Rabindranath Tagore

Rabindranath Tagore | |

|---|---|

Tagore c. 1915, the year he was knighted by George V. Tagore repudiated his knighthood, in protest against the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in 1919.[1] | |

| Born | Rabindranath Thakur May 7, 1861 Calcutta, Bengal Presidency, British India |

| Died | 7 August 1941 (aged 80) Calcutta, Bengal Presidency, British India |

| Occupation | Poet, short-story writer, song composer, novelist, playwright, essayist, and painter |

| Language | Bengali, English |

| Nationality | India |

| Notable works | Gitanjali, Gora, Ghare-Baire, Jana Gana Mana, Rabindra Sangeet, Amar Shonar Bangla (other works) |

| Notable awards | Nobel Prize in Literature 1913 |

| Spouse |

Mrinalini Devi (m. 1883–1902) |

| Children | five children, two of whom died in childhood |

| Relatives | Tagore family |

| Signature | |

Rabindranath Thakur[α], anglicised to Tagore[β] (7 May 1861 – 7 August 1941),[γ] sobriquet Gurudev,[δ] was a Bengali polymath who reshaped his region's literature and music. Author of Gitanjali and its "profoundly sensitive, fresh and beautiful verse",[2] he became the first non-European to win the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913.[3] In translation his poetry was viewed as spiritual and mercurial; his seemingly mesmeric personality, flowing hair, and otherworldly dress earned him a prophet-like reputation in the West. His "elegant prose and magical poetry" remain largely unknown outside Bengal.[4] Tagore introduced new prose and verse forms and the use of colloquial language into Bengali literature, thereby freeing it from traditional models based on classical Sanskrit. He was highly influential in introducing the best of Indian culture to the West and vice versa, and he is generally regarded as the outstanding creative artist of modern India.[5]

A Pirali Brahmin[6][7][8][9] from Calcutta, Tagore wrote poetry as an eight-year-old.[10] At age sixteen, he released his first substantial poems under the pseudonym Bhānusiṃha ("Sun Lion"), which were seized upon by literary authorities as long-lost classics.[5][11] He graduated to his first short stories and dramas—and the aegis of his birth name—by 1877. As a humanist, universalist internationalist, and strident anti-nationalist he denounced the Raj and advocated independence from Britain. As an exponent of the Bengal Renaissance, he advanced a vast canon that comprised paintings, sketches and doodles, hundreds of texts, and some two thousand songs; his legacy endures also in the institution he founded, Visva-Bharati University.[12]

Tagore modernised Bengali art by spurning rigid classical forms and resisting linguistic strictures. His novels, stories, songs, dance-dramas, and essays spoke to topics political and personal. Gitanjali (Song Offerings), Gora (Fair-Faced), and Ghare-Baire (The Home and the World) are his best-known works, and his verse, short stories, and novels were acclaimed—or panned—for their lyricism, colloquialism, naturalism, and unnatural contemplation. His compositions were chosen by two nations as national anthems: India's Jana Gana Mana and Bangladesh's Amar Shonar Bangla.

Early life: 1861–1878

The youngest of thirteen surviving children, Tagore was born in the Jorasanko mansion in Calcutta, India to parents Debendranath Tagore (1817–1905) and Sarada Devi (1830–1875).[ε][13] The Tagore family came into prominence during the Bengal Renaissance that started during the age of Hussein Shah (1493 – 1519). The original name of the Tagore family was Banerjee. Being Brahmins, their ancestors were referred to as ‘Thakurmashai’ or ‘Holy Sir’. During the British rule, this name stuck and they began to be recognized as Thakur and eventually the family name got anglicized to Tagore.Tagore family patriarchs were the Brahmo founders of the Adi Dharm faith. The loyalist "Prince" Dwarkanath Tagore, who employed European estate managers and visited with Victoria and other royalty, was his paternal grandfather.[14] Debendranath had formulated the Brahmoist philosophies espoused by his friend Ram Mohan Roy, and became focal in Brahmo society after Roy's death.[15][16]

The last two days a storm has been raging, similar to the description in my song—Jhauro jhauro borishe baridhara [... amidst it] a hapless, homeless man drenched from top to toe standing on the roof of his steamer [...] the last two days I have been singing this song over and over [...] as a result the pelting sound of the intense rain, the wail of the wind, the sound of the heaving Gorai [R]iver, have assumed a fresh life and found a new language and I have felt like a major actor in this new musical drama unfolding before me.

— Letter to Indira Devi.[17]

"Rabi" was raised mostly by servants; his mother had died in his early childhood and his father travelled widely.[18] His home hosted the publication of literary magazines; theatre and recitals of both Bengali and Western classical music featured there regularly, as the Jorasanko Tagores were the center of a large and art-loving social group. Tagore's oldest brother Dwijendranath was a respected philosopher and poet. Another brother, Satyendranath, was the first Indian appointed to the elite and formerly all-European Indian Civil Service. Yet another brother, Jyotirindranath, was a musician, composer, and playwright.[19] His sister Swarnakumari became a novelist. Jyotirindranath's wife Kadambari, slightly older than Tagore, was a dear friend and powerful influence. Her abrupt suicide in 1884 left him for years profoundly distraught.

Tagore largely avoided classroom schooling and preferred to roam the manor or nearby Bolpur and Panihati, idylls which the family visited.[20][21] His brother Hemendranath tutored and physically conditioned him—by having him swim the Ganges or trek through hills, by gymnastics, and by practicing judo and wrestling. He learned drawing, anatomy, geography and history, literature, mathematics, Sanskrit, and English—his least favorite subject.[22] Tagore loathed formal education—his scholarly travails at the local Presidency College spanned a single day. Years later he held that proper teaching does not explain things; proper teaching stokes curiosity:[23]

[It] knock[s] at the doors of the mind. If any boy is asked to give an account of what is awakened in him by such knocking, he will probably say something silly. For what happens within is much bigger than what comes out in words. Those who pin their faith on university examinations as the test of education take no account of this.[23]

After he underwent an upanayan initiation at age eleven, he and his father left Calcutta in February 1873 for a months-long tour of the Raj. They visited his father's Santiniketan estate and rested in Amritsar en route to the Himalayan Dhauladhars, their destination being the remote hill station at Dalhousie. Along the way, Tagore read biographies; his father tutored him in history, astronomy, and Sanskrit declensions. He read biographies of Benjamin Franklin among other figures; they discussed Edward Gibbon's The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire; and they examined the poetry of Kālidāsa.[24] In mid-April they reached the station, and at 2,300 metres (7,546 ft) they settled into a house that sat atop Bakrota Hill. Tagore was taken aback by the region's deep green gorges, alpine forests, and mossy streams and waterfalls.[25] They stayed there for several months and adopted a regime of study and privation that included daily twilight baths taken in icy water.[26][27]

He returned to Jorosanko and completed a set of major works by 1877, one of them a long poem in the Maithili style of Vidyapati; they were published pseudonymously. Regional experts accepted them as the lost works of Bhānusimha, a newly discovered[ζ] 17th-century Vaishnava poet.[28] He debuted the short-story genre in Bengali with "Bhikharini" ("The Beggar Woman"),[29][30] and his Sandhya Sangit (1882) includes the famous poem "Nirjharer Swapnabhanga" ("The Rousing of the Waterfall"). Servants subjected him to an almost ludicrous regimentation in a phase he dryly reviled as the "servocracy".[31] His head was water-dunked—to quiet him.[32] He irked his servants by refusing food; he was confined to chalk circles in parody of Sita's forest trial in the Ramayana; and he was regaled with the heroic criminal exploits of Bengal's outlaw-dacoits.[33] Because the Jorasanko manor was in an area of north Calcutta rife with poverty and prostitution,[34] he was forbidden to leave it for any purpose other than traveling to school. He thus became preoccupied with the world outside and with nature. Of his 1873 visit to Santiniketan, he wrote:

What I could not see did not take me long to get over—what I did see was quite enough. There was no servant rule, and the only ring which encircled me was the blue of the horizon, drawn around these solitudes by their presiding goddess. Within this I was free to move about as I chose.[35]

Shelaidaha: 1878–1901

Because Debendranath wanted his son to become a barrister, Tagore enrolled at a public school in Brighton, East Sussex, England in 1878.[17] He stayed for several months at a house that the Tagore family owned near Brighton and Hove, in Medina Villas; in 1877 his nephew and niece—Suren and Indira Devi, the children of Tagore's brother Satyendranath—were sent together with their mother, Tagore's sister-in-law, to live with him.[36] He briefly read law at University College London, but again left school. He opted instead for independent study of Shakespeare, Religio Medici, Coriolanus, and Antony and Cleopatra. Lively English, Irish, and Scottish folk tunes impressed Tagore, whose own tradition of Nidhubabu-authored kirtans and tappas and Brahmo hymnody was subdued.[17][37] In 1880 he returned to Bengal degree-less, resolving to reconcile European novelty with Brahmo traditions, taking the best from each.[38] In 1883 he married Mrinalini Devi, born Bhabatarini, 1873–1902; they had five children, two of whom died in childhood.[39]

In 1890 Tagore began managing his vast ancestral estates in Shelaidaha (today a region of Bangladesh); he was joined by his wife and children in 1898. Tagore released his Manasi poems (1890), among his best-known work.[40] As Zamindar Babu, Tagore criss-crossed the riverine holdings in command of the Padma, the luxurious family barge. He collected mostly token rents and blessed villagers who in turn honoured him with banquets—occasionally of dried rice and sour milk.[41] He met Gagan Harkara, through whom he became familiar with Baul Lalon Shah, whose folk songs greatly influenced Tagore.[42] Tagore worked to popularise Lalon's songs. The period 1891–1895, Tagore's Sadhana period, named after one of Tagore's magazines, was his most productive;[18] in these years he wrote more than half the stories of the three-volume, 84-story Galpaguchchha.[29] Its ironic and grave tales examined the voluptuous poverty of an idealised rural Bengal.[43]

Santiniketan: 1901–1932

In 1901 Tagore moved to Santiniketan to found an ashram with a marble-floored prayer hall—The Mandir—an experimental school, groves of trees, gardens, a library.[44] There his wife and two of his children died. His father died in 1905. He received monthly payments as part of his inheritance and income from the Maharaja of Tripura, sales of his family's jewelry, his seaside bungalow in Puri, and a derisory 2,000 rupees in book royalties.[45] He gained Bengali and foreign readers alike; he published Naivedya (1901) and Kheya (1906) and translated poems into free verse. In November 1913, Tagore learned he had won that year's Nobel Prize in Literature: the Swedish Academy appreciated the idealistic—and for Westerners—accessible nature of a small body of his translated material focussed on the 1912 Gitanjali: Song Offerings.[46] In 1915, the British Crown granted Tagore a knighthood. He renounced it after the 1919 Jallianwala Bagh massacre.

In 1921, Tagore and agricultural economist Leonard Elmhirst set up the "Institute for Rural Reconstruction", later renamed Shriniketan or "Abode of Welfare", in Surul, a village near the ashram. With it, Tagore sought to moderate Gandhi's Swaraj protests, which he occasionally blamed for British India's perceived mental—and thus ultimately colonial—decline.[47] He sought aid from donors, officials, and scholars worldwide to "free village[s] from the shackles of helplessness and ignorance" by "vitalis[ing] knowledge".[48][49] In the early 1930s he targeted ambient "abnormal caste consciousness" and untouchability. He lectured against these, he penned Dalit heroes for his poems and his dramas, and he campaigned—successfully—to open Guruvayoor Temple to Dalits.[50][51]

Twilight years: 1932–1941

Tagore's life as a "peripatetic litterateur" affirmed his opinion that human divisions were shallow. During a May 1932 visit to a Bedouin encampment in the Iraqi desert, the tribal chief told him that "Our prophet has said that a true Muslim is he by whose words and deeds not the least of his brother-men may ever come to any harm ..." Tagore confided in his diary: "I was startled into recognizing in his words the voice of essential humanity."[52] To the end Tagore scrutinised orthodoxy—and in 1934, he struck. That year, an earthquake hit Bihar and killed thousands. Gandhi hailed it as seismic karma, as divine retribution avenging the oppression of Dalits. Tagore rebuked him for his seemingly ignominious inferences.[53] He mourned the perennial poverty of Calcutta and the socioeconomic decline of Bengal. He detailed these newly plebeian aesthetics in an unrhymed hundred-line poem whose technique of searing double-vision foreshadowed Satyajit Ray's film Apur Sansar.[54][55] Fifteen new volumes appeared, among them prose-poem works Punashcha (1932), Shes Saptak (1935), and Patraput (1936). Experimentation continued in his prose-songs and dance-dramas: Chitra (1914), Shyama (1939), and Chandalika (1938); and in his novels: Dui Bon (1933), Malancha (1934), and Char Adhyay (1934).

Clouds come floating into my life, no longer to carry rain or usher storm, but to add color to my sunset sky.

—Verse 292, Stray Birds, 1916.

Tagore's remit expanded to science in his last years, as hinted in Visva-Parichay, 1937 collection of essays. His respect for scientific laws and his exploration of biology, physics, and astronomy informed his poetry, which exhibited extensive naturalism and verisimilitude.[56] He wove the process of science, the narratives of scientists, into stories in Se (1937), Tin Sangi (1940), and Galpasalpa (1941). His last five years were marked by chronic pain and two long periods of illness. These began when Tagore lost consciousness in late 1937; he remained comatose and near death for a time. This was followed in late 1940 by a similar spell. He never recovered. Poetry from these valetudinary years is among his finest.[57][58] A period of prolonged agony ended with Tagore's death on 7 August 1941, aged eighty; he was in an upstairs room of the Jorasanko mansion he was raised in.[59][60] The date is still mourned.[61] A. K. Sen, brother of the first chief election commissioner, received dictation from Tagore on 30 July 1941, a day prior to a scheduled operation: his last poem.[62]

I'm lost in the middle of my birthday. I want my friends, their touch, with the earth's last love. I will take life's final offering, I will take the human's last blessing. Today my sack is empty. I have given completely whatever I had to give. In return if I receive anything—some love, some forgiveness—then I will take it with me when I step on the boat that crosses to the festival of the wordless end.

Travels

Between 1878 and 1932, Tagore set foot in more than thirty countries on five continents.[64] In 1912, he took a sheaf of his translated works to England, where they gained attention from missionary and Gandhi protégé Charles F. Andrews, Irish poet William Butler Yeats, Ezra Pound, Robert Bridges, Ernest Rhys, Thomas Sturge Moore, and others.[65] Yeats wrote the preface to the English translation of Gitanjali; Andrews joined Tagore at Santiniketan. In November 1912 Tagore began touring the United States[66] and the United Kingdom, staying in Butterton, Staffordshire with Andrews's clergymen friends.[67] From May 1916 until April 1917, he lectured in Japan and the United States.[68] He denounced nationalism.[69] His essay "Nationalism in India" was scorned and praised; it was admired by Romain Rolland and other pacifists.[70]

Our passions and desires are unruly, but our character subdues these elements into a harmonious whole. Does something similar to this happen in the physical world? Are the elements rebellious, dynamic with individual impulse? And is there a principle in the physical world which dominates them and puts them into an orderly organization?

— Interviewed by Einstein, 14 April 1930.[71]

Shortly after returning home the 63-year-old Tagore accepted an invitation from the Peruvian government. He travelled to Mexico. Each government pledged US$100,000 to his school to commemorate the visits.[72] A week after his 6 November 1924 arrival in Buenos Aires,[73] an ill Tagore shifted to the Villa Miralrío at the behest of Victoria Ocampo. He left for home in January 1925. In May 1926 Tagore reached Naples; the next day he met Mussolini in Rome.[74] Their warm rapport ended when Tagore pronounced upon Il Duce's fascist finesse.[75] He had earlier enthused: "[w]ithout any doubt he is a great personality. There is such a massive vigour in that head that it reminds one of Michael Angelo’s chisel." A "fire-bath" of fascism was to have educed "the immortal soul of Italy ... clothed in quenchless light".[76]

On 14 July 1927 Tagore and two companions began a four-month tour of Southeast Asia. They visited Bali, Java, Kuala Lumpur, Malacca, Penang, Siam, and Singapore. The resultant travelogues compose Jatri (1929).[77] In early 1930 he left Bengal for a nearly year-long tour of Europe and the United States. Upon returning to Britain—and as his paintings exhibited in Paris and London—he lodged at a Birmingham Quaker settlement. He wrote his Oxford Hibbert Lectures[ι] and spoke at the annual London Quaker meet.[78] There, addressing relations between the British and the Indians—a topic he would tackle repeatedly over the next two years—Tagore spoke of a "dark chasm of aloofness".[79] He visited Aga Khan III, stayed at Dartington Hall, toured Denmark, Switzerland, and Germany from June to mid-September 1930, then went on into the Soviet Union.[80] In April 1932 Tagore, intrigued by the Persian mystic Hafez, was hosted by Reza Shah Pahlavi.[81][82] In his other travels, Tagore interacted with Henri Bergson, Albert Einstein, Robert Frost, Thomas Mann, George Bernard Shaw, H.G. Wells, and Romain Rolland.[83][84][85] Visits to Persia and Iraq (in 1932) and Sri Lanka (in 1933) composed Tagore's final foreign tour, and his dislike of communalism and nationalism only deepened.[52] Vice President of India M. Hamid Ansari has said that Rabindranath Tagore heralded the cultural rapprochement between communities, societies and nations much before it became the liberal norm of conduct. Tagore was a man ahead of his time. He wrote in 1932, while on a visit to Iran, that "each country of Asia will solve its own historical problems according to its strength, nature and needs, but the lamp they will each carry on their path to progress will converge to illuminate the common ray of knowledge."[86] His ideas on culture, gender, poverty, education, freedom, and a resurgent Asia remain relevant today.

Works

|

|

Known mostly for his poetry, Tagore wrote novels, essays, short stories, travelogues, dramas, and thousands of songs. Of Tagore's prose, his short stories are perhaps most highly regarded; he is indeed credited with originating the Bengali-language version of the genre. His works are frequently noted for their rhythmic, optimistic, and lyrical nature. Such stories mostly borrow from deceptively simple subject matter: commoners. Tagore's non-fiction grappled with history, linguistics, and spirituality. He wrote autobiographies. His travelogues, essays, and lectures were compiled into several volumes, including Europe Jatrir Patro (Letters from Europe) and Manusher Dhormo (The Religion of Man). His brief chat with Einstein, "Note on the Nature of Reality", is included as an appendix to the latter. On the occasion of Tagore's 150th birthday an anthology (titled Kalanukromik Rabindra Rachanabali) of the total body of his works is currently being published in Bengali in chronological order. This includes all versions of each work and fills about eighty volumes.[88] In 2011, Harvard University Press collaborated with Visva-Bharati University to publish The Essential Tagore, the largest anthology of Tagore's works available in English; it was edited by Fakrul Alam and Radha Chakravarthy and marks the 150th anniversary of Tagore’s birth.[89]

Music

Tagore was a prolific composer with 2,230 songs to his credit. His songs are known as rabindrasangit ("Tagore Song"), which merges fluidly into his literature, most of which—poems or parts of novels, stories, or plays alike—were lyricised. Influenced by the thumri style of Hindustani music, they ran the entire gamut of human emotion, ranging from his early dirge-like Brahmo devotional hymns to quasi-erotic compositions.[90] They emulated the tonal color of classical ragas to varying extents. Some songs mimicked a given raga's melody and rhythm faithfully; others newly blended elements of different ragas.[91] Yet about nine-tenths of his work was not bhanga gaan, the body of tunes revamped with "fresh value" from select Western, Hindustani, Bengali folk and other regional flavours "external" to Tagore's own ancestral culture.[17] Scholars have attempted to gauge the emotive force and range of Hindustani ragas:

[...] the pathos of the purabi raga reminded Tagore of the evening tears of a lonely widow, while kanara was the confused realization of a nocturnal wanderer who had lost his way. In bhupali he seemed to hear a voice in the wind saying 'stop and come hither'.Paraj conveyed to him the deep slumber that overtook one at night’s end.[17]

Tagore influenced sitar maestro Vilayat Khan and sarodiyas Buddhadev Dasgupta and Amjad Ali Khan.[91] His songs are widely popular and undergird the Bengali ethos to an extent perhaps rivaling Shakespeare's impact on the English-speaking world. It is said that his songs are the outcome of five centuries of Bengali literary churning and communal yearning. Dhan Gopal Mukerji has said that these songs transcend the mundane to the aesthetic and express all ranges and categories of human emotion. The poet gave voice to all—big or small, rich or poor. The poor Ganges boatman and the rich landlord air their emotions in them. They birthed a distinctive school of music whose practitioners can be fiercely traditional: novel interpretations have drawn severe censure in both West Bengal and Bangladesh.

For Bengalis, the songs' appeal, stemming from the combination of emotive strength and beauty described as surpassing even Tagore's poetry, was such that the Modern Review observed that "[t]here is in Bengal no cultured home where Rabindranath's songs are not sung or at least attempted to be sung ... Even illiterate villagers sing his songs". A. H. Fox Strangways of The Observer introduced non-Bengalis to rabindrasangit in The Music of Hindostan, calling it a "vehicle of a personality ... [that] go behind this or that system of music to that beauty of sound which all systems put out their hands to seize."[94]

In 1971, Amar Shonar Bangla became the national anthem of Bangladesh. It was written—ironically—to protest the 1905 Partition of Bengal along communal lines: lopping Muslim-majority East Bengal from Hindu-dominated West Bengal was to avert a regional bloodbath. Tagore saw the partition as a ploy to upend the independence movement, and he aimed to rekindle Bengali unity and tar communalism. Jana Gana Mana was written in shadhu-bhasha, a Sanskritised register of Bengali, and is the first of five stanzas of a Brahmo hymn that Tagore composed. It was first sung in 1911 at a Calcutta session of the Indian National Congress[95] and was adopted in 1950 by the Constituent Assembly of the Republic of India as its national anthem.

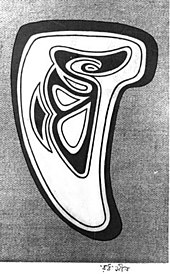

Paintings

At sixty, Tagore took up drawing and painting; successful exhibitions of his many works—which made a debut appearance in Paris upon encouragement by artists he met in the south of France[96]—were held throughout Europe. He was likely red-green color blind, resulting in works that exhibited strange colour schemes and off-beat aesthetics. Tagore was influenced by scrimshaw from northern New Ireland, Haida carvings from British Columbia, and woodcuts by Max Pechstein.[87] His artist's eye for his handwriting were revealed in the simple artistic and rhythmic leitmotifs embellishing the scribbles, cross-outs, and word layouts of his manuscripts. Some of Tagore's lyrics corresponded in a synesthetic sense with particular paintings.[17]

[...]Surrounded by several painters Rabindranath had always wanted to paint. Writing and music, playwriting and acting came to him naturally and almost without training, as it did to several others in his family, and in even greater measure. But painting eluded him. Yet he tried repeatedly to master the art and there are several references to this in his early letters and reminiscence. In 1900 for instance, when he was nearing forty and already a celebrated writer, he wrote to Jagadishchandra Bose, "You will be surprised to hear that I am sitting with a sketchbook drawing. Needless to say, the pictures are not intended for any salon in Paris, they cause me not the least suspicion that the national gallery of any country will suddenly decide to raise taxes to acquire them. But, just as a mother lavishes most affection on her ugliest son, so I feel secretly drawn to the very skill that comes to me least easily.‟ He also realized that he was using the eraser more than the pencil, and dissatisfied with the results he finally withdrew, deciding it was not for him to become a painter.[97]

— R. Siva Kumar, The Last Harvest : Paintings of Rabindranath Tagore.[98]

Rabindra Chitravali, edited by noted art historian R. Siva Kumar, for the first time makes the paintings of Tagore accessible to art historians and scholars of Rabindranth with critical annotations and comments It also brings together a selection of Rabindranath’s own statements and documents relating to the presentation and reception of his paintings during his lifetime.[99]

The Last Harvest : Paintings of Rabindranath Tagore was an exhibition of Rabindranath Tagore's paintings to mark the 150th birth anniversary of Rabindranath Tagore. It was commissioned by the Ministry of Culture, India and organized with NGMA Delhi as the nodal agency. It consisted of 208 paintings drawn from the collections of Visva Bharati and the NGMA and presented Tagore's art in a very comprehensive way. The exhibition was curated by Art Historian R. Siva Kumar. Within the 150th birth anniversary year it was conceived as three separate but similar exhibitions,and travelled simultaneously in three circuits. The first selection was shown at Museum of Asian Art, Berlin,[100] Asia Society, New York,[101] National Museum of Korea,[102] Seoul, Victoria and Albert Museum,[103] London, The Art Institute of Chicago,[104] Chicago, Petit Palais,[105] Paris, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Moderna, Rome, National Visual Arts Gallery (Malaysia),[106] Kuala Lumpur, McMichael Canadian Art Collection,[107] Ontario, National Gallery of Modern Art,[108] New Delhi

Theatre

At sixteen, Tagore led his brother Jyotirindranath's adaptation of Molière's Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme.[109] At twenty he wrote his first drama-opera: Valmiki Pratibha (The Genius of Valmiki). In it the pandit Valmiki overcomes his sins, is blessed by Saraswati, and compiles the Rāmāyana.[110] Through it Tagore explores a wide range of dramatic styles and emotions, including usage of revamped kirtans and adaptation of traditional English and Irish folk melodies as drinking songs.[111] Another play, Dak Ghar (The Post Office), describes the child Amal defying his stuffy and puerile confines by ultimately "fall[ing] asleep", hinting his physical death. A story with borderless appeal—gleaning rave reviews in Europe—Dak Ghar dealt with death as, in Tagore's words, "spiritual freedom" from "the world of hoarded wealth and certified creeds".[112][113] In the Nazi-besieged Warsaw Ghetto, Polish doctor-educator Janusz Korczak had orphans in his care stage The Post Office in July 1942.[114] In The King of Children, biographer Betty Jean Lifton suspected that Korczak, agonising over whether one should determine when and how to die, was easing the children into accepting death.[115][116][117] In mid-October, the Nazis sent them to Treblinka.[118]

[I]n days long gone by [...] I can see [...] the King's postman coming down the hillside alone, a lantern in his left hand and on his back a bag of letters climbing down for ever so long, for days and nights, and where at the foot of the mountain the waterfall becomes a stream he takes to the footpath on the bank and walks on through the rye; then comes the sugarcane field and he disappears into the narrow lane cutting through the tall stems of sugarcanes; then he reaches the open meadow where the cricket chirps and where there is not a single man to be seen, only the snipe wagging their tails and poking at the mud with their bills. I can feel him coming nearer and nearer and my heart becomes glad.

— Amal in The Post Office, 1914.[119]

[...] but the meaning is less intellectual, more emotional and simple. The deliverance sought and won by the dying child is the same deliverance which rose before his imagination, [...] when once in the early dawn he heard, amid the noise of a crowd returning from some festival, this line out of an old village song, "Ferryman, take me to the other shore of the river." It may come at any moment of life, though the child discovers it in death, for it always comes at the moment when the "I", seeking no longer for gains that cannot be "assimilated with its spirit", is able to say, "All my work is thine" [...].[120]

— W. B. Yeats, Preface, The Post Office, 1914.

His other works fuse lyrical flow and emotional rhythm into a tight focus on a core idea, a break from prior Bengali drama. Tagore sought "the play of feeling and not of action". In 1890 he released what is regarded as his finest drama: Visarjan (Sacrifice).[110] It is an adaptation of Rajarshi, an earlier novella of his. "A forthright denunciation of a meaningless [and] cruel superstitious rite[s]",[121] the Bengali originals feature intricate subplots and prolonged monologues that give play to historical events in seventeenth-century Udaipur. The devout Maharaja of Tripura is pitted against the wicked head priest Raghupati. His latter dramas were more philosophical and allegorical in nature; these included Dak Ghar. Another is Tagore's Chandalika (Untouchable Girl), which was modeled on an ancient Buddhist legend describing how Ananda, the Gautama Buddha's disciple, asks a tribal girl for water.[122]

In Raktakarabi ("Red" or "Blood Oleanders"), a kleptocrat rules over the residents of Yakshapuri. He and his retainers exploit his subjects—who are benumbed by alcohol and numbered like inventory—by forcing them to mine gold for him. The naive maiden-heroine Nandini rallies her subject-compatriots to defeat the greed of the realm's sardar class—with the morally roused king's belated help. Skirting the "good-vs-evil" trope, the work pits a vital and joyous lèse majesté against the monotonous fealty of the king's varletry, giving rise to an allegorical struggle akin to that found in Animal Farm or Gulliver's Travels.[123] The original, though prized in Bengal, long failed to spawn a "free and comprehensible" translation, and its archaic and sonorous didacticism failed to attract interest from abroad.[3] Chitrangada, Chandalika, and Shyama are other key plays that have dance-drama adaptations, which together are known as Rabindra Nritya Natya.

Novels

Tagore wrote eight novels and four novellas, among them Chaturanga, Shesher Kobita, Char Odhay, and Noukadubi. Ghare Baire (The Home and the World)—through the lens of the idealistic zamindar protagonist Nikhil—excoriates rising Indian nationalism, terrorism, and religious zeal in the Swadeshi movement; a frank expression of Tagore's conflicted sentiments, it emerged out of a 1914 bout of depression. The novel ends in Hindu-Muslim violence and Nikhil's—likely mortal—wounding.[124]

Gora raises controversial questions regarding the Indian identity. As with Ghare Baire, matters of self-identity (jāti), personal freedom, and religion are developed in the context of a family story and love triangle.[125] In it an Irish boy orphaned in the Sepoy Mutiny is raised by Hindus as the titular gora—"whitey". Ignorant of his foreign origins, he chastises Hindu religious backsliders out of love for the indigenous Indians and solidarity with them against his hegemon-compatriots. He falls for a Brahmo girl, compelling his worried foster father to reveal his lost past and cease his nativist zeal. As a "true dialectic" advancing "arguments for and against strict traditionalism", it tackles the colonial conundrum by "portray[ing] the value of all positions within a particular frame [...] not only syncretism, not only liberal orthodoxy, but the extremest reactionary traditionalism he defends by an appeal to what humans share." Among these Tagore highlights "identity [...] conceived of as dharma."[126]

In Jogajog (Relationships), the heroine Kumudini—bound by the ideals of Śiva-Sati, exemplified by Dākshāyani—is torn between her pity for the sinking fortunes of her progressive and compassionate elder brother and his foil: her roue of a husband. Tagore flaunts his feminist leanings; pathos depicts the plight and ultimate demise of women trapped by pregnancy, duty, and family honour; he simultaneously trucks with Bengal's putrescent landed gentry.[127] The story revolves around the underlying rivalry between two families—the Chatterjees, aristocrats now on the decline (Biprodas) and the Ghosals (Madhusudan), representing new money and new arrogance. Kumudini, Biprodas' sister, is caught between the two as she is married off to Madhusudan. She had risen in an observant and sheltered traditional home, as had all her female relations.

Others were uplifting: Shesher Kobita—translated twice as Last Poem and Farewell Song—is his most lyrical novel, with poems and rhythmic passages written by a poet protagonist. It contains elements of satire and postmodernism and has stock characters who gleefully attack the reputation of an old, outmoded, oppressively renowned poet who, incidentally, goes by a familiar name: "Rabindranath Tagore". Though his novels remain among the least-appreciated of his works, they have been given renewed attention via film adaptations by Ray and others: Chokher Bali and Ghare Baire are exemplary. In the first, Tagore inscribes Bengali society via its heroine: a rebellious widow who would live for herself alone. He pillories the custom of perpetual mourning on the part of widows, who were not allowed to remarry, who were consigned to seclusion and loneliness. Tagore wrote of it: "I have always regretted the ending".

Stories

Tagore's three-volume Galpaguchchha comprises eighty-four stories that reflect upon the author's surroundings, on modern and fashionable ideas, and on mind puzzles.[29] Tagore associated his earliest stories, such as those of the "Sadhana" period, with an exuberance of vitality and spontaneity; these traits were cultivated by zamindar Tagore’s life in Patisar, Shajadpur, Shelaidaha, and other villages.[29] Seeing the common and the poor, he examined their lives with a depth and feeling singular in Indian literature up to that point.[128] In "The Fruitseller from Kabul", Tagore speaks in first person as a town dweller and novelist imputing exotic perquisites to an Afghan seller. He channels the lucubrative lust of those mired in the blasé, nidorous, and sudorific morass of subcontinental city life: for distant vistas. "There were autumn mornings, the time of year when kings of old went forth to conquest; and I, never stirring from my little corner in Calcutta, would let my mind wander over the whole world. At the very name of another country, my heart would go out to it [...] I would fall to weaving a network of dreams: the mountains, the glens, the forest [...]."[129]

The Golpoguchchho (Bunch of Stories) was written in Tagore's Sabuj Patra period, which lasted from 1914 to 1917 and was named for another of his magazines.[29] These yarns are celebrated fare in Bengali fiction and are commonly used as plot fodder by Bengali film and theatre. The Ray film Charulata echoed the controversial Tagore novella Nastanirh (The Broken Nest). In Atithi, which was made into another film, the little Brahmin boy Tarapada shares a boat ride with a village zamindar. The boy relates his flight from home and his subsequent wanderings. Taking pity, the elder adopts him; he fixes the boy to marry his own daughter. The night before his wedding, Tarapada runs off—again. Strir Patra (The Wife's Letter) is an early treatise in female emancipation.[130] Mrinal is wife to a Bengali middle class man: prissy, preening, and patriarchal. Travelling alone she writes a letter, which comprehends the story. She details the pettiness of a life spent entreating his viraginous virility; she ultimately gives up married life, proclaiming, Amio bachbo. Ei bachlum: "And I shall live. Here, I live."

Haimanti assails Hindu arranged marriage and spotlights their often dismal domesticity, the hypocrisies plaguing the Indian middle classes, and how Haimanti, a young woman, due to her insufferable sensitivity and free spirit, foredid herself. In the last passage Tagore blasts the reification of Sita's self-immolation attempt; she had meant to appease her consort Rama's doubts of her chastity. Musalmani Didi eyes recrudescent Hindu-Muslim tensions and, in many ways, embodies the essence of Tagore's humanism. The somewhat auto-referential Darpaharan describes a fey young man who harbours literary ambitions. Though he loves his wife, he wishes to stifle her literary career, deeming it unfeminine. In youth Tagore likely agreed with him. Darpaharan depicts the final humbling of the man as he ultimately acknowledges his wife's talents. As do many other Tagore stories, Jibito o Mrito equips Bengalis with a ubiquitous epigram: Kadombini moriya proman korilo she more nai—"Kadombini died, thereby proving that she hadn't."

Poetry

Tagore's poetic style, which proceeds from a lineage established by 15th- and 16th-century Vaishnava poets, ranges from classical formalism to the comic, visionary, and ecstatic. He was influenced by the atavistic mysticism of Vyasa and other rishi-authors of the Upanishads, the Bhakti-Sufi mystic Kabir, and Ramprasad Sen.[131] Tagore's most innovative and mature poetry embodies his exposure to Bengali rural folk music, which included mystic Baul ballads such as those of the bard Lalon.[132][133] These, rediscovered and repopularised by Tagore, resemble 19th-century Kartābhajā hymns that emphasise inward divinity and rebellion against bourgeois bhadralok religious and social orthodoxy.[134][135] During his Shelaidaha years, his poems took on a lyrical voice of the moner manush, the Bāuls' "man within the heart" and Tagore's "life force of his deep recesses", or meditating upon the jeevan devata—the demiurge or the "living God within".[17] This figure connected with divinity through appeal to nature and the emotional interplay of human drama. Such tools saw use in his Bhānusiṃha poems chronicling the Radha-Krishna romance, which were repeatedly revised over the course of seventy years.[136][137]

The time that my journey takes is long and the way of it long.

I came out on the chariot of the first gleam of light, and pursued my voyage through the wildernesses of worlds leaving my track on many a star and planet.

It is the most distant course that comes nearest to thyself, and that training is the most intricate which leads to the utter simplicity of a tune.

The traveller has to knock at every alien door to come to his own, and one has to wander through all the outer worlds to reach the innermost shrine at the end.

My eyes strayed far and wide before I shut them and said 'Here art thou!'

The question and the cry 'Oh, where?' melt into tears of a thousand streams and deluge the world with the flood of the assurance 'I am!'

— Song XII, Gitanjali, 1913.[138]

Tagore reacted to the halfhearted uptake of modernist and realist techniques in Bengali literature by writing matching experimental works in the 1930s.[139] These include Africa and Camalia, among the better known of his latter poems. He occasionally wrote poems using Shadhu Bhasha, a Sanskritised dialect of Bengali; he later adopted a more popular dialect known as Cholti Bhasha. Other works include Manasi, Sonar Tori (Golden Boat), Balaka (Wild Geese, a name redolent of migrating souls),[140] and Purobi. Sonar Tori's most famous poem, dealing with the fleeting endurance of life and achievement, goes by the same name; hauntingly it ends: Shunno nodir tire rohinu poŗi / Jaha chhilo loe gêlo shonar tori—"all I had achieved was carried off on the golden boat—only I was left behind." Gitanjali (গীতাঞ্জলি) is Tagore's best-known collection internationally, earning him his Nobel.[141]

|

|

Song VII of Gitanjali:

|

আমার এ গান ছেড়েছে তার |

|

Tagore's free-verse translation:

My song has put off her adornments.

She has no pride of dress and decoration.

Ornaments would mar our union; they would come

between thee and me; their jingling would drown thy whispers.

My poet's vanity dies in shame before thy sight.

O master poet, I have sat down at thy feet.

Only let me make my life simple and straight,

like a flute of reed for thee to fill with music.[142]

"Klanti" (ক্লান্তি; "Weariness"):

|

ক্লান্তি আমার ক্ষমা করো প্রভু, |

|

Gloss by Tagore scholar Reba Som:

Forgive me my weariness O Lord

Should I ever lag behind

For this heart that this day trembles so

And for this pain, forgive me, forgive me, O Lord

For this weakness, forgive me O Lord,

If perchance I cast a look behind

And in the day's heat and under the burning sun

The garland on the platter of offering wilts,

For its dull pallor, forgive me, forgive me O Lord.[143]

Tagore's poetry has been set to music by composers: Arthur Shepherd's triptych for soprano and string quartet, Alexander Zemlinsky's famous Lyric Symphony, Josef Bohuslav Foerster's cycle of love songs, Leoš Janáček's famous chorus "Potulný šílenec" ("The Wandering Madman") for soprano, tenor, baritone, and male chorus—JW 4/43—inspired by Tagore's 1922 lecture in Czechoslovakia which Janáček attended, and Garry Schyman's "Praan", an adaptation of Tagore's poem "Stream of Life" from Gitanjali. The latter was composed and recorded with vocals by Palbasha Siddique to accompany Internet celebrity Matt Harding's 2008 viral video.[144] In 1917 his words were translated adeptly and set to music by Anglo-Dutch composer Richard Hageman to produce a highly regarded art song: "Do Not Go, My Love". The second movement of Jonathan Harvey's "One Evening" (1994) sets an excerpt beginning "As I was watching the sunrise ..." from a letter of Tagore's, this composer having previously chosen a text by the poet for his piece "Song Offerings" (1985).[145]

Politics

Tagore's political thought was tortuous. He opposed imperialism and supported Indian nationalists,[146][147][148] and these views were first revealed in Manast, which was mostly composed in his twenties.[40] Evidence produced during the Hindu–German Conspiracy Trial and latter accounts affirm his awareness of the Ghadarites, and stated that he sought the support of Japanese Prime Minister Terauchi Masatake and former Premier Ōkuma Shigenobu.[149] Yet he lampooned the Swadeshi movement; he rebuked it in "The Cult of the Charka", an acrid 1925 essay.[150] He urged the masses to avoid victimology and instead seek self-help and education, and he saw the presence of British administration as a "political symptom of our social disease". He maintained that, even for those at the extremes of poverty, "there can be no question of blind revolution"; preferable to it was a "steady and purposeful education".[151][152]

So I repeat we never can have a true view of man unless we have a love for him. Civilisation must be judged and prized, not by the amount of power it has developed, but by how much it has evolved and given expression to, by its laws and institutions, the love of humanity.

— Sādhanā: The Realisation of Life, 1916.[153]

Such views enraged many. He escaped assassination—and only narrowly—by Indian expatriates during his stay in a San Francisco hotel in late 1916; the plot failed when his would-be assassins fell into argument.[154] Yet Tagore wrote songs lionising the Indian independence movement[155] Two of Tagore's more politically charged compositions, "Chitto Jetha Bhayshunyo" ("Where the Mind is Without Fear") and "Ekla Chalo Re" ("If They Answer Not to Thy Call, Walk Alone"), gained mass appeal, with the latter favoured by Gandhi.[156] Though somewhat critical of Gandhian activism,[157] Tagore was key in resolving a Gandhi–Ambedkar dispute involving separate electorates for untouchables, thereby mooting at least one of Gandhi's fasts "unto death".[158][159]

Repudiation of knighthood

Tagore renounced his knighthood, in response to the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in 1919. In the repudiation letter to the Viceroy, Lord Chelmsford, he wrote[1]

The time has come when badges of honour make our shame glaring in the incongruous context of humiliation, and I for my part, wish to stand, shorn, of all special distinctions, by the side of those of my countrymen who, for their so called insignificance, are liable to suffer degradation not fit for human beings.

Santiniketan and Visva-Bharati

Tagore despised rote classroom schooling: in "The Parrot's Training", a bird is caged and force-fed textbook pages—to death.[160][161] Tagore, visiting Santa Barbara in 1917, conceived a new type of university: he sought to "make Santiniketan the connecting thread between India and the world [and] a world center for the study of humanity somewhere beyond the limits of nation and geography."[154] The school, which he named Visva-Bharati,[η] had its foundation stone laid on 24 December 1918 and was inaugurated precisely three years later.[162] Tagore employed a brahmacharya system: gurus gave pupils personal guidance—emotional, intellectual, and spiritual. Teaching was often done under trees. He staffed the school, he contributed his Nobel Prize monies,[163] and his duties as steward-mentor at Santiniketan kept him busy: mornings he taught classes; afternoons and evenings he wrote the students' textbooks.[164] He fundraised widely for the school in Europe and the United States between 1919 and 1921.[165]

Impact

|

|

Every year, many events pay tribute to Tagore: Kabipranam, his birth anniversary, is celebrated by groups scattered across the globe; the annual Tagore Festival held in Urbana, Illinois; Rabindra Path Parikrama walking pilgrimages from Calcutta to Santiniketan; and recitals of his poetry, which are held on important anniversaries.[66][166][167] Bengali culture is fraught with this legacy: from language and arts to history and politics. Amartya Sen scantly deemed Tagore a "towering figure", a "deeply relevant and many-sided contemporary thinker".[167] Tagore's Bengali originals—the 1939 Rabīndra Rachanāvalī—is canonised as one of his nation's greatest cultural treasures, and he was roped into a reasonably humble role: "the greatest poet India has produced".[168]

Who are you, reader, reading my poems an hundred years hence?

I cannot send you one single flower from this wealth of the spring, one single streak of gold from yonder clouds.

Open your doors and look abroad.

From your blossoming garden gather fragrant memories of the vanished flowers of an hundred years before.

In the joy of your heart may you feel the living joy that sang one spring morning, sending its glad voice across an hundred years.

— The Gardener, 1915.[169]

Tagore was renowned throughout much of Europe, North America, and East Asia. He co-founded Dartington Hall School, a progressive coeducational institution;[170] in Japan, he influenced such figures as Nobel laureate Yasunari Kawabata.[171] Tagore's works were widely translated into English, Dutch, German, Spanish, and other European languages by Czech indologist Vincenc Lesný,[172] French Nobel laureate André Gide, Russian poet Anna Akhmatova,[173] former Turkish Prime Minister Bülent Ecevit,[174] and others. In the United States, Tagore's lecturing circuits, particularly those of 1916–1917, were widely attended and wildly acclaimed. Some controversies[θ] involving Tagore, possibly fictive, trashed his popularity and sales in Japan and North America after the late 1920s, concluding with his "near total eclipse" outside Bengal.[4] Yet a latent reverence of Tagore was discovered by an astonished Salman Rushdie during a trip to Nicaragua.[175]

By way of translations, Tagore influenced Chileans Pablo Neruda and Gabriela Mistral; Mexican writer Octavio Paz; and Spaniards José Ortega y Gasset, Zenobia Camprubí, and Juan Ramón Jiménez. In the period 1914–1922, the Jiménez-Camprubí pair produced twenty-two Spanish translations of Tagore's English corpus; they heavily revised The Crescent Moon and other key titles. In these years, Jiménez developed "naked poetry".[176] Ortega y Gasset wrote that "Tagore's wide appeal [owes to how] he speaks of longings for perfection that we all have [...] Tagore awakens a dormant sense of childish wonder, and he saturates the air with all kinds of enchanting promises for the reader, who [...] pays little attention to the deeper import of Oriental mysticism". Tagore's works circulated in free editions around 1920—alongside those of Plato, Dante, Cervantes, Goethe, and Tolstoy.

Tagore was deemed overrated by some. Graham Greene doubted that "anyone but Mr. Yeats can still take his poems very seriously." Several prominent Western admirers—including Pound and, to a lesser extent, even Yeats—criticised Tagore's work. Yeats, unimpressed with his English translations, railed against that "Damn Tagore [...] We got out three good books, Sturge Moore and I, and then, because he thought it more important to know English than to be a great poet, he brought out sentimental rubbish and wrecked his reputation. Tagore does not know English, no Indian knows English."[4][177] William Radice, who "English[ed]" his poems, asked: "What is their place in world literature?"[178] He saw him as "kind of counter-cultur[al]," bearing "a new kind of classicism" that would heal the "collapsed romantic confusion and chaos of the 20th [c]entury."[177][179] The translated Tagore was "almost nonsensical",[180] and subpar English offerings reduced his trans-national appeal:

[...] anyone who knows Tagore's poems in their original Bengali cannot feel satisfied with any of the translations (made with or without Yeats's help). Even the translations of his prose works suffer, to some extent, from distortion. E.M. Forster noted [of] The Home and the World [that] "[t]he theme is so beautiful," but the charms have "vanished in translation," or perhaps "in an experiment that has not quite come off."

— Amartya Sen, "Tagore and His India".[4]

List of works

The SNLTR hosts the 1415 BE edition of Tagore's complete Bengali works. Tagore Web also hosts an edition of Tagore's works, including annotated songs. Translations are found at Project Gutenberg and Wikisource. More sources are below.

Original

Bengali

| Poetry | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| * ভানুসিংহ ঠাকুরের পদাবলী | Bhānusiṃha Ṭhākurer Paḍāvalī | (Songs of Bhānusiṃha Ṭhākur) | 1884 |

| * মানসী | Manasi | (The Ideal One) | 1890 |

| * সোনার তরী | Sonar Tari | (The Golden Boat) | 1894 |

| * গীতাঞ্জলি | Gitanjali | (Song Offerings) | 1910 |

| * গীতিমাল্য | Gitimalya | (Wreath of Songs) | 1914 |

| * বলাকা | Balaka | (The Flight of Cranes) | 1916 |

| Dramas | |||

| * বাল্মিকী প্রতিভা | Valmiki-Pratibha | (The Genius of Valmiki) | 1881 |

| * বিসর্জন | Visarjan | (The Sacrifice) | 1890 |

| * রাজা | Raja | (The King of the Dark Chamber) | 1910 |

| * ডাকঘর | Dak Ghar | (The Post Office) | 1912 |

| * অচলায়তন | Achalayatan | (The Immovable) | 1912 |

| * মুক্তধারা | Muktadhara | (The Waterfall) | 1922 |

| * রক্তকরবী | Raktakaravi | (Red Oleanders) | 1926 |

| Fiction | |||

| * নষ্টনীড় | Nastanirh | (The Broken Nest) | 1901 |

| * গোরা | Gora | (Fair-Faced) | 1910 |

| * ঘরে বাইরে | Ghare Baire | (The Home and the World) | 1916 |

| * যোগাযোগ | Yogayog | (Crosscurrents) | 1929 |

| Memoirs | |||

| * জীবনস্মৃতি | Jivansmriti | (My Reminiscences) | 1912 |

| * ছেলেবেলা | Chhelebela | (My Boyhood Days) | 1940 |

English

Translated

English

| * Chitra | 1914[text 1] |

| * Creative Unity | 1922[text 2] |

| * The Crescent Moon | 1913[text 3] |

| * The Cycle of Spring | 1919[text 4] |

| * Fireflies | 1928 |

| * Fruit-Gathering | 1916[text 5] |

| * The Fugitive | 1921[text 6] |

| * The Gardener | 1913[text 7] |

| * Gitanjali: Song Offerings | 1912[text 8] |

| * Glimpses of Bengal | 1991[text 9] |

| * The Home and the World | 1985[text 10] |

| * The Hungry Stones | 1916[text 11] |

| * I Won't Let you Go: Selected Poems | 1991 |

| * The King of the Dark Chamber | 1914[text 12] |

| * Letters from an Expatriate in Europe | 2012[text 13] |

| * The Lover of God | 2003 |

| * Mashi | 1918[text 14] |

| * My Boyhood Days | 1943 |

| * My Reminiscences | 1991[text 15] |

| * Nationalism | 1991 |

| * The Post Office | 1914[text 16] |

| * Sadhana: The Realisation of Life | 1913[text 17] |

| * Selected Letters | 1997 |

| * Selected Poems | 1994 |

| * Selected Short Stories | 1991 |

| * Songs of Kabir | 1915[text 18] |

| * The Spirit of Japan | 1916[text 19] |

| * Stories from Tagore | 1918[text 20] |

| * Stray Birds | 1916[text 21] |

| * Vocation | 1913[181] |

Adaptations of novels and short stories in cinema

Hindi

- Sacrifice - 1927 (Balidaan) - Nanand Bhojai and Naval Gandhi

- Milan - 1947 (Nauka Dubi) - Nitin Bose

- Kabuliwala - 1961 (Kabuliwala) - Bimal Roy

- Uphaar - 1971 (Samapti) - Sudhendu Roy

- Lekin... - 1991 (Kshudhit Pashaan) - Gulzar

- Char Adhyay - 1997 (Char Adhyay) - Kumar Shahani

- Kashmakash - 2011 ((Nauka Dubi) - Rituparno Ghosh

Bengali

- Natir Puja - 1932 - The only film directed by Rabindranath Tagore

- Naukadubi - 1947 (Noukadubi) - Nitin Bose

- Kabuliwala - 1957 (Kabuliwala) - Tapan Sinha

- Kshudhita Pashaan - 1960 (Kshudhita Pashan) - Tapan Sinha

- Teen Kanya - 1961 (Teen Kanya) - Satyajit Ray

- Charulata - 1964 (Nastanirh) - Satyajit Ray

- Ghare Baire - 1985 (Ghare Baire) - Satyajit Ray

- Chokher Bali - 2003 (Chokher Bali) - Rituparno Ghosh

- Chaturanga - 2008 (Chaturanga) - Suman Mukhopadhyay

- Elar Char Adhyay - 2012 (Char Adhyay) - Bappaditya Bandyopadhyay

Notes

- ^ α: Template:Lang-bn,

pronounced [ɾobind̪ɾonat̪ʰ ʈʰakuɾ] ; Hindi: [rəʋiːnd̪rəˈnaːt̪ʰ ʈʰaːˈkʊr] . - ^ β: Romanised from Bengali script:

Robindronath Ţhakur. - ^ γ: Bengali calendar: 25 Baishakh, 1268 – 22 Srabon, 1348 (২৫শে বৈশাখ, ১২৬৮ – ২২শে শ্রাবণ, ১৩৪৮ বঙ্গাব্দ).

- ^ δ: Gurudev translates as "divine mentor".[182]

- ^ ε: Tagore was born at No. 6 Dwarkanath Tagore Lane, Jorasanko—the address of the main mansion (the Jorasanko Thakurbari) inhabited by the Jorasanko branch of the Tagore clan, which had earlier suffered an acrimonious split. Jorasanko was located in the Bengali section of Calcutta, near Chitpur Road.[183]

- ^ ζ: ... and wholly fictitious ...

- ^ η: Etymology of "Visva-Bharati": from the Sanskrit for "world" or "universe" and the name of a Rigvedic goddess ("Bharati") associated with Saraswati, the Hindu patron of learning.[162] "Visva-Bharati" also translates as "India in the World".

- ^ θ: Tagore was no stranger to controversy: his dealings with Indian nationalists Subhas Chandra Bose[4] and Rash Behari Bose,[184] his yen for Soviet Communism,[185][186] and papers confiscated from Indian nationalists in New York allegedly implicating Tagore in a plot to overthrow the Raj via German funds.[187] These destroyed Tagore's image—and book sales—in the United States.[184] His relations with and ambivalent opinion of Mussolini revolted many;[76] close friend Romain Rolland despaired that "[h]e is abdicating his role as moral guide of the independent spirits of Europe and India".[188]

- ^ ι: On the "idea of the humanity of our God, or the divinity of Man the Eternal".

Citations

- ^ a b "Tagore renounced his Knighthood in protest for Jalianwalla Bagh mass killing". The Times of India. Mumbai: Bennett, Coleman & Co. Ltd. 2011-04-13. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- ^ The Nobel Foundation.

- ^ a b O'Connell 2008.

- ^ a b c d e Sen 1997.

- ^ a b Thompson 1926, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Datta 2002, p. 2.

- ^ Kripalani 2005a, pp. 6–8.

- ^ Kripalani 2005b, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Thompson 1926, p. 12.

- ^ Tagore 1984, p. xii.

- ^ Dasgupta 1993, p. 20.

- ^ "Visva-Bharti-Facts and Figures at a Glance".

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 37.

- ^ The News Today 2011.

- ^ Roy 1977, pp. 28–30.

- ^ Tagore, Dutta & Robinson 1997, pp. 8–9.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ghosh 2011.

- ^ a b Thompson 1926, p. 20.

- ^ Tagore, Dutta & Robinson 1997, p. 10.

- ^ Thompson 1926, pp. 21–24.

- ^ Das 2009.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 48–49.

- ^ a b Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 50.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 55.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Tagore, Stewart & Twichell 2003, p. 91.

- ^ Tagore, Stewart & Twichell 2003, p. 3.

- ^ a b c d e Tagore & Chakravarty 1961, p. 45.

- ^ Tagore, Dutta & Robinson 1997, p. 265.

- ^ Tagore, Dutta & Robinson 1997, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Tagore, Dutta & Robinson 1997, p. 47.

- ^ Tagore, Dutta & Robinson 1997, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 35.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 68.

- ^ Thompson 1926, p. 31.

- ^ Tagore, Dutta & Robinson 1997, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 373.

- ^ a b Scott 2009, p. 10.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 109–111.

- ^ Chowdury, A. A. (1992), Lalon Shah, Dhaka, Bangladesh: Bangla Academy, ISBN 984-07-2597-1

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 109.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 133.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 139–140.

- ^ Hjärne 1913.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 239–240.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 242.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 308–309.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 303.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 309.

- ^ a b Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 317.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 312–313.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 335–338.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 342.

- ^ Tagore & Radice 2004, p. 28.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 338.

- ^ Indo-Asian News Service 2005.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 367.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 363.

- ^ The Daily Star 2009.

- ^ Sigi 2006, p. 89.

- ^ Flickr 2006.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 374–376.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 178–179.

- ^ a b University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

- ^ Tagore & Chakravarty 1961, p. 1–2.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 206.

- ^ Hogan & Pandit 2003, pp. 56–58.

- ^ Tagore & Chakravarty 1961, p. 182.

- ^ Tagore 1930, pp. 222–225.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 253.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 256.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 267.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 270–271.

- ^ a b Kundu 2009.

- ^ Tagore & Chakravarty 1961, p. 1.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 289–292.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 303–304.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 292–293.

- ^ Tagore & Chakravarty 1961, p. 2.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 315.

- ^ South Asian Women's Forum.

- ^ Tagore & Chakravarty 1961, p. 99.

- ^ Tagore & Chakravarty 1961, pp. 100–103.

- ^ "Vice President speaks on Rabindranath Tagore | 17033". Newkerala.com. Retrieved September 5, 2012.

- ^ a b Dyson 2001.

- ^ Pandey 2011.

- ^ The Essential Tagore, Harvard University Press, retrieved 19 December 2011

- ^ Tagore, Dutta & Robinson 1997, p. 94.

- ^ a b Dasgupta 2001.

- ^ Som 2010, p. 38.

- ^ "Tabu mone rekho" (in Bengali). http://tagoreweb.in/. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ Tagore, Dutta & Robinson 1997, p. 359.

- ^ Monish R. Chatterjee (13). "Tagore and Jana Gana Mana". http://www.countercurrents.org.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); External link in|publisher=|month=ignored (help) - ^ Tagore, Dutta & Robinson 1997, p. 222.

- ^ [[#CITEREFR._Siva_Kumar2011|R. Siva Kumar 2011]].

- ^ R. Siva Kumar 2012.

- ^ http://rabindranathtagore-150.gov.in/chitravali.html

- ^ "Staatliche Museen zu Berlin - Kalender". Smb.museum. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- ^ Current Exhibitions Upcoming Exhibitions Past Exhibitions. "Rabindranath Tagore: The Last Harvest | New York". Asia Society. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- ^ "Exhibitions | Special Exhibitions". Museum.go.kr. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- ^ "Rabindranath Tagore: Poet and Painter - Victoria and Albert Museum". Vam.ac.uk. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- ^ http://www.artic.edu/sites/default/files/press_pdf/Tagore.pdf

- ^ "Le Petit Palais - Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) - Paris.fr". Petitpalais.paris.fr. 2012-03-11. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- ^ "Welcome to High Commission of India, Kuala Lumpur (Malaysia)". Indianhighcommission.com.my. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- ^ "McMichael Canadian Art Collection > The Last Harvest: Paintings by Rabindranath Tagore". Mcmichael.com. 2012-07-15. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- ^ http://www.ngmaindia.gov.in/pdf/The-Last-Harvest-e-INVITE.pdf

- ^ Lago 1977, p. 15.

- ^ a b Tagore & Chakravarty 1961, p. 123.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Tagore, Dutta & Robinson 1997, pp. 21–23.

- ^ Tagore & Chakravarty 1961, pp. 123–124.

- ^ Lifton & Wiesel 1997, p. 321.

- ^ Lifton & Wiesel 1997, pp. 416–417.

- ^ Lifton & Wiesel 1997, pp. 318–321.

- ^ Lifton & Wiesel 1997, pp. 385–386.

- ^ Lifton & Wiesel 1997, p. 349.

- ^ Tagore & Mukerjea 1914, p. 68.

- ^ Tagore & Mukerjea 1914, pp. v–vi.

- ^ Ayyub 1980, p. 48.

- ^ Tagore & Chakravarty 1961, p. 124.

- ^ Ray 2007, pp. 147–148.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 192–194.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 154–155.

- ^ Hogan 2000, pp. 213–214.

- ^ Mukherjee 2004.

- ^ Tagore & Chakravarty 1961, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Tagore & Chakravarty 1961, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Ray 2007, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Roy 1977, p. 201.

- ^ Tagore, Stewart & Twichell 2003, p. 94.

- ^ Urban 2001, p. 18.

- ^ Urban 2001, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Urban 2001, p. 16.

- ^ Tagore, Stewart & Twichell 2003, p. 95.

- ^ Tagore, Stewart & Twichell 2003, p. 7.

- ^ Prasad & Sarkar 2008, p. 125.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 281.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 192.

- ^ Tagore, Stewart & Twichell 2003, pp. 95–96.

- ^ Tagore 1952, p. 5.

- ^ Tagore, Alam & Chakravarty 2011, p. 323.

- ^ Harding 2008.

- ^ Harvey 1999, pp. 59, 90.

- ^ Tagore, Dutta & Robinson 1997, p. 127.

- ^ Tagore, Dutta & Robinson 1997, p. 210.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 304.

- ^ Brown 1948, p. 306.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 261.

- ^ Tagore, Dutta & Robinson 1997, pp. 239–240.

- ^ Tagore & Chakravarty 1961, p. 181.

- ^ Tagore 1916, p. 111.

- ^ a b Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 204.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 215–216.

- ^ Chakraborty & Bhattacharya 2001, p. 157.

- ^ Mehta 1999.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 306–307.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 339.

- ^ Tagore, Dutta & Robinson 1997, p. 267.

- ^ Tagore & Pal 2004.

- ^ a b Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 220.

- ^ Roy 1977, p. 175.

- ^ Tagore & Chakravarty 1961, p. 27.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 221.

- ^ Chakrabarti 2001.

- ^ a b Hatcher 2001.

- ^ Kämpchen 2003.

- ^ Tagore & Ray 2007, p. 104.

- ^ Farrell 2000, p. 162.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 202.

- ^ Cameron 2006.

- ^ Sen 2006, p. 90.

- ^ Kinzer 2006.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 255.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 254–255.

- ^ a b Bhattacharya 2001.

- ^ Tagore & Radice 2004, p. 26.

- ^ Tagore & Radice 2004, pp. 26–31.

- ^ Tagore & Radice 2004, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Vocation, Ratna Sagar, 2007, p. 64, ISBN 81-8332-175-5

- ^ Sil 2005.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 34.

- ^ a b Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 214.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 297.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 214–215.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 212.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 273.

References

Primary

Anthologies

- Tagore, Rabindranath (1952), Collected Poems and Plays of Rabindranath Tagore, Macmillan Publishing (published January 1952), ISBN 978-0-02-615920-3

{{citation}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Tagore, Rabindranath (1984), Some Songs and Poems from Rabindranath Tagore, East-West Publications, ISBN 978-0-85692-055-4

{{citation}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Tagore; Fakrul Alam (editor); Radha Chakravarty (editor)., Rabindranath; Alam, F. (editor); Chakravarty, R. (editor) (2011), The Essential Tagore, Harvard University Press (published 15 April 2011), p. 323, ISBN 978-0-674-05790-6

{{citation}}:|last=has generic name (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|last2=at position 1 (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|last3=at position 1 (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Tagore; Amiya Chakravarty (editor)., Rabindranath; Chakravarty, A. (editor) (1961), A Tagore Reader, Beacon Press (published 1 June 1961), ISBN 978-0-8070-5971-5

{{citation}}:|last=has generic name (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|last2=at position 1 (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Tagore; Krishna Dutta (editor); W. Andrew Robinson (editor)., Rabindranath; Dutta, K. (editor); Robinson, A. (editor) (1997), Selected Letters of Rabindranath Tagore, Cambridge University Press (published 28 June 1997), ISBN 978-0-521-59018-1

{{citation}}:|last=has generic name (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|last2=at position 1 (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|last3=at position 1 (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Tagore; Krishna Dutta (editor); W. Andrew Robinson (editor)., Rabindranath; Dutta, K. (editor); Robinson, A. (editor) (1997), Rabindranath Tagore: An Anthology, Saint Martin's Press (published November 1997), ISBN 978-0-312-16973-2

{{citation}}:|last=has generic name (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|last2=at position 1 (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|last3=at position 1 (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Tagore; Mohit K. Ray (editor)., Rabindranath; Ray, M. K. (editor) (2007), The English Writings of Rabindranath Tagore, vol. 1, Atlantic Publishing (published 10 June 2007), ISBN 978-81-269-0664-2

{{citation}}:|last=has generic name (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|last2=at position 1 (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

Originals

- Tagore., Rabindranath (1916), Sādhanā: The Realisation of Life, Macmillan

{{citation}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Tagore., Rabindranath (1930), The Religion of Man, Macmillan

{{citation}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

Translations

- Tagore; Devabrata Mukerjea (translator)., Rabindranath; Mukerjea, D. (translator) (1914), The Post Office, London: Macmillan

{{citation}}:|last=has generic name (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|last2=at position 1 (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Tagore; Palash Baran Pal (translator)., Rabindranath; Pal, P. B. (translator) (2004), "The Parrot's Tale", Parabaas (published 1 December 2004)

{{citation}}:|last=has generic name (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|last2=at position 1 (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Tagore; William Radice (translator)., Rabindranath; Radice, W. (translator) (1995), Rabindranath Tagore: Selected Poems (1st ed.), London: Penguin (published 1 June 1995), ISBN 978-0-14-018366-5

{{citation}}:|last=has generic name (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|last2=at position 1 (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Tagore; William Radice (translator)., Rabindranath; Radice, W (translator) (2004), Particles, Jottings, Sparks: The Collected Brief Poems, Angel Books (published 28 December 2004), ISBN 978-0-946162-66-6

{{citation}}:|last=has generic name (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|last2=at position 1 (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Tagore; Tony K. Stewart (translator); Chase Twichell (translator)., Rabindranath; Stewart, T. K. (translator); Twichell, C. (translator) (2003), Rabindranath Tagore: Lover of God, Lannan Literary Selections, Copper Canyon Press (published 1 November 2003), ISBN 978-1-55659-196-9

{{citation}}:|last=has generic name (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|last2=at position 1 (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|last3=at position 1 (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

Secondary

Articles

- Bhattacharya, S. (2001), Translating Tagore, The Hindu (published 2 September 2001), retrieved 9 September 2011

{{citation}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Brown, G. T. (1948), "The Hindu Conspiracy: 1914–1917", The Pacific Historical Review, 17 (3), University of California Press (published August 1948): 299–310, ISSN 0030-8684

{{citation}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Cameron, R. (2006), "Exhibition of Bengali Film Posters Opens in Prague", Radio Prague (published 31 March 2006), retrieved 29 September 2011

{{citation}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Chakrabarti, I. (2001), "A People's Poet or a Literary Deity?", Parabaas (published 15 July 2001), retrieved 17 September 2011

{{citation}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Das, S. (2009), Tagore’s Garden of Eden (published 2 August 2009), retrieved 29 September 2011

{{citation}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Dasgupta, A. (2001), "Rabindra-Sangeet as a Resource for Indian Classical Bandishes", Parabaas (published 15 July 2001), retrieved 17 September 2011

{{citation}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Dyson, K. K. (2001), "Rabindranath Tagore and His World of Colours", Parabaas (published 15 July 2001), retrieved 26 November 2009

{{citation}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Frenz, H. (1969), Rabindranath Tagore—Biography, Nobel Foundation, retrieved 30 August 2011

{{citation}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Ghosh, B. (2011), "Inside the World of Tagore's Music", Parabaas (published August 2011), retrieved 17 September 2011

{{citation}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Harvey, J. (1999), In Quest of Spirit: Thoughts on Music, University of California Press, retrieved 10 September 2011

{{citation}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Hatcher, B. A. (2001), "Aji Hote Satabarsha Pare: What Tagore Says to Us a Century Later", Parabaas (published 15 July 2001), retrieved 28 September 2011

{{citation}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Hjärne, H. (1913), The Nobel Prize in Literature 1913: Rabindranath Tagore—Award Ceremony Speech, Nobel Foundation (published 10 December 1913), retrieved 17 September 2011

{{citation}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Jha, N. (1994), "Rabindranath Tagore" (PDF), PROSPECTS: The Quarterly Review of Education, 24 (3/4), Paris: UNESCO: International Bureau of Education: 603–19, retrieved 30 August 2011

{{citation}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Kämpchen, M. (2003), "Rabindranath Tagore in Germany", Parabaas (published 25 July 2003), retrieved 28 September 2011

{{citation}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Kinzer, S. (2006), "Bülent Ecevit, Who Turned Turkey Toward the West, Dies", The New York Times (published 5 November 2006), retrieved 28 September 2011

{{citation}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Kundu, K. (2009), "Mussolini and Tagore", Parabaas (published 7 May 2009), retrieved 17 September 2011

{{citation}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Mehta, S. (1999), The First Asian Nobel Laureate, Time (published 23 August 1999), retrieved 30 August 2011

{{citation}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Meyer, L. (2004), "Tagore in The Netherlands", Parabaas (published 15 July 2004), retrieved 30 August 2011

{{citation}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Mukherjee, M. (2004), "Yogayog ("Nexus") by Rabindranath Tagore: A Book Review", Parabaas (published 25 March 2004), retrieved 29 September 2011

{{citation}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Pandey, J. M. (2011), Original Rabindranath Tagore Scripts in Print Soon, Times of India (published 8 August 2011), retrieved 1 September 2011

{{citation}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - O'Connell, K. M. (2008), "Red Oleanders (Raktakarabi) by Rabindranath Tagore—A New Translation and Adaptation: Two Reviews", Parabaas (published December 2008), retrieved 28 September 2011

{{citation}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Radice, W. (2003), "Tagore's Poetic Greatness", Parabaas (published 7 May 2003), retrieved 30 August 2011

{{citation}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Robinson, A., "Rabindranath Tagore", Encyclopædia Britannica, retrieved 30 August 2011

{{citation}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Sen, A. (1997), "Tagore and His India", The New York Review of Books, retrieved 30 August 2011

{{citation}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Sil, N. P. (2005), "Devotio Humana: Rabindranath's Love Poems Revisited", Parabaas (published 15 February 2005), retrieved 13 August 2009

{{citation}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

Books

- Ayyub, A. S. (1980), Tagore's Quest, Papyrus

{{citation}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|last=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Chakraborty, S. K.; Bhattacharya, P. (2001), Leadership and Power: Ethical Explorations, Oxford University Press (published 16 August 2001), ISBN 978-0-19-565591-9