Benzodiazepine

| Benzodiazepines |

|---|

|

The benzodiazepines (Template:Pron-en, often abbreviated to "benzos") are a class of psychoactive drugs with varying hypnotic, sedative, anxiolytic (anti-anxiety), anticonvulsant, muscle relaxant and amnesic properties, which are mediated by slowing down the central nervous system.[1] Benzodiazepines are useful in treating anxiety, insomnia, agitation, seizures, and muscle spasms, as well as alcohol withdrawal. They can also be used before certain medical procedures such as endoscopies or dental work where tension and anxiety are present, and prior to some unpleasant medical procedures in order to induce sedation and amnesia[2] for the procedure. Another use is to counteract anxiety-related symptoms upon initial use of SSRIs and other antidepressants, or as an adjunctive treatment. Recreational stimulant users often use benzodiazepines as a means of "coming down". Benzodiazepines are also used to treat the panic that can be caused by hallucinogen intoxication.[3][4]

Benzodiazepines can cause a physical dependence and a benzodiazepine addiction to develop and upon cessation of long term use a benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome can occur.[5]

History

The first benzodiazepine, chlordiazepoxide (Librium) was discovered serendipitously in 1954 by the Austrian scientist Leo Sternbach (1908–2005), working for the pharmaceutical company Hoffmann–La Roche. Chlordiazepoxide was synthesised from work on a chemical dye, quinazolone-3-oxides. Initially, he discontinued his work on the compound Ro-5-0690, but he "rediscovered" it in 1957 when an assistant was cleaning up the laboratory. Although initially discouraged by his employer, Sternbach conducted further research that revealed the compound was a very effective tranquilizer. Tests revealed that the compound had hypnotic, anxiolytic and muscle relaxant effects. Three years later chlordiazepoxide was marketed as a therapeutic benzodiazepine medication under the brand name Librium. Following chlordiazepoxide, in 1963 diazepam hit the market under the brand name Valium, followed by many further benzodiazepine compounds which were introduced over the subsequent years and decades.[6]

Dr. Carl F. Essig of the Addiction Research Center of the National Institute of Mental Health spoke at a symposium on drug abuse at an annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, in December 1963. He named meprobamate, glutethimide, ethinamate, ethchlorvynol, methyprylon, and chlordiazepoxide as drugs whose usefulness can hardly be questioned. However, Essig labeled these newer products as drugs of addiction, like barbiturates, whose habit-forming qualities were more widely-known. He mentioned a 90-day study of chlordiazepoxide, which concluded that the automobile accident rate among 68 users was ten times higher than normal. Participants' daily dosage ranged from 5 to 100 milligrams.[7]

A related class of drugs that also work on the benzodiazepine receptors, the nonbenzodiazepines, has recently been introduced.[8] Nonbenzodiazepines are molecularly distinct from benzodiazepines and have similar risks and benefits to those of benzodiazepines. There have been suggestions that they may have a better side effect profile with less dependence potential. However, this is controversial and disputed by bodies such as the National Institute for Clinical Excellence.[9][10]

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

Benzodiazepines produce a range of effects from depressing to stimulating the central nervous system via modulating the GABAA receptor, the most prevalent inhibitory receptor within the brain. The subset of GABAA receptors that also bind benzodiazepines are referred to as benzodiazepine receptors (BzR). The GABAA receptor is composed of five subunits, most commonly two α's, two β's, and one γ (α2β2γ). For each subunit, multiple subtypes exist (α1-6, β1-3, and γ1-3). GABAA receptors that are made up of different combinations of subunit subtypes have different properties, different distributions within the brain, and different activities relative to pharmacological and clinical effects.

Benzodiazepines bind at the interface of the α and γ subunits on the GABAA receptor. Benzodiazepine binding also requires that alpha subunits contain a histidine amino acid residue, (i.e., α1, α2, α3 and α5 containing GABAA receptors). For this reason, benzodiazepines show no affinity for GABAA receptors containing α4 and α6 subunits, which contain an arginine instead of a histidine residue. Other sites on the GABAA receptor also bind neurosteroids, barbiturates and certain anesthetics.[11] Individual types of subunits are expressed more densely in certain brain regions and thus modulation of certain subunits produces certain therapeutic as well as adverse effects of benzodiazepines. The α4 and α6 are expressed in very low numbers in the brain.[12]

The binding of GABA to the GABA binding site increases the binding affinity of benzodiazepines for their binding site.[13] Once bound to the BzR, the benzodiazepine ligand locks the BzR into a conformation in which it has a much higher affinity for the GABA neurotransmitter than otherwise. This increases the frequency of opening of the associated chloride ion channel and hyperpolarizes the membrane of the associated neuron. This potentiates the inhibitory effect of the available GABA, leading to sedatory and anxiolytic effects. As mentioned above, different benzodiazepines can have different affinities for BzRs made up of different collection of subunits. For instance, benzodiazepines with high activity at the α1 (temazepam, triazolam, nitrazepam, etc) are associated with sedation, whereas those with higher affinity for GABAA receptors containing α2 and/or α3 subunits (diazepam, clonazepam, bromazepam, etc) have good anti-anxiety activity.[14] Benzodiazepines also bind to glial cell membranes.[15]

Some compounds lie somewhere between being full agonists and neutral antagonists, and are termed either partial agonists or partial antagonists. There has been interest in partial agonists for the BzR, with evidence that complete tolerance may not occur with chronic use, with partial agonists demonstrating continued anxiolytic properties with reduced sedation, dependence, and withdrawal problems.[16]

The anticonvulsant properties of benzodiazepines may be in part or entirely due to binding to voltage-dependent sodium channels rather than benzodiazepine receptors. Sustained repetitive firing seems to be limited by benzodiazepines effect of slowing recovery of sodium channels from inactivation.[17]

Benzodiazepine receptors also appear in a number of non nervous-system tissues and are mainly of the peripheral benzodiazepine receptor (PBRs) type. These peripheral benzodiazepine receptors are not coupled (or "attached") to GABAA receptors. These are found in various tissues such as heart, liver, adrenal, and testis, as well as hemopoietic and lymphatic cells.[18] In lymphatic tissues, they modulate apoptosis of thymocytes via reduction of mitochondrial transmembrane potential.[19] PBRs have many other actions on immune cells including modulation of oxidative bursts by neutrophils and macrophages, and inhibition of macrophage secretion of cytokines inhibition of the proliferation of lymphoid cells and secretion of cytokines by macrophages.[20]

Duration of action

Benzodiazepines are commonly divided into three groups by their half-lives: Short-acting compounds have a half-life of less than 12 hours, and have few residual effects if taken before bedtime, but rebound insomnia may occur and they might cause wake-time anxiety. Intermediate-acting compounds have a half-life of 12–24 hours, may have residual effects in the first half of the day. Rebound insomnia however is more common upon discontinuation of short-acting benzodiazepines. Daytime withdrawal symptoms are also a problem with prolonged usage of short-acting benzodiazepines, including daytime anxiety. Long-acting compounds have a half-life greater than 24 hours.[21][22] Strong sedative effects typically persist throughout the next day if long-acting preparations are used for insomnia. Accumulation of the compounds in the body may occur. The elimination half-life may greatly vary between individuals, especially the elderly. Shorter-acting compounds with a fast rate of absorption and a high receptor affinity are usually best for their hypnotic effects, whereas moderate to longer-acting compounds with slower rates of absorption and a weaker receptor affinity are usually better for their anxiolytic effects. Benzodiazepines with shorter half-lives tend to be able to produce tolerance and addiction quicker, as the drug does not last in the system for as long, with resultant interdose withdrawal phenomenon and next-dose craving. Although short-acting drugs are more commonly prescribed for insomnia, there are exceptions to the rules, such as alprazolam being prescribed as an anxiolytic more than a hypnotic, despite possessing a short half-life.

Benzodiazepines and their therapeutic uses

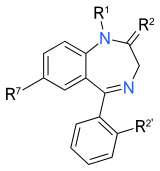

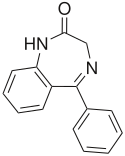

The core chemical structure of "classical" benzodiazepine drugs is a fusion between the benzene and diazepine ring systems. Many of these drugs contain the 5-phenyl-1,3-dihydro-1,4-benzodiazepin-2-one substructure (see figure to the above right). Benzodiazepines are molecularly similar to several groups of drugs, some of which share similar pharmacological properties, including the quinazolinones, hydantoines, succinimides, oxazolidinediones, barbiturates and glutarimides.[23][24] Most benzodiazepines are administered orally; however, administration can also occur intravenously, intramuscularly, sublingually or as a suppository. Benzodiazepines have a number of therapeutic uses, are well-tolerated, and are very safe and effective drugs in the short term for a wide range of conditions.

Anticonvulsants

| Main anticonvulsant benzodiazepines |

|---|

Benzodiazepines are potent anticonvulsants and have life-saving properties in the acute management of status epilepticus. The most commonly-used benzodiazepines for seizure control are lorazepam and diazepam. A meta-analysis of 11 clinical trials concluded that lorazepam was superior to diazepam in treating persistent seizures.[25] Although diazepam is much longer-acting than lorazepam, lorazepam has a more prolonged anticonvulsant effect. This is because diazepam is very lipid-soluble and highly protein-bound, and has a very large distribution of unbound drug, resulting in diazepam's having only a 20– to 30-minute duration of action against status epilepticus. Lorazepam, however, has a much smaller volume of distribution of unbound drug, which results in a more prolonged duration of action against status epilepticus. Lorazepam can therefore be considered superior to diazepam, at least in the initial stages of treatment of status epilepticus.[26]

Anxiolytics

| Main anxiolytic benzodiazepines |

|---|

Benzodiazepines possess anti-anxiety properties and can be useful for the short-term treatment of severe anxiety. Like the anticonvulsants, they tend to be mild, well tolerated, and extremely safe. Benzodiazepines are usually administered orally for the treatment of anxiety; however, occasionally lorazepam or diazepam may be given intravenously for the treatment of panic attacks.[27]

A panel of over 50 peer-nominated internationally recognized experts in the pharmacotherapy of anxiety and depression judged the benzodiazepines, especially combined with an antidepressant, as the mainstays of pharmacotherapy for anxiety disorders.[28][29][30][31]

Despite increasing focus on the use of antidepressants and other agents for the treatment of anxiety, benzodiazepines have remained a mainstay of anxiolytic pharmacotherapy due to their robust efficacy, rapid onset of therapeutic effect, and generally favorable side effect profile.[32] Treatment patterns for psychotropic drugs appear to have remained stable over the past decade, with benzodiazepines being the most commonly used medication for panic disorder.[33]

Insomnia

| Main hypnotic benzodiazepines |

|---|

Certain benzodiazepines are strictly prescribed for the short-term management of mild (flurazepam, quazepam, estazolam), moderate (lormetazepam, midazolam, loprazolam, brotizolam, nitrazepam), and severe or debilitating (triazolam, nimetazepam, temazepam, flunitrazepam, flutoprazepam) insomnia. Hypnotic benzodiazepines have strong sedative effects, are typically the most rapid-acting benzodiazepines, and have strong receptor affinity. In addition, many of the hypnotics are powerful anticonvulsants (nitrazepam, nimetazepam, temazepam, and flutoprazepam) and all are very strong anxiolytics and amnesic agents. Longer-acting benzodiazepines, such as nitrazepam or quazepam, have side-effects that may persist into the next day, whereas the more intermediate-acting benzodiazepines (for example, temazepam or loprazolam) may have less "hangover" effects the next day.[34] Benzodiazepine hypnotics should be reserved for short-term courses to treat acute conditions, as tolerance and dependence may occur if these benzodiazepines are taken regularly for more than a few weeks.

Premedication before procedures

Benzodiazepines can be very beneficial as premedication before surgery, especially in those that are anxious. Usually administered a couple of hours before surgery, benzodiazepines will bring about anxiety relief and also produce amnesia. Amnesia can be useful in this situation, as patients will not be able to remember any unpleasantness from surgery.[35] Diazepam or temazepam can be utilized in patients who are particularly anxious about dental procedures.[35] Alternatively nitrous oxide can be administered in dental phobia due to its sedative and dissociative effects, its fast onset of action, and its extremely short duration of action.

Intensive care

Benzodiazepines can be very useful in intensive care to sedate patients receiving mechanical ventilation, or those in extreme distress or severe pain. Caution should be exercised in this situation due to the occasional scenario of respiratory depression, and benzodiazepine overdose treatment facilities should be available.[35]

Alcohol dependence

Benzodiazepines have been shown to be safe and effective, particularly for preventing or treating seizures and delirium, and are the preferred agents for treating the symptoms of alcohol withdrawal syndrome.[36] The choice of agent is based on pharmacokinetics. The most commonly used benzodiazepines in the management of alcohol withdrawal are diazepam (Valium) and chlordiazepoxide (Librium), two long-acting agents, and lorazepam (Ativan) and oxazepam (Serax), two intermediate-acting agents. The long half-life of diazepam and chlordiazepoxide make withdrawal smoother, and rebound withdrawal symptoms are less likely to occur. The two intermediate-acting agents have excellent records of efficacy. Chlordiazepoxide is the benzodiazepine of choice in uncomplicated alcohol withdrawal.[37] Oxazepam is the most commonly used benzodiazepine in managing alcohol withdrawal symptoms. It is the benzodiazepine of choice in treating severe alcohol withdrawal symptoms, and it is often used in patients that metabolize medications less effectively, particularly the elderly and those with cirrhosis. Lorazepam is the only benzodiazepine with predictable intramuscular absorption (if intramuscular administration is necessary) and it is the most effective in preventing and controlling seizures. Phenazepam is another benzodiazepine that has been used to treat alcohol withdrawal with excellent efficacy. In Russia, it is preferred over diazepam in the management of alcohol withdrawal.

Muscular disorders

Benzodiazepines are well known for their strong muscle-relaxing properties, and can be useful in the treatment of muscle spasms, for example, Tetanus or spastic disorders[38] and Restless legs syndrome. Clonazepam has been used with efficacy in the treatment of some forms of Tourette's syndrome (with symptoms more on the side of motor tics, as opposed to vocal tics, although almost any tic can be preceded by, and intensify with stress; therapy for Tourette's syndrome is highly individualized.) Many people experiencing tremors may be helped with benzodiazepines.

Acute mania

Mania, a mood disorder, is a state of extreme mood elevation and is a diagnosable serious psychiatric disorder. Benzodiazepines can be very useful in the short-term treatment of acute mania, until the effects of lithium or neuroleptics (antipsychotics) take effect. Benzodiazepines bring about rapid tranquillisation and sedation of the manic individual, therefore benzodiazepines are a very important tool in the management of mania. Both clonazepam and lorazepam are used for the treatment, with some evidence that clonazepam may be superior in the treatment of acute mania.[39][40]

Veterinary practice

Benzodiazepines have a wide range of uses in veterinary practice in the treatment of various disorders and scenarios involving animals. As in humans, their usefulness comes from their tranquilizing, muscule relaxing, aggresion inhibiting, and anxiolytic properties. [41]

Benzodiazepines are used before surgery as premedication for muscular relaxtion,[42] and during surgery in combination with other general anesthetic drugs such as ketamine.[43][44] They are an effective in controlling tremors, seizures and epilepsy.[45][46][47]

Midazolam can also be used along with other drugs in the sedation and capture of wild animals.[48]

Contraindications, interactions and side effects

Contraindications

The following are some important contraindications or situations where extreme caution should be exercised when prescribing benzodiazepines.[49][50][51]

- Myasthenia gravis

- Respiratory disorders

- Severe hepatic insufficiency

- Sleep apnoea syndrome

- Pregnancy, labour and lactation

- Breast feeding

- Chronic pain[52]

- Phobic or obsessional states

- Chronic psychosis

- Clinical depression and major depressive disorder - risk of worsening depression and thus precipitating suicidal tendencies

- Abrupt or over rapid withdrawal after long term use is contraindicated - risk of a severe benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome developing with symptoms such as toxic psychosis, convulsions or a condition resembling delirium tremens.

- History of physical dependence on benzodiazepines or other cross tolerant drugs such as other GABAergic sedative hypnotic drugs including alcohol - risk of rapid reinstatement of dependency.[53] Benzodiazepines increase craving for alcohol in problem alcohol consumers. Benzodiazepines also increase the volume of alcohol consumed by problem drinkers.[54]

- Driving a motor vehicle, increased risk of road traffic accidents[55]

Interactions

Individual benzodiazepines may have their own additional interactions which will vary from benzodiazepine to benzodiazepine.[56] The interactions of benzodiazepines as a drug class with other drugs are as follows;[49]

- Alcohol and other CNS depressants - cause synergistic adverse effects, with possible increase in depression and suicide.[57]

- Antacids and anticholinergics - may slow down absortion which may slow down acute therapeutic effects.

- Oral contraceptives, isoniazid - reduces the rate of elimination and thus the half-life increases leading to possibly excessive drug accumulation.

- Cimetidine Inhibition of metabolism of benzodiazepines, causing accumulation which especially with long half life benzodiazepines such as diazepam may cause toxic effects.

- Rifampicin - increases rate of metabolism, thus shortening the elimination half-life of benzodiazepines

- Digoxin - protein binding of diazepam altered causing increased digoxin levels

- L-dopa - worsening of parkinsonian symptoms

- Disulfiram - slows down the rate of metabolism leading to increased effects of benzodiazepines

Side-effects

The following list summarizes the side effects which may occur from use of benzodiazepines.[58]

- Drowsiness

- Dizziness

- Upset stomach

- Blurred vision

- Headache

- Confusion

- Depression

- Euphoria

- Impaired coordination

- Changes in heart rate

- Trembling

- Weakness

- Amnesia

- Hangover effect (grogginess)

- Dreaming or nightmares

- Chest pain

- Vision changes

- Jaundice

- Dissociation or depersonalisation[59]

- Paradoxical reactions[60]

Paradoxical reactions

Severe behavioral changes resulting from benzodiazepines have been reported including mania, schizophrenia, anger, impulsivity, and hypomania.[61] Individuals with borderline personality disorder appear to have a greater risk of experiencing severe behavioral or psychiatric disturbances from benzodiazepines. Aggression and violent outbursts can also occur with benzodiazepines, particularly when they are combined with alcohol. Recreational abusers and patients on high-dosage regimes may be at an even greater risk of experiencing paradoxical reactions to benzodiazepines.[62] Paradoxical reactions may occur in any individual on commencement of therapy and initial monitoring should take into account the risk of increase in anxiety or suicidal thoughts.[60] Benzodiazepines can sometimes cause a paradoxical worsening of EEG readings in patients with seizure disorders.[63]

The core element of a paradoxical rage reaction due to benzodiazepines is a partial deterioration from consciousness, which generates automatic behaviours, anterograde amnesia, and uninhibited aggression, and might occur from disinhibiting a serotonergic mechanism.[64]

Physical dependence and withdrawal

Long-term benzodiazepine usage, in general, leads to some form of tolerance and/or drug dependence with the appearance of a benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome when the benzodiazepines are stopped or the dose is reduced. Withdrawal from chronic benzodiazepine use is usually beneficial due to improved health such as cognition and improved functioning with possible improved employment status. Abrupt withdrawal can be hazardous therefore a gradual withdrawal is recommended. The time needed to complete withdrawal differs from expert to expert but ranges from 4 weeks to several years, with aiming for 6 months suggested by one leading expert.[5]

Approximately half of patients attending mental health services for conditions including anxiety disorders such as panic disorder or social phobia may be the result of alcohol or benzodiazepine dependence. Sometimes anxiety disorders pre-existed alcohol or benzodiazepine dependence but the alcohol or benzodiazepine dependence often act to keep the anxiety disorders going and often progressively making them worse. Many people who are addicted to alcohol or prescribed benzodiazepines when it is explained to them they have a choice between ongoing ill mental health or quitting and recovering from their symptoms decide on quitting alcohol and or their benzodiazepines. It was noted that every individual has an individual sensitivity level to alcohol or sedative hypnotic drugs and what one person can tolerate without ill health another will suffer very ill health and that even moderate drinking can cause rebound anxiety syndromes and sleep disorders. A person who is suffering the toxic effects of alcohol or benzodiazepines will not benefit from other therapies or medications as they do not address the root cause of the symptoms. Recovery from benzodiazepine dependence tends to take a lot longer than recovery from alcohol but people can regain their previous good health.[65]

Withdrawal management

Benzodiazepine withdrawal symptoms occur when benzodiazepine dosage is reduced in people who are physically dependent on benzodiazepines. Abrupt or over-rapid dosage reduction can produce severe withdrawal symptoms. Withdrawal symptoms can even occur during a very gradual and slow dosage reduction.

Benzodiazepine withdrawal is best managed by transferring the physically-dependent patient to an equivalent dose of diazepam because it has the longest half-life of all of the benzodiazepines and is available in low-potency, 2-mg tablets, which can be quartered for small dose reductions.[66] The speed of benzodiazepine reduction regimes varies from person to person, but is usually 10% every 2–4 weeks. A slow withdrawal, preferably under medical supervision by a physician that is knowledgeable about the benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome, with the patient in control of dosage reductions coupled with reassurance that withdrawal symptoms are temporary, have been found to produce the highest success rates. The withdrawal syndrome can usually be avoided or minimized by use of a long half-life benzodiazepine such as diazepam (Valium) or chlordiazepoxide (Librium) and a very gradually tapering off the drug over a period of months, or even up to a year or more, depending on the dosage and degree of dependency of the individual. A slower withdrawal rate significantly reduces the symptoms. In fact, some people feel better and more clear-headed as the dose gradually gets lower, so withdrawal from benzodiazepines is not necessarily an unpleasant event. People that report severe experiences from benzodiazepine withdrawal have almost invariably withdrawn or been withdrawn too quickly.[67]

Pregnancy

In the United States the FDA has categorised benzodiazepines into either category D or category X benzodiazepines.[68] International statistics show that 3.5% of women consume psychotropic drugs during pregnancy and of that 3.5% up to 85% report using benzodiazepines during pregnancy making benzodiazepines the most commonly prescribed psychotropic drug consumed during pregnancy. Approximately 0.4% of all pregnancies are to women who have used benzodiazepines chronically throughout their pregnancy.[69] Neurodevelopmental disorders and clinical symptoms are commonly found in babies exposed to benzodiazepines in utero. Benzodiazepine exposed babies have a low birth weight but catch up to normal babies at an early age but smaller head circumferences found in benzo babies persists. Other adverse effects of benzodiazepines taken during pregnancy are deviating neurodevelopmental and clinical symptoms including craniofacial anomalies, delayed development of pincer grasp, deviations in muscle tone and pattern of movements. Motor impairments in the babies are impeded for up to 1 year after birth. Gross motor development impairments take 18 months to return to normal but fine motor function impairments persist.[70] In addition to the smaller head circumference found in benzodiazepine exposed babies mental retardation, functional deficits, long-lasting behavioural anomalies and lower intelligence occurs.[71][72]

Elderly

Benzodiazepines are generally not recommended for the elderly due to a range of adverse effects.[73] A large cohort study found that benzodiazepine use is associated with a significantly higher incidence of hip fracture. Benzodiazepines of a short half-life are as likely to be associated with hip fracture as long-acting benzodiazepines. Because hip fractures are a frequent cause of disability and death in the elderly, efforts have been underway to reduce benzodiazepine prescribing in the elderly.[74] A review of the literature from between 1975 and 2005 found that medical papers consistently report increased risk of falls and fractures in the elderly. The review paper also found that benzodiazepine hypnotics produce the most significant effects on body sway. Newer hypnotics (eg zaleplon and zolpidem) do not seem to cause such profound effects as benzodiazepines on the elderly.[75] Still, a law introduced in New York State reducing benzodiazepine use by 60% did not result in a measurable decrease in hip fractures.[76] This suggests that any effect of benzodiazepines on fracture rate may be non-significant and more important factors predict fracture rate such as osteoporosis rather than benzodiazepine induced falls.

Benzodiazepines cause an increased morbidity in the elderly which results in an increased use of healthcare services due to the adverse effects of benzodiazepines on the elderly.[77] The elderly are more sensitive to benzodiazepines and are at an increased risk of dependence. Up to 10% of hospital admissions of the elderly are because of benzodiazepines. The elderly are more sensitive to the intellectual and cognitive impairing effects of benzodiazepines including amnesia, diminished short-term recall, and increased forgetfulness. Chronic use of benzodiazepines and benzodiazepine dependence in the elderly can resemble dementia, depression or anxiety syndromes, which worsens with longer-term use of benzodiazepines. The success of gradual-tapering benzodiazepines is as great in the elderly as in younger people. Benzodiazepines should be prescribed to the elderly only with caution and only for a short period at low doses.[78]

An extensive review of the medical literature regarding the management of insomnia and the elderly found that there is significant evidence of the effectiveness and long term effectiveness of non-drug treatments for insomnia in adults, including the elderly and found that these interventions are underused. Nonbenzodiazepine sedative-hypnotics compared with benzodiazepines appeared to offer few, if any, significant clinical advantages in efficacy or tolerability in elderly persons. Melatonin agonists, such as ramelton are more suitable for the management of chronic insomnia in elderly people. The review stated that long-term use of sedative-hypnotics for insomnia lacks an evidence base and has traditionally been discouraged for reasons that include concerns about such potential adverse drug effects as cognitive impairment (anterograde amnesia), daytime sedation, motor incoordination, and increased risk of motor vehicle accidents and falls. In addition, the effectiveness is unproven and the safety of long-term use of these agents is unknown. It was concluded that more research is needed to evaluate the long-term effects of treatment and the most appropriate management strategy for elderly persons with chronic insomnia.[79]

Overdose

Benzodiazepines taken alone rarely cause severe complications in overdose,[80] and deaths after hospital admission are rare.[81] However, combination of these drugs with alcohol or opiates is particularly dangerous, and may lead to coma and death.[82][83] The various benzodiazepines differ in their toxicity since they produce varying levels of sedation in overdose, with oxazepam being least toxic and least sedative and temazepam most toxic and most sedative in overdose. Temazepam is more frequently involved in drug-related deaths causing more deaths per million than other benzodiazepines.[84]

A reversal agent for benzodiazepines exists, flumazenil (Anexate). Its use as an antidote in an overdose however is controversial. Numerous contraindications to its use exist. It is contraindicated in patients who are on long term benzodiazepines, those who have ingested a substance that lowers the seizure threshold or may cause an arrhythmia, and in those with abnormal vital signs. One study found that this is about 10% of the patient population presenting with a benzodiazepine overdose.[85]

Benzodiazepine drug misuse

Drug misuse

Benzodiazepines are used/abused recreationally and activate the dopaminergic reward pathways in the central nervous system.[86]

Benzodiazepine use is widespread among amphetamine abusers, those that use amphetamines and benzodiazepines have greater levels of mental health problems and social deterioration. Benzodiazepine injectors are almost four times more likely to inject using a shared needle than non-benzodiazepine-using injectors. It has been concluded in various studies that benzodiazepine use causes greater levels of risk and psycho-social dysfunction among drug abusers.[87] Those who use stimulant and depressant drugs are more likely to report adverse reactions from stimulant use, more likely to be injecting stimulants, and more likely to have been treated for a drug problem than those using stimulant but not depressant drugs.[88] Increased mortality was found in drug misusers that also used benzodiazepines against those that did not. Heavy alcohol misuse was also found to increase mortality among multiple-drug misusers.[89]

A six-year study on 51 Vietnam veterans who were drug abusers of either mainly stimulants (11 people), mainly opiates (26 people) or mainly benzodiazepines (14 people) was carried out to assess psychiatric symptoms related to the specific drugs of abuse. After six years, opiate abusers had little change in psychiatric symptomatology; 5 of the stimulant users had developed psychosis, and 8 of the benzodiazepine users had developed depression. Therefore, long-term benzodiazepine abuse and dependence seems to carry a negative effect on mental health, with a significant risk of causing depression.[90]

Drug related crime

Problem benzodiazepine use can be associated with drug related crime. In a survey of police detainees carried out by the Australian Government, both legal and illegal users of benzodiazepines were found to be more likely to have lived on the streets, less likely to have been in full time work, and more likely to have used heroin or methamphetamines in the past 30 days from the date of taking part in the survey. Benzodiazepine users were also more likely to be receiving illegal incomes and more likely to have been arrested or imprisoned in the previous year. Benzodiazepines were sometimes reported to be abused alone, but most often formed part of a poly drug-using problem. Female users of benzodiazepines were more likely than men to be using heroin, whereas male users of benzodiazepines were more likely to report amphetamine use. Benzodiazepine users were more likely than non-users to claim government financial benefits, and benzodiazepine users who were also poly-drug users were the most likely to be claiming government financial benefits. Those who reported using benzodiazepines alone were found to be in the mid range when compared to other drug using patterns in terms of property crimes and criminal breaches. Of the detainees reporting benzodiazepine use, one in five reported injection use, mostly of illicit temazepam, but some reported injecting prescribed benzodiazepines. Injection was a concern in this survey due to increased health risks. The main problems highlighted in this survey were concerns of dependence, the potential for overdose of benzodiazepines in combination with opiates and the health problems associated with injection of benzodiazepines.[91] Benzodiazepines are also sometimes used for criminal purposes such as to rob a victim or to incapacitate a victim in cases of drug assisted rape.[92]

Drug regulation and enforcement

Europe

In 2006/2007, seizures of benzodiazepines had trebled from the previous 2 years in the United Kingdom. Temazepam abuse and seizures have been falling in the UK probably due to its reclassification as Schedule III controlled drug with tighter prescribing restrictions and the resultant reduction in availability of temazepam.[93] A total of 2.75 million temazepam capsules were seized in the Netherlands by authorities between 1996 and 1999.[94]

Oceania

Benzodiazepines are common drugs of abuse in Australia and New Zealand, particularly among those who may also be using other illicit drugs. The intravenous use of temazepam poses the greatest threat to those who misuse benzodiazepines. Simultaneous consumption of temazepam with heroin is a potential risk factor of overdose. An Australian study of non-fatal heroin overdoses, noted that 26% of heroin users had consumed temazepam at the time of their overdose. This is consistent with a NSW investigation of coronial files from 1992. Temazepam was found in 26% of heroin-related deaths. Temazepam, including tablet formulations, are used intravenously. In an Australian study of 210 heroin users who used temazepam, 48% had injected it. Although abuse of benzodiazepines has decreased over the past few years, temazepam continues to be a major drug of abuse in Australia. In certain states like Victoria and Queensland, temazepam accounts for most benzodiazepine sought by forgery of prescriptions and through pharmacy burglary. Darke, Ross & Hall found that different benzodiazepines have different abuse potential. The more rapid the increase in the plasma level following ingestion, the greater the intoxicating effect and the more open to abuse the drug becomes. The speed of onset of action of a particular benzodiazepine correlates well with the ‘popularity’ of that drug for abuse. Darke, Ross & Hall found that temazepam rated significantly higher than the next most liked drug, nimetazepam. The two most common reasons for this preference were that it was the ‘strongest’ and that it gave a good ‘high’.[95]

North America

The abuse of benzodiazepine drugs is not considered a serious threat in North America because the abuse of these sedatives is not widespread, as it is in Europe. Nearly all the benzodiazepines abused in the United States and Canada are diverted by doctor shopping, forged prescriptions, theft and, increasingly, via the Internet. The most frequently abused of the benzodiazepines in both the United States and Canada are alprazolam, clonazepam, lorazepam, and diazepam. The powerful hypnotic agents temazepam and triazolam are also subject to considerable misuse. Temazepam and triazolam have seen a steep decline in prescription rates, due to higher rates of major their toxicity and because of the emergence of newer and safer hypnotics like zaleplon and zolpidem. Acute benzodiazepine intoxication (or overdose) and death is extremely rare, though temazepam has a significantly higher death rate relative to all other benzodiazepines used in the United States and Canada. According to the 2003-2005 reports published by the American Association of Poison Control Centers, temazepam had the highest rate of toxicity and overdose among the benzodiazepines commonly prescribed in the United States. Triazolam came next after temazepam.[96][97]

East and Southeast Asia

Abuse of benzodiazepines is a serious problem throughout East and Southeast Asia. Two benzodiazepines in particular are highly valued: Temazepam and Nimetazepam. Nimetazepam is extremely popular in the nations of Japan, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, and Thailand. Although illicit manufacture of the drug does not occur, as it does with temazepam, nimetazepam continues to be the most widely abused benzodiazepine in the region. In the nation of China, nimetazepam and temazepam are major drugs of abuse. Only methamphetamine, heroin, morphine, and smokeable opium are more popular. The Central Narcotics Bureau of Singapore seized 94,200 nimetazepam tablets in 2003. This is the largest nimetazepam seizure recorded since nimetazepam became a controlled drug under the Misuse of Drugs Act in 1992.[98] Testing for the consumption of nimetazepam was introduced in 2004. In that year, nimetazepam abusers formed 20% of abusers arrested. In 2005, nimetazepam abusers had overtaken the other drug types to form the largest proportion of abusers arrested at 26%. Together with temazepam abusers, they accounted for 47% of the abusers arrested in 2005.[99] In Singapore, both temazepam and nimetazepam are Class A Schedule I controlled drugs. Similar harsh laws apply to both of these benzodiazepines all across Asia. In Hong Kong, for example, they're both regulated under Schedule 1 of Hong Kong's Chapter 134 Dangerous Drugs Ordinance. Other benzodiazepines which are commonly abused in the region are nitrazepam, triazolam, flutoprazepam, and oxazepam, though these four are not subject to the same stringent levels of control and regulation.

Legal status

Benzodiazepines are Schedule IV in the USA under the Federal Controlled Substances Act, even when not on the market (for example, nitrazepam and bromazepam). Flunitrazepam is subject to more stringent regulations in certain States, and temazepam prescriptions require specially coded pads in certain States. In Canada all benzodiazepines are Schedule IV.[100]

Elsewhere in the world, however, benzodiazepines which are often subject to heavy abuse and addiction are often more strictly regulated or controlled. Temazepam, nimetazepam and flunitrazepam are the world's most heavily regulated benzodiazepines.

Throughout Europe, including the United Kingdom, temazepam and flunitrazepam also carry tougher penalties for trafficking and possession.[101]

In the Netherlands, since October 1993, benzodiazepines are all placed on List 2 of the Opium Law, with the exception of any 20mg temazepam formulations, which are List 1. A prescription is needed for possession of all benzodiazepines.

In East Asia and Southeast Asia, temazepam and nimetazepam are often heavily controlled and restricted. In certain countries, triazolam, flunitrazepam, flutoprazepam and midazolam are also restricted or controlled to certain degrees. In Hong Kong all benzodiazepines were reclassified as dangerous drugs and are regulated under Schedule 1 of Hong Kong's Chapter 134 Dangerous Drugs Ordinance. Previously only brotizolam, flunitrazepam and triazolam were classed as dangerous drugs.[102]

Internationally, temazepam, nimetazepam, and flunitrazepam are Schedule III drugs under the Convention on Psychotropic Substances.[103] As such, penalties for their possession and/or trafficking are more severe than all other benzodiazepine drugs, which are classified as Schedule IV.

Various other countries limit the availability of benzodiazepines legally. Even though it is a commonly-prescribed class of drugs, the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act specifically states that insurance companies that provide Medicare Part D plans are not allowed to cover benzodiazepines.

See also

- Benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome

- Long term effects of benzodiazepines

- Benzodiazepine dependence

- Benzodiazepine equivalence

- Nonbenzodiazepine

- Barbiturate

- Z drugs

References

- ^ McKernan RM (2000). "Sedative but not anxiolytic properties of benzodiazepines are mediated by the GABA(A) receptor alpha1 subtype". Nature neuroscience. 3 (6): 587–92. doi:10.1038/75761. PMID 10816315.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Bulach R, Myles PS, Russnak M (2004). "Double-blind randomized controlled trial to determine extent of amnesia with midazolam given immediately before general anaesthesia" (PDF). Br J Anaesth. 94 (3): 300–305. doi:10.1093/bja/aei040. PMID 15567810.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Leikin JB, Krantz AJ, Zell-Kanter M, Barkin RL, Hryhorczuk DO (1989). "Clinical features and management of intoxication due to hallucinogenic drugs". Med Toxicol Adverse Drug Exp. 4 (5): 324–50. PMID 2682130.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hurlbut KM (1991). "Drug-induced psychoses". Emerg. Med. Clin. North Am. 9 (1): 31–52. PMID 2001668.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Lader M, Tylee A, Donoghue J (2009). "Withdrawing benzodiazepines in primary care". CNS Drugs. 23 (1): 19–34. PMID 19062773.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cooper, Jack R (January 15, 1996). The Complete Story of the Benzodiazepines (in Eng) (seventh ed.). USA: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195103998. OCLC 223003583. Retrieved 07.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|accessmonth=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|origmonth=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ New York Times (30 December 1963). "Warning Is Issued On Tranquilizers". USA: New York Times. p. 23.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|curly=ignored (help) - ^ Lemmer B (2007). "The sleep-wake cycle and sleeping pills". Physiol. Behav. 90 (2–3): 285–93. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.09.006. PMID 17049955.

- ^ Siriwardena AN, Qureshi Z, Gibson S, Collier S, Latham M (2006). "GPs' attitudes to benzodiazepine and 'Z-drug' prescribing: a barrier to implementation of evidence and guidance on hypnotics". Br J Gen Pract. 56 (533): 964–7. PMC 1934058. PMID 17132386.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mellingsaeter TC, Bramness JG, Slørdal L (2006). "[Are z-hypnotics better and safer sleeping pills than benzodiazepines?]". Tidsskr. Nor. Laegeforen. (in Norwegian). 126 (22): 2954–6. PMID 17117195.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pym LJ, Cook SM, Rosahl T, McKernan RM, Atack JR (2005). "Selective labelling of diazepam-insensitive GABAA receptors in vivo using [3H]Ro 15-4513". Br. J. Pharmacol. 146 (6): 817–25. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0706392. PMID 16184188.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Möhler H, Fritschy JM, Rudolph U (2002). "A new benzodiazepine pharmacology". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 300 (1): 2–8. PMID 11752090.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lowenstein PR, Rosenstein R, Caputti E, Cardinali DP (1984). "Benzodiazepine binding sites in human pineal gland". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 106 (2): 399–403. PMID 6099276.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hevers W, Lüddens H (1998). "The diversity of GABAA receptors. Pharmacological and electrophysiological properties of GABAA channel subtypes". Mol. Neurobiol. 18 (1): 35–86. doi:10.1007/BF02741459. PMID 9824848.

- ^ Tardy M (1981). "Benzodiazepine receptors on primary cultures of mouse astrocytes". J Neurochem. 36 (4): 1587–9. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1981.tb00603.x. PMID 6267195.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Atack JR (2003). "Anxioselective compounds acting at the GABAA receptor benzodiazepine binding site". Current drug targets. CNS and neurological disorders. 2 (4): 213–32. doi:10.2174/1568007033482841. PMID 12871032.

- ^ McLean MJ (1988). "Benzodiazepines, but not beta carbolines, limit high-frequency repetitive firing of action potentials of spinal cord neurons in cell culture". J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 244 (2): 789–95. PMID 2450203.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Woods MG, Williams DC (1996). Multiple forms and locations for the peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor. Vol. 52. pp. 1805–1814. doi:10.1016/S0006-2952(96)00558-8. PMID 8951338.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Tanimoto Yutaka (1999). "Benzodiazepine Receptor Agonists Modulate Thymocyte Apoptosis Through Reduction of the Mitochondrial Transmembrane Potential" (PDF). Jpn J Pharmacol. 79: 177–183. doi:10.1254/jjp.79.177. PMID 10202853.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Pawlikowski M (1993). "Immunomodulating effects of peripherally acting benzodiazepines". New York: In Peripheral Benzodiazepine Receptors. Academic press. pp. 125–135.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|curly=ignored (help) - ^ Greenblatt DJ, Shader RI, Divoll M, Harmatz JS (1981). "Benzodiazepines: a summary of pharmacokinetic properties". Br J Clin Pharmacol. 11 Suppl 1: 11S–16S. PMC 1401650. PMID 6133528.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Summers RS, Schutte A, Summers B (1990). "Benzodiazepine use in a small community hospital. Appropriate prescribing or not?". S. Afr. Med. J. 78 (12): 721–5. PMID 2251629.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Danneberg P, Weber KH (1983). "Chemical structure and biological activity of the diazepines". Br J Clin Pharmacol. 16 (Suppl 2): 231S–244S. PMC 1428206. PMID 6140944.

- ^ Earley JV, Fryer RI, Ning RY (1979). "Quinazolines and 1,4-benzodiazepines. LXXXIX: Haptens useful in benzodiazepine immunoassay development". J Pharm Sci. 68 (7): 845–50. doi:10.1002/jps.2600680715. PMID 458601.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Prasad K (2007). "Anticonvulsant therapy for status epilepticus". British journal of clinical pharmacology. 63 (6): 640–7. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003723.pub2. PMID 17439538.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Treiman DM. (1989). "Pharmacokinetics and clinical use of benzodiazepines in the management of status epilepticus". Epilepsia. 30 (2): 4–10. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1989.tb05824.x. PMID 2670537.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ BNF (2008). "Anxiolytics". UK: British National Formulary. Retrieved 17 december 2008.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Uhlenhuth EH, Balter MB, Ban TA, Yang K (1999). "International study of expert judgment on therapeutic use of benzodiazepines and other psychotherapeutic medications: VI. Trends in recommendations for the pharmacotherapy of anxiety disorders, 1992-1997". Depress Anxiety. 9 (3): 107–16. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6394(1999)9:3<107::AID-DA2>3.0.CO;2-T. PMID 10356648.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Uhlenhuth EH, Balter MB, Ban TA, Yang K (1995). "International study of expert judgement on therapeutic use of benzodiazepines and other psychotherapeutic medications: II. Pharmacotherapy of anxiety disorders". J Affect Disord. 35 (4): 153–62. doi:10.1016/0165-0327(95)00064-X. PMID 8749980.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Uhlenhuth EH, Balter MB, Ban TA, Yang K (1999). "Trends in recommendations for the pharmacotherapy of anxiety disorders by an international expert panel, 1992-1997". Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 9 Suppl 6: S393–8. doi:10.1016/S0924-977X(99)00050-4. PMID 10622685.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Uhlenhuth EH, Balter MB, Ban TA, Yang K (1999). "International study of expert judgment on therapeutic use of benzodiazepines and other psychotherapeutic medications: IV. Therapeutic dose dependence and abuse liability of benzodiazepines in the long-term treatment of anxiety disorders". J Clin Psychopharmacol. 19 (6 Suppl 2): 23S–29S. doi:10.1097/00004714-199912002-00005. PMID 10587281.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stevens JC, Pollack MH (2005). "Benzodiazepines in clinical practice: consideration of their long-term use and alternative agents". J Clin Psychiatry. 66 Suppl 2: 21–7. PMID 15762816.

- ^ Bruce SE, Vasile RG, Goisman RM, Salzman C, Spencer M, Machan JT, Keller MB (2003). "Are benzodiazepines still the medication of choice for patients with panic disorder with or without agoraphobia?". Am J Psychiatry. 160 (8): 1432–8. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.8.1432. PMID 12900305.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ BNF (2008). "Hypnotics". UK: British National Formulary. Retrieved 17 december 2008.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c BNF (2008). "Sedative and analgesic peri-operative drugs". UK: British National Formulary. Retrieved 17 december 2008.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Wilson A, Vulcano B (1984). "A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of magnesium sulfate in the ethanol withdrawal syndrome". Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 8 (6): 542–5. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.1984.tb05726.x. PMID 6393805.

- ^ Raistrick, D, Heather N, Godfrey C. "Review of the Effectiveness of Treatment for Alcohol Problems" (PDF). National Treatment Agency for Substance Misuse, London. Retrieved 2008-06-19.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ BNF (2008). "Skeletal muscle relaxants". UK: British National Formulary. Retrieved 17 december 2008.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Bottaï T (1995). "Clonazepam in acute mania: time-blind evaluation of clinical response and concentrations in plasma". Journal of affective disorders. 36 (1–2): 21–7. doi:10.1016/0165-0327(95)00048-8. PMID 8988261.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Curtin F (2004). "Clonazepam and lorazepam in acute mania: a Bayesian meta-analysis". Journal of affective disorders. 78 (3): 201–8. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00317-8. PMID 15013244.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Dilov P (1984). "[Pharmacological and clinico-pharmacological studies of diazepam powder in suspensions]". Veterinarno-meditsinski nauki. 21 (3): 96–103. doi:10.1093/bja/aei040. PMID 6740928.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Singh K (1989). "Studies on lorazepam as a premedicant for thiopental anaesthesia in the dog". Zentralblatt für Veterinärmedizin. Reihe A. 36 (10): 750–4. PMID 2515684.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Yamashita K (2007). "Anesthetic and cardiopulmonary effects of total intravenous anesthesia using a midazolam, ketamine and medetomidine drug combination in horses". The Journal of veterinary medical science / the Japanese Society of Veterinary Science. 69 (1): 7–13. PMID 17283393.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Woolfson MW (1980). "Immobilization of baboons (Papio anubis) using ketamine and diazepam". Laboratory animal science. 30 (5): 902–4. PMID 7431875.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Wagner SO (September 15, 1997). "Generalized tremors in dogs: 24 cases (1984-1995)". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 211 (6): 731–5. PMID 9301744.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Bateman SW (November 15, 1999). "Clinical findings, treatment, and outcome of dogs with status epilepticus or cluster seizures: 156 cases (1990-1995)". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 215 (10): 1463–8. PMID 10579043.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Podell M. (1996). "Seizures in dogs". The Veterinary clinics of North America. Small animal practice. 26 (4): 779–809. PMID 8813750.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Nel PJ (2000). "Capture and immobilisation of aardvark (Orycteropus afer) using different drug combinations". Journal of the South African Veterinary Association. 71 (1): 58–63. PMID 10949520.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Trevor R Norman,. "Benzodiazepines in anxiety disorders: managing therapeutics and dependence" (PDF). The Medical Journal of Australia. Retrieved 11 December 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Dr Laurence Knott (17 October 2007). "Benzodiazepines". Patient UK. Retrieved 11 December 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ BJC Healthcare. "Benzodiazepines". BJC Behavioral Health. Retrieved 11 December 2008.

- ^ Boell, R; Rubin, J (1991). "Benzodiazepines—contraindicated in the patient with chronic pain". South African medical journal = Suid-Afrikaanse tydskrif vir geneeskunde. 80 (1): 59. ISSN 0256-9574. PMID 2063244.

{{cite journal}}: Missing pipe in:|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Higgitt, A; Fonagy, P; Lader, M (1988). "The natural history of tolerance to the benzodiazepines". Psychological medicine. Monograph supplement. 13: 1–55. ISSN 0264-1801. PMID 2908516.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Poulos CX, Zack M (2004). "Low-dose diazepam primes motivation for alcohol and alcohol-related semantic networks in problem drinkers". Behav Pharmacol. 15 (7): 503–12. PMID 15472572.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Verster JC, Veldhuijzen DS, Patat A, Olivier B, Volkerts ER (2006). "Hypnotics and driving safety: meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials applying the on-the-road driving test". Curr Drug Saf. 1 (1): 63–71. PMID 18690916.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Oda M, Kotegawa T, Tsutsumi K, Ohtani Y, Kuwatani K, Nakano S (2003). "The effect of itraconazole on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of bromazepam in healthy volunteers" (PDF). Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 59 (8–9): 615–9. doi:10.1007/s00228-003-0681-4. PMID 14517708.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ziegler PP (2007). "Alcohol use and anxiety". Am J Psychiatry. 164 (8): 1270, author reply 1270–1. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07020291. PMID 17671296.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ medicinenet. "BENZODIAZEPINES - ORAL". medicinenet.com. Retrieved 10 April 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ Good MI (1989). "Substance-induced dissociative disorders and psychiatric nosology". J Clin Psychopharmacol. 9 (2): 88–93. PMID 2656780.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Carissa E. Mancuso, Maria G, Tanzi, Michael Gabay. (30 September 2004). "Paradoxical Reactions to Benzodiazepines". Pharmacotherapy. University of Illinois - Department of Pharmacy: Medscape.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cole JO (1993). "Adverse behavioral events reported in patients taking alprazolam and other benzodiazepines". The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 54 (49–61): 62–3. PMID 8262890.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Drummer, OH (2002). "Benzodiazepines — Effects on Human Performance and Behavior" (PDF). Forensic Science Review.

- ^ Perlwitz R (1980). "[Immediate effect of intravenous clonazepam on the EEG]". Psychiatr Neurol Med Psychol (Leipz). 32 (6): 338–44. PMID 7403357.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Senninger JL (1995). "[Violent paradoxal reactions secondary to the use of benzodiazepines]". Annales médico-psychologiques. 153 (4): 278–81. doi:10.1093/bja/aei040. PMID 7618826.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Cohen SI (1995). "Alcohol and benzodiazepines generate anxiety, panic and phobias" (PDF). J R Soc Med. 88 (2): 73–7. PMC 1295099. PMID 7769598.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Dr JG McConnell (2007). "The Clinicopharmacotherapeutics of Benzodiazepine and Z drug dose Tapering Using Diazepam".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Professor Heather Ashton (2002). "Benzodiazepines: How They Work and How To Withdraw".

- ^ BJC Behavioral Health. "Benzodiazepines". BJC. Retrieved 18 April 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ F, Marchetti (1993). "Use of psychotropic drugs during pregnancy" (pdf). European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 45 (6). Springer Berlin / Heidelberg: 495–501. doi:10.1007/BF00315304. ISSN 1432-1041. PMID 7908878.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ L, Laegreid (1992). "Neurodevelopment in late infancy after prenatal exposure to benzodiazepines—a prospective study". Neuropediatrics. 23 (2): 60–7. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1071314. PMID 1351263.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ L, Laegreid (1990). "Clinical observations in children after prenatal benzodiazepine exposure". Dev Pharmacol Ther. 15 (3–4): 186–8. PMID 1983095.

- ^ Karkos, J (1991). "The neurotoxicity of benzodiazepines". Fortschritte der Neurologie-Psychiatrie. 59 (12): 498–520. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1000726. ISSN 0720-4299. PMID 1685467.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Lechin F, van der Dijs B, Benaim M (1996). "Benzodiazepines: tolerability in elderly patients". Psychother Psychosom. 65 (4): 171–82. PMID 8843497.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wagner AK, Zhang F, Soumerai SB, Walker AM, Gurwitz JH, Glynn RJ, Ross-Degnan D (2004). "Benzodiazepine use and hip fractures in the elderly: who is at greatest risk?". Arch. Intern. Med. 164 (14): 1567–72. doi:10.1001/archinte.164.14.1567. PMID 15277291.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Allain H, Bentué-Ferrer D, Polard E, Akwa Y, Patat A (2005). "Postural instability and consequent falls and hip fractures associated with use of hypnotics in the elderly: a comparative review". Drugs Aging. 22 (9): 749–65. PMID 16156679.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wagner AK, Ross-Degnan D, Gurwitz JH, Zhang F, Gilden DB, Cosler L, Soumerai SB (2007). "Effect of New York State regulatory action on benzodiazepine prescribing and hip fracture rates" (PDF). Ann. Intern. Med. 146 (2): 96–103. PMID 17227933.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rojas-Fernandez CH, Carver D, Tonks R (1999). "Population trends in the prevalence of benzodiazepine use in the older population of Nova Scotia: A cause for concern?". Can J Clin Pharmacol. 6 (3): 149–56. PMID 10495367.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bogunovic OJ, Greenfield SF (2004). "Practical geriatrics: Use of benzodiazepines among elderly patients". Psychiatr Serv. 55 (3): 233–5. PMID 15001721.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Bain KT (2006). "Management of chronic insomnia in elderly persons". Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 4 (2): 168–92. doi:10.1016/j.amjopharm.2006.06.006. PMID 16860264.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Gaudreault P, Guay J, Thivierge RL, Verdy I (1991). "Benzodiazepine poisoning. Clinical and pharmacological considerations and treatment". Drug Saf. 6 (4): 247–65. doi:10.2165/00002018-199106040-00003. PMID 1888441.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Höjer J, Baehrendtz S, Gustafsson L (1989). "Benzodiazepine poisoning: experience of 702 admissions to an intensive care unit during a 14-year period". J. Intern. Med. 226 (2): 117–22. PMID 2769176.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dietze P, Jolley D, Fry C, Bammer G (2005). "Transient changes in behaviour lead to heroin overdose: results from a case-crossover study of non-fatal overdose". Addiction. 100 (5): 636–42. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01051.x. PMID 15847621.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hammersley R (1995). "Drugs associated with drug-related deaths in Edinburgh and Glasgow, November 1990 to October 1992". Addiction. 90 (7): 959–65. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1995.tb03504.x. PMID 7663317.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Buckley NA, Dawson AH, Whyte IM, O'Connell DL (1995). "Relative toxicity of benzodiazepines in overdose". BMJ. 310 (6974): 219–21. PMID 7866122.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Goldfrank, Lewis R. (2002). Goldfrank's toxicologic emergencies. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical Publ. Division. ISBN 0-07-136001-8.

- ^ Söderpalm B (1991). "Evidence for a role for dopamine in the diazepam locomotor stimulating effect". Psychopharmacology. 104 (1): 97–102. doi:10.1007/BF02244561. PMID 1679244.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Darke S (1994). "The use of benzodiazepines among regular amphetamine users". Addiction (Abingdon, England). 89 (12): 1683–90. PMID 7866252.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Williamson S (March 14, 1997). "Adverse effects of stimulant drugs in a community sample of drug users". Drug and alcohol dependence. 44 (2–3): 87–94. doi:10.1016/S0376-8716(96)01324-5. PMID 9088780.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Gossop M (2002). "A prospective study of mortality among drug misusers during a 4-year period after seeking treatment". Addiction (Abingdon, England). 97 (1): 39–47. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00079.x. PMID 11895269.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Woody GE (1979). "Development of psychiatric illness in drug abusers. Possible role of drug preference". The New England journal of medicine. 301 (24): 1310–4. PMID 41182.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Government, Australian (2007). "Benzodiazepine use and harms among police detainees in Australia" (PDF). Australian Institute of Criminology.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Marc B, Baudry F, Vaquero P, Zerrouki L, Hassnaoui S, Douceron H (2000). "Sexual assault under benzodiazepine submission in a Paris suburb" (PDF). Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 263 (4): 193–7. PMID 10834331.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ The Scottish Government (3 June 2008). "Statistical Bulletin - DRUG SEIZURES BY SCOTTISH POLICE FORCES, 2005/2006 AND 2006/2007" (PDF). Crime and justice series. Scotland: scotland.gov.uk. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ INCB (1999). "Operation of the international drug control system" (PDF). incb.org. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Australian Government (2004). "ACT MEDICAL BOARD - STANDARDS STATEMENT - PRESCRIBING OF BENZODIAZEPINES" (PDF). Australia: medicalboard.act.gov.au. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Watson WA; Litovitz TL; Rodgers GC; Klein-Schwartz W; Reid N; Youniss J; Flanagan A; Wruk KM (2005). "2004 Annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers Toxic Exposure Surveillance System". American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 23: 589–666. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2005.05.001. Retrieved 2008-03-01.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|issues=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lai MW; Klein-Schwartz W; Rodgers GC; Abrams JY; Haber DA; Bronstein AC; Wruk KM (2006). "2005 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers' national poisoning and exposure database". Clinical Toxicology (Philadelphia, PA). 44: 803–932. Retrieved 2008-03-01.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|issues=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Central Narcotics Bureau (2003). "Drug Situation Report 2003". Singapore: cnb.gov.sg. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Hong Kong Government. "Suppression of Illicit Trafficking and Manufacturing" (PDF). Hong Kong: nd.gov.hk. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

- ^ DEA, USA. "Benzodiazepines". Drug Enforcement Agency.

{{cite web}}: More than one of|author=and|last=specified (help) - ^ UK, Gov (2006). "List of Drugs Currently Controlled Under The Misuse of Drugs Legislation". Misuse of Drugs Act UK. Retrieved 06 1 0 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); More than one of|author=and|last=specified (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Lee KK, Chan TY, Chan AW, Lau GS, Critchley JA (1995). "Use and abuse of benzodiazepines in Hong Kong 1990-1993--the impact of regulatory changes". J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol. 33 (6): 597–602. PMID 8523479.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ International Narcotics Control Board (2003). "List of psychotropic substances under international control" (PDF). incb.org. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

External links

- Ashton CH (2002-08-01). "Benzodiazepines How They Work & How to Withdraw". benzo.org.uk. Retrieved 2008-06-19.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Ashton CH (2007-04-01). "Benzodiazepine Equivalence Table". benzo.org.uk. Retrieved 2008-06-19.

- Fruchtengarten L, (1998-04-01). "Benzodiazepines". PIM G008. International Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS) INCHEM. Retrieved 2008-06-19.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - Longo LP, Johnson B (2000-04-01). "Benzodiazepines Side Effects, Abuse Risk and Alternatives". Addiction: Part I. American Academy of Family Physicians. Retrieved 2008-06-19.

- "An Overview of the History, Chemistry, and Pharmacodynamics of Benzodiazepines". The Eaton T. Fores Research Center. 2002-01-01. Retrieved 2008-06-19.

- "Benzodiazepines advanced consumer information". drugs.com. 2005-02-24. Retrieved 2008-06-19.

{{cite web}}: Text "Drugs.com" ignored (help)