Jerusalem

Jerusalem

יְרוּשָׁלַיִם (Yerushalayim) القُدس (al-Quds) | |

|---|---|

City | |

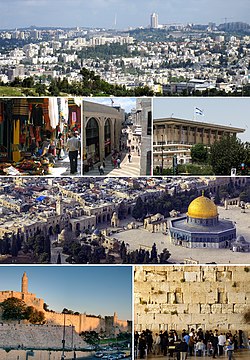

From upper left: Jerusalem skyline viewed from Givat ha'Arba, Mamilla, the Old City and the Dome of the Rock, a souq in the Old City, the Knesset, the Western Wall, the Tower of David and the Old City walls | |

|

| |

| Nickname(s): Ir ha-Kodesh (Holy City), Bayt al-Maqdis (House of the Holiness) | |

| |

| District | Jerusalem |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Nir Barkat |

| Area | |

| • City | 125,156 dunams (125.156 km2 or 48.323 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 652,000 dunams (652 km2 or 252 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 754 m (2,474 ft) |

| Population (2012) | |

| • City | 801,000 |

| • Density | 6,400/km2 (17,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 1,029,300 |

| Demonym | Jerusalemite |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (IST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (IDT) |

| Area code(s) | overseas dialing +972-2; local dialing 02 |

| Website | jerusalem.muni.il[iv] |

| Part of a series on |

| Jerusalem |

|---|

|

Jerusalem (/[invalid input: 'icon']dʒəˈruːsələm/; Template:Lang-he-n Yerushaláyim ⓘ; Arabic: القُدس al-Quds ⓘ and/or أورشليم Ûrshalîm)[i] is the capital of Israel, though not internationally recognized as such,[ii] and one of the oldest cities in the world.[1] It is located in the Judean Mountains, between the Mediterranean Sea and the northern edge of the Dead Sea. If the area and population of East Jerusalem is included, it is Israel's largest city in both population and area,[2][3] with a population of 801,000 residents[4] over an area of 125.1 km2 (48.3 sq mi).[5][6][iii] Jerusalem is also a holy city to the three major Abrahamic religions—Judaism, Christianity and Islam.

During its long history, Jerusalem has been destroyed twice, besieged 23 times, attacked 52 times, and captured and recaptured 44 times.[7] The oldest part of the city was settled in the 4th millennium BCE.[1] In 1538, walls were built around Jerusalem under Suleiman the Magnificent. Today those walls define the Old City, which has been traditionally divided into four quarters—known since the early 19th century as the Armenian, Christian, Jewish, and Muslim Quarters.[8] The Old City became a World Heritage site in 1981, and is on the List of World Heritage in Danger.[9] Modern Jerusalem has grown far beyond its boundaries.

In Judaism, Jerusalem has been the holiest city since, according to the Hebrew Bible, King David of Israel first established it as the capital of the united Kingdom of Israel in c.1000 BCE, and his son, King Solomon, commissioned the building of the First Temple in the city.[10] In Christianity, Jerusalem has been a holy city since, according to the New Testament, Jesus was crucified there, possibly in c.33 CE,[11][12][13] and 300 years later Saint Helena identified the pilgrimage sites of Jesus' life. In Sunni Islam, Jerusalem is the third-holiest city.[14][15] It became the first Qibla, the focal point for Muslim prayer (Salah) in 610 CE,[16] and, according to Islamic tradition, Muhammad made his Night Journey there ten years later.[17][18] As a result, despite having an area of only 0.9 square kilometres (0.35 sq mi),[19] the Old City is home to many sites of tremendous religious importance, among them the Temple Mount, the Western Wall, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the Dome of the Rock and al-Aqsa Mosque.

Today, the status of Jerusalem remains one of the core issues in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. During the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, West Jerusalem was among the areas captured and later annexed by Israel, while East Jerusalem, including the Old City, was captured by Jordan. Israel captured East Jerusalem during the 1967 Six-Day War and subsequently annexed it. Currently, Israel's Basic Law refers to Jerusalem as the country's "undivided capital". The international community has rejected the annexation as illegal and treats East Jerusalem as Palestinian territory held by Israel under military occupation.[20][21][22][23] The international community does not recognize Jerusalem as Israel's capital, and the city hosts no foreign embassies.

According to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, 208,000 Palestinians live in East Jerusalem, which is sought by the Palestinian Authority as a future capital of a future Palestinian state.[24][25][26]

All branches of the Israeli government are located in Jerusalem, including the Knesset (Israel's parliament), the residences of the Prime Minister and President, and the Supreme Court. Jerusalem is home to the Hebrew University and to the Israel Museum with its Shrine of the Book. The Jerusalem Biblical Zoo has ranked consistently as Israel's top tourist attraction for Israelis.[27][28]

Etymology

A city called Rušalimum or Urušalimum (Foundation of Shalem)[29] appears in ancient Egyptian records as the first two references to Jerusalem, dating back to the 19th and 18th centuries BCE.[30][31] The name recurs in Akkadian cuneiform as Urušalim, in the Amarna tablets datable to the 1400-1360 BCE. The name “Jerusalem” is variously etymologised to mean “foundation (Sumerian yeru, ‘settlement’/Semitic yry, ‘found’) of the god Shalem”, ‘dwelling of peace’, ‘founded in safety’,[32] or to mean ‘Salem gives instruction’ (yrh, ‘show, teach, instruct’). The god Shalem has a special relationship with Jerusalem.[33] Others dismiss the Sumerian link, and point to yarah, Semitic/Hebrew for ‘to lay a cornerstone’, yielding the idea of laying a cornerstone to the temple of the god Shalem, who was a member of the West Semitic pantheon (Akkadian Shalim, Assyrian Shulmanu), the god of the setting sun and the nether world, as well as of health and perfection.[34]

The form Yerushalayim (Jerusalem) first appears in the Bible, in the book of Joshua. This form has the appearance of a portmanteau (blend) of Yireh (an abiding place of the fear and the service of God) [35] The meaning of the common root S-L-M is unknown but is thought to refer to either "peace" (Salam or Shalom in modern Arabic and Hebrew) or Shalim, the god of dusk in the Canaanite religion.[36][37] The name gained the popular meanings "The City of Peace"[29][38] and "Abode of Peace",[39][40] alternately "Vision of Peace" in some Christian theology.[41] Typically the ending -im indicates the plural in Hebrew grammar and -ayim the dual, thus leading to the suggestion that the name refers to the fact that the city sits on two hills.[42][43] However the pronunciation of the last syllable as -ayim appears to be a late development, which had not yet appeared at the time of the Septuagint.

The most ancient settlement of Jerusalem, founded as early as the Bronze Age on the hill above the Gihon Spring, was according to the Bible named Jebus.[44] It was renamed the City of David in the first millennium BCE,[44] and was known by this name in antiquity.[45][46] Another name, "Zion", initially referred to a distinct part of the city, but later came to signify the city as a whole and to represent the biblical Land of Israel. In Greek and Latin the city's name was transliterated Hierosolyma (Greek: Ἱεροσόλυμα; in Greek hieròs, ἱερός, means holy), although the city was renamed Aelia Capitolina for part of the Roman period of its history.

In Arabic, Jerusalem is most commonly known as القُدس, transliterated as al-Quds and meaning "The Holy" or "The Holy Sanctuary".[39][40] Official Israeli government policy mandates that أُورُشَلِيمَ, transliterated as Ūršalīm, which is the cognate of the Hebrew and English names, be used as the Arabic language name for the city in conjunction with القُدس. أُورُشَلِيمَ-القُدس.[47]

History

Given the city's central position in both Israeli nationalism (Zionism) and Palestinian nationalism, the selectivity required to summarise more than 5,000 years of inhabited history is often[48][49] influenced by ideological bias or background (see Historiography and nationalism). For example, the Jewish periods of the city's history are important to Israeli nationalists (Zionists), whose discourse suggests that modern Jews descend from the Israelites and Maccabees,[50][51] whilst the Islamic, Christian and other non-Jewish periods of the city's history are important to Palestinian nationalism, whose discourse suggests that modern Palestinians descend from all the different peoples who have lived in the region.[52][53] As a result, both sides claim the history of the city has been politicized by the other in order to strengthen their relative claims to the city,[48][48][49][54][55] and that this is borne out by the different focuses the different writers place on the various events and eras in the city's history.

Overview of Jerusalem's historical periods

Ancient period

Ceramic evidence indicates occupation of the City of David, within present-day Jerusalem, as far back as the Copper Age (c. 4th millennium BCE),[1][56] with evidence of a permanent settlement during the early Bronze Age (c. 3000–2800 BCE).[56][57] The Execration Texts (c. 19th century BCE), which refer to a city called Roshlamem or Rosh-ramen[56] and the Amarna letters (c. 14th century BCE) may be the earliest mention of the city.[58][59] Some archaeologists, including Kathleen Kenyon, believe Jerusalem[60] as a city was founded by Northwest Semitic people with organized settlements from around 2600 BCE. According to Jewish tradition, the city was founded by Shem and Eber, ancestors of Abraham. In the biblical account, Jerusalem ("Salem") when first mentioned is ruled by Melchizedek, an ally of Abraham (identified with Shem in legend). Later, in the time of Joshua, Jerusalem lay within territory allocated to the tribe of Benjamin (Joshua 18:28), but continued to be under the independent control of the Jebusites until it was conquered by David and made into the capital of the united Kingdom of Israel (c. 11th century BCE).[61][62][v] Recent excavations of a Large Stone Structure and a nearby Stepped Stone Structure are widely believed[by whom?] to be the remains of King David's palace. The excavations have been interpreted by some archaeologists as lending credence to the biblical narrative, while others disagree.[63]

According to Hebrew scripture, King David reigned for 40 years. The generally accepted estimate of the conclusion of this reign is 970 BCE. The Bible records that David was succeeded by his son Solomon,[64] who built the Holy Temple on Mount Moriah. Solomon's Temple (later known as the First Temple), went on to play a pivotal role in Jewish history as the repository of the Ark of the Covenant.[65] For more than 400 years, until the Babylonian conquest in 587 BCE, Jerusalem was the political capital of the united Kingdom of Israel and then the Kingdom of Judah. During this period, known as the First Temple Period,[66] the Temple was the religious center of the Israelites.[67] On Solomon's death (c. 930 BCE), the ten northern tribes split off to form the Kingdom of Israel. Under the leadership of the House of David and Solomon, Jerusalem remained the capital of the Kingdom of Judah.[68]

When the Assyrians conquered the Kingdom of Israel in 722 BCE, Jerusalem was strengthened by a great influx of refugees from the northern kingdom. The First Temple period ended around 586 BCE, as the Babylonians conquered Judah and Jerusalem, and laid waste to Solomon's Temple.[66]

Classical antiquity

In 538 BCE, after 50 years of Babylonian captivity, Persian King Cyrus the Great invited the Jews to return to Judah to rebuild the Temple.[69] Construction of the Second Temple was completed in 516 BCE, during the reign of Darius the Great, 70 years after the destruction of the First Temple.[70][71] In about 445 BCE, King Artaxerxes I of Persia issued a decree allowing the city and the walls to be rebuilt.[72] Jerusalem resumed its role as capital of Judah and center of Jewish worship.

When Alexander the Great conquered the Persian Empire, Jerusalem and Judea came under Macedonian control, eventually falling to the Ptolemaic dynasty under Ptolemy I. In 198 BCE, Ptolemy V lost Jerusalem and Judea to the Seleucids under Antiochus III. The Seleucid attempt to recast Jerusalem as a Hellenized city-state came to a head in 168 BCE with the successful Maccabean revolt of Mattathias and his five sons against Antiochus Epiphanes, and their establishment of the Hasmonean Kingdom in 152 BCE with Jerusalem again as its capital.

In 63 BCE, Pompey the Great intervened in a Hasmonean struggle for the throne and captured Jerusalem, extending the influence of the Roman Republic over Judea.[73] Following a short invasion by Parthians, backing the rival Hasmonean rulers, Judea became a scene of struggle between pro-Roman and pro-Parthian forces, eventually leading to the emergence of Edomite Herod, who would be appointed King of the Jews by the Roman senate and establish the Herodian dynasty.

As Rome became stronger it installed Herod as a Jewish client king. Herod the Great, as he was known, devoted himself to developing and beautifying the city. He built walls, towers and palaces, and expanded the Temple Mount, buttressing the courtyard with blocks of stone weighing up to 100 tons. Under Herod, the area of the Temple Mount doubled in size.[64][74][75] Shortly after Herod's death, in 6 CE Judea came under direct Roman rule as the Iudaea Province,[76] although Herod's descendants through Agrippa II remained client kings of neighbouring territories until 96 CE. Roman rule over Jerusalem and the region began to be challenged with the First Jewish–Roman War, which resulted in the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE. Jerusalem once again served as the capital of Judea during the three-year rebellion known as the Bar Kokhba revolt, beginning in 132 CE. The Romans succeeded in suppressing the revolt in 135 CE. Emperor Hadrian combined Iudaea Province with neighboring provinces to create Syria Palaestina, erasing the name of Judea,[77] romanized the city, renaming it Aelia Capitolina,[78] and banned the Jews from entering it on pain of death, except for one day each year (9 Ab). These anti-Jewish measures[79][80][81] which affected also Jewish Christians,[82] was taken to ensure 'the complete and permanent secularization of Jerusalem.'[83] The enforcement of the ban on Jews entering Aelia Capitolina continued until the 4th century CE.

In the five centuries following the Bar Kokhba revolt, the city remained under Roman then Byzantine rule. During the 4th century, the Roman Emperor Constantine I constructed Christian sites in Jerusalem, such as the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Jerusalem reached a peak in size and population at the end of the Second Temple Period, when the city covered two square kilometers (0.8 sq mi.) and had a population of 200,000.[80][84] From the days of Constantine until the 7th century, Jews were banned from Jerusalem.[85]

The eastern continuation of the Roman Empire, the Byzantine Empire, maintained control of the city for years. Within the span of a few decades, Jerusalem shifted from Byzantine to Persian rule and returned to Roman-Byzantine dominion once more. Following Sassanid Khosrau II's early 7th century push into Byzantine, advancing through Syria, Sassanid Generals Shahrbaraz and Shahin attacked the Byzantine-controlled city of Jerusalem (Persian: Dej Houdkh). They were aided by the Jews of Palaestina Prima, who had risen up against the Byzantines.[86]

In the Siege of Jerusalem (614), after 21 days of relentless siege warfare, Jerusalem was captured. The Byzantine chronicles relate that the Sassanid army and the Jews slaughtered tens of thousands of Christians in the city, an episode which has been the subject of much debate between historians.[87] The conquered city would remain in Sassanid hands for some fifteen years until the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius reconquered it in 629.[86][verification needed] Reinstalled Byzantine rule resulted in wide-scale massacre of the Jews throughout Palaestina Prima and Palaestina Secunda provinces, which would practically erase the 150,000-strong Jewish community. The remnants of the Palaestinian and Jerusalemite Jews found refuge in Egypt and Mesopotamia.

Middle Ages

Byzantine Jerusalem was conquered by the Arab armies of Omar ibn Hattab in 634. Among Muslims of Islam's earliest era it was referred to as Madinat bayt al-Maqdis ("City of the Temple")[88] which was restricted to the Temple Mount. The rest of the city "...was called Iliya, reflecting the Roman name given the city following the destruction of 70 c.e.: Aelia Capitolina".[89] Later the Temple Mount became known as al-Haram al-Sharif, “The Noble Sanctuary”, while the city around it became known as Bayt al-Maqdis,[90] and later still, al-Quds al-Sharif "The Noble City". The Islamization of Jerusalem began in the first year A.H. (620 CE), when Muslims were instructed to face the city while performing their daily prostrations and, according to Muslim religious tradition, Muhammad's night journey and ascension to heaven took place. After 16 months, the direction of prayer was changed to Mecca.[91] In 638 the Islamic Caliphate extended its dominion to Jerusalem.[92] With the Arab conquest, Jews were allowed back into the city.[93] The Rashidun caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab signed a treaty with Monophysite Christian Patriarch Sophronius, assuring him that Jerusalem's Christian holy places and population would be protected under Muslim rule.[94] Christian-Arab tradition records that, when led to pray at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the holiest site for Christians, the caliph Umar refused to pray in the church so that Muslims would not request conversion of the church to a mosque.[95] He prayed outside the church, where the Mosque of Umar (Omar) stands to this day, opposite the entrance to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. According to the Gaullic bishop Arculf, who lived in Jerusalem from 679 to 688, the Mosque of Umar was a rectangular wooden structure built over ruins which could accommodate 3,000 worshipers.[96] When the Muslims went to Bayt Al-Maqdes for the first time, They searched for the site of the Far Away Holy Mosque (Al-Masjed Al-Aqsa) that was mentioned in Quran and Hadith according to Islamic beliefs. Contemporary Arabic and Hebrew sources say the site was full of rubbish, and that Arabs and Jews cleaned it.[97] The Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik commissioned the construction of the Dome of the Rock in the late 7th century.[98] The 10th century historian al-Muqaddasi writes that Abd al-Malik built the shrine in order to compete in grandeur with Jerusalem's monumental churches.[96] Over the next four hundred years Jerusalem's prominence diminished as Arab powers in the region jockeyed for control.[99]

In 1099, The Fatimid ruler expelled the native Christian population before Jerusalem was conquered by the Crusaders, who massacred most of its Muslim and Jewish inhabitants when they took the solidly defended city by assault, after a period of siege; later the Crusaders created the Kingdom of Jerusalem. By early June 1099 Jerusalem’s population had declined from 70,000 to less than 30,000.[100]

In 1187, the city was wrested from the Crusaders by Saladin who permitted Jews and Muslims to return and settle in the city.[101] Under the Ayyubid dynasty of Saladin, a period of huge investment began in the construction of houses, markets, public baths, and pilgrim hostels as well as the establishment of religious endowments. However, for most of the 13th century, Jerusalem declined to the status of a village due to city's fall of strategic value and Ayyubid internecine struggles.[102]

In 1244, Jerusalem was sacked by the Khwarezmian Tartars, who decimated the city's Christian population and drove out the Jews.[103] The Khwarezmian Tartars were driven out by the Ayyubids in 1247. From 1250 to 1517, Jerusalem was ruled by the Mamluks. During this period of time many clashes occurred between the Mamluks on one side and the crusaders and the Mongols on the other side. The area also suffered from many earthquakes and black plague.[citation needed] Some European Christian presence was maintained in the city by the Order of the Holy Sepulchre.

Early modern period

In 1517, Jerusalem and environs fell to the Ottoman Turks, who generally remained in control until 1917.[101] Jerusalem enjoyed a prosperous period of renewal and peace under Suleiman the Magnificent – including the rebuilding of magnificent walls around the Old City. Throughout much of Ottoman rule, Jerusalem remained a provincial, if religiously important center, and did not straddle the main trade route between Damascus and Cairo.[104] The English reference book Modern history or the present state of all nations written in 1744 stated that "Jerusalem is still reckoned the capital city of Palestine".[105]

The Ottomans brought many innovations: modern postal systems run by the various consulates; the use of the wheel for modes of transportation; stagecoach and carriage, the wheelbarrow and the cart; and the oil-lantern, among the first signs of modernization in the city.[106] In the mid 19th century, the Ottomans constructed the first paved road from Jaffa to Jerusalem, and by 1892 the railroad had reached the city.[106]

Modern period

With the annexation of Jerusalem by Muhammad Ali of Egypt in 1831, foreign missions and consulates began to establish a foothold in the city. In 1836, Ibrahim Pasha allowed Jerusalem's Jewish residents to restore four major synagogues, among them the Hurva.[107] In the 1834 Arab revolt in Palestine, Qasim al-Ahmad led his forces from Nablus and attacked Jerusalem, aided by the Abu Ghosh clan, entered the city on 31 May 1834. The Christians and Jews of Jerusalem were subjected to attacks. Ibrahim's Egyptian army routed Qasim's forces in Jerusalem the following month.[108]

Ottoman rule was reinstated in 1840, but many Egyptian Muslims remained in Jerusalem and Jews from Algiers and North Africa began to settle in the city in growing numbers.[107] In the 1840s and 1850s, the international powers began a tug-of-war in Palestine as they sought to extend their protection over the region's religious minorities, a struggle carried out mainly through consular representatives in Jerusalem.[109] According to the Prussian consul, the population in 1845 was 16,410, with 7,120 Jews, 5,000 Muslims, 3,390 Christians, 800 Turkish soldiers and 100 Europeans.[107] The volume of Christian pilgrims increased under the Ottomans, doubling the city's population around Easter time.[110]

In the 1860s, new neighborhoods began to develop outside the Old City walls to house pilgrims and relieve the intense overcrowding and poor sanitation inside the city. The Russian Compound and Mishkenot Sha'ananim were founded in 1860.[111] In 1867 an American Missionary reports an estimated population of Jerusalem of 'above' 15,000, with 4,000 to 5,000 Jews and 6,000 Muslims. Every year there were 5,000 to 6,000 Russian Christian Pilgrims.[112]

Until the 1880s there were no formal orphanages in Jerusalem, as families generally took care of each other. In 1881 the Diskin Orphanage was founded in Jerusalem with the arrival of Jewish children orphaned by a Russian pogrom. Other orphanages founded in Jerusalem at the beginning of the 20th century were Zion Blumenthal Orphanage (1900) and General Israel Orphan's Home for Girls (1902).[113]

British Mandate

In 1917 after the Battle of Jerusalem, the British Army, led by General Edmund Allenby, captured the city,[114] and in 1922, the League of Nations at the Conference of Lausanne entrusted the United Kingdom to administer the Mandate for Palestine, the neighbouring mandate of Transjordan to the east across the River Jordan, and the Iraq Mandate beyond it.

From 1922 to 1948 the total population of the city rose from 52,000 to 165,000 with two thirds of Jews and one-third of Arabs (Muslims and Christians).[115] The situation between Arabs and Jews in Palestine was not quiet. In Jerusalem, in particular, riots occurred in 1920 and in 1929. Under the British, new garden suburbs were built in the western and northern parts of the city[116][117] and institutions of higher learning such as the Hebrew University were founded.[118]

Division and reunification 1948–1967

As the British Mandate for Palestine was expiring, the 1947 UN Partition Plan recommended "the creation of a special international regime in the City of Jerusalem, constituting it as a corpus separatum under the administration of the UN."[119] The international regime (which also included the city of Bethlehem) was to remain in force for a period of ten years, whereupon a referendum was to be held in which the residents were to decide the future regime of their city. However, this plan was not implemented, as the 1948 war erupted, while the British withdrew from Palestine and Israel declared its independence.[120] The war led to displacement of Arab and Jewish populations in the city. The 1,500 residents of the Jewish Quarter of the Old City were expelled and a few hundred taken prisoner when the Arab Legion captured the quarter on 28 May.[121][122] The Arab Legion also attacked Western Jerusalem with snipers.[123] Arab residents of Katamon, Talbiya, and the German Colony were driven from their homes. By the end of the war Israel had control of 12 of Jerusalem's 15 Arab residential quarters. An estimated minimum of 30,000 people had become refugees.[124][125]

The war of 1948 resulted in Jerusalem being divided, with the old walled city lying entirely on the Jordanian side of the line. A no-man's land between East and West Jerusalem came into being in November 1948: Moshe Dayan, commander of the Israeli forces in Jerusalem, met with his Jordanian counterpart Abdullah el Tell in a deserted house in Jerusalem’s Musrara neighborhood and marked out their respective positions: Israel’s position in red and Jordan's in green. This rough map, which was not meant as an official one, became the final line in the 1949 Armistice Agreements, which divided the city and left Mount Scopus as an Israeli exclave inside East Jerusalem.[126] Barbed wire and concrete barriers ran down the center of the city, passing close by Jaffa Gate on the western side of the old walled city, and a crossing point was established at Mandelbaum Gate slightly to the north of the old walled city. Military skirmishes frequently threatened the ceasefire. After the establishment of the State of Israel, Jerusalem was declared its capital. Jordan formally annexed East Jerusalem in 1950, subjecting it to Jordanian law.[120][127] Only the United Kingdom and Pakistan formally recognized such annexation, which, in regard to Jerusalem, was on a de facto basis.[128] Also, it is dubious if Pakistan recognized Jordan's annexation.[129][130]

After 1948, since the old walled city in its entirety was to the east of the armistice line, Jordan was able to take control of all the holy places therein, and contrary to the terms of the armistice agreement, denied Jews access to Jewish holy sites, many of which were desecrated. Jordan allowed only very limited access to Christian holy sites.[131] Of the 58 synagogues in the Old City, half were either razed or converted to stables and hen-houses over the course of the next 19 years, including the Hurva and the Tiferet Yisrael Synagogue. The Jewish Cemetery on the Mount of Olives was desecrated, with gravestones used as to build roads and latrines.[132] Many other historic and religiously significant buildings were demolished and replaced by modern structures.[133] During this period, the Dome of the Rock and Al-Aqsa Mosque underwent major renovations.[134] The Jewish Quarter became known as Harat al-Sharaf, and was resettled with refugees from the 1948 war. In 1966 the Jordanian authorities relocated 500 of them to the Shua'fat refugee camp as part of plans to redevelop the area.[135]

In 1967, despite Israeli pleas that Jordan remain neutral during the Six-Day War, Jordanian forces attacked Israeli-held West Jerusalem on the war's second day. After hand to hand fighting between Israeli and Jordanian soldiers on the Temple Mount, the Israel Defense Force captured East Jerusalem, along with the entire West Bank. East Jerusalem, along with some nearby West Bank territory, was subsequently annexed by Israel. On 27 June 1967, a few weeks after the war ended, Israel extended its law and jurisdiction to East Jerusalem and some surrounding area, incorporating it into the Jerusalem Municipality.[136] Although at the time Israel informed the United Nations that its measures constituted administrative and municipal integration rather than annexation, later rulings by the Israeli Supreme Court indicated that the eastern sector of Jerusalem had become part of Israel. In 1980, Israel passed the Jerusalem Law as an addition to its Basic Laws, which declared Jerusalem the "complete and united" capital of Israel.[137] Following the annexation, Israel conducted a census of Arab residents in the areas annexed. Residents were given permanent residency status and the option of applying for Israeli citizenship.

Jewish and Christian access to the holy sites inside the old walled city was restored. Israel left the Temple Mount under the jurisdiction of an Islamic waqf, but opened the Western Wall to Jewish access. The Moroccan Quarter, which was located adjacent to the Western Wall, was evacuated and razed[138] to make way for a plaza for those visiting the wall.[139] In the following days, Arabs living in the Jewish Quarter were also evicted. On April 18, 1968, the Israeli Treasury Ministry official expropriated the land of the former Moroccan Quarter and the Jewish Quarter for public use, and offered 200 Jordanian dinars to each displaced Arab family.

After the Six-Day War, Palestinians from the West Bank began moving to Jerusalem. In the decade following the war, the city's Arab population increased by more than 50 percent. In response, Israeli Agriculture Minister Ariel Sharon proposed building a ring of Jewish neighborhoods around the city's eastern edges. The plan was intended to make East Jerusalem more Jewish and prevent it from becoming part of an urban Palestinian bloc stretching from Bethlehem to Ramallah. On October 2, 1977, the Israeli cabinet approved the plan, and seven neighborhoods were subsequently built on the city's eastern edges. They became known as the Ring Neighborhoods. Other Jewish neighborhoods were built within East Jerusalem, and Israeli Jews also settled in Arab neighborhoods.[140][141]

The annexation of East Jerusalem was met with international criticism. Following the passing of the Jerusalem Law, the United Nations Security Council passed a resolution that declared the law "a violation of international law" and requested all member states to withdraw all remaining embassies from the city.[142] The Israeli Foreign Ministry disputes that the annexation of Jerusalem was a violation of international law.[143][144]

Today

The status of the city, and especially its holy places, remains a core issue in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The Israeli government has approved building plans in the Muslim Quarter of the Old City[145] in order to expand the Jewish presence in East Jerusalem, while prominent Islamic leaders have made claims that Jews have no historical connection to Jerusalem, alleging that the 2,500-year old Western Wall was constructed as part of a mosque.[146] Palestinians envision East Jerusalem as the capital of a future Palestinian state,[147][148] and the city's borders have been the subject of bilateral talks. A strong longing for peace is symbolized by the Peace Monument (with farming tools made out of scrap weapons), facing the Old City wall near the former Israeli-Jordanian border and quoting from the book of Isaiah in Arabic and Hebrew.[149]

Geography

Jerusalem is situated on the southern spur of a plateau in the Judean Mountains, which include the Mount of Olives (East) and Mount Scopus (North East). The elevation of the Old City is approximately 760 m (2,490 ft).[150] The whole of Jerusalem is surrounded by valleys and dry riverbeds (wadis). The Kidron, Hinnom, and Tyropoeon Valleys intersect in an area just south of the Old City of Jerusalem.[151] The Kidron Valley runs to the east of the Old City and separates the Mount of Olives from the city proper. Along the southern side of old Jerusalem is the Valley of Hinnom, a steep ravine associated in biblical eschatology with the concept of Gehenna or Hell.[152] The Tyropoeon Valley commenced in the northwest near the Damascus Gate, ran south-southeasterly through the center of the Old City down to the Pool of Siloam, and divided the lower part into two hills, the Temple Mount to the east, and the rest of the city to the west (the lower and the upper cities described by Josephus). Today, this valley is hidden by debris that has accumulated over the centuries.[151] In biblical times, Jerusalem was surrounded by forests of almond, olive and pine trees. Over centuries of warfare and neglect, these forests were destroyed. Farmers in the Jerusalem region thus built stone terraces along the slopes to hold back the soil, a feature still very much in evidence in the Jerusalem landscape.[citation needed]

Water supply has always been a major problem in Jerusalem, as attested to by the intricate network of ancient aqueducts, tunnels, pools and cisterns found in the city.[153]

Jerusalem is 60 kilometers (37 mi)[154] east of Tel Aviv and the Mediterranean Sea. On the opposite side of the city, approximately 35 kilometers (22 mi)[155] away, is the Dead Sea, the lowest body of water on Earth. Neighboring cities and towns include Bethlehem and Beit Jala to the south, Abu Dis and Ma'ale Adumim to the east, Mevaseret Zion to the west, and Ramallah and Giv'at Ze'ev to the north.[156][157][158]

Mount Herzl, at the western side of the city near the Jerusalem Forest, serves as the national cemetery of Israel.

Climate

The city is characterized by a Mediterranean climate, with hot, dry summers, and mild, wet winters. Snow flurries usually occur once or twice a winter, although the city experiences heavy snowfall every three to four years, on average, with short-lived accumulation. January is the coldest month of the year, with an average temperature of 9.1 °C (48.4 °F); July and August are the hottest months, with an average temperature of 24.2 °C (75.6 °F), and the summer months are usually rainless. The average annual precipitation is around 550 mm (22 in), with rain occurring almost entirely between October and May.[159] Jerusalem has nearly 3,400 annual sunshine hours.[citation needed]

Most of the air pollution in Jerusalem comes from vehicular traffic.[160] Many main streets in Jerusalem were not built to accommodate such a large volume of traffic, leading to traffic congestion and more carbon monoxide released into the air. Industrial pollution inside the city is sparse, but emissions from factories on the Israeli Mediterranean coast can travel eastward and settle over the city.[160][161]

| Climate data for Jerusalem (1881–2007) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 23.4 (74.1) |

25.3 (77.5) |

27.6 (81.7) |

35.3 (95.5) |

37.2 (99.0) |

36.8 (98.2) |

40.6 (105.1) |

44.4 (111.9) |

37.8 (100.0) |

33.8 (92.8) |

29.4 (84.9) |

26 (79) |

44.4 (111.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 11.8 (53.2) |

12.6 (54.7) |

15.4 (59.7) |

21.5 (70.7) |

25.3 (77.5) |

27.6 (81.7) |

29.0 (84.2) |

29.4 (84.9) |

28.2 (82.8) |

24.7 (76.5) |

18.8 (65.8) |

14.0 (57.2) |

21.5 (70.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 9.1 (48.4) |

9.5 (49.1) |

11.9 (53.4) |

17.1 (62.8) |

20.5 (68.9) |

22.7 (72.9) |

24.2 (75.6) |

24.5 (76.1) |

23.4 (74.1) |

20.7 (69.3) |

15.6 (60.1) |

11.2 (52.2) |

17.5 (63.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 6.4 (43.5) |

6.4 (43.5) |

8.4 (47.1) |

12.6 (54.7) |

15.7 (60.3) |

17.8 (64.0) |

19.4 (66.9) |

19.5 (67.1) |

18.6 (65.5) |

16.6 (61.9) |

12.3 (54.1) |

8.4 (47.1) |

13.5 (56.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −6.7 (19.9) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

0.8 (33.4) |

7.6 (45.7) |

11 (52) |

14.6 (58.3) |

15.5 (59.9) |

13.2 (55.8) |

9.8 (49.6) |

1.8 (35.2) |

0.2 (32.4) |

−6.7 (19.9) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 133.2 (5.24) |

118.3 (4.66) |

92.7 (3.65) |

24.5 (0.96) |

3.2 (0.13) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.3 (0.01) |

15.4 (0.61) |

60.8 (2.39) |

105.7 (4.16) |

554.1 (21.81) |

| Average rainy days | 12.9 | 11.7 | 9.6 | 4.4 | 1.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 3.6 | 7.3 | 10.9 | 62 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 72 | 69 | 63 | 58 | 41 | 44 | 52 | 57 | 58 | 56 | 61 | 69 | 58 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 192.2 | 226.3 | 243.6 | 267.0 | 331.7 | 381.0 | 384.4 | 365.8 | 309.0 | 275.9 | 228.0 | 192.2 | 3,397.1 |

| Source 1: Israel Meteorological Service[162][163] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Hong Kong Observatory for data of sunshine hours[164] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

Demographic history

Jerusalem's population size and composition has shifted many times over its 5,000 year history. Since medieval times, the Old City of Jerusalem has been divided into Jewish, Muslim, Christian, and Armenian quarters.

Most population data pre-1905 is based on estimates, often from foreign travellers or organisations, since previous census data usually covered wider areas such as the Jerusalem District.[165] These estimates suggest that since the end of the Crusades, Muslims formed the largest group in Jerusalem until the mid-nineteenth century.

Between 1838 and 1876, a number of estimates exist which conflict as to whether Jews or Muslims were the largest group during this period, and between 1882 and 1922 estimates conflict as to exactly when Jews became a majority of the population.

Current demographics

In December 2007, Jerusalem had a population of 747,600—64% were Jewish, 32% Muslim, and 2% Christian.[5] At the end of 2005, the population density was 5,750.4/km2 (14,893/sq mi).[3][166] According to a study published in 2000, the percentage of Jews in the city's population had been decreasing; this was attributed to a higher Muslim birth rate, and Jewish residents leaving. The study also found that about nine percent of the Old City's 32,488 people were Jews.[167]

In 2005, 2,850 new immigrants settled in Jerusalem, mostly from the United States, France and the former Soviet Union. In terms of the local population, the number of outgoing residents exceeds the number of incoming residents. In 2005, 16,000 left Jerusalem and only 10,000 moved in.[3] Nevertheless, the population of Jerusalem continues to rise due to the high birth rate, especially in the Haredi Jewish and Arab communities. Consequently, the total fertility rate in Jerusalem (4.02) is higher than in Tel Aviv (1.98) and well above the national average of 2.90. The average size of Jerusalem's 180,000 households is 3.8 people.[3]

In 2005, the total population grew by 13,000 (1.8%)—similar to Israeli national average, but the religious and ethnic composition is shifting. While 31% of the Jewish population is made up of children below the age fifteen, the figure for the Arab population is 42%.[3] This would seem to corroborate the observation that the percentage of Jews in Jerusalem has declined over the past four decades. In 1967, Jews accounted for 74 percent of the population, while the figure for 2006 is down nine percent.[168] Possible factors are the high cost of housing, fewer job opportunities and the increasingly religious character of the city, although proportionally, young Haredim are leaving in higher numbers.[citation needed] Many people are moving to the suburbs and coastal cities in search of cheaper housing and a more secular lifestyle.[169] In 2009, the percentage of Haredim in the city was increasing. As of 2009, out of 150,100 schoolchildren, 59,900 or 40% are in state-run secular and National Religious schools, while 90,200 or 60% are in Haredi schools. This correlates with the high number of children in Haredi families.[170][171]

While some Israelis see Jerusalem as poor, rundown and riddled with religious and political tension, the city has been a magnet for Palestinians, offering more jobs and opportunity than any city in the West Bank or Gaza Strip. Palestinian officials have encouraged Arabs over the years to stay in the city to maintain their claim.[172][173] Palestinians are attracted to the access to jobs, healthcare, social security, other benefits, and quality of life Israel provides to Jerusalem residents.[174] Arab residents of Jerusalem who choose not to have Israeli citizenship are granted an Israeli identity card that allows them to pass through checkpoints with relative ease and to travel throughout Israel, making it easier to find work. Residents also are entitled to the subsidized healthcare and social security benefits Israel provides its citizens, and have the right to vote in municipal elections. Arabs in Jerusalem can send their children to Israeli-run schools, although not every neighborhood has one, and universities. Israeli doctors and highly regarded hospitals such as Hadassah Medical Center are available to residents.[175]

Demographics and the Jewish-Arab population divide play a major role in the dispute over Jerusalem. In 1998, the Jerusalem Development Authority proposed expanding city limits to the west to include more areas heavily populated with Jews.[176]

Urban planning issues

Critics of efforts to promote a Jewish majority in Jerusalem say that government planning policies are motivated by demographic considerations and seek to limit Arab construction while promoting Jewish construction.[177] According to a World Bank report, the number of recorded building violations between 1996 and 2000 was four and half times higher in Jewish neighborhoods but four times fewer demolition orders were issued in West Jerusalem than in East Jerusalem; Arabs in Jerusalem were less likely to receive construction permits than Jews, and "the authorities are much more likely to take action against Palestinian violators" than Jewish violators of the permit process.[178] In recent years, private Jewish foundations have received permission from the government to develop projects on disputed lands, such as the City of David archaeological park in the 60% Arab neighborhood of Silwan (adjacent to the Old City),[179] and the Museum of Tolerance on Mamilla cemetery (adjacent to Zion Square).[178][180] Opponents view such urban planning moves as geared towards the Judaization of Jerusalem.[181][182][183]

Local government

The Jerusalem City Council is a body of 31 elected members headed by the mayor, who serves a five-year term and appoints eight deputies. The former mayor of Jerusalem, Uri Lupolianski, was elected in 2003.[184] In the November 2008 city elections, Nir Barkat came out as the winner and is now the mayor. Apart from the mayor and his deputies, City Council members receive no salaries and work on a voluntary basis. The longest-serving Jerusalem mayor was Teddy Kollek, who spent 28 years—-six consecutive terms-—in office. Most of the meetings of the Jerusalem City Council are private, but each month, it holds a session that is open to the public.[184] Within the city council, religious political parties form an especially powerful faction, accounting for the majority of its seats.[185] The headquarters of the Jerusalem Municipality and the mayor's office are at Safra Square (Kikar Safra) on Jaffa Road. The municipal complex, comprising two modern buildings and ten renovated historic buildings surrounding a large plaza, opened in 1993.[186] The city falls under the Jerusalem District, with Jerusalem as the district's capital.

Political status

Under the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine passed by the UN in 1947, Jerusalem was envisaged to become a corpus separatum administered by the United Nations. While the Jewish leaders accepted the partition plan, the Arab leadership (the Arab Higher Committee in Palestine and the Arab League) rejected it, opposing any partition.[187][188] In the war of 1948, the western part of the city was occupied by forces of the nascent state of Israel, while the eastern part was occupied by Jordan. The international community largely considers the legal status of Jerusalem to derive from the partition plan, and correspondingly refuses to recognize Israeli sovereignty in the city. On 5 December 1949, the State of Israel's first Prime Minister, David Ben-Gurion, proclaimed Jerusalem as Israel's capital,[189] and since then all branches of the Israeli government—legislative, judicial, and executive—have resided there, except for the Ministry of Defense, located at HaKirya in Tel Aviv.[190] At the time of the proclamation, Jerusalem was divided between Israel and Jordan and thus only West Jerusalem was proclaimed Israel's capital. Following the Six-Day War, Israel annexed East Jerusalem, and a provision stipulating that the city was the united capital of Israel was added to the country's Basic Law.[191] The status of a "united Jerusalem" as Israel's "eternal capital"[189][192] has been a matter of immense controversy within the international community. Although some countries maintain consulates in Jerusalem, all embassies are located outside the city proper, mostly in Tel Aviv.[193][194] Due to the non-recognition of Jerusalem as Israel's capital, some non-Israeli press use Tel Aviv as a metonym for Israel.[195][196][197][198]

The non-binding United Nations Security Council Resolution 478, passed on 20 August 1980, declared that the Basic Law was "null and void and must be rescinded forthwith". Member states were advised to withdraw their diplomatic representation from Jerusalem as a punitive measure. Most of the remaining countries with embassies in Jerusalem complied with the resolution by relocating them to Tel Aviv, where many embassies already resided prior to Resolution 478. Currently, there are no embassies located within the city limits of Jerusalem, although there are embassies in Mevaseret Zion, on the outskirts of Jerusalem, and four consulates in the city itself.[194] In 1995, the United States Congress had planned to move its embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem with the passage of the Jerusalem Embassy Act.[199] However, U.S. presidents have argued that Congressional resolutions regarding the status of Jerusalem are merely advisory. The Constitution reserves foreign relations as an executive power, and as such, the United States embassy is still in Tel Aviv.[200]

On 28 October 2009, United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon warned that Jerusalem must be the capital of both Israel and Palestine if peace is to be achieved.[201]

The Palestinian National Authority views East Jerusalem as occupied territory according to United Nations Security Council Resolution 242. The Palestinian Authority claims all of East Jerusalem, including the Temple Mount, as the capital of the State of Palestine, and claims that West Jerusalem is also subject to permanent status negotiations. However, it has stated that it would be willing to consider alternative solutions, such as making Jerusalem an open city.[202]

In 2010, Israel approved legislation giving Jerusalem the highest national priority status in Israel. The law prioritized construction throughout the city, and offered grants and tax benefits to residents to make housing, infrastructure, education, employment, business, tourism, and cultural events more affordable. Communications Minister Moshe Kahlon said that the bill sent "a clear, unequivocal political message that Jerusalem will not be divided", and that "all those within the Palestinian and international community who expect the current Israeli government to accept any demands regarding Israel's sovereignty over it's [sic] capital are mistaken and misleading".[203]

Government precinct and national institutions

Most national institutions of Israel are located in Jerusalem. The city is home to the Knesset,[204] the Supreme Court,[205] the official residences of the President and Prime Minister, the Cabinet, all ministries except the Ministry of Defense, and the Bank of Israel. Prior to the creation of the State of Israel, Jerusalem served as the administrative capital of the British Mandate for Palestine, which included present-day Israel and Jordan.[206] From 1949 until 1967, West Jerusalem served as Israel's capital, but was not recognized as such internationally because UN General Assembly Resolution 194 envisaged Jerusalem as an international city. As a result of the Six-Day War in 1967, the whole of Jerusalem came under Israeli control. On 27 June 1967, the government of Levi Eshkol extended Israeli law and jurisdiction to East Jerusalem, but agreed that administration of the Temple Mount compound would be maintained by the Jordanian waqf, under the Jordanian Ministry of Religious Endowments.[207] In 1988, Israel ordered the closure of Orient House, home of the Arab Studies Society, but also the headquarters of the Palestine Liberation Organization, for security reasons. The building reopened in 1992 as a Palestinian guesthouse.[208][209] The Oslo Accords stated that the final status of Jerusalem would be determined by negotiations with the Palestinian Authority. The accords banned any official Palestinian presence in the city until a final peace agreement, but provided for the opening of a Palestinian trade office in East Jerusalem. The Palestinian Authority regards East Jerusalem as the capital of a future Palestinian state.[24] President Mahmoud Abbas has said that any agreement that did not not include East Jerusalem as the capital of Palestine would be unacceptable.[210] Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has similarly stated that Jerusalem would remain the undivided capital of Israel. Due to its proximity to the city, especially the Temple Mount, Abu Dis, a Palestinian suburb of Jerusalem, has been proposed as the future capital of a Palestinian state by Israel. Israel has not incorporated Abu Dis within its security wall around Jerusalem. The Palestinian Authority has built a possible future parliament building for the Palestinian Legislative Council in the town, and its Jerusalem Affairs Offices are all located in Abu Dis.[211]

Religious significance

Jerusalem has been sacred to Judaism for roughly 3000 years, to Christianity for around 2000 years, and to Islam for approximately 1400 years. The 2000 Statistical Yearbook of Jerusalem lists 1204 synagogues, 158 churches, and 73 mosques within the city.[212] Despite efforts to maintain peaceful religious coexistence, some sites, such as the Temple Mount, have been a continuous source of friction and controversy.

Jerusalem has been sacred to the Jews since King David proclaimed it his capital in the 10th century BCE. Jerusalem was the site of Solomon's Temple and the Second Temple.[10] Although not mentioned in the Torah / Pentateuch,[213] it is mentioned in the Bible 632 times. Today, the Western Wall, a remnant of the wall surrounding the Second Temple, is a Jewish holy site second only to the Holy of Holies on the Temple Mount itself.[214] Synagogues around the world are traditionally built with the Holy Ark facing Jerusalem,[215] and Arks within Jerusalem face the "Holy of Holies".[216] As prescribed in the Mishna and codified in the Shulchan Aruch, daily prayers are recited while facing towards Jerusalem and the Temple Mount. Many Jews have "Mizrach" plaques hung on a wall of their homes to indicate the direction of prayer.[216][217]

Christianity reveres Jerusalem not only for its Old Testament history but also for its significance in the life of Jesus. According to the New Testament, Jesus was brought to Jerusalem soon after his birth[218] and later in his life cleansed the Second Temple.[219] The Cenacle, believed to be the site of Jesus' Last Supper, is located on Mount Zion in the same building that houses the Tomb of King David.[220][221] Another prominent Christian site in Jerusalem is Golgotha, the site of the crucifixion. The Gospel of John describes it as being located outside Jerusalem,[222] but recent archaeological evidence suggests Golgotha is a short distance from the Old City walls, within the present-day confines of the city.[223] The land currently occupied by the Church of the Holy Sepulchre is considered one of the top candidates for Golgotha and thus has been a Christian pilgrimage site for the past two thousand years.[223][224][225]

Jerusalem is considered by some as the third-holiest city in Sunni Islam.[14] For approximately a year, before it was permanently switched to the Kabaa in Mecca, the qibla (direction of prayer) for Muslims was Jerusalem.[226] The city's lasting place in Islam, however, is primarily due to Muhammad's Night of Ascension (c. CE 620). Muslims believe Muhammad was miraculously transported one night from Mecca to the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, whereupon he ascended to Heaven to meet previous prophets of Islam.[227][228] The first verse in the Qur'an's Surat al-Isra notes the destination of Muhammad's journey as al-Aqsa (the farthest) mosque,[229] in assumed reference to the location in Jerusalem. Today, the Temple Mount is topped by two Islamic landmarks intended to commemorate the event—al-Aqsa Mosque, derived from the name mentioned in the Qur'an, and the Dome of the Rock, which stands over the Foundation Stone, from which Muslims believe Muhammad ascended to Heaven.[230]

Culture

Although Jerusalem is known primarily for its religious significance, the city is also home to many artistic and cultural venues. The Israel Museum attracts nearly one million visitors a year, approximately one-third of them tourists.[231] The 20-acre (81,000 m2) museum complex comprises several buildings featuring special exhibits and extensive collections of Judaica, archaeological findings, and Israeli and European art. The Dead Sea scrolls, discovered in the mid-20th century in the Qumran caves near the Dead Sea, are housed in the Museum's Shrine of the Book.[232]

The Youth Wing, which mounts changing exhibits and runs an extensive art education program, is visited by 100,000 children a year. The museum has a large outdoor sculpture garden, and a scale-model of the Second Temple.[231] The Rockefeller Museum, located in East Jerusalem, was the first archaeological museum in the Middle East. It was built in 1938 during the British Mandate.[233][234]

Yad Vashem, Israel's national memorial to the victims of the Holocaust, houses the world's largest library of Holocaust-related information,[235] with an estimated 100,000 books and articles. The complex contains a state-of-the-art museum that explores the genocide of the Jews through exhibits that focus on the personal stories of individuals and families killed in the Holocaust and an art gallery featuring the work of artists who perished. Yad Vashem also commemorates the 1.5 million Jewish children murdered by the Nazis, and honors the Righteous among the Nations.[236] The Museum on the Seam, which explores issues of coexistence through art, is situated on the road dividing eastern and western Jerusalem.[237]

The Jerusalem Symphony Orchestra, established in the 1940s,[238] has appeared around the world.[238] Other arts facilities include the International Convention Center (Binyanei HaUma) near the entrance to city, where the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra plays, the Jerusalem Cinemateque, the Gerard Behar Center (formerly Beit Ha'am) in downtown Jerusalem, the Jerusalem Music Center in Yemin Moshe,[239] and the Targ Music Center in Ein Kerem. The Israel Festival, featuring indoor and outdoor performances by local and international singers, concerts, plays and street theater, has been held annually since 1961; for the past 25 years, Jerusalem has been the major organizer of this event. The Jerusalem Theater in the Talbiya neighborhood hosts over 150 concerts a year, as well as theater and dance companies and performing artists from overseas.[240] The Khan Theater, located in a caravansarai opposite the old Jerusalem train station, is the city's only repertoire theater.[241] The station itself has become a venue for cultural events in recent years, as the site of Shav'ua Hasefer, an annual week-long book fair, and outdoor music performances.[242] The Jerusalem Film Festival is held annually, screening Israeli and international films.[243]

The Ticho House, in downtown Jerusalem, houses the paintings of Anna Ticho and the Judaica collections of her husband, an ophthalmologist who opened Jerusalem's first eye clinic in this building in 1912.[244] Al-Hoash, established in 2004, is a gallery for the preservation of Palestinian art.[245]

in 1974 was founded the Jerusalem Cinematheque by Lia van Lear,. in 1981 he passed a to new building in Hebron rd. near to the Valley of Hinnom and the Old City with the foundation of the "National Israeli Film Archive".

Jerusalem was declared the Capital of Arab Culture in 2009.[246] Jerusalem is home to the Palestinian National Theatre, which engages in cultural preservation as well as innovation, working to rekindle Palestinian interest in the arts.[247] The Edward Said National Conservatory of Music sponsors the Palestine Youth Orchestra[248] which toured the Gulf states and other Middle East countries in 2009.[249] The Islamic Museum on the Temple Mount, established in 1923, houses many Islamic artifacts, from tiny kohl flasks and rare manuscripts to giant marble columns.[250] While Israel approves and financially supports Arab cultural activities, Arab Capital of Culture events were banned because they were sponsored by the Palestine National Authority.[246] In 2009, a four-day culture festival was held in the Beit 'Anan suburb of Jerusalem, attended by more than 15,000 people[251]

The Abraham Fund[252] and the Jerusalem Intercultural Center] (JICC)[253] promote joint Jewish-Palestinian cultural projects. The Jerusalem Center for Middle Eastern Music and Dance[254] is open to Arabs and Jews, and offers workshops on Jewish-Arab dialogue through the arts.[255] The Jewish-Arab Youth Orchestra performs both European classical and Middle Eastern music.[256]

In 2006, a 38 km (24 mi) Jerusalem Trail was opened, a hiking trail that goes to many cultural sites and national parks in and around Jerusalem.

In 2008, the Tolerance Monument, an outdoor sculpture by Czesław Dźwigaj, was erected on a hill between Jewish Armon HaNetziv and Arab Jebl Mukaber as a symbol of Jerusalem's quest for peace.[257]

Media

Jerusalem is the state broadcasting center in Israel. Office is located in Jerusalem and the Israel Broadcasting Authority TV and radio studios of her - Israel Channel, Israel Radio studios. City offices are also located in the Second Authority for Television and Radio with Israel Channel 2 and Israel Channel 10, part of the radio studios of BBC News, and post offices in Israel.

Local media entities are radio Jerusalem city, local newspapers such as Yedioth Jerusalem, Jerusalem time, and the whole city, and local newspapers in different neighborhood.

Economy

Historically, Jerusalem's economy was supported almost exclusively by religious pilgrims, as it was located far from the major ports of Jaffa and Gaza.[258] Jerusalem's religious landmarks today remain the top draw for foreign visitors, with the majority of tourists visiting the Western Wall and the Old City,[3] but in the past half-century it has become increasingly clear that Jerusalem's providence cannot solely be sustained by its religious significance.[258]

Although many statistics indicate economic growth in the city, since 1967 East Jerusalem has lagged behind the development of West Jerusalem.[258] Nevertheless, the percentage of households with employed persons is higher for Arab households (76.1%) than for Jewish households (66.8%). The unemployment rate in Jerusalem (8.3%) is slightly better than the national average (9.0%), although the civilian labor force accounted for less than half of all persons fifteen years or older—lower in comparison to that of Tel Aviv (58.0%) and Haifa (52.4%).[3] Poverty in the city has increased dramatically in recent years. According to a report by the Association for Civil Rights in Israel (ACRI), 78% of Palestinians in Jerusalem lived in poverty in 2012. This marks a steady increase from 2006 when 64% of Palestinians were in poverty. While the ACRI attributes the increase to the lack of employment opportunities, infrastructure and a worsening educational system, Ir Amim blames the legal status of Palestinians in Jerusalem.[259] In 2006, the average monthly income for a worker in Jerusalem was NIS5,940 (US$1,410), NIS1,350 less than that for a worker in Tel Aviv. [citation needed]

During the British Mandate, a law was passed requiring all buildings to be constructed of Jerusalem stone in order to preserve the unique historic and aesthetic character of the city.[117] Complementing this building code, which is still in force, is the discouragement of heavy industry in Jerusalem; only about 2.2% of Jerusalem's land is zoned for "industry and infrastructure." By comparison, the percentage of land in Tel Aviv zoned for industry and infrastructure is twice as high, and in Haifa, seven times as high.[3] Only 8.5% of the Jerusalem District work force is employed in the manufacturing sector, which is half the national average (15.8%). Higher than average percentages are employed in education (17.9% vs. 12.7%); health and welfare (12.6% vs. 10.7%); community and social services (6.4% vs. 4.7%); hotels and restaurants (6.1% vs. 4.7%); and public administration (8.2% vs. 4.7%).[260] Although Tel Aviv remains Israel's financial center, a growing number of high tech companies are moving to Jerusalem, providing 12,000 jobs in 2006.[261] Northern Jerusalem's Har Hotzvim industrial park is home to some of Israel's major corporations, among them Intel, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, Ophir Optronics and ECI Telecom. Expansion plans for the park envision one hundred businesses, a fire station, and a school, covering an area of 530,000 m2 (130 acres).[262]

Since the establishment of the State of Israel, the national government has remained a major player in Jerusalem's economy. The government, centered in Jerusalem, generates a large number of jobs, and offers subsidies and incentives for new business initiatives and start-ups.[258]

In 2010, Jerusalem was named the top leisure travel city in Africa and the Middle East by Travel + Leisure magazine.[263]

Transportation

Jerusalem is served by highly-developed communication infrastructures, making it a leading logistics hub for Israel.

The Jerusalem Central Bus Station, located on Jaffa Road, is the busiest bus station in Israel. It is served by Egged Bus Cooperative, which is the second-largest bus company in the world,[264] The Dan serves the Bnei Brak-Jerusalem route along with Egged, and Superbus serves the routes between Jerusalem, Modi'in Illit, and Modi'in-Maccabim-Re'ut. The companies operate from Jerusalem Central Bus Station. Arab neighborhoods in East Jerusalem and routes between Jerusalem and locations in the West Bank are served by the East Jerusalem Central Bus Station, a transportation hub located near the Old City's Damascus Gate. The Jerusalem Light Rail initiated service in August 2011. According to plans, the first rail line will be capable of transporting an estimated 200,000 people daily, and has 23 stops. The route is from Pisgat Ze'ev in the north via the Old City and city center to Mt. Herzl in the south.

Another work in progress[265] is a new high-speed rail line from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, which is scheduled to be completed in 2017. Its terminus will be an underground station (80 m (262.47 ft) deep) serving the International Convention Center and the Central Bus Station,[266] and is planned to be extended eventually to Malha station. Israel Railways operates train services to Malha train station from Tel Aviv via Beit Shemesh.[267][268]

Begin Expressway is one of Jerusalem's major north-south thoroughfares; it runs on the western side of the city, merging in the north with Route 443, which continues toward Tel Aviv. Route 60 runs through the center of the city near the Green Line between East and West Jerusalem. Construction is progressing on parts of a 35-kilometer (22 mi) ring road around the city, fostering faster connection between the suburbs.[269][270] The eastern half of the project was conceptualized decades ago, but reaction to the proposed highway is still mixed.[269]

Education

Jerusalem is home to several prestigious universities offering courses in Hebrew, Arabic and English. Founded in 1925, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem has been ranked among the top 100 schools in the world.[271] The Board of Governors has included such prominent Jewish intellectuals as Albert Einstein and Sigmund Freud.[118] The university has produced several Nobel laureates; recent winners associated with Hebrew University include Avram Hershko,[272] David Gross,[273] and Daniel Kahneman.[274] One of the university's major assets is the Jewish National and University Library, which houses over five million books.[275] The library opened in 1892, over three decades before the university was established, and is one of the world's largest repositories of books on Jewish subjects. Today it is both the central library of the university and the national library of Israel.[276] The Hebrew University operates three campuses in Jerusalem, on Mount Scopus, on Giv'at Ram and a medical campus at the Hadassah Ein Kerem hospital.

Al-Quds University was established in 1984[277] to serve as a flagship university for the Arab and Palestinian peoples. It describes itself as the "only Arab university in Jerusalem".[278] New York Bard College and Al-Quds University agreed to open a joint college in a building originally built to house the Palestinian Legislative Council and Yasser Arafat’s office. The college gives Master of Arts in Teaching degrees.[279] Al-Quds University resides southeast of the city proper on a 190,000 square metres (47 acres) Abu Dis campus.[277] Other institutions of higher learning in Jerusalem are the Jerusalem Academy of Music and Dance[280] and Bezalel Academy of Art and Design,[281] whose buildings are located on the campuses of the Hebrew University.

The Jerusalem College of Technology, founded in 1969, combines training in engineering and other high-tech industries with a Jewish studies program.[282] It is one of many schools in Jerusalem, from elementary school and up, that combine secular and religious studies. Numerous religious educational institutions and Yeshivot, including some of the most prestigious yeshivas, among them the Brisk, Chevron, Midrash Shmuel and Mir, are based in the city, with the Mir Yeshiva claiming to be the largest.[283] There were nearly 8,000 twelfth-grade students in Hebrew-language schools during the 2003–2004 school year.[3] However, due to the large portion of students in Haredi Jewish frameworks, only fifty-five percent of twelfth graders took matriculation exams (Bagrut) and only thirty-seven percent were eligible to graduate. Unlike public schools, many Haredi schools do not prepare students to take standardized tests.[3] To attract more university students to Jerusalem, the city has begun to offer a special package of financial incentives and housing subsidies to students who rent apartments in downtown Jerusalem.[284]

Schools for Arabs in Jerusalem and other parts of Israel have been criticized for offering a lower quality education than those catering to Israeli Jewish students.[285] While many schools in the heavily Arab East Jerusalem are filled to capacity and there have been complaints of overcrowding, the Jerusalem Municipality is currently building over a dozen new schools in the city's Arab neighborhoods.[286] Schools in Ras el-Amud and Umm Lison opened in 2008.[287] In March 2007, the Israeli government approved a 5-year plan to build 8,000 new classrooms in the city, 40 percent in the Arab sector and 28 percent in the Haredi sector. A budget of 4.6 billion shekels was allocated for this project.[288] In 2008, Jewish British philanthropists donated $3 million for the construction of schools in Arab East Jerusalem.[287] Arab high school students take the Bagrut matriculation exams, so that much of their curriculum parallels that of other Israeli high schools and includes certain Jewish subjects.[285]

Sports

The two most popular sports are football (soccer) and basketball.[289] Beitar Jerusalem Football Club is one of the most well known in Israel. Fans include political figures who often attend its games.[290] Jerusalem's other major football team, and one of Beitar's top rivals, is Hapoel Jerusalem F.C. Whereas Beitar has been Israel State Cup champion seven times,[291] Hapoel has won the Cup only once. Beitar has won the top league six times, while Hapoel has never succeeded. Beitar plays in the more prestigious Ligat HaAl, while Hapoel is in the second division Liga Leumit. Since its opening in 1992, Teddy Kollek Stadium has been Jerusalem's primary football stadium, with a capacity of 21,600.[292] The most popular Palestinian football club is Jabal Al Mukaber (since 1976) which plays in West Bank Premier League. The club hails from Mount Scopus at Jerusalem, part of the Asian Football Confederation, and plays at the Faisal Al-Husseini International Stadium at Al-Ram, across the West Bank Barrier.[293][294]

In basketball, Hapoel Jerusalem plays in the top division. The club has won the State Cup three times, and the ULEB Cup in 2004.[295]

The Jerusalem Half Marathon is an annual event in which runners from all over the world compete on a course that takes in some of the city's most famous sights. In addition to the 21.0975 kilometres (13.1094 mi) Half Marathon, runners can also opt for the shorter 10 km (6.2 mi) Fun Run. Both runs start and finish at the stadium in Givat Ram.[296][297]

Notable residents

- Ancient

- Abdi-Heba

- Melchizedek

- Araunah

- Zadok

- King David (c. 1040 BCE-c. 970 BCE), second king of the united Kingdom of Israel

- Solomon the Great (c. 1011 BCE-c. 931 BCE), a King of Israel

- Modern

- Naomi Ben-Ami (born 1960), Israeli government official and head of Lishkat Hakesher

- Amram Blau

- Rachel Bluwstein

- Trude Dothan (born 1923), archaeologist

- Shlomo Hillel

- William Holman Hunt

- Helena Kagan

- Ephraim Katzir (1916–2009), biophysicist and fourth President of Israel

- Teddy Kollek (1911–2007), mayor of Jerusalem and founder of the Jerusalem Foundation

- Dan Meridor

- Sallai Meridor

- Shlomo Moussaieff (1852-1922), a founder of the Bukharim neighborhood

- Uzi Narkiss

- Ezra Nawi

- Yoni Netanyahu (1946–76), commander of Sayeret Matkal; killed in action during Operation Entebbe

- Sari Nusseibeh (born 1949), writer and philosopher.

- Amos Oz (born 1939), writer, novelist, and journalist

- Herbert Plumer

- Natalie Portman (born 1981), actress

- Menachem Porush

- Yitzhak Rabin (1922–95), general and the fifth Prime Minister of Israel

- Reuven Rivlin

- Afif Safieh (born 1950), Palestinian diplomat

- Conrad Schick

- Nahman Shai

- Chemi Shalev

- Michael Sfard

- Menachem Ussishkin

- Matan Vilnai

- Yigael Yadin

- A.B. Yehoshua

- Rehavam Ze'evi

Twin towns and sister cities

See List of Israeli twin towns and sister cities

- New York City, United States (since 1993)[298][299]

- Prague, Czech Republic [300]

Partner city

- Marseille, France

See also

- Walls of Jerusalem

- Jerusalem Day (Yom Yerushalayim)

- Quds Day (Yawm al-Quds)

- List of places in Jerusalem

- List of songs about Jerusalem

Endnotes

| i. | ^ In other languages: official Arabic in Israel: أورشليم القدس Ûrshalîm-Al Quds (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); Russian: Иерусалим Ijerusalím; Armenian: Երուսաղեմ Erusaġem. |

| ii. | ^ Jerusalem is the capital under Israeli law. The presidential residence, government offices, supreme court and parliament (Knesset) are located there. The Palestinian Authority foresees East Jerusalem as the capital of its future state. The UN and most countries do not recognize Jerusalem as Israel's capital, taking the position that the final status of Jerusalem is pending future negotiations between Israel and the Palestinian Authority. Most countries maintain their embassies in Tel Aviv and its suburbs or suburbs of Jerusalem, such as Mevaseret Zion (see CIA Factbook and Template:PDFlink) See Positions on Jerusalem for more information. |

| iii. | ^ Statistics regarding the demographics of Jerusalem refer to the unified and expanded Israeli municipality, which includes the pre-1967 Israeli and Jordanian municipalities as well as several additional Palestinian villages and neighborhoods to the northeast. Some of the Palestinian villages and neighborhoods have been relinquished to the West Bank de facto by way of the Israeli West Bank barrier,[176] but their legal statuses have not been reverted. |

| iv. | ^ The website for Jerusalem is available in three languages—Hebrew, English, and Arabic. |

| v. | ^ a b Much of the information regarding King David's conquest of Jerusalem comes from Biblical accounts, but some modern-day historians have begun to give them credit due to a 1993 excavation.[301] |

| vi. | ^ Sources disagree on the timing of the creation of the Pact of Umar (Omar). Whereas some say the Pact originated during Umar's lifetime but was later expanded,[302][303] others say the Pact was created after his death and retroactively attributed to him.[304] Further still, other historians believe the ideas in the Pact pre-date Islam and Umar entirely.[305] |

References

- ^ a b c "Timeline for the History of Jerusalem". Jewish Virtual Library. American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise. Retrieved 16 April 2007.

- ^ Largest city:

- "... modern Jerusalem, Israel's largest city ..." (Erlanger, Steven. Jerusalem, Now, The New York Times, 16 April 2006.)

- "Jerusalem is Israel's largest city." ("Israel (country)[dead link]", Microsoft Encarta, 2006, p. 3. Retrieved 18 October 2006. Archived 31 October 2009.)

- "Since 1975 unified Jerusalem has been the largest city in Israel." ("Jerusalem"[dead link], Encyclopædia Britannica Online, 2006. Retrieved 18 October 2006. Archived 21 June 2008)

- "Jerusalem is the largest city in the State of Israel. It has the largest population, the most Jews and the most non-Jews of all Israeli cities." (Klein, Menachem. Jerusalem: The Future of a Contested City, New York University Press, 1 March 2001, p. 18. ISBN 0-8147-4754-X)

- "In 1967, Tel Aviv was the largest city in Israel. By 1987, more Jews lived in Jerusalem than the total population of Tel Aviv. Jerusalem had become Israel's premier city." (Friedland, Roger and Hecht, Richard. To Rule Jerusalem, University of California Press, 19 September 2000, p. 192. ISBN 0-520-22092-7).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Press Release: Jerusalem Day" (PDF). Central Bureau of Statistics. 24 May 2006. Retrieved 10 March 2007.

- ^ Jewish Birthrate Exceeds Arab in Jerusalem

- ^ a b "TABLE 3. – POPULATION(1) OF LOCALITIES NUMBERING ABOVE 2,000 RESIDENTS AND OTHER RURAL POPULATION ON 31/12/2008" (PDF). Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 26 October 2009.

- ^ "Local Authorities in Israel 2007, Publication #1295 – Municipality Profiles – Jerusalem" (PDF) (in Hebrew). Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 31 December 2007.

- ^ "Do We Divide the Holiest Holy City?". Moment Magazine. Archived from the original on 3 June 2008. Retrieved 5 March 2008.. According to Eric H. Cline’s tally in Jerusalem Besieged.

- ^ Ben-Arieh, Yehoshua (1984). Jerusalem in the 19th Century, The Old City. Yad Izhak Ben Zvi & St. Martin's Press. p. 14. ISBN 0-312-44187-8.

- ^ "Old City of Jerusalem and its Walls". Whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- ^ a b Since the 10th century BCE:[v]

- "Israel was first forged into a unified nation from Jerusalem some 3,000 years ago, when King David seized the crown and united the twelve tribes from this city... For a thousand years Jerusalem was the seat of Jewish sovereignty, the household site of kings, the location of its legislative councils and courts. In exile, the Jewish nation came to be identified with the city that had been the site of its ancient capital. Jews, wherever they were, prayed for its restoration." Roger Friedland, Richard D. Hecht. To Rule Jerusalem, University of California Press, 2000, p. 8. ISBN 0-520-22092-7

- "The Jewish bond to Jerusalem was never broken. For three millennia, Jerusalem has been the center of the Jewish faith, retaining its symbolic value throughout the generations." Jerusalem- the Holy City, Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 23 February 2003. Accessed 24 March 2007.

- "The centrality of Jerusalem to Judaism is so strong that even secular Jews express their devotion and attachment to the city, and cannot conceive of a modern State of Israel without it.... For Jews Jerusalem is sacred simply because it exists... Though Jerusalem's sacred character goes back three millennia...". Leslie J. Hoppe. The Holy City: Jerusalem in the theology of the Old Testament, Liturgical Press, 2000, p. 6. ISBN 0-8146-5081-3

- "Ever since King David made Jerusalem the capital of Israel 3,000 years ago, the city has played a central role in Jewish existence." Mitchell Geoffrey Bard, The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Middle East Conflict, Alpha Books, 2002, p. 330. ISBN 0-02-864410-7

- "For Jews the city has been the pre-eminent focus of their spiritual, cultural, and national life throughout three millennia." Yossi Feintuch, U.S. Policy on Jerusalem, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1987, p. 1. ISBN 0-313-25700-0

- "Jerusalem became the center of the Jewish people some 3,000 years ago" Moshe Maoz, Sari Nusseibeh, Jerusalem: Points of Friction – And Beyond, Brill Academic Publishers, 2000, p. 1. ISBN 90-411-8843-6