Varenicline: Difference between revisions

Newer (2014) review paper to verify MOA/impact on mesolimbic dopaminergic system. |

Newer Cochrane review says otherwise-updated |

||

| Line 69: | Line 69: | ||

Varenicline is indicated for [[smoking cessation]]. In a 2006 [[randomized controlled trial]] sponsored by Pfizer, after one year the rate of continuous abstinence was 10% for placebo, 15% for [[bupropion]] and 23% for varenicline.<ref name="Jorenby2006">{{cite journal | author=Jorenby DE, Hays JT, Rigotti NA, Azoulay S, Watsky EJ, Williams KE, Billing CB, Gong J, Reeves KR| title=Efficacy of varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs placebo or sustained-release bupropion for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial | journal=JAMA | volume=296 | issue=1 | pages=56–63 | year=2006 | pmid=16820547 | doi=10.1001/jama.296.1.56 | url=http://jama.ama-assn.org/content/296/1/56.full}}</ref> In a 2009 [[meta-analysis]] of 101 studies funded by Pfizer, varenicline was found to be more effective than bupropion ([[odds ratio]] 1.40) and NRTs (odds ratio 1.56).<ref name="Mills2009">{{Cite journal |author = Mills EJ, Wu P, Spurden D, Ebbert JO, Wilson K | title = Efficacy of pharmacotherapies for short-term smoking abstinance: a systematic review and meta-analysis | journal = Harm Reduct J | volume = 6 | pages = 25 | year = 2009 | doi = 10.1186/1477-7517-6-25 | pmid = 19761618 | url= http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/pdf/1477-7517-6-25.pdf | pmc=2760513}}</ref> |

Varenicline is indicated for [[smoking cessation]]. In a 2006 [[randomized controlled trial]] sponsored by Pfizer, after one year the rate of continuous abstinence was 10% for placebo, 15% for [[bupropion]] and 23% for varenicline.<ref name="Jorenby2006">{{cite journal | author=Jorenby DE, Hays JT, Rigotti NA, Azoulay S, Watsky EJ, Williams KE, Billing CB, Gong J, Reeves KR| title=Efficacy of varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs placebo or sustained-release bupropion for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial | journal=JAMA | volume=296 | issue=1 | pages=56–63 | year=2006 | pmid=16820547 | doi=10.1001/jama.296.1.56 | url=http://jama.ama-assn.org/content/296/1/56.full}}</ref> In a 2009 [[meta-analysis]] of 101 studies funded by Pfizer, varenicline was found to be more effective than bupropion ([[odds ratio]] 1.40) and NRTs (odds ratio 1.56).<ref name="Mills2009">{{Cite journal |author = Mills EJ, Wu P, Spurden D, Ebbert JO, Wilson K | title = Efficacy of pharmacotherapies for short-term smoking abstinance: a systematic review and meta-analysis | journal = Harm Reduct J | volume = 6 | pages = 25 | year = 2009 | doi = 10.1186/1477-7517-6-25 | pmid = 19761618 | url= http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/pdf/1477-7517-6-25.pdf | pmc=2760513}}</ref> |

||

A 2013 Cochrane overview and network [[meta-analysis]] of 12 reviews concluded that varenicline is the most effective pharmacologic treatment and that smokers were nearly three times more likely to quit on varenicline than with placebo treatment. Varenicline was more efficacious than bupropion and than NRT and is as effective as NRT for tobacco smoking cessation.<ref name="Cochrane2013">{{cite journal| author=Cahill K, Stevens S, Perera R, Lancaster T|title=Pharmacological interventions for smoking cessation: an overview and network meta-analysis|journal=Cochrane Database Syst Rev| volume=5| issue=| pages=CD009329|date=May 2013|pmid=23728690|doi=10.1002/14651858.CD009329.pub2}}</ref> |

|||

A Cochrane systematic review concluded that varenicline improved the likelihood of successfully quitting smoking by two- to three-fold relative to pharmacologically unassisted attempts. Varenicline was more efficacious than bupropion in this regard but not statistically superior to NRT.<ref name="Cochrane |

|||

">{{cite journal |

|||

| author=Cahill K, Stead LF, Lancaster T |

|||

| title=Nicotine receptor partial agonists for smoking cessation |

|||

| journal=Cochrane Database Syst Rev |

|||

| volume=4 |

|||

| issue= |

|||

| pages=CD006103 |

|||

| year=2012 |

|||

| pmid=22513936 |

|||

| doi=10.1002/14651858.CD006103.pub6 |

|||

| editor1-last=Cahill |

|||

| editor1-first=Kate |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

The United States [[Food and Drug Administration]] (US FDA) has approved the use of varenicline for up to twelve weeks. If smoking cessation has been achieved it may be continued for another twelve weeks.<ref name=FDA2006/> |

The United States [[Food and Drug Administration]] (US FDA) has approved the use of varenicline for up to twelve weeks. If smoking cessation has been achieved it may be continued for another twelve weeks.<ref name=FDA2006/> |

||

Revision as of 02:11, 7 November 2015

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Chantix |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a606024 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | <20% |

| Metabolism | Limited (<10%) |

| Elimination half-life | 24 hours |

| Excretion | Renal (81–92%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

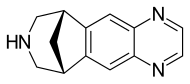

| Formula | C13H13N3 |

| Molar mass | 211.267 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Varenicline (trade name Chantix in the USA and Champix in Canada, Europe and other countries, marketed by Pfizer, usually in the form of varenicline tartrate), is a prescription medication used to treat nicotine addiction. Varenicline is a nicotinic receptor partial agonist—it stimulates nicotine receptors more weakly than nicotine itself does. In this respect it is similar to cytisine and different from the nicotinic antagonist, bupropion, and nicotine replacement therapies (NRTs) like nicotine patches and nicotine gum. As a partial agonist it both reduces cravings for and decreases the pleasurable effects of cigarettes and other tobacco products. Through these mechanisms it can assist some patients to quit smoking.

Medical uses

Varenicline is indicated for smoking cessation. In a 2006 randomized controlled trial sponsored by Pfizer, after one year the rate of continuous abstinence was 10% for placebo, 15% for bupropion and 23% for varenicline.[1] In a 2009 meta-analysis of 101 studies funded by Pfizer, varenicline was found to be more effective than bupropion (odds ratio 1.40) and NRTs (odds ratio 1.56).[2]

A 2013 Cochrane overview and network meta-analysis of 12 reviews concluded that varenicline is the most effective pharmacologic treatment and that smokers were nearly three times more likely to quit on varenicline than with placebo treatment. Varenicline was more efficacious than bupropion and than NRT and is as effective as NRT for tobacco smoking cessation.[3]

The United States Food and Drug Administration (US FDA) has approved the use of varenicline for up to twelve weeks. If smoking cessation has been achieved it may be continued for another twelve weeks.[4]

Varenicline has not been tested in those under 18 years old or pregnant women and therefore is not recommended for use by these groups. Varenicline is considered a class C pregnancy drug, as animal studies have shown no increased risk of congenital anomalies, however, no data from human studies is available.[5] An observational study is currently being conducted assessing for malformations related to varenicline exposure, but has no results yet.[6] An alternate drug is preferred for smoking cessation during breastfeeding due to lack of information and based on the animal studies on nicotine.[7]

Adverse effects

Nausea occurs commonly in people taking varenicline. Other less common side effects include headache, difficulty sleeping, and abnormal dreams. Rare side effects reported by people taking varenicline compared to placebo include change in taste, vomiting, abdominal pain, flatulence, and constipation. In a recent meta-analysis paper by Leung et al., it has been estimated that for every five subjects taking varenicline at maintenance doses, there will be an event of nausea, and for every 24 and 35 treated subjects, there will be an event of constipation and flatulence respectively. Gastrointestinal side-effects lead to discontinuation of the drug in 2% to 8% of people using varenicline.[8][9] Incidence of nausea is dose-dependent: incidence of nausea was higher in people taking a larger dose (30%) versus placebo (10%) as compared to people taking a smaller dose (16%) versus placebo (11%).[10]

Depression and suicide

In November 2007, the US FDA announced it had received post-marketing reports of thoughts of suicide and occasional suicidal behavior, erratic behavior, and drowsiness among people using varenicline for smoking cessation. Since July 1, 2009, the US FDA has required varenicline to carry a black box warning that the drug should be stopped if any of these symptoms are experienced.[11] The label notes, however, that a pooled analysis of 18 randomized clinical trials including 8,521 people found similar rates of psychiatric events in the treatment and placebo arms, and that similar results have been obtained in four observational studies including 10,000 to 30,000 varenicline users.[12] People are advised to weigh the risks of using varenicline against the benefits of its use, noting that varenicline "has been demonstrated to increase the likelihood of abstinence from smoking for as long as one year compared to treatment with placebo." and that "the health benefits of quitting smoking are immediate and substantial."[12]

A 2014 systematic review did not find evidence of an increased suicide risk.[13] However, a literature review concluded that varenicline could worsen psychiatric symptoms in people with depression.[14][15]

Cardiovascular disease

In June 2011, the US FDA issued a safety announcement that varenicline may be associated with "a small, increased risk of certain cardiovascular adverse events in people who have cardiovascular disease."[16] A 2014 review, however, did not support these concerns.[17]

A prior 2011 review had found increased risk of cardiovascular events compared with placebo.[18] Expert commentary in the same journal raised doubts about the methodology of the review,[19][20] concerns which were echoed by the European Medicines Agency.[21] Of specific concern were "the low number of events seen, the types of events counted, the higher drop-out rate in people receiving placebo, the lack of information on the timing of events, and the exclusion of studies in which no-one had an event." In contrast, a 2012 meta analysis which focused on events occurring during drug exposure or within 30 days after discontinuation found no increase in cardiovascular serious adverse events associated with varenicline use.[22]

Mechanism of action

Varenicline displays full agonism on α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors.[23][24] And it is a partial agonist on the α4β2, α3β4, and α6β2 subtypes.[25] In addition, it's a weak agonist on the α3β2 containing receptors.

Varenicline's partial agonism on the α4β2 receptors rather than nicotine's full agonism produces less effect of dopamine release than nicotine's. This α4β2 competitive binding, reduces the ability of nicotine to bind and stimulate the mesolimbic dopamine system - similar to the method of action of buprenorphine in the treatment of opioid addiction.[26]

Pharmacokinetics

Most of the active compound is excreted renally (92–93%). A small proportion is glucuronidated, oxidated, N-formylated or conjugated to a hexose.[27] The elimination half-life is about 24 hours.

History

Use of Cytisus plant as a smoking substitute during World War II[28] led to use as a cessation aid in eastern Europe and extraction of cytisine.[29] Cytisine analogs led to varenicline at Pfizer.[30][31][32]

Varenicline received a "priority review" by the US FDA in February 2006, shortening the usual 10-month review period to 6 months because of its demonstrated effectiveness in clinical trials and perceived lack of safety issues.[33] The agency's approval of the drug came on May 11, 2006.[4] On August 1, 2006, varenicline was made available for sale in the United States and on September 29, 2006, was approved for sale in the European Union.[34]

See also

References

- ^ Jorenby DE, Hays JT, Rigotti NA, Azoulay S, Watsky EJ, Williams KE, Billing CB, Gong J, Reeves KR (2006). "Efficacy of varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs placebo or sustained-release bupropion for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial". JAMA. 296 (1): 56–63. doi:10.1001/jama.296.1.56. PMID 16820547.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mills EJ, Wu P, Spurden D, Ebbert JO, Wilson K (2009). "Efficacy of pharmacotherapies for short-term smoking abstinance: a systematic review and meta-analysis" (PDF). Harm Reduct J. 6: 25. doi:10.1186/1477-7517-6-25. PMC 2760513. PMID 19761618.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Cahill K, Stevens S, Perera R, Lancaster T (May 2013). "Pharmacological interventions for smoking cessation: an overview and network meta-analysis". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 5: CD009329. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009329.pub2. PMID 23728690.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b U.S. Food and Drug Administration.FDA Approves Novel Medication for Smoking Cessation. Press release, 11 May 2006.

- ^ Cressman, AM; Pupco, A; Kim, E; Koren, G; Bozzo, P (May 2012). "Smoking cessation therapy during pregnancy". Canadian family physician Medecin de famille canadien. 58 (5): 525–7. PMC 3352787. PMID 22586193.

- ^ http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/study/NCT01290445

- ^ http://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/cgi-bin/sis/htmlgen?LACT

- ^ Leung, LK; Patafio, FM; Rosser, WW (September 28, 2011). "Gastrointestinal adverse effects of varenicline at maintenance dose: a meta-analysis". BMC clinical pharmacology. 11 (1): 15. doi:10.1186/1472-6904-11-15. PMC 3192741. PMID 21955317.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ American Cancer Society. "Cancer Drug Guide: Varenicline". Retrieved 2008-01-19.

- ^ http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/lookup.cfm?setid=d52bc40b-db7b-4243-888c-9ee95bbc6545

- ^ FDA. "Public Health Advisory: FDA Requires New Boxed Warnings for the Smoking Cessation Drugs Chantix and Zyban". Retrieved 2009-07-01.

- ^ a b "www.accessdata.fda.gov" (PDF).

- ^ Hughes, JR (8 January 2015). "Varenicline as a Cause of Suicidal Outcomes". Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntu275. PMID 25572451.

- ^ Yeung EYH, Long S, Bachi BL, Lee J, Chao Y (2015). "The psychiatric effects of varenicline on patients with depression" (PDF). BMC Proceedings. 9 (Suppl1): A31. doi:10.1186/1753-6561-9-S1-A31. PMC 4306032.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Yeung EYH, Bachi BL, Long S, Lee JSH, Chao Y (2015). "Varenicline and Depression: a Literature Review". World Journal of Medical Education and Research. 9 (1): 24–29.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "FDA Drug Safety Communication: Chantix (varenicline) may increase the risk of certain cardiovascular adverse events in patients with cardiovascular disease". 2011-06-16.

- ^ Mills, EJ; Thorlund, K; Eapen, S; Wu, P; Prochaska, JJ (7 January 2014). "Cardiovascular events associated with smoking cessation pharmacotherapies: a network meta-analysis". Circulation. 129 (1): 28–41. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.113.003961. PMID 24323793.

- ^ Singh, S; Loke, YK, Spangler, JG, Furberg, CD (Sep 6, 2011). "Risk of serious adverse cardiovascular events associated with varenicline: a systematic review and meta-analysis" (PDF). CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association. 183 (12): 1359–66. doi:10.1503/cmaj.110218. PMC 3168618. PMID 21727225.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Takagi, H; Umemoto, T (Sep 6, 2011). "Varenicline: quantifying the risk". CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association. 183 (12): 1404. doi:10.1503/cmaj.111-2063. PMC 3168634. PMID 21896705.

- ^ Samuels, L (Sep 6, 2011). "Varenicline: cardiovascular safety". CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association. 183 (12): 1407–08. doi:10.1503/cmaj.111-2073. PMC 3168639. PMID 21896709.

- ^ "European Medicine Agency confirms positive benefit-risk balance for Champix". 2011-07-21.

- ^ Prochaska JJ, Hilton JF; Hilton (2012). "Risk of cardiovascular serious adverse events associated with varenicline use for tobacco cessation: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ. 344: e2856. doi:10.1136/bmj.e2856. PMC 3344735. PMID 22563098.

- ^ Mihalak KB, Carroll FI, Luetje CW; Carroll; Luetje (2006). "Varenicline is a partial agonist at alpha4beta2 and a full agonist at alpha7 neuronal nicotinic receptors". Mol. Pharmacol. 70 (3): 801–805. doi:10.1124/mol.106.025130. PMID 16766716.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mineur YS, Picciotto MR; Picciotto (December 2010). "Nicotine receptors and depression: revisiting and revising the cholinergic hypothesis". Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 31 (12): 580–6. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2010.09.004. PMC 2991594. PMID 20965579.

- ^ http://jpet.aspetjournals.org/content/342/2/327.long

- ^ Elrashidi MY, Ebbert JO (June 2014). "Emerging drugs for the treatment of tobacco dependence: 2014 update". Expert Opin Emerg Drug (Review). 19 (2): 243–60. doi:10.1517/14728214.2014.899580. PMID 24654737.

- ^ Obach, RS; Reed-Hagen, AE; Krueger, SS; Obach, BJ; O'Connell, TN; Zandi, KS; Miller, S; Coe, JW (2006). "Metabolism and disposition of varenicline, a selective alpha4beta2 acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, in vivo and in vitro". Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 34 (1): 121–130. doi:10.1124/dmd.105.006767. PMID 16221753.

- ^ "[Cytisine as an aid for smoking cessation]". Med Monatsschr Pharm. 15 (1): 20–1. Jan 1992. PMID 1542278.

- ^ Prochaska, BMJ 347:f5198 2013 http://www.bmj.com/content/347/bmj.f5198

- ^ Coe JW; Brooks PR; Vetelino MG; et al. (2005). "Varenicline: an alpha4beta2 nicotinic receptor partial agonist for smoking cessation". J. Med. Chem. 48 (10): 3474–3477. doi:10.1021/jm050069n. PMID 15887955.

{{cite journal}}:|first10=missing|last10=(help);|first11=missing|last11=(help); Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Schwartz JL (1979). "Review and evaluation of methods of smoking cessation, 1969–77. Summary of a monograph". Public Health Rep. 94 (6): 558–63. PMC 1431736. PMID 515342.

- ^ Etter JF (2006). "Cytisine for smoking cessation: a literature review and a meta-analysis". Arch. Intern. Med. 166 (15): 1553–1559. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.15.1553. PMID 16908787.

- ^ Kuehn BM (2006). "FDA speeds smoking cessation drug review". JAMA. 295 (6): 614–614. doi:10.1001/jama.295.6.614. PMID 16467225.

- ^ European Medicines Agency (2011-01-28). "EPAR summary for the public. Champix varenicline". London. Retrieved 2011-02-14.