Vancouver: Difference between revisions

BOT--Reverting link addition(s) by 216.187.103.132 to revision 472382461 (http://vancouverlookout.wordpress.com/) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 150: | Line 150: | ||

}}<!-- Infobox ends --> |

}}<!-- Infobox ends --> |

||

'''Vancouver''' ({{IPAc-en|v|æ|n|ˈ|k|uː|v|ər}}) is a coastal seaport city on the mainland of [[British Columbia]], [[Canada]]. It is the hub of [[Greater Vancouver]], which, with over 2. |

'''Vancouver''' ({{IPAc-en|v|æ|n|ˈ|k|uː|v|ər}}) is a coastal seaport city on the mainland of [[British Columbia]], [[Canada]]. It is the hub of [[Greater Vancouver]], which, with over 2.4 million residents,<ref name=bcstats/> is the [[List of the 100 largest metropolitan areas in Canada|third most populous metropolitan area]] in the country (after [[Toronto]] and [[Montreal]]),<ref> |

||

{{cite web |url=http://www40.statcan.gc.ca/l01/cst01/demo05a-eng.htm |title=Population of census metropolitan areas (2006 Census boundaries)|publisher=Statistics Canada |accessdate=2011-10-10}} |

{{cite web |url=http://www40.statcan.gc.ca/l01/cst01/demo05a-eng.htm |title=Population of census metropolitan areas (2006 Census boundaries)|publisher=Statistics Canada |accessdate=2011-10-10}} |

||

</ref> |

</ref> |

||

and the most populous in [[Western Canada]]. The [[city proper]] has more than |

and the most populous in [[Western Canada]]. The [[city proper]] has more than 651,000 people,<ref name=bcstats> |

||

{{cite web |url=http://www.bcstats.gov.bc.ca/data/pop/pop/mun/ |

{{cite web |url=http://www.bcstats.gov.bc.ca/data/pop/pop/mun/SubProvincialEstimates_Current.pdf |title=BC Stats 2011 |date=January 2012 |accessdate=2012-01-24}} |

||

</ref> |

</ref> |

||

making it the [[List of the 100 largest municipalities in Canada by population|eighth largest]] among Canadian cities,<ref name=popdwell2006> |

making it the [[List of the 100 largest municipalities in Canada by population|eighth largest]] among Canadian cities,<ref name=popdwell2006> |

||

Revision as of 17:54, 24 January 2012

Vancouver | |

|---|---|

City | |

| City of Vancouver | |

Clockwise from top: Downtown Vancouver as seen from the southern shore of False Creek, The University Endowment Lands, Burrard Bridge, Canada Place, Lions Gate Bridge, The Millennium Gate (Chinatown), and a Totem pole in Stanley Park | |

| Nickname: | |

| Motto(s): "By Sea, Land, and Air We Prosper" | |

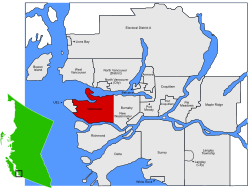

Location of Vancouver within Metro Vancouver in British Columbia, Canada | |

| Country | Canada |

| Province | British Columbia |

| Region | Lower Mainland |

| Regional District | Metro Vancouver |

| Incorporated | 1886 |

| Named for | Captain George Vancouver |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Gregor Robertson (Vision Vancouver) |

| • City Council | List of Councillors |

| • MPs (Fed.) | List of MPs |

| • MLAs (Prov.) | List of MLAs |

| Area | |

| • City | 114.67 km2 (44.27 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,878.52 km2 (1,111.40 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 2 m (7 ft) |

| Population | |

| • City | 578,041 (8th) |

| • Density | 5,039/km2 (13,050/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,116,581 (3rd) |

| • Demonym | Vancouverite |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| Postal code span | V5K to V6Z |

| Area code(s) | 604, 778 |

| NTS Map | 092G03 |

| GNBC Code | JBRIK |

| Website | City of Vancouver |

Vancouver (/vænˈkuːvər/) is a coastal seaport city on the mainland of British Columbia, Canada. It is the hub of Greater Vancouver, which, with over 2.4 million residents,[2] is the third most populous metropolitan area in the country (after Toronto and Montreal),[3] and the most populous in Western Canada. The city proper has more than 651,000 people,[2] making it the eighth largest among Canadian cities,[4] and the most densely populated Canadian city of over 25,000 residents, with 5,039 people per square kilometre in 2006.[1][4] The city is ethnically and linguistically diverse, with 52% for whom English is not their first language.[1][5]

The settlement of Gastown grew around a logging sawmill established in 1867, enlarging to become the townsite of Granville. With the announcement that the railhead would reach the site, it was renamed "Vancouver" and incorporated as a city in 1886. By 1887, the transcontinental railway was extended to the city to take advantage of its large natural seaport, which soon became a vital link in a trade route between the Orient, Eastern Canada, and London.[6][7] Port Metro Vancouver is the new name for the Port of Vancouver, which is now the busiest and largest in Canada, as well as the fourth largest port (by tonnage) in North America.[8] While forestry remains its largest industry, Vancouver is well known as an urban centre surrounded by nature, making tourism its second-largest industry.[9] Major film production studios in Vancouver and Burnaby have turned Metro Vancouver into the third-largest film production centre in North America after Los Angeles and New York City, earning it the film industry nickname, Hollywood North.[10][11]

Vancouver has ranked highly in worldwide "livable city" rankings for more than a decade according to business magazine assessments[12][13] and it was also acknowledged by Economist Intelligence Unit as the first city to rank among the top-ten of the world's most liveable cities for five straight years.[14] It has hosted many international conferences and events, including the 1954 British Empire and Commonwealth Games, Expo 86, and the World Police and Fire Games in 1989 and 2009. The 2010 Winter Olympics and 2010 Winter Paralympics were held in Vancouver and nearby Whistler, a resort community 125 km (78 mi) north of the city.[15]

History

Indigenous peoples

Archaeological records indicate the presence of Aboriginal people in the Vancouver area from 8,000 to 10,000 years ago.[17][18] The city is located in the traditional territories of the Squamish, Musqueam, and Tseil-Waututh (Burrard) peoples of the Coast Salish group.[19] They had villages in various parts of present day Vancouver, such as Stanley Park, False Creek, Kitsilano, Point Grey and near the mouth of the Fraser River.[18]

Exploration and contact

The first European to explore the coastline of present-day Point Grey and parts of Burrard Inlet was José María Narváez of Spain, in 1791, although one author contends that Francis Drake may have visited the area in 1579.[20] The city is named after George Vancouver, who explored the inner harbour of Burrard Inlet in 1792 and gave various places British names.[21][22][23]

The explorer and North West Company trader Simon Fraser and his crew were the first known people of European race to set foot on the site of the present-day city. In 1808, they travelled from the east down the Fraser River, perhaps as far as Point Grey.[24]

Early growth

The Fraser Gold Rush of 1858 brought over 25,000 men, mainly from California, to nearby New Westminster (founded February 14, 1859) on the Fraser River, on their way to the Fraser Canyon, bypassing what would become Vancouver.[25][26][27] Vancouver is among British Columbia's youngest cities;[28] the first European settlement in what is now Vancouver was not until 1862 at McLeery's Farm on the Fraser River, just east of the ancient village of Musqueam in what is now Marpole. A sawmill established at Moodyville (now the City of North Vancouver) in 1863, began the city's long relationship with logging. It was quickly followed by mills owned by Captain Edward Stamp on the south shore of the inlet. Stamp, who had begun lumbering in the Port Alberni area, first attempted to run a mill at Brockton Point, but difficult currents and reefs forced the relocation of the operation in 1867 to a point near the foot of Gore Street. This mill, known as the Hastings Mill, became the nucleus around which Vancouver formed. The mill's central role in the city waned after the arrival of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) in the 1880s. It nevertheless remained important to the local economy until it closed in the 1920s.[29]

The settlement which came to be called Gastown grew up quickly around the original makeshift tavern established by "Gassy" Jack Deighton in 1867 on the edge of the Hastings Mill property.[28][30] In 1870, the colonial government surveyed the settlement and laid out a townsite, renamed "Granville" in honour of the then-British Secretary of State for the Colonies, Lord Granville. This site, with its natural harbour, was selected in 1884[31] as the terminus for the Canadian Pacific Railway, to the disappointment of Port Moody, New Westminster and Victoria, all of which had vied to be the railhead. A railway was among the inducements for British Columbia to join the Confederation in 1871, but the Pacific Scandal and arguments over the use of Chinese labour delayed construction until the 1880s.[32]

Incorporation

The City of Vancouver was incorporated on April 6, 1886, the same year that the first transcontinental train arrived. CPR president William Van Horne arrived in Port Moody to establish the CPR terminus recommended by Henry John Cambie, and gave the city its name in honour of George Vancouver.[28] The Great Vancouver Fire on June 13, 1886, razed the entire city. The Vancouver Fire Department was established that year and the city quickly rebuilt.[29] Vancouver's population grew from a settlement of 1,000 people in 1881 to over 20,000 by the turn of the century and 100,000 by 1911.[33]

Vancouver merchants outfitted prospectors bound for the Klondike Gold Rush in 1898.[25] One of those merchants, Charles Woodward, had opened the first Woodward's store at Abbott and Cordova Streets in 1892 and, along with Spencer's and the Hudson's Bay department stores, formed the core of the city's retail sector for decades.[34]

The economy of early Vancouver was dominated by large companies such as the CPR, which fueled economic activity and led to the rapid development of the new city;[35] in fact the CPR was the main real estate owner and housing developer in the city. While some manufacturing did develop, natural resources became the basis for Vancouver's economy. The resource sector was initially based on logging and later on exports moving through the seaport, where commercial traffic constituted the largest economic sector in Vancouver by the 1930s.[36]

Twentieth century

The dominance of the economy by big business was accompanied by an often militant labour movement. The first major sympathy strike was in 1903 when railway employees struck against the CPR for union recognition. Labour leader Frank Rogers was killed by CPR police while picketing at the docks, becoming the movement's first martyr in British Columbia.[37] The rise of industrial tensions throughout the province led to Canada's first general strike in 1918, at the Cumberland coal mines on Vancouver Island.[38] Following a lull in the 1920s, the strike wave peaked in 1935 when unemployed men flooded the city to protest conditions in the relief camps run by the military in remote areas throughout the province.[39][40] After two tense months of daily and disruptive protesting, the relief camp strikers decided to take their grievances to the federal government and embarked on the On-to-Ottawa Trek,[40] but their protest was put down by force. The workers were arrested near Mission and interned in work camps for the duration of the Depression.[41]

Other social movements, such as the first-wave feminist, moral reform, and temperance movements were also influential in Vancouver's development. Mary Ellen Smith, a Vancouver suffragist and prohibitionist, became the first woman elected to a provincial legislature in Canada in 1918.[42] Alcohol prohibition began in the First World War and lasted until 1921, when the provincial government established control over alcohol sales, a practice still in place today.[43] Canada's first drug law came about following an inquiry conducted by the federal Minister of Labour and future Prime Minister, William Lyon Mackenzie King. King was sent to investigate damages claims resulting from a riot when the Asiatic Exclusion League led a rampage through Chinatown and Japantown. Two of the claimants were opium manufacturers, and after further investigation, King found that white women were reportedly frequenting opium dens as well as Chinese men. A federal law banning the manufacture, sale, and importation of opium for non-medicinal purposes was soon passed based on these revelations.[44]

Amalgamation with Point Grey and South Vancouver gave the city its final boundaries not long before it became the third-largest metropolis in the country. As of January 1, 1929, the population of the enlarged Vancouver was 228,193.[45]

Geography

Located on the Burrard Peninsula, Vancouver lies between Burrard Inlet to the north and the Fraser River to the south. The Strait of Georgia, to the west, is shielded from the Pacific Ocean by Vancouver Island. The city has an area of 114 km2 (44 sq mi), including both flat and hilly ground, and is in the Pacific Time Zone (UTC−8) and the Pacific Maritime Ecozone.[46] Until the city's naming in 1885, "Vancouver" referred to Vancouver Island, and it remains a common misconception that the city is located on the island.[47][48] The island and the city are both named after Royal Navy Captain George Vancouver (as is the city of Vancouver, Washington in the United States).

Vancouver has one of the largest urban parks in North America, Stanley Park, which covers 404.9 hectares (1001 acres).[49] The North Shore Mountains dominate the cityscape, and on a clear day scenic vistas include the snow-capped volcano Mount Baker in the state of Washington to the southeast, Vancouver Island across the Strait of Georgia to the west and southwest, and Bowen Island to the northwest.[50]

Ecology

The vegetation in the Vancouver area was originally temperate rain forest, consisting of conifers with scattered pockets of maple and alder, and large areas of swampland (even in upland areas, due to poor drainage).[51] The conifers were a typical coastal British Columbia mix of Douglas fir, Western red cedar and Western Hemlock.[52] The area is thought to have had the largest trees of these species on the British Columbia Coast. Only in Elliott Bay, Seattle did the size of trees rival those of Burrard Inlet and English Bay. The largest trees in Vancouver's old-growth forest were in the Gastown area, where the first logging occurred, and on the southern slopes of False Creek and English Bay, especially around Jericho Beach. The forest in Stanley Park was logged between the 1860s and 1880s, and evidence of old-fashioned logging techniques such as springboard notches can still be seen there.[53]

Many plants and trees growing throughout Vancouver and the Lower Mainland were imported from other parts of the continent and from points across the Pacific. Examples include the monkey puzzle tree, the Japanese Maple, and various flowering exotics, such as magnolias, azaleas, and rhododendrons. Some rhododendrons have grown to immense sizes,[citation needed] as have other species imported from harsher climates in Eastern Canada or Europe. The native Douglas Maple can also attain a tremendous size. Many of the city's streets are lined with flowering varieties of Japanese cherry trees donated from the 1930s onward by the government of Japan. These flower for several weeks in early spring each year. Other streets are lined with flowering chestnut, horse chestnut and other decorative shade trees.[54]

Climate

Vancouver is one of the warmest Canadian cities. Vancouver's climate is temperate by Canadian standards and is usually classified as Oceanic or Marine west coast, which under the Köppen climate classification system would be Cfb. The summer months are typically dry, with an average of only one in five days during July and August receiving precipitation. In contrast, precipitation falls during nearly half the days from November through March.[55]

Annual precipitation as measured at Vancouver International Airport in Richmond averages 1,199 millimetres (47.2 in), though this varies dramatically throughout the metropolitan area due to the topography and is considerably higher in the downtown area. In winter, a majority of days receive measurable precipitation. Summer months are drier and sunnier with moderate temperatures, tempered by sea breezes. The daily maximum averages 22 °C (72 °F) in July and August, with highs rarely reaching 30 °C (86 °F).[56]

The highest temperature ever recorded was 34.4 °C (93.9 °F) on July 30, 2009.[57][58]

On average, snow falls on eleven days per year, with three days receiving 6 cm (2.4 in) or more. Average yearly snowfall is 48.2 cm (19.0 in) but typically does not remain on the ground for long.[56]

Winters in Greater Vancouver are the fourth mildest of Canadian cities after nearby Victoria, Nanaimo and Duncan, all on Vancouver Island.[59]

| Climate data for Richmond (Vancouver International Airport) Climate ID: 1108447; coordinates 49°11′42″N 123°10′55″W / 49.19500°N 123.18194°W; elevation: 4.3 m (14 ft); 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1898–present[a] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high humidex | 17.2 | 18.0 | 20.3 | 24.7 | 33.7 | 38.4 | 38.3 | 35.9 | 33.0 | 27.2 | 21.1 | 16.6 | 38.4 |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.3 (59.5) |

18.4 (65.1) |

20.0 (68.0) |

26.1 (79.0) |

30.4 (86.7) |

33.3 (91.9) |

34.4 (93.9) |

33.3 (91.9) |

30.0 (86.0) |

25.0 (77.0) |

23.3 (73.9) |

15.0 (59.0) |

34.4 (93.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 6.8 (44.2) |

7.9 (46.2) |

10.1 (50.2) |

13.1 (55.6) |

16.9 (62.4) |

19.6 (67.3) |

22.4 (72.3) |

22.4 (72.3) |

19.1 (66.4) |

13.5 (56.3) |

9.3 (48.7) |

6.6 (43.9) |

14.0 (57.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.1 (39.4) |

4.7 (40.5) |

6.7 (44.1) |

9.4 (48.9) |

13.0 (55.4) |

15.8 (60.4) |

18.2 (64.8) |

18.2 (64.8) |

15.2 (59.4) |

10.3 (50.5) |

6.4 (43.5) |

3.9 (39.0) |

10.5 (50.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.4 (34.5) |

1.5 (34.7) |

3.3 (37.9) |

5.7 (42.3) |

9.0 (48.2) |

11.9 (53.4) |

13.9 (57.0) |

14.0 (57.2) |

11.2 (52.2) |

7.0 (44.6) |

3.6 (38.5) |

1.2 (34.2) |

7.0 (44.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −17.8 (0.0) |

−16.1 (3.0) |

−9.4 (15.1) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

0.6 (33.1) |

3.9 (39.0) |

6.1 (43.0) |

3.9 (39.0) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−6.1 (21.0) |

−14.3 (6.3) |

−17.8 (0.0) |

−17.8 (0.0) |

| Record low wind chill | −22.6 | −21.2 | −14.5 | −5.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −11.4 | −21.3 | −27.8 | −27.8 |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 174.0 (6.85) |

90.8 (3.57) |

106.4 (4.19) |

85.5 (3.37) |

59.1 (2.33) |

51.1 (2.01) |

34.1 (1.34) |

36.1 (1.42) |

51.9 (2.04) |

123.9 (4.88) |

174.6 (6.87) |

172.2 (6.78) |

1,159.5 (45.65) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 162.1 (6.38) |

84.6 (3.33) |

104.1 (4.10) |

85.2 (3.35) |

59.1 (2.33) |

51.1 (2.01) |

34.1 (1.34) |

36.1 (1.42) |

51.9 (2.04) |

123.7 (4.87) |

171.2 (6.74) |

155.8 (6.13) |

1,119.2 (44.06) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 12.3 (4.8) |

4.5 (1.8) |

2.6 (1.0) |

0.1 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.0) |

3.2 (1.3) |

13.9 (5.5) |

36.6 (14.4) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 20.0 | 15.5 | 17.6 | 15.3 | 12.7 | 11.6 | 6.2 | 6.4 | 8.6 | 15.4 | 19.6 | 20.5 | 169.5 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 18.8 | 14.7 | 17.3 | 15.3 | 12.7 | 11.6 | 6.2 | 6.4 | 8.6 | 15.4 | 19.3 | 19.7 | 166.0 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 2.7 | 1.2 | 0.84 | 0.12 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.04 | 0.64 | 1.9 | 7.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 15:00 LST) | 81.1 | 74.8 | 70.1 | 65.7 | 63.7 | 62.0 | 61.2 | 62.2 | 67.9 | 76.2 | 80.0 | 81.9 | 70.6 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 60.2 | 91.0 | 134.8 | 185.0 | 222.5 | 226.9 | 289.8 | 277.1 | 212.8 | 120.7 | 60.4 | 56.5 | 1,937.5 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 22.3 | 31.8 | 36.6 | 45.0 | 46.9 | 46.8 | 59.3 | 62.1 | 56.1 | 36.0 | 21.9 | 22.0 | 40.6 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Source 1: Environment and Climate Change Canada[62] (sun 1981–2010)[56][63][64][65][66][67][68][69][70][71][72][73][74] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas(UV)[75] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Canada Place, Vancouver | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.6 (60.1) |

16.4 (61.5) |

19.1 (66.4) |

23.9 (75.0) |

32.7 (90.9) |

30 (86) |

31.7 (89.1) |

31.7 (89.1) |

28.5 (83.3) |

24.2 (75.6) |

17 (63) |

15 (59) |

32.7 (90.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 6.8 (44.2) |

8.4 (47.1) |

10.6 (51.1) |

13.5 (56.3) |

16.8 (62.2) |

19.6 (67.3) |

22.0 (71.6) |

22.3 (72.1) |

19.0 (66.2) |

13.9 (57.0) |

9.3 (48.7) |

6.8 (44.2) |

14.1 (57.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.8 (40.6) |

5.9 (42.6) |

7.6 (45.7) |

10 (50) |

13.2 (55.8) |

15.9 (60.6) |

18.1 (64.6) |

18.3 (64.9) |

15.4 (59.7) |

11.1 (52.0) |

7.1 (44.8) |

4.8 (40.6) |

11 (52) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 2.7 (36.9) |

3.4 (38.1) |

4.6 (40.3) |

6.5 (43.7) |

9.5 (49.1) |

12.2 (54.0) |

14.1 (57.4) |

14.4 (57.9) |

11.6 (52.9) |

8.2 (46.8) |

4.8 (40.6) |

2.8 (37.0) |

7.9 (46.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −13.3 (8.1) |

−6.7 (19.9) |

−5 (23) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

1.1 (34.0) |

2.8 (37.0) |

2.8 (37.0) |

5 (41) |

1.7 (35.1) |

−3.2 (26.2) |

−9.9 (14.2) |

−15.6 (3.9) |

−15.6 (3.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 178.8 (7.04) |

183.8 (7.24) |

155.8 (6.13) |

117.9 (4.64) |

86.7 (3.41) |

69.9 (2.75) |

53.4 (2.10) |

50.8 (2.00) |

73.3 (2.89) |

147.8 (5.82) |

239.2 (9.42) |

231.3 (9.11) |

1,588.6 (62.54) |

| Source: Environment Canada[76] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

Urban planning

At 5,335 people per km2 (13,817.6 people per mi2) in 2006, Vancouver is the fourth most densely populated incorporated city in North America among those with a population above 500,000 — after New York City, San Francisco, and Mexico City. Urban planning in Vancouver is characterized by high-rise residential and mixed-use development in urban centres, as an alternative to sprawl.[77] This has been credited[by whom?] in contributing to the city's high rankings in livability.

Vancouver has been ranked one of the most livable cities in the world for more than a decade.[13] As of 2010, Vancouver has been ranked as having the 4th highest quality of living of any city on Earth.[78] In contrast, according to Forbes, Vancouver had the 6th most overpriced real estate market in the world and was second-highest in North America after Los Angeles in 2007.[79] Vancouver has also been ranked among Canada's most expensive cities in which to live.[80][81] Forbes has also ranked Vancouver as the tenth cleanest city in the world.[82]

This approach originated in the late 1950s, when city planners began to encourage the building of high-rise residential towers in Vancouver's West End,[83] subject to strict requirements for setbacks and open space to protect sight lines and preserve green space. The success of these dense but livable neighbourhoods led to the redevelopment of urban industrial sites, such as North False Creek and Coal Harbour, beginning in the mid-1980s. The result is a compact urban core that has gained international recognition for its "high amenity and 'livable' development".[84] More recently, the city has been debating "ecodensity"—ways in which "density, design, and land use can contribute to environmental sustainability, affordability, and livability."[85]

Architecture

The Vancouver Art Gallery is housed downtown in the neoclassical former courthouse built in 1906. It was designed by Francis Rattenbury, who also designed the British Columbia Parliament Buildings and the Empress Hotel in Victoria, and the lavishly decorated second Hotel Vancouver.[86] The 556-room Hotel Vancouver, opened in 1939 and the third by that name, is across the street with its copper roof. The Gothic-style Christ Church Cathedral, across from the hotel, opened in 1894 and was declared a heritage building in 1976.

There are several modern buildings in the downtown area, including the Harbour Centre, the Vancouver Law Courts and surrounding plaza known as Robson Square (designed by Arthur Erickson) and the Vancouver Library Square (designed by Moshe Safdie), reminiscent of the Colosseum in Rome, and the recently completed Woodward's building Redevelopment (designed by Gregory Henriquez). The original BC Hydro headquarters building (designed by Ron Thom and Ned Pratt) at Nelson and Burrard Streets is a modernist high-rise, now converted into the Electra condominiums.[87] Also notable is the "concrete waffle" of the MacMillan-Bloedel building on the north-east corner of the Georgia and Thurlow intersection.

A prominent addition to the city's landscape is the giant tent-frame Canada Place, the former Canada Pavilion from the 1986 World Exposition, which includes part of the Convention Centre, the Pan-Pacific Hotel, and a cruise ship terminal. Two modern buildings that define the southern skyline away from the downtown area are City Hall and the Centennial Pavilion of Vancouver Hospital, both designed by Townley and Matheson in 1936 and 1958 respectively.[88][89]

A collection of Edwardian buildings in the city's old downtown core were, in their day, the tallest commercial buildings in the British Empire. These were, in succession, the Carter-Cotton Building (former home of The Vancouver Province newspaper), the Dominion Building (1907) and the Sun Tower (1911), the former two at Cambie and Hastings Streets and the latter at Beatty and Pender Streets. The Sun Tower's cupola was finally exceeded as the Empire's tallest commercial building by the elaborate Art Deco Marine Building in the 1920s.[90] The Marine Building is known for its elaborate ceramic tile facings and brass-gilt doors and elevators, which make it a favourite location for movie shoots.[91] Topping the list of tallest buildings in Vancouver is Living Shangri-La at 201 metres (659 ft)[92] and 62 storeys. The second-tallest building in Vancouver is One Wall Centre at 150 metres (491 ft)[93] and 48 storeys, followed closely by the Shaw Tower at 149 metres (489 ft).[93]

Demographics

Canada's national statistics agency estimated the population of the Vancouver metropolitan area to be 2,328,000 as of July 1, 2009.[94] BC Stats estimated the population of the city proper to be 642,843 in 2010.[95] Approximately 73 percent of the people living in Metro Vancouver live outside the city.

Vancouver has been called a "city of neighbourhoods", each with a distinct character and ethnic mix.[96] People of English, Scottish, and Irish origins were historically the largest ethnic groups in the city,[97] and elements of British and Irish society and culture are still visible in some areas, particularly South Granville and Kerrisdale. Germans are the next-largest European ethnic group in Vancouver and were a leading force in the city's society and economy until the rise of anti-German sentiment with the outbreak of World War I in 1914.[7] Today the Chinese are the largest visible ethnic group in the city, with a diverse Chinese-speaking community, and several languages, including Cantonese and Mandarin.[29][98] Neighbourhoods with distinct ethnic commercial areas include the Chinatown, Punjabi Market, Little Italy, Greektown, and (formerly) Japantown.

Since the 1980s, immigration has dramatically increased, making the city more ethnically and linguistically diverse; 52% do not speak English as their first language.[1][5] Almost 30% of the city's inhabitants are of Chinese heritage.[99] In the 1980s, an influx of immigrants from Hong Kong in anticipation of the transfer of sovereignty from the United Kingdom to China, combined with an increase in immigrants from mainland China and previous immigrants from Taiwan, established in Vancouver one of the highest concentrations of ethnic Chinese residents in North America.[100] This arrival of Asian immigrants continued a tradition of immigration from around the world that had established Vancouver as the second-most popular destination for immigrants in Canada after Toronto.[101] Other significant Asian ethnic groups in Vancouver are South Asian (mostly Punjabi, usually referred to as Indo-Canadian), Filipino, Korean, Vietnamese, Japanese, Indonesian, and Cambodians. Despite increases in Latin American immigration to Vancouver in the 1980s and 90s, recent immigration has been comparatively low, and African immigration has been similarly stagnant (3.6% and 3.3% of total immigrant population, respectively.)[102] In 1981, less than 7% of the population belonged to a visible minority group.[103] By 2008, this proportion had grown to 51%.[104]

Prior to the Hong Kong diaspora of the 1990s, the largest non-British ethnic groups in the city were Irish and German, followed by Scandinavian, Italian, Ukrainian and Chinese. From the mid 1950s until the 1980s, many Portuguese immigrants came to Vancouver and the city now has the third-largest Portuguese population in Canada.[citation needed] Eastern Europeans, including Yugoslavs, Russians, Czechs, Poles, Romanians and Hungarians began immigrating after the Soviet takeover of Eastern Europe after World War II.[7] Greek immigration increased in the late 1960s and early 70s, with most settling in the Kitsilano area. Vancouver also has a significant aboriginal community of about 11,000 people.[105]

Vancouver has a large gay community[106] focused on the West End neighbourhood lining a certain stretch of Davie Street, recently officially designated as Davie Village,[107] though the gay community is omnipresent throughout West End and Yaletown areas. Vancouver is host to one of the country's largest annual gay pride parades.[108] British Columbia was the second Canadian jurisdiction (after Ontario) to legalize same-sex marriage.[109]

| Canadian Census Population Growth by decade[110][111] | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1891 | 1901 | 1911 | 1921 | 1931 | 1941 | 1951 | 1961 | 1971 | 1981 | 1991 | 2001 | 2006 | |||

| Vancouver | 13,709 | 26,133 | 100,401 | 117,217 | 246,593 | 275,353 | 344,833 | 384,522 | 426,256 | 414,281 | 471,644 | 545,671 | 578,041 | |||

| Greater Vancouver | 21,887 | 42,926 | 164,020 | 232,597 | 347,709 | 393,898 | 562,462 | 790,741 | 1,028,334 | 1,169,831 | 1,602,590 | 1,986,965 | 2,116,581 | |||

The largest religious group in Vancouver City is those with no religious affiliation, as is the case for the Vancouver CMA (Census Metropolitan Area), and for BC as a whole. Compared to the rest of Canada, the city of Vancouver has a lesser percentage of Catholics and Protestants, and almost seven times the percentage affiliated with Buddhism.

| Religion |

Total |

% |

Total |

% |

Total |

% |

Total |

% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vancouver City | Vancouver (CMA) | British Columbia | Canada | |||||

| Total | 539,630 | 100.0% | 1,967,480 | 100.0% | 3,868,875 | 100.0% | 29,639,035 | 100.0% |

| Catholic[1] | 102,315 | 19.0% | 364,790 | 18.5% | 675,320 | 17.5% | 12,936,910 | 43.6% |

| Protestant | 94,010 | 17.4% | 499,185 | 25.4% | 1,213,290 | 31.4% | 8,654,850 | 29.2% |

| Christian Orthodox | 9,090 | 1.7% | 26,520 | 1.3% | 35,655 | 0.9% | 479,620 | 1.6% |

| Christian,n.i.e.[2] | 23,600 | 4.4% | 101,620 | 5.2% | 200,340 | 5.2% | 780,450 | 2.6% |

| Muslim | 9,345 | 1.7% | 52,590 | 2.7% | 56,220 | 1.5% | 579,640 | 2.0% |

| Jewish | 9,620 | 1.8% | 17,270 | 0.9% | 21,230 | 0.5% | 329,995 | 1.1% |

| Buddhist | 37,140 | 6.9% | 74,550 | 3.8% | 85,540 | 2.2% | 300,345 | 1.0% |

| Hindu | 7,670 | 1.4% | 27,410 | 1.4% | 31,495 | 0.8% | 297,200 | 1.0% |

| Sikh | 15,200 | 2.8% | 99,000 | 5.0% | 135,310 | 3.5% | 278,410 | 0.9% |

| Eastern religions[3] | 1,250 | 0.2% | 5,580 | 0.3% | 9,975 | 0.3% | 37,550 | 0.1% |

| Other religions[4] | 2,455 | 0.5% | 6,195 | 0.3% | 16,205 | 0.4% | 63,975 | 0.2% |

| No religious affiliation[5] | 227,925 | 42.2% | 692,765 | 35.2% | 1,388,300 | 35.9% | 4,900,090 | 16.5% |

| Source:Canada 2001 Census[112] | ||||||||

|

[1] Includes Roman Catholic, Eastern Catholic, Polish National Catholic Church, Old Catholic | ||||||||

Economy

With its location on the Pacific Rim and at the western terminus of Canada's transcontinental highway and rail routes, Vancouver is one of the nation's largest industrial centres.[50] The Port of Vancouver, Canada's largest and most diversified, does more than C$75 billion in trade with over 130 different economies annually. Port activities generate $10.5 billion in gross domestic product and $22 billion in economic output.[113] Vancouver is also the headquarters of forest product and mining companies. In recent years, Vancouver has become an increasingly important centre for software development, biotechnology, aerospace, video game development, animation studios and a vibrant film industry.[114]

Vancouver's scenic location makes it a major tourist destination. Many visit to see the city's gardens, Stanley Park, Queen Elizabeth Park, VanDusen and the mountains, ocean, forest and parklands which surround the city. Each year over a million people pass through Vancouver on cruise ship vacations, often bound for Alaska.[114]

Vancouver is amongst the least affordable cities in which to live in the nation, with the highest housing prices in Canada. Several 2006 studies rank Vancouver as having the least affordable housing in Canada, ranking 13th least affordable in the world, up from 15th in 2005.[115][116][117] The city has adopted various strategies to reduce housing costs, including cooperative housing, legalized secondary suites, increased density and smart growth. As of April 2010, the average two-level home in Vancouver sold for a record high of $987,500, compared with the Canadian average of $365,141.[118]

Since the 1990s development of high-rise condominiums in the downtown peninsula has been financed, in part, by an inflow of capital from Hong Kong immigrants due to the former colony's 1997 handover to China.[citation needed] Such development has clustered in the Yaletown and Coal Harbour districts and around many of the SkyTrain stations to the east of the downtown.[114] The city's selection to co-host the 2010 Winter Olympics has also been a major influence on economic development. Concern has been expressed that Vancouver's increasing homelessness problem may be exacerbated by the Olympics because owners of single room occupancy hotels, which house many of the city's lowest income residents, have begun converting their properties in order to attract higher income residents and tourists.[119] Another significant international event held in Vancouver, the 1986 World Exposition, received over 20 million visitors and added $3.7 billion to the Canadian economy.[120] Some still-standing Vancouver landmarks, including the SkyTrain public transit system and Canada Place, were built as part of the exposition.[121]

Government

Vancouver, unlike other British Columbia municipalities, is incorporated under the Vancouver Charter.[122] The legislation, passed in 1953, supersedes the Vancouver Incorporation Act, 1921 and grants the city more and different powers than other communities possess under BC's Municipalities Act.

The civic government has been dominated by the centre-right Non-Partisan Association (NPA) since the Second World War, albeit with some significant centre-left interludes until 2008.[29] The NPA fractured over the issue of drug policy in 2002, facilitating a landslide victory for the Coalition of Progressive Electors (COPE) on a harm reduction platform. Subsequently, North America's first and only legal safe injection site was opened for the significant number of intravenous heroin users in the city.[123]

Vancouver is governed by the ten-member Vancouver City Council, a nine-member School Board, and a seven-member Park Board, all elected for three-year terms through an at-large system. Historically, in all levels of government, the more affluent west side of Vancouver has voted along conservative or liberal lines while the eastern side of the city has voted along left-wing lines.[124] This was reaffirmed with the results of the 2005 provincial election and the 2006 federal election.

Though polarized, a political consensus has emerged in Vancouver around a number of issues. Protection of urban parks, a focus on the development of rapid transit as opposed to a freeway system, a harm reduction approach to illegal drug use, and a general concern about community-based development are examples of policies that have come to have broad support across the political spectrum in Vancouver.

In the 2008 Municipal Election campaign, NPA incumbent mayor Sam Sullivan was ousted as mayoral candidate by the party in a close vote, which instated Peter Ladner as the new mayoral candidate for the NPA. Gregor Robertson, a former MLA for Vancouver-Fairview and head of Happy Planet, was the mayoral candidate for Vision Vancouver, the other main contender. Vision Vancouver candidate Gregor Robertson defeated Ladner by a considerable margin, nearing 20,000 votes. The balance of power was significantly shifted to Vision Vancouver, which held 7 of the 10 spots for councillor. Of the remaining three, COPE received 2 and the NPA 1. For park commissioner, 4 spots went to Vision Vancouver, 1 to the Green Party, 1 to COPE, and 1 to NPA. For school trustee, there were 4 Vision Vancouver seats, 3 COPE seats, and 2 NPA seats.[125]

There are 21 municipalities in Metro Vancouver, whose seat is in Burnaby. While each has a separate municipal government, Metro Vancouver oversees common services within the area such as water, sewage, transportation, and regional parks.

Provincial and federal representation

In the Legislative Assembly of British Columbia, Vancouver is represented by 11 Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs). There are currently six seats held by the BC Liberal Party and five by the BC New Democratic Party.[126]

In the Canadian House of Commons, Vancouver is represented by five Members of Parliament. In the most recent 2011 Federal Election, the NDP held on to two seats (Vancouver East and Vancouver Kingsway) while the Liberals retained two (Vancouver Quadra and Vancouver Centre), their only seats in BC. The Conservatives broke through by winning Vancouver South, their first win in the city since 1988.

In the 2004 federal elections, the Liberal Party of Canada won four seats and the federal New Democratic Party (NDP) one. In the 2006 federal elections, all the same Members of Parliament were re-elected. However, on February 6, 2006, David Emerson of Vancouver Kingsway defected to the Conservative Party, giving the Conservatives one seat in Vancouver. In the 2008 federal election, the NDP took the Vancouver Kingsway seat vacated by Emerson, giving the NDP two seats to the Liberals' three.[127][128]

Policing and crime

While most of the Lower Mainland is policed by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police's "E" Division, Vancouver operates the Vancouver Police Department, with a strength of 1,174 sworn members and an operating budget of $149 million in 2005.[129][130][131] Over 16% of the city's budget was spent on police protection in 2005.[132]

The Vancouver Police Department's operational divisions include a bicycle squad, a marine squad, and a dog squad. It also has a mounted squad, used primarily to patrol Stanley Park and occasionally the Downtown Eastside and West End, as well as for crowd control.[133] The police work in conjunction with civilian and volunteer run Community Police Centres.[134] In 2006, the police department established its own Counter Terrorism Unit. In 2005, a new transit police force, the Greater Vancouver Transportation Authority Police Service (now South Coast British Columbia Transportation Authority Police Service), was established with full police powers.

Although it is illegal, Vancouver police generally do not arrest people for possessing small amounts of marijuana.[135] In 2000 the Vancouver Police Department established a specialized drug squad, "Growbusters", to carry out an aggressive campaign against the city's estimated 4,000 hydroponic marijuana growing operations (or grow-ops) in residential areas.[136] As with other law enforcement campaigns targeting marijuana this initiative has been sharply criticized.[137]

As of 2008, Vancouver had the seventh highest crime rate, dropping 3 spots since 2005, among Canada's 27 census metropolitan areas.[138] However, as with other Canadian cities, the over-all crime rate has been falling "dramatically".[139] Vancouver's property crime rate is particularly high, ranking among the highest for major North American cities.[140] But even property crime dropped 10.5% between 2004 and 2005.[130] For 2006, Metro Vancouver had the highest rate of gun-related violent crime of any major metropolitan region in Canada, with 45.3 violent offences involving guns for every 100,000 people in Metro Vancouver, slightly higher than Toronto at 40.4 but far above the national average of 27.5.[141] A series of gang-related incidents in early 2009 escalated into what police have dubbed a gang war. Vancouver plays host to special events such as the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation conference, the Clinton-Yeltsin Summit, or the Symphony of Fire fireworks show that require significant policing. The 1994 Stanley Cup riot overwhelmed police and injured as many as 200 people.[142] A second riot took place following the 2011 Stanley Cup Finals.[143]

Military

Vancouver is the location of the Canadian Forces Land Force Western Area headquarters of the 39 Canadian Brigade Group, at Jericho Beach.[144] Local primary reserve units include The Seaforth Highlanders of Canada and The British Columbia Regiment (Duke of Connaught's Own), based at the Seaforth Armoury and the Beatty Street Drill Hall, respectively, and the 15th Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery.[145] The Naval Reserve Unit HMCS Discovery is based on Deadman's Island in Stanley Park.[146] RCAF Station Jericho Beach, the first air base in Western Canada, was taken over by the Canadian Army in 1947 when sea planes were replaced by long-range aircraft. Most of the base facilities were transferred to the City of Vancouver in 1969 and the area renamed "Jericho Park".[147]

Education

The Vancouver School Board enrolls more than 110,000 students in its elementary, secondary, and post-secondary institutions, making it the second-largest school district in the province.[148][149] The district administers about 74 elementary schools, 17 elementary annexes, 18 secondary schools, 7 adult education centres, 2 Vancouver Learn Network schools, all which include 18 French immersion, a Mandarin bilingual, a fine arts school, gifted, and Montessori.[148] More than 46 independent schools of a wide variety are also eligible for partial provincial funding and educate approximately 10% of pupils in the city.[150]

There are five public universities in the Greater Vancouver area, the largest being the University of British Columbia (UBC) and Simon Fraser University (SFU), with a combined enrolment of more than 80,000 undergraduates, graduates, and professional students in 2008.[151][152] UBC consistently ranks among the 40 best universities in the world, and is among the 20 best public universities,[153] and SFU ranked as the best comprehensive university in Canada by Maclean’s University Rankings in 2009[154] and among the 200 best universities in the world.[155] UBC's main campus is located on the University Endowment Lands on Point Grey, the tip of Burrard Peninsula, with the city-proper adjacent to the east. SFU's main campus is in Burnaby. Both also maintain campuses in Downtown Vancouver. The other public universities are Capilano University in North Vancouver, the Emily Carr University of Art and Design on Granville Island in Vancouver, and Kwantlen Polytechnic University with four campuses all outside the city proper. Five private institutions also operate in the region: Trinity Western University in Langley, and University Canada West, NYIT Canada, and Fairleigh Dickinson University and Columbia College (British Columbia) all in Vancouver.

Vancouver Community College and Langara College are publicly funded college-level institutions in Vancouver, as is Douglas College with three campuses outside the city. The British Columbia Institute of Technology in Burnaby provides polytechnic education. These are augmented by private institutions and other colleges in the surrounding areas of Metro Vancouver that provide career, trade, and university-transfer programs, while the Vancouver Film School provides one-year programs in film production and video game design.[156][157]

International students and English as a Second Language (ESL) students have been significant in the enrolment of these public and private institutions. For the 2008–2009 school year, 53% of Vancouver School Board's students spoke a language other than English at home.[149]

Arts and culture

Theatre, dance and film

Prominent theatre companies in Vancouver include the Arts Club Theatre Company on Granville Island, the Vancouver Playhouse Theatre Company, and Bard on the Beach. Smaller companies include Touchstone Theatre, Studio 58, and Carousel Theatre. Theatre Under the Stars produces shows in the summer at Malkin Bowl in Stanley Park. Annual festivals that are held in Vancouver include the PuSh International Performing Arts Festival in January and the Vancouver Fringe Festival in September.

The Scotiabank Dance Centre, a converted bank building on the corner of Davie and Granville, functions as a gathering place and performance venue for Vancouver-based dancers and choreographers.

The Vancouver International Film Festival, which runs for two weeks each September, shows over 350 films and is one of the larger film festivals in North America. The Vancouver International Film Centre venue, the Vancity Theatre, runs independent non-commercial films throughout the rest of the year, as do the Pacific Cinémathèque, the Festival Cinemas theatres, and the Hollywood and Rio theatres.

Libraries and museums

Libraries in Vancouver include the Vancouver Public Library with its main branch at Library Square, designed by Moshe Safdie. The central branch contains 1.5 million volumes. Altogether there are twenty-two branches containing 2.25 million volumes.[158]

The Vancouver Art Gallery has a permanent collection of nearly 10,000 items and is the home of a significant number of works by Emily Carr.[159] However, little or none of the permanent collection is ever on view.

In the Kitsilano district are the Vancouver Maritime Museum, the H. R. MacMillan Space Centre, and the Vancouver Museum, the largest civic museum in Canada. The Museum of Anthropology at UBC is a leading museum of Pacific Northwest Coast First Nations culture. A more interactive museum is Science World at the head of False Creek. The city also features a diverse collection of Public Art.

Visual art

The Vancouver School of conceptual[160] photography (often referred to as photoconceptualism)[161] is a term applied to a grouping of artists from Vancouver who achieved international recognition starting in the 1980s.[160] No formal "school" exists and the grouping remains both informal and often controversial[162] even among the artists themselves, who often resist the term.[162] Artists associated with the term include Jeff Wall, Ian Wallace, Ken Lum, Roy Arden,[161] Stan Douglas and Rodney Graham.[163]

Music and nightlife

Musical contributions from Vancouver include performers of classical, folk and popular music. The Vancouver Symphony Orchestra is the professional orchestra based in the city. The Vancouver Opera is a major opera company in the city. The city is home to a number of Canadian composers including Rodney Sharman, Jeffrey Ryan, and Alexina Louie.

The city produced a number of notable punk rock bands, including the pioneering hardcore band D.O.A.. Other early Vancouver punk bands included the Subhumans, the Young Canadians, the Pointed Sticks, and UJ3RK5.[164] When alternative rock became popular in the 1990s, several Vancouver groups rose to prominence, including 54-40, Odds, Moist, the Matthew Good Band and Econoline Crush. Recent successful Vancouver bands include Gob and Stabilo. Today, Vancouver is home to a number of popular independent bands such as The New Pornographers, Destroyer, Tegan and Sara, and independent labels including Nettwerk and Mint. Vancouver also produced influential metal band Strapping Young Lad and pioneering electro-industrial bands Skinny Puppy and Front Line Assembly; the latter's Bill Leeb is better known for founding ambient pop super-group Delerium. Other popular musical artists who made their mark from Vancouver include Bryan Adams, Sarah McLachlan, Heart, Prism, Trooper, Chilliwack, Payolas, Images in Vogue, Michael Bublé, Marianas Trench and Spirit of the West.[165]

Larger musical performances are usually held at venues such as Rogers Arena, Queen Elizabeth Theatre, BC Place Stadium or the Pacific Coliseum, while smaller acts are held at places such as the Commodore Ballroom, the Orpheum Theatre and the Vogue Theatre. The Vancouver Folk Music Festival and the Vancouver International Jazz Festival showcase music in their respective genres from around the world. Vancouver's Chinese population has produced several Cantopop stars. Similarly, various Indo-Canadian artists and actors have a profile in Bollywood or other aspects of India's entertainment industry.

Vancouver has a vibrant nightlife scene, whether it be food and dining, or bars and nightclubs. The Granville Entertainment District has the city's highest concentration of bars and nightclubs with closing times of 3am, in addition to various after-hours clubs open until late morning on weekends. The street can attract large crowds on weekends and is closed to traffic on such nights. Gastown is also a popular area for nightlife with many upscale restaurants and nightclubs, as well as the Davie Village which is centre to the city's gay and lesbian LGBT community.

Media

Vancouver is a major film and television production centre. Nicknamed Hollywood North, the city has been used as a film making location for nearly a century, beginning with the Edison Manufacturing Company.[166] In 2008 more than 260 productions were filmed in Vancouver, making it the third-largest film centre in North America - after Los Angeles and New York City - and second only to Los Angeles in television production in the world.[167][168][169]

A wide mix of local, national, and international newspapers are distributed in the city. The two major English-language daily newspapers are The Vancouver Sun and The Province. Also, two national newspapers distributed in the city are The Globe and Mail, which began publication of a "national edition" in B.C. in 1983 and recently expanded to include a three-page B.C. news section, and the National Post which centres around national news. Other local newspapers include 24H (a local free daily), the Vancouver franchise of the national free daily Metro, the twice-a-week Vancouver Courier, and the independent newspaper The Georgia Straight. Three Chinese language daily newspapers, Ming Pao, Sing Tao and World Journal cater to the city's large Cantonese and Mandarin speaking population. A number of other local and international papers serve other multicultural groups in the Lower Mainland.

Some of the local television stations include CBC, Citytv, CTV and Global BC. OMNI British Columbia produce daily newscasts in Cantonese, Mandarin, Punjabi and Korean, and weekly newscasts in Tagalog, as well as programs aimed at other cultural groups. Fairchild Group also has two television stations: Fairchild TV and Talentvision, serving Cantonese and Mandarin speaking audiences respectively.

Radio stations with news departments include CBC Radio One, CKNW and News 1130. The Franco-Columbian community is served by Radio-Canada outlets CBUFT channel 26 (Télévision de Radio-Canada), CBUF-FM 97.7 (Première Chaîne) and CBUX-FM 90.9 (Espace musique).

Media dominance is a frequently discussed issue in Vancouver as newspapers, The Vancouver Sun, The Province, the Vancouver Courier and other local newspapers such as the Surrey Now, the Burnaby Now and the Richmond News, are all owned by Postmedia Network.[170] The concentration of single owned corporate media has spurred alternatives, making Vancouver a centre for independent online media including The Tyee and NowPublic.,[171] as well as hyperlocal online media, like Vancouver Is Awesome,[172] which provide coverage of community events and local arts and culture.

Transportation

Vancouver's streetcar system began on June 28, 1890, and ran from the (first) Granville Street Bridge to Westminster Avenue (now Main Street and Kingsway). Less than a year later, the Westminster and Vancouver Tramway Company began operating Canada's first interurban line between the two cities and beyond to Chilliwack, with another line, the Lulu Island Railroad, from the Granville Street Bridge to Steveston via Kerrisdale, which encouraged residential neighbourhoods outside the central core to develop.[173] The British Columbia Electric Railway became the company that operated the urban and interurban rail system, until 1958 when its last vestiges were dismantled in favour of "trackless" trolley and gasoline/diesel buses.[174] Vancouver currently has the second-largest trolleybus fleet in North America, after San Francisco.

Successive city councils in the 1970s and 1980s prohibited the construction of freeways as part of a long term plan.[175] As a result, the only major freeway within city limits is Highway 1, which passes through the north-eastern corner of the city. While the number of cars in Vancouver proper has been steadily rising with population growth, the rate of car ownership and the average distance driven by daily commuters have fallen since the early 1990s.[176][177] Vancouver is the only major Canadian city with these trends. Despite the fact that the journey time per vehicle has increased by one-third and growing traffic mass, there are 7% fewer cars making trips into the downtown core.[176] Residents have been more inclined to live in areas closer to their interests, or use more energy-efficient means of travel, such as mass transit and cycling. This is, in part, the result of a push by city planners for a solution to traffic problems and pro-environment campaigns. Transportation demand management policies have imposed restrictions on drivers making it more difficult and expensive to commute while introducing more benefits for non-drivers.[176]

TransLink is responsible for roads and public transportation within Metro Vancouver. It provides a bus service, including the B-Line rapid bus service, a foot passenger and bicycle ferry service (known as SeaBus), an automated rapid transit service called SkyTrain, and West Coast Express commuter rail. Vancouver's SkyTrain system is currently running on three lines, the Millennium Line, the Expo Line and the Canada Line.[178]

Changes are being made to the regional transportation network as part of Translink's 10-Year Transportation Plan. The recently completed Canada Line, opened on August 17, 2009, connects Vancouver International Airport and the neighbouring city of Richmond with the existing SkyTrain system. The Evergreen Line is planned to link the cities of Coquitlam and Port Moody with the SkyTrain system by 2014. There are also plans to extend the SkyTrain Millennium Line west to UBC as a subway under Broadway and capacity upgrades and an extension to the Expo Line. Several road projects will be completed within the next few years, including a replacement for the Port Mann Bridge, as part of the Provincial Government's Gateway Program.[178]

Other modes of transport add to the diversity of options available in Vancouver. Inter-city passenger rail service is operated from Pacific Central Station by Via Rail to points east; Amtrak Cascades to Seattle; and Rocky Mountaineer rail tour routes. Small passenger ferries operating in False Creek provide commuter service to Granville Island, Downtown Vancouver and Kitsilano. Vancouver has a city-wide network of bicycle lanes and routes, which supports an active population of cyclists year-round. Cycling has become Vancouver's fastest growing mode of transportation.[179]

Vancouver is served by Vancouver International Airport (YVR), located on Sea Island in the City of Richmond, immediately south of Vancouver. Vancouver's airport is Canada's second-busiest airport,[180] and the second-largest gateway on the west coast of North America for international passengers.[181] HeliJet and float plane companies operate scheduled air service from Vancouver harbour and YVR south terminal. The city is also served by two BC Ferry terminals. One is to the northwest at Horseshoe Bay (in West Vancouver), and the other is to the south, at Tsawwassen (in Delta).[182]

Sports and recreation

The mild climate of the city and close proximity to ocean, mountains, rivers and lakes make the area a popular destination for outdoor recreation. Vancouver has over 1,298 hectares (3,200 acres) of parks, of which, Stanley Park, at 404 hectares (1,000 acres), is the largest.[183] The city has several large beaches, many adjacent to one another, extending from the shoreline of Stanley Park around False Creek to the south side of English Bay, from Kitsilano to the University Endowment Lands, (which also has beaches that are not part of the city proper). The 18 kilometres (11 mi) of beaches include Second and Third Beaches in Stanley Park, English Bay (First Beach), Sunset, Kitsilano Beach, Jericho, Locarno, Spanish Banks, Spanish Banks Extension, Spanish Banks West, and Wreck Beach. There is also a freshwater beach at Trout Lake. The coastline provides for many types of water sport, and the city is a popular destination for boating enthusiasts.[184]

Within a 20-to-30-minute drive from downtown Vancouver are the North Shore Mountains, with three ski areas: Cypress Mountain, Grouse Mountain, and Mount Seymour. Mountain bikers have created world-renowned trails across the North Shore. The Capilano River, Lynn Creek and Seymour River, also on the North Shore, provide opportunities to whitewater enthusiasts during periods of rain and spring melt, though the canyons of those rivers are more utilized for hiking and swimming than whitewater.[185]

Running races include the Vancouver Sun Run (a 10 km (6.2 mi) race) every April; the Vancouver Marathon, held every May; and the Scotiabank Vancouver Half-Marathon held every June. The Grouse Grind is a 2.9-kilometre (1.8 mi) climb up Grouse Mountain open throughout the summer and fall months, including the annual Grouse Grind Mountain Run. Hiking trails include the Baden-Powell Trail, an arduous 42-kilometre (26 mi) long hike from West Vancouver's Horseshoe Bay to Deep Cove in the District of North Vancouver.[186]

In 2009, Metro Vancouver hosted the World Police and Fire Games. Swangard Stadium, in the neighbouring city of Burnaby, hosted games for the 2007 FIFA U-20 World Cup.[15][187]

Vancouver, along with Whistler and Richmond, was the host city for the 2010 Winter Olympic and the Paralympic Games. On June 12, 2010, it played host to Ultimate Fighting Championship 115 (UFC 115) which was the fourth UFC event to be held in Canada (the other 3 were held in Montreal).

In 2011, Vancouver hosted the Grey Cup, the Canadian Football League (CFL) championship game which is awarded every year to a different city which has a CFL team. The BC Titans of the International Basketball League played their inaugural season in 2009, with home games at the Langley Event Centre.[188] Vancouver is a centre for the fast-growing sport of Ultimate. During the summer of 2008 Vancouver hosted the World Ultimate Championships.[189]

Vancouver has an adult obesity rate of 12% compared to the Canadian average of 23%. 51.8% of Vancouverites are overweight, making it the fourth thinnest city in Canada after Toronto, Montreal, and Halifax.[190][191]

| Professional Team | League | Sport | Venue | Established | Defunct | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vancouver Canucks | National Hockey League NHL |

Ice hockey | Rogers Arena | 1970 | – | 0 |

| BC Lions | Canadian Football League CFL |

Football | BC Place Stadium | 1954 | – | 6 |

| Vancouver Whitecaps FC | Major League Soccer MLS |

Association Football | BC Place Stadium | 2011 | - | 0 |

| Vancouver Canadians | Northwest League NWL |

Baseball (Single A Short Season) | Scotiabank Field at Nat Bailey Stadium | 2000 | - | 1 |

| Vancouver Whitecaps Women | W-League | Association Football | Swangard Stadium | 2003 | - | 2 |

| Vancouver Giants | Western Hockey League WHL |

Ice hockey | Pacific Coliseum | 2001 | – | 1 |

| BC Titans | International Basketball League IBL |

Basketball | Langley Event Centre | 2009 | 2011; Ceased operations | 0 |

| Vancouver Grizzlies | National Basketball Association NBA |

Basketball | Rogers Arena | 1995 | moved 2001 to Memphis |

0 |

Sister cities

The City of Vancouver was one of the first cities in Canada to enter into an international sister cities arrangement.[192] Special arrangements for cultural, social and economic benefits have been created with these sister cities.[50][193]

| City | Country | Year of Partnership |

|---|---|---|

| Odessa | Ukraine | 1944 |

| Yokohama | Japan | 1965[194] |

| Edinburgh | Scotland, United Kingdom | 1978 |

| Guangzhou | People's Republic of China | 1985 |

| Los Angeles | United States | 1986 |

References

- ^ a b c d "Census 2006 Community Profiles: Vancouver, City and CMA". Government of Canada. 2006. Retrieved October 10, 2011.

- ^ a b "BC Stats 2011" (PDF). January 2012. Retrieved January 24, 2012.

- ^ "Population of census metropolitan areas (2006 Census boundaries)". Statistics Canada. Retrieved October 10, 2011.

- ^ a b "Population and dwelling counts, for Canada and census subdivisions (municipalities), 2006 and 2001 censuses". Statistics Canada. Retrieved October 10, 2011.

- ^ a b "City Facts 2004" (PDF). City of Vancouver. 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 12, 2006. Retrieved June 9, 2011. 48.9% have neither English nor French as their first language.

- ^ Morley, A. (1974). Vancouver, from milltown to metropolis. Vancouver: Mitchell press [c9161]. Retrieved June 9, 2011.LCCN 64-0

- ^ a b c Norris, John M. (1971). Strangers Entertained. Vancouver, British Columbia Centennial '71 Committee. Retrieved June 9, 2011.LCCN 72-0

- ^ "Port Metro Vancouver Mid-Year Stats Include Bright Spots in a Difficult First Half for 2009". Port Metro Vancouver. July 31, 2009. Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- ^ "Overnight visitors to Greater Vancouver by volume, monthly and annual basis" (PDF). Vancouver Convention and Visitors Bureau. Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- ^ "Industry Profile". BC Film Commission. Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- ^

Gasher, Mike (2002). Hollywood North: The Feature Film Industry in British Columbia. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-0967-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Vancouver and Melbourne top city league". BBC News. October 4, 2002. Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- ^ a b Frary, Mark (June 8, 2009). "Liveable Vancouver". The Economist. Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- ^ Koranyi, Balazs (February 21, 2011). "Vancouver still world's most liveable city: survey". Reuters.

- ^ a b "Vancouver 2010 Schedule". Official 2010 Olympic Site. 2010. Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- ^ Smedman, Lisa (March 3, 2006). "History of Naming Vancouver's Streets: Hamilton's Legacy". Vancouver Courier. Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- ^ Thom, Brian (1996). "Stó:lo Culture – Ideas of Prehistory and Changing Cultural Relationships to the Land and Environment". Retrieved November 23, 2006.

- ^ a b

Carlson, Keith Thor (ed.) (2001). A Stó:lō-Coast Salish Historical Atlas. Vancouver, BC: Douglas & McIntyre. pp. 6–18. ISBN 978-1-55054-812-9.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ Barman, J. (2005). Stanley Park's Secret. Harbour Publishing. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-55017-346-8.

- ^ Bawlf, R. Samuel (2003). The Secret Voyage of Sir Francis Drake: 1577–1580. Walker & Company. ISBN 978-0-8027-1405-3.

- ^ The name Vancouver itself originates from the Dutch "van Coevorden", denoting somebody from Coevorden, Netherlands.

- ^

Davis, Chuck (1997). Greater Vancouver Book: An Urban Encyclopaedia. Surrey, BC: Linkman Press. pp. 34–36. ISBN 978-1-896846-00-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Davis, Chuck. "Coevorden". The History of Metropolitan Vancouver. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ "History of City of Vancouver". Caroun.com. Retrieved January 17, 2007.

- ^ a b Hull, Raymond (1974). Vancouver's Past. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-95364-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Donald J. Hauka (2003). McGowan's War. New Star Books. ISBN 1554200016.

- ^ Matthews, J.S. "Skit" (1936). Early Vancouver. City of Vancouver.

- ^ a b c Cranny, Michael (1999). Horizons: Canada Moves West. Scarborough, ON: Prentice Hall Ginn Canada. ISBN 978-0-13-012367-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Davis, Chuck (1997). The Greater Vancouver Book: An Urban Encyclopaedia. Surrey, British Columbia: Linkman Press. pp. 39–47. ISBN 1896846009.

- ^ "Welcome to Gastown". Gastown Business Improvement Society. March 28, 2008. Retrieved December 5, 2009.

- ^ "Chronology[1757–1884]".

- ^ Morton, James (1973). In the Sea of Sterile Mountains: The Chinese in British Columbia. Vancouver: J.J. Douglas. ISBN 978-0-88894-052-0.

- ^ Davis, Chuck (1997). Greater Vancouver Book: An Urban Encyclopaedia. Surrey, BC: Linkman Press. p. 780. ISBN 978-1896846002.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Our History: Acquisitions, Retail, Woodward's Stores Limited". Hudson's Bay Company. Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- ^ "British Columbia facts - economic history". Retrieved June 12, 2011.

- ^ McCandless, R. C. (1974). "Vancouver's 'Red Menace' of 1935: The Waterfront Situation". BC Studies (22): 68.

- ^ Phillips, Paul A. (1967). No Power Greater: A Century of Labour in British Columbia. Vancouver: BC Federation of Labour/Boag Foundation. pp. 39–41.

- ^ Phillips, Paul A. (1967). No Power Greater: A Century of Labour in British Columbia. Vancouver: BC Federation of Labour/Boag Foundation. pp. 71–74.

- ^ Manley, John (1994). "Canadian Communists, Revolutionary Unionism, and the 'Third Period': The Workers' Unity League," (PDF). Journal of the Canadian Historical Association, New Series. 5: 167–194.

- ^ a b Brown, Lorne (1987). When Freedom was Lost: The Unemployed, the Agitator, and the State. Montreal: Black Rose Books. ISBN 978-0-920057-77-3.

- ^ Schroeder, Andreas (1991). Carved From Wood: A History of Mission 1861–1992. Mission Foundation. ISBN 978-1-55056-131-9.

- ^ Robin, Martin (1972). The Rush for Spoils: The Company Province,. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-7710-7675-6.

- ^ Robin, Martin (1972). The Rush for Spoils: The Company Province,. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart. pp. 187–188. ISBN 978-0-7710-7675-6.

- ^ Catherine Carstairs (2000). "'Hop Heads' and 'Hypes':Drug Use, Regulation and Resistance in Canada," (PDF). University of Toronto. Retrieved June 9, 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Francis, Daniel (2004). L.D.:Mayor Louis Taylor and the Rise of Vancouver. Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press. p. 135. ISBN 978-1-55152-156-5.

- ^ "Pacific Maritime Ecozone". Environment Canada. April 11, 2005. Archived from the original on June 21, 2004. Retrieved December 1, 2009.

- ^ "Vancouver Is Not On Vancouver Island".

- ^ "Vancouver Island – "Victoria Island" and other Misconceptions".

- ^ "World66 – Vancouver Travel Guide". World 66. Retrieved October 18, 2006.

- ^ a b c "About Vancouver". City of Vancouver. November 17, 2009. Retrieved December 1, 2009.

- ^ "Stanley Park History". City of Vancouver. 2009. Retrieved December 1, 2009.

- ^ ""Lower Mainland Ecoregion": Narrative Descriptions of Terrestrial Ecozones and Ecoregions of Canada (#196)". Environment Canada. Archived from the original on January 27, 2007. Retrieved December 4, 2009.

- ^ "Stanley Park: Forest – Monument Trees". City of Vancouver. 2009. Retrieved December 1, 2009.

- ^ "History". Vancouver Cherry Blossom Festival. 2009. Archived from the original on May 3, 2009. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

- ^ Station Results: Vancouver City Hall, 1971-2000. Environment Canada. Retrieved 2011-11-21.

- ^ a b c "1981 to 2010 Canadian Climate Normals". Environment and Climate Change Canada. September 22, 2015. Climate ID: 1108447. Archived from the original on July 8, 2024. Retrieved May 9, 2016.

- ^ "Hottest day ever recorded in Vancouver". CBC News. July 29, 2009. Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- ^ "Temperature record broken in Lower Mainland — again". CBC News. July 30, 2009. Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- ^ "Weather Winners — Mildest Winters". Environment Canada. Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- ^ "Daily Data Report for October 1898". Environment and Climate Change Canada. Retrieved April 27, 2016.

- ^ "Monthly Data Report for 1937". Environment and Climate Change Canada. Retrieved May 12, 2016.

- ^ "Canadian Climate Normals 1991–2020". Environment and Climate Change Canada. Archived from the original on July 8, 2024. Retrieved June 12, 2024.

- ^ "Daily Data Report for March 1941". Canadian Climate Data. Environment and Climate Change Canada. Retrieved May 12, 2016.

- ^ "Daily Data Report for April 1934". Canadian Climate Data. Environment and Climate Change Canada. Retrieved May 12, 2016.

- ^ "Daily Data Report for September 1944". Canadian Climate Data. Environment and Climate Change Canada. Retrieved May 12, 2016.

- ^ "Daily Data Report for October 1934". Canadian Climate Data. Environment and Climate Change Canada. Retrieved May 12, 2016.

- ^ "Daily Data Report for December 1939". Canadian Climate Data. Environment and Climate Change Canada. Retrieved May 12, 2016.

- ^ "Daily Data Report for August 1910". Canadian Climate Data. Environment and Climate Change Canada. Retrieved May 12, 2016.

- ^ "Daily Data Report for September 1908". Canadian Climate Data. Environment and Climate Change Canada. Retrieved May 12, 2016.

- ^ "Daily Data Report for October 1935". Canadian Climate Data. Environment and Climate Change Canada. Retrieved May 12, 2016.

- ^ "Calculation Information" (PDF). Environment and Climate Change Canada. Retrieved May 12, 2016.

- ^ "Daily Data Report for November 2016". Canadian Climate Data. Environment and Climate Change Canada. Retrieved November 9, 2016.

- ^ "Daily Data Report for November 1898". Canadian Climate Data. Environment and Climate Change Canada. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- ^ "Daily Data Report for June 1925". Environment and Climate Change Canada. Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- ^ "Vancouver, Canada - Detailed climate information and monthly weather forecast". Weather Atlas. Yu Media Group. Retrieved July 6, 2019.

- ^ "Canadian Climate Normals 1971-2000 - Vancouver Harbour CS". September 2011.

- ^ Julie Bogdanowicz (August 2006). "Vancouverism". Canadian Architect. Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- ^ "Quality of Living worldwide city rankings 2010 – Mercer survey". Mercer. May 26, 2010.

- ^ Woolsey, Matt (August 24, 2007). "World's Most Overpriced Real Estate Markets". Forbes. Retrieved November 29, 2009.

- ^ vom Hove, Tann (June 17, 2008). "City Mayors: World's most expensive cities (EIU)". City Mayors Economics. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ Beauchesne, Eric (June 24, 2006). "Toronto pegged as priciest place to live in Canada". The Vancouver Sun. Retrieved November 29, 2009.

- ^ Malone, Robert (April 16, 2007). "Which Are The World's Cleanest Cities?". Forbes. Retrieved December 5, 2009.

- ^ Bula, Frances (September 6, 2007). "Some things worked: The best – or worst – planning decisions made in the Lower Mainland". Vancouver Sun. Canada.com. Retrieved December 4, 2009.

- ^ Hutton, T. (2008). The New Economy of the Inner City. London & New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-77134-4. Google Books link

- ^ "Vancouver EcoDensity Initiative". City of Vancouver. Archived from the original on May 13, 2009. Retrieved July 3, 2009.

- ^ Davis, Chuck. "Rattenbury". The History of Metropolitan Vancouver. Retrieved November 23, 2006.

- ^ The Electra, at vancouver.ca

- ^ "Townley, Matheson and Partners". Archives Association of British Columbia. 2009. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

- ^ Kalman, Harold (1974). Exploring Vancouver: Ten Tours of the City and its Buildings. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press. pp. 160–161. ISBN 978-0-7748-0028-0.

- ^ Kalman, Harold (1974). Exploring Vancouver: Ten Tours of the City and its Buildings. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press. pp. 22, 24, 78. ISBN 978-0-7748-0028-0.

- ^ "Marine Building". Archiseek. Retrieved November 23, 2006.

- ^ "Living Shangri-La". Emporis Buildings. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

- ^ a b "Vancouver High-rise buildings (in feet)". Emporis Buildings. Retrieved February 6, 2007.

- ^ "Population of census metropolitan areas". Statistics Canada. 2010. Retrieved September 3, 2010.

- ^ "2010 Sub-Provincial Population Estimates" (PDF). BC Stats. 201l. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ^ Thomas R. Berger (June 8, 2004). "A City of Neighbourhoods: Report of the 2004 Vancouver Electoral Reform Commission" (PDF). City of Vancouver.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Population by selected ethnic origins, by census metropolitan areas (2006 Census)". Statistics Canada. 2006. Retrieved December 1, 2009.

- ^ "Visible minorities (2006 census)". Statistics Canada. Retrieved December 1, 2009.

- ^ "Visible minority". Statistics Canada. July 24, 2009. Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- ^ Cernetig, Miro (June 30, 2007). "Chinese Vancouver: A decade of change". Vancouver Sun. Canada. Retrieved January 25, 2010.

- ^ "Canada's ethnocultural portrait: Canada". Statistics Canada. 2001. Retrieved January 28, 2007.

- ^ Hiebert, D., (June 2009). "The Economic Integration of Immigrants in Metropolitan Vancouver". IRPPChoices 15 (7), p. 6. Retrieved: 2009-07-13.

- ^ Pendakur, Krishna (December 13, 2005). "Visible Minorities and Aboriginal Peoples in Vancouver's Labour Market". Human Resources and Skills Development Canada. Archived from the original on October 16, 2008. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ Hamilton, Graeme (April 3, 2008). "Visible minorities the new majority". National Post. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ "Community Highlights for Vancouver". Statistics Canada. February 1, 2007. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ "Gay U.S. couples can't get divorces for Canadian marriages". CBC News. September 25, 2009. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ Burrows, Matthew (July 31, 2008). "Gay clubs build community in Vancouver". The Georgia Straight. Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- ^ Weichel, Andrew (August 2, 2009). "Milk protégé praises Vancouver Pride celebration". CTV News. Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- ^ "Same-Sex rights: Canada timeline". CBC News. March 1, 2007. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ "City of Vancouver Population" (PDF). Vancouver Public Library. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 10, 2007. Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- ^ "British Columbia Municipal and Regional District 2006 Census Total Population Results". BC Stats. 2006 Census. Retrieved 2011-06-09.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Religion Statistics in Vancouver, in BC, in Canada". Select Another Region for other columns

- ^ "Facts and Stats". Vancouver Port Authority. 2009. Retrieved December 1, 2009.

- ^ a b c "Economy". Vancouver City Guide. Retrieved July 11, 2009.

- ^ Bula, Frances (January 22, 2007). "Vancouver is 13th least affordable city in world". Vancouver Sun. Retrieved January 25, 2010.

- ^ "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey: 2006" (PDF). Wendell Cox Consultancy. Retrieved November 12, 2006.

- ^ "Housing Affordability" (PDF). RBC Financial Group. Retrieved September 27, 2006.

- ^ "Survey of Vancouver housing price increase exceeds rest of Canada". BIV Daily Business News. Business in Vancouver. April 9, 2010. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- ^ "Homelessness could triple by 2010: report". CBC News. September 21, 2006. Retrieved January 25, 2010.

- ^ O'Leary, Kim Patrick. "Expo 86". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved March 29, 2011.