 1980). "Flunitrazepam: a review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic use". Drugs. 20 (5): 353–74. PMID 6108205.

- ^ a b c Center for Substance Abuse Research at the University of Maryland Flunitrazepam (Rohypnol) Last Updated on Tuesday, October 29, 2013

- ^ Kales A; Scharf MB; Kales JD; Soldatos CR (April 20, 1979). "Rebound insomnia. A potential hazard following withdrawal of certain benzodiazepines". Journal of the American Medical Association. 241 (16): 1692–5. doi:10.1001/jama.241.16.1692. PMID 430730.

- ^ Bramness JG, Skurtveit S, Mørland J (June 2006). "Flunitrazepam: psychomotor impairment, agitation and paradoxical reactions". Forensic Science International. 159 (2–3): 83–91. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2005.06.009. PMID 16087304.

- ^ Kanto JH (May 1982). "Use of benzodiazepines during pregnancy, labour and lactation, with particular reference to pharmacokinetic considerations". Drugs. 23 (5): 354–80. doi:10.2165/00003495-198223050-00002. PMID 6124415.

- ^ a b Vermeeren A. (2004). "Residual effects of hypnotics: epidemiology and clinical implications". CNS Drugs. 18 (5): 297–328. doi:10.2165/00023210-200418050-00003. PMID 15089115.

- ^ Mets, MA.; Volkerts, ER.; Olivier, B.; Verster, JC. (February 2010). "Effect of hypnotic drugs on body balance and standing steadiness". Sleep Medicine Reviews. 14 (4): 259–67. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2009.10.008. PMID 20171127.

- ^ Authier, N.; Balayssac, D.; Sautereau, M.; Zangarelli, A.; Courty, P.; Somogyi, AA.; Vennat, B.; Llorca, PM.; Eschalier, A. (November 2009). "Benzodiazepine dependence: focus on withdrawal syndrome". Annales Pharmaceutiques Françaises. 67 (6): 408–13. doi:10.1016/j.pharma.2009.07.001. PMID 19900604.

- ^ Gustavsen I, Bramness JG, Skurtveit S, Engeland A, Neutel I, Mørland J (December 2008). "Road traffic accident risk related to prescriptions of the hypnotics zopiclone, zolpidem, flunitrazepam and nitrazepam". Sleep Medicine. 9 (8): 818–22. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2007.11.011. PMID 18226959.

- ^ a b UK Dept. of Transport. July 2014. Guidance for healthcare professionals on drug driving

- ^ Zevzikovas, A; Kiliuviene G; Ivanauskas L; Dirse V. (2002). "Analysis of benzodiazepine derivative mixture by gas-liquid chromatography". Medicina (Kaunas). 38 (3): 316–20. PMID 12474705.

- ^ Jonasson B, Saldeen T (March 2002). "Citalopram in fatal poisoning cases". Forensic Science International. 126 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1016/S0379-0738(01)00632-6. PMID 11955823.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kiss, B et al. Assays for Flunitrazepam. Chapter 48 in Neuropathology of Drug Addictions and Substance Misuse Volume 2: Stimulants, Club and Dissociative Drugs, Hallucinogens, Steroids, Inhalants and International Aspects. Editor, Victor R. Preedy. Academic Press, 2016 ISBN 9780128003756 Page 513ff

- ^ Jones AW, Holmgren A, Kugelberg FC. Concentrations of scheduled prescription drugs in blood of impaired drivers: considerations for interpreting the results. Ther. Drug Monit. 29: 248–260, 2007.

- ^ Robertson MD, Drummer OH. Stability of nitrobenzodiazepines in postmortem blood. J. For. Sci. 43: 5–8, 1998.

- ^ R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2008, pp. 633–635.

- ^ Cano J. P.; Soliva, M.; Hartmann, D.; Ziegler, W. H.; Amrein, R. (1977). "Bioavailability from various galenic formulations of flunitrazepam". Arzneimittelforschung. 27 (12): 2383–8. PMID 23801. rohypnol.

- ^ Hesse LM, Venkatakrishnan K, von Moltke LL, Shader RI, Greenblatt DJ (February 1, 2001). "CYP3A4 Is the Major CYP Isoform Mediating the in Vitro Hydroxylation and Demethylation of Flunitrazepam". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 29 (2): 133–40. PMID 11159802.

- ^ Robertson MD; Drummer OH (May 1995). "Postmortem drug metabolism by bacteria". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 40 (3): 382–6. PMID 7782744.

- ^ Erika M Alapi and Janos Fischer. Table of Selected Analogue Classes. Part III of Analogue-based Drug Discovery Eds Janos Fischer, C. Robin Ganellin. John Wiley & Sons, 2006 ISBN 9783527607495 Pg 537 which refers to US patent 3,116,203 Oleaginous systems

- ^ Jenny Bryan for The Pharmaceutical Journal. Sept 18 2009 Landmark drugs: The discovery of benzodiazepines and the adverse publicity that followed

- ^ Bergman U; Dahl-Puustinen ML. (1989). "Use of prescription forgeries in a drug abuse surveillance network". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 36 (6): 621–3. doi:10.1007/BF00637747. PMID 2776820.

- ^ Jones AW; Holmgren A; Kugelberg FC. (April 2007). "Concentrations of scheduled prescription drugs in blood of impaired drivers: considerations for interpreting the results". Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. 29 (2): 248–60. doi:10.1097/FTD.0b013e31803d3c04. PMID 17417081.

- ^ Jonasson B, Jonasson U, Saldeen T (January 2000). "Among fatal poisonings dextropropoxyphene predominates in younger people, antidepressants in the middle aged and sedatives in the elderly". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 45 (1): 7–10. PMID 10641912.

- ^ Ericsson HR, Holmgren P, Jakobsson SW, Lafolie P, De Rees B (November 10, 1993). "Benzodiazepine findings in autopsy material. A study shows interacting factors in fatal cases". Läkartidningen. 90 (45): 3954–7. PMID 8231567.

- ^ Drummer OH, Syrjanen ML, Cordner SM (September 1993). "Deaths involving the benzodiazepine flunitrazepam". The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology. 14 (3): 238–243. doi:10.1097/00000433-199309000-00012. PMID 8311057.

- ^ "Bankrånare stärkte sig med Rohypnol?". DrugNews.

- ^ "Mijailovic var påverkad av våldsdrog". Expressen.

- ^ Thompson, Tony (December 19, 2004). "'Rape drug' used to rob thousands". The Guardian. London. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- ^ International Narcotics Control Board List of Psychotropic Substances under International Control Green List 26th edition, 2015

- ^ "Authorisation to Supply or Prescribe Drugs of Addiction: Flunitrazepam". Statutory Medical Notifications. Department of Health, Government of Western Australia. August 13, 2004. Archived from the original on August 28, 2006. Retrieved March 13, 2006.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Irish Statute Book, Statutory Instruments, S.I. No. 342/1993 — Misuse of Drugs (Amendment) Regulations, 1993

- ^ Bramness JG; Skurtveit S; Furu K; Engeland A; Sakshaug S; Rønning M. (February 23, 2006). "[Changes in the sale and use of flunitrazepam in Norway after 1999]". Tidsskr nor Laegeforen. 126 (5): 589–90. PMID 16505866.

- ^ "Drug Wars – About Drugs". October 11, 2006.

- ^ http://www.fass.se/LIF/produktfakta/substance_products.jsp?substanceId=IDE4POCOU9OKGVERT1

- ^ List of most commonly encountered drugs currently controlled under the misuse of drugs legislation Published 26 May 2016

- ^ DEA [Lists of Scheduling Actions Controlled Substances Regulated Chemicals May 2016]