Kashmir

34°30′N 76°00′E / 34.5°N 76°E

Kashmir is the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term "Kashmir" denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal Range. Today, the term encompasses a larger area that includes the Indian-administered territories of Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh, the Pakistani-administered territories of Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan, and Chinese-administered territories of Aksai Chin and the Trans-Karakoram Tract.[1][2][3]

In the first half of the first millennium, the Kashmir region became an important centre of Hinduism and later of Buddhism; later still, in the ninth century, Kashmir Shaivism arose.[4] In 1339, Shah Mir became the first Muslim ruler of Kashmir, inaugurating the Salatin-i-Kashmir or Shah Mir dynasty.[5] Kashmir was part of the Mughal Empire from 1586 to 1751,[6] and thereafter, until 1820, of the Afghan Durrani Empire.[5] That year, the Sikhs, under Ranjit Singh, annexed Kashmir.[5] In 1846, after the Sikh defeat in the First Anglo-Sikh War, and upon the purchase of the region from the British under the Treaty of Amritsar, the Raja of Jammu, Gulab Singh, became the new ruler of Kashmir. The rule of his descendants, under the paramountcy (or tutelage) of the British Crown, lasted until the partition of India in 1947, when the former princely state of the British Indian Empire became a disputed territory, now administered by three countries: India, Pakistan, and China.[1][2]

Etymology

The word Kashmir was derived from the ancient Sanskrit language and was referred to as káśmīra.[7] The Nilamata Purana describes the valley's origin from the waters, a lake called Sati-saras.[8][9] A popular local etymology of Kashmira is that it is land desiccated from water.[10] Geologists agree that the Valley was formerly a lake, and the lake drained through the gap of Baramulla (Varahamula)[11] which matches with the Hindu legends.[12]

An alternative etymology derives the name from the name of the Vedic sage Kashyapa who is believed to have settled people in this land. Accordingly, Kashmir would be derived from either kashyapa-mir (Kashyapa's Lake) or kashyapa-meru (Kashyapa's Mountain).[10]

The word has been referenced to in a Hindu scripture mantra worshipping the Hindu goddess Sharada and is mentioned to have resided in the land of kashmira, or which might have been a reference to the Sharada Peeth.

The Ancient Greeks called the region Kasperia, which has been identified with Kaspapyros of Hecataeus of Miletus (apud Stephanus of Byzantium) and Kaspatyros of Herodotus (3.102, 4.44). Kashmir is also believed to be the country meant by Ptolemy's Kaspeiria.[13] The earliest text which directly mentions the name Kashmir is in Ashtadhyayi written by the Sanskrit grammarian Pāṇini during the 5th century BC. Pāṇini called the people of Kashmir Kashmirikas.[14][15][16] Some other early references to Kashmir can also be found in Mahabharata in Sabha Parva and in puranas like Matsya Purana, Vayu Purana, Padma Purana and Vishnu Purana and Vishnudharmottara Purana.[17]

Huientsang, the Buddhist scholar and Chinese traveller, called Kashmir kia-shi-milo, while some other Chinese accounts referred to Kashmir as ki-pin (or Chipin or Jipin) and ache-pin.[15]

Cashmere is an archaic spelling of modern Kashmir, and in some countries[which?] it is still spelled this way.

In the Kashmiri language, Kashmir itself is known as Kasheer.[18]

Terminology

The Government of India and Indian sources, refer to the territory under Pakistan control "Pakistan-occupied Kashmir" ("POK") or "Pakistan-held Kashmir" ("PHK").[19][20] The Government of Pakistan and Pakistani sources refer to the portion of Kashmir administered by India as "Indian-occupied Kashmir" ("IOK") or "Indian-held Kashmir" (IHK);[21][22] The terms "Indian-administered Kashmir" and "Pakistani-administered Kashmir" are often used by neutral sources for the parts of the Kashmir region controlled by each country.[23]

History

Hinduism and Buddhism in Kashmir

During the ancient and medieval periods, Kashmir was an important centre for the development of a Hindu-Buddhist syncretism, in which Madhyamaka and Yogachara were blended with Shaivism and Advaita Vedanta. The Buddhist Mauryan emperor Ashoka is often credited with having founded the old capital of Kashmir, Shrinagari, now ruins on the outskirts of modern Srinagar. Kashmir was long a stronghold of Buddhism.[24] As a Buddhist seat of learning, the Sarvastivada school strongly influenced Kashmir.[25] East and Central Asian Buddhist monks are recorded as having visited the kingdom. In the late 4th century CE, the famous Kuchanese monk Kumārajīva, born to an Indian noble family, studied Dīrghāgama and Madhyāgama in Kashmir under Bandhudatta. He later became a prolific translator who helped take Buddhism to China. His mother Jīva is thought to have retired to Kashmir. Vimalākṣa, a Sarvāstivādan Buddhist monk, travelled from Kashmir to Kucha and there instructed Kumārajīva in the Vinayapiṭaka.

Karkoṭa Empire (625–885 CE) was a powerful Hindu empire, which originated in the region of Kashmir.[26] It was founded by Durlabhvardhana during the lifetime of Harsha. The dynasty marked the rise of Kashmir as a power in South Asia.[27] Avanti Varman ascended the throne of Kashmir on 855 CE, establishing the Utpala dynasty and ending the rule of Karkoṭa dynasty.[28]

According to tradition, Adi Shankara visited the pre-existing Sarvajñapīṭha (Sharada Peeth) in Kashmir in the late 8th century or early 9th century CE. The Madhaviya Shankaravijayam states this temple had four doors for scholars from the four cardinal directions. The southern door of Sarvajna Pitha was opened by Adi Shankara.[29] According to tradition, Adi Shankara opened the southern door by defeating in debate all the scholars there in all the various scholastic disciplines such as Mīmāṃsā, Vedanta and other branches of Hindu philosophy; he ascended the throne of Transcendent wisdom of that temple.[30]

Abhinavagupta (c. 950–1020 CE[31][32]) was one of India's greatest philosophers, mystics and aestheticians. He was also considered an important musician, poet, dramatist, exegete, theologian, and logician[33][34] – a polymathic personality who exercised strong influences on Indian culture.[35][36] He was born in the Kashmir Valley[37] in a family of scholars and mystics and studied all the schools of philosophy and art of his time under the guidance of as many as fifteen (or more) teachers and gurus.[38] In his long life he completed over 35 works, the largest and most famous of which is Tantrāloka, an encyclopaedic treatise on all the philosophical and practical aspects of Trika and Kaula (known today as Kashmir Shaivism). Another one of his very important contributions was in the field of philosophy of aesthetics with his famous Abhinavabhāratī commentary of Nāṭyaśāstra of Bharata Muni.[39]

In the 10th century Mokshopaya or Moksopaya Shastra, a philosophical text on salvation for non-ascetics (moksa-upaya: 'means to release'), was written on the Pradyumna hill in Srinagar.[40][41] It has the form of a public sermon and claims human authorship and contains about 30,000 shloka's (making it longer than the Ramayana). The main part of the text forms a dialogue between Vashistha and Rama, interchanged with numerous short stories and anecdotes to illustrate the content.[42][43] This text was later (11th to the 14th century CE)[44] expanded and vedanticised, which resulted in the Yoga Vasistha.[45]

Queen Kota Rani was medieval Hindu ruler of Kashmir, ruling until 1339. She was a notable ruler who is often credited for saving Srinagar city from frequent floods by getting a canal constructed, named after her "Kutte Kol". This canal receives water from Jhelum River at the entry point of city and again merges with Jhelum river beyond the city limits.[46]

Shah Mir Dynasty

Shams-ud-Din Shah Mir (reigned 1339–42) was the first Muslim ruler of Kashmir[47] and founder of the Shah Mir dynasty.[47][48] Kashmiri historian Jonaraja, in his Dvitīyā Rājataraṅginī mentioned Shah Mir was from the country of Panchagahvara (identified as the Panjgabbar valley between Rajouri and Budhal), and his ancestors were Kshatriya, who converted to Islam.[49][50] Scholar A. Q. Rafiqi states:

Shāh Mīr arrived in Kashmir in 1313, along with his family, during the reign of Sūhadeva (1301–20), whose service he entered. In subsequent years, through his tact and ability, Shāh Mīr rose to prominence and became one of the important personalities of the time. Later, after the death in 1338 of Udayanadeva, the brother of Sūhadeva, he was able to assume the kingship himself and thus laid the foundation of permanent Muslim rule in Kashmir. Dissensions among the ruling classes and foreign invasions were the two main factors which contributed towards the establishment of Muslim rule in Kashmir.[51]

Rinchan, from Ladakh, and Lankar Chak, from Dard territory near Gilgit, came to Kashmir and played a notable role in the subsequent political history of the Valley. All the three men were granted Jagirs (feudatory estates) by the King. Rinchan became the ruler of Kashmir for three years.

Shah Mir was the first ruler of the Shah Mir dynasty, which was established in 1339. Muslim ulama, such as Mir Sayyid Ali Hamadani, arrived from Central Asia to proselytize in Kashmir and their efforts converted thousands of Kashmiris to Islam[52] and Hamadani's son also convinced Sikander Butshikan to enforce Islamic law. By the late 1400s most Kashmiris had accepted Islam.[53] Persian was introduced in Kashmir by the Šāh-Miri dynasty (1349–1561) and started to flourish under Sultan Zayn-al-ʿĀbedin (1420–70).[54]

Mughal rule

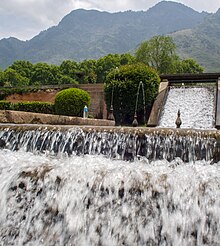

The Mughal padishah (emperor) Akbar conquered Kashmir from 1585–86, taking advantage of Kashmir's internal Sunni-Shia divisions,[55] and thus ended indigenous Kashmiri Muslim rule.[6] Akbar added it to the Kabul Subah (encompassing modern-day northeastern Afghanistan, northern Pakistan and the Kashmir Valley of India), but Shah Jahan carved it out as a separate subah (imperial top-level province) with its seat at Srinagar. Kashmir became the northern-most region of Mughal India as well as a pleasure ground in the summertime. They built Persian water-gardens in Srinagar, along the shores of Dal Lake, with cool and elegantly proportioned terraces, fountains, roses, jasmine and rows of chinar trees.[56]

Afghan rule

The Afghan Durrani dynasty's Durrani Empire controlled Kashmir from 1751, when 15th Mughal padshah (emperor) Ahmad Shah Bahadur's viceroy Muin-ul-Mulk was defeated and reinstated by the Durrani founder Ahmad Shah Durrani (who conquered, roughly, modern day Afghanistan and Pakistan from the Mughals and local rulers), until the 1820 Sikh triumph. The Afghan rulers brutally repressed Kashmiris of all faiths (according to Kashmiri historians).[57]

Sikh rule

In 1819, the Kashmir Valley passed from the control of the Durrani Empire of Afghanistan to the conquering armies of the Sikhs under Ranjit Singh of the Punjab,[58] thus ending four centuries of Muslim rule under the Mughals and the Afghan regime. As the Kashmiris had suffered under the Afghans, they initially welcomed the new Sikh rulers.[59] However, the Sikh governors turned out to be hard taskmasters, and Sikh rule was generally considered oppressive,[60] protected perhaps by the remoteness of Kashmir from the capital of the Sikh Empire in Lahore.[61] The Sikhs enacted a number of anti-Muslim laws,[61] which included handing out death sentences for cow slaughter,[59] closing down the Jamia Masjid in Srinagar,[61] and banning the adhan, the public Muslim call to prayer.[61] Kashmir had also now begun to attract European visitors, several of whom wrote of the abject poverty of the vast Muslim peasantry and of the exorbitant taxes under the Sikhs.[59][62] High taxes, according to some contemporary accounts, had depopulated large tracts of the countryside, allowing only one-sixteenth of the cultivable land to be cultivated.[59] Many Kashmiri peasants migrated to the plains of the Punjab.[63] However, after a famine in 1832, the Sikhs reduced the land tax to half the produce of the land and also began to offer interest-free loans to farmers;[61] Kashmir became the second highest revenue earner for the Sikh Empire.[61] During this time Kashmir shawls became known worldwide, attracting many buyers, especially in the West.[61]

The state of Jammu, which had been on the ascendant after the decline of the Mughal Empire, came under the sway of the Sikhs in 1770. Further in 1808, it was fully conquered by Maharaja Ranjit Singh. Gulab Singh, then a youngster in the House of Jammu, enrolled in the Sikh troops and, by distinguishing himself in campaigns, gradually rose in power and influence. In 1822, he was anointed as the Raja of Jammu.[64] Along with his able general Zorawar Singh Kahluria, he conquered and subdued Rajouri (1821), Kishtwar (1821), Suru valley and Kargil (1835), Ladakh (1834–1840), and Baltistan (1840), thereby surrounding the Kashmir Valley. He became a wealthy and influential noble in the Sikh court.[65]

Princely state

In 1845, the First Anglo-Sikh War broke out. According to The Imperial Gazetteer of India:

"Gulab Singh contrived to hold himself aloof till the battle of Sobraon (1846), when he appeared as a useful mediator and the trusted advisor of Sir Henry Lawrence. Two treaties were concluded. By the first the State of Lahore (i.e. West Punjab) handed over to the British, as equivalent for one crore indemnity, the hill countries between the rivers Beas and Indus; by the second the British made over to Gulab Singh for 75 lakhs all the hilly or mountainous country situated to the east of the Indus and the west of the Ravi i.e. the Vale of Kashmir)."[58]

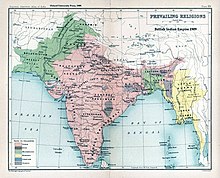

Drafted by a treaty and a bill of sale, and constituted between 1820 and 1858, the Princely State of Kashmir and Jammu (as it was first called) combined disparate regions, religions, and ethnicities:[66] to the east, Ladakh was ethnically and culturally Tibetan and its inhabitants practised Buddhism; to the south, Jammu had a mixed population of Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs; in the heavily populated central Kashmir valley, the population was overwhelmingly Sunni Muslim, however, there was also a small but influential Hindu minority, the Kashmiri brahmins or pandits; to the northeast, sparsely populated Baltistan had a population ethnically related to Ladakh, but which practised Shia Islam; to the north, also sparsely populated, Gilgit Agency, was an area of diverse, mostly Shiʻa groups; and, to the west, Punch was Muslim, but of different ethnicity than the Kashmir valley.[66] After the Indian Rebellion of 1857, in which Kashmir sided with the British, and the subsequent assumption of direct rule by Great Britain, the princely state of Kashmir came under the suzerainty of the British Crown.

In the British census of India of 1941, Kashmir registered a Muslim majority population of 77%, a Hindu population of 20% and a sparse population of Buddhists and Sikhs comprising the remaining 3%.[67] That same year, Prem Nath Bazaz, a Kashmiri Pandit journalist wrote: "The poverty of the Muslim masses is appalling. ... Most are landless laborers, working as serfs for absentee [Hindu] landlords ... Almost the whole brunt of official corruption is borne by the Muslim masses."[68] Under the Hindu rule, Muslims faced hefty taxation, discrimination in the legal system and were forced into labor without any wages.[69] Conditions in the princely state caused a significant migration of people from the Kashmir Valley to Punjab of British India.[70] For almost a century until the census, a small Hindu elite had ruled over a vast and impoverished Muslim peasantry.[67][71] Driven into docility by chronic indebtedness to landlords and moneylenders, having no education besides, nor awareness of rights,[67] the Muslim peasants had no political representation until the 1930s.[71]

1947 and 1948

Ranbir Singh's grandson Hari Singh, who had ascended the throne of Kashmir in 1925, was the reigning monarch in 1947 at the conclusion of British rule of the subcontinent and the subsequent partition of the British Indian Empire into the newly independent Dominion of India and the Dominion of Pakistan.

In the run up to 1947 partition, there were two major parties in the princely state: the National Conference and the Muslim Conference. The former was led by the charismatic Kashmiri leader Sheikh Abdullah, who tilted towards the accession of the state to India, whilst the latter tilted towards accession to Pakistan.[72] The National Conference enjoyed popular support in the Kashmir Valley whilst the Muslim Conference was more popular in the Jammu region.[73] The Hindus and Sikhs of the state were firmly in favour of joining India, as were the Buddhists.[74] However, the sentiments of the state's Muslim population were divided. Scholar Christopher Snedden states that the Muslims of Western Jammu, and also the Muslims of the Frontier Districts Province, strongly wanted Jammu and Kashmir to join Pakistan.[75] The ethnic Kashmiri Muslims of the Kashmir Valley, on the other hand, were ambivalent about Pakistan (possibly due to their secular nature).[76][77][78][79][80] The fact that Kashmiris were not particularly enamoured with the idea of Pakistan reflected the failure of the idea of Pan-Islamic identity in satisfying the political urges of Kashmiris.[81] At the same time there was also a lack of interest in merging with Indian nationalism.[82]

According to Burton Stein's History of India

Kashmir was neither as large nor as old an independent state as Hyderabad; it had been created rather off-handedly by the British after the first defeat of the Sikhs in 1846, as a reward to a former official who had sided with the British. The Himalayan kingdom was connected to India through a district of the Punjab, but its population was 77 per cent Muslim and it shared a boundary with Pakistan. Hence, it was anticipated that the maharaja would accede to Pakistan when the British paramountcy ended on 14–15 August. When he hesitated to do this, Pakistan launched a guerrilla onslaught meant to frighten its ruler into submission. Instead the Maharaja appealed to Mountbatten[83] for assistance, and the governor-general agreed on the condition that the ruler accede to India. Indian soldiers entered Kashmir and drove the Pakistani-sponsored irregulars from all but a small section of the state. The United Nations was then invited to mediate the quarrel. The UN mission insisted that the opinion of Kashmiris must be ascertained, while India insisted that no referendum could occur until all of the state had been cleared of irregulars.[84]

In the last days of 1948, a ceasefire was agreed under UN auspices. However, since the referendum demanded by the UN was never conducted, relations between India and Pakistan soured,[84] and eventually led to two more wars over Kashmir in 1965 and 1999.

Current status and political divisions

India has control of about half the area of the former princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, which comprises the union territories of Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh, while Pakistan controls a third of the region, divided into two de facto provinces, Gilgit-Baltistan and Azad Kashmir.

"Although there was a clear Muslim majority in Kashmir before the 1947 partition and its economic, cultural, and geographic contiguity with the Muslim-majority area of the Punjab (in Pakistan) could be convincingly demonstrated, the political developments during and after the partition resulted in a division of the region. Pakistan was left with territory that, although basically Muslim in character, was thinly populated, relatively inaccessible, and economically underdeveloped. The largest Muslim group, situated in the Valley of Kashmir and estimated to number more than half the population of the entire region, lay in Indian-administered territory, with its former outlets via the Jhelum valley route blocked."[85][1]

The eastern region of the former princely state of Kashmir is also involved in a boundary dispute that began in the late 19th century and continues into the 21st. Although some boundary agreements were signed between Great Britain, Afghanistan and Russia over the northern borders of Kashmir, China never accepted these agreements, and China's official position has not changed following the communist revolution of 1949 that established the People's Republic of China. By the mid-1950s the Chinese army had entered the north-east portion of Ladakh.[85]

By 1956–57 they had completed a military road through the Aksai Chin area to provide better communication between Xinjiang and western Tibet. India's belated discovery of this road led to border clashes between the two countries that culminated in the Sino-Indian War of October 1962.[85]

The region is divided amongst three countries in a territorial dispute: Pakistan controls the northwest portion (Northern Areas and Kashmir), India controls the central and southern portion (Jammu and Kashmir) and Ladakh, and the People's Republic of China controls the northeastern portion (Aksai Chin and the Trans-Karakoram Tract). India controls the majority of the Siachen Glacier area, including the Saltoro Ridge passes, whilst Pakistan controls the lower territory just southwest of the Saltoro Ridge. India controls 101,338 km2 (39,127 sq mi) of the disputed territory, Pakistan controls 85,846 km2 (33,145 sq mi), and the People's Republic of China controls the remaining 37,555 km2 (14,500 sq mi).

Jammu and Azad Kashmir lie outside Pir Panjal range,[clarification needed] and are under Indian and Pakistani control respectively. These are populous regions. Gilgit–Baltistan, formerly known as the Northern Areas, is a group of territories in the extreme north, bordered by the Karakoram, the western Himalayas, the Pamir, and the Hindu Kush ranges. With its administrative centre in the town of Gilgit, the Northern Areas cover an area of 72,971 square kilometres (28,174 sq mi) and have an estimated population approaching 1 million (10 lakhs).

Ladakh is a region in the east, between the Kunlun mountain range in the north and the main Great Himalayas to the south.[86] Main cities are Leh and Kargil. It is under Indian administration and is part of the state of Jammu and Kashmir. It is one of the most sparsely populated regions in the area and is mainly inhabited by people of Indo-Aryan and Tibetan descent.[86] Aksai Chin is a vast high-altitude desert of salt that reaches altitudes up to 5,000 metres (16,000 ft). Geographically part of the Tibetan Plateau, Aksai Chin is referred to as the Soda Plain. The region is almost uninhabited, and has no permanent settlements.

Though these regions are in practice administered by their respective claimants, neither India nor Pakistan has formally recognised the accession of the areas claimed by the other. India claims those areas, including the area "ceded" to China by Pakistan in the Trans-Karakoram Tract in 1963, are a part of its territory, while Pakistan claims the entire region excluding Aksai Chin and Trans-Karakoram Tract. The two countries have fought several declared wars over the territory. The Indo-Pakistani War of 1947 established the rough boundaries of today, with Pakistan holding roughly one-third of Kashmir, and India one-half, with a dividing line of control established by the United Nations. The Indo-Pakistani War of 1965 resulted in a stalemate and a UN-negotiated ceasefire.

Demographics

In the 1901 Census of the British Indian Empire, the population of the princely state of Kashmir and Jammu was 2,905,578. Of these, 2,154,695 (74.16%) were Muslims, 689,073 (23.72%) Hindus, 25,828 (0.89%) Sikhs, and 35,047 (1.21%) Buddhists (implying 935 (0.032%) others).

The Hindus were found mainly in Jammu, where they constituted a little less than 60% of the population.[87] In the Kashmir Valley, the Hindus represented "524 in every 10,000 of the population (i.e. 5.24%), and in the frontier wazarats of Ladhakh and Gilgit only 94 out of every 10,000 persons (0.94%)."[87] In the same Census of 1901, in the Kashmir Valley, the total population was recorded to be 1,157,394, of which the Muslim population was 1,083,766, or 93.6% and the Hindu population 60,641.[87] Among the Hindus of Jammu province, who numbered 626,177 (or 90.87% of the Hindu population of the princely state), the most important castes recorded in the census were "Brahmans (186,000), the Rajputs (167,000), the Khattris (48,000) and the Thakkars (93,000)."[87]

In the 1911 Census of the British Indian Empire, the total population of Kashmir and Jammu had increased to 3,158,126. Of these, 2,398,320 (75.94%) were Muslims, 696,830 (22.06%) Hindus, 31,658 (1%) Sikhs, and 36,512 (1.16%) Buddhists. In the last census of British India in 1941, the total population of Kashmir and Jammu (which as a result of the second world war, was estimated from the 1931 census) was 3,945,000. Of these, the total Muslim population was 2,997,000 (75.97%), the Hindu population was 808,000 (20.48%), and the Sikh 55,000 (1.39%).[88]

The Kashmiri Pandits, the only Hindus of the Kashmir valley, who had stably constituted approximately 4 to 5% of the population of the valley during Dogra rule (1846–1947), and 20% of whom had left the Kashmir valley by 1950,[89] began to leave in much greater numbers in the 1990s. According to a number of authors, approximately 100,000 of the total Kashmiri Pandit population of 140,000 left the valley during that decade.[90] Other authors have suggested a higher figure for the exodus, ranging from the entire population of over 150[91] to 190 thousand (1.5 to 190,000) of a total Pandit population of 200 thousand (200,000)[92] to a number as high as 300 thousand[93] (300,000).

People in Jammu speak Hindi, Punjabi and Dogri, the Vale of Kashmir speaks Kashmiri and the sparsely inhabited Ladakh region speaks Tibetan and Balti.[1]

The total population of India's division of Jammu and Kashmir is 12,541,302[94] and Pakistan's division of Kashmir is 2,580,000 and Gilgit-Baltistan is 870,347.[95]

| Administered by | Area | Population | % Muslim | % Hindu | % Buddhist | % Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kashmir Valley | ~4 million (4 million) | 95% | 4%* | – | – | |

| Jammu | ~3 million (3 million) | 30% | 66% | – | 4% | |

| Ladakh | ~0.25 million (250,000) | 46% | 12% | 40% | 2% | |

| Azad Kashmir | ~4 million (4 million) | 100% | – | – | – | |

| Gilgit–Baltistan | ~2 million (2 million) | 99% | – | – | – | |

| Aksai Chin | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Trans-Karakoram | – | – | – | – | – | |

-

A Muslim shawl-making family shown in Cashmere shawl manufactory, 1867, chromolithograph, William Simpson.

-

A group of Pundits, or Brahmin priests, in Kashmir, photographed by an unknown photographer in the 1890s.

Economy

Kashmir's economy is centred around agriculture. Traditionally the staple crop of the valley was rice, which formed the chief food of the people. In addition, Indian corn, wheat, barley and oats were also grown. Given its temperate climate, it is suited for crops like asparagus, artichoke, seakale, broad beans, scarletrunners, beetroot, cauliflower and cabbage. Fruit trees are common in the valley, and the cultivated orchards yield pears, apples, peaches, and cherries. The chief trees are deodar, firs and pines, chenar or plane, maple, birch and walnut, apple, cherry.

Historically, Kashmir became known worldwide when Cashmere wool was exported to other regions and nations (exports have ceased due to decreased abundance of the cashmere goat and increased competition from China). Kashmiris are well adept at knitting and making Pashmina shawls, silk carpets, rugs, kurtas, and pottery. Saffron, too, is grown in Kashmir. Srinagar is known for its silver-work, papier-mâché, wood-carving, and the weaving of silk. The economy was badly damaged by the 2005 Kashmir earthquake which, as of 8 October 2005, resulted in over 70,000 deaths in the Pakistan-controlled part of Kashmir and around 1,500 deaths in Indian-controlled Kashmir.

Transport

Transport is predominantly by air or road vehicles in the region.[96] Kashmir has a 135 km (84 mi) long modern railway line that started in October 2009, and was last extended in 2013 and connects Baramulla, in the western part of Kashmir, to Srinagar and Banihal. It is expected to link Kashmir to the rest of India after the construction of the railway line from Katra to Banihal is completed.[97]

See also

- 1941 Census of Jammu and Kashmir

- Cashmere (disambiguation)

- Human rights abuses in Kashmir

- Kashmiris

- Line of Control

- List of Jammu and Kashmir-related articles

- List of Kashmiri people

- Theory of Kashmiri descent from lost tribes of Israel

Notes

- ^ a b c d "Kashmir: region, Indian subcontinent". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 16 July 2016. Quote: "Kashmir, region of the northwestern Indian subcontinent. It is bounded by the Uygur Autonomous Region of Xinjiang to the northeast and the Tibet Autonomous Region to the east (both parts of China), by the Indian states of Himachal Pradesh and Punjab to the south, by Pakistan to the west, and by Afghanistan to the northwest. The northern and western portions are administered by Pakistan and comprise three areas: Azad Kashmir, Gilgit, and Baltistan, ... The southern and southeastern portions constitute the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir. The Indian- and Pakistani-administered portions are divided by a “line of control” agreed to in 1972, although neither country recognizes it as an international boundary. In addition, China became active in the eastern area of Kashmir in the 1950s and since 1962 has controlled the northeastern part of Ladakh (the easternmost portion of the region)."

- ^ a b "Kashmir territories profile". BBC. Retrieved 16 July 2016. Quote: "The Himalayan region of Kashmir has been a flashpoint between India and Pakistan for over six decades. Since India's partition and the creation of Pakistan in 1947, the nuclear-armed neighbours have fought three wars over the Muslim-majority territory, which both claim in full but control in part. Today it remains one of the most militarised zones in the world. China administers parts of the territory."

- ^ "Kashmir profile—timeline". BBC News. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

1950s—China gradually occupies eastern Kashmir (Aksai Chin).

1962—China defeats India in a short war for control of Aksai Chin.

1963—Pakistan cedes the Trans-Karakoram Tract of Kashmir to China. - ^ Basham, A. L. (2005) The wonder that was India, Picador. Pp. 572. ISBN 0-330-43909-X, p. 110.

- ^ a b c Imperial Gazetteer of India, volume 15. 1908. Oxford University Press, Oxford and London. pp. 93–95.

- ^ a b Puri, Balraj (June 2009), "5000 Years of Kashmir", Epilogue, vol. 3, no. 6, pp. 43–45, retrieved 31 December 2016,

It was emperor Akbar who brought an end to indigenous Kashmiri Muslim rule that had lasted 250 years. The watershed in Kashmiri history is not the beginning of the Muslim rule as is regarded in the rest of the subcontinent but the changeover from Kashmiri rule to a non-Kashmiri rule.

- ^ "A Comparative Dictionary of the Indo-Aryan Languages". Dsalsrv02.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ^ Akbar, M. J. (1991), Kashmir, behind the vale, Viking, p. 9

- ^ Raina, Mohini Qasba (October 2013), Kashur The Kashmiri Speaking People, Trafford Publishing, pp. 3–, ISBN 978-1-4907-0165-3

- ^ a b Snedden, Christopher (2015), Understanding Kashmir and Kashmiris, Oxford University Press, pp. 22–, ISBN 978-1-84904-342-7

- ^ Raina, Mohini Qasba (2013). Kashur The Kashmiri Speaking People. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4907-0165-3.

- ^ Bamzai, P. N. K. (1994). Culture and Political History of Kashmir. M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 978-81-85880-31-0.

- ^ Khan, Ruhail (6 July 2017). Who Killed Kasheer?. Notion Press. ISBN 9781947283107.

- ^ Kumāra, Braja Bihārī (2007). India and Central Asia: Classical to Contemporary Periods. Concept Publishing Company. p. 64. ISBN 9788180694578.

- ^ a b Raina, Mohini Qasba (13 November 2014). Kashur The Kashmiri Speaking People. Partridge Publishing Singapore. p. 11. ISBN 9781482899450.

- ^ Kaw, M. K. (2004). Kashmir and Its People: Studies in the Evolution of Kashmiri Society. APH Publishing. ISBN 9788176485371.

- ^ Toshakhānī, Śaśiśekhara; Warikoo, Kulbhushan (2009). Cultural Heritage of Kashmiri Pandits. Pentagon Press. pp. 2–3. ISBN 9788182743984.

- ^ P. iv 'Kashmir Today' by Government, 1998

- ^ Snedden, Christopher (2013). Kashmir: The Unwritten History. HarperCollins India. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-9350298985.

- ^ The enigma of terminology Archived 16 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine, The Hindu, 27 January 2014.

- ^ Zain, Ali (13 September 2015). "Pakistani flag hoisted, pro-freedom slogans chanted in Indian Occupied Kashmir – Daily Pakistan Global". En.dailypakistan.com.pk. Archived from the original on 18 November 2015. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- ^ "Pakistani flag hoisted once again in Indian Occupied Kashmir". Dunya News. 11 September 2015. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- ^ South Asia: fourth report of session 2006–07 by By Great Britain: Parliament: House of Commons: Foreign Affairs Committee page 37

- ^ A.K. Warder, Indian Buddhism. Motilal Banarsidass 2000, page 256.

- ^ A.K. Warder, Indian Buddhism. Motilal Banarsidass 2000, pages 263–264.

- ^ Ram, P. (1 December 2014). Life in India, Issue 1.[dead link]

- ^ Kalhana (1147–1149); Rajatarangini.

- ^ Sen, Sailendra Nath (1999). Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International. p. 295. ISBN 978-8122-411-98-0.

- ^ Shyama Kumar Chattopadhyaya (2000) The Philosophy of Sankar's Advaita Vedanta, Sarup & Sons, New Delhi ISBN 81-7625-222-0, ISBN 978-81-7625-222-5

- ^ Tapasyananda, Swami (2002), Sankara-Dig-Vijaya, pp. 186–195

- ^ Triadic Heart of Shiva, Paul E. Muller-Ortega, page 12

- ^ Introduction to the Tantrāloka, Navjivan Rastogi, page 27

- ^ Key to the Vedas, Nathalia Mikhailova, page 169

- ^ The Pratyabhijñā Philosophy, Ganesh Vasudeo Tagare, page 12

- ^ Companion to Tantra, S.C. Banerji, page 89

- ^ Doctrine of Divine Recognition, K. C. Pandey, page V

- ^ Introduction to the Tantrāloka, Navjivan Rastogi, page 35

- ^ Luce dei Tantra, Tantrāloka, Abhinavagupta, Raniero Gnoli, page LXXVII

- ^ Slaje, Walter. (2005). "Locating the Mokṣopāya", in: Hanneder, Jürgen (Ed.). The Mokṣopāya, Yogavāsiṣṭha and Related Texts Aachen: Shaker Verlag. (Indologica Halensis. Geisteskultur Indiens. 7). p. 35.

- ^ "Gallery – The journey to the Pradyumnaśikhara". Archived from the original on 23 December 2005.

- ^ Leslie 2003, pp. 104–107

- ^ Lekh Raj Manjdadria. (2002?) The State of Research to date on the Yogavastha (Moksopaya) Archived 15 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Hanneder, Jürgen; Slaje, Walter. Moksopaya Project: Introduction. Archived 28 December 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Chapple, Christopher; Venkatesananda (1984), "Introduction", The Concise Yoga Vāsiṣṭha, Albany: State University of New York Press, pp. x–xi, ISBN 978-0-87395-955-1, OCLC 11044869

- ^ Culture and political history of Kashmir, Prithivi Nath Kaul Bamzai, M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd., 1994.

- ^ a b Concise Encyclopeida Of World History By Carlos Ramirez-Faria, page 412

- ^ The Pearson Indian History Manual for the UPSC Civil Services Page 104 "However, the situation changed with the ending of the Hindu rule and founding of the Shahmiri dynasty by Shahmir or Dhams-ud-din (1339–1342). The devastating attack on Kashmir in 1320 by the Mongol leader, Dalucha, was a prelude to it. It is said ... The Sultan was himself a learned man, and composed poetry. He was ..."

- ^

Sharma, R. S. (1992), A Comprehensive History of India, Orient Longmans, p. 628, ISBN 978-81-7007-121-1,

Jonaraja records two events of Suhadeva's reign (1301-20), which were of far-reaching importance and virtually changed the course of the history of Kashmir. The first was the arrival of Shah Mir in 1313. He was a Muslim condottiere from the border of Panchagahvara, an area situated to the south of the Divasar pargana in the valley of river Ans, a tributary of the Chenab.

- ^ Zutshi, N. K. (1976), Sultan Zain-ul-Abidin of Kashmir: an age of enlightenment, Nupur Prakashan, pp. 6–7

- ^ Baloch, N. A.; Rafiqi, A. Q. (1998), "The Regions of Sind, Baluchistan, Multan and Kashmir" (PDF), in M. S. Asimov; C. E. Bosworth (eds.), History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Vol. IV, Part 1—The age of achievement: A.D. 750 to the end of the fifteenth century—The historical, social and economic setting, UNESCO, pp. 297–322, ISBN 978-92-3-103467-1

- ^ Amin, Tahir; Schofield, Victoria. "Kashmir". The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World.

A large number of Muslim ʿulamāʿ came from Central Asia to Kashmir to preach; Sayyid Bilāl Shāh, Sayyid Jalāluddīn of Bukhara, Sayyid Tajuddīn, his brother Sayyid Ḥusayn Sīmānī, Sayyid ʿAlī Ḥamadānī, his son Mir Muḥammad Hamadānī, and Shaykh Nūruddīn are some of the well-known ʿulamāʿ who played a significant role in spreading Islam.

- ^ Amin, Tahir; Schofield, Victoria. "Kashmir". The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World.

The contribution of Sayyid ʿAlī Hamadānī, popularly known as Shah-yi Hamadān, is legendary. Born at Hamadān (Iran) in 1314 and belonging to the Kubrawīyah order of Ṣūfīs, a branch of the Suhrawardīyah, he paid three visits to Kashmir in 1372, 1379, and 1383; together with several hundred followers, he converted thousands of Kashmiris to Islam. His son Sayyid Muḥammad Hamadānī continued his work, vigorously propagating Islam as well as influencing the Muslim ruler Sikander (1389–1413) to enforce Islamic law and to establish the office of the Shaykh al-Islām (chief religious authority). By the end of the fifteenth century, the majority of the people had embraced Islam.

- ^ "Kashmir". Encyclopedia Iranica. 2012.

- ^ Snedden, Christopher (2015). Understanding Kashmir and Kashmiris. Oxford University Press. p. 29. ISBN 9781849043427.

Similarly, Sunni and Shia Kashmiris had troubles at times, with their differences offering the third Mughal Emperor, Akbar (ruled 1556–1605), a pretext to invade Kashmir, and capture it, in 1586.

- ^ Hilton, Isabel (2002). "Between the Mountains". The New Yorker.

- ^ Zutshi, Chitralekha (2004). Languages of Belonging: Islam, Regional Identity, and the Making of Kashmir. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 35. ISBN 9781850657002.

Most historians of Kashmir agree on the rapacity of the Afghan governors, a period unrelieved by even brief respite devoted to good work and welfare for the people of Kashmir. According to these histories, the Afghans were brutally repressive with all Kashmiris, regardless of class or religion

- ^ a b Imperial Gazetteer of India, volume 15. 1908. "Kashmir: History". pp. 94–95.

- ^ a b c d Schofield, Kashmir in Conflict 2003, pp. 5–6

- ^ Madan, Kashmir, Kashmiris, Kashimiriyat 2008, p. 15

- ^ a b c d e f g Zutshi, Languages of Belonging 2004, pp. 39–41

- ^ Amin, Tahir; Schofield, Victoria. "Kashmir". The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World.

During both Sikh and Dogra rule, heavy taxation, forced work without wages (begār), discriminatory laws, and rural indebtedness were widespread among the largely illiterate Muslim population.

- ^ Zutshi, Chitralekha (2004). Languages of Belonging: Islam, Regional Identity, and the Making of Kashmir. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 40. ISBN 9781850656944.

Kashmiri histories emphasize the wretchedness of life for the common Kashmiri during Sikh rule. According to these, the peasantry became mired in poverty and migrations of Kashmiri peasants to the plains of the Punjab reached high proportions. Several European travelers' accounts from the period testify to and provide evidence for such assertions.

- ^ Panikkar 1930, p. 10–11, 14–34.

- ^ Schofield, Kashmir in Conflict 2003, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b Bowers, Paul. 2004. "Kashmir." Research Paper 4/28 Archived 26 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine, International Affairs and Defence, House of Commons Library, United Kingdom.

- ^ a b c Bose, Roots of Conflict, Paths to Peace 2003, pp. 15–17

- ^ Quoted in Bose, Roots of Conflict, Paths to Peace 2003, pp. 15–17

- ^ Amin, Tahir; Schofield, Victoria (2009), "Kashmir", The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World, retrieved 19 June 2018

- ^ Sumantra Bose (2013). Transforming India. Harvard University Press. p. 211. ISBN 978-0-674-72820-2.

- ^ a b Talbot & Singh 2009, p. 54

- ^ Snedden, Christopher (2013). Kashmir-The Untold Story. HarperCollins Publishers India. p. 22. ISBN 9789350298985.

In 1947, J&K's political scene was dominated by two parties: the All J&K National Conference (commonly called the National Conference) and the All J&K Muslim Conference (commonly called the Muslim Conference). Each conference had a different aspiration for J&K's status: the National Conference opposed J&K joining Pakistan; the Muslim Conference favoured this option.

- ^ Snedden, Christopher (2013). Kashmir-The Untold Story. HarperCollins Publishers India. ISBN 9789350298985.

The National Conference was strongest in the Kashmir Valley... conversely, outside the Kashmir Valley its support was much less, with perhaps five to 15 per cent of the population supporting it. The Muslim Conference had a lot of support in Jammu Province and much less in the Kashmir Valley.

- ^ Snedden, Christopher (2012). The Untold Story of the People of Azad Kashmir. Hurst. p. 35. ISBN 9781849041508. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

Those Hindus and Sikhs who comprised a majority in the eastern parts of Jammu province were strongly pro-Indian. Their dislike of Pakistan and pro-Pakistani J&K Muslims was further heightened by the arrival of angry and agitated Hindu and Sikh refugees from western (Pakistani) Punjab after 15 August 1947. Accession to Pakistan therefore, would almost certainly have seen these people either fight to retain their land or take flight to India. In the event of accession to Pakistan, Hindu Pandits and Sikhs in the Kashmir Valley, most of whom probably favoured J&K joining India, might also have fled to pro-Indian parts of J&K, or to India. Although their position is less clear, Ladakhi Buddhists probably favoured India also.

- ^ Snedden, Christopher (2013). Kashmir-The Untold Story. HarperCollins Publishers India. ISBN 9789350298985.

Similarly, Muslims in Western Jammu Province, particularly in Poonch, many of whom had martial capabilities, and Muslims in the Frontier Districts Province strongly wanted J&K to join Pakistan.

- ^ Snedden, Christopher (2013). Kashmir-The Untold Story. HarperCollins Publishers India. ISBN 9789350298985.

An important trait evident among Kashmiris partially explains why Kashmiri Muslims were ambivalent about Pakistan in 1947.

- ^ Snedden, Christopher (2013). Kashmir-The Untold Story. HarperCollins Publishers India. ISBN 9789350298985.

One significant result of the concept of Kashmiriness was that Kashmiris may have been naturally attracted to secular thinking.

- ^ Snedden, Christopher (2012). The Untold Story of the People of Azad Kashmir. Hurst. p. 24. ISBN 9781849041508. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

The CMG, the best-informed English-language newspaper on J&K affairs, on 21 October 1947 reported that the southern Kashmir Valley, which apparently was the 'stronghold' of the Kisan Mazdoor Conference, 'last week witnessed a massive upsurge in favour of Pakistan'. However, the CMG's report predated the tribal invasion of Kashmir Province by one day, after which support for pro-Pakistan parties may have lessened, at least in the short term, even though southern Kashmir was not directly affected by this invasion.

- ^ D. A. Low (18 June 1991). Political Inheritance of Pakistan. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 237–. ISBN 978-1-349-11556-3.

- ^ Snedden, Christopher (2012). The Untold Story of the People of Azad Kashmir. Hurst. p. 24. ISBN 9781849041508. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

According to The Times' Special Correspondent in late October 1947, it was 'a moot point how far Abdullah's influence extends among the Kashmiri Muslims...but in Srinagar his influence is paramount'.

- ^ Chowdhary, Rekha (2015). Jammu and Kashmir: Politics of Identity and Separatism. Routledge. ISBN 9781317414049.

That is why, Kashmiris were not particularly enamoured with the idea of Pakistan. The developments of 1930s (when Muslim Conference was converted into the National Conference) and 1940s (when Kashmiri leadership took a deliberated decision to demand self-government) clearly reflected the failure of pan-Islamic identity satisfying the political urges of Kashmiris.

- ^ Chowdhary, Rekha (2015). Jammu and Kashmir: Politics of Identity and Separatism. Routledge. p. 20. ISBN 9781317414056.

However, even while rejecting Pakistan, Sheikh did not agree to accept union with India in an unconditional manner. He was very firm about protecting the rights and identity of Kashmiris. As Puri argues, it was the same reason that compelled the Kashmiri leaders to distance themselves from the Muslim politics of pre-partition India, which reflected a lack of urge to merge with Indian nationalism.

- ^ Viscount Louis Mountbatten, the last Viceroy of British India, stayed on in independent India from 1947 to 1948, serving as the first Governor-General of the Union of India.

- ^ a b Stein, Burton. 2010. A History of India. Oxford University Press. 432 pages. ISBN 978-1-4051-9509-6. Page 358.

- ^ a b c Kashmir. (2007). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 27 March 2007, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Archived 13 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Jina, Prem Singh (1996), Ladakh: The Land and the People, Indus Publishing, ISBN 978-81-7387-057-6

- ^ a b c d Imperial Gazetteer of India, volume 15. 1908. Oxford University Press, Oxford and London. pp. 99–102.

- ^ Brush, J. E. (1949). "The Distribution of Religious Communities in India". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 39 (2): 81–98. doi:10.1080/00045604909351998.

- ^ Zutshi 2003, p. 318 Quote: "Since a majority of the landlords were Hindu, the (land) reforms (of 1950) led to a mass exodus of Hindus from the state. ... The unsettled nature of Kashmir's accession to India, coupled with the threat of economic and social decline in the face of the land reforms, led to increasing insecurity among the Hindus in Jammu, and among Kashmiri Pandits, 20 per cent of whom had emigrated from the Valley by 1950."

- ^ Bose 1997, p. 71, Rai 2004, p. 286, Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, p. 274 Quote: "The Hindu Pandits, a small but influential elite community who had secured a favourable position, first under the maharajas, and then under the successive Congress regimes, and proponents of a distinctive Kashmiri culture that linked them to India, felt under siege as the uprising gathered force. Of a population of some 140,000, perhaps 100,000 Pandits fled the state after 1990; their cause was quickly taken up by the Hindu right."

- ^ Malik 2005, p. 318

- ^ Madan 2008, p. 25

- ^ "South Asia :: India — The World Factbook - Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov.

- ^ "India, Jammu and Kashmir population statistics". GeoHive. Archived from the original on 19 April 2015. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ^ "Pakistan population statistics". GeoHive. Archived from the original on 6 April 2013. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ^ "Local Transport in Kashmir – Means of Transportation Kashmir – Mode of Transportation Kashmir India". Bharatonline.com. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ "How to Reach Kashmir by Train, Air, Bus?". Baapar.com. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

Bibliography

General history

- Bose, Sugata; Jalal, Ayesha (2003), Modern South Asia: History, Culture, Political Economy, London and New York: Routledge, 2nd edition. Pp. xiii, 304, ISBN 978-0-415-30787-1.

- Brown, Judith M. (1994), Modern India: The Origins of an Asian Democracy, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. Pp. xiii, 474, ISBN 978-0-19-873113-9.

- Copland, Ian (2002), The Princes of India in the Endgame of Empire, 1917–1947, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-89436-4

- Khan, Yasmin (2007), The Great Partition: The Making of India and Pakistan, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 250 pages, ISBN 978-0-300-12078-3

- Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (2004), A History of India, 4th edition. Routledge, Pp. xii, 448, ISBN 978-0-415-32920-0.

- Metcalf, Barbara; Metcalf, Thomas R. (2006), A Concise History of Modern India (Cambridge Concise Histories), Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. Pp. xxxiii, 372, ISBN 978-0-521-68225-1.

- Ramusack, Barbara (2004), The Indian Princes and their States (The New Cambridge History of India), Cambridge and London: Cambridge University Press. Pp. 324, ISBN 978-0-521-03989-5

- Stein, Burton (2001), A History of India, New Delhi and Oxford: Oxford University Press. Pp. xiv, 432, ISBN 978-0-19-565446-2.

- Talbot, Ian; Singh, Gurharpal (2009), The Partition of India, Cambridge University Press. Pp. xviii, 206, ISBN 978-0-521-76177-2

- Wolpert, Stanley (2006), Shameful Flight: The Last Years of the British Empire in India, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. Pp. 272, ISBN 978-0-19-515198-5.

Kashmir history

- Bose, Sumantra (1997), The Challenge in Kashmir: Democracy, Self-Determination and a Just Peace, SAGE Publications, ISBN 978-0-8039-9350-1

- Bose, Sumantra (2003), Kashmir: Roots of Conflict, Paths to Peace, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-01173-1

- Keenan, Brigid (2013), Travels in Kashmir, Hachette India, ISBN 978-93-5009-729-8

- Korbel, Josef (1966) [first published 1954], Danger in Kashmir (second ed.), Princeton University Press, ISBN 9781400875238

- Lamb, Alastair (1991) [first published 1991 by Roxford Books], Kashmir: A Disputed Legacy, 1846–1990, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-577423-8

- Lamb, Alastair (2002) [first published 1997 by Roxford Books], Incomplete Partition: The Genesis of the Kashmir Dispute, 1947–1948, Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Malik, Iffat (2005), Kashmir: Ethnic Conflict, International Dispute, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-579622-3

- Panikkar, K. M. (1930), Gulab Singh, London: Martin Hopkinson Ltd

- Rai, Mridu (2004), Hindu Rulers, Muslim Subjects: Islam, Rights, and the History of Kashmir, C. Hurst & Co, ISBN 978-1850656616

- Rao, Aparna, ed. (2008), The Valley of Kashmir: The Making and Unmaking of a Composite Culture?, Manohar Publishers & Distributors, ISBN 978-81-7304-751-0

- Evans, Alexander (2008), "Kashmiri Exceptionalism", in Rao, Aparna (ed.), The Valley of Kashmir: The Making and Unmaking of a Composite Culture?, pp. 713–741

- Kaw, Mushtaq A. (2008), "Land Rights in Rural Kashmir: A Study in Continuity and Change from Late-Sixteenth to Late-Twentieth Centuries", in Rao, Aparna (ed.), The Valley of Kashmir: The Making and Unmaking of a Composite Culture?, pp. 207–234

- Khan, Mohammad Ishaq (2008), "Islam, State and Society in Medieval Kashmir: A Revaluation of Mir Sayyid Ali Hamadani's Historical Role", in Rao, Aparna (ed.), The Valley of Kashmir: The Making and Unmaking of a Composite Culture?, pp. 97–198

- Madan, T. N. (2008), "Kashmir, Kashmiris, Kashmiriyat: An Introductory Essay", in Rao, Aparna (ed.), The Valley of Kashmir: The Making and Unmaking of a Composite Culture?, pp. 1–36

- Reynolds, Nathalène (2008), "Revisiting Key Episodes in Modern Kashmir History", in Rao, Aparna (ed.), The Valley of Kashmir: The Making and Unmaking of a Composite Culture?, pp. 563–604

- Witzel, Michael (2008), "The Kashmiri Pandits: Their Early History", in Rao, Aparna (ed.), The Valley of Kashmir: The Making and Unmaking of a Composite Culture?, pp. 37–96

- Zutshi, Chitraleka (2008), "Shrines, Political Authority, and Religious Identities in Late-Nineteenth and Early-Twentieth-century Kashmir", in Rao, Aparna (ed.), The Valley of Kashmir: The Making and Unmaking of a Composite Culture?, pp. 235–258

- Schaffer, Howard B. (2009), The Limits of Influence: America's Role in Kashmir, Brookings Institution Press, ISBN 978-0-8157-0370-9

- Schofield, Victoria (2003) [First published in 2000], Kashmir in Conflict, London and New York: I. B. Taurus & Co, ISBN 978-1860648984

- Singh, Bawa Satinder (1971), "Raja Gulab Singh's Role in the First Anglo-Sikh War", Modern Asian Studies, 5 (1): 35–59, doi:10.1017/s0026749x00002845, JSTOR 311654

- Zutshi, Chitralekha (2004), Languages of Belonging: Islam, Regional Identity, and the Making of Kashmir, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, ISBN 978-1-85065-700-2

Historical sources

- Blank, Jonah. "Kashmir–Fundamentalism Takes Root", Foreign Affairs, 78.6 (November/December 1999): 36–42.

- Drew, Federic. 1877. The Northern Barrier of India: a popular account of the Jammoo and Kashmir Territories with Illustrations; 1st edition: Edward Stanford, London. Reprint: Light & Life Publishers, Jammu. 1971.

- Evans, Alexander. Why Peace Won't Come to Kashmir, Current History (Vol 100, No 645) April 2001 p. 170–175.

- Hussain, Ijaz. 1998. "Kashmir Dispute: An International Law Perspective", National Institute of Pakistan Studies.

- Irfani, Suroosh, ed "Fifty Years of the Kashmir Dispute": Based on the proceedings of the International Seminar held at Muzaffarabad, Azad Jammu and Kashmir 24–25 August 1997: University of Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Muzaffarabad, AJK, 1997.

- Joshi, Manoj Lost Rebellion: Kashmir in the Nineties (Penguin, New Delhi, 1999).

- Khan, L. Ali The Kashmir Dispute: A Plan for Regional Cooperation 31 Columbia Journal of Transnational Law, 31, p. 495 (1994).

- Knight, E. F. 1893. Where Three Empires Meet: A Narrative of Recent Travel in: Kashmir, Western Tibet, Gilgit, and the adjoining countries. Longmans, Green, and Co., London. Reprint: Ch'eng Wen Publishing Company, Taipei. 1971.

- Knight, William, Henry. 1863. Diary of a Pedestrian in Cashmere and Thibet. Richard Bentley, London. Reprint 1998: Asian Educational Services, New Delhi.

- Köchler, Hans. The Kashmir Problem between Law and Realpolitik. Reflections on a Negotiated Settlement. Keynote speech delivered at the "Global Discourse on Kashmir 2008." European Parliament, Brussels, 1 April 2008.

- Moorcroft, William and Trebeck, George. 1841. Travels in the Himalayan Provinces of Hindustan and the Panjab; in Ladakh and Kashmir, in Peshawar, Kabul, Kunduz, and Bokhara... from 1819 to 1825, Vol. II. Reprint: New Delhi, Sagar Publications, 1971.

- Neve, Arthur. (Date unknown). The Tourist's Guide to Kashmir, Ladakh, Skardo &c. 18th Edition. Civil and Military Gazette, Ltd., Lahore. (The date of this edition is unknown – but the 16th edition was published in 1938).

- Stein, M. Aurel. 1900. Kalhaṇa's Rājataraṅgiṇī–A Chronicle of the Kings of Kaśmīr, 2 vols. London, A. Constable & Co. Ltd. 1900. Reprint, Delhi, Motilal Banarsidass, 1979.

- Younghusband, Francis and Molyneux, Edward 1917. Kashmir. A. & C. Black, London.

- Norelli-Bachelet, Patrizia. "Kashmir and the Convergence of Time, Space and Destiny", 2004; ISBN 0-945747-00-4. First published as a four-part series, March 2002 – April 2003, in 'Prakash', a review of the Jagat Guru Bhagavaan Gopinath Ji Charitable Foundation. Kashmir and the Convergence of Time Space and Destiny by Patrizia Norelli Bachelet Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Muhammad Ayub. An Army; Its Role & Rule (A History of the Pakistan Army from Independence to Kargil 1947–1999). Pittsburgh: Rosedog Books, 2005. ISBN 0-8059-9594-3.

External links

- Instrument of Accession

- United Nations Military Observers Group in Kashmir

- Official website of the Jammu and Kashmir Government (Indian-administered Kashmir)

- Official website of the Azad Jammu and Kashmir Government (Pakistan-administered Kashmir)