Video game industry

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Video game industry |

|---|

The video game industry (sometimes referred to as the interactive entertainment industry)[1] is the economic sector involved with the development, marketing and sales of video games. It encompasses dozens of job disciplines and employs thousands of people worldwide.[2]

Overview

Considered by some as a curiosity in the mid-1970s, the computer and video game industries have grown from focused markets to mainstream. They took in about US$9.5 billion in the US in 2007, 11.7 billion in 2008, and 25.1 billion in 2010 (ESA annual report).

Modern personal computers owe many advancements and innovations to the game industry: sound cards, graphics cards and 3D graphic accelerators, faster CPUs, and dedicated co-processors like Physx are a few of the more notable improvements.

Sound cards were developed for addition of digital-quality sound to games and only later improved for music and audiophiles.[3] Early on, graphics cards were developed for more colors.[3] Later, graphics cards were developed for graphical user interfaces (GUIs) and games; GUIs drove the need for high resolution, and games began using 3D acceleration.[3] They also are one of the only pieces of hardware to allow multiple hookups (such as with SLI or CrossFire graphics cards).[3] CD- and DVD-ROMs were developed for mass distribution of media in general; however the ability to store more information on cheap easily distributable media was instrumental in driving their ever higher speeds.[3]

Modern games are among the most demanding of applications on PC resources. Many of the high-powered personal computers are purchased by gamers who want the fastest equipment to power the latest cutting-edge games.[citation needed] Thus, the inertia of CPU development is due in part to this industry whose games demand faster processors than business or personal applications.[citation needed]

Game industry value chain

Ben Sawyer of Digitalmill observes that the game industry value chain is made up of six connected and distinctive layers:

- Capital and publishing layer: involved in paying for development of new titles and seeking returns through licensing of the titles.

- Product and talent layer: includes developers, designers and artists, who may be working under individual contracts or as part of in-house development teams.

- Production and tools layer: generates content production tools, game development middleware, customizable game engines, and production management tools.

- Distribution layer: or the "publishing" industry, involved in generating and marketing catalogs of games for retail and online distribution.

- Hardware (or Virtual Machine or Software Platform) layer: or the providers of the underlying platform, which may be console-based, accessed through online media, or accessed through mobile devices such as smartphones. This layer now includes network infrastructure and non-hardware platforms such as virtual machines (e.g. Java or Flash), or software platforms such as browsers or even further Facebook, etc.

- End-users layer: or the users/players of the games.[4]

Disciplines

The game industry employs those experienced in other traditional businesses, but some have experience tailored to the game industry. For example, many recruiters target just game industry professionals.[citation needed] Some of the disciplines specific to the game industry include: game programmer, game designer, level designer, game producer, game artist and game tester. Most of these professionals are employed by video game developers or video game publishers. However, many hobbyists also produce computer games and sell them commercially.[citation needed] Recently,[when?] game developers have begun to employ those with extensive or long-term experience within the modding communities.

History

1970s

The video game industry began in 1971 with the release of the arcade game, Computer Space[citation needed]. The following year, Atari, Inc. released the first commercially successful video game, Pong, the original arcade version of which sold over 19,000 arcade cabinets.[5] That same year saw the introduction of video games to the home market with the release of the early video game console, the Magnavox Odyssey. However, both the arcade and home markets would be dominated by Pong clones, which flooded the market and led to the video game crash of 1977. The crash eventually came to an end with the success of Taito's Space Invaders, released in 1978, sparking a renaissance for the video game industry and paving the way for the golden age of video arcade games.[6] The game's success inspired arcade machines to become prevalent in mainstream locations such as shopping malls, traditional storefronts, restaurants and convenience stores during the golden age.[7] Space Invaders would go on to sell over 360,000 arcade cabinets worldwide,[8] and by 1982, generate a revenue of $2 billion in quarters,[9][10] equivalent to $4.6 billion in 2011.[11]

Soon after, Space Invaders was licensed for the Atari VCS (later known as Atari 2600), becoming the first "killer app" and quadrupling the console's sales.[12] The success of the Atari 2600 in turn revived the home video game market during the second generation of consoles, up until the North American video game crash of 1983.[13] By the end of the 1970s, the personal computer game industry began forming from a hobby culture, when personal computers just began to become widely available. The industry grew along with the advancement of computing technology, and often drove that advancement.[citation needed]

1980s

The early 1980s saw the golden age of video arcade games reach its zenith. The total sales of arcade video game machines in North America increased significantly during this period, from $50 million in 1978 to $900 million by 1981,[14] with the arcade video game industry's revenue in North America tripling to $2.8 billion in 1980.[15] By 1981, the arcade video game industry was generating an annual revenue of $5 billion in North America,[6][16] equivalent to $12.3 billion in 2011.[11] In 1982, the arcade video game industry reached its peak, generating $8 billion in quarters,[17] equivalent to over $18.5 billion in 2011,[11] surpassing the annual gross revenue of both pop music ($4 billion) and Hollywood films ($3 billion) combined at that time.[17] This was also nearly twice as much revenue as the $3.8 billion generated by the home video game industry that same year; both the arcade and home markets combined add up to a total revenue of $11.8 billion for the video game industry in 1982,[17] equivalent to over $27.3 billion in 2011.[11] The arcade video game industry would continue to generate an annual revenue of $5 billion in quarters through to 1985.[18] The most successful game of this era was Namco's Pac-Man, released in 1980, which would go on to sell over 350,000 cabinets,[19] and within a year, generate a revenue of more than $1 billion in quarters;[20] in total, Pac-Man is estimated to have grossed over 10 billion quarters ($2.5 billion) during the 20th century,[20][21] equivalent to over $3.4 billion in 2011.[11]

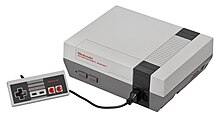

The early part of the decade saw the rise of home computing, and home-made games, especially in Europe (with the ZX Spectrum) and Asia (with the NEC PC-88 and MSX). This time also saw the rise of video game journalism, which was later expanded to include covermounted cassettes and CDs. In 1983, the North American industry crashed due to the production of too many badly developed games (quantity over quality), resulting in the fall of the North American industry. The industry would eventually be revitalized by the release of the Nintendo Entertainment System, which resulted in the home console market being dominated by Japanese companies such as Nintendo,[4] while a professional European computer game industry also began taking shape with companies such as Ocean Software.[22] The latter part of the decade saw the rise of the Game Boy handheld system. In 1987, Nintendo lost a legal challenge against Blockbuster Entertainment, which enabled games rentals in the same way as movies.

1990s

The 1990s saw advancements in game related technology. Among the significant advancements were:

- The widespread adoption of CD-based storage and software distribution

- Widespread adoption of GUI-based operating systems, such as the series of Amiga OS, Microsoft Windows and Mac OS

- Advancement in 3D graphics technology, as 3D graphic cards became widely adopted, with 3D graphics now the de facto standard for video game visual presentation

- Continuing advancement of CPU speed and sophistication

- Miniaturisation of hardware, and mobile phones, which enabled mobile gaming

- The emergence of the internet, which in the latter part of the decade enabled online co-operative play and competitive gaming

Aside from technology, in the early part of the decade, licenced games became more popular,[23][24] as did video game sequels.[25]

The video game industry generated worldwide sales of $19.8 billion in 1993[26] (equivalent to $31 billion in 2011),[11] $20.8 billion in 1994[26] (equivalent to $32 billion in 2011),[11] and an estimated $30 billion in 1998[27] (equivalent to $41.5 billion in 2011).[11] In the United States alone, in 1994, arcades were generating $7 billion[28] in quarters (equivalent to $11 billion in 2011)[11] while home console game sales were generating revenues of $6 billion[28] (equivalent to $9 billion in 2011).[11] Combined, this was nearly two and a half times the $5 billion revenue generated by movies in the United States at the time.[28]

2000s

Though maturing, the video game industry was still very volatile, with third-party video game developers quickly cropping up, and just as quickly, going out of business.[citation needed] Nevertheless, many casual games and indie games were developed and become popular and successful, such as Braid and Limbo. Game development for mobile phones (such as iOS and Android devices) and social networking sites emerged. For example, a Facebook game developer, Zynga, has raised in excess of $300 million.[clarification needed][29]

2010s

Today, the video game industry is a juggernaut of development; profit still drives technological advancement which is then used by other industry sectors. Though not the main driving force, casual and indie games continue to have a significant impact on the industry, with sales of some of these titles such as Minecraft exceeding millions of dollars and over a million users. While development for consoles and PCs is not dormant, development of mobile games is still lively.[citation needed] As of 2014, newer game companies arose that vertically integrate live operations and publishing, rather than relying on a traditional publishers, and some of these have grown to substantial size.[30]

Economics

Early on, development costs were minimal, and video games could be quite profitable. Games developed by a single programmer, or by a small team of programmers and artists, could sell hundreds of thousands of copies each. Many of these games only took a few months to create, so developers could release multiple titles per year. Thus, publishers could often be generous with benefits, such as royalties on the games sold. Many early game publishers started from this economic climate, such as Origin Systems, Sierra Entertainment, Capcom, Activision and Electronic Arts.

As computing and graphics power increased, so too did the size of development teams, as larger staffs were needed to address the ever increasing technical and design complexities. The larger teams consist of programmers, artists, game designers, and producers. Their salaries can range anywhere from $50,000 to $120,000 generating large labor costs for firms producing videogames[31] which can often take between one to three years to develop. Now budgets typically reach millions of dollars despite the growing popularity of middleware and pre-built game engines. In addition to growing development costs, marketing budgets have grown dramatically, sometimes consisting of two to three times of the cost of development.[32]

Some developers are turning to alternative production and distribution methods, such as online distribution, to reduce costs and increase revenue. [33]

Today, the video game industry has a major impact on the economy through the sales of major systems and games such as Call of Duty: Black Ops, which took in over $650 USD million of sales in the game's first five days and which set a five-day global record for a movie, book or videogame.[34] The game's income was more than the opening weekend of Spider-Man 3 and the previous title holder for a video game Halo 3.[35] Many individuals have also benefited from the economic success of video games including the former chairman of Nintendo and Japan's third richest man: Hiroshi Yamauchi.[36] Today the global video game market is valued at over $93 billion.[37]

The industry wide adoption of high-definition graphics during the seventh generation of consoles greatly increased development teams' sizes and reduced the number of high-budget, high-quality titles under development. In 2013 Richard Hilleman of Electronic Arts estimated that only 25 developers were working on such titles for the eighth console generation, compared to 125 at the same point in the seventh generation-console cycle seven or eight years earlier.[38]

Practices

Video game industry practices are similar to those of other entertainment industries (e.g., the music recording industry), but the video game industry in particular has been accused of treating its development talent poorly. This promotes independent development, as developers leave to form new companies and projects. In some notable cases, these new companies grow large and impersonal, having adopted the business practices of their forebears, and ultimately perpetuate the cycle.

However, unlike the music industry, where modern technology has allowed a fully professional product to be created extremely inexpensively by an independent musician, modern games require increasing amounts of manpower and equipment. This dynamic makes publishers, who fund the developers, much more important than in the music industry.

Breakaways

In the video game industry, it is common for developers to leave their current studio and start their own. A particularly famous case is the "original" independent developer Activision, founded by former Atari developers. Activision grew to become the world's second largest game publisher.[39] In the mean time, many of the original developers left to work on other projects. For example, founder Alan Miller left Activision to start another video game development company, Accolade (now Atari née Infogrames).

Activision was popular among developers for giving them credit in the packaging and title screens for their games, while Atari disallowed this practice. As the video game industry took off in the mid-1980s, many developers faced the more distressing problem of working with fly-by-night or unscrupulous publishers that would either fold unexpectedly or run off with the game profits.

Piracy

The industry claims software piracy to be a big problem, and take measures to counter this.[40] However, digital rights management and other measures have proved noticeably unpopular with gamers.[41]

Creative control

On various Internet forums, some gamers have expressed disapproval of publishers having creative control since publishers are more apt to follow short-term market trends rather than invest in risky but potentially lucrative ideas. [citation needed] On the other hand, publishers may know better than developers what consumers want. The relationship between video game developers and publishers parallels the relationship between recording artists and record labels in many ways. But unlike the music industry, which has seen flat or declining sales in the early 2000s,[42][43][44] the video game industry continues to grow.[45] Also, personal computers have made the independent development of music almost effortless, while the gap between an independent game developer and the product of a fully financed one grows larger.

In the computer games industry, it is easier to create a startup, resulting in many successful companies. The console games industry is a more closed one, and a game developer must have up to three licenses from the console manufacturer:

- A license to develop games for the console

- The publisher must have a license to publish games for the console

- A separate license for each game

In addition, the developer must usually buy development systems from the console manufacturer in order to even develop a game for consideration, as well as obtain concept approval for the game from the console manufacturer. Therefore, the developer normally has to have a publishing deal in place before starting development on a game project, but in order to secure a publishing deal, the developer must have a track record of console development, something which few startups will have.

Alternatives

An alternative method for publishing video games is to self-publish using the shareware or open source model over the Internet.

Gaming Conventions

Gaming conventions are an important showcase of the industry. The major annual gaming conventions include gamescom in Cologne (Germany), the E3 in Los Angeles, (USA)[46] the Penny Arcade Expo, and others.

International practices

World trends

International video game revenue is estimated to be $81.5B in 2014.[47] This is more than double the revenue of the international film industry in 2013.[48]

The largest nations by video game revenues are the United States ($20.5B), China ($17.9B), and Japan ($12.2B).[47] The largest regions are Asia ($36.8B), North America ($22.2B), and Western Europe ($15.4B).[47]

Conventions

Gaming conventions are an important showcase of the industry. The annual gamescom in Cologne (Germany) is a major expo for video games. The E3 in Los Angeles (USA) is also of global importance, but is an event for industry insiders only.[49]

Other notable conventions and trade fairs include Tokyo Game Show (Japan), Brasil Game Show, EB Games Expo (Australia), KRI (Russia), ChinaJoy and the annual Game Developers Conference. Some publishers, developers and technology producers also have their own regular conventions, with BlizzCon, QuakeCon, Nvision and the X shows being prominent examples.

Canada

Canada has the third largest video game industry in terms of employment numbers.[50] The video game industry has also been booming in Montreal since 1997, coinciding with the opening of Ubisoft Montreal.[citation needed] Recently, the city has attracted world leading game developers and publishers studios such as Ubisoft, EA, Eidos Interactive, Artificial Mind and Movement, Bioware, Warner Bros. Interactive Entertainment and Strategy First, mainly because video games jobs have been heavily subsidized by the provincial government. Every year, this industry generates billions of dollars and thousands of jobs in the Montreal area.[citation needed] Vancouver has also developed a particularly large cluster of video game developers, the largest of which, Electronic Arts, employs over two thousand people. The Assassin's Creed series, along with the Tom Clancy series have all been produced in Canada and have achieved worldwide success.

China

China is the second-largest country by game revenue,[47] and has a gaming public that exceeds the population of the entire United States.[52] It is home to Asia Game Show, the largest game convention in the world by attendance.[53] In 2014, the Xbox One became the first new game console sold since China's ban on consoles in 2000.[52]

Germany

Germany has the largest video games market in Europe, with revenues of 2.66 billion Euro generated.[54] The annual gamescom in Cologne is the Europe's largest gaming expo.

One of the earliest internationally successful video game companies was Gütersloh-based Rainbow Arts (founded in 1984) who were responsible for publishing the popular Turrican series of games. The Anno series and The Settlers series are globally popular strategy game franchises since the 1990s. The Gothic series, SpellForce and Risen are established RPG franchises. The X series by Egosoft is the best-selling space simulation. The FIFA Manager series was also developed in Germany. The German action game Spec Ops: The Line (2012) was successful in the markets and received largely positive reviews. One of the most famed titles to come out of Germany is Far Cry (2004) by Frankfurt-based Crytek, who also produced the topseller Crysis and its sequels later.

Other well-known current and former developers from Germany include Ascaron, Blue Byte, Deck13, Phenomic, Piranha Bytes, Radon, Related, Spellbound and Yager Development. Publishers include Deep Silver (Koch Media), dtp entertainment, Kalypso and Nintendo Europe. Bigpoint Games, Gameforge, Goodgame Studios and Wooga are among the world's leading browser game and social network game developers/distributors.

Japan

The Japanese video game industry is markedly different from the industry in North America, Europe and Australia.

Japan has created some of the largest and most lucrative titles ever made, such as the Mario, Final Fantasy, Metal Gear and Pokémon series of games.

In recent years consoles and arcade games have both been overtaken by downloadable free-to-play games on the PC and mobile platforms.[55][56]

United Kingdom

The UK industry is the third largest in the World in terms of developer success and sales of hardware and software by country alone but fourth behind Canada in terms of people employed.[50] In recent years some of the studios have become defunct or been purchased by larger companies such as LittleBigPlanet developer, Media Molecule[57] and Codemasters.[58] The country is home to some of the world's most successful video game franchises, such as Tomb Raider, Grand Theft Auto, Fable, Colin McRae Dirt and Total War.

The country also went without tax relief until 21 March 2012[59] when the British government changed its mind on tax relief for UK developers, which without, meant most of the talented development within the UK may move overseas for more profit, along with parents of certain video game developers which would pay for having games developed in the UK. The industry trade body TIGA estimates that it will increase the games development sector’s contribution to UK GDP by £283 million, generate £172 million in new and protected tax receipts to HM Treasury, and could cost just £96 million over five years.[60] Before the tax relief was introduced there was a fear that the UK games industry could fall behind other leading game industries around the world such as France and Canada, of which Canada overtook the UK in terms of job numbers in the industry in 2010.[61]

United States

The United States has the largest video games market in the world in terms of revenue and total industry employees.[50][62] In 2004, the U.S. game industry as a whole was worth USD$10.3 billion.[63] U.S. gaming revenue was estimated to be $20.5B in 2014.[47]

History

Magnavox is credited for releasing the first video game console, the Odyssey. Activision was the first developer to create independent/third-party video games. Once the fastest-growing American company, Atari crashed in spectacular fashion, resulting in the North American video game crash of 1983. This resulted in the domination of the Japanese video game industry worldwide throughout the 1980s and 1990s.

Companies

Today the U.S. is home to major game development companies such as Activision Blizzard (Call of Duty, World of Warcraft), Electronic Arts (FIFA, Battlefield, Mass Effect), and Take-Two Interactive (Borderlands, Grand Theft Auto). ZeniMax Media (Doom, Quake) is the world's largest privately held video game company.[64]

Microsoft operates one of the largest game console hardware franchises, the largest mobile gaming platforms are operated by Google, and Apple Inc.,[65] and Valve Corporation operates the largest PC gaming platform.

Advanced Micro Devices has become the most important console processor vendor, with all three of the eighth generation home consoles using AMD GPUs, and two of them use AMD CPUs. Microsoft, Nintendo, and Sony were not aware that they were all using AMD processors until all their consoles were announced.[66] Notable game engine developers include Epic Games (Unreal Engine) and Unity Technologies (Unity).

Regions

The West Coast is home to important video game conventions, such as Electronic Entertainment Expo (E3), one of the largest video game industry-only events in the world, and Penny Arcade Expo (PAX Prime), the largest public video game convention in North America. The West Coast is also home to many of the major American video game industry companies, particularly the regions of Los Angeles, San Francisco Bay Area, and Seattle. Major game development centers outside of the West Coast include the Northeast and Texas.

Animation

Shigeru Miyamoto originally wanted the love triangle of Mario, Pauline and Donkey Kong to be Popeye, Olive Oyl, and Bluto, however Nintendo did not acquire the rights in time for development of Donkey Kong. The Walt Disney Company, including subsidiaries Pixar and Lucasfilm, licenses several notable characters to other development companies, while developing their own games as well. Disney created the video game oriented movie Wreck-It Ralph in 2012, featuring characters from several famous video game franchises. Threshold Entertainment have produced movies based on Mortal Kombat, and are working on an upcoming action movie based on Tetris.

People

Several important game development personalities were born in or moved to the United States. Notable developers include Ralph H. Baer (Magnavox Odyssey, the "Father of Video Games"), Jonathan Blow (Braid), John D. Carmack (Doom, Quake), and Alexey Pajitnov (Tetris). Mario is named after Mario Segale, a former landlord of Nintendo of America. Some right-wing and left-wing activists, including Jack Thompson and Anita Sarkeesian, have met extreme resistance from the gaming public in response to the perceived politicizing of their art form.[67]

Sports

The United States recognizes eSports players as professional athletes.[68] Major League Gaming has eSports arenas and studios across the nation.[69] Robert Morris University has a League of Legends varsity team, whose members are eligible for scholarships.[70]

Trends

Since the mid-1990s, players have been able to develop game content[citation needed]. Players become fourth-party developers, allowing for more open source models of game design, development and engineering[citation needed]. Players also create modifications (mods), which in some cases become just as popular as the original game for which they were created. An example of this is the game Counter-Strike, which began as a mod of the video game Half-Life and eventually became a very successful, published game in its own right[citation needed].

While this "community of modifiers" may only add up to approximately 1% of a particular game's user base[citation needed], the number of those involved will grow as more games offer modifying opportunities (such as, by releasing source code) and the video user base swells[citation needed]. According to Ben Sawyer[citation needed], as many as 600,000 established online game community developers existed as of 2012[citation needed]. This effectively added a new component to the game industry value chain and if it continues to mature, it will integrate itself into the overall industry.[4]

The industry has seen a shift towards games with multiplayer facilities[citation needed]. A larger percentage of games on all types of platforms include some type of competitive online multiplayer capability.[original research?]

In addition, the industry is experiencing further significant change driven by convergence, with technology and player comfort being the two primary reasons for this wave of industry convergence[citation needed]. Video games and related content can now be accessed and played on a variety of media, including: cable television, dedicated consoles, handheld devices and smartphones, through social networking sites or through an ISP, through a game developer's website, and online through a game console and/or home or office personal computer[citation needed]. In fact, 12%[citation needed] of U.S. households already make regular use of game consoles for accessing video content provided by online services such as Hulu and Netflix. In 2012, for the first time, entertainment usage passed multiplayer game usage on Xbox, meaning that users spent more time with online video and music services and applications than playing games. This rapid type of industry convergence has caused the distinction between video game console and personal computers to disappear.[citation needed] A game console with high-speed microprocessors attached to a television set is, for all intents and purposes, a computer and monitor.[71]

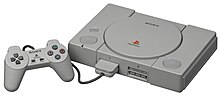

As this distinction has been diminished, players' willingness to play and access content on different platforms has increased[citation needed]. The growing video gamer demographic accounts for this trend, as former president of the Entertainment Software Association Douglas Lowenstein explained at the 10th E3 expo, "Looking ahead, a child born in 1995, E3's inaugural year, will be 19 years old in 2014[citation needed]. And according to Census Bureau data, by the year 2020, there will be 174 million Americans between the ages of 5 and 44[citation needed]. That's 174 million Americans who will have grown up with PlayStations, Xboxes, and GameCubes from their early childhood and teenage years...What this means is that the average gamer will be both older and, given their lifetime familiarity with playing interactive games, more sophisticated and discriminating about the games they play."[72]

Evidence of the increasing player willingness to play video games across a variety of media and different platforms can be seen in the rise of casual gaming on smartphones[citation needed], tablets[citation needed], and social networking sites [citation needed]as 92% of all smartphone and tablet owners play games at least once a week, 45% play daily, and industry estimates predict that, by 2016, one-third of all global mobile gaming revenue will come from tablets alone. Apple's App Store alone has more than 90,000 game apps, a growth of 1,400% since it went online. In addition, game revenues for iOS and Android mobile devices now exceed those of both Nintendo and Sony handheld gaming systems combined.[73]

See also

- List of game topics

- Game Developer magazine

Further reading

- André Marchand and Thorsten Hennig-Thurau: Value Creation in the Video Games Industry: Industry Economics, Consumer Benefits, and Research Opportunitites, Journal of Interactive Marketing, 27 (3), 141-157, 2013.

References

- ^ Bob Johnstone. "Video Games Industry Infographics". ESRB Infographics. ESRB. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ^ Zackariasson, P. and Wilson, T.L. eds. (2012). The Video Game Industry: Formation, Present State, and Future. New York: Routledge.

- ^ a b c d e Bob Johnstone. "Didi Games". Research on Video Games. Didi Games. Retrieved 1 April 2009.

- ^ a b c Flew, Terry; Humphreys, Sal (2005). "Games: Technology, Industry, Culture". New Media: an Introduction (Second Edition). Oxford University Press. pp. 101–114. ISBN 0-19-555149-4.

- ^ Ashley S. Lipson & Robert D. Brain (2009). Computer and Video Game Law: Cases and Materials. Carolina Academic Press. p. 9. ISBN 1-59460-488-6. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

Atari eventually sold more than 19,000 Pong machines, giving rise to many imitations. Pong made its first appearance in 1972 at "Andy Capp's," a small bar in Sunnyvale, California, where the video game was literally "overplayed" as eager customers tried to cram quarters into an already heavily overloaded coin slot.

- ^ a b Jason Whittaker (2004). The cyberspace handbook. Routledge. p. 122. ISBN 0-415-16835-XTemplate:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Edge Staff (13 August 2007). "The 30 Defining Moments in Gaming". Edge. Future plc. Retrieved 18 September 2008.

- ^ Jiji Gaho Sha, inc. (2003). "Asia Pacific perspectives, Japan". 1. University of Virginia: 57. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

At that time, a game for use in entertainment arcades was considered a hit if it sold 1000 units; sales of Space Invaders topped 300,000 units in Japan and 60,000 units overseas.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Making millions, 25 cents at a time". The Fifth Estate. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 23 November 1982. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- ^ "Space Invaders vs. Star Wars". Executive. 24. Southam Business Publications: 9. 1982. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

According to TEC, Atari's arcade game Space Invaders has taken in $2 billion, with net recipts of $450 million.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "CPI Inflation Calculator". Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ "The Definitive Space Invaders". Retro Gamer (41). Imagine Publishing: 24–33. September 2007. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ Jason Whittaker (2004). The cyberspace handbook. Routledge. pp. 122–3. ISBN 0-415-16835-XTemplate:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Mark J. P. Wolf (2008). The video game explosion: a history from PONG to Playstation and beyond. ABC-CLIO. p. 105. ISBN 0-313-33868-X. Retrieved 19 April 2011Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ "Electronic Education". Electronic Education. 2 (5–8). Electronic Communications: 41. 1983. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

In 1980 alone, according to Time, $2.8 billion in quarters, triple the amount of the previous years, were fed into video games.

- ^ Mark J. P. Wolf (2008). The video game explosion: a history from PONG to Playstation and beyond. ABC-CLIO. p. 103. ISBN 0-313-33868-X. Retrieved 19 April 2011Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ a b c Everett M. Rogers & Judith K. Larsen (1984). Silicon Valley fever: growth of high-technology culture. Basic Books. p. 263. ISBN 0-465-07821-4. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

Video game machines have an average weekly take of $109 per machine. The video arcade industry took in $8 billion in quarters in 1982, surpassing pop music (at $4 billion in sales per year) and Hollywood films ($3 billion, $10 billion if cassette sales and rentals are included). Those 32 billion arcade games played translate to 143 games for every man, woman, and child in America. A recent Atari survey showed that 86 percent of the US population from 13 to 20 has played some kind of video game and an estimated 8 million US homes have video games hooked up to the television set. Sales of home video games were $3.8 billion in 1982, approximately half that of video game arcades.

- ^ Ellen Goodman (1985). Keeping in touch. Summit Books. p. 38. ISBN 0-671-55376-3. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

There are 95,000 others like him spread across the country, getting fed a fat share of the $5 billion in videogame quarters every year.

- ^ Kevin "Fragmaster" Bowen (2001). "Game of the Week: Pac-Man". GameSpy. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

Released in 1980, Pac-Man was an immediate success. It sold over 350,000 units, and probably would of [sic] sold more if not for the numerous illegal pirate and bootleg machines that were also sold.

- ^ a b Mark J. P. Wolf (2008). "Video Game Stars: Pac-Man". The video game explosion: a history from PONG to Playstation and beyond. ABC-CLIO. p. 73. ISBN 0-313-33868-X. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

It would go on to become arguably the most famous video game of all time, with the arcade game alone taking in more than a billion dollars, and one study estimated that it had been played more than 10 billion times during the twentieth century.

- ^ Chris Morris (10 May 2005). "Pac Man turns 25: A pizza dinner yields a cultural phenomenon - and millions of dollars in quarters". CNN. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

In the late 1990s, Twin Galaxies, which tracks video game world record scores, visited used game auctions and counted how many times the average Pac Man machine had been played. Based on those findings and the total number of machines that were manufactured, the organization said it believed the game had been played more than 10 billion times in the 20th century.

- ^ YS Top 100 from World of Spectrum

- ^ Fahs, Travis (8 August 2008). "IGN Presents the History of Madden - Retro Feature at IGN". Uk.retro.ign.com. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ^ Hurby, Patrick. "ESPN - OTL: The Franchise - E-ticket". Sports.espn.go.com. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ^ McLaughlin, Rus (7 July 2010). "IGN Presents the History of Street Fighter - Retro Feature at IGN". Uk.retro.ign.com. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ^ a b Statistical yearbook: cinema, television, video, and new media in Europe, Volume 1999. Council of Europe. 1996. p. 123.

- ^ Statistical yearbook: cinema, television, video, and new media in Europe, Volume 1999. Council of Europe. 1996. p. 123.

- ^ a b c "Business Week". Business Week (3392–3405). Bloomberg: 58. 1994. Retrieved 25 January 2012.

Hollywood's aim, of course, is to tap into the $7 billion that Americans pour into arcade games each year — and the $6 billion they spend on home versions for Nintendo and Sega game machines. Combined, it's a market nearly 2 ½ times the size of the $5 billion movie box office.

- ^ "Zynga Takes $180 Million Venture Round From DST, Others (Cue Russian Mafia Jokes)". TechCrunch. 15 December 2009. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ^ Radoff, Jon (10 February 2014). "The Future of Games and How to Stop It". medium.com. medium.com. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ^ "Top Gaming Studios, Schools & Salaries", Big Fish Games

- ^ Superannuation. "How Much Does It Cost To Make A Big Video Game?". Kotaku. Gawker Media. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- ^ Kain, Erik. "Why Digital Distribution Is The Future And GameStop Is Not: Taking The Long View On Used Games". Forbes. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- ^ "Call of Duty: Black Ops" sets record for Activision". Yahoo Games Plugged In. 2010-12-21. Retrieved on 2011-05-19.

- ^ "Variety: GTA IV Launch Bigger Than Halo 3 (And Then Some)", Kotaku, 2008-04-15. Retrieved on 2008-04-15.

- ^ "Japan's Richest Man Is...Yes, Hiroshi Yamauchi". Forbes. 7 May 2008. Archived from the original on 30 March 2009. Retrieved 30 March 2009.

- ^ van der Meulen, Rob. "Gartner Says Worldwide Video Game Market to Total $93 Billion in 2013". Gartner. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- ^ D'Angelo, William (6 July 2013). "EA: AAA Development in Decline". VGChartz. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ Wolverton, Troy (24 May 2005). "Activision Aims for Sweet Spot". TheStreet.com. Archived from the original on 30 March 2009. Retrieved 30 March 2009.

- ^ Valjalo, David (4 October 2010). "3DS Will Fight Piracy With Firmware | Edge Magazine". Next-gen.biz. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ^ "Technology | EA 'dumps DRM' for next Sims game". BBC News. 31 March 2009. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ^ Global sales of recorded music down 9.2% in the first half of 2002 from IFPI

- ^ Global sales of recorded music down 10.9% in the first half of 2003 from IFPI

- ^ Digital sales triple to 6% of industry retail revenues as global music market falls 1.9% (2005) from IFPI

- ^ Video game industry growth still strong: study from Reuters

- ^ "E3 is Obsolete, But it Doesn't Matter". Forbes. 8 June 2012. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ a b c d e "Top 100 Countries Represent 99.8% of $81.5Bn Global Games Market". newzoo.

- ^ "Percentage of GBO of all films feature exhibited that are national". UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ^ "E3 is Obsolete, But it Doesn't Matter". Forbes. 8 June 2012. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ a b c "Canada boasts the third-largest video game industry". Networkworld.com. 6 April 2010. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ^ "Game Revenues of Top 25 Companies up 17%, Totaling $25Bn". newzoo.

- ^ a b "Xbox One Hits China Today Following 14-Year Console Ban". GameSpot.

- ^ "The World's Biggest Games Show Isn't In Germany. Not Any More". Kotaku.

- ^ "With 2.66 billions of revenue, Germany is Europe's top video game market, new data by Newzoo and G.A.M.E." G.A.M.E. Association. 1 March 2014. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ "Japan fights back". The Economist. 17 November 2012.

- ^ "Market Data". Capcom. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- ^ "Media Molecule Officially Joins The PlayStation Family – PlayStation.Blog.Europe". Blog.eu.playstation.com. 2 March 2010. Retrieved 27 January 2011.

- ^ Hinkle, David (5 April 2010). "Reliance Big Entertainment acquires 50% stake in Codemasters". Joystiq. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ^ Henderson, Rik (21 March 2012). "UK tax relief break". Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ^ Post comment Name Email Address Comments (22 June 2010). "Game industry tax relief plans are shelved". Wired.co.uk. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ^ "Canada overtakes UK". 31 March 2012. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ^ "US still the gaming super power | GamesIndustry International". Gamesindustry.biz. 11 December 2012. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ^ "An Industry Shows Its Growing Value". BusinessWeek.com. Interactive Entertainment Today. 12 May 2006. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- ^ "Zenimax Claims Carmack Stole Oculus VR, Facebook Barks Back".

- ^ App Annie, IDC. "App Annie & IDC Portable Gaming Report Q2 2013: iOS & Google Play Game Revenue 4x Higher Than Gaming-Optimized Handhelds".

- ^ Gorman, Michael (12 June 2013). "AMD's Saeid Moshkelani on building custom silicon for PlayStation 4, Xbox One and Wii U". Engadget.

- ^ Allum Bokhari (25 September 2014). "#GamerGate – An Issue With Two Sides". TechCrunch. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^ "The U.S. Now Recognizes eSports Players As Professional Athletes". Forbes.

- ^ "Major League Gaming announces its own arena in Columbus, Ohio". VentureBeat.

- ^ "Illinois university makes League of Legends a varsity sport". Gamasutra.

- ^ University, Stanley J. Baran, Bryant (2014). Introduction to Mass Communication : Media Literacy and Culture (Eighth Edition. ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 220–221. ISBN 978-0-07-352621-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ University, Stanley J. Baran, Bryant (2014). Introduction to Mass Communication : Media Literacy and Culture (Eighth Edition. ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-07-352621-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ University, Stanley J. Baran, Bryant (2014). Introduction to Mass Communication : Media Literacy and Culture (Eighth Edition. ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 222. ISBN 978-0-07-352621-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)